Abstract

Background and objectives: Chronic kidney disease (CKD) increases systemic inflammation, which is implicated in development and maintenance of atrial fibrillation (AF); therefore, we hypothesized that the prevalence of AF would be increased among nondialysis patients with CKD. This study also reports independent predictors of the presence of AF in this population.

Design, setting, participants, & measurements: A retrospective, cross-sectional analysis of 1010 consecutive nondialysis patients with CKD from two community-based hospitals was conducted. Estimated GFRs (eGFRs) were calculated using the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease (MDRD) equation. Multivariate logistic regression was used to determine independent predictors.

Results: Of 1010 nondialysis patients with CKD, 214 (21.2%) had AF. Patients with AF were older than patients without AF (76 ± 11 versus 63 ± 15 yr). The prevalence of AF among white patients (42.7%) was higher than among black patients (12.7%) or other races (5.7%). In multivariate analyses, age, white race, increasing left atrial diameter, lower systolic BP, and congestive heart failure were identified as independent predictors of the presence of AF. Although serum high-sensitivity C-reactive protein levels were elevated in our population (5.2 ± 7.4 mg/L), levels did not correlate with the presence of AF or with eGFR. Finally, eGFR did not correlate with the presence of AF in our population.

Conclusions: The prevalence of AF was increased in our population, and independent predictors were age, white race, increasing left atrial diameter, lower systolic BP, and congestive heart failure.

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is the most common arrhythmia in clinical practice (1). Cardiac comorbidities that are associated with AF include hypertension, coronary artery disease (CAD), valvular heart disease (VHD), congestive heart failure (CHF), cardiomyopathy, pericarditis, congenital heart disease (CHD), and cardiac surgery (2–9). Noncardiac comorbidities that are associated with AF include acute pulmonary embolism, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), obstructive sleep apnea, hyperthyroidism, and obesity (10–14).

Evidence suggests that inflammation is involved in the pathogenesis of AF (15–20). For example, AF after cardiac surgery is associated with proinflammatory cytokine and complement activation (16,19). Moreover, patients with refractory lone AF have inflammatory infiltrates, myocyte necrosis, and fibrosis on biopsy (18). Several studies also reported elevated serum high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hsCRP) levels in patients with AF (15–17,20).

Evidence suggests that inflammation is associated with renal dysfunction (21–24). Proposed mechanisms include decreased proinflammatory cytokine clearance, endotoxemia, oxidative stress, and reduced antioxidant levels (23,24). Moreover, hsCRP levels are higher among elderly patients with renal insufficiency (24). In hemodialysis (HD) patients with ESRD, hsCRP, IL-6, and fibrinogen levels are elevated (21,22).

HD patients with ESRD have an increased prevalence of AF; however, prevalence among nondialysis patients with CKD has not been investigated (25–30). Because CKD promotes inflammation, which promotes AF, we hypothesized the prevalence of AF would be increased among nondialysis patients with CKD. This study reports the prevalence and independent predictors of the presence of AF in a nondialysis population with CKD.

Materials and Methods

We conducted a retrospective, cross-sectional analysis of consecutive inpatients and outpatients at two community-based teaching hospitals between January and July 2008. Patients had CKD as defined by the Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative (K/DOQI): (1) Evidence of structural or functional kidney damage for ≥3 mo, with or without decreased GFR, manifest by markers of kidney damage (including blood, urine, and imaging abnormalities) or (2) GFR <60 ml/min per 1.73 m2 for ≥3 mo with or without evidence of kidney damage (31).

CKD was stratified as stage 1 (kidney damage, GFR ≥90), stage 2 (GFR 60 to 89), stage 3 (GFR 30 to 59), stage 4 (GFR 15 to 29), or stage 5 (kidney failure, GFR <15 or dialysis) (31). Patients who were in acute renal failure, in a postoperative period, or receiving dialysis were excluded. Moreover, we hypothesized that decreased GFR was associated with inflammation; therefore, patients with stage 1 CKD were also excluded.

Estimated GFR (eGFR) was calculated using the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease (MDRD) equation: eGFR (ml/min per 1.73 m2) = 1.86 × serum creatinine−1.154 × age−0.203 × 0.742 (if female) × 1.210 (if black) (31,32). Patients with AF were identified on the basis of medical record documentation and/or electrocardiographic evidence and classified as paroxysmal, persistent, or permanent. Patients with hypertension were identified on the basis of medical record documentation, and mean systolic (SBP) and diastolic BP (DBP) were systematically calculated from five measurements. Other comorbid conditions were identified on the basis of medical record documentation. Left ventricular (LV) hypertrophy (LVH) was defined as intraventricular septum and/or posterior wall thickness >11 mm. Left atrial (LA) diameter and LV ejection fraction (LVEF) were derived from echocardiographic data. LV systolic dysfunction was defined as LVEF <50%. Similar to a previous study, VHD likely to be associated with AF was defined as any degree of mitral stenosis or moderate to severe mitral regurgitation, aortic stenosis, or aortic regurgitation (26).

Data from patients with and without AF were compared using χ2 and Wilcoxon rank-sum analyses. Univariate linear regression examined the relationship between eGFR and hsCRP levels. Univariate logistic regression identified variables that were associated with the presence of AF, and those with P < 0.1 were included in multivariate analysis using a backward stepwise logistic regression model with a stay criterion of 0.10. A multiplicative model including age-race interaction terms adjusted for significant variables estimated the effect of age (stratified as <50, 50 to 59, 60 to 69, 70 to 79, and ≥80 yr of age) and race (white versus nonwhite) on the prevalence of AF. Odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals were calculated using nonwhite patients who were younger than 50 yr (lowest prevalence of AF) as the denominator. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistics were calculated using Stata statistics software (Stata Corp., College Station, TX).

Results

Prevalence of AF

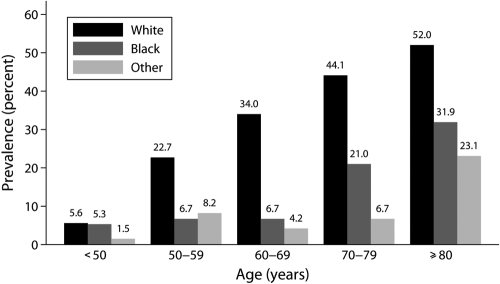

Of 1010 nondialysis patients with CKD, 214 (21.2%) had AF, classified as permanent (38.8%), persistent (18.2%), or paroxysmal (43.0%). The prevalence of AF stratified by age, gender, and race is summarized in Table 1. When stratified by age, the prevalence was 8.1% among those who were younger than 65, 31.6% among those who were aged ≥65, and 45.8% among those who were aged ≥80 yr. When stratified by gender, the prevalence was similar among men (20.6%) and women (21.8%). When stratified by race, the prevalence was 42.7% among white patients, 12.7% among black patients, and 5.7% among other races. When stratified by age and race, the prevalence of AF increased with age, irrespective of race, and was higher among white patients of a given age group (Figure 1). Moreover, the adjusted odds ratio was highest among white patients who were aged ≥80 yr and least among nonwhite patients who were younger than 50 yr (Table 2). When patients with known risk factors for development of AF (e.g., CAD, VHD, CHF, COPD, hyperthyroidism) were excluded from analysis, the prevalence was 6.3% but still increased with age with 3.4% among those who were younger than 65, 10.4% among those who were aged ≥65, and 18.5% among those who were aged ≥80 yr. When stratified by CKD stage, the prevalences were 17.9, 25.2, 20.8, and 8.0% for stages 2 through 5, respectively (Table 1).

Table 1.

Prevalence of atrial fibrillation in nondialysis patients with CKD

| Population | No. of Patients | Patients with AF (n [%]) |

|---|---|---|

| All | 1010 | 214 (21.2) |

| Age (yr) | ||

| <65 | 447 | 36 (8.1) |

| ≥65 | 563 | 178 (31.6) |

| ≥80 | 212 | 97 (45.8) |

| Gender | ||

| male | 520 | 107 (20.6) |

| female | 490 | 107 (21.8) |

| Race | ||

| white | 335 | 143 (42.7) |

| black | 466 | 59 (12.7) |

| other | 209 | 12 (5.7) |

| CKD stage | ||

| 2 | 67 | 12 (17.9) |

| 3 | 496 | 125 (25.2) |

| 4 | 322 | 67 (20.8) |

| 5a | 125 | 10 (8.0) |

Excluding patients who had ESRD and were on hemodialysis.

Figure 1.

Prevalence of atrial fibrillation among nondialysis patients with CKD stratified by age and race.

Table 2.

Effect of age and race on the presence of AF among non-dialysis CKD patients

| Age (yr) | White |

Nonwhite |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adjusted OR | 95% CI | Adjusted OR | 95% CI | |

| <50 | 2.82 | 0.26 to 30.72 | 1.00a | |

| 50 to 59 | 7.23 | 1.37 to 37.17 | 2.62 | 0.64 to 10.62 |

| 60 to 69 | 10.34 | 2.60 to 41.14 | 3.13 | 0.82 to 11.92 |

| 70 to 79 | 19.13 | 5.34 to 68.54 | 7.90 | 2.18 to 28.66 |

| ≥80 | 21.78 | 6.34 to 74.89 | 14.98 | 3.76 to 59.64 |

CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio.

Nonwhite patients <50 yr old, with the lowest prevalence of AF, were used as the denominator to calculate ORs.

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics

Demographic and clinical characteristics of nondialysis patients who had CKD with and without AF are summarized in Table 3. Patients with AF were on average older than patients without AF (76 ± 11 versus 63 ± 15 yr; P < 0.001). The proportions of male and female patients with AF (50.0% male versus 50.0% female) and patients without AF (51.9% male versus 48.1% female) were similar. Moreover, the proportion of white race was higher among patients with than without AF (66.8 versus 24.1%; P < 0.001), the proportion of black race was lower among patients with than without AF (27.6 versus 51.1%; P < 0.001), and the proportion of other races was also lower among patients with than without AF (5.6 versus 24.8%; P < 0.001).

Table 3.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of nondialysis patients who had CKD with and without AF

| Characteristics | Total | AF | Non-AF | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | 1010 (100.0) | 214 (21.2) | 796 (78.8) | |

| Age (yr; mean ± SD) | 65.7 ± 15.0 | 760 ± 11.0 | 63.0 ± 15.0 | <0.001 |

| Male | 520 (51.5) | 107 (50.0) | 413 (51.9) | 0.624 |

| Race | ||||

| white | 335 (33.2) | 143 (66.8) | 192 (24.1) | <0.001 |

| black | 466 (46.1) | 59 (27.6) | 407 (51.1) | <0.001 |

| other | 209 (20.7) | 12 (5.6) | 144 (24.8) | <0.001 |

| Comorbid conditions | ||||

| hypertension | 920 (91.1) | 197 (92.1) | 721 (90.8) | 0.576 |

| diabetes | 599 (59.3) | 113 (52.8) | 486 (61.1) | 0.029 |

| dyslipidemia | 587 (58.2) | 136 (63.5) | 451 (56.7) | 0.730 |

| congestive heart failure | 303 (30.0) | 127 (59.6) | 176 (22.1) | <0.001 |

| coronary artery disease | 344 (34.1) | 125 (58.4) | 219 (27.5) | <0.001 |

| valvular heart disease | 105 (10.4) | 57 (26.6) | 48 (6.0) | <0.001 |

| peripheral vascular disease | 148 (14.7) | 43 (20.2) | 105 (13.2) | 0.011 |

| cerebrovascular accident | 117 (11.6) | 37 (17.3) | 80 (10.1) | 0.003 |

| COPD | 107 (10.6) | 46 (21.7) | 61 (7.7) | <0.001 |

| hyperthyroidism | 10 (1.0) | 7 (3.3) | 3 (0.4) | <0.001 |

| smoking | 311 (32.2) | 72 (34.0) | 239 (31.7) | 0.525 |

| Known causes of CKD | ||||

| diabetic nephropathy | 465 (46.0) | 88 (41.1) | 377 (47.4) | 0.104 |

| hypertensive nephrosclerosis | 256 (25.4) | 61 (28.5) | 195 (24.5) | 0.232 |

| glomerulonephritis | 74 (7.3) | 5 (2.3) | 69 (8.7) | 0.002 |

| cystic disease | 11 (1.1) | 0 (0.0) | 11 (1.4) | 0.084 |

| ischemic nephropathy | 35 (3.5) | 23 (10.5) | 12 (1.5) | <0.001 |

| uropathy | 33 (3.3) | 5 (2.3) | 28 (3.5) | 0.388 |

| tubulointerstitial nephritis | 30 (3.0) | 3 (1.4) | 27 (3.4) | 0.128 |

| BP (mean ± SD) | ||||

| SBP (mmHg) | 136 ± 19 | 127 ± 17 | 138 ± 19 | <0.001 |

| DBP (mmHg) | 72 ± 11 | 67 ± 10 | 73 ± 11 | <0.001 |

| eGFR (ml/min per 1.73 m2) | 34.0 ± 16.1 | 36.5 ± 13.9 | 33.4 ± 16.5 | 0.004 |

| Medications | ||||

| ACEI and/or ARB | 554 (54.9) | 132 (61.7) | 422 (53.0) | 0.024 |

| β blocker | 787 (78.4) | 177 (83.1) | 610 (77.1) | 0.060 |

| statin | 583 (58.1) | 122 (57.6) | 461 (58.2) | 0.863 |

P < 0.05 represents statistical difference between groups. Data are n (%), unless otherwise specified.

Overall, diabetic nephropathy was the most common known cause of CKD in our nondialysis population with CKD (46.0%), followed by hypertensive nephrosclerosis (25.4%). Of known causes of CKD, only ischemic nephropathy occurred more frequently among patients with AF. Comorbidities that occurred more frequently among patients with AF included diabetes, CHF, CAD, VHD, peripheral vascular disease (PVD), cerebrovascular accident (CVA), COPD, and hyperthyroidism (Table 3). Patients with AF also had lower SBP and DBP measurements than patients without AF (127/67 ± 17/10 versus 138/73 ± 19/11 mmHg; P < 0.001 each). AF patients had higher eGFRs than patients without AF (36.5 ± 13.9 versus 33.4 ± 16.5 ml/min per 1.73 m2; P = 0.004). Finally, patients with AF were treated more frequently with angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEIs) and/or angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs). Patients with AF also tended to be treated more frequently with β blockers, whereas statin treatment was similar in both groups.

Echocardiographic and Laboratory Data

Echocardiographic data were obtained from 621 of 1010 nondialysis patients with CKD (Table 4). Patients with AF had lower LVEFs (50.7 ± 15.6 versus 56.8 ± 13.6%; P < 0.001), increased frequency of LV systolic dysfunction (37.2 versus 20.0%; P < 0.001), increased LA diameter (46.4 ± 25.4 versus 40.8 ± 6.5 mm; P < 0.001), and increased frequency of VHD (26.6 versus 6.0%; P < 0.001) than patients without AF; however, there was no difference in frequency of LVH or pulmonary artery systolic pressure between groups.

Table 4.

Echocardiographic data of nondialyhsis patients who have CKD with and without AF

| Echocardiographic Data | AF | Non-AF | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| LVEF (%; mean ± SD) | 50.7 ± 15.6 | 56.8 ± 13.6 | <0.001 |

| LV systolic dysfunction (%) | 37.2 | 20.0 | <0.001 |

| LVH (%) | 64.8 | 61.5 | 0.423 |

| LA diameter (mm; mean ± SD) | 46.4 ± 25.4 | 40.8 ± 6.5 | <0.001 |

| VHD (%) | 26.6 | 6.0 | <0.001 |

| Pulmonary artery systolic pressure (mmHg; mean ± SD) | 44.1 ± 10.4 | 43.9 ± 13.2 | 0.241 |

P < 0.05 represents statistical difference between groups. AF, n = 214; non-AF, n = 407.

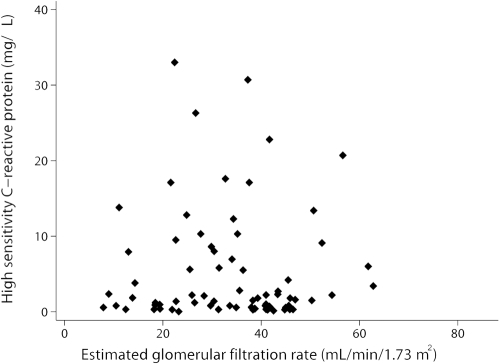

Laboratory data were obtained from all nondialysis patients with CKD (Table 5). Patients with AF had lower serum potassium, calcium, phosphorus, creatinine, albumin, cholesterol, and triglyceride levels and higher serum bicarbonate levels. Levels of hsCRP were obtained from 76 of 1010 nondialysis patients with CKD. Although data were limited, average hsCRP levels were elevated above the reference value (<3.0 mg/L) of our nondialysis population with CKD. Moreover, levels tended to be lower in patients with than without AF (4.3 ± 5.7 versus 5.7 ± 8.2 mg/dl; P = 0.420), although not statistically significant. Finally, to examine the potential relationship between impaired renal function and inflammation, we compared eGFRs with hsCRP levels; however, there was no correlation in our population (Figure 2).

Table 5.

Laboratory data of nondialysis patients who had CKD with and without AF

| Laboratory Data | AF | Non-AF | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hemoglobin (g/dl) | 11.6 ± 1.76 | 11.3 ± 1.8 | 0.062 |

| Sodium (mEq/L) | 138.8 ± 4.3 | 139.2 ± 3.4 | 0.211 |

| Potassium (mEq/L) | 4.1 ± 0.6 | 4.4 ± 0.6 | <0.001 |

| Bicarbonate (mEq/L) | 25.4 ± 4.8 | 24.2 ± 4.0 | <0.001 |

| BUN (mg/dl) | 41.9 ± 22.1 | 40.3 ± 20.3 | 0.523 |

| Creatinine (mg/dl) | 2.0 ± 0.9 | 2.7 ± 1.7 | <0.001 |

| Calcium (mg/dl) | 8.7 ± 0.7 | 8.8 ± 0.7 | <0.001 |

| Magnesium (mg/dl) | 2.1 ± 0.3 | 2.1 ± 0.4 | 0.660 |

| Phosphorus (mg/dl) | 3.7 ± 1.1 | 3.9 ± 1.1 | 0.003 |

| Albumin (g/dl) | 2.9 ± 0.7 | 3.4 ± 0.8 | <0.001 |

| hsCRP (mg/L)a | 4.3 ± 5.7 | 5.7 ± 8.2 | 0.420 |

| Parathyroid hormone (pg/ml)b | 172.9 ± 132.5 | 173.4 ± 167.4 | 0.680 |

| Ferritin (ng/L) | 389.0 ± 671.6 | 272.8 ± 366.7 | 0.240 |

| HbA1c (%) | 7.0 ± 1.8 | 6.9 ± 1.7 | 0.700 |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dl) | 141.0 ± 42.9 | 167.4 ± 46.2 | <0.001 |

| LDL cholesterol (mg/dl) | 81.3 ± 33.6 | 95.6 ± 36.8 | <0.001 |

| HDL cholesterol (mg/dl) | 35.1 ± 11.3 | 42.4 ± 13.9 | <0.001 |

| Triglyceride (mg/dl) | 126.7 ± 111.7 | 150.6 ± 89.0 | <0.001 |

| Urine protein (g/d)c | 1.9 ± 3.3 | 2.1 ± 3.0 | 0.140 |

Data are means ± SD. BUN, blood urea nitrogen; HbA1c, hemoglobin A1c. P < 0.05 represents statistical difference between groups. To convert hemoglobin in g/dl to g/L, multiply by 10; BUN in mg/dl to mmol/L, multiply by 0.357; creatinine in mg/dl to μmol/L, multiply by 88.4; calcium in mg/dl to mmol/L, multiply by 0.2495; magnesium in mEq/L to mmol/L, multiply by 0.411; phosphate in mg/dl to mmol/L, multiply by 0.3229; ferritin in ng/ml to pg/L, multiply by 2.247; albumin in g/dl to g/L, multiply by 10; total, HDL, and LDL cholesterol in mg/dl to mmol/L, multiply by 0.02586; triglyceride in mg/dl to mmol/L, multiply by 0.01129. Sodium, potassium, and bicarbonate in mEq/L and mmol/L are equivalent. Parathyroid hormone in pg/ml and ng/L are equivalent.

n = 76.

n = 60.

n = 64.

Figure 2.

eGFR does not correlate with hsCRP levels in nondialysis patients with CKD. The correlation coefficient is R = −0.36, P = 0.757.

Independent Predictors of AF

Clinical, echocardiographic, and laboratory variables that were associated with the presence of AF in our nondialysis population with CKD identified by univariate logistic regression analyses are summarized in Table 6. Significant variables that were positively associated with AF included age, white race, dyslipidemia, CHF, CAD, PVD, CVA, COPD, hyperthyroidism, increasing LA diameter, VHD, and eGFR. Significant variables that were negatively associated with AF included diabetes, mean SBP and DBP, LVEF, serum potassium, calcium, phosphorus, and albumin levels. Multivariate analysis of significant variables that were identified by univariate logistic regression analyses identified age, white race, increasing LA diameter, lower SBP, and CHF as independent predictors of the presence of AF in our population (Table 7).

Table 6.

Univariate logistic regression analyses for the presence of AF among nondialysis patients with CKD

| Variable | OR | 95% CI | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (yr) | 1.08 | 1.06 to 1.09 | <0.001 |

| Age ≥65 yr | 5.76 | 3.94 to 8.44 | <0.001 |

| White race | 6.34 | 4.57 to 8.79 | <0.001 |

| Diabetes | 0.71 | 0.52 to 0.97 | 0.030 |

| Dyslipidemia | 1.33 | 0.97 to 1.82 | 0.073 |

| CHF | 5.20 | 3.77 to 7.17 | <0.001 |

| CAD | 3.70 | 2.71 to 5.06 | <0.001 |

| PVD | 1.66 | 1.12 to 2.46 | 0.011 |

| CVA | 1.87 | 1.22 to 2.85 | 0.004 |

| COPD | 3.33 | 2.19 to 5.06 | <0.001 |

| Hyperthyroidism | 8.94 | 2.29 to 34.9 | 0.002 |

| Mean SBP (mmHg) | 0.38 | 0.26 to 0.56 | <0.001 |

| Mean DBP (mmHg) | 0.34 | 0.12 to 0.96 | 0.043 |

| LVEF (%) | 0.97 | 0.96 to 0.98 | <0.001 |

| LA diameter (mm) | 2.14 | 1.66 to 2.76 | <0.001 |

| VHD | 5.91 | 3.84 to 9.10 | <0.001 |

| eGFR (ml/min per 1.73 m2) | 1.01 | 1.00 to 1.02 | 0.014 |

| Potassium (mEq/L) | 0.45 | 0.34 to 0.59 | <0.001 |

| Calcium (mg/dl) | 0.73 | 0.60 to 0.90 | 0.003 |

| Phosphorus (mg/dl) | 0.81 | 0.67 to 0.98 | 0.028 |

| Albumin (g/dl) | 0.48 | 0.39 to 0.58 | <0.001 |

| hsCRP (mg/L) | 0.97 | 0.90 to 1.04 | 0.446 |

With the exception of hsCRP, insignificant variables with P ≥ 0.1 are not shown. Variables with P < 0.1 were included in multivariate analysis (Table 7). To convert albumin in g/dl to g/L, multiply by 10; calcium in mg/dl to mmol/L, multiply by 0.2495; phosphate in mg/dl to mmol/L, multiply by 0.3229. Potassium in mEq/L and mmol/L are equivalent. CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio.

Table 7.

Multivariate logistic regression analyses for the presence of AF among nondialysis patients with CKD

| Variable | Adjusted OR | 95% CI | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (yr) | 1.04 | 1.03 to 1.06 | <0.001 |

| Age ≥65 yr | 3.00 | 1.88 to 4.80 | <0.001 |

| White race | 2.06 | 1.32 to 3.21 | 0.001 |

| SBP (mmHg) | 0.98 | 0.97 to 0.99 | 0.005 |

| CHF | 1.69 | 1.11 to 2.59 | 0.015 |

| LA diameter (mm) | 1.70 | 1.26 to 2.29 | <0.001 |

| eGFR (ml/min per 1.73 m2) | 1.01 | 0.99 to 1.02 | 0.410 |

Variables from univariate logistic regression (Table 6) with P < 0.1 were included in multivariate analysis using a backward stepwise logistic regression model with a stay criterion of 0.10. P < 0.05 represents statistical significant. CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio.

Discussion

Although the prevalence of AF was increased in our nondialysis population with CKD, we did not find an association between AF and inflammatory biomarkers or eGFR. The prevalence of AF in our population (21.2%) was greater than estimates in the general population (1.5 to 6.2%) (1,33–36). The prevalence of AF increased with age and was highest among those who were aged ≥80 yr. Patients with AF were older than patients without AF, and the prevalence among patients who were aged ≥65 yr (31.6%) was greater than estimates for the same age group in the general population (5.9%). Studies that estimated the prevalence of AF in HD patients with ESRD (5.4 to 27.0%) vary likely because of different enrollment criteria (25–29). For example, in one HD population, the prevalence of AF was 27.0%, whereas in another that excluded rheumatic VHD and paroxysmal AF the prevalence was 13.6%, whereas in another that included only permanent AF the prevalence was 5.4% (26,27,29). For comparison with our population, we calculated that, without exclusions, the prevalence of AF was 21.2% (versus 27%); when VHD and paroxysmal AF were excluded, it was 10.1% (versus 13.6%); and when only permanent AF was included, it was 8.2% (versus 5.4%). Therefore, the prevalence of AF in our population (21.2%) is at least triple that reported for the general population (1.5 to 6.2%) and within the broad range reported among various HD populations with ESRD (5.4 to 27.0%).

In Framingham Heart Study patients, the prevalence of AF in the general population was higher among men than women (7:1 ratio) (37,38). In our nondialysis population with CKD, the prevalences of AF among male (20.6%) and female (21.8%) patients were similar, as were the proportions of male and female patients with and without AF. With respect to race, studies that estimated the prevalence of AF vary considerably (34,35,38–41). A higher electrocardiographic prevalence of AF was reported in white (7.8%) compared with black (2.5%) hospitalized patients (41). In another study, a higher prevalence of heart failure–associated AF was reported in white (38.3%) compared with black (19.7%) patients (40). Similarly, the prevalence of AF in our population was higher in white (42.7%) compared with black (12.7%) patients or patients of other races (5.7%). These racial differences may be due to genetic polymorphisms that code for intrinsic differences in atrial membrane stability and/or conduction pathways, resulting in different susceptibilities to development of AF (40). When stratified by age and race, the prevalence of AF increased with age, irrespective of race (Figure 1). It is interesting that, when stratified by CKD stage, there was no notable trend.

Clearly, our nondialysis population with CKD is elderly; has a high prevalence of atherosclerotic, diabetic, and hypertensive disease; and is more prone to inflammatory influences and development of AF. Among our population, we found that comorbidities including diabetes, CHF, CAD, VHD, PVD, CVA, COPD, and hyperthyroidism occurred more frequently among patients with AF. Not surprising, diabetic nephropathy (46.0%) and hypertensive nephrosclerosis (25.4%) were common in our nondialysis population with CKD; however, only ischemic nephropathy occurred more frequently among patients with AF. Diabetes was negatively associated with AF by univariate analysis, possibly because of higher frequency of ACEI and/or ARB use among patients with AF. The higher frequency of ACEI and/or ARB use among patients with AF may also reflect their use in treatment of CHF (42,43). Moreover, ACEIs and/or ARBs have been shown to prevent AF, especially among those with systolic LV dysfunction or LVH.

Among our nondialysis population with CKD, echocardiographic data revealed that patients with AF have significantly lower LVEF, increased LA diameter, and increased frequencies of VHD and LV systolic dysfunction; however, there was no difference in frequency of LVH or pulmonary artery SBP between groups. These findings are partially consistent with a study that reported that LVEF and LVH were associated with AF (44). Laboratory data revealed that patients with AF have lower serum potassium, calcium, phosphorus, creatinine, albumin, cholesterol, and triglyceride levels and higher serum bicarbonate levels. We are not aware of any studies with similar data; however, although the mean concentrations of the proarrhythmogenic electrolytes calcium and potassium were different between groups, they were within the range of normality and therefore likely not related to AF in our population.

We hypothesized that the prevalence of AF would be increased among nondialysis patients with CKD because CKD promotes inflammation, which promotes AF. We reasoned that hsCRP levels might be elevated and associated with decreased eGFR in this population. Although hsCRP levels were elevated, there was no association with eGFR (Figure 2). The extent to which renal dysfunction estimated by GFR is related to inflammatory biomarkers is controversial. Some studies reported hsCRP levels are elevated and increased with progression of CKD, whereas others reported no correlation (24,45,46). Several studies also reported an association between elevated hsCRP levels and AF and that higher baseline levels may predict development of AF (15–17,20). Although hsCRP levels were elevated in our nondialysis population with CKD, comparison between patients with and without AF proved difficult because of considerable variation in serum levels. These findings question the utility of hsCRP as an indicator of inflammation in nondialysis patients with CKD and its relevance to AF.

In our nondialysis population with CKD, multivariate analysis found that age and white race are independent predictors of the presence of AF. Moreover, the prevalence of AF was higher among white patients of a given age group, increased with each decade, and was highest among patients who were aged ≥80 yr. That age and white race are independent predictors of the presence of AF is not surprising given the increasing prevalence with age among white patients. CHF and increasing LA diameter were also independent predictors of the presence of AF in our population. Similarly, others have reported that CHF and increasing LA diameter are risk factors for developing AF (7,37,39,44). Overall, our study suggests that the high prevalence of AF in our nondialysis population with CKD may be due to the presence of numerous cardiovascular comorbidities rather than reduced GFR.

Whereas hypertension is associated with AF in the general population, this is not necessarily the case among HD populations with ESRD (7,26,27,37,39). In our nondialysis population with CKD, hypertension was negatively associated with and not a predictor of AF. Rather, lower SBP was an independent predictor of AF in our population. The prevalence of hypertension was >90% in our population, leaving relatively few normotensive patients for comparison, perhaps contributing to these findings. Moreover, although the association between lower SBP and AF is difficult to interpret, it is likely not due to cardiac inefficiency, because mean LVEF, although statistically different between groups, was within the normal range in both groups. As expected, patients with AF had increased prevalence of cardiovascular comorbidities, including CHF and CAD, and accordingly received more evidence-based medications including ACEIs and ARBs; however, β blocker use was similar between groups and likely noncontributory (43,47,48). Overall, the potential relationship between BP and AF among nondialysis patients with CKD should be further examined in longitudinal studies.

CAD and VHD are associated with development of AF in population-based studies (7,37–39); however, in our population, they failed to reach significance by multivariate analysis even when LA diameter was integrated into our statistical model. Perhaps CAD and VHD influence development of AF by mechanisms other than increased LA diameter. Similarly, diabetes and hyperthyroidism are associated with development of AF; however, they failed to reach significance by multivariate analysis (7,37). Moreover, COPD was not an independent predictor of AF in our nondialysis population with CKD, similar to one study but contrary to another (37,39). Finally, decreased LVEF and LVH have been reported as predictors of AF but failed to reach significance in our nondialysis population with CKD (44).

With respect to limitations, this study was designed to determine independent predictors of the presence of AF in a nondialysis population with CKD and does not make comparisons with a control population with normal renal function. Also, CKD and AF are chronic illnesses, often with unidentifiable times of onset. The extent to which the prevalence of AF in our population can be attributed to CKD is also not clear because other comorbidities likely contribute. Moreover, the retrospective design does not allow determination of cause-and-effect relationships. We can only describe the prevalence, demographic and clinical characteristics, and identify independent predictors of the presence of AF in this population. Moreover, hsCRP samples were collected irrespective of coexisting medical conditions and may not entirely reflect inflammatory status with respect to renal dysfunction. This limits conclusions that can be drawn concerning hsCRP and inflammation and its association with AF in this population. We should also note that increasing LA diameter does not necessarily reflect LVH. Finally, our nondialysis population with CKD includes a substantial number of inpatients who typically have a higher prevalence of AF and a greater number of comorbidities than the general population; therefore, caution must be exercised when making comparisons with the general population. Larger multicenter, prospective studies would be ideal to clarify the relationship among renal dysfunction, inflammation, and AF.

Conclusions

We observed a high prevalence of AF in our nondialysis population with CKD, and age, white race, increasing LA diameter, lower SBP, and CHF were identified as independent predictors of the presence of AF. Notably, hsCRP levels were elevated in our population; however, levels did not correlate with the presence of AF or the degree of renal dysfunction estimated by GFR. Finally, eGFR did not correlate with the presence of AF in our population.

Disclosures

None.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Joseph Oyama for reviewing the manuscript.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

Access to UpToDate on-line is available for additional clinical information at http://www.cjasn.org/

References

- 1.Go AS, Hylek EM, Phillips KA, Chang Y, Henault LE, Selby JV, Singer DE: Prevalence of diagnosed atrial fibrillation in adults: national implications for rhythm management and stroke prevention: The AnTicoagulation and Risk Factors in Atrial Fibrillation (ATRIA) Study. JAMA 285: 2370–2375, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carson PE, Johnson GR, Dunkman WB, Fletcher RD, Farrell L, Cohn JN: The influence of atrial fibrillation on prognosis in mild to moderate heart failure: The V-HeFT Studies. The V-HeFT VA Cooperative Studies Group Circulation 87: VI102–VI110, 1993 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dries DL, Exner DV, Gersh BJ, Domanski MJ, Waclawiw MA, Stevenson LW: Atrial fibrillation is associated with an increased risk for mortality and heart failure progression in patients with asymptomatic and symptomatic left ventricular systolic dysfunction: A retrospective analysis of the SOLVD trials. Studies of Left Ventricular Dysfunction. J Am Coll Cardiol 32: 695–703, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maisel WH, Rawn JD, Stevenson WG: Atrial fibrillation after cardiac surgery. Ann Intern Med 135: 1061–1073, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rathore SS, Berger AK, Weinfurt KP, Schulman KA, Oetgen WJ, Gersh BJ, Solomon AJ: Acute myocardial infarction complicated by atrial fibrillation in the elderly: Prevalence and outcomes. Circulation 101: 969–974, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Diker E, Aydogdu S, Ozdemir M, Kural T, Polat K, Cehreli S, Erdogan A, Goksel S: Prevalence and predictors of atrial fibrillation in rheumatic valvular heart disease. Am J Cardiol 77: 96–98, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Krahn AD, Manfreda J, Tate RB, Mathewson FA, Cuddy TE: The natural history of atrial fibrillation: Incidence, risk factors, and prognosis in the Manitoba Follow-Up Study. Am J Med 98: 476–484, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Robinson K, Frenneaux MP, Stockins B, Karatasakis G, Poloniecki JD, McKenna WJ: Atrial fibrillation in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: A longitudinal study. J Am Coll Cardiol 15: 1279–1285, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wong CK, White HD, Wilcox RG, Criger DA, Califf RM, Topol EJ, Ohman EM: New atrial fibrillation after acute myocardial infarction independently predicts death: The GUSTO-III experience. Am Heart J 140: 878–885, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Buch P, Friberg J, Scharling H, Lange P, Prescott E: Reduced lung function and risk of atrial fibrillation in the Copenhagen City Heart Study. Eur Respir J 21: 1012–1016, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gami AS, Pressman G, Caples SM, Kanagala R, Gard JJ, Davison DE, Malouf JF, Ammash NM, Friedman PA, Somers VK: Association of atrial fibrillation and obstructive sleep apnea. Circulation 110: 364–367, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goldhaber SZ, Visani L, De Rosa M: Acute pulmonary embolism: Clinical outcomes in the International Cooperative Pulmonary Embolism Registry (ICOPER). Lancet 353: 1386–1389, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Woeber KA: Thyrotoxicosis and the heart. N Engl J Med 327: 94–98, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang TJ, Parise H, Levy D, D'Agostino RB, Sr, Wolf PA, Vasan RS, Benjamin EJ: Obesity and the risk of new-onset atrial fibrillation. JAMA 292: 2471–2477, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aviles RJ, Martin DO, Apperson-Hansen C, Houghtaling PL, Rautaharju P, Kronmal RA, Tracy RP, Van Wagoner DR, Psaty BM, Lauer MS, Chung MK: Inflammation as a risk factor for atrial fibrillation. Circulation 108: 3006–3010, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bruins P, te Velthuis H, Yazdanbakhsh AP, Jansen PG, van Hardevelt FW, de Beaumont EM, Wildevuur CR, Eijsman L, Trouwborst A, Hack CE: Activation of the complement system during and after cardiopulmonary bypass surgery: Postsurgery activation involves C-reactive protein and is associated with postoperative arrhythmia. Circulation 96: 3542–3548, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chung MK, Martin DO, Sprecher D, Wazni O, Kanderian A, Carnes CA, Bauer JA, Tchou PJ, Niebauer MJ, Natale A, Van Wagoner DR: C-reactive protein elevation in patients with atrial arrhythmias: Inflammatory mechanisms and persistence of atrial fibrillation. Circulation 104: 2886–2891, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Frustaci A, Chimenti C, Bellocci F, Morgante E, Russo MA, Maseri A: Histological substrate of atrial biopsies in patients with lone atrial fibrillation. Circulation 96: 1180–1184, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gaudino M, Andreotti F, Zamparelli R, Di Castelnuovo A, Nasso G, Burzotta F, Iacoviello L, Donati MB, Schiavello R, Maseri A, Possati G: The −174G/C interleukin-6 polymorphism influences postoperative interleukin-6 levels and postoperative atrial fibrillation: Is atrial fibrillation an inflammatory complication? Circulation 108 [Suppl 1]: II195–II199, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gedikli O, Dogan A, Altuntas I, Altinbas A, Ozaydin M, Akturk O, Acar G: Inflammatory markers according to types of atrial fibrillation. Int J Cardiol 120: 193–197, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bologa RM, Levine DM, Parker TS, Cheigh JS, Serur D, Stenzel KH, Rubin AL: Interleukin-6 predicts hypoalbuminemia, hypocholesterolemia, and mortality in hemodialysis patients. Am J Kidney Dis 32: 107–114, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Owen WF, Lowrie EG: C-reactive protein as an outcome predictor for maintenance hemodialysis patients. Kidney Int 54: 627–636, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Panichi V, Migliori M, De Pietro S, Taccola D, Bianchi AM, Norpoth M, Metelli MR, Giovannini L, Tetta C, Palla R: C reactive protein in patients with chronic renal diseases. Ren Fail 23: 551–562, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shlipak MG, Fried LF, Crump C, Bleyer AJ, Manolio TA, Tracy RP, Furberg CD, Psaty BM: Elevations of inflammatory and procoagulant biomarkers in elderly persons with renal insufficiency. Circulation 107: 87–92, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Atar I, Konas D, Acikel S, Kulah E, Atar A, Bozbas H, Gulmez O, Sezer S, Yildirir A, Ozdemir N, Muderrisoglu H, Ozin B: Frequency of atrial fibrillation and factors related to its development in dialysis patients. Int J Cardiol 106: 47–51, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Genovesi S, Pogliani D, Faini A, Valsecchi MG, Riva A, Stefani F, Acquistapace I, Stella A, Bonforte G, DeVecchi A, DeCristofaro V, Buccianti G, Vincenti A: Prevalence of atrial fibrillation and associated factors in a population of long-term hemodialysis patients. Am J Kidney Dis 46: 897–902, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vazquez E, Sanchez-Perales C, Borrego F, Garcia-Cortes MJ, Lozano C, Guzman M, Gil JM, Borrego MJ, Perez V: Influence of atrial fibrillation on the morbido-mortality of patients on hemodialysis. Am Heart J 140: 886–890, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fabbian F, Catalano C, Lambertini D, Tarroni G, Bordin V, Squerzanti R, Gilli P, Di Landro D, Cavagna R: Clinical characteristics associated to atrial fibrillation in chronic hemodialysis patients. Clin Nephrol 54: 234–239, 2000 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Abe S, Yoshizawa M, Nakanishi N, Yazawa T, Yokota K, Honda M, Sloman G: Electrocardiographic abnormalities in patients receiving hemodialysis. Am Heart J 131: 1137–1144, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Genovesi S, Vincenti A, Rossi E, Pogliani D, Acquistapace I, Stella A, Valsecchi MG: Atrial fibrillation and morbidity and mortality in a cohort of long-term hemodialysis patients. Am J Kidney Dis 51: 255–262, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.K/DOQI clinical practice guidelines for chronic kidney disease: Evaluation, classification, and stratification. Am J Kidney Dis 39: S1–266, 2002 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Levey AS, Bosch JP, Lewis JB, Greene T, Rogers N, Roth D: A more accurate method to estimate glomerular filtration rate from serum creatinine: A new prediction equation. Modification of Diet in Renal Disease Study Group Ann Intern Med 130: 461–470, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Langenberg M, Hellemons BS, van Ree JW, Vermeer F, Lodder J, Schouten HJ, Knottnerus JA: Atrial fibrillation in elderly patients: Prevalence and comorbidity in general practice. BMJ 313: 1534, 1996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lip GY, Golding DJ, Nazir M, Beevers DG, Child DL, Fletcher RI: A survey of atrial fibrillation in general practice: The West Birmingham Atrial Fibrillation Project. Br J Gen Pract 47: 285–289, 1997 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lok NS, Lau CP: Prevalence of palpitations, cardiac arrhythmias and their associated risk factors in ambulant elderly. Int J Cardiol 54: 231–236, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wolf PA, Abbott RD, Kannel WB: Atrial fibrillation as an independent risk factor for stroke: The Framingham Study. Stroke 22: 983–988, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Benjamin EJ, Levy D, Vaziri SM, D'Agostino RB, Belanger AJ, Wolf PA: Independent risk factors for atrial fibrillation in a population-based cohort. The Framingham Heart Study. JAMA 271: 840–844, 1994 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wolf PA, Benjamin EJ, Belanger AJ, Kannel WB, Levy D, D'Agostino RB: Secular trends in the prevalence of atrial fibrillation: The Framingham Study. Am Heart J 131: 790–795, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Furberg CD, Psaty BM, Manolio TA, Gardin JM, Smith VE, Rautaharju PM: Prevalence of atrial fibrillation in elderly subjects (the Cardiovascular Health Study). Am J Cardiol 74: 236–241, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ruo B, Capra AM, Jensvold NG, Go AS: Racial variation in the prevalence of atrial fibrillation among patients with heart failure: The Epidemiology, Practice, Outcomes, and Costs of Heart Failure (EPOCH) study. J Am Coll Cardiol 43: 429–435, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Upshaw CB, Jr: Reduced prevalence of atrial fibrillation in black patients compared with white patients attending an urban hospital: an electrocardiographic study. J Natl Med Assoc 94: 204–208, 2002 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Healey JS, Baranchuk A, Crystal E, Morillo CA, Garfinkle M, Yusuf S, Connolly SJ: Prevention of atrial fibrillation with angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers: A meta-analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol 45: 1832–1839, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Effect of enalapril on survival in patients with reduced left ventricular ejection fractions and congestive heart failure. The SOLVD Investigators N Engl J Med 325: 293–302, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vaziri SM, Larson MG, Benjamin EJ, Levy D: Echocardiographic predictors of nonrheumatic atrial fibrillation. The Framingham Heart Study Circulation 89: 724–730, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sarnak MJ, Poindexter A, Wang SR, Beck GJ, Kusek JW, Marcovina SM, Greene T, Levey AS: Serum C-reactive protein and leptin as predictors of kidney disease progression in the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease Study. Kidney Int 62: 2208–2215, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Oberg BP, McMenamin E, Lucas FL, McMonagle E, Morrow J, Ikizler TA, Himmelfarb J: Increased prevalence of oxidant stress and inflammation in patients with moderate to severe chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int 65: 1009–1016, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hjalmarson A, Goldstein S, Fagerberg B, Wedel H, Waagstein F, Kjekshus J, Wikstrand J, El Allaf D, Vitovec J, Aldershvile J, Halinen M, Dietz R, Neuhaus KL, Janosi A, Thorgeirsson G, Dunselman PH, Gullestad L, Kuch J, Herlitz J, Rickenbacher P, Ball S, Gottlieb S, Deedwania P: Effects of controlled-release metoprolol on total mortality, hospitalizations, and well-being in patients with heart failure: The Metoprolol CR/XL Randomized Intervention Trial in Congestive Heart Failure (MERIT-HF). MERIT-HF Study Group JAMA 283: 1295–1302, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Waagstein F, Bristow MR, Swedberg K, Camerini F, Fowler MB, Silver MA, Gilbert EM, Johnson MR, Goss FG, Hjalmarson A: Beneficial effects of metoprolol in idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy. Metoprolol in Dilated Cardiomyopathy (MDC) Trial Study Group Lancet 342: 1441–1446, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]