Abstract

Objective

To compare the use and effect of a computer based information system for cancer patients that is personalised using each patient's medical record with a system providing only general information and with information provided in booklets.

Design

Randomised trial with three groups. Data collected at start of radiotherapy, one week later (when information provided), three weeks later, and three months later.

Participants

525 patients started radical radiotherapy; 438 completed follow up.

Interventions

Two groups were offered information via computer (personalised or general information, or both) with open access to computer thereafter; the third group was offered a selection of information booklets.

Outcomes

Patients' views and preferences, use of computer and information, and psychological status; doctors' perceptions; cost of interventions.

Results

More patients offered the personalised information said that they had learnt something new, thought the information was relevant, used the computer again, and showed their computer printouts to others. There were no major differences in doctors' perceptions of patients. More of the general computer group were anxious at three months. With an electronic patient record system, in the long run the personalised information system would cost no more than the general system. Full access to booklets cost twice as much as the general system.

Conclusions

Patients preferred computer systems that provided information from their medical records to systems that just provided general information. This has implications for the design and implementation of electronic patient record systems and reliance on general sources of patient information.

Introduction

Most cancer patients want as much information as possible and wish to be involved in treatment decisions.1–3 Some argue that tailoring information is important to meet patients' different backgrounds.4 Computer based methods can be used to tailor information to patients,5–10 but no major randomised trials have examined the outcome of tailoring information to cancer patients. The importance of the electronic patient record has been recognised in the NHS information strategy.11 If using medical records to tailor information for patients is worth while then it has implications for the design and implementation of electronic patient records and patients' use of computer based resources such as the internet.

Our primary aim in this study was to compare patients' use and satisfaction, doctors' perceptions, and the costs of a system providing information for patients that was personalised using the medical record with more general computer based information. Subsidiary aims were to compare the effect of providing such personalised information with that of providing conventional information booklets and to assess the impact of providing information on patients' psychological status. Although many information booklets are produced, in practice these are not freely available in hospitals; therefore, computer based information may provide a cost effective alternative. Too much technical information12,13 and, some argue, access to medical records14 may increase anxiety, whereas appropriate information may reduce it.15 We therefore measured these effects.

Participants and methods

Study population and sample

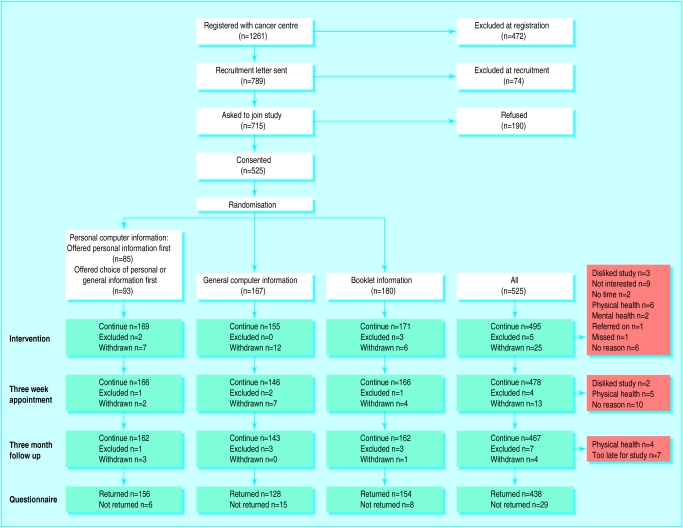

The Beatson Oncology Centre provides specialised non-surgical cancer treatment for patients throughout western Scotland. Between August 1996 and December 1997, 1261 eligible patients with breast, cervical, prostate, or laryngeal cancer were identified from radiotherapy booking sheets (fig 1). Patients receiving palliative treatment, with no knowledge of their diagnosis, with visual or mental handicap, or with severe pain or symptoms were excluded from the study. We obtained ethical approval for the study from the Western Ethics Committee.

Figure 1.

Flow of patients through trial

Recruitment and randomisation

Eligible patients were sent a letter describing the study and were contacted when they attended the centre, within three days of their starting treatment. At this contact, we gave further details of the study and assessed the patients' eligibility. We randomly allocated 525 patients who agreed to enter the study to one of three intervention groups. (For further details of recruitment and randomisation, see appendix 1 on the BMJ's website.)

Intervention groups

Computer based information

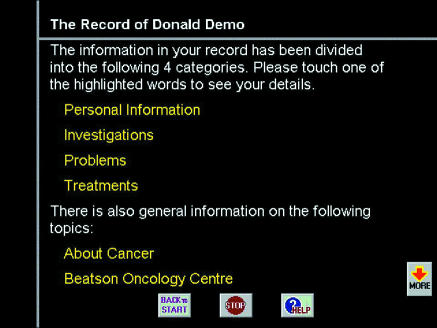

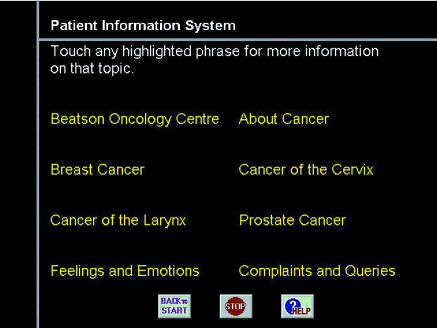

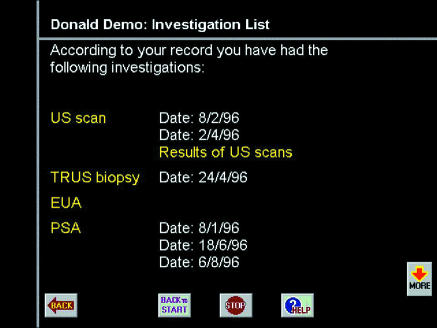

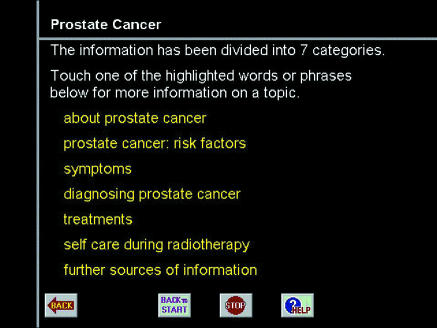

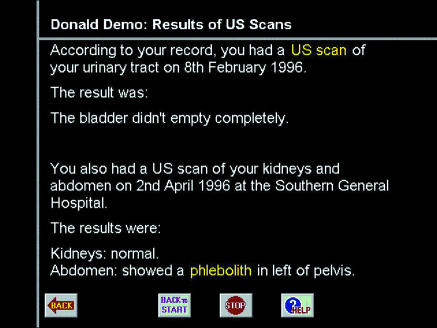

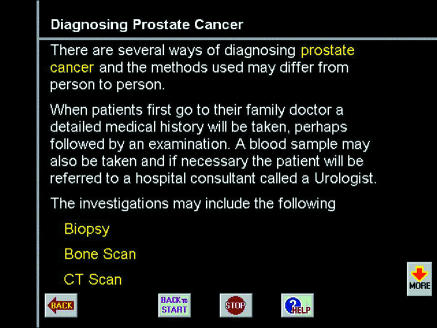

Two groups were offered a “computer consultation” using a touch screen computer (fig 2).

Figure 2.

Examples of data displayed by computer information systems

General information group—Patients were offered a system giving general information about cancer organised as a hypertext document.

Personal information group—Patients were offered a system that allowed them to see a summary of their medical record, and from there (via hypertext links) to information about all the concepts and terms mentioned in the record (such as “grade II” being linked to information about what this meant). Half of the personal group was also given access to the general system menu, so that we could measure more directly which system was preferred and used first.

Patients in both personal and general information groups were sent printouts of the information they had viewed. After the intervention, the patients had open access to the same information system via another computer sited in a waiting area.

Booklet information group

Patients were invited to look through a folder of printed booklets and to take as many as they wished. There were folders for each type of cancer containing 47, 32, 34, and 30 booklets for breast, cervical, prostate, and laryngeal cancers respectively.

(For further details of computer systems and booklets, see appendix 2 on the BMJ's website.)

Data collection

At recruitment or shortly after, patients were asked about the information they had already been given, what newspapers they read, their use of technology, and what information sources they used.16 They completed a hospital anxiety and depression scale17 and mental adjustment to cancer questionnaire.18

The intervention took place up to a week after recruitment. The computer systems automatically recorded the time patients spent using the computer and the choices they made, both at the time of their computer consultation and afterwards. For the booklet information group, we recorded the number and type of booklets chosen. Patients' views on the information were obtained from a home questionnaire after the intervention.

At their consultation with a doctor, three weeks after intervention, the patients completed a second hospital anxiety and depression scale and mental adjustment to cancer questionnaire. The doctors assessed the patient's participation, anxiety, knowledge, and time spent in consultation and compared these results with those of the “average” patient with that type of cancer.

Three months after the intervention, patients completed a third hospital anxiety and depression scale and mental adjustment to cancer questionnaire, and they were asked about their information preferences and their use of the printed material at home.

Data analysis

We assessed differences in patients' views, doctors' assessments, use of information, and cost of intervention using cross tabulations and χ2 tests. We assessed differences between intervention groups in scores on anxiety and depression scales and mental adjustment questionnaires using cross tabulations and χ2 tests, Student's t tests, and Mann-Whitney U tests.

In a subsidiary analysis using multiple logistic regression analysis, we examined differences in patients' anxiety and depression scores by their cancer type, time since diagnosis, age, sex, deprivation category,10 newspapers read, and use of information in the intervention.

Costs

We calculated current time costs in maintaining both computer information systems, using the cost of a research assistant's salary. We recorded the costs of the booklets taken by each patient. Capital computer costs were written off over four years, with maintenance charges of 5% for years 2-4. Costs incurred by patients were not included as the interventions took place during visits for treatment. We modelled four different scenarios and compared their four year cost profiles using a 6% discount rate.

Results

Patients completing the study

Of the 715 patients invited to participate, we recruited 525; 190 (27%) refused to take part (fig 1). Probability of refusal increased with age. Of the 525 patients recruited, 467 continued to the three month follow up and 438 of these returned questionnaires. The 87 who did not complete follow up were more likely to be in the general computer information group (23% v 13%, χ2=8.1 (1 df), P=0.004), to not have breast cancer (20% v 14%, χ2=3.83 (1 df), P=0.05), live in poorer areas (deprivation categories 4-7, 20% v 11%, χ2=8.3 (1 df), P=0.004), and to have had a diagnosis of cancer for more than a year (40% v 15%, χ2=12.9 (1 df), P<0.001). There was no difference by age, sex, or newspapers read. A further 47 patients returned an incomplete hospital anxiety and depression scale at three weeks or three months and were not included in the analyses of anxiety and depression scales and mental adjustment questionnaires.

Use of computer

The average time spent using the computer at intervention was 12 minutes (range 1-44). Of those patients in the personal information group who were offered both personal and general information systems, two thirds (57/88) chose the personal information first. Twenty nine per cent of the patients used the computer again. Patients in the personal information group were more likely than those in the general information group to use the computer between the three week and three month follow ups (20/169 v 4/155, χ2=12 (2 df), P=0.002).

Patients' views and preferences

Patients given personal information were more likely to have a high satisfaction score, calculated from seven attributes (table 1), than were those given general computer information (mean difference 12%, 95% confidence interval 0.7% to 23.9%). More patients given personal information thought that the information was relevant and that they had learnt something new.

Table 1.

Cancer patients' responses to questionnaires sent a few days after they were given information about cancer and after three months' follow up. Values are number (percentage) of affirmative answers to each question unless stated otherwise

| Question asked | Computer information

|

Booklet information (n=150)* | Total (n=434)* | P value of difference†

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Personal (n=156)* | General (n=128)* | Personal v general computer information | Computer v booklet information | |||

| After intervention | ||||||

| 1 Was the information useful? | 103 (67) | 76 (60) | 98 (65) | 277 (64) | 0.25 | 0.77 |

| 2 Did it tell you anything new? | 96 (62) | 63 (50) | 74 (49) | 233 (54) | 0.03 (personal better) | 0.13 |

| 3 Was information relevant? | 123 (79) | 85 (66) | 105 (70) | 313 (72) | 0.02 (personal better) | 0.47 |

| 4 Did you find information easily? | 132 (85) | 109 (85) | 117 (79) | 358 (83) | 0.67 | 0.07 |

| 5 Did you feel overwhelmed with information? | 33 (21) | 37 (29) | 66 (44) | 136 (31) | 0.15 | <0.001 (booklet worse) |

| 6 Was it too technical? | 13 (8) | 18 (14) | 17 (11) | 48 (11) | 0.13 | 0.90 |

| 7 Was it too limited? | 76 (49) | 71 (56) | 48 (32) | 195 (45) | 0.22 | <0.001 (computer worse) |

| Satisfaction score >2‡: | ||||||

| No (%) of patients | 68 (46) | 41 (34) | 58 (40) | 167 (40) | 0.04 (personal better) | 0.77 |

| 95% CI of percentage | 38 to 54 | 26 to 42 | 32 to 48 | |||

| At 3 months | ||||||

| 8 Prefer computer to 10 minute consultation with professional? | 38/131 (29) | 22/110 (20) | 12/122 (10) | 72/363 (20) | 0.12 | <0.001 (computer more likely) |

Answers given on four or five point scales were recoded as binary responses, with the modal category used as the point of division.

Individual questions had up to five missing responses: in these cases the denominator used to calculate percentages was smaller than value given.

From χ2 (1 df).

Summation of scores from questions 1-7. Questions 1-4 are “positive” attributes, and affirmative response to each question adds 1 to satisfaction score. Questions 5-7 are “negative,” and affirmative response to each question subtracts 1 from satisfaction score. Score ranged from −3 to 4.

The patients who received booklet information were more likely to feel overwhelmed with information than were those given computer information, while patients in the computer information groups were more likely to think that the information provided was limited.

At three months' follow up, although 80% of patients expressed a preference for 10 minutes with a specialist nurse or radiographer to computer or booklet information, 20% preferred unlimited time with a computer, and those in the computer groups were more likely to do so.

Doctors' assessment

Doctors thought more patients (35%) in the general computer information group were above average in knowledge compared with both the personal information group (25%) and booklet information group (20%) (P=0.01). They perceived no other difference.

Use of printed material at home

More of the patients offered booklet information (83%) used the material at home compared with those offered personal information (70%) or general information (57%) (χ2=22.4 (2 df), P<0.001). More patients in the personal information group showed the computer printouts to family or friends (36%) compared with those with general information (22%) or with booklets (21%) (χ2=6.7 (2 df), P=0.035).

Costs

In the absence of an electronic patient record, the personalised computer information system requires manual extraction of data from patients' case records and would currently cost over nine times the cost of the general information system. With the introduction of an electronic patient record, however, it would cost the same as the general system over time as fewer additions would be required.

Despite our buying the booklets at a discount, the average cost of booklets taken was over £7 per patient. A general computer information system would cost 40% of the costs of full access to booklets; even in the first year it would cost less. (For further details of costing, see appendix 3 on the BMJ's website.)

Psychological status

There were no significant changes in the patients' depression scores or mental adjustment scores between the start of treatment and follow up at three weeks and three months. However, 327 (84%) of the patients showed improvement in anxiety scores, of whom 255 (65%) improved in the first three weeks. At three months, 37% of patients in the general computer information group were still anxious compared with only 19% in the personal information group (mean difference 18%, 95% confidence interval 3.7% to 26.5%) (table 2). Exploration of other predictors by multiple logistic regression showed that type of cancer, age, sex, and type of newspaper read were all predictors of anxiety, but type of intervention remained a significant predictor with more patients in the general computer information group being anxious. (See appendix 4 on the BMJ's website for details of the intention to treat analysis).

Table 2.

Percentages of 391 cancer patients completing all three hospital anxiety and depression scales who displayed anxiety or borderline anxiety. Adjusted P values are shown from multiple logistic regression

| Hospital anxiety and depression scale

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| At start of treatment | At 3 weeks | At 3 months | |

| Intervention groups | |||

| Personal computer information | 38 | 23 | 19 |

| General computer information | 37 | 28 | 37 |

| Booklet information | 32 | 18 | 22 |

| P value of difference | >0.05 | >0.05 | 0.001 |

| Baseline characteristics | |||

| Age (years): | |||

| <60 | 48 | 33 | 35 |

| ⩾60 | 22 | 11 | 15 |

| P value of difference | 0.0006 | 0.006 | 0.005 |

| Time since cancer diagnosed (months): | |||

| <4 | 35 | 20 | 23 |

| 4-12 | 37 | 26 | 29 |

| >12 | 27 | 13 | 20 |

| P value of difference | >0.05 | >0.05 | >0.05 |

| Sex: | |||

| Female | 44 | 30 | 32 |

| Male | 20 | 9 | 14 |

| P value of difference | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.002 |

| Type of cancer: | |||

| Breast | 43 | 29 | 31 |

| Other | 25 | 13 | 18 |

| P value of difference | >0.05 | >0.05 | 0.03 |

| Deprivation category: | |||

| Deprived | 37 | 30 | 30 |

| Average | 38 | 23 | 27 |

| Affluent | 28 | 16 | 21 |

| P value of difference | >0.05 | >0.05 | >0.05 |

| Newspaper read: | |||

| Tabloid | 40 | 27 | 30 |

| Broadsheet | 29 | 16 | 18 |

| P value of difference | >0.05 | 0.01 | 0.003 |

| Intervention behaviour | |||

| Information seeker*: | |||

| No | 37 | 24 | 27 |

| Yes | 35 | 21 | 26 |

| P value of difference | >0.05 | >0.05 | >0.05 |

| User of information at home: | |||

| No | 41 | 32 | 36 |

| Yes | 34 | 19 | 23 |

| P value of difference | >0.05 | >0.05 | >0.05 |

Defined as the top third for each group: those who spent ⩾18 minutes on the computer (total time) and those in booklet information group who chose 8 or more booklets.

Discussion

Recruitment and follow up

The validity of our results is affected by patients' declining to take part in the study, many of whom may not have wanted more information. More patients in the general computer group failed to complete the three month follow up. It may be that use of the personal rather than general computer information helped to retain the patients' interest, but the evidence is inconclusive.

Personalised v general computer systems

The NHS information strategy11 emphasises the importance of electronic patient record systems for clinical information but suggests the internet for patient information. Although most patients in this study preferred more time with a professional to computer or booklet information, one in five did not, and for all patients a computer could provide complementary information. However, the patients preferred the personalised information system to the general one and were more likely to use both computer and printout.

There was little difference in doctors' perceptions of the intervention groups. All the doctors at the Beatson Oncology Centre were willing collaborators in this study, and few clinicians now object to controlled patient access to medical records. Other reasons for combining patient information with electronic patient records include patients' audit of records14 and easier maintenance of integrated health service systems.19 Routine use by patients should be built into electronic patient records as they are implemented over the next few years.

Computers systems v booklets

Written information is important.20,21 More of the patients offered booklet information used the material at home than did those given computer printouts, but the patients given personal computer information were more likely to use printouts than those given general computer information and were most likely to show their information to others. The printed booklets were more attractive than computer printouts, although these could be improved. Printed booklets are expensive, and tailored computer printouts could be produced more cheaply.

More of the patients offered booklets felt overwhelmed by the amount of information available, possibly because of the large number of booklets from which to choose. Providing a more restricted set of booklets, or nurse guidance in their selection, might have produced different results.

It is unclear why more patients in the computer groups thought that the information given was limited. The information presented was more complex than in other local systems.22–24 However, the patients received printouts only of the material they inspected during the computer session, so they did not have additional information to work through at home, as the booklet group did. Furthermore, the patients spent a relatively short time using the computer and may not have realised the depth of information available.

Improvement in anxiety

We did not directly try to reduce anxiety but measured it in case giving patients access to their medical records increased anxiety.14 Our results suggest the converse. There was some evidence that the patients given general computer information were more anxious than other patients at three months. Although we did not collect information on physical health to which anxiety might be related25,26 and doubts have been expressed about the use of the hospital anxiety and depression scale among cancer patients,27 we think that the observed difference in anxiety at three months is most likely explained by the interventions. As more patients given personal information used their printouts with their family, we could hypothesise that this contributed to the difference.

What is already known on this topic

Various studies have examined different ways of “personalising” computer based information for patients

There has been no randomised trial testing the assumption that personalisation using the medical record is worth while

What this paper adds

This randomised trial showed that cancer patients thought a system giving them information based on their medical record was better than one giving only general information

Patients were more likely to use the personal system again and to show the printouts from that system to their family

There were no major differences in doctors' perceptions of the patients, but patients using the general information system seemed more anxious at three months' follow up

The study has implications for the design and implementation of electronic patient record systems and of patient information systems

Others have found that general information given after a consultation can inhibit patients' recall of the consultation28 and that patients used audiotaped consultations to inform their family of their situation.29 Whether providing patients with information helps to reduce their anxiety may depend on their coping style30–32 and warrants further study. Finding information on the internet can be difficult, and more thought is needed about its role as a primary information source for patients.

(See appendix 5 on the BMJ's website for a discussion of the feasibility of our computer system and of alternative computer based forms of patient information.)

Conclusions

This study strongly suggests that patient information should be linked to electronic patient records. Patient information booklets are expensive, and computer based information could prove cheaper. However, further study is needed of how information, particularly from general sources, affects anxiety.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the consultants (particularly Nick Reed and Tim Habeshaw, who were directors of the Beatson Oncology Centre during the study), other medical staff, cancer nurse specialists, radiographers, medical records staff, and other staff at the Beatson Oncology Centre for their collaboration with this project; the patients who took part in the study; Lynn Naven, who worked as a locum for SMcG during three months' sick leave; Ed Carter; Ross Morton and Keith Murray, who helped with various aspects of computing; Charles Gillis and Cathy Meredith, who advised on research design; Sally Tweddle, who made available unpublished protocols and papers; and colleagues in the University of Glasgow and the Beatson Oncology Centre who commented on the manuscript.

Footnotes

Funding: Scottish Office Home and Health Department grant number K/OPR/2/2/D248. The views expressed in this paper are those of the authors and do not represent the views of the Scottish Office.

Competing interests: None declared.

website extra: Further details of the trial and its implications appear on the BMJ's website www.bmj.com

References

- 1.National Cancer Alliance. Patient-centred cancer services? What patients say. Oxford: National Cancer Alliance; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fallowfield L, Ford S, Lewis S. No news is not good news: information preferences of patients with cancer. Psycho-Oncology. 1995;4:197–202. doi: 10.1002/pon.2960040305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Meredith C, Symonds P, Webster L, Lamont D, Pyper E, Gillis CR, et al. Information needs of cancer patients in west Scotland: cross sectional survey of patients' views. BMJ. 1996;313:724–726. doi: 10.1136/bmj.313.7059.724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Harris KA. The informational needs of patients with cancer and their families. Cancer Pract. 1998;6:39–46. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-5394.1998.1998006039.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bental DS, Cawsey AJ, Jones R. Patient information systems that tailor to the individual. Patient Educ Counsel. 1999;36:171–180. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(98)00133-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Osman L, Abdalla M, Beattie J, Ross S, Russell I, Friend J, et al. Reducing hospital admissions through computer supported education for asthma patients. BMJ. 1994;308:568–571. doi: 10.1136/bmj.308.6928.568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marshall W, Rothberger L, Bunnell S. The efficacy of personalised audiovisual patient-education materials. J Fam Pract. 1984;19:659–663. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Buchanan B, Moore J, Forsythe D, Carenini G, Ohlsson S, Banks G. An intelligent interactive system for delivering individualized information to patients. Artif Intell Med. 1995;7:117–154. doi: 10.1016/0933-3657(94)00029-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hirst G, DiMarco C, Hovy E. Authoring and generating health-education documents that are tailored to the needs of the individual patient. In: Jameson A, Paris C, Tasso C, editors. Proceedings of the sixth international conference on user modelling. New York: Springer Wien; 1997. pp. 107–118. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kreuter MW, Strecher VJ. Do tailored behavior change messages enhance the effectiveness of health risk appraisal? Results from a randomized trial. Health Educ Res. 1996;11:97–105. doi: 10.1093/her/11.1.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Department of Health. NHS information for health. London: DoH; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hathaway D. Effect of preoperative instruction on postoperative outcomes: a meta-analysis. Nurs Res. 1986;35:269–275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schwartz LP, Brenner ZR. Critical care unit transfer: reducing patient stress through nursing interventions. Heart Lung. 1979;8:540–547. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gilhooly MLM, McGhee SM. Medical records: practicalities and principles of patient possession. J Med Ethics. 1991;17:138–143. doi: 10.1136/jme.17.3.138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hinds C, Streater A, Mood D. Functions and preferred methods of receiving information related to radiotherapy. Cancer Nurs. 1995;18:374–383. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jones RB, Pearson J, McGregor S, Cawsey A, Barrett A, Gilmour H, et al. Cross sectional survey of patients' satisfaction with information about cancer. BMJ. 1999;319:1247–1248. doi: 10.1136/bmj.319.7219.1247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983;67:361–370. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1983.tb09716.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Watson M, Greer S, Young J, Inayat Q, Burgess C, Robertson B. Development of a questionnaire measure of adjustment to cancer: the MAC scale. Psychol Med. 1988;18:203–209. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700002026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jones RB, Knill-Jones RP. Electronic patient record project: direct patient input to the record. Report for the Strategy Division of the Information Management Group of the NHS ME. Glasgow: University of Glasgow; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Glimelius B, Birgegrd G, Hoffman K, Kvale G, Sjoden P. Information to and communication with cancer patients: improvements and psychological correlates in a comprehensive care program for patients and their relatives. Patient Educ Counsel. 1995;25:171–182. doi: 10.1016/0738-3991(94)00655-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Luker KA, Beaver K, Leinster SJ, Owens RG. Information needs and sources of information for women with breast cancer: a follow-up study. J Adv Nurs. 1996;23:487–495. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.1996.tb00010.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jones RB, Navin LM, Murray KJ. Use of a community-based touch-screen public-access health information system. Health Bull. 1993;51:34–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McGarry E, Jones R, Cowan B, White J. A multimedia system for personalised treatment of anxiety in primary care. In: Richards B, editor. Current perspectives in healthcare computing. Weybridge: BJHC Books; 1998. pp. 277–285. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Morton AR, Patterson L, Jones R, Atkinson JM, Coia D. Personalised patient information for patients with schizophrenia living in the community. In: Richards B, editor. Current perspectives in healthcare computing. Weybridge: BJHC Books; 1998. pp. 94–104. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bailey AJ, Parmar MKB, Stephens RJ.for the CHART Steering Committee. Patient-reported short-term and long-term physical and psychologic symptoms: results of the continuous hyperfractionated accelerated radiotherapy (CHART) randomised trial in non-small-cell lung cancer J Clin Oncol 1998163082–3093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rapoport Y, Kreitler S, Chaitchik S, Algor R, Weissler K. Psychosocial problems in head-and-neck cancer patients and their change with time since diagnosis. Ann Oncol. 1993;4:69–73. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.annonc.a058365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hall A, A'Hern R, Fallowfield L. Are we using appropriate self-report questionnaires for detecting anxiety and depression in women with early breast cancer? Eur J Cancer. 1999;35:79–85. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(98)00308-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dunn SM, Butow PN, Tattersall MHN, Jones QI, Sheldon JS, Taylor JJ, et al. General information tapes inhibit recall of the cancer consultation. J Clin Oncol. 1993;11:2279–2285. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1993.11.11.2279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tattersall MHN, Butow PN, Griffin AM, Dunn SM. The take home message: patients prefer consultation audiotapes to summary letters. J Clin Oncol. 1994;12:1305–1311. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1994.12.6.1305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Miller SM. Monitoring versus blunting styles of coping with cancer influence the information patients want and need about their disease: implications for cancer screening and management. Cancer. 1995;76:167–177. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19950715)76:2<167::aid-cncr2820760203>3.0.co;2-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Street RL, Jr, Voigt B, Geyer C, Jr, Manning T, Swanson GP. Increasing patient involvement in choosing treatment for early breast cancer. Cancer. 1995;76:2275–2285. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19951201)76:11<2275::aid-cncr2820761115>3.0.co;2-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McHugh P, Lewis S, Ford S, Newlands E, Rustin G, Coombes C, et al. The efficacy of audiotapes in promoting psychological well-being in cancer patients: a randomised, controlled trial. Br J Cancer. 1995;71:388–392. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1995.79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.