Abstract

Background and purpose:

ATP-sensitive potassium channels (KATP channels) in beta cells are a major target for insulinotropic drugs. Here, we studied the effects of selected stimulatory and inhibitory pharmacological agents in islets lacking KATP channels.

Experimental approach:

We compared insulin secretion (IS) and cytosolic calcium ([Ca2+]c) changes in islets isolated from control mice and mice lacking sulphonylurea receptor1 (SUR1), and thus KATP channels in their beta cells (Sur1KO).

Key results:

While similarly increasing [Ca2+]c and IS in controls, agents binding to site A (tolbutamide) or site B (meglitinide) of SUR1 were ineffective in Sur1KO islets. Of two non-selective blockers of potassium channels, quinine was inactive, whereas tetraethylammonium was more active in Sur1KO compared with control islets. Phentolamine, efaroxan and alinidine, three imidazolines binding to KIR6.2 (pore of KATP channels), stimulated control islets, but only phentolamine retained weaker stimulatory effects on [Ca2+]c and IS in Sur1KO islets. Neither KATP channel opener (diazoxide, pinacidil) inhibited Sur1KO islets. Calcium channel blockers (nimodipine, verapamil) or diphenylhydantoin decreased [Ca2+]c and IS in both types of islets, verapamil and diphenylhydantoin being more efficient in Sur1KO islets. Activation of α2-adrenoceptors or dopamine receptors strongly inhibited IS while partially (clonidine > dopamine) lowering [Ca2+]c (control > Sur1KO islets).

Conclusions and implications:

Those drugs retaining effects on IS in islets lacking KATP channels, also affected [Ca2+]c, indicating actions on other ionic channels. The greater effects of some inhibitors in Sur1KO than in control islets might be relevant to medical treatment of congenital hyperinsulinism caused by inactivating mutations of KATP channels.

Keywords: KATP channels, insulin secretion, isolated islets, sulfonylurea receptor, imidazolines, catecholamines, diphenylhydantoin, calcium channel blockers, diabetes, congenital hyperinsulinism

Introduction

ATP-sensitive potassium channels (KATP channels) are critical for the control of insulin secretion by beta cells. Their role in stimulus-secretion coupling, which was initially established by various experimental approaches, has been strikingly highlighted by recent evidence that mutations in the genes of the channel subunits may result in congenital hyperinsulinism with life-threatening hypoglycaemia or insulin-deficient neonatal diabetes (Dunne et al., 2004; Bryan et al., 2007; Girard et al., 2009). KATP channels are complex octameric assemblies of two proteins. In beta cells, the pore consists of KIR6.2, and the regulatory subunit consists of the sulphonylurea receptor 1 (SUR1/ABCC8), while other isoforms encoded by ABCC9, SUR2A or SUR2B, are present in most other tissues (Miki et al., 1999; Gribble and Reimann, 2003; Bryan et al., 2007). In low glucose concentrations, enough KATP channels are open to hold the beta cell membrane hyperpolarized and prevent Ca2+ influx into the cell. When the glucose concentration increases, the channels close, permitting depolarization to the potential of activation of voltage-gated calcium channels. The influx of Ca2+ then leads to an increase in the cytosolic concentration of ionized Ca2+ ([Ca2+]c) that serves as an essential triggering signal for exocytosis of insulin granules. Full expression of the secretory response also requires generation by glucose of amplifying signals that augment the efficacy of [Ca2+]c on exocytosis (Henquin, 2009).

Many pharmacological agents lower or increase blood glucose levels by stimulating or inhibiting insulin secretion through a direct action on beta cells. It is hardly surprising that most clinically useful drugs aiming at increasing or decreasing insulin secretion exert their effects through an action on KATP channels. However, actions at other sites have not always been ruled out, and alternative targets might prove useful for therapeutic control of beta cell secretory function (Morgan and Chan, 2001; Doyle and Egan, 2003; Gribble and Reimann, 2003; MacDonald and Wheeler, 2003; Henquin, 2004; Farret et al., 2005; Jacobson and Philipson, 2007).

Previous studies, using islets isolated from mice with a genetic deletion of Sur1 (Sur1KO) (Seghers et al., 2000), have shown that beta cells lacking KATP channels are depolarized and display oscillations of [Ca2+]c that explain their high rate of insulin secretion in the presence of low glucose concentrations, which are non-stimulatory for normal beta cells (Düfer et al., 2004; Nenquin et al., 2004; Szollosi et al., 2007). When challenged with high glucose, Sur1KO beta cells do not further depolarize, but the frequency of their membrane potential and [Ca2+]c oscillations increases. At the same time, a major increase in insulin secretion occurs, which is due to both this small elevation of average [Ca2+]c and the amplifying action of glucose (Szollosi et al., 2007). Beta cells lacking KATP channels are thus responsive to glucose and also known to be unresponsive to sulphonylureas and diazoxide (Seghers et al., 2000; Düfer et al., 2004; Nenquin et al., 2004), prototypical inhibitors and activators of KATP channels in normal islets. Sur1KO islets have however not previously been used for a systematic characterization of the effects of insulinotropic drugs. In the present study, therefore, we used Sur1KO islets to gain a better insight into the mode of action of various pharmacological stimulators and inhibitors of insulin secretion. The effect of the different drugs on islet [Ca2+]c was also measured to determine whether the observed changes in secretion result from changes in the triggering Ca2+ signal produced by KATP channel-independent mechanisms or occur independently of [Ca2+]c changes.

Methods

The study was approved by, and the experiments were conducted in accordance with the guidelines of the Animal Research Committee of our institution.

Animals

Sur1KO mice generated (Seghers et al., 2000) and provided by J. Bryan were maintained in our animal facilities. Controls were C57Bl/6 mice originally obtained from Charles River Laboratories, Brussels, Belgium. All experiments were performed with adult female mice of 10–14 months. Sur1KO mice were slightly heavier than controls (30.2 ± 0.5 g, n= 89 versus 26.9 ± 0.7 g, n= 59, P < 0.001), but their morning blood glucose was similar (7.5 ± 0.2 mmol·L−1 in both groups).

Solutions and reagents

The control medium used for islet isolation was a bicarbonate-buffered solution containing (mmol·L−1): NaCl 120, KCl 4.8, CaCl2 2.5, MgCl2 1.2 and NaHCO3 24. It was gassed with O2: CO2 (94%: 6%) to maintain pH 7.4 and was supplemented with 1 mg·mL−1 bovine serum albumin and 10 mmol·L−1 glucose. A similar medium was used for all experiments after adjustment of the glucose concentration and addition of test substances.

Preparation of islets

Islets from Sur1KO and control mice were aseptically isolated by collagenase digestion of the pancreas followed by hand selection. The islets were then cultured for ∼18 h in RPMI1640 medium (Invitrogen, Belgium) kept at 37°C in a 95% air: 5% CO2 atmosphere. The culture medium contained 10 mmol·L−1 glucose, 10% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum, 100 IU·mL−1 penicillin and 100 µg·mL−1 streptomycin (Nenquin et al., 2004).

Measurements of insulin secretion

After overnight culture, the islets were distributed in batches of 15 before being transferred into perifusion chambers (Henquin et al., 2006). The islets were then perifused (flow rate of 1 mL·min−1) at 37°C with a control medium containing 3 or 15 mmol·L−1 glucose, with or without test substance. Effluent fractions were collected at 2 min intervals and saved for insulin assay using rat insulin as a standard (Henquin et al., 2006).

Measurements of islet [Ca2+]c

After overnight culture, islets were loaded with the Ca2+ indicator fura-PE3-AM (2 µmol·L−1, Teflabs, Austin, TX, USA) for 2 h in control medium containing 10 mmol·L−1 glucose. Loaded islets were then placed into the perifusion chamber of a spectrofluorimetric system, equipped with a camera, and with which [Ca2+]c was measured at 37°C (Nenquin et al., 2004).

Data presentation and analysis

All experiments have been performed with islets from three to five different preparations. Typical changes in [Ca2+]c produced by selected drugs are illustrated by representative experiments. Otherwise, results are presented as means ± SE. The statistical significance of differences between means of non-stimulated islets and islets challenged by a drug was assessed by anova followed by Dunnett's test. P < 0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference between means.

Materials

Tolbutamide, quinine hydrochloride, tetraethylammonium chloride (TEA), efaroxan hydrochloride, compound UCL-1684, verapamil hydrochloride, dopamine hydrochloride and hydrochlorothiazide were obtained from Sigma (St. Louis, MO, USA). Alinidine hydrobromide and clonidine hydrochloride were from Boehringer-Ingelheim (Ingelheim, Germany). Phentolamine mesylate was from Novartis-Pharma (Basel, Switzerland). Meglitinide was from Hoechst AG (Frankfurt, Germany), pinacidil from Leo Pharmaceuticals (Ballerup, Denmark), nimodipine from Bayer (Wuppertal, Germany), diphenylhydantoin from Fluka (Buchs, Switzerland), and diazoxide was a gift from Schering-Plough (Rathdrum, Ireland). Tolbutamide, meglitinide, diazoxide, diphenylhydantoin and hydrochlorothiazide were added from 500 to 1500× concentrated stock solutions freshly prepared in 0.1N NaOH, and pH of the perifusion media was adjusted back to 7.4 when required. Stock solutions of UCL-1684 and nimodipine were prepared in dimethyl suphoxide, the maximum amount of which (0.5 µL·mL−1) had no effect alone. The other substances were dissolved in H2O either directly in perifusion media or as a concentrated stock solution. Drug and molecular target nomenclature follows Alexander et al. (2008).

Results and discussion

Experimental design and control values

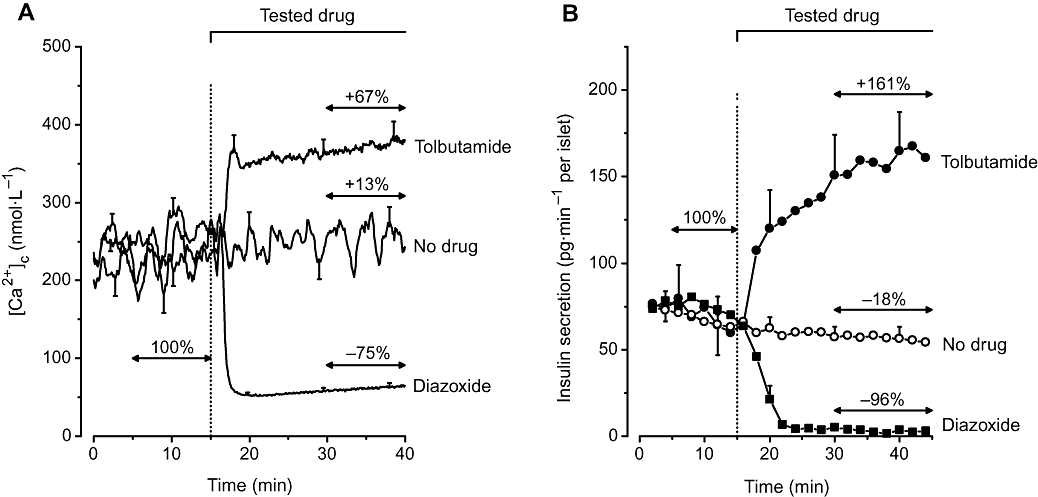

The concentrations of the tested drugs were selected on the basis of their in vitro effects in normal islets reported in previous publications by ourselves and other groups. Figure 1 shows how the effects of the drugs on islet [Ca2+]c (panel A) or insulin secretion (panel B) were measured. The concentration of glucose in the perifusion medium was kept constant (here at 15 mmol·L−1) throughout, and tested drugs (here 100 µmol·L−1 tolbutamide or diazoxide) were applied from 15 to 40 min (A) or 15 to 45 min (B). The steady state effect of each drug was computed during the last 10 (A) or 15 min (B) of application, and expressed as a percentage of the pre-stimulatory reference value (between 5 and 15 min) in each individual experiment. These normalized values were then averaged, and means are presented in Tables. In control islets perifused with 15 mmol·L−1 glucose, tolbutamide increased [Ca2+]c by 67% and insulin secretion by 161% (Figure 1 and Table 1, line 2). These values must be compared to the spontaneous small increase in [Ca2+]c (+13%) and small decrease in insulin secretion (−18%) that occurred when no drug was applied (Figure 1 and Table 1, line 1). Diazoxide lowered [Ca2+]c by 75% and inhibited insulin secretion by 96% in these control islets (Figure 1 and Table 2, line 2).

Figure 1.

Effects of tolbutamide (100 µmol·L−1) and diazoxide (100 µmol·L−1) on [Ca2+]c (panel A) and insulin secretion (panel B) in control islets perifused with a medium containing 15 mmol·L−1 glucose throughout. Values are means ± SE for 16–30 islets from 3–5 preparations in [Ca2+]c experiments, and 5–12 perifusions in insulin secretion experiments. The figure illustrates how the effects of the drugs were computed for presentation in tables. In each individual experiment, [Ca2+]c and the insulin secretion rate were averaged between 5 and 15 min to obtain the reference value (100%). Steady-state effects of drugs were averaged between 30 and 40 min for [Ca2+]c, and 30–45 min for insulin secretion, and expressed relative to the reference value in the same experiment. The mean effect of the drug was then calculated. Panel A thus shows that [Ca2+]c increased by 13% in the absence of drug and by 67% after addition of tolbutamide, and that it decreased by 75% after addition of diazoxide.

Table 1.

Effects of stimulatory agents on [Ca2+]c and insulin secretion in control and Sur1KO islets, in 15 or 3 mmol·L−1 glucose

| Line | Test agent (µmol·L−1) |

Control islets in 15 mmol·L−1 glucose |

Sur1KO islets in 15 mmol·L−1 glucose |

Sur1KO islets in 3 mmol·L−1 glucose |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Δ[Ca2+]c (%) | Δ Insulin (%) | Δ[Ca2+]c (%) | Δ Insulin (%) | Δ[Ca2+]c (%) | Δ Insulin (%) | ||

| 1 | None | +13 ± 2 | −18 ± 3 | +10 ± 1 | −2 ± 3 | +10 ± 3 | −20 ± 3 |

| 2 | Tolbutamide (100) | +67 ± 7** | +161 ± 41** | +14 ± 2 | −1 ± 5 | +3 ± 3 | −19 ± 7 |

| 3 | Meglitinide (10) | +61 ± 5** | +148 ± 35** | +14 ± 2 | −3 ± 5 | +16 ± 2 | −27 ± 3 |

| 4 | Quinine (50) | – | +175 ± 31** | – | +13 ± 4 | – | – |

| 5 | Tetraethylammonium (104) | −9 ± 3** | +24 ± 5 | −2 ± 2** | +82 ± 12** | −1 ± 2 | +20 ± 1** |

| 6 | UCL-1684 (0.5) | +20 ± 4 | −6 ± 3 | +10 ± 2 | +2 ± 5 | – | – |

| 7 | Phentolamine (100) | +70 ± 5** | +181 ± 42** | +29 ± 4** | +39 ± 6** | +34 ± 6** | +46 ± 9** |

| 8 | Efaroxan (100) | +60 ± 3** | +187 ± 30** | +18 ± 3 | +17 ± 13 | – | – |

| 9 | Alinidine (100) | +33 ± 5** | +57 ± 7* | +12 ± 2 | +10 ± 14 | +17 ± 2 | −9 ± 19 |

Values are means ± SEM for 16–30 islets from 3–5 preparations in [Ca2+]c experiments and for 4–12 separate perifusions in insulin secretion experiments. Absolute reference values (100%) for [Ca2+]c and insulin secretion were similar between all test groups of control and Sur1KO islets.

P < 0.05,

P < 0.01 or less versus 15 or 3 mmol·L−1 glucose alone (first line in the same column) by anova.

Table 2.

Effects of inhibitory agents on [Ca2+]c and insulin secretion in control and Sur1KO islets, in 15 or 3 mmol·L−1 glucose

| Line | Test agent (µmol·L−1) |

Control islets in 15 mmol·L−1 glucose |

Sur1KO islets in 15 mmol·L−1 glucose |

Sur1KO islets in 3 mmol·L−1 glucose |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Δ[Ca2+]c (%) | Δ Insulin (%) | Δ[Ca2+]c (%) | Δ Insulin (%) | Δ[Ca2+]c (%) | Δ Insulin (%) | ||

| 1 | None | +13 ± 2 | −18 ± 3 | +10 ± 1 | −2 ± 3 | +10 ± 3 | −20 ± 3 |

| 2 | Diazoxide (100) | −75 ± 2** | −96 ± 1** | +4 ± 2 | +2 ± 5 | +14 ± 5 | −20 ± 5 |

| 3 | Pinacidil (250) | −37 ± 3** | −69 ± 3** | +2 ± 2 | −3 ± 7 | +2 ± 5 | −11 ± 6 |

| 4 | Nimodipine (0.1) | −67 ± 4** | −76 ± 3** | −63 ± 2** | −85 ± 6** | −64 ± 4** | −91 ± 3** |

| 5 | Verapamil (20) | −38 ± 2** | −21 ± 8 | −52 ± 2** | −79 ± 4** | −58 ± 2** | −78 ± 16** |

| 6 | Verapamil (100) | −64 ± 1** | −65 ± 5** | −61 ± 3** | −82 ± 4** | – | – |

| 7 | Diphenylhydantoin (20) | −28 ± 2** | −64 ± 3** | −51 ± 2** | −82 ± 1** | −55 ± 3** | −67 ± 5** |

| 8 | Hydrochlorothiazide (1) | +20 ± 3 | −14 ± 3 | +13 ± 2 | +1 ± 6 | +14 ± 4 | −26 ± 5 |

| 9 | Clonidine (1) | −59 ± 4** | −96 ± 2** | −35 ± 2** | −87 ± 3** | −43 ± 2** | −92 ± 3** |

| 10 | Dopamine (10) | −51 ± 3** | −88 ± 4** | −27 ± 3** | −68 ± 3** | −23 ± 2** | −80 ± 7** |

Values are means ± SEM for 16–30 islets from 3–5 preparations in [Ca2+]c experiments and for 4–12 separate perifusions in insulin secretion experiments. Absolute reference values (100%) for [Ca2+]c and insulin secretion were similar between all test groups of control and Sur1KO islets.

*P < 0.05,

P < 0.01 or less versus 15 or 3 mmol·L−1 glucose alone (first line in the same column) by anova.

In control islets perifused with 15 mmol·L−1 glucose alone, reference values (100%) were 227 ± 10 nmol·L−1[Ca2+]c (n= 30) and 67 ± 7 pg insulin per islet·min−1 (n= 12). In untreated Sur1KO islets, [Ca2+]c averaged 194 ± 6 nmol·L−1 (n= 29) and 157 ± 7 nmol·L−1 (n= 23) in 15 and 3 mmol·L−1 glucose, respectively, while insulin secretion rates averaged 149 ± 11 pg per islet·min−1 (n= 10) and 52 ± 9 pg per islet·min−1 (n= 9). High glucose thus slightly increased [Ca2+]c (P < 0.01) and markedly augmented insulin secretion (P < 0.001) in these islets lacking KATP channels (Nenquin et al., 2004; Szollosi et al., 2007).

Effects of putative stimulators of insulin secretion

Blockers of KATP channels

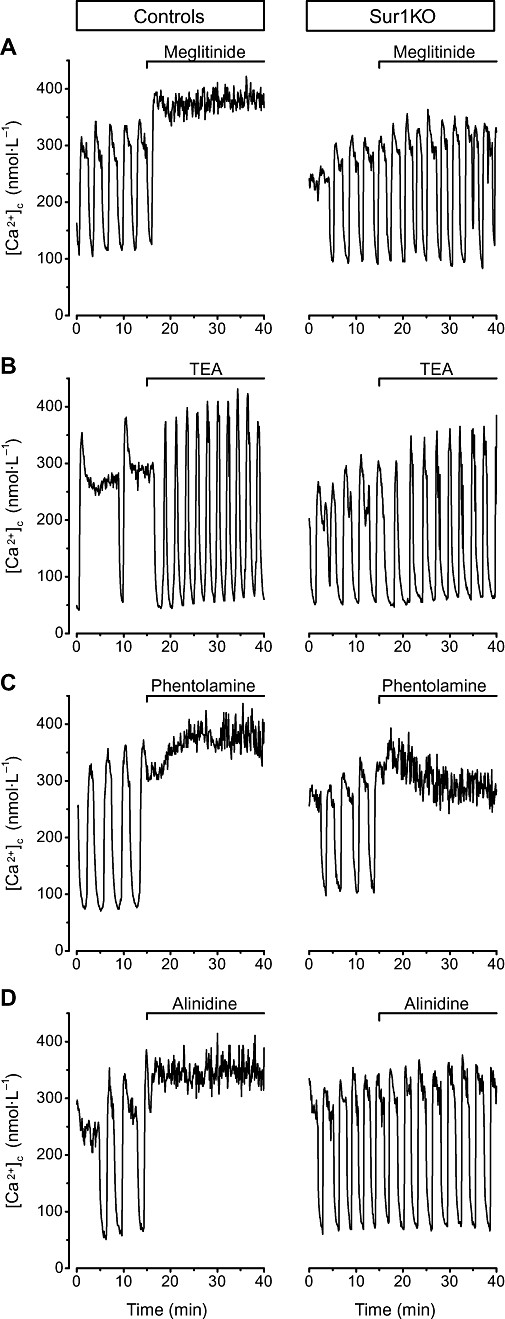

Tolbutamide closes KATP channels by interacting with binding site A that is present in SUR1 only (Gribble and Reimann, 2003; Bryan et al., 2005). As previously reported (Seghers et al., 2000; Düfer et al., 2004; Nenquin et al., 2004), Sur1KO islets did not display any change in [Ca2+]c or insulin secretion when challenged by tolbutamide (Table 1, line 2). Meglitinide, the non-sulphonylurea moiety of glibenclamide (also known as HB699), is the mother compound of the glinide family. It mimics the effects of tolbutamide on KATP channels (Garrino et al., 1985; Panten et al., 1989), but does so by interacting with binding site B, that is present in both SUR1 and SUR2 (Bryan et al., 2005). In control islets, meglitinide suppressed [Ca2+]c oscillations induced by glucose and caused a sustained elevation (Figure 2A), which resulted in marked increases in average [Ca2+]c and insulin secretion rate (Table 1, line 3). In Sur1KO islets, [Ca2+]c was also oscillatory in the presence of 15 mmol·L−1 glucose alone (Nenquin et al., 2004; Szollosi et al., 2007), but it was unaffected by meglitinide (Figure 2A), so that average [Ca2+]c and insulin secretion were not different in the presence or absence of the drug (Table 1, line 3). The lack of effects of tolbutamide and meglitinide in Sur1KO islets was confirmed in the presence of low glucose (Table 1, lines 2 and 3, right-hand columns). Glibenclamide that interacts with both binding sites A and B of SUR1 (Bryan et al., 2005) is also without effect in Sur1KO islets (Henquin, 2004). Altogether, these results show that neither sulphonylureas nor glinides have effects on insulin secretion in the absence of KATP channels.

Figure 2.

Effects of selected stimulators of insulin secretion on [Ca2+]c in control and Sur1KO islets perifused with 15 mmol·L−1 glucose. Meglitinide (100 µmol·L−1), tetraethylammonium (TEA, 10 mmol·L−1), phentolamine (100 µmol·L−1) or alinidine (100 µmol·L−1) was added as indicated at the top of each panel. Traces illustrate the changes occurring in representative islets. Quantification of the changes is presented in Table 1.

Quinine has long been known to augment insulin secretion by decreasing the potassium permeability of the beta cell membrane (Henquin, 1982). This effect results from closure of KATP channels (Bokvist et al., 1990) via a direct interaction with KIR6.2 (Gribble et al., 2000) and inhibition of several other types of potassium channels (Bokvist et al., 1990). The fluorescence of quinine precluded reliable measurements of [Ca2+]c, but the drug potently increased insulin secretion in control islets and was without effect in Sur1KO islets (Table 1, line 4). This indicates that blockage of KATP channels accounts for the effects of the drug on insulin secretion in control islets, and that beta cells lacking KATP channels are unlikely to express other channels incorporating KIR6.2. In this context, it is relevant that antibacterial fluoroquinolines, which also increase insulin secretion by blocking KATP channels at the KIR6.2 level (Zünkler and Wos, 2003; Saraya et al., 2004), have recently been reported to be inefficient in Sur1KO islets (Ghaly et al., 2009).

Blockers of other potassium channels

In addition to KATP channels, tetraethylammonium inhibits voltage-gated and Ca2+-activated potassium channels (Bokvist et al., 1990) presumably through a direct action on the pore of the channels. In control islets, tetraethylammonium produces typical shortening, acceleration and increase in amplitude of the oscillations of membrane potential induced by glucose (Henquin, 1990). The oscillations of [Ca2+]c changed in a similar way (Roe et al., 1996) (Figure 2B), which resulted in a minor decrease in average [Ca2+]c (Table 1, line 5) with, however, a tendency to increase insulin secretion (the difference with untreated islets did not reach statistical significance by anova, but it was P < 0.0001 by Student's t-test). Qualitatively similar changes occurred in Sur1KO islets (Figure 2B), but the increase in insulin secretion was greater (Table 1, line 5). This trend and this increase in insulin secretion in face of slightly lower average [Ca2+]c are paradoxical and suggest that the profile and amplitude of [Ca2+]c oscillations may be relevant for stimulus-secretion coupling. The effectiveness of tetraethylammonium in Sur1KO islets suggests that potassium channels other than KATP channels are potential targets of pharmacological secretagogues, as previously proposed by other approaches (MacDonald and Wheeler, 2003; Jacobson and Philipson, 2007), if sufficient tissue selectivity can be achieved (Henquin, 2004).

A hyperpolarizing current (IKslow) produced by small conductance, Ca2+-activated and sulphonylurea-insensitive potassium channels could be implicated in the termination of membrane potential and [Ca2+]c oscillations in glucose-stimulated normal beta cells (Göpel et al., 1999; Zhang et al., 2005) and in Sur1KO beta cells (Haspel et al., 2005). However, compound UCL-1684, a selective blocker of these channels (Zhang et al., 2005), had no effect on [Ca2+]c or insulin secretion in either control or Sur1KO islets (Table 1, line 6), which questions the role of these SKCa channels in beta cell function.

Imidazolines

Stimulation of insulin secretion by various compounds belonging to the family of imidazolines has been attributed to blockage of KATP channels through a direct interaction with KIR6.2 (Jonas et al., 1992; Proks and Ashcroft, 1997), but mechanisms independent of the generation of the triggering Ca2+ signal have also been proposed (Morgan and Chan, 2001; Efendic et al., 2002). In control islets, phentolamine (Figure 2C), efaroxan (not illustrated) and alinidine (Figure 2D) caused a sustained increase in [Ca2+]c and insulin secretion (Table 1, lines 7, 8, 9). In Sur1KO islets perifused with 15 mmol·L−1 glucose, efaroxan and alinidine were ineffective, but phentolamine still increased both [Ca2+]c (Figure 2C) and insulin secretion (Table 2, line 7), albeit to a much smaller extent than in controls. Similar results were obtained in Sur1KO islets perifused with 3 mmol·L−1 glucose. The effects of phentolamine on [Ca2+]c in beta cells lacking KATP channels can be attributed to blockage of other types of potassium channels (Jonas et al., 1992). It thus appears that classical imidazolines augment insulin secretion via an increase in [Ca2+]c, which is mainly mediated by an action on KATP channels. Newer imidazolines, such as compound RX871024, may have other, intracellular sites of action, but their effects are notably smaller in Sur1KO than control islets (Efanov et al., 2001).

Effects of putative inhibitors of insulin secretion

Activators of KATP channels

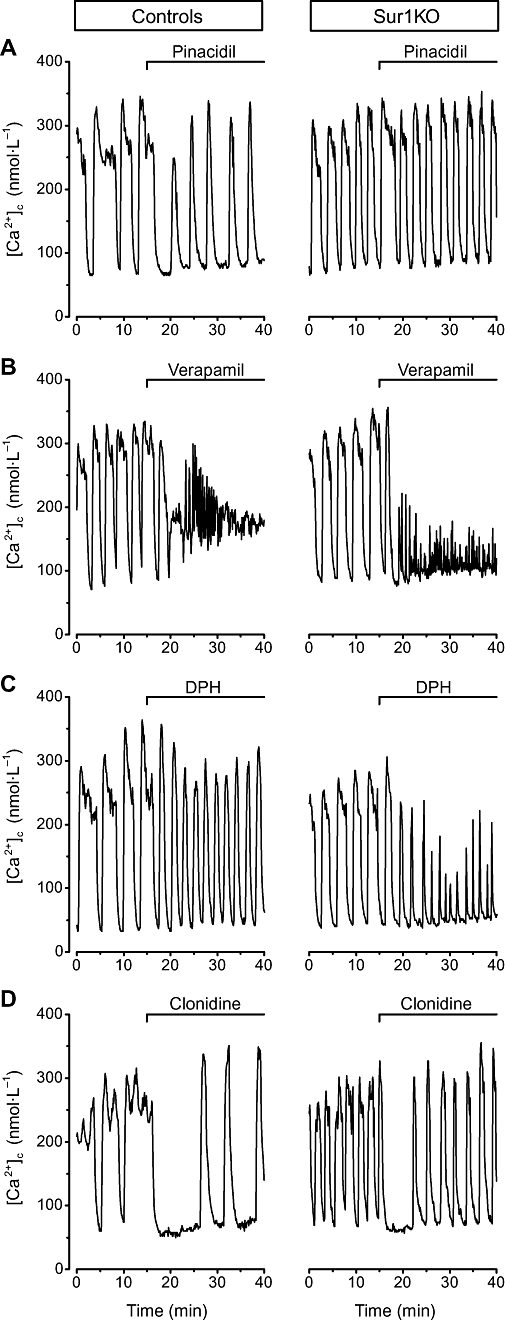

Diazoxide opens KATP channels containing either SUR1 or SUR2 (Gribble and Reimann, 2003; Bryan et al., 2005; Moreau et al., 2005). As shown in Figure 1, diazoxide markedly decreased [Ca2+]c and abolished insulin secretion in control islets, but it was ineffective in Sur1KO islets (Table 2, line 2), as previously reported (Nenquin et al., 2004). Pinacidil also inhibits insulin secretion by opening beta cell KATP channels (Garrino et al., 1989; Lebrun et al., 1989), but its affinity is much greater for SUR2 than SUR1 (Gribble and Reimann, 2003; Bryan et al., 2005; Moreau et al., 2005). Although used at a higher concentration than diazoxide, pinacidil was less potent on [Ca2+]c and insulin secretion in control islets, and, like diazoxide, totally ineffective in Sur1KO islets (Figure 3A) (Table 2, line 3). While there is no dispute that SUR1 is the major sulphonylurea receptor in beta cells, SUR2A is moderately expressed in mouse islets (Miki et al., 1999), and the ubiquitous SUR2B is present in the pancreas (Isomoto et al., 1996). It is, however, uncertain whether these two isoforms are present in beta cells or in endocrine non-beta cells or non-endocrine (vascular) cells of the islets. Taken together, our experiments using meglitinide, diazoxide and pinacidil show that no alternative form of KATP channels is expressed in these Sur1KO islets, and thus presumably in normal beta cells. The results also reinforce the common, though not unanimous (Grimmsmann and Rustenbeck, 1998; Geng et al., 2007), view that these drugs and sulphonylureas do not influence insulin secretion by interacting with intracellular targets.

Figure 3.

Effects of selected inhibitors of insulin secretion on [Ca2+]c in control and Sur1KO islets perifused with 15 mmol·L−1 glucose. Pinacidil (250 µmol·L−1), verapamil (20 µmol·L−1), diphenylhydantoin (DPH, 20 µmol·L−1) or clonidine (1 µmol·L−1) was added as indicated at the top of each panel. Traces illustrate the changes occurring in representative islets. Quantification of the changes is presented in Table 2.

Blockers of voltage-gated calcium channels

Nimodipine potently decreased [Ca2+]c and inhibited insulin secretion in control and Sur1KO islets perifused with 15 mmol·L−1 glucose (Table 2, line 4). Qualitatively similar effects were produced by verapamil (Figure 3B) (Table 2, lines 5, 6). Both agents were also efficient in Sur1KO islets perifused with only 3 mmol·L−1 glucose. This shows that continuous influx of Ca2+ through voltage-gated calcium channels of the L-type is required for the high rate of insulin secretion in Sur1KO islets at both low and high glucose. Unexpectedly, the inhibition of insulin secretion by verapamil was greater in Sur1KO than control islets, particularly at 20 µmol·L−1. We tentatively attribute this difference to the fact that, besides their inhibitory action via blockage of calcium channels, phenylalkylamines such as verapamil also have a positive effect via blockage of KATP channels in control islets (Lebrun et al., 1997). In Sur1KO islets, only the inhibitory action can manifest itself. In contrast, dihydropyridines such as nimodipine, do not affect KATP channels (Lebrun et al., 1997), which explains their similar action in both types of islets. Calcium channel blockers are sometimes used in the medical treatment of congenital hyperinsulinism (Aynsley-Green et al., 2000). It might be worth testing whether phenylalkylamines have advantages over dihydropyridines in cases where a focal lesion lacking functional KATP channels coexists with normal islets (Sempoux et al., 2003). Their effect might be greater in the lesion than in normal beta cells.

The antiepileptic agent diphenylhydantoin is known to inhibit glucose-induced insulin secretion (Levin et al., 1972). This effect has been attributed to a decrease in Ca2+ influx into beta cells (Herchuelz et al., 1981), but this view was challenged recently and the effect of diphenylhydantoin attributed to an alkalinization of beta cell cytosol with secondary decrease in Ca2+ action on exocytosis (Nabe et al., 2006). As shown in Figure 3C, diphenylhydantoin decreased amplitude and duration of [Ca2+]c oscillations, which resulted in a decrease in average [Ca2+]c and insulin secretion in control and Sur1KO islets perifused with 15 mmol·L−1 glucose (Table 2, line 7). Interestingly, the effects of diphenylhydantoin were greater in Sur1KO than control islets. Because the inhibition of insulin secretion was also observed in low glucose, we suggest that diphenylhydantoin might be tested as an adjunct therapy in diazoxide-resistant congenital hyperinsulinism due to inactivating mutations of KATP channel subunits. Diphenylhydantoin has occasionally been found useful in the medical treatment of insulinomas (Imanaka et al., 1986). In the same perspective, we tested the effects of hydrochlorothiazide, a diuretic drug that is often associated with diazoxide (Aynsley-Green et al., 2000), and has been reported to inhibit insulin secretion by islets from ob/ob mice (Sandström, 1993). The drug was without effect on [Ca2+]c and insulin secretion in both normal and Sur1KO islets (Table 2, line 8).

Catecholamines

Activation of α2-adrenoceptors by adrenaline or selective agonists such as clonidine is known to inhibit insulin secretion via multiple mechanisms, including a hyperpolarization of the beta cell membrane, which has been attributed to opening of potassium channels (Drews et al., 1990; Sieg et al., 2004). In glucose-stimulated control islets, clonidine rapidly lowered [Ca2+]c to basal values, but oscillations, sometimes of large amplitude, resumed in almost 50% (10/22) of the islets (Figure 3D). In Sur1KO islets, the initial inhibition was similar, but resumption of [Ca2+]c oscillations was more frequent (19/24 islets), so that the steady-state decrease in [Ca2+]c was smaller than in controls (Table 2, line 9). This, however, did not influence the degree of inhibition of insulin secretion that was virtually complete in both types of islets. These observations therefore support previous evidence that adrenoceptor-mediated inhibition of insulin secretion is mainly achieved by interference with distal steps of stimulus-secretion coupling (Ullrich and Wollheim, 1985; Jones et al., 1987). The rapid decrease in [Ca2+]c produced by clonidine in Sur1KO islets is also in keeping with the report that adrenaline rapidly hyperpolarized Sur1KO beta cells (Sieg et al., 2004). Although this and the present studies support the conclusion that the hyperpolarization involves channels other than KATP channels, some contribution of the latter cannot be completely ruled out in view of the greater inhibition of [Ca2+]c in control than Sur1KO islets.

Activation of dopamine D2 receptors by dopamine has been reported to lower [Ca2+]c in INS1 cells and to inhibit insulin secretion in the cell line and in rodent islets (Rubíet al., 2005). We found the effects of dopamine on [Ca2+]c to be qualitatively similar to those of clonidine, and again quantitatively larger in control than Sur1KO islets (Table 2, lines 9, 10). Insulin secretion was more inhibited than expected for the decrease in [Ca2+]c, which suggests that, like α2-adrenoceptors, dopamine D2 receptors interfere with stimulus-secretion coupling at steps distal to the [Ca2+]c increase.

Both clonidine and dopamine also very effectively inhibited insulin secretion by Sur1KO islets in low glucose (Table 2, lines 9, 10). Thus, targeting these receptors might theoretically be interesting to counter congenital hyperinsulinism due to inactivation of KATP channels, but the usefulness and tolerance of such treatments remain to be evaluated.

Acknowledgments

We thank F. Knockaert for technical assistance and J. Bryan for providing the Sur1KO mice. This work was supported by the Fonds National de la Recherche Scientifique (3.4530.08), the Politique Scientifique fédérale belge (PAI 6/40) and the Direction de la Recherche Scientifique de la Communauté Française de Belgique (ARC 05/10-328).

Glossary

Abbreviations:

- [Ca2+]c

cytosolic free Ca2+ concentration

- KATP channel

ATP-sensitive potassium channel

- SUR1

sulphonylurea receptor 1

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest associated with this manuscript.

References

- Alexander SP, Mathie A, Peters JA. Guide to Receptors and Channels (GRAC), 3rd edn. Br J Pharmacol. 2008;153(Suppl 2):S1–S209. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0707746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aynsley-Green A, Hussain K, Hall J, Saudubray JM, Nihoul-Fékété C, De Lonlay-Debeney P, et al. Practical management of hyperinsulinism in infancy. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2000;82:F98–F107. doi: 10.1136/fn.82.2.F98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bokvist K, Rorsman P, Smith PA. Block of ATP-regulated and Ca2+-activated K+ channels in mouse pancreatic beta-cells by external tetraethylammonium and quinine. J Physiol. 1990;423:327–342. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1990.sp018025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryan J, Crane A, Vila-Carriles WH, Babenko AP, Aguilar-Bryan L. Insulin secretagogues, sulfonylurea receptors and K(ATP) channels. Curr Pharm Des. 2005;11:2699–2716. doi: 10.2174/1381612054546879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryan J, Muñoz A, Zhang X, Düfer M, Drews G, Krippeit-Drews P, et al. ABCC8 and ABCC9: ABC transporters that regulate K+ channels. Pflugers Arch. 2007;453:703–718. doi: 10.1007/s00424-006-0116-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doyle ME, Egan JM. Pharmacological agents that directly modulate insulin secretion. Pharmacol Rev. 2003;55:105–131. doi: 10.1124/pr.55.1.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drews G, Debuyser A, Nenquin M, Henquin JC. Galanin and epinephrine act on distinct receptors to inhibit insulin release by the same mechanisms including an increase in K+ permeability of the β-cell membrane. Endocrinology. 1990;126:1646–1653. doi: 10.1210/endo-126-3-1646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Düfer M, Haspel D, Krippeit-Drews P, Aguilar-Bryan L, Bryan J, Drews G. Oscillations of membrane potential and cytosolic Ca2+ concentration in SUR1(-/-) beta cells. Diabetologia. 2004;47:488–498. doi: 10.1007/s00125-004-1348-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunne MJ, Cosgrove KE, Shepherd RM, Aynsley-Green A, Lindley KJ. Hyperinsulinism in infancy: from basic science to clinical disease. Physiol Rev. 2004;84:239–275. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00022.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Efanov AM, Hoy M, Branstrom R, Zaitsev SV, Magnuson MA, Efendic S, et al. The imidazoline RX871024 stimulates insulin secretion in pancreatic beta-cells from mice deficient in KATP channel function. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2001;284:918–922. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.5068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Efendic S, Efanov AM, Berggren PO, Zaitsev SV. Two generations of insulinotropic imidazoline compounds. Diabetes. 2002;51(Suppl 3):S448–S454. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.51.2007.s448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farret A, Lugo-Garcia L, Galtier F, Gross R, Petit P. Pharmacological interventions that directly stimulate or modulate insulin secretion from pancreatic beta-cell: implications for the treatment of type 2 diabetes. Fundam Clin Pharmacol. 2005;19:647–656. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-8206.2005.00375.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrino MG, Plant TD, Henquin JC. Effects of putative activators of K+ channels in mouse pancreatic beta-cells. Br J Pharmacol. 1989;98:957–965. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1989.tb14626.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrino MG, Schmeer W, Nenquin M, Meissner HP, Henquin JC. Mechanism of the stimulation of insulin release in vitro by HB 699, a benzoic acid derivative similar to the non-sulphonylurea moiety of glibenclamide. Diabetologia. 1985;28:697–703. doi: 10.1007/BF00291979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geng X, Li L, Bottino R, Balamurugan AN, Bertera S, Densmore E, et al. Antidiabetic sulfonylurea stimulates insulin secretion independently of plasma membrane KATP channels. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2007;293:E293–E301. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00016.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghaly H, Kriete C, Sahin S, Pflöger A, Holzgrabe U, Zünkler BJ, et al. The insulinotropic effect of fluoroquinolones. Biochem Pharmacol. 2009;77:1040–1052. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2008.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Girard CA, Wunderlich FT, Shimomura K, Collins S, Kaizik S, Proks P, et al. Expression of an activating mutation in the gene encoding the KATP channel subunit Kir6.2 in mouse pancreatic beta cells recapitulates neonatal diabetes. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:80–90. doi: 10.1172/JCI35772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Göpel SO, Kanno T, Barg S, Eliasson L, Galvanovskis J, Renström E, et al. Activation of Ca2+-dependent K+ channels contributes to rhythmic firing of action potentials in mouse pancreatic beta cells. J Gen Physiol. 1999;114:759–770. doi: 10.1085/jgp.114.6.759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gribble FM, Davis TME, Higham CE, Clark A, Ashcroft FM. The antimalarial agent mefloquine inhibits ATP-sensitive K-channels. Br J Pharmacol. 2000;131:756–760. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0703638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gribble FM, Reimann F. Sulphonylurea action revisited: the post. cloning era. Diabetologia. 2003;46:875–891. doi: 10.1007/s00125-003-1143-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimmsmann T, Rustenbeck I. Direct effects of diazoxide on mitochondria in pancreatic B-cells and on isolated liver mitochondria. Br J Pharmacol. 1998;123:781–788. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0701663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haspel D, Krippeit-Drews P, Aguilar-Bryan L, Bryan J, Drews G, Dufer M. Crosstalk between membrane potential and cytosolic Ca2+ concentration in beta cells from Sur1−/− mice. Diabetologia. 2005;48:913–921. doi: 10.1007/s00125-005-1720-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henquin JC. Quinine and the stimulus-secretion coupling in pancreatic beta-cells: glucose-like effects on potassium permeability and insulin release. Endocrinology. 1982;110:1325–1332. doi: 10.1210/endo-110-4-1325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henquin JC. Role of voltage- and Ca2+-dependent K+ channels in the control of glucose-induced electrical activity in pancreatic B-cells. Pflügers Archiv. 1990;416:568–572. doi: 10.1007/BF00382691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henquin JC. Pathways in beta-cell stimulus-secretion coupling as targets for therapeutic insulin secretagogues. Diabetes. 2004;53(Suppl 3):S48–S58. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.suppl_3.s48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henquin JC. Regulation of insulin secretion: a matter of phase control and amplitude modulation. Diabetologia. 2009;52:739–751. doi: 10.1007/s00125-009-1314-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henquin JC, Nenquin M, Stiernet P, Ahren B. In vivo and in vitro glucose-induced biphasic insulin secretion in the mouse: pattern and role of cytoplasmic Ca2+ and amplification signals in beta-cells. Diabetes. 2006;55:441–451. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.55.02.06.db05-1051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herchuelz A, Lebrun P, Sener A, Malaisse WJ. Ionic mechanism of diphenylhydantoin action on glucose-induced insulin release. Eur J Pharmacol. 1981;73:189–197. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(81)90090-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imanaka S, Matsuda S, Ito K, Matsuoka T, Okada Y. Medical treatment for inoperable insulinoma: clinical usefulness of diphenylhydantoin and diltiazem. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 1986;16:65–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isomoto S, Kondo C, Yamada M, Matsumoto S, Higashiguchi O, Horio Y, et al. A novel sulfonylurea receptor forms with BIR (Kir6.2) a smooth muscle type ATP-sensitive K+ channel. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:24321–24324. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.40.24321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson DA, Philipson LH. Action potentials and insulin secretion: new insights into the role of Kv channels. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2007;9(Suppl 2):89–98. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1326.2007.00784.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonas JC, Plant TD, Henquin JC. Imidazoline antagonists of alpha 2-adrenoceptors increase insulin release in vitro by inhibiting ATP-sensitive K+ channels in pancreatic beta-cells. Br J Pharmacol. 1992;107:8–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1992.tb14456.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones PM, Fyles JM, Persaud SJ, Howell SL. Catecholamine inhibition of Ca2+-induced insulin secretion from electrically permeabilised islets of Langerhans. FEBS Lett. 1987;219:139–144. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(87)81206-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lebrun P, Devreux V, Hermann M, Herchuelz A. Similarities between the effects of pinacidil and diazoxide on ionic and secretory events in rat pancreatic islets. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1989;250:1011–1018. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lebrun P, Antoine MH, Ouedraogo R, Pirotte B, Herchuelz A, Cosgrove KE, et al. Verapamil, a phenylalkylamine Ca2+ channel blocker, inhibits ATP-sensitive K+ channels in insulin-secreting cells from rats. Diabetologia. 1997;40:1403–1410. doi: 10.1007/s001250050842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levin SR, Grodsky GM, Hagura R, Smith D. Comparison of the inhibitory effects of diphenylhydantoin and diazoxide upon insulin secretion from the isolated perfused pancreas. Diabetes. 1972;21:856–862. doi: 10.2337/diab.21.8.856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald PE, Wheeler MB. Voltage-dependent K+ channels in pancreatic beta cells: role, regulation and potential as therapeutic targets. Diabetologia. 2003;46:1046–1062. doi: 10.1007/s00125-003-1159-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miki T, Nagashima K, Seino S. The structure and function of the ATP-sensitive K+ channel in insulin-secreting pancreatic beta-cells. J Mol Endocrinol. 1999;22:113–123. doi: 10.1677/jme.0.0220113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreau C, Prost AL, Derand R, Vivaudou M. SUR, ABC proteins targeted by KATP channel openers. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2005;38:951–963. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2004.11.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan NG, Chan SL. Imidazoline binding sites in the endocrine pancreas: can they fulfill their potential as targets for the development of new insulin secretagogues? Curr Pharm Des. 2001;7:1413–1431. doi: 10.2174/1381612013397366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nabe K, Fujimoto S, Shimodahira M, Kominato R, Nishi Y, Funakoshi S, et al. Diphenylhydantoin suppresses glucose-induced insulin release by decreasing cytoplasmic H+ concentration in pancreatic islets. Endocrinology. 2006;147:2717–2727. doi: 10.1210/en.2005-1260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nenquin M, Szollosi A, Aguilar-Bryan L, Bryan J, Henquin JC. Both triggering and amplifying pathways contribute to fuel-induced insulin secretion in the absence of sulfonylurea receptor-1 in pancreatic beta-cells. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:32316–32324. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M402076200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panten U, Burgfeld J, Goerke F, Rennicke M, Schwanstecher M, Wallasch A, et al. Control of insulin secretion by sulfonylureas, meglitinide and diazoxide in relation to their binding to the sulfonylurea receptor in pancreatic islets. Biochem Pharmacol. 1989;38:1217–1229. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(89)90327-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proks P, Ashcroft FM. Phentolamine block of KATP channels is mediated by Kir6.2. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:11716–11720. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.21.11716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roe MW, Worley JF, Mittal AA, Kuznetsov A, DasGupta S, Mertz RJ, et al. Expression and function of pancreatic beta-cell delayed rectifier K+ channels. Role in stimulus-secretion coupling. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:32241–32246. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.50.32241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubí B, Ljubicic S, Pournourmohammadi S, Carobbio S, Armanet M, Bartley C, et al. Dopamine D2-like receptors are expressed in pancreatic beta cells and mediate inhibition of insulin secretion. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:36824–36832. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M505560200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandström PE. Inhibition by hydrochlorothiazide of insulin release and calcium influx in mouse pancreatic β-cells. Br J Pharmacol. 1993;110:1359–1362. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1993.tb13969.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saraya A, Yokokura M, Gonoi T, Seino S. Effects of fluoroquinolones on insulin secretion and beta-cell ATP-sensitive K+ channels. Eur J Pharmacol. 2004;497:111–117. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2004.06.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seghers V, Nakazaki M, DeMayo F, Aguilar-Bryan L, Bryan J. Sur1 knockout mice: a model for KATP channel-independent regulation of insulin secretion. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:9270–9277. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.13.9270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sempoux C, Guiot Y, Dahan K, Moulin P, Stevens M, Lambot V, et al. The focal form of persistent hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemia of infancy: morphological and molecular studies show structural and functional differences with insulinoma. Diabetes. 2003;52:784–794. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.52.3.784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sieg A, Su J, Munoz A, Buchenau M, Nakazaki M, Aguilar-Bryan L, et al. Epinephrine-induced hyperpolarization of islet cells without KATP channels. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2004;286:E463–E471. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00365.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szollosi A, Nenquin M, Henquin JC. Overnight culture unmasks glucose-induced insulin secretion in mouse islets lacking ATP-sensitive K+ channels by improving the triggering Ca2+ signal. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:14768–14776. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M701382200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ullrich S, Wollheim CB. Expression of both alpha 1- and alpha 2-adrenoceptors in an insulin-secreting cell line. Parallel studies of cytosolic free Ca2+ and insulin release. Mol Pharmacol. 1985;28:100–106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang M, Houamed K, Kupershmidt S, Roden D, Satin LS. Pharmacological properties and functional role of Kslow current in mouse pancreatic beta-cells: SK channels contribute to Kslow tail current and modulate insulin secretion. J Gen Physiol. 2005;126:353–363. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200509312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zünkler BJ, Wos M. Effects of lomefloxacin and norfloxacin on pancreatic beta- cell ATP-sensitive K+ channels. Life Sci. 2003;73:429–435. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(03)00296-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]