Abstract

Complications of pacemaker implantation include myocardial perforation, venous thrombosis, vegetations of the tricuspid valve or pacing lead, and tricuspid regurgitation. We report a patient presenting with a case of delayed ventricular lead perforation through the right ventricle. The lead was uneventfully extracted under transesophageal echocardiographic observation in the operating room with cardiac surgery backup.

Keywords: pacemaker, lead perforation, complication

Introduction

Implantation of permanent pacemakers (PM) represents an effective treatment option for several cardiac arrhythmias. The incidence of acute complications from device implantation, such as pneumothorax, cardiac effusion, and lead perforation ranges from 1% to 7%.1,2 Delayed complications mostly include infection, subclavian vein thrombosis, failure of sensing and pacing, and erosion of the pulse generator or lead connections.3 As a rare late complication, delayed lead perforation has also been reported in several case reports.4–7 This complication is defined as delayed perforation beyond one month of device implantation. We report a case of uneventful transvenous extraction of a passive fixation lead with perforation of the right ventricle three months after implantation of a permanent pacemaker.

Case report

A 78-year-old female presented to our department with asymptomatic right ventricular lead dislocation. Three months earlier she underwent implantation of a permanent dual-chamber pacemaker (St. Jude Medical Verity ADx XL DR 5356) with the following fixation leads (atrial: Medtronic 5076-58 cm active fixation lead; ventricular: Medtronic 4074-58 cm passive fixation lead) due to sick sinus syndrome and intermittent atrioventricular block II. The chest X-ray prior to discharge showed correct position of the atrial and ventricular leads (Figure 1). Routine testing one month after implantation was uneventful. Testing after three months showed loss of ventricular sensing and pacing. A chest X-ray was performed but was not highly suspicious for lead dislocation (Figures 2a, b). However, chest computed tomography (CT) with 3-D reconstruction of the lateral wall of the right ventricle confirmed perforation of the passive-fixation right ventricular lead through the right ventricle and pericardium into the left lateral chest from the right ventricular apical site (Figures 3a; 3b). Transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) showed no pericardial effusion. Lead explantation was scheduled. The right ventricular lead was then retracted into the right ventricle and explanted under surveillance by transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) with cardiothoracic backup in the operation room. TEE showed intraoperatively no pericardial effusion. The patient presented stable hemodynamics during the whole procedure. In the next step, a new ventricular lead (Medtronic 5076-58 cm) was implanted via transvenous approach. Under stable conditions, the patient was admitted to the intensive care unit for close monitoring. There was no pericardial effusion prior to discharge and chest X-ray demonstrated correct position of the leads (Figure 4). The patient was discharged with correct pacemaker function on the second postoperative day.

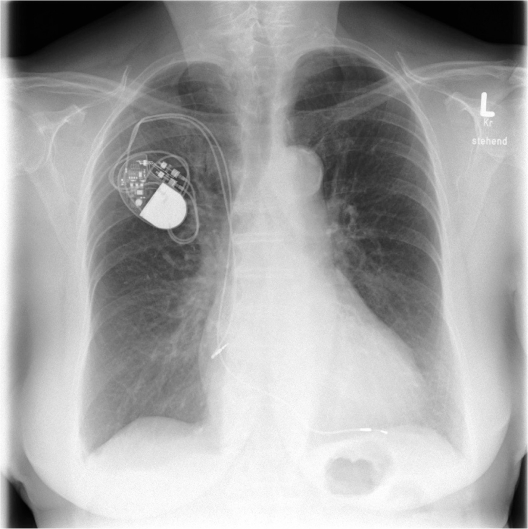

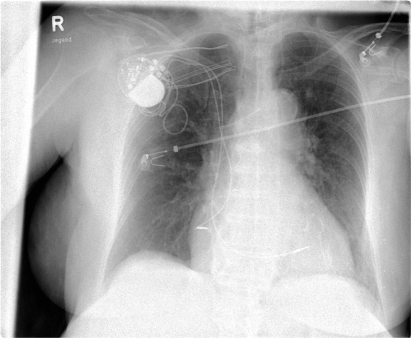

Figure 1.

Chest X-ray after pacemaker implantation.

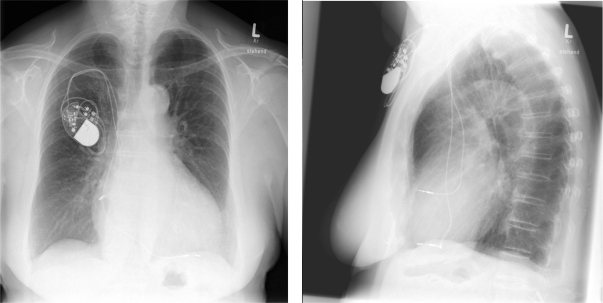

Figure 2.

A) Three-month follow-up chest X-ray; B) three-month follow-up lateral chest X-ray suspicious of dislocation.

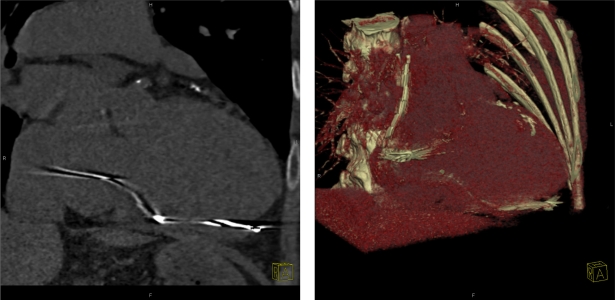

Figure 3.

A) Chest computed tomography (CT) shows a perforated ventricular lead tip through the right ventricle and pericardium. B) 3D-recontruction of CT shows a perforated ventricular lead tip through the right ventricle and pericardium.

Figure 4.

Chest X-ray prior to discharge demonstrates correct position of the leads.

Discussion

Unlike acute myocardial perforation, that has been reported to occur in 1%–7% of pacemaker implantation,1 late perforation (diagnosed later than one month after implantation) is less well recognized as a classic complication of pacemaker implantation. Clinical presentation of late perforation may vary widely from asymptomatic patients to sudden cardiac death. This highlights the importance of a high degree of suspicion and the need of proper diagnostic methods. In our case, the patient showed neither of the typical symptoms like chest pain, diaphragmatic pacing or pericardial friction rubs.8 But ECG showed failure of ventricular sensing and pacing. Chest X-ray was not suspicious for myocardial perforation and CT-scan, showing the lead’s tip outside the heart shadow, was necessary to make the diagnosis. In our opinion, imaging diagnostic with CT-scan should be reserved for patients with unsuspicious chest X-ray presenting with an exit-block at least one month after implantation.

Currently, appropriate management of lead perforation is uncertain. Furthermore, the management described in the literature depends on the lead type. While active fixation leads have mostly been extracted transvenously after retraction of the coil, extraction of passive fixation leads causes concern because of the bulky tip of the lead may cause tissue damage during removal. Khan and colleagues recommend that lead extraction should be done in the operating room under TEE observation with cardiac surgery backup.4 Although open chest surgery offers more safety in the extraction of the lead, this invasive procedure is associated with increased hospital stay. In our opinion, removal and repositioning of the perforated lead or implantation of a new one are less invasive as open chest surgery. An alternative approach to minimize the risk of perforation could be to place the lead in sites other than the right ventricular apex such as the atrial or ventricular septal walls.9

Conclusions

Delayed lead perforation is a rare complication of pacemaker implantation. Considering our findings and those of others, management schemes for patients who present with delayed lead perforation should be provided.

References

- 1.Kiviniemi MS, Pirnes MA, Eränen HJ, Kettunen RV, Hartikainen JE. Complications related to permanent pacemaker therapy. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 1999;22:711–720. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8159.1999.tb00534.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Trigano JA, Paganelli F, Richard P, et al. Perforation du Cœur après Implantation Transveineuse de Stimulation Cardiaque. Presse Med. 1999;28:836–840. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ellenbogen KA, Wood MA, Shepard RK. Delayed complications following pacemaker implantation. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2002;25:1155–1158. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9592.2002.01155.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Khan M, Joseph G, Khaykin Y, Ziada K, Wilkoff B. Delayed lead perforation: A disturbing trend. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2005;28:251–253. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8159.2005.40003.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Akyol A, Aydin A, Erdinler I, Oguz E. Late perforation of the heart, pericardium, and diaphragm by an active-fixation ventricular lead. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2005;28:350–351. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8159.2005.09374.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sanoussi A, El Nakadi B, Lardinois I, De Bruyne Y, Joris M. Late right ventricular perforation after permanent pacemaker implantation: How far can the lead go. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2005;28:723–725. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8159.2005.00156.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Velavan P. An unusual presentation of delayed cardiac perforation caused by atrial screw in lead. Heart. 2003;89:364. doi: 10.1136/heart.89.4.364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Asano M, Mishima A, Ishii T, Takeuchi Y, Suzuki Y, Manabe T. Surgical treatment for right ventricular perforation caused by transvenous pacing electrodes: a report of three cases. Surg Today. 1996;26(11):933–935. doi: 10.1007/BF00311800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vlay SC. Complications of active-fixation electrodes. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2002;25(8):1153–1154. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9592.2002.01153.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]