Abstract

Transgenerational effects of parental experience on offspring immunity are well documented in the vertebrate literature (where antibodies play an obligatory role), but have only recently been described in invertebrates. We have assessed the impact of parental rearing density upon offspring disease resistance by challenging day-old locust hatchlings (Schistocerca gregaria) from either crowd- or solitary-reared parents with the fungal pathogen Metarhizium anisopliae var. acridum. When immersed in standardized conidia suspensions, hatchlings from gregarious parents suffered greater pathogen-induced mortality than hatchlings from solitary-reared parents. This observation contradicts the basic theory of positive density-dependent prophylaxis and demonstrates that crowding has a transgenerational influence upon locust disease resistance.

Keywords: insect immunity, maternal effects, fungal pathogens

1. Introduction

Although vertebrate offspring can inherit parental immune function through antibodies (Grindstaff et al. 2003), mechanisms of disease resistance in invertebrates have been thought to depend less upon prior experience (e.g. Roitt 1997). However, recent studies have found that invertebrate parents exposed to pathogens may produce offspring with increased resistance; this phenomenon is termed ‘transgenerational immune priming’ (Little et al. 2003; Sadd et al. 2005; Moret 2006; Sadd & Schmid-Hempel 2007). The ways in which invertebrate offspring resistance may relate to aspects of parental experience independent of pathogen pre-exposure, such as population density or rearing conditions, have not been systematically investigated.

Because the probability of encountering disease agents may increase with population density (McCallum et al. 2001), increased investment in immune defence is sometimes observed when hosts are crowded. This is known as density-dependent prophylaxis (DDP) (Wilson & Reeson 1998). In insect species exhibiting DDP, resistance to pathogen attack correlates positively with host population density (Wilson & Cotter 2008).

In accordance with the prediction of DDP, adult desert locusts (Schistocerca gregaria Forskål) from a gregarious culture were found to be more resistant to fungal challenge than solitary-reared equivalents (Wilson et al. 2002). Locusts exhibit density-dependent phase polyphenism, having the potential to exist in either the ‘solitarious’ or ‘gregarious’ phase depending on population density and experience of crowding, and it was proposed that these different immune responses are part of the suite of adaptive traits accompanying phase differentiation. However, because standard gregarious culture conditions are highly conducive to pathogen growth (Charnley et al. 1985), differential immune defence may be explained by the death of low-resistance gregarious individuals prior to testing, or induction of enhanced resistance through exposure to pathogens, rather than by phase-specific effects per se. Thus, the relative contributions of ontogeny and maternal effects to locust disease resistance remain unclear.

Locust phase state changes within an individual's lifetime in response to crowding. Behaviour and other physical and physiological traits also change as a function of parental rearing density due to chemically mediated maternal effects (Miller et al. 2008; Pener & Simpson 2009). Hatchlings of gregarious parents are more likely be in densely populated environments than those from solitarious parents (e.g. Bouaichi & Simpson 2003), and gregarious-parent hatchlings of S. gregaria are larger than solitarious-parent hatchlings and survive longer when starved (Uvarov 1966). The role, if any, of these or other transgenerational effects upon hatchling disease resistance has not been explored. Infection of parents with a fungal pathogen can affect offspring behaviour and coloration (Elliot et al. 2003), but there have been no assessments of locust hatchling immunity as a function of parental rearing density.

The aim of this study was to determine whether there is a transgenerational effect of parental rearing density upon offspring pathogen resistance in the desert locust (S. gregaria). Locust hatchlings (on the day of eclosion) were challenged by immersion into known concentrations of viable conidia of the acridid-specific fungal pathogen Metarhizium anisopliae var. acridum (a species used effectively as a locust biocontrol agent in the field; Lomer et al. 1997). To avoid any potentially confounding effects of hatchling culture conditions, solitarious and gregarious eggs were removed from their respective cultures and group-hatched in identical circumstances.

2. Material and methods

(a). Insects

Locusts (S. gregaria) from solitarious and gregarious cultures (from the same genetic background) were reared using standard techniques as detailed in Roessingh et al. (1993) at the Department of Zoology, University of Oxford, United Kingdom.

(b). Pathogen handling

M. anisopliae var. acridum (IMI 330189) conidia were obtained as a technical powder from CABI Bioscience and uniform aqueous suspensions were produced in a sonicator (stock solution: 50 mg conidia powder in 5 ml HPLC-grade water, sonicated for 10 min). Conidia concentration in suspension was quantified using a Neubauer haemocytometer and viability was determined by quantifying conidium germination on Sabouraud dextrose agar plates (Oxoid) after incubation at 25°C for 20 h (Goettel & Inglis 1997).

(c). Pathogen challenge of hatchlings from gregarious and solitarious parents

Freshly enclosed (>24 h old) hatchlings originating from gregarious (n = 51) and solitarious (n = 228) cultures were dipped individually (using fine forceps) into either distilled water or freshly sonicated aqueous suspensions of M. anisopliae var. acridum containing 5 × 103 conidia ml−1. Hatchlings were then housed in groups of 7–21 insects at 25°C (±0.5°C) in a total of 22 plastic containers (11 cm × 17 cm × 5 cm) into which fresh wheatgrass was placed daily. Treated and control insects were placed in different containers to prevent horizontal pathogen transmission, and insects from given solitarious mothers were placed in the same containers to assess parental effects on resistance. Survivorship was assessed daily for 14 days. Dead insects were removed immediately from group environments and random samples of these (n = 50 inoculated; n = 30 control, split equally between solitarious and gregarious colonies) were placed into humidity chambers to check for sporulation.

(d). Statistical analysis

Data were analysed in SPSS 14 (SPSS Inc.). Death rates were modelled using Cox regression survivorship analysis where pathogen presence was cast as a simple time-dependent covariate equal to (log(time) × (pathogen concentration)).

3. Results

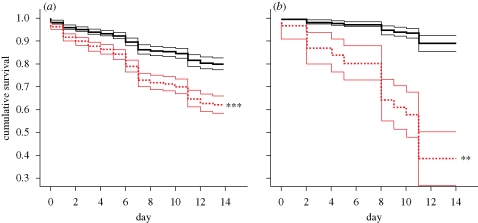

Pathogen exposure significantly reduced survivorship in populations of hatchlings from both solitarious and gregarious parents (Wald = 12.739, d.f. = 1, p < 0.001; Wald = 7.381, d.f. = 1, p = 0.007, respectively; figure 1). Fewer solitarious-parent hatchlings died owing to pathogen challenge than hatchlings from gregarious parents (61 and 38% survival at day 14, respectively; figure 1, table 1). The survivorship curves of control hatchlings from solitarious and gregarious parents were not significantly different (Wald = 0.221, d.f. = 1, p = 0.638; black lines, figure 1), and control mortality did not differ as a function of particular housing container (Wald = 7.56, d.f. = 10, p = 0.672). Furthermore, hatchlings from solitarious parents did not react differently to the pathogen challenge depending upon the identity of their solitarious mother (Wald = 9.10, d.f. = 7, p = 0.246). Sporulation, indicating mycosis, was observed in 94 per cent of inoculated individuals who died prior to trial termination and in none of the tested control (water-immersed) insects.

Figure 1.

(a,b) Pathogen challenge affects survivorship of hatchlings from both (a) solitarious and (b) gregarious parents. Solid black lines indicate control treatments and dashed red lines indicate pathogen treatments. Thin, flanking lines show standard errors. Fungal pathogens increase mortality in both groups, but the impact upon gregarious-parent insects is significantly greater (see table 1). (n = 51 gregarious; n = 228 solitarious; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001.)

Table 1.

Cox survivorship analysis of fungus-treated locust hatchlings from solitarious and gregarious parents. (*p<0.05; ***p<0.001.)

| Wald statistic | d.f. | p | odds ratio | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| pathogen | 13.120 | 1 | <0.001*** | 3.388 |

| phase of hatchling parent (solitarious or gregarious) | 2.440 | 1 | 0.118 | 0.364 |

| pathogen×phase | 4.793 | 1 | 0.029* | 5.288 |

4. Discussion

Hatchlings from crowded parents were more vulnerable to fungal attack than hatchlings from isolated (solitarious) parents (figure 1, table 1). Although previous studies have examined insect immunity in offspring of pathogen-challenged parents (Moret 2006; Sadd & Schmid-Hempel 2007), parental population density has not previously been shown to affect hatchling pathogen resistance.

Fungal inoculation by immersion provides dosages proportional to insect surface area: larger insects receive smaller dosages per unit weight because surface area scales more slowly than volume with increasing size. Considering the significantly larger size of S. gregaria hatchlings from gregarious relative to solitarious parents (Uvarov 1966; Injeyan & Tobe 1981; Tanaka & Maeno 2008; Pener & Simpson 2009), their comparatively poor pathogen resistance runs counter to expectation based upon dosage, and is particularly striking.

Despite the increased likelihood of hatching into high-density populations, gregarious-mother hatchlings were less resistant to pathogen challenge; this is contrary to the result predicted by DDP (Wilson & Reeson 1998; Wilson et al. 2002). The high relative resistance of solitarious hatchlings is nevertheless in accord with data from Wilson et al. (2003), in which five of six solitarious lepidopteran species showed increased correlates of immune function (haemocyte count and phenoloxidase activity) relative to phylogenetically matched gregarious species. Futhermore, Pie et al. (2005) found that termites at high and low population densities had comparable resistance to a fungal challenge, suggesting that eusocial insects may not conform to the DDP hypothesis.

The present results support the contention that DDP is best understood in a broader context of both within- and between-group infection rates; the risk of pathogen exposure may be minimal for group members whose between-group infection risk is low enough to compensate for potentially high transmission within the group (Wilson et al. 2003). Indeed, the recent application of ‘percolation theory’ to disease spread demonstrates that the spatial clustering of host individuals (as in gregarious locust populations) can reduce the ability of natural enemies to move between resources on a larger scale (Reynolds et al. 2008; Wilson 2009).

In addition to variation in exposure to disease agents, distinct life-history and survival strategies may also underlie the observed reduction in the pathogen resistance of hatchlings from crowded parents. Because solitarious nymphs take longer to reach their reproductive potential (Pener & Yerushalmi 1998), they are subject to greater time-dependent mortality risks (including pathogen exposure), which may justify parental investment in offspring immune function. Meanwhile, gregarious locusts are adapted for migration—for example through their larger size, longer wings, increased activity levels, greater fat storage and other phase differences (Pener & Simpson 2009)—and, therefore, may have fewer energetic or nutritional resources available for immune defence. Accordingly, resource allocation trade-offs at the maternal and/or offspring levels may contribute to limited pathogen resistance in insects from gregarious parents. Future studies may investigate how other aspects of the parental environment affect offspring immunity and whether parents trade off their own resistance against that of their progeny.

Acknowledgment

Thanks are extended to I. Couzin and D. Hughes for helpful discussions. G.A.M. was funded by an NSF Graduate Research Fellowship (USA) and an Oxford Clarendon Award (UK). J.K.P. was funded by DEFRA (Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs, UK). Rothamsted Research is an institute of the BBSRC (Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council, UK). Metarhizium anisopliae conidia were kindly provided by CABI Biosciences, UK. We are grateful for the commentary of two anonymous reviewers.

References

- Bouaichi A., Simpson S. J.2003Density-dependent accumulation of phase characteristics in a natural population of the desert locust Schistocerca gregaria. Physiol. Entomol. 28, 25–31 (doi:10.1046/j.1365-3032.2003.00317.x) [Google Scholar]

- Charnley A. K., Hunt J., Dillon R. J.1985The germ-free culture of desert locusts, Schistocerca gregaria. J. Insect Physiol. 31, 477–485 (doi:10.1016/0022-1910(85)90096-4) [Google Scholar]

- Elliot S. L., Blanford S., Horton C. M., Thomas M. B.2003Fever and phenotype: transgenerational effect of disease on desert locust phase state. Ecol. Lett. 6, 830–836 (doi:10.1046/j.1461-0248.2003.00487.x) [Google Scholar]

- Goettel M. S., Inglis G. D.1997Fungi: hyphomycetes. In Manual of techniques in insect pathology (ed. Lacey L. A.), pp. 213–249 New York, NY: Academic Press [Google Scholar]

- Grindstaff J. L., Brodie E. D., Ketterson E. D.2003Immune function across generations: integrating mechanism and evolutionary process in maternal antibody transmission. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B 270, 2309–2319 (doi:10.1098/rspb.2003.2485) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Injeyan H. S., Tobe S. S.1981Phase polymorphism in Schistocerca gregaria: reproductive parameters. J. Insect Physiol. 27, 97–102 (doi:10.1016/0022-1910(81)90115-3) [Google Scholar]

- Little T. J., O'Connor B., Colegrave N., Watt K., Read A. F.2003Maternal transfer of strain-specific immunity in an invertebrate. Curr. Biol. 13, 489–492 (doi:10.1016/S0960-9822(03)00163-5) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lomer C. J., Prior C., Kooyman C.1997Development of Metarhizium sp. for the control of grasshoppers and locusts. Memoirs Entomol. Soc. Canada, 265–286 [Google Scholar]

- McCallum H., Barlow N., Hone J.2001How should pathogen transmission be modelled? Trends Ecol. Evol. 16, 295–300 (doi:10.1016/S0169-5347(01)02144-9) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller G. A., Islam M. S., Claridge T. D. W., Dodgson T., Simpson S. J.2008Swarm formation in the desert locust Schistocerca gregaria: isolation and NMR analysis of the primary maternal gregarizing agent. J. Exp. Biol. 211, 370–376 (doi:10.1242/jeb.013458) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moret Y.2006‘Trans-generational immune priming’: specific enhancement of the antimicrobial immune response in the mealworm beetle, Tenebrio molitor. Proc. R. Soc. B 273, 1399–1405 (doi:10.1098/rspb.2006.3465) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pener M. P., Simpson S. J.2009Locust phase polyphenism: an update. Advances in Insect Physiology, vol. 36 San Diego, CA: Academic Press [Google Scholar]

- Pener M. P., Yerushalmi Y.1998The physiology of locust phase polymorphism: an update. J. Insect Physiol. 44, 365–377 (doi:10.1016/S0022-1910(97)00169-8) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pie M., Rosengaus R., Calleri D. I., Traniello J.2005Density and disease resistance in group-living insects: do eusocial species exhibit density-dependent prophylaxis? Ethol. Ecol. Evol. 17, 41–50 [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds A., Sword G., Simpson S., Reynolds D.2008Predator percolation, insect outbreaks and phase polyphenism. Curr. Biol. 19, 20–24 (doi:10.1016/j.cub.2008.10.070) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roessingh P., Simpson S. J., James S.1993Analysis of phase-related changes in behavior of desert locust nymphs. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B 252, 43–49 (doi:10.1098/rstb.1993.0044) [Google Scholar]

- Roitt I. M.1997Essential immunology Oxford, UK: Blackwell Publishing [Google Scholar]

- Sadd B., Kleinlogel Y., Schmid-Hempel R., Schmid-Hempel P.2005Trans-generational immune priming in a social insect. Biol. Lett. 1, 386 (doi:10.1098/rsbl.2005.0369) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadd B. M., Schmid-Hempel P.2007Facultative but persistent trans-generational immunity via the mother's eggs in bumblebees. Curr. Biol. 17, 1046–1047 (doi:10.1016/j.cub.2007.11.007) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka S., Maeno K.2008Maternal effects on progeny body size and color in the desert locust, Schistocerca gregaria: examination of a current view. J. Insect Physiol. 54, 612–618 (doi:10.1016/j.jinsphys.2007.12.010) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uvarov B. P.1966Grasshoppers and locusts: a handbook of general acridology, vol 1 London, UK: Cambridge University Press [Google Scholar]

- Wilson K.2009Evolutionary ecology: old ideas percolate into ecology. Curr. Biol. 19, 21–23 (doi:10.1016/j.cub.2008.11.049) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson K., Cotter S. C.2008Density-dependent prophylaxis in insects. In Phenotypic plasticity of insects: mechanisms and consequences (eds Whitman D. W., Ananthakrishnan T. N.), pp. 381–420 Enfield, NH: Science Publishers [Google Scholar]

- Wilson K., Knell R., Boots M., Koch-Osborne J.2003Group living and investment in immune defence: an interspecific analysis. J. Anim. Ecol. 72, 133–143 (doi:10.1046/j.1365-2656.2003.00680.x) [Google Scholar]

- Wilson K., Reeson A. F.1998Density-dependent prophylaxis: evidence from lepidoptera–baculovirus interactions? Ecol. Entomol. 23, 100–101 (doi:10.1046/j.1365-2311.1998.00107.x) [Google Scholar]

- Wilson K., Thomas M. B., Blanford S., Doggett M., Simpson S. J., Moore S. L.2002Coping with crowds: density-dependent disease resistance in desert locusts. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 99, 5471–5475 (doi:10.1073/pnas.082461999) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]