Abstract

Objective

To determine if hours of daily television viewed by varying age groups of young children with Latina mothers differs by maternal language preference (English/Spanish) and to compare these differences to young children with non-Latina white mothers.

Design

Cross-sectional analysis of data collected in 2000 from the National Survey of Early Childhood Health.

Setting

Nationally representative sample.

Participants

1,347 mothers of children 4-35 months.

Main Exposure

Subgroups of self-reported maternal race/ethnicity (non-Latina white (white), Latina) and within Latinas, stratification by maternal language preference (English/Spanish).

Outcome Measure

Hours of daily television viewed by the child.

Results

Bivariate analyses showed children of English- versus Spanish-speaking Latinas watch more daily television (1.88 versus 1.31 hours,p<0.01). Multivariable regression analyses stratified by age revealed differences by age group. Among 4-11 month olds, children of English- and Spanish-speaking Latinas watch similar amounts of television. However, among children 12-23 and 24-35 months, children of English-speaking Latinas watched more television than children of Spanish-speaking Latinas (IRR=1.61,CI=1.17-2.22; IRR=1.66,CI=1.10-2.51, respectively). Compared to children of white mothers, children of both Latina subgroups watched similar amounts among the 4-11 month olds. However, among 12-23 month olds, children of English-speaking Latinas watched more compared to children of white mothers (IRR=1.57,CI=1.18-2.11). Among 24-35 month olds, children of English-speaking Latinas watched similar amounts compared to children of white mothers, but children of Spanish-speaking Latinas watched less (IRR=0.69,CI=0.50-0.95).

Conclusions

Television viewing amounts among young children with Latina mothers vary by child age and maternal language preference supporting the need to explore sociocultural factors that influence viewing in Latino children.

Introduction

Excessive television viewing in early childhood is associated with a multitude of negative health outcomes including obesity, attention problems, and sleep troubles.1-4 This growing pool of evidence of adverse health sequelae has fueled the development of policy statements related to child television viewing.5, 6 Much of this attention is driven by the relationship of television viewing with obesity; a relationship that has been shown to begin as early as the preschool years.7 This has led to increasing interest in understanding young children's television viewing habits8-10 and to the development of interventions focused on decreasing child television viewing.11, 12

Few studies, however, have focused on understanding television viewing in Latino children, with very few focusing on very young Latino children.13-16 Understanding the viewing habits of this particular population is important because 1 in 5 children in the US is Latino.17 Additionally, Latino children face disparities in many health outcomes18, some of which may be associated with early television habits. For example, Mexican-American preschoolers have a higher prevalence of overweight than non-Hispanic black and non-Hispanic white preschoolers.19 Although results suggest that young Latino children view similar amounts of television per day as non-Hispanic white children,7, 20-23 these studies may fail to recognize heterogeneity within the Latino population. Evidence from studies examining other health behaviors in Latino populations demonstrates the need to consider the heterogeneity of the Latino population, such as primary language spoken, when evaluating health behaviors in Latinos.24-26

Understanding whether differences in television viewing exist in Latino homes by subgroup differences, such as language use, is important to inform the design of interventions that target this population. Language use in Latinos, English versus Spanish, is associated with varying sociocultural characteristics and contexts that influence health behaviors and ultimately the impact of interventions.27-32 Based on the results of multiple studies examining other health behaviors, one could hypothesize that there will be differences in child television viewing by maternal language use.24-26 However, because television viewing is a unique health behavior, currently there is insufficient evidence to hypothesize in what way Latina maternal language use will be associated with child television viewing. Nonetheless, if differences by language exist, they may reflect varying parental beliefs about television viewing, different household arrangements, diverse norms of activity, or different access to media.

Any evaluation of television viewing habits in children must consider the influence of child age. Multiple studies have shown increases in viewing over the first three years of life likely related in part to developmental changes during this period.20, 22

Using data from a large nationally representative sample, our main objective was to determine if hours of daily television viewed by varying age groups of young children with Latina mothers differs by maternal language preference (English/Spanish) and to compare these differences to young children with non-Latina white mothers.

Methods

Data Source

We conducted a cross-sectional analysis of data from a cohort study, the National Survey of Early Childhood Health (NSECH), collected by the National Center for Health Statistics. The methods of the NSECH have been published previously.33, 34 Briefly, in 2000, a nationally representative sample of 2,068 households with children 4-35 months old was surveyed using a stratified random-digit-dial telephone sampling strategy. Black and/or Latino children were over-sampled. Data were collected from the parent or guardian who self-identified as most responsible for the healthcare needs of the child. Eighty-seven percent of respondents were the mother of the child of interest, defined to include biologic, step, foster and adoptive mothers. A computer-assisted telephone interview instrument was utilized. If more than one child in the target age range resided in the household, one child was randomly selected to be the target of the interview. Interviews were performed in English or Spanish, based on the respondent's preference. The interview completion rate was 79.2%. The Council of American Survey Research Organizations survey response rate was 65.6%.33 The latter number accounts for interview completion and households with potentially eligible children that were not reached. Both the Johns Hopkins and the University of Washington (Seattle) institutional review board determined this analysis exempt from review because the database is publicly available.

Main Outcome - number of hours of daily television viewed by the child

Respondents were asked: “In a typical day, about how many hours does your child spend watching television or videos?” Responses were captured as integer values and values above 16 hours a day were considered outliers (n=2) and were dropped from the analyses.

Main Independent Variable – Subgroups of self-reported maternal race/ethnicity (non-Latina white, Latina) and within Latinas, stratification by maternal language preference (English, Spanish)

The main independent variable was created based on the maternal report of race and ethnicity and language preference for the interview. Three subgroups were created including: non-Latina whites, English-speaking Latinas and Spanish-speaking Latinas. The subgroup non-Latina whites includes data from mothers identifying as white and answering “No” to the Hispanic ethnicity question. To facilitate reading of the results, “non-Latina white” is shortened to “white” in the results section. Individuals in the non-Latina white subgroup were interviewed in English, except for one. This individual was interviewed in Spanish and was excluded from the analyses due to the possibility of misclassification. The subgroup of English-speaking Latinas includes those with maternal Hispanic ethnicity and who were interviewed in English. Spanish-speaking Latinas are those mothers declaring Hispanic ethnicity and who were interviewed in Spanish. We used the mother's versus the child's race/ethnicity because it is more likely to represent the sociocultural environment of a child under 3 years old, and therefore more likely to be a determinant of the television viewing habits of these children. Mothers who identified their race as Black or other non-white races and did not declare Hispanic ethnicity were not evaluated in this study. Data from respondents not identifying themselves as the mother of the child of interest were also not utilized.

Covariates

Demographic covariates were selected and included in the final model to control for subgroup compositional differences. The covariates included the child's age and gender, and maternal education level, employment status, age, and marital status. Child's age in months was included in the final model as a continuous variable and used in stratified analysis coded categorically as 4-11, 12-23, and 24-35 months. Maternal education level was categorized as less than high school, high school, and some college or more. Maternal employment status was categorized as full-time, part-time, or unemployed and maternal marital status was categorized as married or not married. Maternal age in years was used as a continuous variable.

A screen for mental health was also included in the final model because maternal mental health has been found to be associated with child television viewing.35 Each participant was given a summary score (continuous) based on responses to the five screening questions in the Mental Health Inventory-5 (MHI-5) screening tool. The MHI-5 has been validated as a measure for depression, anxiety and affective disorder.36 In diverse samples, Cronbach's alpha ranges between 0.82 and 0.93; test-retest correlation is 0.50-0.60.37

For all covariates, responses of “don't know” and refusals were recoded as missing for the analyses.

Analyses

Descriptive statistics and comparative analyses were conducted stratified by maternal subgroups of race/ethnicity (non-Latina whites, Latinas) and within Latinas stratified by maternal language preference (English, Spanish). Demographic characteristics were tested for differences using adjusted Wald tests and Pearson's chi square tests. Number of hours of daily television viewed by the child for identified groups was tested for differences using adjusted Wald tests.

Exploratory analysis of the main outcome variable - hours of daily television viewed by the child - demonstrated a non-normal and overdispersed distribution requiring the use of a negative binomial model.38 This model was used to determine the independent association between subgroups of maternal race/ethnicity and Latina maternal language preference and number of hours of daily television viewed by the child. As is commonly done with negative binomial regressions, the regression coefficients were exponentiated and are reported as incidence rate ratios (IRR) to ease interpretation. A number of multivariable negative binomial models were conducted. All models adjusted for child's age and gender, and maternal education level, employment status, age, marital status, and MHI-5. Three regression models were conducted, one for each age group of children, to determine the independent association between the two subgroups of Latinas (English- versus Spanish-language preference) and number of hours of daily television viewed by the child. Children with Spanish-speaking Latina mothers were the reference group.

A second set of three regression models, one for each child age group, were conducted to determine the independent association between the three subgroups of maternal race/ethnicity and Latina maternal language preference and number of hours of daily television viewed by the child. Children with non-Latina white mothers were the reference group.

Throughout the analyses a p value of less than 0.05 was deemed statistically significant. All summary statistics and analyses were weighted using the available sampling weights. These weights adjust for the survey's complex sampling frame, and were based upon the probability of a household and child being selected as well as multiple other factors.33, 34 Utilization of these weights allow for results to be generalizable to the greater US population of children 4-35 months old. All statistical analyses were performed using Stata (Intercooled Stata 10.1, StataCorp LP, College Station, TX).

Results

Study population

Among maternal respondents reporting non-Latina white (white) or Latina for their race/ethnicity (n=1,347), 1% (15) were excluded from this analysis due to concerns with their recorded data (2 were outliers for the outcome, 1 was a possible misclassification for the main independent variable, and 12 were missing data from one of the covariates). The final study population was 1,332.

Of respondents, 52% (695) were white, 21% (278) were English-speaking Latinas, and 27% (359) were Spanish-speaking Latinas. Characteristics of these subpopulations are presented in Table 1. White mothers were significantly (p value <0.01) older, more often married, and better educated, than English- or Spanish-speaking Latinas. Spanish-speaking Latina mothers had the lowest educational levels with 67% having no high school education.

Table 1. Selected Characteristics of US Children Aged 4 to 35 Months (n=1,332) According to Maternal Race/Ethnicity and Latina Maternal Language Preference Subgroup*.

| Proportion (%) for each subgroup** | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Children of: | |||

| Non-Latina white mothers (n=695) |

English-speaking Latina mothers (n=278) |

Spanish-speaking Latina mothers (n=359) |

|

| Age of children | |||

| 4-11 months | 24 | 30 | 29 |

| 12-23 months | 38 | 47 | 37 |

| 24-35 months | 38 | 22 | 34 |

| Maternal age† (mean yrs, 95% Confidence Interval) | 30.1 (29.5-30.6) | 26.5 (25.4-27.6) | 27.3 (26.6-28.1) |

| Marital status† | |||

| Married | 80 | 52 | 57 |

| Maternal yrs of education† | |||

| < High school | 9 | 32 | 67 |

| High School | 36 | 37 | 23 |

| Some college or more | 54 | 31 | 11 |

| Maternal Employment | |||

| Full-time | 31 | 36 | 26 |

| Part-time | 23 | 15 | 13 |

| Unemployed | 45 | 49 | 61 |

Proportions and means are weighted to be generalizable to the US population of children 4-35 months old.

Proportions unless otherwise noted

Significant differences among all groups, p< 0.05

The initial examination of the mean number of hours of daily television viewed by the child demonstrated that children of Latina mothers (not stratified by maternal language preference) viewed the same amount of daily television as children of white mothers (1.55 vs. 1.55 hours). However, subdividing the sample of children of Latina mothers by maternal language preference demonstrated differences in number of hours of children's daily television viewing between children of English-speaking versus Spanish-speaking Latina mothers, (1.88 vs. 1.31 hours, p value<0.01). Neither of these groups, however, viewed significantly different amounts than children of white mothers (1.55 hours).

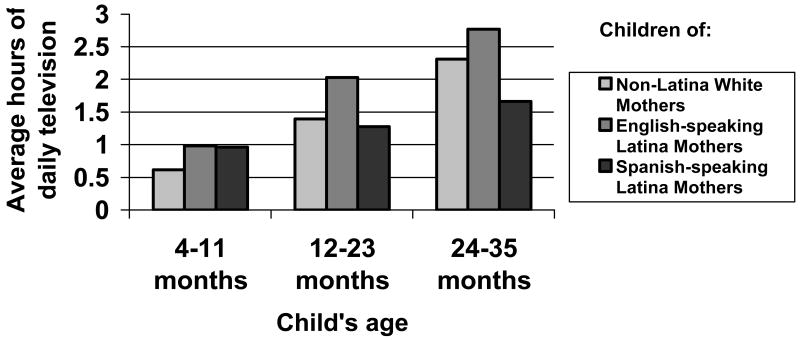

Figure 1 shows the average number of hours of daily television viewed by the child in the three maternal race/ethnicity and Latina maternal language preference subgroups stratified by child age groups. Within each subgroup of children – children of white mothers, English-speaking Latina mothers, and Spanish-speaking Latina mothers – hours of daily television viewed increases significantly with child age (p<0.05).

Figure 1. By Child's Age: Average Hours of Daily Television Viewed by Maternal Race/Ethnicity and Latina Maternal Language Preference Subgroup.

Using three separate multivariable negative binomial regression models, one for each age group of children – 4-11months, 12-23 months, and 24-35 months, analyses showed differences among children with Latina mothers when comparing daily television viewing of children of English-speaking Latina mothers to children of Spanish-speaking Latina mothers. The results in Table 2 show that both groups of children watch similar daily amounts of television during their first year of life. However, differences exist in the second and third years of life with children of English-speaking Latina mothers watching significantly more hours of daily television than children of Spanish-speaking Latinas.

Table 2. For Children of Latinas: Separate Multivariable Negative Binominal Regression Models Conducted for each Child Age Group of Daily Television Hours by Maternal Language Preference Subgroup (English/Spanish)*.

| Children of: | MODEL 1 | MODEL 2 | MODEL 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 4-11 months IRR [95% CI †] |

12-23 months IRR [95% CI†] |

24-35 months IRR [95% CI†] |

|

| Spanish-speaking Latina mothers | Referent | Referent | Referent |

| English-speaking Latina mothers | 0.97 [0.62-1.51] |

1.61 [1.17-2.22] |

1.66 [1.10-2.51] |

Adjusted for: child age and gender, MHI-5, and maternal employment status, education level, age, marital status.

CI = confidence interval

Additional multivariable regression models using data from white and Latina mothers showed differences in viewing for children with Latina mothers, grouped separately by maternal language preference (English/Spanish), as compared to children with white mothers. The model for children aged 4-11 months showed no differences in daily viewed amounts in children of English-speaking or Spanish-speaking Latina mothers compared to children of white mothers. However, as average viewing amounts rise across older age groups of children (Figure 1), differences in viewing amounts across the subgroups of children by maternal race/ethnicity and Latina maternal language preference appear. In the 12-23 month age group, children with English-speaking Latina mothers watch more daily television compared to children of white mothers (IRR=1.57; 95% confidence interval (CI) = 1.18 - 2.11). However, in the age group of children 24-35 months, children with English-speaking Latina mothers now watch similar amounts compared to children with white mothers whereas children with Spanish-speaking Latina mothers watch significantly less (IRR=0.69; CI= 0.50-0.95).

Discussion

These data suggest that the daily television viewing habits of young Latino children vary depending on the maternal language preference and age of the child. Although similar television habits exist in under 1 year olds, by age 3 years, children with English-speaking Latina mothers watch significantly more daily hours of television compared to children of Spanish-speaking Latina mothers, adjusting for demographic and health factors. Likewise, comparing the children of Latina mothers grouped by maternal language preference to children of non-Latina white mothers, results showed similar viewing habits for all children under the age of 1, but by age 3, children with Spanish-speaking Latina mothers are watching significantly less daily hours of television. These findings highlight the need to further understand sociocultural factors influencing television viewing habits in young Latino children. Such factors should be considered by interventionists when designing interventions targeting television viewing in young Latino children. Additionally, these findings emphasize the need for researchers to appreciate the heterogeneity of the Latino population when describing health behaviors and health outcomes in this population.

To date, there has been very little research that considers the influence of sociocultural factors on television viewing in Latino children. Of the three known studies conducted on television viewing in young Latino children, results have not shown differences in television viewing by maternal nativity13, primary language13, 15, or acculturation level.14 However, these studies were limited by their small sample size as well as the homogeneity of their Latino sample population. All three studies sampled mainly low-income, Spanish-speaking immigrant Latina mothers. Strengths of the current study include the large sample size and the sampling of a more heterogeneous Latino population.

Reasons for the differing viewing habits found in this study among Latinos by maternal language preference and child age are potentially numerous, emphasizing the need for further work in this area. One may hypothesize that varying access to either television itself or to valued television content may be a reason for the different viewing habits. However, a recent study found that >99% of Latino families have at least 1 television in the home, such that basic access should not be a reason for the differences we found.39 Increased viewing in English-speaking Latino homes may be due to increased numbers of television sets, hence lending itself to more opportunity for children to watch television. Yet, Borzekowski and Poussaint found no difference in the number of televisions in the home by language in their small sample of mainly immigrant Latina mothers.13 Thus, access to television probably does not explain the differences we found.

Varying access to valued content, however, may be a possible reason for the differences in viewing habits by maternal language preference and age of the child. Access to cable educational television programming or DVD ownership may be increased in English-speaking homes, perhaps due to income. Recently there has been an explosion in the availability of DVDs targeting this age range that claim to be educational.40 Decreased access to such programming in Spanish-speaking homes may lead parents in these homes to turn the television on less frequently due to a perceived lack of child age-appropriate content. This may partially explain why viewing amounts differ in the second and third year of life but not in the first. As children age, there are more and more programs available on DVD that claim age-appropriateness. Also possible is that the lack of easily available public Spanish-language television programming targeting young children may be adding to the differences in viewing habits by language. The main US public Spanish-language television stations, Univision and Telemundo, lack programming oriented towards young children. However, this assumes that Spanish-speaking parents prefer that their young children watch Spanish-language programming. There is some evidence to the contrary. One study found that Spanish-speaking Latina mothers believe that children can improve their language skills by watching English-language shows.13 At this time, it is difficult to conclude what the role of varying access to valued content may play in the development of viewing habits.

A second hypothesis is that differences in viewing habits by language and child age may be a reflection of varying parental beliefs and values about child television viewing. It is possible that Spanish-speaking dominant homes value television viewing differently than English-speaking homes or may value other activities more than television, thus leading to decreased child viewing. This may particularly explain the differences in viewing by age among the subgroups and why television viewing in the homes of Spanish-speaking Latinas does not increase over the age groups as much as it does in the homes of non-Latina white mothers and English-speaking Latina mothers. However, interview language, as is used in this study, is not a specific measure of acculturation, and thus exploration of parental beliefs and values related to television viewing within the Latino population is needed.

The impact of social context must also be considered as a potential factor influencing the development of viewing habits in young children. For example, factors such as parental social supports, social networks, and time demands may influence one's parenting habits. Variation in these factors may be associated with English- versus Spanish-language use. This area, as well as the area of parental beliefs and values, has yet to be well explored in relation to television viewing in Latino children. Experts support the need for the exploration of pathways by which social context and culture influence health behaviors in order to enhance the effectiveness of health interventions.28

Although our data suggest that daily viewing amounts increase at a slower rate in children of Spanish-speaking Latinas compared to children of English-speaking Latinas and non-Latina white mothers, we cannot conclude this due to the cross-sectional study design. A longitudinal study is needed and should include children through the school years to determine if these early differences persist over time. If viewing does truly increase at a slower rate in children of Spanish-speaking Latinas, further explorations of the hypotheses presented above are needed with a specific focus on the interaction of child age and development with these areas. Identification of factors that protect against excessive and increasing viewing in the homes of Spanish-speaking Latinas may prove beneficial to addressing the higher viewing habits in the homes of English-speaking Latinas and non-Latina whites.

This work supports the broader need of health research to understand the heterogeneity of the Latino population and its influence on health behaviors. This study was limited in that only interview language was utilized as an indicator of the heterogeneity within the Latino population. The influence of culture and social context, for example, were not evaluated, but should be investigated in future studies. Additionally, we believe that the language in which the interview was conducted likely reflects the predominant language in the home; however, this is clearly not a perfect measure.41, 42 Hence, future studies should include better indicators of language.

There are additional limitations to our study that warrant mention. The first is that our understanding of television viewing in this sample is limited to hours per day. We are unable to look at the content and context related to this viewing, which are important influences on health outcomes. It would be interesting to know, for example, how content varies in the homes of Spanish- versus English-speaking Latinas. Second, our measure of television viewing by maternal report is most likely not exact. Although a prior study has found such reports to be moderately correlated with actual hours viewed, it is by no means perfect.43 However, we have no reason to believe that the data are systematically biased if they are not true representations. Additionally, random misreporting would bias our findings toward the null.44 Finally, we do not know how mothers are reporting “watching” television in these younger children, whether this means attention given to a program or simply playing in front of the television. Again, we have no reason to believe that the data are systematically biased.

Great attention has recently been given to the need to reduce child television viewing. For those interventions that target young Latino children, findings from this study emphasize the need to appreciate the heterogeneity of Latino populations. In addition, a more in-depth understanding of familial and sociocultural factors influencing television viewing in this population is needed to enhance the efficacy of interventions. Understanding the role of community and neighborhood factors as well as family level factors such as the home context, parental beliefs and parenting practices is essential.

Acknowledgments

Support for this study was provided to the primary author in part by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation through the Robert Wood Johnson Clinical Scholars Program and by the Eunice Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (1K23HD060666-01).

Abbreviations

- CI

confidence interval

- IRR

incident rate ratio

- MHI-5

Mental Health Inventory 5

- NSECH

National Survey of Early Childhood Health

Footnotes

There are no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Publisher's Disclaimer: Disclaimer: The design, conduct of the study, preparation of the manuscript, and opinions are those of the authors and not the sponsoring organizations.

References

- 1.Christakis DA, Zimmerman FJ, DiGiuseppe DL, McCarty CA. Early television exposure and subsequent attentional problems in children. Pediatrics. 2004;113:708–713. doi: 10.1542/peds.113.4.708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Robinson TN. Reducing children's television viewing to prevent obesity: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 1999;282:1561–1567. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.16.1561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thompson DA, Christakis DA. The association between television viewing and irregular sleep schedules among children less than 3 years of age. Pediatrics. 2005;116:851–856. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-2788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schmidt ME, Pempek TA, Kirkorian HL, Lund AF, Anderson DR. The effects of background television on the toy play behavior of very young children. Child Dev. 2008;79:1137–1151. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2008.01180.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.American Academy of Pediatrics. Children, adolescents, and television. Pediatrics. 2001;107:423–426. doi: 10.1542/peds.107.2.423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.US Department of Health and Human Services. Healthy People 2010. Washington, DC: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mendoza JA, Zimmerman FJ, Christakis DA. Television viewing, computer use, obesity, and adiposity in US preschool children. The International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity. 2007;4:44–54. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-4-44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barr-Anderson DJ, van den Berg P, Neumark-Sztainer D, Story M. Characteristics associated with older adolescents who have a television in their bedrooms. Pediatrics. 2008;121:718–724. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-1546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barradas DT, Fulton JE, Blanck HM, Huhman M. Parental influences on youth television viewing. J Pediatr. 2007;151:369–73. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2007.04.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Christakis DA, Zimmerman FJ. Media as a public health issue. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2006;160:445–446. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.160.4.445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dennison BA, Russo TJ, Burdick PA, Jenkins PL. An intervention to reduce television viewing by preschool children. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2004;158:170–176. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.158.2.170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Johnson DB, Birkett D, Evens C, Pickering S. Statewide intervention to reduce television viewing in WIC clients and staff. American Journal of Health Promotion. 2005;19:418–421. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-19.6.418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Borzekowski DLG, Poussaint AF. Latino American preschoolers and the media. Philadelphia: The Annenberg Public Policy Center; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kennedy CM. Television and young Hispanic children's health behaviors. Pediatr Nurs. 2000;26:283–8. 292–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tomopoulos S, Dreyer BP, Valdez P, et al. Media content and externalizing behaviors in Latino toddlers. Ambul Pediatr. 2007;7:232–238. doi: 10.1016/j.ambp.2007.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thompson DA, Flores G, Ebel BE, Christakis DA. Comida en venta: After-school advertising on Spanish-language television in the United States. Journal of Pediatrics. 2008;152:576–581. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2007.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hernandez D. Young Hispanic children in the US: A demographic portrait based on census 2000. New York: National Task Force on Early Childhood Education for Hispanics, Foundation for Child Development; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Flores G, Tomany-Korman SC. Racial and ethnic disparities in medical and dental health, access to care, and use of services in US children. Pediatrics. 2008;121:e286–98. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-1243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ogden CL, Troiano RP, Briefel RR, Kuczmarski RJ, Flegal KM, Johnson CL. Prevalence of overweight among preschool children in the United States, 1971 through 1994. Pediatrics. 1997;99:E1–E7. doi: 10.1542/peds.99.4.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Certain LK, Kahn RS. Prevalence, correlates, and trajectory of television viewing among infants and toddlers. Pediatrics. 2002;109:634–642. doi: 10.1542/peds.109.4.634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bickham DS, Vandewater EA, Huston AC, Lee JH, Caplovitz AG, Wright JC. Predictors of children's electronic media use: An examination of three ethnic groups. Media Psychology. 2003;5:107–137. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Anand S, Krosnick JA. Demographic predictors of media use among infants, toddlers, and preschoolers. American Behavioral Scientist. 2005;48:539–561. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rideout VJ, Hamel E. The media family: Electronic media in the lives of infants, toddlers, preschoolers and their parents. Menlo Park, CA: Kaiser Family Foundation; May, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dixon LB, Sundquist J, Winkleby M. Differences in energy, nutrient, and food intakes in a US sample of Mexican American women and men: Findings from the third national health and nutrition examination survey, 1988-1994. Am J Epidemiol. 2000;152:548–557. doi: 10.1093/aje/152.6.548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Epstein JA, Doyle M, Botvin GJ. A mediational model of the relationship between linguistic acculturation and polydrug use among Hispanic adolescents. Psychol Rep. 2003;93:859–866. doi: 10.2466/pr0.2003.93.3.859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chan KS, Keeler E, Schonlau M, Rosen M, Mangione-Smith R. How do ethnicity and primary language spoken at home affect management practices and outcomes in children and adolescents with asthma? Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2005;159:283–289. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.159.3.283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Allen ML, Elliott MN, Fuligni AJ, Morales LS, Hambarsoomian K, Schuster MA. The relationship between Spanish language use and substance use behaviors among Latino youth: A social network approach. J Adolesc Health. 2008;43:372–379. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2008.02.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sorensen G, Emmons K, Hunt MK, et al. Model for incorporating social context in health behavior interventions: Applications for cancer prevention for working-class, multiethnic populations. Prev Med. 2003;37:188–197. doi: 10.1016/s0091-7435(03)00111-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kirkman-Liff B, Mondragon D. Language of interview: Relevance for research of southwest Hispanics. Am J Public Health. 1991;81:1399–1404. doi: 10.2105/ajph.81.11.1399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kossoudji SA. English language ability and the labor market opportunities of Hispanic and east Asian immigrant men. J Labor Econ. 1988;6:205–228. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Enchautegui ME. Latino neighborhoods and Latino neighborhood poverty. Journal of Urban Affairs. 1997;19:445–467. [Google Scholar]

- 32.South SJ, Crowder K, Chavez E. Migration and spatial assimilation among U.S. Latinos: classical versus segmented trajectories. Demography. 2005;42:497–521. doi: 10.1353/dem.2005.0025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Blumberg SJ, Halfon N, Olson LM. The National Survey of Early Childhood Health. Pediatrics. 2004;113:1899–1906. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Blumberg SJ, Olson L, Osborn L, et al. Design and operation of the national survey of early childhood health, 2000. Vital Health Stat 1. 2002;(40):1–97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Thompson DA, Christakis DA. The association of maternal mental distress with television viewing in children under 3 years old. Ambulatory pediatrics. 2007;7:32–37. doi: 10.1016/j.ambp.2006.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McHorney CA, Ware JE., Jr Construction and validation of an alternate form general mental health scale for the medical outcomes study short-form 36-item health survey. Med Care. 1995;33:15–28. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199501000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stewart AL, Hays RD, Ware JE., Jr The MOS short-form general health survey. reliability and validity in a patient population. Med Care. 1988;26:724–735. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198807000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cameron AC, Trivedi PK. Regression Analysis of Count Data. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Roberts DF, Foehr UG, Rideout VJ, Brody M. Kids & media @ the new millenium. Menlo Park, CA: Kaiser Family Foundation; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Garrison MM, Christakis DA. A teacher in the living room? Educational media for babies, toddlers and preschoolers. Menlo Park, CA: The Kaiser Family Foundation; 2005. Report number: 7427. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cruz TH, Marshall SW, Bowling JM, Villaveces A. The validity of a proxy acculturation scale among U.S. Hispanics. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 2008;30:425–446. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Eamranond PP, Legedza AT, Diez-Roux AV, Kandula NR, Palmas W, Siscovick DS, Mukamal KJ. Association between language and risk factor levels among Hispanic adults with hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, or diabetes. Am Heart J. 2009;157:53–59. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2008.08.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Anderson DR, Field DE, Collins PA, Lorch EP, Nathan JG. Estimates of young children's time with television: A methodological comparison of parent reports with time-lapse video home observation. Child Development. 1985;56:1345–1357. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1985.tb00202.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Clayton D, Hills M. Statistical Models in Epidemiology. Oxford: Oxford Science Publications; 1993. [Google Scholar]