Abstract

Although most of the components of the cell cycle machinery are conserved in all eukaryotes, plants differ strikingly from animals by the absence of a homolog of E-type cyclin, an important regulator involved in G1/S-checkpoint control in animals. By contrast, plants contain a complex range of A-type cyclins, with no fewer than 10 members in Arabidopsis. We previously identified the tobacco A-type cyclin Nicta;CYCA3;2 as an early G1/S-activated gene. Here, we show that antisense expression of Nicta;CYCA3;2 in tobacco plants induces defects in embryo formation and impairs callus formation from leaf explants. The green fluorescent protein (GFP)–Nicta;CYCA3;2 fusion protein was localized in the nucleoplasm. Transgenic tobacco plants overproducing GFP-Nicta;CYCA3;2 could not be regenerated from leaf disc transformation, whereas some transgenic Arabidopsis plants were obtained by the floral-dip transformation method. Arabidopsis plants that overproduce GFP-Nicta;CYCA3;2 showed reduced cell differentiation and endoreplication and a dramatically modified morphology. Calli regenerated from leaf explants of these transgenic Arabidopsis plants were defective in shoot and root regeneration. We propose that Nicta;CYCA3;2 has important functions, analogous to those of cyclin E in animals, in the control of plant cell division and differentiation.

INTRODUCTION

Most development of the mature plant takes place postembryonically and originates in the activities of small groups of cells called meristems. Plant cells are surrounded by a rigid cell wall and divide in place, providing an interesting model to address the role of cell division and cell differentiation in development. It is generally accepted that control of the numbers, places, and planes of cell division, coupled with regulated and coordinated cellular expansion and differentiation, are critical in organogenesis during plant development (Meyerowitz, 1997). However, the role of cell division as a causal element in plant morphogenesis has long been debated. Molecular characterizations of mutants defective in morphogenesis have not identified cell cycle regulators as responsible elements (Meyerowitz, 1997; Nakajima and Benfey, 2002). Nor did modulation of the expression of cell cycle genes, including those that encode cyclin-dependent kinases (CDKs) (Hemerly et al., 1995; Porceddu et al., 2001) and some cyclins (Doerner et al., 1996; Cockcroft et al., 2000), result in abnormal morphology, although in most cases plant growth rate was altered. Together, these observations suggest that intrinsic mechanisms exist that operate throughout the organ or organism as a unit to dictate size and shape. The molecular basis underlying such intrinsic mechanisms, however, is unclear. In addition, conflicting data exist reporting that ectopic expression of the Arabidopsis D-type cyclin Arath;CYCD3;1 (Riou-Khamlichi et al., 1999; Dewitte et al., 2003), the Arabidopsis and tobacco CDK inhibitor ICK1/KRP1/KIS1 (Wang et al., 2000; De Veylder et al., 2001; Jasinski et al., 2002), and the cell cycle–specific transcription factor E2Fa-DPa of Arabidopsis (De Veylder et al., 2002) affect regeneration, organ shape, and/or the entire morphology of Arabidopsis plants.

D-type cyclins are conserved in animals and plants and are proposed to be sensors of growth conditions and to trigger the G1/S transition by activating the RBR/E2F-DP pathway (Gutierrez et al., 2002; Shen, 2002; Trimarchi and Lees, 2002). The RBR/E2F-DP pathway not only regulates the expression of genes required for the G1/S transition and S-phase progression but also is involved in other developmental processes (Muller et al., 2001; Ramirez-Parra et al., 2003). Observations that the ectopic expression of Arath;CYCD3;1 or E2Fa-DPa in Arabidopsis results in hyperplasia in leaves and dramatically affects plant morphogenesis (De Veylder et al., 2002; Dewitte et al., 2003) strengthen the important role of the CYCD/RBR/E2F-DP pathway in the control of cell proliferation and development. The fact that the phenotype induced by the ectopic expression of ICK1/KRP1/KIS1 can be attenuated by the simultaneous ectopic expression of Arath;CYCD3;1 (Jasinski et al., 2002; Schnittger et al., 2003; Zhou et al., 2003) indicates that ICK1/KRP1/KIS1 regulates cell proliferation and plant morphogenesis primarily through the inhibition of function of the Arath;CYCD3;1-CDK kinase complex.

In addition to D-type cyclins, plants contain a large number of mitotic cyclins, no fewer than 19 in Arabidopsis, belonging to three A-type (CYCA1, CYCA2, and CYCA3) and two B-type (CYCB1 and CYCB2) subclasses (Renaudin et al., 1996; Vandepoele et al., 2002). B-type cyclins are expressed within a narrow time window from late G2- to mid M-phase, and the ectopic expression of both Arath;CYCB1;1 and Oryza;CYCB2;2 accelerates root growth (Doerner et al., 1996; Lee et al., 2003). However, this substantial alteration of cell division rate does not alter root morphology, suggesting that these B-type cyclins are not critical in cell fate determination. In contrast to animals, in which only a single A-type cyclin gene is present in invertebrates and two are present in vertebrates (Nieduszynski et al., 2002), plants hold a higher complexity of A-type cyclins, comprising in Arabidopsis two A1-type (CYCA1;1 and CYCA1;2), four A2-type (CYCA2;1, CYCA2;2, CYCA2;3, and CYCA2;4), and four A3-type (CYCA3;1, CYCA3;2, CYCA3;3,and CYCA3;4) members (Chaubet-Gigot, 2000; Vandepoele et al., 2002). In synchronized tobacco BY2 cells, different A-type cyclins are expressed sequentially at different time points from late G1/early S-phase until mid M-phase (Reichheld et al., 1996). The alfalfa A2-type cyclin Medsa;CYCA2;2 is expressed in all phases of the cell cycle, but its associated kinase activity peaks both in S-phase and during the G2/M transition (Roudier et al., 2000). These molecular data suggest that A-type cyclins may have different functions in plants.

We were particularly interested in functional characterization of the tobacco A3-type cyclin Nicta;CYCA3;2 because of its early activated expression at the G1/S transition (Reichheld et al., 1996). We first regenerated transgenic tobacco plants expressing Nicta;CYCA3;2 under the control of the tetracycline-inducible promoter. Local and transient induction of Nicta;CYCA3;2 expression induces cell division in both the shoot apical meristem and the leaf primordia (Wyrzykowska et al., 2002). However, significant effects could not be established when the induction of expression was performed at the whole-plant level. Recently, it was reported that transgenic alfalfa plants expressing Medsa;CYCA2;2 under the control of the constitutive 35S promoter exhibit high transcript levels but unchanged protein levels and a normal phenotype (Roudier et al., 2003).

Here, we investigated the expression of Nicta;CYCA3;2 in tobacco plants and found it to be positively associated with proliferating tissues. By fusion with the green fluorescent protein (GFP), we demonstrate that the Nicta;CYCA3;2 protein localized exclusively in the nucleoplasm with speckle structures. We addressed the function of Nicta;CYCA3;2 in tobacco by antisense expression and found that its loss of function induced defects in embryo formation and impaired callus formation in vitro from leaf explants. We failed to obtain transgenic tobacco plants that overproduce the GFP-Nicta;CYCA3;2 fusion protein, possibly because its high levels are incompatible with plant regeneration from transformed leaf explants. Nevertheless, using the floral-dip method, we obtained some transgenic Arabidopsis plants that showed variable (from undetectable to high) levels of fluorescence of the fusion protein. Only transgenic Arabidopsis plants containing high levels of the fusion protein showed a dramatically modified phenotype. They had a decreased level of endoreplication (also named endoreduplication) and an increased level of histone transcripts, indicating that GFP-Nicta;CYCA3;2 inhibits cell differentiation. Furthermore, calli regenerated from leaf explants of these transgenic Arabidopsis plants were defective in shoot and root regeneration. By immunoprecipitation and affinity binding assays, we confirmed that GFP-Nicta;CYCA3;2 can form active CDK complexes in Arabidopsis.

RESULTS

Expression of the Nicta;CYCA3;2 Gene

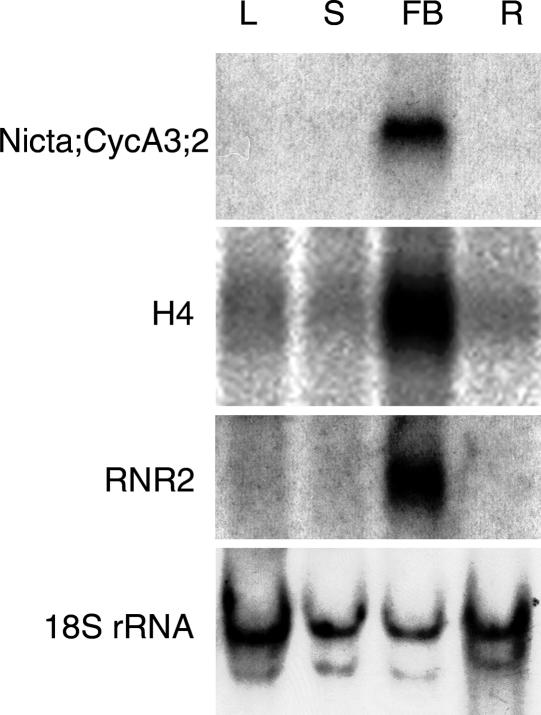

Four A-type cyclins of tobacco had been characterized previously for their expression pattern during the cell cycle in BY2 suspension cells (Setiady et al., 1995; Reichheld et al., 1996). Nicta;CYCA1;1 and Nicta;CYCA2;1 are expressed from mid S-phase to mid M-phase, whereas Nicta;CYCA3;1 and Nicta;CYCA3;2 are expressed earlier, from the G1/S transition to early M-phase. During the G1/S transition, Nicta;CYCA3;2 is expressed ∼1 h earlier than Nicta;CYCA3;1, which precedes the aphidicolin blockage point (Reichheld et al., 1996). To gain insight into the function of Nicta;CYCA3;2 in plant development, we analyzed its expression in different organs of tobacco plants using RNA gel blot hybridization (Figure 1). Nicta;CYCA3;2 mRNA was detected at a high level in flower buds but was barely detectable in leaves, stems, and roots. The absence of a hybridization signal in these latter organs may be attributable to the limited sensitivity of RNA gel blot analysis. We believe that the high level of Nicta;CYCA3;2 mRNA in flower buds is associated primarily with the presence of proliferating tissues in this organ and to only a limited degree with flower specificity. This is because, first, a pattern of expression similar to that of Nicta;CYCA3;2 was observed for the histone H4 and ribonucleotide reductase RNR2 (Figure 1), the two genes known to be expressed in different types of proliferating tissues (Chaubet et al., 1996; Chabouté et al., 1998), and second, a high level of Nicta;CYCA3;2 mRNA was detected in young seedlings (see Figure 4A). In addition, Nicta;CYCA3;2 transcripts were detected previously by in situ hybridization in leaf primordia (Wyrzykowska et al., 2002).

Figure 1.

RNA Gel Blot Analysis of Nicta;CYCA3;2 Transcripts in Different Organs of Tobacco Plants.

RNA samples prepared from leaves (L), stems (S), flower buds (FB), and roots (R) were hybridized successively with the Nicta;CYCA3;2, the histone H4, the ribonucleotide reductase RNR2, and the ribosomal 18S rRNA probes. The ribosomal 18S rRNA probe served as a loading control.

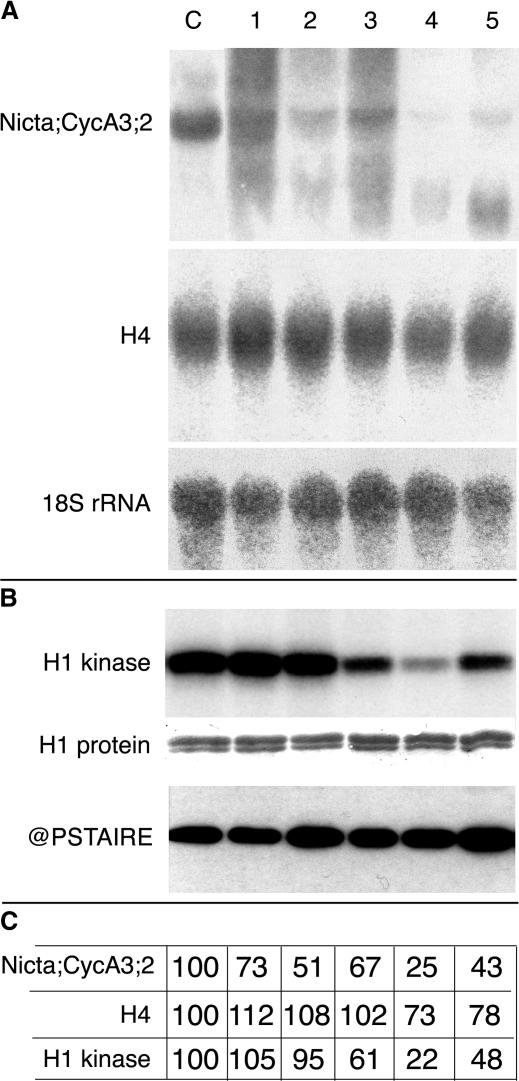

Figure 4.

Nicta;CYCA3;2 Transcript Levels and CDK Kinase Activity in Antisense Transgenic Tobacco Plants.

Three-week-old seedlings of the wild type (lane C) and of the antisense Nicta;CYCA3;2 transgenic lines AS1 (lane 1), AS2 (lane 2), AS3 (lane 3), AS4 (lane 4), and AS5 (lane 5) in the H4A748 background were analyzed.

(A) An RNA gel blot was hybridized successively with Nicta;CYCA3;2, the histone H4, and the ribosomal 18S rRNA probes.

(B) Histone H1 kinase activity was assayed on p13suc1-Sepharose affinity-purified CDK-cyclin complexes from equal amounts (200 μg) of total plant proteins (H1 kinase). Equal loading of histone H1 (H1 protein) and the immunodetection of PSTAIRE-containing CDK protein (@PSTAIRE) are shown as controls.

(C) Quantitation of Nicta;CYCA3;2 and histone H4 transcript levels as well as phosphorylated H1 levels was performed using a PhosphorImager (Molecular Dynamics, Sunnyvale, CA). Transcript levels were normalized against the ribosomal 18S rRNA.

Subcellular Localization of the Nicta;CYCA3;2 Protein

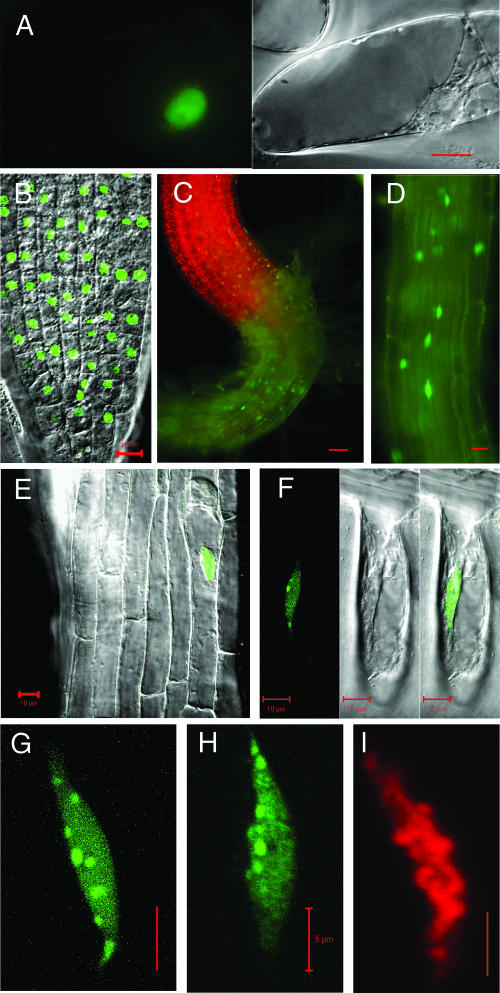

To study the localization of the Nicta;CYCA3;2 protein, its cDNA was fused in frame to the 3′ end of the cDNA encoding the GFP, resulting in GFP-Nicta;CYCA3;2. The fusion construct under the control of the constitutive Cauliflower mosaic virus 35S promoter was introduced into both tobacco BY2 cells and Arabidopsis plants. We obtained transgenic BY2 strains that contained only a small proportion (up to 15%) of cells showing detectable GFP fluorescence. This finding possibly indicates that high levels of GFP-Nicta;CYCA3;2 are incompatible with BY2 cell growth. In cells expressing GFP-Nicta;CYCA3;2, the fluorescence was detected exclusively within the nucleus (Figure 2A). In transgenic Arabidopsis plants expressing GFP-Nicta;CYCA3;2, fluorescence was detected primarily in cells within regions close to the hypocotyl root junction (Figures 2C and 2D). The root tip did not show GFP-Nicta;CYCA3;2 fluorescence. This finding differs from what was seen in plants expressing H2B-CFP under the control of the same promoter, in which fluorescent cells were distributed more uniformly in different organs, including root tips (Figure 2B). It is likely that mechanisms exist to downregulate the level of GFP-Nicta;CYCA3;2, particularly in cells of proliferating tissues (e.g., root meristems located in the tip).

Figure 2.

Localization of the GFP-Nicta;CYCA3;2 Fusion Protein in Transgenic Tobacco BY2 Cells and in Transgenic Arabidopsis Plants.

(A) Epifluorescent and bright-field differential interference contrast (DIC) images of a tobacco BY2 cell expressing GFP-Nicta;CYCA3;2. Note the green fluorescence exclusively in the nucleus.

(B) Overlay of confocal epifluorescent and DIC images of a root tip from an Arabidopsis plant expressing H2B-CFP. Note the green fluorescence in the nuclei of all of the imaged cells.

(C) and (D) Epifluorescent images of the hypocotyl root (C) and the root regions (D) of an Arabidopsis plant expressing GFP-Nicta;CYCA3;2. Note the green fluorescence in only some of the cells.

(E) Overlay of confocal epifluorescent and DIC images of the Arabidopsis root region expressing GFP-Nicta;CYCA3;2. Note the green fluorescence in the nucleus of an epidermal cell.

(F) Confocal epifluorescent, DIC, and overlay images of a root hair from an Arabidopsis plant expressing GFP-Nicta;CYCA3;2. Note the green fluorescence exclusively in the nucleus and a few bright spots in nuclear bodies.

(G) to (I) Projections of confocal image stacks.

(G) and (H) Nuclei of the Arabidopsis root hairs expressing GFP-Nicta;CYCA3;2 (G) and H2B-CFP (H). Note the difference in the distribution of nuclear bodies as well as the diffuse nucleoplasm and the chromatin fiber localization of GFP-Nicta;CYCA3;2 and H2B-CFP, respectively.

(I) Nucleus of a root hair after propidium iodide staining. Note the red fluorescence of the stained DNA.

Bars = 10 μm in (A) to (F) and 5 μm in (G) to (I).

In cells from different types of tissues, including the epidermis and cortex of hypocotyls and roots, as well as in root hairs, GFP-Nicta;CYCA3;2 fluorescence again was located exclusively in the nuclei (Figures 2E and 2F). Strong fluorescent nuclear bodies (Figure 2G), with a number varying from three to nine per nucleus in Arabidopsis, were observed in cells expressing GFP-Nicta;CYCA3;2, suggesting that the GFP-Nicta;CYCA3;2 protein occupies particular nuclear territories and/or has specific target regions in the nucleus. Distinct from H2B-CFP, which was incorporated in the nucleosome and showed chromatin fiber localization (Figures 2H and 2I), GFP-Nicta;CYCA3;2 was diffuse in the nucleoplasm (Figure 2G). GFP-Nicta;CYCA3;2 fluorescence was never detected in the nucleoli, whereas the GFP-Nicta;CYCA3;1 fusion protein has been shown to be localized in the nucleus and nucleoli (Criqui et al., 2001), suggesting that Nicta;CYCA3;1 and Nicta;CYCA3;2 can have different nucleolar functions. We detected no GFP-Nicta;CYCA3;2 fluorescence in metaphase cells, suggesting that the fusion protein may be degraded at M-phase. Nicta;CYCA3;1 has been demonstrated to be degraded at early M-phase (Genschik et al., 1998; Criqui et al., 2001).

Antisense Nicta;CYCA3;2 Expression Induces Defects in Embryogenesis

To assess the consequences of the downregulation of Nicta;CYCA3;2 on plant development, we cloned the Nicta;CYCA3;2 cDNA in the antisense orientation behind the TetO promoter in the pBinHyg-Tx vector (Gatz et al., 1992). Two types of tobacco plants were used in this transformation: TetR homozygous plants, which were engineered to overexpress the TET repressor protein (Gatz et al., 1992), and H4A748 homozygous plants, which were engineered to express the β-glucuronidase (GUS) reporter gene under the control of an Arabidopsis histone H4 promoter (Lepetit et al., 1992). In the TetR background, transcriptional activity of the TetO promoter is repressed until the addition of tetracycline, whereas in the H4A748 background, TetO functions as a strong constitutive promoter. Transformation with antisense Nicta;CYCA3;2 under the control of the TetO promoter resulted in numerous transformants from TetR leaf discs. However, only a few transformants were regenerated from H4A748 leaf discs. The inhibition effect of the expression of antisense Nicta;CYCA3;2 on regeneration is discussed below. Here, we present our studies on the transformants obtained in the H4A748 background.

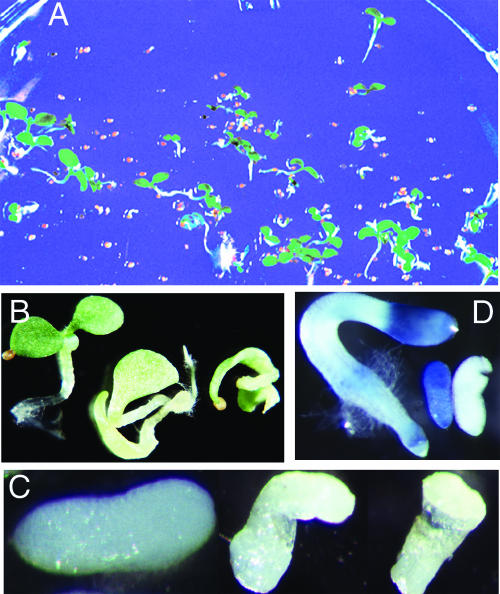

Of eight plants regenerated from different (parts of) leaf discs and therefore originating from independent transformation events, five plants were confirmed by PCR amplification for the presence of antisense Nicta;CYCA3;2 in their genomes. These plants (hereafter named lines AS1 to AS5) grew without showing significant defects in morphology or development and were allowed to set seeds by self-fertilization. Although AS1 seeds germinated with 100% efficiency and resulted in seedlings identical to the wild type, AS2, AS3, AS4, and AS5 seeds showed defects in germination and/or seedling growth, with 4, 10, 46, and 36% of seeds, respectively (based on 500 to 600 seeds plated for each line), blocked in germination and/or seedling growth. Figure 3A shows a germination plate of AS4 seeds. The defective seeds can be classified into two groups according to their germination capability. The first group, which accounted for a small percentage (<5%) of defective seeds, retained germination capability, but the seedlings exhibited severe distortions of morphology. The most affected seedlings lacked roots, hypocotyls, and shoot meristems, whereas the less affected seedlings lacked only shoot meristems (Figure 3B). The second group of defective seeds was incapable of germination. Dissections of the seeds revealed that most embryos were not properly formed (Figure 3C): embryonic roots, hypocotyls, and cotyledons could not be identified. Some embryos appeared phenotypically normal but failed to express the reporter H4 promoter-GUS gene (Figure 3D), indicating defects in proliferation. Together, these observations indicate that Nicta;CYCA3;2 is essential for embryo patterning and morphogenesis.

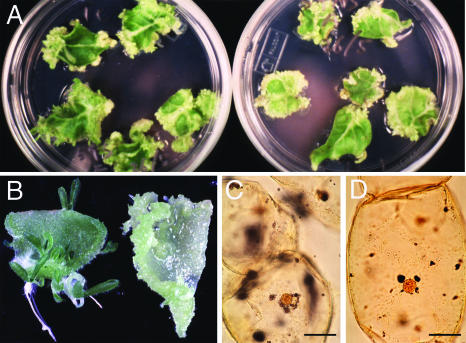

Figure 3.

Loss of Function of Nicta;CYCA3;2 Causes Defects in Tobacco Embryo and Seedling Formation.

Investigations were made using antisense Nicta;CYCA3;2 transgenic plants in the H4A748 background containing a GUS reporter gene under the control of a histone H4 promoter.

(A) Germination plate of seeds from self-fertilization of the transgenic line AS4. Note the high number of seeds defective in germination. The photograph was taken 10 days after germination.

(B) Normal (left) and defective (middle and right) seedlings of line AS4 at 14 days after germination. Note the lack of a shoot meristem in the middle seedling and the lack of roots, hypocotyls, and shoot meristems in the seedling at right.

(C) Normal (left) and defective (middle and right) embryos dissected from the wild-type seed and defective AS4 seeds, respectively. Note the lack of formation of embryonic roots, hypocotyls, and cotyledons in the defective embryos.

(D) Histochemical detection of GUS activity in a wild-type embryo (middle), an AS4 seedling (left), and an AS4 defective embryo (right). Note the absence of GUS activity in the AS4 defective embryo.

To verify the molecular effects of antisense Nicta;CYCA3;2, we analyzed the level of Nicta;CYCA3;2 mRNA and p13suc1 affinity-purified CDK activity in germinated seedlings. Strong decreases (greater than twofold) of both Nicta;CYCA3;2 mRNA and CDK activity (assayed using histone H1 as a substrate) were detected in the AS4 and AS5 lines (Figure 4). This finding is consistent with the strong defects of embryo formation observed in these lines. Slight decreases in H4 mRNA levels also were noted in these lines (Figure 4). However, correlations between the phenotype, the Nicta;CYCA3;2 mRNA level, and the CDK activity could not be established in the weakly affected AS1, AS2, and AS3 lines. This discrepancy might reflect limitations of the detection sensitivity, but it also could be explained by other, yet unknown mechanism(s) that compensate for the downregulation of Nicta;CYCA3;2 mRNA level.

Antisense Nicta;CYCA3;2 Expression Inhibits Callus Regeneration

To further analyze the effects of the ectopic expression of antisense Nicta;CYCA3;2 on plant regeneration from leaf discs, we tested callus formation in vitro using inducible expression in the TetR background. Of 13 initially established transgenic lines from the transformation of TetR leaf discs, 3 lines were selected for this study for their high efficiency in reducing Nicta;CYCA3;2 mRNA levels upon tetracycline induction in seedlings. All three lines gave similar results, and we present here results obtained from one of them. In the absence of tetracycline, the antisense Nicta;CYCA3;2 leaf discs exhibited callus and shoot regeneration similar to that in control TetO promoter-GUS leaf discs (data not shown). However, in the presence of tetracycline, callus and shoot formation were inhibited significantly from antisense Nicta;CYCA3;2 leaf discs compared with control leaf discs (Figure 5A). The inhibition was even more pronounced when the tests were performed in liquid medium (Figure 5B). A reduced number of cell divisions could be the cause of the observed inhibition, because cells of antisense Nicta;CYCA3;2 calli were larger than those of control calli (Figures 5C and 5D), with cell areas of 28,176 ± 3,158 (n = 67) and 17,333 ± 2,639 (n = 84) μm2, respectively.

Figure 5.

Antisense Expression of Nicta;CYCA3;2 Inhibits Callus Formation on Tobacco Leaf Discs.

Leaf discs from transgenic plants in the TetR background were analyzed for inducible expression with tetracycline.

(A) Callus formation from leaf discs of control (left) and antisense Nicta;CYCA3;2 (right) cultured on solidified medium.

(B) Callus formation from a representative leaf disc of control (left) and antisense Nicta;CYCA3;2 (right) cultured in liquid medium.

(C) and (D) Representative calli cells of control (C) and antisense Nicta;CYCA3;2 (D) after staining with Lugol's iodine-iodide solution. Bars = 30 μm.

Ectopic Expression of GFP-Nicta;CYCA3;2 Affects Arabidopsis Development

To investigate the effects of the overexpression of Nicta;CYCA3;2 on plant development, we used the construct GFP-Nicta;CYCA3;2 under the control of the constitutive 35S promoter. This allows the selection of transformants by detection of the fluorescence of the fusion protein with a microscope. After difficulties in getting transgenic tobacco plants to overproduce the fusion protein by leaf disc transformation, we chose to transform Arabidopsis plants by the floral-dip method (Clough and Bent, 1998), which does not require in vitro tissue regeneration. We screened a large pool of seeds collected from the transformation of 16 Arabidopsis plants. Twenty-one transformants were obtained after selection on kanamycin plates. Examination by microscopy revealed that seven of them showed no detectable GFP fluorescence, and nine of them showed GFP-fluorescent cells (with the number of cells ranging from 1 to >50) located in the hypocotyl and root in proximity to the junction of the two organs (Figure 2C). These transformants with no or weak GFP-Nicta;CYCA3;2 production grew and set seeds without a noticeable phenotype. A similar pattern of GFP fluorescence was observed in seedlings of the next generation from self-fertilization of these plants. In seedlings of two lines showing a relatively high number of GFP-fluorescent cells, a slight inhibition of primary root growth and accelerated secondary root growth were noted early after germination (Figure 6B). However, no other phenotype was observed in these first 16 transgenic lines.

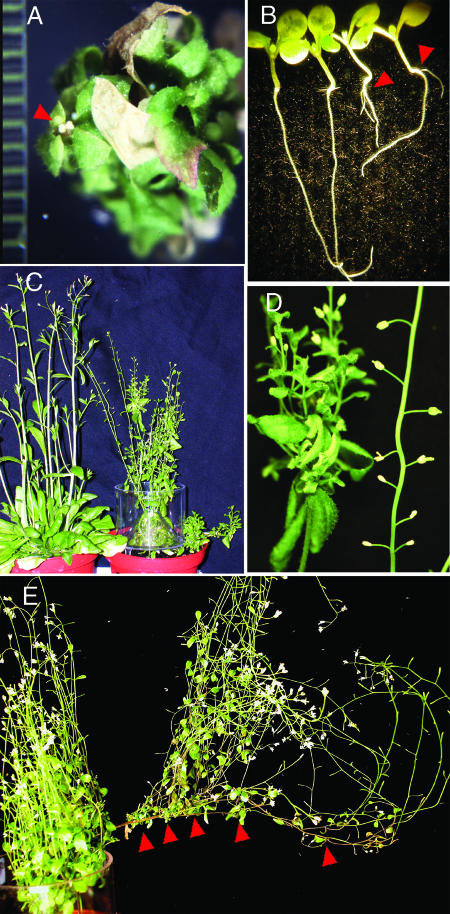

Figure 6.

Phenotype of Arabidopsis Plants Overexpressing GFP-Nicta;CYCA3;2.

(A) A transformant with high expression of GFP-Nicta;CYCA3;2 at 60 days after germination in vitro. The gradations at left are in 1-mm units. The arrowhead points to a flower stalk.

(B) Two seedlings with moderate expression of GFP-Nicta;CYCA3;2 (right) compared with two wild-type seedlings (left) at 7 days after germination. The arrowheads point to newly forming lateral roots.

(C) Transformant OE1 with high expression of GFP-Nicta;CYCA3;2 (right) compared with a wild-type plant (left) at 60 and 45 days of growth in the greenhouse, respectively.

(D) Close-up of a bushy (left) and a sterile (right) flower stalk of the transformant OE1.

(E) Transformant OE1 at 100 days of growth in the greenhouse. The arrowheads point to the highly proliferating lateral shoots from a flower stalk.

By contrast, the other five transformants showed an increased number of GFP-fluorescent cells not only in roots and hypocotyls but also in leaves, indicating a high level of GFP-Nicta;CYCA3;2 protein in these lines. Striking developmental effects were observed in these lines. The two transformants maintained in vitro were incapable of developing root systems, their leaves curled over the abaxial surface, their inflorescences ceased elongation, and their flower buds died before opening, resulting in adult plants of miniature size (Figure 6A). The other three transformants were transferred to soil and grew under normal greenhouse conditions. Two of them (hereafter named OE1 and OE2) survived and showed a phenotype similar, but with a lesser degree of severity, to that of the two in vitro–grown transformants, such as small and curled leaves, dwarfed stature, and sterility (Figures 6C and 6D). A bushy phenotype was observed primarily because of a reduction of internode length and an increased proliferation of lateral shoots. A high proliferation of lateral shoots was observed on flower stalks as well as from the rosette (Figure 6E). Both the enhanced (prolonged) proliferation state and the formation of new primordia could be the cause of the high proliferation of lateral shoots.

A complete set of flower organs could be identified in OE1 and OE2 plants. However, the stamens were too short to reach the stigma for pollination. In addition, few pollen grains were found in anthers, and these anthers did not dehisce to release the pollen. The fertility of the female part was examined by hand pollination with pollen from wild-type plants. From eight siliques resulting from hand pollination, we obtained 56 seeds, which is much lower than the 300 to 400 seeds normally obtained from wild-type plants, indicating defects in female fertility. When these seeds were plated on germination medium, 13 failed to germinate, indicating defects in embryo formation. The other 43 seeds germinated, but only 1 showed resistance to kanamycin. This segregation ratio of 42 wild type to 14 (13 + 1) mutant is greater than the 1:1 ratio expected from the cross of a heterozygous mutant plant with a wild-type plant, indicating that GFP-Nicta;CYCA3;2 production could interfere with female gametogenesis. The kanamycin-resistant plant that resulted from the cross showed GFP fluorescence and had a phenotype similar to that of its maternal plant.

Cauline Leaves of Arabidopsis Plants Overexpressing GFP-Nicta;CYCA3;2 Display Reduced Endoreplication and Cell Size

To define the effects of gain of function at the cellular level, we analyzed the cytology of cauline leaves of GFP-Nicta;CYCA3;2 OE1 and OE2 plants. Cross-sections through the leaves revealed that the mutant leaves acquired the correct identity of different tissues: the vasculature, the adaxial and abaxial epidermis, and the mesophyll. Nevertheless, differences were observed when mutant and wild-type leaves were compared. In the wild-type leaf, the palisade cells that lie below the adaxial epidermis elongated and were arranged with their long axes perpendicular to the leaf surface, and the spongy mesophyll cells that lie between the palisade layer and the abaxial epidermis were smaller and more rounded (Figure 7A). In the mutant leaf, palisade cells were less elongated (Figure 7B), possibly indicating a lesser degree of differentiation from spongy mesophyll cells. In addition, the mutant leaf contained one less layer of spongy mesophyll cells.

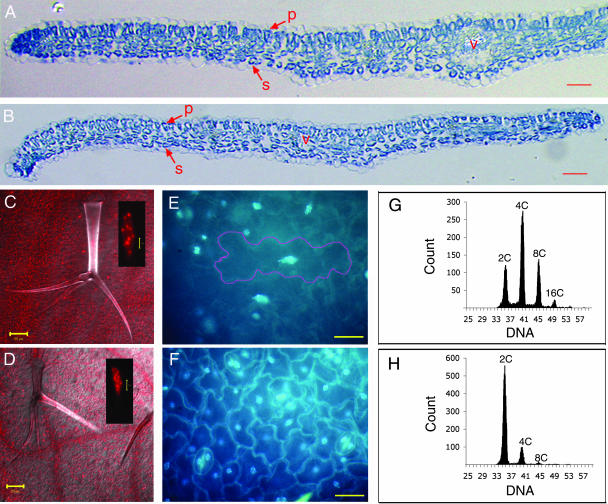

Figure 7.

Effects of GFP-Nicta;CYCA3;2 Overexpression on Cell Division, Differentiation, and Endoreplication in Arabidopsis Leaves.

(A) and (B) Transverse sections through the central part of a mature cauline leaf of a control plant (A) and a GFP-Nicta;CYCA3;2 OE1 plant (B). The palisade (p) and spongy mesophyll (s) cells as well as the central vasculature (v) are indicated.

(C) and (D) A wild-type trichome (C) and a GFP-Nicta;CYCA3;2 OE1 trichome (D). The insets show propidium iodide–stained nuclei.

(E) and (F) A wild-type epidermis (E) and a GFP-Nicta;CYCA3;2 OE1 epidermis (F). The nuclei are heavily stained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI). The weaker stained cytoplasm also is visualized as a thin layer surrounding the cell as a result of large vacuoles. Note that large polygon-shaped pavement cells containing big spindle-form nuclei (one of them is marked by a magenta line) are present in the wild type but absent in GFP-Nicta;CYCA3;2 OE1.

(G) and (H) Ploidy distribution of wild-type leaves (G) and GFP-Nicta;CYCA3;2 OE1 cauline leaves (H). The x and y axes display the relative DNA content (log scale) and the number of DAPI-stained nuclei, respectively.

Bars = 50 μm in (A) to (F) and 5 μm in the insets in (C) and (D).

More striking effects were observed on both the adaxial and abaxial epidermis of leaves, which are characterized by trichomes, pavement cells, and stomata guard cells. Arabidopsis leaf trichomes are unicellular hairs that undergo several rounds of endoreplication during maturation, leading to a characteristic form of three branches (Melaragno et al., 1993). Although no significant effects on morphology or number of branches were observed, both nuclear DNA content and the cell size of trichomes were reduced in the mutant (Figure 7D) compared with the wild type (Figure 7C). The cell areas of mutant and wild-type trichomes were 5,669 ± 1,411 (n = 52) and 10,638 ± 3,913 (n = 47) μm2, respectively. In addition, the large pavement epidermal cells with high DNA content observed in the wild-type leaf (Figure 7E) were absent from the mutant leaf (Figure 7F). In the mutant leaf, the pavement cells were more uniform in size and the numbers of pavement cells that separate guard cells from neighboring stomata were increased by a factor of ∼2. The ploidy levels of mutant and wild-type leaves were measured by flow cytometry. In wild-type leaves, cells presenting a DNA content of 2C, 4C, 8C, or 16C were detected (Figure 7G). In mutant leaves, most of the cells had a DNA content of 2C and a small proportion of cells had a DNA content 4C, but cells with a DNA content of >4C were barely detectable (Figure 7H). Together, these results show that the ectopic overexpression of GFP-Nicta;CYCA3;2 inhibits cell differentiation and endoreplication and modifies the proportion of cell size populations in leaves.

S-Phase–Specific Histone Gene Expression Is Upregulated in Arabidopsis Plants Overexpressing GFP-Nicta;CYCA3;2

To further determine the effects of the ectopic overexpression of GFP-Nicta;CYCA3;2 on cell cycle events, we analyzed the expression of cell cycle–specific genes in the OE1 and OE2 plants. Two genes were chosen for this study: the histone H4A748 and the cyclin Arath;CYCB1;1, which are expressed specifically during S-phase and M-phase, respectively (Chaubet et al., 1996; Menges and Murray, 2002). The transcript levels of these genes were compared between mutant and wild-type plants by semiquantitative reverse transcriptase–mediated PCR analysis using the constitutively expressed Actin2 gene as a standardization control. An upregulation of the histone H4A748 by a factor of 4- to 10-fold was found in cauline leaves, stems, and flower buds of mutant plants (Figure 8). By contrast, the transcript level of Arath;CYCB1;1 was not affected in mutant plants. These results suggest a specific enhancement of S-phase, through a premature entry and/or a delayed exit, by the ectopic overexpression of GFP-Nicta;CYCA3;2.

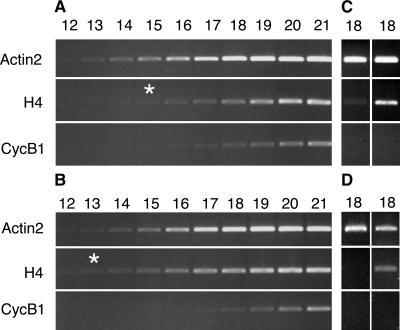

Figure 8.

Expression Analysis of Cell Cycle Genes in GFP-Nicta;CYCA3;2–Overexpressing Arabidopsis Plants.

The S-phase–specific histone H4 and the M-phase–specific cyclin Arath;CYCB1;1 were analyzed by semiquantitative reverse transcriptase–mediated PCR using Actin2 as a reference gene.

(A) and (B) Samples from flower buds of wild-type plants (A) and GFP-Nicta;CYCA3;2 OE1 plants (B).

(C) Samples from cauline leaves of wild-type (left lane) and GFP-Nicta;CYCA3;2 OE1 (right lane) plants.

(D) Samples from stems of wild-type (left lane) and GFP-Nicta;CYCA3;2 OE1 (right lane) plants.

The numbers above the lanes indicate the number of PCR cycles. The asterisks indicate that fewer PCR cycles are required in (B) than in (A) for an equal production of histone H4, indicating an increase of approximately fourfold in the H4 transcript level in GFP-Nicta;CYCA3;2 OE1 flower buds.

GFP-Nicta;CYCA3;2 Overexpression in Arabidopsis Impairs Shoot and Root Regeneration in Tissue Culture

The failure to obtain transgenic tobacco plants overproducing GFP-Nicta;CYCA3;2 from leaf disc transformation suggested an incompatible effect of the fusion protein on the regeneration process. We tested this hypothesis by in vitro tissue culture of leaf discs sampled from cauline leaves of wild-type and GFP-Nicta;CYCA3;2 overexpression Arabidopsis plants. Calli were regenerated from leaf discs after culture on medium containing high concentrations of auxin and cytokinin (Figures 9A and 9B). At this step, no significant differences were noted between control and GFP-Nicta;CYCA3;2 samples. The regenerated calli then were assayed for shoot regeneration on medium containing a decreased concentration of auxin. Abundant shoot regenerations were observed on the control calli (Figures 9C and 9D) but not on the GFP-Nicta;CYCA3;2 calli (Figures 9E and 9F). These late calli proliferated with unorganized masses of calli (Figure 9G), and the somatic embryo structure was not observed. Root regeneration also was assayed by transferring the calli onto medium in the absence of cytokinin. The GFP-Nicta;CYCA3;2 calli proliferated with unorganized masses of calli (Figure 9H), whereas the control calli formed many root initials (Figure 9I). Together, these results demonstrate that GFP-Nicta;CYCA3;2 overexpression maintains cells in an undifferentiated status that impairs shoot and root formation.

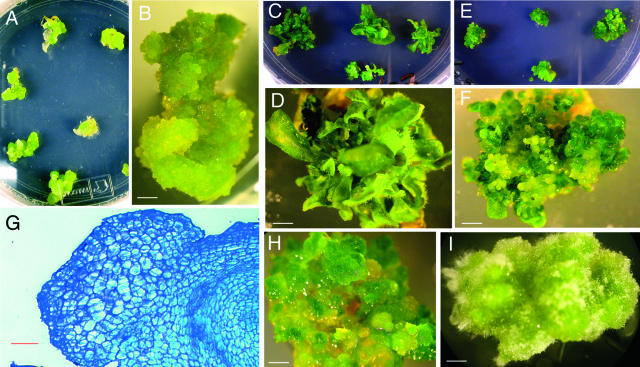

Figure 9.

Effects of GFP-Nicta;CYCA3;2 Overexpression on Callus Formation, and Subsequent Shoot and Root Regeneration from Arabidopsis Leaf Explants.

(A) and (B) Callus regeneration from leaf explants in the presence of high concentrations of auxin and cytokinin. Samples from wild-type and GFP-Nicta;CYCA3;2 OE1 cauline leaves gave similar results. Only calli from GFP-Nicta;CYCA3;2 OE1 samples are shown.

(C) and (D) Shoot regeneration from wild-type calli in the presence of a low concentration of auxin and a high concentration of cytokinin.

(E) and (F) Absence of shoot regeneration from GFP-Nicta;CYCA3;2 calli under the same conditions as described for (C) and (D).

(G) Section of a proliferating region of the callus in (F) showing an unorganized structure: the shoot, root, and somatic embryo structure could not be observed.

(H) and (I) Representatives of GFP-Nicta;CYCA3;2 and wild-type calli cultured in the absence of cytokinin showing the absence (H) and presence (I) of root regeneration, respectively.

Bars = 100 mm in (B), (D), (F), (H), and (I) and 50 μm in (G).

GFP-Nicta;CYCA3;2 Forms Active CDK Complexes in Arabidopsis

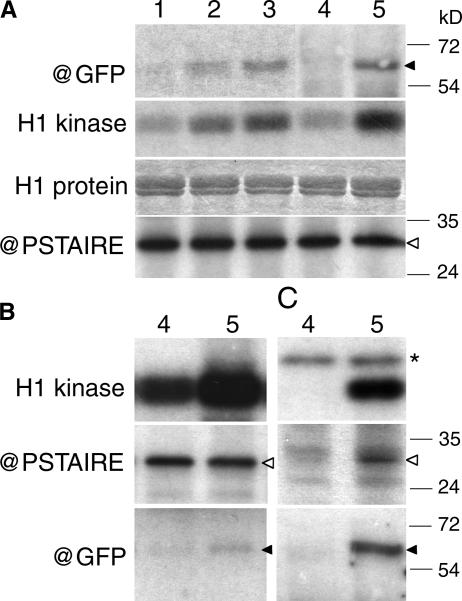

To verify if GFP-Nicta;CYCA3;2 forms active CDK complexes in Arabidopsis, we combined affinity and immunoprecipitation assays with protein gel blot analyses. Protein gel blotting with anti-GFP antibody revealed a band of the expected size for the fusion protein present specifically in samples of flower buds of the OE1 and OE2 plants and the GFP-Nicta;CYCA3;2 calli but absent from the wild-type controls (Figure 10A, top). Consistently, increases of p13suc1 affinity-purified CDK activity were detected in GFP-Nicta;CYCA3;2 samples (Figure 10A). The follow-up pulldown experiments were performed using undifferentiated calli because of their high level of GFP-Nicta;CYCA3;2 production and the good quantity of materials. When the same fractions of p13suc1 affinity-purified CDK were subjected to an analysis for histone H1 kinase activity as well as to protein gel blot analyses with anti-PSTAIRE and anti-GFP antibodies (Figure 10B), we observed a repeated increase of kinase activity and the presence of the fusion protein specifically in the GFP-Nicta;CYCA3;2 sample but a relatively equal amount of PSTAIRE-containing CDK in the control and GFP-Nicta;CYCA3;2 samples. Immunoprecipitation with the anti-GFP antibody resulted in H1 kinase activity present specifically in the GFP-Nicta;CYCA3;2 sample but absent from the control sample (Figure 10C). An endogenous protein was phosphorylated and found nonspecifically in immunoprecipitates from both GFP-Nicta;CYCA3;2 and control samples. Both PSTAIRE-containing CDK and GFP-Nicta;CYCA3;2 proteins were detected and present specifically in immunoprecipitate from the GFP-Nicta;CYCA3;2 sample but not in that from the control sample (Figure 10C). Together, these results demonstrate that GFP-Nicta;CYCA3;2 forms active kinase complexes with PSTAIRE-containing CDK proteins in Arabidopsis and that CDK proteins are present in nonlimiting, excess amounts.

Figure 10.

GFP-Nicta;CYCA3;2 Protein Accumulation and Its Associated CDK Activity in Arabidopsis.

(A) Total protein extracts from flower buds of wild-type (lane 1), GFP-Nicta;CYCA3;2 OE1 (lane 2), and GFP-Nicta;CYCA3;2 OE2 (lane 3) plants as well as from wild-type (lane 4) and GFP-Nicta;CYCA3;2 (lane 5) calli were analyzed for the presence of GFP-Nicta;CYCA3;2 protein and histone H1 kinase activity. GFP-Nicta;CYCA3;2 was detected by protein gel blot analysis using a rabbit polyclonal anti-GFP antibody (@GFP). H1 kinase activity was assayed on p13suc1-Sepharose affinity-purified CDK-cyclin complexes from 100 μg of total proteins (H1 kinase). Equal loading of histone H1 (H1 protein) and immunodetection of PSTAIRE-containing CDK (@PSTAIRE) are shown as controls.

(B) p13suc1-Sepharose affinity-purified fractions from 200 μg of total proteins of wild-type (lane 4) and GFP-Nicta;CYCA3;2 (lane 5) calli were assayed simultaneously for H1 kinase activity (H1 kinase), the presence of PSTAIRE-containing CDK (@PSTAIRE), and GFP-Nicta;CYCA3;2 protein (@GFP).

(C) Immunoprecipitates from the rabbit polyclonal anti-GFP antibody from 300 μg of wild-type (lane 4) and GFP-Nicta;CYCA3;2 (lane 5) calli were assayed simultaneously for H1 kinase activity (H1 kinase), the presence of PSTAIRE-containing CDK (@PSTAIRE), and GFP-Nicta;CYCA3;2 protein (@GFP).

Open arrowheads point to the positions of PSTAIRE-containing CDK proteins, closed arrows point to the positions of the GFP-Nicta;CYCA3;2 fusion proteins, and the asterisk indicates an unknown protein that is phosphorylated and present in both wild-type and GFP-Nicta;CYCA3;2 immunoprecipitates.

DISCUSSION

Is Nicta;CYCA3;2 a Functional Analog of Animal cyclin E?

The G1/S transition constitutes an important checkpoint of the mitotic cell cycle in all eukaryotes, in which the cells orientate to continue or to stop dividing. In animals, this transition process is coordinated by CDK-cyclin kinase complexes (Sherr, 1994; Coverley et al., 2002). Reentering the cell cycle from quiescence (G0 to G1 transition) involves cyclin D–CDK4/CDK6 complexes that are activated by developmental and nutritional cues. The cyclin E–CDK2 complex is involved in the mid G1-to-S transition by stimulating the assembly of prereplication complexes for DNA synthesis. The cyclin A–CDK2 complex promotes S-phase progression by activating DNA synthesis on the replication complexes that are already assembled and ensures one round of replication by inhibiting the assembly of new prereplication complexes (Coverley et al., 2002). In the model plant Arabidopsis, homology-based sequence analyses of the entire genome had identified and annotated 10 CYCD and 10 CYCA genes (Vandepoele et al., 2002). Strikingly, however, no homolog of cyclin E was identified from the Arabidopsis genome or reported from any other plant species. It is possible that some CYCD or CYCA genes might fulfill functions analogous to those of cyclin E in plants. Knockout of Arath;CYCD3;2 has no observable phenotype because of possible redundant functions by other CYCDs (Swaminathan et al., 2000). Functional analyses by ectopic overexpression and molecular characterizations revealed that Arabidopsis CYCD3;1 and CYCD2;1 and tobacco CYCD3;3 exhibit characteristics of animal cyclin D (Riou-Khamlichi et al., 1999; Cockcroft et al., 2000; Nakagami et al., 2002; Dewitte et al., 2003, and references therein). The functions of other CYCDs are currently uncharacterized.

Some molecular data indicate that different CYCAs could have different functions in plants. First, CYCAs can be classified into three distinct phylogenic groups, and representative member(s) for each group can be found in single plant species (Chaubet-Gigot, 2000; Vandepoele et al., 2002), suggesting that different group members are evolutionarily conserved to perform specific functions. Second, different CYCAs of tobacco show distinct expression profiles during the cell cycle (Reichheld et al., 1996), suggesting that different CYCAs perform sequentially required specific functions. Third, different CYCA proteins are found in particular cellular compartments. The maize A1-type cyclin Zeama;CYCA1;1 is localized in the cytoplasm in interphase, concentrated around the nucleus in prophase, and associates with the preprophase band, mitotic spindle, and phragmoplast during mitosis (Mews et al., 1997), whereas Medsa;CYCA2;2 is localized in the nucleus (Roudier et al., 2000). Nicta;CYCA3;1 (Criqui et al., 2001) and Nicta;CYCA3;2 (this work) also are both localized in the nucleus, but they differ by their presence and absence, respectively, from the nucleoli. These data suggest that different CYCA proteins may perform compartment-specialized functions. Fourth, different CYCA proteins might be regulated differently by proteolysis. Nicta;CYCA3;1 is degraded early after cells enter mitosis (Genschik et al., 1998; Criqui et al., 2001), whereas Zeama;CYCA1;1 is relatively stable, as shown by the fact that it can be detected throughout mitosis (Mews et al., 1997).

In spite of this accumulation of molecular data, a direct functional demonstration of plant CYCAs had long been missing. Recently, Roudier et al. (2003) demonstrated that antisense expression of Medsa;CYCA2;2 in alfalfa inhibits shoot and root development in tissue culture. We had shown previously that transient induction of the ectopic overexpression of Nicta;CYCA3;2 at local regions of the tobacco shoot apical meristem and leaf primordia can induce cell divisions (Wyrzykowska et al., 2002). However, when the induction was performed at the whole-plant level, significant effects on plant growth and development were not detected, in spite of highly increased levels of Nicta;CYCA3;2 mRNA (Wyrzykowska et al., 2002; our unpublished results). These previous results suggest that the role of Nicta;CYCA3;2 in cell division is dependent on the developmental context (Wyrzykowska et al., 2002) and that mechanism(s) exist to discriminate (or compensate) high levels of Nicta;CYCA3;2 mRNA. Consistent with this last assumption, Roudier et al. (2003) reported that overexpression of Medsa;CYCA2;2 does not result in the overproduction of Medsa;CYCA2;2 and has no effect on plant development. Here, we fused Nicta;CYCA3;2 to GFP, which allows the visualization of expression at the protein level. We demonstrated that GFP-Nicta;CYCA3;2 forms active CDK complexes in Arabidopsis and that its overproduction affects plant development dramatically.

Several of our observations indicate similarities between Nicta;CYCA3;2 function in plants and cyclin E function in animals. First, our antisense experiments demonstrated that Nicta;CYCA3;2 is involved in the reentry into cell division by differentiated tissues of leaves in which most of the cells are arrested in G1 (G0) phase (our cytometric data not shown). This is similar to the requirement of cyclin E in the G1/S transition in animals (Knoblich et al., 1994). Second, the gain of function by the ectopic expression of GFP-Nicta;CYCA3;2 inhibited cell differentiation and enhanced the expression of the S phase–specific histone gene. These data are consistent with the ectopic effects of cyclin E in inducing the premature entry into S-phase in animals (Knoblich et al., 1994; Richardson et al., 1995; Lukas et al., 1997). Third, contrary to its S-phase function, cyclin E activity needs to be reduced to allow endoreplication in Drosophila embryogenesis (Weiss et al., 1998; Edgar and Orr-Weaver, 2001). Similarly, ectopic overproduction of GFP-Nicta;CYCA3;2 inhibited endoreplication in Arabidopsis leaves. Together with the fact that the expression of Nicta;CYCA3;2 is activated particularly early at the G1/S transition (Reichheld et al., 1996), these similarities prompted us to propose that Nicta;CYCA3;2 may perform a function analogous to that of animal cyclin E in the control of plant cell division and differentiation. Future experiments will be necessary to characterize Nicta;CYCA3;2 at the molecular level for its analogous cyclin E and/or cyclin A function, particularly its relationship with the activation of the RBR/E2F pathway.

Cell Cycle and Embryo Formation

In contrast to the well-documented importance of cyclins in animal embryogenesis, the functions of cyclins in plant embryo formation have not been reported. Our results from antisense transgenic tobacco plants show that Nicta;CYCA3;2 is required for embryo formation and that its loss of function results in a panoply of embryonic phenotypes. The most severe phenotypes of the embryos, as dissected from germination-defective seeds, were the lack of morphologically recognizable cotyledons and embryonic roots (Figure 3C). Because the apical-basal axis is visible in these embryos, we believe that cotyledons and root primordia are initiated but that the cell divisions necessary for their growth are stopped at early stages. Distortions in embryo pattern formation also were shown by seedlings with abnormal phenotypes. Seedlings that lack the shoot meristem alone or together with the hypocotyl and the root (Figure 3B) were observed, indicating severe defects in the formation of the corresponding embryonic organs. A range of seedling phenotypes indicating distortions in embryo pattern formation also have been reported in transgenic Arabidopsis plants overexpressing a dominant-negative mutant of the CDKA;1 gene under the control of the 2S2 albumin promoter (Hemerly et al., 2000). The PSTAIRE-containing CDKA;1 protein is present constitutively during the cell cycle and can interact with all three (A, B, and D) types of plant cyclins (Stals and Inzé, 2001). Therefore, it is reasonable that the effects observed for the dominant-negative mutant CDKA;1 might be (partially) attributable to interactions of the protein with an Arabidopsis analog of Nicta;CYCA3;2. Four A3-type cyclins are present in the Arabidopsis genome (Vandepoele et al., 2002), but their functions are currently uncharacterized.

Endoreplication, Cell Expansion, and Postembryonic Development

Our gain-of-function experiments with transgenic Arabidopsis demonstrate that the ectopic overexpression of GFP-Nicta;CYCA3;2 results in a profound perturbation of postembryonic development. In Arabidopsis leaf epidermal cells, the arrest of cell division is followed by the onset of endoreplication, leading to increased nuclear DNA content and cell size (Traas et al., 1998). Plants overexpressing GFP-Nicta;CYCA3;2 have a dramatically decreased level of endoreplication in leaves, indicating an inhibition of cell differentiation. This reduces organ and plant size and modifies the morphology of the plant, revealing an important function of endoreplication and the corresponding cell expansion in pattern formation and development. These results are in contrast to those obtained with transgenic plants overexpressing the negative-dominant CDKs, Arath;CYCB1;1, or Arath;CYCD2;1, in which transgene expression modified the rate of cell division but not cell differentiation or plant morphology (Hemerly et al., 1995, Doerner et al., 1996, Cockcroft et al., 2000; Porceddu et al., 2001). Our results also differ from those obtained with transgenic Arabidopsis overexpressing ICK1/KRP1/KIS1, in which the reduced cell division and endoreplication were compromised by increased cell size, leading to plants with a different phenotype (Wang et al., 2000; De Veylder et al., 2001; Jasinski et al., 2002). Interestingly, overexpression of Arath;CYCD3;1 and E2Fa-DPa both induced hyperplasia but affected endoreplication oppositely, decreasing and increasing it, respectively, leading in both cases to profound defects in plant development (De Veylder et al., 2002; Dewitte et al., 2003; Kosugi and Ohashi, 2003).

Endoreplication consists of one or several rounds of DNA synthesis without mitosis, which requires exit from the mitotic cycle and transformation of the cell cycle to the endocycle by inhibiting the G2-to-M transition. Overexpression of Arath;CYCB1;2 in trichomes of Arabidopsis induced ectopic cell division, resulting in a reduced level of polyploidy of individual nuclei (Schnittger et al., 2002b). Consistent with the requirement for the inactivation of mitosis-promoting factors in endoreplication, downregulation of the fizzy-related ccs52 gene, which is involved in the destruction of mitotic cyclins, resulted in an increased level of polyploidy in alfalfa plants (Cebolla et al., 1999). The requirement of S-phase activity in plant endoreplication is suggested by the finding that polyploid maize endosperm contains high S-phase CDK activities (Grafi and Larkins, 1995).

However, the role of G1/S regulators in endoreplication is not understood completely. On the one hand, overexpression of E2Fa-DPa activates the expression of S-phase genes and induces endoreplication in Arabidopsis and tobacco (De Veylder et al., 2002; Kosugi and Ohashi, 2003). On the other hand, Arabidopsis plants overexpressing Arath;CYCD3;1, an activator of the RBR/E2F-DP pathway, exhibited a reduced level of endoreplication (Dewitte et al., 2003). Schnittger et al. (2002a) demonstrated that overexpression of Arath;CYCD3;1 in trichomes of Arabidopsis induces not only DNA replication but also ectopic cell division, suggesting that Arath;CYCD3;1 can promote mitosis in addition to the G1/S transition. Distinct from Arath;CYCD3;1, overexpression of GFP-Nicta;CYCA3;2 did not induce extra cell divisions (hyperplasia). This finding prompted us to propose that a failure to exit the mitotic cycle and/or to initiate DNA replication of the endocycle could cause the inhibition of endoreplication by GFP-Nicta;CYCA3;2. Consistent with a role of D3- and A3-type cyclins in the control of endoreplication, transcripts of Lyces;CYCD3;1 and Lyces;CYCA3;1 but not of Lyces;CYCA1;1, Lyces;CYCA2;1, Lyces;CYCB1;1, and Lyces;CYCB2;1 were detected in endoreplication gel tissue of tomato (Joubes et al., 2000). Expression analysis of Nicta;CYCA3;2 in endoreplication cells, at both the transcript and protein levels, might add to our understanding of its role in endoreplication.

Cell Dedifferentiation, Callus Formation, and Organogenesis

When explanted into culture under certain exogenous stimuli, many plant tissues dedifferentiate, proliferate to form calli, and undergo organogenesis. Hemerly et al. (1993) found that the expression of PSTAIRE-containing CDK correlates with the competence of cell division but that the release of other controls seems to be necessary for cell division to occur. Overexpression of Arath;CYCD3;1 can overcome the cytokinin requirement of callus formation in transgenic Arabidopsis leaf explants (Riou-Khamlichi et al., 1999), indicating its important role in the release of dedifferentiation and subsequent cell division. The Arabidopsis calli overexpressing Arath;CYCD3;1 are defective in shoot regeneration (Riou-Khamlichi et al., 1999). We found that the ectopic overproduction of GFP-Nicta;CYCA3;2 impairs shoot as well as root regeneration from transgenic Arabidopsis calli. It is likely that organogenesis requires a decreased level of CDK activity. This assumption is supported by the findings that ectopic overexpression of a rice CDK-activating kinase in tobacco converted root organogenesis to disorganized callus proliferation (Yamaguchi et al., 2003) and that the ectopic overexpression of Medsa;CYCB2;2 in tobacco inhibited root development from tissue-cultured leaf explants (Weingartner et al., 2003). Medsa;CYCB2;2 has been documented to have molecular properties similar to those of animal cyclin A (Weingartner et al., 2003).

In addition to the overexpression experiments, we found that antisense expression of Nicta;CYCA3;2 inhibited callus formation and shoot regeneration from transgenic tobacco leaf explants, indicating its requirement in cell division. However, it was difficult to monitor the change of Nicta;CYCA3;2 transcript level during the early phase of callus formation because the expression of Nicta;CYCA3;2 was extremely low in leaves and the dedifferentiation process leading to callus formation occurred in a small number of differentiated cells within the vascular bundle. Nevertheless, it is interesting that antisense expression of Medsa;CYCA2;2 did not interfere with callus and somatic embryo formation from transgenic alfalfa leaf explants, whereas subsequent shoot and root development was inhibited (Roudier et al., 2003). It is possible that different cyclins play different roles in dedifferentiation, proliferation, and redifferentiation. It was reported that different cyclin genes respond differently to exogenous stimuli. Medsa;CYCA2;2 expression is upregulated by auxin (Roudier et al., 2003), Arath;CYCD3;1 expression is activated by cytokinin (Riou-Khamlichi et al., 1999), and Arath;CYCD2;1 and Arath;CYCD4;1 expression is induced by sucrose (De Veylder et al., 1999; Riou-Khamlichi et al., 2000). Promoter isolation and characterization of Nicta;CYCA3;2 expression under different physiological conditions will help increase our understanding of its role in callus formation and organogenesis. Further characterization of cell cycle genes in organogenesis and embryogenesis will be required to understand the regulatory mechanisms of plant development. The observation that modified expression of cell cycle regulators interferes with plant growth, morphogenesis, and/or in vitro regeneration could have an important impact on biotechnology.

METHODS

Plant Materials

Tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum) and Arabidopsis thaliana (Columbia ecotype) plants were grown under greenhouse conditions. Tobacco BY2 (cv Bright Yellow 2) cell suspension was maintained by weekly subculture as described (Nagata et al., 1992).

Nicta;CYCA3;2 Constructs

To construct the GFP-Nicta;CYCA3;2 fusion, the entire coding region of Nicta;CYCA3;2 cDNA was amplified by PCR using the primers 5′-GCGGATCCATGAAGAAGCAAGAGAAAGAGGC-3′ and 5′-CCTCTAGATTACAATTGTCTCATATCTTC-3′. The PCR product was cloned into the pKS-GFP vector using BamHI and XbaI restriction sites, resulting in the in-frame fusion of GFP and Nicta;CYCA3;2. The GFP-Nicta;CYCA3;2 fusion fragment was isolated by a first digestion with XhoI, blunt-ending with Klenow, and a second digestion with SacI. It was introduced into the binary vector pBI121 (Clontech Laboratories, Palo Alto, CA) that had been opened previously by a first digestion with BamHI, blunt-ending with Klenow, and a second digestion with SacI, resulting in GFP-Nicta;CYCA3;2 under the control of the 35S promoter and the NOPALINE SYNTHASE terminator.

The antisense Nicta;CYCA3;2 construct was made by PCR amplification of Nicta;CYCA3;2 cDNA using the primers 5′-ATTAATGGTACCGTCGACTCTTGCTTTTCTTTGTTAGTTC-3′ and 5′-ATTAATGGTACCTCTAGATTGTATGTCCAAGCAGAAGCC-3′ and by insertion of the PCR fragment behind the TetO promoter of the binary vector pBinHyg-Tx (Gatz et al., 1992) using the KpnI and SalI restriction sites.

Plant Transformation and Tissue Culture

Tobacco plant transformation from leaf explants and the establishment of transgenic BY2 cell lines were as described previously (Shen, 2001). Callus regeneration from transgenic tobacco leaf explants was assayed under the same conditions used in transformation in the presence of 0.54 μM naphthylacetic acid (NAA) and 6.5 μM benzylaminopurine (BAP). Transgenic Arabidopsis plants were obtained by Agrobacterium tumefaciens–mediated transformation using the floral-dip method (Clough and Bent, 1998). Arabidopsis calli were regenerated from cauline leaf explants in the presence of 2.3 μM 2,4-D, 11.4 μM indoleacetic acid, and 3.2 μM BAP. Shoot regeneration from Arabidopsis calli was assayed in the presence of 0.54 μM NAA and 3.2 μM BAP, and root regeneration was assayed in the presence of 0.54 μM NAA alone.

RNA Analysis

Total RNA was prepared from plant tissues using the Trizol reagent kit (Gibco BRL). For RNA gel blot analysis, aliquots of 25 μg of RNA were analyzed by electrophoresis on formaldehyde-agarose gels, blotted onto Hybond-N nylon membranes (Amersham), and hybridized successively with different 32P-labeled probes under standard high-stringency conditions (Sambrook et al., 1989). The probes were as described previously (Reichheld et al., 1996; Chabouté et al., 1998). Reverse transcriptase–mediated PCR analyses were performed using the Avantage-2 kit according to the manufacturer's instructions (Clontech Laboratories). The gene-specific primers used in reverse transcriptase–mediated PCR were 5′-CGAGATAAACTAAATCTTCGC-3′ and 5′-AAACTCTAATTAACCACCGA-3′ for H4A748, 5′-AAGCTTCCATTGCAGACGA-3′ and 5′-AGCAGATTCAGTTCCGGTC-3′ for Arath;CYCB1;1, and 5′-AAGTCATAACCATCGGAGCTG-3′ and 5′-ACCAGATAAGACAAGACACAC-3′ for Actin2.

Histochemical GUS Activity Assay

Seedlings and embryos dissected from defective seeds of Nicta;CYCA3;2 AS4 at 8 days after germination, as well as embryos dissected from wild-type seeds at 2 days after germination, were incubated in 50 mM sodium phosphate buffer, pH 7, containing 0.2 mM 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-glucuronide, 0.5 mM potassium ferricyanide, 0.5 mM potassium ferrocyanide, and 0.5% (v/v) Triton X-100 at 37°C overnight. Photographs were taken of representative seedlings and embryos with a binocular microscope.

Immunoblotting, Immunoprecipitation, p13suc1-Sepharose Affinity Binding, and Histone H1 Kinase Assays

Immunoprecipitation, p13suc1-Sepharose affinity binding, histone H1 kinase reaction, and protein gel blotting were performed as described previously (Criqui et al., 2001). The affinity-purified anti-PSTAIRE rabbit polyclonal antibody was purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA) and used at a 4500-fold dilution in protein gel blot analyses. The affinity-purified anti-GFP rabbit polyclonal antibody was purchased from Molecular Probes (Leiden, The Netherlands) and used at a 2500-fold dilution in protein gel blot analyses and at a 150-fold dilution in immunoprecipitation. The mouse anti-GFP monoclonal antibody was purchased from Roche Applied Science (Meylan, France) and used at a 2500-fold dilution in protein gel blot detection of the GFP fusion protein from the immpunoprecipitates.

Histology and Microscopy

Microscopic examination was performed as described previously (Shen, 2001). For histological analysis, samples were fixed in 10% formalin, 5% acetic acid, and 50% ethanol, embedded in Paraplast (Oxford Labware, St. Louis, MO), and sectioned at 10 μm.

Flow Cytometry

After removal of the leaf petioles, leaf blades were chopped with a razor blade in Galbraith's buffer (Galbraith et al., 1983). After filtration over a 30-μm mesh, the nuclei were stained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole and analyzed with a UV flow cytometer (EPS Elite; Beckman-Coulter).

Upon request, materials integral to the findings presented in this publication will be made available in a timely manner to all investigators on similar terms for noncommercial research purposes. To obtain materials, please contact W.-H. Shen, wen-hui.shen@ibmp-ulp.u-strasbg.fr.

Acknowledgments

This article is dedicated to the memory of Claude Gigot (deceased in 1997), the leader for the initiation of this project. We thank Isabelle Bisson and Roberte Bronner for help with plasmid construction and histology, respectively. We are grateful to Chris Bowler and Fabio Formiggini (Laboratory of Molecular Plant Biology, Stazione Zoologica, Naples, Italy) for the H2B-CFP plasmid. We thank Thomas Potuschak for critically reading the manuscript. Y.Y. is supported by a fellowship from the Association Franco-Chinoise pour la Recherche Scientifique et Technique. The InterInstitut confocal microscopy plate form was cofinanced by the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, the Université Louis Pasteur, the Région Alsace, and the Association pour la Recherche sur le Cancer.

Article, publication date, and citation information can be found at www.plantcell.org/cgi/doi/10.1105/tpc.015990.

References

- Cebolla, A., Vinardell, J.M., Kiss, E., Olah, B., Roudier, F., Kondorosi, A., and Kondorosi, E. (1999). The mitotic inhibitor ccs52 is required for endoreduplication and ploidy-dependent cell enlargement in plants. EMBO J. 18, 4476–4484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chabouté, M.E., Combettes, B., Clément, B., Gigot, C., and Philipps, G. (1998). Molecular characterization of tobacco ribonucleotide reductase RNR1 and RNR2 cDNAs and cell cycle-regulated expression in synchronized plant cells. Plant Mol. Biol. 38, 797–806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaubet, N., Flénet, M., Clément, B., Brignon, P., and Gigot, C. (1996). Identification of cis-elements regulating the expression of an Arabidopsis histone H4 gene. Plant J. 10, 425–435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaubet-Gigot, N. (2000). Plant A-type cyclins. Plant Mol. Biol. 43, 659–675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clough, S.J., and Bent, A.F. (1998). Floral dip: A simplified method for Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 16, 735–743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cockcroft, C.E., den Boer, B.G.W., Healy, J.M.S., and Murray, J.A.H. (2000). Cyclin D control of growth rate in plants. Nature 405, 575–579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coverley, D., Laman, H., and Laskey, R.A. (2002). Distinct roles for cyclins E and A during DNA replication complex assembly and activation. Nat. Cell Biol. 4, 523–528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Criqui, M.C., Weingartner, M., Capron, A., Parmentier, Y., Shen, W.-H., Heberle-Bors, E., Bögre, L., and Genschik, P. (2001). Sub-cellular localisation of GFP-tagged tobacco mitotic cyclin during the cell cycle and after spindle checkpoint activation. Plant J. 28, 569–581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Veylder, L., Beeckman, T., Beemster, G.T., de Almeida Engler, J., Ormenese, S., Maes, S., Naudts, M., Van Der Schueren, E., Jacqmard, A., Engler, G., and Inze, D. (2002). Control of proliferation, endoreduplication and differentiation by the Arabidopsis E2Fa-DPa transcription factor. EMBO J. 21, 1360–1368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Veylder, L., Beeckman, T., Beemster, G.T., Krols, L., Terras, F., Landrieu, I., van der Schueren, E., Maes, S., Naudts, M., and Inze, D. (2001). Functional analysis of cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors of Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 13, 1653–1668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Veylder, L., de Almeida Engler, J., Burssens, S., Manevski, A., Lescure, B., Van Montagu, M., Engler, G., and Inze, D. (1999). A new D-type cyclin of Arabidopsis thaliana expressed during lateral root primordia formation. Planta 208, 453–462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dewitte, W., Riou-Khamlichi, C., Scofield, S., Healy, J.M., Jacqmard, A., Kilby, N.J., and Murray, J.A. (2003). Altered cell cycle distribution, hyperplasia, and inhibited differentiation in Arabidopsis caused by the D-type cyclin CYCD3. Plant Cell 15, 79–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doerner, P., Jorgensen, J.E., You, R., Steppuhn, J., and Lamb, C. (1996). Control of root growth and development by cyclin expression. Nature 380, 520–523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edgar, B.A., and Orr-Weaver, T.L. (2001). Endoreplication cell cycles: More for less. Cell 105, 297–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galbraith, D., Harkins, K.R., Maddox, J.R., Ayres, N.M., Sharma, D.P., and Firoozabady, E. (1983). Rapid flow cytometric analysis of the cell cycle in intact plant tissues. Science 220, 1049–1051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gatz, C., Frohberg, C., and Wendenburg, R. (1992). Stringent repression and homogeneous de-repression by tetracycline of a modified CaMV 35S promoter in intact transgenic tobacco plants. Plant J. 2, 397–404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genschik, P., Criqui, M.C., Parmentier, Y., Derevier, A., and Fleck, J. (1998). Cell cycle–dependent proteolysis in plants: Identification of the destruction box pathway and metaphase arrest produced by the proteasome inhibitor MG132. Plant Cell 10, 2063–2076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grafi, G., and Larkins, B.A. (1995). Endoreduplication in maize endosperm: Involvement of M phase-promoting factor inhibition and induction of S phase-related kinases. Science 269, 1262–1264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutierrez, C., Ramirez-Parra, E., Castellano, M.M., and del Pozo, J.C. (2002). G1 to S transition: More than a cell cycle engine switch. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 5, 480–486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemerly, A., de Almeida Engler, J., Bergounioux, C., Van Montagu, M., Engler, G., Inze, D., and Ferreira, P. (1995). Dominant negative mutants of the Cdc2 kinase uncouple cell division from iterative plant development. EMBO J. 14, 3925–3936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemerly, A.S., Ferreira, P., de Almeida Engler, J., Van Montagu, M., Engler, G., and Inze, D. (1993). cdc2a expression in Arabidopsis is linked with competence for cell division. Plant Cell 5, 1711–1723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemerly, A.S., Ferreira, P.C., Van Montagu, M., Engler, G., and Inze, D. (2000). Cell division events are essential for embryo patterning and morphogenesis: Studies on dominant-negative cdc2aAt mutants of Arabidopsis. Plant J. 23, 123–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jasinski, S., Riou-Khamlichi, C., Roche, O., Perennes, C., Bergounioux, C., and Glab, N. (2002). The CDK inhibitor NtKIS1a is involved in plant development, endoreduplication and restores normal development of cyclin D3;1-overexpressing plants. J. Cell Sci. 115, 973–982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joubes, J., Walsh, D., Raymond, P., and Chevalier, C. (2000). Molecular characterization of the expression of distinct classes of cyclins during the early development of tomato fruit. Planta 211, 430–439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knoblich, J.A., Sauer, K., Jones, L., Richardson, H., Saint, R., and Lehner, C.F. (1994). Cyclin E controls S phase progression and its down-regulation during Drosophila embryogenesis is required for the arrest of cell proliferation. Cell 77, 107–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosugi, S., and Ohashi, Y. (2003). Constitutive E2F expression in tobacco plants exhibits altered cell cycle control and morphological change in a cell type-specific manner. Plant Physiol. 132, 2012–2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J., Das, A., Yamaguchi, M., Hashimoto, J., Tsutsumi, N., Uchimiya, H., and Umeda, M. (2003). Cell cycle function of a rice B2-type cyclin interacting with a B-type cyclin-dependent kinase. Plant J. 34, 417–425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lepetit, M., Ehling, M., Chaubet, N., and Gigot, C. (1992). A plant histone gene promoter can direct both replication-dependent and -independent gene expression in transgenic plants. Mol. Gen. Genet. 231, 276–285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lukas, J., Herzinger, T., Hansen, K., Moroni, M.C., Resnitzky, D., Helin, K., Reed, S.I., and Bartek, J. (1997). Cyclin E-induced S phase without activation of the pRb/E2F pathway. Genes Dev. 11, 1479–1492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melaragno, J.E., Mehrotra, B., and Coleman, A.W. (1993). Relationship between endopolyploidy and cell size in epidermal tissue of Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 5, 1661–1668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menges, M., and Murray, J.A.H. (2002). Synchronous Arabidopsis suspension cultures for analysis of cell-cycle gene activity. Plant J. 30, 203–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mews, M., Sek, F.J., Moore, R., Volkmann, D., Gunning, B.E.S., and John, P.C.L. (1997). Mitotic cyclin distribution during maize cell division: Implications for the sequence diversity and function of cyclins in plants. Protoplasma 200, 128–145. [Google Scholar]

- Meyerowitz, E.M. (1997). Genetic control of cell division patterns in developing plants. Cell 88, 299–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller, H., Bracken, A.P., Vernell, R., Moroni, M.C., Christians, F., Grassilli, E., Prosperini, E., Vigo, E., Oliner, J.D., and Helin, K. (2001). E2Fs regulate the expression of genes involved in differentiation, development, proliferation, and apoptosis. Genes Dev. 15, 267–285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagata, T., Nemoto, Y., and Hasezawa, S. (1992). Tobacco BY-2 cell line as the “HeLa” cells in the biology of higher plants. Int. Rev. Cytol. 132, 1–30. [Google Scholar]

- Nakagami, H., Kawamura, K., Sugisaka, K., Sekine, M., and Shinmyo, A. (2002). Phosphorylation of retinoblastoma-related protein by the cyclin D/cyclin-dependent kinase complex is activated at the G1/S-phase transition in tobacco. Plant Cell 14, 1847–1857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakajima, K., and Benfey, P.N. (2002). Signaling in and out: Control of cell division and differentiation in the shoot and root. Plant Cell 14 (suppl.), S265.–S276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nieduszynski, C.A., Murray, J., and Carrington, M. (2002). Whole-genome analysis of animal A- and B-type cyclins. Genome Biol. 3, RESEARCH0070.1– RESEARCH 0070.8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Porceddu, A., Stals, H., Reichheld, J.P., Segers, G., De Veylder, L., Barroco, R.P., Casteels, P., Van Montagu, M., Inze, D., and Mironov, V. (2001). A plant-specific cyclin-dependent kinase is involved in the control of G2/M progression in plants. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 36354–36360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramirez-Parra, E., Frundt, C., and Gutierrez, C. (2003). A genome-wide identification of E2F-regulated genes in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 33, 801–811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reichheld, J.P., Chaubet, N., Shen, W.-H., Renaudin, J.P., and Gigot, C. (1996). Multiple A-type cyclins express sequentially during the cell cycle in Nicotiana tabacum BY2 cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93, 13819–13824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renaudin, J.P., et al. (1996). Plant cyclins: A unified nomenclature for plant A-, B- and D-type cyclins based on sequence organization. Plant Mol. Biol. 32, 1003–1018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson, H., O'Keefe, L.V., Marty, T., and Saint, R. (1995). Ectopic cyclin E expression induces premature entry into S phase and disrupts pattern formation in the Drosophila eye imaginal disc. Development 121, 3371–3379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riou-Khamlichi, C., Huntley, R., Jacqmard, A., and Murray, J.A. (1999). Cytokinin activation of Arabidopsis cell division through a D-type cyclin. Science 283, 1541–1544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riou-Khamlichi, C., Menges, M., Healy, J.M., and Murray, J.A. (2000). Sugar control of the plant cell cycle: Differential regulation of Arabidopsis D-type cyclin gene expression. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20, 4513–4521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roudier, F., Fedorova, E., Gyorgyey, J., Feher, A., Brown, S., Kondorosi, A., and Kondorosi, E. (2000). Cell cycle function of a Medicago sativa A2-type cyclin interacting with a PSTAIRE-type cyclin-dependent kinase and a retinoblastoma protein. Plant J. 23, 73–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roudier, F., Fedorova, E., Lebris, M., Lecomte, P., Gyorgyey, J., Vaubert, D., Horvath, G., Abad, P., Kondorosi, A., and Kondorosi, E. (2003). The Medicago species A2-type cyclin is auxin regulated and involved in meristem formation but dispensable for endoreduplication-associated developmental programs. Plant Physiol. 131, 1091–1103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sambrook, J., Fritsch, E.F., and Maniatis, T. (1989). Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual, 2nd ed. (Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press).

- Schnittger, A., Schobinger, U., Bouyer, D., Weinl, C., Stierhof, Y.D., and Hulskamp, M. (2002. a). Ectopic D-type cyclin expression induces not only DNA replication but also cell division in Arabidopsis trichomes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99, 6410–6415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnittger, A., Schobinger, U., Stierhof, Y.D., and Hulskamp, M. (2002. b). Ectopic B-type cyclin expression induces mitotic cycles in endoreduplicating Arabidopsis trichomes. Curr. Biol. 12, 415–420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnittger, A., Weinl, C., Bouyer, D., Schöbinger, U., and Hülskamp, M. (2003). Misexpression of the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor ICK1/KRP1 in single-celled Arabidopsis trichomes reduces endoreduplication and cell size and induces cell death. Plant Cell 15, 303–315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Setiady, Y.Y., Sekine, M., Hariguchi, N., Yamamoto, T., Kouchi, H., and Shinmyo, A. (1995). Tobacco mitotic cyclins: Cloning, characterization, gene expression and functional assay. Plant J. 8, 949–957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen, W.-H. (2001). NtSET1, a member of a newly identified subgroup of plant SET-domain-containing proteins, is chromatin-associated and its ectopic overexpression inhibits tobacco plant growth. Plant J. 28, 371–383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen, W.-H. (2002). The plant E2F-Rb pathway and epigenetic control. Trends Plant Sci. 7, 505–511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherr, C.J. (1994). G1 phase progression: Cycling on cue. Cell 79, 551–555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stals, H., and Inzé, D. (2001). When plant cells decide to divide. Trends Plant Sci. 6, 259–264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swaminathan, K., Yang, Y., Grotz, N., Campisi, L., and Jack, T. (2000). An enhancer trap line associated with a D-class cyclin gene in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 124, 1658–1667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Traas, J., Hülskamp, M., Gendreau, E., and Höfte, H. (1998). Endoreduplication and development: Rule without dividing? Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 1, 498–503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trimarchi, J.M., and Lees, J.A. (2002). Sibling rivalry in the E2F family. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 3, 11–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vandepoele, K., Raes, J., De Veylder, L., Rouze, P., Rombauts, S., and Inze, D. (2002). Genome-wide analysis of core cell cycle genes in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 14, 903–916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H., Zhou, Y., Gilmer, S., Whitwill, S., and Fowke, L.C. (2000). Expression of the plant cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor ICK1 affects cell division, plant growth and morphology. Plant J. 24, 613–623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weingartner, M., Pelayo, H.R., Binarova, P., Zwerger, K., Melikant, B., de la Torre, C., Heberle-Bors, E., and Bögre, L. (2003). A plant cyclin B2 is degraded early in mitosis and its ectopic expression shortens G2-phase and alleviates the DNA-damage checkpoint. J. Cell Sci. 116, 487–498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss, A., Herzig, A., Jacobs, H., and Lehner, C.F. (1998). Continuous Cyclin E expression inhibits progression through endoreduplication cycles in Drosophila. Curr. Biol. 8, 239–242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wyrzykowska, J., Pien, S., Shen, W.-H., and Fleming, A.J. (2002). Manipulation of leaf shape by modulation of cell division. Development 129, 957–964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi, M., Kato, H., Yoshida, S., Yamamura, S., Uchimiya, H., and Umeda, M. (2003). Control of in vitro organogenesis by cyclin-dependent kinase activities in plants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100, 8019–8023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Y., Wang, H., Gilmer, S., Whitwill, S., and Fowke, L.C. (2003). Effects of co-expressing the plant CDK inhibitor ICK1 and D-type cyclin genes on plant growth, cell size and ploidy in Arabidopsis thaliana. Planta 216, 604–613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]