Abstract

The role of sonic hedgehog (SHH) in maintaining corpora cavernosal morphology in the adult penis has been established; however, the mechanism of how SHH itself is regulated remains unclear. Since decreased SHH protein is a cause of smooth muscle apoptosis and erectile dysfunction (ED) in the penis, and SHH treatment can suppress cavernous nerve (CN) injury-induced apoptosis, the question of how SHH signaling is regulated is significant. It is likely that neural input is involved in this process since two models of neuropathy-induced ED exhibit decreased SHH protein and increased apoptosis in the penis. We propose the hypothesis that SHH abundance in the corpora cavernosa is regulated by SHH signaling in the pelvic ganglia, neural activity, or neural transport of a trophic factor from the pelvic ganglia to the corpora. We have examined each of these potential mechanisms. SHH inhibition in the penis shows a 12-fold increase in smooth muscle apoptosis. SHH inhibition in the pelvic ganglia causes significantly increased apoptosis (1.3-fold) and decreased SHH protein (1.1-fold) in the corpora cavernosa. SHH protein is not transported by the CN. Colchicine treatment of the CN resulted in significantly increased smooth muscle apoptosis (1.2-fold) and decreased SHH protein (1.3-fold) in the penis. Lidocaine treatment of the CN caused a similar increase in apoptosis (1.6-fold) and decrease in SHH protein (1.3-fold) in the penis. These results show that neural activity and a trophic factor from the pelvic ganglia/CN are necessary to regulate SHH protein and smooth muscle abundance in the penis.

Keywords: apoptosis, cavernous nerve, erectile dysfunction, male sexual function, penis

INTRODUCTION

Erectile dysfunction (ED) is a serious medical condition with a prevalence of 18.4% in men ≥20 yr, suggesting that ED affects 18 million men in the United States [1]. The incidence of ED increases with age, coronary artery disease, peripheral vascular disease, smoking, dyslipidemia, higher BMI, diabetes mellitus, and after radical prostatectomy. Oral therapy with PDE5 inhibitors are only partially effective in certain ED populations, including men with diabetes and those treated for prostate cancer (including prostatectomy and radiation therapy) [2-4]. Approximately 50% of diabetic men [5, 6, 1] and 30%–87% of patients treated by radical prostatectomy experience ED [7-11]. There is a greater concern for quality of life in diabetic and prostatectomy populations due to improved treatment strategies and younger age of diagnosis. Survey studies of men electing treatment for localized prostate cancer reveal quality of life is a primary concern in 45% of participants [12]. Since oral therapy with PDE5 inhibitors is only partially effective in diabetic and prostatectomy populations [3, 2], novel therapeutic approaches to treat ED are needed. Significantly increased apoptosis of the corpora cavernosal smooth muscle is a common etiology in animal models of diabetes [13-17] and cavernous nerve (CN) injury/prostatectomy [18-20], and smooth muscle apoptosis is associated with the development of ED [21]. This leads to fibrotic changes in the penis and altered smooth muscle relaxation. In ED patients a loss of smooth muscle cells and an increase in fibrosis have been detected in corporal tissue [22-24], and a significant decrease in penile size was observed in men with ED after nerve-sparing prostatectomy [25]. These observations parallel the increased apoptosis observed in animal models. Understanding the mechanisms that regulate the smooth muscle morphology of the penis is critical for development of new therapeutic approaches for ED treatment and prevention.

A novel regulator of the smooth muscle morphology of the penis is the secreted protein sonic hedgehog (SHH). SHH is necessary during embryogenesis of the penis for both genital tubercle outgrowth and differentiation [26], and in mice with a targeted deletion of Shh, external genitalia were completely absent [27]. The SHH pathway functions after birth to direct differentiation of corpora cavernosal sinuses, and in the adult penis SHH functions to maintain the sinusoid morphology of the corpora cavernosa that it helped establish [21]. When SHH function is inhibited in the adult penis using the 5E1 inhibitor (disrupts binding of SHH to its receptor patched; [28]) there is a significant 12-fold increase in smooth muscle apoptosis in the corpora cavernosa [20], which affects sinusoidal morphology and which causes ED [21]. We have recently shown that localized SHH protein treatment can suppress the apoptosis that occurs when the CN is cut [20], mimicking the neural injury that occurs with prostatectomy in humans. These results identify SHH as a novel and significant target for development as a treatment to prevent the apoptosis that occurs with CN injury/prostatectomy, so it would be highly beneficial to have a better understanding of the mechanisms that regulate SHH signaling in the penis.

Little is known about SHH signal transduction in the adult penis; however, SHH signaling mechanisms have been well established in other organs during embryogenesis. The SHH signal is transduced in target cells through the interplay between patched (PTCH1) and smoothened (SMO). PTCH1 is a 12-transmembrane protein [29-32] that functions as a receptor for SHH, but does not itself transduce the intracellular signal. SMO, a 7-transmembrane protein that forms a receptor complex with PTCH1 [32], does not bind to SHH but transduces the SHH signal through activation of the GLI family of transcriptional factors. In the absence of SHH protein bound to PTCH1, PTCH1 represses downstream targets of SHH signaling by inhibiting the activity of SMO at the substoichiometrical level [33]. When SHH protein binds to its receptor PTCH1, this relieves the repression of PTCH1 on SMO and allows transcription of SHH’s downstream targets [34-39]. In the penis, SHH is present in smooth muscle and fibroblasts of the corpora cavernosa and in Schwann cells of the nerves. Although the role of SHH in maintaining the corpora cavernosal morphology in the adult penis has been established, the mechanism of how SHH itself is regulated in the penis remains unclear. Since SHH signaling plays a major role in maintaining penile smooth muscle morphology necessary for normal erectile function, the question of how SHH signaling is regulated becomes significant.

The mechanism of how SHH itself is regulated in the penis and how decreased SHH protein causes apoptosis induction remains unclear. It is likely that neural input or some factor from the CN/pelvic ganglia regulates SHH in the penis since SHH protein is significantly decreased in two models of neuropathy, the CN-injured Sprague-Dawley rat [20] and the BB/WOR diabetic rat [14]. SHH protein is localized in the neurons of the pelvic ganglia, so it is possible that SHH protein is synthesized in the pelvic ganglia and transported by the CN axon to the corpora cavernosa, where it regulates penile morphology. The role of SHH in embryogenesis of neural tissues has been well established; however, continued function of the SHH pathway in adult neurons and what role neuronal innervation plays in regulation of SHH signaling in target organs has only briefly been explored. We propose the hypothesis that neural innervation plays a role in regulation of SHH signaling in the corpora cavernosa, which in turn regulates penile morphology and erectile function. Neural regulation of SHH signaling in the corpora cavernosa may occur through several different mechanisms. These are: 1) transport of SHH from the pelvic ganglia to the corpora cavernosa via the CN, 2) transport of a trophic factor from the pelvic ganglia to the penis, which regulates SHH signaling in the corpora cavernosa, and 3) neural activity (conduction velocity) regulation of SHH signaling in the corpora cavernosa. We have examined each of these potential mechanisms independently. Our results show that neural activity and a trophic factor from the pelvic ganglia/CN are necessary to regulate SHH signaling in the penis and the smooth muscle morphology of the corpora cavernosa. The presence of SHH in neurons of the pelvic ganglia and in Schwann-like cells of the CN may be required for maintenance of neural integrity, which maintains corpora cavernosal morphology. Further study is required to determine the mechanism of SHH impact on the CN and pelvic ganglia. The concept of neuronal regulation of tissue growth and activity has been suggested by previous observations in the bladder, in which neural input influenced tissue levels of nerve growth factor [40]. However, to our knowledge, this is the first report that examines the mechanism of how this interaction may occur in the penis, and these studies suggest that neural input is integral to the regulatory mechanism.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

Sprague-Dawley rats Postnatal Day P115–120 (P115) were obtained from Charles River Laboratories. Animals were cared for in accordance with the National Research Council publication Guide for Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

5E1 SHH Inhibitor Treatment of the Corpora Cavernosa

Affi-Gel beads (100–200 mesh; Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA) were equilibrated with 5E1 SHH inhibitor (378 μg/ml, n = 2 at each time postinjection; Jessel, Hybridoma Bank at the University of Iowa) or PBS (control, n = 2 at each time postinjection) overnight at 4°C. Approximately 30-40 beads were injected directly into the corpora cavernosa of P120 Sprague-Dawley rat penes. Rats were killed at 1, 2, and 5 days following bead injection/SHH inhibition. Penes were excised and either fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for dual TUNEL staining/α-actin immunohistochemical analysis (IHC) or fixed in 2.5% glutaraldehyde for electron microscopy. Pelvic ganglia/CNs were isolated and frozen in OCT. Frozen sections of pelvic ganglia (16 μm) were treated with the Alexa Fluor 594 chicken anti-mouse secondary antibody (1/100; Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) in order to determine if the 5E1 SHH inhibitor underwent retrograde transport from the corpora cavernosa to the CN/pelvic ganglia.

5E1 SHH Inhibitor Treatment of the Pelvic Ganglia

Affi-Gel beads were equilibrated with 5E1 SHH inhibitor (378 μg/ml, n = 10) or PBS (control, n = 6) overnight at 4°C. Approximately 10–20 beads were injected directly under the pelvic ganglia bilaterally in adult Sprague-Dawley rats. Injection was not made into the ganglia itself since this would likely destroy the ganglia. Intracavernosal pressure measurements (ICPs) were performed on rats that were treated with PBS (control, n = 3) and 5E1 SHH inhibitor (n = 3) prior to killing the rats. Rats were killed at 1 and 2 days following bead injection/SHH inhibition, and the penis tissue was either snap frozen in liquid nitrogen, fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde and paraffin-embedded prior to TUNEL analysis, or fixed in 2.5% glutaraldehyde for electron microscopy. Frozen penis sections (16 μm) were treated with 1/100 goat polyclonal SHH (N-19, SC-1194, Santa Cruz) and the Alexa Fluor 594 chicken anti-mouse secondary antibody (1/100) in order to quantify SHH protein and to determine if the 5E1 SHH inhibitor was transported down the axon to the corpora cavernosa. Penis sections were also treated with nitric oxide synthase (NOS) 1 (1/50; BD Transduction Laboratories) and 1/300 chicken anti-mouse secondary to determine if SHH inhibition in the pelvic ganglia affects NOS1 abundance.

Adult Sprague-Dawley rats were treated with 10 μM cyclopamine (n = 3) or dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO; used as a control, n = 3) with a single injection directly under the pelvic ganglia in order to confirm the apoptosis observed with the 5E1 SHH inhibitor. Rats were killed after 7 days, and the penis tissue was fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde and embedded in paraffin prior to TUNEL analysis for apoptosis.

CN Tie Experiments

A midline abdominal incision was made with a scalpel under direct vision through a KAPS Industrial microscope in adult (P115–120) Sprague-Dawley rats. The pelvic ganglia and CN were exposed, and a hole was made in the membrane covering the CN on either side of the nerve approximately 5–7 mm from the pelvic ganglia. Surgical silk (9-0) was used to tie off the CN (double knot). Rats were killed 3 (n = 12) and 5 (n = 3) days after the tie was placed, and the pelvic ganglia and CN were excised and frozen in OCT. The contralateral pelvic ganglia/CNs, which did not have a tie, were used as controls. IHC for SHH protein (both colorimetric and fluorescent; 1/100 goal polyclonal SHH) and for NOS1 (1/100) was performed on sectioned CNs (16-μm sections). Alexa Fluor secondary antibodies were used at 1/100 concentration (Alexa Fluor 488 rabbit anti-goat [Molecular Probes] and chicken anti-mouse, respectively). Potential build up of SHH protein and NOS1 on either side of the ties was analyzed using a fluorescent/light microscope (Leitz) and a Nikon digital camera.

Lidocaine Treatment of the CN

Two percent lidocaine HCl (Hospira, Inc., Lake Forest, IL) and PBS (control) were soaked in Gel-Foam (Ferrsan, Soeborg, Denmark). A midline abdominal incision was made with a scalpel under direct vision through a KAPS Industrial microscope. The lidocaine-treated (n = 3) and control PBS-treated (n = 2) Gel-Foam was placed bilaterally on top of the CN of adult Sprague-Dawley rats (P115–120). After one day of lidocaine or PBS treatment the intracavernosal pressure was measured, and penes were harvested from killed males by sharp dissection and either frozen in liquid nitrogen for quantitative IHC for SHH protein or fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for quantitative TUNEL assay.

Colchicine Treatment of the CN

Colchicine (5 mM; Sigma, St. Louis, MO) and PBS (control) were soaked in Gel-Foam. A midline abdominal incision was made with a scalpel under direct vision through a KAPS Industrial microscope. The 5 mM colchicine (n = 3) or control PBS (n = 3)-treated Gel-Foam were placed bilaterally on top of the CN of adult Sprague-Dawley rats (P115–120). After two days of colchicine or PBS treatment, the intracavernosal pressure was measured, and penes were harvested from killed males by sharp dissection and either frozen in liquid nitrogen for quantitative IHC for SHH protein or fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for quantitative TUNEL assay.

TUNEL Assay for Apoptosis

TUNEL assay was performed using the Apoptag kit (Chemicon International) on isolated penis tissue fixed overnight at 4°C in 4% paraformaldehyde, embedded in paraffin, and sectioned 16 μm in thickness [20]. All cells were stained for comparison using propidium iodide (0.02 μg/ml). Fluorescent apoptotic cells were observed under a fluorescent microscope (Leitz) and photographed using a Nikon digital camera. Quantification of apoptosis was performed by counting the total number of cells and the number of apoptotic cells in a given field selected at random by visual observation. The number of apoptotic cells/all cells in five fields from each section and five sections for each penis were counted. Statistics were performed using the Microsoft Excel program, and the ratio of apoptotic cells/all cells was reported ± SEM. A t-test was performed to determine significant differences in apoptosis.

Intracavernosal Pressure Measurement

The ICP was measured as previously described [41, 14]. Nerves were stimulated (intensity of 6 V) by placing them on bipolar platinum stimulating electrodes connected to an electrical stimulator (Grass Instruments, Quincy, MA) delivering a series of square wave pulses (1 msec duration at 30 Hz). The CN was unilaterally stimulated at a distance of 3 and 5 mm from the major pelvic ganglion. Stimulation lasted 40 sec. A resting interval of at least 5 min separated two consecutive stimulation procedures. The ICP was measured by inserting a 23-gauge needle into the corpora cavernosa. A catheter was inserted into the carotid artery for measurement of arterial pressure. These instruments were connected to a pressure transducer. The data are reported either as maximal ICP or as the peak ICP to average blood pressure ratio.

Immunohistochemical Analysis

IHC was performed as previously outlined [14, 20, 21] on penis tissue assaying for goat polyclonal SHH (1/100), ACTA1 (mouse, 1/100; Sigma), and P4HB (mouse, 1/100; Acris). Secondary antibodies used were Alexa Fluor chicken anti-mouse 594 (1/300) and Alexa Fluor 488 rabbit anti-goat (1/300). Pelvic ganglia/CNs were assayed for SHH (1/100), NOS1 (1/100), and S100 (rabbit polyclonal, Abcam). Secondary antibodies used were either Alexa Fluor 488 rabbit anti-goat (1/300), Alexa Fluor donkey anti-goat (1/300, Molecular Probes), Alexa Fluor chicken anti-mouse 594 (1/300), or Alexa Fluor 594 chicken anti-rabbit (1/300, Molecular Probes).

Semiquantitative IHC

IHC was performed as previously outlined [14, 20, 21] on penis tissue assaying for goat polyclonal SHH (1/100) and NOS1. Secondary antibodies used were Alexa Fluor 488 rabbit anti-goat (1/300) and Alexa Fluor 594 chicken anti-mouse (1/300). Negative controls were performed with secondary only (without primary) to test for nonspecific staining and autofluorescence. Sections were mounted using Pro-Tex Mounting Medium (Baxter Diagnostics, Inc., Pittsburgh, PA). Microscopy was performed using a dual light and fluorescent microscope (Leitz) and photographed using a Nikon digital camera. SHH protein and NOS1 were quantified using the Image J program [42]. Total fluorescence was measured in five fields from each section and five sections for each penis. Statistics were performed using the Microsoft Excel program, and the results were reported ± SEM. A t-test was performed to determine significant differences in SHH.

Electron Microscopy

Electron microscopy was performed as described previously [43]. PBS-treated control penis tissue (n = 2 at each time point), penis tissue from 5E1 SHH-inhibited corpora cavernosa at 1, 2, and 5 days of treatment (n = 2 at each time point), and penis tissue from rats treated with 5E1 SHH inhibitor in the pelvic ganglia for 1 and 2 days (n = 2 at each time point) were fixed in 2.5% glutaraldehyde, postfixed in 1% OsO4, dehydrated, and embedded in Epon resin. These sections were cut and stained with 2% uranyl acetate and 3% lead citrate. Electron microscopy was performed using a JEOL 100CX Transmission Electron Microscope to identify in which cell type apoptosis was taking place. Apoptosis was identified by the presence of condensed chromatin, nuclear fragmentation, and cytoplasmic blebbing, which are common in cells undergoing apoptosis [44].

RESULTS

Apoptosis Induction after SHH Inhibition in the Corpora Cavernosa at 1, 2, and 5 Days of Inhibition

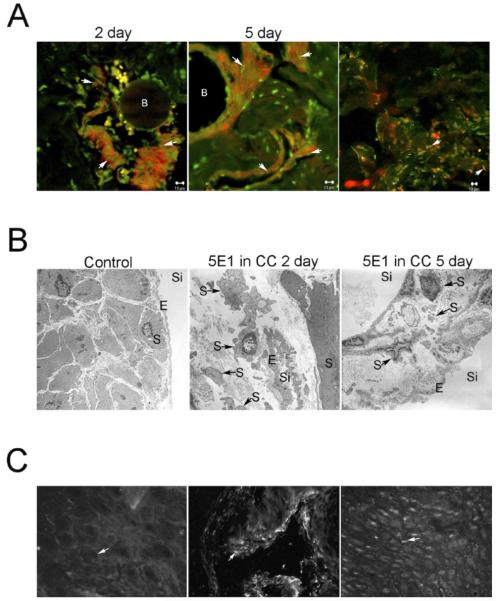

TUNEL assay was performed on corpora cavernosa tissue isolated from adult Sprague-Dawley rats that were treated with either 5E1 SHH inhibitor or PBS (control) in the corpora cavernosa for 1, 2, and 5 days via Affi-Gel beads. SHH inhibition in the corpora cavernosa caused apoptosis induction in the corpora cavernosa at 1, 2, and 5 days of inhibitor treatment (Fig. 1; [20]). Apoptosis was most abundant between 2 and 5 days of SHH inhibition. The primary cell type undergoing apoptosis was smooth muscle, as was apparent by colocalization of TUNEL staining and ACTA1 (Fig. 1). Electron microscopy confirmed that apoptosis was primarily taking place in the smooth muscle of the corpora cavernosa sinusoidal tissue (Fig. 1). TUNEL staining between sinuses colocalized with P4HB, a fibroblast marker (Fig. 1). Apoptosis appeared most abundant at 2 days, and by 5 days the smooth muscle layer around individual sinuses was narrowed (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

A) TUNEL analysis and ACTA1 IHC on sections of 5E1 SHH inhibitor-treated corpora cavernosa. Affi-Gel beads soaked in SHH inhibitor were injected directly into the corpora cavernosa of adult Sprague-Dawley rats that were killed at 2 and 5 days of SHH inhibition. Apoptosis colocalized with ACTA1, indicating that apoptosis was taking place primarily in the smooth muscle at 2 and 5 days of SHH inhibition (left and middle). A subset of TUNEL-positive cells located between the sinuses, colocalized with P4HB, a fibroblast marker (right). Arrows indicate colocalization of apoptosis/ACTA1 and apoptosis/P4HB staining. B, Affi-Gel bead vehicle. Original magnification ×1000. B) Electron microscopic analyses of penis tissue from control and 5E1 SHH inhibitor-treated corpora cavernosa. Intact endothelium and smooth muscle are apparent in control penis (left; ×30 000). Abundant apoptosis was identified in smooth muscle cells at 2 days of SHH inhibition in the corpora cavernosa (middle; ×44 000). By 5 days of SHH inhibition in the corpora cavernosa, the smooth muscle layer surrounding sinuses appears narrowed in places from apoptosis (right; ×30 000). Arrows indicate apoptotic smooth muscle cells. CC, corpora cavernosa; S, smooth muscle; E, endothelium; Si, sinus. C) Retrograde transport of 5E1 SHH inhibitor from the corpora cavernosa to the CN/pelvic ganglia was examined by IHC staining using a mouse secondary that would recognize the 5E1 SHH inhibitor. No staining was observed in the CN/pelvic ganglia, indicating that 5E1 SHH inhibitor delivered to the corpora cavernosa of adult Sprague-Dawley rats via Affi-Gel beads did not undergo retrograde transport to the neural tissue (left; ×250). The secondary antibody was functioning normally since ACTA1 staining (positive control for secondary) was visualized with this secondary antibody in penis tissue (middle; ×400). This result was confirmed by the presence of SHH staining in the pelvic ganglia/CN (right; ×160). Arrows indicate where staining would be if present (left), ACTA1 (middle), and SHH staining (right).

The CN and pelvic ganglia were isolated from rats treated with 5E1 SHH inhibitor in the corpora cavernosa for 2 days. CN/pelvic ganglia were stained with an anti-mouse antibody that recognized the 5E1 SHH inhibitor in order to determine if there was retrograde transport of the inhibitor to the CN/pelvic ganglia. Staining in the CN/pelvic ganglia was not observed with the anti-mouse antibody, although this antibody displayed staining in penile tissue when used as a secondary antibody to detect ACTA1, which was used as a positive control to ensure the secondary was functioning (Fig. 1). Positive staining for SHH protein was also identified in neurons of the pelvic ganglia.

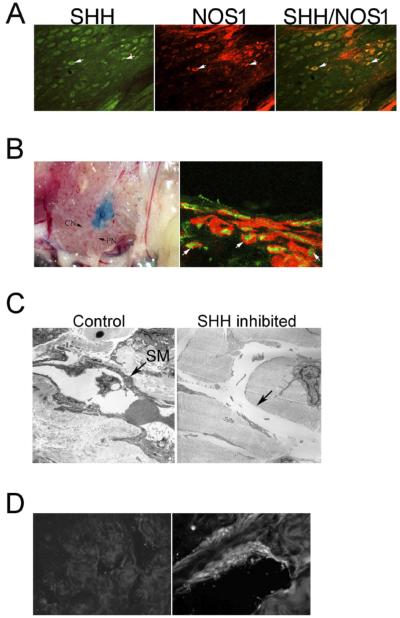

SHH Protein Is Present in NOS1-Positive Neurons of the Pelvic Ganglia

Normal pelvic ganglia/CN of adult Sprague-Dawley rats underwent IHC analysis with antibodies that recognized SHH and NOS1 proteins. SHH colocalized with NOS1 in neurons of the pelvic ganglia that innervate the penis (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

A) Dual IHC analysis of pelvic ganglia assayed with SHH (left) and NOS1 (middle). SHH and NOS1 colocalize in neurons of the pelvic ganglia (right), indicating that SHH is present in neurons that innervate the penis. Arrows indicate SHH and NOS1 staining. Original magnification ×160. B) 5E1 SHH inhibitor was soaked in Affi-Gel beads and injected under the pelvic ganglia of adult Sprague-Dawley rats (left; ×100). Rats were killed after 2 days of SHH inhibition in the pelvic ganglia, and penis tissue was assayed for both TUNEL and ACTA1 staining (right; ×1000). Apoptosis was present in the smooth muscle of the corpora cavernosa after 2 days of SHH inhibition in the pelvic ganglia. Arrows indicate apoptotic smooth muscle cells. G, pelvic ganglion; CN, cavernous nerve; PN, pelvic nerve. C) Electron microscopic analysis of penis tissue from adult Sprague-Dawley rats that had been treated with 5E1 SHH inhibitor in the pelvic ganglia for 2 days. Control rats treated with PBS in the pelvic ganglia showed normal smooth muscle (left; ×70 000). However, sinuses of rats treated with SHH inhibitor in the pelvic ganglia showed diminished smooth muscle (right; ×30 000). Arrows indicate smooth muscle (SM) or where smooth muscle would appear if present. D) IHC analysis of corpora cavernosal tissue from adult Sprague-Dawley rats that were treated with 5E1 SHH inhibitor in the pelvic ganglia. The absence of staining in the presence of an anti-mouse antibody indicates that 5E1 SHH inhibitor is not transported down the axon from the pelvic ganglia to the corpora cavernosa (left; ×160). ACTA1 staining of penis tissue (positive control) indicates that the secondary antibody used was working fine (right; ×400).

Apoptosis Induction after SHH Inhibition in the Pelvic Ganglia for 1 and 2 Days

Affi-Gel beads soaked in 5E1 SHH inhibitor were implanted under the pelvic ganglia (Fig. 2). After 2 days of SHH inhibition in the ganglia, abundant apoptosis was observed in the corpora cavernosa by TUNEL staining (Fig. 2). The TUNEL staining colocalized with ACTA1, indicating that the smooth muscle of the corpora cavernosa was a target of SHH inhibition in the pelvic ganglia. Electron microscopy showed that the smooth muscle layer surrounding many sinuses was degraded by 2 days of SHH inhibition in the pelvic ganglia (Fig. 2).

The corpora cavernosa was isolated from rats treated with 5E1 SHH inhibitor in the pelvic ganglia for 2 days. Penis tissue was stained with a secondary antibody that recognized the 5E1 SHH inhibitor in order to determine if there was transport of the inhibitor down the axon to the corpora cavernosa. We did not see any staining in the corpora cavernosa with the secondary antibody, although this secondary was able to identify ACTA1 in penile tissue, which was used as a positive control to ensure the secondary was functioning (Fig. 2).

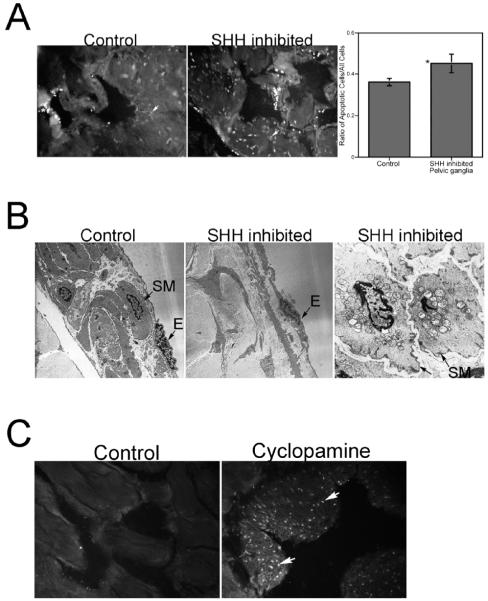

This experiment was repeated, the rats were killed after 1 day of SHH inhibition in the pelvic ganglia, and apoptosis was quantified in the corpora cavernosa. Apoptosis was significantly increased in the corpora cavernosa after 1 day of SHH inhibition in the pelvic ganglia (control = 0.36 ± 0.01, SHH inhibited = 0.45 ± 0.02, P = 0.011; Fig. 3). Electron microscopy confirmed that the apoptosis taking place was primarily in the smooth muscle (Fig. 3). Endothelial cells observed appeared normal (Fig. 3). SHH and NOS1 proteins were quantified in the same penis tissue. Image J analysis showed that SHH protein was significantly decreased in penis tissue from rats that had 1 day of SHH inhibitor treatment in the pelvic ganglia (control = 17.9 ± 0.19, SHH inhibited = 16.4 ± 0.34, P=0.007). NOS1 protein was similarly decreased in response to SHH inhibition in the pelvic ganglia by 1.2-fold (control=7.87 ± 0.54, SHH inhibited=6.71 ± 0.14, P=0.05). Intracavernosal pressure measurements were performed on rats treated with PBS (control) and SHH inhibitor in the pelvic ganglia. The ICP was decreased 34% in SHH inhibitor-treated rats (P=0.02).

FIG. 3.

A) TUNEL analysis of penis tissue from adult Sprague-Dawley rats treated with either PBS (control; left) or 5E1 SHH inhibitor (right) in the pelvic ganglia for 1 day. Apoptosis was significantly increased in penis tissue of rats treated with SHH inhibitor in the pelvic ganglia for 1 day. Arrows indicate apoptotic cells. Original magnification ×250. *, significant difference as measured by P < 0.5. B) Electron microscopic analysis of penis tissue from rats treated with PBS (control; left; ×30 000) and SHH inhibitor (middle and right) in the pelvic ganglia for 1 day. Control penis appeared normal with intact endothelium and smooth muscle. SHH-inhibited penis tissue showed a narrowed smooth muscle layer (middle; ×30 000) and abundant apoptotic smooth muscle cells (right; ×170 000). Endothelium appeared normal in SHH-inhibited tissues. SM, smooth muscle; E, endothelium. C) TUNEL staining of penis tissue from adult Sprague-Dawley rats treated with either DMSO (control; left) or 10 μM cyclopamine (a chemical inhibitor of SHH signaling; right) by a single injection under the pelvic ganglia. Seven days after injection, apoptosis was abundant in penis tissue of rats treated with cyclopamine in the pelvic ganglia, but not in control tissue. These results support the findings presented in A and B in which 5E1 SHH inhibitor was used in the experiments. Arrows indicate apoptotic cells. Original magnification ×250.

A second inhibitor of SHH signaling, cyclopamine, was used to confirm that SHH inhibition in the pelvic ganglia affects corpora cavernosa morphology. The basal level of apoptosis is lower in the corpora cavernosa of cyclopamine-treated rats (Fig. 3), which is most likely attributable to the manner in which the inhibitor was delivered. Cyclopamine was delivered by a single bolus injection underneath the ganglia, whereas 5E1 SHH inhibitor was time released by placing Affi-Gel beads under the ganglia. This appears to be a more disruptive methodology since the basal level of apoptosis in control animals was higher. However, abundant apoptosis was observed in the corpora cavernosa 7 days after cyclopamine treatment (Fig. 3), thus supporting our findings using the 5E1 SHH inhibitor.

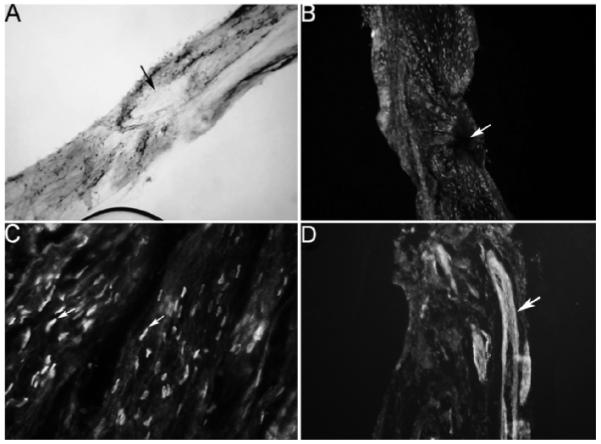

CN Tie Experiments Show that SHH Protein Does Not Travel down the Nerve to Affect Corpora Cavernosa Morphology

A tie was placed on CNs in adult Sprague-Dawley rats in order to determine if SHH protein was being transported from the pelvic ganglia to the corpora cavernosa via the CN. The CN and pelvic ganglia were excised 3 and 5 days after the tie was placed. IHC of the CN and pelvic ganglia assaying for SHH protein indicate that there is no buildup of SHH protein on either side of the tie (Fig. 4). However, SHH protein was identified in what are believed to be Schwann cells dispersed through out the entire CN (Fig. 4). Schwann cells were identified by dual staining with S100, a Schwann cell marker (data not shown). NOS1 IHC was also performed as a positive control to show that if anterograde transport was taking place protein would build up on the ganglia side of the tie as is observed for NOS1 (Fig. 4).

FIG. 4.

IHC analysis assaying for SHH protein in CN that had a tie placed around the nerve to block transport for 3 days in adult Sprague-Dawley rats. CNs were assayed for SHH protein using both colorimetric (A; ×100) and fluorescent (B; ×100) staining. SHH protein did not build up on either side of the tie, indicating that SHH protein is not transported down the nerve to the corpora cavernosa. Arrows indicate where the tie was placed. However, SHH protein was observed in cells distributed through out the CN (C; ×400). These cells were identified as Schwann-like cells that stain positively for S100. Arrow indicates SHH protein. D) NOS1 IHC of the CN 3 days after the tie was placed shows that protein would build up in the presence of the tie if transport is taking place (×100).

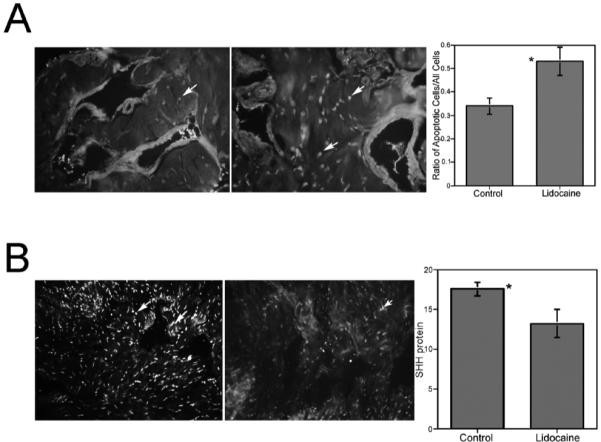

Apoptosis Is Increased and SHH Protein Is Decreased in the Corpora Cavernosa after Lidocaine Treatment of the CN

TUNEL assay was performed on penis tissue isolated from adult Sprague-Dawley rats that had their CNs treated bilaterally with either lidocaine or PBS, in order to determine the effect of cessation of neural activity on corpora cavernosal apoptosis. Apoptosis was significantly increased in lidocaine-treated (0.53 ± 0.059) rats over PBS-treated control rats (0.34 ± 0.35, P = 0.049; Fig. 5).

FIG. 5.

A) TUNEL assay of penis tissue isolated from adult Sprague-Dawley rats treated with either PBS (control; left) or 2% lidocaine (right) via Gel-Foam placed on top of the CN. Apoptosis was significantly increased in the corpora cavernosa of lidocaine-treated rats. Arrows indicate apoptotic cells. Original magnification ×250. *, significant difference as measured by P < 0.5. B) Image J analysis of IHC assayed for SHH protein in penis tissue isolated from adult Sprague-Dawley rats treated with either PBS (control; left) or 2% lidocaine via Gel-Foam on the CN (right). SHH protein was significantly decreased in lidocaine-treated rats. Arrows indicate SHH protein. Original magnification ×160. Total fluorescence values are given in the graph. *, significant difference as measured by P < 0.5.

Fluorescent IHC analysis was performed to assay for SHH protein in this same penis tissue in order to determine the effect of cessation of neural activity on corpora cavernosal SHH abundance. Image J analysis revealed that SHH protein was significantly decreased in lidocaine-treated (13.2 ± 1.77) corpora cavernosa over PBS-treated control corpora cavernosa (17.5 ± 0.08, P = 0.01; Fig. 5). The intracavernosal pressure was measured in control and lidocaine-treated rats. The maximal intracavernosal pressure was reduced from 80 mm Hg in control animals to 32.5 mm Hg in lidocaine-treated rats, indicating significant ED caused by the loss of neural activity.

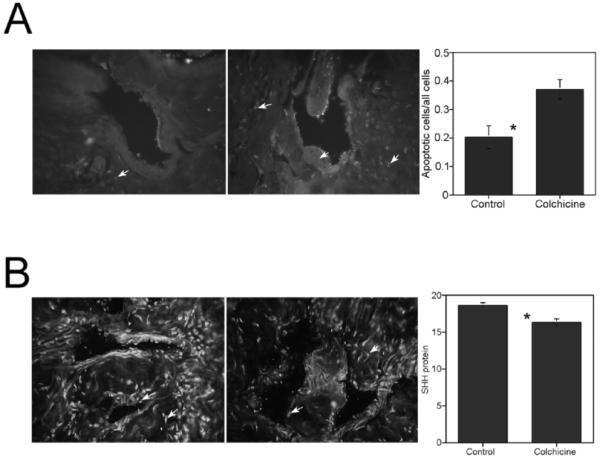

SHH Protein Is Decreased and Apoptosis Increased in the Corpora Cavernosa after Colchicine Treatment of the CN

TUNEL assay was performed on penis tissue isolated from adult Sprague-Dawley rats that had their CNs treated bilaterally with either colchicine or PBS in order to determine the effect of blocking neural transport on corpora cavernosal apoptosis. Apoptosis was significantly increased in colchicine-treated rats (0.37 ± 0.03) over PBS-treated control rats (0.21 ± 0.04, P = 0.015; Fig. 6).

FIG. 6.

A) TUNEL assay of penis tissue isolated from adult Sprague-Dawley rats treated with either PBS (control; left) or 5 mM colchicine (right) via Gel-Foam placed on top of the CN. Apoptosis was significantly increased in the corpora cavernosa of colchicine-treated rats. Arrows indicate apoptotic cells. Original magnification ×250. *, significant difference as measured by P < 0.5. B) Image J analysis of IHC assayed for SHH protein in penis tissue isolated from adult Sprague-Dawley rats treated with either PBS (control; left) or 5 mM colchicine via Gel-Foam on the CN (right). SHH protein was significantly decreased in colchicine-treated rats. Arrows indicate SHH protein. Original magnification ×250. Total fluorescence values are given in the graph. *, significant difference as measured by P < 0.5.

Fluorescent IHC analysis was performed to assay for SHH protein in this same penis tissue in order to determine the effect of cessation of neural transport on corpora cavernosa SHH abundance. Image J analysis revealed that SHH protein was significantly decreased in colchicine-treated corpora cavernosa (16.30 ± 0.41) over PBS-treated control corpora cavernosa (18.59 ± 0.34, P = 0.006; Fig. 6). The intracavernosal pressure/blood pressure was measured in control and colchicine-treated rats. The maximal intracavernosal pressure/blood pressure remained unchanged in colchicine-treated rats, indicating that short-term blockade of neural transport did not affect erectile function.

DISCUSSION

In these studies we continue our investigation of the relationship between neural innervation, SHH signaling in the nerves, and SHH protein expression in the penile corpora cavernosa and maintenance of corpora cavernosa morphology in the adult penis. SHH protein is normally expressed in neurons of the pelvic ganglia that innervate the penis and in smooth muscle of the penile corpora cavernosa. Inhibition of SHH protein in the corpora cavernosa causes a 12-fold increase in apoptosis in the corpora cavernosal smooth muscle, which results in erectile dysfunction [20]. CN injury also causes a significant increase in smooth muscle apoptosis in the penis that correlates with significantly decreased SHH protein in the corpora cavernosa and with ED [20]. In this study we have shown that SHH inhibition in the pelvic ganglia causes a 1.3-fold increase in apoptosis and a 1.1-fold decrease in SHH protein in the corpora cavernosa of the penis. The level of apoptosis observed after SHH inhibition in the pelvic ganglia (20% or 1.3-fold) is more modest when compared to direct inhibition in the corpora cavernosa (12-fold). However, the experiments are not readily comparable since the Affi-Gel bead technology used to deliver the SHH inhibitor directly to the corpora cavernosa only allows for measurement of apoptosis in a limited region around the beads where it can be certain that inhibitor has reached. The farther away one gets from the beads the apoptosis levels decrease. The 12-fold increase in apoptosis was measured within 130 μm of the beads. If a larger margin was used the increase would not be as high. This is an inherent limitation of this technology. On the other hand, the decrease in apoptosis in the corpora cavernosa measured when SHH was inhibited in the pelvic ganglia was measured at random in large cross sections of the penis and is, therefore, a more realistic evaluation of the apoptosis levels in the entire tissue. Also, the apoptosis measurements made after SHH inhibition in the pelvic ganglia were performed after only 1 day of SHH inhibition, whereas apoptosis was shown to increase 12-fold after direct inhibition in the corpora cavernosa after 7 days of inhibition. It is possible that apoptosis levels might reach the 12-fold level if SHH inhibition was allowed to proceed longer in the pelvic ganglia. The fact that SHH inhibition in the pelvic ganglia causes a 20% increase in apoptosis after only 1 day of inhibition in the pelvic ganglia and that this has a significant impact on intracavernosal pressure measurements suggest that, at a minimum, SHH is a significant regulator of apoptosis induction in the penis and presents a unique opportunity for intervention in preventing prostatectomy-induced ED of neurogenic origin. This does not exclude other factors impacting apoptosis induction as well.

We propose the hypothesis that SHH signaling in the pelvic ganglia is necessary to maintain normal corpora cavernosa morphology, penile SHH protein expression, and erectile function. The relationship between SHH protein in the nerves and SHH protein expression in the corpora cavernosa is multifactorial and may arise because of several different mechanisms: 1) transport of SHH from the pelvic ganglia to the corpora cavernosa via the CN; 2) transport of a trophic factor from the pelvic ganglia to the corpora, which regulates SHH signaling in the corpora cavernosa; and 3) neural activity influences on SHH signaling in the corpora cavernosa. The presence of SHH in the ganglia and CN may be required for maintenance of neural integrity, which in turn affects corpora cavernosal morphology. We have examined each of these potential mechanisms independently.

In order to explore the first potential mechanism, we examined if SHH protein travels down the CN to regulate penile morphology in the corpora cavernosa. Anterograde axonal transport of active SHH protein has been observed previously in the adult optic nerve [45], so there is precedent for neural anterograde transport of SHH protein. When CN tie experiments were performed, a buildup of SHH protein on the ganglia side of the tie was not observed, indicating that SHH protein does not undergo transport to the corpora cavernosa. Since SHH is present in the pelvic ganglia/CN and since inhibition of SHH in the pelvic ganglia affects penile morphology and SHH protein abundance in the corpora cavernosa, it is likely that the presence of SHH in neurons of the pelvic ganglia is involved in maintaining neural integrity, which in turn affects corpora cavernosal morphology. The localization of SHH in Schwann-like cells of the CN supports this hypothesis and is potentially significant since Schwann cell seeded guidance tubes have been used in several studies to aid CN regeneration and to restore erectile function [46, 47]. Thus SHH signaling may impact erectile function in a two-pronged manner via morphological changes in the corpora cavernosal smooth muscle and by maintaining neural integrity via its presence in Schwann-like cells of the CN. Alternative roles for SHH in the nerves may involve regulation of conduction velocity and axon growth and guidance, as has been shown in motor and sensory neurons and in retinal ganglion cells, respectively [48, 49]. Desert hedgehog (DHH), an isoform of SHH, is expressed in both developing and adult peripheral nerves, and degeneration of myelinated fibers is more severe in sciatic nerves of Dhh-null mice [50, 51]. This suggests that more than one hedgehog isoform may play a role in maintaining neural integrity. SHH protein was also localized in NOS1-staining neurons of the pelvic ganglia that provide innervation to the penis. Therefore, inhibition of SHH in the pelvic ganglia may affect penis morphology by interrupting innervation to the penis. These findings are significant in that they show that SHH protein is not traveling down the nerve to influence SHH signaling in the corpora cavernosa, and they identify SHH as a potential mediator of neural integrity and/or function. Further study is required to determine the mechanism of SHH impact on the CN and pelvic ganglia.

In mechanism two, we have examined if an unidentified trophic factor synthesized in the pelvic ganglia and transported by the CN to the corpora cavernosa is responsible for influencing SHH protein expression in the corpora cavernosa and thus corpora cavernosal morphology. These experiments were performed in adult Sprague-Dawley rats by applying colchicine to the CN via Gel-Foam. The axonal transport of synthesized proteins from the soma to the nerve terminals depends on the polymerization of tubulin, the principal constituent of microtubules. Colchicine, which is able to inhibit the polymerization of tubulin, prevents biological processes where microtubules are involved, including blockade of anterograde and retrograde transport, which ultimately causes Wallerian degeneration if blockade is maintained for 3–7 days [52-56]. Rats were killed at 2 days following colchicine treatment, and TUNEL assay for apoptosis was performed. The rationale behind these experiments is that if a trophic factor transported by the nerve is necessary to influence SHH protein expression in the corpora cavernosa and corpora cavernosal morphology, then apoptosis will be increased and SHH protein decreased in the corpora cavernosa following colchicine treatment. In these experiments, apoptosis was increased 1.8-fold and SHH protein abundance was decreased 1.2-fold in the penis after colchicine treatment. These results show that neural transport of trophic factors is necessary to maintain SHH signaling and the smooth muscle morphology of the corpora cavernosa in the penis. Identification of the factor(s) responsible for SHH regulation in the corpora cavernosa requires further study.

In mechanism three we examined if CN activity influences SHH protein in the corpora cavernosa, normal corpora cavernosa morphology, and apoptosis induction in the penis. These studies were performed in adult Sprague-Dawley rats by application of lidocaine-soaked Gel-Foam to the CN. TUNEL analysis and changes in SHH protein in the penis were quantified. Lidocaine has been well established as an inhibitor of neural activity. Lidocaine also inhibits transport if used at high dosages. If neural activity is necessary to regulate SHH signaling in the penis and the smooth muscle morphology of the corpora cavernosa, then inhibiting neural activity with lidocaine would cause a decrease in SHH protein in the corpora cavernosa and increased apoptosis in the corpora cavernosal smooth muscle. In these experiments, it was found that SHH protein was significantly decreased 1.3-fold and apoptosis was significantly increased 1.6-fold in lidocaine-treated corpora cavernosal tissue. The intracavernosal pressure was measured in control and lidocaine-treated rats, and all lidocaine-treated rats exhibited significantly reduced erectile function, indicating that the lidocaine was effective in reducing/suppressing neural activity. Both NOS1 (n-NOS) and NOS3 (e-NOS) have been shown to be up-regulated in response to SHH treatment in the corpora cavernosa and down-regulated in response to SHH inhibition [57], so it is possible that SHH serves a similar role in the CN by influencing NOS transport from the pelvic ganglia through the CN to the nerve terminal where NO is released. This hypothesis is supported by the observation that SHH plays a role in regulation of conduction velocity in motor and sensory neurons [48] and that application of subnanomolar SHH protein to a slice preparation of the ventrolateral nucleus tractus solitarius (neuronal network integrating cardiovascular, respiratory, and digestive regulations) induced a rapid decrease in neuronal firing, followed by a bursting activity that propagated in the neuronal network [58]. Intracellular injections show that bursts result from an action on the neuronal membrane electroresponsiveness. Decreased neuronal firing and bursting activity were blocked by the 5E1 SHH inhibitor [58]. These findings are significant in that they suggest that neural activity is necessary to influence SHH signaling in the corpora cavernosa and the smooth muscle morphology of the corpora cavernosa.

The mechanism of how apoptosis is induced in the adult penis when neural activity is decreased and the role that SHH plays in this process, both in the nerves and in the corpora cavernosa smooth muscle, require further experimentation. However, we can speculate about the role that SHH signaling plays in this process based on what is known about SHH signaling during embryogenesis of the penis and in other organs. SHH is a regulator of apoptosis in the embryonic penis [26, 27]. In the adult penis, decreased SHH signaling induces apoptosis [20], and decreased SHH protein observed in two animal models of neuropathy is associated with significantly elevated apoptosis [14, 20]. In other organs it has been well established that inhibition of SHH signaling is a cause of apoptosis induction [59-65]. However, the mechanism of how this occurs remains unclear. Recently it has been shown that when SHH is not bound to its receptor PTCH1, the cell death program is initiated by the proapoptotic dependence receptor PTCH1 [59]. This requires preliminary cleavage of PTCH’s intracellular domain by caspase enzymes. Cleavage of PTCH1 by caspase-3 (and less frequently by 7 and 8, [60]) exposes a carboxyl-terminal apoptotic domain, which results in apoptosis induction [61]. PTCH1 induction of apoptosis when SHH is not bound is supported by the following findings: transfecting cultured cells with the carboxy-terminal apoptotic region of PTCH1 is sufficient to induce cell death [59], apoptosis is stimulated by PTCH1 receptor expression in the absence of SHH binding [61], increased TUNEL staining is associated with PTCH1 overexpression [60], and SHH treatment can inhibit PTCH1-induced cell death in a dose-dependent manner [60]. Whether PTCH1 induction of apoptosis involves SMO remains controversial since reports from the literature have shown PTCH1-dependent cell death independent of SMO [66]. However, cyclopamine, an SMO inhibitor, has been shown to induce apoptosis in a caspase-3 dependent manner [67]. How neural activity and SHH in the nerves influence SHH signaling and smooth muscle apoptosis in the corpora cavernosa will require further experimentation to elucidate. However, this is a significant question since two animal models of erectile dysfunction, the CN-injured Sprague-Dawley rat and the BB/WOR diabetic rat, exhibit decreased SHH signaling, increased apoptosis, and significant neuropathy.

Taken together these results suggest that neural activity and a trophic factor from the pelvic ganglia/CN influence SHH signaling in the corpora cavernosa and the smooth muscle morphology of the corpora cavernosa, and they identify SHH as a potential mediator of neural integrity and/or function. Further study is required to determine the mechanism of SHH impact on the CN and pelvic ganglia.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors would like to thank Kevin McKenna, Ph.D., for aid with intracavernosal pressure measurements in lidocaine- and colchicine-treated rats and for insightful discussion.

Footnotes

Supported by National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases grants DK068507 and DK062970.

REFERENCES

- 1.Selvin E, Burnett AL, Platz EA. Prevalence and risk factors for erectile dysfunction in the US. Am J Med. 2007;120:151–157. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2006.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Perimenis P, Markou S, Gyftopoulos K, Athanasopoulos A, Giannitsas K, Barbalias G. Switching from long-term treatment with self-injections to oral sildenafil in diabetic patients with severe erectile dysfunction. Eur Urol. 2002;41:387–391. doi: 10.1016/s0302-2838(02)00032-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Raina R, Agarwal A, Zippe CD. Management of erectile dysfunction after radical prostatectomy. Urology. 2005;66:923–929. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2005.05.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kendirci M, Teloken PE, Champion HC, Hellstrom WJ, Bivalacqua TJ. Gene therapy for erectile dysfunction: fact or fiction? Eur Urol. 2006;50:1157–1159. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2006.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Feldman HA, Goldstein I, Hatzichristou DG, Krane RJ, McKinley JB. Impotence and its medical and psychosocial correlates: results of the Massachusetts Male Aging Study. J Urol. 1994;151:54–61. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)34871-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hakim LS, Goldstein I. Diabetic sexual dysfunction. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 1996;25:379–400. doi: 10.1016/s0889-8529(05)70329-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Katz A. What happened? Sexual consequences of prostate cancer and its treatment. Can Fam Physician. 2005;51:977–982. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alivizatos G, Skolarikos A. Incontinence and erectile dysfunction following radical prostatectomy: a review. Sci World J. 2005;5:747–758. doi: 10.1100/tsw.2005.94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Penson DF, McLerran D, Feng Z, Li L, Albertsen PC, Gilliland FD, Hamilton A, Hoffman RM, Stephenson RA, Potosky AL, Stanford JL. 5-year urinary and sexual outcomes after radical prostatectomy: results from the prostate cancer outcomes study. J Urol. 2005;173:1701–1705. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000154637.38262.3a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kendirci M, Hellstrom WJ. Current concepts in the management of erectile dysfunction in men with prostate cancer. Clin Prostate Cancer. 2004;3:87–92. doi: 10.3816/cgc.2004.n.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vale J. Erectile dysfunction following radical therapy for prostate cancer. Radiother Oncol. 2000;57:301–305. doi: 10.1016/s0167-8140(00)00293-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Crawford ED, Bennett CL, Stone NN, Knight SJ, DeAntoni E, Sharp L, Garnick MB, Porterfield HA. Comparison of perspectives on prostate cancer: analyses of survey data. Urology. 1997;50:366–372. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(97)00254-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alici B, Gumustas MK, Ozkara H, Akkus E, Demirel G, Yencilek F, Hattat H. Apoptosis in the erectile tissues of diabetic and healthy rats. BJU International. 2000;85:326–329. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.2000.00420.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Podlasek CA, Zelner DJ, Harris JD, Meroz CL, McKenna KE, McVary KT. Altered Sonic hedgehog signaling is associated with morphological abnormalities in the BB/WOR diabetic penis. Biol Reprod. 2003;69:816–827. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.102.013508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu J, Xia R, Fu W, Chen Y, Liu G. Apoptosis and hemodynamic changes of the penile tissue in diabetic rats. Zhonghua Nan Ke Xue. 2004;10:445–448. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang D, Xie H, Wang G. Apoptosis and the expression of Bax and Bcl-2 in the penis of diabetic rats. Zhonghua Nan Ke Xue. 2004;10:844–848. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yamanaka M, Shirai M, Shiina H, Tanaka Y, Enokida H, Tsujimura A, Matsumiya K, Okuyama A, Dahiya R. Vascular endothelial growth factor restores erectile function through inhibition of apoptosis in diabetic rat penile crura. J Urol. 2005;173:318–323. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000141586.46822.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Klein LT, Miller MI, Buttyan R, Raffo AJ, Burchard M, Devris G, Cao YC, Olsson C, Shabsigh R. Apoptosis in the rat penis after penile denervation. J Urol. 1997;158:626–630. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.User HM, Hairston JH, Zelner DJ, McKenna KE, McVary KT. Penile weight and cell subtype specific changes in a post-radical prostatectomy model of erectile dysfunction. J Urol. 2003;169:1175–1179. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000048974.47461.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Podlasek CA, Meroz CL, Tang Y, McKenna KE, McVary KT. Regulation of cavernous nerve injury-induced apoptosis by Sonic hedgehog. Biol Reprod. 2007;76:19–28. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.106.053926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Podlasek CA, Zelner DJ, Jiang HB, Tang Y, Houston J, McKenna KE, McVary KT. Shh cascade is required for penile postnatal morphogenesis, differentiation and adult homeostasis. Biol Reprod. 2003;68:423–438. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.102.006643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Iacono F, Giannella R, Somma P, Manno G, Fusco F, Mirone V. Histological alterations in cavernous tissue after radical prostatectomy. J Urol. 2005;173:1673–1676. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000154356.76027.4f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schwartz EJ, Wong P, Graydon RJ. Sildenafil preserves intracorporeal smooth muscle after radical retropubic prostatectomy. J Urol. 2004;171:771–774. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000106970.97082.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yaman O, Yilmaz E, Bozlu M, Anafarta K. Alterations of intracorporal structures in patients with erectile dysfunction. Urol Int. 2003;71:87–90. doi: 10.1159/000071101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fraiman MC, Lepor H, McCullough AR. Changes in penile morphometrics in men with erectile dysfunction after nerve-sparing radical retropublic prostatectomy. Mol Urol. 1999;3:109–115. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Haraguchi R, Mo R, Hui C, Motoyama J, Makino S, Shiroishi T, Gaffield W, Yamada G. Unique functions of Sonic hedgehog signaling during external genitalia development. Development. 2001;128:4241–4250. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.21.4241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Perriton CL, Powles N, Chiang C, Maconochie MK, Cohn MJ. Sonic hedgehog signaling from the urethral epithelium controls external genital development. Dev Biol. 2002;247:26–46. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2002.0668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pepinsky RB, Rayhorn P, Day ES, Dergay A, Williams KP, Galdes A, Taylor FR, Boriack-Sjodin PA, Garber EA. Mapping sonic hedgehog-receptor interactions by steric interference. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:10995–11001. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.15.10995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hooper JE, Scott MP. The Drosophila patched gene encodes a putative membrane protein required for segmental patterning. Cell. 1989;59:751–765. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90021-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nakano Y, Guerrero I, Hidalgo A, Taylor A, Whittle JRS, Ingham PW. A protein with several possible membrane-spanning domains encoded by the Drosophila segment polarity gene patched. Nature. 1989;341:508–513. doi: 10.1038/341508a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Goodrich LV, Johnson RL, Milenkovic L, McMahon JA, Scott MP. Conservation of the hedgehog/patched signaling pathway from flies to mice: induction of a mouse patched gene by Hedgehog. Genes Dev. 1996;10:301–312. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.3.301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stone DM, Hynes M, Armanini M, Swanson TA, Gu Q, Johnson RL, Scott MP, Pennica D, Goddard A, Phillips H, Noll M, Hooper JE, et al. The tumor-suppressor gene patched encodes a candidate receptor for Sonic hedgehog. Nature. 1996;14:129–134. doi: 10.1038/384129a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Taipale J, Cooper MK, Maiti T, Beachy PA. Patched acts catalytically to suppress the activity of Smoothened. Nature. 2002;418:892–897. doi: 10.1038/nature00989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hidalgo A, Ingham P. Cell patterning in the Drosophila segment: spatial regulation of the segment polarity gene patched. Development. 1990;110:291–301. doi: 10.1242/dev.110.1.291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ingham PW, Taylor AM, Nakano Y. Role of the Drosophila patched gene in positional signaling. Nature. 1991;353:184–187. doi: 10.1038/353184a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Capdevila J, Estrada MP, Sanchez-Herrero E, Guerrero I. The Drosophila segment polarity gene patched interacts with decapentaplegic in wing development. EMBO J. 1994;13:71–82. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06236.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Alexandre C, Jacinto A, Ingham PW. Transcriptional activation of hedgehog target genes in Drosophila is mediated directly by the cubitus interruptus protein, a member of the GLI family of zinc finger DNA-binding proteins. Genes Dev. 1996;10:2003–2013. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.16.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dominguez M, Brunner M, Hafen E, Basler K. Sending and receiving the hedgehog signal: control by the Drosophila Gli protein Cubitus interruptus. Science. 1996;272:1621–1625. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5268.1621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hepker J, Wang I-T, Motzny CK, Holmgran R, Orenic TV. Drosophila cubitus interruptus forms a negative feedback loop with patched and regulates expression of Hedgehog target genes. Development. 1997;124:549–558. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.2.549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tuttle JB, Steers WD, Albo M, Nataluk E. Neural input regulates NGF and growth of the adult urinary bladder. J Auton Nerv Syst. 1994;49:147–158. doi: 10.1016/0165-1838(94)90134-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Giuliano F, Rampin O, Bernabé J, Rousseau J-P. Neural control of penile erection in the rat. J Auton Nerv Syst. 1995;55:36–44. doi: 10.1016/0165-1838(95)00025-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rasband WS. Image J. U.S. National Institutes of Health; Bethesda, MD: 19972007. World Wide Web ( http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij/) [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tang Y, Rampkin O, Calas A, Facchinetti P, Giuliano F. Oxytocinergic and serotonergic innervation of identified lumbosacral nuclei controlling penile erection in the male rat. Neuroscience. 1998;82:241–254. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(97)00290-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hetts SW. To die or not to die: an overview of apoptosis and its role in disease. J Am Med Assoc. 1998;279:300–307. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.4.300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Traiffort E, Moya KL, Faure H, Hassig R, Ruat M. High expression and anterograde axonal transport of aminoterminal sonic hedgehog in the adult hamster brain. Eur J Neurosci. 2001;14:839–850. doi: 10.1046/j.0953-816x.2001.01708.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.May F, Weidner N, Matiasek K, Caspers C, Mrva T, Vroemen M, Henke J, Lehmer A, Schwaibold H, Erhardt W, Gansbacher B, Hartung R. Schwann cell seeded guidance tubes restore erectile function after ablation of cavernous nerves in rats. J Urol. 2004;172:374–377. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000132357.05513.5f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.May F, Vroemen M, Matiasek K, Henke J, Brill T, Lehmer A, Apprich M, Erhardt W, Schoeler S, Paul R, Blesch A, Hartung R, et al. Nerve replacement strategies for cavernous nerves. Eur Urol. 2005;48:372–378. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2005.04.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Calcutt NA, Allendoerfer KL, Mizisin AP, Middlemas A, Freshwater JD, Burgers M, Ranciato R, Delcroix J-D, Taylor FR, Shapiro R, Strauch K, Dudek H, et al. Therapeutic efficacy of sonic hedgehog protein in experimental diabetic neuropathy. J Clin Invest. 2003;111:507–514. doi: 10.1172/JCI15792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kolpak A, Zhang J, Bao Z-Z. Sonic hedgehog has a dual effect on the growth of retinal ganglion axons depending on its concentration. J Neurosci. 2005;25:3432–3441. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4938-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bajestan SN, Umehara F, Shirahama Y, Itoh K, Sharghi-Namini S, Jessen KR, Mirsky R, Osame M. Desert hedgehog-patched 2 expression in peripheral nerves during Wallerian degeneration and regeneration. J Neurobiol. 2006;66:243–255. doi: 10.1002/neu.20216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Parmantier E, Lawson LB, Turmaine M, Namini SS, Chakrabarti L, McMahon AP, Jessen KR, Mirsky R. Schwann cell-derived Desert hedgehog controls the development of peripheral nerve sheaths. Neuron. 1999;23:713–724. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)80030-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Angevine JB., Jr. Nerve destruction by colchicines in mice and golden hamsters. J Exp Zool. 1957;136:363–391. doi: 10.1002/jez.1401360209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ginn SR, Peterson GM. Studies related to the use of colchicine as a neurotoxin in the septohippocampal cholinergic system. Brain Res. 1992;590:144–152. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(92)91090-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Singer M, Steinberg MC. Wallerian degeneration: a reevaluation based on transected and colchicine-poisoned nerves in the amphibian, Triturus. Am J Anat. 1972;133:51–83. doi: 10.1002/aja.1001330105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Aquino JB, Musolino PL, Coronel MF, Villar MJ, Setton-Avruj CP. Nerve degeneration is prevented by a single intraneural apotransferrin injection into colchicine-injured sciatic nerves in the rat. Brain Res. 2006;1117:80–91. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.02.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lecci A, Patacchini R, de Giorgio R, Corinaldesi R, Theodorsson E, Giuliani S, Santicioli P, Maggi CA. Functional, biochemical and anatomical changes in the rat urinary bladder induced by perigangliar injection of colchicines. Neuroscience. 1996;71:285–296. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(95)00422-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Podlasek CA, Meroz CL, Korolis H, Tang Y, McKenna KE, McVary KT. Sonic hedgehog, the penis and erectile dysfunction: a review of sonic hedgehog signaling in the penis. Curr Pharm Des. 2005;11:4011–4027. doi: 10.2174/138161205774913408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Pascual O, Traiffort E, Baker DP, Galdes A, Ruat M, Champagnat J. Sonic hedgehog signaling in neurons of adult ventrolateral nucleus tractus solitarius. Euro J Neurosci. 2005;22:389–396. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2005.04223.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Guerrero I, Altaba ARI. Longing for ligand: Hedgehog, patched, and cell death. Science. 2003;301:774–776. doi: 10.1126/science.1088625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Thibert C, Teillet M-A, Lapointe F, Mazelin L, Le Douarin NM, Mehlen P. Inhibition of neuroepithelial patched-induced apoptosis by Sonic hedgehog. Science. 2003;301:843–846. doi: 10.1126/science.1085405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Chao MV. Dependence receptors: what is the mechanism? Sci STKE. 2003;200:PE38. doi: 10.1126/stke.2003.200.pe38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tavella S, Biticchi R, Morello R, Castagnola P, Musante V, Costa D, Cancedda R, Garofalo S. Forced chondrocyte expression of sonic hedgehog impairs joint formation affecting proliferation and apoptosis. Matrix Biol. 2006;25:389–397. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2006.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Yamamoto Y, Stock DW, Jeffery WR. Hedgehog signaling controls eye degeneration in blind cavefish. Nature. 2004;431:844–847. doi: 10.1038/nature02864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Yeo W, Gautier J. Early neural cell death: dying to become neurons. Dev Biol. 2004;274:233–244. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2004.07.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Oppenheim RW, Homma S, Marti E, Prevette D, Wang S, Yaginuma H, McMahon AP. Modulation of early but not later stages of programmed cell death in embryonic avian spinal cord by sonic hedgehog. Mol Cell Neurosci. 1999;13:348–361. doi: 10.1006/mcne.1999.0755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ingham P, McMahon A. Hedgehog signaling in animal development: paradigms and principles. Genes Dev. 2001;15:3059–3087. doi: 10.1101/gad.938601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Athar M, Li C, Tang X, Chi S, Zhang X, Kim AL, Tyring SK, Kopelovich L, Hebert J, Epstein EH, Jr, Bickers SR, Xie J. Inhibition of smoothened signaling prevents ultraviolet B-induced basal cell carcinomas through regulation of Fas expression and apoptosis. Cancer Research. 2004;64:7545–7552. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]