Introduction

“To do no harm” is at the heart of the physician's creed, yet the paradox of standard cancer therapy practiced today is that deleterious side effects of harsh chemical and radioactive agents adversely impact a patient's overall well-being. The complexity of cancer results from the aberrations and functional alterations in many genes, gene products, and cell control and signaling pathways and it is clear that current cancer therapies are far too invasive, painful, toxic, and associated with too many acute and chronic side effects. Furthermore, cancer cure rates for most types of human malignancies have improved minimally or not at all over the last three decades. Obviously, novel treatment approaches that improve patient outcomes while minimizing toxicity are sorely needed.

In order to improve the quality of patient care, targeted cancer therapy has been developed to treat cancer specifically, while allowing normal tissue to remain unaffected by chemotherapy. To achieve this goal, one must be able to distinguish the molecular signature of cancer cells amongst trillions of healthy cells in the body and then deliver a therapeutic agent which binds to only cancer cells in order destroy diseased tissue without harm to normal healthy tissues. The grand promise of targeted cancer therapy has been actively pursued for several decades with the hope that it can positively impact the lives of cancer patients. To accomplish this task requires several advances in our ability to detect and treat cancer, and nanotechnology provides a possible key to unlock the challenging problem of treating cancer cell-by-cell.

1. Nanotechnology and nanoscale materials

Nanotechnology involves materials with structures and arrangements of atoms so small that their physical properties are enhanced by quantum level phenomena[1]. In contrast to the small size of items studied, nanotechnology has become a broad field of study involving chemistry, physics, engineering, computing, electronics, energy, and biomedicine. In this latter realm of biomedicine, nanotechnology is widely touted as one of the next promising and important approaches to diagnose and treat cancer [2-5].

Nanoparticles are being used to enhance delivery of anticancer agents to malignant cells. A major problem with anticancer drugs is a narrow therapeutic index with significant acute and cumulative toxicities in normal tissues. Various nanoparticles are being used in preclinical and in vitro studies to increase the delivery of cytotoxic chemotherapy drugs to cancer cells while reducing toxicity by limiting exposure of the drug to normal tissues. For example, nanoparticles loaded with hydroxycamptothecin [6], 5-fluorouracil [7], docetaxel [8], and gemcitabine [9] have been used in preclinical studies to improve chemotherapy-induced cytotoxicity in lung, colon, squamous, and pancreas cancers. Colloidal gold nanoparticles bearing tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF- α) molecules are being used in early phase human clinical trials to treat several types of cancer. Preclinical studies demonstrated that delivery of TNF- α to malignant tumors was enhanced using the nanoparticle delivery system, while avoiding the systemic toxicities that usually limit the clinical utility of this biologic agent [10, 11]. Nanoparticles conjugated with targeting agents are also being investigated to deliver gene therapy payloads to malignant cells [12, 13]. Carbon nanotubes have been used to deliver genes or proteins through non-specific endocytosis in cancer cells [14]. Similar to some cytotoxic chemotherapy drugs, gold or other metal nanoparticles have been shown to improve the therapeutic efficacy of external beam ionizing radiation in preclinical models [15]. Nanoparticles will continue to be investigated vigorously as delivery vectors for biologic and pharmacologic agents.

In addition to being used to deliver cytotoxic or biologic agents, some nanoparticles may be useful as anticancer therapeutic agents. Gold nanoparticles 5-10 nm in diameter have been shown to have intrinsic antiangiogenic properties [16, 17]. These gold nanoparticles bind to heparin-binding pro-angiogenic growth factors such as VEGF165 and bFGF and inhibit their activity. Gold nanoparticles also reduce ascites accumulation in a preclinical model of ovarian cancer, inhibit proliferation of multiple myeloma cells, and induce apoptosis in chronic B cell leukemia.

In addition to therapeutic uses, nanoparticles may have a role in improving detection and diagnosis of cancer. Magnetic iron nanoparticles have been found to enhance the diagnostic ability of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) compared to currently available contrast agents used to image cancer patients [18, 19]. Conjugating the iron magnetic nanoparticles to antibodies that target proteins expressed on the surface of human cancer cells may further enhance the accuracy of MRI to diagnose early stage cancer [20]. Carbon or polymeric nanoparticles labeled with fluorine-18 deoxyglucose have been studied in preclinical models to enhance tumor diagnosis and detection rates using positron emission tomography [21, 22]. Surface modification of quantum dots, semiconductor nanocrystals that emit fluorescence on excitation with the appropriate wavelength of light, are being investigated to better detect lymph node and other sites of metastases during surgical procedures [23, 24]. Conjugation of quantum dots with tumor-specific peptides or antibodies may improve targeting of cancer cells and thus improve the diagnostic accuracy of this optical imaging technique. Imaging techniques using fluorescent nanoparticles targeted to a variety of types of human cancer with immunoconjugation with targeting molecules is being studied to permit in vivo localization of malignant cells [25, 26]. It is hoped that such imaging techniques will improve the diagnostic accuracy in numerous types of imaging modalities used to detect and follow patients with cancer. It is possible these techniques may also allow earlier detection of cancer in high-risk populations and guide the duration and type of therapy in patients with more advanced stages of malignant disease.

Finally, immunocomplexes consisting of gold nanoparticles and labeled antibodies have been demonstrated to improve the detection of several known serum tumor markers, including carcinoembryonic antigen, carcinoma antigen 125, and carbohydrate antigen 19-9, in a more rapid and accurate fashion than currently available techniques [27]. The use of nanoparticles to improve detection of cancer will undoubtedly continue to expand.

2. Targeting Cancer

Targeted therapies for cancer are more than “hot” topics for clinicians and scientists, this concept has been introduced and discussed by the popular press and is now sought by cancer patients. Several cancer specific molecules can be used to bind to cancer cells to deliver nanoparticles to malignant cells. Table 1 is a selection of FDA approved antibodies that are clinically used to treat tumors and can be conjugated to nanoparticles. Other targeting moieties such as aptamers (small nucleic acid sequences) bind to target receptors in the neovasculature of tumors or on the surface of prostate cancer cells [28-30] and have been conjugated to gold nanoparticles for diagnostic applications. Cell-penetrating peptides (< 100 amino acids) have also been shown to target certain types of cancer cells. A prime example would the 86 amino acid HIV-1 Tat protein which has been conjugated to gold nanoparticles resulting in rapid intracellular uptake and localization to the nucleus [31, 32].

Table 1. FDA approved cancer targeting antibodies or small molecules.

| Name | Brand Name | Type | Target | Cancer Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bevacizumab | Avastin | Antibody | Vascular endothelial growth factor | Colorectal, non-small cell lung, breast |

| Imatinib | Gleevec | Molecule | Bcr-abl | Leukemia, gastrointestinal |

| Bortezomib | Velcade | Molecule | Proteasome 26s | Myeloma, lymphoma |

| Trastuzumab | Herceptin | Antibody | HER2 receptor | Breast |

| Gefitinib | Iressa | Molecule | Epithelial growth factor receptor(EGFR) | Non-small cell lung |

| Sorafenib | Nexavar | Molecule | Vascular endothelial growth factor receptor (VEGFR) and Platelet derived growth factor receptor | Kidney, liver |

| Tositumomab | Bexxar | Antibody | CD20 | Lymphoma |

| Tamoxifen | Nolvadex | Molecule | Estrogen receptor | Breast |

| Rituximab | Rituxan | Antibody | CD20 | Lymphoma |

Identification of cancer-specific ligands not expressed on normal cells will permit targeting of nanoparticles to only malignant cells for hyperthermic treatment, and should allow treatment of tumors and micrometastatic disease with minimal therapy-related toxicities. Unfortunately, most potential cancer targeting ligands, like epithelial growth factor receptors, are overexpressed in cancer cells but are not unique. Constitutive expression of ligands in normal cells will lead to uptake of targeted nanoparticles in nonmalignant tissues, thus creating potential toxicities and limitations using nanoparticles for drug delivery or hyperthermia. Any possible target molecule in cancer cells may provide a feasible means for targeting but will require careful evaluations to determine efficacy for targeted thermal ablation.

3. Hyperthermia

The concept of using heat to treat cancer is not new. As early as the late 1800's, physicians were using heat as treatment for cancer [33]. Clearly, there were no randomized controlled trials to describe hyperthermic treatment of cancer, but many reports described patients “cured” of their disease after undergoing febrile illness or external heating of superficial tumors [33]. Whereas hyperthermia once referred to whole body hyperthermia, a specific location (hyperthermic peritoneal perfusion), or an entire body region (isolated limb hyperthermia), we can now describe hyperthermia in terms of cellular, tissue (i.e. portions of organ), or any combination of the above.

3.1 Mechanism of Hyperthermia & Cell Death

Temperatures above 42°C will induce cell death in some tissues. Cells- cancer or otherwise – heated to temperatures in the range of 41°C to 47°C begin to show signs of apoptosis [34-36], while increasing temperatures above 50°C is associated with less apoptosis and more frank necrosis. Several types of pharmacologic or biologic agents “death-inducing signaling complexes” [34] -activate caspase-8 and cause apoptotic cell death in an orderly fashion. Noxious stimuli, including heat or cold, can induce proapoptotic proteins to induce caspase-9. Caspase-8 or -9 expression causes a cascade effect that eventually leads to cell death. Apoptosis requires protein creation mechanisms to be intact.

Necrosis, however, is a much quicker cell death. The extreme example involves heating cells to boiling temperatures where the proteins instantly denature and the cells literally fall apart as lipid bilayers “melt.” Cell necrosis, however, is fundamentally based on protein denaturing. Other than thermal extremes, cell exposure to strong acids and bases can cause necrosis as well.

Next, the concept of ‘thermotolerance’ [33, 36] is important in describing the limitations of hyperthermic treatment. Resistance is the ability to maintain viability with increasing temperature, duration, or frequency. Tolerance, on the other hand, is the ability to maintain homeostasis at a given temperature, stable heat duration, or stable frequency. Heat-shock proteins (HSP) may be able to allow some cells to remain viable after low intensity, repeated hyperthermic treatments. In addition, HSP may induce some tolerance [36]. The exact mechanisms and temporal relationships are still to be elucidated.

The current model of apoptotic hyperthermic cell death [34] suggests that increased temperatures will activate procaspase-2, and it will activate other apoptotic proteins (e.g. Bax, Bak). This leads to mitochondrial membrane damage, which is essential for hyperthermic induced apoptotic cell death [34]. Cytochrome c, as well, plays an important mechanistic role. Mild to moderate hyperthermia (≤ 43°C), in most cases, induces a predominately apoptotic cell death. However, a notable exception is radiofrequency ablation of hepatic tumors where there is clearly intratumoral necrosis [37]. Tissue heated with invasive radiofrequency ablation, as an example, typically creates three zones of cell death: a zone of frank necrosis, a region surrounding this inner core of moderate necrosis, and an outer zone of apoptosis due to lower levels of heating still sufficient to be cytotoxic [37]. A fourth zone, perhaps, is considered surrounding this where tissues heat, but not sufficiently to induce significant apoptosis. Obviously, this is a theoretical model where we are not considering proximity to blood vessels, healthy tissues, or fibrous scar tissues. These “target” zones exist in all situations, regardless of thermal source (laser, microwave probe, radiofrequency needle), where temperatures are sufficient to induce necrosis.

3.2 Hyperthermia & Chemotherapy

Hyperthermic adjuvant chemotherapy plays an increasing role in multimodality cancer treatment [38]. It has been suggested that minimal tissue hyperthermia will increase blood flow, and this will yield higher concentrations of chemotherapeutic agents [36, 38]. Furthermore, the relationship between hypoxia, hyperthermia, hydrogen ion concentration, and cell death is not clear [35, 38, 39]. Unfortunately, few studies have determined the optimal hyperthermic-chemotherapeutic dose relationship, but multiple protocols have proven clinically effective [35, 36, 39].

In general, local hyperthermia to 43°C during chemotherapy infusion produces a “more than additive” [38, 39] increase in cell death compared to chemotherapy alone. Hyperthermic intraoperative peritoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC) is a specific example where synchronous hyperthermic treatment and chemotherapy are used. Patient selection is of paramount importance as the depth of tissue penetration by the drugs is limited (1-3 mm) and varies with different cytotoxic agents [40]. Only after aggressive debulking (i.e. little to no macroscopic disease present on all peritoneal surfaces) is there any hope for an effective treatment from hyperthermic chemotherapy- both the heat and the cytotoxic drug must reach the remaining cancer cells.

Isolated hyperthermic limb perfusion is another therapy that permits regional heating and chemotherapy. Approximately 50% of metastatic melanoma or sarcomatous lesions of the extremities can be treated in this fashion as the metastases are located distal to access points of large vessels [41, 42]. Effective chemotherapeutic agents coupled with hyperthermic treatment have increased the response rates to 94% in melanoma patients with intransit metastases in one retrospective review [43]. This exemplifies the importance of the proper selection of chemotherapeutic agents and patients.

3.3 Hyperthermia & Radiotherapy

Similar to chemotherapy, radiotherapy (ionizing radiation) is more effective using hyperthermia as an adjunct to treatment [35, 44, 45]. Although this effect is synergistic, the temporal relationship is quite important- synchronous treatment producing tumor hyperthermia during irradiation seems most ideal while heat before radiation is more effective than the inverse [36]. Clinically, multiple cancers had complete response rates increased by an absolute 16% to 26% [44, 45] when hyperthermia was added to standard external beam radiotherapy.

3.4 Radiofrequency Ablation

Although radiofrequency ablation (RFA) has been used in the treatment of cancer, cardiac conduction abnormalities, and neurological lesions, it is most commonly used in cancer therapies [37, 38, 49-52]. Unresectable malignant hepatic lesions are the most common tumor treated with this procedure. These include both primary hepatic malignancies as well as metastatic lesions to the liver. There are three primary indications for RFA in hepatic malignancies (primary or metastatic). First, patients that would not survive a hepatic resection (resection is considered the only possible ‘curative’ treatment for many hepatic malignancies or metastases) because they have poor liver function are often considered for RFA if malignant disease is confined to the liver. Second, if there are multiple hepatic tumors where complete resection is not feasible, RFA may provide an opportunity to treat the smaller lesions while the larger tumors are resected. Finally, palliative therapy with RFA is performed to control symptoms, particularly in hormone-producing tumors, when there are other non-hepatic metastatic lesions.

Fundamentally, a RFA needle electrode is guided, typically by ultrasonic imaging, into the central region of a tumor. This is done percutaneously or at the time of a larger operation (i.e. laparotomy or laparoscopy). Wires, coils, or tines are deployed out from the tip of the electrode in a pre-determined pattern (typically circular or disc shaped, spherical, or some combination). RF energy is then applied such that temperatures exceed 60°C and often reach greater than 100°C [37, 38]. Often, tumors are larger than the effective size of a given electrode (approximately 2.5 cm), and therefore, multiple treatments in various areas throughout and surrounding the tumor will be required. Furthermore, inconsistencies in the ablation thermal distribution pattern require multiple overlapping treatments. Although there is no theoretical maximum in tumor size, radiofrequency ablation is much less effective on larger tumors- viable malignant cells may “escape” hyperthermic destruction by failure to completely overlap zones of coagulative necrosis. For example, hepatocellular carcinoma and hepatic metastatic lesions larger than 6 cm have significantly higher local recurrence rates because of incomplete thermal destruction [37, 50] after RFA. Of note, many lesions near blood vessels can safely be treated with hyperthermia (typically, radiofrequency ablation) because the blood flow may actually protect the endothelium from hyperthermic injury [38], but the adjacent blood vessels may also act as a heat sink preventing cytotoxic temperatures in neighboring cancer cells.

Although a form of non-ionizing radiation, microwave coagulation therapy induces necrosis by hyperthermia in an invasive fashion [46, 47] similar to radiofrequency ablation. Effectiveness of this modality is still unclear, but the results are not overwhelming. In one series of hepatocellular carcinoma [46], microwave ablation proved somewhat effective. However, in pancreatic cancer [48], it was much less. Obviously, these are not randomized controlled trials and very different disease processes, but the role of microwave ablation therapy is unclear.

4. Metal nanoparticle heating

Radiofrequency, microwave, and laser based hyperthermia allow for less invasive treatments but still require insertion of a probe into the lesion to be treated. Recent advances in nanoscale materials has provided a potentially non-invasive means of heating cells to therapeutic (i.e. cytotoxic) levels. Molecularly-labeled nanoparticles targeted specifically to cancer cells allows for non-invasive implementation using non-ionizing electromagnetic radiation. Careful exposure to electromagnetic energy permits controlled, adjustable heating to reach therapeutic temperatures. Collateral damage to surrounding tissues is minimized by the localization of the targeted nanoparticles close to or within the cellular target. Although nanotechnology is a relatively new field of investigation, using targeted nanoparticles in the hyperthermic treatment of cancer cells will be a viable option to treat cancer patients.

Targeted hyperthermia is achieved by using nanoscale metallic particles that convert electromagnetic energy into heat. Electromagnetic heating of nanoparticles to treat cancer presents both grand opportunities and challenges for the noninvasive treatment of cancer and other temperature sensitive disease. Uptake of nanoparticles by malignant, but not normal cells will allow for noninvasive delivery of electromagnetic energy. Metal nanoparticles exemplify the potential for the application in targeted hyperthermic therapy, specifically, iron oxide nanoparticles, gold-silica nanoshells, solid gold nanoparticles and carbon nanotubes. The conversion of electromagnetic energy to heat depends on number of physical factors specific to the metal nanoparticle type and their electrodynamic response. We will now consider several nanoparticles and their hyperthermic properties with respect to their metallic composition, size, and electromagnetic radiation-induced release of heat.

4.1 Magnetic nanoparticle heating

Iron oxide nanoparticles have been used as both diagnostic and therapeutic nanoscale materials to treat deep tissue tumors. Oscillating magnetic fields (∼kHz-MHz) applied to magnetic nanoparticles such as iron oxide nanoparticles (Fe3O4) results in the generation of heat due to two mechanisms that are size dependent. For single domain nanoparticles (<100 nm) the greatest relaxation losses are due either to Brownian modes (heat due to friction arising from total particle oscillations) or Neél modes (heat due to rotation of the magnetic moment with each field oscillation). Commercially available iron nanoparticles such as Feridex are coated with sugars (e.g. dextran) for biocompatibility and aqueous stability in the saline environment of biological tissues. The dextran coating facilitates chemical derivatization and provides a basis for targeting magnetic nanoparticles to regions of diagnostic and therapeutic interest. Feridex has the benefit of being both a hyperthermic agent and a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) contrast material. However, heat produced using inductively-coupled magnetic fields results in limited thermal enhancement requiring extremely high concentrations of iron oxide [53]. These high concentrations and the difficulty targeting the iron oxide nanoparticles to only cancer cells leads to destruction of normal (nonmalignant) cells surrounding the tumor. Nonetheless, iron nanoparticles continue to be investigated actively because of minimal toxicities and the potential for rapid heating of tumor tissue [54].

4.2 Gold nanoparticles

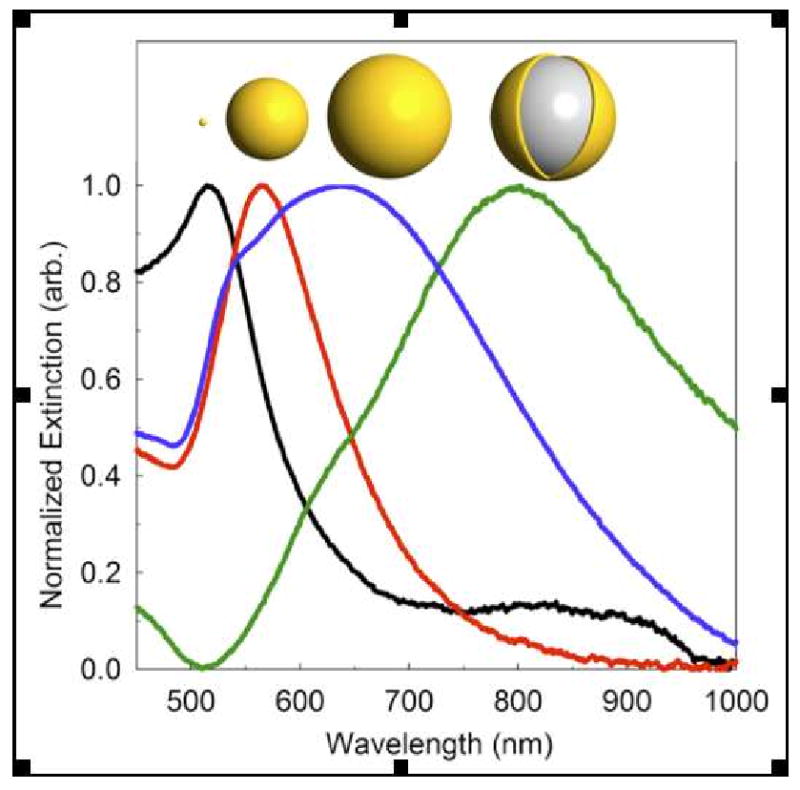

Gold nanoparticles are simply solid gold nanospheres that can range in diameter from 2 nm to several 100 nm. Gold nanoparticles have a characteristic extinction spectra due to plasmonic absorptions (Figure 1). Recent advances have produced gold-silica nanoshells which are composite nanoparticles composed of an inner silica (glassy) core ∼ 100 nm diameter and a thin outer layer of gold (10-15 nm thick) [54]. This metal-dielectric composite structure results in a red shift of gold's characteristic plasmon absorption spectrum into the near-infrared (NIR) region (650 – 950 nm). The gold shell thickness to core diameter ratio can be adjusted and be used to tune the absorption characteristics of the nanoparticle synthetically. The ability to construct nanoscale materials with specific plasmon absorption characteristics provides the pharmaceutical chemist a new tool in their chemotherapeutic arsenal. For superficial lesions, it is adequate to use nanoscale thermal enhancers to absorb optical energy and induce thermal injury. Unfortunately, this is inadequate for deeper lesions given the limited penetration of optical photons into tissue.

Figure 1.

Size dependent gold nanoparticle extinction spectra. Plasmon absorption depends on nanoparticle size and composition; shown are the extinction spectra of solid gold nanoparticles (black = 10 nm dia., red = 100 nm dia., blue = 150 nm dia.) and the red shifted silica core gold nanoshell spectrum (green = 150 nm dia.). Nanoparticle illustrations above each corresponding spectra are drawn to relative scale and spectra have been normalized to ease viewing of relative peak positions.

Nonetheless, the NIR absorptions of nanoshells has been used to heat nanoshells within cancer cells and within tumors [55] and have been shown to be efficacious in the treatment of superficial tumors. A clinical trial using gold-silica nanoshell hyperthermia following NIR light exposure has been initiated for patients with oropharyngeal malignancies. NIR photothermal therapy can treat superficial tumors but cannot be used to treat deeper organ-based cancers due to the significant attenuation of NIR light by the body's cellular matrix and biomolecular chromophoric absorptions [56]. Acute or long-term toxicities associated with administration of gold nanoshells or solid gold nanoparticles is not known but is currently being investigated in preclinical studies and phase I human clinical trials.

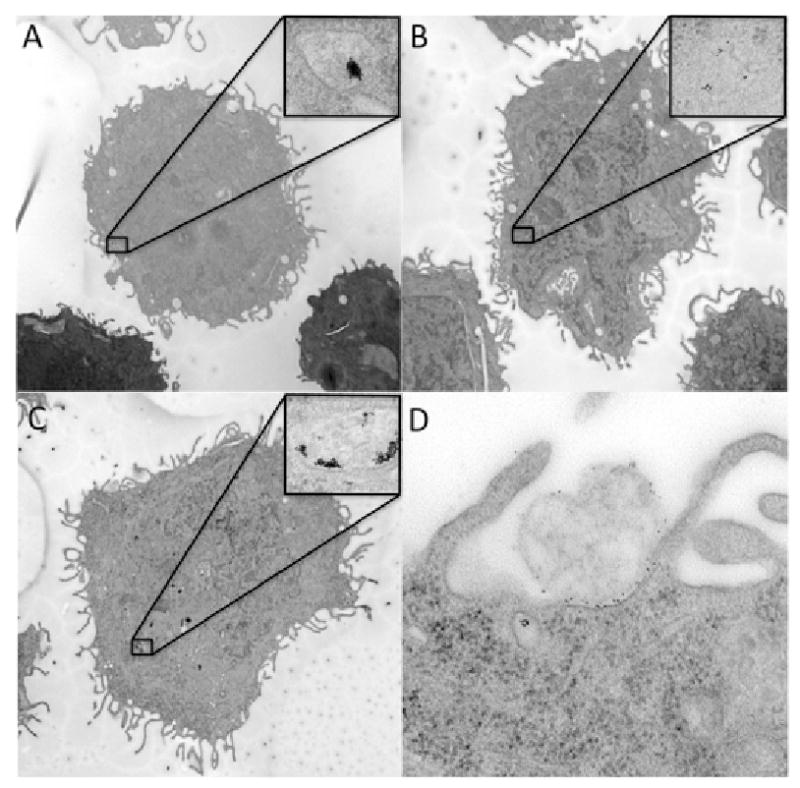

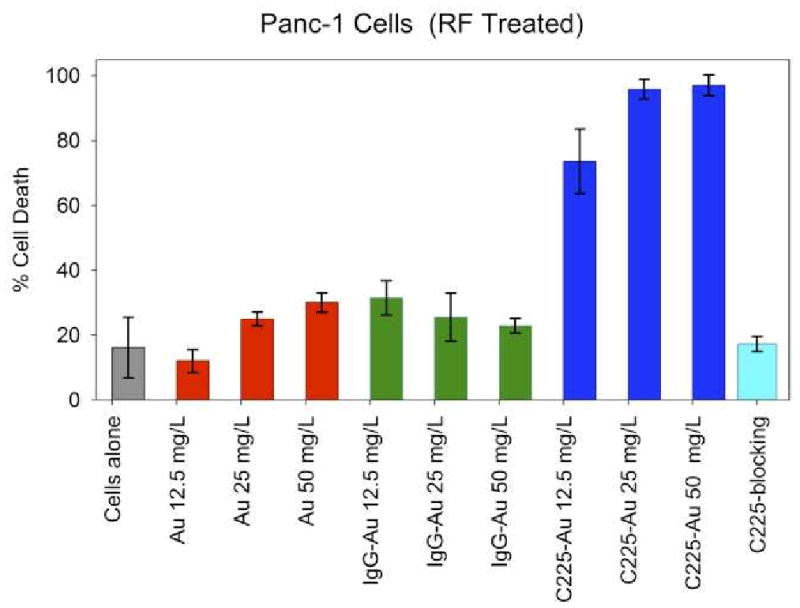

Recently, our group found that gold nanoparticles heat under shortwave radiofrequency fields [57, 58] Non-resonant RF fields resistively heat metals with the highest measured dissipative power (∼ 300,000 W/g of gold). By labeling gold nanoparticles with antibodies against cancer cells, higher concentrations of gold nanoparticles can be achieved (Figure 2). Once the particles are internalized, RF fields applied to cells results in localized heat and killing of cancer cells (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

TEM images of gold nanoparticles targeted against PANC-1 cancer cells incubated for 30 minutes. A. Gold nanoparticles without antibody labels show poor internalization. B. Gold nanoparticles labeled with IgG antibodies that are nonspecific for cancer cells show low uptake. C. Gold nanoparticles labeled with C225 (cetuximab) antibodies show pronounced internalization in cells. D. Magnified 100,000×, PANC-1 cells with gold nanoparticles at the periphery of the cells.

Figure 3.

RF induced hyperthermia of cells targeted with gold nanoparticles and exposed to two-minutes RF field treatment. Treatment of Panc-1 cells with RF alone (gray bar) produced low levels of cytotoxicity. Cells treated with either unlabeled gold nanoparticles (red bars) or IgG-conjugated gold nanoparticles (green bars) were also not associated with marked increases in RF-induced thermal cytotoxicity. Treatment of Panc-1 cells with C225-conjugated gold nanoparticles (dark blue bars) led to marked enhancement in RF-induced thermal cytotoxicity, which correlated to the increased intracytoplasmic vesicles seen in Figure 3. The enhanced cytotoxicity observed with C225-conjugated gold nanoparticles was completely blocked by first incubating Panc-1 cells with C225 alone (not conjugated to gold nanoparticles) 30 minutes prior to adding the C225-conjugated gold nanoparticles (light blue bar).

4.3 Carbon nanotubes

Single walled carbon nanotubes (SWNTs) have a wide dynamic range of electromagnetic absorptions that arise from their one dimensional structure which consists of a honeycomb pattern of carbon that is rolled into a seamless cylinder forming a thin cylindrical form of carbon. The conductivity of carbon nanotubes is determined by the crystalline arrangement of carbon of the cylindrical wall. Nanotubes are either metallic or semiconducting depending on the twist in the graphitic carbon wall. The absorption characteristics of carbon nanotubes have been utilized as hyperthermic enhancers [59] using NIR absorptions. Recently we have found that carbon nanotubes absorb significantly with intense heat release under capacitively-coupled radiofrequency fields similar to gold nanoparticles [57].

The thermal properties of SWNTs under RF fields have been used to treat deep tissue tumors given the property of RF to penetrate deep into tissue and release tremendous heat that is sufficient to induce apoptosis or necrosis [57]. Carbon nanotubes are capable of being targeted and delivered to specific cells either through direct covalent fictionalization or through noncovalent wrapping of targeting moieties.

5. Conclusions

Applications of nanotechnology in biomedicine are developing rapidly. Nanoparticles will likely be a critical tool to enhance the delivery of drugs and biological agents that improve and simplify laboratory tests to enhance the quality of imaging studies and as actual therapeutic targets. The property of heat generation upon exposure to electromagnetic fields will lead to use of nanoparticles to treat both malignant and nonmalignant human disease. Significant work on targeted delivery of nanoparticles to cancer, or other disease cells must be performed in addition to rigorous assessment of any acute of chronic toxicities related to the nanoparticles themselves.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Link S, El-Sayed MA. Optical properties and ultrafast dynamics of metallic nanocrystals. Annu Rev Phys Chem. 2003;54:331–66. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physchem.54.011002.103759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hartman KB, Wilson LJ, Rosenblum MG. Detecting and treating cancer with nanotechnology. Mol Diagn Ther. 2008;12:1–14. doi: 10.1007/BF03256264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sumer B, Gao J. Theranostic nanomedicine for cancer. Nanomed. 2008;3:137–40. doi: 10.2217/17435889.3.2.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cho K, Wang X, Nie S, Chen ZG, Shin DM. Therapeutic nanoparticles for drug delivery in cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:1310–6. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-1441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hartman KB, Wilson LJ. Carbon nanostructures as a new high-performance platform for MR molecular imaging. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2007;620:74–84. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-76713-0_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang A, Li S. Hydroxycamptothecin-loaded nanoparticles enhance target drug delivery and anticancer effect. BMC Biotechnol. 2008;8:46. doi: 10.1186/1472-6750-8-46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li S, Wang A, Jiang W, Guan Z. Pharmacokinetic characteristics and anticancer effects of 5-fluorouracil loaded nanoparticles. BMC Cancer. 2008;8:103. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-8-103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hwang HY, Kim IS, Kwon IC, Kim YH. Tumor targetability and antitumor effect of docetaxel-loaded hydrophobically modified glycol chitosan nanoparticles. J Control Release. 2008;128:23–31. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2008.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Patra CR, Bhattacharya R, Wang E, Katarya A, Lau JS, Dutta S, Muders M, Wang S, Buhrow SA, Safgren SL, Yaszemski MJ, Reid JM, Ames MM, Mukherjee P, Mukhopadhyay D. Targeted delivery of gemcitabine to pancreatic adenocarcinoma using cetuximab as a targeting agent. Cancer Res. 2008;68:1970–8. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-6102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Visaria RK, Griffin RJ, Williams BW, Ebbini ES, Paciotti GF, Song CW, Bischof JC. Enhancement of tumor thermal therapy using gold nanoparticle-assisted tumor necrosis factor-alpha delivery. Mol Cancer Ther. 2006;5:1014–20. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-05-0381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Farma JM, Puhlmann M, Soriano PA, Cox D, Paciotti GF, Tamarkin L, Alexander HR. Direct evidence for rapid and selective induction of tumor neovascular permeability by tumor necrosis factor and a novel derivative, colloidal gold bound tumor necrosis factor. Int J Cancer. 2007;120:2474–80. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Richard C, de Chermont Qle M, Scherman D. Nanoparticles for imaging and tumor gene delivery. Tumori. 2008;94:264–70. doi: 10.1177/030089160809400219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Opanasopit P, Apirakaramwong A, Ngawhirunpat T, Rojanarata T, Ruktanonchai U. Development and characterization of pectinate micro/nanoparticles for gene delivery. AAPS PharmSciTech. 2008;9:67–74. doi: 10.1208/s12249-007-9007-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kam NW, Liu Z, Dai H. Carbon nanotubes as intracellular transporters for proteins and DNA: an investigation of the uptake mechanism and pathway. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2006;45:577–81. doi: 10.1002/anie.200503389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chang MY, Shiau AL, Chen YH, Chang CJ, Chen HH, Wu CL. Increased apoptotic potential and dose-enhancing effect of gold nanoparticles in combination with single-dose clinical electron beams on tumor-bearing mice. Cancer Sci. 2008;99:1479–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2008.00827.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mukherjee P, Bhattacharya R, Bone N, Lee YK, Patra CR, Wang S, Lu L, Secreto C, Banerjee PC, Yaszemski MJ, Kay NE, Mukhopadhyay D. Potential therapeutic application of gold nanoparticles in B-chronic lymphocytic leukemia (BCLL): enhancing apoptosis. J Nanobiotechnology. 2007;5:4. doi: 10.1186/1477-3155-5-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mukherjee P, Bhattacharya R, Wang P, Wang L, Basu S, Nagy JA, Atala A, Mukhopadhyay D, Soker S. Antiangiogenic properties of gold nanoparticles. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:3530–4. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-2482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kou G, Wang S, Cheng C, Gao J, Li B, Wang H, Qian W, Hou S, Zhang D, Dai J, Gu H, Guo Y. Development of SM5-1-conjugated ultrasmall superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles for hepatoma detection. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008 doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.06.126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Barcena C, Sra AK, Chaubey GS, Khemtong C, Liu JP, Gao J. Zinc ferrite nanoparticles as MRI contrast agents. Chem Commun (Camb) 2008:2224–6. doi: 10.1039/b801041b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Neumaier CE, Baio G, Ferrini S, Corte G, Daga A. MR and iron magnetic nanoparticles. Imaging opportunities in preclinical and translational research. Tumori. 2008;94:226–33. doi: 10.1177/030089160809400215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu Z, Cai W, He L, Nakayama N, Chen K, Sun X, Chen X, Dai H. In vivo biodistribution and highly efficient tumour targeting of carbon nanotubes in mice. Nat Nanotechnol. 2007;2:47–52. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2006.170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Matson JB, Grubbs RH. Synthesis of fluorine-18 functionalized nanoparticles for use as in vivo molecular imaging agents. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:6731–3. doi: 10.1021/ja802010d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang H, Yee D, Wang C. Quantum dots for cancer diagnosis and therapy: biological and clinical perspectives. Nanomed. 2008;3:83–91. doi: 10.2217/17435889.3.1.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Misra RD. Quantum dots for tumor-targeted drug delivery and cell imaging. Nanomed. 2008;3:271–4. doi: 10.2217/17435889.3.3.271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Curry AC, Crow M, Wax A. Molecular imaging of epidermal growth factor receptor in live cells with refractive index sensitivity using dark-field microspectroscopy and immunotargeted nanoparticles. J Biomed Opt. 2008;13:014022. doi: 10.1117/1.2837450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kelly KA, Setlur SR, Ross R, Anbazhagan R, Waterman P, Rubin MA, Weissleder R. Detection of early prostate cancer using a hepsin-targeted imaging agent. Cancer Res. 2008;68:2286–91. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-1349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wu J, Yan F, Zhang X, Yan Y, Tang J, Ju H. Disposable Reagentless Electrochemical Immunosensor Array Based on a Biopolymer/Sol-Gel Membrane for Simultaneous Measurement of Several Tumor Markers. Clin Chem. 2008 doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2007.102350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Simberg D, Duza T, Park JH, Essler M, Pilch J, Zhang L, Derfus AM, Yang M, Hoffman RM, Bhatia S, Sailor MJ, Ruoslahti E. Biomimetic amplification of nanoparticle homing to tumors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:932–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0610298104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Javier DJ, Nitin N, Levy M, Ellington A, Richards-Kortum R. Aptamer-targeted gold nanoparticles as molecular-specific contrast agents for reflectance imaging. Bioconjug Chem. 2008;19:1309–12. doi: 10.1021/bc8001248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Farokhzad OC, Jon S, Khademhosseini A, Tran TN, Lavan DA, Langer R. Nanoparticle-aptamer bioconjugates: a new approach for targeting prostate cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2004;64:7668–72. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-2550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Berry CC. Intracellular delivery of nanoparticles via the HIV-1 tat peptide. Nanomed. 2008;3:357–65. doi: 10.2217/17435889.3.3.357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Berry CC, de la Fuente JM, Mullin M, Chu SW, Curtis AS. Nuclear localization of HIV-1 tat functionalized gold nanoparticles. IEEE Trans Nanobioscience. 2007;6:262–9. doi: 10.1109/tnb.2007.908973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Field SB, Bleehen NM. Hyperthermia in the treatment of cancer. Cancer treatment reviews. 1979;6:63–94. doi: 10.1016/s0305-7372(79)80043-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Milleron RS, Bratton SB. ‘Heated’ debates in apoptosis. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2007;64:2329–33. doi: 10.1007/s00018-007-7135-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wust P, Hildebrandt B, Sreenivasa G, Rau B, Gellermann J, Riess H, Felix R, Schlag PM. Hyperthermia in combined treatment of cancer. The lancet oncology. 2002;3:487–97. doi: 10.1016/s1470-2045(02)00818-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hildebrandt B, Wust P, Ahlers O, Dieing A, Sreenivasa G, Kerner T, Felix R, Riess H. The cellular and molecular basis of hyperthermia. Critical reviews in oncology/hematology. 2002;43:33–56. doi: 10.1016/s1040-8428(01)00179-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Curley SA. Radiofrequency ablation of malignant liver tumors. Ann Surg Oncol. 2003;10:338–47. doi: 10.1245/aso.2003.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ellis LM, Tanabe KK. Radiofrequency ablation for cancer In: Current Indication, Techniques, and Outcomes. 1st. New York: Springer-Verlag; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Issels RD. Hyperthermia adds to chemotherapy. Eur J Cancer. 2008;44:2546–54. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.07.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Witkamp AJ, de Bree E, Van Goethem R, Zoetmulder FA. Rationale and techniques of intra-operative hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy. Cancer treatment reviews. 2001;27:365–74. doi: 10.1053/ctrv.2001.0232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Noorda EM, Vrouenraets BC, Nieweg OE, van Coevorden F, van Slooten GW, Kroon BB. Isolated limb perfusion with tumor necrosis factor-alpha and melphalan for patients with unresectable soft tissue sarcoma of the extremities. Cancer. 2003;98:1483–90. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lienard D, Eggermont AM, Kroon BB, Schraffordt Koops H, Lejeune FJ. Isolated limb perfusion in primary and recurrent melanoma: indications and results. Seminars in surgical oncology. 1998;14:202–9. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-2388(199804/05)14:3<202::aid-ssu3>3.0.co;2-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bartlett DL, Ma G, Alexander HR, Libutti SK, Fraker DL. Isolated limb reperfusion with tumor necrosis factor and melphalan in patients with extremity melanoma after failure of isolated limb perfusion with chemotherapeutics. Cancer. 1997;80:2084–90. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19971201)80:11<2084::aid-cncr7>3.0.co;2-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.van der Zee J, Gonzalez Gonzalez D, van Rhoon GC, van Dijk JD, van Putten WL, Hart AA. Comparison of radiotherapy alone with radiotherapy plus hyperthermia in locally advanced pelvic tumours: a prospective, randomised, multicentre trial. Dutch Deep Hyperthermia Group. Lancet. 2000;355:1119–25. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(00)02059-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vernon CC, Hand JW, Field SB, Machin D, Whaley JB, van der Zee J, van Putten WL, van Rhoon GC, van Dijk JD, Gonzalez Gonzalez D, Liu FF, Goodman P, Sherar M. Radiotherapy with or without hyperthermia in the treatment of superficial localized breast cancer: results from five randomized controlled trials. International Collaborative Hyperthermia Group. International journal of radiation oncology, biology, physics. 1996;35:731–44. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(96)00154-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Murakami R, Yoshimatsu S, Yamashita Y, Matsukawa T, Takahashi M, Sagara K. Treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma: value of percutaneous microwave coagulation. Ajr. 1995;164:1159–64. doi: 10.2214/ajr.164.5.7717224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Curley SA. Radiofrequency ablation of malignant liver tumors. The oncologist. 2001;6:14–23. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.6-1-14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lygidakis NJ, Sharma SK, Papastratis P, Zivanovic V, Kefalourous H, Koshariya M, Lintzeris I, Porfiris T, Koutsiouroumba D. Microwave ablation in locally advanced pancreatic carcinoma--a new look. Hepato-gastroenterology. 2007;54:1305–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Curley SA, Izzo F, Ellis LM, Nicolas Vauthey J, Vallone P. Radiofrequency ablation of hepatocellular cancer in 110 patients with cirrhosis. Annals of surgery. 2000;232:381–91. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200009000-00010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Curley SA, Marra P, Beaty K, Ellis LM, Vauthey JN, Abdalla EK, Scaife C, Raut C, Wolff R, Choi H, Loyer E, Vallone P, Fiore F, Scordino F, De Rosa V, Orlando R, Pignata S, Daniele B, Izzo F. Early and late complications after radiofrequency ablation of malignant liver tumors in 608 patients. Annals of surgery. 2004;239:450–8. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000118373.31781.f2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Matlaga BR, Zagoria RJ, Woodruff RD, Torti FM, Hall MC. Phase II trial of radio frequency ablation of renal cancer: evaluation of the kill zone. The Journal of urology. 2002;168:2401–5. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(05)64154-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jeffrey SS, Birdwell RL, Ikeda DM, Daniel BL, Nowels KW, Dirbas FM, Griffey SM. Radiofrequency ablation of breast cancer: first report of an emerging technology. Arch Surg. 1999;134:1064–8. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.134.10.1064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kalambur VS, Longmire EK, Bischof JC. Cellular level loading and heating of superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles. Langmuir. 2007;23:12329–36. doi: 10.1021/la701100r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Samanta B, Yan H, Fischer NO, Shi J, Jerry DJ, Rotello VM. Protein-passivated Fe3O4 nanoparticles: Low toxicity and rapid heating for thermal therapy. J Mat Chem. 2008;18:1204–1208. doi: 10.1039/b718745a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gobin AM, Lee MH, Halas NJ, James WD, Drezek RA, West JL. Near-infrared resonant nanoshells for combined optical imaging and photothermal cancer therapy. Nano Lett. 2007;7:1929–34. doi: 10.1021/nl070610y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Arnfield MR, Mathew RP, Tulip J, McPhee MS. Analysis of tissue optical coefficients using an approximate equation valid for comparable absorption and scattering. Phys Med Biol. 1992;37:1219–30. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/37/6/002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gannon CJ, Patra CR, Bhattacharya R, Mukherjee P, Curley SA. Intracellular gold nanoparticles enhance non-invasive radiofrequency thermal destruction of human gastrointestinal cancer cells. J Nanobiotechnology. 2008;6:2. doi: 10.1186/1477-3155-6-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Curley SA, Cherukuri P, Briggs K, et al. Noninvasive radiofrequency field-induced hyperthermic cytotoxicity in human cancer cells using cetuximab-targeted gold nanoparticles. J Exp Ther Onc. 2008;7:313–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kam NW, O'Connell M, Wisdom JA, Dai H. Carbon nanotubes as multifunctional biological transporters and near-infrared agents for selective cancer cell destruction. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2005;102(33):11600–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0502680102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]