Abstract

Estradiol (E2), estrogen receptor (ER), ER-coregulators have been implicated in the development and progression of breast cancer. In situ E2 synthesis is implicated in tumor cell proliferation through autocrine or paracrine mechanisms, especially in post-menopausal women. Several recent studies demonstrated activity of aromatase P450 (Cyp19), a key enzyme that plays critical role in E2 synthesis in breast tumors. The mechanism by which tumors enhance aromatase expression is not completely understood. Recent studies from our laboratory suggested that PELP1 (Proline, Glutamic acid, Leucine rich Protein 1), a novel ER coregulator, functions as a potential proto-oncogene and promotes tumor growth in nude mice models without exogenous E2 supplementation. In this study, we found that PELP1 deregulation contributes to increased expression of aromatase, local E2 synthesis and PELP1 cooperates with growth factor signaling components in the activation of aromatase. PELP1 deregulation uniquely upregulated aromatase expression via activation of aromatase promoter I.3/II. Analysis of PELP1 driven mammary tumors in xenograft as well as in transgenic mouse models revealed increased aromatase expression. PELP1-mediated induction of aromatase requires functional Src and PI3K pathways. Chromatin immuno precipitation (ChIP) assays revealed that PELP1 is recruited to the Aro 1.3/II aromatase promoter. HER2 signaling enhances PELP1 recruitment to the aromatase promoter and PELP1 plays a critical role in HER2-mediated induction of aromatase expression. Mechanistic studies revealed that PELP1 interactions with orphan receptor ERRα, and histone demethylases play a role in the activation of aromatase promoter. Accordingly, ChIP analysis showed alterations in histone modifications at the aromatase promoter in the model cells that exhibit local E2 synthesis. Immunohistochemical analysis of breast tumor progression tissue arrays suggested that deregulation of aromatase expression occurs in advanced-stage and node-positive tumors, and that cooverexpression of PELP1 and aromatase occur in a sub set of tumors. Collectively, our results suggest that PELP1 regulation of aromatase represent a novel mechanism for in situ estrogen synthesis leading to tumor proliferation by autocrine loop and open a new avenue for ablating local aromatase activity in breast tumors.

Keywords: Estrogen, Estrogen receptor, Coregulators, Aromatase, ERRα, PELP1, Breast cancer, epigenetics

1. Introduction

Mammary tumorigenesis is accelerated by the action of ovarian hormones, and approximately 70% of breast tumors are ER-positive at the time of presentation. Endocrine therapy is the most important component of adjuvant therapy for patients with early stage ER–positive breast cancer [1]. The biological functions of estrogens are mediated by the nuclear receptor ER, a ligand-dependent transcription factor that modulates gene transcription via direct recruitment to the target gene chromatin. In addition, ER also participates in cytoplasmic and membrane-mediated signaling events (nongenomic signaling) and generally involves cytosolic kinases including Src, MAPK, PI3K [2;3]. Accumulating evidence strongly suggest that ER signaling requires coregulatory proteins and their composition in a given cell determine the magnitude and specificity of the ER signaling [4;5]. Coregulators function as multitasking molecules and appear to participate in a wide variety of actions including remodeling and modification of chromatin [6]. Coregulators appear to have the potential to sense the physiological signals [7] and activate appropriate set of genes, thus have potential to function as master regulators, and their deregulation is likely to provide cancer cells an advantage in survival, growth and metastasis [8;9]. A commonly emerging theme is that marked alteration in the levels and functions of coregulators occurs during the progression of tumorigenesis [10]. Although much is known about the molecular basis of interaction between ER and coregulators, very little is known about the physiological role of coregulators in the initiation and progression of cancer.

2. Regulation of aromatase in Breast

Aromatase (Cyp19), a key enzyme involved in E2 synthesis [11], is expressed in breast tumors and locally produced E2 might act in a paracrine or autocrine fashion [12]. Breast tumors from postmenopausal women are shown to contain higher amounts of E2 than would be predicted from levels circulating in plasma [13]. Expression of the aromatase gene is under the control of several distinct and tissue-specific promoters; however, the coding region of aromatase transcripts and the resulting protein is identical [14]. In disease free breast, aromatase expression is directed via distal 1.4 promoter, while aromatase expression is shown to be activated via PII and 1.3 in adipose tissue and epithelial cells in breast bearing tumor[15-17]. Recently, aromatase inhibitors that inhibit peripheral E2 synthesis are shown to be more effective in enhancing the survival of postmenopausal women with ER+ve breast cancer [18]. Even though these new treatments appear successful, emerging data suggest that tumors evade this treatment by developing “adaptive hypersensitivity” manifested as hormone-independent tumorigenesis through increased non-genomic signaling and growth factor signaling crosstalk [19-21]. Recent studies also demonstrated that HER2 status plays an important role in tumor-induced aromatase activity via the COX-2 pathway [22]. Further, HER2 overexpression can also promote ligand-independent recruitment of coactivator complexes to E2-responsive promoters, and thus may play a role in the development of letrozole resistance [21]. Accumulating evidence also suggest that a variety of different factors may regulate expression and activity of aromatase under pathological conditions and local production of estrogen may enhance tumor growth and may also interfere with hormone therapy [23]. The molecular mechanism by which breast tumors enhance local aromatase expression and whether epigenetic changes play a role in activation of aromatase in tumors remain unknown and is an active area of research investigation.

3. PELP1, a novel ER coregulator

Proline, glutamic acid, leucine rich protein 1 (PELP1), also called as a modulator of nongenomic actions of estrogen receptor (MNAR) is a novel ER coregulator [24] [25]. PELP1 contains several motifs and domains that are commonly present in many transcriptional coactivators, including 10 nuclear receptor (NR)-interacting boxes (LXXLL motifs), a zinc finger motif, a glutamic acid-rich domain, and 2 proline-rich domains (Figure 1) [24;25]. A unique feature of PELP1 is the presence of an unusual stretch of 70 acidic amino acids in the C-terminus that functions as a histone-binding region [26;27]. PELP1 is localized both in the nuclear and cytoplasmic compartments. In the nuclear compartment PELP1 interacts with histones and histone modifying enzymes, suggesting that PELP1 has some function in these complexes [28;29] and thus plays a role in chromatin remodeling for ligand-bound ERs [27]. Emerging evidence also indicates that PELP1 plays a key role in extra nuclear actions of nuclear receptors and thus represents a unique ER coregulator that participates in both genomic and non genomic actions of ER. PELP1 modulates the interaction of estrogen receptor with Src, stimulates Src enzymatic activity and thus enhances MAPK pathway activation [25]. PELP1 is also shown to directly interact with the p85 subunit of PI3K and enhances PI3K activity, leading to activation of the PKB/AKT pathway [30]. Mechanistic studies showed that PELP1 interacts with the SH3 domain of c-Src via its N-terminal PXXP motif, and ER interacts with the SH2 domain of Src at phosphotyrosine 537; the PELP1-ER interaction further stabilizes this trimeric complex, leading to activation of Src kinase. Activated Src kinase then phosphorylates PELP1, which in turn acts as a docking site for PI3K leading to activation of PKB/AKT pathway [31]. PELP1 interacts with and modulates functions of several nuclear receptors and transcriptional activators including AR, ERR, GR, PR, RXR, FHL2 and STAT3 [28]. PELP1 promotes E2-mediated cell proliferation by sensitizing cells to G1>S progression via its interactions with the pRb pathway [32]. PELP1 is shown to be phosphorylated by several kinases including PKA, HER2, Src, CDKs and its phosphorylation is modulated by estrogen and growth factors [28]. Collectively, these findings suggest that PELP1 serves as a scaffolding protein that couples various signaling complexes with estrogen receptor and participates in genomic and non-genomic functions (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Schematic representation of the current understanding of PELP1 signaling pathway. PELP1 participates in NR non-genomic signaling by coupling NRs with cytosolic kinases (Src and PI3K) and growth factor signaling components. PELP1 contains 10 LXXLL (NR interacting motifs) and interacts with several nuclear receptors (ER, ERR, GR, PR, AR, RXR). PELP1 interacts with histones and histone modifying enzymes (including CBP, P300, HDAC2, LSD1) and promotes chromatin remodeling. PELP1 interacts with pRb, is phosphorylated by CDKs and plays a role in NR mediated cell cycle progression.

4. PELP1 expression in hormonal cancers

Emerging studies suggest that PELP1 is a proto-oncogene and its expression is deregulated in hormone dependent cancers including cancers of breast [24;33], endometrium [34] and ovary [35]. Although PELP1 is predominantly localized in the nuclei of hormonally responsive tissue cells, in a subset of tumors it localizes in the cytoplasm alone [30]. Altered localization of PELP1 appears to contribute to tamoxifen resistance via excessive activation of Src/AKT pathways leading to follow-up modifications of ER [30]. Such modifications of the ER pathway may lead to the activation of ER target genes in a ligand-independent manner. Thus, deregulation of PELP1 expression has the potential to contribute to hormonal therapy resistance seen in patients with hormone-dependent neoplasm by excessively activating extra nuclear signaling pathways.

5. PELP1 deregulation promotes local induction of aromatase

Recent studies from our laboratory showed that PELP1 functions as a potential proto-oncogene [36]. In this study, we found that breast cancer cells stably overexpressing PELP1 showed a rapid tumor growth in xenograft studies compared to control vector transfectants and tumor growth in PELP1 clones occurred in the absence of external estrogen supplementation. These findings raised a hypothesis that PELP1 deregulation modulates local aromatase to produce local estrogen thus promoting tumor growth without exogenous E2 supplementation. Immunohistochemistry (IHC) analysis of the PELP1 induced xenograft tumors using aromatase specific antibody showed that PELP1 driven tumors have increased aromatase expression compared to control E2 induced MCF-7 tumors (Fig. 2A). Results from studies using exon specific primers showed that MCF7 clones that overexpress PELP1 showed increased levels of exon I.3/II transcripts compared to MCF7 parental clones. In reporter gene assays utilizing Aro 1.3/II-luc, MCF7-PELP1 cells showed a 5-fold increase in the reporter gene activity (Fig. 2B). Western blot analysis showed that MCF7-PELP1 clones have increased levels of aromatase compared to the aromatase levels in the control MCF7 cells (Fig.2B). PELP1 expressing MCF7 cells also showed increased aromatase activity suggesting the functionality of induced aromatase (Fig.2C). Collectively, these results suggest that PELP1 deregulation has potential to regulate the aromatase gene expression via the I.3/PII promoter and such deregulation could contribute to local E2 synthesis.

Fig. 2.

PELP1 deregulation promotes local E2 synthesis. A, IHC staining of aromatase in E2 induced and PELP1 induced xenograft tumors. B, MCF7 cells or MCF7-PELP1 were transiently transfected with Aro1.3/II promoter and after 48h, reporter activity was measured. Total cell lysates from MCF7 cells stably expressing vector or PELP1 were analyzed for aromatase expression by Western. C, Aromatase activity in control MCF7 cells and MCF7-PELP1 clones was measured by tritiated-water release assay. D, Co-expression of PELP1 and aromatase in breast tumors. PELP1 and aromatase expression was determined by IHC using breast cancer TMA arrays. Sections were scored according to IHC intensity in a range from 0 to 3, in which 0 indicated no expression; 1, low expression; and 2, moderate expression; 3 high expression. Summary of the staining is shown as a table. A representative sample of one tumor with high expression of PELP1 and aromatase is shown. e, schematic representation of construct used to generate Tg mouse. B, PELP1 Tg mice (8 months old) with mammary tumor and age matched WT mice control mammary glands were analyzed for morphological changes using H&E and aromatase expression by IHC. F, PELP1 modulates aromatase expression endometrial model cells. Immortalized human endometrial stromal cells (HESC) were transiently transfected with GFP vector or GFP-PELP1 expression vectors along with aromatase 1.3/II luciferase reporter. Reporter activity and expression of aromatase was measured after 72 hours. G, Expression status of PELP1 and aromatase in eutopic and ectopic endometrium determined by IHC. H, A representative sample of PELP1 staining in normal and serous ovarian tumor is shown. I, BG 1 ovarian cancer cells were transiently transfected with Aro1.3/II promoter along with increasing amount of PELP1. After 72h, reporter activity was measured. J, Total cell lysates from BG1 cells stably expressing vector or PELP1 were analyzed for aromatase expression by Western.

7. Role of PELP1 in growth factor regulation of Aromatase

Deregulation of HER2 oncogene expression/signaling has emerged as the most significant factor in the development of hormone resistance. ER expression occurs in ∼50% HER2-positive breast cancers and cross-talk between the ER and HER2 pathways promotes endocrine therapy resistance [37]. ER-coregulators are targeted by excessive ER-HER2 crosstalk leading to hormone resistance in a subset of breast tumors [38]. Recent studies also demonstrated that HER2 status plays an important role in tumor-induced aromatase activity via the COX-2 pathway [22]. Earlier studies showed that PELP1 interacts with HER2 and EGFR signaling components, and HER signaling promotes tyrosine phosphorylation of PELP1 [34;39]. In our studies, we found that growth factor signaling enhances PELP1 regulation of the aromatase promoter and resulted in increased aromatase activity [40]. We also found that PELP1 overexpression, or growth factor signaling enhances PELP1 recruitment to the silencer regions of the promoter I.3/II, suggesting that PELP1 could be one of those factors that promote aromatase expression via activation of the 1.3/II promoters under conditions of growth factor deregulation (Fig. 3).

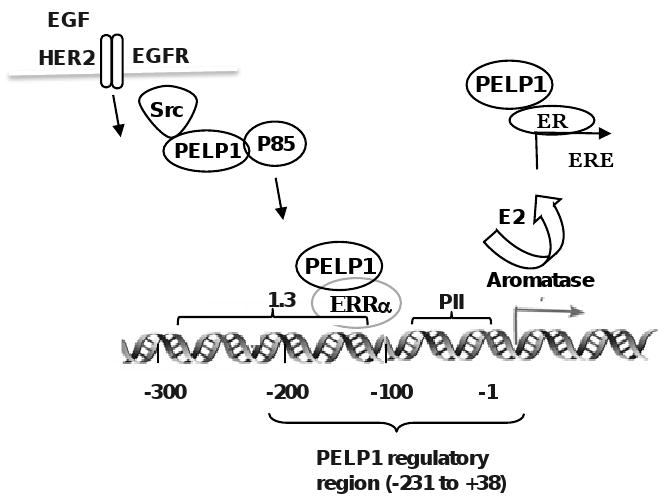

Fig. 3.

Schematic representation of PELP1 regulation of aromatase promoter. Growth factor signals or PELP1 deregulation via overexpression promotes PELP1 recruitment to aromatase promoter (-213 to +38 region). At the aromatase promoter, PELP1 interactions with orphan receptor ERRα in conjunction with histone modifying enzymes promotes aromatase expression leading to E2-ER autocrine signaling loop.

8. Expression of PELP1 and aromatase in breast tumors

Since PELP1 deregulation promotes aromatase expression in breast epithelial cells, we investigated whether aromatase expression is deregulated in breast tumors and whether its expression correlates with PELP1 expression using a breast cancer tissue microarrays (TMAs) obtained from the Cooperative Breast Cancer Tissue Resource (CBCTR) of the National Cancer Institute (NCI). IHC analysis of the breast tumor arrays showed increased expression of aromatase in DCIS and node positive tumors compared to no or weak expression in normal breast tissue. PELP1 expression positively correlated with cancer grade and node status. The number of samples with a high level (score 3) of PELP1 staining increased as tumors progressed from grade 1 to grade 2 or 3. Interestingly, tumors that showed increased expression of PELP1 also showed increased aromatase expression compared to PELP1 low expressing tumors (Fig. 2D). Collectively, these results suggested that deregulation of aromatase expression occurs in advanced-stage and node-positive tumors, and that cooverexpression of PELP1 and aromatase may occur in a sub set of tumors [40].

9. PELP1 regulation of aromatase expression in vivo

To test whether PELP1 deregulation in vivo has potential to regulate aromatase expression, our laboratory recently developed a transgenic mice (Tg) model. As a means of targeting the expression of the PELP1 transgene to the mammary gland, we placed the PELP1-cDNA under the control of the MMTV promoter. In this MMTV-PELP1 Tg model, mammary tumors were observed as early as 24 weeks and at this stage >40% of mice (n=16) developed mammary tumors by 8 months. No spontaneous mammary tumors were found in the wild type cohort. Pathological analysis revealed that these tumor masses represent full blown mammary adenocarcinomas. PELP1 driven tumors are ER+ve, and express aromatase, while wild type age matched control did not show any aromatase expression (Fig. 2E). These results thus provide evidence for in vivo potential of PELP1 deregulation in enhancing local E2 synthesis.

10. PELP1 and aromatase expression in endometriosis

Several lines of evidence demonstrate local estradiol (E2) production in endometriosis lesions [41;42]. Aberrant expression of steroidogenic acute regulatory protein (StAR) and aromatase in endometriotic tissue is shown to result in up-regulation of estrogen production [43]. Evolving evidence indicate that in cancers of breast, endometrium and ovary, aromatase expression is primarily regulated by increased activity of the proximally located promoter AroI.3/II region [44]. To examine whether PELP1 has potential to regulate aromatase expression in endometrial cells, we performed reporter gene activation assays. Cotransfection of GFP-PELP1 but not GFP vector in human endometrial stromal cells (HESC) showed increased aromatase reporter activity and expression (Fig. 2F). Since PELP1 expression is deregulated in some ER driven pathological situations, we examined the expression status of PELP1 and aromatase in a small number (n=5) of eutopic and ectopic endometrium. Results showed increased staining intensity of PELP1 in ectopic endometrium compared to eutopic endometrium (Fig. 2G). In addition, ectopic endometrium also showed increase in aromatase staining. Collectively, these results suggest a possibility that PELP1 has potential to modulate aromatase expression in endometrial cells and it expression may be deregulated in endometriosis.

11. PELP1 regulation of aromatase in ovarian cancer cells

Our recently completed study using ovarian cancer tissue arrays suggested that PELP1 deregulation occurs in different types of ovarian cancer [35]. Results suggested that deregulation of PELP1 occurs in all subtypes of ovarian cancer (including serous, endometerioid, clear cell carcinoma, and mucinous tumors) and 60 % of the tumors have 2-3 fold increase in PELP1 staining intensity (Fig. 2H). Since emerging evidence implicates that local estrogen synthesis also play a role in ovarian tumorigenesis, we have examined whether PELP1 regulates aromatase activation in ovarian cancer cells using Aro1.3/II promoter that is shown to be active in ovarian cells. In reporter gene assays, PELP1 enhanced the activation of Aro 1.3/II promoter activity in BG1 cells in a dose dependent manner (Fig. 2I). Western analysis of PELP1 overexpressing BG1 clones showed that PELP1 overexpression increases aromatase expression in ovarian cancer cells (Fig. 2J). These results suggest that PELP1 deregulation also has potential to promote local E2 synthesis in ovarian cancer cells.

12. Role of PELP1 mediated non-genomic actions in aromatase induction

PELP1 is a unique regulator of nuclear receptor that participates in genomic as well as in non-genomic actions [28]. To examine whether PELP1 mediated non-genomic signaling pathways are involved in PELP1-mediated induction of aromatase expression, we pretreated MCF7-PELP1 cells with various signaling inhibitors that block specific pathways: PD98059, mitogen-activated protein/extracellular signal-regulated kinase inhibitor; PP2, the Src family tyrosine kinase inhibitor; LY-294002, the PI3K inhibitor; SB203580, and the p38MAPK inhibitor. Results from these assays showed that PELP1-induced aromatase promoter activity can be abolished by pretreatment with c-Src or PI3K pathway inhibitors while pretreatment of MAPK pathway inhibitors had no effect on PELP1-induced aromatase expression. These results suggest that functional c-Src and PI3K pathways are required for PELP1-mediated induction of aromatase (Fig. 3). Similarly, HER2 regulation of PELP1-mediated activation of aromatase was also abolished by pretreatment of MCF7-HER2 cells with the Src inhibitor PP2. Collectively, the findings from this published study suggest that c-Src signaling plays a vital role in PELP1 mediated induction of aromatase [40].

13. Role of PELP1 genomic functions in aromatase induction

PELP1 is predominantly nuclear in localization and earlier studies showed that PELP1 is recruited to several nuclear receptor target genes and play a role in chromatin modifications. Using various deletion constructs of aromatase promoter reporter gene and by ChIP analysis of aromatase promoter, we found that 269 base region located in the -231/+38 Aro P1.3/II promoter is required for PELP1 regulation of aromatase (Fig. 3). In addition, ChIP analysis showed that PELP1 is specifically recruited to the -231/+38 region. Further analysis revealed that HER2 signaling also required Aro 1.3/II -231/+38 region for PELP1-mediated activation of aromatase. Earlier studies showed that this region possess binding regions for ERRα, BRCA1 and a transcriptional silencer element (S1) [45]. Immunoprecipitation analysis revealed that PELP1 interacts with ERRα but not with BRCA1. Using reporter gene assays, ERRα specific siRNA and ERRα antagonist, we found that PELP1 promotes activation of Aro1.3/II promoter via interactions with the ERRα [40]. Earlier studies found that ERRα up-regulates aromatase expression via the I.3/II promoters [46]. Since PELP1 does not have a DNA binding domain, it is possible that ERRα serves as a docking site for PELP1 recruitment and PELP1 ability to interacts with histones and histone modifying enzymes, may play a role in chromatin remodeling at aromatase promoter (Fig. 3)

14. Significance of PELP1 in epigenetic modifications of aromatase promoter

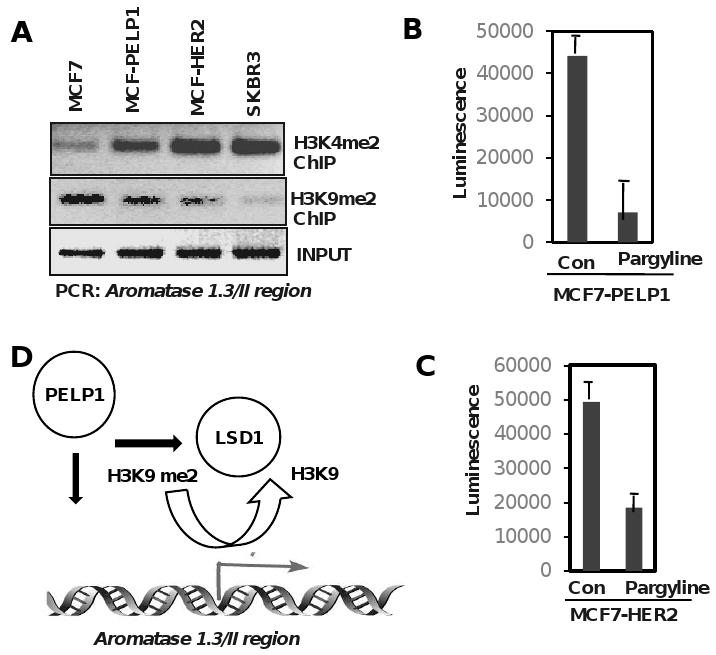

Emerging evidence suggest that histone methylation, an epigenetic phenomena, could play a vital role in many neoplastic processes by silencing or activation of genes [47]. However, unlike genetic alterations, epigenetic changes are reversible. Recent studies showed that demethylase LSD1 can demethylate H3-K4 and H3-K9, recruits to a significant fraction of ER target genes and is shown to be required to demethylate proximal histones to enable ER-mediated transcription [48]. Evolving studies in our laboratory suggest that PELP1 interacts with LSD1 and also recognizes methyl modified histones [49] [28]. Because PELP1 is recruited to aromatase promoter and interacts with histone demethylase, it is possible that PELP1 modulate H3 methyl modifications at the aromatase promoter. ChIP analysis revealed that MCF7 cells that do not express aromatase showed increased H3K9 methylation (a marker of repression), while MCF7-PELP1 model cells (that overexpress PELP1) that exhibit local E2 synthesis showed decreased histone H3K9 with a concomitant increase in H3K4 methylation (a marker of activation) at the aromatase promoter. Interestingly, other model cells that exhibit increased local E2 synthesis (MCF7-HER2, SKBR3) also showed increased H3K4 methylation at aromatase promoter (Fig. 4A). These results suggest that epigenetic modification may play a role in the local aromatase expression and PELP1 deregulation could play a role in modulating histone methylation at the aromatase promoter region.

Fig. 4.

PELP1 promotes epigenetic modifications at the aromatase promoter. A, Chromatin immune precipitation (ChIP) was performed using H3K9me2, K3K4me2 specific antibodies in indicated cells and the status of H3 methylation was analyzed by PCR using aromatase 1.3/PII promoter specific primers. B, MCF7–PELP1, MCF7-HER2 cells were cultured in a 94 well plate and treated with 3 mM of Pargyline for 72 hours. Cell viability was measured by ATP assay (Promega, Cell Titer Glo ATP assay).

15. Targeting local estrogen synthesis by blocking PELP1-LSD1 axis

Pargyline is a selective monoamine oxidase inhibitor that blocks LSD1 activity [50] and is approved by FDA for treatment of moderate to severe hypertension. Pargyline is commercially available from many sources and the safety and efficacy of this drug is well established. Since PELP1 expression is deregulated in hormonal dependent tumors, and because PELP1 interacts with LSD1 and promotes local E2 synthesis, inhibition of PELP1-LSD1 axis by inhibitor Pargyline will probably affect growth advantage seen in the PELP1 overexpressing cells by reducing local E2 synthesis. To test this, MCF7-PELP1 cells that over express PELP1, MCF7-HER2 cells that overexpress oncogene HER2, were treated with or without Pargyline (3 mM) for 72 h and the cell viability was determined by Cell titer-glo ATP assay (Promega). Pargyline substantially inhibited viability in both model cells (Fig. 4B, C). These results suggest that PELP1 mediated epigenetic modifications may play a role in local E2 synthesis and blocking PELP1-LSD1 axis will have therapeutic utility (Fig. 4D).

16. Concluding Comments

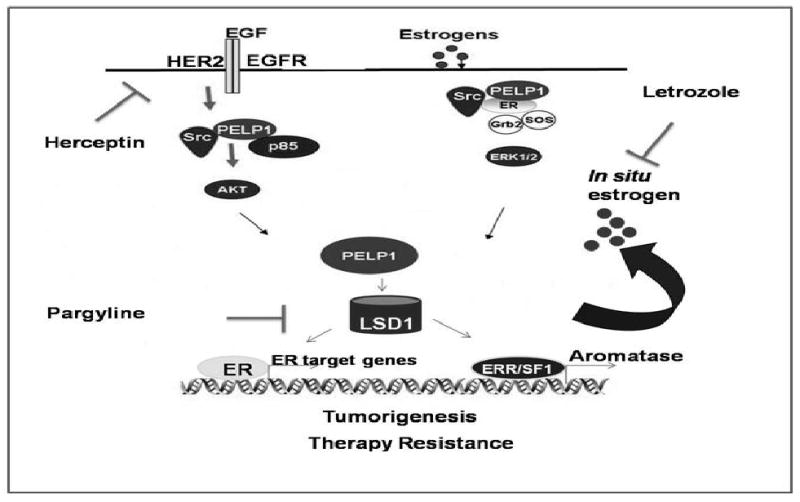

Understanding the molecular mechanism by which tumors enhance aromatase expression is clinically important. Accumulating evidence suggest that a variety of different factors may regulate expression and activity of aromatase under pathological conditions and that aromatase promoter I.3 and II as the main promoters that regulate aromatase expression in breast tumors. Earlier studies using elegant methodology identified several nuclear factors (BRCA, ERRα), signals (Cytokines, PGE2), oncogenes (HER2) and epigenetic modifications at the aromatase promoters to play a role in induction of aromatase. Although, it is not completely understood, the molecules that connect physiological / oncogenic signals to the nuclear receptors may play a role in the activation of normally suppressed aromatase promoter in the tumor cells. Recent evidence suggests that nuclear receptor coregulators have potential to function as major regulators of hormone receptor physiology because of their ability to sense physiological signals and due to their ability to convey those signals to the nuclear receptors at the target gene promoters. PELP1 is novel nuclear receptor coregulator whose expression is deregulated in hormonally driven cancers. Our results suggest that PELP1 overexpression or deregulated growth factor signaling enhances PELP1 recruitment to the silencer regions of the promoter I.3/II, suggesting PELP1 could be one of those factors that promote aromatase expression in breast tumor cells leading local E2 synthesis in breast epithelial cells (Fig. 5). PELP1 ability to interact with growth factors, nuclear receptors and epigenetic modifiers, suggest that deregulation of PELP1 could enhance tumor growth by promoting autocrine ER signaling loop. Future studies using larger number of tumor samples are warranted to examine whether PELP1 could serve as prognostic marker / diagnostic marker for predicting local E2 synthesis. Discovering novel pathways that contribute to local E2 synthesis in breast tumors will enable to develop new therapeutic agents that block these pathways with fewer side effects.

Fig. 5.

Schematic representation of potential PELP1 autocrine signaling loop in cancer cells. Growth factor signaling and / or activation of non-genomic signaling pathways promotes ER coactivator PELP1 to form a complex with ERRα and PNRC2, leading to activation of aromatase expression promoting formation of a positive feedback loop locally synthesizing E2, results in the activation of E2-ER-PELP1 signaling in breast cancer cells.

Acknowledgments

Support for this research was provided by grants CA0095681 (R.K.V), W81XWH-08-1-0604 (R.K.V), CA75018 (R.R.T) and CTRC pilot grant P30CA54174.

Footnotes

Presented at Ninth International Aromatase Conference: IAC 2008 (Shanghai, China, 13-16 October 2008)

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Reference List

- 1.Moy B, Goss PE. Estrogen receptor pathway: resistance to endocrine therapy and new therapeutic approaches. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:4790–4793. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-1535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Losel R, Wehling M. Nongenomic actions of steroid hormones. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2003;4:46–56. doi: 10.1038/nrm1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bjornstrom L, Sjoberg M. Mechanisms of estrogen receptor signaling: convergence of genomic and nongenomic actions on target genes. Mol Endocrinol. 2005;19:833–842. doi: 10.1210/me.2004-0486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lonard DM, O'Malley BW. The expanding cosmos of nuclear receptor coactivators. Cell. 2006;125:411–414. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Collingwood TN, Urnov FD, Wolffe AP. Nuclear receptors: coactivators, corepressors and chromatin remodeling in the control of transcription. J Mol Endocrinol. 1999;23:255–275. doi: 10.1677/jme.0.0230255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McKenna NJ, Lanz RB, O'Malley BW. Nuclear receptor coregulators: cellular and molecular biology. Endocr Rev. 1999;20:321–344. doi: 10.1210/edrv.20.3.0366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rosenfeld MG, Lunyak VV, Glass CK. Sensors and signals: a coactivator/corepressor/epigenetic code for integrating signal-dependent programs of transcriptional response. Genes Dev. 2006;20:1405–1428. doi: 10.1101/gad.1424806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.O'Malley BW. Molecular biology. Little molecules with big goals. Science. 2006;313:1749–1750. doi: 10.1126/science.1132509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.O'Malley BW. Coregulators: from whence came these “master genes”. Mol Endocrinol. 2007;21:1009–13. doi: 10.1210/me.2007-0012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lonard DM, Lanz RB, O'Malley BW. Nuclear receptor coregulators and human disease. Endocr Rev. 2007;28:575–587. doi: 10.1210/er.2007-0012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Simpson ER, Mahendroo MS, Means GD, Kilgore MW, Hinshelwood MM, Graham-Lorence S, Amarneh B, Ito Y, Fisher CR, Michael MD. Aromatase cytochrome P450, the enzyme responsible for estrogen biosynthesis. Endocr Rev. 1994;15:342–355. doi: 10.1210/edrv-15-3-342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lu Q, Nakmura J, Savinov A, Yue W, Weisz J, Dabbs DJ, Wolz G, Brodie A. Expression of aromatase protein and messenger ribonucleic acid in tumor epithelial cells and evidence of functional significance of locally produced estrogen in human breast cancers. Endocrinology. 1996;137:3061–3068. doi: 10.1210/endo.137.7.8770932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.James VH, McNeill JM, Lai LC, Newton CJ, Ghilchik MW, Reed MJ. Aromatase activity in normal breast and breast tumor tissues: in vivo and in vitro studies. Steroids. 1987;50:269–279. doi: 10.1016/0039-128x(83)90077-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bulun SE, Sebastian S, Takayama K, Suzuki T, Sasano H, Shozu M. The human CYP19 (aromatase P450) gene: update on physiologic roles and genomic organization of promoters. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2003;86:219–224. doi: 10.1016/s0960-0760(03)00359-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Utsumi T, Harada N, Maruta M, Takagi Y. Presence of alternatively spliced transcripts of aromatase gene in human breast cancer. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1996;81:2344–2349. doi: 10.1210/jcem.81.6.8964875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhou C, Zhou D, Esteban J, Murai J, Siiteri PK, Wilczynski S, Chen S. Aromatase gene expression and its exon I usage in human breast tumors. Detection of aromatase messenger RNA by reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 1996;59:163–171. doi: 10.1016/s0960-0760(96)00100-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bulun SE, Chen D, Lu M, Zhao H, Cheng Y, Demura M, Yilmaz B, Martin R, Utsunomiya H, Thung S, Su E, Marsh E, Hakim A, Yin P, Ishikawa H, Amin S, Imir G, Gurates B, Attar E, Reierstad S, Innes J, Lin Z. Aromatase excess in cancers of breast, endometrium and ovary. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2007;106:81–96. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2007.05.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kaklamani VG, Gradishar WJ. Adjuvant therapy of breast cancer. Cancer Invest. 2005;23:548–560. doi: 10.1080/07357900500202937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gururaj AE, Rayala SK, Vadlamudi RK, Kumar R. Novel mechanisms of resistance to endocrine therapy: genomic and nongenomic considerations. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:1001s–1007s. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-2110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schiff R, Massarweh SA, Shou J, Bharwani L, Arpino G, Rimawi M, Osborne CK. Advanced concepts in estrogen receptor biology and breast cancer endocrine resistance: implicated role of growth factor signaling and estrogen receptor coregulators. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2005;56 1:10–20. doi: 10.1007/s00280-005-0108-2. 10-20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shin I, Miller T, Arteaga CL. ErbB receptor signaling and therapeutic resistance to aromatase inhibitors. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:1008s–1012s. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-2352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Subbaramaiah K, Howe LR, Port ER, Brogi E, Fishman J, Liu CH, Hla T, Hudis C, Dannenberg AJ. HER-2/neu status is a determinant of mammary aromatase activity in vivo: evidence for a cyclooxygenase-2-dependent mechanism. Cancer Res. 2006;66:5504–5511. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-4076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sabnis G, Goloubeva O, Jelovac D, Schayowitz A, Brodie A. Inhibition of the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt pathway improves response of long-term estrogen-deprived breast cancer xenografts to antiestrogens. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:2751–2757. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-2466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vadlamudi RK, Wang RA, Mazumdar A, Kim Y, Shin J, Sahin A, Kumar R. Molecular cloning and characterization of PELP1, a novel human coregulator of estrogen receptor alpha. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:38272–38279. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M103783200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wong CW, McNally C, Nickbarg E, Komm BS, Cheskis BJ. Estrogen receptor-interacting protein that modulates its nongenomic activity-crosstalk with Src/Erk phosphorylation cascade. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:14783–14788. doi: 10.1073/pnas.192569699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 26.Choi YB, Ko JK, Shin J. The transcriptional corepressor, PELP1, recruits HDAC2 and masks histones using two separate domains. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:50930–50941. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M406831200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nair SS, Mishra SK, Yang Z, Balasenthil S, Kumar R, Vadlamudi RK. Potential role of a novel transcriptional coactivator PELP1 in histone H1 displacement in cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2004;64:6416–6423. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vadlamudi RK, Kumar R. Functional and biological properties of the nuclear receptor coregulator PELP1/MNAR. Nucl Recept Signal. 2007;5:e004. doi: 10.1621/nrs.05004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rosendorff A, Sakakibara S, Lu S, Kieff E, Xuan Y, DiBacco A, Shi Y, Shi Y, Gill G. NXP-2 association with SUMO-2 depends on lysines required for transcriptional repression. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:5308–5313. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601066103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vadlamudi RK, Manavathi B, Balasenthil S, Nair SS, Yang Z, Sahin AA, Kumar R. Functional implications of altered subcellular localization of PELP1 in breast cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2005;65:7724–7732. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-0614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Greger JG, Fursov N, Cooch N, McLarney S, Freedman LP, Edwards DP, Cheskis BJ. Phosphorylation of MNAR promotes estrogen activation of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27:1904–1913. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01732-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 32.Balasenthil S, Vadlamudi RK. Functional interactions between the estrogen receptor coactivator PELP1/MNAR and retinoblastoma protein. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:22119–22127. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M212822200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vadlamudi RK, Bagheri-Yarmand R, Yang Z, Balasenthil S, Nguyen D, Sahin AA, den HP, Kumar R. Dynein light chain 1, a p21-activated kinase 1-interacting substrate, promotes cancerous phenotypes. Cancer Cell. 2004;5:575–585. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2004.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vadlamudi RK, Balasenthil S, Broaddus RR, Gustafsson JA, Kumar R. Deregulation of estrogen receptor coactivator proline-, glutamic acid-, and leucine-rich protein-1/modulator of nongenomic activity of estrogen receptor in human endometrial tumors. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89:6130–6138. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-0909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dimple C, Nair SS, Rajhans R, Pitcheswara PR, Liu J, Balasenthil S, Le XF, Burow ME, Auersperg N, Tekmal RR, Broaddus RR, Vadlamudi RK. Role of PELP1/MNAR signaling in ovarian tumorigenesis. Cancer Res. 2008;68:4902–4909. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-5698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rajhans R, Nair S, Holden AH, Kumar R, Tekmal RR, Vadlamudi RK. Oncogenic Potential of the Nuclear Receptor Coregulator Proline-, Glutamic Acid-, Leucine-Rich Protein 1/Modulator of the Nongenomic Actions of the Estrogen Receptor. Cancer Res. 2007;67:5505–5512. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-3647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Marcom PK, Isaacs C, Harris L, Wong ZW, Kommarreddy A, Novielli N, Mann G, Tao Y, Ellis MJ. The combination of letrozole and trastuzumab as first or second-line biological therapy produces durable responses in a subset of HER2 positive and ER positive advanced breast cancers. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2007;102:43–49. doi: 10.1007/s10549-006-9307-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shou J, Massarweh S, Osborne CK, Wakeling AE, Ali S, Weiss H, Schiff R. Mechanisms of tamoxifen resistance: increased estrogen receptor-HER2/neu cross-talk in ER/HER2-positive breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2004;96:926–935. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djh166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Manavathi B, Nair SS, Wang RA, Kumar R, Vadlamudi RK. Proline-, glutamic acid-, and leucine-rich protein-1 is essential in growth factor regulation of signal transducers and activators of transcription 3 activation. Cancer Res. 2005;65:5571–5577. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-4664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rajhans R, Nair HB, Nair SS, Cortez V, Ikuko K, Kirma NB, Zhou D, Holden AE, Brann DW, Chen S, Tekmal RR, Vadlamudi RK. Modulation of in situ Estrogen Synthesis by PELP1: Potential ER Autocrine Signaling Loop in Breast Cancer Cells. Mol Endocrinol. 2008;22:649–64. doi: 10.1210/me.2007-0350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kitawaki J, Noguchi T, Amatsu T, Maeda K, Tsukamoto K, Yamamoto T, Fushiki S, Osawa Y, Honjo H. Expression of aromatase cytochrome P450 protein and messenger ribonucleic acid in human endometriotic and adenomyotic tissues but not in normal endometrium. Biol Reprod. 1997;57:514–519. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod57.3.514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Matsuzaki S, Canis M, Pouly JL, Dechelotte PJ, Mage G. Analysis of aromatase and 17beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 2 messenger ribonucleic acid expression in deep endometriosis and eutopic endometrium using laser capture microdissection. Fertil Steril. 2006;85:308–313. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2005.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Utsunomiya H, Cheng YH, Lin Z, Reierstad S, Yin P, Attar E, Xue Q, Imir G, Thung S, Trukhacheva E, Suzuki T, Sasano H, Kim JJ, Yaegashi N, Bulun SE. Upstream stimulatory factor-2 regulates steroidogenic factor-1 expression in endometriosis. Mol Endocrinol. 2008;22:904–914. doi: 10.1210/me.2006-0302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zeitoun K, Takayama K, Michael MD, Bulun SE. Stimulation of aromatase P450 promoter (II) activity in endometriosis and its inhibition in endometrium are regulated by competitive binding of steroidogenic factor-1 and chicken ovalbumin upstream promoter transcription factor to the same cis-acting element. Mol Endocrinol. 1999;13:239–253. doi: 10.1210/mend.13.2.0229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yang C, Yu B, Zhou D, Chen S. Regulation of aromatase promoter activity in human breast tissue by nuclear receptors. Oncogene. 2002;21:2854–2863. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chen S, Itoh T, Wu K, Zhou D, Yang C. Transcriptional regulation of aromatase expression in human breast tissue. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2002;83:93–99. doi: 10.1016/s0960-0760(02)00276-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kouzarides T. Chromatin modifications and their function. Cell. 2007;128:693–705. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Garcia-Bassets I, Kwon YS, Telese F, Prefontaine GG, Hutt KR, Cheng CS, Ju BG, Ohgi KA, Wang J, Escoubet-Lozach L, Rose DW, Glass CK, Fu XD, Rosenfeld MG. Histone methylation-dependent mechanisms impose ligand dependency for gene activation by nuclear receptors. Cell. 2007;128:505–518. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.12.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nair SS, Nair BC, Chakravarty D, Tekmal RR, Vadlamudi RK. Regulation of histone H3 methylation by ER coregulator PELP1: A novel paradigm in coregulator function. Proceedings of AACR Meeting. 2009 Abstract #09-AB-3856-AACR. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lan F, Nottke AC, Shi Y. Mechanisms involved in the regulation of histone lysine demethylases. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2008;20:316–325. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2008.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]