Abstract

The NIDA Clinical Trials Network recently completed a randomized, open label trial comparing treatment as usual (TAU) combined with nicotine patches plus cognitive behavioral group counseling for smoking cessation (n=153) to TAU alone (n=72) for patients enrolled in treatment programs for drug or alcohol dependence, who were interested in quitting smoking. This report is a secondary analysis evaluating the effect of depressive symptomatology (n=70) or history of depression (n=110) on smoking cessation outcomes. A significant association was seen between measures of depression and difficulty quitting cigarettes. Specifically, there was a greater probability for smoking abstinence for those with lower baseline BDI-ll scores. These data suggest that evaluation and treatment of depressive symptoms may play an important role in improving smoking cessation outcomes.

Keywords: Smoking Cessation, Mood, Depression, Substance Abuse

Introduction

Associations between cigarette smoking and depressive disorders have been reported in both epidemiological1,2 and clinical samples.3,4,5 Most of the smoking cessation outcome studies that have evaluated the association with depression have been conducted in individuals who did not have a concurrent substance use disorder (other than nicotine).5 MDD is highly prevalent among substance abusers 6,7,8 and has been associated with worse substance abuse treatment outcomes.9,10 Although some studies reported alcohol use, which sometimes affected this association, there is very little information on the association between smoking and mood in individuals with a concurrent substance use disorder.

The association between smoking and depression is of particular interest to the drug treatment field, because smoking is an almost ubiquitous and serious health issue in drug treatment patients, and quit rates with treatment are low.11 Thus, addressing depression might provide an opportunity to improve treatment outcome in this population at high risk for adverse smoking related outcomes. Moreover, substance dependent patients have high rates of both smoking and depression, and the relationships between them warrants investigation. Smoking cessation trials to date have generally excluded both patients with depressive disorders and patients with substance use disorders, and this may have limited the ability of those studies to elucidate relationships between smoking and depression.

The National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) Clinical Trials Network (CTN) recently completed an 8-week, multi-center, open-label trial comparing the use of nicotine patches plus smoking cessation group counseling (SC) and treatment as usual (TAU) to TAU alone in a group of substance-dependant outpatients interested in quitting smoking. The purpose of this paper is to evaluate the association between depression and smoking behaviors in the large CTN trial. Specifically, this study sought to evaluate the association between history of major depressive disorder (MDD) and smoking outcomes as well as to evaluate the association between baseline mood and smoking behaviors.

Methods

Data for this secondary analysis comes from the NIDA CTN open-label study comparing TAU plus nicotine patches and smoking cessation counseling (SC) to TAU alone.11 Participants were 225 men and women, at least 18 years of age, currently receiving substance abuse treatment at one of seven community based treatment programs (CTPs) affiliated with the CTN. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of each of the participating sites, and all participants signed an IRB-approved informed consent prior to any study procedures. Although a full description of the methodology for the parent study can be found in the main study findings,11 a brief list of pertinent inclusion and exclusion criteria include: 1) Must be enrolled in an outpatient treatment program for substance dependence, either drug-free or opioid replacement (methadone maintenance), for the last 30 days and scheduled to remain in treatment for 30 days after randomization, 2) Must meet Diagnostic and Statistical Manual, 4th edition12 criteria for drug or alcohol dependence in the last year; or if on opioid replacement must be on stable dose for one year or more, 3) Must smoke at least 10 cigarettes/day and have a carbon monoxide (CO) reading greater than 10 parts per million (ppm), and must have a desire to quit smoking, 4) Could not be receiving any other smoking cessation interventions, 5) Could not have a medical condition in immediate need of treatment or that would be negatively affected by study, and 6) Could not have an acute, severe psychiatric condition in need of immediate treatment, or imminent suicide risk. Current MDD without suicidal ideation was not an exclusion for study participation.

Eligible participants were randomized in a 2:1 fashion to either substance abuse TAU plus nicotine patches and smoking cessation counseling (SC; n=153) or substance abuse TAU alone (n=72). Smoking cessation counseling was conducted in a closed group format and was based on a modified version of the Mood Management and Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Smoking Cessation manual13,14 tailored for individuals receiving substance abuse treatment. Participants randomized to the SC condition were scheduled to receive 9 group smoking cessation counseling sessions, starting the week prior to the target quit date (TQD) and continuing twice weekly for the first two weeks after the TQD and weekly thereafter, through week 6. Open-label NicoDerm CQ patches were initiated on the Target Quit Date at 21mg/day for weeks 1–6 and then decreased to 14mg/day for weeks 7 and 8. Participants randomized to TAU were offered deferred smoking cessation treatment after the completion of the last follow-up visit.

Assessments

Study assessment visits occurred at baseline and then weekly through week 9, with follow-up visits at weeks 13 and 26. Assessments pertinent to this report include: psychiatric and medical history, demographics, DSM-IV checklist for evaluation of substance abuse and dependence diagnoses, Beck Depression Inventory II (BDI-II),15 exhaled CO, Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence,16 smoking history survey, urine drug screen, a modified Minnesota Withdrawal Scale,17,3 and timeline follow-back for self-reported substance use. Although the BDI-II was used to assess for current depressive symptoms, there was no diagnostic assessment used to evaluate for MDD or other psychiatric disorders.

Sample Definition

Baseline Characteristics

In order to evaluate the effect of depression on smoking cessation outcomes, the total sample (n=225) was divided into those who reported ever being treated for depression (major depressive disorder; MDD) based on their psychiatric history information (n=110) vs. those had not (no MDD; n=115). The total sample was also divided into those with and without an elevated BDI-II at baseline. A BDI-II score of 20 or greater is considered clinically significant18 thus, the total sample was divided into those whose baseline BDI-II score was <20 (n=149) vs. those with a baseline BDI-II score of ≥ 20 (n=70).

Data Analysis

The demographic and diagnostic characteristics at baseline were compared across two treatment groups with Chi-square test for categorical variables and t-test for continuous variables. The analytical strategy followed that of the main outcome paper,11 using mixed effect models for continuous repeated measures and generalized linear mixed models (GLMM) for categorical repeated measures.

The primary outcome was 7-day point prevalence of smoking abstinence, assessed at each study visit, defined as a self-report of no smoking confirmed by exhaled breath CO level ≤ 10 ppm. During the treatment phase of the study the smoking abstinence rates were almost zero in the TAU group,11 so only those randomized to SC (n=153) were evaluated to determine if preexisting depression (n=76) or depressive symptoms (n=104) moderated the effect of smoking abstinence. Missing data were imputed as non-abstinent, A GLMM model was used to model the weekly smoking abstinence status as a function of time (weeks 1 through 9), baseline BDI-II score and time by baseline BDI interaction with subject and site as random variables. Tests for the effect of depression were also performed by entering the baseline BDI-II score as a dichotomous variable (<20 vs. ≥ 20) in the model. Similar analyses were conducted in the SC group to evaluate the relationship between the baseline BDI-II score and the secondary outcomes, weekly measures of cigarettes smoked/day, exhaled CO levels, primary substance abuse abstinence, self-reported nicotine withdrawal and craving. Baseline values of the outcome variables were included in the models as covariates when applicable. The effects of the participants’ history of MDD on the primary and secondary outcomes were also explored using similar models described above. PROC MIXED (for mixed effect models) and PROC GLIMMIX (for GLMM models) in SAS19 were used to estimate and test the models.

Results

Association of Depression with Demographic and Clinical Features at Baseline

Data from the primary outcome paper11 did not show any significant differences in demographics between treatment groups and thus are not described here. Study retention was approximately 90% through the end of study intervention and was not associasted with baseline BDI-II score (p=0.84) or history of treatment for depression (p=0.53). Table 1 describes the total sample of 225 participants divided by affective group as well as by high (≥20) and low (< 20) BDI-II baseline scores. As can be seen, 48.9% (n=110) reported a history of being treated for MDD, and 32.0% (n=70) had a baseline BDI-II score of 20 or greater. There was a trend for those with a history of MDD to less likely be employed at baseline (χ2 (1) = 3.42; p=0.064); there was also a trend for the same group to be less educated (t(223)=1.88; p=0.061).

Table 1.

Clinical Characteristics by Affective Group

| Demographics | No MDE (n=115) |

MDE (n=110) |

Test Stat | BDI<20 (n=149) |

BDI≥20 (n=70) |

Test Stat |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 42.3 (10.2) | 42.1 (9.3) | NS | 41.6 (9.3) | 43.8 (10.2) | NS |

| % Male | 57.39 | 46.36 | χ2(1)=2.74 p=0.098 |

52.35 | 51.43 | NS |

| Education (yrs) | 11.8 (2.0) | 11.3 (2.3) | t(223)=1.88 p=0.061 |

11.7 (2.1) | 11.3 (2.2) | NS |

| Race | NS | NS | ||||

| % Caucasian | 34.21 | 42.73 | 37.84 | 37.14 | ||

| % African Am | 28.95 | 23.64 | 26.35 | 28.57 | ||

| % Hispanic | 35.96 | 31.82 | 34.46 | 32.86 | ||

| % Employed | 50.4 | 38.2 | χ2(1)=3.42; p=0.064 |

44.3 | 41.4 | NS |

| Clinical Variables | ||||||

| Baseline BDI-II score | 12.5 (9.5) | 19.6 (12) | t(217)=−4.89 p≤0.001 |

9.6 (5.7) | 29.4 (8.1) | t(217)=20.89 p≤0.001 |

| Primary Substance of Abuse (DSM-IV) |

||||||

| Alcohol (%) | 4.35 | 10.91 | NS | 4.03 | 14.29 | χ2(1)=5.96; p≤0.05 |

| Amphetamines (%) | 5.22 | 3.64 | NS | 6.71 | 0 | χ2(1)=3.50; p=0.06 |

| Cannabis (%) | 6.96 | 10.0 | NS | 6.71 | 12.86 | NS |

| Cocaine (%) | 16.52 | 21.91 | NS | 22.82 | 11.43 | χ2(1)=3.29; p=0.07 |

| Opioids (%) | 63.48 | 50.91 | χ2(1)=3.14; p=0.08 | 57.72 | 55.71 | NS |

| Sedatives (%) | 3.48 | 3.64 | NS | 2.01 | 5.71 | NS |

| Smoking Variables | ||||||

| Age 1st Smoked | 14.3 (4.6) | 13.1 (3.7) | t(223)=2.15 p=0.032 |

13.9 (4.4) | 13.1 (3.8) | NS |

| Age of regular smoking |

16.7 (5.2) | 15.2 (3.7) | t(223)=2.60 p=0.019 |

16.5 (4.9) | 15.0 (3.8) | t(217)=−2.13 p=0.034 |

| Avg. cigarettes per day |

22.1 (10.5) | 24.4 (13) | NS | 21.3 (9.0) | 26.3 (14.6) | t(217)=3.15 p=0.002 |

| % Use of non-cig tobacco |

22.6 | 25.5 | NS | 22.2 | 27.1 | NS |

| # quit attempts | 5.6 (15.9) | 4.7 (5.7) | NS | 4.6 (12.0) | 6.4 (12.6) | NS |

| Baseline Fagerström | 5.3 (2.0) | 6.6 (1.9) | t(223)=−4.93 p≤0.001 |

5.6 (2.1) | 6.6 (1.8) | t(217)=3.46 p≤0.001 |

It is important to note that opioids were the primary substance of abuse for the majority (57.3%; n=129) of participants. Most of the recruitment sites used in this trial were opioid replacement programs. When evaluating primary substance by affective group, there was a trend for history of MDD to be less frequent in those with primary opioid use (p=0.08). Also in Table 1, alcohol was more often the primary substance of abuse for those with a BDI-ll ≥ 20 compared to those with a BDI-ll<20 (p≤0.05), and there was a trend (p=0.07 and; p=0.06, respectively) for a higher percentage of cocaine and amphetamine as primary for those with a BDI-ll score <20.

Those with a history of MDD had earlier age of smoking initiation (t(223)=2.15; p=0.032) as well as an earlier age of regular smoking (t(223)=2.60; p=0.019). Individuals with a higher baseline BDI-II were found to smoke more cigarettes than those with a BDI-II < 20 (t(217)=3.15; p=0.002). Similarly, individuals with history of MDD or a baseline BDI-II score ≥ 20 were found to have higher Fagerstrom scores for nicotine dependence (t(223)=4.93; p<0.001). Although not depicted in Table 1, most of the recruitment sites used in this trial were opioid replacement programs, thus opioids were the primary substance of abuse for the majority (57.3%; n=129) of participants.

Association of Depression at Baseline with Smoking Treatment Outcomes

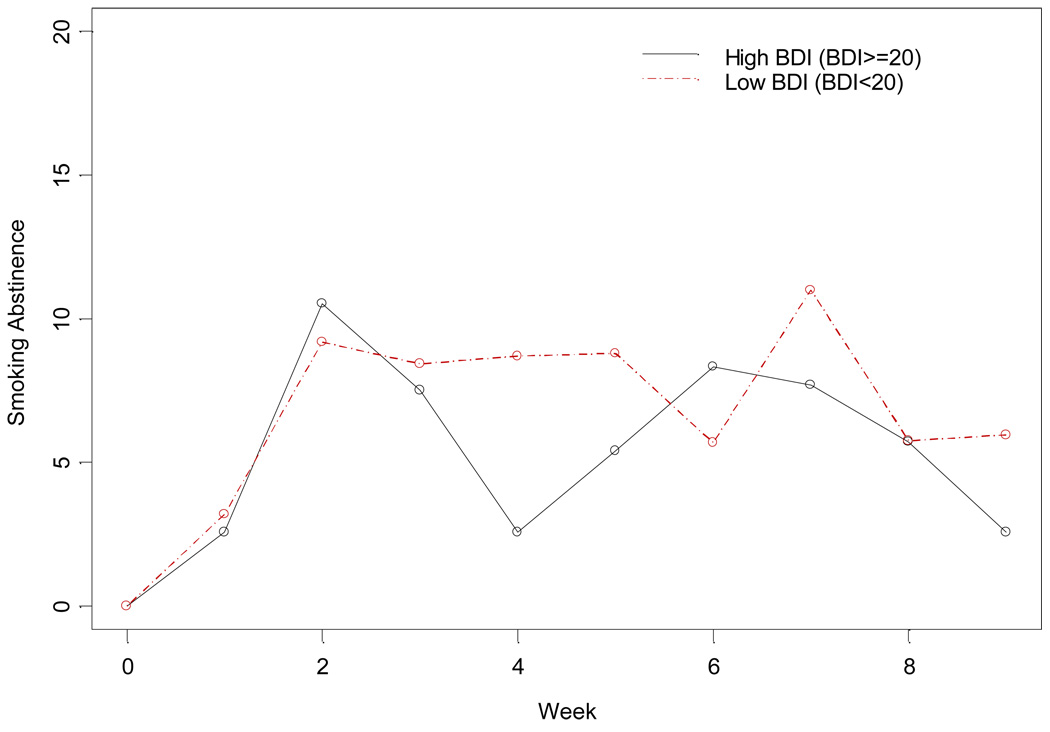

As stated above, to determine if depression moderated the effect of smoking abstinence, only those randomized to SC were evaluated. There is no strong evidence that history of MDD moderated the effect of treatment on smoking abstinence per se, however associations between MDD and other smoking outcomes were observed as described below. Lower baseline BDI-II scores were significantly associated with greater likelihood of smoking abstinence (F(1108)=4.07; p=0.044). This association is illustrated in Figure 1 where the BDI-II is dichotomized into high versus low subgroups for purposes of illustration.

Figure 1.

Smoking Abstinence by Baseline BDI

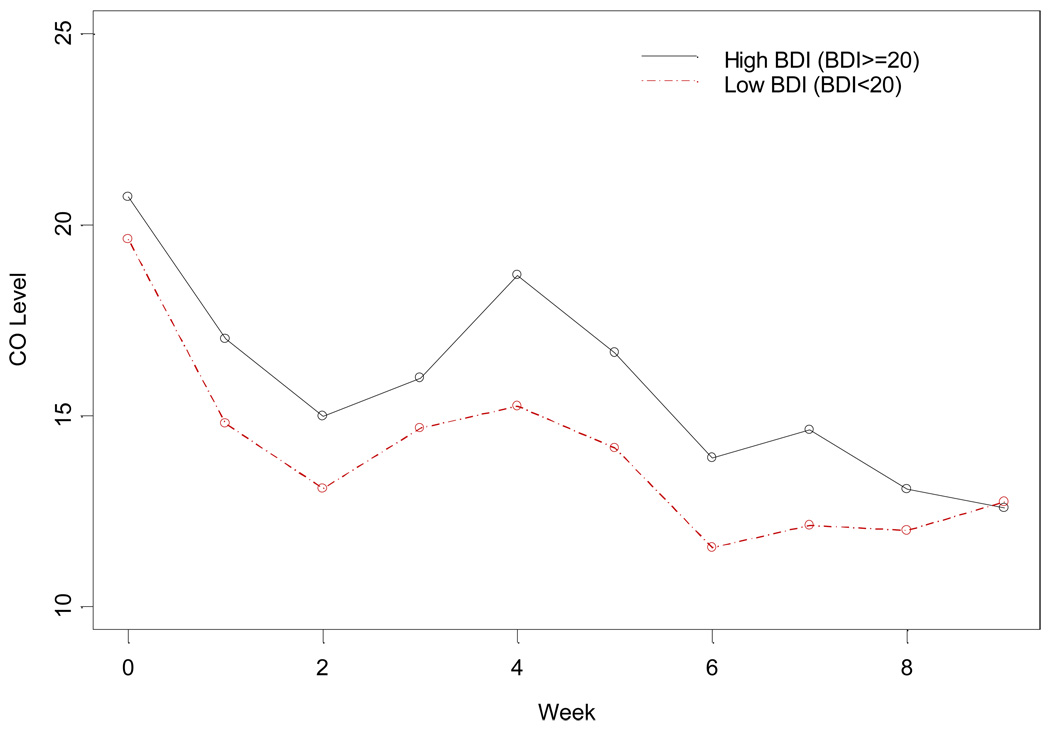

Consistent with the above findings, baseline BDI-II scores were also associated with expired carbon monoxide (CO) levels. Higher baseline BDI-II scores predicted higher CO levels during the study (F(946)=2.08; p=0.037; see Figure 2). There was a significant interaction effect between MDD and baseline CO level (t(864)=2.40; p=0.017). Individuals with a history of MDD and high baseline CO levels had higher CO levels during the course of the study than those without MDD, while the effect of MDD was much smaller for individuals with low baseline CO levels. Interestingly, although there was an association between baseline BDI-II score and smoking abstinence, baseline BDI-II score was not associated with the number of cigarettes smoked per day for those who did not achieve abstinence (F(919)=0.6; p=0.439). However, an interaction was seen between MDD and baseline cigarettes per day (F(804)=9.52; p=0.0021). Individuals with a history of MDD and high baseline cigarettes per day showed a greater reduction in cigarettes per day, similar to the findings with CO levels. There was no effect of baseline BDI or history of BDI on smoking abstinence at either of the follow up time points (week 13 and 26).

Figure 2.

Expired CO by baseline BDI

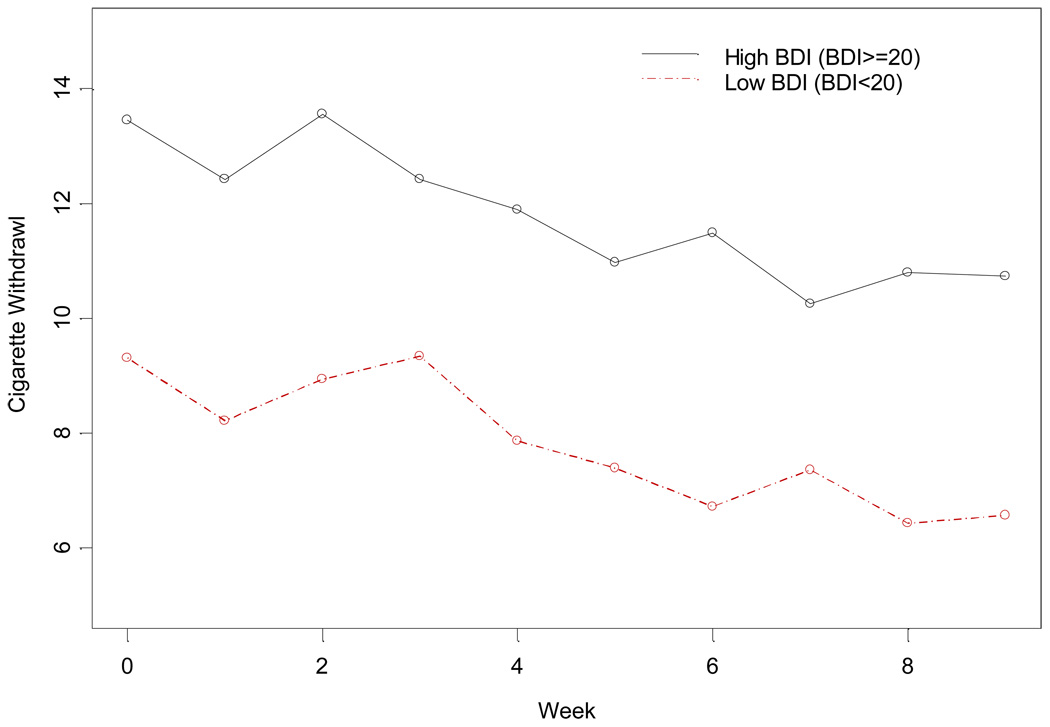

Other outcomes evaluated include nicotine withdrawal symptoms, craving, and abstinence of other substances of abuse. Figure 3 shows the changes of the participants’ nicotine withdrawal with low baseline BDI-II score (< 20) and with high baseline BDI-II score (≥ 20) in the SC group during the treatment phase. Higher baseline BDI-II scores were significantly associated with higher nicotine withdrawal symptoms (t(185)=2.91; p=0.004), and higher craving scores (t(211)=2.55; p=0.012) during SC treatment. Similarly, individuals with a history of major depression were also found to have higher nicotine withdrawal symptoms (t(874)=2.04; p=0.042) and greater craving (t(116)=2.09; p=0.039).

Figure 3.

Nicotine withdrawal by baseline BDI

Neither baseline BDI-II scores nor history of MDD were associated with use of other substances of abuse during the course of the study.

Discussion

Approximately half of the total sample in this trial had a history of MDD, and a third had clinically significant baseline BDI-II scores (≥ 2 0; signifying moderate depression). When evaluating the relationship between these measures of depression and smoking outcomes, an association was found in which higher symptoms of depression were associated with greater smoking severity as well as poorer smoking cessation outcomes. More specifically, participants with a history of MDD reported an earlier age of cigarette smoking and greater nicotine dependence as evidenced by higher baseline Fagerström scores. Also, individuals with a history of MDD had higher nicotine withdrawal scores, greater craving scores and higher CO levels during smoking cessation treatment. Those with elevated baseline BDI-II scores smoked more cigarettes per day. In regard to smoking cessation outcomes, higher BDI-II scores were associated with a lesser likelihood of smoking abstinence, higher expired CO scores during treatment, higher nicotine withdrawal scores, and higher nicotine craving scores. These findings are similar to those in samples of smokers who do not have a substance use disorder.

Because there was no diagnosis of MDD, this study used a previous treatment history of MDD reported by the participants as a proxy for history of MDD. While this may be an underestimate of the history of MDD in our study sample, the rates we observed was similar to that seen in other studies.20 Among cigarette smokers, Hall and colleagues14 found 31% of a sample of 149 smoking treatment participants had a history of MDD. Others have reported similar rates.21,22 In this regard it has been suggested that individuals with low tolerance to mood disturbance have a greater propensity for drop out from substance abuse treatment23 and for early relapse to smoking after a quit attempt.24 The findings in the present study are consistent with this, as higher baseline depression scores were associated with lower smoking abstinence rates.

Overall, this report shows an association between depressive measures and smoking outcomes in which higher symptoms of depression are associated with poorer smoking cessation outcomes. Data from previous studies of the general population have been mixed in this regard. Anda and colleagues25 reported a lower rate of smoking cessation during a 9-year follow-up in smokers who scored higher on depressive symptoms at baseline compared with those who scored lower. Salive and Blazer26 reported on the 3-year incidence of quitting among smokers 65 years and older and found women with high baseline depression scores to have a 2-fold increase in quitting smoking (55%) compared to women with normal baseline depression scores (25%). Still other investigators5 have found no influence of depression on smoking cessation outcomes.

Haas and colleagues22 found that individuals with a history of MDD responded better to smoking cessation treatment that included a strong dose of CBT. Moreover, Hall and colleagues14 found that individuals with current depression responded better to smoking cessation treatment with motivational enhancement counseling sessions versus brief advice to quit. The current study also included a strong dose of CBT, and counseling attendance was a significant predictor of abstinence.11 Nevertheless, subjects with higher depression scores showed poorer smoking abstinence outcomes. Perhaps depression co-morbid with, drug or alcohol dependence is simply too strong to overcome.

As stated above, history of MDD or high BDI-ll scores were associated with more smoking (yrs, cig/day) and higher Fagerstrom nicotine dependence scores at baseline in the current study. Breslau and colleagues5 observed depression at baseline increased significantly the risk for daily smoking (OR 3.0) but did not decrease significantly smokers’ rate of quitting (OR 0.8). History of daily smoking at baseline increased significantly the risk for major depression (OR 1.9). Interestingly, this estimate was reduced when early conduct problems and prior alcohol use were controlled. It is unclear what the effect of other substances of abuse might have on this association. Indeed, substance abuse quantity and severity of dependence has been reported to be greater in smokers versus non-smokers,27,28,29 and more smoking is reported in comparisons of substance abusing versus non-abusing patients.30,31 This study also found an association between baseline BDI-II scores and nicotine withdrawal symptoms. The symptom overlap between nicotine withdrawal and depressive symptoms, including insomnia, anxiety, difficulty concentrating, somatic complaints, and changes in appetite may play a part in the strength of this association.

As stated above, depressed mood has often been associated with worse substance abuse treatment outcomes.9,10 Interestingly the current study did not find a significant relationship between mood and substance use during study treatment. This may have been due that fact that this was a secondary analysis and the study was not powered to answer that specific research question. Also, the participants in this trial were enrolled in substance abuse treatment for at least a month prior to study enrollment, which may have allowed for a more stable substance abuse outcome.

This study found substance abusers with either a history of MDD or an elevated BDI-II at baseline to have an earlier onset of cigarette smoking as well as worse smoking cessation outcomes. It remains unclear, however, what effect specific treatment of depressive symptoms might have on smoking cessation outcomes in this sample. In the current study, there was no difference in BDI scores during, and at the end of treatment, between SC treatment and control groups. Hall and colleagues32 conducted a 2 (nortriptyline versus placebo) ×2 (cognitive-behavioral therapy versus a health education control) × 2 (history of MDD versus no MDD history) randomized trial in 199 treatment-seeking smokers. They found that nortriptyline improved dysphoric symptoms that occurred after smoking cessation and that it improved abstinence rates greater than placebo, independent of MDD history. Brown and colleagues33 reported similar findings with bupropion and cognitive behavioral therapy. It is unclear if either of these antidepressant pharmacotherapies would have a differential effect in depressed substance abusers interested in quitting smoking.

Limitations

Several issues limit the utility and generalizability of these data. Because this paper is a secondary analysis of the primary outcome, the protocol was not designed specifically to answer the questions posed in this report. Psychiatric diagnoses were made by clinical history, not with a structured diagnostic assessment. Specifically, presence or absence of depression was based on participant self-report of the question “Have you ever been treated for depression?” It is likely that some study participants may have had MDD but never received treatment or did not recall receiving treatment and thus, would have been grouped incorrectly. While this is likely to underestimate the history of MDD in our study sample, the rates observed in the current paper were similar to other studies. There were too few participants who actually quit smoking to have adequately powered analyses comparing mood variables by treatment success (quitting) vs. non-success. Also, the majority of participants in this study were enrolled in methadone maintenance programs, and thus this report may not be generalizable to individuals in ‘drug-free’ programs who would like to quit smoking.

Conclusions

This report found an association between depression measures and smoking cessation outcomes. There was a fairly consistent association between presence of depression, or a history of depression, and greater smoking severity and poorer smoking outcomes. Specifically, participants with a history of MDD reported an earlier age of cigarette smoking, greater dependence on nicotine, higher nicotine withdrawal scores, greater craving scores and higher CO levels during smoking cessation treatment. Those with elevated baseline BDI-II scores also reported a greater dependence on nicotine and smoked more cigarettes per day than those with lower BDI-II scores.. In regard to smoking cessation outcomes, higher BDI-II scores were associated with a lesser likelihood of smoking abstinence, higher expired CO scores higher nicotine withdrawal scores, and higher nicotine craving scores during treatment. Current depressive symptom severity was more strongly associated with negative smoking outcomes than was history of depression. This difference in association may be due to the way history of depression was defined. These data suggest that for individuals with substance dependence who are interested in quitting smoking, evaluation and treatment of depressive symptoms may play an important role in improving smoking cessation outcomes. Given that baseline depressive symptoms had a negative impact on smoking cessation outcomes, providing interventions to improve mood (either behavior interventions or antidepressant medications) prior to smoking cessation intervention may improve outcomes.

References

- 1.Glassman AH, Helzer JE, Covey LS, et al. Smoking, smoking cessation, and major depression.[see comment] JAMA. 1990;264:1546–1549. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Breslau N, Kilbey MM, Andreski P. Nicotine dependence, major depression, and anxiety in young adults. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1991;48:1069–1074. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1991.01810360033005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hughes J, Hatsukami D. Signs and symptoms of tobacco withdrawal. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1986;43:289–294. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1986.01800030107013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Glassman AH, Covey LS, Dalack GW, et al. Smoking cessation, clonidine, and vulnerability to nicotine among dependent smokers. Clinical Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 1993;54:670–679. doi: 10.1038/clpt.1993.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Breslau N, Peterson EL, Schultz LR, Chilcoat HD, Andreski P. Major depression and stages of smoking. A longitudinal investigation. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1998;55:161–166. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.55.2.161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Klerman GL, Leon AC, Wickramaratne P, et al. The role of drug and alcohol abuse in recent increases in depression in the US. Psychological Medicine. 1996;26:343–351. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700034735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Troisi A, Pasini A, Saracco M, Spalletta G. Psychiatric symptoms in male cannabis users not using other illicit drugs. Addiction. 1998;93:487–492. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1998.9344874.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nunes EV, Rounsaville BJ. Comorbidity of substance use with depression and other mental disorders: from Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fourth edition (DSM-IV) to DSM-V. Addiction. 2006;101 Suppl 1:89–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01585.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nunes EV, Levin FR. Treatment of depression in patients with alcohol or other drug dependence: a meta-analysis.[see comment] JAMA. 2004;291:1887–1896. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.15.1887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Levin FR, Bisaga A, Raby W, et al. Effects of major depressive disorder and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder on the outcome of treatment for cocaine dependence. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2008;34:80–89. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2006.11.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Reid M, Fallon B, Sonne S, et al. Smoking cessation treatment at community based substance abuse rehabilitation programs. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2007 doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2007.08.010. In Press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.APA. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Munoz R, Organista K, Hall SH. Mood Management Training to Prevent Smoking Relapse: A Cognitive Behavioral Treatment Manual Department of Psychiatry. San Francisco: University of California; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hall SH, Munoz R, Reus V. Cognitive-behavioral intervention increases abstinence rates for depressive-history smokers. J Consult Clin Psychology. 1994;62:141–146. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.62.1.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Beck A, Steer R, Ball R, Ranieri WF. Comparison of Beck Depression Inventories-IA and -II in psychiatric outpatients. Journal of Personality Assessment. 1996;67:588–597. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa6703_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Heatherton T, Kozlowski L, Freckler R, Fagerström K. The Fagerstrom Test for Nicotine Dependence: A revision of the Fagerström Tolerance Questionnaire. Brit J Addiction. 1991;86:1119–1127. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1991.tb01879.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hughes J, Gust S, Skoog K, Keenan R, Fenwick J. Symptoms of tobacco withdrawal: A replication and extension. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1991;48:52–59. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1991.01810250054007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Beck AT, Steer RA, Ball R, Ranieri W. Comparison of Beck Depression Inventories -IA and -II in psychiatric outpatients. Journal of Personality Assessment. 1996;67:588–597. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa6703_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.SAS/STAT User's Guide. Version 6. 4th ed. Cary, NC: SAS Institute Inc.; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 20.McGovern M, Xie H, Segal S, Siembab L, Drake R. Addiction treatment services and co-occurring disorders: Prevalence estimates, treatment practices, and barriers. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2006;31:267–275. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2006.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ginsberg D, Hall SM, Reus V, Munoz RF. Mood and depression diagnosis in smoking cessation. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 1995;3:389–395. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Haas AL, Munoz RF, Humfleet GL, Reus VI, Hall SM. Influences of mood, depression history, and treatment modality on outcomes in smoking cessation. Journal of Consulting & Clinical Psychology. 2004;72:563–570. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.4.563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Daughters SB, Lejuez CW, Bornovalova MA, Kahler CW, Strong DR, Brown RA. Distress tolerance as a predictor of early treatment dropout in a residential substance abuse treatment facility. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2005;114:729–734. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.114.4.729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brown RA, Lejuez CW, Kahler CW, Strong DR, Zvolensky M. Distress tolerance as a predictor of early treatment dropout in a residential substance abuse treatment facility. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2005;114:729–734. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.114.4.729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Anda R, Williamson D, Escobedo L, Mast E, Giovino G, Remington P. Depression and the dynamics of smoking. Journal of the Americal Medical Association. 1990;264:1541–1545. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Salive ME, Blazer DG. Depression and smoking cessation in older adults: a longitudinal study. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 1993;41:1313–1316. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1993.tb06481.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Budney A, Higgins S, Hughes J, Bickel W. Nicotine and caffeine use in cocaine-dependent individuals. J Substance Abuse. 1993;5:117–130. doi: 10.1016/0899-3289(93)90056-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Toneatto A, Sobell LC, Sobell MB, Kozlowski LT. Effect of cigarette smoking on alcohol treatment outcome. Journal of Substance Abuse. 1995;7:245–252. doi: 10.1016/0899-3289(95)90008-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stark MJ, Campbell BK. Drug use and cigarette smoking in applicants for drug abuse treatment. Journal of Substance Abuse. 1993;5:175–181. doi: 10.1016/0899-3289(93)90060-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Burling TA, Ramsey TG, Seidner AL, Kondo CS. Issues related to smoking cessation among substance abusers. Journal of Substance Abuse. 1997;9:27–40. doi: 10.1016/s0899-3289(97)90004-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Miller NS, Gold MS. Comorbid cigarette and alcohol addiction: epidemiology and treatment. Journal of Addictive Diseases. 1998;17:55–66. doi: 10.1300/J069v17n01_06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hall SM, Reus VI, Munoz RF, et al. Nortriptyline and cognitive-behavioral therapy in the treatment of cigarette smoking.[see comment] Archives of General Psychiatry. 1998;55:683–690. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.55.8.683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Brown R, Niaura R, Lloyd-Richardson E, et al. Bupropion and cognitive-behavioral treatment for depression in smoking cessation. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2007;9:721–730. doi: 10.1080/14622200701416955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]