Abstract

Our ability to focus attention on task-relevant stimuli and ignore irrelevant distractions is reflected by differential enhancement and suppression of neural activity in sensory cortices. Previous research has shown that older adults exhibit a deficit in suppressing task-irrelevant information, the magnitude of which is associated with a decline in working memory performance. However, it remains unclear if a failure to suppress is a reflection of an inability of older adults to rapidly assess the relevance of information upon stimulus presentation when they are not aware of the relevance beforehand. To address this, we recorded the electroencephalogram (EEG) in healthy older participants (aged 60–80 years) while they performed two different versions of a selective face/scene working memory task, both with and without prior knowledge as to when relevant and irrelevant stimuli would appear. Each trial contained two faces and two scenes presented sequentially followed by a nine second delay and a probe stimulus. Participants were given the following instructions: remember faces (ignore scenes), remember scenes (ignore faces), remember the xth and yth stimuli (where x and y could be 1st, 2nd, 3rd or 4th), or passively view all stimuli. Working memory performance remained consistent regardless of task instructions. Enhanced neural activity was observed at posterior electrodes to attended stimuli, while neural responses that reflected the suppression of irrelevant stimuli was absent for both tasks. The lack of significant suppression at early stages of visual processing was revealed by P1 amplitude and N1 latency modulation indices. These results reveal that prior knowledge of stimulus relevance does not modify early neural processing during stimulus encoding and does not improve working memory performance in older adults. These results suggest that the inability to suppress irrelevant information early in the visual processing stream by older adults is related to mechanisms specific to top-down suppression.

Keywords: suppression, EEG, aging, working memory, selective attention

1. Introduction

The relationship humans have with their environment is characterized by a dynamic interaction between externally driven perceptual processing (bottom-up) and internally generated influences (top-down). Whereas bottom-up processing may capture attention based on stimulus salience or novelty, top-down modulation refers to our ability to orient our attention toward task-relevant stimuli and away from irrelevant distractions that may otherwise hinder our goals (Bar, 2003; Frith, 2001; Posner, Snyder et al., 1980; Eriksen and Hoffman, 1974). Neural signatures of top-down modulation during visual processing have been identified through single-cell physiology, functional neuroimaging and electroencephalography (EEG) data, revealing that activity in the visual association cortex increases when attention is focused on a stimulus and decreases when the stimulus is ignored (Pessoa, Kastner et al., 2003; Kastner and Ungerleider, 2001; Gazzaley, Cooney et al., 2005a).

Due to the neural biasing of sensory representations by top-down modulation, successful working memory (WM) storage may be achieved through the neural amplification of relevant information (Rainer, Asaad et al., 1998; Ploner, Ostendorf et al., 2001). At the same time, blocking irrelevant information is critical to prevent overloading our limited WM capacity and is necessary to attain optimal WM performance (Vogel, McCollough et al., 2005; Zanto and Gazzaley, 2009). Thus, failure to enhance relevant information or suppress irrelevant information may lead to a decline in WM performance.

To account for age-related impairments in WM performance, the inhibitory deficit hypothesis attributes observed behavioral impairments to interference from task-irrelevant information (Hasher, Zacks et al., 1999). In support of this hypothesis, a functional neuroimaging study assessed blood oxygen level dependent activity from face and scene selective areas, while young and older adults attended to or ignored face and scene stimuli during the encoding period of a delayed WM recognition task (Gazzaley, Cooney et al., 2005b). It was shown that both young and older adults enhance task-relevant cortical activity, whereas older adults display a selective deficit in the suppression of cortical activity associated with task-irrelevant stimuli. Moreover, the magnitude of the suppression deficit correlated with impaired WM performance.

A more recent study utilized EEG recordings in conjunction with the same paradigm to identify age-related changes in neuroelectrical markers of enhancement and suppression (Gazzaley, Clapp et al., 2008). Event related potentials (ERPs) and time-frequency data were analyzed when participants attended, ignored or passively viewed face and scene stimuli. Older adults displayed diminished WM accuracy in the presence of distracting information, as well as slower response times for recognizing the relevant information after a delay period. ERP markers of early visual processing (< 200 ms: P1 amplitude and N1 latency) mirrored previous fMRI results, such that both young and older adults demonstrated enhanced task-relevant posterior cortical activity relative to passively viewing the stimuli (larger P1 amplitude & earlier N1 latency). However, only the young adults significantly suppressed activity associated with irrelevant stimuli (smaller P1 amplitude & later N1 latency, each relative to passive view). An assessment of later visual processing stages (> 500 ms), using alpha band (8–12 Hz) desynchronization as an attentional marker, showed that both young and older adults were capable of enhancing neural activity (i.e. more desynchronized) to relevant stimuli and suppressing neural activity (i.e. less desynchronized) to irrelevant stimuli. This was interpreted as reflecting protracted processing in visual areas, which can then be suppressed by the older adults. Therefore, the observed suppression deficit to irrelevant stimuli appeared to be restricted to early visual processing. This study thus provides evidence for an interaction between an age-related suppression deficit and processing speed delays.

The P1 (a positive deflection, approximately 100 ms post-stimulus onset) and the N1 (a negative deflection, approximately 170 ms post-stimulus onset) of the visual ERP were revealed to be early physiological markers of an age-related suppression deficit (Gazzaley, Clapp et al., 2008). Previous research has linked P1 and N1 modulation with different types of selective attention, such as spatial and feature and object-based attention (Valdes-Sosa, Bobes et al., 1998; Rugg, Milner et al., 1987; Hillyard and Anllo-Vento, 1998; Rutman, Clapp et al., In Press). Modulation of the P1/N1 is thought to be a reflection of the top-down control of information flow in extrastriate visual cortical areas (Hillyard, Vogel et al., 1998). It was thus interpreted that the lack of P1 and N1 suppression in older adults reflects deficient top-down suppression of irrelevant information at early time points in the visual processing stream. The ability for older adults to suppress processing in visual areas later, but not early, may be due to structural or strategic differences between young and older adults that selectively delay suppression mechanisms.

Another interpretation of these findings is revealed by taking into account the task design used in the previous studies, in which relevant and irrelevant stimuli were presented sequentially in a randomized order (Gazzaley, Cooney et al., 2005a; Gazzaley, Cooney et al., 2005b; Gazzaley, Clapp et al., 2008). This task required participants to recognize the stimulus category and assess relevance upon the appearance of the stimulus, prior to enhancing or suppressing neural activity. Therefore, if older adults were slower to recognize the stimulus as relevant or irrelevant, this may have been responsible for the early suppression deficit. Given that both young and older adults are capable of enhancing neural activity to attended stimuli, this interpretation would indicate that attending to the stimuli is a default response, while suppression requires additional processing that becomes delayed with age. Thus, the delay in suppression may not be specific to delays in the neural mechanisms that underlie the suppression processes, but rather a reflection of age-related delays in the speed of assessing stimulus relevance. It has been suggested that central processing functions are slowed in older adults (Jordan and Rabbitt, 1977; Surwillo, 1968). The processing speed theory of cognitive aging (Salthouse, 1996) proposes that age-related declines in cognitive function (e.g. WM performance) stem from slowed processing operations. Further support for this interpretation is revealed by a main effect of age for the N1 latency, indicating that older adults exhibit overall slower neural processing at this early stage (Gazzaley, Clapp et al., 2008; Zanto, Toy et al., In press).

The goal of this study was to disambiguate two interpretations of a failure of older adults to suppress irrelevant information early in the visual processing stream: A delay in mechanisms specific to top-down suppression, or a delay in the time needed to recognize a stimulus as relevant or irrelevant. To address this goal, twenty-one older adults engaged in the same task used in Gazzaley et al. (2005a; 2008), and a new task that instructed them prior to the start of each trial as to when in the sequence the relevant stimuli, and thus the irrelevant stimuli, would appear. This task was utilized so that there was no need for the participants to first recognize the stimulus and assess its relevance prior to enhancing/suppressing it. If a difference in suppression indices were observed, such that the original task replicated the result of a lack of suppression and the new task revealed significant suppression, this would indicate that the absence of early suppression previously reported in older adults was a consequence of age-related delays in the recognition of stimulus relevance and not a change specific for suppression mechanisms. If on the other hand, the new task yielded the same lack of suppression at early stages of processing as the original task, it would suggest that age-related delays in the assessment of relevance were not a factor.

EEG data was acquired during the experiment and both ERP and spectral measures of attentional modulation were utilized, as in Gazzaley et al. (2008), to evaluate the time-course of top-modulation of visual processing. The selected measures have been previously shown in the literature to be modulated by attention and associated with visual processing at early and late time points. The P1 and N1 served to reflect early processes (Gazzaley, Cooney et al., 2005a; Gomez Gonzalez, Clark et al., 1994) and alpha desychronization to reflect later processes (500–650 ms) (Muller and Keil, 2004). While it is true that these measures may reflect different physiological processes, all of these measures have revealed three levels of activity in young adults (i.e., attend > passive (enhancement), passive > ignore (suppression)) (Gazzaley, Clapp et al., 2008), thus fulfilling our requirement as markers of top-down modulation at different time points in the course of visual processing. This study utilized these same measures to assess if the previously reported findings in older adults of an absence of early suppression and retained suppression later in processing were influenced by our task manipulation. Although the P3 is known to be affected in aging (for review see Kok, 2000), the P3 as a marker of attentional modulation was not significantly affected by age using this paradigm (Gazzaley, Clapp et al., 2008) and will not be analyzed in this study.

2. Methods

2.1 Participants

Twenty-one older adults (mean age 69 years; range 60–80 years; 8 males) gave consent to participate in the study. All participants had normal or corrected to normal vision and were screened to ensure they were healthy, had no history of neurological, psychiatric, or vascular disease, were not depressed, and were not taking any psychotropic or hypertensive medications. Visual acuity was checked for each participant using a Snellen chart and corrective lenses were utilized as necessary to achieve 20/40 vision or better. Additionally, all participants were required to have 12 years minimum education.

2.2 Neuropsychological testing

To ensure older adults were “normal” relative to their age-matched peers, participants in the older age group were required to score within two standard deviations of control values on 13 neuropsychological tests. The neuropsychological evaluation consisted of tests designed to assess general intellectual function (MMSE; Folstein, Folstein et al., 1975), verbal learning (CVLT-II; Delis, Kramer et al., 2000), geriatric depression (GDS; Yesavage, Brink et al., 1982), visual-spatial function (copy of a modified Rey-Osterrieth figure), visual-episodic memory (memory for details of a modified Rey-Osterrieth figure), visual-motor sequencing (trail making test A and B; Reitan, 1958; Tombaugh, 2004), phonemic fluency (words beginning with the letter ‘D’), semantic fluency (animals), calculation ability (arithmetic), executive functioning (Stroop interference test; Stroop, 1935), working memory and incidental recall (backward digit span and digit symbol, WAIS-R; Wechsler, 1981).

2.3 Stimuli

The stimuli consisted of grayscale images of faces and natural scenes. Each face and scene image presented during the experiment was unique (i.e. images were not repeated in different trials). Images were 225 pixels wide and 300 pixels tall, (14×18 cm) and subtended approximately 5 by 6 degrees of visual angle (participants were approximately 172 cm from the screen). The face stimuli consisted of a variety of neutral-expression male and female faces across a large age range. The gender of the face stimuli was held constant within each trial.

2.4 Experimental Procedure

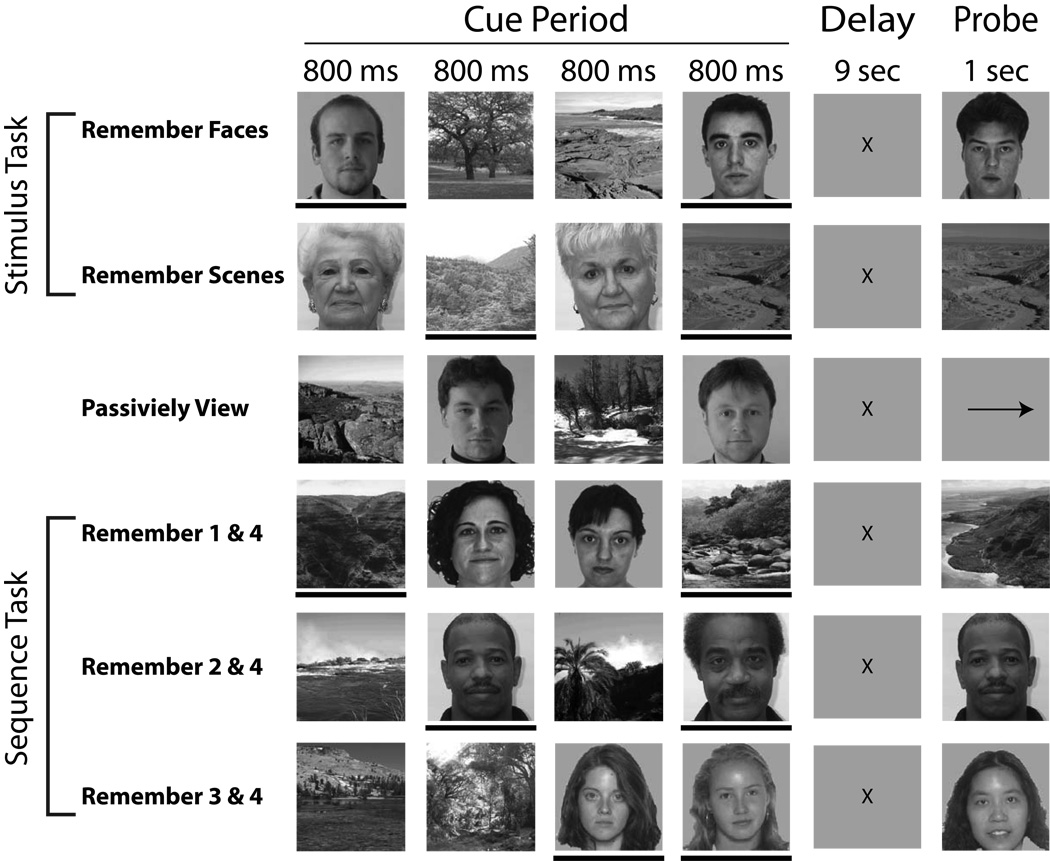

The cognitive paradigm was composed of six different conditions (Fig. 1). Each condition consisted of the same basic temporal design, such that they all required viewing four images (cue period): two faces and two scenes each being displayed for 800 ms (200ms ISI), followed by a nine second delay period in which the relevant images were to be remembered and mentally rehearsed. After the delay, a fifth image appeared (probe). The subject was asked to respond with a button press (as quickly as possible without sacrificing accuracy) whether the probe image matched either of the two relevant images held in memory (match or no match). The tasks differed in the instructions given at the beginning of each run.

Figure 1.

Experimental conditions. A black bar below an image marks it as a stimulus to remember, but is present for illustration purposes only (not seen during experiment).

Three of the six conditions replicated the original experiment from Gazzaley et al. (2008) (referred to here as the “Stimulus” task): a Face Memory condition, a Scene Memory condition and a Passive View condition. For the Face Memory condition, the participants were asked to remember only the face stimuli and to ignore the scene stimuli. Correspondingly for the Scene Memory condition, participants were asked to remember only the scene stimuli and ignore the faces. The Face Memory and Scene Memory conditions are collectively designated the “Stimulus” task because attending and ignoring one stimulus type (face or scene) requires data from both conditions. As previously noted, the Stimulus task utilized a randomized presentation order of the relevant and irrelevant stimuli during the cue period. When the Probe image appeared, it was composed of a face in the Face Memory condition, or a scene in the Scene Memory condition. During the Passive View condition, participants were instructed to relax and view the stimuli without trying to remember them. Instead of a probe image, an arrow was presented where participants were required to make a button press indicating the direction of the arrow (left or right).

In the other three conditions (designated the “Sequence” task), participants were instructed as to which of the four images were relevant by the order of their appearance: positions 1 & 4, 2 & 4 or 3 & 4. In 87.5% of the trials, the two relevant stimuli were from the same category (i.e. both faces or both scenes) and the probe was also of the same category. The remaining 12.5% of the trials marked one face and one scene as relevant. However, these trials were discarded from analysis to be consistent with the original paradigm (Stimulus task), in which both relevant stimuli were of the same stimulus type. During the Sequence task, the fourth image was always relevant in order to keep participants actively ignoring irrelevant stimuli. For counterbalancing purposes, the randomization during the Face and Scene Memory conditions (Stimulus task) were constrained to present 87.5% of the relevant stimuli at image positions 1 & 4, 2 & 4, or 3 & 4. The remaining 12.5%, in which stimuli were presented at image positions 1 & 2, 1 & 3, or 2 & 3, were considered catch trials and were excluded from analysis. During both the Stimulus and Sequence tasks, the probe stimulus matched a previously presented stimulus during the cue period on 50% of the trials (randomized).

The Face Memory, Scene Memory and Passive View conditions were split into two blocks each (six blocks total), whereas the three Sequence conditions (remember images 1 & 4, 2 & 4 or 3 & 4) were presented as one block each (three blocks total). The presentation of all nine blocks (six conditions; Fig. 1) were randomized and counterbalanced across participants. All participants received 84 trials for each of the Stimulus, Sequence and Passive View tasks.

2.5 Data Acquisition

Participants sat in an armchair in a dark, sound-attenuated room and were monitored by a camera during all conditions. EEG data were recorded during all 9 blocks. The three Sequence conditions contained 28 trials each (excluding the 4 catch trials) and were collapsed to form 84 epochs for each of the four ERPs of interest (faces: attend and ignore & scene: attend and ignore). The two Stimulus conditions and the Passive view condition each elicited a total of 42 trials (excluding the 6 catch trials) that also produced 84 epochs for each of the six ERPs of interest (faces: attend and ignore, scene: attend and ignore, & passively view: faces and scenes) during the cue period. Electrophysiological signals were recorded with an ActiveTwo 64-channel Ag-AgCl active electrode EEG acquisition system (BioSemi) in conjunction with ActiView software (BioSemi). Signals were amplified and digitized at 1024 Hz with a 24-bit resolution. All electrode offsets were maintained between +/− 20 mV.

2.6 Data Analysis

Raw EEG data were referenced to the average off-line. Eye artifacts were removed through an independent component analysis by excluding components consistent with the electrooculogram time-series and topographies for blinks and eye movements. Epochs were extracted from the data beginning 200 ms pre-stimulus onset and ending 1000 ms post-stimulus onset. This preprocessing was conducted in Brain Vision Analyzer (Cortech Solutions, LLC) and exported to Matlab (The Mathworks, Inc.) for all subsequent analyses. The pre-stimulus baseline was subtracted from each epoch prior to calculating the ERP and a voltage threshold of +/−50 µV was used to reject epochs containing artifacts. ERPs were filtered between 1–30 Hz, following the methodology used in Gazzaley et al. (2008). In order to select electrodes for statistical analyses, we combined responses to all stimuli of one class (i.e. faces) that were viewed throughout the experiment, and chose the posterior electrode with the largest response at the group level. The electrodes of interest were PO8 for the P1, P10 for the N1 and PO8 for alpha band activity. Peak P1 values were chosen as the largest amplitude between 50–150 ms post-stimulus onset, and the N1 was identified as the most negative amplitude between 120–220 ms. All amplitudes were averaged +/− 5 ms around the peak prior to statistical analysis. Alpha band (8–12 Hz) activity was analyzed by resolving 4–30 Hz activity in the form of an event-related spectral perturbation (ERSP) through the complex Morlet wavelet as implemented by EEGLAB (Delorme and Makeig, 2004) and referenced to a pre-stimulus baseline. Statistical analysis for the ERP and spectral data consisted of planned two-tailed paired t-tests or a repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) as indicated in the results section. A Greenhouse-Geisser correction was applied when appropriate. Post-hoc analysis utilized two-tailed paired t-tests. All t-tests conducted were subject to a false discovery rate correction for multiple comparisons (Benjamini and Hochberg, 1995).

3. Results

3.1 Behavioral performance

Differences in WM accuracy and response times were compared between the tasks of this study using two-tailed paired t-tests. Accuracy performance of the older adults on the Sequence task (M = 90.7%, SEM = 2.0%) was not significantly different from their performance on the Stimulus task (M = 87.0%, SEM = 2.4%; t(20) = 1.81, p = .08), although there was a trend towards improvement. Additionally, response times to probe stimuli did not differ between the Stimulus (M = 1214 ms, SEM = 49 ms) and Sequence tasks (M = 1206 ms, SEM = 58 ms; t(20) = .25, p > .05). These results indicate that WM performance in older adults for face stimuli is not improved by knowledge of when relevant stimuli appear in the setting of distracting information.

3.2 Stimulus tasks: ERPs to cue stimuli

As previously mentioned, ERP analyses focused on the P1 amplitude and the N1 latency, as these were the markers of the suppression deficit observed in Gazzaley et al. (2008). ERPs to faces presented during the cue period of the Stimulus task conditions were analyzed using two-tailed paired t-tests to assess signatures of top-down enhancement (attend – passive) and suppression (ignore - passive). Figure 2a displays grand averages of ERPs time-locked to the onset of face stimuli for attended, ignored and passively viewed stimuli. Enhancement of the relevant stimuli was apparent as the P1 amplitude is larger when attended than when passively viewed (t(20) = 2.50, p < .05; Fig. 2b), and the N1 latency is earlier when attended to than when passively viewed (t(20) = −4.26, p < .0005; Fig. 2c). Suppression of the irrelevant stimuli was not present for either the P1 amplitude or the N1 latency. Interestingly, the P1 amplitude displayed the opposite effect, such that it was significantly greater for the ignored faces compared to the passively viewed faces (t(20) = −3.07, p < .01; Fig. 2b), suggesting that the distractor faces were actually enhanced. The N1 latency to ignored faces was not later than passively viewed faces (t(20) = −1.74, p > .05; Fig. 2c). These results replicate recently published findings that older adults do not display suppression at the P1 amplitude and N1 latency modulation indices (Gazzaley, Clapp et al., 2008).

Figure 2.

ERPs from the Stimulus task. a. The solid black line indicates attended faces, dashed black line indicates ignored faces and the solid gray line represents the passive view condition. Both the b. P1 amplitude and the c. N1 latency displays a suppression deficit.

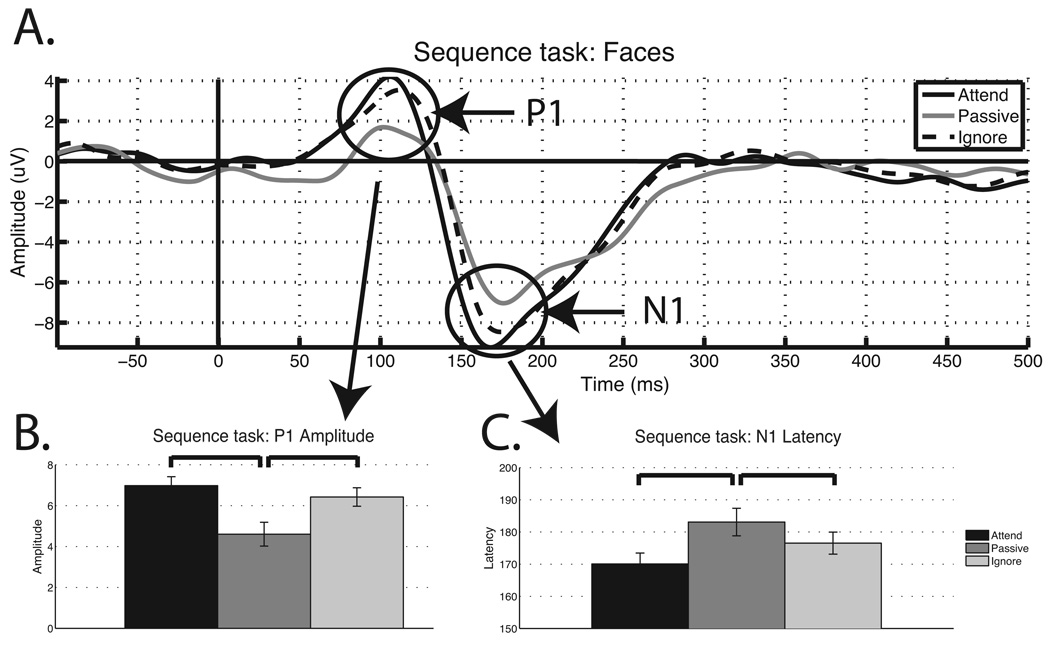

3.3 Sequence tasks: ERPs to cue stimuli

An ERP analysis that paralleled the one performed for the Stimulus task was conducted for the Sequence task. Figure 3a displays the grand averaged ERPs time-locked to face stimuli from the cue period that were attended, ignored and passively viewed. Enhancement of the relevant stimuli was evident as indicated by the P1 amplitude being larger when attended to than when passively viewed (t(20) = 5.67, p < .00005; Fig. 3b), and the N1 latency as being earlier when attended to than when passively viewed (t(20) = −4.71, p < .0005; Fig. 3c). As was found for the Stimulus task, suppression of irrelevant stimuli during the Sequence task was not present for either the P1 amplitude or the N1 latency. Once again, the P1 amplitude displayed enhancement for the distractor as opposed to suppression, as revealed by a greater P1 for ignored faces compared to passively viewed faces (t(20) = −4.15, p < .0005; Fig. 3b). The N1 latency to ignored faces was also earlier than passively viewed faces (t(20) = −2.29, p < .05; Fig. 3c). These results indicate that both the Stimulus and the Sequence tasks yield similar neural profiles of top-down modulation in older adults: enhancement of relevant information, but no suppression of irrelevant faces.

Figure 3.

ERPs from the Sequence task. a. The solid black line indicates attended faces, dashed black line indicates ignored faces and the solid gray line represents the passive view condition. Both the b. P1 amplitude and the c. N1 latency displays a suppression deficit.

3.4 Stimulus vs. Sequence tasks: ERPs to cue stimuli

To formalize the comparison between the Sequence and Stimulus tasks, a 2 × 2 ANOVA was conducted separately for the P1 amplitude and the N1 latency with task (Stimulus, Sequence) and condition (attend, ignore) as factors.

The P1 amplitude displayed a main effect of condition (F(1,20) = 10.11, p < .005), such that attending to relevant stimuli yielded a larger P1 amplitude than ignoring irrelevant stimuli. No other main effects or interactions were observed for the P1 amplitude. The absence of a condition by task interaction indicates that there was no significant benefit from temporal knowledge of stimulus relevance during the Sequence task on the P1 amplitude.

Similar to the P1 amplitude results, N1 latency analysis revealed a main effect of condition (F(1,20) = 32.63, p < .001), such that attending to relevant stimuli elicited an earlier N1 peak compared to ignoring irrelevant stimuli. No other main effects or interactions were observed for the N1 latency. This is consistent with the P1 result, suggesting that foreknowledge of stimulus relevance onset did not change the underlying neural activity at this early stage of visual processing.

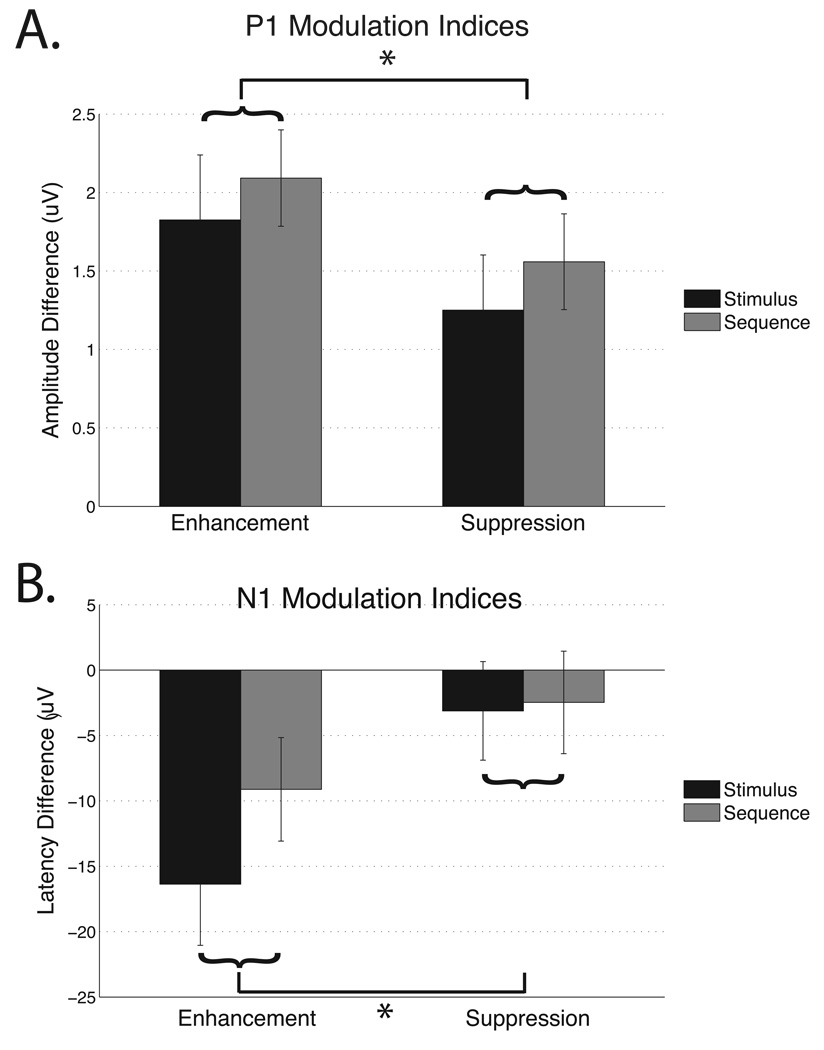

To further explore the relationship between the Sequence and Stimulus tasks, markers of attentional modulation were calculated for both enhancement and suppression by incorporating the passive view condition (enhancement = attend – passive, and suppression = ignore – passive). These indices were submitted to a 2 × 2 ANOVA separately for the P1 amplitude and the N1 latency with task (Stimulus, Sequence) and modulation (enhancement, suppression indices) as factors. The P1 amplitude displayed a main effect of modulation (F(1,20) = 10.11, p < .005; Fig. 4a), such that the degree of enhancement (M = 1.96 µV, SEM = .30 µV) was greater than the magnitude of suppression (M = 1.41 µV, SEM = .22 µV; t(20) = 3.18, p < .005). The absence of an interaction indicated that the magnitude of suppression as revealed by the P1 index was not different between the Sequence and Stimulus tasks. The N1 latency also displayed a modulation main effect (F(1,20) = 32.63, p < .0001; Fig. 4b), such that enhancement (M = −13 ms, SEM = −2 ms) was larger than suppression (M = −3 ms, SEM = 1 ms; t(20) = −5.71, p < .00005). Similar to the findings for the P1 amplitude, the lack of a modulation by task interaction for the N1 latency suggests that suppression abilities are not influenced by the temporal knowledge of stimulus relevance in older adults.

Figure 4.

Modulation indices for the a. P1 amplitude and b. N1 latency. Differences in the modulation main effect are marked by horizontal lines with an asterisk. Although the data shown separates the task conditions for display purposes only, curly brackets indicate that data were averaged together for the modulation main effect.

3.5 Spectral analysis

This analysis was aimed at following up on the previously published finding that older adults display the signature of neural suppression at later stages of processing, and test whether the magnitude of suppression changes with advance information on the order of appearance of relevant stimuli. To identify whether neural suppression in posterior electrodes occurs at later stages of processing in older adults, alpha band (8–12 Hz) desynchronization was tested using the same methodology as Gazzaley et al. (2008). Figure 5 displays spectral data from 4–30 Hz with a box drawn around the window of interest at 500–650 ms post-stimulus onset. Data from the window of interest was averaged and submitted to a 2 × 2 ANOVA with task (Stimulus, Sequence) and condition (attend, ignore) as factors. A condition main effect was observed (F(1,20) = 14.85, p < .005) such that attending to relevant stimuli elicited greater desynchronization than ignoring irrelevant stimuli. No main effect of task or interaction was observed, and so, markers of enhancement and suppression were averaged across the tasks (Fig. 6). A two-tailed paired t-test revealed significant enhancement (t(20) = −3.21, p < .005), suppression (t(20) = 2.88, p < .01) and overall modulation (t(20) = −4.81, p < .0005) in the alpha band at this late stage of processing. These results corroborate previous findings from young and older adults that suggested suppression of distracting information occurs successfully at later stages in older adults, and thus the suppression deficit is an early processing phenomenon.

Figure 5.

Spectral data from 4–30 Hz. The black box indicates the window of interest subject to analysis. Alpha desynchronization appears larger when attending to faces during both the a. Stimulus task and b. Sequence task compared to ignoring faces during the c. Stimulus task or d. Sequence task.

Figure 6.

Bar graphs of alpha desynchronization. Enhancement and suppression (relative to passive view) as well as overall modulation is observed.

4. Discussion

The current results replicate previous EEG findings that reveal older adults do not display significant suppression in the early visual processing of irrelevant information, as indicated by P1 amplitude and N1 latency modulation indices. Additionally, alpha band activity occurring later than 500 ms post-stimulus onset displays both enhancement and suppression to relevant and irrelevant stimuli, respectively. This provides further support that the previously reported absence of suppression in older adults is focused on early visual processes, and suppression is not abolished in aging, but rather delayed to later processing stages.

The goal of the current experiment was to elucidate whether neural suppression would be observed in older adults when foreknowledge of stimulus relevance regarding the ensuing stimuli was provided. It was hypothesized that providing this information would allow participants to maximize their potential for successful attentional modulation because they did not have to first recognize the stimuli and assess its relevance to the WM task prior to modulation. To the contrary, EEG analysis revealed that when the older participants were provided knowledge of when relevant / irrelevant stimuli would appear, the absence of significant suppression persisted using both the P1 amplitude and N1 latency markers. Additionally, no changes were observed in WM performance as well as any neural marker of attentional modulation when prior knowledge of stimulus relevance was provided. This suggests that participants utilized similar encoding mechanisms for the two tasks. Taken together, this suggests that the previously reported lack of suppression in older adults is not attributable to delays in the speed of stimulus recognition and relevancy assessment, but rather a specific decline in the mechanisms underlying the ability to filter irrelevant information. This conclusion further supports the inhibitory deficit hypothesis of cognitive aging (Hasher and Zacks, 1988; Hasher, Zacks et al., 1999) that attributes multiple facets of cognitive decline (notably WM) in older adults to an inability to suppress irrelevant information.

Although the current data support the inhibitory deficit hypothesis, these data still reveal delays in processing speed, which have also been theorized to underlie deficits in cognitive aging (Salthouse, 1996). Indeed, the suppression deficit is thought to be a consequence of a delay in suppressive mechanisms and not a loss of this ability (Gazzaley, Clapp et al., 2008). The possibility should be considered that the presentation rate of the stimuli might have been too rapid for the older adults to benefit from the prior knowledge. Time-accuracy functions have indicated that older adults require longer stimulus presentation times during cue periods in order to achieve recognition accuracies comparable to younger adults (e.g. Kliegl, Mayr et al., 1994; Verhaeghen, Kliegl et al., 1997). Thus, encoding processes may be delayed in aging to the extent that they overlap and thus interfere with suppression processes during the subsequent presentation of an irrelevant stimulus. However, this scenario seems unlikely because the task design required the final (4th) stimulus to be relevant, causing irrelevant stimuli to precede relevant stimuli more often than not. Another possibility is that older adults require more time during the inter-stimulus-interval to accommodate slower task switching processes from attend to ignore and vice versa. It has been shown that switching the focus of attention between WM stores results in an age-related decline in WM accuracy (Verhaeghen and Hoyer, 2007; Verhaeghen and Basak, 2005). Additionally, age-related declines in shifting attention have been observed through the use of visual search tasks (Lorenzo-Lopez, Amenedo et al., 2008a; Lorenzo-Lopez, Amenedo et al., 2008b). However, it has also been suggested from spatial cueing experiments that the efficiency of shifting attention is preserved in aging (Hartley, Kieley et al., 1990; Folk and Hoyer, 1992). Regardless, older adults may not have had enough time to engage preparatory suppression processes immediately prior to stimulus onset (Serences, Yantis et al., 2004). Future research will be required to address whether older adults would benefit from longer stimulus presentation times and longer inter-stimulus-intervals when irrelevant information is present.

The current data may also support the hypothesis of deficits in context processing in cognitive aging (Braver, Barch et al., 2001). Context refers to an internal representation of goals that biases processing in task-related neural pathways. Context representations are hypothesized to influence multiple stages of processing, including early stages such as interpretive or attentional processes, including inhibition, as well as later stages of WM maintenance and updating of contextual information. Here, task-related information did not change neural processing during encoding nor did it improve WM performance in older adults. However, in order to draw any conclusions regarding age-related differences, young control participants would be required.

It is interesting to note that the participants actually enhanced the P1 amplitude to irrelevant stimuli during the Stimulus task, which was not observed in the Gazzaley et al. (2008) study. The only methodological difference between the Stimulus task in the current study and the paradigm used in the previous study was that the original paradigm was unrestricted to when relevant and irrelevant stimuli could appear. The current study design required the final (4th) image to always be relevant, with the exception of rare catch trials that were not analyzed. Therefore, irrelevant stimuli were always required to be actively suppressed, as participants encoded the final relevant stimulus. It may be speculated that participants in the original study could passively view irrelevant stimuli that occurred in the fourth position, thereby leading to ERP measures more similar to the Passive View condition. This interpretation would imply that when older adults are required to actively attend or ignore stimuli, the default neural response is enhancement.

In the current experiment, the Stimulus task required stimulus recognition (i.e., is it a face or a scene?) and relevance assessment (i.e., should I try attempt to remember or ignore it?), whereas the Sequence task eliminated the need for these cognitive operations since the order of appearance of relevant stimuli was revealed prior to their presentation. EEG analysis revealed that the ability to anticipate the relevance of the stimuli to the WM task had no effect on early ERP markers of attentional modulation. It is reasonable to consider that this finding may be a reflection of a deficit in the ability of older adults to effectively use predictive cues to guide stimulus processing, especially since the neural suppression previously observed in younger adults occurs so early in visual processing. However, this ability is largely believed to be preserved in older adults (Hartley, Kieley et al., 1990; Nissen and Corkin, 1985; Madden, 2007). Moreover, without including a group of young participants, it is unclear whether these predictive cues can be utilized to influence these neural processes and/or WM performance. It is also possible that advantages gained by knowing the relevance of stimuli prior to their appearance, may have been offset by not knowing which stimulus type (faces or scenes) were relevant. Future research will aim to fully disclose the type of stimuli and the temporal order of relevance to optimize the potential for older adults to use predictive information to suppress irrelevant information.

The inability to effectively inhibit irrelevant information by older adults may also result in an inadvertent encoding of that information. This would subsequently overload a limited storage capacity (Hasher, Zacks et al., 1999; Vogel, McCollough et al., 2005; Zanto and Gazzaley, 2009), resulting in decreased WM performance. Indeed, incidental long-term memory of irrelevant information beyond that observed in the young adults was reported in the sub-group of older adults who displayed the smallest suppression index (Gazzaley, Cooney et al., 2005b). This potential advantage of encoding irrelevant information has been recently described (Rowe, Valderrama et al., 2006).

5. Conclusion

The current results replicate the finding that older adults do not exhibit the signatures of early neural suppression when viewing irrelevant stimuli,, but do enhance representations of relevant information. Moreover, the presence of alpha band suppression at later processing stages indicates that the lack of suppression is a phenomenon specifically related to early visual processing. It was hypothesized that the previously reported absence of early suppression in older adults may be due to delays in the assessment of stimulus relevance. However, in the current experiment, when older adults were informed which stimuli they should attend, and thus ignore, prior to the appearance of those stimuli, the absence of neural suppression persisted. Moreover, prior knowledge of stimulus relevance did not change any markers of attentional modulation or WM performance, suggesting participants did not use different neural resources. These results suggest that the previously reported age-related suppression deficit is not a consequence of delays in the assessment of stimulus relevance, but rather a specific impairment in the mechanisms responsible for filtering irrelevant information.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the National Institute of Health Grant R01-AG030395-01, the Ellison Medical Foundation and the American Federation for Aging Research. Thanks to Naomi Kort for her assistance in data collection. A special thanks to Ezequiel Morsella and Chips Steeley for their insightful comments.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Bar M. A cortical mechanism for triggering top-down facilitation in visual object recognition. J Cogn Neurosci. 2003;15:600–609. doi: 10.1162/089892903321662976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate - a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society Series B-Methodological. 1995;57:289–300. [Google Scholar]

- Braver TS, Barch DM, Keys BA, Carter CS, Cohen JD, Kaye JA, Janowsky JS, Taylor SF, Yesavage JA, Mumenthaler MS, Jagust WJ, Reed BR. Context processing in older adults: Evidence for a theory relating cognitive control to neurobiology in healthy aging. J Exp Psychol Gen. 2001;130:746–763. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delis DC, Kramer JH, Kaplan E, Ober BA. California verbal learning test. San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Delorme A, Makeig S. Eeglab: An open source toolbox for analysis of single-trial eeg dynamics including independent component analysis. Journal of Neuroscience Methods. 2004;134:9–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2003.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eriksen CW, Hoffman JE. Selective attention - noise suppression or signal enhancement. Bulletin of the Psychonomic Society. 1974;4:587–589. [Google Scholar]

- Folk CL, Hoyer WJ. Aging and shifts of visual spatial attention. Psychology and Aging. 1992;7:453–465. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.7.3.453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- "Mini-mental state". Folstein MF, Folstein SE, Mchugh PR. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12:189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frith C. A framework for studying the neural basis of attention. Neuropsychologia. 2001;39:1367–1371. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3932(01)00124-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gazzaley A, Clapp W, Kelley J, Mcevoy K, Knight R, D'esposito M. Age-related top-down suppression deficit in the early stages of cortical visual memory processing. Proceedings of the National Academy of Science USA. 2008;105:13122–13126. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0806074105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gazzaley A, Cooney JW, Mcevoy K, Knight RT, D'esposito M. Top-down enhancement and suppression of the magnitude and speed of neural activity. J Cogn Neurosci. 2005a;17:507–517. doi: 10.1162/0898929053279522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gazzaley A, Cooney JW, Rissman J, D'esposito M. Top-down suppression deficit underlies working memory impairment in normal aging. Nat Neurosci. 2005b;8:1298–1300. doi: 10.1038/nn1543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez gonzalez CM, Clark VP, Fan S, Luck SJ, Hillyard SA. Sources of attention-sensitive visual event-related potentials. Brain Topography. 1994;7:41–51. doi: 10.1007/BF01184836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartley AA, Kieley JM, Slabach EH. Age-differences and similarities in the effects of cues and prompts. Journal of Experimental Psychology-Human Perception and Performance. 1990;16:523–537. doi: 10.1037//0096-1523.16.3.523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasher L, Zacks RT. Working memory, comprehension and aging: A review and a new view. In: Bower GH, editor. The psychology of learning and motivation. New York, NY: Academic Press; 1988. pp. 193–225. [Google Scholar]

- Hasher L, Zacks RT, May CP. Inhibitory control, circadian arousal, and age. Attention and Performance Xvii - Cognitive Regulation of Performance: Interaction of Theor and Application. 1999;17:653–675. [Google Scholar]

- Hillyard SA, Anllo-vento L. Event-related brain potentials in the study of visual selective attention. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:781–787. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.3.781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hillyard SA, Vogel EK, Luck SJ. Sensory gain control (amplification) as a mechanism of selective attention: Electrophysiological and neuroimaging evidence. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1998;353:1257–1270. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1998.0281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jordan TC, Rabbitt PMA. Response-times to stimuli increasing complexity as a function of aging. British Journal of Psychology. 1977;68:189–201. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8295.1977.tb01575.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kastner S, Ungerleider LG. The neural basis of biased competition in human visual cortex. Neuropsychologia. 2001;39:1263–1276. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3932(01)00116-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kliegl R, Mayr U, Krampe RT. Time accuracy functions for determining process and person differences - an application to cognitive aging. Cognitive Psychology. 1994;26:134–164. doi: 10.1006/cogp.1994.1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kok A. Age-related changes in involuntary and voluntary attention as reflected in components of the event-related potential (erp) Biol Psychol. 2000;54:107–143. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0511(00)00054-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorenzo-lopez L, Amenedo E, Cadaveira F. Feature processing during visual search in normal aging: Electrophysiological evidence. Neurobiology of Aging. 2008a;29:1101–1110. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2007.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorenzo-lopez L, Amenedo E, Pascual-marqui RD, Cadaveira F. Neural correlates of age-related visual search decline: A combined erp and sloreta study. Neuroimage. 2008b;41:511–524. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.02.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madden DJ. Aging and visual attention. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2007;16:70–74. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8721.2007.00478.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller MM, Keil A. Neuronal synchronization and selective color processing in the human brain. J Cogn Neurosci. 2004;16:503–522. doi: 10.1162/089892904322926827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nissen MJ, Corkin S. Effectiveness of attentional cueing in older and younger adults. Journals of Gerontology. 1985;40:185–191. doi: 10.1093/geronj/40.2.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pessoa L, Kastner S, Ungerleider LG. Neuroimaging studies of attention: From modulation of sensory processing to top-down control. J Neurosci. 2003;23:3990–3998. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-10-03990.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ploner CJ, Ostendorf F, Brandt SA, Gaymard BM, Rivaud-pechoux S, Ploner M, Villringer A, Pierrot-deseilligny C. Behavioural relevance modulates access to spatial working memory in humans. Eur J Neurosci. 2001;13:357–363. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Posner MI, Snyder CRR, Davidson BJ. Attention and the detection of signals. Journal of Experimental Psychology-General. 1980;109:160–174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rainer G, Asaad WF, Miller EK. Selective representation of relevant information by neurons in the primate prefrontal cortex. Nature. 1998;393:577–579. doi: 10.1038/31235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reitan R. Validity of the trail making test as an indicator of organic brain damage. Perceptual and Motor Skills. 1958;8:271–276. [Google Scholar]

- Rowe G, Valderrama S, Hasher L, Lenartowicz A. Attentional disregulation: A benefit for implicit memory. Psychology and Aging. 2006;21:826–830. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.21.4.826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rugg MD, Milner AD, Lines CR, Phalp R. Modulation of visual event-related potentials by spatial and nonspatial visual selective attention. Neuropsychologia. 1987;25:85–96. doi: 10.1016/0028-3932(87)90045-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutman AM, Clapp WC, Chadick JZ, Gazzaley A. Early top-down control of visual processing predicts working memory performance. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. doi: 10.1162/jocn.2009.21257. In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salthouse TA. The processing-speed theory of adult age differences in cognition. Psychol Rev. 1996;103:403–428. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.103.3.403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serences JT, Yantis S, Culberson A, Awh E. Preparatory activity in visual cortex indexes distractor suppression during covert spatial orienting. Journal of Neurophysiology. 2004;92:3538–3545. doi: 10.1152/jn.00435.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stroop JR. Studies of interference in serial verbal reactions. Journal of Experimental Psychology. 1935;18:643. [Google Scholar]

- Surwillo W. Timing of behavior in senescence and the role of the cns. In: Talland GA, editor. Human aging and behavior. London: Academic Press; 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Tombaugh TN. Trail making test a and b: Normative data stratified by age and education. Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology. 2004;19:203–214. doi: 10.1016/S0887-6177(03)00039-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valdes-sosa M, Bobes MA, Rodriguez V, Pinilla T. Switching attention without shifting the spotlight: Object-based attentional modulation of brain potentials. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 1998;10:137–151. doi: 10.1162/089892998563743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verhaeghen P, Basak C. Ageing and switching of the focus of attention in working memory: Results from a modified n-back task. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology Section a-Human Experimental Psychology. 2005;58:134–154. doi: 10.1080/02724980443000241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verhaeghen P, Hoyer WJ. Aging, focus switching, and task switching in a continuous calculation task: Evidence toward a new working memory control process. Aging Neuropsychology and Cognition. 2007;14:22–39. doi: 10.1080/138255890969357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verhaeghen P, Kliegl R, Mayr U. Sequential and coordinative complexity in time-accuracy functions for mental arithmetic. Psychology and Aging. 1997;12:555–564. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.12.4.555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogel EK, Mccollough AW, Machizawa MG. Neural measures reveal individual differences in controlling access to working memory. Nature. 2005;438:500–503. doi: 10.1038/nature04171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler D. Wechsler adult intelligence scale-revised manual. New York: The Psychological Corporation; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Yesavage JA, Brink TL, Rose TL, Lum O, Huang V, Adey M, Leirer VO. Development and validation of a geriatric depression screening scale: A preliminary report. J Psychiatr Res. 1982;17:37–49. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(82)90033-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zanto TP, Gazzaley A. Neural suppression of irrelevant information underlies optimal working memory performance. Journal of Neuroscience. 2009;29:3059–3066. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4621-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zanto TP, Toy B, Gazzaley A. Delays in neural processing during working memory encoding in normal aging. Neuropsychologia. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2009.08.003. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]