Abstract

The key step in NF-κB activation is the release of the NF-κB dimers from their inhibitory proteins, achieved via proteolysis of the IκBs. This irreversible signaling step constitutes a commitment to transcriptional activation. The signal is eventually terminated through nuclear expulsion of NF-κB, the outcome of a negative feedback loop based on IκBα transcription, synthesis, and IκBα-dependent nuclear export of NF-κB (Karin and Ben-Neriah 2000). Here, we review the process of signal-induced IκB ubiquitination and degradation by comparing the degradation of several IκBs and discussing the characteristics of IκBs’ ubiquitin machinery.

Ubiquitin-dependent degradation of IκB activates NF-κB. A single E3 ubiquitin ligase, β-TrCP, targets several IκB proteins for degradation.

Retrospectively, one of the most remarkable milestones in NF-κB research was the identification of its cytoplasmic inhibitor IκB (Inhibitor of NF-κB), soon after the discovery of the DNA binding activity of the factor (Sen and Baltimore 1986a; Sen and Baltimore 1986b; Baeuerle and Baltimore 1988). It immediately focused the research of NF-κB activation on the mechanism of liberation of the factor from the inhibitory effects of IκB. Using a simple detergent treatment of cell extracts, Baeuerle and Baltimore provided the first proof-of-concept for a model entailing the dissociation of the inhibitor as a major step in NF-κB activation (Baeuerle and Baltimore 1988). Subsequent experiments in cell lines suggested that stimulus-induced IκB phosphorylation triggered release of associated NF-κB, which could account for physiological activation of NF-κB (Ghosh and Baltimore 1990). Yet, later experiments showed that IκB phosphorylation was insufficient for NF-κB activation (Alkalay et al. 1995a; DiDonato et al. 1995), and IκB degradation must precede NF-κB activation (Beg et al. 1993; Brown et al. 1993; Mellits et al. 1993; Sun et al. 1993). Baeuerle and colleagues showed that blockade of IκB degradation prevented NF-κB activation (Henkel et al. 1993), but elucidation of the mechanism of IκB proteolysis awaited further studies by Maniatis, Goldberg, Ben-Neriah, Ciechanover, and colleagues who showed that signal-induced ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation of IκB were required for NF-κB activation (Palombella et al. 1994; Alkalay et al. 1995b; Chen et al. 1995). These findings implicated for the first time ubiquitin-dependent proteolysis as an integral step of signal induced transcriptional activation, yet the specificity basis for IκB degradation remained to be shown. Sequence homology comparisons and site-directed mutagenesis revealed a conserved amino-terminal sequence containing two serine residues that were found to be phosphorylated after phorbol ester stimulation and are necessary for signal-induced IκBα ubiquitination and degradation by the proteasome (Brown et al. 1995; Chen et al. 1995). This information was critical for the subsequent molecular characterization of both the IκB kinase and ubiquitin ligase (E3). Using a set of specific phosphopeptides, Yaron et al. showed that the phosphorylation-based motif (DpSGXXpS) of IκBα is sufficient for IκB recognition by components of the ubiquitin-system in vitro (Yaron et al. 1997). Subsequently, the specificity component of the E3, β-TrCP, was identified by mass spectroscopy as a protein that specifically interacts with the IκB phosphopeptide motif (Yaron et al. 1998). Significantly, a Drosophila homolog of β-TrCP, slimb, had previously been identified by Jiang and Struhl in a genetic screen as a likely E3 for β-catenin and cubitus interruptus (Ci) (Jiang and Struhl 1998). Several labs (Spencer et al. 1999; Tan et al. 1999; Winston et al. 1999) then showed that β-TrCP is the substrate binding (receptor) subunit of an SCF-type E3 ligase (Deshaies 1999). The structural basis for recognition of phospho-IκBα by the IκB E3 ligase was then established by Pavletich and his colleagues, who solved the crystal structure of the substrate interacting pocket of β-TrCP in complex with the β-catenin phosphopeptide (sharing with IκBα the destruction motif, i.e., degron) (Wu et al. 2003). β-TrCP was subsequently shown to control the proteasome-mediated degradation of other IκBs (IκBβ and IκBε) (Shirane et al. 1999; Wu and Ghosh 1999), and of NF-κB1/p105 (Orian et al. 2000; Heissmeyer et al. 2001; Lang et al. 2003), as well as the signal-induced processing of NF-κB2/p100 to p52 by the proteasome (Fong and Sun 2002).

THE IκB E3 UBIQUITIN LIGASE

The half-life of IκBα in resting cells is 138 min, two orders of magnitude longer than the half-life of IκBα in stimulated cells—1.5 min (Henkel et al. 1993). The signal that transforms the stable IκBα in resting cells to the fast degrading form in stimulated cells is the phosphorylation of residues 32 and 36 (Chen et al. 1995; Yaron et al. 1997). Rapid degradation of the phosphorylated IκBα demands an E3 with features allowing the speed, specificity, and inducibility that characterize IκBα degradation. An SCF-type E3 possesses the required characteristics: (1) It recognizes mainly phosphorylated substrates, allowing recognition only after signal induced phosphorylation of the substrate, and (2) it has a variable receptor subunit, the F-box protein, which recognizes a wide spectrum of different substrates, permitting the necessary specificity (Deshaies 1999). The SCF complex forms a bridge between the E2 ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme and the different substrates. This interaction increases the effective concentration of the target lysine residues near the active site of the E2, thus catalyzing the ubiquitination of the attached substrate (Wu et al. 2003). The SCF complex is composed of the adapter protein Skp1 (Feldman et al. 1997), the scaffold protein cullin-1 (Feldman et al. 1997), the RING domain protein Rbx1 (Roc or Hrt1) (Skowyra et al. 1999) (an E2 adapter), and a variable F-box protein (FBP), which allows the broad specificity (Skowyra et al. 1997). All the FBPs share a conserved 40-amino-acid domain called the F-box domain, which connects to the rest of the SCF complex through Skp1 (Bai et al. 1996). The substrate-binding domain of the FBP is almost invariably positioned directly carboxy-terminal to the F-box domain in the sequence, and no FBP has more than one F-box domain (Cardozo and Pagano 2004). The FBPs are classified according to their substrate-binding motif. The FBW family that includes β-TrCP, which recognize IκB, has a WD-40 repeats domain, structured as a β-propeller (Deshaies 1999). The WD-40 domain recognizes motifs containing phosphorylated Serines or Threonines, for example, the DpSGXXpS degron recognized by β-TrCP (Yaron et al. 1997; Smith et al. 1999). The FBL family has a Leucine-rich repeat in an arc-shaped α-β-repeat structure. A nonobligatory preference of substrate recognition by FBL is the prephosphorylation of the substrate or, at times, its attachment to other proteins in a complex (Kobe and Kajava 2001). Other FBPs are termed FBX and contain a variety of protein–protein interaction domains. It is very common for proteins in this family to recognize their substrates only following different post-translational modifications, such as glycosylation, hydroxylation, and others (Jaakkola et al. 2001; Yoshida et al. 2002; Yoshida et al. 2003). The three FBP families share the requirement for a substrate change before recognition, by either post-translational modification or binding of other proteins. This mode of regulation enables individual recognition of many substrates by the same FBP over different cellular conditions.

One of the best characterized FBPs is the FBW β-TrCP. This protein is located mainly in the nucleus (Davis et al. 2002), yet may show some activity also in the cytoplasm (Jiang and Struhl 1998). It binds an impressive list of phosphorylated substrates, including regulators of inflammation and cell fate (the IκBs), development and tissue organization (β-catenin, Snail), many cell cycle regulators (Emi1, Wee1), and DNA damage responders (Claspin, Cdc25A) (Jiang and Struhl 1998; Busino et al. 2003; Guardavaccaro et al. 2003; Watanabe et al. 2004; Zhou et al. 2004; Peschiaroli et al. 2006). In spite of β-TrCP’s pivotal contribution to many oncogenic cellular pathways, there are not many known cases of mutations in the β-TrCP gene in human malignancies. This might reflect the essential physiological role of this E3 or redundancy of the two β-TrCP paralogues encoded by two different genes. The two paralogues are identical in their biochemical qualities because the “pocket” responsible for substrate recognition is identical (Fuchs et al. 1999). The redundancy may explain to the mild testicular phenotype observed in the in vivo ablation of β-TrCP1 (Guardavaccaro et al. 2003). The two best characterized substrates of β-TrCP, β-catenin and IκB, do not accumulate in β-TrCP-deficient mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFβ-TrCP1−/−). The phenotype detected in the knockout mice might stem from differential regulation of the two paralogues: For instance, β-TrCP2 may not be expressed in all cells of the testes at which the knockout phenotype has been noticed. The best way to validate the differential contribution of the two paralogs in vivo is probably a combination of inducible deletion of β-TrCP2 and β-TrCP1, which is currently underway in some laboratories.

REGULATION OF β-TrCP

β-TrCP is responsible for the degradation of many proteins in response to various stimuli, among which are cell cycle regulators, some with opposing functions. Each substrate demands the attention of β-TrCP in a different temporal, spatial, and physiological context. Some of the substrates, such as the IκBs, must be degraded quickly following stimuli, whereas others, like β-catenin, are continuously ubiquitinated by β-TrCP and must be stabilized on a stimulus. Therefore, β-TrCP must be available at all times and the main mode of its functional regulation has to be the recognition and binding to the different substrates in the right context. This feature is provided by the signal dependent phosphorylation of all β-TrCP substrates (Deshaies 1999; Karin and Ben-Neriah 2000; Nakayama and Nakayama 2005). Any regulation of β-TrCP itself must therefore be bounded to these limitations. There is, however, only limited data concerning the transcriptional regulation of β-TrCP. It was reported that β-TrCP1 is regulated by the Wnt pathway at the mRNA level, both by modulation of the rate of transcription and the stabilization of mRNA (Spiegelman et al. 2000; Ballarino et al. 2004). β-TrCP1 mRNA stability is also increased following Jun amino-terminal kinase (Jnk) activation in a transcription-independent manner (Spiegelman et al. 2002). The transcriptional regulation of β-TrCP2, however, is probably different, with Wnt stimulus leading to its transcriptional inhibition and mitogen-activated signaling resulting in a β-TrCP2 transcriptional increase (Spiegelman et al. 2002). There still remains the question of the physiological relevance of these controls modes, as unless the isoforms have different substrate specificity, opposing transcriptional regulation of the two may offset each other.

Taking into account the entire SCF complex as one functional E3 unit, it is difficult to predict the impact of the change in the level of one subunit on E3 function. A comparison between two transgenic mice, one overexpressing the WT β-TrCP1 and the other expressing a dominant negative mutant of β-TrCP1, exemplifies the problematics of up-regulation of the β-TrCP subunit by itself. The dominant negative mutant that lacks the F-box is unable to assemble an SCF complex, but rather sequesters β-TrCP substrates and hinders their recognition by WT β-TrCP. Yet, surprisingly, overexpression of WT β-TrCP caused the same degree of β-catenin accumulation and tumorigenesis rate (Belaidouni et al. 2005). Therefore, when WT β-TrCP is expressed in excess, the stoichiometry of the other components in the SCF complex is inadequate, resulting in the apparent dominant-negative function of WT β-TrCP transgene. The need for balanced expression of the SCF subunits likely rebuts the notion of modulating β-TrCP expression levels as a major mode of regulation of the E3 activity.

Acting as a part of the SCF complex, β-TrCP activity is also subject to regulation directed at other components of the complex. The Nedd8 ubiquitin-like molecule was found to regulate the assembly of the SCF complex (Wei and Deng 2003; Wolf et al. 2003). Nedd8 modification of Cul1 stabilizes the SCF complex by preventing the binding of Cand1. Cand1 binds to cullin-Rbx1 complex and occludes Skp1, thereby preventing SCF assembly (Liu et al. 2002). Cleavage of Nedd8 by the COP9/signalosome (CSN) will allow the binding of Cand1 and decrease the SCF activity (Lyapina et al. 2001). Thus, complex assembly provides another level of E3 regulation, preventing spurious activity of the E3 complex.

Another case of SCF regulation is evident in the interaction of β-TrCP with the abundant nuclear protein hnRNP-U, reminiscent of a pseudo-substrate control, as hnRNP-U binds to the E3 but is not ubiquitinated (Davis et al. 2002). This may affect β-TrCP by maintaining it in the nucleus and raising its substrate-binding threshold. Raising the recognition threshold is an effective tool to avoid degradation of low affinity substrates, for example, none-, or partially phosphorylated substrates. Examples of a low affinity substrate are IκBα molecules that are phosphorylated only at one of the two serines of the β-TrCP degron (Ser36 by IKKε, and Ser32 by Rsk1) (Ghoda et al. 1997; Schouten et al. 1997; Peters et al. 2000): These will not compete effectively with saturating levels of hnRNP-U and will therefore escape β-TrCP ubiquitination.

These examples probably represent only the tip of the iceberg, as the intricate SCF structure provides ample room for activity regulation through multiple intrinsic (e.g., subunit modification) and extrinsic (accessory molecules) factors, mostly yet to be discovered.

IκB RECOGNITION BY β-TrCP

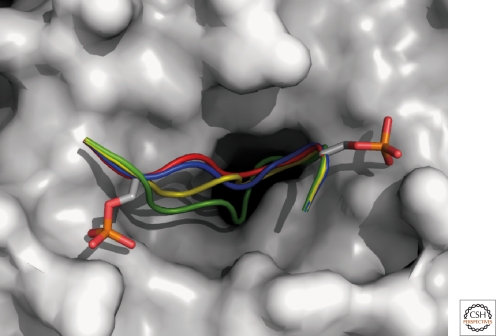

Rarely there is as detailed a mechanistic understanding of the E3-substrate interaction as with β-TrCP. This understanding emerged from peptide inhibition studies, defining the degron sequence and the necessity for dual phosphorylation for ubiquitination of phosphorylated IκBα (Yaron 1997). Yet a clearer interaction picture awaited the crystallography analysis of Pavletich and colleagues who pinpointed the critical features of substrate binding by β-TrCP (Wu 2003). This has been achieved by the cocrystallography of β-TrCP with a phosphorylated β-catenin peptide, sharing with IκB the core degron motif DpSGΦXpS (GΦX referred to as a “spacer,” Φ stands for a hydrophobic, and X is any residue). The following binding details are observed in the structure: Phosphopeptide binding is mediated by one face of the β-propeller, a structure created by the seven WD repeat domain of β-TrCP; other domains of the F-box protein in the WD vicinity (e.g., the F-box, the F-box-WD linker, and the dimerization domain) or other SCF components do not participate in substrate binding; a central groove running through the middle of the WD propeller structure accommodates the degron moiety of the substrate. Wu et al. noticed that all seven WD repeats of β-TrCP contribute contacts to the bound peptide. Nearly all of the β-TrCP contacts are made by the six-residue degron; the side chains of the Asp, the hydrophobic residue (Φ), the backbone of the Gly, and the spacer residues (X) insert the farthest into the groove, making intermolecular contacts in a mostly buried environment. The phosphate groups of the two serines bind sites at the rim of the groove and along with the Asp make the largest number of contacts with β-TrCP residues surrounding the groove through hydrogen bonds and electrostatic interactions. Whereas Pavletich’s data explains well the interaction of β-TrCP with IκBs and other canonical degron motif substrates, a remaining question is how the E3 can accommodate peptides containing atypical degrons, such as p105, which contains a longer spacer. To that end, we used the Rosetta software (Das and Baker 2008) to model a loop of varying length and sequence onto the scaffold of the two phosphorylated serine anchors of the β-catenin peptide bound to β-TrCP (Wu et al. 2003). A comparison of the structural models of phospho-peptides derived from β-catenin (DpSGIHpS), IκBα (DpSGLDpS), p105 (DpSGVETpS), and CDC25B (DpSGFCLDpS) suggests that these peptides of different spacer length can indeed all be accommodated into the groove (Fig. 1): Although the two phosphorylated serines are oriented similarly to those of β-catenin, the spacer between them—although of different length and sequence—displays similar characteristics. In all of the motifs, a glycine is followed by a hydrophobic residue (Ile, Leu, Val, and Phe) which is packed against a hydrophobic patch in the groove. The longer the binding motifs, the deeper into the groove will this hydrophobic residue be inserted. This advances our understanding of the principles that underlie substrate specificity, and in addition is invaluable for attempts to design β-TrCP blocking agents as NF-κB inhibitors (see the following discussion).

Figure 1.

Accommodation of peptide degrons of different lengths into the β-TrCP binding groove. The β-TrCP WD40 domain is shown in white surface representation from a top view (1P22:A); the two phosphorylated Serine residues that are conserved among all the peptides are shown in stick representation; and different peptide backbones are colored according to the peptide: The β-catenin peptide is shown in red (1P22:C); a model of the IκBα peptide (DSGLDS) is shown in blue; p105 peptide (DSGVETS) in yellow; and CDC25B peptide (DSGFCLDS) in green. Note that with increasing length of the spacer between the two phosphorylated serine residues, the hydrophobic part of the peptide binds deeper into the pocket.

DEGRADATION KINETICS OF THE DIFFERENT IκBs

The three IκBs (IκBα, IκBβ, and IκBε) are degraded with different kinetics, IκBα the fastest (approximately 15 min in Jurkat and THP-1cells) and IκBε the slowest (120 min in Jurkat cells) (Whiteside et al. 1997). It is hard to define the factor that influences mostly these kinetics, and there might be a variation of the limiting factor in different physiological contexts. The first candidate is the stimulus itself, but even when examining one of the most effective stimuli, TNFα, there is hardly any correlation between the applied dose and the kinetics of IKK phosphorylation activity or IκB degradation (Cheong et al. 2006). IKK itself can be the factor that distinguishes between the three IκBs. Mathematical models and experimental data indicated that NF-κB dynamics are sensitive to the timing and duration of the IKK activity (Cheong et al. 2008). Indeed, the affinity between IKK and the different IκBs correlates with their degradation rate, implicating IKK as the main factor that shapes the differential kinetics (Heilker et al. 1999).

Another factor that might influence the degradation kinetics is the ubiquitination rate. Because the three IκBs share the same DSG degron, it is not plausible that the recognition by β-TrCP is discriminative, but perhaps other domains in the IκB structure can influence the processivity of ubiquitination as with the different substrates of another E3 (Rape et al. 2006). The processivity of ubiquitination is influenced by the affinity to the E3 ligase and by the associated activity of deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs) (Rape et al. 2006). Deubiquitination is often a major means of terminating ubiquitination-dependent signaling response, and could also function in reducing the basal, signal-independent ubiquitination of several proteins in NF-κB signaling, including IκBs. CYLD and A20 are the two key DUBs in this regulation, but neither of them targets IκBs (Sun and Ley 2008). So far, no DUB has been found to negatively regulate the degradation of IκB, but considering equivalent signaling systems (e.g., the DNA damage response) (Zhang et al. 2006; Bassermann et al. 2008), it may exist, providing an important regulatory aspect to NF-κB signaling.

The unique degradation characteristics of the IκBs fit their nonredundant roles in the regulation of the NF-κB response. It is best exemplified in the computational model generated by Hoffmann et al. (2002). Using three mouse models in which each IκB was deleted separately, it was shown that IκBα is inimitable in inducing a rapid, strong negative feedback regulation, resulting in an oscillatory NF-κB activation profile. IκBβ, and particularly IκBε, respond more slowly to IKK activation and act to dampen the long-term oscillations of the NF-κB response. The interplay between these isoforms dictates the onset and termination of NF-κB activation, allowing a relatively stable NF-κB response during long-term stimulation. Consistent with the major role of IκBα, deletion of IκBβ and IκBε in animals is mostly harmless, indicating that other IκBs can compensate for their loss (Memet et al. 1999; Hoffmann et al. 2002). In contrast, deletion of IκBα resulted in constitutive NF-κB activation and embryonic lethality (Beg et al. 1995), yet, once IκBβ is expressed under the promoter of IκBα, it provided full compensation for the absence of IκBα (Cheng et al. 1998). This finding highlighted the importance of unique transcriptional regulation of IκBα rather than its unique activity or its own degradation rate, in controlling NF-κB activity.

In addition to their distinctive degradation kinetics, the three IκBs show different quantitative contribution to the NF-κB response. Unfortunately, a quantitative model based on the experimental data cited above failed to distinguish between the three IκBs (Cho et al. 2003). Thus, this aspect still awaits the formulation of a proper underlying model. In particular, the relative stoichiometry of association of each IκB with NF-κB is not known. Nevertheless, there is a negative correlation between the relative concentration of nuclear NF-κB and the overall cellular IκBα levels, indicating a major role of IκBα in controlling the NF-κB localization (Pogson et al. 2008). It will be interesting to study NF-κB localization with respect to the relative concentrations of the other IκBs, and thus incorporate further kinetic and quantitative aspects into a unified model of NF-κB activation.

UBIQUITINATION OF p100 AND p105 CONTROLS THEIR IκB FUNCTION

p100 and p105 also function as IκBs (Rice et al. 1992; Mercurio et al. 1993) but do not share the main features of a canonical degradation pathway. Their primary function is to serve as precursors for the mature NF-κB proteins p52 and p50, a function regulated by proteasomal processing (Fan and Maniatis 1991). Yet, the ankyrin repeat structure of p100 and p105 binds NF-κB/Rel proteins, similarly to the homologous region of the “professional IκBs” (α, β, and ε), and can therefore fulfill an IκB function, assuming that the fraction of NF-κB bound to these precursor proteins is sometimes free to dissociate, enter the nucleus, and induce transcriptional activity. In this respect, precursor processing regulates the NF-κB pathway in two planes: producing new and releasing old NF-κB molecules for the benefit of the transcriptional response. p100 is phosphorylated by IKKα that is recruited and activated by NF-κB-inducing kinase (NIK) as part of the noncanonical NF-κB signaling pathway (Xiao et al. 2001; Xiao et al. 2004). This phosphorylation promotes the binding of β-TrCP, polyubiquitination, and proteasomal processing, which generates active, IκB-free p52 (Fong and Sun 2002). In contrast, p105 is constitutively processed both in resting and stimulated cells (Weil et al. 1999; Orian et al. 2000), a course of action mediated by an independent, yet to be identified E3 that induces mono-ubiquitination rather than the polyubiquitination mediated by β-TrCP (Kravtsova-Ivantsiv et al. 2009). Still, the inhibitory function of p105 is compliant with canonical IKKβ phosphorylation, and p105 proteasomal processing, which is facilitated by signaling (Mercurio et al. 1993) reduces the inhibition (Heissmeyer et al. 1999). In addition, a fraction of p105 is targeted for complete degradation following certain cell stimuli, such as TNFα (Lang et al. 2003).

Overexpressed p105 was found to sequester c-rel and p65 in the cytoplasm of COS-7 and CV-1 cells (Rice et al. 1992). Endogenous p105 and p100 were shown to associate with c-rel and p65 in Jurkat cells (Mercurio et al. 1993) and in WT MEFs in vivo (Basak et al. 2007). Unfortunately, in these studies, the question of whether the binding of p100 or p105 is quantitatively significant has not been addressed and the stoichiometry of the NF-κB fraction that is bound to these proteins is unknown. The RelA fraction that is bound to p100 or p105 could vary from cell to cell and be subject to cell stimulation or other cellular conditions. Thus, its quantification might provide a better understanding of the IκB role played by the NF-κB precursors.

A study focusing on the noncanonical NF-κB signaling downstream to the LTβR provided evidence that p100 functions as an inhibitor in IκBα−/−, IκBβ−/−, and IκBε−/− MEFs (Basak et al. 2007). This work also showed that the fraction of p100-bound, dissociable p65 was increased three- to fourfold following TNFα stimulation, proposing a specific time window for IκB function of p100 after canonical signaling in WT cells. This suggestion was further supported by transcriptional synergism between LTβR and TNFα. However, some relevant questions were left unanswered: whether the overall stoichiometry of p100-bound NF-κB is significantly changed following canonical stimulation, and whether the transcriptional synergism between LTβR and TNFα stimuli brought as evidence for an IκB function of p100 could in fact be caused by IKK activation with LTβR (Chang et al. 2002).

An in vivo research of the inhibitory role of p100 and p105 is hard to conduct because most genetic manipulations will also influence p50 and p52 and thus, it will be hard to distinguish the IκB-relevant effects. One way around this point is to stabilize a precursor by way of site directed mutagenesis, which will spare processing. Indeed this was recently achieved in the case of p105 in T cells, showing that substitution of the modifiable serine residues controlling p105 stability resulted in a moderate “IκB super-repressor”-like molecule, affecting T-cell development (Sriskantharajah et al. 2009). However, again the stoichiometry of p105-bound NF-κB is nonphysiological, thus not necessarily attesting to a physiological IκB function of p105 in T cells. As a heterozygous mutation that substitutes human Ser32 of IκBα is sufficient to cause T-cell immunodeficiency and ectodermal dysplasia (Courtois et al. 2003; Janssen et al. 2004), it is possible that equivalent serine substituting mutations in the NFKB1 and NFKB2 genes will cause similar human pathologies, thereby supporting the IκB function of NF-κB precursor protein.

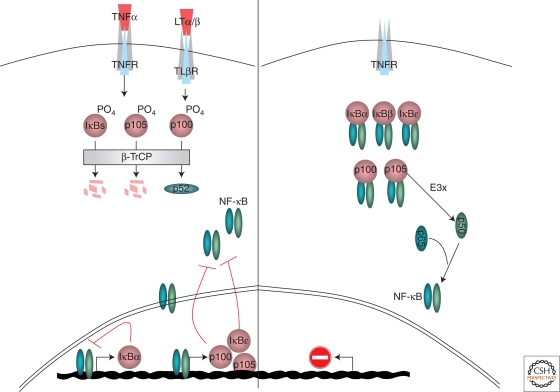

To conclude, better understanding of the true IκB role of p100 or p105 requires quantitative and kinetic studies, with comparison to the “professional” IκBs, preferentially under physiologic conditions (i.e., in WT cells in response to various stimuli) (see Fig. 2). This will probably be best achieved with the help of mathematical modeling. Only then may we understand the role of each IκB in physiological NF-κB response.

Figure 2.

Ubiquitin-mediated proteolysis at the central stage of the NF-κB. Many regulatory steps in the NF-κB pathway involve ubiquitin-regulated proteolysis. In resting cells (right panel), basal level processing of the NF-κB1 precursor p105 to p50, mediated by a yet unidentified E3(s) (E3x), is the major proteolytic event. The processing product p50 associates with p65 to generate the NF-κB heterodimer, maintained inactive in the cytosol through association with an inhibitor: one of the “professional IκBs” or an NF-κB precursor (both p105 and p100). On cell stimulation (left panel), TNFα and LTα/β signal-mediated degradation of the IκBs and processing NF-κB2 (p100) to the mature p52 subunit, respectively, are the key proteolytic steps. All these ubiquitin-proteolysis events are controlled by a single E3 ubiquitin ligase, β-TrCP. A prerequisite for β-TrCP-induced ubiquitination is phosphorylation of its target proteins, mediated by IKK (not shown). Following IκB degradation, NF-κB accumulates in the nucleus and is free to induce transcriptional activation. Another major feature of the NF-κB pathways is the negative feedback control (red lines) by which first the newly transcribed IκBα and then the NF-κB precursors function to shorten signal duration by inhibiting NF-κB-controlled transcription. Pairing IκBα transcription and resynthesis to its rapid degradation shapes an oscillatory NF-κB response, which might have a particular regulatory significance, yet to be discovered. IκBε transcription by NF-κB function to reduce the oscillatory magnitude of the response and stabilize it during longer stimulations.

SUBCELLULAR LOCATION OF IκB UBIQUITINATION AND DEGRADATION

A large missing piece in the NF-κB activation scheme is the site of IκBα ubiquitination and degradation. This issue is underscored by the discordant subcellular localization of the IκBs, both the “professionals” and the NF-κB precursors, which are mostly cytoplasmic, and the E3 β-TrCP, which is mostly nuclear. A major fraction of β-TrCP is sequestered in the nucleus by the pseudo-substrate hnRNP-U, and coimmunoprecipitation studies show that this hnRNP-U-β-TrCP complex is available for ubiquitinating IκBα on exchange of the low affinity hnRNP-U pseudosubstrate by the high affinity pIκBα (Davis et al. 2002). Apart from the β-TrCP, other components of the SCF, as well as the proteasome, are localized and active in the nucleus (Nakayama and Nakayama 2005; von Mikecz 2006). Nuclear proteasome substrates include the p53 inhibitor Mdm2, the CDK inhibitor Far1, and others (von Mikecz 2006). How can we therefore envision the interaction between a nuclear E3 and cytoplasmic substrates? One way is to assume that the location of the components is not stable, and at least one component, the substrate or the E3, may switch its subcellular location randomly or on demand. It was therefore interesting to note that IκBα-NF-κB complexes shuttle continuously between the cytoplasm and the nucleus of unstimulated cells. The shuttling is mediated by a nuclear export signal (NES), located near the amino terminus of IκBα, and a likely unmasked nuclear localization signal (NLS) of the p50 proteins (Malek et al. 2001). IκBβ, which lacks the NES, is probably more efficient in masking the NLS because IκBβ-NF-κB complexes are found exclusively in the cytoplasm (Huang and Miyamoto 2001). IκBα shuttling is apparently unperturbed as long as the NF-κB/IκBα complex is stable. Once IκBα is phosphorylated via activated IKK, it is recognized by β-TrCP and degraded, following which NF-κB is retained in the nucleus. Whereas phosphorylation of IκBα is thought to occur in the cytoplasm (Karin and Ben-Neriah 2000), the subcellular site of its ubiquitination and degradation is unknown.

It is important to note that although the IκBα/NF-κB shuttling is a reasonable solution for introducing a nuclear E3 to a cytoplasmic substrate, most of the relevant experiments have relied on LMB treatment as an inhibitor of IκBα nuclear export. Other influences of this drug that may affect NF-κB signaling have never been taken into account. Therefore, any activation model entailing steady state shuttling must be taken with a grain of salt.

THE ROLE OF THE IκBs IN TERMINATION OF NF-κB SIGNALING

Temporal accuracy is required for induction and for termination of NF-κB activity. One of the major factors that controls the lifetime of the NF-κB response is a negative feedback loop based on NF-κB-dependent IκB synthesis (Le Bail et al. 1993). Following a near-complete signal-induced degradation of IκB, the newly synthesized IκBα enters the nucleus and pulls NF-κB away from the chromatin and back to the cytoplasm (Arenzana-Seisdedos et al. 1995). This process should allow a sufficient period of NF-κB activity to induce relevant target genes and prevent the extension of the transcriptional activity beyond the necessary time, to avoid deleterious overactivation effects (Hoffmann et al. 2002). It has been argued that NF-κB modification is one of the key factors that prevents premature termination of the transcriptional activity. For instance, RelA acetylation could prohibit its interaction with IκB, whereas its deacetylation by HDAC3 increases its affinity to IκB, thus allowing the eviction of NF-κB from the chromatin by the newly synthesized IκBα. Indeed, a timely acetylation–deacetylation cycle was shown to contribute to signal maintenance for 45 min (Chen et al. 2001). Following TNFα stimulus, NF-κB is activated for approximately 45 min (Hoffmann et al. 2002), whereas IκBα is transcribed as early as 15 min and peaks within 1 h (Scott et al. 1993). However, IKK activity peaks after 15 min and is maintained for more than an hour (Cheong et al. 2006), a period during which all the newly synthesized IκBα could be immediately phosphorylated by IKK and subsequently degraded. How then can IκB exert its termination role in the presence of an active IKK?

One possibility is that both IKKα and IKKβ phosphorylate NF-κB-bound IκB more efficiently than free IκB (Zandi et al. 1998), explaining how the free IκB can accumulate in IKK-active cells. Nevertheless, a major fraction of the newly synthesized IκB appears phosphorylated (Werner et al. 2005), suggesting that phosphorylation would not be the rate-limiting step in the destruction of this newly synthesized molecule. Another possibility is reduced ubiquitination of the unbound IκB by β-TrCP. Unlike many SCF substrates, most lysine residues of IκB are not targeted for ubiquitination in vivo, nor in the bound state in vitro, and the only degradation-relevant residues are Lys 21 and 22 of IκBα (Scherer et al. 1995). Lys 21 is also the target residue for sumoylation, a modification that might antagonize proteolysis-marking ubiquitination of IκB and could spare the newly synthesized IκB if happening soon after synthesis. However, sumoylation was shown to happen only in the nucleus (Rodriguez et al. 2001), which similarly to, or in parallel with RelA acetylation, might imply a role in terminating the NF-κB response, merely by stabilizing nuclear IκBα. Overexpressed Sumo-1 blocked TNFα and IL-1 dependent ubiquitination and degradation of IκBα in COS7 cells (Franzoso et al. 1992), yet S32/36 phosphorylated IκBα was resistant to sumoylation in vitro, possibly indicating the relevance of this modification only for the newly synthesized, nonphosphorylated IκB.

One should bear in mind that an unbound IκB could also be targeted by E3s other than β-TrCP, which do not require IKK phosphorylation (Yaron et al. 1997; O’Dea et al. 2008) and might be degraded as efficiently as phosphorylated IκB (O’Dea et al. 2008). IκBα can also be phosphorylated independently of a signal on its carboxyl terminus by the kinase CK2 (Barroga et al. 1995) or in response to a noncanonical stimulus, such as UV (Kato et al. 2003). Knockdown of the CK2β subunit or mutation of the phosphorylated residues in the carboxy-terminal fragment of IκBα abrogated the NF-κB response following UV (Kato et al. 2003). In addition, in response to doxorubicin-induced DNA damage, IκBα undergoes proteasomal degradation, both in WT and in IKKα−/− and IKKβ−/− MEFs (Wu and Miyamoto 2007). If this is physiologically relevant, it basically means that we do not understand how the newly synthesized IκB, whether phosphorylated or not, escapes ubiquitination and degradation, and there must be a mechanism to seclude it from the ubiquitination machinery or reverse its ubiquitination effectively (i.e., by deubiquitination).

THERAPEUTIC IMPLICATIONS OF IκB DEGRADATION

Aberrant NF-κB regulation has been implicated in autoimmune diseases and in certain types of cancer. Given their central role of regulating NF-κB activation, the proteins involved in ubiquitination and degradation of the IκBs are attractive targets for drug development. The successful treatment of a major hematological malignancies using a proteasome inhibitor has validated the ubiquitin–proteasome system as therapeutic target (Rajkumar et al. 2005). Bortezomib (formerly known as PS-341), a boronic acid dipeptide that binds directly with and inhibits the proteasome enzymatic complex, has a significant therapeutic activity in the treatment of advanced multiple myeloma (MM) (Hideshima et al. 2002) and was approved for MM treatment by the FDA in 2003. MM is often characterized by NF-κB pathway mutations (Annunziata et al. 2007; Keats et al. 2007) and Bortezomib’s effects on cells are partly mediated through NF-κB inhibition (Russo et al. 2001; Hideshima et al. 2002), resulting in apoptosis, decreased angiogenic cytokine expression, and inhibition of tumor cell adhesion to stroma. However, continuous proteasomal inhibition is toxic and therefore, bortezomib cannot be administered more than twice weekly, with proteasome inhibition lasting approximately 24 h after each injection (Adams 2002). An alternative approach to inhibiting NF-κB is to block IκB ubiquitination. This would be expected to have less undesired side effects than global proteasome inhibition and may be particularly attractive for cancer therapy (Fuchs et al. 2004). Here, too, one could believe in blocking a class of relevant E3s, or targeting specifically β-TrCP. Recent studies indicate the feasibility of blocking SCF-type E3s through interference with their activation requiring cullin modification by the ubiquitin-like molecule Nedd8 (Soucy et al. 2009). A more specific strategy for NF-κB inhibition would be selective IκB stabilization. The validity of this approach has been established in numerous experiments, both in vitro and in vivo, using a dominant IκB “super-repressor,” which cannot be inducibly phosphorylated and ubiquitinated but maintains its NF-κB inhibitory capacity (Cusack et al. 2000; Lavon et al. 2000). For example, the expression of such an inhibitor in liver cells has been shown to halt tumor growth in a murine model of hepatitis-associated cancer in vivo (Pikarsky et al. 2004). A clinically relevant method for that purpose is to prevent IκB ubiquitination or to impair β-TrCP recruitment to IκB. Cell-penetrating IκB phosphopeptides have been used for this purpose in cell lines (Yaron et al. 1997), but their efficacy has yet to be shown in vivo. It might also be possible to develop small-molecule inhibitors that structurally mimic the ligase recognition motif or specifically inactivate SCFβ-TrCP (through allosteric inhibition or disassembly). One obvious drawback with targeting β-TrCP is the potential to affect SCFβ-TrCP targets other than IκBs (Spiegelman et al. 2002). A critical issue is likely to be whether SCFβ-TrCP is the only E3 that contributes to the degradation of any given substrate. One obvious concern is stabilization of β-catenin, an important factor in colorectal tumorigenesis and other cancer types (van Es et al. 2003). One possibility, however, is that whereas IκB degradation relies exclusively on β-TrCP (see Fig. 2), other substrates like β-catenin have alternative ubiquitination and degradation routes, operating on β-TrCP inhibition. Consistent with this hypothesis, a distinct E3 complex containing the Siah RING finger protein has been shown to recognize and promote the degradation of β-catenin independently of SCFβ-TrCP (Liu et al. 2001; Matsuzawa and Reed 2001). Future analysis of β-TrCP-deficient mice will air this issue, proving whether the NF-κB pathway is affected in these mice far more than other signaling pathways. Furthermore, even if the selective inhibition of IκB ubiquitination is a technically feasible goal, systemic inhibition of NF-κB is not without risk because of its crucial role in regulating immune responses (Caamano and Hunter 2002). This is a particularly important consideration when NF-κB blockade is considered in combination with standard chemotherapy, which itself compromises the immune system and exacerbates tissue damage (Lavon et al. 2000). Furthermore, NF-κB inhibition may in fact be a “double-edged sword,” as in the presence of a carcinogen, and perhaps even under chemotherapeutic poisoning, NF-κB inhibition may facilitate, rather than prevent, tumor development (Kamata et al. 2005).

CONCLUDING REMARKS

Inducible degradation of IκB has become a paradigm of targeting a regulatory protein by the ubiquitin proteasome system as a major step in the activation of a signaling pathway. A central feature of this process is the coupling of two protein modification events, substrate bi-phosphorylation by a dedicated kinase, IKK, and ubiquitination, based on recognition of the phosphorylated degron by the E3. However, NF-κB is regulated by five different inhibitory proteins (IκBα, β, and ε and the two IκB-like NF-κB precursors), each holding some portion of NF-κB in an inactive state. Therefore, maximal activation of the pathway requires simultaneous elimination of all five IκBs. This may be achieved on costimulation of both the canonical and alternative branches of the pathway, inducing degradation and processing of different IκBs, respectively. No wonder that the coordination of the degradation response relies on a similar, IKK-induced phospho-degron that is shared among all IκBs and on a single E3, β-TrCP, which evolved to fit the nuances of the degron in the different IκBs.

Despite of the major advances achieved in understanding ubiquitin-signaling processes of NF-κB activation, several key questions remain unanswered, for example: What is the relative role of each IκB in controlling NF-κB activation in response to different stimuli? How is the NF-κB-transcribed, newly synthesized IκB protected from degradation as long as IKK is still activated? Which parameters other than phosphorylation affect the rate of degradation and processing of the different IκB? Where in the cell are IκB ubiquitination and proteolysis taking place? How important is the regulation of the ubiquitin–proteasome machinery itself in NF-κB signaling? Is IκB ubiquitination also regulated by specific deubiquitination enzymes? Are there any specific proteasome adaptor molecules that ensure degradation of IκBs, while protecting associated NF-κB from proteolysis by the proteasome? How frequently are mutations in the IκBs or their destruction machinery encountered in human disease?

Considering these and other outstanding issues, the regulation and function of ubiquitination are likely to remain a major focus of research in the NF-κB field.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Relevant research in the authors’ laboratories was supported by the Israel Science Foundation, the RUBICON Network of Excellence of the European Commission (FP6), The German Israeli Foundation, and the Adelson Medical Research Foundation.

Footnotes

Editors: Louis M. Staudt and Michael Karin

Additional Perspectives on NF-κB available at www.cshperspectives.org

REFERENCES

- Adams J 2002. Proteasome inhibition: A novel approach to cancer therapy. Trends Mol Med 8:S49–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alkalay I, Yaron A, Hatzubai A, Jung S, Avraham A, Gerlitz O, Pashut-Lavon I, Ben-Neriah Y 1995a. In vivo stimulation of I κ B phosphorylation is not sufficient to activate NF-κ B. Mol Cell Biol 15:1294–1301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alkalay I, Yaron A, Hatzubai A, Orian A, Ciechanover A, Ben-Neriah Y 1995b. Stimulation-dependent I κ B α phosphorylation marks the NF-κB inhibitor for degradation via the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci 92:10599–10603 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Annunziata CM, Davis RE, Demchenko Y, Bellamy W, Gabrea A, Zhan F, Lenz G, Hanamura I, Wright G, Xiao W, et al. 2007. Frequent engagement of the classical and alternative NF-κB pathways by diverse genetic abnormalities in multiple myeloma. Cancer Cell 12:115–130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arenzana-Seisdedos F, Thompson J, Rodriguez MS, Bachelerie F, Thomas D, Hay RT 1995. Inducible nuclear expression of newly synthesized IκB α negatively regulates DNA-binding and transcriptional activities of NF-κ B. Mol Cell Biol 15:2689–2696 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baeuerle PA, Baltimore D 1988. Activation of DNA-binding activity in an apparently cytoplasmic precursor of the NF-κ B transcription factor. Cell 53:211–217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai C, Sen P, Hofmann K, Ma L, Goebl M, Harper JW, Elledge SJ 1996. SKP1 connects cell cycle regulators to the ubiquitin proteolysis machinery through a novel motif, the F-box. Cell 86:263–274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballarino M, Fruscalzo A, Marchioni M, Carnevali F 2004. Identification of positive and negative regulatory regions controlling expression of the Xenopus laevis βTrCP gene. Gene 336:275–285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barroga CF, Stevenson JK, Schwarz EM, Verma IM 1995. Constitutive phosphorylation of IκB α by casein kinase II. Proc Natl Acad Sci 92:7637–7641 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basak S, Kim H, Kearns JD, Tergaonkar V, O’Dea E, Werner SL, Benedict CA, Ware CF, Ghosh G, Verma IM et al. 2007. A fourth IκB protein within the NF-κB signaling module. Cell 128:369–381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bassermann F, Frescas D, Guardavaccaro D, Busino L, Peschiaroli A, Pagano M 2008. The Cdc14B-Cdh1-Plk1 axis controls the G2 DNA-damage-response checkpoint. Cell 134:256–267 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beg AA, Finco TS, Nantermet PV, Baldwin AS Jr 1993. Tumor necrosis factor and interleukin-1 lead to phosphorylation and loss of IκBα: A mechanism for NF-κ B activation. Mol Cell Biol 13:3301–3310 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beg AA, Sha WC, Bronson RT, Baltimore D 1995. Constitutive NF-κB activation, enhanced granulopoiesis, and neonatal lethality in IκB α-deficient mice. Genes Dev 9:2736–2746 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belaidouni N, Peuchmaur M, Perret C, Florentin A, Benarous R, Besnard-Guerin C 2005. Overexpression of human β-TrCP1 deleted of its F box induces tumorigenesis in transgenic mice. Oncogene 24:2271–2276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown K, Park S, Kanno T, Franzoso G, Siebenlist U 1993. Mutual regulation of the transcriptional activator NF-κ B and its inhibitor, IκBα. Proc Natl Acad Sci 90:2532–2536 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown K, Gerstberger S, Carlson L, Franzoso G, Siebenlist U 1995. Control of IκBα proteolysis by site-specific, signal-induced phosphorylation. Science 267:1485–1488 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busino L, Donzelli M, Chiesa M, Guardavaccaro D, Ganoth D, Dorrello NV, Hershko A, Pagano M, Draetta GF 2003. Degradation of Cdc25A by β-TrCP during S phase and in response to DNA damage. Nature 426:87–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caamano J, Hunter CA 2002. NF-κB family of transcription factors: Central regulators of innate and adaptive immune functions. Clin Microbiol Rev 15:414–429 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardozo T, Pagano M 2004. The SCF ubiquitin ligase: Insights into a molecular machine. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 5:739–751 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang YH, Hsieh SL, Chen MC, Lin WW 2002. Lymphotoxin β receptor induces interleukin 8 gene expression via NF-κB and AP-1 activation. Exp Cell Res 278:166–174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z, Hagler J, Palombella VJ, Melandri F, Scherer D, Ballard D, Maniatis T 1995. Signal-induced site-specific phosphorylation targets IκBα to the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. Genes Develop 9:1586–1597 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L, Fischle W, Verdin E, Greene WC 2001. Duration of nuclear NF-κB action regulated by reversible acetylation. Science 293:1653–1657 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng JD, Ryseck RP, Attar RM, Dambach D, Bravo R 1998. Functional redundancy of the nuclear factor κ B inhibitors IκBα and IκBβ. J Exp Med 188:1055–1062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheong R, Bergmann A, Werner SL, Regal J, Hoffmann A, Levchenko A 2006. Transient IκB kinase activity mediates temporal NF-κB dynamics in response to a wide range of tumor necrosis factor-α doses. J Biol Chem 281:2945–2950 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheong R, Hoffmann A, Levchenko A 2008. Understanding NF-κB signaling via mathematical modeling. Mol Syst Biol 4:192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho KH, Shin SY, Lee HW, Wolkenhauer O 2003. Investigations into the analysis and modeling of the TNFα-mediated NF-κB-signaling pathway. Genome Res 13:2413–2422 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Courtois G, Smahi A, Reichenbach J, Doffinger R, Cancrini C, Bonnet M, Puel A, Chable-Bessia C, Yamaoka S, Feinberg J, et al. 2003. A hypermorphic IκBα mutation is associated with autosomal dominant anhidrotic ectodermal dysplasia and T cell immunodeficiency. J Clin Invest 112:1108–1115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cusack JC Jr, Liu R, Baldwin AS Jr 2000. Inducible chemoresistance to 7-ethyl-10-[4-(1-piperidino)-1-piperidino]-carbonyloxycamptothe cin (CPT-11) in colorectal cancer cells and a xenograft model is overcome by inhibition of nuclear factor-κB activation. Cancer Res 60:2323–2330 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das R, Baker D 2008. Macromolecular modeling with rosetta. Annu Rev Biochem 77:363–382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis M, Hatzubai A, Andersen JS, Ben-Shushan E, Fisher GZ, Yaron A, Bauskin A, Mercurio F, Mann M, Ben-Neriah Y 2002. Pseudosubstrate regulation of the SCF(β-TrCP) ubiquitin ligase by hnRNP-U. Genes Develop 16:439–451 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deshaies RJ 1999. SCF and Cullin/Ring H2-based ubiquitin ligases. Ann Rev Cell Develop Biol 15:435–467 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiDonato JA, Mercurio F, Karin M 1995. Phosphorylation of IκBα precedes but is not sufficient for its dissociation from NF-κB. Mol Cell Biol 15:1302–1311 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan CM, Maniatis T 1991. Generation of p50 subunit of NF-κB by processing of p105 through an ATP-dependent pathway. Nature 354:395–398 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldman RM, Correll CC, Kaplan KB, Deshaies RJ 1997. A complex of Cdc4p, Skp1p, and Cdc53p/cullin catalyzes ubiquitination of the phosphorylated CDK inhibitor Sic1p. Cell 91:221–230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fong A, Sun SC 2002. Genetic evidence for the essential role of β-transducin repeat-containing protein in the inducible processing of NF-κB2/p100. J Biol Chem 277:22111–22114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franzoso G, Bours V, Park S, Tomita-Yamaguchi M, Kelly K, Siebenlist U 1992. The candidate oncoprotein Bcl-3 is an antagonist of p50/NF-κB-mediated inhibition. Nature 359:339–342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs SY, Chen A, Xiong Y, Pan ZQ, Ronai Z 1999. HOS, a human homolog of Slimb, forms an SCF complex with Skp1 and Cullin1 and targets the phosphorylation-dependent degradation of IκB and β-catenin. Oncogene 18:2039–2046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs SY, Spiegelman VS, Kumar KG 2004. The many faces of β-TrCP E3 ubiquitin ligases: Reflections in the magic mirror of cancer. Oncogene 23:2028–2036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghoda L, Lin X, Greene WC 1997. The 90-kDa ribosomal S6 kinase (pp90rsk) phosphorylates the N-terminal regulatory domain of IκBα and stimulates its degradation in vitro. J Biol Chem 272:21281–21288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh S, Baltimore D 1990. Activation in vitro of NF-κB by phosphorylation of its inhibitor IκB. Nature 344:678–682 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guardavaccaro D, Kudo Y, Boulaire J, Barchi M, Busino L, Donzelli M, Margottin-Goguet F, Jackson PK, Yamasaki L, Pagano M 2003. Control of meiotic and mitotic progression by the F box protein β-Trcp1 in vivo. Dev Cell 4:799–812 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heilker R, Freuler F, Vanek M, Pulfer R, Kobel T, Peter J, Zerwes HG, Hofstetter H, Eder J 1999. The kinetics of association and phosphorylation of IκB isoforms by IκB kinase 2 correlate with their cellular regulation in human endothelial cells. Biochemistry 38:6231–6238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heissmeyer V, Krappmann D, Hatada EN, Scheidereit C 2001. Shared pathways of IκB kinase-induced SCF(βTrCP)-mediated ubiquitination and degradation for the NF-κB precursor p105 and IκBα. Mol Cell Biol 21:1024–1035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heissmeyer V, Krappmann D, Wulczyn FG, Scheidereit C 1999. NF-κB p105 is a target of IκB kinases and controls signal induction of Bcl-3-p50 complexes. EMBO J 18:4766–4778 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henkel T, Machleidt T, Alkalay I, Kronke M, Ben-Neriah Y, Baeuerle PA 1993. Rapid proteolysis of IκBα is necessary for activation of transcription factor NF-κB. Nature 365:182–185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hideshima T, Chauhan D, Richardson P, Mitsiades C, Mitsiades N, Hayashi T, Munshi N, Dang L, Castro A, Palombella V, et al. 2002. NF-κB as a therapeutic target in multiple myeloma. J Biol Chem 277:16639–16647 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann A, Levchenko A, Scott ML, Baltimore D 2002. The IκB-NF-κB signaling module: Temporal control and selective gene activation. Science 298:1241–1245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang TT, Miyamoto S 2001. Postrepression activation of NF-κB requires the amino-terminal nuclear export signal specific to IκBα. Mol Cell Biol 21:4737–4747 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaakkola P, Mole DR, Tian YM, Wilson MI, Gielbert J, Gaskell SJ, Kriegsheim A, Hebestreit HF, Mukherji M, Schofield CJ, et al. 2001. Targeting of HIF-α to the von Hippel-Lindau ubiquitylation complex by O2-regulated prolyl hydroxylation. Science 292:468–472 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janssen R, van Wengen A, Hoeve MA, ten Dam M, van der Burg M, van Dongen J, van de Vosse E, van Tol M, Bredius R, Ottenhoff TH, et al. 2004. The same IκBα mutation in two related individuals leads to completely different clinical syndromes. J Exp Med 200:559–568 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang J, Struhl G 1998. Regulation of the Hedgehog and Wingless signalling pathways by the F-box/WD40-repeat protein Slimb. Nature 391:493–496 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamata H, Honda S, Maeda S, Chang L, Hirata H, Karin M 2005. Reactive oxygen species promote TNFα-induced death and sustained JNK activation by inhibiting MAP kinase phosphatases. Cell 120:649–661 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karin M, Ben-Neriah Y 2000. Phosphorylation meets ubiquitination: The control of NF-κB activity. Annu Rev Immunol 18:621–663 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato T Jr, Delhase M, Hoffmann A, Karin M 2003. CK2 Is a C-terminal IκB kinase responsible for NF-κB activation during the UV response. Mol Cell 12:829–839 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keats JJ, Fonseca R, Chesi M, Schop R, Baker A, Chng WJ, Van Wier S, Tiedemann R, Shi CX, Sebag M, et al. 2007. Promiscuous mutations activate the noncanonical NF-κB pathway in multiple myeloma. Cancer cell 12:131–144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobe B, Kajava AV 2001. The leucine-rich repeat as a protein recognition motif. Curr Opin Struct Biol 11:725–732 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kravtsova-Ivantsiv Y, Cohen S, Ciechanover A 2009. Modification by single ubiquitin moieties rather than polyubiquitination is sufficient for proteasomal processing of the p105 NF-κB precursor. Mol Cell 33:496–504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang V, Janzen J, Fischer GZ, Soneji Y, Beinke S, Salmeron A, Allen H, Hay RT, Ben-Neriah Y, Ley SC 2003. βrCP-mediated proteolysis of NF-κB1 p105 requires phosphorylation of p105 serines 927 and 932. Mol Cell Biol 23:402–413 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavon I, Goldberg I, Amit S, Landsman L, Jung S, Tsuberi BZ, Barshack I, Kopolovic J, Galun E, Bujard H, et al. 2000. High susceptibility to bacterial infection, but no liver dysfunction, in mice compromised for hepatocyte NF-κB activation. Nature medicine 6:573–577 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Bail O, Schmidt-Ullrich R, Israël A 1993. Promoter analysis of the gene encoding the I κ B-α/MAD3 inhibitor of NF-κB: Positive regulation by members of the rel/NF-κB family. EMBO J 12:5043–5049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J, Stevens J, Rote CA, Yost HJ, Hu Y, Neufeld KL, White RL, Matsunami N 2001. Siah-1 mediates a novel β-catenin degradation pathway linking p53 to the adenomatous polyposis coli protein. Mol Cell 7:927–936 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J, Furukawa M, Matsumoto T, Xiong Y 2002. NEDD8 modification of CUL1 dissociates p120(CAND1), an inhibitor of CUL1-SKP1 binding and SCF ligases. Mol Cell 10:1511–1518 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyapina S, Cope G, Shevchenko A, Serino G, Tsuge T, Zhou C, Wolf DA, Wei N, Shevchenko A, Deshaies RJ 2001. Promotion of NEDD-CUL1 conjugate cleavage by COP9 signalosome. Science 292:1382–1385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malek S, Chen Y, Huxford T, Ghosh G 2001. IκBβ, but not IκBα, functions as a classical cytoplasmic inhibitor of NF-κB dimers by masking both NF-κB nuclear localization sequences in resting cells. J Biol Chem 276:45225–45235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuzawa SI, Reed JC 2001. Siah-1, SIP, and Ebi collaborate in a novel pathway for β-catenin degradation linked to p53 responses. Mol Cell 7:915–926 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mellits KH, Hay RT, Goodbourn S 1993. Proteolytic degradation of MAD3 (I κ B α) and enhanced processing of the NF-κ B precursor p105 are obligatory steps in the activation of NF-κ B. Nucleic Acids Res 21:5059–5066 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Memet S, Laouini D, Epinat JC, Whiteside ST, Goudeau B, Philpott D, Kayal S, Sansonetti PJ, Berche P, Kanellopoulos J, et al. 1999. IκBε-deficient mice: Reduction of one T cell precursor subspecies and enhanced Ig isotype switching and cytokine synthesis. J Immunol 163:5994–6005 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mercurio F, DiDonato JA, Rosette C, Karin M 1993. p105 and p98 precursor proteins play an active role in NF-κ B-mediated signal transduction. Genes Dev 7:705–718 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakayama KI, Nakayama K 2005. Regulation of the cell cycle by SCF-type ubiquitin ligases. Semin Cell Dev Biol 16:323–333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Dea EL, Kearns JD, Hoffmann A 2008. UV as an amplifier rather than inducer of NF-κB activity. Mol Cell 30:632–641 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orian A, Gonen H, Bercovich B, Fajerman I, Eytan E, Israël A, Mercurio F, Iwai K, Schwartz AL, Ciechanover A 2000. SCF(β-TrCP) ubiquitin ligase-mediated processing of NF-κB p105 requires phosphorylation of its C-terminus by IκB kinase. Embo J 19:2580–2591 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palombella VJ, Rando OJ, Goldberg AL, Maniatis T 1994. The ubiquitin-proteasome pathway is required for processing the NF-κB1 precursor protein and the activation of NF-κ B. Cell 78:773–785 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peschiaroli A, Dorrello NV, Guardavaccaro D, Venere M, Halazonetis T, Sherman NE, Pagano M 2006. SCF(βTrCP)-mediated degradation of Claspin regulates recovery from the DNA replication checkpoint response. Mol Cell 23:319–329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters RT, Liao SM, Maniatis T 2000. IKKε is part of a novel PMA-inducible IκB kinase complex. Mol Cell 5:513–522 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pikarsky E, Porat RM, Stein I, Abramovitch R, Amit S, Kasem S, Gutkovich-Pyest E, Urieli-Shoval S, Galun E, Ben-Neriah Y 2004. NF-κB functions as a tumour promoter in inflammation-associated cancer. Nature 431:461–466 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pogson M, Holcombe M, Smallwood R, Qwarnstrom E 2008. Introducing spatial information into predictive NF-κB modelling–an agent-based approach. PLoS ONE 3:e2367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajkumar SV, Richardson PG, Hideshima T, Anderson KC 2005. Proteasome inhibition as a novel therapeutic target in human cancer. J Clin Oncol 23:630–639 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rape M, Reddy SK, Kirschner MW 2006. The processivity of multiubiquitination by the APC determines the order of substrate degradation. Cell 124:89–103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice NR, MacKichan ML, Israël A 1992. The precursor of NF-κ B p50 has IκB-like functions. Cell 71:243–253 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez MS, Dargemont C, Hay RT 2001. SUMO-1 conjugation in vivo requires both a consensus modification motif and nuclear targeting. J Biol Chem 276:12654–12659 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russo SM, Tepper JE, Baldwin AS Jr, Liu R, Adams J, Elliott P, Cusack JC Jr 2001. Enhancement of radiosensitivity by proteasome inhibition: Implications for a role of NF-κB. Int J Rad Oncol, Biol, Phys 50:183–193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scherer DC, Brockman JA, Chen Z, Maniatis T, Ballard DW 1995. Signal-induced degradation of IκB α requires site-specific ubiquitination. Proc Natl Acad Sci 92:11259–11263 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schouten GJ, Vertegaal AC, Whiteside ST, Israël A, Toebes M, Dorsman JC, van der Eb AJ, Zantema A 1997. IκB α is a target for the mitogen-activated 90 kDa ribosomal S6 kinase. EMBO J 16:3133–3144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott ML, Fujita T, Liou HC, Nolan GP, Baltimore D 1993. The p65 subunit of NF-κB regulates IκB by two distinct mechanisms. Genes Dev 7:1266–1276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sen R, Baltimore D 1986a. Inducibility of κ immunoglobulin enhancer-binding protein Nf-κ B by a posttranslational mechanism. Cell 47:921–928 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sen R, Baltimore D 1986b. Multiple nuclear factors interact with the immunoglobulin enhancer sequences. Cell 46:705–716 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirane M, Hatakeyama S, Hattori K, Nakayama K 1999. Common pathway for the ubiquitination of IκBα, IκBβ, and IκBε mediated by the F-box protein FWD1. J Biol Chem 274:28169–28174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skowyra D, Craig KL, Tyers M, Elledge SJ, Harper JW 1997. F-box proteins are receptors that recruit phosphorylated substrates to the SCF ubiquitin-ligase complex. Cell 91:209–219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skowyra D, Koepp DM, Kamura T, Conrad MN, Conaway RC, Conaway JW, Elledge SJ, Harper JW 1999. Reconstitution of G1 cyclin ubiquitination with complexes containing SCFGrr1 and Rbx1. Science 284:662–665 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith TF, Gaitatzes C, Saxena K, Neer EJ 1999. The WD repeat: A common architecture for diverse functions. Trends Biochem Sci 24:181–185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soucy TA, Smith PG, Milhollen MA, Berger AJ, Gavin JM, Adhikari S, Brownell JE, Burke KE, Cardin DP, Critchley S, et al. 2009. An inhibitor of NEDD8-activating enzyme as a new approach to treat cancer. Nature 458:732–736 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spencer E, Jiang J, Chen ZJ 1999. Signal-induced ubiquitination of IκBα by the F-box protein Slimb/β-TrCP. Genes Dev 13:284–294 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spiegelman VS, Slaga TJ, Pagano M, Minamoto T, Ronai Z, Fuchs SY 2000. Wnt/β-catenin signaling induces the expression and activity of β-TrCP ubiquitin ligase receptor. Mol Cell 5:877–882 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spiegelman VS, Tang W, Katoh M, Slaga TJ, Fuchs SY 2002. Inhibition of HOS expression and activities by Wnt pathway. Oncogene 21:856–860 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sriskantharajah S, Belich MP, Papoutsopoulou S, Janzen J, Tybulewicz V, Seddon B, Ley SC 2009. Proteolysis of NF-κB1 p105 is essential for T cell antigen receptor-induced proliferation. Nat Immunol 10:38–47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun SC, Ley SC 2008. New insights into NF-κB regulation and function. Trends Immunol 29:469–478 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun SC, Ganchi PA, Ballard DW, Greene WC 1993. NF-κ B controls expression of inhibitor IκBα: Evidence for an inducible autoregulatory pathway. Science 259:1912–1915 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan P, Fuchs SY, Chen A, Wu K, Gomez C, Ronai Z, Pan ZQ 1999. Recruitment of a ROC1-CUL1 ubiquitin ligase by Skp1 and HOS to catalyze the ubiquitination of IκB α. Mol Cell 3:527–533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Es JH, Barker N, Clevers H 2003. You Wnt some, you lose some: Oncogenes in the Wnt signaling pathway. Current Opinion Gen Develop 13:28–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Mikecz A 2006. The nuclear ubiquitin-proteasome system. J Cell Sci 119:1977–1984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe N, Arai H, Nishihara Y, Taniguchi M, Hunter T, Osada H 2004. M-phase kinases induce phospho-dependent ubiquitination of somatic Wee1 by SCF(β-TrCP). Proc Natl Acad Sci 101:4419–4424 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei N, Deng XW 2003. The COP9 signalosome. Ann Rev Cell Develop Biol 19:261–286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weil R, Sirma H, Giannini C, Kremsdorf D, Bessia C, Dargemont C, Brechot C, Israël A 1999. Direct association and nuclear import of the hepatitis B virus X protein with the NF-κB inhibitor IκBα. Mol Cell Biol 19:6345–6354 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werner SL, Barken D, Hoffmann A 2005. Stimulus specificity of gene expression programs determined by temporal control of IKK activity. Science 309:1857–1861 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whiteside ST, Epinat JC, Rice NR, Israël A 1997. IκB ε, a novel member of the IκB family, controls RelA and cRel NF-κB activity. EMBO J 16:1413–1426 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winston JT, Strack P, Beer-Romero P, Chu CY, Elledge SJ, Harper JW 1999. The SCF(β-TRCP)-ubiquitin ligase complex associates specifically with phosphorylated destruction motifs in IκBα and β-catenin and stimulates IκBα ubiquitination in vitro. Genes Dev 13:270–283 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf DA, Zhou C, Wee S 2003. The COP9 signalosome: An assembly and maintenance platform for cullin ubiquitin ligases? Nature cell biology 5:1029–1033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu C, Ghosh S 1999. βTrCP mediates the signal-induced ubiquitination of IκBβ. J Biol Chem 274:29591–29594 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu ZH, Miyamoto S 2007. Many faces of NF-κB signaling induced by genotoxic stress. J Mol Med 85:1187–1202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu G, Xu G, Schulman BA, Jeffrey PD, Harper JW, Pavletich NP 2003. Structure of a β-TrCP1-Skp1-β-catenin complex: Destruction motif binding and lysine specificity of the SCF(β-TrCP1) ubiquitin ligase. Molecular cell 11:1445–1456 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao G, Harhaj EW, Sun SC 2001. NF-κB-inducing kinase regulates the processing of NF-κB2 p100. Mol Cell 7:401–409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao G, Fong A, Sun SC 2004. Induction of p100 processing by NF-κB-inducing kinase involves docking IκB kinase α (IKKα) to p100 and IKKα-mediated phosphorylation. J Biol Chem 279:30099–30105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yaron A, Gonen H, Alkalay I, Hatzubai A, Jung S, Beyth S, Mercurio F, Manning AM, Ciechanover A, Ben-Neriah Y 1997. Inhibition of NF-κB cellular function via specific targeting of the IκB-ubiquitin ligase. Embo J 16:6486–6494 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yaron A, Hatzubai A, Davis M, Lavon I, Amit S, Manning AM, Andersen JS, Mann M, Mercurio F, Ben-Neriah Y 1998. Identification of the receptor component of the IκBα-ubiquitin ligase. Nature 396:590–594 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida Y, Chiba T, Tokunaga F, Kawasaki H, Iwai K, Suzuki T, Ito Y, Matsuoka K, Yoshida M, Tanaka K, et al. 2002. E3 ubiquitin ligase that recognizes sugar chains. Nature 418:438–442 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida Y, Tokunaga F, Chiba T, Iwai K, Tanaka K, Tai T 2003. Fbs2 is a new member of the E3 ubiquitin ligase family that recognizes sugar chains. J Biol Chem 278:43877–43884 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zandi E, Chen Y, Karin M 1998. Direct phosphorylation of IκB by IKKα and IKKβ: Discrimination between free and NF-κB-bound substrate. Science 281:1360–1363 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang D, Zaugg K, Mak TW, Elledge SJ 2006. A role for the deubiquitinating enzyme USP28 in control of the DNA-damage response. Cell 126:529–542 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou BP, Deng J, Xia W, Xu J, Li YM, Gunduz M, Hung MC 2004. Dual regulation of Snail by GSK-3β-mediated phosphorylation in control of epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Nat Cell Biol 6:931–940 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]