Abstract

There is a sex difference in the blood pressure (BP) responses to prooxidants and antioxidants in the spontaneously hypertensive rat (SHR). In contrast to males, BP in female SHR does not decrease in response to antioxidants, such as tempol or apocynin, or increase in response to the prooxidant, molsidomine. Molsidomine decreases BP and increases expression of antioxidants in male Wistar-Kyoto rats (WKY), but not male SHR. The present study tested the hypothesis that the mechanism responsible for the lack of a pressor response to molsidomine in females is due to higher endogenous nitric oxide (NO) or to compensatory upregulation of renal antioxidant enzymes. Female SHR were treated with molsidomine in the presence or absence of nitro-l-arginine methyl ester (l-NAME) for 2 wk. Molsidomine increased nitrate/nitrite (NOx) and F2-isoprostane (F2-IsoP) excretion, whereas l-NAME reduced NOx but increased F-Isop. Molsidomine and l-NAME together further reduced NOx and increased F2-IsoP. Molsidomine alone had no effect on BP; l-NAME alone increased BP. The combination of molsidomine and l-NAME did not increase BP above l-NAME alone levels. Whole body and renal oxidative stress increased, while renal cortical Cu,Zn-SOD expression was downregulated and catalase was upregulated by molsidomine; glutathione peroxidase expression was unaffected. These data support our previous studies suggesting that BP in female SHR is independent of either increases or decreases in oxidative stress. The mechanisms responsible for the sex difference in BP response to increase or decrease of oxidative stress are not due to increased NO in females or to compensatory upregulation of antioxidant enzymes in response to increases in oxidants.

Keywords: F2-isoprostanes, lucigenin chemiluminescence, sexual dimorphism, hypertension, catalase, prooxidant

experimental studies suggest that oxidative stress contributes to the development and maintenance of hypertension in humans and animals (11, 17). The spontaneously hypertensive rat (SHR) is a genetic model of essential hypertension in which blood pressure is higher in males than in females (12). In male SHR, we and others have shown that the hypertension is mediated via oxidative stress since both tempol, the superoxide dismutase mimetic, and apocynin, the NADPH oxidase inhibitor, reduce blood pressure (7, 14, 16). In addition, increasing oxidative stress with molsidomine, a compound that releases equimolar amounts of superoxide and NO and that decreases blood pressure in male Wistar-Kyoto rats (WKY), increases blood pressure in male SHR, in part, due to lack of adequate buffering by upregulation of both antioxidant enzymes, catalase and glutathione peroxidase (4).

In contrast to male SHR, we have previously demonstrated that reactive oxygen species (ROS) do not play a role in the maintenance of hypertension in female SHR (5). For example, neither tempol nor apocynin reduced blood pressure in female SHR when they were 12 wk of age, during the established phase of the hypertension (14). While we hypothesized at first that female SHR may have significantly less oxidative stress than males, this was not the case, and in some tissues, oxidative stress, measured by F2-isoprostanes or lucigenin chemiluminescence, was significantly higher in females than males (14). Finally, while molsidomine increased ROS, blood pressure failed to increase in female SHR treated with molsidomine (14). However, we did not evaluate the expression of the antioxidant enzymes with molsidomine treatment in those studies.

We hypothesized then that female SHR may have higher levels of endogenous nitric oxide (NO) than males that could combat ROS and protect against the increase in BP. We have shown previously that without adequate NO, antioxidants are unable to reduce BP (18). The molsidomine data could be explained if NO levels in female SHR are sufficiently high to overcome increases in superoxide from molsidomine. Alternatively, since male WKY also do not increase BP in response to molsidomine, presumably due, in part, to increases in antioxidant enzyme expression, we also determined whether an increase in renal expression of antioxidant enzymes, Cu,Zn-SOD, glutathione peroxidase, and catalase could prevent molsidomine-induced oxidative stress and therefore play a role in protecting against the increase in BP in female SHR with molsidomine. Therefore, the present study was performed to test these hypotheses by administering molsidomine in the presence or absence of nitro-l-arginine methyl ester (l-NAME), the NO synthase inhibitor, in female SHR.

METHODS

Animals

Studies were performed using female SHR, aged 13–14 wk (Taconic Laboratories, Germantown, NY). Animals were housed in a temperature-controlled room (23°C) with 12:12-h light-dark cycle and were maintained on standard rat chow (Harlan Teklad, Madison, WI). All experimental procedures were executed in accordance with National Institutes of Health Guidelines for the Use and Care of Laboratory Animals and with approval by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Mississippi Medical Center.

Experiment 1

The study was designed over 2 wk, such that one group of female SHR (n = 6/group; group 1) received tap water during the first 7 days and l-NAME (4.5 mg·kg−1·day−1 in tap water) during the second 7-day period; and the other group of female SHR (n = 7/group; group 2) received molsidomine (30 mg·kg−1·day−1 in tap water) during the first 7 days of the study and molsidomine + l-NAME during the second 7 days. Blood pressure was measured continuously by telemetry throughout the study, and 24-h urine collections were performed for urinary excretion of F2-isoprostanes and nitrate/nitrite by placing rats in metabolism cages on days 7 and 14 of the experiment. Rats were weighed every 3 days, and the doses of molsidomine and l-NAME were adjusted accordingly.

Measurement of urinary nitrate/nitrite.

As an index of NO production, nitrate and nitrite concentration in 24-h-urine samples were measured at days 7 and 14 of the experiment, and were done by the Griess Reagent method, using Escherichia coli to convert nitrate to nitrite, as we described previously (13). The data are presented as nitrate/nitrite excreted per day per kilogram of body weight.

Measurement of F2-isoprostane as an indicator of oxidative stress.

The measurement of F2-isoprostane in urine was done on days 7 and 14 of the protocol. 8-iso-PGF2 (F2-isoprostane) was measured by commercially available a kit (EA 85 Oxford Biomedical Research), as we previously described (14). F2-isoprostanes are expressed as nanograms F2-isoprostanes per milligram urinary creatinine, as measured by creatinine kit (CR01; Oxford Biomedical Research, Oxford, MI).

Measurement of blood pressure.

Blood pressure (BP) was measured by radiofrequency transmitters implanted in the abdominal aorta (TA11PA-C40; Transoma Medical, St. Paul, MN) under isoflurane anesthesia, as we previously described (15). Mean arterial pressure (MAP) was obtained during 10-s sampling periods every 5 min and are expressed as 24-h averages. Rats were allowed to recover from telemeter implantation for 14 days before BP measurement.

Experiment 2

Another four groups of female SHRs were treated with molsidomine (30 mg·kg−1·day−1 in tap water), l-NAME (4.5 mg·kg−1·day−1 in tap water), molsidomine + l-NAME or tap water (control) (n = 4 or 5/group) for 1 wk. At the end of the study, kidneys were removed for measurement of ROS by lucigenin chemiluminescence and for analyses of antioxidant protein expression by Western blot.

Measurement of superoxide in kidney homogenates by lucigenin luminescence.

In isoflurane-anesthetized rats, kidneys were perfused clear of blood with saline containing 2% heparin. Kidneys were removed and separated into cortex and medulla and homogenized (1:8 wt/vol) in RIPA buffer (PBS, 1% Nonidet P-40 or Igepal CA-630, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS, and a cocktail of protease inhibitors; Sigma Chemical, St. Louis, MO) with a Polytron (model PT10–35). The samples were centrifuged at 12,000 g for 20 min at 4°C. The supernatant was used for measurement of superoxide with lucigenin at a final concentration of 5 μM. The samples were allowed to equilibrate for 3 min in the dark, and basal luminescence was measured every second for 5 min with a luminometer (1). Luminescence was recorded as relative light units (RLU) per 5 min. NADPH-stimulated luminescence was determined in a similar manner after the addition of NADPH (100 μM; Sigma). An assay blank with no homogenate but containing lucigenin was subtracted from the reading before transformation of the data. Protein concentrations in the kidney homogenates were determined by the method of Lowry et al. (8). The data are expressed as RLU per milligram protein.

Western blot analyses of Cu,Zn-SOD, glutathione peroxidase, and catalase.

Following perfusion of kidneys and homogenization, as described above, proteins from kidney cortex homogenates (5–25 μg) from each group of rats were separated by SDS-PAGE, and electrophoretically transferred onto polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes, as we previously described (4). PVDF membranes were probed with sheep anti-Cu,Zn-SOD (1:4,000), anti-glutathione (1:2,000) peroxidase, or anti-catalase (1:2,000) antibodies (BioDesign, Saco, ME) and detected with rabbit anti-sheep secondary antibodies (1:16,000). Cu,Zn-SOD antibody reacts with both intracellular and extracellular enzymes. Thus, we, in fact, measured total Cu,Zn-SOD protein expression in cortical homogenates. Bands were detected by ECL Plus (Amersham, Piscataway, NJ) and quantified by densitometry. Membranes were stripped and reprobed with anti-GAPDH antibody (American Research Products, Palos Verdes, CA) as a loading control. All samples from each group were run in the same blots to evaluate the relative differences in expression of the enzymes between the different groups and to evaluate the effect of molsidomine or l-NAME on the expression of the enzymes.

Statistics.

Data are presented as control, molsidomine alone, l-NAME alone, and molsidomine + l-NAME and compared among the groups. Data are expressed as means ± SE. Comparisons among groups were made by one-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni post test.

RESULTS

Experiment 1

Effect of molsidomine and l-NAME on NOx and oxidative stress as determined by excretion of F2-isoprostane.

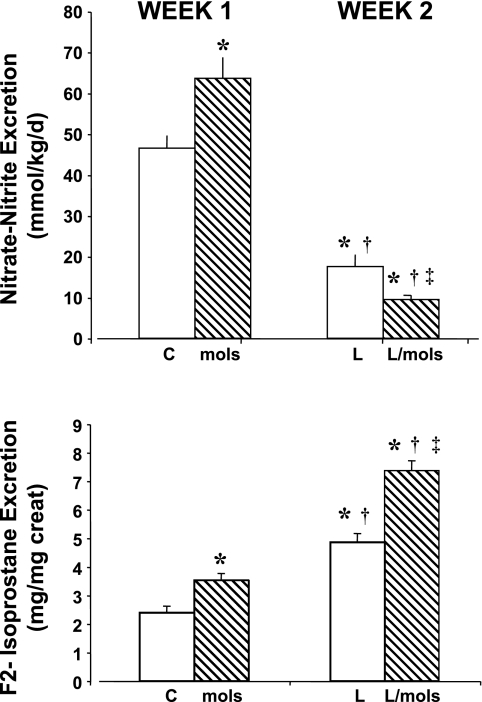

During the 1st wk of the study, group 1 rats remained untreated (controls) and group 2 rats received molsidomine. At the end of the 1st wk, treatment with molsidomine increased excretion of NOx (Fig. 1A) and F2-isoprostanes (Fig. 1B) compared with untreated rats. During the 2nd wk of the protocol, the control group (group 1) was given l-NAME, and group 2 rats were treated with molsidomine + l-NAME. By the end of the 2nd wk, l-NAME alone reduced NOx (Fig. 1A) but further increased excretion of F2-isoprostane (Fig. 1B). The combination of molsidomine + l-NAME in group 2 rats further reduced NOx and further increased F2-isoprostane excretion.

Fig. 1.

Effect of molsidomine and/or nitro-l-arginine methyl ester (l-NAME) on urinary excretion of nitrate/nitrite (A) and F2-isoprostanes (B) in Experiment 1. Rats were given molsidomine or vehicle for 1 wk, then both groups received l-NAME. Urine collections were made at the end of week 1 and week 2. C, control rats; mols, molsidomine-treated rats; L, l-NAME-treated rats; l-mols, l-NAME + molsidomine-treated rats. *P < 0.05 compared with controls; †P < 0.05 compared with molsidomine alone; ‡P < 0.05, compared with l-NAME alone.

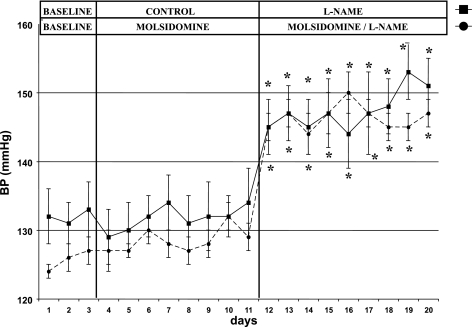

Effects of molsidomine and l-NAME on MAP in SHR.

During the 1st wk of the protocol, the administration of molsidomine to group 2 rats had no effect on MAP, compared with untreated group 1 rats (see Fig. 2). During the 2nd wk of the protocol, l-NAME alone increased MAP in group 1 rats, but the combination of molsidomine + l-NAME caused no further increase in MAP than l-NAME alone.

Fig. 2.

Effect of molsidomine and/or l-NAME on blood pressure in female SHR. (Experiment 1) MAP was measured by telemetry in female SHR for three days as a baseline. Rats were then left untreated or given molsidomine for one wk. All rats were then treated with l-NAME for another week. *, P < 0.05 compared with controls or molsidomine alone.

Experiment 2

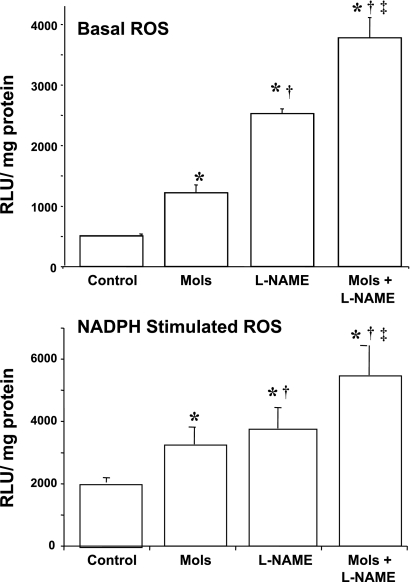

Effects of molsidomine and l-NAME on renal oxidative stress production.

As an additional index of oxidative stress, lucigenin chemiluminescence was measured in kidney cortex of rats given molsidomine alone, l-NAME alone, the combination of molsidomine + l-NAME or left untreated for 1 wk (see Fig. 3A). Molsidomine alone increased basal ROS by 50% compared with untreated rats. l-NAME alone increased basal ROS production by 5-fold compared with untreated rats and by 2-fold compared with molsidomine-treated rats. The combination of molsidomine + l-NAME increased basal ROS production by three-fold compared with molsidomine alone and by 1.5-fold compared with l-NAME alone. Molsidomine and l-NAME alone increased NADPH-stimulated ROS production by 1.6-fold and 1.9-fold, respectively (Fig. 3B), whereas the combination of molsidomine and l-NAME increased NADPH-stimulated ROS production by 2.7-fold compared with controls.

Fig. 3.

Effect of molsidomine and/or l-NAME on basal (Panel A) or NADPH-stimulated (Panel B) reactive oxygen species in female SHR (Experiment 2). Kidneys from rats left untreated or treated with molsidomine, l-NAME or the combination of molsidomine and l-NAME for one wk were homogenized and lucigenin chemiluminescence, an indicator of ROS, was measured as described in Methods. *, P < 0.05 compared with controls; †, P < 0.05 compared with molsidomine alone; ‡, P < 0.05 compared with l-NAME alone.

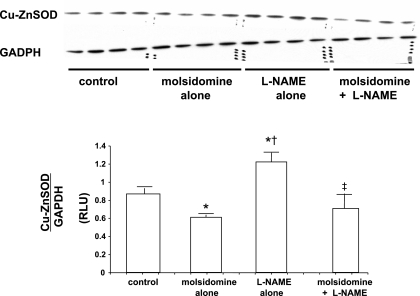

Effects of molsidomine and l-NAME on renal expression of antioxidant enzymes.

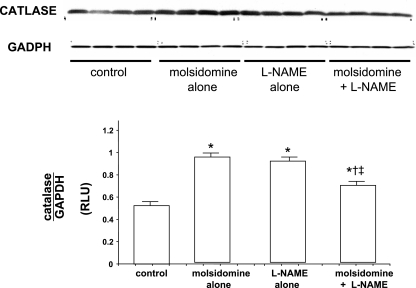

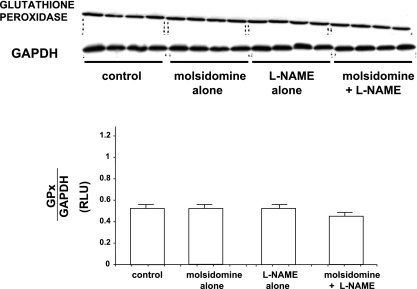

Expression of Cu-Zn SOD, catalase, and glutathione peroxidase in kidney tissue was measured by Western blot analyses. The expression of Cu-Zn SOD was downregulated by molsidomine alone but upregulated with l-NAME compared with control (see Fig. 4). However, in kidneys from rats given the combination of molsidomine and l-NAME, Cu,Zn-SOD expression was not different than in rats treated with molsidomine alone, but was lower than in rats treated with l-NAME alone. Catalase expression was increased to the same levels with both molsidomine and l-NAME alone but was reduced with the combination of molsidomine + l-NAME (see Fig. 5). Renal glutathione peroxidase expression was unaffected by either molsidomine or l-NAME alone or the combination of the two (see Fig. 6).

Fig. 4.

Effect of molsidomine and/or l-NAME on renal Cu,Zn-SOD protein expression in female SHR. (Experiment 2) Kidneys from rats left untreated or treated with molsidomine, l-NAME or the combination of molsidomine and l-NAME for one wk were homogenized and subjected to western blot. GAPDH was used a loading control. *, P < 0.05 compared with controls; †, P < 0.05 compared with molsidomine alone; ‡, P < 0.05 compared with l-NAME alone.

Fig. 5.

Effect of molsidomine and/or l-NAME on renal catalase protein expression in female SHR. (Experiment 2) Kidneys from rats left untreated or treated with molsidomine, l-NAME or the combination of molsidomine and l-NAME for one wk were homogenized and subjected to western blot. GAPDH was used a loading control. *, P < 0.05 compared with controls; †, P < 0.05 compared with molsidomine alone; ‡, P < 0.05 compared with l-NAME alone.

Fig. 6.

Effect of molsidomine and/or l-NAME on renal glutathione peroxidase protein expression in female SHR. (experiment 2) Kidneys from rats left untreated or treated with molsidomine, l-NAME or the combination of molsidomine and l-NAME for one wk were homogenized and subjected to western blot. GAPDH was used a loading control.

DISCUSSION

In the present study, we tested the hypothesis that the lack of a pressor response to increased oxidative stress in female SHR was due to increased NO and/or to upregulation of antioxidant enzymes, particularly catalase and glutathione peroxidase, as found in WKY males that also had no pressor response to molsidomine. We found that while blockade of NO synthase increased oxidative stress and blood pressure in control female SHR, as expected, the combination of molsidomine and l-NAME did not further increase blood pressure in females treated with molsidomine. As found in male WKY, renal cortical catalase expression was increased with molsidomine in female SHR, but unlike WKY, glutathione peroxidase was unaffected by molsidomine.

In previous studies, we found that blood pressure in male SHR increases significantly with molsidomine (4). In male WKY, blood pressure decreased in response to molsidomine, which is both a superoxide and NO donor, despite similar increases in ROS, as measured by lucigenin chemiluminescence, and similar increases in NO, as measured by nitrate/nitrite excretion in WKY and SHR. We also found that male WKY upregulate expression of both renal antioxidants, catalase and glutathione peroxidase, whereas male SHR did not. We assumed from these data that the increased expression of antioxidant enzymes, and, presumably, activity, in response to molsidomine, will lead to buffering of actual oxidative stress and subsequent increases in absolute NO levels in male WKY and thus to decreases in their blood pressure. We also assumed that since male SHR did not exhibit increases in antioxidant enzyme expression in response to molsidomine, their blood pressure increased as a result.

Our present data show that molsidomine indeed increases oxidative stress in female SHR, as measured by both lucigenin chemiluminescence and by urinary excretion of F2-isoprostanes. Furthermore, the combination of l-NAME and molsidomine further increased oxidative stress, yet blood pressure was not different compared with l-NAME alone. Thus, increased oxidative stress does not increase blood pressure in female SHR, contrary to male SHR. The data also show that the sex difference in the blood pressure response to increased oxidative stress is likely not mediated by upregulation of cortical antioxidant enzymes since protein levels of antioxidant enzymes were not consistently increased in female SHR (as found previously in male WKY, but not male SHR). In the present studies we evaluated only the cortical expression of antioxidant enzymes.

We have shown previously that cortical, but not medullary, NADPH oxidase-dependent oxidative stress mediates at least, in part, the hypertension in male SHR (7, 14). In our previous studies in male WKY, we found that antioxidant enzymes were upregulated in cortex in response to molsidomine. This did not occur in male SHR. Thus, we determined the effect of molsidomine on antioxidant enzyme expression in the cortex of female SHR to make certain that an upregulation was not the mechanism by which molsidomine failed to increase BP in females. Therefore, one caveat of this study is that we did not determine expression of antioxidant enzymes in the medulla of kidneys from females. It is always possible that there may have been changes in medullary enzymes that could have accounted for some of the lack of a pressor response to molsidomine in female SHR. We doubt that this was the case, however, since molsidomine alone and molsidomine + l-NAME significantly increased kidney oxidative stress, which argues against an increase in antioxidant activity (or expression) in response to molsidomine in cortex or medulla.

Our present results are consistent with our previous findings that treatment of female SHR with either tempol or apocynin fails to reduce their blood pressure (14). Taken together, the data suggest that oxidative stress plays little role in mediating the hypertension in female SHR. Thus there is a sex difference in the pressor response to oxidative stress in SHR. We have shown previously that the slow pressor response to ANG II infusion is also independent of oxidative stress in female Sprague Dawley rats (15). Consistent with our data, Chappell and colleagues failed to obtain reductions in blood pressure with tempol in female mREN2 rats (2). Taken together, these data point to the lack of a role for oxidative stress in controlling blood pressure in female rats regardless of whether the hypertension is experimental or genetic.

Another caveat of our present study is the use of molsidomine to increase oxidative stress since the drug is also an NO donor. However, we have shown previously that male WKY rats have a reduction in blood pressure in response to molsidomine (4). Nitrate/nitrite excretion was measured to verify that l-NAME reduced endogenous production of NO. Thus, the fact that rats that received molsidomine + l-NAME had even lower nitrate/nitrite excretion than l-NAME-treated rats, and there was no effect on blood pressure suggests that the molsidomine-derived NO also had no effect on blood pressure.

The question remains as to why there is a sex difference in blood pressure response to oxidants or antioxidants in SHR. One caveat is that the mechanism(s) by which blood pressure is affected by oxidative stress is still not completely understood 15 yr after the first studies showing an effect on blood pressure of antioxidants in male animals. Our data suggest that in females an increase in oxidative stress is not consistently buffered by kidneys of females, as evidenced by lack of a consistent upregulation of antioxidant enzymes. Perhaps there are differences in other tissues known to be affected by oxidative stress, such as the brain or the vasculature. We have shown previously that there is no sex difference in the pressor response to renal denervation (6), which suggests that sympathetic activation is not different between male and female SHR. These data do not support a difference in sympathetic activity that could be responsible for the sex difference in blood pressure response to either an increase or a decrease of oxidative stress in SHR. Future studies will be necessary to determine why oxidative stress modulates oxidative stress in male SHR, but not females.

In conclusion, in the present study, endogenous NO plays no role in mediating the lack of a pressor response to molsidomine in female SHR. Furthermore, changes in renal cortical antioxidant enzyme expression also do not explain the protection from blood pressure increase in molsidomine-treated female SHR. The data suggest that blood pressure in female SHR is independent of oxidative stress. These data support a sex difference in blood pressure regulation in SHR since blood pressure in male SHR is reduced in response to antioxidants and is increased in response to the prooxidant, molsidomine. The precise mechanism for the sex difference in the pressor response to oxidative stress in SHR remains to be determined.

Perspectives and Significance

Studies in hypertensive humans have not shown positive responses to antioxidant therapy (3, 9). The reasons for the lack of an antihypertensive response are not clear. However, it is likely due, in part, to the design of the studies; for example, in the HOPE trial, the study participants were already taking antihypertensive medications when given antioxidants (9). In addition, most of the study participants had been chronically hypertensive and thus likely had endothelial dysfunction (and thus low NO levels). We have shown previously that in the absence of a competent NO system, despite the reduction in oxidative stress with antioxidants, antioxidants are unable to reduce blood pressure (18). Our present studies suggest another reason why the antioxidant trials in hypertensive subjects may have been unsuccessful. Few of the trials with antioxidants were designed to analyze data from women and men separately. Thus, it's possible that women may have had no response to antioxidants because their hypertension was not mediated by oxidative stress, whereas men's hypertension was. These sex differences could not have been identified in the trials. Thus future studies are needed to evaluate the role that oxidative stress plays in blood pressure control in women and men independently.

GRANTS

This work was supported by HL51971, HL69194, and HL66072 (to J. F. Reckelhoff) from the National Institutes of Health. R Iliescu is the recipient of an American Heart Association Scientist Development Grant (0830416N).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest are declared by the authors.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to thank Huimin Zhang for excellent technical support.

REFERENCES

- 1.Berthold H, Munter K, Just A, Kirchheim H, Ehmke H. Stimulation of the renin-angiotensin system by endothelin blockade in conscious dogs. Hypertension 33: 1420–1424, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chappell M, Westwood B, Yamaleyeva L. Differential effects of sex steroids in young and aged female mREN2. Lewis rats: A model of estrogen and salt-sensitive hypertension. Gender Med 5Suppl A: S65–S75, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Czernichow S, Bertrais S, Blacher J, Galan p Briancon S, Favier A, Safar M, Hercberg S. Effect of supplementation with antioxidants upon long-term risk of hypertension in the SU. VI MAX study: association with plasma antioxidant levels. J Hypertens 23: 2013–2018, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fortepiani LA, Reckelhoff JF. Increasing oxidative stress with molsidomine increases blood pressure in SHR, but not WKY. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 289: R763–R770, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fortepiani LA, Reckelhoff JF. Tempol from birth abrogates the sex difference in the depressor response to tempol in SHR. J Hypertens 23: 801–805, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Iliescu R, Yanes LL, Bell W, Dwyer T, Baltatu O, Reckelhoff JF. Role of the renal nerves in control of blood pressure in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 290: R341–R344, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Iliescu R, Cucchiarelli V, Yanes L, Iles J, Reckelhoff J. Impact of androgen-induced oxidative stress on blood pressure in male SHR. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 292: R731–R735, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lowry OH, Rosebrough NJ, Farr AL, Randall RJ. Protein measurement with the Folin phenol reagent. J Biol Chem 193: 265–275, 1951 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McQueen M, Lonn E, Gerstein H, Bosch J, Yusuf S. The HOPE (Heart Outcomes Prevention Evaluation) study and its consequences. Scand J Clin Lab Invest Suppl 240: 143–156, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pawlowska D, Granger J, Knox F. Effects of adenosine infusion into the renal interstitium on renal hemodynamics. Am J Physiol Renal Fluid Electrolyte Physiol 252: F678–F682, 1987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rajagopalan K, Kurz S, Munzel T, Tarpey M, Freeman B, Griendling K, Harrison D. Angiotensin II-mediated hypertension in the rat increases vascular superoxide production via membrane NADH/NADPH oxidase activation. Contribution to alterations of vasomotor tone. J Clin Invest 97: 1916–1923, 1996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Reckelhoff J, Zhang H, Srivastava K. Gender differences in the development of hypertension in SHR: Role of the renin-angiotensin system. Hypertension 35: 480–483, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reckelhoff JF, Kellum J. Changes in nitric oxide precursor, l-arginine, and metabolites, nitrate and nitrite, with aging. Life Sci 55: 1895–1902, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sartori-Valinotti J, Iliescu R, Fortepiani L, Yanes L, Reckelhoff J. Sex differences in oxidative stress and the impact on blood pressure control and cardiovascular disease. Clin Exp Pharm Physiol 34: 938–945, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sartori-Valinotti J, Iliescu R, Yanes L, Dorsett-Martin W, Reckelhoff J. Sex differences in angiotensin II-induced hypertension: impact of high sodium intake. Hypertension 51: 1170–1176, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schnackenberg C, Wilcox CS. Two-week administration of tempol attenuates both hypertension and renal excretion of 8-isoprostaglandin F2α. Hypertension 33: 424–428, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wilcox CS. Reactive oxygen species : roles in blood pressure and kidney function. Curr Hypertens Rep 4: 160–166, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yanes L, Romero D, Iliescu R, Cucchiarelli V, Fortepiani L, Santacruz F, Bell W, Zhang H, Reckelhoff J. Systemic arterial pressure response to two weeks of Tempol therapy in SHR: involvement of NO, the RAS, and oxidative stress. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 288: R229–R233, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]