Abstract

OBJECTIVE:

To determine whether a population of pregnant women with group B streptococcal (GBS) vaginal colonization had an increased risk of specific epidemiological and intrapartum risk factors for early onset GBS disease.

SETTING:

Tertiary university centre in Ottawa, Ontario.

DESIGN:

Hospital-based retrospective cohort study.

METHODS:

Pregnant women who gave birth during a four-month period in 1994 were included in the study. Potential GBS risk factors were obtained from a review of medical records. The prevalence of each risk factor in colonized and noncolonized women was examined using χ2 or Fisher’s exact test. Multiple logistic regression was performed.

RESULTS:

A total of 986 women, including 94 (9.5%) women colonized with GBS, were studied. The proportion of women younger than 20 years of age in the colonized group was 2.1% (two of 94) versus 4.6% (41 of 891) in the noncolonized group (P=0.28). Similar rates of multiple births were observed among the colonized and noncolonized groups (2.1% [two of 94] versus 2.5% [22 of 891], respectively) (P=0.94). Likewise, there were no significant differences in either group in the prevalence of a previous pregnancy affected by GBS or diabetes mellitus (P=0.82 and P=0.79, respectively). Multivariable analyses indicated that women who were colonized with GBS were more than twice as likely to deliver prematurely (below 37 weeks’ gestational age) (odds ratio [OR] 2.43, 95% CI 1.39 to 4.23). Similarly, colonized women were more likely to be febrile during labour (at least 38°C) (OR 5.05, 95% CI 1.70 to 15.02).

CONCLUSION:

GBS vaginal colonization was associated with premature labour and intrapartum pyrexia in the population studied. According to Canadian and American guidelines, women with GBS vaginal colonization qualify for intrapartum chemoprophylaxis. The study results suggest that the identification of women at risk of premature labour may be one advantage of early prenatal screening for GBS.

Keywords: Pregnancy, Prematurity, Streptococcus agalactiae

Abstract

OBJECTIF:

Établir si une population de femmes enceintes présentant une colonisation vaginale par des streptocoques de groupe B (SGB) courait un risque plus élevé de présenter des facteurs de risque épidémiologiques et intrapartum spécifiques de maladie à SGB précoce.

EMPLACEMENT:

Centre universitaire de soins tertiaires à Ottawa, en Ontario.

MÉTHODOLOGIE:

Étude rétrospective de cohortes en milieu hospitalier.

MÉTHODES:

Les femmes enceintes qui ont accouché pendant un intervalle de quatre mois en 1994 ont été incluses dans l’étude. Les facteurs de SGB potentiels ont été obtenus grâce à un examen des dossiers médicaux. La prévalence de chaque facteur de risque chez les femmes colonisées et non colonisées a été évaluée, d’après χ2 ou la méthode exacte de Fisher. Une fonction logistique a été effectuée.

RÉSULTATS:

Au total, 986 femmes, dont 94 (9,5 %) étaient colonisées par le SGB, ont été étudiées. La proportion de femmes de moins de 20 ans au sein du groupe colonisé s’établissait à 2,1 % (deux sur 94) par rapport à 4,6 % (41 sur 891) au sein du groupe non colonisé (P=0,28). Des taux similaires de naissances multiples ont été observés parmi les groupes colonisés et non colonisés (2,1 % [deux sur 94] par rapport à 2,5 % [22 sur 891], respectivement) (P=0,94). De même, il n’existait aucune différence significative dans chaque groupe pour ce qui est de la prévalence de grossesses précédentes touchées par le SGB ou le diabète sucré (P=0,82 et P=0,79, respectivement). Les analyses multivariables indiquent que le risque que les femmes colonisées par le SGB accouchent prématurément (à moins de 37 semaines d’âge gestationnel) (risque relatif [RR] de 2,43, 95 % IC 1,39 à 4,23) était plus de deux fois plus élevé. De même, les femmes colonisées étaient plus susceptibles de faire de la fièvre pendant le travail (au moins 38 °C) (RR de 5,05, 95 % IC 1,70 à 15,02).

CONCLUSION:

La colonisation vaginale par des SGB s’associait à un travail prématuré et à une pyrexie intrapartum dans la population étudiée. D’après les directives canadiennes et américaines, les femmes présentant une colonisation vaginale par des SGB sont admissibles à une chimioprophylaxie intrapartum. Les résultats de l’étude laissent supposer que l’identification des femmes à risque de travail prématuré peut constituer un avantage du dépistage précoce des SGB.

Group B streptococci (GBS) (Streptococcus agalactiae) remain of concern as a significant cause of perinatal and maternal disease (1). The case fatality rate among GBS-infected newborns ranges from 5% to 20% (1–4). These figures represent an improvement in mortality rates over previous years that is attributed to advances in neonatal care. Preventive strategies have focused primarily on infants at high risk of early onset disease (defined as GBS acquired before seven days of age) (5–9). GBS is a significant cause of peripartum sepsis among colonized pregnant women (5,10–14).

Factors associated with an increased likelihood of early onset GBS include maternal age younger than 20 years, low socioeconomic status, a previous GBS-affected newborn, premature delivery (less than 37 weeks gestational age), prolonged rupture of membranes (at least 18 h), maternal intrapartum pyrexia (at least 38°C), multiple pregnancy, GBS bacteriuria and the degree of vaginal colonization (heavy versus light) (15–19). It has been suggested that GBS vaginal colonization may be associated with preterm labour (18,19). However, unlike the relationship between GBS bacteriuria and preterm labour, the association between vaginal colonization and preterm labour is inconclusive (15,18).

The present study examines the relationship between GBS vaginal colonization and published risk factors for early onset GBS disease to determine whether GBS vaginal colonization in the study population was associated with any of the risk factors indicated above.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

A retrospective cohort study of all pregnant women who had consecutive deliveries at the Ottawa General Hospital, Ottawa during a four-month period in 1994 was conducted. During 1994, all pregnant women seen at the hospital were routinely screened for GBS early in the third trimester (26 to 28 weeks’ gestational age). Ottawa General Hospital is a 402-bed teaching institution that serves residents of eastern Ontario and western Quebec. Almost 3000 newborns are delivered at the hospital each year.

Microbiological methods

Vaginal or vaginal-anorectal swabs were transported to the microbiology laboratory at the Ottawa General Hospital in modified Amies transport media (Starplex Scientific, Etobicoke, Ontario) where they were placed into GBS broth (Lim broth, PML Microbiologicals, Mississauga, Ontario) within 6 to 12 h of collection. Lim broth is one of the recommended selective GBS media (8). After incubation at 35°C for 16 to 18 h, the broths were subcultured onto 5% sheep blood agar plates (Becton Dickinson Microbiology Systems, Cockeysville, Maryland). These plates were incubated at 35°C in 5% carbon dioxide, and examined after 24 and 48 h. Colonies suggestive of GBS were confirmed using latex agglutination (PathoDx Streptococcus Grouping, Diagnostic Products Corporation, Los Angeles, California).

Data extraction and statistical analyses

The relevant epidemiological and clinical data were obtained by a review of medical records. Proportions were compared in univariate analyses using χ2 and Fisher’s exact tests where indicated (20). Multivariable analyses were conducted using a multiple logistic regression approach (Statistical Analysis System, SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina). In addition to the relationship between colonization and risk factors for GBS, the impact that independent variables such as age, multiple births and diabetes had on the intrapartum risk factors (premature labour, intrapartum pyrexia and prolonged rupture of membranes) was examined.

RESULTS

Of 986 pregnant women evaluated during the study period, the prevalence of GBS colonization was 9.5%. The median age of the group was 29.0 years; 4.4% of the women were younger than 20 years of age. Table 1 shows the prevalence of epidemiological and intrapartum risk factors for GBS disease among colonized and noncolonized women. The groups were comparable with respect to the presence of known epidemiological risk factors for GBS disease, including age younger than 20 years, multiple births and the delivery of a previous GBS-infected newborn.

TABLE 1:

Univariate analyses comparing the prevalence of risk factors for early onset group B streptococcus (GBS) among pregnant women with and pregnant women without GBS colonization

| Variables | Colonized women (n=94) | Noncolonized women (n=892) | Odds ratio | 95% CI | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age younger than 20 years | 2 | 41 | 0.45 | 0.11 to 1.89 | 0.28 |

| Multiple births | 2 | 22 | 0.95 | 0.22 to 4.11 | 0.94 |

| Diabetes | 6 | 41 | 1.14 | 0.44 to 2.94 | 0.79 |

| Previous GBS-infected newborn | 3 | 15 | 1.19 | 0.27 to 5.25 | 0.82 |

| GBS bacteriuria | 1 | 0 | – | – | – |

| Preterm delivery (less than 37 weeks’ gestational age) | 21 | 95 | 2.24 | 1.31 to 3.83 | 0.003 |

| Intrapartum fever (at least 38°C) | 4 | 12 | 4.94 | 1.66 to 14.57 | 0.004 |

| Prolonged rupture of membranes (at least 18 h) | 10 | 27 | 2.73 | 1.31 to 5.68 | 0.007 |

In the univariate analyses (Table 1), the colonized group was significantly more likely to have women who had premature labour (less than 37 weeks’ gestational age, odds ratio [OR] 2.24, 95% CI 1.31 to 3.83). Similarly, colonized women were more likely to have prolonged rupture of membranes (18 h or more) and fever (at least 38°C) compared with those who were not colonized (OR 2.73, 95% CI 1.31 to 5.68 and OR 4.92, 95% CI 1.66 to 14.57, respectively)

In a multivariable model containing colonization, multiple births, diabetes and age younger than 20 years, GBS colonization remained independently associated with prematurity (OR 2.43, 95% CI 1.39 to 4.23). Women with multiple births were more likely to deliver prematurely compared with those without multiple births (OR 16.42, 95% CI 6.65 to 40.57), while those with diabetes showed a trend towards significantly more premature deliveries compared with those without diabetes (OR 2.10, 95% CI 0.98 to 4.52).

Multivariable analyses using intrapartum fever as a dependent variable were also conducted. When age younger than 20 years, multiple births, diabetes and colonization were included in a model with intrapartum fever as the dependent variable, pregnant women who were colonized were about five times more likely to be febrile in labour compared with those who were not colonized (OR 5.05, 95% CI 1.70 to 15.02). Low cell numbers limited the extent of similar analyses using prolonged rupture of membranes as the dependent variable.

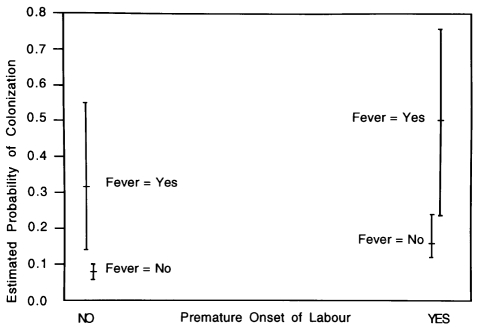

Given that the current practice is to offer intrapartum penicillin to women with premature onset of labour and intrapartum fever in the absence of information on the GBS colonization status, the ability of intrapartum fever and premature onset of labour to predict the presence of GBS vaginal colonization was also examined (Figure 1). Women with intrapartum fever and premature labour were about three times more likely to be colonized with GBS compared with those who had premature labour but no intrapartum fever (Figure 1). Likewise, the estimated probability of colonization was significantly lower if intra-partum fever and premature labour were not experienced.

Figure 1).

Estimated probability of colonization in relation to the presence or absence of premature onset of labour and intrapartum fever. Point estimates are indicated by a short horizontal bar (–), while the 95% CIs are indicated by the vertical lines

DISCUSSION

In this study, we have demonstrated that GBS vaginal colonization was independently associated with premature onset of labour and intrapartum pyrexia. An association between colonization and prolonged rupture of membranes was also demonstrated in the univariate analyses. Compared with women without GBS vaginal colonization, those with GBS colonization were about twice as likely to have premature onset of labour.

While the relationship between GBS bacteriuria and premature labour has been well established (19), this has not been the case with GBS vaginal colonization. In this regard, the results of studies have been contradictory (15,18,21–26). Among the studies on this issue, McDonald et al (18) demonstrated that pregnant carriers of GBS had a significantly increased risk of premature labour and prolonged rupture of membranes. Similar findings have been reported from Spain (21) and the United States (26). In a study by Regan et al (22), the investigators showed that heavy GBS colonization was associated with low birth weight, preterm deliveries. However, in a large study of patients by Boyer et al (15), no relationship between vaginal colonization and premature labour was demonstrated.

The finding of an association between vaginal colonization and premature labour, intrapartum fever and, to a lesser extent, prolonged rupture of membranes does not necessarily imply that GBS caused intrapartum infection and premature onset of labour. GBS vaginal colonization may merely have been an indicator of the presence of some other factor which, in turn, may be associated with premature labour and intrapartum fever. In this context, our study was not able to evaluate the possible role of GBS bacteriuria, an entity known to be associated with heavy vaginal colonization. GBS bacteriuria was documented in only one colonized patient (less than 1%). In two of the more frequently cited papers on the association between GBS colonization and premature labour (18,19), the prevalence of GBS bacteriuria was 1.7% and 4.0%, respectively. GBS bacterium is likely to be more prevalent than documented in our study because asymptomatic bacteriuria could be missed unless multiple urine screens for GBS are performed.

The results of our study do not justify routine early antenatal screening for the purposes of intrapartum GBS prophylaxis. This is due to the fact that as far as intrapartum GBS prophylaxis is concerned, the revised American guidelines (8) as well as Canadian guidelines (7,9) employ strategies that recommend offering intrapartum prophylaxis to women who go into premature labour. However, the fact that colonization may indicate an increased risk of premature labour and intrapartum pyrexia may be of value to obstetricians managing certain categories of pregnant women, such as those with high risk pregnancies. It should be noted, however, that a study by Klebanoff et al (27) showed that treating colonized women with erythromycin did not prolong gestation or reduce low birth weight deliveries.

We observed a relatively low rate of GBS colonization in this study (9.5%). Colonization rates vary from less than 5% to 49% (16). However, this reported range is likely due to differences in culture techniques. The method of detection and culture techniques employed in our study are recommended by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, Georgia (8). If for some reason our technique resulted in a low detection rate, it would likely affect all patients in the cohort because the same approach was used for all. However, it is likely that a relatively insensitive method of detection would more likely detect heavy colonization and miss light colonization. Therefore, in a worst case scenario, if our methods only detected heavy colonization, the results would at least support an association between heavy vaginal colonization and premature onset of labour, intrapartum pyrexia and prolonged rupture of membranes.

Our study is affected by the known limitations of retrospective studies. Potentially significant biases include those that may systematically result in proportionately more women with premature labour and intrapartum fever being assigned to the group with vaginal colonization. This is unlikely given that the institution employed a uniform screening approach for all pregnant women. Chance imbalance may have led to faulty conclusions if some factor that is associated with the dependent variable (eg, premature onset of labour) was disproportionately represented in the group of colonized pregnant women (28). In this study, such an imbalance would have had to simultaneously affect three variables, premature onset of labour, prolonged rupture of membranes and intrapartum pyrexia. In addition, the results are consistent with some of the studies in other populations. In this regard, we concur with Mercer and Arheart (29) that “there is increasing evidence to suggest vaginal GBS carriage as a potential marker of prematurity.”

CONCLUSIONS

The data from the present preliminary study suggest that, in the population studied, GBS vaginal colonization was associated with premature labour, intrapartum pyrexia and prolonged rupture of membranes. Thus, the determination of GBS colonization before the onset of labour is helpful in identifying women who are likely to have the above intrapartum complications. The study also supports the use of chemoprophylaxis based on risk factors if GBS screening is not available. Women with intrapartum risk factors, particularly fever and premature labour, were shown to have an increased likelihood of GBS vaginal colonization.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Laurie Greenberg and Mary Lou Semple for their assistance with this study.

Footnotes

Presented in part at the 37th Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy, Toronto, from September 28 to October 1, 1997

REFERENCES

- 1.Baker CJ, Edwards MS. Group B streptococcal infections. In: Remmington J, Klein JO, editors. Infectious Diseases of the Fetus and Newborn Infant. 4th edn. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1995. pp. 980–1054. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weisman LE, Stoll BJ, Cruess DF, et al. Early-onset group B streptococcal sepsis: a current assessment. J Pediatr. 1992;121:428–33. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(05)81801-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zangwill KM, Schuchat A, Wenger JD. Group B streptococcal disease in the United States, 1990: report from a multistate active surveillance system. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep CDC Surveill Summ. 1992;41:25–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Davies HD, Leblanc J, McGeer A, Bortolussi R, PICNIC PICNIC study of the clinical manifestations and outcomes of neonatal group B streptococcal (GBS) disease in Canada Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and ChemotherapyNew OrleansSeptember 15 to 18, 1996(Abst K78) [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boyer KM, Gotoff SP. Prevention of early-onset neonatal group B streptococcal disease with selective intrapartum chemoprophylaxis. N Engl J Med. 1986;314:1665–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198606263142603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Allen UD, Navas L, King SM. Effectiveness of intrapartum penicillin prophylaxis in preventing early-onset group B streptococcal infection: results of a meta-analysis. CMAJ. 1993;149:1659–65. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Infectious Diseases and Immunization Committee and the Fetus and Newborn Committee, Canadian Paediatric Society and the Maternal Fetal Medicine Committee, The Society of Obstetrics and Gynecology of Canada National consensus statement on the prevention of early-onset group B streptococcal infections in the newborn. Can J Pediatr. 1994;1:247–53. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Prevention of perinatal group B streptococcal disease: a public health perspective. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1996;45:1–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Society of Obstetricians and Gynecologists of Canada Statement on the prevention of early-onset group B streptococcal infections in the newborn. J Soc Obstet Gynecol Can. 1997;19:419–20. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Minkoff HL, Sierra MF, Pringle GF, Schwarz RH. Vaginal colonization with group B beta-hemolytic streptococcus as a risk factor for post-cesarean section febrile morbidity. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1982;142:992–5. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(82)90781-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Faro S. Group B beta-hemolytic streptococci and puerperal infections. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1981;139:686–9. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(81)90486-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gibbs RS, Blanco JD. Streptococcal infections in pregnancy. A study of 48 bacteremias. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1981;140:405–11. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(81)90034-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Matorras R, Garcia-Perea A, Madero R, Usandizaga JA. Maternal colonization by group B streptococci and puerperal infection; analysis of intrapartum chemoprophylaxis. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1991;38:203–7. doi: 10.1016/0028-2243(91)90292-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Morales WJ, Lim D. Reduction of group B streptococcal maternal and neonatal infections in preterm pregnancies with premature rupture of membranes through a rapid identification test. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1987;157:13–6. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(87)80336-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Boyer KM, Gadzala CA, Burd LI, Fisher DE, Paton JB, Gotoff SP. Selective intrapartum chemoprophylaxis of neonatal group B streptococcal early-onset disease. I. Epidemiologic rationale. J Infect Dis. 1983;148:795–801. doi: 10.1093/infdis/148.5.795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schuchat A, Wenger JD. Epidemiology of group B streptococcal disease: risk factors, prevention strategies and vaccine development. Epidemiol Rev. 1994;16:374–402. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.epirev.a036159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schuchat A, Oxtoby M, Cochi S, et al. Population-based risk factors for neonatal group B streptococcal disease: results of a cohort study in metropolitan Atlanta. J Infect Dis. 1990;162:672–7. doi: 10.1093/infdis/162.3.672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McDonald H, Vigneswaran R, O’Loughlin JA. Group B streptococcal colonization and preterm labour. Aust NZ J Obstet Gynaecol. 1989;29:291–3. doi: 10.1111/j.1479-828x.1989.tb01745.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thomsen AC, Morup L. Antibiotic elimination of group-B streptococci in urine in prevention of preterm labour. Lancet. 1987;i:591–3. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(87)90234-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rosner B. Fundamentals of Biostatistics. 2nd edn. Boston: PWS Publishers; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 21.De Cueto M, Carillo MP, Puertas A, et al. The association of vaginal colonization by group B streptococci (GBS) with premature rupture of delivery and preterm labour 36th Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and ChemotherapyNew OrleansSeptember 15 to 18, 1996(Abst K75) [Google Scholar]

- 22.Regan JA, Chao S, James LS. Premature rupture of membranes, preterm delivery, and group B streptococcal colonization of mothers. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1981;141:184–6. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(16)32589-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Baker CJ, Barrett FF, Yow MD. The influence of advancing gestation on group B streptococcal colonization in pregnant women. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1975;122:820–3. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(75)90721-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lamont RF, Taylor-Robinson D, Newman M, Wigglesworth J, Elder MG. Spontaneous early preterm labour associated with abnormal genital bacterial colonization. Br J Obstet Gynecol. 1986;93:804–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1986.tb07987.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Romero R, Mazor JM, Oyarzun E, Sirtori M, Wu YK, Hobbins JC. Is there an association between colonization with group B streptococcus and prematurity? J Reprod Med. 1989;34:797–801. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hillier SL, Krohn MA, Thwin SS, Brown Z.The association of high-density vaginal colonization by group B streptococcus and preterm birth 35th Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and ChemotherapySan FranciscoSeptember 17 to 20, 1995(Abst K189) [Google Scholar]

- 27.Klebanoff MA, Regan JA, Rao AV, et al. Outcome of the vaginal infections and prematurity study: results of a clinical trial of erythromycin among pregnant women colonized with group B streptococci. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1995;172:1540–5. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(95)90493-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brennan P, Croft P. Interpreting the results of observational research: chance is not such a fine thing. BMJ. 1994;309:727–30. doi: 10.1136/bmj.309.6956.727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mercer BM, Arheart KL. Antibiotic therapy for preterm premature rupture of membranes. Semin Perinatol. 1996;20:426–38. doi: 10.1016/s0146-0005(96)80010-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]