Abstract

Noninvasive assessment of cardiac structure and function is essential to understand the natural course of murine infection with Trypanosoma cruzi. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and echocardiography have been used to monitor anatomy and function; positron emission tomography (PET) is ideal for monitoring metabolic events in the myocardium. Mice infected with T. cruzi (Brazil strain) were imaged 15–100 days post infection (dpi). Quantitative 18F-FDG microPET imaging, MRI and echocardiography were performed and compared. Tracer (18F-FDG) uptake was significantly higher in infected mice at all days of infection, from 15 to 100 dpi. Dilatation of the right ventricular chamber was observed by MRI from 30 to 100 dpi in infected mice. Echocardiography revealed significantly reduced ejection fraction by 60 dpi. Combination of these three complementary imaging modalities makes it possible to noninvasively quantify cardiovascular function, morphology, and metabolism from the earliest days of infection through the chronic phase.

INTRODUCTION

Chagas disease, caused by the protozoan parasite Trypanosoma cruzi, is an important cause of heart disease in endemic areas of Mexico, Central and South America.1 One of the hallmarks of infection is the inflammatory process in the myocardium at the early stage of disease, when parasitemia and tissue parasitism are intense.2 The acute infection is followed by the indeterminate phase, which can last for many years or a life-time. Ten percent to 30% of all sero-positive patients will eventually progress to a cardiomyopathy associated with congestive heart failure and/or conduction abnormalities.3 An accurate assessment of myocardial function is important in the evaluation of the prognosis of an individual patient.4

Murine models of Chagas disease have been extensively evaluated and have been shown to recapitulate many of the pathologic and immunologic characteristics of human disease.5–8 To study the natural course of murine infection non-invasive assessment of cardiac structure and function is essential. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and echocardiography have been used with increasing frequency because they permit serial examination of a single animal during disease progression.9–13

With the advent of molecular imaging modalities, particularly positron emission tomography (PET), the visualization and quantification of cellular and molecular processes occurring in living tissues are now possible. 14,15 The PET measures the in vivo body distribution of imaging agents labeled with positron-emitting radionucleotides and has been extensively used in humans to characterize the heart with respect to properties such as perfusion, 16,17 metabolism,18,19 innervation,20,21 and cardiac function. 22,23 With the introduction of high-resolution small-animal PET, 24,25 in vivo molecular imaging of myocardial metabolism in small laboratory animals, mostly mice and rats, has become possible.

Here, we applied quantitative 18F-FDG micro-positron emission tomography (microPET) imaging of CD1 mice infected with T. cruzi (Brazil strain) in a serial time course from 15 to 100 days post-infection (dpi). The MRI and echocardiography were performed at the same time points and data from the different modalities were compared. Although morphologic and functional alterations in the heart of infected mice were observed at 30 dpi using MRI and echocardiography, differences in glucose uptake were detected by microPET at an earlier time point. These results show that 18 F-FDG microPET imaging can detect cardiac metabolic defects before morphologic and functional changes in the heart become apparent.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Parasitology and pathology

The Brazil strain of T. cruzi was maintained in C3H mice (Jackson Laboratories, Bar Harbor, ME). Male CD1 mice (Jackson Laboratories) were infected intraperitoneally at 10 weeks of age with 5 × 104 trypomastigotes. All mice were housed in the Institute for Animal Studies of the Albert Einstein College of Medicine and all protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC). The mice were imaged 15, 30, 60, and 100 dpi. Hearts were placed in 10% phosphate-buffered formaldehyde and stained with hematoxylin and eosin and sirius red.

Micro-positron emission tomography (MicroPET)

All mice were imaged after 3 hours of fasting. Mice were anesthetized with 1.5% isoflurane-oxygen mixture, which continued throughout the imaging portion of the procedure. Each mouse was placed on a heating pad before and during scanning to maintain normal body temperature. Mice were administered 300–400 uCi (12–15 MBq) in 0.1 mL normal saline, [18F] fluoro-2-deoxyglucose (FDG), via tail vein and imaging was started at 1 hour after injection. This period permits the tracer to be delivered throughout the body and trapped by the glycolytic pathway. Cardiac gating of the PET acquisition was accomplished using standard electrocardiogram (ECG) contacts and a Gould ECG amplifier interfaced to the PET scanner (for gating) and a PC running Ponemah Physiology Suite software (for monitoring) (Gould Instrument Systems, Inc., Valley View, OH). After MicroPET imaging, the animals were housed in a dedicated hood until they could be safely moved back to the Animal Institute (18F has a half-life of 110 minutes). Imaging was performed using a Concorde Microsystems R4 microPET Scanner (Concorde Microsystems, LLC, Siemens, Knoxville, TN), with 24 detector modules, without septa, providing 7.9 cm axial and 12 cm transaxial field of view. Acquisitions were performed in three-dimensional (3D) list mode. A reconstructed full-width half maximum resolution of 2.2 mm was achievable in the center of the axial field of view. After 10 minutes of list mode acquisition, data were sorted into 3D sinograms, and images were reconstructed using iterative reconstruction in a 128 × 128 × 64 (0.82 × 0.82 × 1.2 mm) pixel array. Data were corrected for deadtime counting losses, random coincidences, and the measured nonuniformity of detector response (i.e., normalized) but not for attenuation or scatter.

Image analysis was performed using ASIPRO VM (Concorde Microsystems, LLC) dedicated software. All studies were inspected visually in a rotating 3D display to examine for interpretability and image artifact. Manual regions of interest (ROI) were defined around areas of visually identified heart activity in the left ventricle (LV). Successive scrolling through 2 dimensional slices (each 1.2 mm thick in the axial images) permitted identification of a pixel of maximum measured decay-corrected uptake, termed the standardized uptake value, or SUVmax. The SUVmax is the maximum value of the percent-age injected dose per gram of cardiac tissue multiplied by the body weight of each animal. The SUVmax has been validated in numerous animal and human models as a reproducible and robust measure of radioactivity in longitudinal studies. The cardiac gating of the PET images permitted qualitative observation of the motion of the heart and right ventricular dimension. Sample movies of representative hearts are presented in the supplementary information (Supplementary videos can be found online at www.ajtmh.org).

Cardiac gated MRI

Mice were anesthetized with 1.5% of isoflurane. A set of standard, shielded, nonmagnetic electrocardiographic leads ending in silver wires were attached to the four limbs. The ECG signal was fed to a Gould ECG amplifier associated with the Ponemah Physiology data acquisition system for monitoring the ECG and the R wave triggered a 5 volt signal to gate the spectrometer. Images were acquired with a GE/Omega 9.4 T vertical wide-bore spectrometer operating at a 1H frequency of 400 MHz and equipped with 50-mm shielded gradients (General Electric, Fremont, CA) and a 40-mm 1H imaging coil (RF Sensors, New York, NY). Temperature within the coils was maintained at 30°C using a water cooling unit (Neslab Instrument, Inc., Portsmouth, NH). This temperature prevented hypothermia in the anesthetized mice. After attachment of the cardiac gating leads, the mice were wrapped in a Teflon sheet and multislice spin echo imaging was performed to obtain short axis images of the heart. The gating delay was adjusted to collect data in systole or diastole. The following parameters were used to obtain 8 short axis slices: echo time, 18 msec; field of view, 51.2 mm; number of averages, 4; slice thickness, 1 mm; repetition time, approximately 0.2 sec; matrix size, 128 × 256 (interpolated to 256 × 256). Several sets of 8 slices were acquired to define the entire heart and to obtain images in diastole and systole taking approximately 20–30 minutes per mouse. Data were transferred to a PC and analyzed using MATLAB-based software (The MathWorks, Natick, MA). Left ventricle and right ventricle (RV) dimensions in millimeters were determined from the images representing end-diastole. The left ventricular wall is the average of the anterior, posterior, lateral, and septal walls. The right ventricular internal dimension is the widest point of the right ventricular cavity.

Echocardiography

Mice were lightly anesthetized with 1.5% isoflurane in 100% O2; the chest wall was shaved and a small gel standoff was placed between the chest and a 30-MHz RMV-707 B scanhead interfaced with a Vevo 770 High-Resolution Imaging System (VisualSonics, Toronto, ON, Canada). High-resolution, two-dimensional electrocardiogram-based kilohertz visualization (EKV Mode) and B mode images were acquired. Continuous, standard electrocardiogram was recorded using electrodes placed on the animal’s extremities. Diastolic measurements were performed at the point of greatest cavity dimension, and systolic measurements were made at the point of minimal cavity dimension, using the leading edge method of the American Society of Echocardiography. 26 Ejection fraction was calculated and used as a determinant of LV cardiac function.

Statistical analysis

All data are expressed as the mean (±SEM) and were analyzed using GraphPad Prism 4 statistics software (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA). For analysis of differences between groups the Student’s t test was performed. A level of significance of 5% was chosen to denote differences between means.

RESULTS

Parasitology and pathology

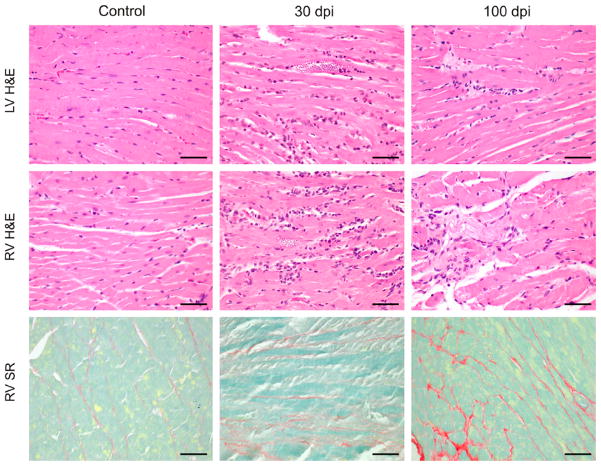

Infected mice had a peak of parasitemia of approximately 1 × 106 trypomastigotes/mL of plasma at Day 20 dpi. Between 27 and 33 dpi, the mortality peaked at 47% (14 out of 30). At 30 dpi there was an intense and diffuse myocarditis characterized by lymphomononuclear interstitial infiltrate, disruption of myofibers, and multiple pseudocysts. There was also perivascular inflammatory infiltrate. At 60 and 100 dpi, the inflammation became significantly less intense and parasites were not detected. Myocardium reparative fibrosis, evidenced by sirius red staining of collagen, was more extensive in the RV (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and sirius red (SR) staining of myocardium from CD1 mice uninfected (control) and infected 30 and 100 dpi. At 30 dpi there was intense and diffuse myocarditis. These findings are more evident in the right ventricle (RV) than left ventricle (LV). At 100 dpi, the inflammation became significantly less intense and myocardium reparative fibrosis was seen. The SR staining shows the collagen content and reparative fibrosis in the right ventricle. Bars = 50 μm. This figure appears in color at www.ajtmh.org.

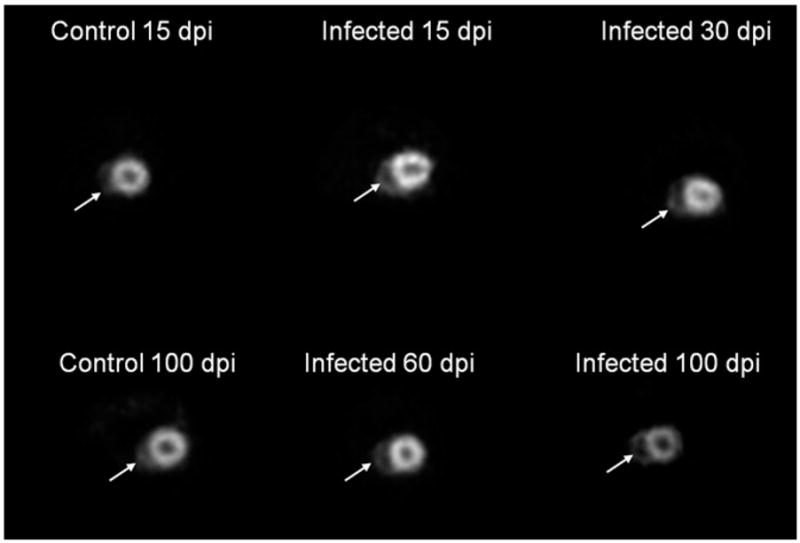

MicroPET analysis

The metabolic state of the myocardium was assessed by the regional uptake of the glucose analogue, 18F-FDG. The mean value of the myocardial SUVmax was used to compare the MicroPET data between the uninfected age-matched controls and infected groups at the different days post infection. Tracer uptake was significantly higher in the LV myocardium of the infected mice compared with controls at all days of infection, from 15 to 100 dpi (Table 1). MicroPET was also used to visualize cardiac morphology (Figure 2) and contractility (Supplemental data).

Table 1.

Standardized uptake value of 18F-FDG from control and infected mice

| 15 days control (3) infected (5) | 30 days control (4) infected (6) | 60 days control (4) infected (5) | 100 days control (4) infected (5) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SUV† max | 12.11 ± 0.82 | 17.95 ± 1.63* | 11.70 ± 1.35 | 19.1 ± 1.39** | 9.57 ± 1.12 | 15.80 ± 1.77* | 9.17 ± 0.36 | 12.95 ± 1.11* |

Mean ± SEM,

P < 0.05

P < 0.01,

n for each time point is in parentheses.

SUV = standardized uptake value.

Figure 2.

Transverse microPET images of control and infected mice showing the short axis of the heart. Although left and right ventricular internal diameters were not measured (because of limited resolution of the MicroPET in comparison to the magnetic resonance imaging [MRI]) comparison of the MicroPET images from infected mice with those of the uninfected mice clearly shows enlargement of the right ventricular chamber, particularly at 100 dpi. Arrows = RV.

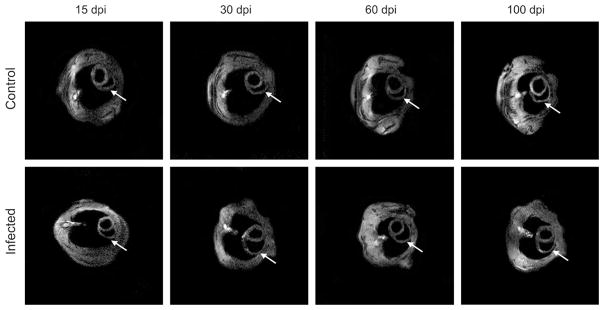

Cardiac MRI

Figure 3 shows representative MRI images of the short axis of the hearts of control and infected mice. As we previously observed, there was no difference in LV internal diameter during the period studied in infected mice compared with uninfected controls (data not shown). However, the inner dimension of the RV was significantly dilated from 30 to 100 dpi (Table 2). This increase in right ventricular chamber dimension was 95% at 30 dpi (1.88 ± 0.15 versus 3.66 ± 0.21 mm, control versus infected), 80% at 60 dpi (1.49 ± 0.13 versus 2.69 ± 0.23 mm) and 54% at 100 dpi (1.66 ± 0.24 versus 2.56 ± 0.15 mm). The left ventricle wall thickness (LVWT) was increased by 11.4% at 100 dpi (1.23 ± 0.03 versus 1.37 ± 0.05 mm). There was no difference in LVWT at 15, 30, and 60 dpi in comparison to uninfected controls.

Figure 3.

Transverse magnectic resonance imaging (MRI) images of mice showing the short axis of the heart. There was no difference in left ventricular internal diameter during the period studied in infected mice compared with uninfected controls. However, the inner dimension of the right ventricle (RV) was significantly dilated from 30 to 100 dpi. The left ventricle wall thickness (LVWT) was increased at 100 dpi. There was no difference in LV wall thickness at 15, 30, and 60 dpi in comparison to uninfected controls. Arrows = RV.

Table 2.

Magnectic resonance imaging (MRI)-derived right ventricular internal diameter (RVID) and left ventricle wall thickness (LVWT) dimensions in control and infected mice

| 15 days Control (4) Infected (4) | 30 days Control (4) Infected (7) | 60 days Control (5) Infected (5) | 100 days Control (4) Infected (5) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RVID (mm) | 2.04 ± 0.11 | 2.00 ± 0.15 | 1.88 ± 0.15 | 3.66 ± 0.21*** | 1.49 ± 0.13 | 2.69 ± 0.23** | 1.66 ± 0.24 | 2.56 ± 0.15* |

| LV wall (mm) | 1.08 ± 0.06 | 1.17 ± 0.07 | 1.19 ± 0.04 | 1.26 ± 0.05 | 1.32 ± 0.03 | 1.31 ± 0.04 | 1.23 ± 0.03 | 1.37 ± 0.05* |

Mean ± SEM,

P < 0.05

P < 0.01

P < 0.0001,

n for each time point is in parentheses.

Echocardiography

Infected mice exhibited a significant reduction in LV ejection fraction at 60 and 100 dpi (Table 3). The normal heart rate for mice ranges from 500 to 600 beats per minute. A slower heart rate was noted in some infected mice.

Table 3.

Echocardiographic data for control and infected mice

| 15 days Control (4) Infected (5) | 30 days Control (4) Infected (7) | 60 days Control (4) Infected (5) | 100 days Control (4) Infected (5) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ejection fraction (%) | 50.28 ± 3.83 | 57.33 ± 7.56 | 55.22 ± 1.66 | 47.12 ± 3.73 | 60.82 ± 1.87 | 49.62 ± 3.16* | 64.65 ± 3.37 | 51.38 ± 3.51* |

| Heart rate (bpm) | 630.0 ± 6.45 | 585.3 ± 21.86 | 605.8 ± 5.29 | 537.7 ± 18.64* | 549.8 ± 22.67 | 561.6 ± 28.59 | 545.3 ± 19.25 | 529.4 ± 32.34 |

Mean ± SEM,

P < 0.05.

EF = ejection fraction,

n for each time point is in parentheses.

DISCUSSION

Our laboratory pioneered the application of cardiac imaging techniques in mouse models of T. cruzi-induced heart disease. 11,13,27 In previous studies, we showed the use of cardiac MRI and echocardiography in the evaluation of alterations in structure and function accompanying this infection. MicroPET is a relatively new technique for evaluating cardiac structure and function. 28 In this study using this technique, we showed for the first time that T. cruzi-infected mice display greater uptake of glucose throughout the time course of infection compared with uninfected controls. Importantly, this is the first study comparing data from three different noninvasive imaging modalities, MRI, echocardiography, and micro-PET, for the serial assessment of myocardial viability and cardiac structure and function in mice infected with T. cruzi from acute to chronic phase.

Cardiac MRI findings confirmed our previous observation of significant dilatation of the right ventricular chamber was from 30 to 100 dpi in infected mice when compared with controls. 10,13,27,29,30 There was no difference in the left ventricular internal diameter between groups and LVWT was increased only at 100 dpi. MRI allows accurate, high resolution 3D characterization of cardiac structure within a single examination and allows the quantification of volumetric changes in hearts. 31 However, technical difficulties related to anesthesia, irregular heart rates, and thermoregulation can arise during the acquisition of cardiac gated MRI studies, which require signal averaging over a time period of several minutes. 32,33

Echocardiography confirmed our previous observation that the ejection fraction, a measurement of myocardial systolic performance, was decreased at 60 and 100 dpi. 11 Echocardiography has been used by our group. 11,34,35 and others 36–40 as an important tool in the assessment of cardiac function in murine models of cardiac disease. A particular disadvantage of the echocardiographic method for evaluation of hearts of T. cruzi-infected mice is the difficulty in assessing the RV, because the images are typically acquired along the parasternal long axis, which obscures the location of the RV.

Our MicroPET study showed that T. cruzi-infected mice displayed increased uptake of glucose in the myocardium when compared with controls as early as 15 dpi, whereas alterations in morphologic parameters, such as right ventricular internal diameter (RVID) and LVWT, were not detected by MRI until 30 dpi. Alteration in cardiac function measured by echocardiography (ejection fraction) was not detected until 60 dpi. The PET uptake provides information regarding the metabolic state of the myocardium through the regional uptake of 18F-FDG, a glucose analogue. 41 After transport into cells, 18F-FDG undergoes subsequent hexokinase-mediated phosphorylation, but is not further metabolized resulting in metabolic trapping of the radiotracer in cells that exhibit enhanced glucose metabolism. 14 MicroPET has been used for monitoring metabolic events in the myocardium of small animals in stem cell transplantation after myocardial infarction, 41,42 progressive hypertrophy, 43 and left ventricular dilation. 44 Increased FDG uptake has been shown in vitro in leukocytes, 45 lymphocytes, and macrophages 46,47 and in vivo in acute myocardial infarction, 48 abdominal aortic aneurism, 49 and atherosclerosis. 50 The increased uptake of FDG in T. cruzi-infected mice correlates with the intense and diffuse myocarditis observed during the acute phase and chronic inflammation and myocardium reparative fibrosis that occurs during the chronic phase. An important characteristic of PET is that it is largely independent of the thickness of the object and the depth of the source within the subject. Thus, in addition to providing information on glucose uptake, the microPET images also permit visualization of the dilation of the RV (as shown in Figure 3) and contractility (see Supplemental data).

In conclusion, we showed that by combining complementary imaging methodologies, MRI, echocardiography, and MicroPET it is possible to noninvasively quantify parameters related to cardiovascular function, morphology, and myocardium metabolism of mice infected with T. cruzi from the earliest days of infection through the chronic phase. Our MicroPET data shows metabolic changes in the LV as early as 15 dpi, likely associated with inflammation that appears before alterations in structure and function of the myocardium are detected. These approaches permit serial examinations and can be used in longitudinal studies over the time course of the disease process to provide important insights into disease biology and pathophysiology. Furthermore, these findings suggest that PET may be a useful tool to track early response to therapeutic agents and to evaluate efficacy of therapeutics in patients.

Acknowledgments

We thank Lina M. Restrepo for training in use of the echocardiographic equipment and Jorge Durand for MRI assistance.

Financial support: NIH grant AI076248(HBT), CMP was supported by Fogarty International Training grant D43-TW007129 (HBT) and Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo (06/52882-3; 06/59618-0; 08/00954-6).

Footnotes

Note: Supplemental data can be found online at www.ajtmh.org.

Publisher's Disclaimer: Disclaimer: There are no potential conflicts of interest.

Authors’ addresses: Cibele M. Prado and Marcos A. Rossi, Department of Pathology, Faculty of Medicine of Ribeirão Preto, University of São Paulo, Av. Bandeirantes n 3900, Monte Alegre, CEP 14049-900, Ribeirão Preto, São Paulo, Brazil. Eugene J. Fine and Wade Koba, M. Donald Blaufox Laboratory for Molecular Imaging, Department of Medicine and Radiology, Albert Einstein College of Medicine, 1300 Morris Park Avenue, Bronx, NY 10461. Dazhi Zhao, Department of Pathology, Albert Einstein College of Medicine, 1300 Morris Park Avenue, Bronx, NY 10461. Herbert B. Tanowitz, Department of Pathology, Albert Einstein College of Medicine, 1300 Morris Park Avenue, Bronx, NY 10461, Tel: 718-430-3342, Fax: 718-430-8543, E-mail: tanowitz@aecom.yuedu. Linda A. Jelicks, Department of Physiology and Biophysics, Albert Einstein College of Medicine, 1300 Morris Park Avenue, Bronx, NY 10461.

References

- 1.Tanowitz HB, Machado FS, Jelicks LA, Shirani J, de Carvalho AC, Spray DC, Factor SM, Kirchhoff LV, Weiss LM. Perspectives on Trypanosoma cruzi-induced heart disease (Chagas disease) Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2009;51:524–539. doi: 10.1016/j.pcad.2009.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rossi MA, Ramos SG, Bestetti RB. Chagas’ heart disease: clinical-pathological correlation. Front Biosci. 2003;8:e94–e109. doi: 10.2741/948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Higuchi Mde L, Benvenuti LA, Martins Reis M, Metzger M. Pathophysiology of the heart in Chagas’ disease: current status and new developments. Cardiovasc Res. 2003;60:96–107. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(03)00361-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rochitte CE, Nacif MS, de Oliveira Júnior AC, Siqueira-Batista R, Marchiori E, Uellendahl M, de Lourdes Higuchi M. Cardiac magnetic resonance in Chagas’ disease. Artif Organs. 2007;31:259–267. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1594.2007.00373.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mukherjee S, Nagajyothi F, Mukhopadhyay A, Machado FS, Belbin TJ, Campos de Carvalho A, Guan F, Albanese C, Jelicks LA, Lisanti MP, Silva JS, Spray DC, Weiss LM, Tanowitz HB. Alterations in myocardial gene expression associated with experimental Trypanosoma cruzi infection. Genomics. 2008;91:423–432. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2008.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gomes JA, Bahia-Oliveira LM, Rocha MO, Busek SC, Teixeira MM, Silva JS, Correa-Oliveira R. Type 1 chemokine receptor expression in Chagas’ disease correlates with morbidity in cardiac patients. Infect Immun. 2005;73:7960–7966. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.12.7960-7966.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Machado FS, Koyama NS, Carregaro V, Ferreira BR, Milanezi CM, Teixeira MM, Rossi MA, Silva JS. CCR5 plays a critical role in the development of myocarditis and host protection in mice infected with Trypanosoma cruzi. J Infect Dis. 2005;191:627–636. doi: 10.1086/427515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Michailowsky V, Celes MR, Marino AP, Silva AA, Vieira LQ, Rossi MA, Gazzinelli RT, Lannes-Vieira J, Silva JS. Intercellular adhesion molecule 1 deficiency leads to impaired recruitment of T lymphocytes and enhanced host susceptibility to infection with Trypanosoma cruzi. J Immunol. 2004;173:463–470. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.1.463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Scherrer-Crosbie M. Role of echocardiography in studies of murine models of cardiac diseases. Arch Mal Coeur Vaiss. 2006;99:237–241. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.De Souza AP, Tang B, Tanowitz HB, Araújo-Jorge TC, Jelicks LA. Magnetic resonance imaging in experimental Chagas disease: a brief review of the utility of the method for monitoring right ventricular chamber dilatation. Parasitol Res. 2005;97:87–90. doi: 10.1007/s00436-005-1409-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chandra M, Shirani J, Shtutin V, Weiss LM, Factor SM, Petkova SB, Rojkind M, Dominguez-Rosales JA, Jelicks LA, Morris SA, Wittner M, Tanowitz HB. Cardioprotective effects of verapamil on myocardial structure and function in a murine model of chronic Trypanosoma cruzi infection (Brazil strain): an echocardiographic study. Int J Parasitol. 2002;32:207–215. doi: 10.1016/s0020-7519(01)00320-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jelicks LA, Chandra M, Shirani J, Shtutin V, Tang B, Christ GJ, Factor SM, Wittner M, Huang H, Weiss LM, Mukherjee S, Bouzahzah B, Petkova SB, Teixeira MM, Douglas SA, Loredo ML, D’Orleans-Juste P, Tanowitz HB. Cardioprotective effects of phosphoramidon on myocardial structure and function in murine Chagas’ disease. Int J Parasitol. 2002;32:1497–1506. doi: 10.1016/s0020-7519(02)00136-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jelicks LA, Shirani J, Wittner M, Chandra M, Weiss LM, Factor SM, Bekirov I, Braunstein VL, Chan J, Huang H, Tanowitz HB. Application of cardiac gated magnetic resonance imaging in murine Chagas’ disease. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1999;61:207–214. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1999.61.207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Johannsen B. The usefulness of radiotracers to make the body biochemically transparent. Amino Acids. 2005;29:307–311. doi: 10.1007/s00726-005-0199-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Phelps ME. Inaugural article: positron emission tomography provides molecular imaging of biological processes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:9226–9233. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.16.9226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Iida H, Takahashi A, Tamura Y, Ono Y, Lammertsma AA. Myocardial blood flow: comparison of oxygen-15-water bolus injection, slow infusion and oxygen-15-carbon dioxide slow inhalation. J Nucl Med. 1995;36:78–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Araujo LI, Lammertsma AA, Rhodes CG, McFalls EO, Iida H, Rechavia E, Galassi A, De Silva R, Jones T, Maseri A. Noninvasive quantification of regional myocardial blood flow in coronary artery disease with oxygen-15-labeled carbon dioxide inhalation and positron emission tomography. Circulation. 1991;83:875–885. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.83.3.875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Camici P, Araujo LI, Spinks T, Lammertsma AA, Kaski JC, Shea MJ, Selwyn AP, Jones T, Maseri A. Increased uptake of 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose in postischemic myocardium of patients with exercise-induced angina. Circulation. 1986;74:81–88. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.74.1.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ratib O, Phelps ME, Huang SC, Henze E, Selin CE, Schelbert HR. Positron tomography with deoxyglucose for estimating local myocardial glucose metabolism. J Nucl Med. 1982;23:577–586. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Law MP, Osman S, Pike VW, Davenport RJ, Cunningham VJ, Rimoldi O, Rhodes CG, Giardinà D, Camici PG. Evaluation of [11C]GB67, a novel radioligand for imaging myocardial alpha 1-adrenoceptors with positron emission tomography. Eur J Nucl Med. 2000;27:7–17. doi: 10.1007/pl00006665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schäfers M, Dutka D, Rhodes CG, Lammertsma AA, Hermansen F, Schober O, Camici PG. Myocardial presynaptic and postsynaptic autonomic dysfunction in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Circ Res. 1998;82:57–62. doi: 10.1161/01.res.82.1.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rajappan K, Livieratos L, Camici PG, Pennell DJ. Measurement of ventricular volumes and function: a comparison of gated PET and cardiovascular magnetic resonance. J Nucl Med. 2002;43:806–810. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Boyd HL, Gunn RN, Marinho NV, Karwatowski SP, Bailey DL, Costa DC, Camici PG. Non-invasive measurement of left ventricular volumes and function by gated positron emission tomography. Eur J Nucl Med. 1996;23:1594–1602. doi: 10.1007/BF01249622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chatziioannou AF, Cherry SR, Shao Y, Silverman RW, Meadors K, Farquhar TH, Pedarsani M, Phelps ME. Performance evaluation of microPET: a high-resolution lutetium oxyorthosilicate PET scanner for animal imaging. J Nucl Med. 1999;40:1164–1175. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cherry SR, Shao Y, Silverman RW, Meadors K, Siegel S, Chatziioannou A, Young JW, Jones W, Moyers JC, Newport D, Boutefnouchet A, Farquhar TH, Andreaco M, Paulus MJ, Binkley DM, Nutt R, Phelps ME. MicroPET: a high resolution PET scanner for imaging small animals. IEEE Trans Nucl Sci. 1997;44:1161–1166. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schiller NB, Shah PM, Crawford M, DeMaria A, Devereux R, Feigenbaum H, Gutgesell H, Reichek N, Sahn D, Schnittger I. Recommendations for quantitation of the left ventricle by two-dimensional echocardiography. American Society of Echocardiography Committee on Standards, Subcommittee on Quantitation of Two-Dimensional Echocardiograms. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 1989;2:358–367. doi: 10.1016/s0894-7317(89)80014-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Huang H, Chan J, Wittner M, Jelicks LA, Morris SA, Factor SM, Weiss LM, Braunstein VL, Bacchi CJ, Yarlett N, Chandra M, Shirani J, Tanowitz HB. Expression of cardiac cytokines and inducible form of nitric oxide synthase (NOS2) in Trypanosoma cruzi-infected mice. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1999;31:75–88. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.1998.0848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cherry SR, Gambhir SS. Use of positron emission tomography in animal research. ILAR J. 2001;42:219–232. doi: 10.1093/ilar.42.3.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.De Souza AP, Tanowitz HB, Chandra M, Shtutin V, Weiss LM, Morris SA, Factor SM, Huang H, Wittner M, Shirani J, Jelicks LA. Effects of early and late verapamil administration on the development of cardiomyopathy in experimental chronic Trypanosoma cruzi (Brazil strain) infection. Parasitol Res. 2004;92:496–501. doi: 10.1007/s00436-004-1080-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Goldenberg RC, Jelicks LA, Fortes FS, Weiss LM, Rocha LL, Zhao D, Carvalho AC, Spray DC, Tanowitz HB. Bone marrow cell therapy ameliorates and reverses chagasic cardiomyopathy in a mouse model. J Infect Dis. 2008;197:544–547. doi: 10.1086/526793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hiller KH, Waller C, Haase A, Jakob PM. Magnetic resonance of mouse models of cardiac disease. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2008;185:245–257. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-77496-9_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Siri FM, Jelicks LA, Leinwand LA, Gardin JM. Gated magnetic resonance imaging of normal and hypertrophied murine hearts. Am J Physiol. 1997;272:H2394–H2402. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1997.272.5.H2394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Slawson SE, Roman BB, Williams DS, Koretsky AP. Cardiac MRI of the normal and hypertrophied mouse heart. Magn Reson Med. 1998;39:980–987. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910390616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chandra M, Tanowitz HB, Petkova SB, Huang H, Weiss LM, Wittner M, Factor SM, Shtutin V, Jelicks LA, Chan J, Shirani J. Significance of inducible nitric oxide synthase in acute myocarditis caused by Trypanosoma cruzi (Tulahuen strain) Int J Parasitol. 2002;32:897–905. doi: 10.1016/s0020-7519(02)00028-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tanowitz HB, Huang H, Jelicks LA, Chandra M, Loredo ML, Weiss LM, Factor SM, Shtutin V, Mukherjee S, Kitsis RN, Christ GJ, Wittner M, Shirani J, Kisanuki YY, Yanagisawa M. Role of endothelin 1 in the pathogenesis of chronic chagasic heart disease. Infect Immun. 2005;73:2496–2503. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.4.2496-2503.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rottman JN, Ni G, Brown M. Echocardiographic evaluation of ventricular function in mice. Echocardiography. 2007;24:83–89. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8175.2006.00356.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Scherrer-Crosbie M. Role of echocardiography in studies of murine models of cardiac diseases. Arch Mal Coeur Vaiss. 2006;99:237–241. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Litwin SE, Katz SE, Morgan JP, Douglas PS. Serial echocardiographic assessment of left ventricular geometry and function after large myocardial infarction in the rat. Circulation. 1994;89:345–354. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.89.1.345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tanaka N, Dalton N, Mao L, Rockman HA, Peterson KL, Gottshall KR, Hunter JJ, Chien KR, Ross J., Jr Transthoracic echocardiography in models of cardiac disease in the mouse. Circulation. 1996;94:1109–1117. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.94.5.1109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Coatney RW. Ultrasound imaging: principles and applications in rodent research. ILAR J. 2001;42:233–247. doi: 10.1093/ilar.42.3.233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chapon C, Jackson JS, Aboagye EO, Herlihy AH, Jones WA, Bhakoo KK. An in vivo multimodal imaging study using MRI and PET of stem cell transplantation after myocardial infarction in rats. Mol Imaging Biol. 2009;11:31–38. doi: 10.1007/s11307-008-0174-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gyöngyösi M, Blanco J, Marian T, Trón L, Petneházy O, Petrasi Z, Hemetsberger R, Rodriguez J, Font G, Pavo IJ, Kertész I, Balkay L, Pavo N, Posa A, Emri M, Galuska L, Kraitchman DL, Wojta J, Huber K, Glogar D. Serial noninvasive in vivo positron emission tomographic tracking of percutaneously intramyocardially injected autologous porcine mesenchymal stem cells modified for transgene reporter gene expression. Circ Cardiovas Imaging. 2008;1:94–103. doi: 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.108.797449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Handa N, Magata Y, Mukai T, Nishina T, Konishi J, Komeda M. Quantitative FDG-uptake by positron emission tomography in progressive hypertrophy of rat hearts in vivo. Ann Nucl Med. 2007;21:569–576. doi: 10.1007/s12149-007-0067-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stegger L, Schäfers KP, Flögel U, Livieratos L, Hermann S, Jacoby C, Keul P, Conway EM, Schober O, Schrader J, Levkau B, Schäfers M. Monitoring left ventricular dilation in mice with PET. J Nucl Med. 2005;46:1516–1521. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Osman S, Danpure HJ. The use of 2-[18F]fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose as a potential in vitro agent for labelling human granulocytes for clinical studies by positron emission tomography. Int J Rad Appl Instrum B. 1992;19:183–190. doi: 10.1016/0883-2897(92)90006-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kubota R, Yamada S, Kubota K, Ishiwata K, Tamahashi N, Ido T. Intra-tumoral distribution of fluorine-18-fluorodeoxyglu-cose in vivo: high accumulation in macrophages and granulocytes studied by microautoradiography. J Nucl Med. 1992;33:1972–1980. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kubota R, Yamada S, Kubota K, Ishiwata K, Tamahashi N, Ido T. Auto-radiographic demonstration of 18F-FDG distribution within mouse FM3A tumour tissue in vivo. Kaku Igaku. 1992;29:1215–1221. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Godino C, Messa C, Gianolli L, Landoni C, Margonato A, Cera M, Stefano C, Cianflone D, Fazio F, Maseri A. Multifocal, persistent cardiac uptake of [18-f]-fluoro-deoxy-glucose detected by positron emission tomography in patients with acute myocardial infarction. Circ J. 2008;72:1821–1828. doi: 10.1253/circj.cj-08-0046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Truijers M, Kurvers HA, Bredie SJ, Oyen WJ, Blankensteijn JD. In vivo imaging of abdominal aortic aneurysms: increased FDG uptake suggests inflammation in the aneurysm wall. J Endovasc Ther. 2008;15:462–467. doi: 10.1583/08-2447.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rudd JH, Myers KS, Bansilal S, Machac J, Pinto CA, Tong C, Rafique A, Hargeaves R, Farkouh M, Fuster V, Fayad ZA. Atherosclerosis inflammation imaging with 18F-FDG PET: carotid, iliac, and femoral uptake reproducibility, quantification methods, and recommendations. J Nucl Med. 2008;49:871–878. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.107.050294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]