Abstract

Background and objectives: We studied the relationship between microinflammation and endothelial damage in chronic kidney disease (CKD) patients on different dialysis modalities.

Design, setting, participants, & measurements: Four groups of CKD stage 5 patients were studied: 1) 14 nondialysis CKD patients (CKD-NonD); 2) 15 hemodialysis patients (HD); 3) 12 peritoneal dialysis patients with residual renal function >1 ml/min (PD-RRF >1); and 4) 13 peritoneal dialysis patients with residual renal function ≤1 ml/min (PD-RRF ≤1). Ten healthy subjects served as controls. CD14+CD16+ cells and apoptotic endothelial microparticles (EMPs) were measured by flow cytometry. Serum vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) was measured by ELISA.

Results: CKD-NonD and HD patients had a higher percentage of CD14+CD16+ monocytes than PD groups and controls. CD14+CD16+ was similar in the PD groups, regardless of their RRF, and controls. The four uremic groups displayed a marked increase in apoptotic EMPs and VEGF compared with controls. Apoptotic EMPs and VEGF were significantly higher in HD patients than in CKD-NonD and both PD groups. However, there were no significant differences between CKD-NonD and the two PD groups. There was a correlation between CD14+CD16+ and endothelial damage in CKD-NonD and HD patients, but not in PD and controls.

Conclusions: There was an increase in CD14+CD16+ only in CKD-NonD and HD patients. In these patients, there was a relationship between increased CD14+CD16+ and endothelial damage. These results strongly suggest that other factors unrelated to the microinflammatory status mediated by CD14+CD16+ are promoting the endothelial damage in PD, regardless of their RRF.

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) patients have a higher rate of mortality than the general population, which has been attributed to a higher rate of cardiovascular mortality (1–3). Several studies have also reported a strong association between endothelial damage and chronic inflammation in CKD patients (4–7).

The percentage of proinflammatory blood monocytes with the CD14+CD16+ phenotype is higher in hemodialysis (HD) patients (8,9), suggesting that these cells play an important role in the chronic inflammatory disease associated with uremia. CD14+CD16+ cells have been described as a subset of human peripheral monocytes that are phenotypically more differentiated than CD14++ and produce proinflammatory cytokines, such as TNF and IL-6 (10,11). In addition, a higher percentage of CD14+CD16+ monocytes is correlated with endothelial damage in CKD patients (12) and, interestingly, the high levels of CD14+CD16+ also predicted the appearance of cardiovascular disease.

Recently, we reported that a decrease in the percentage of proinflammatory CD14+CD16+ cells in uremic patients was associated with a greater clearance of large uremic toxins. In fact, we have demonstrated that on-line hemodiafiltration with a high convective transport reduced the percentage of proinflammatory CD14+CD16+ cells in comparison with high-flux HD (13). Furthermore, we have also observed that higher levels of CD14+CD16+ in CKD patients were correlated with high plasma levels of endothelial microparticles, an early feature of endothelial damage (14).

The aim of the present study was to evaluate the effects of different dialysis modalities on microinflammation as assessed by the percentage of CD14+CD16+ monocytes and endothelial damage associated with the CKD.

Materials and Methods

Human Subjects

Four different groups of CKD stage 5 patients were evaluated: nondialysis CKD patients (CKD-NonD); hemodialysis (HD); peritoneal dialysis patients with residual renal function >1 ml/min (PD-RRF >1); and peritoneal dialysis patients with residual renal function ≤1 ml/min (PD-RRF ≤1). The CKD-NonD group included 14 subjects just before the initiation of chronic dialysis therapy. Their mean age was 67.7 years (range: 39 to 78 years), and mean renal creatinine clearance was 8.5 ± 2.7 ml/min. The HD group included 15 patients with a mean age of 61.3 years (range: 33 to 77 years) and an average time on HD of 49.1 ± 33.2 months (range: 14 to 122 months). The patients were dialyzed three times a week with a high-flux polysulfone membrane (HF80S; Fresenius Medical Care, Bad Homburg, Germany). Bicarbonate dialysate solutions were used in all treatments, the blood flow rate was 300 to 400 ml/min, and the duration of dialysis was individually adjusted to maintain an eKt/V above 1.2. All patients were dialyzed in the same dialysis unit using the same dialysate system. All patients were dialyzed through a native arteriovenous fistula. Blood samples were obtained just before starting the first HD session of the week. The dialysate revealed concentrations of bacterial and endotoxin contamination below the detection limit (100 colony-forming units/ml and <0.25 endotoxin units).

To analyze the influence of RRF, we divided the PD patients into two groups, according to whether their RRF was above or below 1 ml/min. RRF was measured within 2 months of initiation of the study. The PD-RRF >1 group consisted of 12 stable patients (10 patients in continuous ambulatory PD and two with automated PD), with a mean age of 67 years (range: 45 to 76 years) and average time on dialysis of 28.5 ± 23.7 months (range: 7 to 83 months). The RRF in this group was 5 ± 2.6 ml/min (range: 2.2 to 10.5 ml/min). The PD-RRF ≤1 group included 13 stable patients with a mean age of 58.7 years (range: 29 to 79 years) and average time on dialysis of 52.1 ± 36.4 months (range: 17 to 70 months). The RRF was 0.1 ± 0.2 ml/min (range: 0 to 0.6 ml/min). Both PD groups received an individual PD prescription sufficient to maintain a weekly Kt/V above 1.9. Criteria for patient selection included the absence of inflammatory disease, acute or chronic infection, autoimmune disease, hepatic insufficiency, diabetes, malignancy and, in the case of PD patients, a peritonitis-free period of at least 3 months. The patients were not on anti-inflammatory or immune-suppressive drugs. Ten healthy volunteers, matched by age (63.9 ± 7.2 years) and gender (six women and four men) were used as controls. Informed consent was obtained from all patients after institutional approval.

Blood Chemistry

All samples were obtained in lithium heparin tubes and biochemistry tubes. RRF was calculated as an average of the creatinine and urea clearances by 24-h urine, corrected for body surface area. Hemoglobin levels were measured with an automated analyzer (Abbott Cell-Dyn 4000; Abbott Laboratories, Abbott Park, IL). High-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hsCRP) levels were determined by immunoturbidimetry; the reagents were supplied by Abbott Laboratories (Abbott Park, IL). The normal range of hsCRP was <5 mg/L. The concentrations of TNF-α and IL-6 were measured using a commercial sandwich ELISA with a sensitivity of 1 pg/ml (R&D Systems Europe). The analysis was performed using a microplate ELISA reader (Power Wave XS; Biotek) at 450 nm, and results are expressed as pg/ml.

Determination of CD14 and CD16 Mononuclear Phenotype Expression in Peripheral Blood

Blood was incubated with the mAbs M5E2 against the molecule CD14 conjugated with peridinin chlorophyll protein (PerCP), and 3G8 against the molecule CD16 conjugated with FITC. Both antibodies and the appropriate isotype controls were provided by Becton Dickinson (San Jose, CA). Flow cytometric analysis was performed with a FACScalibur flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson). Absolute CD14+CD16+ monocyte numbers were obtained using BD TruCount Tubes (Becton Dickinson). To calculate the medium fluorescence intensity (MFI) of the receptors, the flow cytometer was calibrated with BD Calibrite 3 beads (Becton Dickinson) to adjust set fluorescence compensation.

Analysis of Serum Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor Protein by ELISA

The level of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) protein in patient serum was analyzed by ELISA using the Quantikine VEGF ELISA Kit (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN). The samples were measured using a Power Wave XS microplate reader (Biotek, VT) set to 450 nm.

Determination of CD31+/Annexin V+ Endothelial Microparticles in Plasma

Apoptotic endothelial microparticles (EMPs) were isolated as described earlier (15). Plasma derived from 20 ml of citrate-buffered blood was separated from whole blood and immediately centrifuged at 13,000 × g for 5 minutes. Plasma was incubated with monoclonal antibody against phycoerythrin-labeled anti-CD31 antibody (Caltag Laboratories, Burlingame, CA), followed by incubation with FITC-conjugated Annexin V kits according to the manufacturer′s instructions (Bender MedSystem, Vienna, Austria). The negative control (zero value) was obtained using the isotype antibodies. Flow Count Calibrator beads (Beckman Coulter, Marseille, France) were added. Analysis was performed in a Coulter Cytomic FC 500 flow cytometer (Beckman Coulter) with CXP software (Beckman Coulter). Each result (one single value) was the average of three independent determinations of the same sample.

Statistical Analysis

Results are expressed as mean ± SD. Means from different patient groups were compared by repeated-measures ANOVA followed by the Bonferroni test. A t test for nonpaired data was used. The Spearman rank correlation coefficient was used to analyze the correlations. Differences were considered to be significant when P < 0.05.

Results

Basic Characteristics

Demographic and laboratory parameters of patients and controls are shown in Table 1. There were no differences between the groups with respect to age, sex, leukocytes, and hemoglobin. There were differences between PD-RRF >1, HD, and PD-RRF ≤1 with respect to dialysis vintage and RRF (P < 0.05). There was a statistical difference between PD-RRF ≤1 and controls with respect to serum albumin levels (P = 0.045). The inflammatory parameters, hsCRP, IL-6, and TNF-α, were higher in uremic patients than controls (P < 0.005). TNF-α concentration was markedly elevated in HD patients in comparison with CKD-NonD, PD-RRF >1, and PD-RRF ≤1.

Table 1.

Main demographic characteristics and biochemical parameters of patients evaluated and controls

| Controls (n = 10) | CKD-NonD (n = 14) | HD (n = 15) | PD-RRF >1 (n = 12) | PD-RRF ≤1 (n = 13) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, yr, mean (min to max) | 63.9 (56 to 71) | 67.7 (39 to 78) | 61.3 (33 to 77) | 67 (45 to 76) | 58.7 (29 to 70) |

| Gender, male/female | 4/6 | 7/7 | 4/11 | 5/7 | 7/6 |

| Dialysis vintage, mo, means ± SD | — | — | 49.1 ± 33.2 | 28.5 ± 23.7a | 52.1 ± 36.4 |

| Residual renal function, ml/min, mean ± SD | — | — | 0 | 5 ± 2.6a | 0.1 ± 0.2 |

| Leukocytes, mean (min to max) | 8123 (5109 to 10,900) | 8142.7 (4520 to 10,700) | 7566.6 (4910 to 11,160) | 8256 (5206 to 11,055) | 8066 (5113 to 10,500) |

| Hemoglobin, g/dl, mean (min to max) | 12.2 (11.4 to 13.3) | 12.4 (11.3 to 13.5) | 11.6 (10.4 to 12.9) | 12.1 (10.8 to 13.4) | 11.9 (10.6 to 13.2) |

| Serum albumin, g/dl, means ± SD | 4.2 ± 0.6 | 3.8 ± 1.5 | 4.1 ± 0.2 | 3.9 ± 0.3 | 3.7 ± 0.5b |

| hsCRP, mg/L, median (min to max) | 0.9 (0.3 to 1.5) | 1.9 (0.5 to 4.7)c | 2 (0.7 to 9.1)c | 2.8 (0.2 to 10.7)c | 3.9 (0.2 to 5.6)c |

| Plasma TNF, pg/ml mean (min to max) | 3.5 (0 to 7) | 32.6 (14.3 to 42.5)cd | 41.9 (33.2 to 56.5)c | 28.7 (15.1 to 41.6)cd | 31.6 (18.7 to 45.9)cd |

| Plasma IL-6, pg/ml, mean (min to max) | 1.6 (0 to 2.3) | 14.3 (5.3 to 18.1)c | 18.9 (10.6 to 27.8)c | 14.1 (7.5 to 20.6)c | 16.2 (8.1 to 20.4)c |

| Cardiovascular disease, n (%) | 0 | 2 (14.3) | 5 (33.3) | 3 (25) | 3 (23.1) |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 0 | 9 (64.3) | 9 (60) | 9 (75) | 8 (61.5) |

| Use of statin, n (%) | 0 | 5 (35.7) | 11 (73.3) | 8 (66.6) | 7 (53.8) |

| Use of vitamin D, n (%) | 0 | 3 (21.4) | 8 (53.3) | 5 (41.6) | 6 (46.2) |

min, minimum; max, maximum.

P < 0.05 versus HD and PD-RRF ≤1.

P < 0.05 versus controls and HD.

P < 0.05 versus controls.

P < 0.05 versus HD.

Distribution of CD14+CD16+ Monocytes in Healthy Subjects and Patients

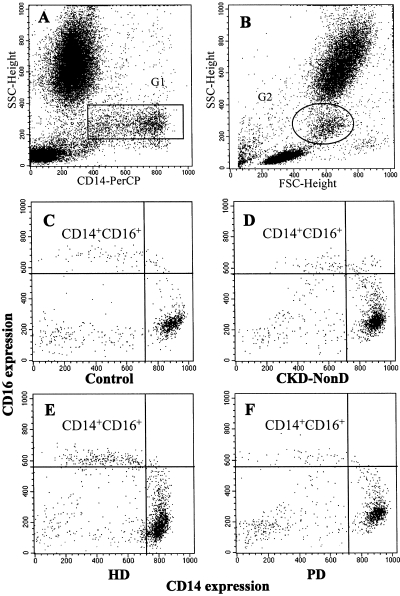

Figure 1 shows a representative study of the distribution of the subpopulations of monocytes in the peripheral blood of healthy subjects and CKD patients, as measured by flow cytometry. Monocyte population (G1) was defined using an SSC-Height/CD14-PerCP dot plot (Figure 1A) and backgated (G2) within the forward scatter-height (FCS-Height)/side scatter-height (SSC-height) (Figure 1B). Subsequently, CD14+CD16+ monocytes in the G2 population were assessed using a CD16-FITC/CD14-PerCP dot plot. A representative study is shown in Figure 1, C, D, E, and F.

Figure 1.

Representative flow cytometry analysis. (A) CD14 monocytes (G1) were assessed using an SSC-Height/CD14-PerCP dot plot and backgated (G2) within the FCS-Height/SSC-Height (B). Subsequently, CD14+CD16+ monocytes within the G2 population were assessed using CD16-FITC/CD14-PerCP dot plot (C, D, E, F). Representative histograms of CD14+CD16+ expression in different CKD patients and a healthy subject (C, D, E, F). The region represents CD14+CD16+ monocytes from controls, chronic kidney disease patients (CKD-NonD), hemodialysis patients (HD), and peritoneal dialysis patients (PD).

In all of our subjects, we observed at least two subpopulations of monocytes according to the expression density of the CD14 and CD16 receptors. In healthy subjects, most of the monocytes (82.5% ± 4.6%) presented an elevated expression of the CD14 receptor (MFI: 820 ± 51) and did not express CD16 (MFI: 72 ± 45) (monocytes CD14++CD16−). The second subpopulation (monocytes CD14+CD16+) represented, in healthy subjects, only 3.9% ± 1.1% of the peripheral blood monocytes and is characterized by its expression of CD14 at a lower fluorescence intensity (MFI: 455 ± 66) as well as being a coexpresser of the CD16 receptor (MFI: 551 ± 96). The expression of CD14 and CD16 receptors in the different patient groups is summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Expression density (MFI) of CD14 and CD16 in the monocyte subsets in the different patient groups

| Expression Density of CD14 and CD16 |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD14+CD16+ Subset |

CD14++CD16− Subset |

|||

| CD14+ | CD16+ | CD14++ | CD16− | |

| Controls | 455 ± 66 | 551 ± 96 | 820 ± 51a | 72 ± 45b |

| CKD-NonD | 432 ± 72 | 519 ± 102 | 805 ± 72a | 79 ± 56b |

| HD | 461 ± 68 | 539 ± 91 | 833 ± 64a | 69 ± 66b |

| PD-RRF >1 | 446 ± 59 | 499 ± 106 | 841 ± 57a | 82 ± 57b |

| PD-RRF ≤1 | 469 ± 63 | 542 ± 87 | 835 ± 61a | 76 ± 61b |

P < 0.005 versus CD14+.

P < 0.005 versus CD16+.

Evaluation of CD14+CD16+ Monocyte Phenotype in Controls and Patients

In CKD patients who had been treated by PD, the percentage of CD14++CD16− and CD14+CD16+ monocytes, regardless of their RRF, was similar to that observed in healthy subjects (CD14++CD16−: controls = 82.5% ± 4.6%, PD-RRF >1 = 81.3% ± 2.9%, and PD-RRF ≤1 = 80.9% ± 5.2%; CD14+CD16+: controls = 3.9% ± 1.1%, PD-RRF >1 = 2.2% ± 1.5%, and PD-RRF ≤1 = 4.3% ± 2.1%). On the other hand, the HD patients presented a higher percentage of proinflammatory CD14+CD16+ monocytes (18.9% ± 3.5%) than the control group (3.9% ± 1.1%; P = 0.001), CKD-NonD (7.7% ± 1.2%; P = 0.001), PD-RRF >1 (2.2% ± 1.5%; P = 0.001), and PD-RRF ≤1 ml/min (4.3% ± 2.1%; P = 0.001). There were also significant differences between CKD-NonD and both PD groups (P = 0.001). For the CD14++CD16− monocytes, there were no statistical differences between the groups. The percentages and absolute number of CD14+CD16+ and CD14++CD16− monocytes in the different groups are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

Percentage and absolute number of CD14+CD16+ and CD14++CD16− monocytes

| Monocyte subsets |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD14+CD16+ |

CD14++CD16− |

|||

| %, Mean ± SD | Cells/μl, Mean ± SD | %, Mean ± SD | Cells/μl, Mean ± SD | |

| Controls | 3.9 ± 1.1 | 22 ± 10 | 82.5 ± 4.6 | 355 ± 41 |

| CKD-NonD | 7.7 ± 1.2a | 41 ± 11a | 79.6 ± 8.6 | 321 ± 50 |

| HD | 18.9 ± 3.5b | 84 ± 33b | 77.9 ± 5.8 | 309 ± 48 |

| PD-RRF >1 | 2.2 ± 1.5 | 14 ± 5 | 81.3 ± 2.9 | 372 ± 25 |

| PD-RRF ≤1 | 4.3 ± 2.1 | 27 ± 8 | 80.9 ± 5.2 | 364 ± 39 |

P < 0.05 versus controls, PD-RRF >1, and PD-RRF ≤1.

P < 0.05 versus controls, CKD-NonD, PD-RRF >1, and PD-RRF ≤1.

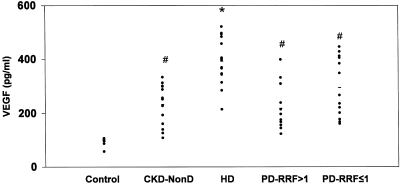

Serum VEGF Protein Concentration

Serum VEGF concentrations were significantly higher in the three groups of uremic patients than in healthy subjects (P < 0.05) (Figure 2). VEGF concentrations were markedly elevated in HD patients (393.1 ± 86.9 pg/ml) in comparison with CKD-NonD (232.0 ± 74.9 pg/ml; P = 0.001), PD-RRF >1 (217.4 ± 86.3 pg/ml; P = 0.001), and PD-RRF ≤1 (287.2 ± 106.7 pg/ml; P = 0.002). There were no differences between the CKD-NonD and either PD group.

Figure 2.

Serum VEGF concentrations were measured by ELISA in control, chronic kidney disease (CKD-NonD), hemodialysis (HD), and peritoneal dialysis with RRF >1 ml/min (PD-RRF >1) patients, and peritoneal dialysis with RRF ≤1 ml/min (PD-RRF ≤1) patients. Values are shown as mean ± standard deviation. *P < 0.05 versus controls, CKD-NonD, PD-RRF >1, PD-RRF ≤1. #P < 0.05 versus controls.

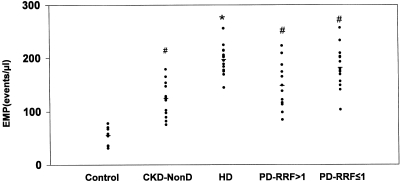

Evaluation of CD31+/Annexin V EMPs in Plasma

Apoptotic EMPs were higher in the three groups of uremic patients than in healthy subjects (Figure 3). Patients on HD presented higher apoptotic EMP values (197.3 ± 26.3 events/μl) than CKD-NonD (124.3 ± 32.4 events/μl; P = 0.001), PD-RRF >1 (148.2 ± 44.2 events/μl; P = 0.001), and PD-RRF ≤1 (179.5 ± 39.8 events/μl; P = 0.002). There were no statistical significance differences between CKD-NonD and both PD groups (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Apoptotic EMPs in platelet-free plasma from control, chronic kidney disease (CKD-NonD), hemodialysis (HD), and peritoneal dialysis with RRF >1 ml/min (PD-RRF >1) patients, and peritoneal dialysis with RRF ≤1 ml/min (PD-RRF ≤1) patients. Apoptotic EMPs were measured by flow cytometry. Apoptotic EMPs are expressed as events per microliter. *P < 0.05 versus controls, CKD-NonD, PD-RRF > 1, PD-RRF ≤ 1. #P < 0.05 versus controls.

Correlation between Microinflammation (CD14+CD16+) and Endothelial Damage (VEGF Concentration and Apoptotic EMPs)

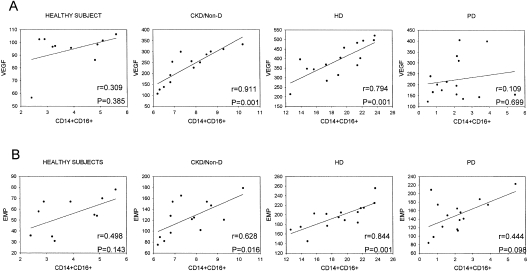

Interestingly, the monocyte percentage of CD14+CD16+ in peripheral blood correlated significantly with VEGF concentration in HD (r = 0.84; P = 0.001) and CKD-NonD patients (r = 0.63; P = 0.02). There was also a significant correlation between CD14+CD16+ and apoptotic EMPs in HD (r = 0.79; P = 0.001) and in CKD-NonD patients (r = 0.91; P = 0.001). However, there was no correlation between these parameters in either PD group and healthy subjects (Figure 4). In CKD-NonD patients, the absolute number of monocytes correlated significantly with EMPs (r = 0.51; P = 0.043) and in HD patients, the absolute number of monocytes correlated with VEGF (r = 0.6; P = 0.031). There was no correlation between CRP and CD14+CD16+ monocytes, EMPs, and VEGF.

Figure 4.

Correlation between CD14+CD16+ cells and serum VEGF concentration or apoptotic EMPs. (A) Percentages of CD14+CD16+ cells were correlated with serum VEGF concentrations in each group. (B) Percentages of CD14+CD16+ cells were correlated with the numbers of apoptotic EMPs in the controls, CKD-NonD, HD, and PD groups. We have shown only a single PD graph because both PD groups displayed similar results.

Discussion

Our results showed an increase in the percentage of CD14+CD16+ monocytes in CKD-NonD and HD patients. In PD patients, regardless of RRF, the percentage of CD14+CD16+ was similar to controls. Endothelial damage, as assessed by an increase in apoptotic EMPs and serum VEGF concentrations, was observed in all CKD groups. It is interesting to note that HD patients displayed significantly higher apoptotic EMPs and VEGF levels than the two PD and CKD-NonD groups. In contrast, there were no differences between CKD-NonD and PD groups. In CKD-NonD and HD patients, the percentage of CD14+CD16+ was correlated with endothelial damage. In summary, it appears that PD, compared with HD, reduces but does not fully prevent the endothelial damage induced by uremia, in spite of presenting a microinflammatory status similar to that of the controls.

We are aware of the limitations of our paper. This is a cross-sectional study of a small sample population. To minimize this potential bias, for each assay tested, measurements were performed in triplicate in the same laboratory and using a single batch of reagents. One other potential bias is that we selected CKD patients with no overt inflammation activity to avoid additional confounding factors. Therefore, these results cannot be extrapolated to patients with inflammation.

Inflammation is considered to be a cardiovascular risk factor for CKD (16,17). It is important to emphasize that our PD patients, in contrast to the results observed in CKD-NonD and HD, did not show microinflammation, as assessed by the percentage of CD14+CD16+ monocytes. In a recent paper, we suggested that the expansion of CD14+CD16+ in CKD patients may be a consequence of an ongoing inflammatory process induced by the uremia itself (13). It is generally accepted that hemodiafiltration offers a highly effective dialysis modality that widens the spectrum of uremic toxins removed from small to medium-sized molecular solutes (18–20). On-line hemodiafiltration using high-substitution fluid produces a greater clearance of large uramic toxins (21,22). Furthermore, we have reported that dialysis modalities with high convective transport are capable of reducing but not normalizing the percentage of CD14+CD16+ monocytes (13). During the HD process, the interaction of peripheral blood mononuclear cells with the dialysis membrane may activate the former, with consequent increased synthesis and release of proinflammatory cytokines (23,24). Our results may be partially explained by the greater ability of PD to remove high-molecular weight uremic toxins (25), although the potential role played by the contact between blood and foreign surfaces in the HD procedure should not be ignored.

With respect to microinflammation, the RRF may be regarded as a confounding factor when HD and PD patients are being compared. However, we found no significant differences between both PD groups, either with or without RRF. Furthermore, the percentage of CD14+CD16+ was higher in the CKD-NonD than PD-RRF ≤1 and PD-RRF >1. The high rate of peritonitis episodes may induce a chronic inflammatory status in PD; the potential selection of stable patients without peritonitis should have bypassed this issue. These data are in agreement with a recent report that demonstrated that the genomic inflammatory profile in PD is different from those observed in HD and uremic patients (26).

Endothelial damage is the first stage in the development of chronic vascular disease (27). Endothelial cells may undergo vesiculation, leading to the release of EMPs into the bloodstream. These EMPs express endothelial-specific surface markers that reflect parent cell status. Apoptotic EMPs have been demonstrated in various pathologies associated with endothelial dysfunction, such as antiphospholipid syndrome (28), preeclampsia (29), and acute coronary syndrome (30). In uremic patients, the degree of EMP elevation is comparable with that reported in these pathologies, suggesting that excessive endothelial vesiculation could act as a new marker of endothelial dysfunction in uremia (31,32). Furthermore, circulating EMPs have recently been reported to correlate with impaired vascular function in HD patients (33). In this study, we have observed that apoptotic EMPs were more numerous in the four uremic groups, being significantly higher in HD than in PD and CKD-NonD patients. However, there were no differences between the PD and CKD-NonD groups.

Other potential factors that might contribute to a better understanding of vascular pathology in CKD patients include cell growth factors (34), such as VEGF. VEGF was initially thought to be an endothelial cell-specific mitogen that induces endothelial cell proliferation, but several studies have shown that VEGF may also contribute to the proliferation of vascular smooth muscle cells (35,36). Recent reports have demonstrated an association between elevated serum VEGF concentration and atherosclerosis (37,38). We have observed in this study that, like those of EMPs, VEGF values were markedly higher in uremic patients than in healthy subjects, and they were significantly higher in HD than in PD and CKD-NonD groups.

We found a correlation between CD14+CD16+ and endothelial damage in CKD-NonD and HD patients but not in PD groups and controls. These findings may be attributed to the normal values of CD14+CD16+ observed in PD patients, regardless of their RRF.

Conclusions

There was an increase in CD14+CD16+ percentage only in CKD-NonD and HD patients. It is important to stress that in these patients there was a relationship between the increased CD14+CD16+ percentage and endothelial damage. These results strongly suggest that other factors unrelated to the microinflammatory status mediated by CD14+CD16+ are promoting the endothelial damage in PD, regardless of RRF.

Disclosures

None.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from: Fondo de Investigación Sanitaria, Instituto de Salud Carlos III (FIS PI06/0724, PI06/0747, PI07/0204, PI08/1038, and Redes Temáticas de Investigación Cooperativa Red Renal RD06/0016/0007), Junta de Andalucía (CM0008, TCRM0006/2006, P06-CVI-02172, P08-CTS-3797), and Fundación Nefrológica. We are grateful to M. J. Jimenez and M. J. Montenegro for technical assistance. J. Carracedo was supported by a contract from the Instituto de Salud Carlos III/Fundación Progreso y Salud (Programa de Estabilización e Incentivación de la Investigación 2006).

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

References

- 1.Foley RN, Parfrey PS, Sarnak MJ: Epidemiology of cardiovascular disease in chronic renal disease. J Am Soc Nephrol 9: S16–23, 1998 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ma KW, Greene EL, Raij L: Cardiovascular risk factors in chronic renal failure and hemodialysis populations. Am J Kidney Dis 19: 505–513, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lameire N, Bernaert P, Lambert MC, Vijt D: Cardiovascular risk factors and their management in patients on continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis. Kidney Int Suppl 48: S31–S38, 1994 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Den Elzen WP, van Manen JG, Boeschoten EW, Krediet RT, Dekker FW: The effect of single and repeatedly high concentrations of C-reactive protein on cardiovascular and non-cardiovascular mortality in patients starting with dialysis. Nephrol Dial Transplant 21: 1588–1595, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Papagianni A, Kokolina E, Kalovoulos M, Vainas A, Dimitriadis C, Memmos D: Carotid atherosclerosis is associated with inflammation, malnutrition and intercellular adhesion molecule-1 in patients on continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis. Nephrol Dial Transplant 19: 1258–1263, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Papagianni A, Kalovoulos M, Kirmizis D, Vainas A, Belechri AM, Alexopoulos E, Memmos D: Carotid atherosclerosis is associated with inflammation and endothelial cell adhesion molecules in chronic haemodialysis patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant 18: 113–119, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ridker PM, Cushman M, Stampfer MJ, Tracy RP, Hennekens CH: Inflammation, aspirin, and the risk of cardiovascular disease in apparently healthy men. N Engl J Med 336: 973–979, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Saionji K, Ohsaka A: Expansion of CD14+CD16+ blood monocytes in patients with chronic renal failure undergoing dialysis: possible involvement of macrophage colony-stimulating factor. Acta Haematol 105: 21–26, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nockher WA, Scherberich JE: Expanded CD14+CD16+ monocyte subpopulation in patients with acute and chronic infections undergoing hemodialysis. Infect Immun 66: 2782–2790, 1998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carracedo J, Ramirez R, Soriano S, Alvarez de Lara MA, Rodriguez M, Martin-Malo A, Aljama P: Monocytes from dialysis patients exhibit characteristics of senescent cells: Does it really mean inflammation?. Contrib Nephrol 149: 208–218, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ramírez R, Carracedo J, Soriano S, Jiménez R, Martín-Malo A, Rodríguez M, Blasco M, Aljama P: Stress-induced premature senescence in mononuclear cells from patients on long-term hemodialysis. Am J Kidney Dis 45: 353–359, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ulrich C, Heine GH, Gerhart MK, Köhler H, Girndt M: Proinflammatory CD14+CD16+ monocytes are associated with subclinical atherosclerosis in renal transplant patients. Am J Transplant 8: 103–110, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carracedo J, Merino A, Nogueras S, Carretero D, Berdud I, Ramírez R, Tetta C, Rodríguez M, Martín-Malo A, Aljama P: On-line hemodiafiltration reduces the proinflammatory CD14+CD16+ monocyte-derived dendritic cells: A prospective, crossover study. J Am Soc Nephrol 17: 2315–2321, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ramirez R, Carracedo J, Merino A, Nogueras S, Alvarez-Lara MA, Rodríguez M, Martin-Malo A, Tetta C, Aljama P: Microinflammation induces endothelial damage in hemodialysis patients: The role of convective transport. Kidney Int 72: 108–113, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Werner N, Wassmann S, Ahlers P, Kosiol S, Nickenig G: Circulating CD31+/annexin V+ apoptotic microparticles correlate with coronary endothelial function in patients with coronary artery disease. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 26: 112–116, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cottone S, Lorito MC, Riccobene R, Nardi E, Mulè G, Buscemi S, Geraci C, Guarneri M, Arsena R, Cerasola G: Oxidative stress, inflammation and cardiovascular disease in chronic renal failure. J Nephrol 21: 175–179, 2008 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Merino A, Nogueras S, Buendía P, Ojeda R, Carracedo J, Ramirez-Chamond R, Martin-Malo A, Aljama P: Microinflammation and endothelial damage in hemodialysis. Contrib Nephrol 161: 83–88, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tattersall J: Clearance of beta-2-microglobulin and middle molecules in haemodiafiltration. Contrib Nephrol 158: 201–209, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mandolfo S, Borlandelli S, Imbasciati E: Leptin and beta2-microglobulin kinetics with three different dialysis modalities. Int J Artif Organs 29: 949–955, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Maduell F, Sánchez-Canel JJ, Blasco JA, Navarro V, Ríus A, Torregrosa E, Pin MT, Cruz C, Ferrero JA: Middle molecules removal. Beyond beta2-microglobulin [in Spanish]. Nefrologia 26: 469–475, 2006 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Testa A, Gentilhomme H, Le Carrer D, Orsonneau JL: In vivo removal of high- and low-molecular-weight compounds in hemodiafiltration with on-line regeneration of ultrafiltrate. Nephron Clin Pract 104: c55–60, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pedrini LA, De Cristofaro V: On-line mixed hemodiafiltration with a feedback for ultrafiltration control: Effect on middle-molecule removal. Kidney Int 64: 1505–1513, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pertosa G, Simone S, Soccio M, Marrone D, Gesualdo L, Schena FP, Grandaliano G: Coagulation cascade activation causes CC chemokine receptor-2 gene expression and mononuclear cell activation in hemodialysis patients. J Am Soc Nephrol 16: 2477–2486, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kaupke CJ, Zhang J, Cesario T, Yousefi S, Akeel N, Vaziri ND: Effect of hemodialysis on leukocyte adhesion receptor expression. Am J Kidney Dis 27: 244–252, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dhondt A, Vanholder R, Van Biesen W, Lameire N: The removal of uremic toxins. Kidney Int Suppl 76: S47–S59, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zaza G, Pontrelli P, Pertosa G, Granata S, Rossini M, Porreca S, Staal FJ, Gesualdo L, Grandaliano G, Schena FP: Dialysis-related systemic microinflammation is associated with specific genomic patterns. Nephrol Dial Transplant 23: 1673–1681, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Choy JC, Granville DJ, Hunt DW, McManus BM: Endothelial cell apoptosis: Biochemical characteristics and potential implications for atherosclerosis. J Mol Cell Cardiol 33: 1673–1690, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dignat-George F, Camoin-Jau L, Sabatier F, Arnoux D, Anfosso F, Bardin N, Veit V, Combes V, Gentile S, Moal V, Sanmarco M, Sampol J: Endothelial microparticles: A potential contribution to the thrombotic complications of the antiphospholipid syndrome. Thromb Haemost 91: 667–673, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.González-Quintero VH, Smarkusky LP, Jiménez JJ, Mauro LM, Jy W, Hortsman LL, O'Sullivan MJ, Ahn YS: Elevated plasma endothelial microparticles in preeclampsia. Am J Obstet Gynecol 189: 589–593, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bernal-Mizrachi L, Jy W, Jimenez JJ, Pastor J, Mauro LM, Horstman LL, de Marchena E, Ahn YS: High levels of circulating endothelial microparticles in patients with acute coronary syndromes. Am Heart J 145: 962–970, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Boulanger CM, Amabile N, Guérin AP, Pannier B, Leroyer AS, Mallat CN, Tedgui A, London GM: In vivo shear stress determines circulating levels of endothelial microparticles in end-stage renal disease. Hypertension 49: 902–908, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Amabile N, Guérin AP, Leroyer A, Mallat Z, Nguyen C, Boddaert J, London GM, Tedgui A, Boulanger CM: Circulating endothelial microparticles are associated with vascular dysfunction in patients with end-stage renal failure. J Am Soc Nephrol 16: 3381–3388, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Faure V, Dou L, Sabatier F, Cerini C, Sampol J, Berland Y, Brunet P, Dignat-George F: Elevation of circulating endothelial microparticles in patients with chronic renal failure. J Thromb Haemost 4: 566–573, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kimura K, Hashiguchi T, Deguchi T, Horinouchi S, Uto T, Oku H, Setoyama S, Maruyama I, Osame M, Arimura K: Serum VEGF–as a prognostic factor of atherosclerosis. Atherosclerosis 194: 182–188, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Osada-Oka M, Ikeda T, Imaoka S, Akiba S, Sato T: VEGF-enhanced proliferation under hypoxia by an autocrine mechanism in human vascular smooth muscle cells. J Atheroscler Thromb 15: 26–33, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mahadev K, Wu X, Donnelly S, Ouedraogo R, Eckhart AD, Goldstein BJ: Adiponectin inhibits vascular endothelial growth factor-induced migration of human coronary artery endothelial cells. Cardiovasc Res 78: 376–384, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sertic J, Slavicek J, Bozina N, Malenica B, Kes P, Reiner Z: Cytokines and growth factors in mostly atherosclerotic patients on hemodialysis determined by biochip array technology. Clin Chem Lab Med 45: 1347–1352, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Celletti FL, Waugh JM, Amabile PG, Brendolan A, Hilfiker PR, Dake MD: Vascular endothelial growth factor enhances atherosclerotic plaque progression. Nat Med 7: 425–429, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]