Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Since 2008, all pediatric deaths in British Columbia have been reported to the coroner. The cause of death in pediatric sudden unexpected death (SUD) remains undetermined in 10% to 30% of cases. Before 2008, there was no standardized approach for referring relatives of SUD victims for follow-up medical testing to determine whether they were affected by the same condition. In the current era, genetic testing for primary electrical diseases can be used in cases of undetermined SUD when existing diagnostic methods fail.

OBJECTIVE:

To improve the clinical care of surviving relatives of SUD victims, the current practice of assessment of SUD in British Columbia was reviewed. The study also aimed to determine the prevalence of SUD and sudden cardiac death, types of postmortem investigations performed in SUD, and the use of genetic testing for primary electrical diseases in SUD from 2005 to 2007.

METHODS:

Cases involving individuals zero to 35 years of age, with a death due to natural disease or an undetermined cause were compiled from the British Columbia Coroners Service database. Cases were determined to be either sudden death due to a previously diagnosed condition or SUD.

RESULTS:

In individuals zero to 35 years of age, the prevalence of SUD was 9.21 per 100,000 and the prevalence of sudden cardiac death was 5.26 per 100,000. There were 35 cases of SUD in which a cause of death was unidentified after autopsy (autopsy-negative SUD). Specimens were collected, and specialists were consulted in 86% of these cases in the pediatric population and 14% in the adult population. A suggestion was made to relatives to seek medical attention in 26% of the autopsy-negative SUDs, and molecular autopsy was discussed in 9% of cases but performed in none.

CONCLUSION:

Currently, SUD in British Columbia is not managed in a way that optimizes a timely diagnosis for surviving relatives. A standardized protocol for SUD is needed to ensure optimization of diagnosis, genetic testing and referral of surviving relatives.

Keywords: Arrhythmia, Autopsy, Coroner, Sudden death

Abstract

HISTORIQUE :

Depuis 2008, tous les décès pédiatriques en Colombie-Britannique sont déclarés au coroner. La cause des morts subites inattendues (MSI) pédiatriques demeure indéterminée dans 10 % à 30 % des cas. Avant 2008, il n’existait pas de démarche standardisée pour aiguiller la parenté des victimes d’une MSI vers des examens médicaux afin de déterminer s’ils étaient atteints de la même maladie. Maintenant, on peut utiliser des tests de dépistage génétique des maladies électriques primaires dans les cas de MSI indéterminées lorsque les méthodes diagnostiques existantes échouent.

OBJECTIF :

Pour améliorer les soins cliniques de la parenté survivante de victimes de MSI, on a revu la pratique courante d’évaluation des MSI en Colombie-Britannique. L’étude visait également à déterminer la prévalence de MSI et de mort cardiaque subite, le type d’explorations postpartum effectuées après une MSI et le recours aux tests de dépistage génétique de maladies électriques primaires en cas de MSI entre 2005 et 2007.

MÉTHODOLOGIE :

Les auteurs ont compilé les cas mettant en cause des personnes de 0 à 35 ans, décédées de causes naturelles ou d’une cause indéterminée, dans la base de données du bureau des coroners de la Colombie-Britannique. On a déterminé que les cas étaient soit une mort subite imputable à une maladie déjà diagnostiquée, soit une MSI.

RÉSULTATS :

Chez les personnes de 0 à 35 ans, la prévalence de MSI était de 9,21 cas pour 100 000 habitants et celle de mort cardiaque subite, de 5,26 cas pour 100 000 habitants. Dans 35 cas de MSI, la cause du décès n’était pas établie après l’autopsie (MSI négative à l’autopsie). On a prélevé des échantillons et consulté des spécialistes dans 86 % des cas faisant partie de la population pédiatrique et dans 14 % des cas de la population adulte. On a suggéré à la parenté de consulter un médecin dans 26% des cas de MSI négative à l’autopsie, et on a abordé la possibilité d’une autopsie moléculaire dans 9 % des cas, sans jamais l’effectuer.

CONCLUSION :

À l’heure actuelle, la MSI en Colombie-Britannique n’est pas prise en charge de manière à optimiser un diagnostic opportun au sein de la parenté survivante. Un protocole standardisé à l’égard des MSI s’impose pour garantir l’optimisation du diagnostic, les tests de dépistage génétique et l’aiguillage de la parenté survivante.

Sudden unexpected death (SUD) is defined as a natural, unexpected fatal event that occurs within 1 h of the beginning of symptoms in an apparently healthy subject or in one whose disease was not so severe that such an abrupt outcome could have been predicted (1). Approximately 5000 to 7000 children die of SUD in the United States (US) each year (2). In young, otherwise healthy individuals, SUD is rare, with a frequency of 1.3 to 8.5 per 100,000 in the pediatric age group (1). A large proportion of SUD cases in the young are due to arrhythmias secondary to cardiac diseases, many of which are inherited (3,4). Inherited structural heart diseases include dilated cardiomyopathy, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy (1,3–6). These structural conditions are often apparent clinically during life, although the initial presentation can be catastrophic. SUD in the absence of structural heart disease is often due to primary electrical diseases that include long QT syndrome (LQTS), Brugada syndrome and catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia (CPVT) (5). These conditions can sometimes be diagnosed by evaluating surviving relatives or by postmortem genetic testing. When no cause can be identified, the cause may be idiopathic ventricular fibrillation (2).

An unexplained case of sudden death in young individuals has the greatest impact on the surviving relatives and family members. SUD can be the first manifestation of an autosomally inherited condition in a family and, therefore, the risk of surviving relatives being affected by the same condition is as high as 50%. The diagnosis of several of these conditions is not straightforward. As a result, surviving relatives must endure extensive investigations in the pursuit of finding a diagnosis (7). The number of conditions associated with SUD has continued to grow and it can be difficult to subject asymptomatic patients to a growing number of investigations without knowing what condition was present in the SUD victim. Adding to the complexity, primary electrical diseases can be missed or misdiagnosed based on screening tests, such as an electrocardiogram (5). Thus, determining a diagnosis in the deceased will lead to directed investigations that may save the lives of similarly affected family members.

In the current era of molecular genetics, the retrieval of genetic material at autopsy and subsequent analysis for genetic mutations that might cause a certain disease, sometimes referred to as a ‘molecular autopsy’ (8), offers an opportunity to make this diagnosis. Directed genetic testing is used broadly already. For example, pathologists use this technique to diagnose a variety of disorders leading to unexpected death in childhood including mitochondriopathies and disorders of fatty acid oxidation (9). In cases of undetermined SUD, it was recently shown that genetic testing can play a critical role in identifying ‘silent’ diseases such as LQTS (10), Brugada syndrome (5) and CPVT (11). However, testing for primary electrical diseases is a relatively new procedure, starting with the advent of commercial testing for LQTS, which was made available in 2004. Commercial testing now includes both CPVT and Brugada syndrome (12). This technique has been described as a 100% specific and sensitive method to determine those at risk (5).

To investigate ways of improving outcomes for surviving relatives of victims of SUD, we decided to review the system currently in place for dealing with SUD. In British Columbia (BC), all such cases are referred to the BC Coroners Service (BCCS), which is staffed primarily by lay coroners. The purpose of our study was threefold: to determine the incidence of SUD and sudden cardiac death (SCD) in the young in BC; determine which investigations are performed in cases of undetermined SUD in BC; and determine whether postmortem genetic testing for primary electrical diseases is being performed in BC.

METHODS

The authors collaborated with the BCCS to review the records of all reported deaths of individuals zero to 35 years of age occurring in BC from 2005 to 2007. Ethics approval was obtained and a research agreement with the BCCS was made. Deaths that are unnatural, sudden and unexpected, unexplained, and unattended are reported to the BCCS. The coroner’s investigation includes classifying the death into one of the following categories: suicide, accidental, natural, homicide or undetermined. The BCCS keeps a database of these cases, and the present study is a review of these cases. The total number of deaths reported and the number of deaths in each of the five categories was determined. A list was generated from the ‘natural’ and ‘undetermined’ categories, including cases satisfying the following criteria: the cause of death involved a natural disease process or was undetermined; the victim was zero to 35 years of age (to reduce overlap with atherosclerotic heart disease); and the death was sudden, with death or irreversible loss of consciousness occurring within 1 h of the onset of symptoms.

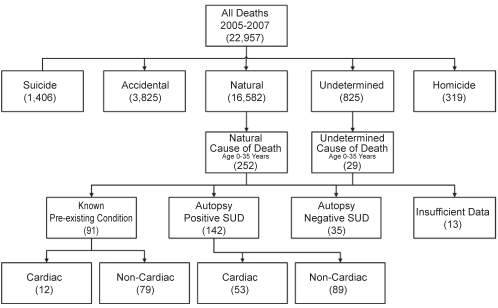

From this list of cases, the study cohort was formed using the definitions listed below as well as the flow diagram illustrated in Figure 1. All of the deaths occurring in people younger than 35 years of age that were classified as ‘natural’ or having an ‘undetermined’ cause were reviewed in detail. The deaths that were due to the anticipated outcome of a known disease process (eg, chronic renal failure) were reviewed and determined to have either a cardiac or noncardiac etiology. All of these cases were reviewed to ensure the death was consistent with the identified disease process and was not unexpected. Similarly, the cases in which the autopsy identified a cause of death were divided into cardiac or noncardiac etiology. The SUD cohort included all cases in which no premortem diagnosis was made. The remaining cases for which there was sufficient data comprised the group of SUD cases in which the autopsy was unable to identify a cause of death and the mode of death was consistent with a sudden unexpected event. A case was included in this group if the death was sudden and an autopsy revealed no cause of death, or if a potential risk factor for a cardiac arrhythmia was identified. SCD was deemed to have occurred in the subgroup of cases in which a pre- or postmortem diagnosis of cardiac disease was made, or in all cases in which the autopsy could not identify a cause of death and a cardiac arrhythmia was suspected.

Figure 1).

Flow diagram of study group formation. SUD Sudden unexpected death

A recommendation to see a medical professional was defined as a statement made in the coroner’s report or the autopsy report, or as a discussion between relatives and the coroner, or relatives and the pathologist that was recorded in the coroner’s investigative notes.

Prevalence and annualized incidence rates of SUD and SCD were calculated using population statistics for the province of BC for the study period.

RESULTS

From 2005 to 2007, 22,957 deaths were reported to the BCCS. These deaths were classified using the flow diagram shown in Figure 1. From all natural deaths, 1.5% of cases involved individuals zero to 35 years of age and from all undetermined deaths, 3.5% of cases involved individuals zero to 35 years of age.

Prevalence and incidence of SUD and SCD

The prevalence of SUD in BC from 2005 to 2007 in individuals zero to 35 years of age was 9.21 per 100,000, or 3.07 per 100,000 per year. The prevalence of SCD was found to be 5.26 per 100,000, or 1.75 per 100,000 per year. In the study period, the prevalence of SUD in BC in individuals 19 years of age or younger was 4.51 cases per 100,000 persons, or 1.50 cases per 100,000 persons per year. The prevalence of SCD in individuals 19 years of age or younger was 2.36 cases per 100,000 persons, or 0.78 cases per 100,000 persons per year.

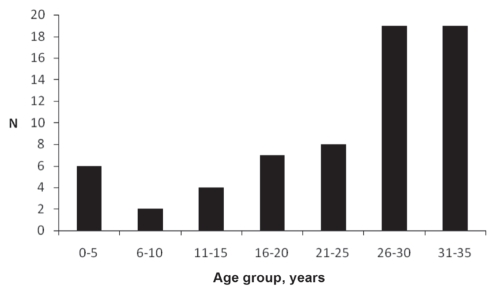

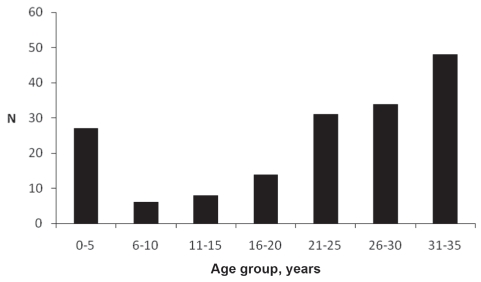

Autopsy-positive SUD and known pre-existing conditions

This group consisted of subjects in whom a cause of death was identified at autopsy or assigned based on the premortem history. These cases, while sudden, were not deemed unexpected from a medical perspective. The mean (± SD) age of death was 22.8±10.7 years (Figure 2). In this group, 65 patients were identified to have heart disease, with 12 cases diagnosed premortem (Table 1). In 53 cases, the diagnosis was made at autopsy (Table 2). Noncardiac causes of death were present in 168 cases, 89 of which were diagnosed postmortem (Table 3) and 79 of which were due to death related to an anticipated outcome of an already known noncardiac disease process. These 79 cases were reviewed to ensure that death was neither sudden nor unexpected. The mean age of death for those who died of heart disease was 23.9±10.1 years and the mean age of death for those who died of noncardiac causes was 22.0±11.5 years (Figure 3).

Figure 2).

Age distribution of autopsy-positive sudden unexpected death for a cardiac cause or known pre-existing cardiac condition

TABLE 1.

Causes of death in individuals with known heart disease

| Cause of death | n |

|---|---|

| Congenital heart disease | 4 |

| Valvulopathy | 3 |

| Endocarditis | 2 |

| Hypertension | 1 |

| Cardiomyopathy | 1 |

| Intracardiac fibroma | 1 |

| Total | 12 |

TABLE 2.

Causes of death in autopsy-diagnosed cases of heart disease

| Cause of death | n |

|---|---|

| Ischemic heart disease | 12 |

| Myocarditis | 11 |

| Multiple diagnoses | 9 |

| Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy | 8 |

| Atherosclerotic disease associated with cocaine use | 4 |

| Arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy | 4 |

| Congenital heart disease | 2 |

| Myocardial fibrosis | 2 |

| Dilated cardiomyopathy | 1 |

| Total | 53 |

TABLE 3.

Causes of death in autopsy-diagnosed cases of noncardiac sudden unexpected death

| Cause of death | n |

|---|---|

| Neurological | 33 |

| Vascular | 17 |

| Respiratory | 15 |

| Multiple diagnoses | 8 |

| Infectious | 6 |

| Gastrointestinal | 6 |

| Cancer | 1 |

| Hepatic | 1 |

| Adrenal | 1 |

| Sarcoidosis related | 1 |

| Total | 89 |

Figure 3).

Age distribution of autopsy-positive sudden unexpected death for a noncardiac cause or known pre-existing noncardiac condition

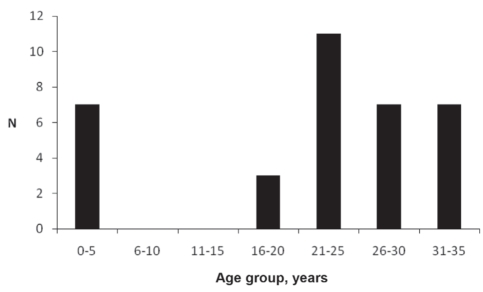

Autopsy-negative SUD

Review of the BCCS database determined that there were 35 cases in whom a thorough review and autopsy failed to identify a cause of death (Table 4). The mean age of death was 21.0±11.6 years (Figure 4). This group included three cases classified by the BCCS as ‘sudden unexplained death in infancy’.

TABLE 4.

Coroner designation of cause of death in autopsy-negative sudden unexpected death

| Designation | n |

|---|---|

| Undetermined cause of death | 17 |

| Presumed cardiac arrhythmia | 10 |

| Sudden unexpected death | 5 |

| Sudden unexpected death in infancy | 3 |

| Total | 35 |

Figure 4).

Age distribution of autopsy-negative sudden unexpected death

According to the coroners’ case records involving individuals 19 years of age or younger, 86% of autopsy-negative SUD cases had specimens saved and had a specialist consulted, and 71% of cases had a pediatric pathologist perform the autopsy. Samples of the brain were taken from four individuals, and samples of the brain and kidney were taken from two individuals. In total, six neuropathologists were consulted for three cases of SUD in infancy, two cases with an undetermined cause of death, and one case in which the cause of death was determined to be long-chain 3-hydroxyacyl-coenzyme A dehydrogenase deficiency. In cases of autopsy-positive SUD for which the cause of death was determined to be cardiac related, 58% had a pediatric pathologist perform the autopsy, had specimens saved and had a specialist consultation. Samples of the heart alone were taken in one case, samples of the brain alone were taken in two cases, samples of the heart and the brain were taken in three cases, and samples of muscle were taken in one case. In total, four cardiovascular pathologists, four neuropathologists and two additional pathologists were asked to consult on seven cases in which the cause of death was found to be myocarditis in two cases, cardiomyopathy in two cases and multiple heart conditions in three cases.

In the adult population, specimens were saved and a specialist was consulted in 14% of autopsy-negative SUD cases according to coroners’ case records. In total, samples of myocardium were taken from three individuals and samples of brain were taken from one individual. Three cardiovascular pathologists were consulted for two cases in which there was an undetermined cause of death and one case in which the cause of death was presumed to be cardiac arrhythmia. One neuropathologist was consulted for a case with an undetermined cause of death. In cases of autopsy-positive SUD in which the cause of death was determined to be cardiac related, specimens were saved at autopsy and a specialist was consulted in 5% of cases. Samples of the heart were collected, and one cardiovascular pathologist and one additional pathologist were consulted for one case in which the cause of death was found to be myocarditis, and another case in which the death was caused by complex congenital heart disease.

From the review of the coroner’s notes and autopsy records, a recommendation for relatives to see a health care professional regarding a possible genetic condition was made in 26% of undetermined SUD cases and 28% of cases in which the cause of death was determined postmortem to be heart disease.

Directed genetic testing

Three cases of SUD in which directed genetic testing was discussed in the coroner’s report were found. However, directed genetic testing for primary electrical disease was not performed in any of the undetermined or cardiac-related SUD cases from 2005 to 2007. In one case of cardiac-related SUD, the victim’s immediate family was referred to the medical genetics department for a genetic counselling session; however, there was no evidence that genetic testing for primary electrical diseases was performed on the victim. Testing was mentioned by the pathologist in three cases of undetermined SUD, but it is not clear whether this was completed.

A pathology perspective: Review of autopsy files from BC Children’s Hospital (Vancouver, BC)

Independent review of the information from autopsy records of all autopsies performed at BC Children’s Hospital (BCCH) from 2005 to 2007 identified 161 cases that were examined by pediatric pathologists and neuropathologists at BCCH for the BCCS. Of those cases, 60 were classified as unexpected deaths in infancy or childhood with no anatomic or toxicologic cause of death identified. Although not tabulated for the present review, some of the cases so classified had a history of co-sleeping. The age range of affected children was one day to 7.5 years, with an average age of 8.6 months. Excluding the four cases that were obvious age outliers (one each at age 7.5 years, seven years, five years four months, and one day), the average age of unexpected death was 4.9 months.

In all cases, the complete autopsy was performed by a pediatric pathologist, and the brain was examined by a pediatric neuropathologist. In all cases, tissue was kept frozen in the event that molecular genetic studies were required. Thus, more deaths were examined at BCCH than were recorded in the BCCS database. This discrepancy may be due to the possibility that cases diagnosed as unexpected death in infancy or childhood by a pediatric pathologist were classified differently by the BCCS, or that cases identified in the BCCH records had not yet undergone the BCCS review process and thus would not have been included in the database at the time of the present review. In addition, some files remain restricted and the present study’s data may, in fact, be an underestimation of the true number of undetermined SUD cases. There were instances in which a coroner determined a cause of death despite an undetermined cause of death by the pathologist. For the present study, the coroner’s assessment of the cause of death was used to determine the classification of SUD and it is possible that cases ruled to be undetermined SUD by the pathologist were actually classified as ‘autopsy-positive SUD’ or ‘known pre-existing condition’ in the present study. Nevertheless, this possible underestimation of undetermined SUD cases emphasizes the importance of integrating consistency in case identification and investigation, including molecular genetics, into postmortem investigations.

DISCUSSION

We undertook the present review to examine the areas in which it may be possible to make changes to improve the quality of care for surviving relatives of victims of SUD. We identified that SUD is rare in otherwise healthy young individuals, occurring in approximately 0.2% of natural deaths in BC. This figure is consistent with previously published rates (1). Although this does not represent a large group, the impact on the community and surviving family members is significant. Approximately 10% to 30% of sudden death cases in the young result in ‘negative’ autopsies in which no cause of death is found (13). A study by Tan et al (3) found that on further investigation of surviving family members, 71% of these unexplained SUD cases were attributed to primary electrical diseases. Tester and Ackerman (10) reported that 35% of SUDs were due to LQTS and CPVT. Primary electrical diseases are difficult to diagnose and are known as ‘silent’ diseases in individuals with structurally normal hearts who have no history of cardiac problems (7).

Finding a diagnosis for the victims of SUD requires a thorough history and systematic autopsy. Current autopsy practices in the US and Canada are variable. A study by Baker et al (14) of 418 US and Canadian institutions found a wide variability in what was reported in a final autopsy report, with 40% of institutions not recording basic patient demographic information. They also found that the turnaround time for autopsy cases exceeded the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations standard of 30 working days for routine cases and three months for difficult cases in 23.7% of autopsies. We appreciate that this is an unrealistic time frame in the current era, where ancillary testing may be required; however, the importance of determining whether first-degree relatives should be evaluated cannot be overstated.

In the present study, we identified 35 cases in which, after thorough investigation, an arrhythmic cause of death was probable. If one estimates that as many as one-third of these cases are due to heritable primary electrical disease (15), nearly a dozen families would realize potentially life-saving benefits from further evaluation.

Currently, based on our review of the BCCS in BC, it appears that there is no standardized approach to managing cases identified as SUD. There is currently no protocol within the BCCS to investigate the possibility of electrical cardiac disorders and other genetic conditions causing unexpected death. As a result, relevant information may not be available for the pathologist to review before performing the autopsy examination, and this could adversely influence the course of the postmortem examination. Although BCCH has retained tissue for further investigations, this cannot be readily determined from a review of the current BCCS files.

Relatives of victims are not consistently referred to medical professionals after a family member’s SUD. In our study, a recommendation to see a medical professional was made in 26% of autopsy-negative SUDs and 28% of SUDs in which the cause of death was determined postmortem to be heart disease. Although this finding may be an underestimate, the outcome is that the surviving relatives of victims of SUD are not necessarily provided with an explanation for the cause of death and other cases of SUD may not be prevented. We are involved in an ongoing research study that has already demonstrated that a systematic approach may uncover a diagnosis in a significant number of cases of SUD, where conventional methodology does not (16). Ontario recently adopted guidelines to standardize the approach to SUD in the young (17).

Consistent with the findings of the study by Rutberg et al (18), our study confirmed that genetic testing for primary electrical diseases is not routinely used for autopsy diagnosis and highlights the merits of using genetic testing in selected cases.

Limitations

The present study was a case review and the information was gathered retrospectively. One author (ZL) reviewed all the cases and consulted one of the co-authors (SS) for cases in which the definitions were not clear. In some cases, inferential reasoning was used to arrive at a cause of death, which may not have been the actual cause of death in some of these cases. There were insufficient data to establish a cause of death in 13 cases. The low incidence of families identified for referral for further medical testing may be the result of a failure of the pathologist to make a recommendation to the coroner about having family members tested or, alternatively, a failure of the coroner to follow through with the pathologist’s recommendations.

Future implications

These results are an impetus for the creation of a standardized protocol for the management of SUD cases in BC. We have embarked on this process and have already altered the referral process for families. This protocol will evolve to include the types of referrals and recommendations that should be made to the surviving relatives, and will streamline the testing and consultation process after autopsy examination, to ensure timely care of similarly affected family members.

CONCLUSION

Our study demonstrated that current methods of death classification by the BCCS are not suited for classifying rare diseases such as SUD due to primary electrical diseases. There was no use of directed genetic testing or consistent assessment of tissue. Referral to specialists for surviving relatives was inconsistent. Fortunately, it was evident in the present study that these deaths do occur at a low rate every year in BC. Provincial bodies should establish a standardized protocol for dealing with SUDs that includes molecular autopsy to ensure thoroughness of the diagnosis and optimization of the referral process for surviving relatives.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge Tej Sidhu, Norm Leibel, Dr Karla Pederson and the staff at the BC Chief Coroner’s Office for their contributions to the manuscript.

Footnotes

FUNDING: ZL received research funding from the Child and Family Research Institute, Children’s and Women’s Health Centre of BC, Vancouver, BC.

REFERENCES

- 1.Basso C, Corrado D, Thiene G. Cardiovascular causes of sudden death in young individuals including athletes. Cardiol Rev. 1999;7:127–35. doi: 10.1097/00045415-199905000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wedekind H, Schulze-Bahr E, Volker D, Breithardt G, Brinkmann B, Bajanowski T. Cardiac arrhythmias and sudden death in infancy: Implications for the medicolegal investigation. Int J Legal Med. 2007;121:245–57. doi: 10.1007/s00414-005-0069-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tan HL, Hofman N, van Langen IM, van der Wal AC, Wilde AA. Sudden unexplained death: Heritability and diagnostic yield of cardiological and genetic examination in surviving relatives. Circulation. 2005;112:207–13. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.522581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.di Gioia CR, Autore C, Romeo DM, et al. Sudden cardiac death in younger adults: Autopsy diagnosis as a tool for preventive medicine. Hum Pathol. 2006;37:794–801. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2006.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brugada R. Role of molecular biology in identifying individuals at risk for sudden cardiac death. Am J Cardiol. 2000;86:28K–33K. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(00)01289-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sanatani S, Wilson G, Smith C, Hamilton R, Williams W, Adatia I. Sudden unexpected death in children with heart disease. Congenit Heart Dis. 2006;1:89–97. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-0803.2006.00014.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wren C. Screening children with a family history of sudden cardiac death. Heart. 2006;92:1001–6. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2005.069757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Edwards WD. Molecular autopsy vs postmortem genetic testing. Mayo Clin Proc. 2005;80:1234–5. doi: 10.4065/80.9.1234-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rinaldo P, Yoon HR, Yu C, Raymond K, Tiozzo C, Giordano G. Sudden and unexpected neonatal death: A protocol for the postmortem diagnosis of fatty acid oxidation disorders. Semin Perinatol. 1999;23:204–10. doi: 10.1016/s0146-0005(99)80052-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tester DJ, Ackerman MJ. Postmortem long QT syndrome genetic testing for sudden unexplained death in the young. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;49:240–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tester DJ, Spoon DB, Valdivia HH, Makielski JC, Ackerman MJ. Targeted mutational analysis of the RyR2-encoded cardiac ryanodine receptor in sudden unexplained death: A molecular autopsy of 49 medical examiner/coroner’s cases. Mayo Clin Proc. 2004;79:1380–4. doi: 10.4065/79.11.1380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.PGx Health A Division of Clinical Data. Changing the rules for heart patients and their families: FAMILION (1999–2008). <http://www.pgxhealth.com/genetictests/familion/> (Version currrent at October 8, 2008).

- 13.Schwartz PJ, Crotti L. Can a message from the dead save lives? J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;49:247–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Baker PB, Zarbo RJ, Howanitz PJ. Quality assurance of autopsy face sheet reporting, final autopsy report turnaround time, and autopsy rates: A College of American Pathologists Q-Probes study of 10003 autopsies from 418 institutions. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1996;120:1003–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tester DJ, Ackerman MJ. The role of molecular autopsy in unexplained sudden cardiac death. Curr Opin Cardiol. 2006;21:166–72. doi: 10.1097/01.hco.0000221576.33501.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Krahn AD, Gollob M, Yee R, et al. Diagnosis of unexplained cardiac arrest: Role of adrenaline and procainamide infusion. Circulation. 2005;112:2228–34. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.552166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.University of Ottawa Heart Institute Ontario adopts Canada’s first cardiac autopsy guide for unexplained sudden death (July 29, 2008). <http://www.ottawaheart.ca/UOHI/doc/News_July29_2008.pdf/> (Version current at September 15, 2008).

- 18.Rutberg J, Green MS, Gow RM, et al. Molecular autopsy in the sudden cardiac death of a young woman: A first Canadian report. Can J Cardiol. 2007;23:904–6. doi: 10.1016/s0828-282x(07)70849-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]