Abstract

The morphological and electrophysiological diversity of inhibitory cells in hippocampal area CA3 may underlie specific computational roles and is not yet fully elucidated. In particular, interneurons with somata in strata radiatum (R) and lacunosum-moleculare (L-M) receive converging stimulation from the dentate gyrus and entorhinal cortex as well as within CA3. Although these cells express different forms of synaptic plasticity, their axonal trees and connectivity are still largely unknown. We investigated the branching and spatial patterns, plus the membrane and synaptic properties, of rat CA3b R and L-M interneurons digitally reconstructed after intracellular labeling. We found considerable variability within but no difference between the two layers, and no correlation between morphological and biophysical properties. Nevertheless, two cell types were identified based on the number of dendritic bifurcations, with significantly different anatomical and electrophysiological features. Axons generally branched an order of magnitude more than dendrites. However, interneurons on both sides of the R/L-M boundary revealed surprisingly modular axo-dendritic arborizations with consistently uniform local branch geometry. Both axons and dendrites followed a lamellar organization, and axons displayed a spatial preference towards the fissure. Moreover, only a small fraction of the axonal arbor extended to the outer portion of the invaded volume, and tended to return towards the proximal region. In contrast, dendritic trees demonstrated more limited but isotropic volume occupancy. These results suggest a role of predominantly local feedforward and lateral inhibitory control for both R and L-M interneurons. Such role may be essential to balance the extensive recurrent excitation of area CA3 underlying hippocampal autoassociative memory function.

Keywords: Axons, Branching, Dendrites, Feed-forward Inhibition, Hippocampus, Lateral Inhibition, Stratum Lacunosum-Moleculare, Stratum Radiatum

Introduction

The diversity of cortical interneurons is reflected in molecular, electrophysiological, and anatomical features (Maccaferri and Lacaille, 2003; Klausberger and Somogyi, 2008). Expression patterns of neurotransmitter receptors and voltage-gated channels determine key biophysical properties, and molecular markers such as calcium-binding proteins and neuropeptides also identify specific neuronal types (Blatow et al., 2005; Toledo-Rodriguez et al., 2005; Sugino et al., 2006). Morphological studies provided essential insights into how interneurons function within the modular architecture of cerebral cortex (Douglas and Martin, 2004) and subfields of hippocampus (Bernard and Wheal, 1994). Particularly important in this regard have been technical advances permitting three-dimensional rendering of entire neurons from serial sections rather than camera lucida tracing of cells within a single section (Ascoli, 2006). Quantitative morphometric analysis of dendritic and, especially, axonal arbors from these detailed digital reconstructions yielded recent breakthroughs into neuronal function within larger circuits (Shepherd et al., 2005; Stepanyants et al., 2008). The power of this approach has recently increased by combining morphometric and electrophysiological analysis in neocortical interneurons (Dumitriu et al., 2007; Helmstaedter et al., 2008). In the study of hippocampal interneurons, however, this combined characterization has to date been largely limited to the dentate gyrus (Mott et al., 1997), CA1 dendritic trees (Gulyas et al., 1999), or tangential observations (McQuiston and Madison, 1999)

In the hippocampus, area CA3 plays prominent roles in memory function (McNaughton and Morris, 1987; Treves and Rolls, 1992) and pathological conditions such as epilepsy (Avoli et al., 2002; Fisahn, 2005). The CA3 circuitry is distinguished by preponderant recurrent collaterals among pyramidal cells, and converging laminar excitation from the entorhinal perforant path and dentate mossy fibers (Witter et al., 1988; Witter, 2007). This organization may subserve the complementary abilities of CA3 to minimize recall errors by “pattern completion” and to decorrelate incoming cortical firing patterns into distinct events by “pattern separation” (Lisman, 1999; O'Reilly and McClelland, 1994; Leutgeb et al., 2007). Interneurons with soma in strata radiatum (R) and lacunosum-moleculare (L-M) of area CA1 have been shown to modulate the entorhinal influence on pyramidal cells (Freund and Antal, 1988) through feedforward inhibition (Kunkel et al., 1988; Khazipov et al., 1995; Savič et al., 2001; Cope et al., 2002; Christie et al., 2000; Martina et al., 2003). Although R and L-M interneurons in area CA3 have not benefited from similar detailed analysis, they are major recipients of glutamatergic input (Buhl et al., 1994; Gulyas et al., 1993) from recurrent collaterals (RC), perforant path (PP), and mossy fibers (MF). In turn, R and L-M interneurons modulate CA3 pyramidal activity through dendritic shunting and somatic inhibition (McBain and Fisahn, 2001; Romo-Parra et al., 2008).

At least some of the excitatory inputs to R and L-M interneurons in CA3 exhibit several forms of long-term synaptic plasticity (LTP/LTD) triggered by a rise in cytosolic Ca2+ concentration (Laezza et al., 1999; Kullman and Lamsa, 2007). Unlike in pyramidal cells, however, the differential expression of glutamate receptor subtypes in hippocampal interneurons may yield predominantly calcium-permeable (CP) or calcium-impermeable (CI) AMPARs containing synapses (McBain and Fisahn, 2001; Kullman and Lamsa, 2007; Galvan et al., 2008). Distinct AMPAR unit composition could underlie the multiplicity of interneuron synaptic plasticity, particularly with respect to the mechanisms controlling the induction and polarity of long-term modifications. Although the layer location of the soma is not generally regarded as a significant criterion for interneuron classification (Klausberger and Somogyi, 2008), considerable differences in LTP/LTD mechanisms between CA3 R and L-M interneurons raise the possibility that synaptic plasticity in these interneurons could be layer-dependent (Ziakopoulos et al., 1999). Specifically, changes in synaptic strength in R interneurons are induced at predominately CP-AMPAR synapses whereas cells expressing mostly CI-AMPA receptors lack use-dependent plasticity (Laezza et al., 1999). Depending on the membrane potential, high-frequency stimulation (HFS) leads to either LTP or LTD (Laezza and Dingledine, 2004). In contrast, bidirectional plasticity in L-M interneurons occurs solely at predominantly CI-AMPAR containing synapses, and is contingent on the activation of L-type Ca2+ channels and the availability of mGluR1α (Galvan et al., 2008). It is thus possible that R and L-M interneurons might be distinguished on the basis of the mechanisms underlying long-term plasticity.

Persistent changes in the strength of the excitatory input to interneurons will affect the input-output relationship between principal cells, the excitability of the neuronal network, and the generation of rhythmic oscillations. Therefore, the degree to which different forms long-term synaptic plasticity are segregated in specific layers may represent a relevant functional component of information processing and dynamics in area CA3 (McBain and Maccaferri, 1997). Recent evidence from the neocortex indicates that structural remodeling of adult dendrites in GABAergic interneurons might also be selectively limited to a layer-specific “dynamic zone” (Lee et al., 2008). Synaptic plasticity may be an important determinant in the classification of neocortical and hippocampal interneurons alike, especially if complemented with the quantitative morphological characterization of both axons and dendrites, which subserve network connectivity. In the present investigation we sought to gain further insight into the diversity and possible functional roles of hippocampal interneurons through detailed morphometric analysis of electrophysiologically identified CA3b R and L-M cells.

Materials and Methods

Slice preparation

Animal use was in accordance with the University of Pittsburgh Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Male Sprague-Dawley rats (22±4 days old) were deeply anaesthetized with Nembutal, perfused intracardially with modified artificial cerebrospinal fluid, and decapitated. Tissue blocks containing the hippocampus were sectioned (350 μm/section) at an angle of 30° to the long axis of the hippocampus with a Leica VT1000S vibratome. Slices were maintained for at least 60 min at room temperature in an incubation solution (composition in mM: 125 NaCl, 2.0 KCl, 1.2 NaH2PO4, 25.0 NaHCO3, 10.0 glucose, 1.0 CaCl2 and 6.0 MgCl2; pH 7.4) with bubbled O2 (95%)–CO2 (5%). The slices were then transferred to a submerged recording chamber and superfused at constant flow (2.5 ml/min) with the following solution (in mM): 125 NaCl, 3.0 KCl, 1.25 Na2HPO4, 25 NaHCO3, 2.0 CaCl2, 1.0 MgCl2, 10 glucose, 0.01 bicuculline; 0.05 D-2-amino-5-phosphonopentanoic acid (AP5), pH 7.4 at 33±1°C.

Recording and stimulation techniques

Somata of interneurons in stratum radiatum (R) and stratum lacunosum-moleculare (L-M) of hippocampal area CA3b (60-80 μm from the slice surface) were identified by infrared-differential interference contrast (IR-DIC) optics of a Zeiss FS2 microscope (Carl Zeiss, Germany) fitted with a water immersion objective (40× or 60×). Patch pipettes with electrical resistances of 3–6 MΩ were pulled from borosilicate glass and filled with a solution containing (in mM: 120 potassium methylsulphate, 10 KCl, 10 Hepes, 0.5 EGTA, 4.5 Mg.ATP, 0.3 Na2GTP, 14 phosphocreatine. Biocytin, 0.5% (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR, USA) was routinely added to the pipette solution to allow subsequent morphological identification and reconstruction of the neurons. Current clamp recordings were obtained with a Cornerstone amplifier (Model: BVC-700A, Dagan Corp., Minneapolis, MN, USA); voltage clamp recording were obtained with an Axoclamp-1D amplified (Axon Instruments, Union City, CA, USA). Membrane potential was measured after breaking into whole cell mode, and was not corrected for changes in junction potential. Whole cell recordings were accepted only if seal resistance was ≥2 GΩ and if the resting membrane potential was more negative than -65 mV. Signals were low-pass filtered at 3–5 kHz, digitized at 10 or 20 kHz, and stored on disk for off-line analysis. Data acquisition and analysis were performed using LabView (National Instruments, Austin, TX, USA) using customized programs.

Extracellular stimulation with bipolar nichrome electrodes (62 μm in diameter) consisted of single monopolar pulses (100-300 μA, 50-100 μs, 0.2 Hz). To activate the perforant path (PP) and minimize the spurious activation of mossy fibers (MF), the stimulation electrode was placed in stratum lacunosum-moleculare of area CA1 far from CA3, and close to the hippocampal fissure (Henze et al., 1997). In addition, the probability of antidromic stimulation of CA3 pyramidal cells and activation of CA3 collaterals was reduced by applying low current intensities resulting in responses with amplitude < 30% of the threshold required to fire the interneurons. Earlier current source density analysis (Berzhanskaya et al., 1998) showed a large sink restricted between 50 and 150 μm from the hippocampal fissure and a current source in stratum radiatum, followed milliseconds later by a current source in the CA3 stratum pyramidale, indicating specific activation of PP synapses. The MF pathway was activated by placing the stimulating electrode in the medial extent of the suprapyramidal blade of the dentate gyrus. The recurrent collateral pathway (RC) was activated by placing an electrode in the stratum pyramidale of area CA3b.

Electrophysiological data analysis

Input resistance (Ri) reported here is the slope of the best-fit line to the linear portion of the relation between the injected current step (500 ms, 5-20 pA, 3-5 sweeps each at 0.2 Hz) and the membrane potential at the end of the step. Membrane time constant (τ) was determined by fitting a single exponential to the response to long (500 ms) hyperpolarizing current steps (−10 to −30 pA). Action potential (AP) amplitude and threshold were measured for each spike in a train evoked by depolarizing current injections. AP amplitude was determined from the AP threshold to the peak of the spike. AP threshold was computed by initially determining the AP peak from the membrane potential first derivative, and then by looking back to the point where the membrane potential third derivative changed from negative to positive (Henze et al., 2000). The afterhyperpolarization (AHP) was measured from AP threshold to the hyperpolarization peak. The spike adaptation ratio (AR) of the first to last interspike interval within a sweep was quantified upon a depolarizing step of 150 pA above the current threshold for the first spike for each cell (Porter et al., 2001). Based on this measure, interneurons were grouped either as adapting (AR > 1.3) or nonadapting (AR < 1.25). The quantitative analysis of the EPSPs was performed using customized programs written in Lab View. For measuring EPSP amplitude, cursors were positioned 5 ms before the stimulation artifact and at 100 ms after the onset of the EPSP. The EPSP rise was determined by subtracting the times corresponding to 20% and 80% of the value of EPSP peak amplitude. The EPSP decay time constant was calculated between 1-3 ms after the EPSP peak amplitude and the end of the EPSP waveform. We used a third order exponential function to fit the decay of the EPSP.

Cell labeling, digital reconstruction, and public availability of data

Following recordings, slices were fixed in cold 4% paraformaldehyde for 72 h and transferred into an antifreeze solution (1:1 mixture of glycerol and ethylene glycol in 0.1 m phosphate buffer). Slices were then resectioned at 60 μm using a freezing microtome, reacted with 1% H2O2 to reduce endogenous peroxidase reactivity and placed in blocking serum with 0.5% Triton X-100 for 2 h at room temperature. Biocytin-labeled neurons were revealed using the Vectastain Elite kit (Vector Laboratories) and the resulting diaminobenzidine reaction product was intensified with nickel ammonium sulfate to produce a blue-back reaction product. Cells were photographed using using a Zeiss Axioplan photomicroscope equipped with a Hamamatsu digital camera (Hamamatsu Photonics, Hamamatsu, Japan). The contrast and brightness of individual images was manually adjusted with Adobe Photoshop software for optimal clarity and the final plates were assembled using Adobe Illustrator software.

All interneurons were reconstructed by the same operator using the Neurolucida tracing system (MicroBrightField, Inc., Williston, VT, USA) attached to a Nikon Optiphot-2 photomicroscope equipped with a 100× planapochromatic lens (NA=1.4) and additional Optovar magnification of 1.6× (final optical magnification, 1600×; screen magnification, 7200×). The cell and all labeled processes were faithfully mapped in all serial sections that contained labeled profiles. Processes were color coded as dendrites or axons based upon morphological features. Processes that progressively decreased in cross sectional diameter with increasing distance from the cell soma and with each bifurcation were classified as dendrites. Axons consisted of highly branched process that exhibited numerous en passant boutons separated by intervaricose segments of uniform diameter.

The entire somatodendritic compartment of each labeled neuron, as well as the full extent of the axonal arbor, was reconstructed from all sections containing labeled profiles. This was achieved by maintaining the serial order of 60 μm sections cut on the freezing microtome, mapping all labeled profiles within each section, and then using anatomical landmarks to align sections in the appropriate registration. Labeled portions of the same processes identified in adjacent sections were then used to make the final alignment of all labeled profiles. The final reconstruction was produced by repeating this process for all adjacent sections that contained labeled profiles and merging the maps into a single file using Neurolucida software. The final Neurolucida output (.asc) files were converted to the non-proprietary SWC format (Ascoli et al., 2001) with the freely available L-Measure software (Scorcioni et al., 2008; http://krasnow.gmu.edu/cn3). The visualization and editing application Cvapp (Cannon et al., 1998) was then employed together with a semi-automated quality-check process (Halavi et al., 2008) to find and adjust connectivity inconsistencies, as well as to correct for shrinkage in the depth of the slice (Z coordinate). The shrinkage factor, measured by focusing on the top and bottom of each section and dividing this distance by the nominal slice thickness, ranged between 0.53 and 0.76.

All reconstruction files of both axons and dendrites are publicly available for download at NeuroMorpho.Org (Ascoli et al., 2007). Some dendritic reconstructions previously collected by other investigators were also obtained from this same archive in the course of our study for the purpose of comparative analysis, as described in the Results section. We note that NeuroMorpho.Org also currently contains 29 interneurons from area CA1 of the mouse (Yuste archive) with three-dimensional reconstructions of the axonal arbor. However, since these morphologies have not yet been described in the published literature, we refrained from including their quantitative analysis in this report.

Quantitative morphometry

Morphological reconstructions were digitally represented as a series of tubular compartments corresponding to a pair of tracing points, and specified by their type (axon vs. dendrite), three-dimensional coordinates, thickness, and internal (parent-to-child) connectivity (Ascoli, 2006). Following the conventional “Petilla” terminology (Ascoli et al., 2008), we refer to an internal or terminal branch as the portion between two bifurcations and between a bifurcation and a termination, respectively. We further define a tree as the collection of interconnected branches stemming from the soma, and an arborization as the set of trees in a neuron. Morphometric parameters were extracted with L-Measure and with the Neurolucida analysis tool NeuroExplorer (Glaser and Glaser, 1990). Many of these morphometrics are self-explanatory, but a few are explained below.

The branch order is the number of bifurcations in the path to the soma. Path distance measures the length along the neurite, as opposed to Euclidean distance, which measures the straight line. Taper rate records the diameter change as the ratio between the ending and starting points of each branch. The bifurcation diameter drop is the ratio between the diameters of the parent and the largest of the child branches. The bifurcation amplitude and tilt angles are delineated by the two child branches, and by the parent and the most bent child, respectively. The partition asymmetry equals |N1-N2|/(N1+N2-2), where N1 and N2 are the number of terminals each child of the bifurcation leads to. Contraction measures the tortuosity of dendritic or axonal meandering as the ratio between the path and Euclidean lengths of each branch. The fractal dimension captures the space-filling qualities of a structure, and can be specified locally for individual branches or globally for the whole neuron with the caliper and box-counting methods, respectively (Smith et al., 1996). Principal component analysis determines the orientation of the three orthogonal axes that are best aligned with an arborization. The isotropy of the arbor, computed as the ratio between the minor and major axis components, is close to 1 for spherical shapes and to 0 for planar or elongated shapes. Many morphometrics can be characterized as functions of distance from the soma (Sholl-like diagrams) or within binned angular deviations relative to the soma (polar histograms).

The longitudinal spread of a given cell was estimated as twice the standard deviation of the Euclidean distances of all tracing points from the soma in the septo-temporal direction. This measure approximates the 95% distribution range along the longitudinal hippocampal axis. Similarly, the transverse spread is twice the standard deviation of the Euclidean distances of all tracing points from the soma in the plane defined by the directions from CA3a to CA3c and from the hippocampal fissure to the alveus. The lamellar ratio is the transverse spread divided by the longitudinal spread, and describes the tendency of a cell to be confined perpendicular to the septo-temporal extent. Space occupancy was analyzed by dividing the smallest sphere centered at the soma and containing the entire neuron either into two hemispheres separated by one of three orthogonal planes defined by the axes described above (longitudinal, CA3a/CA3c, and fissure/alveus), or into eight sectors. The volume of all branches in each hemisphere or sector was then summed for statistical comparison.

Statistical analysis

Mann-Whitney non-parametric U tests were performed to compare anatomical, electrophysiological and morphometric measures between cell groups. Significance was determined by 2-tailed exact (as opposed to asymptotic) p values unless otherwise noted. Kolmogorov-Smirnov D test was employed to determine whether the number of dendritic branches for each cell was consistent with a single cell type, using uniform or Poisson distributions compatible with the low integer values. Pearson's R was computed to quantify the correlation between measurement pairs, with p values indicating the probability of two independent distributions. The uniformity of space occupancy across multiple sectors was checked with the Kruskall-Wallis H test, with a post hoc Mann-Whitney to extract significant binary differences between sectors/groups. False Discovery Rate was used to adjust for multiple comparisons where appropriate. All regression lines were obtained by residual error minimization.

Results

Whole-cell recordings were obtained from a total of 79 interneurons with somata located in the stratum radiatum (R; N = 23) and stratum lacunosum-moleculare (L-M; N = 56) of the CA3b area. The somata of R and L-M interneurons included in this analysis were positioned 147 ± 9.0 μm and 257.2 ± 10.2 μm from the boundary between the strata pyramidale and lucidum, respectively, and approximately 250 μm from the medial extent of the suprapyramidal blade of the dentate gyrus (Calixto et al., 2008). Thirteen electrophysiologically characterized cells (6 R and 7 L-M interneurons) had sufficient axonal and dendritic labeling within serial sections to produce complete three-dimensional digital reconstructions using all labeled profiles. The anatomical localization of somata for these cells is reported in Table 1. Only somatic distance from the stratum lucidum/pyramidale boundary is significantly different among subgroups of neurons. This difference is expected for two cell groups located in different layers (L-M cells are found further away from the stratum lucidum/pyramidale boundary).

Table 1. Anatomy and localization of R and L-M interneuron somata.

| Somatic feature | R μ ± σ (N=7) | LM μ ± σ (N=6) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Somatic surface area (μm2) | 1221.29±772.60 | 748.68±527.74 | 0.13 |

| Depth in the slice (μm) | 183.79±28.52 | 143.90±21.40 | 0.06 |

| Distance from SP/SL boundary (μm) | 122.00±12.87 | 277.03±81.80 | 0.001** |

| Distance from septal/dorsal pole (mm) | 1.49±0.11 | 1.63±0.41 | 0.95 |

| Distance from bregma (mm) | 2.26±0.15 | 2.45±0.67 | 0.95 |

| Distance from midline (mm) | 2.50±0.08 | 2.52±0.08 | 0.73 |

| Distance from DG suprapyramidal blade tip (mm) | 2.40±0.00 | 2.33±0.16 | 0.70 |

significant after false discovery rate correction

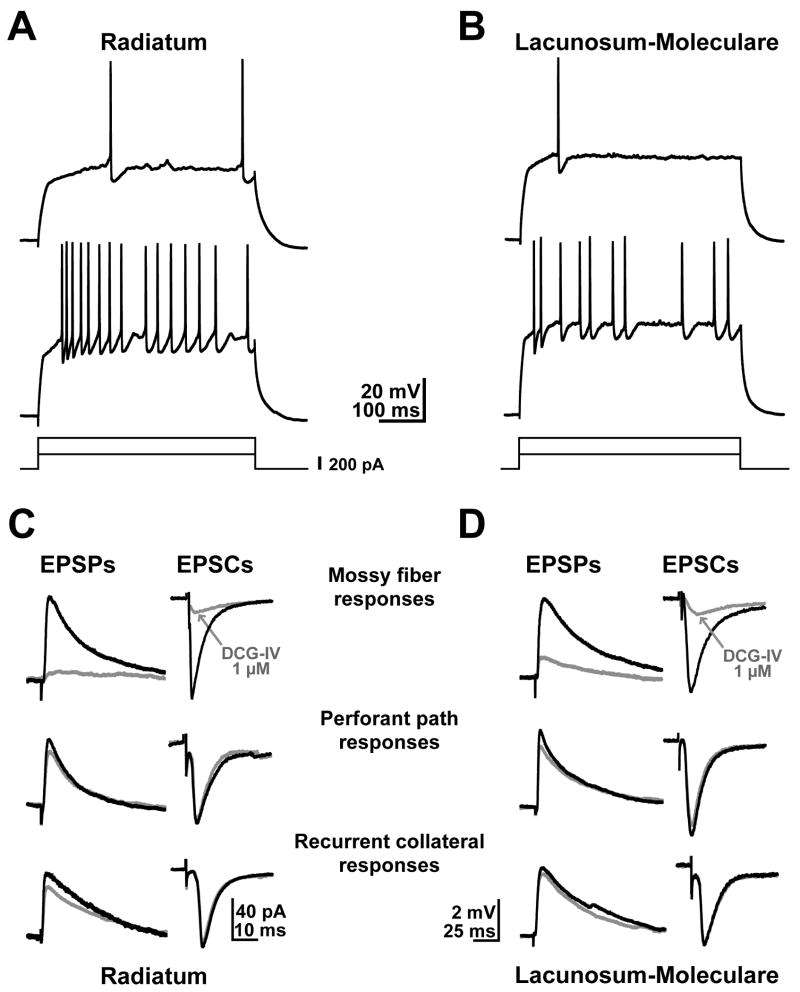

R and L-M interneurons have similar passive and active membrane properties

To determine if R and L-M interneurons could be recognized on the basis of distinct physiological properties, we measured passive and active membrane parameters. Comparable sets of electrophysiological data were obtained from the two interneuron classes at a membrane potential close to -70 mV. These data for the 13 interneurons included in the morphometric analysis are summarized in Table 2. The passive properties did not appear to vary between these two groups of neurons, suggesting a lack of physiological distinction between cells segregated by the anatomical position of their somata. Although across individual cells there was considerable variability of interspike intervals in response to depolarizing current injections, R and L-M interneurons showed similar strong adaptation ratios as a group (AR = 3.24 ± 1.88 and 3.05 ± 1.04 for R and L-M interneurons, respectively; Fig. 1A and B; Table 2).

Table 2. Passive and active physiological properties of R and L-M interneurons.

| Membrane properties | R μ ± σ (N=7) | LM μ ± σ (N=6) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adaptation ratio | 3.24±1.88 | 3.05±1.04 | 0.73 |

| Resting membrane potential (mV) | -71.43±4.20 | -72.17±5.64 | 0.84 |

| Input resistance (MΩ) | 170.14±35.23 | 218.00±73.92 | 0.14 |

| Action potential amplitude (mV) | 74.00±7.09 | 73.83±5.98 | 0.53 |

| Action potential duration (ms) | 0.91±0.22 | 0.77±0.24 | 0.53 |

| Action potential threshold (mV) | -44.43±3.64 | -44.67±3.67 | 0.63 |

| Afterhyperpolarization amplitude (mV) | 11.71±1.80 | 12.50±3.21 | 0.73 |

Figure 1.

Electrophysiological characteristics of R and L-M interneurons in area CA3b. A, B. Examples of membrane responses and firing patterns elicited by low and high depolarizing current injections (240 pA, upper traces, and 510 pA, lower traces, respectively). The membrane potential was -70 mV. Adaptation ratio: 4.0 and 2.2 for the R and LM interneuron, respectively. C, D. Samples of average (10 sweeps) EPSPs and EPSCs evoked from three excitatory pathways innervating R and LM interneurons. Only mossy fiber responses show high sensitivity to the application of the group II mGluR agonist, DCG-IV (1 μM, red traces, DCG-IV sensitivity 79 ± 7 % for EPSPs and 82.9 ± 5% for EPSCs).

Several of these measurements can be contrasted with previously reported independent data (Chitwood et al., 1999) from the same animal strain and age, in matching hippocampal region and layers, and from similar group sizes (5 R and 7 L-M). Although the absolute values of the input resistance cannot be compared directly since they were recorded at room rather than physiological temperature in that earlier study, their measurements were also very similar between R and L-M cells (within 5% of the mean). Similarly, the difference in average time constants between the two cell groups was well within the respective standard deviations in both studies (Chitwood et al., 1999; Calixto et al., 2008).

Isolated AMPAR-mediated EPSPs in R and L-M interneurons

Area CA3 receives two converging excitatory inputs from the entorhinal cortex. One input is conveyed monosynaptically via the perforant path (PP) by axons of layer II stellate cells of entorhinal cortex (Segal and Landis, 1974; Steward and Scoville, 1976), and the other input is conveyed disynaptically via the mossy fibers (MF) by axons of the dentate gyrus granule cells, which also are the targets of the same entorhinal layer II neurons (Tamamaki and Nojyo, 1993). Since R and L-M interneurons have dendrites that extended into the strata lacunosum-moleculare and lucidum, they could receive input from PP and MF, respectively. The granule cells may provide additional excitatory input to the dendritic branches in the stratum lacunosum-moleculare coursing near the dentate suprapyramidal blade via the MF traveling toward stratum lucidum, and via the MF collateral plexus in the hilus of the dentate gyrus (Acsády et al., 1998; Claiborne et al., 1986). In addition, interneurons also receive excitatory input from CA3 pyramidal neurons via recurrent collaterals (RC) of the axons forming the Schaffer commissural/collaterals to CA1 (Li et al., 1994).

In the presence of bicuculline and AP5, subthreshold AMPAR mediated EPSPs (range 2-4 mV) were recorded somatically from R and L-M interneurons at a resting potential around -70 mV by stimulating MF, PP or RC (Table 3). Application of the agonist for group-II metabotropic receptors (2S,2′R,3′R)-2-(2′3′-dicarboxycyclopropyl) glycine (DCG-IV; 1 μM) selectively reduced MF EPSPs (47.3 ± 3.2 % of control; p<0.001; data not shown), as previously reported (Calixto et al., 2008). The EPSP waveforms from all three pathways have similar kinetics suggesting that synapses were located at comparable electrotonic distances from the soma (Figure 4C,D). For example, the decay constant was 27.96 ± 2.40 ms (μ ± σ) for MF, 30.62 ± 3.20 ms for RC, and 27.23 ± 2.35 ms for PP. In contrast, while the amplitude was similar for MF and PP (3.05 ± 0.17 mV vs. 2.89 ± 0.20 mV, respectively), the value was lower for RC (1.98 ± 0.33 mV), possibly indicating a lower density of AMPA receptors in this postsynaptic region. Nevertheless, all synaptic properties for each of the three pathways were nearly identical between R and L-M interneurons (Fig. 1C and D; Table 3).

Table 3. Properties of MF, PP and RC EPSPs in R and L-M interneurons.

| Synaptic Properties | R μ ± σ (N=7) | LM μ ± σ (N=6) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| MF 20-80% rise (ms) | 2.01±0.16 | 2.02±0.15 | 0.84 |

| MF τ decay (ms) | 28.36±3.20 | 27.5±1.05 | 0.37 |

| MF amplitude (mV) | 2.96±0.08 | 3.15±0.19 | 0.06 |

| PP 20-80% rise (ms) | 1.79±0.13 | 1.93±0.23 | 0.23 |

| PP τ decay (ms) | 27.29±3.20 | 27.17±0.98 | 0.53 |

| PP amplitude (mV) | 2.91±0.19 | 2.87±0.23 | 0.73 |

| RC 20-80% rise (ms) | 2.67±0.50 | 2.67±0.39 | 0.95 |

| RC τ decay (ms) | 30.50±2.59 | 30.71±3.86 | 0.84 |

| RC amplitude (mV) | 2.05±0.45 | 1.93±0.20 | 0.95 |

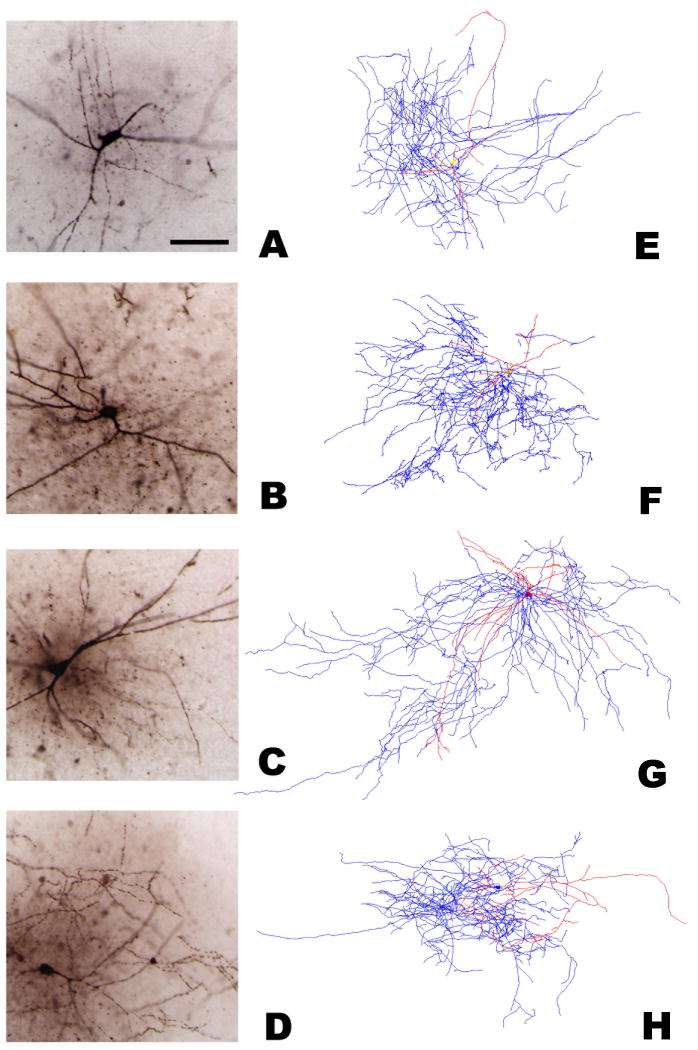

Figure 4.

Cropped images around the somata and proximal processes of four illustrative cells used in the analysis (A-D), along with their digital reconstruction (E-H). R (panels A/E and C/G) and L-M (B/F and D/H) groups are defined by somatic location. These examples also represent the distinction between cells with high (panels A/E and B/F) and low (C/G and D/H) numbers of dendritic branches. Dendrites (red) have been thickened 5-fold to help distinguish them from axons (blue). All photomicrographs are of the same magnification; scale bar in A: 100 μm.

R and L-M interneurons have different forms of long-term synaptic plasticity

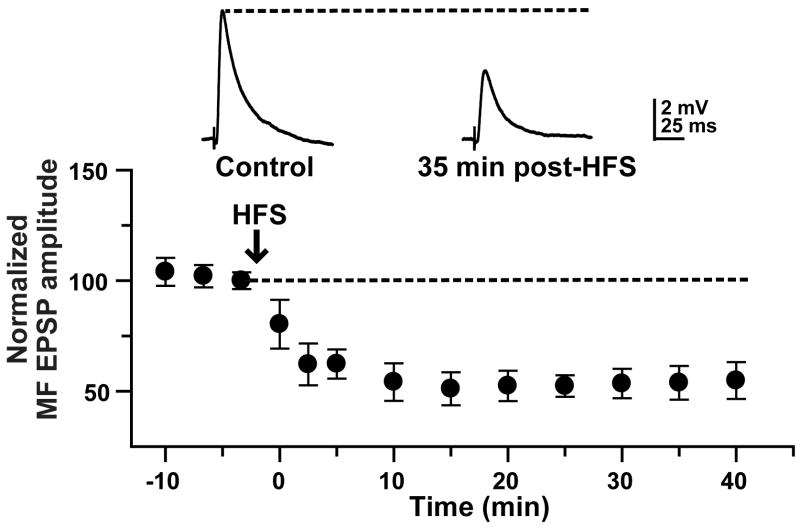

We have previously reported that high-frequency stimulation (HFS) delivered to the MF pathway induces LTP in the majority (>90%) of L-M interneurons (Galvan et al., 2008). In contrast, we found robust LTD in the population of reconstructed R interneurons shown here (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

R interneurons show predominantly MF LTD. HFS (3 trains of 100 pulses each at 100 Hz, repeated every 10 sec) delivered to the mossy fibers induced robust synaptic depression in current-clamp recordings (-70 mV) at 35 min post-HFS (40.69 ± 3.89 % of the control EPSP amplitude; p< 0.0001, unpaired t test; N=7). Insets are average MF EPSP (10 sweeps) from a typical experiment.

General appearance of R and L-M interneurons

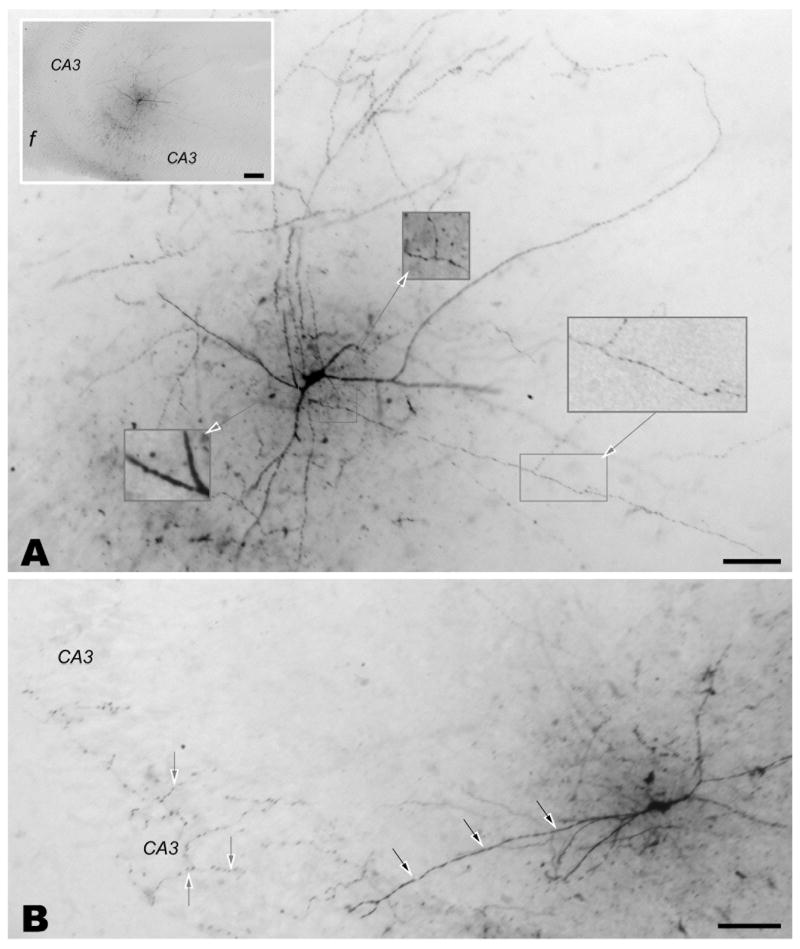

Micrographs of a sample of the cells reconstructed and analyzed in this study are shown in Figure 3. The somata of the majority of neurons in each class were bipolar, with primary dendrites arising from the polar extremes of the cells and the long axis of the cell oriented principally in the horizontal plane. Each cell had 1 to 6 typically aspiny dendritic trees stemming from the soma (μ ± σ = 3.08 ± 1.26). In both categories of interneuron, dendrites branched profusely through both strata radiatum and lacunosum-moleculare. The number of dendritic bifurcations varied widely from cell to cell over an order of magnitude. Typically, the long axis of the dendritic tree of R interneurons extended between the dorsal blade of the dentate gyrus and the stratum pyramidale of CA3. Distal branches of the ventrally oriented primary dendrites of each cell extended into the stratum lucidum, and in some cases, into the immediately adjacent stratum pyramidale (Figure 3). The dendritic arbors arising from L-M interneurons were typically oriented more horizontally with respect to the mediolateral axis of the hippocampus compared to R interneurons. Nevertheless, the distal branches of the dorsally and ventrally oriented primary dendrites were similar to R interneurons.

Figure 3.

Representative micrographs of CA3b interneurons typical of cells selected for quantitative morphometric analysis. Such cells exhibited dense labeling of both the somatodendritic compartment and axonal arbor in multiple serial sections. Panels A and B demonstrate the dense labeling of both dendrites and axons. The boxed areas in panel A illustrate the smooth fiber morphology characteristic of dendrites (lower left box) and the varicose nature of axons (two remaining boxes). Note the localized arborization of both classes of process with respect to the cell soma evident at both high and low magnification (inset: f, fimbria). This distinction is also evident in panel B where black arrows identify a long sparsely branching dendrite and varicose axons (gray arrows) branch prolifically within stratum pyramidale of CA3. All scale bars are 100 μm (panels A and B, and inset of A).

Neurons in both classes gave rise to elaborated axonal arbors, which often extended beyond their layer of somatic residence into stratum radiatum (for L-M interneurons) and strata lacunosum-moleculare or pyramidale (R cells). However, unlike the recently described GABAergic hippocampal cells projecting to the medial septum (Takacs et al., 2008), the majority of these axonal arbor was concentrated near the soma, suggesting local connectivity for all cells. A quantitative analysis of the dendritic and axonal patterns with respect to the major hippocampal axes and planes is reported at the end of this Results section. Figure 4 shows four representative reconstructions with both axonal and dendritic arborizations. Of these examples, two cells are from R (panels A and C) and two from L-M (B and D). These neurons are further distinguished by dendritic branching as having either low (≤10; panels A and B) or high (≥18; C and D) numbers of dendritic bifurcations.

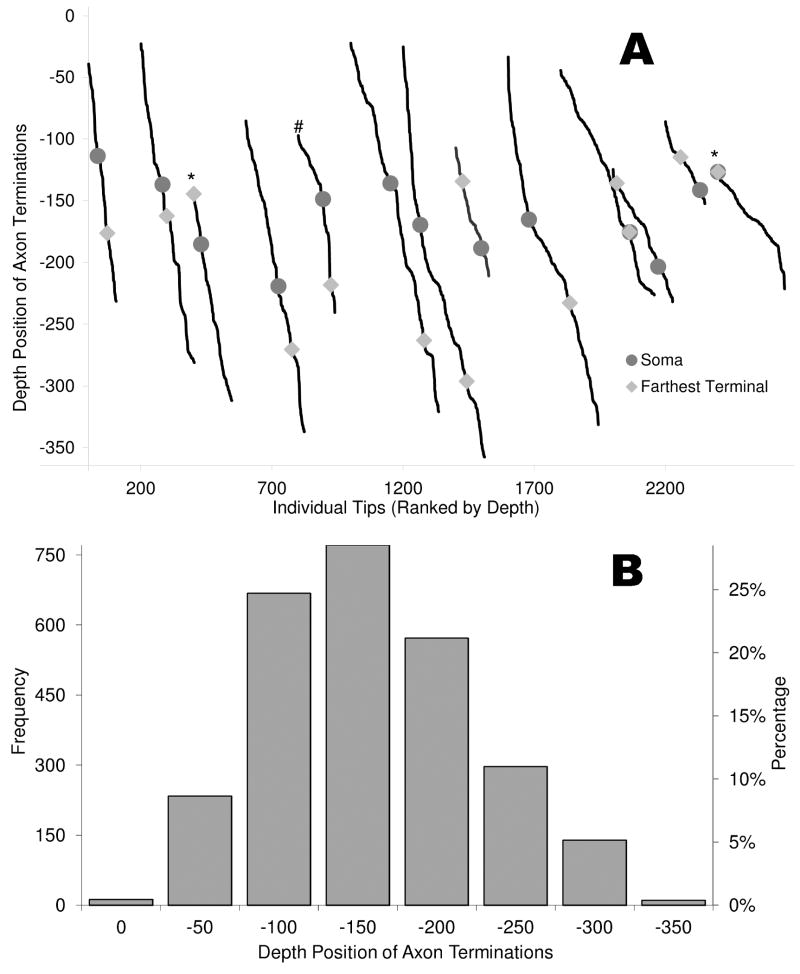

In order to test for potential truncation artifacts introduced by slice sectioning, the distribution of axonal terminal tips was plotted for each cell against the depth (Z coordinate; Figure 5). In the top panel, the abscissa ranks the tips by depth, with an additional offset (for visual display) between cells. If the slice thickness constitutes a limiting constraint to the Z spread, one should detect a disproportionally larger percentage of terminations at the extreme top and/or bottom locations. In contrast, this distribution was uniform, with 8.3±4.8% (μ ± σ, N =13) and 9.2 ± 4.5% of the tips, respectively, in the top and bottom tenth of each neuronal spread. Only one cell (marked with a # sign in Figure 5A) had more than one in five terminal tips (21%) within the extreme 10% of its depth. The farthest terminal point of this interneuron (i.e., the tip with greatest path distance from the soma) was inspected visually and found to be > 20 μm away from the physical edge of the slice (before shrinkage correction). If trees were relatively elongated in the Z direction, their termination with greatest depth would also tend to have the greatest path distance. In contrast, only two other cells (marked with asterisks) had their farthest terminal points within 10 μm of an edge, and their overall tip distribution did not deviate from linearity at the extremes.

Figure 5.

Analysis of axonal terminal tips. (A) The position of every axonal termination in each of the reconstructed cells after shrinkage correction was rank ordered in the depth of the slice from lowest (left) to highest (right). The locations of the soma and of the farthest point along the path are marked in each case. Significant truncation artifacts due to slice sectioning would result in a disproportioned number of terminals lying along one of the edges. No cells clearly exhibit this trend. Two interneurons (*) had their farthest point near the edge of the cell, and one (#) had more than 20% of its terminals in the extreme tenth of the slice, indicating the potential for truncation. None of these cells exhibited morphometric outliers compared to the other cells. (B) Histogram of the frequency of tips at several depths, with left and right ordinates representing absolute numbers and relative proportions of the total count.

Throughout the rest of the analyses, the relevant morphological properties of these three cells were compared to the remaining 10 interneurons, and no significant deviations were found in any of the measures. Moreover, the maximum neuritic spread in the depth of the section was on average considerably smaller than the slice thickness (192 vs. 350 μm, <55%). Only one cell (the central position in Figure 5) spanned most of the section depth, and this morphology also did not deviate from the rest of the distribution in any of the quantitative measures. Overall, these observations suggest that the vast majority of the terminal tip positions demarcate real terminations, and that artifact truncations, if present, are unlikely to substantially alter the conclusions of the morphometric analysis.

R and L-M interneurons cannot be differentiated based on quantitative morphological measures of their dendrites and axons

Tables 4 and 5 compare the summary morphological properties of the dendritic and axonal arbors, respectively, between R and L-M cell groups. The first set of metrics in each table is related to the overall arborization size and geometry: number of bifurcations, maximum branch order, total length, surface area, and volume, maximum path and Euclidean distance from soma to tips, global fractal dimension, and isotropy. In contrast, the second set of metrics characterizes the average local properties of dendritic branches: branch path length, taper rate, diameter drop at bifurcations, partition asymmetry, contraction, branch fractal dimension, and bifurcation angles (see Materials and Methods for definitions). Neither dendrites nor axons differ in any of these morphological properties between cell groups. Several other summary morphometrics were extracted and statistically tested with L-Measure (Scorcioni et al., 2008), but no significant differences were found between R and L-M interneurons.

Table 4. Dendritic morphometry of R and L-M interneurons.

| Dendrites | R μ ± σ (N=7) | LM μ ± σ (N=6) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of bifurcations | 30.29±25.69 | 24.50±19.56 | 0.73 |

| Maximum branch order | 7.29±3.45 | 8.67±4.97 | 0.63 |

| Total length (μm) | 2909.74±1387.31 | 3217.44±2899.56 | 0.84 |

| Surface area (μm2) | 7691.60±4016.77 | 10315.10±11864.16 | 0.84 |

| Volume (μm3) | 2304.56±1452.51 | 3211.60±4342.99 | 0.84 |

| Max path distance from soma to tips (μm) | 553.36±171.27 | 591.89±294.71 | 1.00 |

| Max Euclidean distance (μm) | 392.33±88.71 | 373.14±191.75 | 0.95 |

| Global fractal dimension (box-counting) | 1.07±0.04 | 1.14±0.13 | 0.73 |

| Isotropy | 0.27±0.07 | 0.27±0.17 | 1.00 |

| Branch path length (μm) | 54.98±16.98 | 57.10±28.91 | 0.63 |

| Taper rate | 0.20±0.16 | 0.20±0.13 | 0.84 |

| Bifurcation diameter drop | 0.77±0.08 | 0.81±0.11 | 0.53 |

| Partition asymmetry | 0.51±0.10 | 0.52±0.09 | 0.84 |

| Contraction | 0.86±0.03 | 0.86±0.04 | 0.95 |

| Branch fractal dimension (Caliper) | 0.94±0.03 | 0.94±0.02 | 0.84 |

| Amplitude bifurcation angle (°) | 70.45±8.58 | 72.67±19.89 | 0.63 |

| Tilt bifurcation angle (°) | 107.62±16.32 | 108.54±15.04 | 0.95 |

Table 5. Axonal morphometry of R and L-M interneurons.

| Axons | R μ ± σ (N=7) | LM μ ± σ (N=6) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of bifurcations | 192.14±71.73 | 288.83±82.88 | 0.06 |

| Maximum branch order | 37.86±17.45 | 37.33±11.11 | 0.95 |

| Total length (μm) | 21534.56±12041.69 | 25081.30±10937.61 | 0.63 |

| Surface area (μm2) | 33431.49±24343.35 | 38700.12±18976.73 | 0.29 |

| Volume (μm3) | 4760.39±3846.53 | 5850.29±4730.13 | 0.37 |

| Max path distance from soma to tips (μm) | 1931.85±579.70 | 1927.32±557.24 | 1.00 |

| Max Euclidean distance (μm) | 679.83±206.60 | 476.39±130.00 | 0.07 |

| Global fractal dimension (box-counting) | 1.28±0.09 | 1.34±0.17 | 0.18 |

| Branch path length (μm) | 54.83±14.80 | 46.77±5.89 | 0.37 |

| Taper rate | -0.11±0.15 | -0.02±0.06 | 0.53 |

| Bifurcation diameter drop | 0.96±0.05 | 0.96±0.08 | 0.53 |

| Partition asymmetry | 0.60±0.04 | 0.60±0.04 | 0.84 |

| Contraction | 0.82±0.03 | 0.82±0.03 | 0.84 |

| Branch fractal dimension (Caliper) | 0.93±0.02 | 0.91±0.02 | 0.23 |

| Amplitude bifurcation angle (°) | 89.61±7.53 | 91.66±8.19 | 0.29 |

| Tilt bifurcation angle (°) | 91.60±6.52 | 90.35±8.10 | 0.45 |

Comparing Tables 4 and 5, it is immediately apparent that axonal arbors are much larger than the dendritic trees with respect to all size metrics. In particular, both the number of bifurcations and the overall length are nearly an order of magnitude greater for axons than for dendrites in both R and L-M interneurons. Interestingly, both groups of neurons displayed considerable cell-to-cell variability in their overall dendritic and arbor properties, with close to unitary coefficients of variation in several measures of size. In contrast, most branch properties appeared more uniformly distributed among cells. The within-neuron variability of these local measures is further examined and discussed below.

Although this is the first characterization of R and L-M axonal morphology in CA3, several of the dendritic properties can be compared with similar available data. In particular, the digital dendritic reconstructions of 13 R and 13 L-M interneurons are archived in NeuroMorpho.Org from the previously cited study (Chitwood et al., 1999). These files were downloaded and analyzed with L-Measure by extracting the same parameters reported in Table 4. While there were some numerical differences between the metrics measured from our reconstructions and these archival data, the ratio between the average measures of R and L-M interneurons were consistently similar (e.g., bifurcation amplitude angle: 83.62 ± 7.81° and 86.88 ± 8.05° for R and L-M cells from NeuroMorpho.Org, cf. Table 4 for our reconstructions). In particular, none of the measured parameters was significantly different between the two cell groups. One statistically significant difference was detected between our data sets and those from this earlier study in the R interneurons, in spite of the large variability. Specifically, the files from NeuroMorpho.Org had half as many branches (16.92 ± 8.92), but twice the average branch length (95.45 ± 16.01 μm). Because our cells were confined within CA3b while those reconstructed by Chitwood and colleagues were not, this single discrepancy could be due to different dispositions of the neurons in the hippocampus (similar to the CA3a vs. CA3c distinction in pyramidal cell dendrites reported by Ishizuka et al., 1995).

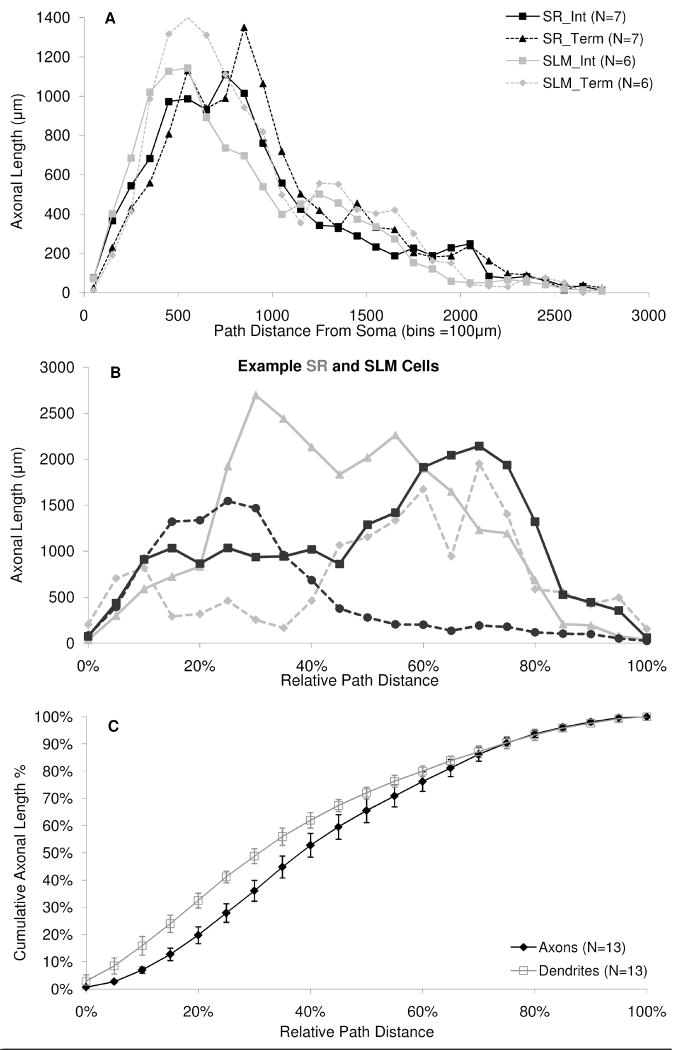

Even though the axons of R and L-M cells do not significantly differ in overall length and maximum path distance, it is interesting to compare them with respect to how the extent of their trees is distributed in relation to their cell somas (“Sholl-like” plots). Figure 6 illustrates the results of this analysis for the axonal arbors. In particular, within each individual cell, we summed the axonal length falling within successive path distance bins of 100 μm. Moreover, we measured separately the internal and terminal axonal branches (i.e., those leading to a bifurcation and to a termination, respectively), in light of their different growth regulation during development (e.g. Rossi et al., 2007). The resulting distributions were then averaged over the cell in each group (Fig. 6A). Terminal and internal axons for R and L-M cells all share similar bell-shape functions, with a relatively steep increase to a peak between 600 and 800 μm from the soma, and a shallower, steady decline until >2500 μm from the soma. The lack of difference between terminal and internal axonal portions suggests that the branches have the same probability of terminating at any path distance. The similar distributions between the two cell groups indicate that these features are fairly independent of the somatic layer location.

Figure 6.

Length distribution across path distance from soma. (A) Sholl-like plot of the amount of axonal length at subsequent 100 μm-wide path distance bins. Cell values are grouped and averaged by layer of somatic location and by internal (Int) and terminal branches (Term). (B) The axonal length distributions for two representative cells from both the L-M and R groups are plotted in subsequent 5%-wide bins, where path distance is measured as a proportion of the maximum path distance for each cell. (C) Comparison of relative axonal and dendritic length distributions by 5% path increments for all cells pooled together.

Inspection of these axonal length distributions for individual interneurons revealed considerable cell to cell diversity in both the R and L-M groups. Figure 6B illustrates these differences across neurons by comparing two representative individuals in each class and pooling together internal and terminal axonal length. Because of the considerable variability in maximum path length mentioned above (Table 5), we adopted a relative scale in the abscissa. Despite this normalization, some cells exhibit peaks in axonal length in the more proximal half of the tree (25-30%), others in the distal half (70-75%), again independent of the somatic layer.

Overall length distributions were next compared between axons and dendrites pooling together all (R and L-M) interneurons. Given the overall size difference between axonal and dendritic arbors in addition to the large variability among cells, these data were also normalized within each neuron. In the resulting cumulative plots (Figure 6C), the initially higher slope for dendrites indicates that they distribute more of their length relatively closer to the soma, whereas axons maintain a more balanced distribution across their own path distance. In particular, dendrites and axons on average pass the midpoint of their length distributions (50% of their total amount in each cell) close to one third and one half, respectively, of their maximum path (∼35% vs. ∼45%, respectively).

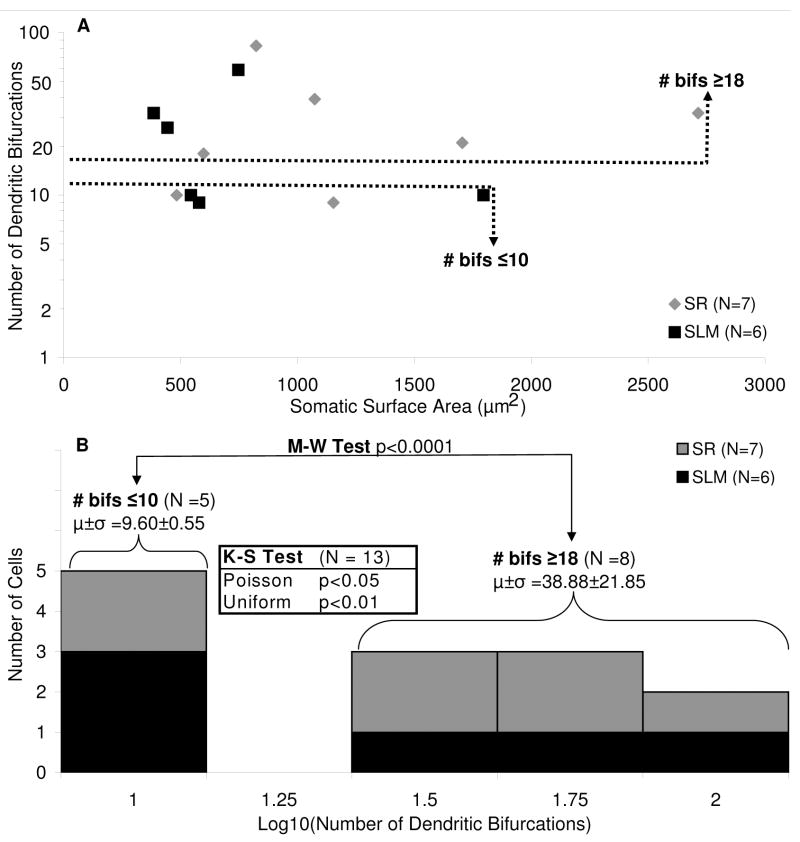

Dendritic branching alone identifies distinct subclasses of CA3b interneurons

Both overall size measures (Tables 4 and 5) and relative distributions (Figure 6) emphasize the spread of values among individual cells relative to any separation between R and L-M interneurons. For example, both groups display a particularly striking variability in the number of dendritic bifurcations (9 to 83). Considering the trend difference in somatic surface area, and the dependence previously reported between number of bifurcations and somatic surface in other morphological classes (e.g. Cullheim et al., 1987), we analyzed the relationship between these two measures (Figure 7A). Although we failed to find any significant correlation either within cell groups (R and L-M) or through all 13 cells jointly, there appeared to be two separate clusters of cells with lower and higher counts of bifurcations. In particular, 8 cells have 18 or more dendritic bifurcations, while 5 cells have 10 or fewer bifurcations, with nothing in between (Figure 7B). A Kolmogorov-Smirnov test rejected the null hypotheses of these two groups belonging to the same Poisson or uniform distributions (p < 0.05 in both cases). The distribution of R and L-M interneurons was equally balanced between the two pools, confirming that this dendritic measure is unrelated to the layer identity of the corresponding somata.

Figure 7.

Dendritic branching in CA3b interneurons. (A) Scatter plot distribution of the number of dendritic bifurcations by somatic surface area. Dashed lines separate cells with high (HiDe) and low (LoDe) numbers of dendritic bifurcations. (B) Semi-log histogram of dendritic branching characteristics. Cells cluster into two groups by number of dendritic bifurcations, with a gap in between ≤10 and ≥18 dendritic bifurcations. R and L-M cells are found in both high and low dendritic groups. Mann-Whitney (M-W) test was used to compare number of dendritic bifurcations for LoDe and HiDe cell groups. Kolmogorov-Smirnov (K-S) Poisson and uniform distribution tests were performed on all cells grouped together.

To investigate further the putative distinction of CA3b interneurons into two distinct types based on the complexity of their dendrites, several morphometric comparisons were carried out between the cells with higher and lower number of dendritic bifurcations (henceforth named HiDe and LoDe, respectively). Numerous dendritic parameters were significantly different between the two groups (Table 6). Although the measures of overall size are clearly related to the bifurcation number (e.g. maximum branch order, length, and surface area), global fractal dimension and the branch-level characteristics constitute in principle independent features, including branch path length, taper rate, angle metrics, and partition asymmetry. This distinction was quantitatively confirmed by measuring the correlation coefficients between each of these latter metrics and the number of bifurcations (none was found statistically significant). Interestingly, branch path length is longer for LoDe cells, which could be causally related to their significantly smaller taper rate. Various angle measurements were also significantly different between HiDe and LoDe cells. These angles are highly correlated to each other, and should be considered as one robust underlying measure, suggesting that HiDe cells branch at wider angles.

Table 6. Morphometric and physiological differences between HiDe and LoDe interneurons.

| Dendritic/Physiological Feature | HiDe μ ± σ (N=8) | LoDe μ ± σ (N=5) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of bifurcations | 38.88±21.85 | 9.60±0.55 | 0.0008** |

| Maximum branch order | 10.25±3.49 | 4.20±0.84 | 0.003**++ |

| Total length (μm) | 3941.98±2272.72 | 1627.39±559.01 | 0.01**++ |

| Surface area (μm2) | 11751.22±9622.59 | 4344.42±1211.69 | 0.03*++ |

| Global fractal dimension (box-counting) | 1.14±0.10 | 1.04±0.03 | 0.01** |

| Branch path length (μm) | 47.56±17.52 | 72.39±22.90 | 0.05*+ |

| Taper rate | 0.13±0.12 | 0.32±0.05 | 0.006** |

| Partition asymmetry | 0.56±0.08 | 0.45±0.07 | 0.05* |

| Amplitude bifurcation angle (°) | 78.76±10.03 | 59.82±12.53 | 0.03* |

| Tilt bifurcation angle (°) | 106.19±11.34 | 134.33±7.43 | 0.002** |

| Action potential amplitude (mV) | 76.25±5.75 | 70.2±5.85 | 0.05* |

| Afterhyperpolarization amplitude (mV) | 10.88±1.81 | 14.00±2.24 | 0.03* |

| RC 20-80% rise (ms) | 2.46±0.23 | 3.00±0.48 | 0.01** |

uncorrected significant values

significant after false discovery rate correction

uncorrected significant values for correlation with number of dendritic bifurcations

significantly correlated with number of dendritic bifurcations after false discovery rate correction

In contrast to the numerous differences in dendritic morphometrics between HiDe and LoDe groups, no differences in axonal morphology were found (data not shown). Similarly, no differences in somatic location in the horizontal axis of hippocampus were found between HiDe and LoDe neurons, supporting the notion that this morphological distinction is not affected by placement within the hippocampus. Thus, based solely on morphological differences in the dendrites, HiDe and LoDe cells may represent two distinct interneuron types in area CA3. This observation is also practically convenient because the count of dendritic branches can distinguish cells with more or less than 10 bifurcations quickly and directly from visual inspection of the microscopic field.

These finding were corroborated by the quantitative analysis of the dendritic reconstructions of CA3 R and L-M interneurons available in NeuroMorpho.Org from the previous independent study (Chitwood et al., 1999). In particular, 5 and 10 cells of these cells from NeuroMorpho.Org satisfied the criteria for the LoDe (≤10 bifurcations) and HiDe (≥18 bifurcations) definitions, respectively. Among the morphometrics found to significantly differ (but not to correlate with dendritic count) in our cells, several were matched in these independent datasets, including taper rate (HiDe: 0.21±0.03, LoDe: 0.34±0.11; p < 0.005) and partition asymmetry (HiDe: 0.49±0.07, LoDe: 0.32±0.15; p < 0.05). Another morphometric was also significantly different in the NeuroMorpho.Org data, namely the bifurcation diameter drop (HiDe: 0.82±0.03, LoDe: 0.73±0.06; p < 0.01). This parameter had strikingly similar averages in our data and followed the same trend, though without reaching statistical significance (our HiDe: 0.82±0.09, LoDe: 0.73±0.08; p ∼ 0.07). Interestingly, all of the metrics that significantly differ between HiDe and LoDe cells in either our set or NeuroMorpho.Org reached strong statistical significance when the two data sources were combined, likely due to the larger sample size (combined NHiDe = 18, NLoDe = 10). Most importantly, the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test for these pooled groups strongly supported the hypothesis of two separate distributions for HiDe and LoDe (p < 10-5 and p < 0.002 for the uniform and Poisson assumptions, respectively).

Moreover, our electrophysiological data indicates that HiDe cells have significantly faster RC synaptic kinetics, larger APAs, and smaller AHPAs than LoDe cells (Table 6). These biophysical measures are not interrelated and constitute independent features. In particular, the relationship between APA and AHPA was tested by augmenting this pool of 13 cells with data from 42 additional R and L-M interneurons (Calixto et al., 2008), and revealed no significant correlation (R = -0.06, p > 0.6). Furthermore, these different functional characteristics could not be explained by (and generally contrasted with) the differences in dendritic morphometrics based on cable theory (Burke, 2000). Thus, these observations indicate disparities in intrinsic membrane properties between HiDe and LoDe cells. In contrast, the dendritic branching count was not correlated with the polarity of the MF plasticity. In particular, cells showing LTD belonged to both the HiDe and LoDe groups and HiDe and LoDe neurons were not separated along the lines of different forms of synaptic plasticity. In other words, there is a clear dichotomy between morphometrics (HiDe vs. LoDe) and long-term plasticity (MF LTP in SLM vs. MF LTD in SR), and, within each layer, cells are dendritically divided in the same way regardless of the plasticity.

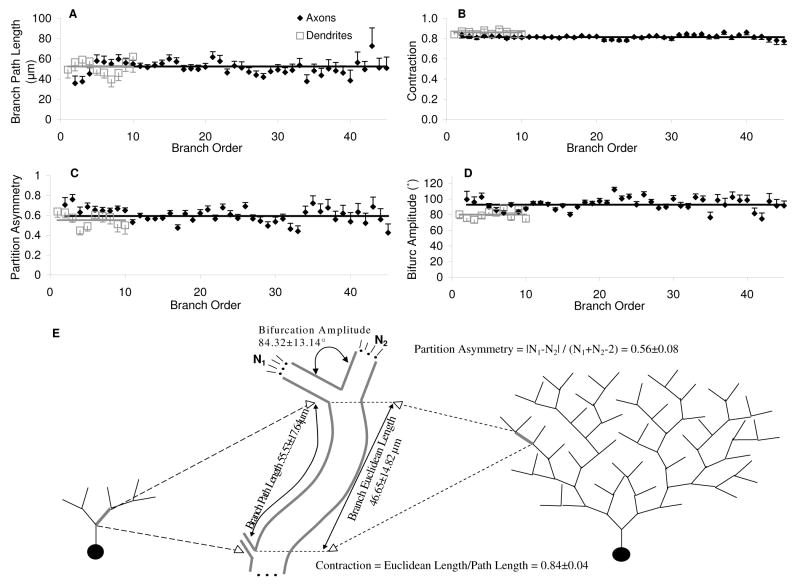

Modular branch organization of CA3b interneuron axons and dendrites

Additional analysis of the local geometry of axons and dendrites was carried out as a function of branch order (the number of bifurcations in the path to the soma). Quantifying any of these parameters separately for different groups (R vs. L-M or HiDe vs. LoDe) did not reflect any differential trend in the change of morphometric measures with respect to branch order above and beyong reproducing statistical differences for the overall values reported in Table 6. Thus, these pattern distributions are reported here for all 13 cells characterized as a single pool (Fig. 8). The results indicated a surprising uniformity of all tested morphometrics across branch order. In particular, the average branch path length was fairly constant at ∼55 μm throughout the trees (Fig. 8A). Similarly, partition asymmetry and contraction did not deviate from their respective grand averages at any of the branch orders (Fig. 8B and C, respectively). Although axons extend over a clearly more profuse arborization than dendrites (spanning ∼45 vs. ∼10 branch orders, respectively), the uniformity at the level of individual branches was generally preserved between the two arbor types. The only minor exception was a slightly greater bifurcation angle for axons than for dendrites (90 vs. 80), again consistent over the entire respective ranges of branch order (Figure 8D).

Figure 8.

Dendritic and axonal morphological distributions. (A) Branch path length, (B) contraction, (C) partition asymmetry, and (D) bifurcation amplitude angle are averaged for all cells and plotted across branch order (bars are standard errors). (E) Schematic diagram of the morphometrics reported in A-D. To the left and right are simplified illustrations of a dendritic and an axonal tree, respectively, where the similarity of the branches across branch order represents the actual similarities found for both axonal and dendritic branches. In the middle is a zoomed-in representation of an individual branch (thick gray).

This branch level similarity across branch order was also visually apparent in both the axons and dendrites of most cells. In particular, much of the morphological features of CA3b interneurons could be described with a “modular” branch composition (Figure 8E). In other words, the data is compatible with one and the same distribution of branches that is sampled independent of locations in the somatic layer (R or L-M), in the cell (axon or dendrite), or in the individual trees (low and high branching orders). The statistically significant morphological differences between groups can be accounted for by the different number of branches assembled in distinct cell classes (HiDe vs. LoDe) or arbor types (axons vs. dendrites).

Interestingly, the axons of GABAergic cells in the somatosensory neocortex display significantly more spatial meandering than either the dendrites of the same interneurons or the axons of pyramidal neurons (Stepanyants et al., 2004). This observation was taken as evidence that interneuron axons could deviate locally to reach their targets, suggesting a specific layout opposite to the random connectivity of principal cells. The paths of our CA3b interneurons (“contraction” in Tables 4-5 and Figure 7) are statistically more tortuous in axons than in dendrites (0.81±0.15 vs. 0.86±0.13 over 5845 axonal and 754 dendritic branches, respectively, p<0.0001). However, the CA3 pyramidal cell axons (Wittner et al., 2007) available in NeuroMorpho.Org show even more extreme tortuosity (0.68±0.14 over 808 branches, p<10-5 compared to our interneurons). This finding potentially highlights a functional distinction between cell class features in different cortical regions (hippocampal CA3b vs. somatosensory neocortex).

The axonal and dendritic patterns across R and L-M layers are local and lamellar

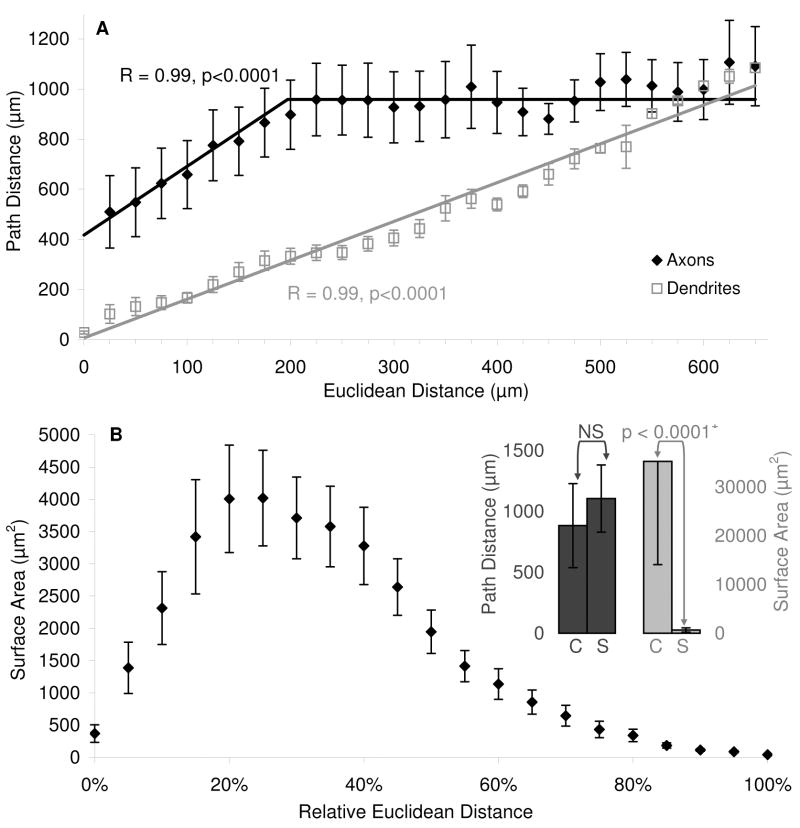

The investigation of axonal and dendritic spatial patterns in CA3b interneurons was expanded by analyzing the relation between the extent of the arbors and Euclidean distances from the soma (Fig. 9). Dendritic path increases linearly with Euclidean distance, suggesting a similar direction of growth for dendrites located closer and farther from the cell body location. In stark contrast, axonal path distance increases linearly only up until a definite Euclidean distance (∼200 μm), and then remains constant (at a value close to ∼1 mm) as Euclidean distance increases (Figure 8A). Thus, axonal locations at considerably different Euclidean distances from the soma (e.g. ∼250 μm vs. >500 μm) are on average separated from the cell body by the same path length. This surprising finding can have important functional consequences, because path distance may relate to spike propagation delay (Soleng et al., 2003) and failure probability (Kopysova and Debanne, 1998), while Euclidean distance determines the radius of presynaptic influence on the surrounding network (Stepanyants and Chklovskii, 2005). The observed relation can be explained by assuming that the axons of these interneurons tend to grow radially only in the neighborhood of the soma, but not farther away. This hypothesis was consistent with the observation that the main axonal path meandered extensively in all cells, but systematically returned to terminate in the proximity of the cell body. The peculiar split-slope characteristic was robustly evident in all cell groups (R, L-M, HiDe, and LoDe), and was also apparent in 10 of the 13 cells analyzed individually.

Figure 9.

Morphological properties across Euclidean distance from the soma. (A) Axonal (black) and dendritic (gray) path distance averaged for all cells and plotted against absolute Euclidean distance (25 μm bins). (B) Axonal surface area averaged for all cells and plotted in subsequent 5%-wide bins, where distance is measured as a proportion of the maximum Euclidean distance for each cell. (B: Inset) Path distance and surface area are averaged for all 13 cells in the “core” (“C”) and “shell” (“S”), respectively defined as the inner and outer halves of the smallest spherical volume enclosing the entire axonal tree. Bars represent standard errors in A and B, and standard deviations in the Inset.

To investigate the impact of this feature, it is useful to evaluate the proportion of axonal extent “near” or “far from” the cell body. In particular, it appears that the axons of these neurons, while extending some of their branches to a certain distance, tend to maintain most of their arbor more proximally. To determine if this is the case, we measured the axonal surface area, which reflects the ability to establish synaptic contacts (Shepherd and Harris, 1998), as a function of relative Euclidean distance from the soma, thus normalizing all cells by their maximum spread (Fig. 9B). This distribution peaked at less than 30% distance, indicating that most of the spatial density is contained within the most proximal third of the axonal outreach. Therefore, if the spherical volume containing each cells is divided into an inner (core) and outer (shell) halves, the average path distance from the soma is similar between the two regions, but the surface area found within the shell is nearly two orders of magnitude smaller compared to that in the core (Fig. 9B Inset). Together, these results suggest that the bulk of the axonal tree is found near the soma, yet the (relatively smaller) extent located in the outer circles do not differ in terms of path distance. Along with the more contained extent of dendrites compared to axons, the emerging spatial distribution of CA3b interneuron arbors is consistent with a prevalently local input and output connectivity for both R and L-M cells.

The overall space invaded by the arbor spread was quantified by multiplying the three dimensions of the smallest box containing 95% of each individual neuron after principal component analysis (see Materials and Methods). Axons invaded on average three times as much space as dendrites (0.0457±0.0339 mm3 vs. 0.0149±0.0154, N=13, p<0.001), but once again there were no differences in either axonal or dendritic spatial invasion between R and L-M interneurons (p>0.3). In order to further characterize the three-dimensional spatial occupancy around the soma relative to the main orientation of the hippocampus, axonal and dendritic volumes were measured according to different partitions (Tables 7 and 8). In particular, three orthogonal divisions were considered along the planes passing through each cell body and separating the hemispheric halves which corresponded to the directions between CA3a and CA3c, between the hippocampal fissure and the alveus, and between the septal and temporal poles (Table 7). The internal volume occupied by each cell was compared in every case between opposite hemispaces. Since the same results were found for R and L-M cells, and for HiDe and LoDe cells, the analysis is reported here for all 13 interneurons pooled together. Axons occupied significantly greater volume toward the hippocampal fissure than toward the alveus. No other significant differences between hemispheres were found for either dendritic or axonal arbors.

Table 7. Planar analysis of axonal and dendritic occupied volumes.

| PLANAR HEMISPHERE | Axonal volume, μ±σ | Dendritic volume, μ±σ |

|---|---|---|

| CA3c | 3450.26±3091.59 | 1572.00±2357.67 |

| CA3a | 1911.05±1450.82 | 950.30±922.02 |

| Manney-Whitney p | 0.35 | 1.00 |

| Fissure | 4023.15±3609.59 | 1018.82±677.78 |

| Alveus | 1337.70±855.55 | 1502.28±2963.89 |

| Manney-Whitney p | 0.02* | 0.29 |

| Septal | 2208.81±1963.76 | 966.58±1338.63 |

| Temporal | 3151.50±3527.88 | 1558.73±1922.82 |

| Manney-Whitney p | 0.63 | 0.22 |

Table 8. Sector analysis of axonal and dendritic relative volumetric distributions.

| Octant | Relative axonal volume, mean±S.E.M. | Relative dendritic volume, mean±S.E.M. |

|---|---|---|

| CA3c/Alveus/Septal | 0.19±0.06 | 0.14±0.04 |

| CA3c/Alveus/Temporal | 0.25±0.06 | 0.21±0.06 |

| CA3c/Fissure /Septal | 0.09±0.05 | 0.07±0.03 |

| CA3c/ Fissure /Temporal | 0.12±0.04 | 0.15±0.03 |

| CA3a/Alveus/Septal | 0.11±0.03 | 0.09±0.02 |

| CA3a/Alveus/Temporal | 0.16±0.05 | 0.14±0.05 |

| CA3a/Fissure/Septal | 0.04±0.01 | 0.08±0.03 |

| CA3a/ Fissure /Temporal | 0.05±0.02 | 0.13±0.04 |

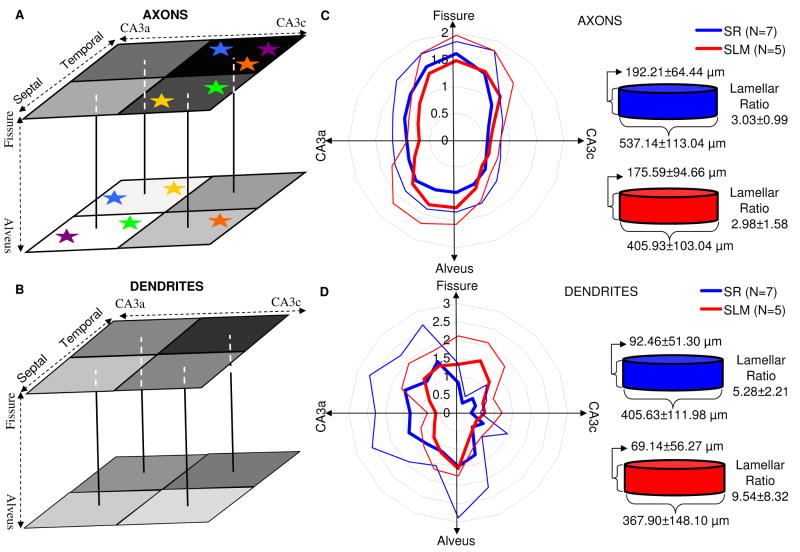

| Kruskall-Wallis p | 0.04* | 0.23 |

The region surrounding every soma was then separated into eight sectors based on each of the three binary partitions (Table 8). The axonal and dendritic volumes in each octant were divided by their respective measures summed over the whole space, such that a perfectly even regional distribution would result in values of 0.125 for every sector. A Kruskall-Wallis test detected a statistically significant deviation from this uniform spread for axons, but not from dendrites. Cross-sector pairwise comparisons were thus performed and five groups significantly differed in terms of axonal volume, as graphically illustrated in Figure 10A. The grayscale of each sector in this map represents the volumetric proportion (darker shades correspond to higher values). Each couple of stars of corresponding colors represents a significant pairwise difference. Consistent with the planar analysis, all five of these pairs contained one sector closer to the fissure (higher volume) and one sector closer to the alveus (lower volume). Even though the planar analysis revealed no statistical differences between CA3a and CA3c (Table 7), four significantly different sector pairs contained one CA3c and one CA3a octant (with higher and lower volume, respectively). The lower grayscale contrast in the corresponding dendritic volume sector map (Figure 10B) suggests a more homogeneously balanced distribution, visually confirming the quantitative statistics (Table 8).

Figure 10.

Anatomical orientation of axonal/dendritic trees. (A) Axonal and (B) dendritic maps show the volumetric proportion for eight sectors, each corresponding to a square on a cube face. The soma of each cell would be located in the middle of the cube. The darkness of every square is proportional to the volumetric proportion of the given sector. Matching color stars indicate significantly different volumetric proportions. (C-D, left) Axonal and dendritic polar histograms of average length distribution relative to the soma for R (blue) and L-M (red) cell groups (bin size: π/8 rad). Values are normalized by dividing the length in each bin by the mean length over all bins. (C-D, right) Both axons and dendrites exhibit lamellar spread, where the arborization is more confined in the longitudinal direction compared to the transverse plane. The lamellar ratio between the longitudinal and transverse spreads of tracing points is averaged over all cells.

According to the lamellar hypothesis (Amaral and Witter, 1989; Andersen et al., 2000), local circuitry of the rodent hippocampus is mainly organized perpendicular to the septo-temporal axis. The low isotropy displayed by the dendrites of our R and L-M cells (Table 4) suggests that this principle may also apply to CA3b interneurons. To determine the exact relationship between the observed anisotropy and the lamellar architecture, the planar and octant analyses were complemented by a detailed investigation of axonal and dendritic length distributions in the transverse and longitudinal directions. The transverse plane, defined by the CA3a-CA3c and alveus-fissure directions, was represented in polar coordinates relative to the somatic position. The radial distance from the center was set equal to the neuronal length normalized by the average value over all directions. Thus, a value of two at a given orientation means that cells exhibit on average twice as much extent in that direction than would be expected from a uniform spatial distribution. The axons of both R and L-M interneurons are elongated along the alveus-fissure direction, and tend to grow towards the fissure (Figure 9C, left). Dendrites do not appear to grow systematically in any particular direction (Figure 9D, left), consistent with the plane and sector analyses (Tables 7 and 8). Moreover, R and L-M cells had similar distributions (Fig. 10C,D), as did the HiDe and LoDe groups (data not shown).

Next, the arbor spread in the septo-temporal direction was measured and compared to the transverse spread. Axons extended transversally on average three times as much as longitudinally, again with very similar measurements for R and L-M interneurons (Figure 10C, right). The situation was even more extreme in dendrites, which exhibited far less longitudinal spread than transverse spread (Figure 10D, right). The lamellar ratio for dendrites was greatest in L-M cells, displaying an almost 10-fold larger transversal than longitudinal extent on average, but varied considerably from neuron to neuron, such that the resulting mean differences were statistically similar for all cell groups. This analysis shows that both axons and dendrites of CA3 interneurons are characterized by a lamellar distribution. Furthermore, within the transverse plane, axons extend more between the alveus and the hippocampal fissure than between areas CA3a and CA3c, while dendrites show no preferential orientation. These spatial distributions are robust with respect to the layer location of the cell body (R vs. L-M) and the complexity of dendritic branching (HiDe vs. LoDe).

It is important to remark that, because the “functional” orientation of the transverse section is perpendicular to the longitudinal curvature of the hippocampus, it varies with respect to the plane of the actual slice preparation. Although our experiments were always carefully controlled for the regional consistency of the recording site, the variation among preparations can be assumed to be small yet not necessarily negligible. Thus, the interpretation of the above spatial analysis in the slice plane (Table 8 and Fig. 10) should be limited to a relative comparison between axonal and dendritic arbors.

Discussion

GABAergic interneurons stir considerable scientific interest due to their dynamic role in the control of information processing within mammalian neural circuits (Mann and Paulsen, 2007). Numerous studies have defined the morphological and phenotypic heterogeneity of interneurons in the neocortex and hippocampus (Yuste, 2005; Houser, 2007). However, a clear understanding of the computational role of populations of interneurons within well characterized polysynaptic circuits has been difficult to obtain due to the scarcity of detailed quantitative morphometric analysis, especially of axonal arbors, in electrophysiologically identified neurons. In this study we quantitatively assessed the branching and spatial patterns of dendrites and axons of R and L-M interneurons in hippocampal area CA3. Both types of interneurons belong to a larger population of GABAergic cells that act as subthreshold coincidence detectors for converging MF and PP inputs (Calixto et al., 2008). However, the long-term plastic properties of excitatory synapses in R interneurons differ from the ones observed in L-M interneurons. For example, most of the R interneurons described here underwent MF LTD (Figure 2) whereas the majority of L-M interneurons showed Hebbian bidirectional plasticity at their MF synapses (Galvan et al., 2008). In the context of this “layer dependent plasticity”, it is interesting to note that in stratum lucidum interneurons, MF synapses exhibit LTD/LTP which is induced presynaptically (Pelkey et al., 2008). We hypothesized that the R/L-M layer specific plasticity may be correlated with distinct morphometrics and electrophysiological features which could extend the subclassification of these two types of interneurons to the anatomical and functional level. However, our data demonstrate that R and L-M interneurons were indistinguishable in the branching and spatial patterns of dendrites and axons, and had comparable electrophysiological properties. Nevertheless and consistent with the notion that interneurons of different types have the same somatic position (Klausberger and Somogyi, 2008), we found two separate subclasses of cells with lower and higher counts of dendritic bifurcations unrelated to the layer localization of the soma.

An earlier study of CA3 R and L-M interneurons focused on electrophysiological properties (Chitwood and Jaffe, 1998). Like our cells, both types of interneurons were found to have adapting (accommodating) firing rates. The passive membrane properties and synaptic kinetics are not directly comparable between that earlier report and our data due to the different recording temperatures. However, all the relative findings comparing R and L-M interneurons are coherent between the two studies, and generally point to a broad cell-to-cell variability and overall similarity between the R and L-M groups. Although the axonal arbors had not been traced in this previous report, the dendritic reconstructions available through NeuroMorpho.Org enabled a limited comparison with our morphologies. The results were again consistent, with only minor differences that are not surprising given our more stringent control on the anatomical location of somata (CA3b vs. CA3).

The morphology of CA3 R interneurons was also analyzed in the developing rat hippocampus (Gaiarsa et al., 2001). Despite immature features (somatic and dendritic filopodial processes) in the first postnatal week, both the dendritic and axonal patterns in that report closely resemble our data. However, these tracings were not digitally reconstructed, limiting the comparison to a two-dimensional, qualitative assessment. Empirical evidence and theoretical analysis concur that quantitatively characterizing axonal morphology is crucial to determine circuit connectivity (Somogyi and Klausberger, 2005; Stepanyants and Chklovskii, 2005). The computational role of each cortical interneuron type is linked to its ability to affect activity and plasticity through cell-class specific and possibly sub-cellularly specialized synaptic connections (Wittner et al., 2006). The function of R and L-M interneurons in area CA3 thus depends on the interaction of their intrinsic biophysical and morphological features with the structural and dynamical network properties of this particular hippocampal region. To date, the majority of the efforts to characterize hippocampal interneurons, and specifically the axonal morphology of R and L-M cells, have been limited to area CA1.

An influential morphological study of L-M interneurons in CA1 was performed by intracellular Lucifer Yellow injection with sharp electrodes (Lacaille and Schwartzkroin, 1988). A relatively homogenous group of 16 clearly non-pyramidal neurons were recovered near the stratum radiatum border. Most of these cells had fusiform multipolar somata (∼20 μm in diameter, their Fig. 3), and extended mainly smooth, beaded dendrites through two-thirds of CA1. Axons, reconstructed in five neurons, started from a primary dendrite in stratum lacunosum-moleculare, and projected through stratum radiatum, along stratum pyramidale, and occasionally into stratum oriens. In two interneurons, axon collaterals were not restricted to CA1, but crossed the hippocampal fissure into the molecular layer of the dentate gyrus. While recognizing the still undetermined role of L-M interneurons in hippocampal circuitry, this study suggested a feedforward inhibitory function based on their strong excitation by major extrinsic afferents, and the presence in this layer of immunoreactivity for GABA (Gamrani et al., 1986) and its synthesizing enzyme (Somogyi et al., 1984; Kunkel et al., 1986). Similar morphological data were reported based on whole-cell biocytin injections (Williams et al., 1994), with axons branching in strata lacunosum-moleculare and radiatum, and into the dentate gyrus and CA3.

Another CA1 study (Vida et al., 1998) described the morphology of Schaffer-associated cells as similar to that described above and in previous L-M reports (Kawaguchi and Hama, 1988), identifying heavy dendritic branching in stratum lacunosum-moleculare (like L-M cells). Moreover, relatively little axon of the PP-associated interneurons was contained in stratum radiatum, also consistent with a combined category of R and L-M cells. At the same time, important distinctions must be noted between CA1 and CA3. The absence of physiologically induced synaptic connections from CA1 pyramidal cells to L-M interneurons (Lacaille and Schwartzkroin, 1988) is consistent with the anatomy of this region. Pyramidal cell axons in CA1 primarily ascend in stratum oriens and project in the alveus (Ramon y Cajal, 1911; Lorente de No, 1934). The dendrites of feedforward interneurons are largely confined to strata radiatum and lacunosum-moleculare (Lamsa et al., 2005), which are mostly devoid of local pyramidal cell axon collaterals (Finch and Babb, 1981; Knowles and Schwartzkroin, 1981). The presumed absence of pyramidal cell input indicates that R/L-M interneurons in CA1 do not mediate feedback inhibition.