Abstract

Tumor-infiltrating myeloid cells (TIMs) support tumor growth by promoting angiogenesis and suppressing antitumor immune responses. CSF-1 receptor (CSF1R) signaling is important for the recruitment of CD11b+F4/80+ tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) and contributes to myeloid cell-mediated angiogenesis. However, the impact of the CSF1R signaling pathway on other TIM subsets, including CD11b+Gr-1+ myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs), is unknown. Tumor-infiltrating MDSCs have also been shown to contribute to tumor angiogenesis and have recently been implicated in tumor resistance to antiangiogenic therapy, yet their precise involvement in these processes is not well understood. Here, we use the selective pharmacologic inhibitor of CSF1R signaling, GW2580, to demonstrate that CSF-1 regulates the tumor recruitment of CD11b+Gr-1loLy6Chi mononuclear MDSCs. Targeting these TIM subsets inhibits tumor angiogenesis associated with reduced expression of proangiogenic and immunosuppressive genes. Combination therapy using GW2580 with an anti–VEGFR-2 antibody synergistically suppresses tumor growth and severely impairs tumor angiogenesis along with reverting at least one TIM-mediated antiangiogenic compensatory mechanism involving MMP-9. These data highlight the importance of CSF1R signaling in the recruitment and function of distinct TIM subsets, including MDSCs, and validate the benefits of targeting CSF1R signaling in combination with antiangiogenic drugs for the treatment of solid cancers.

Introduction

Solid tumors contain a significant population of infiltrating myeloid cells that support tumor progression by promoting angiogenesis and suppressing antitumor immune responses. Clinical data and experimental studies have established the pro-tumorigenic potential of tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs).1,2 TAMs are typically characterized as either “classically” activated tumoricidal macrophages (termed M1) or “alternatively” activated pro-tumorigenic macrophages (termed M2).3 Recently, infiltrating myeloid cells have been further classified by their surface marker expression profiles into distinct subsets of tumor-infiltrating myeloid cells (TIMs), including the aforementioned TAMs, along with neutrophils, CD11b+Gr-1loLy6Chi mononuclear and CD11b+Gr-1hiLy6Clo polymorphonuclear myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MO-MDSCs and PMN-MDSCs, respectively) with diverse functions within the tumor and in other tissues.4–7 A more detailed characterization of these TIMs will be important for understanding their relevance in tumor progression and for developing novel anticancer therapies.

The mechanisms underlying the recruitment and function of TIMs have been an area of intense research. Several cytokines and chemokines are clearly implicated in the recruitment of TAMs, including macrophage colony-stimulating factor-1 (M-CSF, CSF-1) and monocyte chemotactic protein-1 (MCP-1, CCL2).5,8 CSF-1 signaling through its receptor CSF1R (CD115, c-fms) is a critical regulator of the survival, differentiation, and proliferation of monocytes and macrophages.9 Early studies by Lin et al using CSF-1 op/op mice provided the first evidence for the critical role of CSF-1 in TAM infiltration of spontaneous MMTV-PyMT breast tumors.8 These TAM-depleted tumors exhibited reduced angiogenesis and delayed tumor progression to metastasis. More recent studies using therapeutic antibodies directed against human CSF-1 showed similar antitumor effects on human breast cancer xenografts.10 CSF-1 has also been shown to stimulate VEGF-A production in monocytes, demonstrating its direct role in myeloid cell-mediated angiogenesis.11 Recently, CSF1R expression was observed on MDSCs,12,13 although the consequence of this expression was not experimentally evaluated.

GW2580, a selective small molecule kinase inhibitor of CSF1R, was recently described.14 This orally bioavailable competitive inhibitor of adenosine triphosphate binding completely prevented CSF1R-dependent growth of macrophages in vitro and in vivo at therapeutically relevant doses.14 Subsequent in vitro kinase assays demonstrated at least 100-fold selectivity for its target compared with approximately 300 other structurally related and unrelated kinases.15 The selectivity and specificity of GW2580 make it a powerful pharmacologic tool for determining the contributions of CSF1R signaling to the recruitment and function of different TIM subsets in vivo.

In the current study, we evaluate the impact of CSF1R signaling on the recruitment of various TIM subsets and their contributions to tumor progression. Using GW2580, we show that recruitment of TAMs as well as MO-MDSCs to lung, melanoma, and prostate tumors is regulated by CSF1R signaling. These TIM subsets modulate the expression of VEGF-A, MMP-9, and ARG1, thus contributing to the proangiogenic and immunosuppressive environment within the tumor. Moreover, we demonstrate that targeting CSF1R signaling in combination with a specific blocking antibody against VEGFR-2 results in greater inhibition of tumor angiogenesis along with synergistic tumor growth reduction compared with antiangiogenic therapy alone. This work also highlights a TIM-mediated compensatory mechanism involving MMP-9, which may underlie tumor evasion of antiangiogenic therapy. Overall, these data demonstrate the importance of CSF1R signaling for the recruitment and function of distinct TIM subsets, including MDSCs, in solid tumors.

Methods

Cell culture

Murine macrophage RAW264.7 cells (ATCC), 3LL Lewis lung carcinoma cells (ATCC), B16F1 melanoma cells (ATCC), and ras + myc-transformed RM-1 prostate tumor cells (a kind gift from Dr Timothy C. Thompson, Baylor College of Medicine) were cultured in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium (DMEM) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 100 U/mL penicillin, and 100 μg/mL streptomycin (complete DMEM) at 37°C with 5% CO2.

Viability assay

Cell viability studies were performed using murine bone marrow–derived macrophages (BMDMs). Briefly, mouse bone marrow cells were harvested by flushing the tibias and femurs of adult C57BL/6 mice followed by red blood cell (RBC) lysis (Sigma-Aldrich). Cells were cultured for 5 to 7 days in complete DMEM with 10 ng/mL mouse CSF-1 (R&D Systems). BMDMs (1.5 × 104 cells/well in 96-well plates) were incubated with 10 or 50 ng/mL CSF-1 in the presence or absence of GW2580 (R.I. Chemical). GW2580 was dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide at 25mM and stored at −20°C. Cell viability was measured at indicated time points using the CCK-8 assay (Dojindo).

In vitro migration assay

BMDMs (2 × 105 cells) were seeded in cell culture inserts (8-μm pore size; BD Falcon) in DMEM containing 0.1% FBS with or without 1000nM GW2580. Inserts were placed in 24-well plates with DMEM containing 0.1% FBS in the presence or absence of 10 ng/mL CSF-1 and/or 1000nM GW2580. After 6 hours, migrated cells were immediately fixed in 3% paraformaldehyde stained with 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI). At least 10 fields/well at 4× magnification were quantified using ImageJ Version 1.34s (NIH).

Western blot analysis

Tissues were minced to a fine powder in liquid nitrogen and lysed in 1% NP-40 lysis buffer containing protease inhibitor cocktail (1:1000, Sigma-Aldrich) and 2mM sodium orthovanadate (Sigma-Aldrich). Protein lysates (50-100 μg) were separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane. Membranes were probed and reprobed using antibodies specific for mouse MMP-9 or α-tubulin (1:1000, Abcam) and detected using an enhanced chemiluminescence kit (GE Healthcare).

Immunoprecipitation

RAW264.7 cells (5 × 105 cells/well in 6-well plates) were cultured in DMEM containing 0.1% FBS overnight and then incubated with GW2580 for 1.5 hours followed by stimulation with CSF-1 in the presence or absence of GW2580 for 20 minutes. Protein lysates (500 μg) were incubated with antimouse CSF1R antibody (1:250; Upstate) for 1 hour at 4°C before adding protein A/G PLUS-Agarose (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) overnight. Samples were separated as described in “Western blot analysis,” and membranes were probed using antibodies specific for mouse CSF1R (1:2000, Upstate), mouse phosphotyrosine (1:1000, PY99; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), or β-actin (1:5000; Sigma-Aldrich).

Gelatin zymography

Protein lysates (200 μg) were purified with Gelatin Sepharose pre-equilibrated in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; GE Healthcare) for 2 hours at 4°C with constant rotation, washed twice in PBS, and separated through a 0.1% gelatin-containing sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. Gels were washed with renaturing buffer (2.5% Triton X-100 in water) for 1 hour and then incubated for 24 hours at 37°C in reaction buffer (50mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 10mM CaCl2, 0.02% sodium azide). Gels were stained in 0.1% amido black and destained with destaining solution (10% acetic acid, 30% methanol, 60% H2O).

Real-time RT-PCR analysis

Real-time quantitative reverse-transcribed polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) was carried out as previously described.16 Primer sequences and product sizes are listed in supplemental Table 1 (available on the Blood website; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article).

In vivo tumor models

C57BL6 male mice (4-8 weeks old) were purchased from Taconic Farms, Inc. 3LL cells (2 × 105 cells) and B16F1 cells (105 cells) were implanted subcutaneously above the right shoulder. All animal experiments were approved by the Animal Research Committee of the University of California–Los Angeles. Tumor size was measured by digital calipers as previously described.16 Mice were killed and tissues were analyzed at the ethical tumor size limit of 1 cm in diameter. For orthotopic implants, RM-1 cells (5 × 103 cells in 50% Matrigel) were surgically implanted in the dorsolateral prostate of C57BL/6 male mice as previously described.16 Mice were treated with control diluent (0.5% hydroxypropyl methylcellulose, Sigma-Aldrich; 0.1% Tween20 in distilled H2O) or GW2580 by oral gavage beginning 1 day after tumor implantation. For clodronate liposome (Clodrolip) studies, mice were treated with PBS or Clodrolip at 0.2 mL per 25 g total body weight every third day beginning 2 days after tumor implantation. Clodronate was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Liposome-encapsulated clodronate was prepared as previously described.17 For DC101 studies, mice were treated with PBS control or 800 μg DC101 every other day (intraperitoneally). For combination studies, mice were treated with 160 mg/kg GW2580 daily and DC101 every other day beginning 1 day after tumor implantation.

MaFIA transgenic mice were bred in-house (originally obtained from Dr Donald Cohen, University of Kentucky). To generate MaFIA chimeras, bone marrow cells were harvested from donor MaFIA mice and intravenously injected into lethally irradiated (950 cGy) recipient C57BL/6 mice and transplanted mice recovered for at least 4 weeks. To ablate CSF1R+ cells, mice were treated intravenously or intraperitoneally with 4% ethanol (control) or AP20187 (in 4% ethanol, ARIAD Pharmaceuticals) as previously described.18

Immunohistochemistry

Tissues were harvested and fixed in 3% paraformaldehyde overnight. Sections (5 μm) were stained with the following antibodies: anti-F4/80 (1:500; Serotec), anti–Gr-1 (1:100; eBioscience), anti–MMP-9 (1:1000; Abcam), anti-GFP (1:100; Invitrogen), anti–Lyve-1 (1:300; RELIATech), or anti-CD31 (1:300; BD Biosciences) antibodies. Histology was performed, processed, and quantified as previously described.19 The samples were analyzed using an Olympus BX41 fluorescent microscope fitted with a Q-Imaging QICAM FAST 1394 camera. Images were captured at 4×, 10×, or 20× magnification using QCapture Pro Version 5.1 (Media Cybernetics), quantified using ImageJ Version 1.34s (NIH), and processed using Adobe Photoshop CS.

Flow cytometry

To prepare single-cell suspensions for flow cytometry, harvested tissues (tumors, lungs, and livers) were dissected into approximately 1- to 3-mm3 fragments and digested with 80 U/mL collagenase (Invitrogen) in DMEM containing 10% FBS for 1.5 hours at 37°C while shaking. Spleens were gently dissociated between 2 glass slides for single-cell isolation. Peripheral blood was isolated directly into BD Vacutainer K2 EDTA tubes (BD Biosciences). After RBC lysis, single-cell suspensions were filtered and incubated for 30 minutes on ice with the following: fluorescein isothiocyanate-, phycoerythrin-, allophycocyanin-, peridinin chlorophyll protein-Cy5.5–, PE-Cy7–, and APC-Cy7–conjugated antibodies (CD45, CD11b, Gr-1, and F4/80) were purchased from eBioscience (1:200). Ly6C (1:200) and 7-amino-actinomycin D were purchased from BD Bioscience. DAPI was purchased from Invitrogen. Cells were washed twice before analysis on the BD LSR-II flow cytometer (Beckman Coulter). Cell sorting was performed on the BD FACSAria-II high-speed cell sorter using fluorophore-conjugated antibodies for CD11b, Gr-1, and Ly6C. Data were analyzed with FlowJo software (TreeStar).

In vivo migration assay

Bone marrow cells (BMCs) obtained from naive C57BL/6 mice were labeled with 0.25μM CFDA-SE (CFSE, Invitrogen) for 3 minutes at room temperature, washed, and incubated with control or 1000nM GW2580 on ice for 1 hour. A total of 20 × 106 cells were then intravenously injected into 3LL tumor-bearing mice (day 10). Mice were treated with control diluent or 160 mg/kg GW2580 4 hours before BMC injection and killed 4 hours after injection. Harvested tissues were subjected to flow cytometric analysis of infiltrating BMCs.

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as mean plus or minus SEM. Statistical comparisons between groups were performed using the Student t test.

Results

Inhibiting CSF1R signaling with the pharmacologic inhibitor GW2580

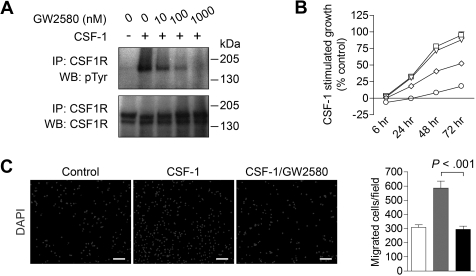

We first validated the inhibition of CSF1R phosphorylation with GW258014 using RAW264.7 murine macrophages stimulated with 10 ng/mL CSF-1. CSF1R phosphorylation was potently inhibited in a dose-dependent fashion (Figure 1A) with an IC50 of approximately 10nM, substantiating prior results using in vitro kinase assays.15 Complete phospho-inhibition was observed between 100 and 1000nM GW2580. These experiments were repeated using 50 ng/mL CSF-1 with similar results (data not shown).

Figure 1.

Inhibiting CSF1R signaling in macrophages with the pharmacologic inhibitor GW2580. (A) Immunoprecipitation and Western blot analysis of Raw264.7 murine macrophage cells stimulated with 10 ng/mL CSF-1 for 20 minutes in the absence or presence of 10, 100, or 1000nM GW2580. Blot was probed for tyrosine phosphorylation (pTyr), stripped, and reprobed for total CSF1R. (B) BMDMs were stimulated with CSF-1 in the absence (□) or presence of 10nM (▵), 100nM (◇), or 1000nM (○) GW2580. At the indicated time points, cell viability was measured using the CCK-8 assay and compared with unstimulated control. (C) BMDMs were seeded on 8-μm transwell inserts, and CSF-1 was added to the lower chamber in the absence or presence of 1000nM GW2580 (added to both chambers). Cells were allowed to migrate toward CSF-1 for 6 hours and then fixed and stained with DAPI. Representative images are shown and migrated cells were quantified using ImageJ software (□, control, no CSF-1;  , CSF-1; ■, CSF-1/GW2580). Scale bar represents 100 μm.

, CSF-1; ■, CSF-1/GW2580). Scale bar represents 100 μm.

CSF1R signaling plays a critical role in the survival, differentiation, and proliferation of monocytes and macrophages.9 As shown in Figure 1B, CSF1R blockade with GW2580 showed a dose-dependent inhibition of CSF-1–stimulated growth of murine BMDMs, with an IC50 of approximately 100nM. Similar growth inhibition was observed with BMDMs stimulated with 50 ng/mL CSF-1 (data not shown). Of note, GW2580 showed negligible effects on BMDM growth in the absence of CSF-1 (data not shown). Moreover, BMDM migration toward CSF-1 was completely abrogated with 1000nM GW2580 (Figure 1C, P < .001).

Pharmacologic effects of GW2580 in vivo

Before pursuing a therapeutic study, we performed a dose titration of GW2580 at 20 mg/kg or 80 mg/kg twice a day or 160 mg/kg once daily in naive mice by oral gavage. As shown in supplemental Figure 1A, 160 mg/kg once daily achieved GW2580 levels that peaked at approximately 9μM, and remained greater than 1μM for 24 hours, exceeding the estimated minimum plasma concentration to achieve a therapeutic effect.14 We also assessed the potential systemic toxicities associated with prolonged GW2580 treatment. Tumor-bearing mice treated for 14 days with 160 mg/kg GW2580 showed no significant differences in total body weight compared with control diluent-treated mice (supplemental Figure 1B). In addition, serum levels of alanine aminotransferase, aspartate aminotransferase, total protein, blood urea nitrogen, and lactate dehydrogenase were not significantly different, demonstrating minimal hepatic and renal toxicities associated with the 160 mg/kg GW2580 dosing regimen (supplemental Figure 1C-G). These pharmacokinetic and toxicology studies indicate that GW2580 treatment at 160 mg/kg once daily is as effective as 80 mg/kg twice a day.14

Inhibiting CSF1R signaling targets distinct TIM subsets in vivo

GW2580 has been shown to be an effective inhibitor of CSF1R signaling in vivo, reducing growth of the CSF-1–dependent monocytic cell line M-NSF-60 in mice.14 However, the effects of GW2580 on infiltrating myeloid cells in a solid tumor model have yet to be investigated. In addition, the role of CSF1R signaling in the recruitment of other TIM subsets such as MDSCs remains unclear, although it has been certainly implicated in the recruitment of TAMs.8,10,20 We demonstrated expression of Csf1r in murine macrophages but not in 3LL Lewis lung carcinoma, B16F1 melanoma, or RM-1 prostate tumor cell lines (data not shown), thus precluding direct effects of GW2580 on tumor cells.

We treated C57BL/6 mice bearing subcutaneously implanted 3LL lung carcinoma with control diluent or GW2580 at 20 mg/kg or 80 mg/kg twice a day, or 160 mg/kg once daily by oral gavage. Flow cytometric analysis of tumors revealed that total CD45+CD11b+ myeloid cells were reduced by more than 2-fold in the tumors of GW2580-treated mice compared with control (supplemental Figure 2A, P < .05). CD11b+F4/80+ TAMs were also significantly reduced by more than 2-fold (supplemental Figure 2B, P < .05). Histologic analysis revealed a similar reduction in F4/80+ TAMs, equally reduced at the center and edges of tumors from 80 mg/kg GW2580-treated mice (supplemental Figure 2C, P < .01), whereas the 20 mg/kg regimen resulted in a lesser extent of TAM reduction (P = .07).

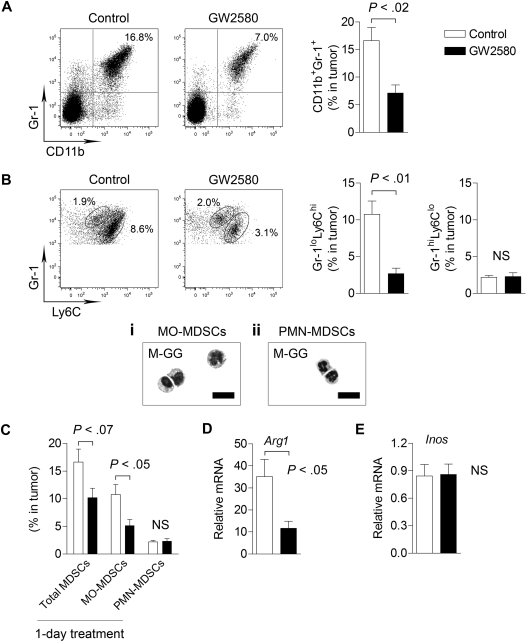

Interestingly, we observed a greater than 2-fold reduction in total CD11b+Gr-1+ MDSCs in tumors from GW2580-treated mice (Figure 2A, P < .02). Recent reports further distinguish the myeloid subsets within the MDSC population as consisting of MO-MDSCs and PMN-MDSCs.5,13 As shown in Figure 2B, Gr-1loLy6Chi cells constituted a large portion of total MDSCs in the tumor (∼ 80%) compared with a considerably smaller Gr-1hiLy6Clo population. Inhibition of CSF1R signaling strongly reduced the recruitment of Gr-1loLy6Chi cells by approximately 4-fold (P < .01) but had no effect on Gr-1hiLy6Clo cells (Figure 2B).

Figure 2.

Targeting MO-MDSC infiltration by inhibiting CSF1R signaling. 3LL tumor cells were subcutaneously implanted in C57BL/6 mice, and mice were treated with control diluent or 160 mg/kg GW2580 once daily. At day 14, single-cell suspensions of tumors were analyzed by flow cytometry. Representative images and quantification of total CD11b+Gr-1+ MDSCs (A), Gr-1loLy6Chi MO-MDSCs and Gr-1hiLy6Clo PMN-MDSCs (B) are shown (n = 4/group). May-Grunwald-Giemsa staining of sorted MDSC populations within the tumor (Bi-ii). (C) Mice were implanted with 3LL tumors and treated with GW2580 once 24 hours before harvesting tumors for flow cytometric analysis. Total MDSCs, MO-MDSCs, and PMN-MDSCs were quantified (n = 3-4/group). RT-PCR analysis of Arg1 (D) and Inos (E) expression in tumors from control and GW2580-treated mice. Relative mRNA expression was normalized to β-actin (n = 6/group). Scale bars represent 50 um.

The morphology of sorted MDSC populations was further assessed by May-Grunwald-Giemsa staining. CD11b+Gr-1loLy6Chi cells were mononuclear with heterogeneous size and nuclear shape, resembling inflammatory monocytes/macrophages (Figure 2Bi). The majority of CD11b+Gr-1hiLy6Clo cells were polymorphonuclear, with neutrophil-like morphology (Figure 2Bii). Therefore, we hereafter consider all tumor-infiltrating CD11b+Gr-1loLy6Chi cells as MO-MDSCs and all tumor-infiltrating CD11b+ Gr-1hiLy6Clo cells as PMN-MDSCs. To evaluate short-term inhibition of CSF1R signaling in tumor-bearing mice, we treated mice bearing established tumors (∼ 1 cm in diameter) with a single dose of GW2580. This 1-day treatment resulted in a significant reduction in MO-MDSCs (Figure 2C, P < .05), indicating a critical role for CSF1R signaling in MDSC infiltration. We observed similar inhibition of MDSCs using GW2580 in the B16F1 melanoma model (data not shown).

Recent studies suggest that ARG1 and iNOS expression mediates the immunosuppressive properties of MDSCs.5 By RT-PCR, we found that Arg1 expression (Figure 2D, P < .05), but not Inos (Figure 2E), was significantly reduced in tumors of GW2580-treated mice. These data suggest that MO-MDSCs primarily regulate intratumoral levels of ARG1, but not iNOS. Collectively, we demonstrate the profound inhibition of TIMs by GW2580 and the requirement of CSF1R signaling for the tumor recruitment of MO-MDSCs.

CSF1R signaling regulates tumor recruitment of myeloid cells from peripheral blood

We sought to determine whether the reduction in TIMs was the result of systemic myeloid cell depletion or a specific effect on tumor recruitment. As shown in Table 1, we analyzed MO levels in the bone marrow, peripheral blood, and spleens of tumor-bearing mice after GW2580 treatment for 14 days, observing significant reductions in percentages and absolute numbers in bone marrow (P < .001) and spleens (P < .05), and a reducing trend in the peripheral blood (P = .22). The reductions in MOs in each of these tissues approached levels observed in naive mice. Spleen weights (control, 86 mg ± 2.2 vs GW2580, 68.4 mg ± 6.1, P < .05, vs naive, 68.5 mg ± 4.9) and total splenocyte numbers (control, 98.3 ± 5.0 vs GW2580, 79 ± 5.6, P < .05) were also reduced to naive levels. Naive mice treated with GW2580 for 14 days revealed no changes in MOs in the bone marrow and peripheral blood. However, we did observe a significant 25% reduction in total MOs in the spleens of GW2580-treated naive mice, suggesting a partial requirement for CSF1R signaling in this tissue. Collectively, these results suggest that the induction of MDSCs is a tumor-induced systemic effect, which can be reversed to a large extent by blockade of CSF1R signaling.

Table 1.

MO levels in naive (tumor-free) and 3LL tumor-bearing mice

| Treatment group/category | Bone marrow |

Peripheral blood |

Spleen |

Tumor |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Percentage | Cells × 103/femur | Percentage | Cells × 103/mL | Percentage | Cells × 103/spleen | Percentage | Cells/mg tumor | |

| Naive/control | 10.7 ± 0.3 | 1858.7 ± 258.8 | 2.3 ± 0.2 | 51.2 ± 7.9 | 0.9 ± 0.2 | 609.2 ± 11.1 | NA | NA |

| Naive/GW2580 | 10.9 ± 0.4 | 1816.0 ± 136.0 | 2.5 ± 0.2 | 56.7 ± 8.8 | 0.7 ± 0.1 | 459.7 ± 18.7 | NA | NA |

| P | > .3 | > .3 | > .3 | > .3 | > .3 | < .01 | ||

| TB/control | 15.2 ± 0.2 | 2322.9 ± 106.8 | 4.1 ± 0.9 | 86.1 ± 23.1 | 1.6 ± 0.1 | 1434.1 ± 22.7 | 11.2 ± 1.9 | 5662.2 ± 830.5 |

| TB/GW2580 | 11.4 ± 0.5 | 1750.4 ± 100.5 | 2.5 ± 0.6 | 52.7 ± 14.9 | 1.2 ± 0.1 | 798.2 ± 177.1 | 2.7 ± 0.8 | 1459.3 ± 247 |

| P | < .001 | < .01 | .22 | .27 | < .05 | < .05 | < .01 | < .01 |

MO levels in naive (tumor-free) and 3LL tumor-bearing mice. Monocyte levels were measured by flow cytometry in the bone marrow, peripheral blood, spleens, and tumors of control and GW2580-treated tumor-free mice (Naive), as well as control and GW2580-treated tumor-bearing mice (TB). Percentages and absolute numbers are represented as mean ± SEM. Monocyte levels from control and GW2580-treated mice were assessed using the Student t test.

NA indicates not applicable.

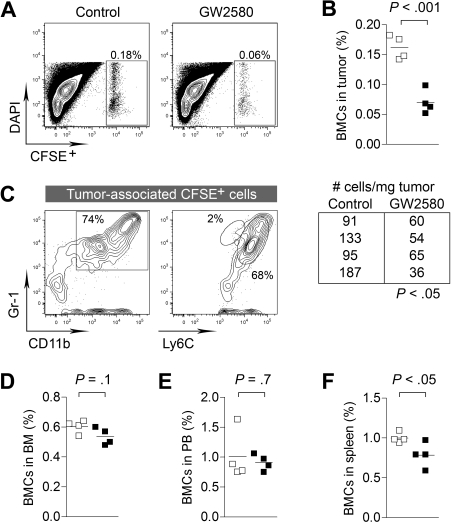

To better delineate the kinetics of CSF1R blockade on the tumor recruitment of myeloid cells, we intravenously injected CFDA-SE–labeled BMCs into 3LL tumor-bearing mice. To ensure adequate inhibition of CSF1R signaling in vivo, mice were pretreated with GW2580 for 4 hours before BMC injection. Organs were harvested 4 hours after BMC injection and subjected to flow cytometry. Short-term CSF1R inhibition showed a dramatic reduction in BMC recruitment to the tumor (Figure 3A-B, P < .001), whereas minimal changes were observed in the bone marrow and peripheral blood (Figure 3D-E). We did observe a significant reduction in BMCs in the spleen (Figure 3F, P < .05). We confirmed that approximately 70% of tumor-recruited BMCs were CD11b+Gr-1+ myeloid cells with Ly6Chi expression (Figure 3C). Overall, we have demonstrated the impact of CSF1R signaling in the migration of MO-MDSCs from the blood to the tumor. In addition to the known functions of CSF1R signaling in normal tissue recruitment of myeloid cells, the involvement of this pathway is greatly accentuated in pathologic accumulation in the tumor.

Figure 3.

CSF1R signaling regulates tumor recruitment of myeloid cells from peripheral blood. 3LL tumor-bearing mice (day 10 after implantation) were treated with control diluent or GW2580 (for 4 hours) and subsequently intravenously injected with 20 × 106 CFSE-labeled BMCs. After 4 hours, animals were killed and tissues were analyzed for recruitment of CSFE+ BMCs by flow cytometry. (A-B) Percentage of CFSE+ BMCs in tumor and absolute number of cells/mg tumor are shown (n = 4/group). (C) The majority of tumor-recruited CFSE+ cells were CD11b+Gr-1+ and Ly6Chi. (D-F) Percentage of CFSE+ BMCs in the bone marrow, peripheral blood, and spleens are shown (n = 4/group).

Reduced tumor angiogenesis by selectively inhibiting CSF1R signaling

Because TAMs and MDSCs have been shown to play important roles in tumor vasculature and tissue remodeling, we evaluated angiogenic and lymphangiogenic factors that are modulated by GW2580 treatment. Expression levels of Vegf-a and Mmp9 were reduced significantly by approximately 35% and 70% in treated tumors, respectively (Figure 4A,D, P < .05). Expression levels of Vegf-c, Mmp2, and other MMPs and TIMPs were unaffected (Figure 4B-C; and data not shown). The reduction of MMP-9 was verified at the protein level in GW2580-treated tumors (Figure 4E-F). Next, we evaluated the impact of GW2580 treatment on tumor angiogenesis. Vascular density, as assessed by staining of the endothelial marker CD31, showed a dose-dependent reduction with GW2580 treatment (Figure 4G-H, P < .01). Unexpectedly, the growth of subcutaneous 3LL tumors was not impaired by the suppression of tumor angiogenesis with GW2580 treatment (Figure 4I-J). Likewise, negligible tumor growth suppression was also observed in mice bearing B16F1 melanoma (Figure 4K).

Figure 4.

Angiogenesis and growth kinetics of tumors treated with GW2580. (A-D) Tumors were harvested on day 14 after tumor implantation and GW2580 treatment, and mRNA expression was quantified using RT-PCR for the stated genes. Relative mRNA expression was normalized to β-actin (n = 6/group). (E) MMP-9 protein levels from tumors were analyzed by Western blot and normalized to α-tubulin. (F) Quantification of MMP-9 protein levels by ImageJ software (n = 3/group). (G) Representative CD31+ vascular staining of 3LL tumors from control and GW2580-treated mice is shown. (H) Quantification of CD31+ area was performed using ImageJ software (n ≥ 5/group). Tumor volume was monitored by caliper measurements of 3LL tumors (I-J; n = 6/group) and B16F1 tumors (K; n = 3/group) in mice treated with control diluent, 20 mg/kg, or 80 mg/kg GW2580 twice a day, or 160 mg/kg GW2580 once daily. Scale bars represent 100 μm.

In an attempt to better understand the impact of macrophage ablation on these tumors, we used the MaFIA model.18 These mice express an inducible Fas-based suicide gene and the EGFP gene under the control of the macrophage-specific c-fms promoter. On treatment with the dimerizing drug AP20187, cells expressing CSF1R rapidly undergo apoptosis. We generated MaFIA chimeras by transplanting MaFIA donor bone marrow into naive mice. Supplemental Figure 3A demonstrates efficient bone marrow transplantation, with greater than 80% of CD11b+ myeloid cells in the peripheral blood coexpressing EGFP. Treatment of 3LL tumor-bearing mice with AP20187 resulted in a substantial depletion of CSF1R+ myeloid cells in the peripheral blood and spleens (supplemental Figure 3B-C) and a significant reduction in F4/80+ and GFP+ TIMs (supplemental Figure 3D-E, P < .01). Recapitulating the results of GW2580 treatment, we observed a significant reduction in angiogenesis in these macrophage-ablated tumors (supplemental Figure 3F, P < .01) without a concomitant decrease in tumor growth (supplemental Figure 3G). These data suggest that CSF1R+ TIMs, including TAMs and MO-MDSCs, contribute significantly to tumor angiogenesis.

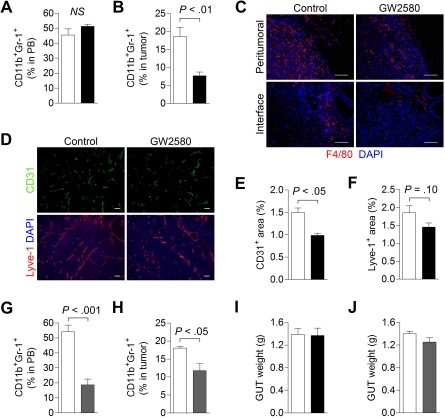

Reduced MDSC infiltration and tumor angiogenesis by inhibiting CSF1R signaling in an orthotopic prostate tumor model

We also evaluated the effects of inhibiting CSF1R signaling in the orthotopic RM-1 prostate tumor model. Flow cytometric analysis revealed negligible effects on peripheral blood total MDSC levels with GW2580, possibly because of a lack of change in the PMN-MDSC population (Figure 5A). However, we did observe a greater than 2-fold reduction in tumor-associated MDSCs, probably reflecting reductions in MO-MDSCs (Figure 5B, P < .01). Moreover, a significant reduction in F4/80+ TAMs, particularly at the normal prostate-tumor interface regions, was observed (Figure 5C). Analysis of the spleens from GW2580-treated mice revealed slight reductions in F4/80+ macrophages and Gr-1+ MDSCs (supplemental Figure 4A). GW2580 treatment also reduced blood vessel density in orthotopic RM-1 tumors by approximately 35% (Figure 5D-E, P < .05). We observed a slight but insignificant reduction in lymphatic vascular density, as assessed by the lymphatic endothelial marker, Lyve-1 (Figure 5D,F, P = .10). These findings suggest that TIMs contribute to angiogenesis and, to a lesser extent, lymphangiogenesis in this murine prostate tumor model.

Figure 5.

Targeting MDSC infiltration and tumor angiogenesis in orthotopic RM-1 prostate tumors. RM-1 prostate tumor cells were implanted intraprostatically in the dorsolateral lobes of C57BL/6 males. Mice were treated with control diluent, GW2580, PBS, or clodronate liposomes (Clodrolip) at the appropriate dosing regimen. (A) Peripheral blood (n = 5/group) total MDSCs were analyzed by flow cytometry in control (white bar) and GW2580-treated (black bar) mice. (B) Tumor-associated MDSC levels (n = 3-5/group) were also analyzed by flow cytometry in control and GW580-treated mice. (C) Tumor tissue was processed and subjected to histologic staining of F4/80+ TAMs at the peritumoral regions (top) and normal prostate-tumor interface (bottom). (D) Representative CD31+ blood and Lyve-1+ lymphatic vascular staining of RM-1 prostate tumors from control and GW2580-treated mice are shown. Quantification of CD31+ (E) and Lyve-1+ (F) area was performed using ImageJ software (n = 3-5/group). (G-H) Peripheral blood (n = 5/group) and tumor-associated MDSC (n = 3 or 4/group) levels were analyzed by flow cytometry in PBS- (white bar) and Clodrolip-treated (gray bar) mice. Genitourinary tract (GUT) weight was measured at endpoint in GW2580-treated (I) and Clodrolip-treated (J) mice (n = 3-5/group). Scale bars represent 100 μm.

Next, we examined the impact of a conventional pharmacologic agent, Clodrolip, on macrophage ablation in RM-1 prostate tumors.21 Treatment of tumor-bearing mice with Clodrolip resulted in a significant reduction in peripheral blood total MDSCs (Figure 5G, P < .001) as well as tumor-associated MDSCs (Figure 5H, P < .05), albeit less pronounced than GW2580. Immunohistochemical analysis also revealed substantial reductions in splenic F4/80+ macrophages and Gr-1+ MDSCs in Clodrolip-treated mice (supplemental Figure 4B). However, similar to the findings in 3LL and B16F1 tumors, neither GW2580 nor Clodrolip treatment suppressed tumor growth in this model (Figure 5I-J).

Combination therapy with GW2580 and an anti-VEGFR-2 antibody results in synergistic tumor growth reduction

MDSCs were recently implicated in the tumor resistance to antiangiogenic therapy.22 Using anti-Gr-1 monoclonal antibodies to deplete these myeloid cells in vivo in combination with anti-VEGF therapy achieved further reductions in tumor growth over anti-VEGF therapy alone. Because the heterogeneity of MDSCs in tumors is widely accepted,5,7,13 it is important to identify which TIM subsets confer this resistance. To gain further insights into this issue, we exploited the inhibitory effects of GW2580 on TIMs to evaluate pharmacologic CSF1R blockade in combination with antiangiogenic therapy (anti-VEGFR-2 mAb, DC101).

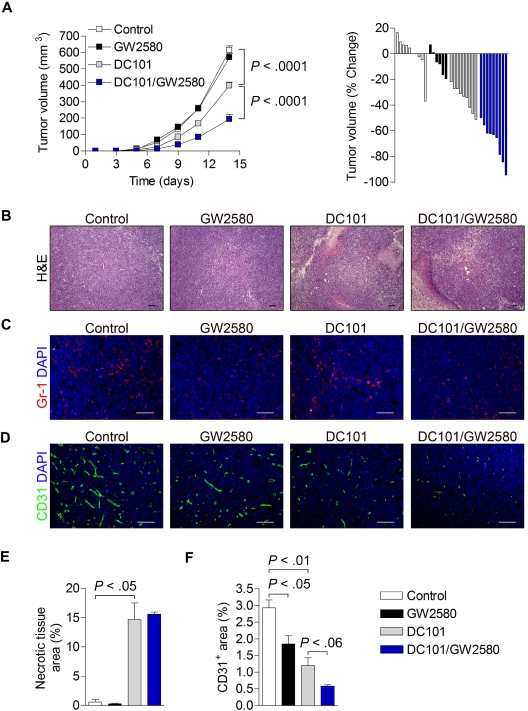

3LL-tumor bearing mice were treated with control diluent, 160 mg/kg/day GW2580 alone, 800 μg DC101 alone every other day (intraperitoneally), or GW2580 in combination with DC101. As shown in Figure 6A, whereas DC101 alone reduced tumor growth by 35% (P < .001), the combination of DC101 and GW2580 resulted in an apparent synergistic tumor growth reduction of approximately 70% (P < .001). Again, tumor growth was unaffected by GW2580 treatment alone. Histologic analysis of tumors revealed a significant increase in necrotic area after DC101 and DC101/GW2580 treatment, most probably reflecting the direct effects of DC101 in both treatment groups (Figure 6B,E). Moreover, Gr-1+ MDSCs in the tumor were dramatically reduced by GW2580 in single and combination treatments, whereas DC101 treatment alone showed slightly increased signals compared with control (Figure 6C). Similar results were observed with histologic analysis of F4/80+ TAMs (data not shown). Tumor angiogenesis was incrementally reduced in each treatment group, with an overall 80% reduction in vessel density with combination treatment (Figure 6D,F).

Figure 6.

Synergistic tumor growth reduction and inhibition of angiogenesis by combination therapy with GW2580 and anti–VEGFR-2 antibody DC101. 3LL tumors were subcutaneously implanted and mice were treated with control diluent, GW2580 or DC101 alone, or a combination of DC101/GW2580 for 14 days. (A) Tumor volume was monitored by caliper measurements. Tumor volume is presented as the average tumor volume (mm3) per group over time and as a waterfall plot of tumor volume (% change) of each animal per group at day 14 (n = 5-9/group). At day 14, tumors were harvested and subjected to histologic analysis of hematoxylin and eosin (B), Gr-1+ MDSCs with DAPI (C), and CD31+ vessels with DAPI (D). Necrotic tissue area (E) and CD31+ area (F) were quantified using ImageJ software (n ≥ 5/group). Data represent combined averages from 2 independent animal experiments. Scale bars represent 100 μm.

TIMs mediate an antiangiogenic compensatory mechanism involving MMP-9

The notion that tumors evade antiangiogenic therapy has recently received heightened attention.22–24 Several reports suggest the induction of Angiopoietin-1 (Ang-1)25 and fibroblast growth factor-2 (FGF-2)26 might allow growing tumors to circumvent the absence of VEGF signaling. Moreover, induction of PlGF and MMP-9 expression after therapy with anti-VEGFR-2 blocking antibody27 has also been implicated as a compensatory mechanism. However, the precise mechanism or the cells in the tumor microenvironment that are involved in the evasion of antiangiogenic therapy remain undefined. The synergistic therapeutic impact of GW2580 with anti-VEGFR-2 therapy could probably provide further insight on the evasion mechanism.

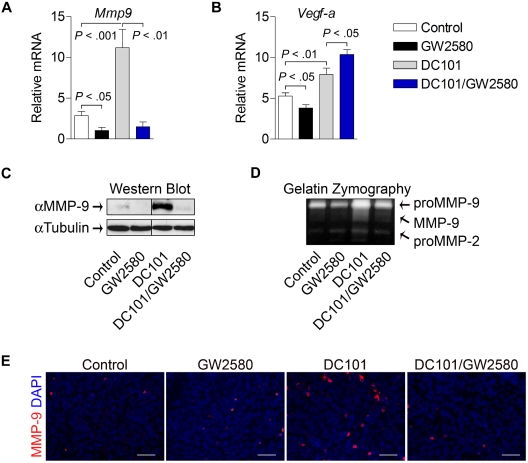

To further characterize myeloid cell contributions to evasion of antiangiogenic therapy, tumors from each treatment group were analyzed for the expression of pro-angiogenic genes. As shown in Figure 7A, levels of Mmp9 were greatly induced in tumors treated with DC101 alone (4-fold, P < .001). Interestingly, this induction was completely abolished in tumors from the combination treatment group (P < .01), indicating that TIMs play a critical role in the regulation of MMP-9 induction with antiangiogenic therapy. These findings were confirmed at the protein level using Western blot analysis and at the functional level using gelatin zymography (Figure 7C-D). Histologic staining revealed more abundant MMP-9–expressing cells with heterogeneous myeloid cell morphology in viable areas of DC101-treated tumors, which were reduced in the combination group (Figure 7E). Although Vegf-a expression was modestly reduced by GW2580 alone, DC101 treatment induced its expression (1.5-fold, P < .01), which was further enhanced by the combination treatment (Figure 7B, 2-fold, P < .05,). We also analyzed the expression levels of other growth factors suggested to be important in therapeutic resistance.25–27 Surprisingly, the expression levels analyzed by RT-PCR of Ang-1, Ang-2, Fgf-1, Fgf-2, and Pdgfβ, were reduced, rather than induced, by 25% to 50% in the DC101-treated group (data not shown). Soluble vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-1 (sVegfr-1) has also been linked to antiangiogenic processes mediated by TIMs28,29; however, we did not observe significant differences in expression of sVegfr-1 or granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor, a potent stimulator of sVegfr-1 expression, in these treatment groups (data not shown). Collectively, these data demonstrate that TIMs mediate at least one compensatory mechanism involving MMP-9 that contributes to tumor evasion of antiangiogenic therapy.

Figure 7.

TIMs mediate MMP-9 induction by anti–VEGFR-2 therapy. Tumors were harvested at day 14, and mRNA expression was quantified using RT-PCR for Mmp9 (A) and Vegf-a (B). Relative mRNA expression was normalized to β-actin (n ≥ 5/group). (C) MMP-9 protein levels from tumors were analyzed by Western blot and normalized to α-tubulin (n = 6/group). Representative images are shown. (D) The same tumor lysates were analyzed by gelatin zymography (n = 6/group). Representative images are shown. Tumor tissue was subjected to histologic analysis of MMP-9 expression with DAPI (E). Scale bars represent 50 μm.

Discussion

TIMs, including TAMs, have been implicated in tumor progression, invasion, and metastasis. Early studies have investigated the role of CSF1R signaling in TAM infiltration using CSF-1 op/op mice.8 These knockout mice display marked deficiencies in total peripheral blood monocytes and tissue macrophages but also show various systemic effects, including total body weight reductions and skeletal abnormalities.30 More recent studies using antisense oligonucleotide and antibodies directed against CSF-1 showed the impact of CSF1R signaling on TAM infiltration and breast tumor xenograft growth.10,20 These latter studies used immunocompromised mice, a potential limiting factor for determining the effects of host inflammation on tumor progression. In addition, the human mammary tumors used in these studies express CSF1R, raising the possibility of autocrine effects. Nevertheless, the results from op/op mice and CSF-1 blockade studies were seminal in linking CSF1R signaling and TAM infiltration to tumor progression and metastasis.

In this study, we used several murine tumor models in immunocompetent mice, which allowed us to directly assess the contributions of distinct myeloid subsets to tumor progression. In addition, the tumor models used in these studies do not express detectable levels of Csf1r by RT-PCR; thus, we were able to eliminate potential autocrine tumor effects when modulating this pathway. Results from this study demonstrate a significant contribution of CSF1R signaling to the recruitment of MDSCs. In addition to these implanted tumor models, preliminary studies with CSF1R blockade in the PTEN-knockout transgenic model of prostate cancer demonstrate the importance of CSF1R signaling for MDSC recruitment to spontaneous tumors (data not shown).31 However, further studies are warranted to evaluate the therapeutic effectiveness of CSF1R blockade as a single agent and in combination with other anticancer therapies using this model. MO-MDSCs were particularly sensitive to CSF1R blockade, although we observed no differences in PMN-MDSC infiltration. This contrasts a recent finding in CCR2-deficient mice using 3LL tumors, where severe reductions in tumor-associated MO-MDSCs were accompanied by massive accumulation of PMN-MDSCs.5 We did not observe recruitment differences in tumor-associated PMN-MDSCs with CSF1R blockade, demonstrating marked distinction between the 2 myeloid recruitment pathways. Expansion of MDSCs in the bone marrow and their systemic accumulation in tumor-bearing mice correlate with primary tumor size.32 In this study, blockade of CSF1R signaling suppressed expansion of MO-MDSCs in the bone marrow and reduced accumulation in the spleen, associated with reduced splenomegaly and total splenocyte numbers. The suppression was seen in the absence of tumor growth differences between control and GW2580-treated mice, suggesting that CSF1R signaling has direct effects on these tumor-induced systemic effects.

Blockade of the CSF1R signaling pathway, either by pharmacologic inhibition of CSF1R kinase or by genetic ablation of CSF1R+ cells using the MaFIA model, did not result in appreciable changes in tumor growth despite significant reductions in tumor angiogenesis. The seminal work of Folkman et al clearly established that growth of tumors is dependent on adequate vascular perfusion.33 A large volume of work in the last 30 years has also demonstrated the direct correlation between blood vessel density and tumor growth. However, on the converse issue of blocking angiogenesis as cancer therapy, it might be inadequate to merely score for blood vessel density as a measure of therapeutic effect. A recent study showed that inhibition of PDGF-B signaling using a selective aptamer AX102 resulted in dramatic reductions in tumor angiogenesis without concomitant reductions in growth of 3LL tumors.34 Another recent study by Stockmann et al, using macrophage-specific depletion of VEGF-A, reported that reduced tumor blood vasculature actually led to significant increases in tumor growth.35 These recent findings indicate that a reduction in tumor vessel density does not necessarily result in reduced growth kinetics and further consideration of vascular integrity and perfusion is needed.

The findings of this study that combined inhibition of CSF1R axis and anti-VEGFR-2 blockade corroborated recent reports, implicating specific TIM subsets that are important for the apparent resistance to antiangiogenic therapy. A prior study clearly implicated Gr-1+ myeloid cells in mediating resistance to anti-VEGF therapy22; however, the Gr-1 antibody treatment used systemically depletes all Gr-1+ populations of macrophage and neutrophil lineage, in addition to other cell types, such as blood lymphocytes and splenic dendritic cells.36 In the current study, we were able to further distinguish and selectively inhibit MO-MDSCs, thus implicating the involvement of this distinct MDSC subset in mediating the resistance to antiangiogenic therapy. We also highlight the induction of MMP-9 as a compensatory mechanism put forth by the tumor to counter antiangiogenic therapy. MMP-9 has been frequently implicated in various aspects of tumor progression, from angiogenesis to tumor invasion and metastasis.37,38 MMP-9 mediates the angiogenic switch by releasing ECM-bound VEGF, thereby increasing the bioavailability of VEGF.39,40 In addition, MMP-9–mediated remodeling of basement membrane is important for new blood vessel sprouting,41 which may also be exploited by tumors in attempts to evade antiangiogenic therapy. Our preliminary data demonstrate that CSF-1 induces MMP-9 expression in murine macrophages in vitro (data not shown), but whether CSF1R signaling directly mediates MMP-9 induction by antiangiogenic therapy warrants further investigation.

The anti-VEGF antibody Avastin is currently approved only in combination with chemotherapy for various solid cancers, including breast and colon. Several theories describe the apparent improved response to anti-VEGF therapy when combined with chemotherapy. First, normalization of tumor vasculature by blockade of VEGF signaling may improve drug delivery, leading to an enhanced chemotherapeutic response in tumors.25,42–44 Second, the systemic leukocyte toxicity with chemotherapy may contribute to the response when combined with antiangiogenic therapy. However, it might be difficult to balance the systemic side effects of chemotherapy, such as myelosuppression, with the therapeutic benefit of combined therapy.

In support of the latter theory, several tyrosine kinase inhibitors (eg, Imatinib, Sunitinib) have been used to treat solid tumors by targeting both tumor- and endothelial cell-directed signaling pathways.45 In addition to inhibiting the receptors in the VEGF, PDGF, and KIT families, these small molecule agents also exhibit significant inhibition of CSF1R kinase activity, which can contribute to the overall therapeutic effects.46 Unfortunately, it is very challenging to decipher the specific therapeutic benefits of selective pathway blockade with multitargeted tyrosine kinase inhibitors. Moreover, pathway-selected therapy is the “Holy Grail” toward minimizing potential toxic side effects. In this study, we demonstrated that the use of the selective CSF1R inhibitor GW250 during tumor development produced minimal systemic toxicity while achieving significant impact on the recruitment of TAMs and MO-MDSCs. Hence, targeting this pathway enables not only a better understanding of the roles of specific TIM subsets in tumor progression but also furthers the development of rational combined therapeutic approaches to combat tumor evasion of antiangiogenic therapy.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr Ebba Brakenhielm for valuable discussion of the manuscript, Bronislaw Pytowski and ImClone Systems for their generous contribution of the mouse anti–VEGFR-2 antibody DC101, Ben Van Handel for flow cytometry expertise, and Nancy Nguyen for technical contributions.

This work was supported by the National Cancer Institute SPORE program (P50 CA092131), Prostate Cancer Foundation (L.W.), and Margaret E. Early Medical Trust award (L.W.). S.J.P. is supported by the career developmental program of UCLA ICMIC (grant P50 CA86306 to H.R. Herschman) and a CDMRP predoctoral training award (W81XWH-09-1–0538).

Footnotes

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Authorship

Contribution: S.J.P. designed and performed most of the research and analyzed the data; J.L.S., Z.S., J.B.B., A.X.T.-C., D.L.M., and M.J. performed additional research; D.A.C. provided the MaFIA model; A.J.L., D.A.C., and M.L.I.-A. provided valuable support throughout the project; L.W. designed the research and supervised the project; and S.J.P. and L.W. wrote the manuscript with valuable contributions from all coauthors.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Lily Wu, Department of Molecular and Medical Pharmacology, CHS 33-142, Box 951735, University of California, Los Angeles, CA 90095; e-mail: LWu@mednet.ucla.edu.

References

- 1.Murdoch C, Muthana M, Coffelt SB, et al. The role of myeloid cells in the promotion of tumour angiogenesis. Nat Rev Cancer. 2008;8(8):618–631. doi: 10.1038/nrc2444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lewis CE, Pollard JW. Distinct role of macrophages in different tumor microenvironments. Cancer Res. 2006;66(2):605–612. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-4005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gordon S. Alternative activation of macrophages. Nat Rev Immunol. 2003;3(1):23–35. doi: 10.1038/nri978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gabrilovich DI, Nagaraj S. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells as regulators of the immune system. Nat Rev Immunol. 2009;9(3):162–174. doi: 10.1038/nri2506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sawanobori Y, Ueha S, Kurachi M, et al. Chemokine-mediated rapid turnover of myeloid-derived suppressor cells in tumor-bearing mice. Blood. 2008;111(12):5457–5466. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-01-136895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Umemura N, Saio M, Suwa T, et al. Tumor-infiltrating myeloid-derived suppressor cells are pleiotropic-inflamed monocytes/macrophages that bear M1- and M2-type characteristics. J Leukoc Biol. 2008;83(5):1136–1144. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0907611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Youn JI, Nagaraj S, Collazo M, et al. Subsets of myeloid-derived suppressor cells in tumor-bearing mice. J Immunol. 2008;181(8):5791–5802. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.8.5791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lin EY, Nguyen AV, Russell RG, et al. Colony-stimulating factor 1 promotes progression of mammary tumors to malignancy. J Exp Med. 2001;193(6):727–740. doi: 10.1084/jem.193.6.727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hamilton JA. Colony-stimulating factors in inflammation and autoimmunity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008;8(7):533–544. doi: 10.1038/nri2356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Paulus P, Stanley ER, Schafer R, et al. Colony-stimulating factor-1 antibody reverses chemoresistance in human MCF-7 breast cancer xenografts. Cancer Res. 2006;66(8):4349–4356. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-3523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eubank TD, Galloway M, Montague CM, et al. M-CSF induces vascular endothelial growth factor production and angiogenic activity from human monocytes. J Immunol. 2003;171(5):2637–2643. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.5.2637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huang B, Pan PY, Li Q, et al. Gr-1+CD115+ immature myeloid suppressor cells mediate the development of tumor-induced T regulatory cells and T-cell anergy in tumor-bearing host. Cancer Res. 2006;66(2):1123–1131. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Movahedi K, Guilliams M, Van den Bossche J, et al. Identification of discrete tumor-induced myeloid-derived suppressor cell subpopulations with distinct T cell-suppressive activity. Blood. 2008;111(8):4233–4244. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-07-099226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Conway JG, McDonald B, Parham J, et al. Inhibition of colony-stimulating-factor-1 signaling in vivo with the orally bioavailable cFMS kinase inhibitor GW2580. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102(44):16078–16083. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0502000102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Karaman MW, Herrgard S, Treiber DK, et al. A quantitative analysis of kinase inhibitor selectivity. Nat Biotechnol. 2008;26(1):127–132. doi: 10.1038/nbt1358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Burton JB, Priceman SJ, Sung JL, et al. Suppression of prostate cancer nodal and systemic metastasis by blockade of the lymphangiogenic axis. Cancer Res. 2008;68(19):7828–7837. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-1488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Van Rooijen N, Sanders A. Liposome mediated depletion of macrophages: mechanism of action, preparation of liposomes and applications. J Immunol Methods. 1994;174(1):83–93. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(94)90012-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Burnett SH, Kershen EJ, Zhang J, et al. Conditional macrophage ablation in transgenic mice expressing a Fas-based suicide gene. J Leukoc Biol. 2004;75(4):612–623. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0903442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brakenhielm E, Burton JB, Johnson M, et al. Modulating metastasis by a lymphangiogenic switch in prostate cancer. Int J Cancer. 2007;121(10):2153–2161. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Aharinejad S, Paulus P, Sioud M, et al. Colony-stimulating factor-1 blockade by antisense oligonucleotides and small interfering RNAs suppresses growth of human mammary tumor xenografts in mice. Cancer Res. 2004;64(15):5378–5384. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-0961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zeisberger SM, Odermatt B, Marty C, et al. Clodronate-liposome-mediated depletion of tumour-associated macrophages: a new and highly effective antiangiogenic therapy approach. Br J Cancer. 2006;95(3):272–281. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shojaei F, Wu X, Malik AK, et al. Tumor refractoriness to anti-VEGF treatment is mediated by CD11b+Gr1+ myeloid cells. Nat Biotechnol. 2007;25(8):911–920. doi: 10.1038/nbt1323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ebos JM, Lee CR, Cruz-Munoz W, et al. Accelerated metastasis after short-term treatment with a potent inhibitor of tumor angiogenesis. Cancer Cell. 2009;15(3):232–239. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.01.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Paez-Ribes M, Allen E, Hudock J, et al. Antiangiogenic therapy elicits malignant progression of tumors to increased local invasion and distant metastasis. Cancer Cell. 2009;15(3):220–231. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.01.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Winkler F, Kozin SV, Tong RT, et al. Kinetics of vascular normalization by VEGFR2 blockade governs brain tumor response to radiation: role of oxygenation, angiopoietin-1, and matrix metalloproteinases. Cancer Cell. 2004;6(6):553–563. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2004.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Casanovas O, Hicklin DJ, Bergers G, et al. Drug resistance by evasion of antiangiogenic targeting of VEGF signaling in late-stage pancreatic islet tumors. Cancer Cell. 2005;8(4):299–309. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fischer C, Jonckx B, Mazzone M, et al. Anti-PlGF inhibits growth of VEGF(R)-inhibitor-resistant tumors without affecting healthy vessels. Cell. 2007;131(3):463–475. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.08.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Eubank TD, Roberts R, Galloway M, et al. GM-CSF induces expression of soluble VEGF receptor-1 from human monocytes and inhibits angiogenesis in mice. Immunity. 2004;21(6):831–842. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2004.10.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Eubank TD, Roberts RD, Khan M, et al. Granulocyte macrophage colony-stimulating factor inhibits breast cancer growth and metastasis by invoking an anti-angiogenic program in tumor-educated macrophages. Cancer Res. 2009;69(5):2133–2140. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-1405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dai XM, Ryan GR, Hapel AJ, et al. Targeted disruption of the mouse colony-stimulating factor 1 receptor gene results in osteopetrosis, mononuclear phagocyte deficiency, increased primitive progenitor cell frequencies, and reproductive defects. Blood. 2002;99(1):111–120. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.1.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang S, Gao J, Lei Q, et al. Prostate-specific deletion of the murine Pten tumor suppressor gene leads to metastatic prostate cancer. Cancer Cell. 2003;4(3):209–221. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(03)00215-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yang L, DeBusk LM, Fukuda K, et al. Expansion of myeloid immune suppressor Gr+CD11b+ cells in tumor-bearing host directly promotes tumor angiogenesis. Cancer Cell. 2004;6(4):409–421. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2004.08.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Folkman J, Merler E, Abernathy C, et al. Isolation of a tumor factor responsible for angiogenesis. J Exp Med. 1971;133(2):275–288. doi: 10.1084/jem.133.2.275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sennino B, Falcon BL, McCauley D, et al. Sequential loss of tumor vessel pericytes and endothelial cells after inhibition of platelet-derived growth factor B by selective aptamer AX102. Cancer Res. 2007;67(15):7358–7367. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-0293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stockmann C, Doedens A, Weidemann A, et al. Deletion of vascular endothelial growth factor in myeloid cells accelerates tumorigenesis. Nature. 2008;456(7223):814–818. doi: 10.1038/nature07445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Daley JM, Thomay AA, Connolly MD, et al. Use of Ly6G-specific monoclonal antibody to deplete neutrophils in mice. J Leukoc Biol. 2008;83(1):64–70. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0407247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Coussens LM, Tinkle CL, Hanahan D, et al. MMP-9 supplied by bone marrow-derived cells contributes to skin carcinogenesis. Cell. 2000;103(3):481–490. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00139-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jodele S, Chantrain CF, Blavier L, et al. The contribution of bone marrow-derived cells to the tumor vasculature in neuroblastoma is matrix metalloproteinase-9 dependent. Cancer Res. 2005;65(8):3200–3208. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-3770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bergers G, Brekken R, McMahon G, et al. Matrix metalloproteinase-9 triggers the angiogenic switch during carcinogenesis. Nat Cell Biol. 2000;2(10):737–744. doi: 10.1038/35036374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lee S, Jilani SM, Nikolova GV, et al. Processing of VEGF-A by matrix metalloproteinases regulates bioavailability and vascular patterning in tumors. J Cell Biol. 2005;169(4):681–691. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200409115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Xu J, Rodriguez D, Petitclerc E, et al. Proteolytic exposure of a cryptic site within collagen type IV is required for angiogenesis and tumor growth in vivo. J Cell Biol. 2001;154(5):1069–1079. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200103111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jain RK. Normalizing tumor vasculature with anti-angiogenic therapy: a new paradigm for combination therapy. Nat Med. 2001;7(9):987–989. doi: 10.1038/nm0901-987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tong RT, Boucher Y, Kozin SV, et al. Vascular normalization by vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2 blockade induces a pressure gradient across the vasculature and improves drug penetration in tumors. Cancer Res. 2004;64(11):3731–3736. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-0074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vosseler S, Mirancea N, Bohlen P, et al. Angiogenesis inhibition by vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-2 blockade reduces stromal matrix metalloproteinase expression, normalizes stromal tissue, and reverts epithelial tumor phenotype in surface heterotransplants. Cancer Res. 2005;65(4):1294–1305. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-03-3986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhang J, Yang PL, Gray NS. Targeting cancer with small molecule kinase inhibitors. Nat Rev Cancer. 2009;9(1):28–39. doi: 10.1038/nrc2559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ko JS, Zea AH, Rini BI, et al. Sunitinib mediates reversal of myeloid-derived suppressor cell accumulation in renal cell carcinoma patients. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15(6):2148–2157. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-1332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]