Abstract

The life history of Confuciusornis sanctus is controversial. Recently, the species’ body size spectrum was claimed to contradict osteohistological evidence for a rapid, bird-like development. Moreover, sexual size dimorphism was rejected as an explanation for the observed bimodal size distribution since the presence of elongated rectrices, an assumed ‘male’ trait, was uncorrelated with size. However, this interpretation (i) fails to explain the size spectrum of C. sanctus which is trimodal rather than bimodal, (ii) requires implausible neonate masses and (iii) is not supported by analogy with sexual dimorphisms in modern birds, in which elongated central rectrices are mostly sex-independent. Available information on C. sanctus is readily reconciled if we assume a bird-like life history, as well as a pronounced sexual size dimorphism and sexually isomorphic extravagant feathers as frequently observed in extant species.

Keywords: bird evolution, Confuciusornis sanctus, life history, morphometrics, sexual dimorphism

1. Introduction

The life histories of dinosaurs and early birds provide keys to the understanding of the reptilian/avian transition (Padian et al. 2001). The Lower Cretaceous basal bird Confuciusornis sanctus (Chiappe et al. 1999) provides a rare opportunity for a life-history reconstruction since hundreds of specimens are available, which fell victim to mass mortality events related to tuff depositions (Guo & Wang 2002). Confuciusornis sanctus shows a large range of body sizes that had been interpreted as indicative of reptile-like indeterminate growth (Hou et al. 1996). However, subsequent osteohistological investigations suggested a more bird-like, short growth burst in juveniles (de Ricqlès et al. 2003). This hypothesis was questioned by Chiappe et al. (2008), who reported a bimodal size distribution which they interpreted as immature and mature stages separated by a ‘mid-development phase of exponential growth’. We have analysed the size spectrum of an enlarged sample using corrected allometric relationships established in modern birds, and reached different conclusions.

2. Material and methods

Long bone measurements were compiled from various sources (see the electronic supplementary material S1) and pairwise geometric mean functional relationships (GMFR), a ‘Model II’ description of correlations (Imbrie 1956; Draper & Smith 1998), were computed. Body masses estimated from femur lengths (table 1) were plotted as a cumulative density. The sum of three sigmoidal ‘step-stool equations’ (the upper asymptote of one set the baseline for the next) was fitted to this plot with body mass as a dependent variable (SigmaPlot v. 7.101, SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA) following manual pre-fitting (Peters & Baskin 2006). This function's derivative (computed numerically) provided a continuous body mass spectrum.

Table 1.

Empirical allometric relationships in extant birds that were used to estimate body masses. (Because published relationships are regression analyses that rest on the assumption that one of the two variables is error-free, we computed GMFR that avoid this unwarranted premise.)

| parameters compared | source of data and published regression | published regression | GMFR used in present study |

|---|---|---|---|

| femur length (F; mm) and body mass (M; kg) | Prange et al. (1979) | F = 61.64 M0.359 (excluding ratites) | F = 60.651 M0.3549 (including ratites) |

| neonate body mass (N; kg) and female body mass (B; kg) | Heinroth (1922), analysed by Blueweiss et al. (1978) | N = 0.0329 B0.69 (transformed for consistency of units) | N = 0.0356 B0.760 |

3. Results

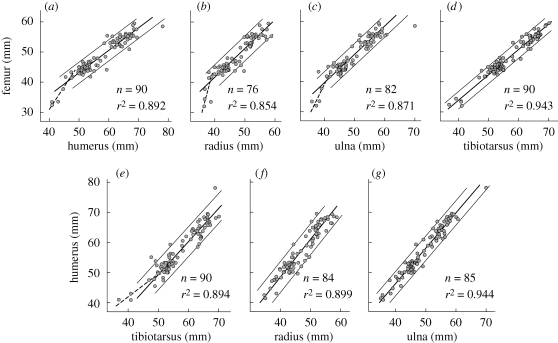

Long bone lengths of C. sanctus distributed into three clusters (figure 1; particularly evident in d). Specimens with the shortest bones tended to have overproportionally long wing bones (figure 1a,b,c,e). Consequently, coefficients of determination were lower for pairs of one leg and one wing bone than for pairs from the same limb (figure 1). The plots of correlations allowed the identification of outliers (see the electronic supplementary material S1) that were excluded from the subsequent analysis of the body size spectrum.

Figure 1.

Selected correlations between long bone lengths of C. sanctus. Bold lines, GMFR; thin lines, twice the s.d. of the data scattering around the GMFR. In plots of wing bones versus leg bones, a separate GMFR was calculated for the smallest birds (dashed lines) which deviated from allometry. (a) Femur/humerus. Two GMFRs shown for femur shorter/longer than 41.9 mm. (b) Femur/radius. Two GMFRs for femur shorter/longer than 41.5 mm. (c) Femur/ulna. Two GMFRs shown for femur shorter/longer than 41.75 mm. (d) Femur/tibiotarsus. (e) Humerus/tibiotarsus. Two GMFRs given for tibiotarsus shorter/longer than 47 mm. (f) Humerus/radius. (g) Humerus/ulna.

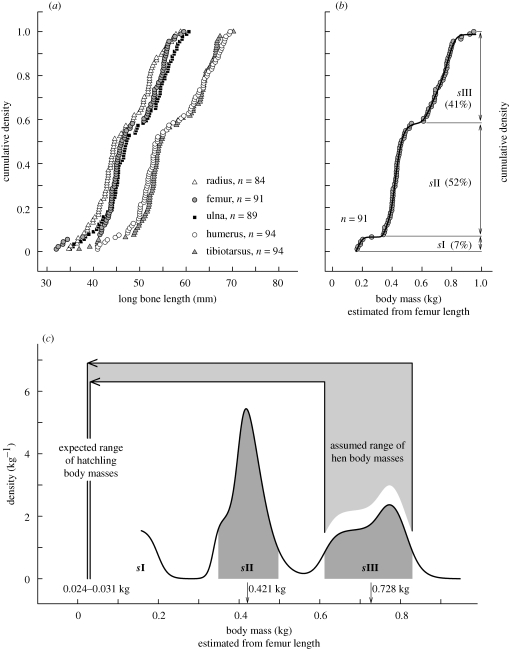

Cumulative density plots of all five bone lengths showed similar patterns (figure 2a). To reconstruct the development of body mass (M) over the bird's lifetime, we transformed femur lengths into body masses according to their empirical allometric relationship in modern birds (table 1). In a cumulative density plot of M, the three clusters of bone lengths showed as size classes sI, sII and sIII (figure 2b). The derivative of a continuous function fitted to this plot gave the body mass spectrum (figure 2c).

Figure 2.

Spectrum of body mass estimated from femur length in C. sanctus. (a) Cumulative density plots show similar patterns for all five long bone lengths. (b) Cumulative density plot of body mass estimates; three size classes (sI, sII, sIII) are indicated. The bold line is a continuous function fitted to the data, representing the cumulative density profile. (c) Body mass spectrum (derivative of the cumulative density profile in (b)). The central 90 per cent of sII and sIII are shaded; mean values (arrows) were determined numerically. Assuming that sIII includes mature females, hatchling masses corresponding to the central 90 per cent of sIII were estimated using the empirical allometric relationship in modern birds.

Using the mass spectrum, we estimated hatchling masses. Modern birds with mature body masses covering the central 90 per cent of the estimated body mass range of sIII would be expected to weigh 24–31 g as hatchlings (figure 2c, table 1); expected neonate masses for modern reptiles would be substantially smaller (Blueweiss et al. 1978). Extant kiwis (Apteryx spp.) are the most extreme deviationists from standard allometry, as neonates are almost five times heavier than predicted (Prinzinger & Dietz 2002). If sIII hens were similar overachievers, their hatchlings would have weighed up to 150 g. Thus, it appears implausible that C. sanctus neonates weighed more than 150 g; most probably, they did not exceed 31 g. In any case, hatchlings had to multiply their weight before they entered sII. Consequently, sII and sIII cannot represent developmental stages separated by a phase of rapid growth unless C. sanctus had a unique growth curve with two growth bursts separated by the stationary phase, sII.

A less speculative interpretation suggests itself. Sexual size dimorphism may have occurred in dinosaurs (Horner 2000) and would not be unexpected in basal birds. The size dimorphism index ([Mlarger class]/[Msmaller class] − 1) for sII (0.42 kg) and sIII (0.73 kg) is 0.74 which falls within the ranges of male-biased as well as female-biased sexual size dimorphisms in extant birds (Fairbairn 1997). Therefore, sexual size dimorphism plausibly explains the existence of two non-juvenile size groups in C. sanctus. It remains unclear whether this dimorphism was male or female biased, although we assumed the latter in our estimates of neonate masses.

The relative scarcity of juveniles (sI) and the complete absence of the even smaller hatchlings could be explained geologically (size-dependent preservation bias), developmentally (inability of young birds to visit sites where adults congregated and ultimately were buried) and ecologically (age-dependent preferences for different habitats). It needs to be kept in mind, though, that our dataset consists of random samples taken from an unknown number of death assemblages and that each assemblage originated from one catastrophic event. Thus, the size spectrum we analysed represents a combination of random snapshots of the population structure, each taken at a defined point in the reproductive cycle of C. sanctus. Consequently, the absence of neonates and scarcity of juveniles in the fossil record could also be owing to rapid growth over a short juvenile period, a limited breeding season or both.

4. Discussion

Our conclusions disagree with Chiappe et al. (2008) on important points. First, long bones do not have ‘nearly isometric scaling’ across the size range of C. sanctus fossils. Rather, the smallest individuals tend to have relatively longer wing bones (figure 1), a phenomenon known from juvenile domestic chickens (Latimer 1927). Such developmental shifts in body proportions may be adaptive in birds (O'Connor 1977). Second, sII individuals cannot represent the youngest developmental stage of C. sanctus as this would imply an implausible hen/hatchling mass ratio. Third, the apparent size dimorphism of C. sanctus fossils is in fact a size trimorphism (figure 2), ruling out the possibility that sI, sII and sIII are successive developmental stages unless the species had a bisigmoidal growth curve, which would be unique among amniotes. Therefore, we propose that sII and sIII are adults showing sexual size dimorphism. Accordingly, the rare sI birds must be juveniles, which actually could be predicted to be scarce since the osteohistology of C. sanctus indicates a short growth period at a young age as is typical of most modern birds (de Ricqlès et al. 2003). Consequently, the assertion that these osteohistological findings are ‘at odds with the size distribution’ (Chiappe et al. 2008) cannot be upheld.

Ever since pairs of elongated central tail feathers were found in a small subset of C. sanctus individuals, the birds carrying these ‘ornaments’ were suspected to be males (Martin et al. 1998; Hou et al. 1999). As elongated central rectrices occur in C. sanctus of all sizes (Peters & Ji 1999; electronic supplementary material S2), Chiappe et al. (2008) excluded sexual size dimorphism as a possibility since ‘such dimorphism would be oddly uncorrelated with the most apparent sexual trait’. As there is no direct palaeontological evidence suggesting that long-tailed C. sanctus were males, the argument is essentially an actualistic one, that is: based on an assumed analogy between fossil and extant species. In the words of Zhang et al. (2008, p. 139), in ‘the early Cretaceous, the sexual dimorphism of feathers in early birds [was] much like that of modern birds’. We decided to take this statement seriously. Because different types of elongated tails (elongated central rectrices, elongated lateral rectrices, graduated rectrices) have different aerodynamic effects, they evolve under distinct sets of selective forces and must not be confounded (Evans 2004). Therefore, we screened the literature specifically for the occurrence of pairs of elongated central rectrices, and found that, contrary to widespread belief, their presence as such is not a reliable sexual character in the vast majority of extant bird species that possess such pintails (see the electronic supplementary material S3). Thus, the notion that C. sanctus can be sexed based on the presence of elongated rectrices has neither palaeontological nor actualistic support and provides no valid argument against our interpretation of the species’ body size spectrum as a sexual size dimorphism.

In the extant pheasant-tailed Jacana (Hydrophasianus chirurgus), females weigh almost twice as much as males. Both sexes carry elongate ornamental rectrices, but only during the breeding season (Jenni 1996). If randomly sampled, the distributions of body size and extravagant tails in adult H. chirurgus will mirror that observed in the sII and sIII classes of C. sanctus. But unlike juvenile Jacanas, even some of the smallest C. sanctus possessed elongate rectrices (see the electronic supplementary material S2), suggesting that these feathers lacked a direct relationship to reproduction altogether and were present in all individuals regardless of age. The absence of these unwieldy appendages in the majority of specimens could then be explained by loss post-mortem. On the other hand, pintails confer little aerodynamic benefit (Thomas 1997); if they neither helped flight nor had a role in reproduction, what might have been their function in C. sanctus? Stress-induced shedding of tail feathers may function as an antipredator defence in modern birds (Møller et al. 2006) and can lead to fright molt (Dathe 1955). The elongate rectrices may have had a similar function in C. sanctus and may have been shed by stressed animals when the mass mortality events occurred.

If it is correct that juvenile C. sanctus are underrepresented in the fossil record because the juvenile stage was short and breeding occurred seasonally, then fossilized juveniles will not be distributed randomly among adults, but will be restricted to tuff layers that happened to sediment in or shortly after the breeding season. This interesting prediction can be directly tested in saxo.

Acknowledgements

We thank William E. Cooper, José Javier Cuervo, James O. Farlow and Frank V. Paladino for critical discussion.

References

- Blueweiss L., Fox H., Kudzma V., Makashima D., Peters R., Sams S.1978Relationships between body size and some life history parameters. Oecologia 37, 257–272 (doi:10.1007/BF00344996) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiappe L. M., Ji S., Ji Q., Norell M. A.1999Anatomy and systematics of the Confuciusornithidae (Theropoda: Aves) from the late mesozoic of northeastern China. Bull. Am. Mus. Nat. Hist. 242, 1–89 [Google Scholar]

- Chiappe L. M., Marugán-Lobón J., Ji S., Zhou Z.2008Life history of a basal bird: morphometrics of the early cretaceous Confuciusornis. Biol. Lett. 4, 719–723 (doi:10.1098/rsbl.2008.0409) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dathe H.1955Über die Schreckmauser. J. Ornithol. 96, 5–14 (doi:10.1007/BF01961168) [Google Scholar]

- de Ricqlès A. J., Padian K., Horner J. R., Lamm E.-T., Myhrvold N.2003Osteohistology of Confuciusornis sanctus (Theropoda: Aves). J. Vert. Paleontol. 12, 373–386 [Google Scholar]

- Draper N. R., Smith H.1998Applied regression analysis, 3rd edn New York, NY: John Wiley [Google Scholar]

- Evans M. R.2004Limits on the evolution of tail ornaments in birds. Am. Nat. 163, 341–357 (doi:10.1086/381770) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairbairn D. J.1997Allometry for sexual size dimorphism: pattern and process in the coevolution of body size in males and females. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 28, 659–687 (doi:10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.28.1.659) [Google Scholar]

- Guo Z. F., Wang X. L.2002A study on the relationship between volcanic activities and mass mortalities of the Jehol vertebrate fauna from Sihetun, western Liaoning, China. Acta Petrol. Sinica 18, 117–125 [Google Scholar]

- Heinroth O.1922Die Beziehungen zwischen Vogelgewicht, Eigewicht, Gelegegewicht und Brutdauer. J. Ornithol. 10, 172–285 [Google Scholar]

- Horner J. R.2000Dinosaur reproduction and parenting. Annu. Rev. Earth Planet Sci. 28, 19–45 (doi:10.1146/annurev.earth.28.1.19) [Google Scholar]

- Hou L., Martin L. D., Zhou Z., Feduccia A.1996Early adaptive radiation of birds: evidence from fossils from northeastern China. Science 274, 1164–1167 (doi:10.1126/science.274.5290.1164) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou L., Martin L. D., Zhou Z., Feduccia A., Zhang F.1999A diapsid skull in a new species of the primitive bird Confuciusornis. Nature 399, 679–682 (doi:10.1038/21411) [Google Scholar]

- Imbrie J.1956Biometrical methods in the study of invertebrate fossils. Bull. Am. Mus. Nat. Hist. 108, 215–252 [Google Scholar]

- Jenni D. A.1996Family Jacanidae (Jacanas). In Handbook of the birds of the world, vol. 3 (eds del Hoyo J., Elliott A., Sargatal J.), pp. 276–291 Barcelona, Spain: Lynx Edicions [Google Scholar]

- Latimer H. B.1927Postnatal growth of the chicken skeleton. Am. J. Anat. 40, 1–57 (doi:10.1002/aja.1000400102) [Google Scholar]

- Martin L. D., Zhou Z., Hou L., Feduccia A.1998Confuciusornis sanctus compared to Archaeopteryx lithographica. Naturwissenschaften 85, 286–289 (doi:10.1007/s001140050501) [Google Scholar]

- Møller A. P., Nielsen J. T., Erritzøe J.2006Losing the last feather: feather loss as an antipredator adaptation in birds. Behav. Ecol. 17, 1046–1056 (doi:10.1093/beheco/arl044) [Google Scholar]

- O'Connor R. J.1977Differential growth and body composition in altricial passerines. Ibis 119, 147–166 (doi:10.1111/j.1474-919X.1977.tb03533.x) [Google Scholar]

- Padian K., de Ricqlès A. J., Horner J. R.2001Dinosaurian growth rates and bird origins. Nature 412, 405–408 (doi:10.1038/35086500) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters W. S., Baskin T. I.2006Tailor-made composite functions as tools in model choice: the case of sigmoidal vs bi-linear growth profiles. Plant Meth. 2, 11 (doi:10.1186/1746-4811-2-11) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters D. S., Ji Q.1999Mußte Confuciusornis klettern? J. Ornithol. 140, 41–50 (doi:10.1007/BF02462087) [Google Scholar]

- Prange H. D., Anderson J. F., Rahn H.1979Scaling of skeletal mass to body mass in birds and mammals. Am. Nat. 113, 103–122 (doi:10.1086/283367) [Google Scholar]

- Prinzinger R., Dietz V.2002Pre- and postnatal energetics of the North Island brown kiwi (Apteryx mantelli). Comp. Biochem. Physiol. A 131, 725–732 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas A. L. R.1997On the tails of birds. BioScience 47, 215–225 (doi:10.2307/1313075) [Google Scholar]

- Zhang F., Zhou Z., Hou L.2008Birds. In The Jehol fossils (ed. Chang M.), pp. 128–149 London, UK: Academic Press [Google Scholar]