Abstract

Background

Interleukin 6 (IL-6) activates Th17 cells and regulates the response of B-lymphocytes and T regulatory cells. The IL-6 receptor and the membrane protein, gp130, form an active signaling complex that signals through STAT3 and other signaling molecules. Both the IL-6 receptor (IL-6R) and gp130 can be found in soluble forms that regulate the pathway.

Objective

We measured IL-6 signaling components and IL-17 in chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps (CRSwNP), CRS without nasal polyps (CRSsNP) and controls to assess the IL-6 pathway in CRS.

Methods

IL-6, soluble IL-6R (sIL-6R), soluble gp130 (sgp130), and IL-17 were measured in sinus tissue extracts and in nasal lavage fluid by either cytokine bead array or ELISA. phosphoSTAT3 (p-STAT3) was determined by western blot and by immunohistochemistry.

Results

IL-6 protein was significantly (p<0.001) increased in CRSwNP compared to CRSsNP and controls. sIL-6R was also increased in nasal polyp compared to control tissue (p<0.01). Despite elevated IL-6 and sIL-6R, IL-17A, E, and F were undetectable in the sinus tissue from most of the patients with CRS and controls. p-STAT3 levels were reduced in the polyp tissue, possibly indicating reduced activity of IL-6 in the tissue. sgp130 was elevated in CRSwNP compared to CRSsNP and controls.

Conclusion

p-STAT3 levels are decreased in CRSwNP despite increased levels of IL-6 and sIL-6R and are associated with the absence of an IL-17 response. This may be a response to elevated levels of sgp130, a known inhibitor of IL-6 signaling. These results indicate that IL-6 and its signaling pathway may be altered in CRSwNP.

Clinical implications

The IL-6 signaling pathway may have a pathogenic role in CRSwNP.

Keywords: Chronic rhinosinusitis, Nasal polyps, Interleukin 6, IL-6 receptor, Soluble glycoprotein 130, Interleukin 17, Phospho STAT3

INTRODUCTION

Chronic rhinosinusitis (CRS) is a common clinical syndrome characterized by inflammation of the mucosa of the nose and the paranasal sinuses (1). This disorder is typically classified into CRS with nasal polyps (CRSwNP) and CRS without NP (CRSsNP). The etiology and pathogenesis of CRS is a matter of vigorous debate but bacteria, viruses and fungi have all been implicated in the establishment of the inflammatory process (2,3,4,5). Abnormalities in host response to these common agents, including defective cytokine and chemokine signaling of the nasal mucosa, have been suggested to underlie the persistence of the inflammatory state (6).

In the present study, we investigated the role in CRS of interleukin-6 (IL-6), a cytokine implicated in the pathogenesis of various inflammatory diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis, Crohn’s disease, lupus, and asthma (7,8,9,10,11). Early studies using RT-PCR and immunohistochemistry techniques indicated that IL-6 expression was increased in CRS (12,13,14,15,16,17,18). A recent report demonstrated elevated IL-6 protein in polyp tissue compared to middle turbinate in the same patients with CRSwNP (19). Although, IL-6 has been proposed as a marker of inflammation in CRS, the role of IL-6 in CRS is not well defined. The published studies did not differentiate between CRSwNP and CRSsNP and none investigated the presence of IL-6 signaling components or the activation of upper airway tissue by IL-6.

IL-6 binds a specific 80-kDa receptor, (IL-6R, CD126) and then the complex associates with the 130-kDa signal-transducing molecule, glycoprotein 130 (gp130, CD130) (20,21). In general, the IL-6R is found primarily on hepatocytes and lymphocytes, however, gp130 is ubiquitously present on many cell types (22,23). IL-6 can affect gp130 positive cells that do not express the IL-6 receptor by binding to a 50-kDa soluble IL-6 receptor (sIL-6R) that can complex with membrane bound gp130. This pathway has been termed “trans-signaling”, enabling IL-6 to regulate cells that would otherwise not respond to IL-6 since they lack the cognate IL-6R (24). A soluble form of gp130 (sgp130) can inhibit trans-signaling by blocking the association of the IL-6/sIL-6R complex to the membrane bound gp130 but does not inhibit signaling through the cell surface IL-6R (25,26).

Because of the potential importance of IL-6 in the pathogenesis of inflammatory diseases, we examined the distribution of IL-6 protein and the trans-signaling components in CRS tissue and cultured epithelial cells from CRS patients. We also evaluated the level of activation of STAT3, an IL-6 activated transcription factor, in sinonasal tissue. Since IL-6 is now known to be important in IL-17 production, we further extended our analysis and examined IL-17 production in CRS tissue (27,28). To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to evaluate the IL-6 signaling pathway in CRS. Our results indicate increased levels of several components of the IL-6 pathway in sinus mucosa from patients with CRSwNP and CRSsNP. Interestingly, we detected evidence that IL-6 signaling may actually be blunted in nasal polyp tissue, based on reduced level of phosphorylation of STAT3 and increased sgp130.

METHODS

Subjects and specimens

Sinonasal tissue and nasal lavage fluid were collected from subjects with CRSsNP and CRSwNP undergoing functional endoscopic sinus surgery. All subjects met the criteria for CRS as defined by the Sinus and Allergy Health Partnership (1). All subjects had symptoms for 12 weeks or greater and had failed medical therapy. The presence of sinusitis or bilateral nasal polyps was confirmed by office endoscopy and sinus CT scans. Most of the subjects were skin tested prior to the procedure to pollens, dust-mites, pets, molds, and cockroach using Hollister Stier Canada (Toronto, ON) extracts. Further details are described in the subject selection section in the Online Repository at www.jacionline.org. The Lund-Mackay scoring system (0–24) was used to grade the radiographic severity of sinus disease (29). Clinical characteristics of subjects undergoing IL-6, sIL-6R, and sgp130 analyses in the sinus tissue are presented in Table I. Detailed subject characteristics are also presented in tables in the Online Repository at www.jacionline.org.

Table I.

Clinical characteristics of subjects undergoing IL-6, sIL-6R, and/or sgp130 analyses in the sinus tissue

| CRSwNP | CRSsNP | Controls | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Subject number | 38 | 30 | 18 |

| Age, years (range) | 42 (22–70) | 39 (26–61) | 41 (26–71) |

| Gender | 17M/21F | 14M/16F | 11M/7F |

| Race-no (%) | |||

| -Caucasian | 26 (68) | 26 (87) | 13(72) |

| -African American | 6 (16) | 2 (7) | 1 (5) |

| -Asian | 0 | 1 (3) | 1 (5) |

| -Hispanic | 3 (8) | 0 | 0 |

| -Other | 3 (8) | 1(3) | 3 (17) |

| Atopic | 23 | 13 | 2 |

| Non atopic | 11 | 11 | 10 |

| Atopy status unknown | 4 | 6 | 6 |

| Asthma | 19 | 5 | 0 |

| Aspirin intolerance | 0 | 0 | 0 |

CRSwNP: chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps; CRSsNP: chronic rhinosinusitis without nasal polyps; M: Male; F: Female

The control specimens included inferior turbinate tissue from individuals without history of CRS or asthma who were undergoing sinonasal surgery for unrelated reasons (e.g. skull base tumor, cosmetic rhinoplasty, facial fracture). Nasal lavage was collected from control subjects without history of allergic rhinitis, CRS or asthma. The Institutional Review Board of Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine approved the study protocol and all subjects gave signed informed consent.

Measurement of IL-6, sIL-6R, sgp130, and IL-17A, E, and F in tissue and nasal lavage fluid

Extracts of sinonasal tissue or polyps were prepared by addition of 1 ml of PBS-Tween 20 at 4°C to freshly obtained or fresh-frozen polyp/tissue samples. A cocktail of protease inhibitors (PIC) purchased from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, MO) was added to the samples in a 1:100 dilution (10 ul). The polyp/tissue samples were mechanically minced with a scalpel on ice and then homogenized for 30–60 seconds on ice with an IKA-WERKE Ultra-Turrax T8 Homogenizer. The suspensions were then centrifuged at 4,000 rpm for 20 minutes at 4°C. The tissue extracts were collected and stored at −20 C until use. Nasal lavage was performed by instilling 5 ml of warmed sterile PBS into each nostril, holding for 10 seconds and then expelling into a container. Of the 5 ml used for the nasal lavage, the recovery was about 3–4ml. Samples were concentrated 2-fold using Centriplus YM-10 filters (Millipore, Bedford, MA) and stored at −80°C until analyzed. Levels of IL-6 protein were determined by cytometric bead array assay (BD Biosciences, San Diego, CA). Levels of sIL-6R and sgp130 were determined by ELISA (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN). According to the sIL-6R kit, the soluble form arises from proteolytic cleavage of membrane-bound IL-6R. The minimal detection limits for IL-6, sIL-6R, and sgp 130 are 20 pg/ml, 31.2 pg/ml, and 0.125 ng/ml respectively. IL-17A, E, and F concentrations were determined by ELISA (IL-17A and F from R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, and IL-17E from PeproTech, Rocky Hill, NJ). The minimal detection limits for these kits are 31.2 pg/ml, 31.2 pg/ml, and 78 pg/ml respectively. Zero value was taken when the samples were under the detection limit. All results were normalized to total protein content in the extracts as determined by the Bio-Rad protein assay kit (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA).

Cell culture and Immunohistochemistry

The methods for primary nasal epithelial cell (PNEC) culture and immunohistochemistry are described in the Online Repository at www.jacionline.org.

Nasal tissue protein extraction and western blot

The methods are described in the Online Repository.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical comparisons were performed by non-parametric analysis using the Mann-Whitney U test and a value of p<0.05 was accepted as being statistically significant.

RESULTS

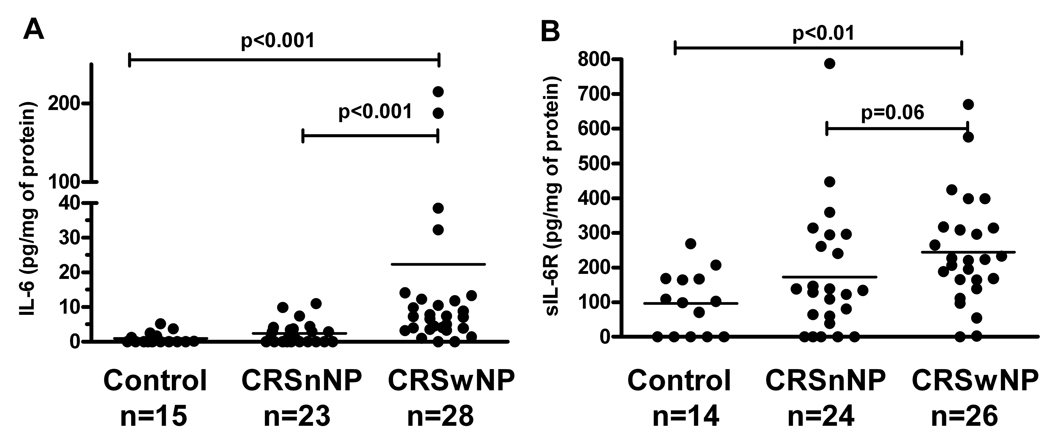

Clinical and epidemiologic data are shown in Tables I, and online Tables I, II, III, and IV in the Online Repository at www.jacionline.org. The mean Lund-MacKay scores were 14.7±1 and 9.7±1 in the CRSwNP and CRSsNP groups respectively. Levels of IL-6 protein detected in nasal polyp extracts (21.5 ± 50.7 pg/mg of protein; mean ± SD) were significantly increased compared to levels in sinonasal tissue extracts from individuals with CRSsNP (1.7 ± 2.1 pg/mg of protein) and levels in controls (0.7 ± 1.2 pg/mg of protein); p<0.001 (Figure 1A). There was no statistically significant difference observed in the levels of IL-6 comparing the tissue from CRSsNP patients versus controls. There was no difference in the IL-6 levels from the nasal lavage fluid from individuals with CRSwNP (47±114 pg/mg) compared to controls (12±18 pg/mg); p=0.27 (Figure E1A in the Online Repository).

Figure 1.

Assessment of IL-6 and soluble IL-6 receptor (sIL-6R) levels in CRS by ELISA. A, IL-6 levels were increased in nasal polyps compared to sinus tissues from controls and CRSsNP. B, sIL-6R levels were increased in the polyp tissue compared to sinus tissue from controls. Levels were marginally increased (p=0.06) in CRSwNP compared to CRSsNP.

Levels of sIL-6R were higher in the polyp tissue compared to control tissue (p<0.01) and marginally higher compared to sinonasal tissue from CRSsNP patients (p=0.06). CRSsNP tissue did not have elevated levels of sIL-6R levels compared to controls (Figure 1B). sIL-6R was detectable in the nasal lavage but the differences between the groups were not significant (Figure E1B). In order to determine whether there is an intrinsic increase in either basal or stimulated IL-6 release in cells from patients with CRSwNP, cultured epithelial cells from the inferior turbinate and uncinate process of patients with CRSwNP, CRSsNP, and controls were challenged with either medium alone or the TLR3 ligand, dsRNA. Data in Figure E2 in the Online Repository show that baseline levels of IL-6 secreted by epithelial cells from the inferior turbinate (A) or uncinate process (B) from CRS and control subjects were not significantly different. Although there was a trend for greater activation of IL-6 production by stimulation with dsRNA in both CRS groups, the values were not different among the three groups of subjects.

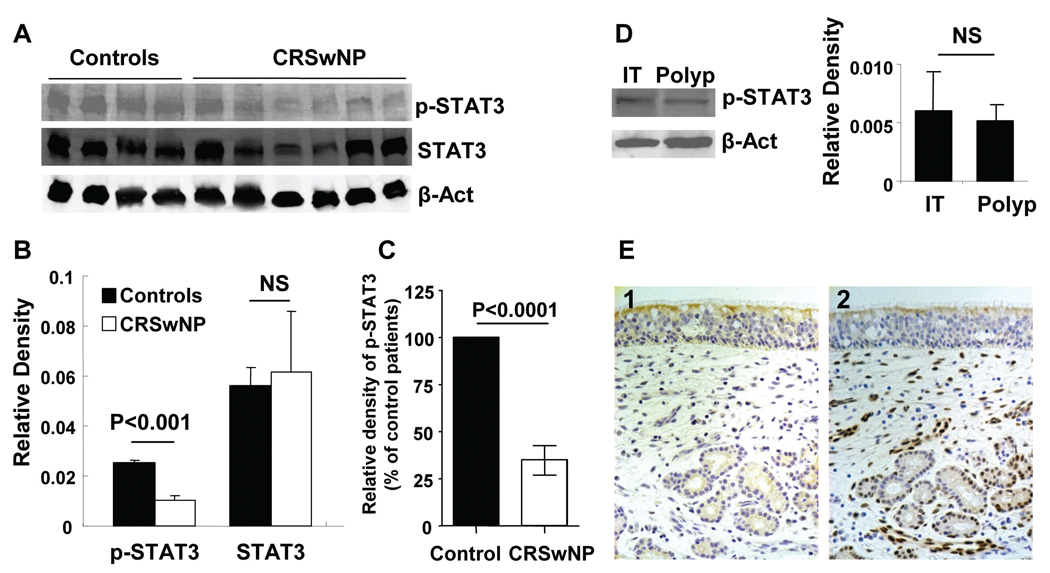

Since tissue extracts from CRSwNP subjects had significantly elevated levels of both IL-6 and sIL-6R, we hypothesized that both direct and trans-signaling may occur and that the sinonasal tissue from patients with CRSwNP would manifest evidence of activation by IL-6. One of the major pathways by which IL-6 activates the inflammatory response is by receptor-mediated phosphorylation and activation of the transcription factor, STAT3 (30). We therefore analyzed the presence of total STAT3 and the phosphorylated form of STAT3 (p-STAT3) in nasal polyps and control tissue. Figure 2A demonstrates a representative western blot showing that polyp tissue did not have increased STAT3 phosphorylation and may actually have reduced levels of p-STAT3 when compared to control tissue. Figure 2B displays densitometric analysis of p-STAT3 in the subjects shown in Figure 2A and shows that levels of total STAT3 were not different but p-STAT3 levels were lower in nasal polyps compared to control tissue. We pooled p-STAT3 data from four separate experiments. Normalized values for CRSwNP subjects were converted to a percent of control subjects’ values. Levels of p-STAT3 in polyp tissue from CRSwNP subjects with high IL-6 levels were significantly lower than from normal control tissue (Figure 2C). Since the tissue used from CRSwNP patients was polyp tissue and the tissue in controls was inferior turbinate tissue, we compared polyp and inferior turbinate tissue from three subjects with CRSwNP. Data in figure 2D show that levels of p-STAT3 were similar in tissue from both locations. Figure 2E (2) shows representative staining for p-STAT3 in uncinate tissue from a control subject. We performed immunohistochemistry in tissue samples from 5 CRSwNP subjects and 4 controls. We counted the number of p-STAT3 positive cells using a semi-quantitative method. Although p-STAT3 positive cells were decreased in the epithelium (3200±900 cells/mm2) from polyp tissue compared to the epithelium of uncinate from controls (4300±2000 cells/mm2), this difference was not significant. This may be due to the small number of samples and also because p-STAT3 was highly expressed in the epithelium of both the polyp tissue and the uncinate tissue from normal controls. Epithelial p-STAT3 positive cells were not evenly distributed throughout the tissue; they were observed mostly in clusters. In the figure shown, there is no such epithelial cluster present. The positive cells counts in the lamina propria were 1300±500 cells/mm2 in the normal control tissue and 1000±100 cells/mm2 in the polyp tissue.

Figure 2.

A, Representative western blot of p-STAT3 and total STAT3 in nasal polyps and controls. B, Densitometric analysis of p-STAT3 from four controls and six CRSwNP subjects shown in A. C, Densitometric analysis of p-STAT3 from seven controls and nine CRSwNP subjects. D, Representative western blot of p-STAT3 in nasal polyp (n=3) and inferior turbinate tissue (n=3) within the same CRSwNP patients. E, (1) Isotype control antibody staining in control tissue. (2) Representative immunostaining for p-STAT3 in control tissue.

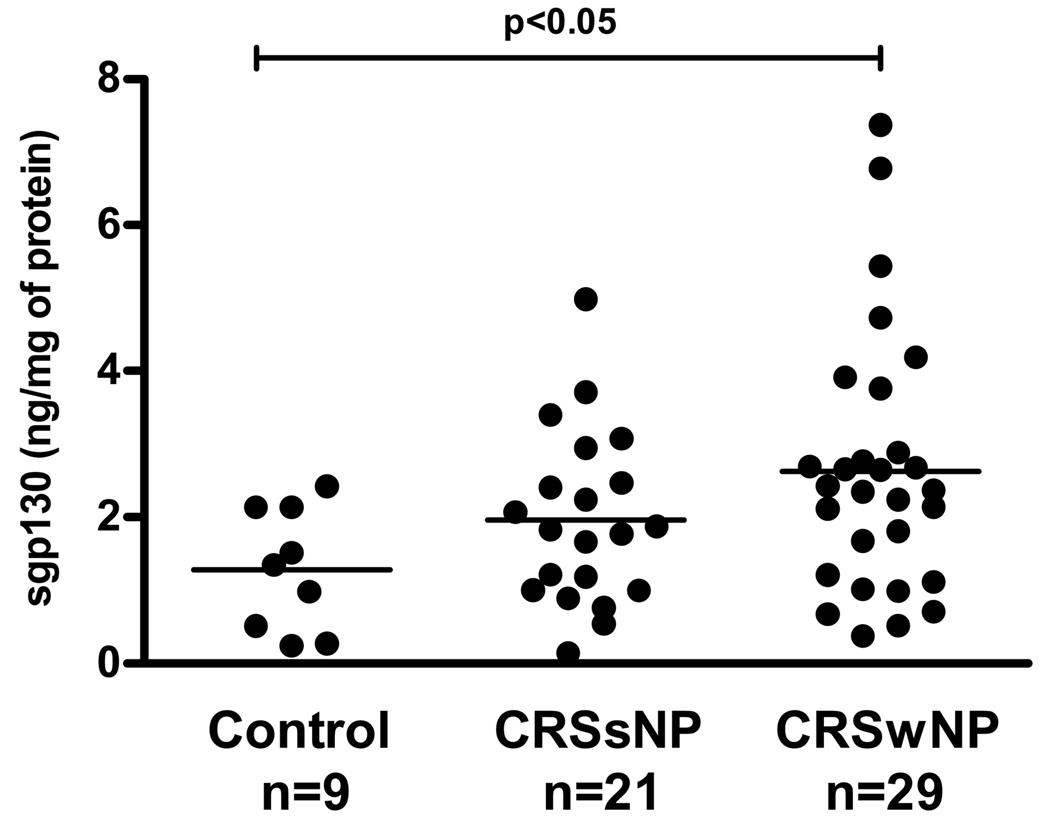

These studies suggest that there is constitutive STAT3 activation in normal tissue and that there is no evidence that elevated levels of IL-6 and sIL-6R lead to additional activation of STAT3 in the sinonasal tissue of CRSwNP patients. To the contrary, reduced STAT3 phosphorylation suggests reduced levels of signaling via this pathway. To investigate this further, we assayed levels of the inhibitory signaling factor, sgp130 in tissue extracts. Levels of sgp130 were significantly elevated in the polyp tissue compared to the sinus tissue from controls (p=0.016) but not when compared to the sinus tissue from CRSsNP individuals (p=0.19) as shown in Figure 3. The levels of sgp130 were not different in the sinus tissue extracts from CRSsNP subjects versus controls. sgp130 was detected in the nasal lavage fluid in all subject groups; however, we did not observe a significant difference among the three groups (Figure E3 in the Online Repository).

Figure 3.

Soluble glycoprotein 130 (sgp130) levels are increased in polyp tissue compared to sinus tissue from controls by ELISA.

Since IL-6 plays a pivotal role in the development of Th17 cells from naïve T cells we investigated the presence of IL-17 in CRS tissue (Figure E4 in the Online Repository). IL-17A, IL-17E, and IL-17 F were undetectable in all but two of the CRS and control tissues. To test stability in tissue extracts, we added IL-17A, E, or F to tissue extracts, and incubated them overnight at 4°C. We failed to find evidence that the tissue extracts degraded the cytokines (data not shown). We also assessed IL-23, a member of the IL-12 family that is important in Th17 cell differentiation. Similar to IL-6, STAT3 activation is required in IL-23 dependent Th17 differentiation. IL-23 protein was undetectable in the sinus tissue in most patients with CRS and controls (data not shown).

There was significant variability in the results as shown on the graphs and there was no correlation between IL-6 and its signaling components. We did subgroup analysis of allergic and non-allergic subjects within the study groups. There were no differences in the levels of IL-6, sIL-6R or sgp130 when comparing allergic versus non-allergic CRSwNP subjects. Similarly, no significant differences were observed in the levels of IL-6, sIL-6R or sgp130 in the sinus tissue from CRSwNP patients with and without asthma (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

The present study demonstrates that the IL-6 pathway may be altered in CRS tissue. We found increased levels of IL-6, sIL-6R and sgp130 proteins in nasal polyp tissue compared to extracts of sinus tissue from normals or CRSsNP. Although there are reports of increased IL-6 mRNA and increased immuno-histochemical staining for IL-6 in CRS, this is the first report of elevated levels of IL-6 and sIL-6R protein in CRSwNP compared to CRSsNP (16,17,18,19). Despite elevations of IL-6 and sIL-6R in CRSwNP, we observed reduced p-STAT3 levels in CRSwNP, suggesting that the signaling pathway may be blunted. Increased levels of sgp130, a signaling chain known to have inhibitory effects on IL-6 signaling, could help explain the reduced levels of p-STAT3 in nasal polyps. Although the cellular source of IL-6, sIL-6R and sgp130 is unknown, we found that nasal epithelial cells from patients with CRSwNP did not produce elevated levels of IL-6 in vitro.

Elevations of IL-6 and sIL-6R suggest that IL-6 plays a pathogenic role in CRS. Proinflammatory effects of IL-6/sIL-6R and IL-6 trans-signaling have been implicated in the transition of acute innate immune responses to adaptive chronic inflammatory reactions (31). IL-6 inhibits neutrophil recruitment during innate immune responses and enhances apoptosis of granulocytes (32,33,34). In adaptive immune responses, IL-6 trans-signaling is critical for T cell recruitment and survival (35). In RA, IL-6 and sIL-6R concentrations are increased in the synovial fluid and directly correlate with leukocyte influx into the joint (36). Inhibition of T cell apoptosis via IL-6 trans-signaling is believed to be responsible for the persistent T cell dependent inflammation in the colon that is characteristic of Crohn’s disease (37). Similar resistance of T cells to apoptosis following IL-6 trans-signaling has been demonstrated in the inflammatory eye disease, uveitis (38). It is possible that the increased levels of IL-6 and its soluble receptor in the polyp tissue that we report here may be partially responsible for the recruitment and retention of T cells that have been observed in CRS (2,39,40,41).

We also examined IL-17 in the sinus tissue because IL-6 is important in Treg and Th17 differentiation (42, 43). IL-17 producing Th17 cells are important in mucosal defense against extracellular organisms and are also involved in autoimmune diseases such as RA and Crohn’s disease (44,45,46,47). Tregs on the other hand are important in preventing autoimmunity. The transcription factor Foxp3 promotes Treg conversion from Th cells and inhibits retinoic acid-related orphan receptor (RORγt)-induced Th17 differentiation (48,49). IL-6 has been shown to inhibit Foxp3, which in turn leads to diminished inhibition of RORγt and consequently expansion of Th17 cells (50,51,52). Pasare and colleagues have demonstrated Toll like receptor-dependent suppression of Treg activity by IL-6 produced by dendritic cells (53). There is very limited literature regarding the role of Treg and Th17 cells in CRS. Potentially, the increased levels of IL-6 and its soluble receptor in the polyps may be inhibiting Treg activity in CRSwNP. According to Bachert and colleagues, TGFβ, a cytokine implicated in Treg formation and activity, and Foxp3 mRNA are decreased in CRSwNP compared to CRSsNP and controls (2,54). In terms of Th17 cells, Molet et al. demonstrated increased expression of IL-17 in nasal polyps compared to normal control tissue by in situ hybridization and Wang et al. detected IL-17 and IL-17 receptor expression in nasal polyps by immuno-histochemical staining and western blot analyses (55,56). Bachert and colleagues failed to find a difference in IL-17 mRNA expression among patients with chronic sinusitis with or without polyps and controls (54). However, recently they reported an increase in IL-17A protein, which is responsible for neutrophil recruitment and activation, in polyp tissue from Chinese patients compared to Belgian patients with nasal polyps (57). This is most likely because polyps from Chinese patients tend to be neutrophilic compared to polyps from Western patients that tend to be eosinophilic. They did not investigate IL-17E, which is important in the Th2 pathway and eosinophil recruitment. In our study of IL-17 protein, we did not detect high levels of IL-17 nor did we find a difference in levels of IL-17A, E, or F between CRSwNP, CRSsNP or control tissues. Most of the samples yielded values below the level of detection, suggesting that if IL-17 is present in the polyp or sinus tissue, the quantity is small. Blunted IL-6 signaling, as indicated by reduced tissue p-STAT3 and increased sgp130, may be responsible for a local tissue environment unfavorable to the development of Th17 cells in CRS. Although it would be appealing to correlate IL-6 and sIL-6R with IL-17 in our sample sets, it is unlikely that we would find correlations since so few samples had detectable levels of IL-17.

Any reduction of local IL-17 production could result in susceptibility to infections that are associated with CRS. Holland and colleagues have recently described mutations in the gene encoding STAT3 and defective IL-6 signaling in hyper-IgE syndrome (HIES) (58). HIES is characterized by recurrent sinopulmonary infections, eosinophilia, eczema, and high IgE. Mutations in the DNA binding or SH2 regions of STAT3 are thought to lead to absent IL-17 production by T cells in HIES (59). The low IL-17 in turn is suggested to elevate risk for the recurrent infections seen in these patients. Although HIES is a systemic immunodeficiency syndrome, CRSwNP shares certain features, as it is frequently characterized by elevated local IgE, eosinophilia and colonization by S. aureus. (2,60,61,62,63,64,65,66). We speculate that the reduced local activation of STAT3 that we demonstrated here in polyps may promote this phenotype in the sinonasal mucosa. Future studies are required to determine whether the increased staphylococcal colonization, eosinophilia and local IgE observed in CRSwNP occurs as a result of local STAT3 mutations in the sinus tissue.

In addition to effects on T cells, alterations in IL-6 signaling may influence the recruitment and activation of B cells in CRS. Bachert and colleagues have identified lymphoid follicle-like structures containing T cells, B cells and plasma cells in CRSwNP (66). In transgenic mice, over-expression of IL-6 leads to profound formation of lymphoid structures in the lungs (67). Infiltration or recruitment of B cells and local production of IgE and possibly IgA are believed to be responsible for the local inflammation seen in both allergic and non-allergic airway diseases. IL-6 is a potent B cell growth factor and important for antibody synthesis and secretion. The local increase in IL-6 and its soluble receptor in the polyp tissue may contribute to the local formation of B cell rich follicles and production of IgE in the polyps (66). We have recently observed increased levels of the B cell activating factor of the TNF family, BAFF in nasal polyp tissue (68). Working together, BAFF and IL-6 may potentially expand and activate B cells in the sinuses of patients with CRS.

Limited tissue quantity made it unfeasible to assess all the analytes in all of the subjects. Other limitations in our study include lack of atopy information in some of the subjects and lack of smoking data in the subjects. In addition, glucocorticoids are known to affect IL-6 production and a weakness of our study is that we did not control for prior glucocorticoid use.

In conclusion, we have provided novel data suggesting that there may be important alterations in the IL-6 signaling pathway in CRSwNP. Since we have found elevations in both pro-stimulatory and down regulatory molecules, it is not possible yet to conclude whether the IL-6 pathway is inappropriately activated or blunted in CRSwNP; based upon our findings that pSTAT3 levels are lower in samples from patients, we suspect the latter, although responses may vary among different cell types. Over-activity of the IL-6 pathway due to increased IL-6 and sIL-6R could increase Th2 inflammation and disable T regulatory cell responses, contributing to the persistence of chronic inflammation that is characteristic of CRSwNP. On the other hand, if the elevated levels of the inhibitor sgp130 are dominant and STAT3 phosphorylation is blunted in T cells, T regulatory responses may be excessive and Th17 responses may be reduced, rendering adaptive immune responses inadequate and inappropriately skewed to Th2. Further investigations will be required to identify the cellular sources of IL-6, sIL-6R and sgp130 as well as the impact of these molecules on disease pathogenesis in CRSwNP.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding: This research was supported in part by NIH grants, R01 HL068546, R01 HL078860 and 1R01 AI072570 and by a grant from the Ernest S. Bazley Trust.

Abbreviations

- CRS

Chronic rhinosinusitis

- CRSwNP

CRS with nasal polyps

- CRSsNP

CRS without nasal polyps

- IL-6

interleukin 6

- IL-6R

interleukin 6 receptor

- sIL-6R

soluble interleukin 6 receptor

- sgp130

soluble glycoprotein 130

- p-STAT3

phospho STAT3

- BAFF

B cell-activating factor of the TNF family

- RORγt

retinoic acid-related orphan receptor

- HIES

hyper-IgE syndrome

- S. aureus

Staphylococcus aureus

- PNEC

primary nasal epithelial cells

- IT

inferior turbinate

- UT

uncinate tissue

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Meltzer E, Hamilos DA, Hadley JA, Lanza DC, Marple BF, Nicklas RA, et al. Rhinosinusitis: Establishing definitions for clinical research and patient care. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;114:S155–S212. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2004.09.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Van Zele T, Claeys S, Gevaert P, Van Maele G, Holtappels G, Van Cauwenberge, et al. Differentiation of chronic sinus diseases by measurement of inflammatory mediators. Allergy. 2006;61:1280–1289. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2006.01225.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bachert C, Gevert P, van Cauwenberge P. Staphylococcus aureus superantigens and airway disease. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2002;2:252–258. doi: 10.1007/s11882-002-0027-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shin SH, Ponikau JU, Sherris DA, Congdon D, Frigas E, Homburger HA, et al. Chronic rhinosinusitis: an enhanced immune response to ubiquitous airborne fungi. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;114:1369–1375. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2004.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kramer MF, Ostertag P, Pfrogner E, Rasp G. Nasal interleukin-5, immunoglobulin E, eosinophilic cationic protein, and soluble intercellular adhesion molecule-1 in chronic sinusitis, allergic rhinitis, and nasal polyposis. Laryngoscope. 2000;110:1056–1062. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200006000-00031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kern RC, Conley DB, Walsh W, Chandra R, Kato A, Peters AT, et al. Perspectives on the etiology of chronic rhinosinusitis: An immune barrier hypothesis. Am J Rhinol. 2008;22(6):549–559. doi: 10.2500/ajr.2008.22.3228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hirano T, Matsuda T, Turner M, Miyasaka N, Buchan G, Tang B, et al. Excessive production of interleukin 6/B cell stimulatory factor –2 in rheumatoid arthritis. Eur J Immunol. 1988;18:1797–1801. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830181122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Houssiau FA, Devogelaer J, Van Damme J, de Deuxchaisnes CN, Van Snick J. Interleukin-6 in synovial fluid and serum of patients with rheumatoid arthritis and other inflammatory arthritides. Arthritis Rheum. 1988;31:784–788. doi: 10.1002/art.1780310614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Atreya R, Mudter J, Finotto S, Mullberg J, Jostock T, Wirtz S, et al. Blockade of interleukin 6 trans signaling suppresses T-cell resistance against apoptosis in chronic intestinal inflammation: Evidence in Crohn’s disease and experimental colitis in vivo. Nat Med. 2000;6:583–588. doi: 10.1038/75068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Doganci A, Eigenbrod T, Krug N, De Sanctis GT, Hausding M, Erpenbeck VJ, et al. The IL-6Rα chain controls lung CD4+CD25+ Treg development and function during allergic airway inflammation in vivo. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:313–325. doi: 10.1172/JCI22433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Polgar A, Brozik M, Toth S, Holub M, Hegyi K, Kadar A, et al. Soluble interleukin-6 receptor in plasma and in lymphocyte culture supernatants of healthy individuals and patients with systemic lupus erythematosus and rheumatoid arthritis. Med Sci Monit. 2000;6:13–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Osada R, Takeno S, Hirakawa K, Ueda T, Furukido K, Yajin K. Expression and localization of nuclear factor-kappa B subunits in cultured human paranasal sinus mucosal cells. Rhinol. 2003;41(2):80–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Saito H, Asakura K, Ogasawara H, Watanabe M, Kataura A. Topical antigen provocation increases the number of immunoreactive IL-4, IL-5, and IL-6-positive cells in the nasal mucosa of patients with perennial allergic rhinitis. Int Arch All Immunol. 1997;114:81–85. doi: 10.1159/000237647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gaffar O, Lavigne F, Kamil A, Renzi P, Hamid Q. Interleukin-6 expression in chronic sinusitis: colocalization of gene transcripts to eosinophils, macrophages, T lymphocytes, and mast cells. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1998;118:504–511. doi: 10.1016/s0194-5998(98)70209-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bradley DT, Kountakis SE. Role on interleukins and transforming growth factor-β in chronic rhinosinusitis and nasal polyposis. Laryngoscope. 2005;115:684–686. doi: 10.1097/01.mlg.0000161334.67977.5D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kuehnemund M, Ismail C, Brieger J, Schaefer D, Mann WJ. Untreated chronic rhinosinusitis: a comparison of symptoms and mediator profiles. Laryngoscope. 2004;114:561–565. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200403000-00032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Min YG, Lee CH, Rhee CS, Hong SK, Kwon SH. Increased expression of IL-4, IL-5, IFN-gamma, IL-6, IL-8, and TGF-beta mRNAs in maxillary mucosa of patients with chronic sinusitis. Am J Rhinol. 1999;13:339–343. doi: 10.2500/105065899781367546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lennard CM, Mann EA, Sun LL, Chang AS, Bolger WE. Interleukin-1 beta, interleukin-5, interleukin-6, interleukin-8, and tumor necrosis factor-alpha in chronic sinusitis: response to systemic corticosteroids. Am J Rhinol. 2000;14:367–373. doi: 10.2500/105065800779954329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Danielsen A, Tynning T, Krokstad, Olofsson J, Davidsson A. Interleukin 5, IL6, IL12, IFNγ, RANTES, and fractalkine in human nasal polyps, turbinate mucosa and serum. Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2006;263:282–289. doi: 10.1007/s00405-005-1031-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mackiewicz A, Schooltink H, Heinrich PC, Rose-John S. Complex of soluble human IL- 6 receptor/IL-6 up-regulates expression of acute-phase proteins. J Immunol. 1992;149:2021–2027. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Taga T, Hibi M, Hirata Y, Yamasaki K, Yasukawa K, Matsuda T, et al. Interleukin-6 triggers the association of its receptor with a possible signal transducer, gp130. Cell. 1989;58:573–581. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90438-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Taga T. IL-6 signaling through IL-6 receptor and receptor-associated signal transducer, gp130. Res Immunol. 1992;143:737–739. doi: 10.1016/0923-2494(92)80013-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Saito M, Yoshida K, Hibi M, Taga T, Kishimoto T. Molecular cloning of a murine IL-6 receptor-associated signal transducer, gp130, and its regulated expression in vivo. J Immunol. 1992;148:4066–4071. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jones SA, Rose-John S. The role of soluble receptors in cytokine biology: the agonistic properties of the sIL-6R/IL-6 complex. Biochem Biophys Acta. 2002;1592:251–253. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4889(02)00319-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Narazaki M, Yasukawa K, Saito T, Ohsugi Y, Fukui H, Koishihara Y, et al. Soluble forms of the interleukin-6 signal transducing receptor component gp130 in human serum possessing a potential to inhibit signals through membrane anchored gp130. Blood. 1993;82:1120–1126. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jostock T, Mullberg J, Ozbek S, Atreya R, Blinn G, Voltz N, et al. Soluble gp130 is the natural inhibitor of soluble interleukin-6 receptor trans-signaling responses. Eur J Biochem. 2001;268:160–167. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.2001.01867.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhou L, Ivanov II, Spolski R, Min R, Shenderov E, Egawas T, et al. IL-6 programs Th-17 cell differentiation by promoting sequential engagement of the IL-21 and IL-23 pathways. Nature Immunol. 2007;8(9):967–974. doi: 10.1038/ni1488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Acosta-Rodriguez EV, Napolitani G, Lanzavecchia A, Sallusto F. Interleukins 1β and 6 but not transforming growth factor-β are essential for the differentiation of interleukin 17-producing human T helper cells. Nature Immunol. 2007;8(9):942–949. doi: 10.1038/ni1496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lund VJ, MacKay IS. Staging in rhinosinusitis. Rhinology. 1993;31:183–184. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhong Z, Wen Z, Darnell JE., Jr. Stat3: a STAT family member activated by tyrosine phosphorylation in response to epidermal growth factor and interleukin-6. Science. 1994;264:95–98. doi: 10.1126/science.8140422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jones SA. Directing transition from innate to acquired immunity: defining a role for IL-6. J Immunol. 2005;173:3463–3468. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.6.3463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kaplanski G, Marin V, Montero-Julian F, Mantovani A, Farnarier C. IL-6: a regulator of the transition from neutrophil to monocyte recruitment during inflammation. Trends in Immunology. 2003;24(1):25–29. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4906(02)00013-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hurst SM, Wilkinson TS, McLoughlin RM, Jones S, Horiuchi S, Yamamoto N, et al. IL-6 and its soluble receptor orchestrate a temporal switch in the pattern of leukocyte recruitment seen during acute inflammation. Immunity. 2001;14:705–714. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(01)00151-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Afford SC, Pongracz J, Stockley RA, Crocker J, Burnett D. The induction by human interleukin-6 of apoptosis in the promonocytic cell line U937 and human neutrophils. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:21612–21616. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Romano M, Sironi M, Toniatti C, Polentarutti N, Fruscella P, Ghezzi P, et al. Role of IL-6 and its soluble receptor in induction of chemokines and leukocyte recruitment. Immunity. 1997;6:315–325. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80334-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Desgeorges A, Gabay C, Silacci P, Novick D, Roux-Lombard P, Grau G, et al. Concentrations and origins of soluble interleukin 6 receptor-α in serum and synovial fluid. J Rheumatol. 1997;24:1510–1516. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yamamoto M, Yoshizaki K, Kishimoto T, Ito H. IL-6 is required for the development of Th1 cell-mediated murine colitis. J Immunol. 2000;164:4878–4882. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.9.4878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Curnow SJ, Scheel-Toellner S, Jenkinson W, Raza K, Durrani OM, Faint JM, et al. Inhibition of T cell apoptosis in the aqueous humor the patients with uveitis by IL-6/soluble IL-6 receptor trans-signaling. J Immunol. 2004;173:5290–5297. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.8.5290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Morinaka S, Nakamura H. Inflammatory cells in nasal mucosa and nasal polyps. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2000;27:59–64. doi: 10.1016/s0385-8146(99)00038-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bernstein JM, Ballow M, Rich G, Allen C, Swanson M, Dmochowski J. Lymphocyte subpopulations and cytokines in nasal polyps: is there a local immune system in the nasal polyp? Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2004;130:526–535. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2003.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sanchez-Segura J, Brieva JA, Rodriguez C. T lymphocytes that infiltrate nasal polyps have a specialized phenotype and produce a mixed TH1/TH2 pattern of cytokines. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1998;102:953–960. doi: 10.1016/s0091-6749(98)70333-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yang L, Anderson DE, Baecher-Allan C, Hastings WD, Bettelli E, Oukka M, et al. IL-21 and TGF-β are required for the differentiation of human Th 17 cells. Nature. 2008;754:350–352. doi: 10.1038/nature07021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kimura A, Naka T, Kishimoto T. IL-6-dependent and –independent pathways in the development of interleukin-17-producing T helper cells. PNAS. 2007;104(29):12099–12104. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0705268104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Matsuzaki G, Umemura M. Interleukin-17 as an effector molecule of innate and acquired immunity against infections. Microbiol Immunol. 2007;51(12):1139–1147. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.2007.tb04008.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kao CY, Chen Y, Thai P, Wachi S, Huang F, Kim C, et al. IL-17 markedly up-regulates beta-defensin-2 expression in human airway epithelium via JAK and NF-kappaB signaling pathways. J Immunol. 2004;173:3482–3489. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.5.3482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Aarvak T, Chabaud M, Miossec P, Natvig JB. IL-17 is produced by some proinflammatory Th1/Th0 cells but not by Th2 cells. J Immunol. 1999;162:1246–1251. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pene J, Chevalier S, Preisser L, Venereau E, Guilleux MH, Ghannam S, et al. Chronically inflamed human tissues are infiltrated by highly differentiated Th17 lymphocytes. J Immunol. 2008;180:7423–7430. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.11.7423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhou L, Lopes JE, Chong MMW, Ivanov II, Min R, Victora GD, et al. TGF-β induced Foxp3 inhibits Th17 cell differentiation by antagonizing RORγt function. Nature. 2008;453:236–240. doi: 10.1038/nature06878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Manel N, Unutmaz D, Littman DR. The differentiation of human Th-17 cells requires transforming growth factor-β and induction of the nuclear receptor RORγt. Nature Immunol. 2008;9(6):641–649. doi: 10.1038/ni.1610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bettelli E, Carrier Y, Gao W, Korn T, Strom TB, Oukka M, et al. Reciprocal developmental pathways for the generation of pathogenic effector Th17 and regulatory T cells. Nature. 2006;441:235–238. doi: 10.1038/nature04753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bettelli E, Oukka M, Kuchroo VK. Th17 cells in the circle of immunity and autoimmunity. Nature Immunol. 2007;8:345–350. doi: 10.1038/ni0407-345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ivanov II, McKenzie BS, Zhou L, Tadokoro CE, Lepelley A, Lafaille JJ, et al. The orphan nuclear receptor RORγt directs the differentiation program of proinflammatory IL-17+ T helper cells. Cell. 2006;126:1121–1133. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.07.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pasare C, Medzhitov R. Toll pathway-dependent blockage of CD4+CD25+ T cell-mediated suppression by dendritic cells. Science. 2003;299:1033–1036. doi: 10.1126/science.1078231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Van Bruaene N, Perez-Novo CA, Basinski TM, Van Zele T, Holtappels G, De Ruyck N, et al. T-cell regulation in chronic paranasal sinus disease. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008;121:1435–1441. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2008.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Molet SM, Hamid QA, Hamilos DL. IL-11 and IL-17 expression in nasal polyps: Relationship to collagen deposition and suppression by intranasal fluticasone propionate. Laryngoscope. 2003;113:1803–1812. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200310000-00027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wang X, Dong Z, Zhu D-D, Guan B. Expression profile of immune-associated genes in nasal polyps. Ann Otology, Rhinol Laryngol. 2006;115(6):450–456. doi: 10.1177/000348940611500609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zhang N, Van Zele T, Perez-Novo C, Van Bruaene N, Holtappels G, DeRuyck N, et al. Different types of T-effector cells orchestrate mucosal inflammation in chronic sinus disease. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008;122:961–968. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2008.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Holland SM, DeLeo FR, Eloumi HZ, Hsu AP, Uzel G, Brodsky N, et al. STAT3 mutations in the Hyper-IgE Syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:1608–1619. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa073687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Milner JD, Brenchley JM, Laurence A, Freeman AF, Hill BJ, Elias KM, et al. Impaired Th17 cell differentiation in subjects with autosomal dominant hyper-IgE syndrome. Nature. 2008;452:773–776. doi: 10.1038/nature06764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Van Zele T, Gevaert P, Watelet JB, Claeys G, Holtappels G, Claeys C, et al. Staphylococcus aureus colonization and IgE antibody formation to enterotoxins is increased in nasal polyposis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;114:981–983. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2004.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bachert C, Gevaert P, Holtappels G, Johansson SG, van Cauwenberge P. Total and specific IgE in nasal polyps is related to local eosinophilic inflammation. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2001;107:607–614. doi: 10.1067/mai.2001.112374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kramer MF, Ostertag P, Pfrogner E, Rasp G. Nasal interleukin-5, immunoglobulin E, eosinophilic cationic protein, and soluble intercellular adhesion molecule-1 in chronic sinusitis, allergic rhinitis, and nasal polyposis. Laryngoscope. 2000;110:1056–1062. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200006000-00031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Tripathi A, Conley DB, Grammer LC, Ditto AM, Lowery MM, Seiberling KA, et al. Immunoglobulin E to staphylococcal and streptococcal toxins in patients with chronic sinusitis/nasal polyposis. Laryngoscope. 2004;114:1822–1826. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200410000-00027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Seiberling KA, Conley DB, Tripathi A, Grammer LC, Suh L, Haines GK, et al. Superantigens and chronic rhinosinusitis: detection of staphylococcal exotoxins in nasal polyps. Laryngoscope. 2005;115:1580–1585. doi: 10.1097/01.mlg.0000168111.11802.9c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Brook I, Frazier EH. Bacteriology of chronic maxillary sinusitis associated with nasal polyposis. J Med Microbiol. 2005;54:595–597. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.45767-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Gevaert P, Holtappels G, Johansson SG, Cuvelier C, Cauwenberge P, Bachert C. Organization of secondary lymphoid tissue and local IgE formation to Staphylococcus aureus enterotoxins in nasal polyp tissue. Allergy. 2005;60:71–79. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2004.00621.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Goya S, Matsuoka H, Mori M, Morishita H, Kida H, Kobashi Y, et al. Sustained interleukin-6 signaling leads to the development of lymphoid organ-like structures in the lung. J Pathol. 2003;200:82–87. doi: 10.1002/path.1321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kato A, Peters A, Suh L, Carter R, Harris KE, Chandra R, et al. Evidence of a role for B cell-activating factor of the TNF family (BAFF) in the pathogenesis of chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008;121:1385–1392. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2008.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.