Abstract

Over the past decade, motivational interviewing has been used by health professionals to promote health behavior changes and help individuals increase their motivation or “readiness” to change. This paper describes a preliminary study used to evaluate the feasibility of motivational interviewing as a component in a school-based obesity prevention program, New Moves. New Moves is a program for inactive adolescent high school girls who are overweight or at risk for becoming overweight due to low levels of physical activity. Throughout the 18-week pilot study, 41 girls, aged 16–18 participated in an all-girls physical education class that focused on increasing physical activity, healthy eating and social support. Individual sessions, using motivational interviewing techniques, were also conducted with 20 of the girls to develop goals and actions related to eating and physical activity. Among the participants, 81% completed all seven of the individual sessions and girls set a goal 100% of the time. Motivational interviewing offers a promising approach as a component for school-based obesity prevention programs and was demonstrated to be feasible to implement in school settings and acceptable to the adolescents.

Keywords: behavior change, motivational interviewing, obesity prevention, adolescent girls

INTRODUCTION

The rising prevalence of obesity and its health risks make obesity one of the most pressing health problems facing youth in the United States (1, 2). Adolescent girls who are overweight face considerable social pressures to conform to a thin societal ideal. Thus, there is a need for obesity prevention interventions that address the unique social and behavioral concerns of adolescent girls.

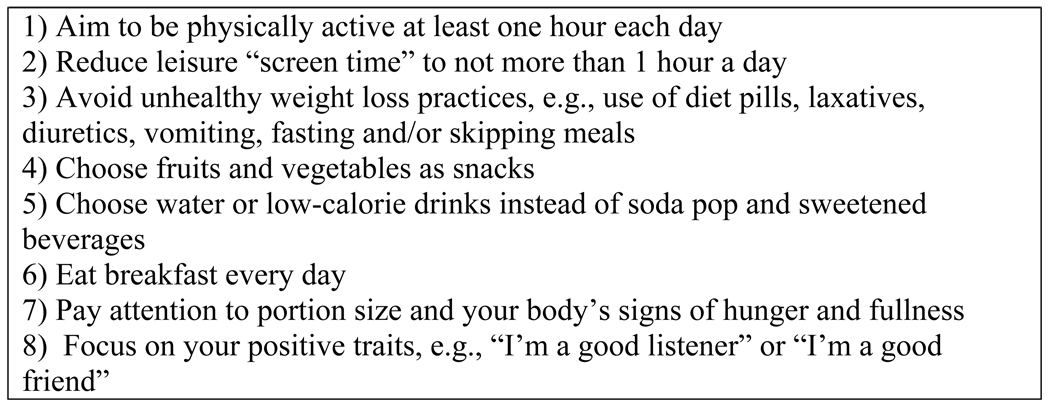

New Moves, a school-based obesity prevention intervention, was developed to address the specific needs of adolescent girls who are overweight or at risk for becoming overweight due to low levels of physical activity (3). Adolescent girls are at risk for a range of weight-related problems, including body dissatisfaction, unhealthy weight control behaviors, disordered eating behaviors, and obesity. New Moves incorporates concepts and strategies from both the eating disorder and obesity fields (4, 5). New Moves strives to provide an environment in which all girls feel comfortable being physically active, regardless of their size, shape or skill level. The program aims to 1) bring about positive change in physical activity and eating behaviors to improve weight status and overall health; 2) help girls function in a thin oriented society and feel good about themselves; and 3) help girls avoid unhealthy weight control behaviors. Specific behavioral objectives of New Moves provided to the girls through group and individual activities are listed in Figure 1. The primary component of the New Moves program is an all-girls physical education class, supplemented with activities aimed at improving eating patterns and self-image. High school girls elect to take the New Moves class for physical education credit. Findings from the original New Moves study, including input from participants, school staff and the research team clearly suggested a need for a more intense intervention with individualized attention beyond what could be provided in a group classroom setting (3). The combination of group and individual sessions was viewed as ideal given the social support provided by the group and the individualized attention during the sessions. However, the feasibility of doing so was very questionable with this population. Would the girls be interested in one-on-one coaching sessions? Would they adhere to the visit schedule? Would it be better face-to-face or over the telephone?

Figure 1.

Behavioral objectives for the New Moves intervention, an obesity prevention program for adolescent girls.

Counseling Method

Motivational interviewing, a type of counseling method, has been shown to be effective in clinical settings (6). Motivational interviewing has been defined as a directive, client-centered counseling style for eliciting behavior change by helping clients explore and resolve ambivalence (7). Compared with nondirective counseling, motivational interviewing is more focused and goal-oriented. Within motivational interviewing, counselors use several techniques to understand a person’s frame of reference, particularly via reflective listening. Elements of style (e.g., warmth and empathy) and technique (e.g., key questions and reflective listening) offer a practical approach for helping individuals increase their motivation or “readiness” to change (8–11). A key goal of motivational interviewing is to assist individuals in working through their ambivalence about behavior change, and it is particularly effective for those who are initially less ready to change (7, 8, 12). The participant is encouraged to identify aspects of their behavior that they would like to change and to articulate the benefits of and barriers to making that change. The coach’s role is to facilitate this process, help the participant think of ways to overcome difficulties, and help the participant set realistic goals for behavior change. The core motivational interviewing techniques include the use of reflective listening, rolling with resistance, agenda setting and eliciting self-motivational statements and change talk (13). Within motivational interviewing, information is presented in a neutral manner and the overall tone of the encounter is non-judgmental, empathic and encouraging. The model is explicitly different from the traditional patient education that relies heavily on direct questioning, providing information and advice given in the hope of changing behavior (14).

Over the past 10 years, there has been considerable interest by health practitioners in the use of motivational interviewing to promote behavior change (13–18). Motivational Interviewing has been used to modify diet and physical activity behaviors in adults, however, its use in the evidence base for obesity prevention and treatment for youth is just beginning to emerge (19–21). A pilot study was therefore conducted to assess the feasibility of implementing motivational interviewing driven individual sessions as a supplement to a classroom-based obesity prevention program for adolescent girls.

FEASIBILITY

Participant Recruitment and Intervention

New Moves is an all-girls physical education class that met weekly for nine weeks at an urban Minnesota high school as part of a pilot study. Participants were high school girls (N=41) ages 16–18 (mean age=17). The New Moves class consisted of three days of physical education and two days of classroom lessons which focused on nutrition and social support topics. Each class was 60 minutes in length.

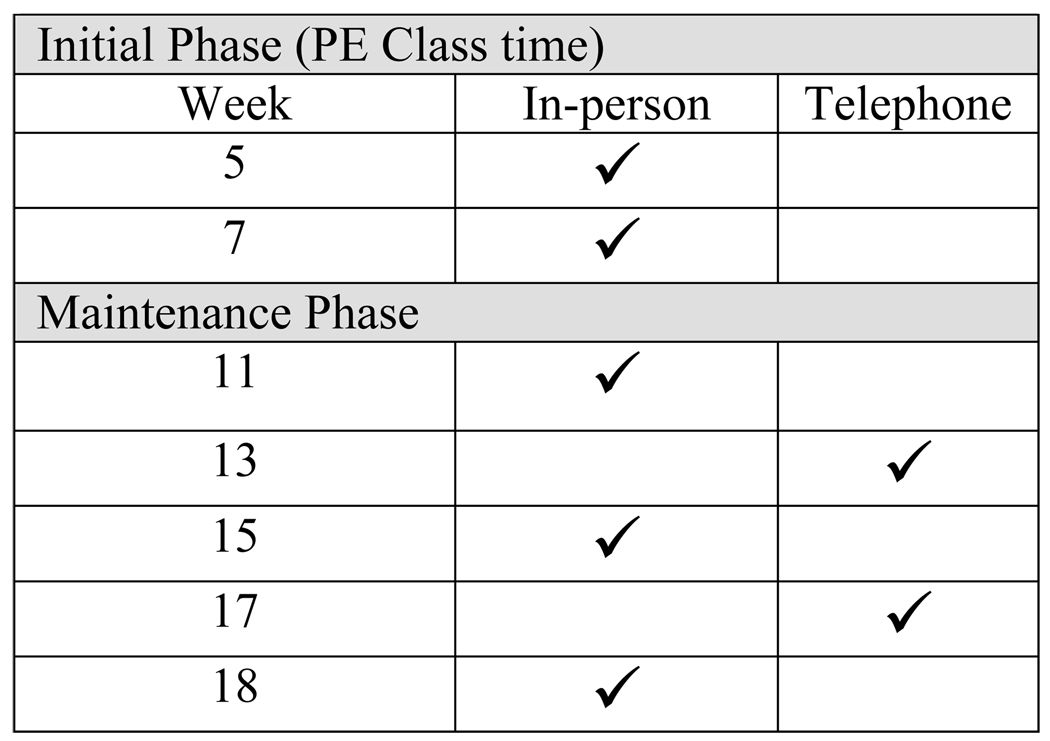

New Moves staff presented the individual sessions to participants as an opportunity to continue to work on their behavior goals, individually with a New Moves coach, following completion of the New Moves class. Twenty girls, participating in the New Moves class, volunteered for the individual session component, and met for a total of seven visits. The most common ethnic/racial background was white (n=11) followed by Asian (n=3), African American (n=2) and other (n=4). Two visits were completed during the nine-week New Moves class and five were conducted after class had ended in the second nine-weeks of the semester. Individual sessions were done both in person and via phone. Individual sessions were held approximately every two–three weeks to allow girls time to work on achieving their goal (Figure 2). A regular time (during a study hall or before/after school), day of the week and location (at school) was established for each of the five in-person sessions, and a predetermined time was arranged with participants for the phone sessions. Reminder notes were given to each participant the day prior to the session in order to maintain a regular and consistent meeting schedule. Each in-person session lasted about 20–25 minutes and the phone sessions about 10–15 minutes.

Figure 2.

Schedule of motivational interviewing coaching sessions for girls in the New Moves intervention, an obesity prevention program for adolescent girls.

Two members of the research team, one a Registered Dietitian (RD) and the other a health educator, participated in a 2-day training on motivational interviewing prior to the start of the intervention as well as attended weekly case management meetings throughout the pilot study. In addition to conducting individual sessions, the coaches also were responsible for teaching the nutrition and social support classroom lessons and therefore participants had contact with the coaches throughout the entire study period. Each participant was assigned to a New Moves coach and they worked together throughout the study. Written scripts were used incorporating motivational interviewing in each session. During the sessions, the personal coach established a non-confrontational and supportive climate in which girls could feel comfortable discussing their concerns and behavioral goals. The sessions were designed to put the girls in the active role of choosing and attaining their physical activity and eating goal(s). Individual goals were chosen by the girls; however they were encouraged to choose one of the eight behavioral objectives shown in Figure 1. The major tasks involved in each session were identifying barriers to behavior change and exploring strategies thereby supporting the girl’s autonomy and ability to make healthy lifestyle decisions around the New Moves behavioral objectives.

Analysis of Process Evaluation Data

After each individual session, coaches completed standardized process evaluation forms including attendance, length of session, whether a new goal was set, whether the goal was met, participant’s barriers to meeting behavior change goals, e.g., what makes it hard to eat in a healthy way or be physically active, and setting of an action plan. Notes from the field were entered in an Excel database (Microsoft Office Excel, Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA). Quantitative data were analyzed to get counts and averages. Qualitative data such as the type of goals set and barriers were coded and categorized. Emerging themes fell within three broad domains, physical activity, nutrition and social support. Frequencies were calculated for each domain. All research protocols were approved by the University of Minnesota’s Institutional Review board Human Subject Committee as well as the participating schools research board. Parental consent and student assent forms were collected and filed as part of the University Institutional Review Board requirements.

FEASIBILITY RESULTS

Among the 20 participants, 81% completed all seven of the individual sessions; 70% completed the two phone sessions and 85% completed the five face-to-face sessions. All of the participants completed the first two individual face-to-face coaching sessions during the New Moves physical education class time, while the remaining sessions were completed at lunch time, study hall or after school. All students were able to find a place and time to meet either before, during or after school. Participants that did not complete all individual sessions (19%) noted the following as common reasons: “I really don’t need the help this week”, “I forgot the meeting time”, and “I don’t know my schedule for next term so can’t plan”. Of those participants that missed sessions, the majority rescheduled at a later date and time.

Girls who completed an individual session set a goal 100% of the time. Goals fell into 3 categories, physical activity (53%), nutrition (30%) or social support (17%). Examples of goals included “run with dad 3x/week”, “use weight room at school 2x/week”, “eat breakfast every weekday”, “choose vegetables as snacks after school instead of chips”, “be happy with my progress”. Barriers to meeting behavior change goals were tracked. Examples of barriers were: “there are too many things to change”, “work schedule gets in my way”, “no way to get to gym”, “school commitments limit my time”, and “eat[ing] out with friends everyday”.

The majority of girls (90%) set at least two different goals during the study. As part of the sessions, girls were encouraged to reward themselves when goals were met. Girls chose their own reward and common rewards included getting a manicure, buying a CD, putting money in a jar each time they exercised, or going out with friends. Girls who completed an individual session reported meeting their goal the majority of the time (75%) and if not, the goal was reset or modified.

CONCLUSIONS

This current pilot study suggests that the implementation of individual sessions as a component of a school-based obesity prevention intervention is feasible. Attendance was high at both face-to-face and telephone sessions, although face-to-face was preferred over telephone interviews. Findings further suggest that motivational interviewing is a suitable tool for helping adolescent girls set individual behavioral goals regarding physical activity, eating behaviors, and self-empowerment. The addition of the individual sessions using motivational interviewing appeared to enhance behavior change, as well as maintained participation in the study based on the collected data on goals set and met. The intervention model tested in the current study provides an innovative strategy for reaching out to adolescents at risk for obesity within a school setting. However, study limitations including the small sample size and the inclusion of only process evaluation data, greatly limit our ability to draw firm conclusions from the findings, and suggest a need for an expanded study.

Motivational interviewing appears to have substantial promise for health behavior change in a school setting. Motivational interviewing has been found by others to be effective in increasing self-efficacy to endorse change in adolescents and young adults (22, 23). As in the current study, other researchers have used motivational interviewing for control of weight, diet and physical activity with similar feasibility results in pediatric clinical settings (19). However, to our knowledge this is the first study that has used motivational interviewing in a school-based setting (24–27). The participant-centered approach in which the coach-participant relationship is seen as a partnership, rather than an expert-recipient relationship resonates well with adolescent’s desire for independence, and competing demands. Motivational interviewing also provides a means for coaches to tailor their interventions to the participant’s readiness to change and to those who are ambivalent or not ready for change. Such tailored interventions are likely to allow participants to feel listened to and understood by their coach (28). Additionally, the coach may potentially gain a greater sense of achievement in motivating and helping promote health behavior change.

The results from this pilot program of a motivational intervention for adolescent girls are encouraging. Motivational interviewing sessions were viewed as effective by the personal coaches based on data evaluation forms and weekly case management meetings, showing girls attended their sessions, set goals and were successful in meeting their goals. This is particularly encouraging due to modest success from other school based obesity prevention efforts. This study suggests it is feasible to add an individual motivational interviewing component to school-based programs to strengthen the programs and help girls address barriers to behavior change. The combination of group and individual activities for school-based obesity prevention programs offers a promising strategy.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Colleen Flattum, Division of Epidemiology and Community Health, School of Public Health, University of Minnesota, 1300 South Second Street, Suite 300, Minneapolis, MN 55454, tel (612) 625-1016 fax (612) 626-7103, flattum@epi.umn.edu.

Sarah Friend, Division of Epidemiology and Community Health, School of Public Health, University of Minnesota, 1300 South Second Street, Suite 300, Minneapolis, MN 55454, tel (612) 626-8372 fax (612) 626-7103, friend@epi.umn.edu.

Dianne Neumark-Sztainer, Division of Epidemiology and Community Health, School of Public Health, University of Minnesota, 1300 South Second Street, Suite 300, Minneapolis, MN 55454, tel (612) 624-0880 fax (612) 626-7103, neumark@epi.umn.edu.

Mary Story, Division of Epidemiology and Community Health, School of Public Health, University of Minnesota, 1300 South Second Street, Suite 300, Minneapolis, MN 55454, tel (612) 626-8801 fax (612) 624-0315, story@epi.umn.edu.

References

- 1.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Rockville, MD: Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Institutes of Health; The Surgeon General's call to action to prevent and decrease overweight and obesity. 2001 [PubMed]

- 2.National Center for Health Statistics Centers for Disease Control. [Accessed January 5, 2002];Prevalence of overweight among children and adolescents: United States, 1999. Internet www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/pubs/pubd/hestats/over99fig1.htm.

- 3.Neumark-Sztainer D, Story M, Hannan PJ, Rex J. New Moves: A school-based obesity prevention program for adolescent girls. Prev Med. 2003;37:41–51. doi: 10.1016/s0091-7435(03)00057-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Irving LM, Neumark-Sztainer D. Integrating primary prevention of eating disorders and obesity: Feasible or futile? Prev Med. 2002;34:299–309. doi: 10.1006/pmed.2001.0997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Neumark-Sztainer D. Obesity and eating disorder prevention: An integrated approach? Adolesc Med: State of the Art Reviews. 2003;14:159–173. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hecht J, Borrelli B, Breger RK, DeFrancesco C, Ernst D, Resnicow K. Motivation Interviewing in Community-Based Research: Experiences From the Field. Ann Behav Med. 2005;29:29–34. doi: 10.1207/s15324796abm2902s_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rollnick SR, Miller WR. What is motivational interviewing? Behav and Cogn Psychother. 1995;23:325–334. doi: 10.1017/S1352465809005128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Resnicow K, Jackson A, Wang T, De AK, McCarty F, Dudley WN, Baranowski T. A motivational interviewing intervention to increase fruit and vegetable intake through Black churches: Results of the Eat for Life trial. Am J Public Health. 2001;91:1686–1693. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.10.1686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Harland J, White M, Drinkwater C, Chinn D, Farr L, Howel D. The Newcastle exercise project: A randomised controlled trial of methods to promote physical activity in primary care. BMJ. 1999;319:828–832. doi: 10.1136/bmj.319.7213.828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Resnicow K, Campbell MK, Carr C, McCarty F, Wang T, Periasamy S, Rahotep S, Doyle C, Williams A, Stables G. Body and soul. A dietary intervention conducted through African-American churches. Am J Prev Med. 2004;27:97–105. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2004.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Resnicow K, Jackson A, Blissett D, Wang T, McCarty F, Rahotep S, Periasamy S. Results of the healthy body healthy spirit trial. Health Psychol. 2005;24:339–348. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.24.4.339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational interviewing: Preparing people to change addictive behavior. New York: Guilford Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Resnicow K, DiIorio C, Soet JE, Ernst D, Borrelli B, Hecht J. Motivational interviewing in health promotion: It sounds like something is changing. Health Psychol. 2002;21:444–451. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rubak S, Sandbaek A, Lauritzen T, Christensen B. Motivational interviewing: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Gen Pract. 2005;55:305–312. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dunn C, Deroo L, Rivara FP. The use of brief interventions adapted from motivational interviewing across behavioral domains: A systematic review. Addiction. 2001;96:1725–1742. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2001.961217253.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Velasquez MM, Hecht J, Quinn VP, Emmons KM, DiClemente CC, Dolan-Mullen P. Application of motivational interviewing to prenatal smoking cessation: Training and implementation issues. Tob Control. 2000;9 Suppl 3:III36–III40. doi: 10.1136/tc.9.suppl_3.iii36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Emmons KM, Rollnick S. Motivational interviewing in health care settings. Opportunities and limitations. Am J Prev Med. 2001;20:68–74. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(00)00254-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kreman R, Yates BC, Agrawal S, Fiandt K, Briner W, Shurmur S. The effects of motivational interviewing on physiological outcomes. Appl Nurs Res. 2006;19(3):167–170. doi: 10.1016/j.apnr.2005.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Resnicow K, Davis R, Rollnick S. Motivational interviewing for pediatric obesity: Conceptual issues and evidence review. J Am Diet Assoc. 2006;106:2024–2033. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2006.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brennan L, Walkley J, Fraser SF, Greenway K, Wilks R. Motivational interviewing and cognitive behaviour therapy in the treatment of adolescent overweight and obesity: Study design and methodology. Contemp Clin Trials. 2008;29(3):359–375. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2007.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Burke BL, Arkowitz H, Menchola M. The efficacy of motivational interviewing: a meta-analysis of controlled clinical trials. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2003;71(5):843–861. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.71.5.843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brown RA, Ramsey SE, Strong DR, Myers MG, Kahler CW, Lejuez CW, Niaura R, Pallonen UE, Kazura AN, Goldstein MG, Abrams DB. Effects of motivational interviewing on smoking cessation in adolescents with psychiatric disorders. Tob Control. 2003;12 Suppl 4:IV3–IV10. doi: 10.1136/tc.12.suppl_4.iv3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Richards A, Kattelman KK, Ren C. Motivating 18- to 24-year-olds to increase their fruit and vegetable consumption. J Am Diet Assoc. 2006;106(9):1405–1411. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2006.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Resnicow K, Taylor R, Baskin M, McCarty F. Results of Go Girls: a weight control program for overweight African-American adolescent females. Obes Res. 2005;13:1739–1748. doi: 10.1038/oby.2005.212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Channon S, Smith VJ, Gregory JW. A pilot study of motivational interviewing in adolescents with diabetes. Arch Dis Child. 2003;88:680–683. doi: 10.1136/adc.88.8.680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Berg-Smith SM, Stevens VJ, Brown KM, Van Horn L, Gernhofer N, Peters E, Greenberg R, Snetselaar L, Ahrens L, Smith K. A brief motivational intervention to improve dietary adherence in adolescents. The Dietary Intervention Study in Children (DISC) Research Group. Health Educ Res. 1999;14:399–410. doi: 10.1093/her/14.3.399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Knight KM, Bundy C, Morris R, Higgs JF, Jameson RA, Unsworth P, Jayson D. The effects of group motivational interviewing and externalizing conversations for adolescents with type-1 diabetes. Psychol Health Med. 2003;8:149–158. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Campbell MK, Resnicow K, Carr C, Wang T, Williams A. Process evaluation of an effective church-based diet intervention: Body & Soul. Health Educ Behav. 2007;34(6):864–880. doi: 10.1177/1090198106292020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]