Abstract

It is known that early childhood wheezing associated with sensitization to allergens, including food, has an increased risk of developing asthma later during school age. Gastroesophageal reflux (GER) is well known to be associated with asthma. The purpose of this study was to determine whether there is an association between silent GER and food sensitization in infants and young children with recurrent wheezing. Eighty-five infants or young children with recurrent wheezing, and no gastrointestinal symptoms, underwent 24 hr esophageal pH monitoring, as well as total serum IgE and specific IgE testing for eggs and milk. Among the 85 subjects, 48.2% had significant GER. There was no significant difference in the GER between atopic and non-atopic recurrent wheezers (41.7% and 50.8%, respectively). The sensitization rate to food (eggs or milk) was 12.2% and 20.5% in the GER and non-GER groups, respectively and showed no statistically significant difference between the two groups (P=0.34). In conclusion, about half of infants and young children with recurrent wheezing and no gastrointestinal symptoms have silent GER. The silent GER may not contribute to food sensitization in infants and young children with recurrent wheezing.

Keywords: Recurrent Wheezer, Infant, Gastroesophageal Reflux, Food Antigen Sensitization

INTRODUCTION

It is difficult to predict the phenotypes of wheezing that develop later in childhood among infants with recurrent wheezing. Among infants and young children with recurrent wheezing, 30-50% will go on to develop persistent asthma later in childhood (1, 2). Since remodeling of the airways may occur during early stages of asthma (3), it is important to identify and properly manage patients with asthma early in life. Because sensitization to aeroallergen is rare, food sensitization before two years of age, which was defined as a minor criteria for asthma predictive index (4), was an important predictor of the development of asthma for children followed until school age (5).

It has been reported that the frequency of gastroesophageal reflux (GER) in asthmatic children ranges between 59 and 75% (6-8). It has been suggested that infants that have GER should be evaluated for allergy to cow's milk (9). One study reported that GER was linked to food induced wheezing and food sensitization (10). However, other investigators have reported a higher frequency of GER in subjects with nonatopic asthma compared to those with atopic asthma (11, 12). Thus, when an infant with recurrent wheezing has GER symptoms, it is necessary to evaluate that infant for food allergy as a possible cause of the wheezing. However, gastroesophageal reflux has been reported to be associated with asthma in the absence of reflux symptoms (13). There is limited information on the frequency of GER without gastrointestinal reflux symptoms, so-called silent GER, in infants with recurrent wheezing. The relationship between silent GER and atopic or non-atopic asthma has not been determined. Furthermore, if there is an association between silent GER and food allergy sensitization in infants with recurrent wheezing, this may have important implications for the development of asthma later in life.

Therefore, the aim of this study was to determine the frequency of silent GER and the relationship between silent GER and food sensitization in infants and young children with recurrent wheezing.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subjects and study design

Eighty five infants and young children from 4 to 24 months of age with wheezing on more than three occasions or with persistent wheezing lasting more than 3 weeks and no gastrointestinal symptoms such as repeated regurgitation or vomiting, underwent 24-hr esophageal pH monitoring. There were no subjects known to have cow's milk or egg allergies. There were no subjects on an elimination diet. The study was carried out during the period between August 2003 and July 2004.

We excluded patients that had chronic lung disease, central nervous system disorders such as cerebral palsy, or congenital anomalies of heart or airways. We also excluded patients that had evidence of an infection such as an increased C-reactive protein (CRP), presented with fever, and/or infiltrations on chest radiographs. Infants that were exclusively breast fed were also not included in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the parents of all patients.

Total serum immunoglobulin E (Phadebas IgE PRIST; Pharmacia, Uppsala, Sweden) and specific IgE to egg whites (F1), milk (F2), and house dust mites (UniCAP®, Pharmacia Diagnostics, Uppsala, Sweden) were determined in all subjects. Sensitization to a specific allergen was defined as a concentration of 0.7 kU/L or greater with the respective specific IgE. The presence of atopy was defined by elevated IgE values, higher than 30, 60, and 100 kU/L in infants less than 6 months of age, from 6 to 12 months, and from 1 to 2 yr, respectively, and/or sensitization to any food or house dust mite allergens.

24-hr esophageal pH monitoring and definition of GER

The patients underwent 24-hr lower esophageal pH monitoring for more than 18 hr. Medications that might have affected gastric acidity or esophageal motility were discontinued for at least 72 hr before the study, as well as during the study period. Asthma medications except for theophylline were continued as usual during the monitoring. Esophageal pH monitoring was conducted once an acute attack of wheezing had resolved. The Synetics ambulatory system with antimony pH electrodes (Synetics Medical AB, Stockholm, Sweden) was used. The intraesophageal pH electrode was positioned one-eighth the distance above the calculated distance of the nares to the lower esophageal sphincter, using Strobel's equation according to patient height. The position of the catheter was verified by chest radiography to be 2 cm above the diaphragm. An external reference electrode was placed on the patient's anterior chest wall (14). Measurements of pH were recorded using a pH recorder (Digitrapper MK 3, Synetics Medical AB, Stockholm, Sweden).

The diagnosis of reflux was based on the reflux index, which was the ratio of time under pH 4 to the total measurement time (14). Gastroesophageal reflux was defined as more than 10% of the reflux index for infants under 12 months of age and more than 6% in children more than 12 months of age (15). Reflux was considered silent when subjects did not have gastrointestinal symptoms.

Statistical analyses

We classified the patients into silent reflux and non-reflux groups according to the results of the 24-hr lower esophageal pH monitoring. A Student's t-test was used for statistical analysis of the calculated log average and of the standard deviation of serum IgE between the two groups. The chi-square test was used for descriptive analysis of the differences in sensitization between the two groups. A P value less than 0.05 was accepted as statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences, SPSS 11.5 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

RESULTS

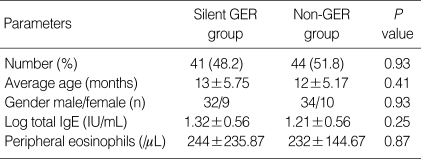

Among the 85 infants, 41 (48.2%) had positive pH monitoring results. Thirty-two were males (77.7%) and nine were females (22.4%). The log serum total IgE was 1.32±0.56 IU/mL in the silent GER group and 1.21±0.56 IU/mL in the non-GER group. There was no statistically significant difference between the two groups in the level of serum total IgE (P=0.25, Table 1). The frequency of silent GER was 41.7% and 50.8% in the atopic and non-atopic subjects, respectively. There was no significant difference in the incidence of GER between the atopic and non-atopic wheezers (P=0.45).

Table 1.

Characteristics of subjects with silent GER and without GER

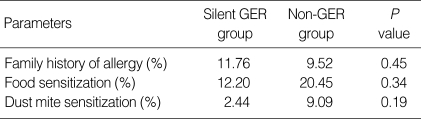

In the silent GER group, five children were sensitized to milk and/or egg whites (12.2%). In the non-GER group, nine children (20.5%) showed sensitization to milk and/or egg whites. There was no significant difference between the two groups in the frequency of positive IgE antibodies to at least one of the two food allergens (P=0.34, Table 2).

Table 2.

Allergen sensitization in subjects with silent GER and without GER

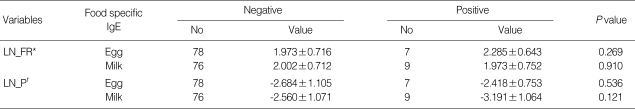

Because the frequency of reflux has a right skewed distribution, the data was transformed to a logarithmic scale and each transformed data was added 1 to be a larger than 0 (LN_FR=ln[frequency of reflux+1]). There was no difference of the LN_FR between subjects who were sensitized to egg white and those who were not sensitized (P=0.269) nor subjects that were sensitized to milk and those who were not (P=0.910). A log-transformation of the percent time was performed since the distribution of the percent time of reflux was skewed (LN_P=In[percent time]). There was no difference of the LN_P between subjects who were sensitized to egg white and those who were not sensitized (P=0.536) nor subjects who were sensitized to milk and those who were not (P=0.121, Table 3).

Table 3.

Comparison of GER parameters between group with positive food specific IgE and those with negative

Data are presented as the mean±SD.

*ln[Frequency of Reflux+1], log transformed data of the frequency of reflux; †ln[Percent Time], log transformed data of the percent time.

After exclusion of F1 or F2 lower than 0.35 kU/L, the relation between the LN_FR or the LN_P and the value of F1 or F2 was evaluated by the general linear model. There was no relation between the LN_FR and the value of F1 (P=0.250) nor F2 (P=0.230). There was no relation between the LN_P and the value of F1 (P=0.836) nor F2 (P=0.089).

DISCUSSION

The purpose of this study was to determine whether the frequency of silent GER was higher and whether there was an association between silent GER and food allergen sensitization in infants and young children with recurrent wheezing. There is limited information available on the frequency of silent GER in atopic and non-atopic asthma, although it is widely accepted that GER is linked to asthma. Prior research has found a higher frequency of GER in subjects with nonatopic asthma compared to atopic asthma (12). However, other reports showed that the prevalence of esophageal dysfunction was higher in atopic asthma compared to non-atopic asthma (16). The frequency of silent GER in the present study was 48%, which was higher than the 28% in infants with daily wheezing (17) and the 21% in Korean children less than 3 yr of age with recurrent wheezing (18) previously reported.

The frequency of GER varies according to the subject's condition. Since active coughing or wheezing itself can cause GER, esophageal pH monitoring was performed after the wheezing improved in this study. The results of this study showed that the frequency of GER in atopic and non-atopic wheezers was 41.7% and 50.8%, respectively. There was no significant difference between the atopic and non-atopic wheezers. These findings are in contrast to the results of a previous study (12) that showed a higher frequency of a family history of asthma in infants without GER than in those with GER, suggesting more frequent GER in non-atopic wheezers.

Although asthma can develop at any age, most children have their first episode of wheezing before 3 yr of age (19). Childhood wheezing is classified into three different phenotypes: transient wheezer, atopic wheezer and non-atopic wheezer (20). Thus, a better sub-classification might lead to a better understanding and treatment of young children with recurrent wheezing. Airway remodeling has been demonstrated not only in children with difficult asthma but also in those with early onset of asthma (3). It has been reported that about one half to one third of infants and children with early-childhood wheezing develop persistent asthma later in childhood (1, 2). Thus, it is important to make an early diagnosis and provide the proper treatment to infants and young children with wheezing for the prevention of airway remodeling.

Food sensitization before age two has been reported to be a predictive factor for the development of atopic asthma (5). However, little is known about the relationship between the development of asthma and food sensitization. The prevalent food antigens causing sensitization in infants and young children are eggs and cow's milk. One study showed loss of milk antigen sensitization and relief of asthma symptoms in a patient who had milk allergy and severe gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) after undergoing fundoplication (10), suggesting an association between food sensitization and GERD with asthma.

Although the relationship between food allergy and GERD has been confirmed, there are few studies on the association between silent GER and food sensitization in infants with recurrent wheezing without food allergy. If there is an association between silent GER and food sensitization in asthmatic infants and young children, the presence of silent GER might contribute to early food sensitization and, furthermore, the development of atopic asthma later in childhood. However, the results of the present study showed that the rate of food sensitization was not significantly different between the two study groups. In the silent GER group, 12.2% of patients had food sensitization, and in the non-GER group, 20.5% had food sensitization. In addition, comparison of the GER parameters, like frequency of reflux and % time of reflux in infants and young children with recurrent wheezing revealed that there were no difference between GER parameters of subjects who had positive specific IgE to food and those negative.

This study has several limitations. These include the one time evaluation, absence of data on other potential food allergies such as soy, fish, and peanuts, and the small sample size.

In summary, the frequency of silent GER in infants and young children with recurrent wheezing was about 50%. There was no difference between the rate of food sensitization of the subjects with silent GER and those with non-GER. In addition, there was no difference with GER parameters between subjects who had positive specific IgE to food and those negative. Therefore, the presence of silent GER may not contribute to food sensitization in infants and young children with recurrent wheezing.

Footnotes

This work was supported by INHA University Research Grant.

References

- 1.Martinez FD, Wright AL, Taussig LM, Holberg CJ, Halonen M, Morgan WJ. Asthma and wheezing in the first six years of life. N Engl J Med. 1995;332:133–138. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199501193320301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wennergren G, Amark M, Amark K, Oskarsdóttir S, Sten G, Redfors S. Wheezing bronchitis reinvestigated at the age of 10 years. Acta Paediatr. 1997;86:351–355. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1997.tb09021.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Payne DN, Rogers AV, Adelroth E, Bandi V, Guntupalli KK, Bush A, Jeffery PK. Early thickening of the reticular basement membrane in children with difficult asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003;167:78–82. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200205-414OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Guilbert TW, Morgan WJ, Krawiec M, Lemanske RF, Sorkness C, Szefler SJ, Larsen G, Spahn JD, Zeiger RS, Heldt G, Strunk RC, Bacharier LB, Bloomberg GR, Chinchilli VM, Boehmer SJ, Mauger EA, Mauger DT, Taussig LM, Martinez FD. The prevention of early asthma in kids study: design, rationale and methods for the childhood asthma research and education network. Control Clin Trials. 2004;25:286–310. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2004.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Illi S, von Mutius E, Lau S, Nickel R, Niggemann B, Sommerfeld C, Wahn U Multicenter Allergy Study Group. The pattern of atopic sensitization is associated with the development of asthma in childhood. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2001;108:709–714. doi: 10.1067/mai.2001.118786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ay M, Sivasli E, Bayraktaroglu Z, Ceylan H, Coskun Y. Association of asthma with gastroesophageal reflux disease in children. J Chin Med Assoc. 2004;67:63–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cinquetti M, Micelli S, Voltolina C, Zoppi G. The pattern of gastroesophageal reflux in asthmatic children. J Asthma. 2002;39:135–142. doi: 10.1081/jas-120002194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Khoshoo V, Le T, Haydel RM, Jr, Landry L, Nelson C. Role of gastroesophageal reflux in older children with persistent asthma. Chest. 2003;123:1008–1013. doi: 10.1378/chest.123.4.1008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Salvatore S, Vandenplas Y. Gastroesophageal reflux and cow milk allergy: is there a link? Pediatrics. 2002;110:972–984. doi: 10.1542/peds.110.5.972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Meer S, Groothuis JR, Harbeck R, Liu S, Leung DY. The potential role of gastroesophageal reflux in the pathogenesis of food-induced wheezing. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 1996;7:167–170. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3038.1996.tb00127.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kiljander TO, Salomaa ER, Hietanen EK, Terho EO. Gastroesophageal reflux in asthmatics: a double-blind, placebo-controlled crossover study with omeprazole. Chest. 1999;116:1257–1264. doi: 10.1378/chest.116.5.1257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yüksel H, Yilmaz O, Kirmaz C, Aydoğdu S, Kasirga E. Frequency of gastroesophageal reflux disease in nonatopic children with asthma-like airway disease. Respir Med. 2006;100:393–398. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2005.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harding SM, Guzzo MR, Richter JE. The prevalence of gastroesophageal reflux in asthma patients without reflux symptoms. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;162:34–39. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.162.1.9907072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vandenplas Y, Goyvaerts H, Helven R, Sacre L. Gastroesophageal reflux, as measured by 24-hour pH monitoring, in 509 healthy infants screened for risk of sudden infant death syndrome. Pediatrics. 1991;88:834–840. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jain A, Patwari AK, Bajaj P, Kashyap R, Anand VK. Association of gastroesophageal reflux disease in young children with persistent respiratory symptoms. J Trop Pediatr. 2002;48:39–42. doi: 10.1093/tropej/48.1.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kjellén G, Brundin A, Tibbling L, Wranne B. Oesophageal function in asthmatics. Eur J Respir Dis. 1981;62:87–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sheikh S, Stephen T, Howell L, Eid N. Gastroesophageal reflux in infants with wheezing. Pediatr Pulmonol. 1999;28:181–186. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-0496(199909)28:3<181::aid-ppul4>3.0.co;2-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hong CS, Shim JY, Kim BS, Park KY, Kim KM. Prevalence of gastroesophageal reflux in infants with recurrent wheezing. J Asthma Allergy Clin Immunol. 1999;19:576–583. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Koh MS, Irving LB. The natural history of asthma from childhood to adulthood. Int J Clin Pract. 2007;61:1371–1374. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2007.01426.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Taussig LM, Wright AL, Holberg CJ, Halonen M, Morgan WJ, Martinez FD. Tucson Children's Respiratory Study: 1980 to present. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2003;111:661–675. doi: 10.1067/mai.2003.162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]