Abstract

The nicotinic acetylcholine receptor (nAChR) has been studied extensively for well over four decades because of its important physiological roles and medical relevance. A large body of data from biochemical and biophysical studies are now available. The structural information, which is needed to integrate existing data to address the mechanism and function of nAChRs, started to emerge in recent years. Structural studies of acetylcholine binding proteins (AChBPs) have greatly facilitated the study of nAChRs. The recently determined crystal structures of the prokaryotic homologues of nAChRs will probably have similar impact over time. However, a direct structural model of nAChRs at high resolution will be important for mechanistic studies and drug development. Here we will review some of the recent efforts in this area and use the high-resolution structure of the extracellular domains of nAChR α1 to illustrate the potential insights one may gain at higher resolution.

Lin Chen (University of Southern California, USA) obtained his PhD degree in Chemistry and Biochemistry in the Department of Chemistry at Harvard University in 1994. He did his postdoctoral training in structural biology in the Department of Molecular and Cellular Biology at Harvard University. His research interests include: (i) mechanisms of eukaryotic gene regulation, including the molecular basis of signal transduction, transcription regulation and epigenetic control of chromosome structure; (ii) structure and function of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChRs) and other ligand-gated ion channels (LGICs) involved in neuronal signalling.

Nicotinic acetylcholine receptors – function and mechanism

The nicotinic acetylcholine receptor (nAChR) is the founding member of the Cys-loop super family of pentameric ligand-gated ion channels (LGICs). This family also includes serotonin 5-HT3, γ-aminobutyric acid (GABAA and GABAC) and glycine receptors (Corringer et al. 2000; Lester et al. 2004). These receptors function in the central and peripheral nervous system and are important pharmaceutical targets for many human diseases such as myasthenia gravis, epilepsy, schizophrenia, depression and substance addiction (Jackson, 1999).

nAChRs function as a pentamer of identical or homologous subunits. Each subunit consists of an extracellular domain (ECD), four transmembrane helices (TM1–4), and a small intracellular region (Karlin, 2002). The nAChR pentamer has two main functional modules, the extracellular module that recognizes and binds neurotransmitters between specific subunit interfaces, and the transmembrane module (TM), that form a cation- or anion-selective ion channel. A variety of models has been proposed to explain how the extracellular module is coupled to the transmembrane module through allosteric mechanisms (Grosman et al. 2000; Chakrapani et al. 2004; Gao et al. 2005; Law et al. 2005; Taly et al. 2005; Sine & Engel, 2006; Lape et al. 2008). But exactly how the binding of neurotransmitters to the extracellular module controls the opening or closing of the ion channel has been a long-standing question in the field.

nAChRs have been extensively analysed by biochemical, biophysical and electrophysiological experiments (Sine & Engel, 2006). These studies have provided a wealth of information about the role of specific residues in ligand binding and channel function. nAChR is particularly suited for detailed and quantitative kinetic and thermodynamic analyses, through single channel recording, which have provided rich insights into energetic coupling of functional residues and temporal profile of the transition state (Grosman et al. 2000; Sine & Engel, 2006; Auerbach, 2007; Jha et al. 2007; Purohit et al. 2007; Purohit & Auerbach, 2007; Lape et al. 2008; Lee et al. 2009). These analyses, when combined with high-resolution structure and dynamic information, could provide unprecedented insights into the basic mechanism of allosteric regulation not only in nAChRs but also a broad range of other proteins.

High-resolution structure of nAChR: current status, challenges and strategies

Tremendous efforts have been put into pursuing the atomic structure of nAChRs. Electron microscopic analyses of nAChRs from Torpedo marmorata by Unwin and colleagues have led to a 4 Å resolution model of the intact channel (Miyazawa et al. 2003; Unwin, 2005), providing so far the most comprehensive structural information for nAChRs. The structural details, however, are limited by the relatively low resolution. In this regard, the high-resolution structure of the acetylcholine binding protein (AChBP) published by Sixma and colleagues in 2001 was a major breakthrough (Brejc et al. 2001). AChBP shares ∼24% sequence identity with nAChRs and has the same pentameric assembly. Its structures in different bound states have provided detailed information on the binding of a variety of agonists and antagonists (Rucktooa et al. 2009). But AChBP does not function as an ion channel and may lack necessary structural features required for transmitting the ligand-binding signal across the protein body (Karlin, 2004; Dellisanti et al. 2007a). Recently, the crystal structures of prokaryotic homologues of nAChR have been determined from different species and in different states (Hilf & Dutzler, 2008, 2009; Bocquet et al. 2009). These structures together with detailed biochemical and biophysical characterization will probably provide a great model system to study the fundamental mechanisms of ligand-dependent channel gating (Bocquet et al. 2007). However, due to the limited sequence identity, direct structural information of nAChR at high resolution will still be needed for dissecting its mechanism and for drug development (Taly et al. 2009).

Although large quantities of nAChRs were available from Torpedo electric ray organ, crystallization was not successful, probably because of the heterogeneity of the protein samples prepared from the natural source (Wells, 2008). Heterologous expression in bacteria results in insoluble protein due to the lack of proper post-translation modifications such as glycosylation. The yeast Pichia pastoris has been a favourable recombinant system for overexpressing nAChRs because of its mammalian-like glycosylation system. However, the expressed nAChR protein or ECD is often unstable, leading to aggregation and low yield (Psaridi-Linardaki et al. 2002; Yao et al. 2002). Strategies to overcome this difficulty include expressing different family members of nAChR or its sub-domain (mostly ECD), constructing an AChBP-nAChR chimera, and introducing specific mutations to enhance expression and stability (Zouridakis et al. 2009). We used the latter approach by screening a PCR-generated mutant library of mouse nAChR α1 ECD for variants with increased expression and stability (Dellisanti et al. 2007a). This has led to the isolation of a triple mutant (V8E/W149R/V155A) that has much improved expression and stability compared with the wild-type protein. We have determined the crystal structure of this nAChR α1 ECD variant bound to α-bungarotoxin at 1.94 Å resolution (Dellisanti et al. 2007a). Structure comparison with the 4 Å electron microscopic model of nAChR and AChBP reveals that the isolated ECD is very similar to its counterpart in the intact channel and that the stabilizing mutations do not appear to alter the overall structure of the ECD. This comparison also confirms that AChBP is indeed a close structural homologue of nAChR ECD. Although the W149R mutation disrupted the ligand-binding site, its impact on the structural interpretation of the isolated ECD is small.

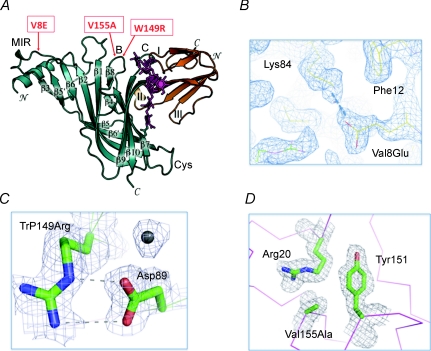

How do the mutations stabilize the nAChR α1 ECD? The three mutations all map to the surface of the protein (Fig. 1A), with one (V8E) located on the N-terminal helix and the other two (W149R and V155A) on loop B. The V8E mutation introduces a salt bridge with Lys84 (Fig. 1B), whereas the W149R mutation introduces a salt bridge with Asp89 (Fig. 1C). These salt bridges apparently contribute to protein stability as evident by the well-defined electron density of these exposed residues with long and charged side chains. Thus, the mutations seem to enhance the protein stability through at least two mechanisms. One is to remove surface-exposed hydrophobic residues, including V155A (Fig. 1D); the other is to introduce salt bridges on the protein surface. These observations suggest that the ECD of nAChR may be rationally engineered to improve solubility and stability. In principle, one can use homology models to guide the selection of exposed hydrophobic residues and to engineer surface salt bridges. Such an approach could facilitate the high-resolution structural studies of the ECD of other nAChR subunits or the intact channel.

Figure 1. Mutations that stabilize nAChR α1 ECD.

A, the three mutations (boxed and indicated by arrow) are mapped on the surface of nAChR α1 ECD (dark green) and away from the binding site of α-bungarotoxin (orange) and the glycan (magenta). B, the mutation Val8Glu establishes a salt bridge with Lys84. The surrounding structure is well ordered, showing well-defined electron density. C, the mutation Trp149Arg establishes a salt bridge with Asp89. The side chains of both residues show well-defined electron density. D, the mutation Val151Ala removes an exposed hydrophobic residue. The surrounding structure is well ordered.

Receptor-specific structural features and their functional implications

The high-resolution structure of the nAChR α1 ECD reveals many receptor-specific features that are absent in AChBP or not well defined at lower resolution. These structural features, when put into the context of the intact structural model of nAChR, can provide new insights into its functional mechanism. For example, the main immunogenic region (MIR, residues 66–76 of α1) has been located at an upper protruding point near the N-terminus of the ECD (Tzartos et al. 1991). The high-resolution structure shows that this region has well-defined electron density; its structure is stabilized by extensive interactions with the surrounding protein elements, including the N-terminal α-helix and the β5–β6 loop (Dellisanti et al. 2007a) (Fig. 2). This structural feature is consistent with the observation that most autoimmune antibodies from myasthenia patients bind the intact receptor tighter than isolated MIR peptides (Tsouloufis et al. 2000). Furthermore, recent studies based on chimera mapping demonstrated that the interaction between MIR and the N-terminal α-helix (residues 1–14) is important for the binding of autoimmune antibodies (Luo et al. 2009). These studies also showed that the antibodies may contact additional regions on the intact receptor, including the loop between the N-terminal α-helix and first β strand (residues 15–32). This loop is close to MIR in the 3-D structure (Fig. 1A).

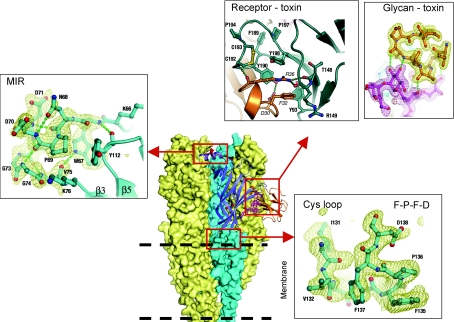

Figure 2. Receptor-specific structural features and their functional implications.

The high-resolution structure of nAChR α1 ECD bound to α-bungarotoxin was put into the electron microscopic model of nAChR. The details of MIR, the Cys-loop and the toxin-binding interactions with receptor and glycan are shown in the indicated boxes.

The Cys-loop, which is the signature motif that defines the Cys-loop super family of LGICs, also shows well-defined electron density. However, in contrast to MIR, the structure of the Cys-loop appears to be intrinsically folded, involving little interaction with the rest of the protein. Consistent with this observation, previous studies have shown that peptides containing the Ar-Pro-Ar-Asp motif (Ar = Phe or Tyr) have a high tendency to form type IV turns wherein the proline residue adopts a characteristic cis conformation (Yao et al. 1994; Wu & Raleigh, 1998). This is indeed observed in the high-resolution structure of nAChR α1 ECD (Fig. 2). The electron microscopic model predicts that the Cys-loop interacts with the M2–M3 loop (Unwin, 2005). Energetic coupling studies suggest that this interaction is important for channel function (Jha et al. 2007; Lee et al. 2009). A stable structure or at least partially stable structure of the Cys-loop may be important for the coupling between the ECD and TM modules because a completely flexible Cys-loop will be less effective in applying a ‘dragging’ force on the M2–M3 loop.

The ECD of nAChR is modified by N-linked glycosylations that are important for receptor folding, assembly and trafficking (Gehle et al. 1997). It also harbours the binding sites for a variety of toxins that inhibit nAChR (Changeux et al. 1970; Tsetlin et al. 2009). A 4.2 Å resolution structure of AChBP bound by α-cobratoxin has been previously solved, which provided a model for how the toxin binds the nAChR pentamer (Bourne et al. 2005). Here the high-resolution structure shows that α-bungarotoxin binds to nAChR through extensive toxin–receptor contacts as well as previously unobserved toxin–glycan interactions (Fig. 2). Deglycosylation studies suggest that the glycan is indeed important for the high-affinity binding by α-bungarotoxin to nAChR (Dellisanti et al. 2007a), which is consistent with previous observations (Psaridi-Linardaki et al. 2002). The structure also explains why specific mutations of nAChR in certain species can confer toxin resistance (Dellisanti et al. 2007b).

Potential roles of glycan in channel gating

The crystal structure reveals a long glycan chain with well-defined electron density (Fig. 3A). The glycan adopts an extended conformation and engages in extensive interactions with the receptor and toxin. The glycan chain is covalently attached to Asn141 on the Cys-loop and stretches out to interact with a number of aromatic residues on the backside of loop C, thus providing a physical linker between the two functionally important loops. Structural studies of AChBP reveal that the most significant structural change induced by ligand binding is the closing-down movement of loop C (Celie et al. 2004). Ample evidence also suggests that the Cys-loop is a key structural element to interact with the TM module (Jha et al. 2007; Lee et al. 2009). The crystal structure suggests that the glycan chain may play a role in relaying the signal of ligand binding from loop C to the Cys-loop. Preliminary analyses by deglycosylation suggest that the sugar chain is indeed important for channel function (Dellisanti et al. 2007a). The glycosylation site on the Cys-loop is conserved in muscle-specific nAChRs and some members of the pentameric LGIC super family. Other LGICs have glycosylation sites at different locations. Given its extended structure and dynamic conformation (Qasba, 2000), carbohydrate is particularly suited for coupling distal structural elements. It is therefore possible that glycan may have a general role in ligand-mediated channel gating in many LGICs. Different glycosylation sites may reflect the variability in the detailed gating mechanisms among different classes of LGICs.

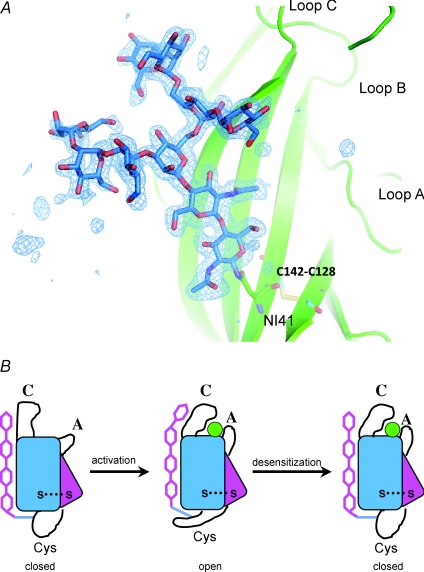

Figure 3. Potential roles of glycan in nAChR channel gating.

A, the crystal structure reveals that the glycan chain provides a physical linker between loop C and the Cys-loop. B, a hypothetical model of the roles of glycan in nAChR channel gating.

The proposed function of glycan in nAChRs may also have implications for the desensitization mechanism. As shown in a hypothetical model (Fig. 3B, only the α subunit is shown), when the agonist enters the binding site, loop C caps on the ligand, dragging the carbohydrate chain upward, which in turn pulls the Cys-loop upward to cause the movement of the transmembrane helices, resulting in the opening of the ion channel (Fig. 3B, middle). In reaching the open state, the sugar chain is probably in a stretched, high-energy conformation. Carbohydrates usually have a flexible backbone and can interact with protein in a relatively non-discriminative manner (Qasba, 2000). Thus, if the agonist persists in the binding site over a long period of time, the sugar chain may recoil and detach from loop C, resulting in the relaxation of the Cys-loop and rendering the receptor channel desensitized (Fig. 3B, right). In such a desensitized state, loop C may bind the ligand tighter while the Cys-loop reverts to the resting state. Future studies will be needed to test these hypotheses.

Specific packing defect in nAChR ECD is important for channel function

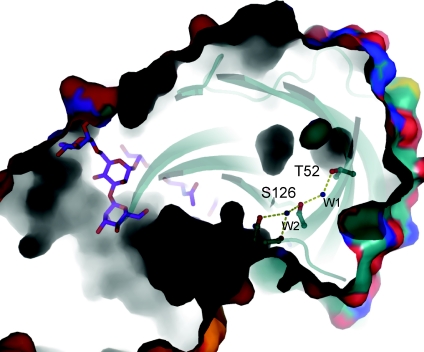

Most proteins have a densely packed hydrophobic core that is important for stable folding in aqueous solution. The discovery of a hydration pocket inside the β sandwich core of the nAChR ECD is therefore somewhat surprising (Fig. 4) (Dellisanti et al. 2007a). This hydration pocket consists of two buried hydrophilic residues, Thr52 and Ser126, two ordered water molecules, and a few cavities, creating a packing defect near the disulfide that connects the two β sheets. Both Thr52 and Ser126 are highly conserved in nAChRs but are substituted by large hydrophobic residues (Phe, Leu or Val) in the non-channel homologue AChBPs. This observation suggests that the nAChR ECD has evolved with a non-optimally packed core, hence predisposed to undergo conformational change during ligand-induced gating. Replacing Thr52 and Ser126 with their hydrophobic counterparts in AChBP significantly impaired the gating function of nAChR without affecting the folding of the protein structure (Dellisanti et al. 2007a). This role of the hydration pocket on the conformation flexibility/dynamics of the nAChR ECD is supported by recent molecular dynamics studies (Cheng et al. 2009). Taken together, loop C, the carbohydrate chain, and the Cys-loop surrounding the disulfide function as a group of physically linked mobile elements that couple ligand binding to channel gating (Fig. 5). The buried water molecules, which are strategically located at the hinge point of these mobile elements, could serve as the lubricant by dynamic exchange with bulk water molecules (Cheng et al. 2009). This model also suggests that the specific location of the hydration cavity is important for a particular class of pentameric LGICs (C. D. Dellisanti, & L. Chen, unpublished observations). Studies are underway to address the functional roles of structure-predicted packing cavities in other members of the Cys-loop family of LGICs.

Figure 4. Specific packing defect that is conserved in nAChR but absent in AChBP.

The structure of the nAChR α1 ECD is represented by a ribbon and surface model. Shown is a cross-section of the structure viewed from the stop of the β sandwich fold. Thr52, Ser126, the two buried water molecules and nearby cavities are evident from this view.

Figure 5. A summary model of high-resolution studies of the nAChR α1 ECD and the mechanistic implications in the whole receptor.

One subunit of the nAChR pentamer is highlighted in red (depicted in ribbon). Other subunits are coloured in grey (two are visible in this view). Loop C, the carbohydrate chain (in space-filling model), the Cys-loop, and the hydration pocket (the two buried water molecules are shown as blue spheres) function as a group of physically linked mobile elements (boxed).

Concluding remarks

The high-resolution structure of the nAChR α1 ECD reveals atomic details of many receptor-specific structural features. Some of these features can be interpreted by existing data, while others suggest new hypotheses regarding the function of nAChRs that can be tested experimentally. There are also structural features observed at high resolution whose functional role is not clear at present. For example, a large number of surface residues on the nAChR α1 ECD show two distinct side chain conformations. These include Thr52, Asn53, Tyr93 to Asp97, Val19, Val103, Tyr127, Asp138, Lys145 and Arg209. Many of these residues have been implicated in gating function, but the exact mechanisms are not clear.

Finally, the high-resolution structure could facilitate the search for small molecules that bind nAChR and modulate its function positively (positive allosteric modulator, PAM) or negatively (negative allosteric modulator, NAM). Such small molecules may be used to regulate the activity of nAChR for the treatment of diseases associated with weakened or excessive nAChR activity (Bertrand & Gopalakrishnan, 2007). A particularly attractive aspect of this therapeutic approach is that the PAM or NAM will not by itself activate or inhibit the channel, but rather work in the presence of endogenous neurotransmitters, thereby preserving the physiological temporal and spatial activity of nAChRs. Detailed examination of the crystal structure of the nAChR α1 ECD reveals four surface pockets that bind clusters of ordered solvent molecules, one of which was identified as isopropanol (K. Daugherty & L. Chen, unpublished observations). These solvent-binding pockets could guide the search for small molecules that bind nAChR by docking and/or soaking and co-crystallization. Once identified, the compounds can be further analysed to see if they can modulate the function of nAChRs. Conversely, compounds found by functional screen as PAMs or NAMs of nAChRs could be analysed by docking using the solvent density as a guide, or by direct soaking and co-crystallization for structure determination. The structural information will guide the optimization of leading compounds through synthetic modifications.

Given the potential impact on mechanistic study and drug development, it will be important to determine the high-resolution structures of the ECD of other nAChR members and LGICs. The pentameric form of ECD will be an important target of structural studies, while the high-resolution structure of the intact mammalian nAChR or other Cys-loop LGICs represents the ultimate and much more challenging goal.

Acknowledgments

The author wishes to thank Cosma Dellisanti, Kate Daugherty, Henry Lester, Dennis Dougherty, Tony Auerbach, Steve Sine, and Thomas Balle for helpful discussion, and Dr Raja Dey for illustration preparation. This work is supported by grants from NIH and by a startup fund from the University of Southern California. The author would like to dedicate this paper to Professor Zuo-Zhong Wang, a major contributor to the structural study of the nAChR α1 ECD, who died in a climbing accident in the summer of 2008.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- AChBP

acetylcholine binding protein

- ECD

extracellular domain

- LGIC

ligand-gated ion channel

- MIR

main immunogenic region

- nAChR

nicotinic acetylcholine receptor

- TM

transmembrane module

References

- Auerbach A. How to turn the reaction coordinate into time. J Gen Physiol. 2007;130:543–546. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200709898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertrand D, Gopalakrishnan M. Allosteric modulation of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. Biochem pharmacol. 2007;74:1155–1163. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2007.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bocquet N, Nury H, Baaden M, Le Poupon C, Changeux JP, Delarue M, Corringer PJ. X-ray structure of a pentameric ligand-gated ion channel in an apparently open conformation. Nature. 2009;457:111–114. doi: 10.1038/nature07462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bocquet N, Prado de Carvalho L, Cartaud J, Neyton J, Le Poupon C, Taly A, Grutter T, Changeux JP, Corringer PJ. A prokaryotic proton-gated ion channel from the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor family. Nature. 2007;445:116–119. doi: 10.1038/nature05371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourne Y, Talley TT, Hansen SB, Taylor P, Marchot P. Crystal structure of a Cbtx-AChBP complex reveals essential interactions between snake α-neurotoxins and nicotinic receptors. EMBO J. 2005;24:1512–1522. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brejc K, van Dijk WJ, Klaassen RV, Schuurmans M, Van Der Oost J, Smit AB, Sixma TK. Crystal structure of an ACh-binding protein reveals the ligand-binding domain of nicotinic receptors. Nature. 2001;411:269–276. doi: 10.1038/35077011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Celie PH, van Rossum-Fikkert SE, van Dijk WJ, Brejc K, Smit AB, Sixma TK. Nicotine and carbamylcholine binding to nicotinic acetylcholine receptors as studied in AChBP crystal structures. Neuron. 2004;41:907–914. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(04)00115-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chakrapani S, Bailey TD, Auerbach A. Gating dynamics of the acetylcholine receptor extracellular domain. J Gen Physiol. 2004;123:341–356. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200309004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Changeux JP, Kasai M, Lee CY. Use of a snake venom toxin to characterize the cholinergic receptor protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1970;67:1241–1247. doi: 10.1073/pnas.67.3.1241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng X, Ivanov I, Wang H, Sine SM, McCammon JA. Molecular-dynamics simulations of ELIC – a prokaryotic homologue of the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor. Biophys J. 2009;96:4502–4513. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2009.03.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corringer PJ, Le Novere N, Changeux JP. Nicotinic receptors at the amino acid level. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2000;40:431–458. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.40.1.431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dellisanti CD, Yao Y, Stroud JC, Wang ZZ, Chen L. Crystal structure of the extracellular domain of nAChR α1 bound to α-bungarotoxin at 1.94 Å resolution. Nat Neurosci. 2007a;10:953–962. doi: 10.1038/nn1942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dellisanti CD, Yao Y, Stroud JC, Wang ZZ, Chen L. Structural determinants for α-neurotoxin sensitivity in muscle nAChR and their implications for the gating mechanism. Channels (Austin, Tex) 2007b;1:234–237. doi: 10.4161/chan.4909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao F, Bren N, Burghardt TP, Hansen S, Henchman RH, Taylor P, McCammon JA, Sine SM. Agonist-mediated conformational changes in acetylcholine-binding protein revealed by simulation and intrinsic tryptophan fluorescence. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:8443–8451. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M412389200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gehle VM, Walcott EC, Nishizaki T, Sumikawa K. N-Glycosylation at the conserved sites ensures the expression of properly folded functional ACh receptors. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 1997;45:219–229. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(96)00256-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grosman C, Zhou M, Auerbach A. Mapping the conformational wave of acetylcholine receptor channel gating. Nature. 2000;403:773–776. doi: 10.1038/35001586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilf RJ, Dutzler R. X-ray structure of a prokaryotic pentameric ligand-gated ion channel. Nature. 2008;452:375–379. doi: 10.1038/nature06717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilf RJ, Dutzler R. Structure of a potentially open state of a proton-activated pentameric ligand-gated ion channel. Nature. 2009;457:115–118. doi: 10.1038/nature07461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson MB. Ligand-gated channel: postsynaptic receptors and drug targets. Adv Neurol. 1999;79:511–524. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jha A, Cadugan DJ, Purohit P, Auerbach A. Acetylcholine receptor gating at extracellular transmembrane domain interface: the cys-loop and M2-M3 linker. J Gen Physiol. 2007;130:547–558. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200709856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karlin A. Emerging structure of the nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2002;3:102–114. doi: 10.1038/nrn731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karlin A. A touching picture of nicotinic binding. Neuron. 2004;41:841–842. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(04)00151-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lape R, Colquhoun D, Sivilotti LG. On the nature of partial agonism in the nicotinic receptor superfamily. Nature. 2008;454:722–727. doi: 10.1038/nature07139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Law RJ, Henchman RH, McCammon JA. A gating mechanism proposed from a simulation of a human α7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:6813–6818. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0407739102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee WY, Free CR, Sine SM. Binding to gating transduction in nicotinic receptors: Cys-loop energetically couples to pre-M1 and M2-M3 regions. J Neurosci. 2009;29:3189–3199. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6185-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lester HA, Dibas MI, Dahan DS, Leite JF, Dougherty DA. Cys-loop receptors: new twists and turns. Trends Neurosci. 2004;27:329–336. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2004.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo J, Taylor P, Losen M, de Baets MH, Shelton GD, Lindstrom J. Main immunogenic region structure promotes binding of conformation-dependent myasthenia gravis autoantibodies, nicotinic acetylcholine receptor conformation maturation, and agonist sensitivity. J Neurosci. 2009;29:13898–13908. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2833-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyazawa A, Fujiyoshi Y, Unwin N. Structure and gating mechanism of the acetylcholine receptor pore. Nature. 2003;423:949–955. doi: 10.1038/nature01748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Psaridi-Linardaki L, Mamalaki A, Remoundos M, Tzartos SJ. Expression of soluble ligand- and antibody-binding extracellular domain of human muscle acetylcholine receptor α subunit in yeast Pichia pastoris. Role of glycosylation in α-bungarotoxin binding. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:26980–26986. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110731200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purohit P, Auerbach A. Acetylcholine receptor gating: movement in the α-subunit extracellular domain. J Gen Physiol. 2007;130:569–579. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200709858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purohit P, Mitra A, Auerbach A. A stepwise mechanism for acetylcholine receptor channel gating. Nature. 2007;446:930–933. doi: 10.1038/nature05721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qasba P. Involvement of sugars in protein-protein interactions. Carbohydr Polym. 2000;41:293–309. [Google Scholar]

- Rucktooa P, Smit AB, Sixma TK. Insight in nAChR subtype selectivity from AChBP crystal structures. Biochem Pharmacol. 2009;78:777–787. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2009.06.098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sine SM, Engel AG. Recent advances in Cys-loop receptor structure and function. Nature. 2006;440:448–455. doi: 10.1038/nature04708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taly A, Corringer PJ, Guedin D, Lestage P, Changeux JP. Nicotinic receptors: allosteric transitions and therapeutic targets in the nervous system. Nat Rev. 2009;8:733–750. doi: 10.1038/nrd2927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taly A, Delarue M, Grutter T, Nilges M, Le Novere N, Corringer PJ, Changeux JP. Normal mode analysis suggests a quaternary twist model for the nicotinic receptor gating mechanism. Biophys J. 2005;88:3954–3965. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.104.050229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsetlin V, Utkin Y, Kasheverov I. Polypeptide and peptide toxins, magnifying lenses for binding sites in nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. Biochem Pharmacol. 2009;78:720–731. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2009.05.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsouloufis T, Mamalaki A, Remoundos M, Tzartos SJ. Reconstitution of conformationally dependent epitopes on the N-terminal extracellular domain of the human muscle acetylcholine receptor α subunit expressed in Escherichia coli: implications for myasthenia gravis therapeutic approaches. Int Immunol. 2000;12:1255–1265. doi: 10.1093/intimm/12.9.1255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tzartos SJ, Barkas T, Cung MT, Kordossi A, Loutrari H, Marraud M, Papadouli I, Sakarellos C, Sophianos D, Tsikaris V. The main immunogenic region of the acetylcholine receptor. Structure and role in myasthenia gravis. Autoimmunity. 1991;8:259–270. doi: 10.3109/08916939109007633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unwin N. Refined structure of the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor at 4 Å resolution. J Mol Biol. 2005;346:967–989. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.12.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wells GB. Structural answers and persistent questions about how nicotinic receptors work. Front Biosci. 2008;13:5479–5510. doi: 10.2741/3094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu WJ, Raleigh DP. Local control of peptide conformation: stabilization of cis proline peptide bonds by aromatic proline interactions. Biopolymers. 1998;45:381–394. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0282(19980415)45:5<381::AID-BIP6>3.0.CO;2-H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao J, Dyson HJ, Wright PE. Three-dimensional structure of a type VI turn in a linear peptide in water solution. Evidence for stacking of aromatic rings as a major stabilizing factor. J Mol Biol. 1994;243:754–766. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(94)90045-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao Y, Wang J, Viroonchatapan N, Samson A, Chill J, Rothe E, Anglister J, Wang ZZ. Yeast expression and NMR analysis of the extracellular domain of muscle nicotinic acetylcholine receptor α subunit. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:12613–12621. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M108845200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zouridakis M, Zisimopoulou P, Eliopoulos E, Poulas K, Tzartos SJ. Design and expression of human α7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor extracellular domain mutants with enhanced solubility and ligand-binding properties. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1794:355–366. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2008.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]