Abstract

Obstructive sleep apnea syndrome (OSAS) is a serious, prevalent condition that has significant morbidity and mortality when untreated. It is strongly associated with obesity and is characterized by changes in the serum levels or secretory patterns of several hormones. Obese patients with OSAS show a reduction of both spontaneous and stimulated growth hormone (GH) secretion coupled to reduced insulin-like growth factor-I (IGF-I) concentrations and impaired peripheral sensitivity to GH. Hypoxemia and chronic sleep fragmentation could affect the sleep-entrained prolactin (PRL) rhythm. A disrupted Hypothalamus-Pituitary-Adrenal (HPA) axis activity has been described in OSAS. Some derangement in Thyroid-Stimulating Hormone (TSH) secretion has been demonstrated by some authors, whereas a normal thyroid activity has been described by others. Changes of gonadal axis are common in patients with OSAS, who frequently show a hypogonadotropic hypogonadism. Altogether, hormonal abnormalities may be considered as adaptive changes which indicate how a local upper airway dysfunction induces systemic consequences. The understanding of the complex interactions between hormones and OSAS may allow a multi-disciplinary approach to obese patients with this disturbance and lead to an effective management that improves quality of life and prevents associated morbidity or death.

1. Introduction

Obstructive sleep apnea syndrome (OSAS) is an emerging public health problem and is characterized by repetitive upper airway occlusion episodes leading to apnea and asphyxia, typically occurring 100–600 times per night, with arousal being required to reestablish airway patency [1–3].

The most important epidemiological risk factors for sleep apnea are obesity and male gender [2, 4, 5]. OSAS is estimated to affect up to 7% of the adult male population, and its prevalence increases with advancing age, although the clinical severity of apnea decreases [4–6]. The increased risk of sleep apnea in male subjects may be due to differences in airway anatomy, pharyngeal dilator muscle function, and ventilatory control mechanisms [4, 5].

The pathophysiology of OSAS is complex and incompletely understood but is mainly based on an imbalance between the collapsing forces of the upper airway during inspiration and the counteracting forces of the upper airway dilating muscles [7, 8].

The sequence of events in an episode of apnea consists of upper airway constriction, progressive hypoxemia secondary to asphyxia, autonomic and EEG arousal sufficient to prompt one to open and clear the airway to reverse the asphyxia, followed by successive relaxation of the airway, upper airway constriction, and so forth. As the cycle repeats itself throughout the night, the patient's sleep is fragmented [8, 9]. Daytime sleepiness results, along with decreased cognitive performance, decreased quality of life and an increased risk of industrial and motor vehicle accidents [2, 4, 5]. Moreover, OSAS may increase the risk of developing some of the features of the metabolic syndrome, including hypertension, insulin resistance, and type 2 diabetes, leading to adverse cardiovascular consequences such as myocardial infarction and stroke [8, 10–13]. Thus, more than a local abnormality, OSAS should be considered a systemic disease [13].

Because the treatment of OSAS provides many benefits to patients and society, it is very important to obtain an early diagnosis. The diagnosis of OSAS is based on the combination of clinical features and compatible findings on instrumental tests in which multiple physiologic signals are monitored simultaneously during a night of sleep. Polysomnography is routinely indicated for measuring sleep stages and sleep-disordered breathing, for detection of OSAS [14–16]. The severity of OSAS is commonly expressed as the apnea/hypopnea index (AHI), which indicates the frequency of the apnea/hypopnea episodes per hour of sleep [2, 3, 17].

Nasal continuous positive airway pressure (nCPAP) is the initial treatment of choice for most patients because of its noninvasive approach and technical efficacy. It is worn on a nightly basis and acts like a constant pressure air splint to prevent collapse of the upper airway during sleep. nCPAP provides immediate relief of symptoms and has only minor side effects [18]. Nevertheless, an alternative treatment is needed if nCPAP is not feasible for medical or psychological reasons. Removable oral appliances that advance the mandible when fitted to the teeth during sleep also improve nocturnal breathing disturbances, symptoms, quality of life, and vigilance in OSAS patients. However, their long-term effectiveness and side effects require further study [19]. In morbidly obese patients suffering from OSAS bariatric surgery should be considered as a treatment that reduces obesity and at the same time improves OSAS [20]. In selected patients including those with adeno-tonsillar hypertrophy, and craniofacial malformations various surgical techniques that enlarge the upper airway may be a treatment option for OSAS, although the effectiveness in improving OSAS and snoring has been inconsistent and unpredictable [19, 21, 22].

An accumulating body of evidence shows that OSAS induces changes in the serum levels or secretory patterns of several hormones. These changes are not only related to obesity but may be due also to sleep fragmentation induced by apnea and hypopnea, to frequent arousals leading to an increase in stress hormone levels [23], to direct effects of hypoxia on central neurotransmitters with alterations in the hypothalamus-pituitary axes and in the secretion of the peripheral endocrine glands [24], and to the effects of hypercapnia which may increase levels of adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) and adrenal hormones [9, 25]. Finally, the sleep pattern disruption, sleep loss, and naps cause an alteration of hormonal circadian rhythms.

In this review the neuroendocrine changes associated to OSAS in obesity will be revised. Namely, alterations of the growth hormone (GH)/insulin-like growth factor-I (IGF-I), adrenal, thyroid, and gonadal axes will be discussed.

2. Obstructive Sleep Apnea Syndromeand Obesity

Several clinical and epidemiological studies have demonstrated the strict association existing between OSAS and obesity. The incidence of OSAS among morbidly obese patients is 12- to 30-fold higher than in the general population [26]. Body mass index (BMI) has been shown to be the most important risk factor for OSAS, preceding age and male gender. In particular, the android-central type of obesity is strictly associated to OSAS. Neck circumference is the most important predictor of OSAS among obese subjects [4].

Several mechanisms are involved in the association of obesity and OSAS. These include upper airway alterations such as an increased collapsibility of the peripharyngeal tissues. The accumulation of adipose tissue in the neck and also in the pharyngeal structures induces an airway restriction and collapse during inspiration [19, 27]. Abnormalities in the chest wall dynamics, a reduced respiratory compliance, and an impaired respiratory muscle function contribute to the pulmonary dysfunction of severely obese patients [28].

Noteworthy, OSAS itself may predispose individuals to worsening obesity because of sleep deprivation, daytime somnolence, and disrupted metabolism [12, 18].

Weight reduction has been proven effective in reducing the severity of the sleep disturbance, probably through an influence on the upper airways structure and function [20, 29].

It is well known that simple obesity is associated with coronary heart disease (CHD) and is an established marker of cardiovascular risk. Obstructive sleep apnea is an independent risk factor for hypertension [10, 30] and is thought to be a cause of premature death, ischaemic heart disease, and stroke [13]. Moreover, OSAS is connoted by a specific worsening in endocrine and metabolic abnormalities which can account for a further increase in cerebro- and cardiovascular risk [13].

It is also well established that sleep deprivation has an impact on glucose metabolism [8, 11–13, 31]. A growing body of epidemiological evidence supports an association between chronic partial sleep deprivation and the risk for obesity, insulin resistance, and diabetes [31]. Because OSAS is associated with sleep fragmentation, effectively sleep loss, and daytime sleepiness, the insulin sensitivity in patients has been assessed and indeed insulin resistance has been reported [11, 32, 33] (Table 1). That OSAS is an independent risk factor for increased insulin resistance can be learned from improvement in insulin sensitivity after 3 months of treatment with nCPAP [34].

Table 1.

Main hormonal changes in obesity and obstructive sleep apnea syndrome (OSAS).

| OBESITY without OSAS | OBESITY with OSAS | Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|

| GH | ↓ | ↓ ↓ | [46–48] |

| IGF-1 | n or ↓ | ↓ ↓ | [48–50] |

| PRL | ↓ | n or ↑ | [49, 51–53] |

| ACTH | ↑ | ↑ | [51, 54, 55] |

| Cortisol | ↑ | n or ↑ | [49, 53–60] |

| Aldosterone | ↑ | ↑ | [61, 62] |

| fT3 | n | n | [51] |

| fT4 | n | n | [49, 51] |

| TSH | n | n or ↓ | [49, 51, 56, 63] |

| LH | n or ↓ | n or ↓ | [49, 56, 64] |

| FSH | n or ↓ | n or ↓ | [49] |

| Testosterone in ♂ | ↓ | ↓ | [49, 65–68] |

| Free Testosterone in ♂ | n or ↓ | ↓ | [49] |

| Testosterone in ♀ | ↑ | ? | [69, 70] |

| SHBG | ↓ | ↓ | [49] |

| Insulin | ↑ | ↑↑ | [11, 31–33] |

| Leptin | ↑ | ↑↑ | [35, 37–40] |

| Adiponectin | ↓ | ↓ ↓ | [36, 37, 42, 43, 71] |

| Ghrelin | ↓ | ? | [39, 45] |

n: normal; ↑: increased levels; ↓: reduced levels.

Recently, adipocytokines, adipocyte-specific secreted proteins, have been considered to play an important role in the progression of atherosclerotic disease in obesity and in OSAS. Of all adipocytokines, leptin and adiponectin have received the most attention. Despite the antiobesity effect of leptin, obese subjects often have increased serum leptin levels [35]. In contrast, adiponectin levels are decreased in obese individuals and are associated with insulin resistance and hyperinsulinemia [36, 37] (Table 1).

Serum leptin levels have been shown to be positively correlated with the severity of OSAS in obese subjects [37–39], suggesting that leptin is a hormonal factor affected by OSAS. However, Barceló et al. [40] did not observe a leptin decrease in obese OSAS during prolonged nCPAP treatment and recorded only a slight reduction in nonobese OSAS, speculating that the increased leptin levels described so far in patients with OSAS are mostly associated with obesity and not with the disease itself. Similarly, a correlation between adiponectin concentrations and the severity of OSAS have been described by some [41, 42] but not by other authors [37] and nCPAP failed to increase adiponectin concentrations in obese patients with OSAS [43] (Table 1).

Interestingly, apart its antiobesity effects, leptin exerts important physiological effects on the control of respiration and has been suggested to be a better predictor than percent body fat for the presence of hypercapnia in patients with obesity-hypoventilation syndrome [44].

Ghrelin is a hormone that influences appetite and fat accumulation and its physiological effects are opposite to those of leptin. No clear relation has been found between ghrelin and OSAS (Table 1). In a study of 30 obese OSAS patients, plasma ghrelin levels were significantly higher in OSAS patients than in controls and rapidly decreased with nCPAP therapy, suggesting that the elevated ghrelin levels could not have been determined by obesity alone [45]. The appetite stimulating effects of ghrelin may contribute to increased caloric intake and weight gain in patients with OSAS [8]. In a study of 30 untreated obese patients with moderate-severe OSAS, significantly higher levels of serum leptin were found in OSAS patients than in controls, but ghrelin levels presented no such difference [39]. Thus, the relation between OSAS and ghrelin is still an unresolved issue.

3. Neuroendocrine Disturbances in Obstructive Sleep Apnea Syndrome

3.1. GH/IGF-I Axis

OSAS is connoted by a reduced spontaneous GH secretion, which seems to be due to the sleep respiratory disturbance and is restored by nCPAP treatment. Saini et al. [46] have shown that a single night nCPAP treatment is able to increase the duration of slow wave sleep and to normalize GH levels in obese subjects with OSAS. The treatment increases the amplitude but not the frequency of GH secretory bursts. These authors underlined the tight connection between sleep fragmentation and low circulating GH levels in untreated OSAS patients. Since no modification of the concomitant hyperinsulinemia was recorded after nCPAP treatment, they concluded that insulin did not play a role in the pathogenesis of GH reduction in these patients.

Cooper et al. [47] confirmed the effects of nCPAP treatment on GH secretion in obese patients with OSAS and demonstrated an increase of FFA concentrations indicating an increase of GH peripheral lipolytic action.

Reduced IGF-I levels have also been described in obese patients with OSAS [49]. This reduction is greater than in obese subjects without OSAS and is independent of BMI and age. These authors outlined the role of hypoxemia rather than sleep fragmentation in the pathogenesis of hormonal alterations and documented a significant increase in IGF-I levels three months after the initiation of nCPAP treatment.

Ursavas et al. [50] recently demonstrated that the low circulating IGF-I levels in patients with OSAS were negatively correlated with AHI, duration of apnea-hypopnea, arousal index, average desaturation, and oxygen saturation index. These authors have also hypothesized that the negative correlation between obesity and IGF-I levels that was found in previous studies can be related to the presence of OSAS in the majority of obese patients.

We have demonstrated that obese patients with OSAS show an impairment of both basal and stimulated GH secretion [48]. In fact, in obese patients with OSAS we have found basal GH levels similar to those recorded in patients with simple obesity and lower than in normal subjects, with a deeper reduction of the GH response to a provocative test as potent and reproducible as GHRH plus arginine [72]. Interestingly, this impairment occurred in the presence of basal IGF-I levels significantly lower than in simple obesity and not responsive to the short-term administration of a very low recombinant human GH dose. These data support the hypothesis that OSAS per se may impair GH/IGF-I axis activity, independently of adiposity. Accordingly, the reduction of nocturnal GH secretion of overweight patients with OSAS is reversed by nCPAP, before any significant variation in body weight occurs [46, 47]. Moreover, nCPAP has been found able to restore IGF-I levels in OSAS patients independently of body weight variations [49].

The mechanisms controlling sleep and GH secretion are tightly associated [73], and the amplification of somatotroph secretion during sleep, for example, III-IV stages, is well known [74]. Qualitative and quantitative sleep alterations in OSAS have been clearly demonstrated [75] and are improved by nCPAP treatment, together with GH and IGF-I secretion [46, 49]. In particular, slow-wave sleep is specifically and markedly reduced or absent in OSAS [76]. Thus, sleep-related alterations of the neuroendocrine control of GH secretion could also contribute to the peculiar impairment of GH release in obese patients with OSAS.

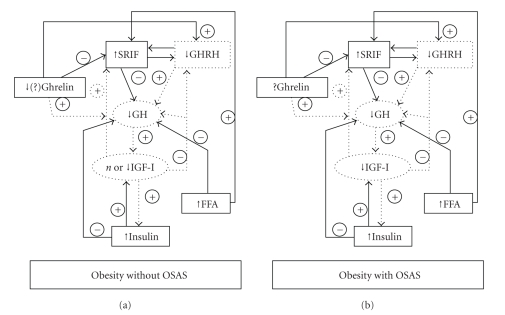

Insulin resistance can be also proposed to explain the impairment of GH/IGF-I axis activity in OSAS. In fact, insulin is able to inhibit GH synthesis and secretion [77] and to enhance GH-induced hepatic IGF-I production [78] (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Regulation of GH secretion in obese patients without OSAS and obese patients with OSAS.

Finally, hypoxia itself might impair both somatotroph function and the peripheral sensitivity to GH. In fact, animal studies have shown that acute as well as prolonged hypoxia reduces GH synthesis and release [71]. Moreover, hypoxia reduces IGF-I mRNA expression in endothelial cells in vitro [79], and low IGF-I levels have been shown in patients with ischemic dilated cardiomyopathy [80].

In conclusion, obese patients with OSAS show a peculiar reduction of both spontaneous and stimulated GH secretion coupled to reduced IGF-I concentrations and impaired peripheral sensitivity to GH. These endocrine abnormalities can be responsible for metabolic alterations, which are common in OSAS and increase the risk of cardiovascular events as well as mortality.

3.2. Prolactin

Plasma prolactin (PRL) concentrations exhibit a sleep-dependent pattern, with highest levels during sleep and lowest levels during the waking period. In human physiology, outside pregnancy, PRL secretion is altered by increasing body weight in both children and adults [81]. PRL in this circumstance appears to be a marker of hypothalamus-pituitary function: the PRL response to insulin-hypoglycaemia, Thyrotropin-Releasing Hormone (TRH) stimulation, and other stimulatory factors may be diminished [81–83]. In addition, obesity alters the 24 hour spontaneous release of PRL with a generalised dampening of release. These alterations seem to be due to obesity per se with its hyperinsulinaemic state as well as an interplay between PRL and leptin concentrations. Weight reduction, with accompanying decrease in plasma insulin levels, leads to a normalization of PRL responses in most, but not all, circumstances [81].

Studies on PRL secretion axis in OSAS provided conflicting results [49, 51, 84]. Hypoxemia and chronic sleep fragmentation in OSAS could affect the sleep-entrained PRL rhythm [52]. PRL secretion is reversibly elevated in an hypoxic stress response and can be a useful marker of acute, severe, illness-induced stress [53]. No correlation of PRL levels with OSAS severity and no changes induced by nCPAP treatment have been described by Grunstein et al. [49] and by Meston et al. [53]. We have found similar basal PRL concentrations as well as PRL response to TRH in obese subjects with OSAS, in obese subjects without OSAS, and in normal lean controls [51]. On the other hand, Spiegel et al. [52] have described a lower PRL pulse frequency in untreated OSAS patients as compared to treated patients and have indicated that nCPAP treatment immediately restores a normal sleep structure and normalizes PRL release by restoring pulse frequency to values similar to those observed in normal subjects.

3.3. Adrenal Axis

A disrupted Hypothalamus-Pituitary-Adrenal (HPA) axis activity has been described in OSAS. Nocturnal awakenings are associated with pulsatile cortisol release [23] and autonomic activation. The latter leads to increased catecholamine release as well as Corticotropin-Releasing Hormone (CRH) and cortisol release. Sleep deprivation itself is associated with HPA axis hyperactivity [85].

The literature varies regarding the effects of OSAS on the HPA system. An enhanced cortisol secretion in patients with OSAS has been reported by some [54, 56, 57] but not by other authors [49, 53, 58, 59]. In a group of obese male patients with OSAS we have found normal adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) and cortisol levels but an ACTH hyper-responsiveness to CRH that, in fact, was even more remarkable than that occurring in nonapneic obese patients [51]. This peculiar ACTH response pattern in obese OSAS patients indicates that factors other than obesity per se have a role in this clinical condition. In fact, a disrupted HPA axis function has been described in patients with abdominal obesity, including both neuroendocrine and peripheral alterations leading to inappropriately higher than normal exposure to cortisol of peripheral tissues, particularly the visceral adipose tissue. The disregulation of the HPA axis in abdominal obesity has been demonstrated also by many dynamic studies showing both a high cortisol secretion after laboratory stress test and a hyper-responsiveness after various provocative stimuli [86]. Altered HPA axis activity in obesity may also derive from a dysruption of the catecholaminergic regulation in the central nervous system, particularly during acute and chronic stress challenges [87].

Hypoxia is likely to directly or indirectly play a critical role in the alteration of the HPA axis activity in OSAS, since it has been shown able to induce HPA axis activation both in animals and in humans [88, 89]. In fact, an hypoxic state is likely to represent a stressful condition that, in turn, could well trigger the HPA axis. Moreover, sleep-related alterations of the neuroendocrine control of anterior pituitary function could contribute to the peculiar alteration of ACTH secretion in obese patients with OSAS.

Several studies have primarily focused on the effects of nCPAP on cortisol. Some authors have reported that nCPAP does not reduce cortisol levels [49] or that acute withdrawal of nCPAP therapy does not result in an increase in cortisol levels [90]. In contrast, other studies have reported that nCPAP does reverse hypercortisolemia [91], particularly with prolonged use [56]. Noteworthy, several of these studies were limited in that cortisol was measured at a single time point, and consequently they do not measure potential clinically important HPA axis and rhythm changes. Vgontzas et al. [55] have demonstrated that sleep apnea in obese men is associated with increased cortisol levels during the night, compared with nonapneic obese controls, which is corrected after the use of nCPAP for 3 months. The correction of the increased cortisol appears to be related to the elimination, through nCPAP, of the stress of repetitive respiratory pausing and sleep fragmentation and/or better oxygen saturation [55]. Finally, Carneiro et al. [60] have recently indicated that men with OSAS present a blunted response of cortisol suppression after dexamethasone, which is recovered after 3 months of nCPAP therapy.

When untreated, this HPA axis hyperactivity in OSAS may be a risk factor for the metabolic syndrome, and also for insomnia and depression, which are both associated with hypercortisolemic states. Similar sleep EEG changes were found in depression and Cushing's disease, and a role for obstructive sleep apnea has been suggested [92].

Several components of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS) are elevated in obese humans [61] and play an important role in the etiology of obesity hypertension [93]. In addition, plasma renin activity declines with weight loss and is correlated with the reduction in blood pressure [94, 95].

To our knowledge, there is a lack of data on the effects of OSAS on the mineralocorticoid axis, although hypertension is common in OSAS patients and may result from prolonged repetitive stimulation of the renin-aldosterone axis [96]. Moreover, it is well recognized that renin is elevated in response to systemic illness [97]. However, Meston et al. [53] did not find a relationship between OSAS severity and aldosterone or renin levels in overweight and obese OSAS patients. A recent report demonstrated that elevated aldosterone is a cause of hypertension in OSAS, but the cause of hyperaldosteronism was unknown [62]. Since ACTH stimulates both aldosterone and cortisol synthesis and secretion, it has been hypothesized that the HPA axis hyperactivity from OSAS may increase aldosterone and thereby contribute to hypertension [9]. This same mechanism has been proposed for explaining hypertension in depression [98].

3.4. Thyroid Axis

A link between OSAS and hypothyroidism is suggested by the high prevalence of sleep apnea among hypothyroid patients, particularly in rare myxoedematous patients [99, 100]. The increased prevalence of OSAS appears to be related to obesity and male sex rather than to hypothyroidism per se [101]. However, decreased ventilatory responses [102], extravasation of albumin and mucopolysaccharides in the tissues of the upper airway [103, 104], and hypothyroid myopathy [99] have been suggested as possible contributing factors for OSAS in hypothyroidism.

In patients with OSAS, the prevalence of hypothyroidism is 1%–3% [100, 105], which is not different from that in the general population.

In a group of obese patients with OSAS we have not found an impaired thyroid activity in basal conditions nor an altered TSH response to TRH challenge test [51], in agreement with some but not other studies. In fact, some derangement in TSH secretion in obesity with or without OSAS has been demonstrated [49, 56, 106].

As with other forms of systemic illness, suppression of thyroid responsiveness occurs during the development of OSAS with reversal of these changes during treatment [63]. Bratel et al. [56] have reported a more pronounced reduction of serum TSH in OSAS patients with the most severe nocturnal hypoxemia, with a normal TSH response to TRH before and after nCPAP treatment. However, TSH levels decreased even further after 7 months of nCPAP therapy [56]. In 101 overweight and obese male patients, Meston et al. [53] have described a small significant inverse correlation between OSAS and free T4 levels but not TSH, with no apparent association between obesity and either hormone. One-month nCPAP treatment compared to placebo resulted in a significant reduction in TSH without elevation in free T4 levels, consistent with the pattern of recovery from non-thyroidal illness.

Biochemical screening for hypothyroidism in patients with OSAS is not considered necessary by many authors unless the patient is symptomatic or belongs to a risk group [105, 107, 108]. However, given the overlap in clinical presentation of primary OSAS and hypothyroidism, some authors indicate that screening for hypothyroidism is required to prevent misdiagnosis and that it is a cost-effective component of the investigation of sleep apnea [109].

Contrasting data are available concerning the efficacy of thyroid replacement therapy in improving sleep apnea in patients with clinical hypothyroidism. Some authors describe a prompt reversal of symptoms, sleep-disordered breathing, and nocturnal hypoxia [109] while little or no improvement in sleep apnea is reported by others [108].

3.5. Gonadal Axis

Among endocrine disturbances, changes of gonadal axis are common in patients with OSAS, who frequently show a hypogonadotropic hypogonadism likely due to alterations of the hypothalamic-pituitary control of gonadotropin synthesis and release. In particular, decreased morning and nocturnal testosterone concentrations have been found in lean and obese male patients with OSAS [49, 64–66] with an increase after uvulopalatal resection [65] or normalization after nCPAP treatment [49, 67]. Changes in sleep efficiency and architecture have been associated with alteration in pituitary-gonadal function in healthy older men [110, 111]. In young adults, the sleep-related rise in testosterone has been linked with the first rapid eye movement (REM) sleep episode and has been shown to be dependent on the integrity of the sleep process [112].

Gonadotropin levels have been found reduced both basally and after gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) stimulation but only partially reverted by hypoxia correction [49, 53]. Reduced Sex Hormone-Binding Globulin (SHBG) concentrations coupled to low testosterone levels and correlating to OSAS severity support a diagnosis of secondary hypogonadism [49, 53]. SHBG levels have been reported to rise during active nCPAP treatment [49, 53].

A significant correlation between LH/testosterone profiles and the severity of OSAS is described, thus suggesting that sleep fragmentation and hypoxia in addition to the degree of obesity may be responsible for the central suppression of testosterone in these patients. Moreover, testosterone concentrations fall with prolonged physical stress, sleep deprivation, and sleep fragmentation in normal young and elderly males [111–113]. Finally, hypoxia decreases LH and testosterone levels and alters circadian rhythm of testosterone secretion [24, 68, 114]. It has also been hypothesized that decreased testosterone levels may be part of an adaptive homeostatic mechanism to reduce sleep disordered breathing assuming that testosterone aggravates it [49, 115]. In fact, androgen levels can directly influence the prevalence and severity of sleep-disordered breathing and some reports have demonstrated that administration of exogenous androgens to both men and women can induce or precipitate apnea [116, 117]. However, few studies have systematically evaluated the effects of exogenous androgen replacement therapy on OSAS. Testosterone replacement therapy induced OSAS in one of five males and aggravated a preexisting sleep disordered breathing in another [117]. In 11 hypogonadal males, testosterone replacement increased apneic events but only in three subjects was the increase considered statistically significant [118]. In a placebo-controlled study of 17 overweight elderly males with partial androgen deficiency, testosterone replacement therapy decreased total sleep time and sleep efficiency and aggravated sleep apnea [119].

The few available data from females with sleep disordered breathing support the link with androgens. Irrespective of the menopausal state, obese females have higher androgen levels than nonobese females [69, 70]. In a lean, 70-year-old woman, a testosterone producing tumour caused sleep apnea, which disappeared after removal of the tumour [120].

Female hormones are thought to protect women from OSAS until menopause [121]. In clinical studies, male : female ratio of OSAS is ~10 : 1 [4, 122]. Among females referred to a sleep clinic, 47% of the postmenopausal and 21% of the premenopausal females had sleep apnea [123]. In a large community-based study, 1.9% of postmenopausal females and 0.6% of premenopausal females had OSAS, defined as AHI ≥10 and occurrence of daytime symptoms [6].

Menopause-related changes in body fat distribution, from gynoid phenotype to android features, may include deposition of fat around the upper airway [124]. The effect of menopause on body fat distribution is ascribed to declining levels of estrogen and progesterone and appears to be reversed or attenuated by the use of replacement hormones [125]. Declining levels of these hormones might also predispose some women to sleep-disordered breathing by lowering the ventilatory drive to the upper airway, leading to an imbalance between the collapsing forces of the upper airway during inspiration and the counteracting forces of the upper airway dilating muscles.

4. Conclusions

OSAS is a serious, prevalent condition which is strongly associated with obesity and has significant mortality and morbidity when untreated. Sleep fragmentation and hypoxia are likely to play a prevalent role in causing cardiovascular alterations that increase morbidity and mortality in comparison with simple obesity. The same factors can also be responsible for the endocrine abnormalities in OSAS that are frequently more marked than those in nonapneic obese patients. These abnormalities may be considered as adaptive changes which indicate how a local upper airway dysfunction induces systemic consequences. On the other hand, the same abnormalities can also contribute to the maintenance or progression of OSAS itself.

The recognition and understanding of the complex interactions between hormones and OSAS may allow a multidisciplinary approach to obese patients with this disturbance. Effective assessment and management of OSAS in obesity may correct endocrine changes, improve quality of life, and prevent associated morbidity or death.

References

- 1.Sullivan CE, Issa FC. Pathophysiological mechanism in obstructive sleep apnea. Sleep. 1980;3:235–246. doi: 10.1093/sleep/3.3-4.235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Flemons WW, Buysse D, Redline S, et al. Sleep-related breathing disorders in adults: recommendations for syndrome definition and measurement techniques in clinical research. The Report of an American Academy of Sleep Medicine Task Force. Sleep. 1999;22(5):667–689. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Iber C, Ancoli-Israel S, Chesson A, Quan S. The AASM Manual for the Scoring of Sleep and Associated Events: Rules, Terminology and Technical Specifications. 1st edition. Westchester, Ill, USA: American Academy of Sleep Medicine; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Guilleminault C, van den Hoed J, Mitler M. Clinical features and evaluation of obstructive sleep apnea. In: Kryger MH, Roth T, Dement WC, editors. Principles and Practice of Sleep Medicine. Vol. 65. Philadelphia, Pa, USA: W.B. Saunders; 1994. pp. 667–677. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bixler EO, Vgontzas AN, Ten Have T, Tyson K, Kales A. Effects of age on sleep apnea in men. I. Prevalence and severity. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 1998;157(1):144–148. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.157.1.9706079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bixler EO, Vgontzas AN, Lin H-M, et al. Prevalence of sleep-disordered breathing in women: effects of gender. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 2001;163(3):608–613. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.163.3.9911064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Malhotra A, White DP. Obstructive sleep apnoea. The Lancet. 2002;360(9328):237–245. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)09464-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pillar G, Shehadeh N. Abdominal fat and sleep apnea: the chicken or the egg? Diabetes Care. 2008;31(supplement 2):S303–S309. doi: 10.2337/dc08-0715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Buckley TM, Schatzberg AF. On the interactions of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis and sleep: normal HPA axis activity and circadian rhythm, exemplary sleep disorders. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2005;90(5):3106–3114. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-1056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Peppard PE, Young T, Palta M, Skatrud J. Prospective study of the association between sleep-disordered breathing and hypertension. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2000;342(19):1378–1384. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200005113421901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vgontzas AN, Papanicolaou DA, Bixler EO, et al. Sleep apnea and daytime sleepiness and fatigue: relation to visceral obesity, insulin resistance, and hypercytokinemia. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2000;85(3):1151–1158. doi: 10.1210/jcem.85.3.6484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Svatikova A, Wolk R, Gami AS, Pohanka M, Somers VK. Interactions between obstructive sleep apnea and the metabolic syndrome. Current Diabetes Reports. 2005;5(1):53–58. doi: 10.1007/s11892-005-0068-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zamarron C, García Paz V, Riveiro A. Obstructive sleep apnea syndrome is a systemic disease. Current evidence. European Journal of Internal Medicine. 2008;19(6):390–398. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2007.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chesson AL, Jr., Berry RB, Pack A. Practice parameters for the use of portable monitoring devices in the investigation of suspected obstructive sleep apnea in adults. Sleep. 2003;26(7):907–913. doi: 10.1093/sleep/26.7.907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mattei A, Tabbia G, Baldi S. Diagnosis of sleep apnea. Minerva Medica. 2004;95(3):213–231. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Collop NA, Anderson WM, Boehlecke B, et al. Clinical guidelines for the use of unattended portable monitors in the diagnosis of obstructive sleep apnea in adult patients. Portable Monitoring Task Force of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine. Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine. 2007;3(7):737–747. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Littner M. Polysomnography in the diagnosis of the obstructive sleep apnea-hypopnea syndrome: where do we draw the line? Chest. 2000;118(2):286–288. doi: 10.1378/chest.118.2.286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gami AS, Caples SM, Somers VK. Obesity and obstructive sleep apnea. Endocrinology and Metabolism Clinics of North America. 2003;32(4):869–894. doi: 10.1016/s0889-8529(03)00069-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bloch KE. Alternatives to CPAP in the treatment of the obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Swiss Medical Weekly. 2006;136(17-18):261–267. doi: 10.4414/smw.2006.11158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Buchwald H, Avidor Y, Braunwald E, et al. Bariatric surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2004;292(14):1724–1737. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.14.1724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Phillips B. Upper airway surgery does not have a major role in the treatment of sleep apnea. Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine. 2005;1(3):241–245. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Powell NB. Contemporary surgery for obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Clinical and Experimental Otorhinolaryngology. 2009;2(3):107–114. doi: 10.3342/ceo.2009.2.3.107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ekstedt M, Åkerstedt T, Söderström M. Microarousals during sleep are associated with increased levels of lipids, cortisol, and blood pressure. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2004;66(6):925–931. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000145821.25453.f7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Semple PD, Beastall GH, Watson WS, Hume R. Hypothalamic-pituitary dysfunction in respiratory hypoxia. Thorax. 1981;36(8):605–609. doi: 10.1136/thx.36.8.605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Raff H, Shinsako J, Keil LC, Dallman MF. Vasopressin, ACTH, and corticosteroids during hypercapnia and graded hypoxia in dogs. The American Journal of Physiology. 1983;244(5):E453–E458. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1983.244.5.E453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Young T, Peppard PE, Taheri S. Excess weight and sleep-disordered breathing. Journal of Applied Physiology. 2005;99(4):1592–1599. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00587.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Davies RJO, Ali NJ, Stradling JR. Neck circumference and other clinical features in the diagnosis of the obstructive sleep apnoea syndrome. Thorax. 1992;47(2):101–105. doi: 10.1136/thx.47.2.101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rubinstein I, Hoffstein V, Bradley TD. Lung volume-related changes in the pharyngeal area of obese females with and without obstructive sleep apnoea. European Respiratory Journal. 1989;2(4):344–351. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schwartz AR, Gold AR, Schubert N, et al. Effect of weight loss on upper airway collapsibility in obstructive sleep apnea. American Review of Respiratory Disease. 1991;144(3):494–498. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/144.3_Pt_1.494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lavie P, Herer P, Hoffstein V. Obstructive sleep apnoea syndrome as a risk factor for hypertension: population study. British Medical Journal. 2000;320(7233):479–482. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7233.479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Spiegel K, Knutson K, Leproult R, Tasali E, Van Cauter E. Sleep loss: a novel risk factor for insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes. Journal of Applied Physiology. 2005;99(5):2008–2019. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00660.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vgontzas AN, Bixler EO, Chrousos GP. Metabolic disturbances in obesity versus sleep apnoea: the importance of visceral obesity and insulin resistance. Journal of Internal Medicine. 2003;254(1):32–44. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2796.2003.01177.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tassone F, Lanfranco F, Gianotti L, et al. Obstructive sleep apnoea syndrome impairs insulin sensitivity independently of anthropometric variables. Clinical Endocrinology. 2003;59(3):374–379. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2265.2003.01859.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Harsch IA, Schahin SP, Brückner K, et al. The effect of continuous positive airway pressure treatment on insulin sensitivity in patients with obstructive sleep apnoea syndrome and type 2 diabetes. Respiration. 2004;71(3):252–259. doi: 10.1159/000077423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Considine RV, Sinha MK, Heiman ML, et al. Serum immunoreactive-leptin concentrations in normal-weight and obese humans. The New England Journal of Medicine. 1996;334(5):292–295. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199602013340503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Arita Y, Kihara S, Ouchi N, et al. Paradoxical decrease of an adipose-specific protein, adiponectin, in obesity. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 1999;257(1):79–83. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1999.0255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tokuda F, Sando Y, Matsui H, Koike H, Yokoyama T. Serum levels of adipocytokines, adiponectin and leptin, in patients with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Internal Medicine. 2008;47(21):1843–1849. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.47.1035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Marik PE. Leptin, obesity, and obstructive sleep apnea. Chest. 2000;118(3):569–571. doi: 10.1378/chest.118.3.569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ulukavak Ciftci T, Kokturk O, Bukan N, Bilgihan A. Leptin and ghrelin levels in patients with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Respiration. 2005;72(4):395–401. doi: 10.1159/000086254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Barceló A, Barbé F, Llompart E, et al. Neuropeptide Y and leptin in patients with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome: role of obesity. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 2005;171(2):183–187. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200405-579OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhang X-L, Yin K-S, Wang H, Su S. Serum adiponectin levels in adult male patients with obstructive sleep apnea hypopnea syndrome. Respiration. 2006;73(1):73–77. doi: 10.1159/000088690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Makino S, Handa H, Suzukawa K, et al. Obstructive sleep apnoea syndrome, plasma adiponectin levels, and insulin resistance. Clinical Endocrinology. 2006;64(1):12–19. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2005.02407.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Harsch IA, Wallaschofski H, Koebnick C, et al. Adiponectin in patients with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome: course and physiological relevance. Respiration. 2004;71(6):580–586. doi: 10.1159/000081758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Phipps PR, Starritt E, Caterson I, Grunstein RR. Association of serum leptin with hypoventilation in human obesity. Thorax. 2002;57(1):75–76. doi: 10.1136/thorax.57.1.75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Harsch IA, Konturek PC, Koebnick C, et al. Leptin and ghrelin levels in patients with obstructive sleep apnoea: effect of CPAP treatment. European Respiratory Journal. 2003;22(2):251–257. doi: 10.1183/09031936.03.00010103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Saini J, Krieger J, Brandenberger G, Wittersheim G, Simon C, Follenius M. Continuous positive airway pressure treatment. Effects on growth hormone, insulin and glucose profiles in obstructive sleep apnea patients. Hormone and Metabolic Research. 1993;25(7):375–381. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1002123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cooper BG, White JES, Ashworth LA, Alberti KGMM, Gibson GJ. Hormonal and metabolic profiles in subjects with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome and the acute effects of nasal continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) treatment. Sleep. 1995;18(3):172–179. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gianotti L, Pivetti S, Lanfranco F, et al. Concomitant impairment of growth hormone secretion and peripheral sensitivity in obese patients with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2002;87(11):5052–5057. doi: 10.1210/jc.2001-011441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Grunstein RR, Handelsman DJ, Lawrence SJ, Blackwell C, Caterson ID, Sullivan CE. Neuroendocrine dysfunction in sleep apnea: reversal by continuous positive airways pressure therapy. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 1989;68(2):352–358. doi: 10.1210/jcem-68-2-352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ursavas A, Karadag M, Ilcol YO, et al. Low level of IGF-1 in obesity may be related to obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Lung. 2007;185(5):309–314. doi: 10.1007/s00408-007-9026-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lanfranco F, Gianotti L, Pivetti S, et al. Obese patients with obstructive sleep apnoea syndrome show a peculiar alteration of the corticotroph but not of the thyrotroph and lactotroph function. Clinical Endocrinology. 2004;60(1):41–48. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2004.01938.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Spiegel K, Follenius M, Krieger J, Sforza E, Brandenberger G. Prolactin secretion during sleep in obstructive sleep apnoea patients. Journal of Sleep Research. 1995;4(1):56–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2869.1995.tb00151.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Meston N, Davies RJO, Mullins R, Jenkinson C, Wass JAH, Stradling JR. Endocrine effects of nasal continuous positive airway pressure in male patients with obstructive sleep apnoea. Journal of Internal Medicine. 2003;254(5):447–454. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2796.2003.01212.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rapoport D, Rothenburg SA, Hollander CS, Goldring RM. Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) alters ultradian rhythm of ACTH secretion. American Review of Respiratory Diseases. 1989;139:p. A80. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Vgontzas AN, Pejovic S, Zoumakis E, et al. Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis activity in obese men with and without sleep apnea: effects of continuous positive airway pressure therapy. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2007;92(11):4199–4207. doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-0774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bratel T, Wennlund A, Carlström K. Pituitary reactivity, androgens and catecholamines in obstructive sleep apnoea. Effects of continuous positive airway pressure treatment (CPAP) Respiratory Medicine. 1999;93(1):1–7. doi: 10.1016/s0954-6111(99)90068-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Schmoller A, Eberhardt F, Jauch-Chara K, et al. Continuous positive airway pressure therapy decreases evening cortisol concentrations in patients with severe obstructive sleep apnea. Metabolism. 2009;58(6):848–853. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2009.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Entzian P, Linnemann K, Schlaak M, Zabel P. Obstructive sleep apnea syndrome and circadian rhythms of hormones and cytokines. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 1996;153(3):1080–1086. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.153.3.8630548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Dadoun F, Darmon P, Achard V, et al. Effect of sleep apnea syndrome on the circadian profile of cortisol in obese men. American Journal of Physiology. 2007;293(2):E466–E474. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00126.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Carneiro G, Togeiro SM, Hayashi LF, et al. Effect of continuous positive airway pressure therapy on hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis function and 24-h blood pressure profile in obese men with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. American Journal of Physiology. 2008;295(2):E380–E384. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00780.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Umemura S, Nyui N, Tamura K, et al. Plasma angiotensinogen concentrations in obese patients. American Journal of Hypertension. 1997;10(6):629–633. doi: 10.1016/s0895-7061(97)00053-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Goodfriend TL, Calhoun DA. Resistant hypertension, obesity, sleep apnea, and aldosterone: theory and therapy. Hypertension. 2004;43(3):518–524. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000116223.97436.e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Grunstein R. Endocrine and metabolic disturbances in obstructive sleep apnea. In: Saunders NA, Sullivan CE, editors. Sleep and Breathing: Lung Biology in Health and Disease. New York, NY, USA: Dekker; 1994. pp. 449–489. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Luboshitzky R, Aviv A, Hefetz A, Herer P, Shen-Orr Z, Lavie L, Lavie P. Decreased pituitary-gonadal secretion in men with obstructive sleep apnea. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2002;87(7):3394–3398. doi: 10.1210/jcem.87.7.8663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Santamaria JD, Prior JC, Fleetham JA. Reversible reproductive dysfunction in men with obstructive sleep apnoea. Clinical Endocrinology. 1988;28(5):461–470. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.1988.tb03680.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Luboshitzky R, Lavie L, Shen-Orr Z, Herer P. Altered luteinizing hormone and testosterone secretion in middle-aged obese men with obstructive sleep apnea. Obesity Research. 2005;13(4):780–786. doi: 10.1038/oby.2005.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Yee B, Liu P, Philips C, Grunstein R. Neuroendocrine changes in sleep apnea. Current Opinion in Pulmonary Medicine. 2004;10(6):475–481. doi: 10.1097/01.mcp.0000143967.34079.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Gambineri A, Pelusi C, Pasquali R. Testosterone levels in obese male patients with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome: relation to oxygen desaturation, body weight, fat distribution and the metabolic parameters. Journal of Endocrinological Investigation. 2003;26(6):493–498. doi: 10.1007/BF03345209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Goodman-Gruen D, Barrett-Connor E. Total but not bioavailable testosterone is a predictor of central adiposity in postmenopausal women. International Journal of Obesity. 1995;19(5):293–298. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Mantzoros CS, Georgiadis EI, Evangelopoulou K, Katsilambros N. Dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate and testosterone are independently associated with body fat distribution in premenopausal women. Epidemiology. 1996;7(5):513–516. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Zhang Y-S, Du J-Z. The response of growth hormone and prolactin of rats to hypoxia. Neuroscience Letters. 2000;279(3):137–140. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(99)00968-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ghigo E, Aimaretti G, Arvat E, Camanni F. Growth hormone-releasing hormone combined with arginine or growth hormone secretagogues for the diagnosis of growth hormone deficiency in adults. Endocrine. 2001;15(1):29–38. doi: 10.1385/ENDO:15:1:029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Van Cauter E, Latta F, Nedeltcheva A, et al. Reciprocal interactions between the GH axis and sleep. Growth Hormone and IGF Research. 2004;14:S10–S17. doi: 10.1016/j.ghir.2004.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Parker DC, Sassin JF, Mace JW, Gotlin RW, Rossman LG. Human growth hormone release during sleep: electroencephalographic correlation. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 1969;29(6):871–874. doi: 10.1210/jcem-29-6-871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Bradley TD, Phillipson EA. Pathogenesis and pathophysiology of the obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Medical Clinics of North America. 1985;69(6):1169–1185. doi: 10.1016/s0025-7125(16)30981-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Krieger J. Sleep apnoea syndromes in adults. Bulletin Europeen de Physiopathologie Respiratoire . 1986;22(2):147–189. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Melmed S. Insulin suppresses growth hormone secretion by rat pituitary cells. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 1984;73(5):1425–1433. doi: 10.1172/JCI111347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Houston B, O’Neill IE. Insulin and growth hormone act synergistically to stimulate insulin-like growth factor-I production by cultured chicken hepatocytes. Journal of Endocrinology. 1991;128(3):389–393. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1280389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Tucci M, Nygard K, Tanswell BV, Farber HW, Hill DJ, Han VKM. Modulation of insulin-like growth factor (IGF) and IGF binding protein biosynthesis by hypoxia in cultured vascular endothelial cells. Journal of Endocrinology. 1998;157(1):13–24. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1570013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Broglio F, Fubinl A, Morello M, et al. Activity of GH/IGF-I axis in patients with dilated cardiomyopathy. Clinical Endocrinology. 1999;50(4):417–430. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2265.1999.00696.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Kopelman PG. Physiopathology of prolactin secretion in obesity. International Journal of Obesity. 2000;24(supplement 2):S104–S108. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Cavagnini F, Maraschini C, Pinto M, Dubini A, Polli EE. Impaired prolactin secretion in obese patients. Journal of Endocrinological Investigation. 1981;4(2):149–163. doi: 10.1007/BF03350443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Weaver JU, Noonan K, Kopelman PG, Coste M. Impaired prolactin secretion and body fat distribution in obesity. Clinical Endocrinology. 1990;32(5):641–646. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.1990.tb00908.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Clark RW, Schmidt HS, Malarkey WB. Disordered growth hormone and prolactin secretion in primary disorders of sleep. Neurology. 1979;29(6):855–861. doi: 10.1212/wnl.29.6.855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Spiegel K, Leproult R, Van Cauter E. Impact of sleep debt on metabolic and endocrine function. The Lancet. 1999;354(9188):1435–1439. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)01376-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Pasquali R, Vicennati V, Gambineri A. Adrenal and gonadal function in obesity. Journal of Endocrinological Investigation. 2002;25(10):893–898. doi: 10.1007/BF03344053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Rosmond R, Dallman MF, Björntorp P. Stress-related cortisol secretion in men: relationships with abdominal obesity and endocrine, metabolic and hemodynamic abnormalities. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 1998;83(6):1853–1859. doi: 10.1210/jcem.83.6.4843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Raff H, Tzankoff SP, Fitzgerald RS. ACTH and cortisol responses to hypoxia in dogs. Journal of Applied Physiology. 1981;51(5):1257–1260. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1981.51.5.1257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Basu M, Sawhney RC, Kumar S, Pal K, Prasad R, Selvamurthy W. Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis following glucocorticoid prophylaxis against acute mountain sickness. Hormone and Metabolic Research. 2002;34(6):318–324. doi: 10.1055/s-2002-33260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Grunstein RR, Stewart DA, Lloyd H, Akinci M, Cheng N, Sullivan CE. Acute withdrawal of nasal CPAP in obstructive sleep apnea does not cause a rise in stress hormones. Sleep. 1996;19(10):774–782. doi: 10.1093/sleep/19.10.774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Cahan C, Arafah B, Decker MJ, Arnold JL, Strohl KP. Adrenal steroids in sleep apnea before and after nCPAP treatment. American Review of Respiratory Disease. 1991;143:p. A382. [Google Scholar]

- 92.Kaplan R. Obstructive sleep apnoea and depression: diagnostic and treatment implications. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 1992;26(4):586–591. doi: 10.3109/00048679209072093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Hall JE. The kidney, hypertension, and obesity. Hypertension. 2003;41(3):625–633. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000052314.95497.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Sowers JR, Nyby M, Stern N, et al. Blood pressure and hormone changes associated with weight reduction in the obese. Hypertension. 1982;4(5):686–691. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.4.5.686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Grossman E, Eshkol A, Rosenthal T. Diet and weight loss: their effect on norepinephrine renin and aldosterone levels. International Journal of Obesity. 1985;9(2):107–114. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Fletcher EC, Orolinova N, Bader M. Blood pressure response to chronic episodic hypoxia: the renin-angiotensin system. Journal of Applied Physiology. 2002;92(2):627–633. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00152.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Fallo F. Renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system and physical exercise. Journal of Sports Medicine and Physical Fitness. 1993;33(3):306–312. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Murck H, Held K, Ziegenbein M, Künzel H, Koch K, Steiger A. The Renin-Angiotensin-Aldosterone system in patients with depression compared to controls—a sleep endocrine study. BMC Psychiatry. 2003;3, article 15 doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-3-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Grunstein RR, Sullivan CE. Sleep apnea and hypothyroidism: mechanisms and management. American Journal of Medicine. 1988;85(6):775–779. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(88)80020-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Lin C-C, Tsan K-W, Chen P-J. The relationship between sleep apnea syndrome and hypothyroidism. Chest. 1992;102(6):1663–1667. doi: 10.1378/chest.102.6.1663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Pelttari L, Rauhala E, Polo O, et al. Upper airway obstruction in hypothyroidism. Journal of Internal Medicine. 1994;236(2):177–181. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.1994.tb01280.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Zwillich CW, Pierson DJ, Hofeldt FD, Lufkin EG, Weil JV. Ventilatory control in myxedema and hypothyroidism. The New England Journal of Medicine. 1975;292(13):662–665. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197503272921302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Parving HH, Hansen JM, Nielsen SL, Rossing N, Munck O, Lassen NA. Mechanisms of edema formation in myxedema—increased protein extravasation and relatively slow lymphatic drainage. The New England Journal of Medicine. 1979;301(9):460–465. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197908303010902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Orr WC, Males JL, Imes NK. Myxedema and obstructive sleep apnea. American Journal of Medicine. 1981;70(5):1061–1066. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(81)90867-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Kapur VK, Koepsell TD, deMaine J, Hert R, Sandblom RE, Psaty BM. Association of hypothyroidism and obstructive sleep apnea. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 1998;158(5):1379–1383. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.158.5.9712069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Chomard P, Vernhes G, Autissier N, Debry G. Serum concentrations of total T4, T3, reverse T3 and free T4, T3 in moderately obese patients. Human Nutrition: Clinical Nutrition. 1985;39(5):371–378. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Winkelman JW, Goldman H, Piscatelli N, Lukas SE, Dorsey CM, Cunningham S. Are thyroid function tests necessary in patients with suspected sleep apnea? Sleep. 1996;19(10):790–793. doi: 10.1093/sleep/19.10.790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Mickelson SA, Lian T, Rosenthal L. Thyroid testing and thyroid hormone replacement in patients with sleep disordered breathing. Ear, Nose and Throat Journal. 1999;78(10):768–775. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Skjodt NM, Atkar R, Easton PA. Screening for hypothyroidism in sleep apnea. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 1999;160(2):732–735. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.160.2.9802051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Schiavi RC, White D, Mandeli J. Pituitary-gonadal function during sleep in healthy aging men. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 1992;17(6):599–609. doi: 10.1016/0306-4530(92)90018-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Penev PD. Association between sleep and morning testosterone levels in older men. Sleep. 2007;30(4):427–432. doi: 10.1093/sleep/30.4.427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Luboshitzky R, Zabari Z, Shen-Orr Z, Herer P, Lavie P. Disruption of the nocturnal testosterone rhythm by sleep fragmentation in normal men. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2001;86(3):1134–1139. doi: 10.1210/jcem.86.3.7296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Elman I, Breier A. Effects of acute metabolic stress on plasma progesterone and testosterone in male subjects: relationship to pituitary-adrenocortical axis activation. Life Sciences. 1997;61(17):1705–1712. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(97)00776-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Kouchiyama S, Honda Y, Kuriyama T. Influence of nocturnal oxygen desaturation on circadian rhythm of testosterone secretion. Respiration. 1990;57(6):359–363. doi: 10.1159/000195872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Saaresranta T, Polo O. Sleep-disordered breathing and hormones. European Respiratory Journal. 2003;22(1):161–172. doi: 10.1183/09031936.03.00062403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Sandblom RE, Matsumoto AM, Schoene RB, et al. Obstructive sleep apnea syndrome induced by testosterone administration. The New England Journal of Medicine. 1983;308(9):508–510. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198303033080908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Matsumoto AM, Sandblom RE, Schoene RB, et al. Testosterone replacement in hypogonadal men: effects on obstructive sleep apnoea, respiratory drives, and sleep. Clinical Endocrinology. 1985;22(6):713–721. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.1985.tb00161.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Schneider BK, Pickett CK, Zwillich CW, et al. Influence of testosterone on breathing during sleep. Journal of Applied Physiology. 1986;61(2):618–623. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1986.61.2.618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Liu PY, Yee B, Wishart SM, et al. The short-term effects of high-dose testosterone on sleep, breathing, and function in older men. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2003;88(8):3605–3613. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-030236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Dexter BD, Dovre EJ. Obstructive sleep apnea due to endogenous testosterone production in a woman. Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 1998;73(3):246–248. doi: 10.4065/73.3.246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Block AJ, Wynne JW, Boysen PG. Sleep-disordered breathing and nocturnal oxygen desaturation in postmenopausal women. American Journal of Medicine. 1980;69(1):75–79. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(80)90502-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Vgontzas AN, Tan TL, Bixler EO, Martin LF, Shubert D, Kales A. Sleep apnea and sleep disruption in obese patients. Archives of Internal Medicine. 1994;154(15):1705–1711. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Dancey DR, Hanly PJ, Soong C, Lee B, Hoffstein V. Impact of menopause on the prevalence and severity of sleep apnea. Chest. 2001;120(1):151–155. doi: 10.1378/chest.120.1.151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Shahar E, Redline S, Young T, et al. Hormone replacement therapy and sleep-disordered breathing. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 2003;167(9):1186–1192. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200210-1238OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Gambacciani M, Ciaponi M, Cappagli B, De Simone L, Orlandi R, Genazzani AR. Prospective evaluation of body weight and body fat distribution in early postmenopausal women with and without hormonal replacement therapy. Maturitas. 2001;39(2):125–132. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5122(01)00194-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]