Abstract

Purpose

The purpose of this study is to assess patient attitudes towards anti-glaucoma medication and their association with adherence, visual quality of life, and personality traits.

Materials and Methods

One hundred and forty-seven glaucoma patients were enrolled this study. The participants were divided into 'pharmacophobic' and 'pharmacophilic' groups according to their scores on the Modified Glaucoma Drug Attitude Inventory (MG-DAI). To establish a correlation with patient drug attitude, each group had their subjective drug adherence, visual quality of life, and personality traits examined. For personality traits, the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI) was used to sub-classify each group.

Results

Among the patients analyzed, 91 (72.80%) patients showed a 'pharmacophobic' attitude and 34 (27.20%) patients showed a 'pharmacophilic' attitude. The pharmacophobic group tended to have worse adherence than the pharmacophilic group. Personality dichotomies from the MBTI also showed different patterns for each group.

Conclusion

In glaucoma patients, pharmacological adherence was influenced by their attitude towards drugs; an association might exist between drug attitude and underlying personality traits.

Keywords: Adherence, drug attitude, glaucoma, personality

INTRODUCTION

Glaucoma is one of the most common causes of blindness in the industrialized world.1 The World Health Organization estimates that the global rates of glaucoma and glaucoma-related disability are above 6.4 million,1,2 and that by 2020 the number of cases will double to 12 million with an aging population.1

Glaucoma affects quality of life through visual deterioration as well as through its treatment, which can require a demanding, lifelong multi-drug regimen. However, given the asymptomatic nature of the disease, patients are provided little motivation to maintain this lifelong therapeutic regimen and are at a high risk of non-adherence.3

There have been few reports in the literature examining the reasons for poor adherence with anti-glaucoma medication. None of the common, intuitively determined factors such as age, gender, level of education, severity of the disease, and fear of blindness were found to consistently correlate with non-adherence.4-7 Factors hitherto found to have a correlation with non-adherence include patient's knowledge and poor understanding of the disease, increased regimen complexity, and problems in doctor-patient relationships.8-11 When it comes to adherence issues and psychiatric profiles in the management of glaucoma, personality structure has been correlated with acceptance of the disease and subsequent cooperation with treatment, while depression has been reported to be associated with glaucoma.12,13 Even though there are few studies investigating the association between the personality of glaucoma patients and their adherence, they are too complicated to apply directly for the routine clinical setting.

The aim of the present study was to assess patient attitude towards anti-glaucoma medication and its association with adherence, visual quality of life, and personality traits.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Participants

The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board, Severance Hospital, Yonsei University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea and adhered to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki. This cross-sectional study consecutively enrolled 147 confirmed glaucoma patients who were routinely managed for glaucoma by our department, or who were referred by primary ophthalmologists to confirm the diagnosis. We excluded patients with a previous history of acute angle-closure attack and other ophthalmic conditions that may affect the management of glaucoma. No participants had a history of psychotic illness, current alcohol and/or drug abuse, dementia, or had taken psychoactive drugs prior to the day they were interviewed. Baseline demographic and clinical information were collected for each participant.

Modified Glaucoma Drug Attitude Inventory (MG-DAI) classification

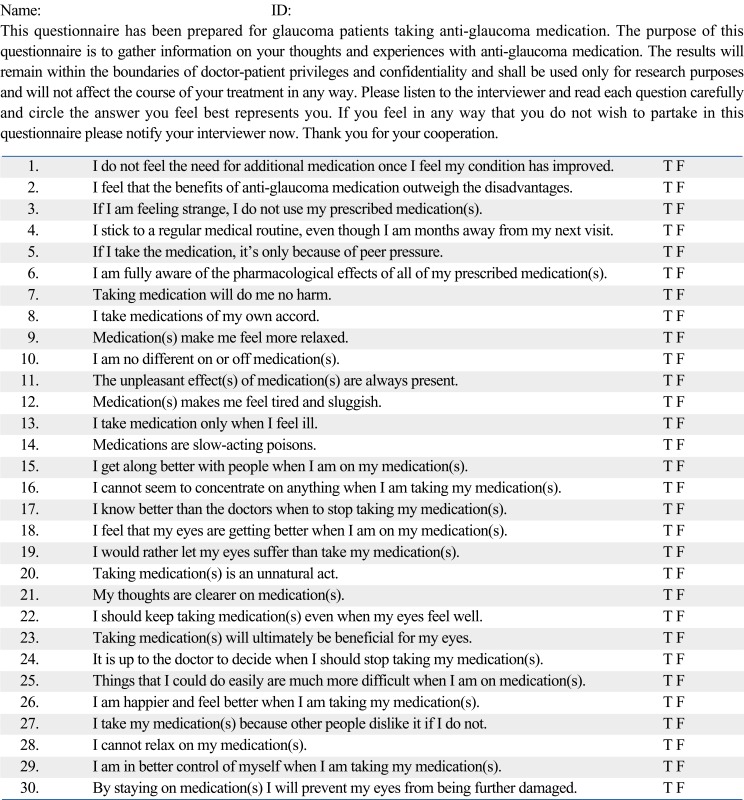

The drug attitude inventory (DAI) scale was originally invented for the purpose of categorizing patients taking anti-psychotic drugs based upon their attitudes towards medication (pharmacophilic vs. pharmacophobic).14,15 In this study, each item of the questionnaire was not only translated into Korean but was also modified for patients taking anti-glaucoma medication (Supplement 1). The item and factorial content, validity, and reliability of the DAI are described elsewhere.14 And all questionnaires were administered by a skilled research assistant.

The Modified Glaucoma Drug Attitude Inventory (MG-DAI) assigns scores of either +1 (positive attitude) or -1 (negative attitude) to each of the total 30 items, allowing the score total to range from -30 to +30. For every patient, it was ensured that each item was given a score. Those who had total scores of more than 0 were classified as "pharmacophilic" and those with negative scores were classified as "pharmacophobic".

We grouped the study population according to their attitude towards medication as presented by the above MG-DAI. Then, associations of pharmacophilia or pharmacophobia with the 3 categories listed below were determined.

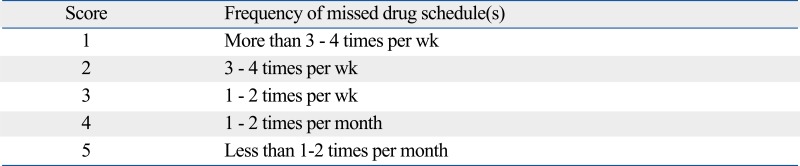

Subjective Drug Adherence Score

A subjective adherence score was assessed by asking each participant during the interview to name the number of times per week he/she has missed out on the dosing schedule. A grading system was employed from a scale of 1 for poorest adherence to 5 for best adherence (Supplement 2).

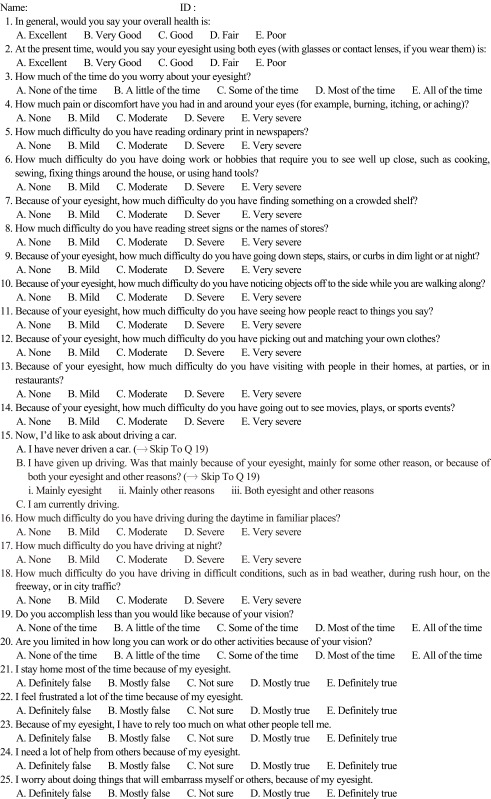

Modified National Eye Institute Visual Functioning Questionnaire-25 (NEIVFQ-25) for Koreans

The 25-item National Eye Institute Visual Functioning Questionnaire (NEIVFQ-25) version 2000 is a questionnaire assessing eleven dimensions of visual function and has been proposed as a means to determine the efficacy of treatment for different ocular conditions.16-18 The questionnaire has been translated into many languages, but not yet into Korean. We therefore translated the original 25 questions and modified the context into a Korean version (Supplement 3). Due to language constraints and local differences in culture, the questions were slightly modified.

Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI) Form GS

The Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI) is a self-report form originally developed by Myers and Briggs and translated into Korean by Sim.19 It is designed to assess normal personality traits as a psychometric instrument. This indicator was chosen because it assesses differences that result from the way people perceive information and how they prefer to use that information. Individuals fall into four dichotomous personality dimensions based upon their scores. There are eight categorical personality types: Introversion/Extroversion, Sensing/iNtuition, Thinking/Feeling, and Judging/Perceiving. The validity and reliability of the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI) have been proven, and the test has been widely used to examine personality profiles in Korea.20 The preference scores of the four dichotomies were used for analysis in the present study.

The patient population was first divided into pharmacophobic or pharmacophilic groups as determined by the MG-DAI as described above. Then, associations between the above drug attitudes and 1) subjective drug adherence scores, 2) each sub-category of the Modified NEIVFQ-25, and 3) each of the 4 personality dichotomies from the MBTI were sequentially determined.

Statistical analysis

Chi-square tests, Student t-tests, and Mann-Whitney U tests were used for univariate analyses. And Spearman's rank correlation coefficient (ρ) was computed to determine the relationship between MG-DAI and subjective drug adherence scores. All statistical analyses were carried out using SPSS 12.0 software (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL, USA) for Windows.

RESULTS

Initially, 147 consecutive patients were enrolled in this study. Of these, 22 patients refused the interview and were excluded from further analyses. Ten patients declined because they had an aversion to any clinical study and another twelve patients declined because they were pressed for time.

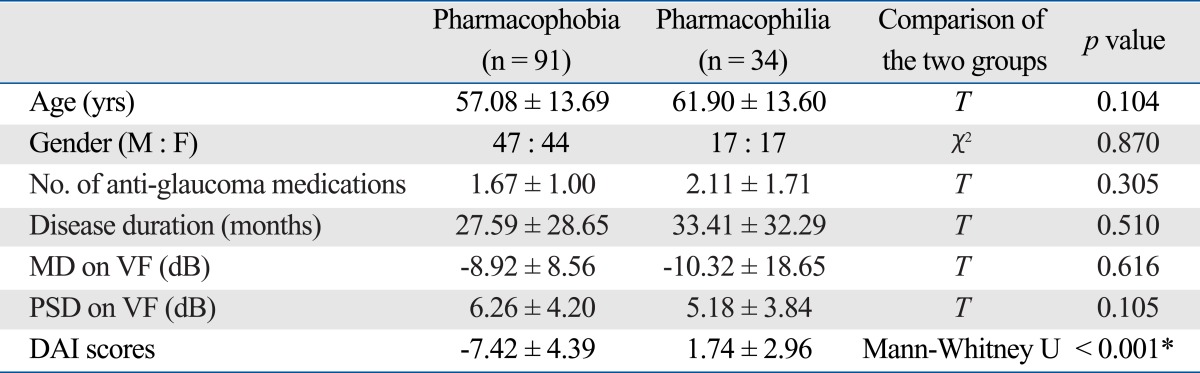

The patients' demographic characteristics are shown in Table 1. Ninety-one (72.80%) patients had a 'pharmacophobic' attitude and thirty-four (27.20%) showed a 'pharmacophilic' attitude to anti-glaucoma medications. Mean MG-DAI scores of the pharmacophobic group were -7.42 ± 4.39 and those of the pharmacophilic group were 1.74 ± 2.96 (p < 0.001). There were no significant differences between the two groups for age, gender, number of medications, disease duration, or visual field indices.

Table 1.

Patient Demographics according to Patient Attitude Towards Anti-Glaucoma Medication

DAI, drug attitude inventory scale; F, female; M , male; MD, mean deviation; PSD, pattern standard deviation; VF, visual field.

*p < 0.05.

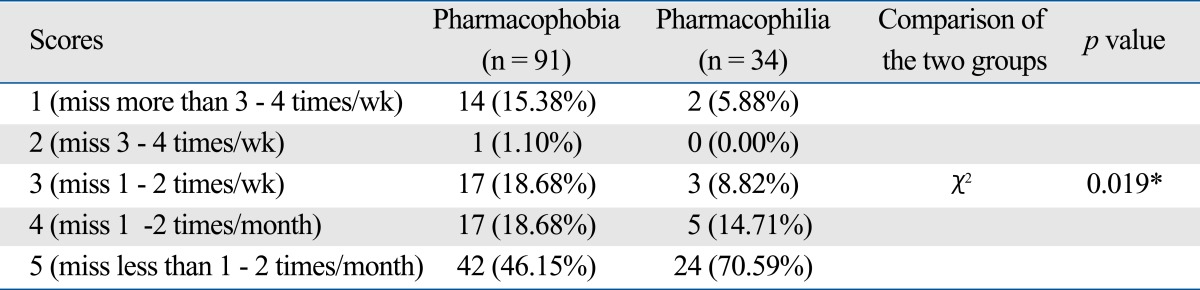

Subjective drug adherence scores were compared using the Chi-square test (Table 2). As one would predict, the pharmacophobic group tends to have worse adherence than the pharmacophilic group. In the pharmacophobic group, 46.15% of patients missed their medication fewer than 1 to 2 times per month, while 70.59% of patients in the pharmacophilic group showed the same level of adherence.

Table 2.

Subjective Drug Adherence Scores according to Patient Attitude Towards Anti-Glaucoma Medication

*p < 0.05.

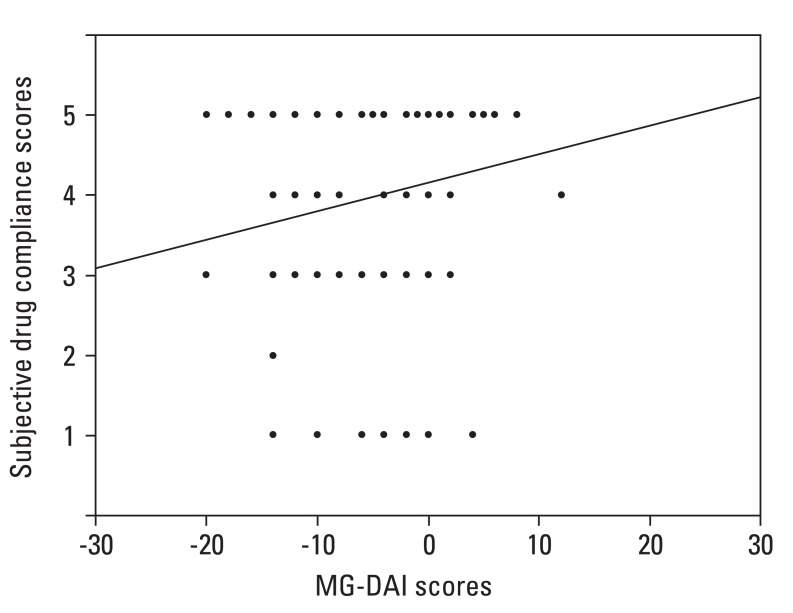

To investigate the relationship between the MG-DAI and the subjective drug adherence scores, Spearman's rank correlation coefficient (ρ) was determined (Fig. 1). Little association was found between them (ρ = 0.177, p = 0.049).

Fig. 1.

Relationship between the Modified Glaucoma Drug Attitude Inventory (MG-DAI) scores and the subjective drug adherence scores.

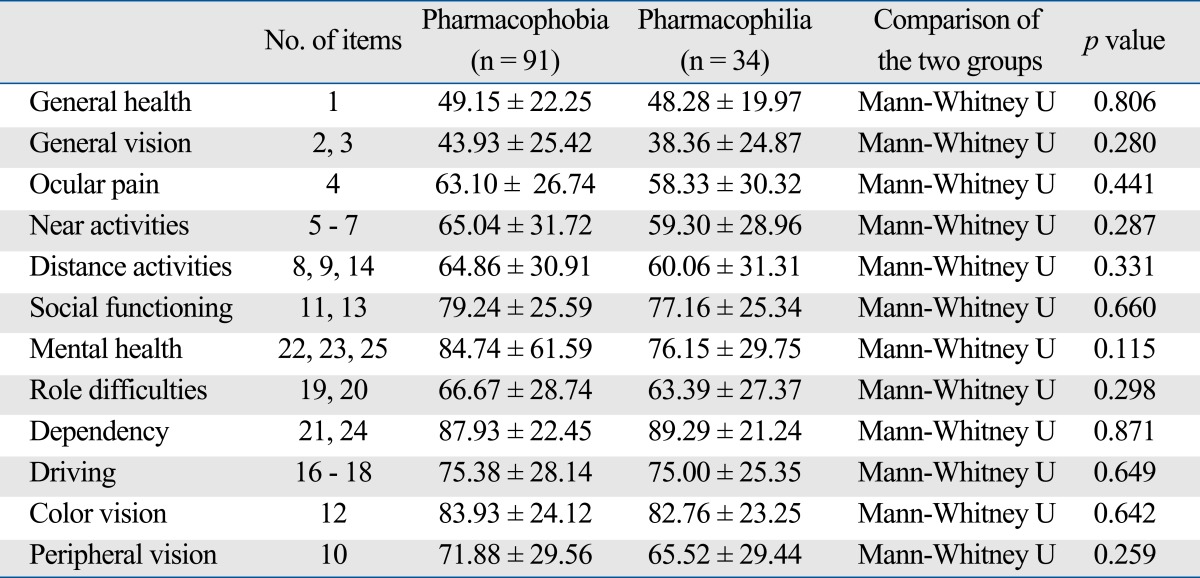

Each subscale in the Modified NEIVFQ-25 for Koreans was compared within the two groups and is shown in Table 3. No subscale shows a sharp distinction between the two groups. Although the scores for mental health seem to be slightly different, it was not statistically significant (p = 0.115). It revealed that the drug attitude might be not determined by the patient's visual function.

Table 3.

Modified National Eye Institute Functioning Questionnaire-25 (NEIVFG-25) Shown for Each Category according to Patient Attitude Towards Anti-Glau-coma Medication

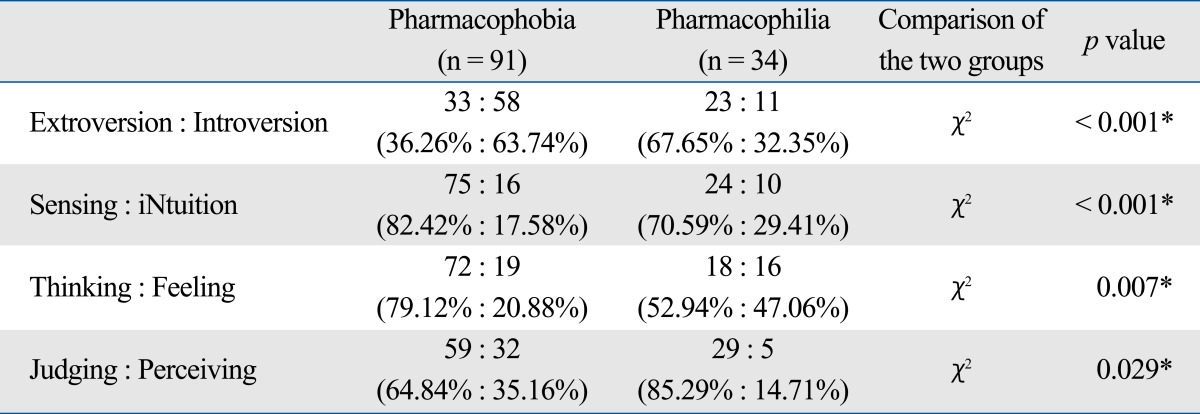

Personality dichotomies from the MBTI are shown in Table 4. In the pharmacophobic group, there were many more patients with an 'Introversion' trait (63.74%) than with an 'Extroversion' trait (36.26%), but the pharmacophilic group showed results that were the exact opposite (Introversion, 32.35%; Extroversion, 67.65%) (p < 0.001). For both groups, patients tended to be more in the 'Sensing', 'Thinking', and 'Judging' dichotomies than the 'iNtuition', 'Feeling', and 'Perceiving' dichotomies, respectively. However, component ratios were significantly different. In the pharmacophobic group, there was a relatively higher proportion of patients who were Sensing and Thinking and a relatively lower proportion of patients who were Judging when compared with the pharmacophilic group. It meant that the drug attitude might be influenced by the patient's personal character.

Table 4.

Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI) Profile Shown according to Patient Attitude Towards Anti-Glaucoma Medication

*p < 0.05.

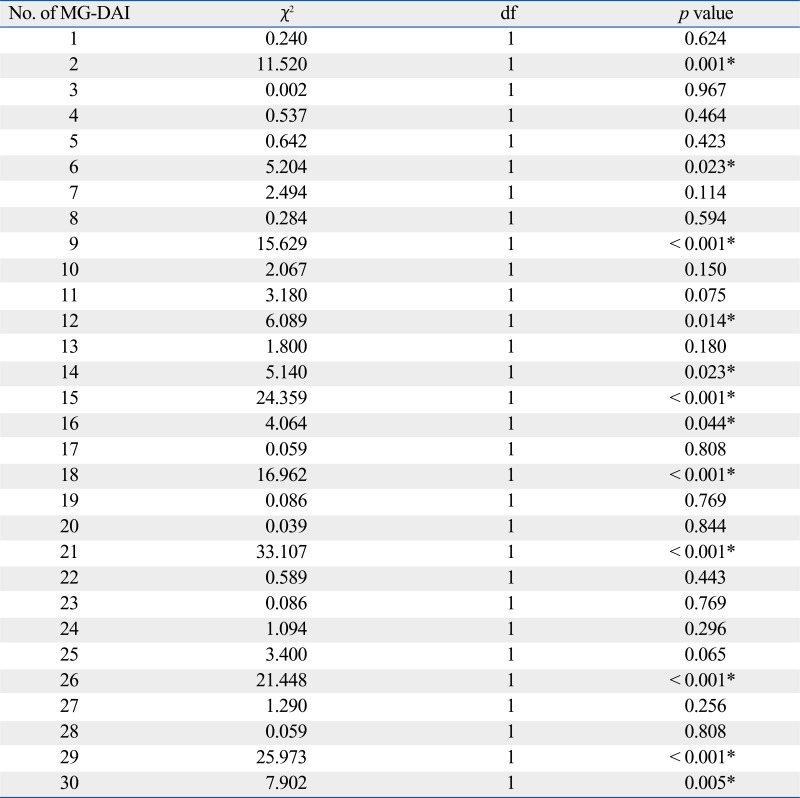

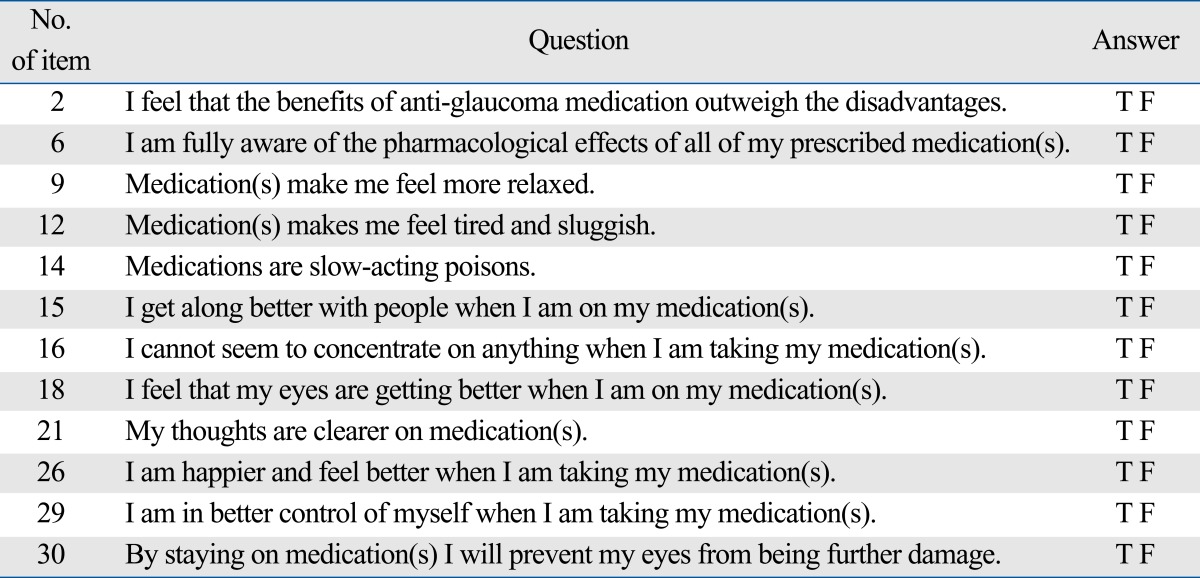

To select the proper items that help distinguish the two groups, each item of the MG-DAI was analyzed (Supplement 4). Twelve items (Item No. 2, 6, 9, 12, 14, 15, 16, 18, 21, 26, 29, and 30) showed a clear difference between the two groups. These selected items are shown in Table 5.

Table 5.

Selected Items of Modified Glaucoma Drug Attitude Inventory (MG-DAI) to Distinguish between Pharmacophobic and Pharmacophilic Groups

F, false; T, true.

DISCUSSION

A high rate of non-adherence is prevalent amongst patients with various chronic medical disorders for which the benefits of treatment are not immediately apparent.21-27 Several reports have mentioned that there is no identifiable type of patient based on demographic or clinical characteristics that is predictive of compliant behaviour.3-11 Several reports have remarked on the influence personality traits may have on drug adherence issues in chronic medical conditions.28-30 Therefore, the purpose of the present study was to expand on the variables that may possibly be linked with adherence, with a focus on psychological features that could lead to better identification of the noncompliant glaucoma patient.

In a recent study, Pappa, et al.31 reported on personality traits and psychiatric profiles of non-compliant glaucoma patients. They found that a significant proportion of non-compliant patients with glaucoma (59.5%) were at risk for psychiatric morbidity and recommended a formal psychiatric evaluation. Moreover, they found that depression was a significant risk factor for non-adherence with glaucoma treatment. In another report, designed to identify factors that influence attitudes towards psychopharmacological treatment in patients diagnosed with schizophrenia, the authors divided the patients according to their attitude and attempted to correlate it with adherence issues.15 This study was designed, with the aforementioned reports in mind, specifically for patients with glaucoma.

This report is based on the underlying assumption that a negative attitude towards pharmacological treatment will result in decreased adherence. Patients were divided into two groups based upon their attitude towards pharmacological treatment and were given a subjective adherence test. According to the present study, MG-DAI scores did not significantly correlate with subjective drug adherence scores; however, there was a significantly higher proportion of glaucoma patients who had a negative attitude towards drugs rather than positive and the greater the patient's phobia, the more non-compliant he/she was. The discordance between drug attitude and subjective adherence implies that at least some patients, even though they had a negative pharmacological attitude, were still compliant and vice versa. The rates of non-adherence, however, may actually be higher because patients are likely to underreport the times they failed to take their medication when questioned.32-35 And, we should pay attention to the twenty-two (14.97%) patients who refused any interview because their personal traits seems to somewhat influence their decision.

The impact of daily visual function on adherence was measured with the Modified NEIVFQ-25. Each of the subscales quantified by the questionnaire did not show any significant correlation with pharmacological adherence. Only mental health showed potential as a possible distinguishing factor between the two groups.

The possible influence of individual personality traits on MG-DAI was assessed with the MBTI. There appeared to be more introverts in the pharmacophobic group. Both groups had fewer patients who fit into the iNtuition dichotomy than into Sensing, but the phobic group had an even smaller percentage. Also, there were more patients in the Thinking dichotomy for both groups, but the phobic group had a larger percentage than the philic group in this dichotomy. Conversely, although both groups had more patients in the Judging category, the phobic group had fewer patients belonging to this category. The question of interpreting these results by comparing MG-DAI with MBTI needs to be answered at a later date.

Also, this report attempted to modify the original DAI questionnaire to suit glaucoma patients, and thus the original questionnaire was not only interpreted but simplified to meet these criteria. The authors hereby propose a new, modified version of the MG-DAI with 12 items (Table 5).

By introducing a concept of drug attitude, we tried to make a different approach to adherence in glaucoma patients. We excluded the patients who had previous ocular trauma history or received any ocular surgeries to remove any unexpected impact, but there is a chance that we have natural selection bias. It is possible that some patients who were hateful or afraid of medications might already undergo a certain surgical procedure. This is one limitation of our study. In addition, many other factors, such as doctor-patient relationship and patient's understanding of the disease, may influence drug attitude and/or adherence. Clinicians should be concerned with all these things.

In conclusion, according to the results of this study, pharmacological adherence was influenced by the attitude towards drugs in general, which was possibly mediated by an underlying personality trait as revealed by the MBTI. However, because the present study is limited due to its usage of a subjective adherence test,32-35 which can also be influenced by personality traits, another study needs to be done using methods that objectively quantify adherence to drugs. The assessment of those patients who refused to participate in an interview will be addressed in the future.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Presented at the 8th Congress of European Glaucoma Society, June 1-6, 2008, Berlin, Germany.

Footnotes

The authors have no financial conflicts of interest.

SUPPLEMENT

Supplement 1. Modified Glaucoma Drug Attitude Inventory (MG-DAI) Classification

Supplement 2. Grading System of Subjective Drug Adherence Scores

Supplement 3. Modified National Eye Institute Visual Functioning Questionnaire-25 (NEIVFQ-25) for Koreans

Supplement 4. Difference of Each Items of Modified Glaucoma Drug Attitude Inventory (MG-DAI) between Pharmacophobic and Pharmacophilic Groups

*p<0.05.

References

- 1.World Health Organization (WHO) The World Health Report 1997. Geneva: WHO; 1997. Conquering suffering, enriching humanity; pp. 68–69. [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization (WHO) The World health report 2004. Geneva: WHO; 2004. Changing history; pp. 128–129. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zimmerman TJ, Zalta AH. Facilitating patient compliance in glaucoma therapy. Surv Ophthalmol. 1983;28(Suppl 1):252–258. doi: 10.1016/0039-6257(83)90142-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee MD, Fechtner FR, Fiscella RG, Singh K, Stewart WC. Emerging perspectives on glaucoma: highlights of a roundtable discussion. Am J Ophthalmol. 2000;130:S1–S11. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(00)00635-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ashburn FS, Jr, Goldberg I, Kass MA. Compliance with ocular therapy. Surv Ophthalmol. 1980;24:237–248. doi: 10.1016/0039-6257(80)90045-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Davidsön SI, Akingbehin T. Compliance in ophthalmology. Trans Ophthalmol Soc U K. 1980;100:286–290. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Granström PA, Norell S. Visual ability and drug regimen: relation to compliance with glaucoma therapy. Acta Ophthalmol (Copenh) 1983;61:206–219. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-3768.1983.tb01414.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Spaeth GL. Visual loss in a glaucoma clinic. I. Sociological considerations. Invest Ophthalmol. 1970;9:73–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chang JS, Jr, Lee DA, Petursson G, Spaeth G, Zimmerman TJ, Hoskins HD, et al. The effect of a glaucoma medication reminder cap on patient compliance and intraocular pressure. J Ocul Pharmacol. 1991;7:117–124. doi: 10.1089/jop.1991.7.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Riffenburgh Rs. Doctor-patient relationship in glaucoma therapy. Arch Ophthalmol. 1966;75:204–206. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1966.00970050206011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bloch S, Rosenthal AR, Friedman L, Caldarolla P. Patient compliance in glaucoma. Br J Ophthalmol. 1977;61:531–534. doi: 10.1136/bjo.61.8.531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Demailly P, Zoute C, Castro D. [Personalities and chronic glaucoma] J Fr Ophtalmol. 1989;12:595–601. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wilson MR, Coleman AL, Yu F, Fong Sasaki I, Bing EG, Kim MH. Depression in patients with glaucoma as measured by self-report surveys. Ophthalmology. 2002;109:1018–1022. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(02)00993-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hogan TP, Awad AG, Eastwood R. A self-report scale predictive of drug compliance in schizophrenics: reliability and discriminative validity. Psychol Med. 1983;13:177–183. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700050182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sibitz I, Katschnig H, Goessler R, Unger A, Amering M. Pharmacophilia and pharmacophobia: determinants of patients' attitudes towards antipsychotic medication. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2005;38:107–112. doi: 10.1055/s-2005-864119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mangione CM, Lee PP, Pitts J, Gutierrez P, Berry S, Hays RD NEI-VFQ Field Test Investigators. Psychometric properties of the National Eye Institute Visual Function Questionnaire (NEI-VFQ) Arch Ophthalmol. 1998;116:1496–1504. doi: 10.1001/archopht.116.11.1496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mangione CM, Lee PP, Gutierrez PR, Spritzer K, Berry S, Hays RD National Eye Institute Visual Function Questionnaire Field Test Investigators. Development of the 25-item National Eye Institute Visual Function Questionnaire. Arch Ophthalmol. 2001;119:1050–1058. doi: 10.1001/archopht.119.7.1050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mangione CM. The National Eye Institute 25-Item Visual Function Questionnaire (VFQ-25) NEI VFQ-25 Scoring Algorithm-August 2000. Available at: http://www.nei.nih.gov/resources/visionfunction/manual_cm2000.pdf.

- 19.Sim HC. A cross-cultural study of a personality inventory: The development and validation of the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator in the Korean language. St. Louis: Saint Louis University; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim J, Sim H, Je S. Development and use of MBTI. Seoul: KPTI; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Guillausseau PJ. Impact of compliance with oral antihyperglycemic agents on health outcomes in type 2 diabetes mellitus: a focus on frequency of administration. Treat Endocrinol. 2005;4:167–175. doi: 10.2165/00024677-200504030-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Marquis RE, Whitson JT. Management of glaucoma: focus on pharmacological therapy. Drugs Aging. 2005;22:1–21. doi: 10.2165/00002512-200522010-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vakil N. Increasing compliance with long-term therapy: avoiding complications and adverse events. Rev Gastroenterol Disord. 2005;5(Suppl 2):S12–S17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cortet B, Bénichou O. Adherence, persistence, concordance: do we provide optimal management to our patients with osteoporosis? Joint Bone Spine. 2006;73:e1–e7. doi: 10.1016/j.jbspin.2006.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Costantini L. Compliance, adherence, and self-management: is a paradigm shift possible for chronic kidney disease clients? CANNT J. 2006;16:22–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gold DT, McClung B. Approaches to patient education: emphasizing the long-term value of compliance and persistence. Am J Med. 2006;119:S32–S37. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2005.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.López-Sanromán A, Bermejo F. Review article: how to control and improve adherence to therapy in inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006;24(Suppl 3):45–49. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2006.03060.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.DiMatteo MR, Lepper HS, Croghan TW. Depression is a risk factor for noncompliance with medical treatment: meta-analysis of the effects of anxiety and depression on patient adherence. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:2101–2107. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.14.2101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Druss BG, Rosenheck RA, Desai MM, Perlin JB. Quality of preventive medical care for patients with mental disorders. Med Care. 2002;40:129–136. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200202000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Katon WJ. Clinical and health services relationships between major depression, depressive symptoms, and general medical illness. Biol Psychiatry. 2003;54:216–226. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(03)00273-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pappa C, Hyphantis T, Pappa S, Aspiotis M, Stefaniotou M, Kitsos G, et al. Psychiatric manifestations and personality traits associated with compliance with glaucoma treatment. J Psychosom Res. 2006;61:609–617. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2006.03.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fielder AR, Irwin M, Auld R, Cocker KD, Jones HS, Moseley MJ. Compliance in amblyopia therapy: objective monitoring of occlusion. Br J Ophthalmol. 1995;79:585–589. doi: 10.1136/bjo.79.6.585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Oelzner S, Brandstädt A, Hoffmann A. Correlations between subjective compliance, objective compliance, and factors determining compliance in geriatric hypertensive patients treated with triamterene and hydrochlorothiazide. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1996;34:236–242. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kudielka BM, Broderick JE, Kirschbaum C. Compliance with saliva sampling protocols: electronic monitoring reveals invalid cortisol daytime profiles in noncompliant subjects. Psychosom Med. 2003;65:313–319. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000058374.50240.bf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bos A, Kleverlaan CJ, Hoogstraten J, Prahl-Andersen B, Kuitert R. Comparing subjective and objective measures of headgear compliance. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2007;132:801–805. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2006.01.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplement 1. Modified Glaucoma Drug Attitude Inventory (MG-DAI) Classification

Supplement 2. Grading System of Subjective Drug Adherence Scores

Supplement 3. Modified National Eye Institute Visual Functioning Questionnaire-25 (NEIVFQ-25) for Koreans

Supplement 4. Difference of Each Items of Modified Glaucoma Drug Attitude Inventory (MG-DAI) between Pharmacophobic and Pharmacophilic Groups

*p<0.05.