Abstract

This paper reports on the development and psychometric properties of the Antiretroviral General Adherence Scale (AGAS) in 2 NIH-funded projects: the Get Busy Living Project, a behavioral clinical trial to promote consistent use of antiretroviral therapy (ART); and the KHARMA Project, which addressed issues of adherence and risk reduction behavior in women. AGAS assesses the ease and ability of participants to take ART according to a health care provider's recommendations. Data were analyzed from completed baseline assessments of the 2 studies. The AGAS was internally consistent in both samples. Content, construct, and criterion validity were established using factor analysis and correlations of total AGAS scores with 2 measures of adherence: electronic drug monitoring (EDM) and an Adult AIDS Clinical Trials Group (AACTG) adherence scale. Viral load, CD4 cell counts, and depression scores were also examined. Reliability and validity of the AGAS were supported in both samples.

Keywords: adherence, antiretroviral medications, reliability, psychometrics, validity

An Examination of the Psychometric Properties of the Antiretroviral General Adherence Scale (AGAS) in Two Samples of HIV-Infected Individuals

Non-adherence to antiretroviral therapy (ART) can undermine the therapeutic effect of the medications and contribute to the occurrence of viral mutation and drug resistance. Strict adherence to the drug regimen is extremely important for patients to prolong life, prevent opportunistic infections, prevent hospitalizations (Paterson et al., 2000), and protect themselves and their partners from drug resistant strains of HIV.

There is no universally accepted definition of medication adherence because it is a multifaceted concept. Essentially, adherence is “the extent to which patients follow the instructions they were given for prescribed treatments” (Haynes, Ackloo, Sahota, McDonald, Yao, 2008, p. 2). For ART, adherence might involve obtaining the medications; taking the correct number of pills and the correct number of doses at the correct times; and following any dietary, storage, or other medication-related instructions. The patient is expected to do what is needed to meet the regimen requirements. Patients who follow the instructions exactly are considered to be 100% adherent.

Often medication adherence is measured by the number of doses taken and/or the number of doses taken as scheduled. Depending on the durability of the antiretroviral (ARV) medications in a regimen, patients may need to adhere to as many as 95% of the recommended doses (Paterson et al., 2000). Because higher levels of adherence are associated with increased quality of life and decreased spread of the infection, valid, reliable, and easy to administer measures must be available to determine adherence. The purpose of this study is to describe and examine the psychometric properties of the Antiretroviral General Adherence Scale (AGAS), a practical and easy to administer, 5-item, self-report measure of ARV medication adherence over a 30-day period. A comprehensive examination of scale reliability and validity is presented.

There are various ways to measure medication adherence such as self-reports, pill counts, biological assays, electronic drug monitoring (EDM), pharmacy logs, and scaled questionnaires (Simoni et al., 2006). The easiest, fastest, most practical, and most economical way to measure adherence is to ask the patient. It is generally accepted and recently validated that when a patient admits to poor adherence, the report is valid; however, reports of good or perfect adherence may be overestimates due to bias associated with recall or social desirability (Pearson, Simoni, Hoff, Kurth, & Martin, 2007). Thus, the challenge is to find a measure that transcends those issues, is easy to administer, and gives results that are comparable to more expensive and time intensive objective measures (Simoni et al., 2006).

Development of the AGAS

The AGAS had its origins in the General Adherence Scale (GAS). The GAS was developed for and used in the Medical Outcomes Study (MOS), which was a widely known and well-respected 2-year, large-scale study of adherence in persons with chronic conditions such as diabetes, hypertension, and heart disease. The GAS assessed a patient's general tendency to adhere to medical advice in the previous 4-week period (Sherbourne, Hays, Ordway, DiMatteo, & Kravitz, 1992). It provides an overview of the ease or difficulty a participant has in following the provider's recommendations. To facilitate comparison with other scales, the GAS raw score can be changed to a proportion (0%-100%) by dividing the achieved score by the maximum possible score. The GAS was tested extensively as part of the MOS. The internal consistency was acceptable (alpha coefficient = .81). Test-retest reliability for 2 years was .40, which could be consistent with a construct, such as adherence, that changes over time. Factor analysis supported unidimensionality of the 5 items (Sherbourne et al., 1992). The GAS also had very low correlations with a social desirability response set (r = .15), indicating that responses were not significantly affected by social desirability (Hays, 2005).

The GAS was modified (with permission) for the Tuberculosis General Adherence Scale (TBGAS). The TBGAS was used to measure self-reported general tendency to adhere to anti-tuberculosis medications. The TBGAS has demonstrated adequate reliability with Cronbach's alpha of .68 (McDonnell, Turner, & Weaver, 2001).

The TBGAS was then modified for ARV medication adherence. The resultant AGAS (Holstad, Pace, De, & Ura, 2006) is a 5-item scale that focuses on the person's ease and ability to take ART as recommended by a health care provider in the previous 30 days. Items reflect the participant's perception of how difficult or easy it was to take all ARV medications as prescribed, whether the individual was able to do what it took to take the medications as prescribed, and how often the participant took the medications as prescribed over the previous 30 days. Responses are reported on a 6-point Likert scale with responses ranging from 1 (none of the time) to 6 (all of the time). Four items focus on the perceived ability to take ART as the health care provider recommended, and a final item asks participants to rate how often, in general, they were able to take the medications as recommended in the previous 30 days. The AGAS is scored by reverse coding item 1 and then summing all item scores. Total scores range from 5-30, with higher scores indicating higher levels of adherence. Raw scores can be described as a proportion by dividing the score by the total possible (as noted above), for example, a raw score of 28 would translate into 93% adherence. The proportion score can be used to assess the overall level of adherence in the 30-day time period and to compare scores with those on other measures, such as pill counts or electronic drug monitoring.

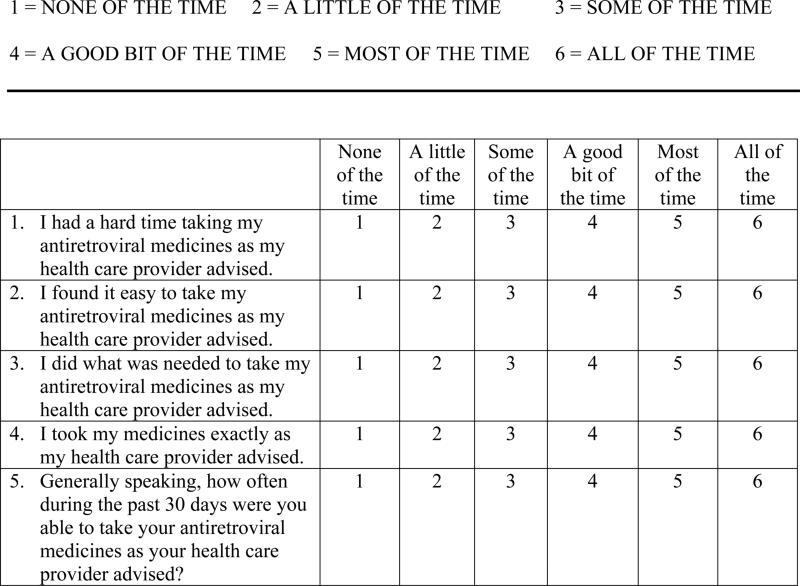

Cronbach's alpha for the initial version was .74 (Holstad, Pace et al., 2006). Item Response Theory (IRT) was used to determine whether the items on the initial version were appropriate for measuring the latent construct of adherence (theta; Baker, 2001; Harvey & Hammer, 1999). Responses to each of the 5 items were modeled for difficulty (the point at which a person has a 50% chance of a positive response to the item) and discrimination (the ability to discriminate between persons with high and low levels of adherence). Data from the study by Holstad, Pace and colleagues (2006) were analyzed using IRT. Based on the results of that analysis, item #3 was noted to be a weak discriminator of adherence. This item was negatively worded and may have been difficult to understand. It was reworded to enhance understanding. This revised version of AGAS was used in the current study and is displayed in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The Antiretroviral General Adherence Scale (AGAS).

Directions: The following statements describe how people feel and what they do, in general, about taking their antiretroviral medicines. Please answer the following statements by saying the number that best describes your feelings and actions in the past 30 days.

Methods

Sample

Data from the baseline assessments of two separate, National Institutes of Health (NIH)-funded studies were used for this project. Both studies focused on promoting ART adherence. Participants for both studies were recruited from HIV treatment sites in a large Southeastern city. Both studies were approved by the institutional review board at Emory University and, when required, the research committees at the recruitment sites. The Get Busy Living Project (GBL) took place from 2000-2004. The purpose of the study was to test the efficacy of an individual-focused nursing intervention using motivational interviewing to promote adherence to ART (DiIorio et al., 2008). The GBL study included 247 participants who were randomly assigned to intervention and control groups. Most participants were male, African American, and single, with a mean age of 41 years. Most of the participants were unemployed, and 80% reported making less than $10,000/year. The number of years living with HIV ranged from less than 1 to 21 years with 37% (n = 90) being HIV-infected for more than 10 years (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics of Participants in GBL and KHARMA

| Variable | GBL n (%) | KHARMA n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 163 (66) | 0 |

| Female | 80 (32.4) | 207 (100) |

| Transgender | 4 (1.6) | |

| Ethnicity | ||

| African American | 216 (87.4) | 193 (93.2) |

| Latino | 4 (1.6) | 3 (1.4) |

| White | 19 (7.7) | 7 (3.4) |

| Other | 8 (3.2) | 4 (1.9) |

| Age | ||

| < 50 | 216 (87.4) | 159 (76.7) |

| 50-60 | 28 (11.2) | 41 (19.7) |

| > 60 | 3 (1.2) | 7 (3.5) |

| Education (years) | ||

| < 12 | 32 (12.9) | 40 (19.3) |

| 12 | 127 (51.4) | 112 (54.1) |

| 13-16 | 73 (29.6) | 45 (21.7) |

| > 16 | 15 (6.1) | 10 (4.8) |

| Employment status | ||

| Employed | 46 (18.8) | 32(15.5) |

| Unemployed | 199 (81.2) | 175(84.5) |

| Marital status | ||

| Married | 17 (6.9) | 19 (9.2) |

| Unmarried | 198 (80.1) | 151 (72.9) |

| Committed relationship | 32 (13) | 36 (17.4) |

| HIV status (years) | ||

| < 1 | 15 (6.2) | 6 (2.9) |

| 1-4 years | 61 (25.1) | 38 (18.4) |

| 5-10 | 77 (31.7) | 66 (31.9) |

| > 10 | 90 (37) | 97 (46.9) |

| Income (annual) | ||

| < $1,000 | 22 (9.7) | 20 (9.7) |

| $1,000-$5,000 | 28 (12.4) | 28 (13.5) |

| $5,001-$10,000 | 118 (52.2) | 88 (42.5) |

| > $10,000 | 58 (25.7) | 65 (31.4) |

Note. GBL = Get Busy Living; KHARMA = Keeping Healthy and Active with Risk Reduction and Medication Adherence.

The Keeping Healthy and Active with Risk Reduction and Medication Adherence (KHARMA) Project tested a group motivational intervention to promote adherence to ART and risk reduction behavior for HIV-infected women (Holstad, DiIorio, & Magowe, 2006). The intervention was led by nurses and based on motivational interviewing. It took place between 2003 and 2008. The study consisted of 207 HIV-infected women who were assigned to either a motivational group intervention or a health promotion control group. All participants were female, most were African American, unmarried, and had a mean age of 43 years. About 66% of this group reported an annual income of $10,000 or less (see Table 1).

Procedures

The AGAS was administered along with a battery of questionnaires to measure adherence, adherence self-efficacy, outcome expectancy, depression, and demographics via audio computer assisted interviewing (ACASI). Instructions for the adherence questions included a description of what was meant by ARV medications versus medications prescribed for other reasons such as prophylaxis of opportunistic infections.

Reliability and Validity

For the purpose of this study, internal consistency was estimated by calculation of Cronbach's alpha. The alpha coefficient is the preferred index of internal consistency reliability because it (a) has a single value for any given set of data, and (b) is equal in value to the mean of the distribution of all possible split-half coefficients associated with a particular set of data (Waltz, Strickland, & Lenz, 2005). According to Nunnally and Bernstein (1994), a Cronbach's alpha for a new scale should be no less than .70 to be considered reliable.

Because the AGAS was adapted from an existing and well-tested instrument, content validity of AGAS was established a priori. Factor analysis was used to evaluate construct validity of the AGAS. A principal axis factor analysis with oblique rotation was conducted. Principal axis was used because this method determines the least number of factors that can account for the common variance in a set of variables. This was appropriate for determining the dimensionality of a set of variables such as a set of items in a scale. Oblique rotation was used because it allowed the factors to be correlated, and it provided a more meaningful pattern of the item factor loadings.

To evaluate criterion-related validity, AGAS total scores were correlated with adherence scores from EDM and a section from the Adult AIDS Clinical Trials (AACTG) instrument (Chesney et al, 2000). To assess predictive validity, results of the clinical indicators of viral load (log10) and CD4 cell counts were compared to AGAS total scores. An appropriate clinical response to ART adherence is an increase in CD4 cell counts and a decrease in viral load; these laboratory tests are monitored regularly in patients receiving ART.

Depression is prevalent in HIV-infected persons (Ciesla & Roberts, 2001) and has consistently been found to negatively impact ART adherence (DiIorio et al., 2009; Vranceanu et al., 2008). This relationship was also examined. Total scores from the Center for Epidemiological Depression Scale (CES-D) were collected in both studies and compared with AGAS total scores. Pearson's product moment correlation coefficient was used to assess all the above relationships.

Instruments for Criterion Validity

Adult AIDS Clinical Trials Group Adherence Instruments

The section of the AACTG adherence instrument (Chesney et al., 2000) that measured the reasons for missing medications was the only AACTG scale administered at baseline in both projects and used for this analysis. Participants respond to 14 items in terms of how often the reasons applied to themselves using a range of never to often. Higher scores indicated more missed medications (lower adherence).

Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale

The CES-D scale is a well-established, short, self-report scale designed to measure depressive symptomatology in the general population (Radloff, 1977). It consists of 20 items on a 4-point Likert-type scale that ranges from 0 (rarely or none of the time) to 3 (most or all of the time). Scores range from 0-60. The scale is scored by summing items after reverse scoring items 4, 8, 12, and 16. Higher scores indicate a higher number of depressive symptoms. Scores of 16 or higher indicate possible depression. Inter-observer reliability (r = .76, p < .001) and validity (r = .77, p < .001) have been established in a group of stroke patients (Shinar et al., 1986).

Electronic Drug Monitoring (EDM) was conducted using MEMS® 5 (GBL) and MEMS® 6 TrackCaps (Aardex Ltd, Zug, Switzerland). Each participant was issued a cap after the screening visit. Data from the caps were downloaded monthly during both studies. The baseline EDM data were used for this analysis and included data downloaded from the period between when the participant received the cap and completed the baseline assessment. This averaged between 2-3 weeks in both studies. One medication from the regimen was electronically monitored and an algorithm was used to determine which medication would receive a cap. In general, that medication was the primary protease inhibitor (PI) or the non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NNRTI) if a PI was not prescribed. A sticker was placed on the monitored medication bottle, and the participant was instructed to write times on the sticker when the medication was pocketed or if the cap had been opened by mistake. At each download, information on this sticker was reviewed and a MEMS questionnaire was completed. The information collected on the questionnaire included changes in medication regimen, problems with the cap, if someone else had administered the medication, and if the medication had been stopped. If the medication had been stopped, the participant was asked who stopped it, the reason for stopping, and if it had been restarted. If the participant was taken off the medication and brought the cap to the study office, it was stored until the participant restarted medication.

Data regarding percent of prescribed doses taken and percent of prescribed doses taken on schedule for the baseline assessment were used for this analysis. EDM data were adjusted by setting certain days as non-monitored on which the following events occurred: cap malfunction, lost cap, medication stopped by health care provider, someone else administered the medication (e.g., hospital, group home), participant in jail, pocketing pills, excessive openings (a form of malfunction defined as more than twice the dose plus 1), or reported use of pill box.

CD4 cell counts and viral loads are indicators of immune status and viral activity. Both are expected to improve with ART, however the intended effect of ART (to prevent viral replication), is more directly assessed by the viral load. These laboratory results were extracted from participants’ medical records while they were enrolled in each study. Dates that the laboratory tests were drawn were grouped according to proximity with the study assessment periods. Labs drawn as close as possible and prior to or on the day of the baseline assessment were classified as the baseline CD4 cell count and viral load results. The median was about 27 days prior to the baseline for both GBL and KHARMA. These results were used for this analysis.

Results

Reliability

All data were analyzed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS), version 15. Mean AGAS scores from the GBL and KHARMA baselines were 25.9 (SD = 4.2) or 86.3% and 26.2 (SD = 4.69) or 87.3% respectively. These scores indicated that both samples had relatively high levels of adherence. An estimate of internal consistency for the AGAS was high (α = .80) in the GBL sample of HIV-infected participants. Individual item means ranged from 4.9 (SD = 1.01) to 5.4 (SD = 1.48). Inter-item correlations ranged from .25 to .66, which was well below.85, indicating that the items were not redundant. Item to total statistics ranged from .34 to .69. Item #1 was the only item that would improve reliability if deleted, but only slightly (α = .82).

Cronbach's alpha for the KHARMA sample was α = .85 suggesting that the scale was also reliable in this sample. Individual item means ranged from 5.08 (SD = 1.37) to 5.38 (SD = 1.08). Inter-item correlations ranged from .39 to .51, also indicating an absence of redundancy. Item to total statistics ranged from .55 to .79. Again item #1 was the only item that would improve reliability if deleted, but again only slightly (α = .86). An estimate of internal consistency for the AGAS was high in both samples, suggesting that the scale was reliable among these samples.

Validity

To further evaluate the psychometric properties of the AGAS, a principal axis factor analysis with oblique rotation was conducted for both samples. Factor analysis is a statistical procedure used to reduce a set of items to a smaller set of items that demonstrate interrelatedness among the items (DiIorio, 2005). These underlying structures are called factors. The purpose of factor analysis is to determine the dimensionality of a measure. Some measures are unidimensional and represent one construct, where as other measures are multidimensional and represent several related constructs.

To assess if the use of factor analysis is appropriate, several tests are used to assess sampling adequacy. The Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) examines if the correlations between pairs of items are large enough not to be explained by other variables. Values can range from 0 to 1, but values of at least .70 are needed in order to be considered acceptable for factoring. The Bartlett's Test of Sphericity determines whether “a correlation matrix is suitable for factor analysis by testing the hypothesis that the matrix is an identity matrix” (Munro, 2005). If the correlation matrix is an identity matrix, the use of factor analysis is inappropriate. The values of the Bartlett's test must be large and significant. These two tests are basic requirements that must be met before a factor analysis should be conducted, and the results to these tests can be found in the initial output from SPSS for factor analysis.

The anti-image correlation, another measure of sampling adequacy, is also provided by SPSS when conducting factor analysis. This output allows the researcher to visually examine the diagonals on the anti-image correlation to determine the sampling adequacy of each item. Values of .70 suggest that the items have sufficient correlations with the other items of the measure.

When examining the output of the factor analysis for the GBL sample, the KMO was .80, which met the criterion of at least .70. The Bartlett's Test of Sphericity was large and significant (374.8, p < .001), and the determinant was less than 1. This further suggested that these data were adequate for factoring. In reviewing the anti-image correlation, the measure of sampling adequacy ranged from .76 to .87, meeting the acceptable criterion.

All items of the scale correlated highly with the other items except item #1, which had low to moderate correlations with the other items. Communalities were similar; ranging from .56 to .71 with the exception of item 1, I had a hard time taking my HIV medications as the health care provider advised, which had the lowest communality of .24. These results suggested that the factor structure worked well for the items. Using the eigen values greater than one criterion, one factor emerged that explained 57.22% of the variance.

According to Nunnally and Bernstein (1994), a cutoff of .30 is an arbitrary guide to defining a discriminating item, and it is more likely that the item is excessively difficult or easy, ambiguous, or has little to do with the domain. Since only one factor emerged, the solution could not be rotated, but factor loadings ranged from .37-.82 with item #1 having the lowest. The fact that one factor emerged suggested that the scale was one-dimensional and that the items were measuring one construct, adherence. The instrument had construct validity for the GBL sample.

Factor analysis was also conducted in the second sample of HIV-infected women (KHARMA). The KMO was .80 and the Bartlett of Sphericity was significant and large (366.4, p < .001), and the determinant was less than 1, indicating that the data were adequate for factoring. In reviewing the anti-image correlations, the measure of sampling adequacy ranged from .39 to .79, meeting the acceptable criterion. All items of the scale were moderately to highly correlated with the other items. Communalities ranged from .69 to .89, suggesting that the factor structure worked well for these items. One factor emerged that explained 64.87% of the variance. The scale also had construct validity in this sample of HIV-infected women.

To demonstrate criterion-related validity, the AGAS total score was correlated with several of the measures and clinical indicators of adherence used in the GBL and KHARMA projects (see Table 2). Total depression scores were also examined for negative correlations, since depression is a consistent indicator of non-adherence in the literature. The other measures were MEMS® percentage of prescribed doses taken and percentage taken on schedule, and the AACTG reasons for missing medications adherence scale. Clinical indicators included viral load and CD4 cell counts since these too have a known relationship with adherence.

Table 2.

Relationship of AGAS to Adherence and Clinical Measures from GBL and KHARMA

| MEMS (% of prescribed doses taken) | MEMS (% of prescribed doses taken on schedule) | AACTG Reasons for Missing medications Scale | CESD | Viral Load Log | CD4 cell Count | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GBL | 29** (n = 210) | −.50** (n = 218) | −.26** (n = 218) | −.16+ (n = 149) | .18* (n = 136) | |

| KHARMA | .24** (n = 200) | .30** (n = 200) | −.59** (n = 206) | −.19** (n = 206) | −.30** (n = 169) | .18* (n = 145) |

Note. MEMS = Medication Event Monitoring System Cap; AACTG = Adults AIDS Clinical Trials Group Adherence Instruments; CESD = Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale.

Pearson correlation coefficients

p < .05

p < .01

p < .1

In GBL and KHARMA, higher AGAS scores (better adherence) were significantly correlated with better adherence on the AACTG (lower scores; p < .01). Although the correlations were low, AGAS scores were also significantly correlated with the objective EDM measures (p < .01) and lower viral load levels in KHARMA data (p < .01).

With respect to depression scores, AGAS was negatively correlated with depressive symptoms (p < .01) such that better adherence was associated with fewer depressive symptoms. Men (M = 13.8, SD = 10.2) and women (M = 14.8, SD = 10.4) did not differ significantly in depressive symptoms in GBL. However, mean depression scores for the women in KHARMA were 16.3 (SD = 11.6), which is the cutoff point for possible clinical depression.

Discussion

The most common way to measure adherence is by self-report. In fact, 66% of the studies measuring patient adherence to HIV regimens have used a self-report method, including surveys, interviews, and diaries (Fogarty et al., 2002). Self-report is commonly used in both research and clinical care because of its low cost, ease of administration, and good correlation with other indirect adherence measures such as EDM and pill count; it is likely that these factors will continue to make it the preferred adherence assessment method in many settings (Simoni et al., 2006). In contrast, some studies have shown that self-report tends to overestimate adherence (Arnsten et al., 2001; Liu et al., 2001). We note the average self-reported adherence rate on AGAS to be 87% in the total sample, which is good, but below the often-recommended 95% rate. Arnsten et al. (2001) compared self-report to EDM (using MEMS® caps) at 1 day and at 1 week in drug users and found significant relationships between the two (r = .49 and .46 respectively, p < .001). They also found that both self-report (r = .43 and .46) and EDM (r = .52 and .55) were significantly associated with mean viral load (p < .001). Despite the fact that EDM and self-report measure different aspects of adherence, we found a low, but significant, relationship of self-report (AGAS) with EDM over a longer period (30 days).

In a comprehensive review of self-report measures of ART adherence, Simoni and colleagues (2006) identified several of the most common self-report measures used during the review period from January 1996 through August 2004. In the 77 published studies they reviewed, the most common method was a single item asking about the number of missed doses over a particular period of time (22 studies). This perspective is reflected in the final AGAS item that asks, generally speaking, how often in the past 30 days were you able to take your antiretroviral medicines as your health care provider advised?

The AACTG instruments have been some of the most widely used published instruments to measure adherence to ART medications. Although they have established validity (Chesney et al., 2000), the instruments have some limitations. The instruments are lengthy and actually consist of seven parts that take more than 20 minutes to complete. The first part consists of questions about the last time medications were missed. There is a general question to this effect and several sections that require the patient to know his/her medication names and dosages and record these as well as the number of doses missed in the previous 4 days, 3 days, 2 days, and yesterday. The second section includes 5 questions about following the medication schedule, special instructions, missing doses on the weekend, and the last time any medication was missed. The last part is a list of 14 reasons for non-adherence to medications. The instruments may require assistance from a trained interviewer to complete. The AGAS was moderately correlated (r = .5 and .6) with the reasons for missing medications section; this probably reflects the ease or difficulty one has in taking ARVs, which the AGAS is designed to measure.

The period of time for self-report measures also varied among the studies Simoni and colleagues (2006) reviewed. Recall periods varied from 48 hours to 1 year; however, the majority used a 3-, 4-, 7-, or 30-day period. Though the optimal period has not yet been determined, 30 days seems to correlate better with the clinical indicator of viral load (Simoni et al., 2006) and with electronic drug monitoring (Lu et al., 2008; Walsh, Mandalia, & Gazzard, 2002) when participants typically have monthly cap data downloads. The AGAS, which measures a 30-day time period, showed significant correlations with both of these indicators.

In most adherence studies, self-report measures are used to primarily capture the amount of medication taken or missed during a specified period of time. Other factors may be associated with the construct of adherence, such as reasons for not taking medications; desire or decision to adhere or not; system factors such as cost, transportation for pharmacy pick up, availability of medications; and the ability to adhere. The AGAS items focus on the participant's perceived difficulty, ease, and ability to take ART as the health care provider recommended, thus incorporating the influence of the above factors, something that is missing from other commonly used measures.

EDM is a frequently used objective measure of adherence in research studies. A computer chip concealed in the cap counts the number of times the bottle is opened. Downloading the information from the computer chip produces a record of dates and times that the bottle was opened. EDM data have been found to be highly related to viral load (Pearson et al., 2007), the desired clinical outcome of ART adherence, but EDM is not without limitations. Besides being very costly to the researcher, pill bottles with monitoring caps are bulky to carry and subject to malfunction. Data do not take into account that medication could have been removed from the bottle but not ingested. It also does not account for extra doses participants might remove and pocket if they plan to be away for their next scheduled doses. If participants routinely use pillboxes to organize their medications, using EDM is difficult. EDM has been found to underestimate adherence (Bova et al., 2005; Pearson et al., 2007). Therefore, the self-report AGAS provides a cost-effective, reliable and valid, easy-to-administer, and clinically-relevant instrument for adherence to medications.

Conclusions

The purpose of this study was to assess the psychometric properties of the AGAS in two research populations. The AGAS is a unidimensional measure that assesses the ease and ability of participants to take ART according to a health care provider's recommendations in the previous 30 days. The AGAS had satisfactory internal consistency in both samples and study findings provided support for content, construct, and criterion validity. In both samples, the AGAS was significantly related to accepted and widely used measures such as the AACTG reasons for missing medications, and EDM measures of the percentage of prescribed doses taken and percentage of doses taken on schedule. AGAS scores were significantly and negatively correlated with depressive symptoms, which is consistent with previous literature. Desired clinical outcome of lower viral loads and higher CD4 cell counts were also significantly associated with AGAS scores. Although the magnitude of many of the correlations was low, this was consistent with many other studies of self-report and physiological measures (Field et al., 1998; Hubbard et al., 2004; Resnicow et al., 2003). Physiological measures represent a biological concept, whereas self-report represents a psychosocial concept of the same construct, adherence.

The results of these analyses provided evidence for both reliability and validity of the AGAS when used for research purposes. The AGAS is easy to read and easy to administer, taking less than 5 minutes to complete, which makes it potentially beneficial for clinical purposes as well. Since most of the participants in these studies were African Americans, and most were of lower socioeconomic status, additional research is needed to support the external validity of the scale in other populations. Until tested with other groups, a potential drawback could be misinterpretation of the meaning of the items by persons of different cultures or ethnicities. Also, additional studies are needed to evaluate use of AGAS in prospective studies that collect adherence data at various time points.

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by two grants from the National Institute of Nursing Research: The KHARMA Project, R01 NR008094, and the Get Busy Living Project, R01 NR04857.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Marcia McDonnell Holstad, Nell Hodgson Woodruff School of Nursing, Emory University Atlanta, GA.

Victoria Foster, Georgia State University Atlanta, GA.

Colleen DiIorio, Department of Behavioral Sciences and Health Education, Rollins School of Public Health, Emory University Atlanta, GA.

Frances McCarty, Department of Behavioral Sciences and Health Education, Rollins School of Public Health, Emory University Atlanta, GA.

Ilya Teplinskiy, Nell Hodgson Woodruff School of Nursing, Emory University Atlanta, GA.

References

- Arnsten JH, Demas PA, Farzadegan H, Grant RW, Gourevitch MN, Chang C, et al. Antiretroviral therapy adherence and viral suppression in HIV-infected drug users: Comparison of self-report and electronic monitoring. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2001;33:1417–1423. doi: 10.1086/323201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker F. The basics of item response theory. University of Maryland; College Park, MD: 2001. [May 26, 2007]. ERIC Clearinghouse on Assessment and Evaluation. from http://echo.edres.org:8080/irt/baker/ [Google Scholar]

- Bova CA, Fennie KP, Knafl GJ, Dieckhaus KD, Watrous E, Williams A. Use of electronic monitoring devices to measure antiretroviral adherence: Practical considerations. AIDS and Behavior. 2005;9(1):103–110. doi: 10.1007/s10461-005-1685-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chesney MA, Ickovicks JR, Chambers DB, Gifford AL, Neidig J, Zwickl B, et al. Self-reported adherence to antiretroviral medications among participants in HIV clinical trials: The AACTG adherence instruments. AIDS Care. 2000;12:255–266. doi: 10.1080/09540120050042891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciesla JA, Roberts JE. Meta-analysis of the relationship between HIV infection and risk for depressive disorders. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 2001;158(5):725–730. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.5.725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiIorio C. Measurement in health behavior. Jossey-Bass; San Francisco: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- DiIorio C, McCarty F, DePadilla L, Resincow K, Holstad MM, Yeager K, et al. Adherence to antiretroviral medication regimens: A test of a psychosocial model. AIDS and Behavior. 2009;13(1):10–22. doi: 10.1007/s10461-007-9318-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiIorio C, McCarty F, Resnicow K, Holstad MM, Soet J, Yeager K, et al. Using motivational interviewing to promote adherence to antiretroviral medications: A randomized controlled study. AIDS Care. 2008;20(3):273–283. doi: 10.1080/09540120701593489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Field AE, Coldita GA, Fox MK, Byers T, Bosch RJ, Peterson KE. Comparisons of 4 questionnaires for assessment of fruit and vegetable intake. American Journal of Public Health. 1998;88(8):1216–1218. doi: 10.2105/ajph.88.8.1216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fogarty L, Roter D, Larson S, Burke J, Gillespie J, Levy R. Patient adherence to HIV medication regimens: A review of published and abstract reports. Patient Education & Counseling. 2002;46:93–108. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(01)00219-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey RJ, Hammer AL. Item response theory. The Counseling Psychologist. 1999;27:353–383. [Google Scholar]

- Haynes RB, Ackloo E, Sahota N, McDonald HP, Yao X. Interventions for enhancing medication adherence. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2008;(Issue 2) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000011.pub3. Art No.:CD000011. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD0000011.pub3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hays RD. The medical outcomes study (MOS) measure of adherence. [May 21, 2007];2005 from http://www.rand.org/health/surveys_tools/mos/mos_adherence.html.

- Holstad MM, DiIorio CD, Magowe MK. Motivating HIV positive women to adhere to antiretroviral therapy and risk reduction behavior: The KHARMA project. Online Journal of Issues in Nursing. 2006;11(1):1–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holstad MM, Pace JC, De AK, Ura DR. Factors associated with adherence to antiretroviral therapy. Journal of the Association of Nurses AIDS Care. 2006;17(2):4–15. doi: 10.1016/j.jana.2006.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubbard JA, Parker EH, Ramsden SR, Flanagan KD, Relyea N, Dearing KF, et al. The relations among observation, physiological, and self-report measures of children's anger. Social Development. 2004;13(1):14–39. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu M, Safren SA, Skolnik PR, Rogers WH, Coady W, Hardy H, et al. Optimal recall period and response task for self-reported HIV medication adherence. AIDS Behavior. 2008;12:86–94. doi: 10.1007/s10461-007-9261-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lui H, Golin CE, Miller LG, Hays RD, Beck CK, Sanandaji S, et al. A comparison study of multiple measures of adherence to HIV protease inhibitors. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2001;134:968–977. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-134-10-200105150-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonnell M, Turner J, Weaver MT. Antecedents of adherence to antituberculosis therapy. Public Health Nursing. 2001;18(6):392–400. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1446.2001.00392.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munro BH. Statistical methods for health care research. 5th ed. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; Philadelphia, PA: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Nunnally JC, Bernstein IH. Psychometric theory. 3rd ed. McGraw-Hill; New York: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Paterson DL, Swindells S, Mohr J, Brester M, Vergis E, Squier C, et al. Adherence to protease inhibitor treatment and outcomes in patients with HIV infection. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2000;133:21–30. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-133-1-200007040-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearson CR, Simoni JM, Hoff P, Kurth AE, Martin DP. Assessing antiretroviral adherence via electronic drug monitoring and self-report: An examination of key methodological issues. AIDS and Behavior. 2007;11:161–173. doi: 10.1007/s10461-006-9133-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Journal of Applied Psychology. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Resnicow K, McCarty F, Blisset D, Wong T, Heitzler C, Lee RE. Validity of a modified CHAMPS physical activity questionnaire among African Americans. Medicine Science in Sports & Medicine. 2003;35:1537–1545. doi: 10.1249/01.MSS.0000084419.64044.2B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherbourne CD, Hays RD, Ordway L, DiMatteo MR, Kravitz RG. Antecedents of adherence to medical recommendations: Results from the medical outcomes study. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 1992;15:447–468. doi: 10.1007/BF00844941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shinar D, Gross CR, Price TR, Banko M, Boldue PL, Robinson RG. Screening for depression in stroke patients: The reliability and validity of the center for epidemiologic studies depression scale. Stroke. 1986;17(2):241–245. doi: 10.1161/01.str.17.2.241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simoni JM, Kurth AE, Pearson CR, Pantalone DW, Merrill JO, Frick PA. Self-report measures of antiretroviral therapy adherence: A review with recommendations for HIV research and clinical management. AIDS Behavior. 2006;10:227–245. doi: 10.1007/s10461-006-9078-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vranceanu AM, Safren SA, Lu M, Coady WM, Skolnik PR, Rogers WH, et al. The relationship of post-traumatic stress disorder and depression to antiretroviral medication adherence in persons with HIV. AIDS Patient Care and STDs. 2008;22(4):313–321. doi: 10.1089/apc.2007.0069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh JC, Mandalia S, Gazzard BG. Responses to a 1 month self-report on adherence to antiretroviral therapy are consistent with electronic data and virological treatment outcome. AIDS. 2002;16(2):269–277. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200201250-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waltz CF, Strickland OL, Lenz ER. Measurement in nursing and health research. 3rd ed. Springer; New York: 2005. [Google Scholar]