SUMMARY

Prion diseases are caused by conversion of a normally folded, nonpathogenic isoform of the prion protein (PrPC) to a misfolded, pathogenic isoform (PrPSc). Prion inoculation experiments in mice expressing homologous PrPC molecules on different genetic backgrounds displayed different incubation times, indicating that the conversion reaction may be influenced by other gene products. To identify genes that contribute to prion pathogenesis, we analyzed prion incubation times in mice in which the gene product was inactivated, knocked out or overexpressed. We tested 20 gene candidates, because their products either colocalize with PrP, are associated with Alzheimer’s disease, are elevated during prion disease, or function in PrP-mediated signaling, PrP glycosylation, or protein maintenance. Whereas some of the candidates tested may have a role in the normal function of PrPC, our data show that many genes previously implicated in prion replication have no discernable effect on the pathogenesis of prion disease. While most genes tested did not significantly affect survival times, ablation of amyloid beta (A4) precursor protein (App) or interleukin 1 receptor, type I (Il1r1), and transgenic overexpression of human superoxide dismutase 1 (SOD1) prolonged incubation times by 13%, 16%, and 19%, respectively.

INTRODUCTION

Prion diseases are fatal neurodegenerative disorders of humans and animals that uniquely present as sporadic, genetic, or infectious maladies (Prusiner, 2007). These diseases are caused by prions, which are formed from the conformational conversion of a ubiquitous and noninfectious isoform of the prion protein (PrPC) to disease-associated and infectious isoforms (PrPSc). Prions are unprecedented pathogens because nucleic acids are not involved in their replication (Safar et al., 2005). Genetic experiments have shown that the Prnp gene, which encodes PrPC, controls the incubation period in prioninfected mice (Carlson et al., 1986). In addition, evidence from experiments in inbred mice expressing homologous PrPC molecules show` that genes other than Prnp modify the incubation period to some extent (Carlson et al., 1988, Stephenson et al., 2000). Similarly, studies in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae show that chaperones of the Hsp104, Hsp70, and Hsp40 groups are critical for propagation of the yeast prions [PSI+], [URE3], and [PIN+] (reviewed in (Wickner et al., 2007)).

Based on these studies, any gene product involved in the formation of PrPSc should affect the onset of prion disease if knocked out, inactivated, or overexpressed as demonstrated for PrP itself (Prusiner et al., 1993, Prusiner et al., 1990). Many genes have been suggested to contribute to prion replication, of which we tested 20 (Table 1). Mice in which the candidate gene product was inactivated, ablated or overexpressed were inoculated and incubation times relative to control mice recorded (Table 2–Table 5). To determine whether differences in incubation period were significant, we developed a novel statistical method accounting for interexperiment variability. While most of the tested genes did not play a role in prion disease, we show here that mice deficient for amyloid beta (A4) precursor protein (App) or interleukin 1 receptor, type I (Il1r1) had prolonged incubation times by 13% and 16%, respectively. Similarly, overexpression of human superoxide dismutase 1 (SOD1) extended disease-onset times by 19%.

Table 1.

Proteins tested for their effect on prion replication.

| Protein tested | Reason of interest | Reference | Results |

|---|---|---|---|

| Amyloid beta (A4) precursor protein (App) |

mouse orthologs colocalize with PrPC; human orthologs are associated with AD |

(Farrer et al., 1997, Schmitt-Ulms et al., 2004) | Table 2 |

| Human APP695 Amyloid beta (A4) precursor-like protein (Aplp2) Human Apolipoprotein E (APOE), ε3 and ε4 alleles | |||

| Interleukin 10 (IL-10) | elevated in CJD patients | (Stoeck et al.,2005) | Table 3 |

| Interleukin-1 receptor, type I (IL-1R1) |

elevated levels of IL-1α, IL-1β, and TNF-α in prion-infected mice and CJD patients |

(Campbell et al., 1994, Sharief et al.,1999) | |

| Tumor necrosis factor (TNF-α) | |||

| Transforming growth factor-β1 (TGF-β1) | elevated in prion-infected mice | (Baker et al., 1999) | |

| Chemokine (C-C motif) receptor 2 (CCR2) |

associated with microglial activation in prion disease; elevated levels of CCL2, CCL5, and CCR5 in prion-infected mice |

(Baker et al., 1999, Felton et al., 2005, Lee et al., 2005, Marella & Chabry,2004) | |

| Chemokine (C-C motif) receptor 5 (CCR5) | |||

| Methionine sulfoxide reductase A (MsrA) | putative SOD activity of PrPC | (Moskovitz & Stadtman, 2003, Wong et al., 1999) | Table 4 |

| Methionine sulfoxide reductase B (MsrB) | |||

| Human superoxide dismutase 1 (SOD1) | putative SOD activity of PrPC | (Wong et al., 1999) | |

| Human heat shock protein 70 (Hsp70) | elevated in prion-infected mice and Purkinje cells of CJD patients |

(Kenward et al., 1994, Kovacs et al., 2001) | |

| Mannoside-b1,4-N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase III (Mgat3) | affects PrP glycosylation in prion disease; associated with AD |

(Fiala et al., 2007, Rudd et al., 1999) | |

| Caveolin-1 |

involved in PrP-mediated cellular signaling |

(Mouillet-Richard et al., 2000, Santuccione et al., 2005) | Table 5 |

| Fyn kinase | |||

| Receptor protein tyrosine phosphatase α (RPTPα) | |||

| Doppel (DpI) | paralog of PrP; induces ataxia when cerebrally expressed in Prnp−/− mice |

(Moore et al., 1999) | |

| CD9 | elevated in prion-infected mice and CJD patients |

(Doh-ura et al., 2000) | |

Table 2.

Prion transmission to mouse models relevant to Alzheimer’s disease.*

| Protein | Mice | Strain | Median incubation time (days) |

n† | pL | pWG | Relative time (95% c.i.) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| App | App−/− | C57BL/6J | 136 20 | <0.001 | 0.030 | 1.133 (1.012–1.269) | |

| wt | C57BL/6J | 121 | 19 | ||||

| Aplp2 | Aplp−/− | C57BL/6J | 125 22 | 0.966 | 0.879 | 1.009 (0.902–1.129) | |

| wt | C57BL/6J | 135 | 22 | ||||

| Human APP695 |

Tg(APP)6209Kahs | FVB/N | 123 6 | 0.753 | 0.772 | 1.019 (0.898–1.155) | |

| wt | FVB/N | 126 | 9 | ||||

| Human APOE, ε3 and ε4 alleles |

Tg(APOE3) | C57BL/6J | 168 20 | 0.061 | 0.772 | 1.017 (0.907–1.140) | |

| Tg(APOE4) | C57BL/6J | 161 20 | 0.082 | 0.959 | 0.997 (0.890–1.117) | ||

| Apoe−/− | C57BL/6J | 141 | 19‡ | ||||

Mice were inoculated i.c. with RML prions.

n, number of inoculated mice.

Data from (Tatzelt et al., 1996).

Table 5.

Prion transmission to mouse models relevant to cell signaling.*

| Protein | Mice | Strain | Median incubation time (days) |

n† | pL | pWG | Relative time (95% c.i.) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Caveolin-1 | Cav1−/− FV | B/N | 120 | 8 | 0.006 | 0.081 | 0.901 (0.802–1.013) |

| wt | FVB/N | 131 | 181 | ||||

| Cav−/− F | VB/N | 182‡ | 8 | 0.015 | 0.613 | 1.031 (0.915–1.163) | |

| wt | FVB/N | 176‡ | 10 | ||||

| Fyn | Fyn−/− | 129S7/SvEvBrd and C57BL/6J | 133 | 8 | 0.416 | 0.592 | 1.034 (0.915–1.169) |

| wt | 129S1/SvlmJ | 133 | 8 | ||||

| Tg(Fyn) C | 57BL/6J | 139 | 12 | 0.611 | 0.996 | 1.000 (0.888–1.126) | |

| wt | C57BL/6J | 134 | 8 | ||||

| RPTPα | Ptpra−/− C | 57BL/6J | 137 8 | 0.018 | 0.381 | 0.950 (0.847–1.066) | |

| wt | C57BL/6J | 145 | 82 | ||||

| Dpl | Prnd−/− FV | B/N | 124 | 10 | 0.009 | 0.148 | 0.920 (0.822–1.030) |

| Prnd+/− FV | B/N | 124 | 10 | 0.002 | 0.243 | 0.936 (0.837–1.046) | |

| wt | FVB/N | 131 | 181 | ||||

| CD9 | Cd9−/− C | 57BL/6 | 144 | 9 | 0.083 | 0.526 | 1.040 (0.922–1.172) |

| Cd9+/− C | 57BL/6 | 151 | 10 | 0.065 | 0.329 | 1.060 (0.943–1.193) | |

| wt | C57BL/6 | 128 | 9 | ||||

| Cd9−/− C | 57BL/6 | 196‡ | 10 | 0.032 | 0.535 | 1.038 (0.922–1.169) | |

| wt | C57BL/6 | 194‡ | 10 | ||||

Unless indicated, mice were inoculated i.c. with RML prions.

n, number of inoculated mice.

Mice were inoculated intraperitoneally.

METHODS

Source of mice

Most mouse lines have been described previously. App−/− mice lack amyloid beta (A4) precursor protein (App) (Zheng et al., 1995). Aplp2−/− mice lack amyloid beta (A4) precursor-like protein 2 (Aplp2) (von Koch et al., 1997). Tg(APP)6209Kahs mice, originally designated Tg(HuAPP695.WTmyc)6209, express human APP695 (Hsiao et al., 1995). Tg(APOE3) and Tg(APOE4) mice, originally named Tg(NSE-apoE3) and Tg(NSE-apoE4), express the ε3 or the ε4 allele of human apolipoprotein E (APOE) driven by the neuron-specific enolase (NSE) promoter on a C57BL/6J-Apoe−/− (C57BL6J-Apoetm1Unc) background (Raber et al., 1998). Tg(Tgfb1) mice express porcine transforming growth factor-β1 (TGF-β1) driven by the glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) promoter on a SJL/J background (Wyss-Coray et al., 1995). Tgfb1+/− mice with one ablated Tgfb1 allele were generated on the NIH/Ola background (Shull et al., 1992). Ccr2−/− and Ccr5−/− mice lack chemokine (C-C motif) receptors 2 (CCR2) and CCR5, respectively (Kuziel et al., 2003, Kuziel et al., 1997). (TβRIIΔk)+/− × Tg(tTA)+/− Prnp+/− mice neuronally express a transdominant negative kinase-deficient mutant of TGF-β receptor II (TβRIIΔk) and are deficient in TGF-β signaling (Tesseur et al., 2006). Msra−/− mice lack methionine sulfoxide reductase A (Moskovitz et al., 2001). Tg(SOD1)3Cje mice overexpress human superoxide dismutase 1, soluble (SOD1); their littermate controls are (BALB/c × C57BL/6J)F1 × (C57BL/6J × DBA/2)F1 (Epstein et al., 1987). Tg(HSP70) mice express human heat shock protein 70 (Hsp70); their wt controls are (CBA × C57BL/6J)F1 mice (Plumier et al., 1995). Mgat3−/− mice lack mannoside-b1,4-N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase III (Yang et al., 2000). Cd9−/− mice lack the CD9 antigen (LeNaour et al., 2000). Cav1−/− mice lack caveolin-1 (Williams et al., 2003). Fyn−/− mice lack fyn proto-oncogene (Fyn) (Grant et al., 1992). Tg(Fyn) mice overexpress wt mouse Fyn directed by the calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase IIα promoter on a C57BL/6 background (line N8) (Kojima et al., 1997). Ptpra−/− mice lack protein tyrosine phosphatase, receptor type, A (RPTPα) (Petrone et al., 2003). Prnd-ablated mice on an FVB background were produced in our laboratory as described in the online supplement.

The following mice were obtained from The Jackson Laboratory: Apoe−/− mice on C57BL/6J background (C57BL/6J-Apoetm1Unc); interleukin 10 (IL-10)–knockout mice on a C57BL/6J background, denoted B6-IL10−/− mice (B6.129P2-Il10tm1Cgn/J); IL-10–knockout mice on a 129S6 background, denoted 129-IL10−/− mice (129-Il10tm1Cgn/J); tumor necrosis factor–deficient mice, denoted Tnf−/− mice (B6.129S6-Tnftm1Gkl/J); mice lacking Tnf receptor superfamily, members 1a (TNF-R1) and 1b (TNF-R2), denoted Tnfrsf1a−/− Tnfrsf1b−/− mice (B6; 129S-Tnfrsf1atm1Imx Tnfrsf1btm1Imx/J); and Interleukin 1 receptor, type I-knockout mice, denoted Il1r1−/− mice (B6;129S1-Il1r1tm1Roml/J). C57BL/6J,129S1/SvlmJ, B6129SF2/J, and FVB/N mice were obtained as controls. Crossing Tnfrsf1a+/+ Tnfrsf1b+/+ mice with B6129SF2/J mice gave Tnfrsf1a+/− Tnfrsf1b+/− mice. Crossing Il1r1+/+ mice with B6129SF2/J mice yielded Il1r1+/− mice. The genetic status of the progeny was determined using protocols from the Jackson Laboratory.

Prion isolates and transmission

CD1 mouse–adapted RML, Me7, and 301V prions were used as inocula. RML and Me7 were originally derived from sheep with scrapie and have been serially passaged in mice for many generations; 301V was derived from a cow with BSE and passaged into VM mice (Bruce et al., 1994, Chandler, 1961, Dickinson & Meikle, 1969). Brain homogenates (10% wt/vol) in PBS (pH 7.4) were obtained by 10 repeated extrusions through syringe needles of successively smaller sizes, from 22 to 18 gauge, or alternatively by three 30-second strokes of a PowerGen homogenizer (Fisher Scientific). A final 1% (wt/vol) brain homogenate for inoculation was obtained by further diluting brain homogenates in 5% (wt/vol) bovine albumin Fraction V (ICN) and PBS. Using a 27-gauge syringe, 30 µl of 1% brain homogenate were inoculated into the right parietal lobe, or 200 µl into the peritoneal cavity of mice. Animals were monitored daily for their clinical status, while the neurologic status was assessed three times per week. Mice with progressive neurologic dysfunction were euthanized (Carlson et al., 1986).

RESULTS

The experimental paradigm of this study was to investigate the influence of 20 genes on the incubation time in prion-infected mice in which the gene product was either inactive, absent or overexpressed.

Modeling disease onset times

To determine the genotype-independent variation in incubation time, we intracerebrally (i.c.) inoculated over 400 wt FVB/N mice that were divided into 39 groups at 6 different time points over a five-year period with RML prions (Table S1, Fig. 1). Median incubation times were calculated for all 39 groups using the Kaplan-Meier function and mice with intercurrent illness were censored at the time of euthanasia (Kaplan & Meier, 1958). Although these mice were genetically identical, we observed appreciable variation in median incubation times among different groups of mice ranging between 103 and 137 days for individual groups. This variation was not restricted to wt FVB/N mice but also evident in C57BL/6J and CD1 mice (data not shown). Since the commonly used logrank test does not take into account this type of experiment-to-experiment variation among genotypically identical mice, we developed a method to better compare survival curves of prion-diseased mice. Based on our observations, disease-onset times were well fit using a Weibull regression model with the effects of genotypes following an accelerated failure time model (Table 2–Table 5) (Cox & Oakes, 1984). This model accommodates for the fact that in a group of prion-infected mice with the same genotype, all animals become sick within a very close time interval once single animals start to show symptoms. To account for experiment-to-experiment variation, we included a gamma distributed random effect term in the Weibull model that was weighted by the interexperimental variation observed in RML-inoculated, FVB/N mice (Table S1, Fig. 1) (Glidden & Vittinghoff, 2004, Nielsen et al., 1992). This improved the accuracy of our statistical evaluation and led to p-values (pWG) that were generally higher than those obtained with the logrank test (pL) (Table 2–Table 5). Effects of experiments in mice expressing neither, one, or both alleles of Il1r1, Tnfrsf1a and Tnfrsf1b, Cd9, and Prnd were also tested for trend (Vittinghoff et al., 2005). For a given gene, the trend test delivers increased significance, when incubation times are increasingly prolonged or shortened based on the number of alleles present. The relative time for each genotype shown in Table 2–Table 5 was calculated from the accelerated failure time model, which takes into account both medians and interpercentile ranges of disease-onset times from genetically modified mice and control mice. All calculations were performed with Intercooled Stata 9.2 (StataCorp).

Fig. 1.

Survival curves from transmissions of RML prions to six sets of FVB/N mice. Animals in each set were inoculated on the same day. Median incubation times ranged between 103 and 137 days.

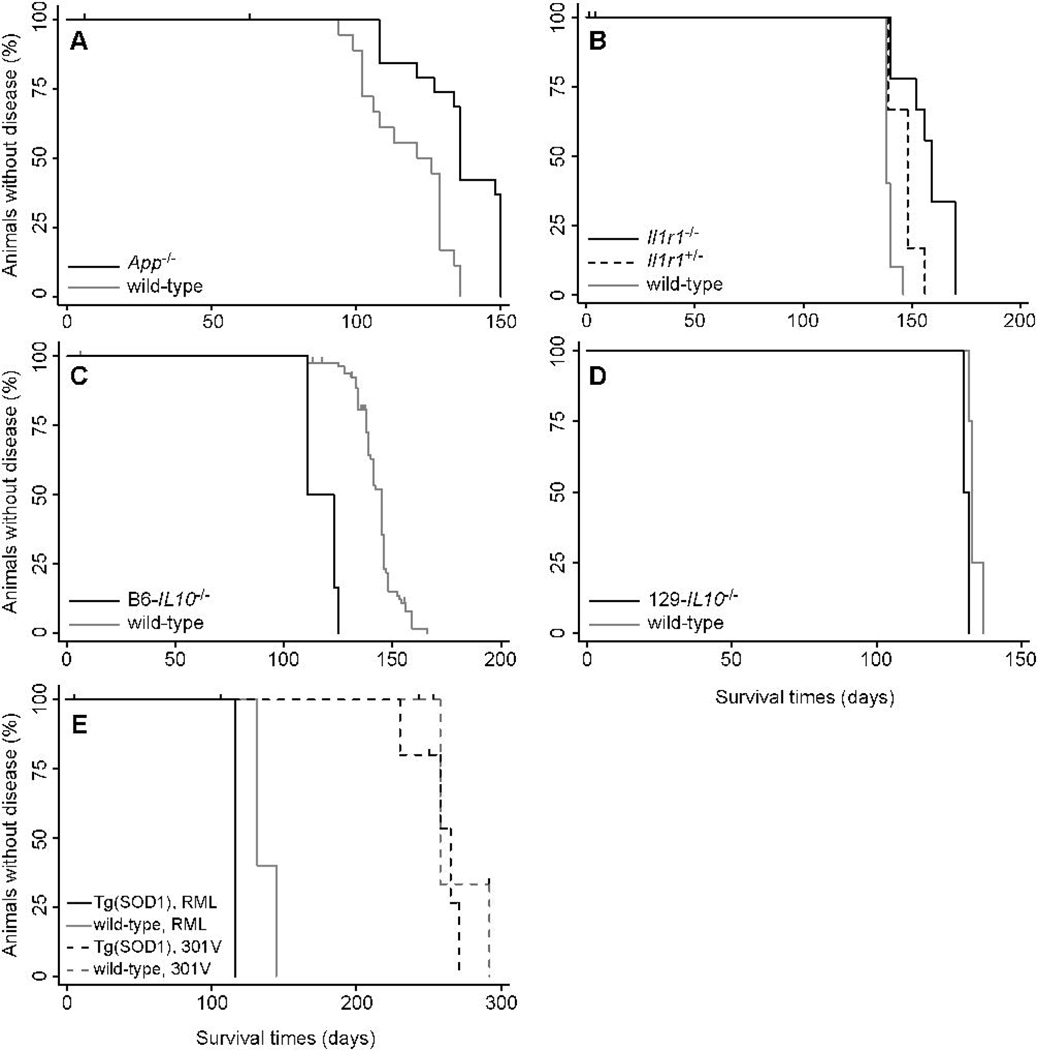

Deficiency in App prolongs prion-incubation times

To analyze the effect of the five AD-related proteins on the incubation time in prion disease, we inoculated five different mouse models and their respective controls with RML prions (Table 2). App−/− mice deficient in App expression developed signs of prion disease at ~136 days, whereas wt mice had a median incubation time of 121 days (Fig. 2A). Taking interexperimental variation into account, this 13% protraction of disease-onset times in App−/− mice was slight but significant (pWG=0.030). In contrast, lack of Aplp2 expression in Aplp2−/− mice or overexpression of human APP695 in Tg(APP)6209Kahs mice had no significant effect on incubation times (Fig. S2A and B). Similarly, expression of human APOE3 or APOE4 alleles in Apoe−/− mice did not result in significant differences in the incubation times when compared to Apoe−/− mice (Fig. S2C and D).

Fig. 2.

Survival curves from transmissions of RML prions to (A) App−/− mice; (B) Il1rr−/− mice (black line) and Il1rI+/− mice (dashed line); (C) B6-IL10−/− mice; (D) 129Sv-IL10−/− mice; and (E) Tg(SOD1)3Cje (solid lines). In panel E, Tg(SOD1)3Cje mice were also inoculated with 301V prions (dashed lines). Survival curves of controls are shown by gray lines. Tick marks signify censored animals.

Deficiency of a functional IL-1 receptor prolongs prion incubation times

We assayed six genes associated with inflammation for their effect on the prion incubation time (Table 3). Mice with an ablated interleukin-1 receptor, type I gene (Il1r1−/−) lack a functional receptor for the proinflammatory cytokines IL-1α and IL-1β and showed 16% longer incubation times compared to control mice (Fig 2B). Although small, this prolongation was statistically significant (pWG=0.012).

Table 3.

Prion transmission to mouse models relevant to inflammation.*

| Protein | Mice | Strain | Median incubation time (days) |

n† | pL | pWG | Relative time (95% c.i.) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IL-10 | B6-IL10−/− C | 57BL/6J | 111 | 6 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.814 (0.724–0.916) |

| wt | C57BL/6J | 145 | 82‡ | ||||

| 129-IL10−/− 129S | 6 | 130 | 8 | 0.001 | 0.718 | 0.978 (0.867–1.103) | |

| wt | 129S1/SvlmJ | 133 | 8 | ||||

| IL-1R1 | Il1r1−/− | 129S1/Sv and C57BL/6 | 159 | 10 | <0.001 | 0.012 | 1.164 (1.035–1.309) |

| Il1r1+/− | 129S1/Sv, C57BL/6, and B6129SF2/J |

148 10 | 0.009 | 0.332 | 1.061 (0.941–1.197) | ||

| wt | B6129SF2/J | 138 | 10§ | ||||

| TNF-α | Tnf−/− C | 57BL/6 | 149 | 15 | 0.008 | 0.432 | 0.954 (0.848–1.073) |

| wt | C57BL/6J | 162 | 12 | ||||

| TNF-R1 and TNF-R2 | Tnfrsf1a−/− Tnfrsf1b−/− | 129S7/SvEvBrd and C57BL/6 | 126 | 9 | 0.001 | 0.341 | 0.944 (0.839–1.063) |

| Tnfrsf1a+/− Tnfrsf1b+/− | 129S7/SvEvBrd, C57BL/6, and B6129SF2/J |

132 10 | <0.001 | 0.315 | 0.942 (0.838–1.059) | ||

| wt | B6129SF2/J | 138 | 10§ | ||||

| TGF-β1 | Tg(Tgfb1) S | JL/J | 99 | 5 | |||

| wt | SJL/J | 5 | |||||

| Tgfb1+/− N | IH/Ola | 124 | 8 | 0.990 | 0.353 | 1.060 (0.937–1.200) | |

| wt | NIH/Ola | 124 | 6 | ||||

| TGF-β type II receptor, kinase deficient (TβRIIΔk) |

Tg(TβRIIΔk)+/− × Tg(tTA)+/− Prnp+/− | C57BL/6J and FVB/N | 355 | 7 | 0.523 | 0.857 | 1.011 (0.894–1.145) |

| Tg(TβRIIΔk)+/− × Tg(tTA)−/− Prnp+/− | C57BL/6J and FVB/N | 287 | 6 | ||||

| CCR2 | Ccr2−/− C | 57BL/6J | 141 | 20 | 0.827 | 0.456 | 1.04 (0.934–1.166) |

| wt | C57BL/6J | 145 | 82‡ | ||||

| CCR5 | Ccr5−/− C | 57BL/6J | 141 | 31 | 0.968 | 0.891 | 0.992 (0.889–1.108) |

| wt | C57BL/6J | 145 | 82‡ | ||||

Mice were inoculated i.c. with RML prions.

n, number of inoculated mice.

Experiments were listed more than once for better comparison.

Mice deficient of the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10 had a 19% reduction in the incubation period compared to wt mice. However, this reduction was observed only in IL10−/− mice on the C57BL/6J background but not on the 129S1/SvlmJ background (Fig. 2C and D).

None of the other four inflammation-associated genes affected incubation times (Fig. S3A–F). In two mouse models, inhibited TNF-α signaling resulted in incubation times similar to controls (Fig. S3A and B). We also found that TGF-β1 signaling had no effect on prion incubation times, using three different mouse models: Tg(Tgfb1) mice overexpressing TGF-β1, heterozygous Tg(Tgfb1+/−) mice, and double-transgenic Tg(TβRIIΔk)+/− × Tg(tTA) +/− Prnp+/− mice expressing a transdominant negative mutant of TGF-β receptor II that disrupts TGF-β signaling (Fig. S3C and D). Deficiency of CCR2 or CCR5 also did not influence prion incubation times (Fig. S3E and F).

Proteins associated with protein maintenance do not influence prion incubation times

We tested the influence of four genes relevant to protein expression and maintenance on prion-incubation times (Table 4). The methionine sulfoxide reductase (Msr) system consisting of MsrA and MsrB reverts methionine sulfoxide to methionine and thereby protects from oxidative stress (Moskovitz & Stadtman, 2003). We tested the effect of oxidative stress on prion replication in MsrA-knockout mice on a regular or on a selenium-depleted diet that further disables the Msr system by inactivating MsrB, which as a selenoprotein requires selenium to be fully active. Msra-deficient mice that were kept on a regular or selenium-depleted diet did not show incubation times significantly different from control mice (Fig. S4A). Incubation times in Tg(SOD1)3Cje mice that overexpress human superoxide dismutase 1 (SOD1) were significantly (pWG=0.016) extended by 19% after infection with RML prions (Fig. 2E), compared to wt littermates. However, this prolongation was not observed when Tg(SOD1)3Cje mice were infected with the 301V prion strain. Tg(HSP70) mice, which overexpress human Hsp70, did not show significantly altered incubation times compared to wt littermates (Fig. 2F). Finally, we addressed whether posttranslational modifications impact PrP conversion in mice lacking mannoside-b1,4-N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase III (Mgat3/GlcNAcT-III). In comparison to PrPC, PrPSc contains decreased levels of N-glycans with a bisecting GlcNAc residue and increased levels of tri- and tetraantennary complex N-glycans, which may result from a decrease in Mgat3/GlcNAcT-III activity (Rudd et al., 1999). Incubation times in Mgat3−/− mice did not differ significantly from wt littermates, even when mice were inoculated with three different prion strains: RML, ME7, and 301V (Fig. S4B).

Table 4.

Prion transmission to mouse models relevant to protein maintenance.*

| Protein | Mice | Strain | Median incubation time (days) |

n† | pL | pWG | Relative time (95% c.i.) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MsrA and MsrB | Msra−/− | 129/SvJ and C57BL/6J | 134 | 9 | 0.507 | 0.888 | 0.991 (0.879–1.119) |

| wt | 129/SvJ and C57BL/6J | 124 | 10 | ||||

| Msra−/− | 129/SvJ and C57BL/6J | 134‡ | 7 | 0.949 | 0.997 | 1.000 (0.887–1.128) | |

| wt | 129/SvJ and C57BL/6J | 131‡ | 10 | ||||

| Human SOD1 | Tg(SOD1)3Cje | BALB/c, C57BL/6J, and DBA/2 | 132 | 5 | 0.014 | 0.016 | 1.188 (1.033–1.367) |

| wt | BALB/c, C57BL/6J, and DBA/2 | 117 | 4 | ||||

| Tg(SOD1)3Cje | BALB/c, C57BL/6J, and DBA/2 | 265§ | 5 | 0.441 | 0.267 | 0.923 (0.800–1.064) | |

| wt | BALB/c, C57BL/6J, and DBA/2 | 258§ | 5 | ||||

| Human Hsp70 | Tg(HSP70) | CBA and C57BL/6 | 132 | 10 | 0.007 | 0.271 | 1.070 (0.948–1.207) |

| wt | CBA and C57BL/6 | 118 | 10 | ||||

| Mgat3 | Mgat3−/− | C57BL/6 and CD1 | 161 | 7 | 0.001 | 0.079 | 1.114 (0.988–1.255) |

| wt | C57BL/6 and CD1 | 140 | 11 | ||||

| Mgat3−/− | C57BL/6 and CD1 | 165¶ | 6 | 0.116 | 0.067 | 1.122 (0.992–1.269) | |

| wt | C57BL/6 and CD1 | 147¶ | 10 | ||||

| Mgat3−/− | C57BL/6 and CD1 | 237§ | 9 | 0.218 | 0.378 | 1.059 (0.933–1.201) | |

| wt | C57BL/6 and CD1 | 225§ | 8 | ||||

Unless indicated, mice were inoculated i.c. with RML prions.

n, number of inoculated mice.

Mice were fed a selenium-depleted diet.

Mice were inoculated with 301V prions.

Mice were inoculated with Me7 prions.

Proteins associated with PrP signaling, doppel, and CD9 do not influence prion incubation times

We investigated the effect of three genes that are seemingly relevant to PrP signaling on prion replication (Table 5). Incubation times in caveolin-1–deficient mice inoculated either i.c. or intraperitoneally (i.p.) did not differ significantly from those of FVB/N control mice (Fig. S5A). Neither mice lacking nor overexpressing Fyn showed altered incubation times upon infection when compared to wt mice (Fig. S5B and C). Ptpra−/− mice deficient for RPTPα also did not have significantly changed incubation times (Fig. S5D). As part of this work, we created Prnd−/− mice that lack expression of the PrP paralog doppel (Dpl), which did not show any morphological or behavioral defects except for male infertility, as reported earlier (Behrens et al., 2002). Neither Prnd+/– nor Prnd−/− mice showed significantly modified incubation times when compared to wt mice (Fig. S5E). We also did not find significantly different incubation times from Cd9−/− mice, heterozygous Cd9+/− mice, or wt mice after i.c. inoculation with RML prions (Fig. S5F). Because CD9 is present on the cell surface of lymphocytes, we also inoculated Cd9−/− and wt mice i.p. with RML prions. Incubation times after i.p. inoculation were not significantly different.

DISCUSSION

The identification of genes that contribute to prion pathogenesis is of paramount importance for understanding prion diseases. Although many PrP-interacting proteins have been identified, only few have been shown to influence prion replication (Schmitt-Ulms et al., 2004, Westergard et al., In press). To prove that a gene contributes to prion pathogenesis, its inactivation, absence, or overexpression should affect prion replication as evidenced from experiments in inbred mice and yeast (Carlson et al., 1988, Stephenson et al., 2000, Wickner et al., 2007). We analyzed a series of candidate genes with importance in AD, inflammation, cell signaling, and other cellular functions for their effect on prion pathogenesis. We modeled disease-onset times after a Weibull regression model that included a gamma distributed random effect to account for interexperimental variation. Based on our statistical model, only very few from among 20 candidate genes moderately but significantly affected prion pathogenesis.

We show that knockout of App protracts the onset of prion disease by 13%. While the underlying mechanism is unclear, its elucidation is likely to promote our understanding of the neurodegenerative processes in prion disease as well as in AD, both of which share many common features (DeArmond, 1993). In AD, cleavage of APP gives rise to pathogenic Aβ peptides that are rich in β-sheet conformation and that can form amyloid plaques in the CNS similar to PrPSc.

Cytokines and their receptors are key mediators of inflammatory as well as anti-inflammatory responses and are often found to be upregulated in a multitude of neurodegenerative conditions, including trauma, stroke, AD, and prion disease. Of six candidate genes that had previously been reported to be upregulated during prion disease, only interruption of IL-1 signaling mildly but significantly prolonged disease-onset times by 16%. Our results agree with a study reporting prolonged incubation times in Il1r1-knockout mice after i.c. infection with at least ~15-fold lower concentrations of mouse-adapted 138A scrapie prions (Schultz et al., 2004). The prolonged incubation time likely occurs by delaying astrocytic gliosis, as IL-1R1 is mainly expressed on astrocytes and oligodendrocytes in the CNS and Il1r1−/− mice show reduced inflammatory responses (Brogi et al., 1997, Labow et al., 1997, Tomozawa et al., 1995).

Consistent with other studies, abrogated TNF-α or TGF-β signaling did not affect prion pathogenesis after i.c. inoculation (Klein et al., 1997, Mabbott et al., 2000). In Il10−/− mice, we observed a 19% reduction in the incubation time on a C57BL/6J background, but no change on a 129S1/SvlmJ background. Differences in the genetic background of these two inbred mouse strains likely explain the different incubation times we observed: While all Il10−/− mice are anemic, growth retarded and develop chronic enterocolitis to intestinal antigens (Kuhn et al., 1993), Il10−/− mice on the C56BL/6J background have less inflammation and fewer adenocarcinomas than mice on the 129Sv background (Berg et al., 1996). Our results make it difficult to draw a firm conclusion about the role of IL-10 in prion pathogenesis but severely contrast an earlier report in which a >50% reduction in incubation time was reported for Il10−/− mice on a 129S1/SvlmJ background (Thackray et al., 2004).

Prion disease is accompanied by activation and recruitment of microglia to sites of prion replication (Guiroy et al., 1994). CCR2 and CCR5 are expressed on microglia and functional in their activation and recruitment through interaction with chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 2 (CCL2) and CCL5 (Albright et al., 1999, El Khoury et al., 2007). Although survival times of Ccl2−/− mice infected with ME7 prions were reported to be prolonged (Felton et al., 2005), we failed to detect an effect on survival in Ccr2−/− and Ccr5−/− mice infected with RML prions. How ablation of Ccl2 but not Ccr2 can affect survival times in prion disease is unclear, since CCR2 is the only established high-affinity receptor for CCL2 (Charo et al., 1994). This disparity may be attributed to infection with different prion strains of different titers or to problematic statistical analysis of survival times in Ccl2−/− mice. It remains to be determined if either CCR2 or CCR5 can compensate for the other’s activity in microglial activation and if incubation times would be prolonged in Ccr2–Ccr5 double-knockout mice.

Our studies also clearly show that the formation of methionine oxides does not play a critical role in prion pathogenesis. Because certain methionine residues in PrPC can be oxidized, it was suggested that PrPC may protect from oxidative stress (Wong et al., 1999). Disabling the Msr system, which reverts methionine sulfoxide to methionine, increases sensitivity to oxidative stress resulting in reduced life span, elevated levels of hippocampal neurodegeneration, Aβ deposition and tau phosphorylation (Pal et al., 2007). MsrA-knockout mice without a functional Msr system (Moskovitz & Stadtman, 2003) showed incubation times similar to controls.

Furthermore, our studies show that the production of free radicals may affect the progression of disease in a strain-dependent fashion. PrPC has been controversially discussed to have SOD activity and that loss of this putative function by its conversion to PrPSc may contribute to prion disease (Hutter et al., 2003, Wong et al., 1999). While disabling the Msr system did not affect prion pathogenesis, Tg(SOD)3Cje mice overexpressing human SOD1 showed prolonged incubation times when inoculated with RML prions, but not when injected with 301V prions. In contrast to RML prions, the 301V strain replicates very slowly in mice expressing mouse PrP-A and PrPSc deposits accumulate only relatively late during pathogenesis. This may cause less immediate inflammation and thus less free radical production (Farquhar et al., 1996). A protective effect of increased SOD activity may only be visible with a fast-replicating strain, such as RML prions where PrPSc deposits, inflammation, and free-radical production appear relatively early after infection.

While CD9 ablation did not affect incubation times, we cannot exclude that CD81, which shares approximately 65% sequence similarity with CD9, can compensate for the PrP-related functions in Cd9−/− mice. In this case, a Cd9–Cd81 double-knockout mouse might provide some insight into the role of CD9 and/or CD81 during PrP conversion. While tetraspanins such as CD9 are known for their exceptional ability to associate with other surface proteins, no association of CD9 with PrP could be observed (E. Rubinstein, unpublished data).

In conclusion, our studies underscore the importance of screening genes that may contribute to prion pathogenesis in in vivo models to establish their function in PrP conversion and pathogenesis. While all candidate genes tested here were implicated to have a role in prion pathogenesis in previous studies, only three were shown to affect disease-onset times. We note that many factors influence these findings, such as the genetic background of the animal model, the prion strain, inoculum titers, the route of infection, and importantly, the statistical analysis of incubation times. By using appropriate controls and a rigorous statistical analysis that takes interexperimental variation into account, we were able to rule out many candidate genes, which otherwise would have scored as “significant” based on the logrank test alone. Clearly, the conversion of PrPC to PrPSc involves a complex pathway, the elucidation of which would benefit treatment of these devastating diseases.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

G.T. was supported through a fellowship by the Larry L. Hillblom Foundation. This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (AG02132, AG10770, and AG021601) as well as by a gift from the G. Harold and Leila Y. Mathers Charitable Foundation. The authors thank the staff of the Hunters Point animal facility for support with the transgenic animal experiments and Hang Nguyen for editorial assistance. We also thank Juanito Meneses and Dr. Roger Pedersen for help with ES cell work, Gerassimos Pagoulatos for providing Tg(HSP70) mice, Nobuhiko Kojima for Tg(Fyn) mice, and Sangram Sisodia for App−/− and Aplp2−/− mice. S.B.P., K.G., and F.E.C. have financial interest in InPro Biotechnology, Inc.

REFERENCES

- Albright AV, Shieh JT, Itoh T, Lee B, Pleasure D, O'Connor MJ, Doms RW, Gonzalez-Scarano F. Microglia express CCR5, CXCR4, and CCR3, but of these, CCR5 is the principal coreceptor for human immunodeficiency virus type 1 dementia isolates. J. Virol. 1999;73:205–213. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.1.205-213.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker CA, Lu ZY, Zaitsev I, Manuelidis L. Microglial activation varies in different models of Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease. J. Virol. 1999;73:5089–5097. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.6.5089-5097.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behrens A, Genoud N, Naumann H, Rülicke T, Janett F, Heppner FL, Ledermann B, Aguzzi A. Absence of the prion protein homologue Doppel causes male sterility. EMBO J. 2002;21:3652–3658. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg DJ, Davidson N, Kuhn R, Muller W, Menon S, Holland G, Thompson-Snipes L, Leach MW, Rennick D. Enterocolitis and colon cancer in interleukin-10-deficient mice are associated with aberrant cytokine production and CD4(+) TH1-like responses. J. Clin. Invest. 1996;98:1010–1020. doi: 10.1172/JCI118861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brogi A, Strazza M, Melli M, Costantino-Ceccarini E. Induction of intracellular ceramide by interleukin-1 beta in oligodendrocytes. J. Cell Biochem. 1997;66:532–541. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4644(19970915)66:4<532::aid-jcb12>3.0.co;2-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruce M, Chree A, McConnell I, Foster J, Pearson G, Fraser H. Transmission of bovine spongiform encephalopathy and scrapie to mice: strain variation and the species barrier. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 1994;343:405–411. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1994.0036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell IL, Eddleston M, Kemper P, Oldstone MB, Hobbs MV. Activation of cerebral cytokine gene expression and its correlation with onset of reactive astrocyte and acute-phase response gene expression in scrapie. J. Virol. 1994;68:2383–2387. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.4.2383-2387.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson GA, Goodman PA, Lovett M, Taylor BA, Marshall ST, Peterson-Torchia M, Westaway D, Prusiner SB. Genetics and polymorphism of the mouse prion gene complex: control of scrapie incubation time. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1988;8:5528–5540. doi: 10.1128/mcb.8.12.5528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson GA, Kingsbury DT, Goodman PA, Coleman S, Marshall ST, DeArmond S, Westaway D, Prusiner SB. Linkage of prion protein and scrapie incubation time genes. Cell. 1986;46:503–511. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90875-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandler RL. Encephalopathy in mice produced by inoculation with scrapie brain material. Lancet. 1961;277:1378–1379. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(61)92008-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charo IF, Myers SJ, Herman A, Franci C, Connolly AJ, Coughlin SR. Molecular cloning and functional expression of two monocyte chemoattractant protein 1 receptors reveals alternative splicing of the carboxyl-terminal tails. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1994;91:2752–2756. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.7.2752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox DR, Oakes D. New York: Chapman & Hall/CRC; 1984. Analysis of Survival Data; p. 208. [Google Scholar]

- DeArmond SJ. Alzheimer's disease and Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease: overlap of pathogenic mechanisms. Curr. Opin. Neurol. 1993;6:872–881. doi: 10.1097/00019052-199312000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickinson AG, Meikle VM. A comparison of some biological characteristics of the mouse-passaged scrapie agents, 22A and ME7. Genet. Res. 1969;13:213–225. doi: 10.1017/s0016672300002895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doh-ura K, Mekada E, Ogomori K, Iwaki T. Enhanced CD9 expression in the mouse and human brains infected with transmissible spongiform encephalopathies. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 2000;59:774–785. doi: 10.1093/jnen/59.9.774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ElKhoury J, Toft M, Hickman SE, Means TK, Terada K, Geula C, Luster AD. Ccr2 deficiency impairs microglial accumulation and accelerates progression of Alzheimer-like disease. Nat. Med. 2007;13:432–438. doi: 10.1038/nm1555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein CJ, Avraham KB, Lovett M, Smith S, Elroy-Stein O, Rotman G, Bry C, Groner Y. Transgenic mice with increased Cu/Zn-superoxide dismutase activity: animal model of dosage effects in Down syndrome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1987;84:8044–8048. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.22.8044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farquhar CF, Dornan J, Moore RC, Somerville RA, Tunstall AM, Hope J. Protease-resistant PrP deposition in brain and non-central nervous system tissues of a murine model of bovine spongiform encephalopathy. J. Gen. Virol. 1996;77:1941–1946. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-77-8-1941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrer LA, Cupples LA, Haines JL, Hyman B, Kukull WA, Mayeux R, Myers RH, Pericak-Vance MA, Risch N, van Duijn CM. Effects of age, sex, and ethnicity on the association between apolipoprotein E genotype and Alzheimer disease. JAMA. 1997;278:1349–1356. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felton LM, Cunningham C, Rankine EL, Waters S, Boche D, Perry VH. MCP-1 and murine prion disease: separation of early behavioural dysfunction from overt clinical disease. Neurobiol. Dis. 2005;20:283–295. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2005.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiala M, Liu PT, Espinosa-Jeffrey A, Rosenthal MJ, Bernard G, Ringman JM, Sayre J, Zhang L, Zaghi J, Dejbakhsh S, Chiang B, Hui J, Mahanian M, Baghaee A, Hong P, Cashman J. Innate immunity and transcription of MGAT-III and Toll-like receptors in Alzheimer's disease patients are improved by bisdemethoxycurcumin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:12849–12854. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0701267104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glidden DV, Vittinghoff E. Modelling clustered survival data from multicentre clinical trials. Stat. Med. 2004;23:369–388. doi: 10.1002/sim.1599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant SG, O'Dell TJ, Karl KA, Stein PL, Soriano P, Kandel ER. Impaired long-term potentiation, spatial learning, and hippocampal development in fyn mutant mice. Science. 1992;258:1903–1910. doi: 10.1126/science.1361685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guiroy DC, Wakayama I, Liberski PP, Gajdusek DC. Relationship of microglia and scrapie amyloid-immunoreactive plaques in kuru, Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease and Gerstmann-Straussler syndrome. Acta Neuropathol. (Berl) 1994;87:526–530. doi: 10.1007/BF00294180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsiao KK, Borchelt DR, Olson K, Johannsdottir R, Kitt C, Yunis W, Xu S, Eckman C, Younkin S, Price D, et al. Age-related CNS disorder and early death in transgenic FVB/N mice overexpressing Alzheimer amyloid precursor proteins. Neuron. 1995;15:1203–1218. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90107-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutter G, Heppner FL, Aguzzi A. No superoxide dismutase activity of cellular prion protein in vivo. Biol. Chem. 2003;384:1279–1285. doi: 10.1515/BC.2003.142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan EL, Meier P. Nonparametric estimation from incomplete observations. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1958;53:457–481. [Google Scholar]

- Kenward N, Hope J, Landon M, Mayer RJ. Expression of polyubiquitin and heat-shock protein 70 genes increases in the later stages of disease progression in scrapie-infected mouse brain. J. Neurochem. 1994;62:1870–1877. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1994.62051870.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein MA, Frigg R, Flechsig E, Raeber AJ, Kalinke U, Bluethmann H, Bootz F, Suter M, Zinkernagel RM, Aguzzi A. A crucial role for B cells in neuroinvasive scrapie. Nature. 1997;390:687–691. doi: 10.1038/37789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kojima N, Wang J, Mansuy IM, Grant SG, Mayford M, Kandel ER. Rescuing impairment of long-term potentiation in fyn-deficient mice by introducing Fyn transgene. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1997;94:4761–4765. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.9.4761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovacs GG, Kurucz I, Budka H, Adori C, Muller F, Acs P, Kloppel S, Schatzl HM, Mayer RJ, Laszlo L. Prominent stress response of Purkinje cells in Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease. Neurobiol. Dis. 2001;8:881–889. doi: 10.1006/nbdi.2001.0418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhn R, Lohler J, Rennick D, Rajewsky K, Muller W. Interleukin-10-deficient mice develop chronic enterocolitis. Cell. 1993;75:263–274. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)80068-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuziel WA, Dawson TC, Quinones M, Garavito E, Chenaux G, Ahuja SS, Reddick RL, Maeda N. CCR5 deficiency is not protective in the early stages of atherogenesis in apoE knockout mice. Atherosclerosis. 2003;167:25–32. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9150(02)00382-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuziel WA, Morgan SJ, Dawson TC, Griffin S, Smithies O, Ley K, Maeda N. Severe reduction in leukocyte adhesion and monocyte extravasation in mice deficient in CC chemokine receptor 2. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1997;94:12053–12058. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.22.12053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labow M, Shuster D, Zetterstrom M, Nunes P, Terry R, Cullinan EB, Bartfai T, Solorzano C, Moldawer LL, Chizzonite R, McIntyre KW. Absence of IL-1 signaling and reduced inflammatory response in IL-1 type I receptor-deficient mice. J. Immunol. 1997;159:2452–2461. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee HP, Jun YC, Choi JK, Kim JI, Carp RI, Kim YS. The expression of RANTES and chemokine receptors in the brains of scrapie-infected mice. J. Neuroimmunol. 2005;158:26–33. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2004.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeNaour F, Rubinstein E, Jasmin C, Prenant M, Boucheix C. Severely reduced female fertility in CD9-deficient mice. Science. 2000;287:319–321. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5451.319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mabbott NA, Williams A, Farquhar CF, Pasparakis M, Kollias G, Bruce ME. Tumor necrosis factor alpha-deficient, but not interleukin-6-deficient, mice resist peripheral infection with scrapie. J. Virol. 2000;74:3338–3344. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.7.3338-3344.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marella M, Chabry J. Neurons and astrocytes respond to prion infection by inducing microglia recruitment. J. Neurosci. 2004;24:620–627. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4303-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore RC, Lee IY, Silverman GL, Harrison PM, Strome R, Heinrich C, Karunaratne A, Pasternak SH, Chishti MA, Liang Y, Mastrangelo P, Wang K, Smit AFA, Katamine S, Carlson GA, Cohen FE, Prusiner SB, Melton DW, Tremblay P, Hood LE, Westaway D. Ataxia in prion protein (PrP)-deficient mice is associated with upregulation of the novel PrP-like protein doppel. J. Mol. Biol. 1999;292:797–817. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.3108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moskovitz J, Bar-Noy S, Williams WM, Requena J, Berlett BS, Stadtman ER. Methionine sulfoxide reductase (MsrA) is a regulator of antioxidant defense and lifespan in mammals. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2001;98:12920–12925. doi: 10.1073/pnas.231472998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moskovitz J, Stadtman ER. Selenium-deficient diet enhances protein oxidation and affects methionine sulfoxide reductase (MsrB) protein level in certain mouse tissues. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2003;100:7486–7490. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1332607100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mouillet-Richard S, Mutel V, Loric S, Tournois C, Launay J-M, Kellermann O. Regulation by neurotransmitter receptors of serotonergic or catecholaminergic neuronal cell differentiation. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:9186–9192. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.13.9186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen GG, Gill RD, Andersen PK, Sørensen TIA. A counting process approach to maximum likelihood estimation in frailty models. Scand. J. Stat. 1992;19:25–43. [Google Scholar]

- Pal R, Oien DB, Ersen FY, Moskovitz J. Elevated levels of brain-pathologies associated with neurodegenerative diseases in the methionine sulfoxide reductase A knockout mouse. Exp. Brain Res. 2007;180:765–774. doi: 10.1007/s00221-007-0903-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrone A, Battaglia F, Wang C, Dusa A, Su J, Zagzag D, Bianchi R, Casaccia-Bonnefil P, Arancio O, Sap J. Receptor protein tyrosine phosphatase alpha is essential for hippocampal neuronal migration and long-term potentiation. EMBO J. 2003;22:4121–4131. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plumier JC, Ross BM, Currie RW, Angelidis CE, Kazlaris H, Kollias G, Pagoulatos GN. Transgenic mice expressing the human heat shock protein 70 have improved post-ischemic myocardial recovery. J. Clin. Invest. 1995;95:1854–1860. doi: 10.1172/JCI117865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prusiner SB. Prions. In: Knipe DM, Howley PM, Griffin DE, Lamb RA, Martin MA, Roizman B, Straus SE, editors. Fields Virology. 5th edn. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2007. pp. 3059–3092. [Google Scholar]

- Prusiner SB, Groth D, Serban A, Koehler R, Foster D, Torchia M, Burton D, Yang S-L, DeArmond SJ. Ablation of the prion protein (PrP) gene in mice prevents scrapie and facilitates production of anti-PrP antibodies. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1993;90:10608–10612. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.22.10608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prusiner SB, Scott M, Foster D, Pan K-M, Groth D, Mirenda C, Torchia M, Yang S-L, Serban D, Carlson GA, Hoppe PC, Westaway D, DeArmond SJ. Transgenetic studies implicate interactions between homologous PrP isoforms in scrapie prion replication. Cell. 1990;63:673–686. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90134-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raber J, Wong D, Buttini M, Orth M, Bellosta S, Pitas RE, Mahley RW, Mucke L. Isoform-specific effects of human apolipoprotein E on brain function revealed in ApoE knockout mice: increased susceptibility of females. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1998;95:10914–10919. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.18.10914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudd PM, Endo T, Colominas C, Groth D, Wheeler SF, Harvey DJ, Wormald MR, Serban H, Prusiner SB, Kobata A, Dwek RA. Glycosylation differences between the normal and pathogenic prion protein isoforms. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1999;96:13044–13049. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.23.13044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Safar JG, Kellings K, Serban A, Groth D, Cleaver JE, Prusiner SB, Riesner D. Search for a prion-specific nucleic acid. J. Virol. 2005;79:10796–10806. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.16.10796-10806.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santuccione A, Sytnyk V, Leshchyns'ka I, Schachner M. Prion protein recruits its neuronal receptor NCAM to lipid rafts to activate p59fyn and to enhance neurite outgrowth. J. Cell Biol. 2005;169:341–354. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200409127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt-Ulms G, Hansen K, Liu J, Cowdrey C, Yang J, DeArmond SJ, Cohen FE, Prusiner SB, Baldwin MA. Time-controlled transcardiac perfusion cross-linking for the study of protein interactions in complex tissues. Nat. Biotechnol. 2004;22:724–731. doi: 10.1038/nbt969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultz J, Schwarz A, Neidhold S, Burwinkel M, Riemer C, Simon D, Kopf M, Otto M, Baier M. Role of interleukin-1 in prion disease-associated astrocyte activation. Am. J. Pathol. 2004;165:671–678. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63331-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharief MK, Green A, Dick JP, Gawler J, Thompson EJ. Heightened intrathecal release of proinflammatory cytokines in Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease. Neurology. 1999;52:1289–1291. doi: 10.1212/wnl.52.6.1289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shull MM, Ormsby I, Kier AB, Pawlowski S, Diebold RJ, Yin M, Allen R, Sidman C, Proetzel G, Calvin D, Annunziata N, Doetschman T. Targeted disruption of the mouse transforming growth factor-beta 1 gene results in multifocal inflammatory disease. Nature. 1992;359:693–699. doi: 10.1038/359693a0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephenson DA, Chiotti K, Ebeling C, Groth D, DeArmond SJ, Prusiner SB, Carlson GA. Quantitative trait loci affecting prion incubation time in mice. Genomics. 2000;69:47–53. doi: 10.1006/geno.2000.6320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoeck K, Bodemer M, Ciesielczyk B, Meissner B, Bartl M, Heinemann U, Zerr I. Interleukin 4 and interleukin 10 levels are elevated in the cerebrospinal fluid of patients with Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease. Arch. Neurol. 2005;62:1591–1594. doi: 10.1001/archneur.62.10.1591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tatzelt J, Maeda N, Pekny M, Yang S-L, Betsholtz C, Eliasson C, Cayetano J, Camerino AP, DeArmond SJ, Prusiner SB. Scrapie in mice deficient in apolipoprotein E or glial fibrillary acidic protein. Neurology. 1996;47:449–453. doi: 10.1212/wnl.47.2.449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tesseur I, Zou K, Esposito L, Bard F, Berber E, Can JV, Lin AH, Crews L, Tremblay P, Mathews P, Mucke L, Masliah E, Wyss-Coray T. Deficiency in neuronal TGF-beta signaling promotes neurodegeneration and Alzheimer's pathology. J. Clin. Invest. 2006;116:3060–3069. doi: 10.1172/JCI27341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thackray AM, McKenzie AN, Klein MA, Lauder A, Bujdoso R. Accelerated prion disease in the absence of interleukin-10. J. Virol. 2004;78:13697–13707. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.24.13697-13707.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomozawa Y, Inoue T, Satoh M. Expression of type I interleukin-1 receptor mRNA and its regulation in cultured astrocytes. Neurosci. Lett. 1995;195:57–60. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(95)11781-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vittinghoff E, Glidden DV, Shiboski SC, McCulloch CE. Regression Methods in Biostatistics: Linear, Logistic, Survival, and Repeated Measures Models. In: Gail M, Krickeberg K, Samet J, Tsiatis A, Wong W, editors. Statistics for Biology and Health. New York: Springer Science+Business Media, Inc.; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- von Koch CS, Zheng H, Chen H, Trumbauer M, Thinakaran G, van der Ploeg LH, Price DL, Sisodia SS. Generation of APLP2 KO mice and early postnatal lethality in APLP2/APP double KO mice. Neurobiol. Aging. 1997;18:661–669. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(97)00151-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westergard L, Christensen HM, Harris DA. The cellular prion protein (PrP(C)): Its physiological function and role in disease. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2007.02.011. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wickner RB, Edskes HK, Shewmaker F, Nakayashiki T. Prions of fungi: inherited structures and biological roles. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2007;5:611–618. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams TM, Cheung MW, Park DS, Razani B, Cohen AW, Muller WJ, Di Vizio D, Chopra NG, Pestell RG, Lisanti MP. Loss of caveolin-1 gene expression accelerates the development of dysplastic mammary lesions in tumor-prone transgenic mice. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2003;14:1027–1042. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E02-08-0503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong BS, Wang H, Brown DR, Jones IM. Selective oxidation of methionine residues in prion proteins. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1999;259:352–355. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1999.0802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wyss-Coray T, Feng L, Masliah E, Ruppe MD, Lee HS, Toggas SM, Rockenstein EM, Mucke L. Increased central nervous system production of extracellular matrix components and development of hydrocephalus in transgenic mice overexpressing transforming growth factor-beta 1. Am. J. Pathol. 1995;147:53–67. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang X, Bhaumik M, Bhattacharyya R, Gong S, Rogler CE, Stanley P. New evidence for an extra-hepatic role of N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase III in the progression of diethylnitrosamine-induced liver tumors in mice. Cancer Res. 2000;60:3313–3319. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng H, Jiang M, Trumbauer ME, Sirinathsinghji DJS, Hopkins R, Smith DW, Heavens RP, Dawson GR, Boyce S, Conner MW, Stevens KA, Slunt HH, Sisodia SS, Chen HY, Van der Ploeg LHT. B-amyloid precursor protein-deficient mice show reactive gliosis and decreased locomotor ability. Cell. 1995;81:525–531. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90073-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.