Abstract

Background

The aim of the present study is to examine whether the patterns of association between the quality of the parent–adolescent relationship on the one hand, and aggression and delinquency on the other hand, are the same for boys and girls of Dutch and Moroccan origin living in the Netherlands. Since inconsistent results have been found previously, the present study tests the replicability of the model of associations in two different Dutch samples of adolescents.

Method

Study 1 included 288 adolescents (M age = 14.9, range 12–17 years) all attending lower secondary education. Study 2 included 306 adolescents (M age = 13.2, range = 12–15 years) who were part of a larger community sample with oversampling of at risk adolescents.

Results

Multigroup structural analyses showed that neither in Study 1 nor in Study 2 ethnic or gender differences were found in the patterns of associations between support, autonomy, disclosure, and negativity in the parent–adolescent relationship and aggression and delinquency. The patterns were largely similar for both studies. Mainly negative quality of the relationship in both studies was found to be strongly related to both aggression and delinquency.

Discussion

Results show that family processes that affect adolescent development, show a large degree of universality across gender and ethnicity.

Keywords: Ethnicity, Adolescence, Parent–child relationship, Parenting, Externalizing problem behavior

Introduction

A large body of research has examined how parenting and the parent–adolescent relationship are related to externalizing problem behavior in adolescence. Steinberg and Silk [32] have described three parenting domains that reflect important aspects of the parent–adolescent relationship: namely the harmony domain (e.g., support), the autonomy domain (e.g., disclosure, autonomy granting), and the conflict domain (e.g., hostility, conflict). With regard to the harmony domain, previous research has consistently shown that higher levels of (perceived) parental support are—directly or indirectly—related to lower levels of adolescent delinquency, aggression, or other adjustment problems [e.g., 3, 20]. With regard to the autonomy domain, higher levels of behavioral autonomy granting [6] and disclosure (i.e., voluntary disclosure of their activities and whereabouts to their parents) [2, 3, 27, 30] have shown to be associated with lower levels of adolescent adjustment problems, whereas in the conflict domain, negativity in the parent–child relationship (e.g., conflict and hostility) is often found to be a strong predictor of adolescent externalizing problem behavior [7, 19].

Although these studies provide valuable insights regarding the links between the parent–adolescent relationship and adolescent problem behavior, they have been conducted mostly with White, middleclass samples. Considering the fact that nowadays most Western societies are multi-ethnic, it is important to test whether these previous findings are universal across ethnic groups. In the past years, many studies have examined the associations between parenting, the parent–child relationship, and child problem behavior across ethnic minority and majority groups. Two models of the links between parenting and outcomes in different ethnic groups can be distinguished [16]. The cultural values model, proposes that parenting behaviors have different effects in families that differ in ethnicity from the host culture because these families are embedded in alternative value structures [16]. In contrast, the ethnic equivalence model [16] suggests that family influences go past ethnicity, which means that there are no differences in the way parenting is related to adolescent outcomes across ethnic groups.

In some of the studies on ethnic differences in family and parenting processes, the cultural values model has been confirmed. That is, differences between ethnic groups were found in associations between parenting and family relations on the one hand, and externalizing problem behavior on the other hand. For example, Smith and Krohn [26] found that being less involved with parents in activities was significantly related to delinquent behavior for Hispanic adolescents, but not for White and African American adolescents. Parent–child attachment and a greater sense of parental control, on the other hand, were found to be related to delinquency only for White and African American adolescents, and not for Hispanic adolescents. Two studies on the relationship between harsh discipline and externalizing problem behavior, showed that physical discipline was related to higher levels of externalizing behavior for European American adolescents, but to lower levels of externalizing problem behavior for African American adolescents [8, 18].

In many other studies, however, the ethnic equivalence model was confirmed, which means that no ethnic differences were found in the associations between family processes, parenting, and adolescent externalizing problem behavior [9, 10, 13, 23, 36]. For example, Vazsonyi et al. [36] recently found that the associations between family processes, such as closeness, support, monitoring, and parent–adolescent conflict on the one hand and adolescent externalizing behavior on the other hand were not affected by immigrant status of the adolescent.

In the present study, we examine whether the patterns of association between disclosure, negative quality of the parent–adolescent relationship, perceived parental support, autonomy granting by parents, and both aggression and delinquency are the same for adolescents of Moroccan and Dutch origin. From previous studies, we learned that ethnic differences are mainly found in studies that examined aspects of parental discipline in relation with externalizing problem behavior. In studies that assessed parental warmth or support, no ethnic differences were found. It seems that the relationship of parental discipline with externalizing problems is more a culturally influenced process, whereas the relationship between parental warmth or support is more a universal process. Furthermore, previous studies very often included ethnic minority groups that were also lower in SES status than the ethnic majority group. To address the inconsistency of previous findings, we replicated the model in the present study across two samples that differ in sampling method. The first sample is a school sample of adolescents who all attend lower secondary education and can therefore be considered a homogeneous group. In the second sample, at risk adolescents were slightly oversampled. Educational level of these adolescents is more diverse than in the first sample.

We focus on Moroccan versus autochthonous Dutch adolescents for the following reasons. First, Moroccans belong to the largest groups of immigrants in The Netherlands. In 2006, 315,000 individuals of the total Dutch population of 16 million, were of Moroccan origin. The current immigrant population of Moroccans in the Netherlands originated from the large number of (male) immigrant workers that came to the Netherlands in the 1960s and 1970s of the last century to fill in the gap in the lower segments of the labor market [21, 35]. Due to family reunion, the number of Moroccan immigrants grew steadily until the mid-1980s. The majority of young, second-generation Moroccans has attended or is currently attending lower secondary education. The second reason for focusing on Moroccan adolescents is that, compared to the other large ethnic groups in The Netherlands (Turkish, Surinamese, and Antillean) Moroccans tend to live most segregated from other cultural groups. Of all ethnic groups in the Netherlands, Moroccan youths have the highest chance of dropping out of school, and levels of unemployment are highest among Moroccan people compared to other ethnic groups and people of Dutch origin [21]. Two studies on externalizing problem behavior among early adolescents of different origin in the Netherlands showed that teachers report significantly more externalizing problems among Moroccan adolescents than among their peers of Dutch origin [33–35, 37]. A recent report shows that Moroccan youths also more often run into difficulties with the police, and start offending at an earlier age than other adolescents living in the Netherlands [21].

In most studies on parenting, the parent–adolescent relationship and externalizing problem behavior in different ethnic groups, only ethnic differences were examined and gender differences were not taken into account [10, 17]. Although in most general studies on the associations between the quality of family relations and adolescent problem behavior only gender differences were found with regard to the mean levels of problem behavior and family relationship quality, there were also some studies that did find gender differences in associations [2, 22]. In order to check for possible gender and ethnicity interaction, in the present study we examine both ethnic and gender differences in the associations. In earlier studies, mostly a combined measure of externalizing behavior was used. There is, however, enough evidence showing that although aggression and delinquency are related, they also represent quite different types of behavior [2, 4, 28, 29]. In the present study, we therefore examine the associations of family relationship quality with aggression and delinquency separately.

Aims and hypotheses

Since inconsistent results have been found in research in different ethnic groups, we examine the relationship between variables in all three important parenting domains in adolescence (i.e., the harmony domain, the autonomy domain, and the conflict domain), and externalizing problem behavior. Associations between perceived support, disclosure, autonomy granting by parents, and negativity in the parent–adolescent relationship, and both aggression and delinquency in two different samples of adolescents of Moroccan and Dutch origin living in the Netherlands will be examined. The main research question of the present study is whether parenting and quality of the parent–adolescent relationship are related to aggression and delinquency in the same way for Moroccan and Dutch boys and girls.

Based on previous studies that assessed warmth, support, and conflict in relation to externalizing problem in different ethnic groups, we hypothesize that there are no differences in the patterns of association between Moroccan and Dutch boys and girls in both studies. With regard to the specific relationships between the assessed variables, we expect that support, disclosure, and autonomy granting are negatively related to both delinquency and aggression. We expect negative quality of the parent–child relationship to be positively related to both aggression and delinquency.

In the present research, the proposed model is tested in two different samples. We first present the “Methods” and “Results” section for Study 1, then for Study 2. In the “Discussion”, we will compare and discuss the findings of Study 1 and Study 2.

Study 1

Methods

Participants and procedure

The sample of the first study consisted of 288 adolescents all attending lower secondary professional education. Participants were of Dutch (n boys = 57; n girls = 92) and Moroccan origin (n boys = 65; n girls = 74). The mean age for Moroccan adolescents was 14.8 years (SD = 1.03, range 12.6–17 years), and 14.9 years (SD = 0.93, range 12.6–17 years) for adolescents of Dutch origin. There was no ethnic difference in gender and age distribution. Adolescents filled out questionnaires in the school setting.

Schools were selected on the basis of an immigrant population varying from 10 to 45%. Ten schools agreed to participate; these schools were all located in 7 midsized to large cities in the Netherlands. A letter describing the study was sent to the parents, who could indicate that they did not wish their child to participate. Less than 2% of the adolescents did not participate because of parental or adolescent refusal. The sample used in the present study is part of a larger study on ethnic groups in The Netherlands. Data were collected between 2001 and 2004.

Measures

Ethnicity

Adolescent ethnicity was based on the country of birth of both parents and the adolescent. If either the adolescent, or the mother or father, was born in Morocco, the adolescent was considered to be of Moroccan origin. In studies on ethnic minority groups in The Netherlands, this is a common way to determine ethnicity [e.g., 5, 35]. If the adolescent and both parents were born in The Netherlands, the adolescent was considered Dutch.

Negative quality of the parent–adolescent relationship

Negative quality of the parent–adolescent relationship was measured by using the Network of Relationship Inventory [11]. For the present study, two subscales Conflict (e.g., ‘How much do you and your parents disagree and quarrel?’) and Antagonism (e.g., ‘How much do you and your parents get annoyed with each other’s behavior?’) were combined to form the 6-item-scale negative quality of the parent–adolescent relationship. Adolescents were asked to rate how much each statement characterized the relationship with their parents using a standard 5-point Likert scale (1 = almost never/never to 5 = almost always/always). Cronbachs’ alpha was 0.78 and 0.84 for Moroccan and Dutch adolescents, respectively.

Support

The Parental Behavior Questionnaire [38] was used to measure support in the parent–adolescent relationship. The mean of the subscales Warmth (e.g., ‘How often do your parents let you know that they love you?’) and Responsiveness (e.g., ‘How often really try to help, comfort you, or cheer you up when you are having a (small) problem?’) was used to measure Support from parents. The combined scale consisted of 10 items, that were assessed on a 5-point scale (1 = never to 5 = very often). Cronbach’s alpha was 0.87 and 0.85 for Moroccan and Dutch adolescents, respectively.

Autonomy granting

The Parental Behavior Questionnaire [38] was used to measure autonomy granting (e.g., ‘How often do your parents tell you that you can do something on your own?’). The scale consisted of 5 items and was measured on a 5-point scale (1 = never to 5 = very often). Cronbach’s alpha was 0.68 for Moroccan and 0.52 for Dutch adolescents.

Adolescent disclosure

Adolescents were asked to indicate how much they tell their parents about their activities (e.g., ‘How much do you tell your parents about who your friends are?’). The scale consisted of 6 items to be answered on a 4-point scale (1 = nothing to 4 = everything). Cronbach’s alpha was 0.83 and 0.79 for Moroccan and Dutch adolescents, respectively.

Externalizing problem behavior

The Youth Self-Report [1] was used to measure Aggression and Delinquency. The response categories for the YSR were on a 3-point answering scale (0 = not true, 1 = somewhat or sometimes true, and 2 = very true or often true). The Aggressive behavior scale contained 19 items (e.g., ‘I fight often’, ‘I scream and yell often’), Cronbach’s alpha for this scale was 0.90 and 0.80 for Moroccan and Dutch adolescents, respectively. The Delinquent behavior scale consisted of 12 items (i.e., ‘I steal from my home’, ‘I use drugs’). Cronbach’s alpha for these scales were 0.88 and 0.67 for Moroccan and Dutch adolescents, respectively.

Results

To deal with missing values we used Expected Maximization imputation method in SPSS in cases where <10% of the scale items were missing.1

Ethnic and gender differences in patterns of association

The model describing the associations between the parent–adolescent relationship and adolescent aggression and delinquency was tested using structural equation modeling in LISREL 8.54 [15]. Input for these analyses consisted of separate covariance matrices and mean of all the assessed constructs for Moroccan and Dutch boys and girls. Parameters were estimated by the Maximum Likelihood Method.

Since we did not expect differences across ethnic and gender groups, first a fully constrained model was tested (M1: see Table 1). In this model it was hypothesized that associations between the variables were equal for boys and girls of Moroccan and Dutch origin. Therefore, all paths (beta, β) were set equal across the four groups. In the second model, β was held equal across gender groups only (M2: see Table 1). Third, a model was tested, where β was held equal across ethnic groups only (M3: see Table 1). In a fourth model, the fully unconstrained model, all paths (β) were estimated separately for all four groups (M4: see Table 1). All models were compared to the fully constrained model using a standard χ 2-difference test. The fit indices and the results of the comparison between the models can also be found in Table 1.

Table 1.

Multigroup analyses for Moroccan and Dutch adolescents, Study 1 and Study 2

| Model | Study 1 | Study 2 | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| df | χ 2 | RMSEA | NNFI | Δdf | Δχ 2 | df | χ 2 | RMSEA | NNFI | Δdf | Δχ 2 | |

| Gender × Ethnicity | ||||||||||||

| M1: constrained model | 24 | 31.70 | 0.06 | 0.97 | 24 | 31.09 | 0.06 | 0.97 | ||||

| M2: constrained across gender groups | 16 | 22.37 | 0.07 | 0.96 | 16 | 18.07 | 0.04 | 0.99 | ||||

| M3: constrained across ethnic groups | 16 | 17.46 | 0.03 | 0.99 | 16 | 17.96 | 0.04 | 0.99 | ||||

| M4: unconstrained model (fully saturated) | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0 | ||||||||

| M2 versus M1 | 8 | 9.33ns | 8 | 13.02ns | ||||||||

| M3 versus M1 | 8 | 14.24ns | 8 | 13.13ns | ||||||||

| M4 versus M1 | 24 | 31.70ns | 24 | 31.09 | ||||||||

Constrained model: β values were held equal across groups

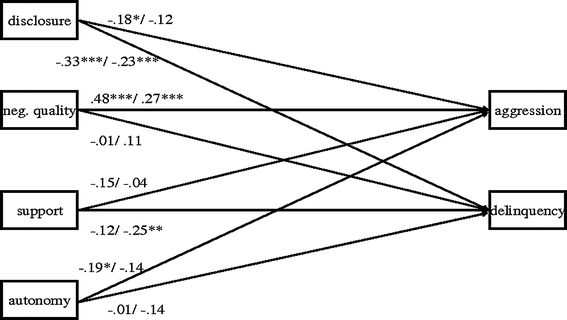

The comparison of the fit indices for the four models revealed that the model constrained for ethnicity only, the model with constraints between gender groups only, and the fully unconstrained model were of no significant improvement compared to the fully constrained model. On the basis of these results, we may conclude that the same model linking parent–adolescent relationship variables and both delinquency and aggression, is applicable to both Moroccan and Dutch girls and boys. Figure 1 shows the final (constrained) model with standardized β between the assessed variables.

Fig. 1.

Pathmodel: Standardized β is shown for Study 1/Study 2. Note * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01, *** P < 0.001

The final model (see Fig. 1) indicated that higher levels of disclosure were significantly related to lower levels of aggression (β = −0.18) and delinquency (β = −0.33). Negative quality of the parent–child relationship (β = 0.48), and autonomy (β = −0.19) were both related to aggression, but not to delinquency. Perceived parental support was related neither to aggression nor to delinquency.

Study 2

Method

Participants and procedure

Participants of Study 2 were 306 boys and girls of Dutch (n boys = 83, n girls = 72) and Moroccan origin (n boys = 72, n girls = 79). Mean age for Moroccan adolescents was 13.3 years (SD = 0.55, range 12.2–15.1 years), and mean age for Dutch adolescents was 13.1 years (SD = 0.48, range 12.1–14.4 years). There were no ethnic differences in age and gender distribution.

The sample of Study 2 is part of a larger community sample of adolescents living in The Netherlands [author reference]. In this sample, there was an oversampling of high risk adolescents, as indicated by the Teacher’s Report Form (TRF) that was used as a screening instrument. After the first screening, a group of full families that met the selection criteria was selected. Due to the very intense data collection procedure the refusal rate among these families was 43%. The selected adolescents and their families were visited at their homes by a trained interviewer. In the sample, there were fewer adolescents of Moroccan origin than adolescents of Dutch origin. In order to reach two ethnic subsamples of similar size, we made a random selection of adolescents of Dutch origin.

Measures

Ethnicity

The same definition of Moroccan and Dutch ethnicity was used as in Study 1.

Negative quality of the parent–adolescent relationship

As in Study 1, negative quality of the parent–adolescent relationship was measured by the two subscales Conflict and Antagonism from the Network of Relationship Inventory [11], which were combined into one score for Negative quality of the parent–adolescent relationship. In the present study, the adolescent rated the relationship with mother and father separately. In order to be able to compare the results to those of Study 1, a parent score was created from mean scores of father and mother reports. Cronbach’s alpha of the parent scale was 0.83 and 0.78 for Moroccan and Dutch adolescents, respectively.

Support

Perceived parental support was measured by 8 items from the Network of Relationship Inventory [11] (e.g., ‘How much does your mother really care about you?’). Cronbach’s alpha of the parent scale was 0.85 and 0.88 for Moroccan and Dutch adolescents, respectively.

Autonomy granting

Autonomy granting by parents was measured by the Balanced Relatedness Questionnaire [25]. The questionnaire consisted of 7 items (e.g., ‘My mother respects my own ideas’). Adolescents were asked to rate how much they agreed with the statements on a 4-point scale (1 = I don’t agree at all to 4 = I totally agree). Cronbach’s alpha of parent scale was 0.81 and 0.89 for Moroccan and Dutch adolescents, respectively.

Adolescent disclosure

The disclosure scale of the Parenting Practices Questionnaire [31] was used to measure adolescent disclosure. Like in Study 1, adolescents were asked to indicate how much they tell their parents about their activities (e.g., ‘Does your father know who your friends are?’). The shortened version of the scale consisted of 4 items to be answered on a 5-point scale (1 = never to 2 = always). Cronbach’s alpha of the parent scale was 0.78 and 0.72 for Moroccan and Dutch adolescents, respectively.

Externalizing problem behavior

The same instrument as in Study 1, the Youth Self-Report [1], was used to measure Aggression and Delinquency. Cronbach’s alpha was 0.87 and 0.82 for aggression, and 0.71 and 0.63 for delinquency, for Moroccan and Dutch adolescents, respectively.

Results

Missing values were dealt with in the same way as in Study 1.

Ethnic and gender differences in patterns of association

The same models as in Study 1 were tested, and the results of the model comparison are presented in Table 1. Neither the fully unconstrained (i.e., no gender or ethnic differences), nor the two partially constrained models based on gender and ethnicity provided a better model in comparison with the fully constrained model. We can therefore conclude that there are no meaningful differences in associations between parent–adolescent relationship variables and aggression/delinquency between the four groups based on gender and ethnicity.

Figure 1 shows standardized β between the assessed variables. Both disclosure (β = −0.23) and perceived parental support were significantly related to delinquency (β = −0.25), but not to aggression. Higher levels of disclosure and perceived support were associated with lower levels of delinquency. Higher levels of negative quality of the relationship with parents were related to higher levels of aggression (β = 0.27), and were not related to delinquency. Autonomy granting was not significantly related to levels of aggression or delinquency.

Discussion

The aim of the present research was to examine whether disclosure, negative quality of the parent–adolescent relationship, support, and autonomy granting by parents are similarly associated with delinquency and aggression among adolescent boys and girls of Moroccan and Dutch origin living in the Netherlands.

The results of both studies, in two different samples, indicate that there are no differences between boys and girls of Moroccan or Dutch origin in the way disclosure, negative quality of the parent–adolescent relationship, support, and parental autonomy granting are related to aggression and delinquency. These results are in line with several other studies on parenting, quality of the parent–child relationship, and externalizing problems in adolescents of different ethnic origin [9, 10, 13, 23, 36]. Our results indicate that family processes that affect adolescent development, show a large degree of universality across gender and ethnicity [36]. Studies on harsh punishment seem to be an exception; in several studies across ethnic groups, differences were found in the associations between harsh punishment and adolescent problem behavior [18, 26].

The findings of the present study provide empirical support for the ethnic equivalence model, as proposed by Lamborn and Felbab [16]. Moreover, the fact that we did not find gender and ethnic interactions both in Study 1 and in Study 2 also indicates that the existing theories are suitable not only for adolescents of different ethnic origin, but also for both boys and girls.

The patterns of findings were largely similar for Study 1 and 2. In both studies, adolescent disclosure was more strongly related to delinquency than to aggression. Delinquent behavior is a behavior that typically takes place outside the home, outside the family setting. The more adolescents disclose to their parents about their activities outside the home, the lower their levels of delinquency. Similar strong associations with adolescent delinquent behavior have been found in previous research [27, 30]. With regard to negative quality of the parent–adolescent relationship we found the same result in both studies. The extent to which adolescents quarrel or disagree with their parents is not related to their levels of delinquency, but is strongly related to their levels of aggression. In previous studies, conflict or hostility were found to be important predictors of externalizing problem behavior [e.g., 7, 19]. However, in these studies a combined measure of externalizing behavior was used. In the present study we distinguished between delinquency and aggression. The results from the present study show that conflict and hostility in the parent–adolescent relationship are mainly related to aggression. The negative and coercive interaction patterns in the parent–adolescent relationship seem to spill over directly into adolescent interpersonal aggression. The more overt character of aggression seems to be related directly to negative and coercive interaction patterns in the parent–adolescent relationship, whereas the covert character of delinquent behavior seems to be specifically related to a lack of disclosure in the parent–adolescent relationship.

We also found some differences in patterns of findings between Study 1 and Study 2. These differences mainly concerned the associations of support and autonomy granting with delinquency and aggression. In Study 1, autonomy granting is weakly related only to aggression, and not to delinquency. In Study 2, support is only related to delinquency, and not to aggression. In previous studies, both variables have been found important predictors of lower levels of externalizing problem behavior. However, several studies have also shown that with increasing age, perceived parental support becomes less important, whereas autonomy granting by parents becomes more important in predicting adolescent problem behavior [e.g., 20, 24]. Although the differences in patterns of findings appear to be very small, they could be a consequence of the differences in age of the adolescents in both studies, since the adolescents in Study 1 are older (M age = 14.9 years) than the adolescents in Study 2 (M age = 13.3 years). This could indicate an age effect for support and autonomy: autonomy is a significant predictor for externalizing problems for older adolescents, whereas support is a significant predictor for younger adolescents.

A valuable strength of the present study is that some of the inconsistency in results of previous studies was addressed by the replication in two different samples using similar measures, and also by examining possible gender and ethnicity interaction effects in the associations. We think that the consistency in the results of the present study can be partially subscribed to the fact that we were able to compare the same concepts, which were measured and modeled in very similar ways in both samples. Inconsistency in previous studies seems to be highly dependent on the type of family variable that is being assessed. Studies that have found differences in associations between family variables and adolescent externalizing behavior, mostly examine aspects of harsh parenting [e.g., 8, 14]. Our results, however, are in line with previous studies that examined associations between aspects of family relationship quality. It should be noted that inconsistent results of previous studies can also be due to differences in variance and absolute value of the variables that were assessed. These differences in variance can lead to differences in the strength of the associations between family variables and adolescent problem behavior.

A second strength of the present study is that delinquency and aggression were examined separately, rather than in one construct of externalizing problem behavior. This way, differences in the associations with aspects of the parent–adolescent relationship became visible. Some limitations of the present study should also be noted. First, in the present study we used only cross-sectional data. Longitudinal data would provide additional information concerning changes in the associations over time. Another limitation is that in both samples, data of only one informant was used, namely reports of the adolescents. However, some researchers find that adolescent perceptions on parenting behavior or family relationships, are the strongest predictors of adolescent adjustment [12].

Notwithstanding these limitations, it seems that the existing western-based theories on how parenting and the parent–child relationship are related to adolescent externalizing problem behavior, are also applicable to adolescent boys and girls of Moroccan origin living in the Netherlands. It therefore seems more important—in both research and clinical practice—to focus on the relationship between parenting and family processes in adolescents in general, rather than on ethnicity or gender differences.

Acknowledgments

In this article, data of the RADAR study were used. RADAR has been financially supported by the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (GB-MAGW 480-03-005), and Stichting Achmea Slachtoffer en Samenleving (SASS), and various other grants from the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research, the VU University Amsterdam and Utrecht University.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Footnotes

Tables with descriptive information of all assessed variables for both Study 1 and Study 2 can be obtained from Veroni I. Eichelsheim.

References

- 1.Achenbach TM. Manual for the youth self-report and 1991 profile. Burlington: University of Vermont, Department of Psychiatry; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barnes GM, Farell MP. Parental support and control asp of adolescent drinking, delinquency, and related problem behaviors. J Marriage Fam. 1992;54:763–776. doi: 10.2307/353159. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barnes GM, Hoffman JH, Welte JW, Farrell MP, Dintcheff BA. Effects of parental monitoring and peer deviance on substance use and delinquency. J Marriage Fam. 2006;68:1084–1104. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2006.00315.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barnow S, Lucht M, Freyberger HJ. Correlates of aggressive and delinquent conduct problems in adolescence. Aggress Behav. 2005;31:24–39. doi: 10.1002/ab.20033. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bengi-Arslan L, Verhulst FC, van der Ende J, Erol N. Understanding childhood problem behaviors from a cultural perspective: comparison of problem behaviors and competencies in Turkish immigrant, Turkish and Dutch children. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 1997;32:477–484. doi: 10.1007/BF00789143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beyers W, Goossens L. Emotional autonomy, psychosocial adjustment and parenting: interactions, moderating and mediating effects. J Adolesc. 1999;22:753–769. doi: 10.1006/jado.1999.0268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Buehler C. Parents and peers in relation to early adolescent problem behavior. J Marriage Fam. 2006;68:109. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2006.00237.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Deater-Deckard K, Dodge KA, Bates JE, Pettit GS. Physical discipline among African American and European American mothers: links to children’s externalizing behaviors. Dev Psychol. 1996;32:1065. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.32.6.1065. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dekovic M, Wissink IB, Meijer AM. The role of family and peer relations in adolescent antisocial behaviour: comparison of four ethnic groups. J Adolesc. 2004;27:497–514. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2004.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Forehand R, Miller KS, Dutra R, Watts Change M. Role of parenting in adolescent deviant behavior: replications across and within two ethnic groups. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1997;65:1036–1041. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.65.6.1036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Furman W, Buhrmester D. Children’s perceptions of the personal relationships in their social networks. Dev Psychol. 1985;21:1016–1024. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.21.6.1016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Glasgow KL, Dornbusch SM, Troyer L, Steinberg L, Ritter PL. Parenting styles, adolescents’ attributions, and educational outcomes in nine heterogeneous high schools. Child Dev. 1997;68:507–529. doi: 10.2307/1131675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gorman-Smith D, Tolan PH, Zelli A, Huesmann LR. The relation of family functioning to violence among inner-city minority youths. J Fam Psychol. 1996;10:115. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.10.2.115. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ho C, Bluestein DN, Jenkins JM. Cultural differences in the relationship between parenting and children’s behavior. Dev Psychol. 2008;44:507. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.44.2.507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jöreskog K, Sörbom D (2003) LISREL. In: Scientific Software International

- 16.Lamborn SD, Felbab AJ. Applying ethnic equivalence and cultural values models to African-American teens’ perceptions of parents. J Adolesc. 2003;26:601–618. doi: 10.1016/S0140-1971(03)00059-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lamborn SD, Dornbusch SM, Steinberg L. Ethnicity and community context as moderators of the relations between family decision making and adolescent adjustment. Child Dev. 1996;67:283. doi: 10.2307/1131814. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lansford JE, Deater-Deckard K, Dodge KA, Bates JE, Pettit GS. Ethnic differences in the link between physical discipline and later adolescent externalizing behaviors. J Child Psychol Psychiatr. 2004;45:801–812. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00273.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Low SM, Stocker C. Family functioning and children’s adjustment: associations among parents’ depressed mood, marital hostility, parent–child hostility, and children’s adjustment. J Fam Psychol. 2005;19:394. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.19.3.394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Meeus W, Branje S, Overbeek GJ. Parents and partners in crime: a six-year longitudinal study on changes in supportive relationships and delinquency in adolescence and young adulthood. J Child Psychol Psychiatr. 2004;45:1288–1298. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00312.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.NIDI . Marokkanen in Nederland: Een profiel/Moroccans in The Netherlands: a profile. In: de Beer J, Dykstra P, van Poppel F, editors. NIDI rapport. Den Haag: Nederlands Interdisciplinair Demografisch Instituut; 2006. pp. 1–89. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rothbaum F, Weisz JR. Parental caregiving and child externalizing behavior in nonclinical samples: a meta-analysis. Psychol Bull. 1994;116:55. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.116.1.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rowe DC, Vazsonyi AT, Flannery DJ. No more than skin deep: ethnic and racial similarity in developmental process. Psychol Rev. 1994;101:396–413. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.101.3.396. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Scholte RHJ, van Lieshout CFM, van Aken MAG. Perceived relational support in adolescence: dimensions, configurations, and adolescent adjustment. J Res Adolesc. 2001;11:71–94. doi: 10.1111/1532-7795.00004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shulman S, Laursen B, Kalman Z, Karpovsky S. Adolescent intimacy revisited. J Youth Adolesc. 1997;26:597–617. doi: 10.1023/A:1024586006966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Smith C, Krohn MD. Delinquency and family life among male adolescents: the role of ethnicity. J Youth Adolesc. 1995;24:69–93. doi: 10.1007/BF01537561. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Soenens B, Vansteenkiste M, Luyckx K, Goossens L. Parenting and adolescent problem behavior: an integrated model with adolescent self-disclosure and perceived parental knowledge as intervening variables. Dev Psychol. 2006;42:305. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.42.2.305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stanger C, MacDonald VV, McConaughy SH, Achenbach TM. Predictors of cross-informant syndromes among children and youths referred for mental health services. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 1996;24:597. doi: 10.1007/BF01670102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stanger C, Achenbach TM, Verhulst FC. Accelerated longitudinal comparisons of aggressive versus delinquent syndromes. Dev Psychopathol. 1997;9:43–58. doi: 10.1017/S0954579497001053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stattin H, Kerr M. Parental monitoring: a reinterpretation. Child Dev. 2000;71:1072–1085. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stattin H, Kerr M. What parents know, how they know it, and several forms of adolescent adjustment: further support for a reinterpretation of monitoring. Dev Psychol. 2000;36:366–380. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.36.3.366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Steinberg L, Silk JS. Parenting adolescents. In: Bornstein MH, Webber B, editors. Handbook of parenting. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2002. pp. 103–133. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stevens GWJM, Pels T, Bengi-Arslan L, Verhulst FC, Vollebergh WAM, Crijnen AAM. Parent, teacher, and self-reported problem behavior in the Netherlands: comparing Moroccan immigrant with Dutch and with Turkish immigrant children and adolescents. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2003;38:576–585. doi: 10.1007/s00127-003-0677-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stevens GWJM, Vollebergh WAM, Pels TVM, Crijnen AAM. Predicting externalizing problems in Moroccan immigrant adolescents in the Netherlands. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2005;40:571–579. doi: 10.1007/s00127-005-0926-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stevens GWJM, Vollebergh W, Pels T, Crijnen A. Parenting and internalizing and externalizing problems in Moroccan immigrant youth in the Netherlands. J Youth Adolesc. 2007;36:685. doi: 10.1007/s10964-006-9112-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vazsonyi AT, Trejos-Castillo E, Huang L. Are developmental processes affected by immigration? Family processes, internalizing behaviors, and externalizing behaviors. J Youth Adolesc. 2006;35:799–813. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vollebergh WAM, ten Have M, Dekovic M, Oosterwegel A, Pels T, Veenstra R, de Winter A, Ormel H, Verhulst F. Mental health in immigrant children in the Netherlands. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2005;40:489. doi: 10.1007/s00127-005-0906-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wissink IB, Dekovic M, Meijer AM (2002) Ethnic differences in parenting behavior and in its effects on adolescent externalizing problem behavior. Paper presented at European society on family relations, Nijmegen