Abstract

Background:

Liver failure has remained a major cause of mortality after hepatectomy, but it is difficult to predict preoperatively. This study describes the introduction into clinical practice of the new LiMAx test and provides an algorithm for its use in the clinical management of hepatic tumours.

Methods:

Patients with hepatic tumours and indications for hepatectomy were investigated perioperatively with the LiMAx test. In one patient, analysis of liver volume was carried out with preoperative three-dimensional virtual resection.

Results:

A total of 329 patients with hepatic tumours were evaluated for hepatectomy. Blinded preoperative LiMAx values were significantly higher before resection (n= 139; mean 351 µg/kg/h, range 285–451 µg/kg/h) than before refusal (n= 29; mean 299 µg/kg/h, range 223–376 µg/kg/h; P= 0.009). In-hospital mortality rates were 38.1% (8/21 patients), 10.5% (2/19 patients) and 1.0% (1/99 patients) for postoperative LiMAx of <80 µg/kg/h, 80–100 µg/kg/h and >100 µg/kg/h, respectively (P < 0.0001). A decision tree was developed to avoid critical values and its prospective preoperative application revealed a reduction in mortality from 9.4% to 3.4% (P= 0.019).

Discussion:

The LiMAx test can validly determine liver function capacity and is feasible in every clinical situation. Combination with virtual resection could enable the calculation of residual liver function. The LiMAx decision tree algorithm for hepatectomy might significantly improve preoperative evaluation and postoperative outcome in liver surgery.

Keywords: liver function, hepatectomy, methacetin

Introduction

Predicting postoperative hepatic dysfunction is becoming increasingly important as surgeons pursue a more aggressive approach to achieving complete tumour resection.1 Accordingly, residual liver function has become the major limitation for surgical treatment.2 Small residual liver volume can result in significant problems in terms of postoperative liver function, as well as effective liver regeneration.3,4 Postoperative liver failure (PLF) remains a major cause of mortality after liver resection.2 Outcome and prognosis are closely associated with the occurrence of PLF, which is always a life-threatening complication with high mortality.2,5 A meta-analysis estimated the overall incidence of PLF after hepatectomy to lie between 0.7% and 9.1%.5 Actual mortality rates outside reported studies may be even higher,6 reducing the overall benefit of hepatic resection and increasing the health economic burden.7 Currently, the accurate determination of liver function and prediction of residual liver function represent significant challenges in perioperative patient evaluation and monitoring.

Conventional blood parameters of liver function, such as liver enzymes, albumin, bilirubin or INR, as well as scoring systems derived from those values (such as Child–Pugh or Model of End-Stage Liver Disease [MELD] scores) have been shown to be unreliable for the prediction of the residual liver function.2,8,9 Similarly, volumetric analysis of computed tomography (CT) cannot reliably predict a patient's outcome.3 Several dynamic tests for the assessment of liver function have been developed, including non-invasive breath tests, blood elimination tests and scintigraphy.10–12 However, there is no single test which can accurately predict residual liver function and individual outcome. Thus, preoperative testing to predict residual liver function has not been part of the routine clinical management of most patients considered for hepatic resection.

A novel test protocol, designated the LiMAx test, has been developed at the Department of General, Visceral and Transplantation Surgery at the Charité Hospital in Berlin since 2003 to overcome these limitations. The aim of this study was to develop a decision tree algorithm incorporating the LiMAx test for preoperative patient evaluation prior to hepatic resection.

Materials and methods

Patients

The clinical evaluation of the LiMAx test in perioperative monitoring for hepatectomy was based on 168 patients who participated in different prospective studies during 2004–2008 (Stockmann et al., 2009, unpublished data). These studies were analogously performed in a non-controlled observational design in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Patients with malignant hepatic tumours, who had been successfully evaluated for hepatectomy, were asked to undergo additional perioperative monitoring with the LiMAx test. Thus tumours of different etiologies and subject to different surgical procedures were included. The selection of patients was influenced mainly by administrative issues and not by individual characteristics. Responsible medical personnel were blinded to preoperative LiMAx readouts. Postoperative liver function was monitored until day 10. Outcome and survival were followed until discharge from the hospital. The study protocols received prior approval by the faculty's ethics committee and written informed consent was obtained from each patient before enrolment.

In addition, a total of 161 patients were preoperatively evaluated with the LiMAx test from January 2008 (Routine group). The test was applied as an additional test during routine preoperative patient evaluation. No regular follow-up LiMAx test after surgery was performed. The decision for LiMAx evaluation was individually and non-systematically made by the responsible surgeons. Thus the LiMAx test was mainly applied before critical resections with expected small residual liver volumes or in cases of pre-existing hepatic impairment. Written informed consent was also collected from each of these patients.

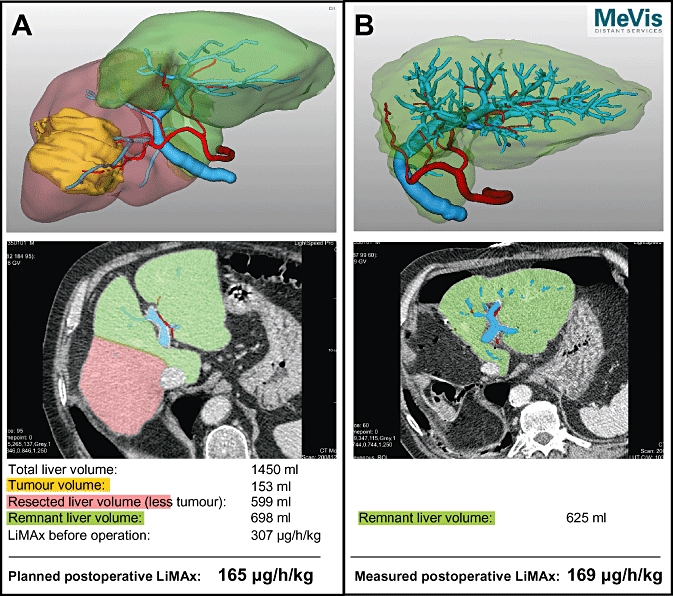

Prospective volume and function analysis before surgery was applied in one patient by a combination of volume planning using virtual resection based on a conventional CT scan together with a measurement of preoperative liver function capacity obtained using the LiMAx test. The preoperative, multilayer, four-phase, contrast-enhanced CT scan was transferred into specific software for virtual three-dimensional analysis and resection (MeVis LiverExplorer; Fraunhofer MeVis, Institute for Medical Image Computing, Bremen, Germany). The virtual resection was performed in direct cooperation with the responsible surgeon on the day prior to hepatectomy.

Performance of the LiMAx test

The LiMAx test is based on the hepatocyte-specific metabolism of the 13C-labelled substrate (methacetin; Euriso-top, Saint-Aubin Cedex, France) by the cytochrome P450 1A2 enzyme, which is ubiquitously active throughout the liver.13 After i.v. injection, the 13C-methacetin is instantly metabolized into acetaminophen and the demethylated 13C-group is converted into 13CO2, which is pulmonarily exhaled. Hence, the administration of 13C-methacetin leads to a significant alteration of the normal 13CO2 : 12CO2 ratio (Pee Dee Belemnite standard 1.1237%14) in the expired breath. This alteration is determined by a suitable device which is directly connected to the patient (online measurement). Breath analysis is performed automatically. Liver function capacity is calculated from the kinetic analysis of the 13CO2 : 12CO2 ratio over a period of 60 min. The protocol has been recently described in detail.15

|

The resection of a certain percentage of functional liver volume leads to an equivalent decrease in the LiMAx value after surgery. LiMAx test readouts were highly correlated with functional liver volume (r = 0.94; P < 0.001) and thus the LiMAx test was assumed to represent an accurate surrogate parameter of liver function capacity.15

Statistical analysis

Descriptive data are shown as medians with interquartile range (IQR) unless otherwise noted. Patients were retrospectively dichotomized into deceased and survivors to compare the progression of LiMAx values. In addition, patients were retrospectively classified by their residual postoperative day 1 LiMAx values to compare mortality rates between groups. Univariate analysis was carried out by chi-squared test, Fisher's exact test, Mann–Whitney U-test, Kruskal–Wallis test or t-test in accordance with the data scale and distribution. The level of significance was 0.05 (two-sided). The analyses were performed using spss 15.0 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

A total of 329 patients with hepatic tumours were evaluated for hepatectomy and 59 (17.9%) were refused surgery. Forty-two patients (12.8%) underwent explorative laparotomy without hepatectomy. Postoperative mortality in the 228 patients who underwent hepatectomy was 7.0% (16 patients). The median (IQR) length of stay was 17 days (11–30 days), including a median (IQR) stay of 2 days (1–6 days) in intensive care. The characteristics of patients in the two different patient cohorts are provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics

| Study group | Routine group | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2005–2008 | 2008–2009 | ||

| Patients, n | 168 | 161 | |

| Age, years, median (IQR) | 63 (53–69) | 62 (53–70) | 0.835a |

| Male gender, n (%) | 106 (63.1%) | 102 (63.4%) | 0.668b |

| Aetiology | 0.005b | ||

| Colorectal metastases, n (%) | 32 (19.0%) | 34 (21.1%) | |

| Hepatocellular cancer, n (%) | 30 (17.8%) | 46 (28.6%) | |

| Cholangiocarcinoma, n (%) | 26 (15.5%) | 22 (13.7%) | |

| Klatskin tumour, n (%) | 55 (33.7%) | 26 (16.1%) | |

| Other, n (%) | 25 (14.9%) | 33 (20.5%) | |

| Preoperative LiMAx, µg/kg/h, median (IQR) | 346 (269–444) | 323 (239–405) | 0.037 |

| Surgery | <0.0001c | ||

| None, n (%) | 10 (6.0%) | 49 (30.4%) | |

| Only laparotomy, n (%) | 19 (11.8%) | 23 (14.3%) | |

| Minor resection, n (%) | 16 (9.5%) | 26 (16.1%) | |

| Hemi-hepatectomy, n (%) | 79 (47.0%) | 48 (29.8%) | |

| Trisectorectomy | 44 (26.2%) | 15 (9.3%) | |

| Mortality (intra-hospital after hepatectomy), n (%) | 13 (9.4%) | 3 (3.4%) | 0.019d |

Statistical analysis by

t-test for independent samples,

chi-squared test,

Mann–Whitney U-test and

Fisher's exact test

IQR, interquartile range

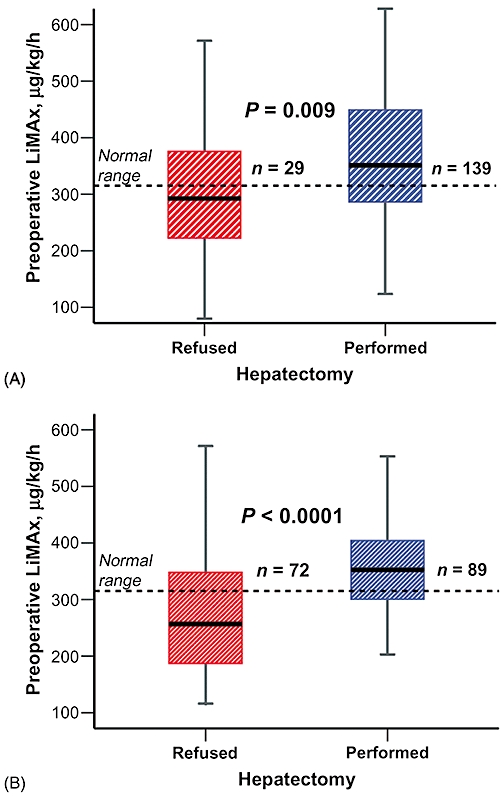

Study group

The clinical application of the LiMAx test began with an observational trial (Study group). Retrospective analysis revealed that preoperative median (IQR) LiMAx values of those who underwent hepatectomy and recovered vs. those who deceased after hepatectomy were identical (354 µg/kg/h [289–458 µg/kg/h] vs. 339 µg/kg/h [250–421 µg/kg/h]; P= 0.279). Interestingly, the overall preoperative LiMAx values of study patients (n= 139) who underwent surgery were significantly higher in comparison with those of patients who were refused resection (n= 29) (Fig. 1A). Although decisions for surgery were made independently of individual LiMAx values, the LiMAx of refused patients was 299 µg/kg/h (223–376 µg/kg/h) and thus below the normal range (>315 µg/kg/h) in the majority of patients (64.3%). The LiMAx of actually resected patients was 351 µg/kg/h (285–451 µg/kg/h) (P= 0.009) and thus mostly within the normal range (65.5%) (Fig. 1A).

Figure 1.

Preoperative LiMAx evaluation. The box plots present LiMAx values determined during preoperative evaluation, divided into resected patients and patients refused surgery. Different results were obtained during (A) the initial clinical studies and (B) the later routine application of the LiMAx test. Boxes indicate medians with interquartile ranges; bars represent minimum and maximum values

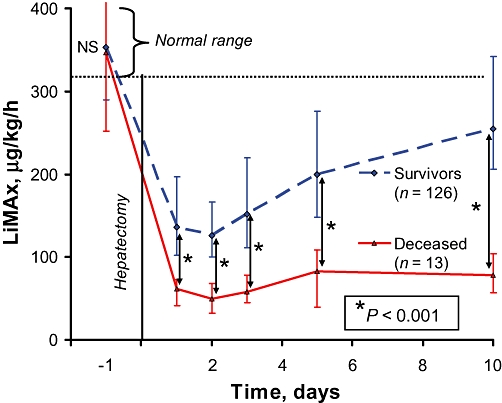

Postoperative LiMAx and functional regeneration in this cohort revealed significantly different values between survivors and deceased patients, as shown in Fig. 2. LiMAx values in the deceased group were extremely low after surgery (62 µg/kg/h [41–73 µg/kg/h] vs. 136 µg/kg/h [102–197 µg/kg/h]; P < 0.0001). The effects of postoperatively decreased values on need for intensive care, length of stay and survival are shown in Table 2. In-hospital mortality rates were 38.1% (8/21 patients), 10.5% (2/19 patients) and 1.0% (1/99) for LiMAx values of <80 µg/kg/h, 80–100 µg/kg/h and >100 µg/kg/h, respectively (P < 0.0001). The cause of death for the one patient who died with a postoperative LiMAx of 101 µg/kg/h was haemorrhagic shock secondary to an acute peptic ulcer bleeding 4 weeks after hepatectomy from which he developed multiple organ dysfunction syndrome.

Figure 2.

Development of liver function after hepatectomy, showing the perioperative course of liver function capacity, as determined by the LiMAx test. The patients were divided into surviving and deceased groups. Median values with error bars represent 75% and 25% quartiles. LiMAx readouts were compared using the Mann–Whitney U-test. Data for the following tests were available:

| Day | −1 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 5 | 10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Deceased patients (n= 13) | 13 | 9 | 7 | 11 | 8 | 8 |

| Survivors (n= 126) | 126 | 111 | 58 | 99 | 97 | 93 |

Table 2.

Postoperative LiMAx values and clinical outcomes in 139 patients

| <80 µg/kg/h | 80–100 µg/kg/h | 100–150 µg/kg/h | >150 µg/kg/h | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients, n (%) | 21 (15.1%) | 19 (13.7%) | 42 (30.2%) | 57 (41.1%) | |

| Intensive care, days, median (IQR) | 12 (4–26) | 3 (1–16) | 2 (1–4) | 1 (1–3) | <0.0001a |

| Hospitalization, days, median (IQR) | 25 (17–35) | 20 (15–39) | 16 (13–41) | 14 (10–26) | 0.056a |

| In-hospital mortality, n (%) | 8 (38.1%) | 2 (10.5%) | 1 (2.4%) | 0 | <0.0001b |

Patients receiving hepatectomy (n= 139) were classified into four categories by LiMAx readouts on postoperative day 1. This classification was compared with length of stay (in the intensive care unit and general ward) and mortality during the hospital stay

Statistical analysis by

Kruskal–Wallis test,

chi-squared test

IQR, interquartile range

Routine group

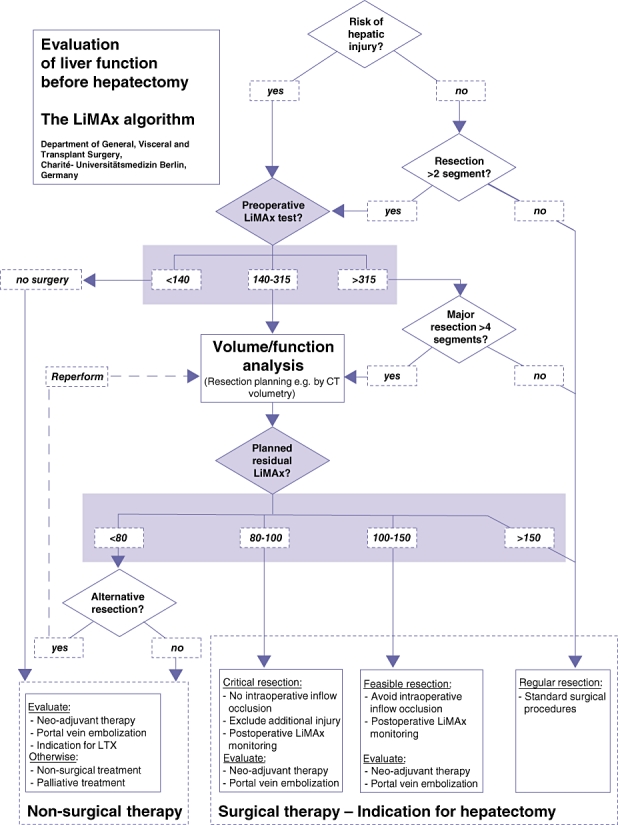

A total of 161 patients underwent a preoperative LiMAx as part of their routine preoperative testing prior to consideration for hepatic resection. The demographics and outcomes of this group are compared with those of the Study group in Table 1. A decision tree algorithm was developed during this period, shown in Fig. 3. This was mainly used to evaluate patients whose histories indicated a risk for hepatic injury. Eventually 72 (44.7%) of the evaluated patients were excluded from hepatectomy (median [IQR] LiMAx values of 257 µg/kg/h [175–348 µg/kg/h] vs. 356 µg/kg/h [301–425 µg/kg/h]; P < 0.0001) (Fig. 1B). Patients who underwent explorative laparotomy without hepatectomy (n= 23) had median (IQR) LiMAx values of 285 µg/kg/h (239–347 µg/kg/h), whereas those who were directly refused surgery had LiMAx values of 240 µg/kg/h (163–369 µg/kg/h) (P= 0.159). Postoperative mortality after hepatectomy was only 3.4% and thus lower than in the prior period in which LiMAx readouts were blinded (P= 0.019) (Table 1).

Figure 3.

The LiMAx algorithm: a clinical decision tree for preoperative evaluation before hepatectomy. LTX, liver transplant; CT, computed tomography

Discussion

The lack of an accurate preoperative test with which to predict postoperative outcome before hepatectomy was the motivation for the development of a novel test protocol for a bedside breath test with 13C-methacetin.15 Fundamental methodological considerations and the need to adapt the test to the practical needs of surgical management led to the design of a completely new test protocol with i.v. substrate administration, real-time online assessment and an automatic kinetic analysis with prompt test readouts. These specifications were seen as preconditions for achieving reliable test results with clinical meaning, as well as ensuring a high clinical utility of the test system, so that any medical specialist can easily perform the test. The LiMAx test would seem to meet these criteria.

Previous work by the authors has shown the LiMAx to be an independent predictor of PLF and mortality.15 The evaluation of diagnostic power consequently revealed a high individual validity, as shown during area under receiver operating characteristic curve (AUROC) analysis.15 The critical point for PLF was identified as a postoperative LiMAx value of <85 µg/kg/h. In addition, poor but uncritical LiMAx values in the initial postoperative phase have been associated with secondary severe complications, such as postoperative bleeding, pleural effusions or septic infections.15 Normal values were retrieved from a group of healthy volunteers and determined as LiMAx > 315 µg/kg/h.15

The current study shows that, even without the benefit of LiMAx test results, surgeons are more likely to decline patients with poorer preoperative hepatic function. However, by contrast with this group-based strategy, valid individual prediction could be significantly improved with the new LiMAx test, allowing individual patient management according to the developed algorithm (Fig. 3). Another important advantage is that it may allow surgeons to offer surgery to patients they might previously have declined. Two patients within the Routine group had previously been declined surgery because of the extent of their cirrhosis. LiMAx values were obtained (392 µg/kg/h and 511 µg/kg/h) and both patients subsequently underwent major hepatectomy (right hemi-hepatectomy and trisectorectomy) and were discharged after 21 and 17 days, respectively.

Although preoperative hepatic function is important, residual function and its ability to regenerate are also crucial to short-term outcomes, as shown in the current study (Table 2). However, it is also important to consider intraoperative factors such as blood loss and warm ischaemic time, which may have deleterious effects on postoperative function. The LiMAx can assist in identifying these patients early in the postoperative period.15

Since January 2008, the LiMAx test has become available in routine preoperative evaluation. Clearly, the proportional increase in the number of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and the number of patients for whom surgery was refused indicate that surgeons have chosen to use it selectively (Table 1). Although the Routine group represents a potentially higher-risk group, its mortality rate was significantly lower than that seen in the Study group (Table 1). However, given the nature of the study, this difference should be interpreted with caution. A complex decision tree algorithm for preoperative evaluation was developed during the application of the LiMAx test and enhanced with increasing clinical experience. The flowchart in Fig. 3 presents the current decision tree used for patients with malignant hepatic tumours in our department. First of all, the risk for any pre-existing hepatic impairment must be evaluated. This includes the anamnesis of all relevant risk factors for liver disease, such as chronic hepatitis, alcohol abuse, exposure to toxins (environmental or medical, such as chemotherapy), genetic disorders, or obstructive jaundice, as well as the analysis of standard blood parameters in clinical chemistry. If hepatic impairment is unlikely, small resections of up to two liver segments can be performed without further diagnostic workup. If hepatic injury is suspected or larger resections need to be performed, a preoperative assessment of liver function with the LiMAx test is recommended. Normal liver function (LiMAx > 315 µg/kg/h) allows the resection of up to four liver segments without further consideration. By contrast, patients with strongly impaired liver function (LiMAx < 140 µg/kg/h, representing significant hepatic injury) must be refused surgery as they are prone to developing PLF after minor liver resection.

However, the most challenging decisions pertain to patients with intermediate liver function (140–315 µg/kg/h, representing limited hepatic impairment) or a planned resection of more than four segments. In the future preoperative volume and function analysis might effectively augment therapeutic decisions by predicting residual liver function after surgery, as demonstrated in Fig. 4. If this is so, procedures with expected residual LiMAx values of <80 µg/kg/h should not be performed according to the results of the current study (38.1% postoperative mortality). Procedures with expected residual LiMAx values of 80–100 µg/kg/h are still critical (10.5% postoperative mortality) and thus alternative therapies or additional preoperative procedures should be considered. These might include selective portal vein embolization, which could enlarge residual liver volume,16 or neo-adjuvant chemotherapy, which could downstage tumours and thus allow smaller resection volumes.17 In addition, intraoperative procedures such as in- and outflow occlusion (e.g. Pringle manoeuvre) should be strictly limited in these patients in order to minimize additional hepatocellular injury. Procedures with expected residual LiMAx values of >100 µg/kg/h (1.0% postoperative mortality) are feasible with a high degree of safety (Table 2, Fig. 3). Clearly, these cut-off values need to be further validated with prospective studies correlating predicted postoperative volume and function with actual postoperative values.

Figure 4.

Planning of surgery by volume and function analysis, demonstrated by prospective volume and function analysis in one patient. Preoperative LiMAx was 307 µg/kg/h; functional liver volume was 1450 ml, tumour volume was 153 ml. A right hemi-hepatectomy was planned during virtual resection with a functional resection of 599 ml, thus resulting in a residual liver volume of 698 ml (53.8%) and a residual LiMAx of 165 µg/kg/h. The initial postoperative LiMAx test revealed a liver function capacity of 169 µg/kg/h. (A) The preoperative computed tomography (CT) scan is converted into a 3D construction. The tumour is shown in yellow, the planned liver resection in red. A representative slide and the calculated data for surgery are shown beneath. (B) Confirmation of the planned volume in the postoperative CT scan. A representative slide and the measured postoperative values are shown beneath. Portal vein branches are displayed in blue and hepatic artery branches in red

In the future, combined volume and function analysis might be applied in every clinical situation and aetiology, and thus surgical procedures tailored to optimize residual function. However, at present it is important to remember that neither the LiMAx test nor volume planning can currently predict the effect of intraoperative events such as hepatic ischaemia (Pringle manoeuvre) or blood loss. Therefore, it may be sensible to consider retaining a ‘margin for error’ for patients in whom a significant hepatic event is anticipated. Moreover, residual liver function is an essential but not unique limitation of hepatectomy. Therapeutic decisions must include multiple diagnostic parameters and clinical factors. Along with the expected residual function, pre-existing liver diseases, such as liver fibrosis, cholestasis or hepatitis, intraoperative surgical procedures and, of course, tumour stage and the general condition of the patient must be taken into account. Further methodical considerations and clinical studies will aim to optimize the test reliability and individual accuracy, particularly in relation to potential parameters that might bias the individual test result, such as haemodialysis, smoking and nutrition, as well as genetic variations or visceral haemodynamics. Further, it would seem to be appropriate to evaluate the effects of neoadjuvant chemotherapy or preoperative portal-venous embolization in order to provide the surgeon with important information regarding surgical resection following these procedures.1

In conclusion, the LiMAx decision tree algorithm for hepatectomy might significantly improve preoperative evaluation and postoperative outcome in liver surgery.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Institute for Medical Image Computing for providing three-dimensional analysis of computed tomography data. We are also grateful to the entire team of the surgical department for successfully integrating the LiMAx test into routine management. In addition, we would like to thank the staff of the Workgroup for the Liver for performing thousands of liver function tests over the past 5 years, particularly Björn Riecke, Michael Fricke, Sina Lehmann, Eugen Schwabauer, Nikolay Videv, Constantin Weber, Tanja Pilarski, Rhea Röhl, Pouria Taheri, Oliver Kolmer, Sophie Ringe and Moritz Giesecke.

Conflicts of interest

None declared.

References

- 1.Clavien PA, Petrowsky H, DeOliveira ML, Graf R. Strategies for safer liver surgery and partial liver transplantation. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:1545–1559. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra065156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schneider PD. Preoperative assessment of liver function. Surg Clin North Am. 2004;84:355–373. doi: 10.1016/S0039-6109(03)00224-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schindl MJ, Redhead DN, Fearon KC, Garden OJ, Wigmore SJ. The value of residual liver volume as a predictor of hepatic dysfunction and infection after major liver resection. Gut. 2005;54:289–296. doi: 10.1136/gut.2004.046524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mullin EJ, Metcalfe MS, Maddern GJ. How much liver resection is too much? Am J Surg. 2005;190:87–97. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2005.01.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.van den Broek MA, Olde Damink SW, Dejong CH, Lang H, Malago M, Jalan R, et al. Liver failure after partial hepatic resection: definition, pathophysiology, risk factors and treatment. Liver Int. 2008;28:767–780. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2008.01777.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Asiyanbola B, Chang D, Gleisner AL, Nathan H, Choti MA, Schulick RD, et al. Operative mortality after hepatic resection: are literature-based rates broadly applicable? J Gastrointest Surg. 2008;12:842–851. doi: 10.1007/s11605-008-0494-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lock JF, Reinhold T, Malinowski M, Pratschke J, Neuhaus P, Stockmann M. The costs of postoperative liver failure and the economic impact of liver function capacity after extended liver resection – a single-centre experience. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2009;394:1047–1056. doi: 10.1007/s00423-009-0518-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schroeder RA, Marroquin CE, Bute BP, Khuri S, Henderson WG, Kuo PC. Predictive indices of morbidity and mortality after liver resection. Ann Surg. 2006;243:373–379. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000201483.95911.08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen TW, Chu CM, Yu JC, Chen CJ, Chan DC, Liu YC, et al. Comparison of clinical staging systems in predicting survival of hepatocellular carcinoma patients receiving major or minor hepatectomy. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2007;33:480–487. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2006.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gao L, Ramzan I, Baker AB. Potential use of pharmacological markers to quantitatively assess liver function during liver transplantation surgery. Anaesth Intensive Care. 2000;28:375–385. doi: 10.1177/0310057X0002800404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Erdogan D, Heijnen BH, Bennink RJ, Kok M, Dinant S, Straatsburg IH, et al. Preoperative assessment of liver function: a comparison of 99mTc-Mebrofenin scintigraphy with indocyanine green clearance test. Liver Int. 2004;24:117–123. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2004.00901.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brockmoller J, Roots I. Assessment of liver metabolic function. Clinical implications. Clin Pharmacokinet. 1994;27:216–248. doi: 10.2165/00003088-199427030-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Palmer CN, Coates PJ, Davies SE, Shephard EA, Phillips IR. Localization of cytochrome P-450 gene expression in normal and diseased human liver by in situ hybridization of wax-embedded archival material. Hepatology. 1992;16:682–687. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840160311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schoeller DA, Schneider JF, Solomons NW, Watkins JB, Klein PD. Clinical diagnosis with the stable isotope 13C in CO2 breath tests: methodology and fundamental considerations. J Lab Clin Med. 1977;90:412–421. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stockmann M, Lock JF, Riecke B, Heyne C, Martus P, Fricke M, et al. Prediction of postoperative outcome after hepatectomy with a new bedside test for maximal liver function capacity. Ann Surg. 2009;250:119–125. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181ad85b5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Seymour K, Charnley R, Rose J, Baudouin C, Manas D. Preoperative portal vein embolization for primary and metastatic liver tumours: volume effects, efficacy, complications and short-term outcome. HPB (Oxford) 2002;4:21–28. doi: 10.1080/136518202753598690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kemeny N. Pre-surgical chemotherapy in patients being considered for liver resection. Oncologist. 2007;12:825–839. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.12-7-825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]