Abstract

Differences in sensory function between young (n = 42, 18–31 years old) and older (n = 137, 60–88 years old) adults were examined for auditory, visual, and tactile measures of threshold sensitivity and temporal acuity (gap-detection threshold). For all but one of the psychophysical measures (visual gap detection), multiple measures were obtained at different stimulus frequencies for each modality and task. This resulted in a total of 14 dependent measures, each based on four to six adaptive psychophysical estimates of 75% correct performance. In addition, all participants completed the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale (Wechsler, 1997). Mean data confirmed previously observed differences in performance between young and older adults for 13 of the 14 dependent measures (all but visual threshold at a flicker frequency of 4 Hz). Correlational and principal-components factor analyses performed on the data from the 137 older adults were generally consistent with task and modality independence of the psychophysical measures.

Millions of older Americans have concurrent deficits in hearing and vision, the two most frequently studied senses in large-scale studies of older adults, with prevalence rates for comorbidity of visual and auditory impairments estimated at 7%–12% among older adults (e.g., Campbell, Crews, Moriarty, Zack, & Blackman, 1999; Klein, Cruickshanks, Klein, Nondahl, & Wiley, 1998). For each of these sensory modalities considered independently, age-related decline in threshold sensitivity has been well established (e.g., International Standards Organization [ISO], 2000, for hearing; Kim & Mayer, 1994, and Owsley, Sekuler, & Siemsen, 1983, for vision). There is also evidence of a similar age-related decline in vibrotactile threshold sensitivity (e.g., Gescheider, Bolanowski, Hall, Hoffman, & Verrillo, 1994; Verrillo & Verrillo, 1985).

Despite this now long-standing awareness of age-related declines in threshold sensitivity in each of several sensory modalities, there have been very few laboratory studies of the effects of aging on sensory function in multiple modalities within the same group of participants. Typically, researchers have examined age-related changes in processing in the sensory modality within their area of expertise. Seldom has sensory processing in more than one modality been studied carefully in the laboratory in older adults. An exception to this general statement is the study by Stevens, Cruz, Marks, and Lakatos (1998), in which taste, smell, thermal sensitivity (cooling), vibrotaction (both low- and high-frequency), and hearing (both low- and high-frequency) were all measured in the laboratory for young and elderly participants (N = 37). Sensitivity thresholds were measured for each modality, and, except for one sensory measure (low-frequency hearing), group differences in sensory threshold between the young and elderly individuals were observed. Moreover, there were significant positive correlations between sensory threshold and age in each modality, as well as significant correlations of thresholds across modalities. Stevens et al. also reported a strong positive correlation between cognitive function and sensory thresholds. They suggested that both sensory and cognitive function might be affected by a similar common factor or mechanism that declines with age.

This suggestion by Stevens et al. (1998) is akin to the common-cause hypothesis observed in larger scale field studies of aging (Baltes & Lindenberger, 1997; Lindenberger & Baltes, 1994), a hypothesis that has received considerable attention in the aging literature over the past 20–30 years (for a review, see Hofer, Berg, & Era, 2003), with generally mixed support. For example, it has been argued that the support for this hypothesis is largely an artifact of the research design and attributable to the pooling of data from measures of sensory and cognitive function across extremes of the adult age continuum, which can inflate correlations among these measures (e.g., Hofer et al., 2003; Hofer, Flaherty, & Hoffman, 2006). As will be noted in more detail in the Discussion section, this is certainly a relevant issue for the interpretation of the correlations obtained by Stevens et al. between sensory and cognitive function. To minimize the likelihood of this occurring in the present study, correlational analyses were restricted to the older group alone, a group that was much more homogeneous with regard to age.

One of the notable differences between the laboratory study of Stevens et al. (1998) and most of the studies addressing the common-cause hypothesis is that the latter were typically larger scale field studies making use of less rigorous measures of sensory acuity than those typically used in laboratory studies. Such measures of acuity are often less precise and more subject to response bias than are the forced-choice psychophysical procedures employed in the laboratory (e.g., Green & Swets, 1966). It has been suggested, for example, that older adults employ a more conservative response criterion than do younger adults, at least for measures of threshold sensitivity (e.g., Potash & Jones, 1977; Rees & Botwinick, 1971). Consequently, given that common field measures of acuity are not criterion free, it is possible that a conservative response criterion could be an underlying common cause that affects measures of sensory acuity and cognitive function in older adults.

Whether laboratory-based or field measures, the focus of the research on effects of aging across modalities has been on simple threshold sensitivity or acuity. In the present study, we sought to go beyond simple measures of acuity by assessing temporal processing of auditory, visual, and tactile stimuli. A large-scale study is underway involving several temporal-processing measures obtained from young and older adults. In the present report, we present data collected for one such measure of temporal processing: the detection of a temporal gap in the stimulus. (This represents the first of the temporal-processing measures for which data collection has been completed for a sufficient number of young and older adults from the larger study still in progress.)

Temporal gap detection was selected for study for several reasons. Foremost among these reasons is that, within each modality, evidence has accumulated that supports the existence of age-related declines in gap-detection thresholds. Investigators have reported higher (longer) gap-detection thresholds for older participants when using visual (Amberson, Atkeson, Pollack, & Malatesta, 1979), vibrotactile (van Doren, Gescheider, & Verrillo, 1990), or auditory (He, Horwitz, Dubno, & Mills, 1999; Moore, Peters, & Glasberg, 1992; Schneider & Hamstra, 1999; Schneider, Pichora-Fuller, Kowalchuk, & Lamb, 1994; Snell, 1997; Snell & Frisina, 2000; Snell & Hu, 1999; Strouse, Ashmead, Ohde, & Granthan, 1998) stimuli. There is also visual and auditory evoked-potential research in support of poor gap detection in the elderly (Boettcher, Mills, Swerdloff, & Holley, 1996; Porciatti, Burr, Fiorentini, & Morrone, 1991).

Gap detection has often been associated with the phenomenon of stimulus persistence. For decades, primarily on the basis of a wide range of measures in the visual domain, age-related differences in the phenomenon of stimulus persistence have been hypothesized as an underlying cause of a host of perceptual effects associated with aging (Botwinick, 1978). This theory maintains that the internal sensory trace associated with the presentation of a physical stimulus endures longer in the aged nervous system than it does in young adults. Kausler (1991) provided an excellent summary of the many ways in which this single underlying mechanism of stimulus persistence can be applied to account for several age-related differences in perceptual performance. For example, exaggerated stimulus persistence in the elderly would lead to predictions of poorer performance by the elderly on tasks involving forward or backward masking, as well as detection of brief decrements in stimulus amplitude.

In the present study, we obtained laboratory measures of threshold sensitivity and temporal gap detection from young and older adults in each of three sensory modalities: hearing, vision, and touch. Moreover, except for visual gap detection, multiple measures were obtained on each task in each modality by making measurements at two or more stimulus frequencies. In addition to these sensory measurements, we used the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale (WAIS–III; Wechsler, 1997) to measure the general cognitive function of all of our participants. These data will enable confirmation of age-related declines on each task and in each modality but, more important, will also enable the examination of associations across tasks and modalities among the older adults.

METHOD

Participants

Two groups of adults participated in this study. The first group was composed of 42 young adults (30 female, 12 male) with a mean age of 23 years (range = 18–31 years), and the second group consisted of 137 older adults (78 female, 59 male) with a mean age of 70 years (range = 60–88 years). Mean WAIS–III digit span scores were 20 (range = 13–29) and 17 (range = 8–28) for the young and older adults, respectively.

Participants were recruited for this study via advertisements in the local newspaper, bulletins or flyers for local community centers or organizations, and postings in various locations on the campus of Indiana University. For this study, the only selection criteria were based on age (18–35 years for the young adults and 60–89 years for the older adults), a score ≥25 on the Mini Mental State Examination (Folstein, Folstein, & McHugh, 1975), and several measures of basic sensitivity. Maximum acceptable hearing thresholds and allowable visual acuity were established. Specifically, participants had to have corrected visual acuity of at least 20/40 based on an evaluation with a Snellen chart by a licensed optometrist, hearing thresholds for air-conducted pure tones that did not exceed a maximum permissible value at each of several frequencies in at least one ear, and no evidence of middle-ear pathology in the test ear (air–bone gaps less than 10 dB and normal tympanograms). The maximum acceptable hearing thresholds (measured clinically) were (1) 40 dB HL (American National Standards Institute, 2004) at 250, 500, and 1000 Hz; (2) 50 dB HL at 2000 Hz; (3) 65 dB HL at 4000 Hz; and (4) 80 dB HL at 6000 and 8000 Hz. These limits were not designed to be particularly selective. In the end, 34 older adults who responded to recruitment advertisements were excluded from participation in this study because their hearing loss was too severe, and none were excluded on the basis of visual acuity.

Informed consent was obtained from all participants in this study. Participants were paid for their participation. Young adults were paid $7 or $8/h (increased over the course of the study), whereas older adults were paid $10/h. For the results reported here, the total testing time for each participant was about 15 h.

General Procedure

All participants who met the selection criteria for the study completed the full WAIS–III cognitive assessment. This included 13 standard subtests and 2 optional subtests of incidental learning. Once this test was completed, auditory testing was scheduled, and once it was completed, tactile and visual testing followed.

One of the overall design objectives for this study was to attempt to use similar stimuli and measurement procedures across modalities for a given task. Nonetheless, there are many modality-specific details regarding the stimuli, apparatus, and procedure. As a result, this section on procedure has been organized by modality, rather than by task.

Before proceeding to the modality-specific methodological details, the general features of the psychophysical method common to all modalities are reviewed here. Prior to actual data collection for threshold sensitivity and gap detection, all participants received 20–30 practice trials to become familiar with the task. These trials could be repeated a second time to ensure comprehension of the task, if desired by the participant, but this was seldom requested.

For measures of threshold sensitivity, an adaptive two-interval two-alternative forced choice paradigm was employed. For threshold measurements, participants simply selected the interval that contained the signal with an a priori probability of .5 that the signal would be in either Interval 1 or Interval 2. Signal amplitude was varied adaptively from trial to trial to bracket the 70.7% and 79.3% correct points on the psychometric function using two interleaved tracks (Levitt, 1971). Responses were self-paced, and feedback was presented after each correct or incorrect response.

For the 70.7% track, two consecutive correct responses resulted in a decrease in signal amplitude, and each incorrect response resulted in an increase in signal level (Levitt, 1971). For the 79.3% track, three consecutive correct responses were required in order to produce a decrease in signal amplitude, and each incorrect response was again followed by an increase in signal level. The step size used to adjust signal amplitude from trial to trial varied with the number of reversals in signal amplitude during a given adaptive run. Initial step size was larger than the final step size, with the initial step size employed for the first two of nine reversals in signal amplitude constituting an adaptive run. For the trials completed for the last seven reversals of signal amplitude, a smaller step size was employed. Since the two adaptive tracking procedures used to adjust signal level from trial to trial were interleaved randomly (at least until the first of the two tracks had been completed in a given block of trials), the actual signal amplitude used in a given trial tended not to follow the orderly progressions dictated by the adaptive rules. The first two reversals were discarded, and the reversal points for the remaining seven reversals were averaged for each of the interleaved tracks. The interleaved tracking procedure was repeated three times. This resulted in three estimates of 70.7% correct performance and three estimates of 79.3% correct performance for a given signal frequency. As will be explained below, in most cases, these six performance estimates were averaged in order to provide a single threshold estimate corresponding to approximately 75% correct on the psychometric function. In general, such estimates were typically based on a total of 200–250 trials.

For measures of gap-detection threshold, the same interleaved adaptive tracking procedure as that described for the threshold measurements was used in these measurements, including performance levels tracked (70.7% and 79.3%), total number of reversals (nine), number of initial reversals discarded (two), and use of a smaller step size for the final seven reversals. For gap-detection measurements, however, it was the duration of the temporal gap that varied adaptively from trial to trial, rather than the signal amplitude. In addition, for these measurements, a three-interval two-alternative forced choice paradigm was used. The three intervals were standard, Comparison Interval 1, and Comparison Interval 2, in that order. The stimulus waveforms in a given trial were identical, except that a temporal gap had been inserted into the stimulus presented during Comparison Interval 1 or 2. The specific stimulus waveform used on a given trial, however, was randomly selected from among the 16 available in a stimulus catalog generated for use in each modality. The participant's task on each trial was to select the comparison interval that contained the gap or that differed from the standard (which never contained a gap). The stimulus with the gap was randomly assigned to either the first or second comparison interval with an a priori probability of .5. The gap was established by essentially setting the amplitude values for a portion of the stimulus waveform to zero for a specific duration (gap duration). As such, the overall stimulus duration from onset to offset was the same in each interval. The abrupt insertion of zero amplitude in the waveform resulted in a spread of energy to other stimulus frequencies outside the stimulus passband. This necessitated the use of a background noise that covered a broad spectrum to ensure that the cue available to the participant for gap detection was temporal and not spectral in nature. Further modality-specific methodological details follow.

Tactile Measurements

As stated above, two sets of measurements were completed in this study: measures of absolute sensitivity and temporal gap-detection measures. Absolute thresholds for vibratory stimuli were determined for two different frequencies: a low-frequency vibration and a high-frequency vibration. Temporal gap-detection thresholds were measured with two different band-limited noises: one noise centered in a low-frequency range and one centered in a high-frequency range.

Stimuli

For the absolute threshold measurements, two frequencies were tested: 30 and 250 Hz. The stimuli were sinusoids presented for 500 msec with a linear rise–fall time of 50 msec. For the temporal gap detection task, low-frequency and high-frequency bands of noise were used. The low-frequency noise was centered at 35 Hz with a bandwidth of 30 Hz (20–50 Hz) and steep rejection rates. The high-frequency noise was centered at 250 Hz with a bandwidth of 30 Hz (235–265 Hz) and steep rejection rates. Noise bands were generated by passing white noise through an 18th-order Chebychev digital filter using Adobe Audition Version 2.0. The duration of the noise stimuli was 400 msec, presented with a linear rise–fall time of 50 msec. When a temporal gap was presented, it was temporally centered in the noise stimulus.

Apparatus

The vibratory stimuli were delivered through a B&K mini-shaker Type 4810 vibration generator. The mini-shaker was fitted with a circular contactor 9 mm in diameter. The contactor protruded 0.5 mm through a fixed circular surround 11 mm in diameter. The shaft of the mini-shaker was fitted with a PCB Model 352A24 accelerometer. The signal from the accelerometer was amplified (using a PCB Model 483A21 amplifier) and the voltage recorded, which served as a measure of the amplitude of vibration. The amplitude of vibration (via the recorded voltage) was controlled by a programmable attenuator.

Procedure

Participants were seated with their left arm extended and the index distal finger pad on their left hand placed in contact with the vibratory contactor. Weights were draped over the arm to stabilize it. To eliminate auditory cues, participants wore earphones through which noise was presented. The earphones were worn throughout the testing session.

For the detection task, a vibratory signal was presented in one of two observation intervals. The observation intervals were signaled by text illuminated on a computer screen in front of the participant. Following the presentation of the two observation intervals, the participant indicated orally whether the signal had been presented in Interval 1 or Interval 2, and this response was entered by the experimenter on the computer keyboard. Trial-by-trial correct-response feedback was provided.

At the beginning of a run, the vibratory stimuli were set at a high level. The initial reductions in vibratory amplitude were in step sizes of 14 dB. Following the first reversal (incorrect response) in each track, the intensity was increased by 14 dB. Following the next reversal, the step size was reduced to 2 dB, where it stayed for the remainder of the run.

For the gap-detection measurements, clearly perceptible stimuli were desired. To ensure that the stimuli were clearly perceptible, the voltage generating the low-frequency noise was set 25 dB above threshold voltage for the 30-Hz sinusoid. Similarly, the voltage for the high-frequency noise was set 25 dB above the threshold voltage for the 250-Hz sinusoid. To eliminate possible cues produced by the onset and offset of the temporal gap, a noise stimulus was presented throughout the interval in which the test stimuli were presented. The noise was a pink noise, with a high-frequency cutoff at 1000 Hz and set at a voltage 10 dB below the voltage set for the high-frequency noise stimulus. The resulting percept was a continuous “buzz” felt throughout the observation intervals, with the test stimuli clearly perceptible above this baseline stimulus. In the presence of this background stimulus, there were no noticeable spectral off-frequency cues at the onset and offset of the temporal gap.

Participants were presented with three vibratory signals: a standard stimulus followed by two comparison stimuli, with one of the two of the latter containing a temporal gap. The computer screen provided visual cues informing the participant when the standard and comparison stimuli were being presented. Participants responded orally, and the experimenter entered responses using the computer keyboard.

The tracking procedure for determining the gap-detection thresholds was similar to that used in the detection task and consisted of two interleaved adaptive tracks. A threshold run began with a large temporal gap and large step sizes that gradually shortened with the reversals. Specifically, the runs began with gaps of 120 msec and step sizes of 60 msec. Following the first reversal, the step size was reduced to 30 msec, then to 18 msec with the next reversal, and finally to 6 msec. The step size remained at 6 msec for the remainder of the run (seven additional reversals). No temporal gap greater than 120 msec was permitted. If the participants reached that limit, the temporal gap remained at 120 msec until the participants either produced a sufficient number of correct responses to reduce the size of the gap or completed 130 trials.

Visual Measurements

As with the tactile measurements, both threshold sensitivity and gap detection were measured for visual stimuli. The measure of threshold sensitivity was essentially a measure of flicker sensitivity. Flicker sensitivity was determined by flickering a light around a constant mean luminance. Flicker frequencies of 2, 4, 8, and 32 Hz were used. The depth of modulation around the mean luminance was adaptively varied to achieve a threshold contrast value in a modified two temporal interval task. Gap detection was measured by presenting one standard and two test intervals, one of which had a temporal gap in it. The width of the gap was adaptively varied to find a threshold gap size.

Stimuli and Apparatus

Both tasks used the same apparatus for stimulus generation. A custom-designed light box was used, in which six 60-watt incandescent bulbs back-projected onto a white translucent Plexiglas panel to produce an adapting surround of 112 cd/m2. This panel was 57 × 57 cm, and in the center (behind the white Plexiglas panel) was a red light-emitting diode (LED) display device consisting of 12 LEDs that projected through three additional diffusing screens. The luminance was adjusted so that the mean luminance was 127.5 cd/m2. The display device cast a shadow of 10.78° of visual angle, and inside was the red circle with a diameter of 5.39°. Participants freely viewed the display at 53 cm, with both eyes, in a fully illuminated room (fluorescent lighting).

The stimuli were driven through a custom circuit and programmed via a 12-bit digital/analog (D/A) card (National Instruments PCI-6071e). Stimulus sequences were generated in MATLAB (Math-Works, Natick, MA) and sent to the D/A card via the Real Time Toolbox (Humusoft, Prague, Czech Republic). No auditory cues were perceptible from the operation of the device. The update rate was 1000 Hz.

Procedure

Participants were comfortably seated in front of the display. The experimenter initiated each trial. In the flicker threshold task, only two intervals were used, marked by auditory recordings (“Test 1” and “Test 2”). The experimenter initiated each trial, and the LEDs were modulated around the baseline 127.5-cd/m2 level at one of four frequencies (2, 4, 8, or 32 Hz). This LED modulation was embedded in a Gaussian temporal envelope 500 msec in duration. The effective visible duration was approximately 250 msec. The depth of modulation was varied according to two interleaved tracking programs with an initial step size for the first two reversals of each track of 0.25 and a final step size for the remaining seven reversals of each track set to 125. Contrast was defined as contrast = (luminance – 127.5)/127.5.

Note that this flicker task is not an absolute threshold task, since the background luminance was set to 127.5 cd/m2, and the room lights were left on. It was decided that these testing conditions would be more relevant to situations in which the participants interact with a well-lit world. It was also decided that dark-adapting our participants and running them in complete darkness would be overly burdensome. Thus, the visual task should be viewed as a relative flicker judgment (i.e., determining which interval contained a steady light that appeared to flutter), as opposed to the tactile and auditory domains, in which the task measured absolute detection thresholds for the different frequencies.

A trial in the gap-detection task consisted of recorded auditory voice markers (“Standard,” “Test 1,” “Test 2”) that indicated the onset of each of three observation intervals and coincided with stimulus presentation. The stimuli in all three intervals of a trial were defined by a 50% increase in contrast for 400 msec, with each interval separated by 2,000 msec. White noise was added in order to mask the transients associated with the temporal gap. The added noise prevented the participants from relying on the abrupt transients associated with the onset and offset of the gap. The noise was gated with the presentation of each of the three stimuli in a trial. The gap appeared in either the second or third interval and was centered at 300 msec into the 400-msec stimulus. The same noise stimulus was repeated for each of the three stimuli in the sequence, although the noise was randomized for each trial.

After each trial, the participant verbally indicated whether the first or second test interval contained the gap. This response was entered by the experimenter on the computer keyboard, and the program then provided auditory feedback (“Correct” or “Incorrect”). Two interleaved adaptive tracks were used, and the step size used decreased after the first two reversals for each track. Initial gap values were 40 msec, and initial step size was 12 msec, followed by a step size of 2 msec for the last seven reversals.

Auditory Measurements

Stimuli and Apparatus

Auditory thresholds were measured for three pure-tone frequencies: 500, 1414, and 4000 Hz. Stimuli were 500 msec in duration from onset to offset and had 25-msec linear rise–fall times. Stimuli were generated offline and presented to the listener using custom MATLAB software. Stimuli were presented from the Tucker-Davis Technologies (TDT) digital array processor with 16-bit resolution at a sampling frequency of 48828 Hz. The output of the D/A converter was routed to a TDT programmable attenuator (PA-5), to a TDT headphone buffer (HB-7), and then to an Etymotic Research 3A insert earphone. The insert earphone was calibrated acoustically in an HA-1 2-cm3 coupler (Frank & Richards, 1991). With the headphone buffer set to –15 dB, the maximum outputs for the pure-tone stimuli were 98, 100, and 101 dB SPL at 500, 1414, and 4000 Hz, respectively. Further attenuation was provided via the programmable attenuator under software control during the measurement of auditory thresholds. Output levels were checked electrically just prior to the insertion of the earphones at the beginning of each data-collection session and were verified acoustically in the coupler on a monthly basis throughout the study.

For the auditory gap-detection measurements, two 1000-Hz-wide bands of noise served as the stimuli with one band centered arithmetically at 1000 Hz (500–1500 Hz) and the other centered at 3500 Hz (3000–4000 Hz). Each noise band had a duration from onset to offset of 400 msec with 10-msec linear rise–fall times. A catalog of 16 different noise bands was generated for each frequency region. When a temporal gap was present in a noise band, it was temporally centered at a location 300 msec post-stimulus-onset. Gap durations varied from 2 to 40 msec in steps of 2 msec and were generated by zeroing the waveform at that temporal location. This processing was applied to each of the 16 waveforms cataloged for each frequency region. The zeroing of amplitude at the location of the temporal gap amounts to instantaneous onset and offset of the temporal gap and results in spectral cues outside the noise band that could be used by the listener to detect the presence of a temporal gap. To eliminate such spectral cues, a broadband noise with a spectral notch with cutoff frequencies identical to those of the noise band was presented in the background. The background noise was present throughout a given trial—a duration of 2.4 sec—but turned off between trials. The noise bands used as test stimuli and the complementary spectral notches in the background noise were realized by filtering white noise with 18th-order Chebychev digital filters. The spectrum level of the background noise was adjusted to be 12–15 dB below that of the stimulus noise bands. At the location of the noise bands, FFT analysis indicated that the background noise spectrum level was 50–60 dB below that of the stimulus noise band at each frequency. With 0-dB attenuation in the headphone buffer and programmable attenuator, the noise bands centered at 1000 and 3500 Hz each generated an overall level of 103 dB SPL, as measured in an HA-1 2-cm3 coupler. Corresponding ⅓-octave-band sound levels were 95 dB SPL at 1000 Hz for the noise band centered at 1000 Hz and 100 dB SPL at 3150 Hz for the noise band centered at 3500 Hz. An overall presentation level of 91 dB SPL was used for each noise band and for all listeners in this study. A relatively high presentation level was used, given the likelihood of significant threshold elevations in many of the older adults, especially at the higher frequencies.

Procedure

Threshold measurements were completed prior to gap-detection measurements for all listeners. For threshold measurements, frequencies were tested in the same order for all participants: 500 Hz, then 1414 Hz, and finally, 4000 Hz. The two observation intervals, each 500 msec in duration, were marked by visual indicators (rectangular response boxes labeled “Test 1” and “Test 2”), which flashed in sequence on the computer display, one of which was coincident with the presentation of the 500-msec signal. The listener was prompted to respond by pressing the interval marker on the screen that corresponded to the interval containing the signal. Responses were self-paced, and feedback was presented on the computer display after each response as an orthographic presentation of “Correct” or “Incorrect.”

The starting level for a given block was set to be about 30–40 dB above the estimated threshold for that same frequency, which was based on the participant's previously completed clinical audiogram. The initial step size for the first two reversals was 8 dB, and the final step size used for the subsequent seven reversals was 2 dB. If either the three 70.7% or the three 79.3% estimates exhibited differences between the maximum and minimum estimates across the three blocks that exceeded 6 dB, subsequent blocks of trials were run until this was no longer the case. Approximately 10% of the time, a fourth block of trials was required in order to meet this reliability criterion.

For the gap-detection threshold measurements, all participants completed measurements at 1000 Hz before beginning data collection at 3500 Hz. Each interval of the three-interval paradigm was 400 msec in duration, corresponding to the duration of the noise-band stimuli. The background noise with a spectral notch complementary to the bandwidth of each stimulus began slightly before the standard interval and ended slightly after the Test 2 interval for a total duration of 2.4 sec. Touchscreens were used to collect responses from the participant, and the size of the temporal gap was adjusted adaptively from trial to trial. The initial gap duration was 20 msec, the initial gap step size was 6 msec, and the final gap step size was 2 msec. All auditory testing was completed in a sound- attenuating booth meeting the ANSI S3.1 standards for ears-covered threshold measurements (American National Standards Institute, 2001). Two adjacent participant stations were housed within the booth. Right ears were tested for all of the participants.

RESULTS

Across all modalities and tasks, there were 14 dependent measures obtained from each of the participants in this study. Moreover, there were six performance estimates obtained for each of the 14 measures: three repetitions of 70.7% correct performance estimates and three repetitions of 79.3% correct performance estimates. To assess the validity and stability of these performance estimates, 14 repeated measures general linear model (GLM) analyses, one for each dependent measure, were performed for the pooled data (N = 179) using SPSS (Version 15) with repeated measures variables of performance level (70.7% vs. 79.3%) and block number (1–3). If the interleaved adaptive tracks were yielding valid results, one would expect the threshold estimates corresponding to 79.3% correct performance to be higher than those corresponding to 70.7% corrrect performance. The 79.3% correct performance estimates were, in fact, significantly higher than those corresponding to 70.7% correct performance (p < .05) for each of the 14 dependent measures in this study.

The effects of trial block or adaptive threshold run were also examined. Stable performance estimates would be reflected by the lack of significant differences in performance across the three adaptive runs or trial blocks for each of the 14 dependent measures. For 7 of the 14 dependent measures, however, significant (p < .05) effects of trial block were observed. Since no significant (p > .05) interactions were observed between the effects of performance level and trial block for any of the 14 dependent measures, post hoc paired-sample t tests were performed examining the effects of trial block on performance for the 7 dependent measures that yielded a significant effect of trial block in the GLM analyses. In 6 of the 7 cases for which trial block was found to be significant, it was the case that the performance estimates obtained for the first block were significantly higher than those obtained for the second or third trial blocks or for both the second and third trial blocks. Basically, this pattern is consistent with a learning or practice effect, such that performance estimates after the first block were better (lower or shorter) than those obtained during the first block. This learning or practice effect was observed in the pooled data for the following dependent measures: tactile threshold at 250 Hz; tactile gap detection at 35 Hz; visual threshold at 2, 4, and 8 Hz; and visual gap detection. For the remaining dependent measure that yielded a significant effect of trial block (auditory threshold at 1414 Hz), the performance estimate from the third trial block was significantly higher than that obtained from the first trial block, consistent with a fatigue effect. For these 7 dependent measures with significant effects of trial block, the performance estimates at 70.7% and 79.3% from the discrepant block of trials were discarded, and the remaining four performance estimates (70.7% and 79.3% from the remaining two trial blocks) were averaged to yield a single threshold estimate corresponding to approximately 75% correct on the psychometric function. For the 7 remaining dependent measures for which no significant effects of trial block were observed, the six performance estimates were averaged to yield a similar single threshold estimate. All subsequent analyses reported for this study are based on these averaged threshold estimates corresponding to about 75% correct on the psychometric function.

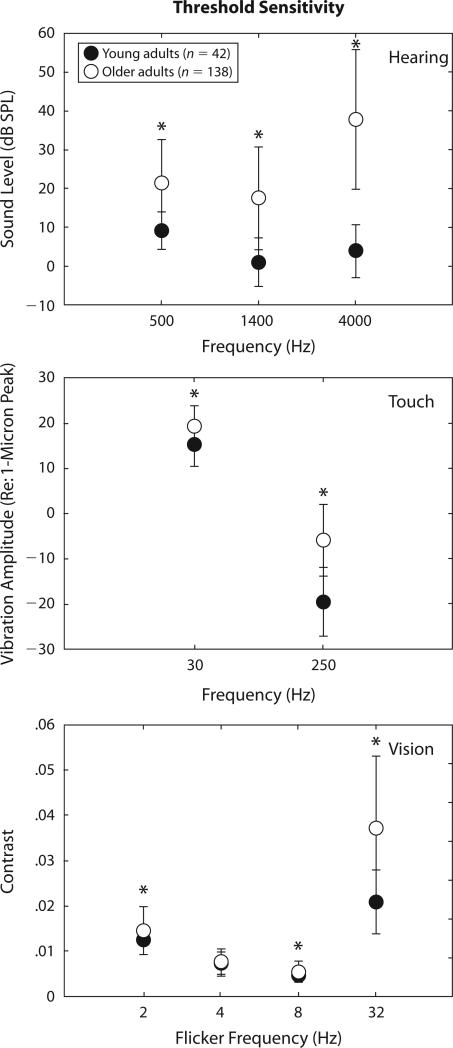

Figure 1 depicts the group data for the measures of threshold sensitivity. The filled circles show the means for the young adults, and the unfilled circles depict the means for the older adults. Error bars represent one standard deviation. The top panel provides the group data for hearing, the middle panel for touch, and the bottom panel for vision. Results are plotted separately for each frequency in each modality. Three separate mixed-model GLM analyses were completed, one for each modality, with a repeated measures factor of stimulus frequency and a between-subjects factor of age group. In all three GLM analyses, significant (p < .05) main effects of age group and stimulus frequency were observed, and the age group × stimulus frequency interaction was significant. Since our primary interest was in age group differences, rather than the effects of stimulus frequency within a modality, post hoc independent-sample t tests were performed to examine the effects of age group on performance for each of the nine threshold estimates in Figure 1. Asterisks in Figure 1 mark those comparisons that were found to be significant (p < .05, not adjusted for multiple comparisons). For all but visual threshold at 4 Hz, the older adults showed significantly worse threshold sensitivity than did the young adults. The size of this age effect, moreover, appears to be greater at higher frequencies in all three modalities.

Figure 1.

Mean threshold values for the 42 young adults (filled circles) and 137 older adults (unfilled circles) for hearing (top), touch (middle), and vision (bottom). Error bars represent one standard deviation. *differences between the two groups significant at p < .05.

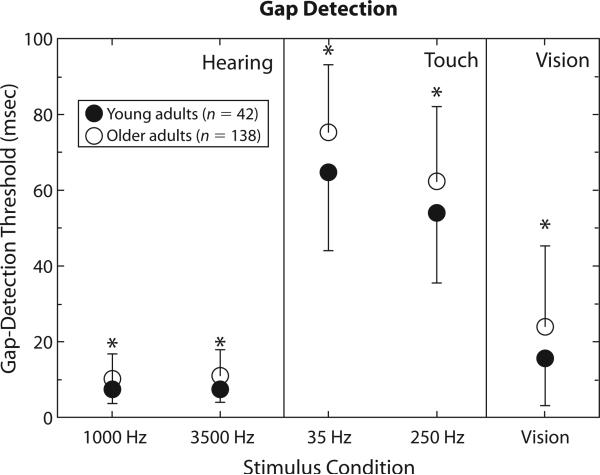

Figure 2 shows the group data for the gap-detection measures. Circles again depict mean values for gap-detection thresholds, and the error bars represent one standard deviation (shown only in one direction, and in opposite directions for each group, for clarity). The group data for hearing are shown in the left panel, touch in the middle panel, and vision in the right panel. Mixed-model GLM analyses were again performed for the gap-detection results for hearing and touch, with a repeated measures factor of stimulus frequency and a between-subjects factor of age group. Since there was only one gap-detection measure for vision, a single independent-sample t test was performed for this modality instead. For hearing, the main effect of age group was significant (p < .05), with older adults having longer gap-detection thresholds than did younger adults, but the main effect of stimulus frequency and the age group × stimulus frequency interaction were not significant (p > .05). For touch, the main effects of age group and stimulus frequency were both significant, but the interaction of these two factors was not. Gap-detection thresholds were longer for older adults and longer at the lower stimulus frequency. For vision, older adults had a significantly longer gap-detection threshold than did younger adults. The significant group differences are marked in Figure 2 by asterisks, and it is apparent that older adults had longer gap-detection thresholds for all frequencies and modalities.

Figure 2.

Mean gap-detection thresholds for the 42 young adults (filled circles) and the 137 older adults (unfilled circles) for hearing (left), touch (middle), and vision (right). Error bars show one standard deviation (either positive for older adults or negative for young adults, for clarity). *differences between groups significant at p < .05.

In addition to the analysis of the group data, individual differences in performance were also of interest. In particular, correlations across modalities, frequencies, and tasks were of interest. The data from the young adults were obtained primarily as baseline data for group comparisons with the data from the older adults. This group is smaller in number than the older adults and also considerably younger, with a 47-year difference between the average ages of the two groups. Since significant effects of age group have been observed for 13 of the 14 dependent measures, pooling the data across age group for the analysis of individual differences via correlations would be inappropriate (e.g., Hofer et al., 2003; Hofer et al., 2006). Instead, we chose to examine the correlations across the 14 dependent measures among the 137 older adults only.

Table 1 provides the Pearson r product–moment correlations (above the diagonal) among the 14 dependent measures obtained from the 137 older adults in this study. The table cells shaded gray along the diagonal represent those cells with correlations across dependent measures within a single modality. Correlation coefficients in bold represent those that are significant at the level of p < .01. Consider the intramodal correlations for hearing in the upper left portion of the correlation matrix. Of the 10 correlations available for these measures, 8 are significant. However, it is also apparent that the measures within the same task, threshold or gap detection, are more strongly correlated with one another than with those across tasks. For example, the correlations of hearing threshold at 1414 Hz with hearing thresholds at 500 and 4000 Hz are r = .56 and .55, respectively. Likewise, the correlation between the two auditory measures of gap detection, one at 1000 Hz and one at 3500 Hz, is r = .69. Although there are many significant correlations within the auditory modality across the threshold and gap-detection tasks, these are generally about half the magnitude of the correlations across frequency within the same task and modality (r = .22–.36).

Table 1.

Pearson r Correlation Coefficients Among the 14 Dependent Measures of Threshold Sensitivity and Gap Detection (Above the Diagonal) and Partial Correlations Controlling for Age (Below the Diagonal)

| AT500 | AT1414 | AT4000 | AG1000 | AG3500 | TT30 | TT250 | TG35 | TG250 | VT2 | VT4 | VT8 | VT32 | VG | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AT500 | .56 | .21 | .22 | .26 | –.03 | .18 | –.03 | .06 | .15 | .16 | .08 | .02 | .06 | |

| AT1414 | .53 | .55 | .25 | .36 | .07 | .08 | –.02 | .13 | .01 | .09 | .12 | .09 | .22 | |

| AT4000 | .16 | .51 | .13 | .27 | .25 | .12 | .05 | .10 | –.07 | .05 | .14 | .08 | .21 | |

| AG1000 | .14 | .22 | .09 | .69 | .06 | .14 | .17 | .18 | .16 | .19 | .10 | .05 | .37 | |

| AG3500 | .17 | .34 | .21 | .71 | .14 | .09 | .19 | .25 | .16 | .22 | .18 | .00 | .40 | |

| TT30 | –.09 | .01 | .20 | .01 | .09 | .39 | –.04 | –.03 | –.10 | .00 | –.06 | –.07 | .12 | |

| TT250 | .07 | –.01 | .03 | .03 | –.03 | .36 | .04 | .04 | –.08 | –.02 | .01 | .12 | .04 | |

| TG35 | –.05 | –.07 | –.01 | .17 | .22 | –.10 | –.01 | .49 | .13 | .28 | .30 | .17 | .27 | |

| TG250 | .03 | .08 | .05 | .18 | .20 | –.07 | .00 | .48 | .28 | .21 | .32 | .18 | .25 | |

| VT2 | .13 | –.01 | –.11 | .17 | .16 | –.13 | –.13 | .12 | .27 | .65 | .47 | .25 | .28 | |

| VT4 | .16 | .07 | .01 | .22 | .23 | –.04 | –.05 | .28 | .18 | .65 | .70 | .45 | .32 | |

| VT8 | .02 | .06 | .07 | .06 | .14 | –.12 | –.08 | .28 | .30 | .47 | .71 | .56 | .32 | |

| VT32 | –.06 | –.05 | –.05 | .01 | –.07 | –.18 | .01 | .12 | .11 | .25 | .46 | .55 | .22 | |

| VG | .04 | .18 | .11 | .41 | .48 | .06 | –.03 | .24 | .23 | .31 | .34 | .26 | .11 |

Note—Gray cells show regions in the matrix involving intramodality comparisons. Coefficients in bold are significant at p < .01. Variable code: first letter, modality (A, auditory; T, tactile; V, visual); second letter, task (T, threshold; G, gap detection); numbers, stimulus frequency in hertz.

A somewhat similar pattern is observed among the correlations for the four dependent measures for touch, shown within the gray cells in the middle of the correlation matrix. Here, only two correlations are significant, and each represents a correlation across frequency within the same task. For example, for the two tactile thresholds, one at 30 Hz and the other at 250 Hz, the correlation coefficient is r = .39, and for the two tactile gap-detection thresholds, the correlation coefficients is r = .49. None of the correlations across the two tactile tasks are significant (r = –.04 to .04).

Finally, examination of the intramodality correlations across frequencies and tasks for vision—the gray cells in the lower right of the correlation matrix—reveals that all 10 of the correlations are statistically significant. Closer inspection, however, again reveals that the correlations within task and across frequency are stronger than those across tasks within the same modality. For example, for the 6 correlations between visual thresholds obtained at various frequencies (2–32 Hz), 5 of the 6 are in the range of r = .45–.70. On the other hand, all 4 of the correlations between visual thresholds at each of these frequencies and visual gap-detection thresholds, although statistically significant, are weaker (r < .32).

The cells in Table 1 that are populated with correlation coefficients that are not shaded in gray represent the set of potential cross-modality correlations. In contrast to the intramodal correlations in the gray cells, 20 of 26 of which were statistically significant, only 10 of 65 correlations were found to be statistically significant (p < .01). These 10 correlation coefficients are also in bold. In general, these cross-modality correlations are weaker than the within-task, within-modality correlations, and the range is r = .25–.40. Of the 8 possible correlations across modalities for gap detection, 5 are statistically significant, with the largest correlations between auditory and visual gap detection (r = .37 and .40). Only 1 of 26 correlations between measures of threshold sensitivity was significant across modalities. Finally, the remaining 4 significant cross-modality correlations ranged from r = .28 to .32 and were between visual thresholds at 2, 4, or 8 Hz and tactile gap-detection thresholds. These were the only significant cross-modality and cross-task correlations in Table 1.

The intramodal within-task correlations were consistently among the larger correlations observed, generally ranging from r = .4 to .7, with only a few exceptions. Thus, an older adult with greater hearing loss at 1414 Hz tended to also have more hearing loss at the other two auditory frequencies (500 and 4000 Hz). Likewise, an older adult with longer gap-detection thresholds for the auditory stimulus at 1000 Hz tended to also have longer gap-detection thresholds for the auditory stimulus at 3500 Hz. Similar statements can be made about the tactile sensitivity thresholds and gap-detection thresholds and the visual sensitivity thresholds (multiple measures of visual gap detection were not obtained in this study). This speaks well for the internal consistency or reliability of the dependent measures obtained in this study. It also suggests that there is considerable redundancy among the 14 dependent measures obtained from these 137 older adults.

Even though this group of 137 older adults was relatively homogeneous with regard to age, a 28-year age difference did exist between the youngest and oldest members of this group. To examine whether this age variation could be underlying the observed correlations across tasks or modalities (e.g., Hofer et al., 2003; Hofer et al., 2006), partial correlations controlling for age were also calculated. These correlations appear in Table 1 below the diagonal. The patterns of correlations above and below the diagonal in Table 1 are very similar. Specifically, in both cases, the within-task, within-modality correlations are stronger and more frequently significant, and the cross-modality, cross-task correlations are weaker, with fewer reaching statistical significance.

To reduce the redundancy among the 14 dependent measures prior to further examination of the associations between these dependent measures and other variables, such as age and WAIS–III score, the correlation matrix in Table 1 was subjected to a principal components factor analysis (Gorsuch, 1983). The principal components analysis resulted in five orthogonal factors accounting for a total of 68.5% of the variance. Communalities for the 14 dependent measures were good, generally between .6 and .8, except for visual gap-detection threshold (.47). The component weights for each of the five orthogonal principal components and each of the 14 dependent measures following Varimax rotation are shown in Table 2. On the basis of this pattern of component weights, the five factors were interpreted as visual threshold, auditory and visual gap detection, auditory threshold, tactile gap detection, and tactile threshold. This is entirely consistent with the observations drawn from the correlation matrix in Table 1, which suggested that there were moderate to strong correlations within a task and modality (across frequency) but few noteworthy correlations across modalities or tasks, with the possible exception of auditory and visual gap detection. Factor scores resulting from this five-factor orthogonal solution were generated and saved for the 137 older adults.

Table 2.

Component Weights for Five-Factor Orthogonal Principal-Components Analysis (PC1–PC5) of the 14 Dependent Measures of Threshold Sensitivity and Gap Detection From the 137 Older Adults

| Variable | PC1 (18.8%) | PC2 (14.2%) | PC3 (13.6%) | PC4 (11.4%) | PC5 (10.5%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AT500 | .137 | .243 | .682 | –.232 | –.088 |

| AT1414 | .032 | .171 | .892 | .033 | .005 |

| AT4000 | –.020 | –.018 | .724 | .225 | .283 |

| AG1000 | .044 | .869 | .089 | .064 | .067 |

| AG3500 | .044 | .836 | .238 | .159 | .075 |

| TT30 | –.065 | .099 | .018 | –.034 | .833 |

| TT250 | .037 | .064 | .087 | –.030 | .771 |

| TG35 | .153 | .124 | –.079 | .816 | –.011 |

| TG250 | .174 | .157 | .095 | .758 | –.077 |

| VT2 | .731 | .280 | –.079 | –.034 | –.194 |

| VT4 | .869 | .200 | .026 | .070 | –.026 |

| VT8 | .823 | .015 | .110 | .272 | .010 |

| VT32 | .698 | –.177 | .094 | .180 | .134 |

| VG | .303 | .488 | .092 | .329 | .143 |

Note—Percentage of total variance explained by each principal component in the rotated solution is shown in parentheses. Component weights >0.4 are shown in bold and gray shaded cells. Variable code: first letter, modality (A, auditory; T, tactile; V, visual); second letter, task (T, threshold; G, gap detection); numbers, stimulus frequency in hertz.

DISCUSSION

The group data from this study confirm prior observations regarding the effect of aging on threshold sensitivity and gap detection. Age-related declines in threshold sensitivity, for example, have been observed numerous times in hearing (e.g., Glorig & Roberts, 1965; ISO, 2000), touch (e.g., Gescheider et al., 1994; Verrillo & Verrillo, 1985), and vision (e.g., Kim & Mayer, 1994; Owsley et al., 1983). The increase in the magnitude of the difference in threshold sensitivity between age groups with increasing frequency for each modality is also consistent with this literature. Thus, using criterion-free forced choice psychophysical procedures in this study to measure threshold sensitivity still yielded elevated thresholds in older adults, and the magnitude and frequency dependence of this effect were similar to those observed previously in field studies.

Although there have been fewer studies of the effects of age on gap-detection performance than there have been for threshold sensitivity, especially in touch and vision, the group differences observed in this study are also consistent with the earlier literature. For example, in hearing, when the stimulus bandwidth is fixed, as it was in this study, gap-detection thresholds in young adults do not vary with frequency (e.g., Eddins, Hall, & Grose, 1992). Using a fixed 1000-Hz stimulus bandwidth in this study, no effect of stimulus frequency was observed in either age group, consistent with the findings of Eddins et al. in young adults. In addition, the mean gap-detection thresholds observed here were also consistent with those reported previously in young adults for a 1000-Hz stimulus bandwidth (Eddins et al., 1992). In general, for studies employing stimuli and psychophysical methods similar to those used in this study, auditory gap-detection thresholds in older adults have been found to be slightly, but significantly, elevated relative to those of young adults (e.g., He et al., 1999; Moore et al., 1992; Schneider & Hamstra, 1999; Schneider et al., 1994; Snell, 1997; Snell & Frisina, 2000; Snell & Hu, 1999; Strouse et al., 1998), as was observed here. Age effects similar to those observed in this study have also been reported in gap-detection studies using visual stimuli (e.g., Amberson et al., 1979) and tactile stimuli (van Doren et al., 1990).

In general, the group data from this study confirm prior findings for young and older adults for measures of threshold sensitivity and gap detection. They do so, however, with the use of rigorous psychophysical methods and for sample sizes typically an order of magnitude larger than those used in most prior studies of a similar nature for both age groups, especially for measures of gap-detection thresholds.

The primary focus of this study, however, lies in the associations among the various measures and across modalities within the older adults. The correlation matrix presented in Table 1 generally supports moderate to strong associations (r = .4–.7) across frequency and within a task and modality but very few cross-task and cross-modality associations among the 137 older adults in this study. The primary exceptions to this were weak to moderate correlations across modalities for several of the gap-detection measures (r = .25–.40), especially between hearing and vision, and significant but weak correlations (r = .28–.32) between visual thresholds at several frequencies and tactile gap-detection thresholds. In the latter case, the correlations between visual thresholds and tactile gap-detection thresholds, a temporal measure, may be facilitated by the choice of temporal modulation frequency as the frequency parameter for the visual threshold measures, rather than spatial frequency. This is supported to some extent by the significant correlations (r = .22–.32) between visual sensitivity thresholds and visual gap-detection measures.

In general, the results of the principal-components factor analysis were consistent with the trends visible in the correlation matrix. That is, very little support was provided for associations across tasks or modalities, at least for the older adults.

As noted in the Method section, full WAIS–III assessments were obtained from all participants in this study. This included a total of 15 subtests with raw scores. Raw scores, rather than age-normed scores, were analyzed so as not to discard any age-related changes in cognitive function that might be associated with performance. The raw scores were subjected to a similar principal-components analysis to reduce the redundancy among the WAIS–III measures prior to examining correlations of these cognitive measures with the threshold and gap-detection factor scores. Here, however, oblique (correlated) rotation of the components was performed using the Promax (κ = 4) criterion, because it was believed likely that correlations could exist across the various cognitive domains that might emerge from this analysis. A three-factor solution accounting for 59.7% of the variance emerged. The WAIS–III Digit–Symbol Coding and Symbol Search subtests had greatest component weights on one factor, and this was interpreted as a processing-speed factor as a result. Another factor identified in the principal-components analysis was interpreted as an incidental learning factor, since only the Pairing and Free Recall tasks from the Digit–Symbol Coding measure loaded heavily on this factor. Finally, all other WAIS–III subtests loaded most heavily on a third factor, labeled general cognitive function. The two factors interpreted as general-cognitive and processing-speed factors were significantly correlated (r = .51, p < .01). Factor scores from this three-factor solution were generated for each of the 137 older adults and saved for subsequent correlational analysis.

Recall that the common-cause hypothesis posits an association between sensory and cognitive function. To examine this possibility, Pearson r product–moment correlations were computed between each of the three WAIS–III factor scores, age, and each of the five factor scores that emerged from the analysis of the threshold and gap-detection measures for the 137 older adults. Table 3 provides the resulting correlations. The three top rows illustrate the correlations among the WAIS–III factor scores and age. As noted, the WAIS general and WAIS processing speed factors were moderately and significantly correlated with one another. In addition, it is also apparent that age was significantly (p < .01) and negatively correlated with all three WAIS–III cognitive factor scores, with correlations ranging from r = –.27 to –.42. Thus, age was negatively associated with cognitive function within the 60- to 88-year age range for the participants in this study, although only 8%–13% of the variance in each of the WAIS–III factor scores was accounted for by age.

Table 3.

Pearson r Correlations Among WAIS–III Principal Components, Age, and Factor Scores Derived From the 14 Dependent Measures of Threshold and Gap Detection (PC1 to PC5 in Table 2)

| WAIS Factor |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | General Cognitive Function | Processing Speed | Incidental Learning | Age |

| WAIS Factor | ||||

| Processing speed | .51 | |||

| Incidental learning | .15 | .15 | ||

| Age | –.27 | –.42 | –.29 | |

| Visual threshold sensitivity | –.15 | –.28 | .04 | .16 |

| Audio and visual gap detection | –.34 | –.18 | –.06 | .09 |

| Audio threshold sensitivity | –.07 | –.17 | –.21 | .30 |

| Tactile gap detection | –.03 | –.18 | –.08 | .10 |

| Tactile threshold sensitivity | –.06 | –.20 | –.15 | .39 |

Note—Significant (p < .01) correlations are shown in bold and gray cells. WAIS, Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale.

The remaining 20 correlation coefficients in the lower five rows of Table 3 provide insight into the association of cognitive function or age with performance on the threshold and gap-detection measures in this study. Of these 20 correlations, only 4 are statistically significant (p < .01). Two of the 4 significant correlations are between age and threshold sensitivity, 1 with auditory threshold and 1 with tactile threshold. Both are positive and of similar magnitude (r = .30 and .39), indicating a slight trend toward increasing auditory and tactile sensitivity thresholds with increasing age. The other two significant correlations in the lower portion of Table 3 exhibit correlations of similar magnitude, although negative rather than positive (r = –.34 and –.28), between a measure of cognitive function and one of the dependent-measure factor scores. In one case, auditory and visual gap-detection performance is negatively correlated with the WAIS–III factor score representing general cognitive function. Thus, the higher the older participant's general cognitive performance was, the lower his or her gap-detection threshold in hearing and vision was. In the other case, the higher the participant's processing-speed score on the WAIS–III was, the better (lower) the participant's visual threshold sensitivity was. In all cases, however, these correlations reveal only about 10% shared variance between these measures. Given the significant correlations between age and each of the WAIS–III factor scores, as noted previously, partial correlations controlling for age were also calculated. The magnitude, direction, and statistical significance of the correlations shown in Table 3 remained the same once age was partialed out.

In summary, few correlations were observed in this study across modalities among the threshold and gap-detection measures. The primary exception was the association between auditory and visual gap-detection performance. Otherwise, tasks and modalities appear to be largely independent from one another among older adults in their 60s, 70s, and 80s. Moreover, few associations were observed between measures of cognitive function from the WAIS–III and measures of either threshold sensitivity or gap detection.

As was noted in the introduction, the study that is most comparable to this one, in terms of psychophysical approach, is Stevens et al. (1998). These investigators made use of adaptive two-alternative forced choice psychophysical methods to measure sensitivity thresholds in young (n = 15; 18–27 years old) and older (n = 22; 65–89 years old) adults. They reported correlations between sensitivity thresholds for hearing and touch that were generally significant, positive, and moderate, with three of the four correlations between r = .41 and r = .61. Furthermore, because they saw many significant correlations across modalities (a total of seven threshold measurements were performed, only four of which were in hearing or touch) and with age, they pooled the sensitivity measures into a single z score representing sensitivity across all seven measures and found this to be significantly correlated with a memory score from the Wechsler Logical Memory Test (Wechsler, 1987). The correlation in the latter case was r = –.80 (p < .0001). At first glance, the correlations reported by Stevens et al. appear to be at odds with the present findings. However, the correlations reported by Stevens et al. were computed across both age groups (N = 37), rather than within the older adults alone, as they were computed in this study. Given the extreme age differences in the present study, it was not considered to be appropriate to calculate correlations across the entire group of young and older adults (Hofer et al., 2003; Hofer et al., 2006). Given that significant group differences were observed in this study on 13 of the 14 dependent measures, with the young adults consistently performing better than the older adults did, there is little doubt that the correlations for a pooled data set would be larger than those reported in Table 1 for the older adults alone. Stevens et al. (1998, Figure 6) provided individual data for all 37 participants in their study for the association between memory score and the z score representing average threshold sensitivity across all seven modalities examined. As noted, the correlation for the pooled data set was r = –.8 (p < .0001). When the Pearson r correlation coefficient is calculated only for the 22 older adults in Stevens et al., however, the association between cognitive function and threshold sensitivity is reduced and is no longer statistically significant (r = –.29, p > .10). This is in line with the results of the present study. Unfortunately, additional individual data for the correlations of thresholds across modalities are not available, but, judging from the scatterplots of threshold versus age in Stevens et al., it is likely that such correlations would be reduced considerably if computed only within the older group of participants.

SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONS

Consistent with previous findings, sensitivity to the detection of auditory, visual, and tactile stimuli, as well as measures of temporal acuity, showed significant declines with age. Measures of cognitive performance also showed declines with age. The results did not, however, support the view that, among older participants, declines in sensitivity in one modality or in one task were predictive of declines in other modalities or tasks. Moreover, we did not find that performance on cognitive tasks was predictive of performance on the sensory tasks or vice versa.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported, in part, by NIA Grant R01 AG022334. The authors thank Dana Kinney, Roger Rhodes, Shamim Razawi, and Christopher Clark for their assistance with this project. The support of several students, undergraduate and graduate, working in the laboratories involved in this study is also acknowledged. We also thank the participants for giving so generously of their time for this study and subsequent phases of the larger project.

REFERENCES

- Amberson JI, Atkeson BM, Pollack RH, Malatesta VJ. Age difference in dark-interval threshold across the life-span. Experimental Aging Research. 1979;5:423–433. doi: 10.1080/03610737908257217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American National Standards Institute . Maximum permissible ambient noise levels for audiometric test rooms (ANSI S3.1-1999 [R2003]) Author; Melville, NY: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- American National Standards Institute . Specification for audiometers (ANSI S3.6-2004). Author; Melville, NY: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Baltes PB, Lindenberger U. Emergence of a powerful connection between sensory and cognitive functions across the adult life span: A new window to the study of cognitive aging? Psychology & Aging. 1997;12:12–21. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.12.1.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boettcher FA, Mills JH, Swerdloff JL, Holley BL. Auditory evoked potentials in aged gerbils, responses elicited by noises separated by a silent gap. Hearing Research. 1996;102:167–178. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(96)90016-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Botwinick J. Aging and behavior. 2nd ed. Springer; New York: 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell VA, Crews JE, Moriarty DG, Zack MM, Blackman DK. Surveillance for sensory impairment, activity limitation, and health-related quality of life among older adults—United States, 1993–1997. CDC Morbidity & Mortality Weekly Report. 1999;48(5508):131–156. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eddins DA, Hall JW, III, Grose JH. The detection of temporal gaps as a function of frequency region and absolute noise bandwidth. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 1992;91:1069–1078. doi: 10.1121/1.402633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state”: A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 1975;12:189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank T, Richards WD. Hearing aid coupler output level variability and coupler correction levels for insert earphones. Ear & Hearing. 1991;12:221–227. doi: 10.1097/00003446-199106000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gescheider GA, Bolanowski SJ, Hall KL, Hoffman KE, Verrillo RT. The effects of aging on information-processing channels in the sense of touch: I. Absolute sensitivity. Somatosensory & Motor Research. 1994;11:345–357. doi: 10.3109/08990229409028878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glorig A, Roberts J. Vital & Health Statistics. Department of Health, Education, & Welfare; Washington, DC: 1965. Hearing levels of adults by age and sex, United States, 1960–1962. (Series 11, No. 11). [Google Scholar]

- Gorsuch RL. Factor analysis. 2nd ed. Erlbaum; Hillsdale, NJ: 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Green DM, Swets JA. Signal detection theory and psychophysics. Wiley; New York: 1966. [Google Scholar]

- He NJ, Horwitz AR, Dubno JR, Mills JH. Psychometric functions for gap detection in noise measured from young and aged subjects. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 1999;106:966–978. doi: 10.1121/1.427109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofer SM, Berg S, Era P. Evaluating the interdependence of aging-related changes in visual and auditory acuity, balance, and cognitive functioning. Psychology & Aging. 2003;18:285–305. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.18.2.285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofer SM, Flaherty BP, Hoffman L. Cross-sectional analysis of time-dependent data: Problems of mean-induced association in age-heterogeneous samples and an alternative method based on sequential narrow age-cohorts. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 2006;41:165–187. doi: 10.1207/s15327906mbr4102_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- International Standards Organization . Acoustics: Statistical distribution of hearing thresholds as a function of age (ISO-7029) Author; Basel, Switzerland: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Kausler DH. Experimental psychology, cognition, and human aging. 2nd ed. Springer; New York: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Kim CBY, Mayer MJ. Foveal flicker sensitivity in healthy aging eyes: II. Cross-sectional aging trends from 18 through 77 years of age. Journal of the Optical Society of America. 1994;11:1958–1969. doi: 10.1364/josaa.11.001958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein R, Cruickshanks KJ, Klein BEK, Nondahl DM, Wiley T. Is age-related maculopathy related to hearing loss? Archives of Ophthalmology. 1998;116:360–365. doi: 10.1001/archopht.116.3.360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levitt H. Transformed up–down method in psychoacoustics. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 1971;49:467–477. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindenberger U, Baltes PB. Sensory functioning and intelligence in old age: A strong connection. Psychology & Aging. 1994;9:339–355. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.9.3.339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore BCJ, Peters RW, Glasberg BR. Detection of temporal gaps in sinusoids by elderly subjects with and without hearing loss. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 1992;92:1923–1932. doi: 10.1121/1.405240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owsley C, Sekuler R, Siemsen D. Contrast sensitivity throughout adulthood. Vision Research. 1983;23:689–699. doi: 10.1016/0042-6989(83)90210-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porciatti V, Burr DC, Fiorentini A, Morrone C. Spatio-temporal properties of the pattern ERG and VEP: Effect of ageing. In: Bagnoli P, Hodos W, editors. The changing visual system. Plenum; New York: 1991. pp. 209–217. [Google Scholar]

- Potash M, Jones B. Aging and decision criteria for the detection of tones in noise. Journal of Gerontology. 1977;32:436–440. doi: 10.1093/geronj/32.4.436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rees JN, Botwinick J. Detection and decision factors in auditory behavior of the elderly. Journal of Gerontology. 1971;26:133–136. doi: 10.1093/geronj/26.2.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider BA, Hamstra SJ. Gap detection thresholds as a function of tonal duration for younger and older adults. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 1999;106:371–380. doi: 10.1121/1.427062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider BA, Pichora-Fuller MK, Kowalchuk D, Lamb M. Gap detection and the precedence effect in young and old adults. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 1994;95:980–991. doi: 10.1121/1.408403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snell KB. Age-related changes in temporal gap detection. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 1997;101:2214–2220. doi: 10.1121/1.418205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snell KB, Frisina DR. Relationships among age-related differences in gap detection and word recognition. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 2000;107:1615–1626. doi: 10.1121/1.428446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snell KB, Hu HL. The effect of temporal placement on gap detectability. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 1999;106:3571–3577. doi: 10.1121/1.428210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens JC, Cruz LA, Marks LE, Lakatos S. A multimodal assessment of sensory thresholds in aging. Journals of Gerontology. 1998;53B:P263–P272. doi: 10.1093/geronb/53b.4.p263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strouse A, Ashmead DH, Ohde RN, Granthan DW. Temporal processing in the aging auditory system. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 1998;104:2385–2399. doi: 10.1121/1.423748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Doren CL, Gescheider GA, Verrillo RT. Vibrotactile temporal gap detection as a function of age. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 1990;87:2201–2206. doi: 10.1121/1.399187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verrillo RT, Verrillo V. Sensory and perceptual performance. In: Charness N, editor. Aging and human performance. Wiley; New York: 1985. pp. 1–46. [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler D. Wechsler Memory Scale–Revised. Psychological Corporation; New York: 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler D. Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale (WAIS–III, 3rd ed.). Psychological Corporation; San Antonio: 1997. [Google Scholar]