Abstract

The intravenous administration of gadopentetate dimeglumine (GD) is relatively safe and rarely causes systemic toxicity in the course of routine imaging studies. However, the general safety of intrathecal GD has not been established. We report a very rare case of an overdose intrathecal GD injection presenting with neurotoxic manifestations, including a decreased level of consciousness, global aphasia, rigidity, and visual disturbance.

Keywords: Neurologic Manifestations; Injections, Spinal; Gadolinium DTPA

INTRODUCTION

Gadopentetate dimeglumine (GD: gadolinium complexed with diethylenetriamine pentaacetic acid [DTPA]) is a magnetic resonance (MR) imaging contrast agent in wide clinical use. The intravenous administration of GD is relatively safe and rarely causes systemic toxicity in the course of routine imaging studies (1). Although one study (2) demonstrated the safety and feasibility of` low-dose intrathecal GD for evaluating obstructions and communications of the various subarachnoid spaces, spontaneous or traumatic/postsurgical cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leaks, subarachnoid space CSF flow, and parenchymal central nervous system (CNS) interstitial diffusion dynamics, the general safety of intrathecal GD has not been established. Moreover, cases of high-dose intrathecal GD administration to humans have rarely been reported. We report the case of an overdose intrathecal GD injection presenting with neurotoxic manifestations, including a decreased level of consciousness, global aphasia, rigidity, and visual disturbance.

CASE REPORT

A 42-yr-old male was admitted to our neurosurgical intensive care unit from an outside hospital after the accidental intrathecal injection of 6 mL of a GD contrast medium (Magnevist®, Bayer HealthCare Pharmaceuticals, Wayne, NJ, USA), instead of an iodine-containing contrast medium (Omnipaque®, GE Healthcare, Ireland) during computed tomographic myelography. The patient had a history of lumbar fusion surgery for spinal canal stenosis and complained of recurrent right buttock and leg pain that started 1 month before this incident. The doctor at the outside hospital decided to evaluate the patient's symptoms with computed tomographic myelography. However, the pharmacy accidentally delivered a GD contrast medium to the doctor, and this medium was given to the patient intrathecally. Six hours after the injection, the patient became confused, with global aphasia and vomiting. Brain computed tomography (CT) images of the patient revealed diffuse high density throughout the subarachnoid space.

When the patient was transferred to our hospital, his condition had worsened. He was stuporous, with severe rigidity and intermittent seizures. He had a blood pressure of 180/90 mmHg, and his body temperature was 40.0℃. During the neurological examination, he showed global aphasia, severe rigidity, jerking movements of the left extremities, and neck stiffness. Babinski's sign and ankle clonus were not noted. Routine laboratory parameters showed no relevant abnormalities. Brain CT about 10 hr after administering the GD also showed diffuse high density throughout the subarachnoid space (Fig. 1). Conventional digital subtraction angiography, which was performed to rule out a spontaneous subarachnoid hemorrhage, revealed no definite abnormality (Fig. 2). Over the following 4 days, the patient gradually became alert. There were no seizures with anticonvulsants. On day 4 after admission, brain CT showed no abnormal findings (Fig. 3). The global aphasia and rigidity had also disappeared, and no additional focal neurological deficits were observed, except for the visual disturbances, which persisted until day 7. On day 15, he was discharged home with no specific symptoms or complaints.

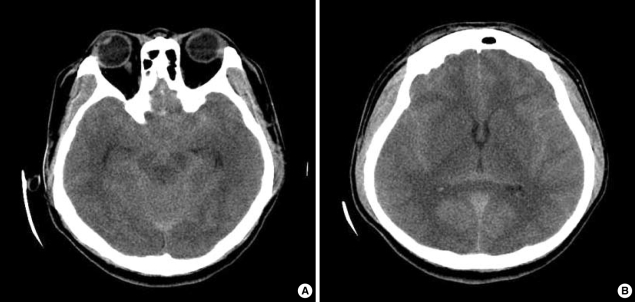

Fig. 1.

Brain CT images about 10 hr after the administration of GD showing diffuse high density throughout the subarachnoid space. (A) At the level of basal cisterns and (B) sylvian fissure.

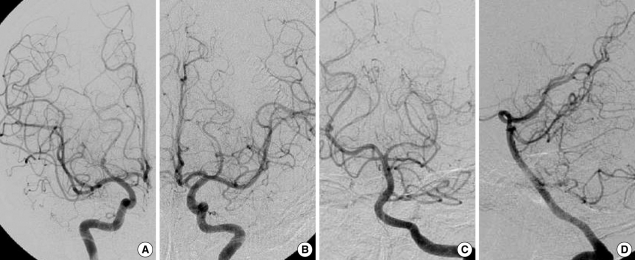

Fig. 2.

Conventional digital subtraction angiographies showing no definite vascular abnormality. (A) Right internal carotid artery (ICA), anteroposterior (AP) view. (B) Left ICA, AP view. (C, D) Left vertebral artery, AP (C) and lateral (D) view.

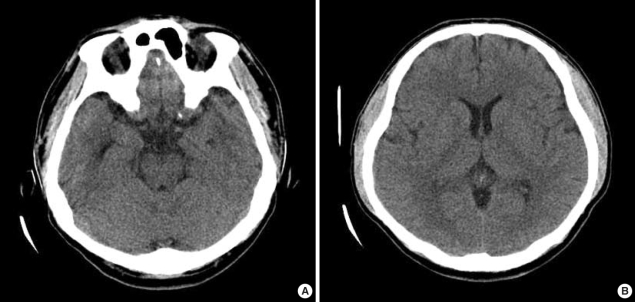

Fig. 3.

Follow-up brain CT images on day 4 after admission. The diffuse high density throughout the subarachnoid space had disappeared. (A) At the level of basal cisterns and (B) sylvian fissure.

At a follow-up visit 1 month after discharge, he complained of recurrent visual disturbances. The ophthalmologic examination revealed bilateral optic atrophy that did not improve until the 1-yr follow-up.

DISCUSSION

GD is an MR imaging contrast agent in wide clinical use. The intravenous application of GD is relatively safe and rarely causes systemic toxicity in the course of routine imaging studies (1). Preclinical studies and extensive clinical trials have established its safety and tolerance when injected via the intravenous route for MR imaging enhancement studies. Reports have revealed some potentially adverse systemic effects, although the incidence of these side effects is low (2, 3). Nausea or vomiting and headache are the most common side effects, with frequencies ranging from 0.26 to 0.42% (2, 4). Other rare reactions reported after the intravenous administration of gadolinium products include paresthesias, dizziness, focal convulsions, urticaria, mucosal reactions, generalised flushing, cardiovascular reactions (e.g., tachycardia, arrhythmia), generalised seizures, laryngospasm, and anaphylactic shock (2, 3).

Recently, the intrathecal administration of GD has attracted medical attention due to the possible applications of intrathecal gadolinium-enhanced MR myelography/cisternography. The possible practical uses of MR imaging include assessing communication with or obstruction of the CSF pathways (e.g., arachnoid cysts and neoplastic subarachnoid space pathway stenosis/obliteration), the evaluation of CSF flow dynamics in the subarachnoid space (e.g., communicating normal-pressure hydrocephalus, postinflammatory craniospinal arachnoid adhesions and loculations), the investigation of spontaneous or acquired craniospinal CSF fistulae, and possibly the analysis of CNS parenchymal extracellular space gadolinium diffusion dynamics in various pathological conditions (e.g., hydrocephalus, encephalomalacia, dementia, cerebral ischemia, and cerebral neoplasia) (2, 5).

Di Chiro et al. (6) performed the first animal experiment involving the injection of gadolinium into the subarachnoid space in 1985. The adverse effects of intraventricular gadolinium injection in animal models included behavioural, neurological (focal seizure activity, ataxia, and delayed tremor), and histopathological (oligodendroglia loss, astrocyte hypertrophy, and eosinophilic granule formation) changes (7, 8). However, these pathological changes were seen only following the intraventricular injection of relatively high doses of gadolinium; no such behavioural or morphological changes were reported in the same studies when the total dose of intraventricular gadolinium was less than 15 µL (3.3 µM/g brain) (7).

Some studies have described the safety of the intrathecal application of GD for MR myelography or cisternography (2, 5, 9). In these studies, doses of 0.5-1.0 mL Magnevist® (0.25-0.5 mM GD) were administered into the subarachnoid space and were reported to be well tolerated with minor adverse effects (e.g., headache) and only rare severe, but transient, complications like hemiparesis and gait disturbance (9).

In our case, the dosage was 6-12 times higher than in those studies (2, 5, 9), probably explaining the more severe and prolonged neurotoxic manifestations including bilateral optic atrophy. In two published cases, the high-dose administration of GD produced a fluctuating level of consciousness and neurological deficits (1, 10). In one case, the total gadolinium dose administered intravenously over 7 days was 60-80 mL (1). In the other case, 20 mL of GD were injected via the intrathecal route by accident (10). They resulted in a sequence of events that led to an encephalopathy, and suggested a novel pathological entity: gadolinium encephalopathy (1, 10).

In the recent case report, Li et al. (11) supposed that there is no CSF-brain barrier with regard to GD, as diffusion of the GD into the cerebral gray matter was evident on the T1-weighted and FLAIR images. This is consistent with previous findings in an animal study (7). Interestingly, GD can also penetrate into the cerebral deep white matter through the perivascular spaces (11). This provides evidence in vivo to support the idea that the perivascular space is a channel for CSF-brain exchanges.

We performed the conservative managements for this patient: intravenous hydration, anticonvulsant for seizures and general supportive care. Li et al. (11) suggested that a prompt continuous CSF draining through a catheter placed into the lumbar cisterna could be a life-saving procedure. Glucosteroid (methylprednisolone) has been used widely in patients with closed-head injuries or brain tumors to prevent and help reverse brain edema (11). The use of methylprednisolone also could be helpful in our patient regaining consciousness after the intrathecal GD injection.

In conclusion, we report a very rare case of an overdose intrathecal GD injection presenting with neurotoxic manifestations, including a decreased level of consciousness, global aphasia, rigidity, and visual disturbance. Although the major limitation of our report is the lack of serial serum and CSF gadolinium levels, future studies could analyze these indices and reference levels in human patients to see if the neurological complications correlate with the gadolinium levels.

References

- 1.Maramattom BV, Manno EM, Wijdicks EF, Lindell EP. Gadolinium encephalopathy in a patient with renal failure. Neurology. 2005;64:1276–1278. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000156805.45547.6E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tali ET, Ercan N, Krumina G, Rudwan M, Mironov A, Zeng QY, Jinkins JR. Intrathecal gadolinium (gadopentetate dimeglumine) enhanced magnetic resonance myelography and cisternography: results of a multicenter study. Invest Radiol. 2002;37:152–159. doi: 10.1097/00004424-200203000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Niendorf HP, Haustein J, Cornelius I, Alhassan A, Clauss W. Safety of gadolinium-DTPA: extended clinical experience. Magn Reson Med. 1991;22:222–228. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910220212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goldstein HA, Kashanian FK, Blumetti RF, Holyoak WL, Hugo FP, Blumenfield DM. Safety assessment of gadopentetate dimeglumine in U.S. clinical trials. Radiology. 1990;174:17–23. doi: 10.1148/radiology.174.1.2403679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zeng Q, Xiong L, Jinkins JR, Fan Z, Liu Z. Intrathecal gadolinium-enhanced MR myelography and cisternography: a pilot study in human patients. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1999;173:1109–1115. doi: 10.2214/ajr.173.4.10511188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Di Chiro G, Knop RH, Girton ME, Dwyer AJ, Doppman JL, Patronas NJ, Gansow OA, Brechbiel MW, Brooks RA. MR cisternography and myelography with Gd-DTPA in monkeys. Radiology. 1985;157:373–377. doi: 10.1148/radiology.157.2.4048444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ray DE, Cavanagh JB, Nolan CC, Williams SC. Neurotoxic effects of gadopentetate dimeglumine: behavioral disturbance and morphology after intracerebroventricular injection in rats. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1996;17:365–373. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ray DE, Holton JL, Nolan CC, Cavanagh JB, Harpur ES. Neurotoxic potential of gadodiamide after injection into the lateral cerebral ventricle of rats. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1998;19:1455–1462. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tali ET, Ercan N, Kaymaz M, Pasaoglu A, Jinkins JR. Intrathecal gadolinium (gadopentetate dimeglumine)-enhanced MR cisternography used to determine potential communication between the cerebrospinal fluid pathways and intracranial arachnoid cysts. Neuroradiology. 2004;46:744–754. doi: 10.1007/s00234-004-1240-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Arlt S, Cepek L, Rustenbeck HH, Prange H, Reimers CD. Gadolinium encephalopathy due to accidental intrathecal administration of gadopentetate dimeglumine. J Neurol. 2007;254:810–812. doi: 10.1007/s00415-006-0439-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li L, Gao FQ, Zhang B, Luo BN, Yang ZY, Zhao J. Overdosage of intrathecal gadolinium and neurological response. Clin Radiol. 2008;3:1063–1068. doi: 10.1016/j.crad.2008.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]