Abstract

We investigate whether aging leads to global declines in discrete and continuous bimanual coordination tasks thought to rely on different control mechanisms for temporal coupling of the limbs. All conditions of continuous bimanual circle drawing were associated with age-equivalent temporal control. This was also true for discrete simultaneous tapping. Older adults’ between-hand coordination deficits were specific to discrete tapping conditions requiring asynchronous intermanual timing and were associated with self-reported executive dysfunction on the Dysexecutive (DEX) questionnaire. Also, older adults exclusively showed a relationship between the most difficult bimanual circling condition and a measure of working memory. Thus, age-related changes in bimanual coordination are specific to task conditions that place complex timing demands on left and right hand movements and are, therefore, likely to require executive control.

Keywords: Executive Control, Motor Control, Bimanual Coordination, Aging

1. Introduction

Many everyday tasks such as feeding and dressing oneself rely on bimanual coordination. Age-related declines in coordination depend on the type and rate of bimanual performance (Greene & Williams, 1996; Seidler, Alberts & Stelmach, 2002; Serrien, Swinnen & Stelmach, 2000; Stelmach, Amrhein & Goggin, 1988; Swinnen et al., 1998). For example, when aiming at near or far targets, older and younger adults were more accurate for symmetrical (e.g. both hands move to equi-distant targets) than asymmetrical movements (e.g. one hand moves to a near target while the other moves to a far target). Nevertheless, older adults showed more breakdowns in temporal coordination and slower movement execution times than younger adults, especially in the asymmetric condition (Stelmach et al., 1988). Similarly, for bimanual arm or wrist extensions and flexions in the horizontal plane (e.g. perpendicular to the vertical axis of the body) older adults moved more slowly and exhibited more phase shifts back to mirror-symmetric coordination in asymmetric conditions, especially as the required movement rate increased. Thus, older adults have difficulty coordinating asymmetric movements at high speeds and are more susceptible to shifts towards preferred coordination modes than younger adults (Greene & Williams, 1996; Lee, Wishart & Murdoch, 2002; Serrien, Teasdale, Bard & Fleury, 1996; Swinnen et al., 1998; Wishart, Lee, Murdoch & Hodges, 2000). However, it is not clear to what degree age-related changes are systematic across bimanual coordination tasks thought to rely on different mechanisms to achieve temporal coupling between the limbs.

Work has shown that the event structure of bimanual movements may determine the mechanisms engaged to achieve inter-limb temporal coordination. A distinction has been drawn between movements which are discrete, with an explicit pause or landmark between each movement, and those which are continuous, with no pause between motor events (Ivry, Spencer, Zelaznik & Diedrichsen, 2002; Kennerley, Diedrichsen, Hazeltine, Semjen & Ivry, 2002; Robertson et al., 1999). In particular, research with patients who have undergone full corpus callosum (CC) resection shows intact intermanual coupling for discrete, repetitive bimanual tasks but temporal decoupling for simultaneous movements of the hands or fingers during continuous tasks, implicating a role for the CC in control of the latter (Helmuth & Ivry, 1996; Ivry & Hazeltine, 1999; Kennerley et al., 2002). The fact that for synchronous discrete tapping these patients, like healthy controls, maintain interlimb temporal coupling and exhibit reduced within-hand variability when compared to unimanual tapping — known as the “bimanual advantage”–implies that discrete bimanual coordination may rely on subcortical mechanisms (Helmuth & Ivry, 1996; Ivry & Hazeltine, 1999). However, as complexity of the between-hand temporal constraints of discrete movements increases, coordination may rely more on interhemispheric control (Stančák, Cohen, Seidler, Duong & Kim, 2003).

The current study examines whether aging leads to specific or global changes across coordination tasks with different event structures. Participants performed continuous bimanual circle-drawing as well as a discrete tapping task with unimanual, simultaneous bimanual, and asynchronous bimanual conditions. To the extent that normal aging compromises one source of bimanual control over another, we should see specific declines on associated bimanual coordination conditions. Indeed, evidence showing that aging is linked to decreased size and integrity of the CC (Bartzokis et al., 2004; Head et al., 2004; Sullivan, Pfefferbaum, Adalsteinsson, Swan & Carmelli., 2002; however, see Driesen & Raz, 1995; Raz, 2000) suggests that we may find specific declines in continuous bimanual circling, which relies on the CC for inter-limb temporal coordination (Kennerley et al. 2002). Alternatively, aging may lead to deterioration in some common factor such as processing speed (Salthouse, 1996) or inhibitory control (Hasher & Zacks, 1988) that subsequently results in global declines across bimanual coordination tasks. This possibility is supported by demonstrations of increased correlations among diverse sensorimotor and cognitive tasks with increasing age (Baltes & Lindenberger, 1997; Lindenberger & Baltes, 1997). If a global process is at work, we expect age-related impairments across both types of bimanual coordination, even in less demanding conditions (e.g., simultaneous and unimanual tapping). Additionally, older adults should show increased inter-task correlations between bimanual coordination measures and with neuropsychological assessments compared to younger adults.

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

The study protocol and consent were approved by the University of Michigan Institutional Review Board and conformed to the ethical standards of the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki. Seventeen older (M = 72.53 ± 3.79 years; 9 females) and seventeen younger (M = 20.18 ± 1.13 years; 7 females) adults gave informed consent and were paid for their participation. Participants on medication for osteoarthritis or arthrosis reported no problems moving their fingers and arms.

2.2. Procedure

Participants completed two, 2.5 – 3 hour testing sessions, no more than a week apart. The first involved neuropsychological tests (see Table 1 for targeted functions), health questionnaires and continuous circle-drawing. Discrete tapping was performed in session 2. Motor tasks were implemented via custom programs in Labview 6.1 and were administered on a Dell Optiplex GX150 computer. Inclusion criteria were right-handedness and a minimum MMSE score of 27.

Table 1.

Demographics and Neuropsychological Measures

| Demographic Measure/ Neuropsychological Test |

Targeted Functions | Young Adults | Older Adults | d |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Education** | 13.88 (1.17) | 16.12 (2.20) | 1.27 | |

| Handedness* | .75 (.16) | .86 (.13) | .75 | |

| Hours/Week of Exercise | 7.18 (4.08) | 8.47 (8.85) | .19 | |

| Hours/Week Instrument Practice | 1.32 (2.60) | .49 (1.3) | .40 | |

| Hours/Week Typing* | 8.15 (5.30) | 3.88 (4.92) | .84 | |

| Mini-Mental State Exam | General Cognitive Function | 29.59 (.62) | 29.06 (1.09) | .60 |

| DEX | Executive Functions | 21.00 (8.77) | 18.53 (8.74) | .28 |

| Digit Symbol*** | Sensorimotor Processing Speed | 96.06 (12.13) | 68.00 (13.19) | 2.21 |

| Forward Digit Span* | Verbal Working Memory | 12.65 (1.58) | 11.06 (2.56) | .75 |

| Backward Digit Span | Verbal Working Memory | 8.88 (2.32) | 8.00 (2.37) | .38 |

| Reading Span* (# items remembered) | Verbal Working Memory | 31.71 (4.73) | 27.47 (5.87) | .80 |

| Trails A & B* (Difference Score – seconds) | Set Switching; Executive Functions | 24.00 (17.09) | 37.00 (15.69) | .79 |

| STROOP*** | Response Inhibition | 19.12 (7.78) | 28.53 (6.39) | 1.32 |

| WAIS Vocabulary | Semantic Memory | 50.24 (7.42) | 53.76 (5.49) | .54 |

p < .05,

p < .01,

p< .001

Note: Reported values are the means for each group. Standard deviation scores are shown in parentheses. Cohen’s d is reported as the measure of effect size. The neuropsychological tests include the Edinburgh Handedness Inventory ( Oldfield, 1971), the Mini-Mental State Exam (MMSE) (Folstein, Folstein & McHugh,1975), reading span (Daneman & Carpenter, 1980), the Trail-Making A & B task from the Halstead-Reitan test battery (Reitan & Wolfson, 1985), the vocabulary, digit-symbol substitution, forward digit span, and backward digit span tasks from the WAIS-R (Wechsler, 1981), the Stroop task (Stroop, 1935), and the DEX (dysexecutive syndrome) questionnaire (Wilson, Evans & Emslie, 1996).

2.2.1. Continuous Circle-Drawing

Participants drew circles (maximum diameter of ~ 6 cm) using two dual-potentiometer joysticks positioned ten inches in front of them and aligned with the shoulders. Arm rests limited movements to the wrists and fingers. Participants completed four conditions at their self-determined preferred and maximum circling rates. Two were mirror-symmetric where one hand circled clockwise and the other counter-clockwise, and two were asymmetric, where the hands circled in the same direction. On each trial participants circled continuously for 15 seconds while keeping their hands synchronized. There were three blocks of trials for each condition, with block order pseudo-randomized—a full block of each condition, with three trials each of preferred and maximum speed circling, was completed before any were repeated. Data were sampled at a rate of 1000 Hz and smoothed with a Butterworth low pass filter with a cut-off frequency of 10 Hz. Participants were not given practice or feedback.

2.2.2. Discrete, Repetitive Finger Tapping

Participants tapped with their index fingers in the following conditions:

Right Hand Only (unimanual); R

Left Hand Only (unimanual); L

Simultaneous (0 ms lag; bimanual); Sim

Right-Leads-Left (180 ms lag; bimanual); RL

Left-Leads-Right (180 ms lag, bimanual); LR

Five, 30-second trials of each condition were completed at three inter-tap intervals (ITI): 800 ms (fast), 1000 ms (medium), and 1200 ms (slow), randomized across run order. Participants pressed buttons on response boxes ten inches in front of them. On each trial, they fixated on a point centered in an 11.5 cm × 11.5 cm white display box on the computer screen. Green circles (~ 13 mm diameter) flashed 2 cm from either side of fixation at the given ITI to pace participants; side of presentation corresponded with tapping hand.

A trial was valid if each tap fell within the target ITI ± 300 ms. Invalid trials were repeated up to 3 times. Approximately 4% of younger and 18% of older adults’ trials were invalid1. One older adult with no valid LR trials was omitted from the tapping analyses. Though not given practice, participants received within-hand feedback after each trial.

2.3. Data Analysis

For circling, we calculated average rate and average absolute lag between hands using data from the longest period of each trial with no changes in direction or other disruptions (Kennerley et al., 2002); we excluded trials (2 % for older adults and 3.27 % for younger adults) where stable movement patterns were maintained for less than 3 seconds. Corrected lag2 was determined for all conditions and subsequently averaged across repetitions and condition type (mirror-symmetric and asymmetric); this measure indicated how well the hands stayed temporally-coupled. We conducted a mixed repeated-measures ANOVA on corrected lag with circling condition (2) and instructed speed (2) as within-subjects variables and age-group (2) as the between-subjects variable, using α = .05.

Tapping dependent variables included rate and within-hand standard deviation of rate to assess intertap interval (ITI) consistency within each hand. Between-hand standard deviation of lag3 reflects the ability to maintain the between-hand temporal lag goal (e.g. Sim = 0 ms, asynchronous = 180 ms). Data were acquired for each trial and averaged across repetitions.

Mixed repeated-measures ANOVAs were conducted using within-subjects variables of tapping condition (4: unimanual, Sim, RL, and LR), hand (2) and ITI (3) for analysis of within-hand standard deviation, and condition (3) and ITI (3) for analysis of between-hand standard deviation. Age-group (2) was the between-subjects variable. Significance was α = .05 and the Huynh-Feldt adjustment was reported for sphericity violations. A planned paired t-test between Sim and unimanual tapping, α = .05, one-tailed, assessed the bimanual advantage in older adults.

Intra-task correlations were conducted at Bonferroni-corrected α = .05, one-tailed. All other correlations and post-hoc comparisons used Bonferroni-corrected α = .05, two-tailed. With power = .80 and a correlation amongst repeated measures of r = .50, we can detect the following effect sizes for between-hand measures (age effect: circling η2 = .16, tapping η2 = .14; age × condition interaction: circling η2 = .06, tapping η2 = .05) 4.

3. Results

3.1. Neuropsychological Tests and Additional Measures

Table 1 shows the two-tailed independent t-test comparisons of age groups.

3.2. Circling

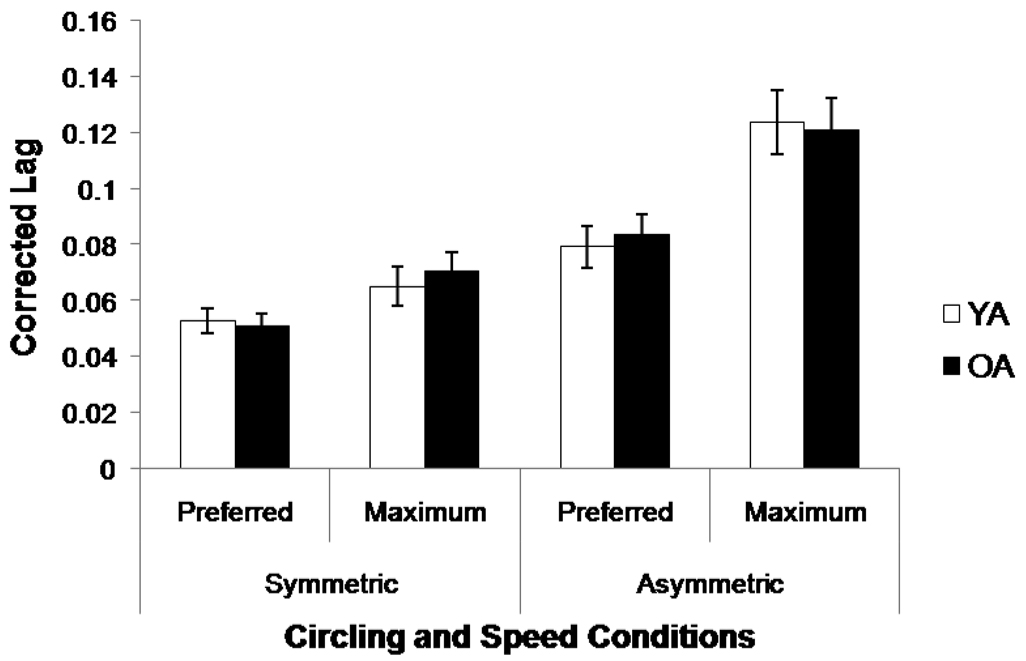

There was no age group difference in the trial length from which temporal coupling measures were obtained. Figure 1 shows that older and younger adults performed similarly on both symmetric and asymmetric circling; there was no age group effect or interactions with this variable (all η2 < .001 for the main effect and two-way interactions with age group; η2 = .003 for the three-way interaction). There were effects of instructed speed, F(1, 32) = 37.45, p < .001, η2 = .17, and condition, F(1, 32) = 48.45, p < .001, η2 = .37, as well as a speed × condition interaction, F(1, 32) = 19.77, p < .001, η2 = .03. Poorer coordination was seen in asymmetric conditions and at the maximum rate.

Figure 1.

Corrected lag for the circling conditions. Error bars represent ± 1 standard error from the mean.

3.3. Tapping

3.3.1. Within-Hand Measures

There was no effect of age group or interactions with age group on tapping rate; groups had rates comparable to the paced ITIs (800: M = 788; 1000: M = 991; 1200: M = 1193). For standard deviation of tapping rate, we found an effect of age group, F(1, 31) = 6.53, p < .05, η2 = .17; older adults tapped less consistently (M = 61) than younger adults (M = 53). Despite this, older adults showed the bimanual advantage, t(15) = 2.45, p < .05, d = .46, at a level (4.83 ms) comparable to previous reports for healthy young adults (Drewing & Aschersleben, 2003; Helmuth & Ivry, 1996). There were significant effects of tapping condition, F(3, 93) = 4.05, p < .01, η2 = .02, and ITI, F(2, 57) = 120.68, p < .001, η2 = .37. Post-hoc tests revealed poorer performance with longer ITIs (800: M = 47; 1000: M = 56; 1200: M = 68). Neither the effect of hand nor any interactions with age were reliable (all η2 < .01).

3.3.2. Between-Hand Measures

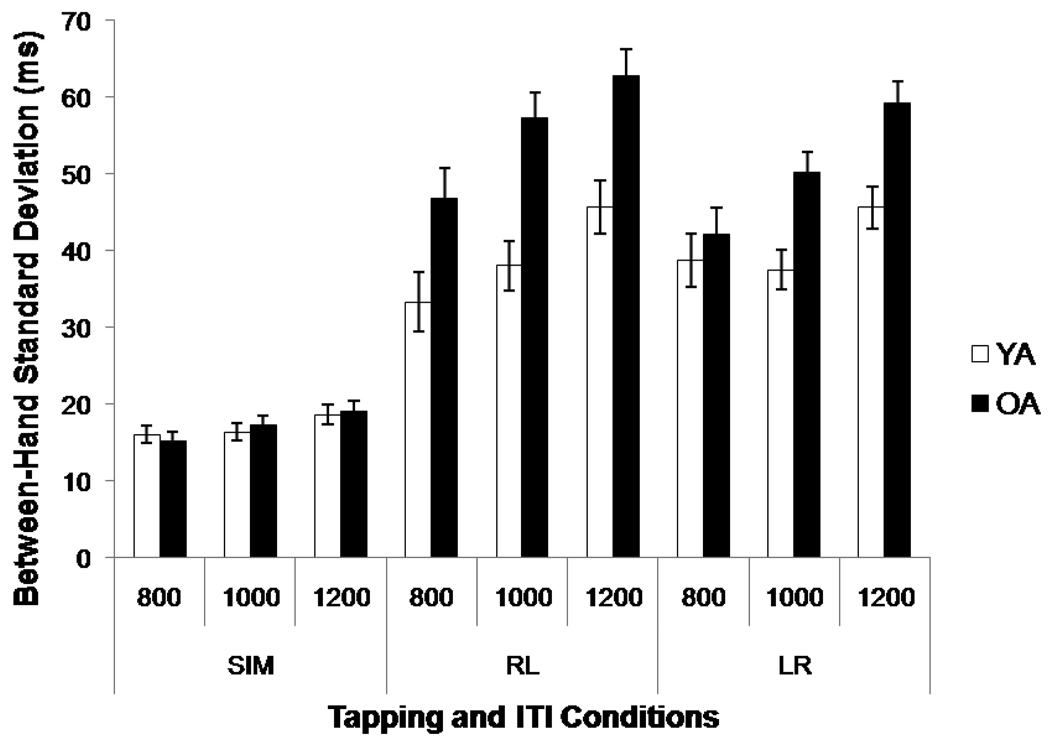

Figure 2 illustrates between-hand performance on the bimanual tapping conditions. There was an effect of age group, F(1, 31) = 11.35, p < .01, η2 = .27, and an age group × condition interaction (F(2, 62) = 11.89, p < .001, η2 = .04)5; while older and younger adults performed equivalently during the Sim condition [(Old: M = 17, Young: M = 17), p = .86, d =.04] older adults were more variable in asynchronous tapping conditions [RL: (Old: M = 56, Young: M = 39), t(32) = −4.15, p < .001, d = 1.42; LR: (Old: M = 50, Young: M = 41), t(32) = −2.90, p < .01, d =1.01]. The effects of ITI, F(2, 62) = 43.22, p < .001, η2 = .06 and condition, F(2, 62) = 199.57, p < .001, η2 = .66, were also significant, but older adults had more difficulty than younger adults at slower ITIs (age group × ITI: F(2, 62) = 4.17, p < .05, η2 = .01). The effect of ITI across all participants also differed by condition (condition × ITI: F(3, 97) = 5.29, p < .01, η2 = .01). Paired t-tests comparing the two asynchronous conditions revealed no difference for younger adults, p = .27, but better coordination for LR versus RL tapping, t(15) = 2.16, p < .05, d = .45, in older adults.

Figure 2.

Between-hand standard deviation for the bimanual tapping conditions (Sim, RL, LR) across inter-tap intervals (ITI) for older (OA) and younger (YA) adults. Error bars represent ± 1 standard error from the mean.

3.4. Correlations

Table 2 shows significant bimanual intra-task correlations for each age group. Neither group showed between task relationships across these measures, suggesting common control mechanisms are engaged within but not across domains with differing event structures, as has been found previously for young adults (Robertson et al., 1999). Young adults showed no correlations between bimanual and neuropsychological measures, all p > .90. However, for older adults higher working memory span on the Backward Digit Span (BDS) task was associated with better coordination on the hardest circling condition (asymmetric at the maximum speed), r = −.72, p = .001, and poorer self-reported executive control (DEX) was related to poorer performance for LR tapping, r = .73, p = .001.

Table 2.

Intra-task Correlations Between Bimanual Coordination Measures

| Circling | ||||

| SYMMETRIC P vs. M |

PARALLEL P vs. M |

MAXIMUM SYM vs. ASYM |

PREFERRED SYM vs. ASYM |

|

| OA | .67** | .57* | ---- | ---- |

| YA | .64* | .60* | ---- | ---- |

| Tapping | ||||

| SIM vs. RL | Sim vs. LR | RL vs. LR | ||

| OA | .62* | .54* | .73** | |

| YA | ---- | ---- | .87*** | |

p < .05,

p < .01,

p<.001, Bonferroni Corrected

Note: YA = Younger Adults, OA = Older Adults, P = Preferred speed, M = Maximum speed, SYM = Symmetric circling conditions, ASYM = Asymmetric circling conditions, SIM = Simultaneous bimanual tapping, RL = Right leads left bimanual tapping, LR = Left leads right bimanual tapping.

4. Discussion

We investigated whether age-related deficits in bimanual coordination point to declines in task-specific (continuous versus discrete) sources of control or more global declines with age. Neither hypothesis was supported. Instead, older adults had problems with temporally asynchronous discrete tasks. Moreover, correlational results suggest increased reliance on executive processes to achieve interlimb coordination in high difficulty conditions of both discrete and continuous tasks.

Older participants performed similarly to younger adults on continuous circle-drawing and simultaneous tapping, and they also exhibited the “bimanual advantage” (Drewing & Aschersleben, 2003; Helmuth & Ivry, 1996). We want to emphasize that we are not claiming that these results indicate an absence of age differences on these measures, rather the presence of relative age preservation. However, given the extremely small size of the effects for the age group comparisons on these tasks, we are confident that if differences are present in the population they are quite small. Preservation of interlimb coordination in simultaneous tapping was evident despite poorer unimanual performance. This counters the idea that aging leads to functionally-specific declines in either CC- or subcortically-mediated aspects of bimanual control. The absence of inter-task correlations or broad correlations between bimanual and neuropsychological measures for older adults further argues against some global deficit or common cause underlying age-related changes in bimanual coordination (Baltes & Lindenberger, 1997; Lindenberger & Baltes, 1997). Our results do not link bimanual declines to age-related changes in some fundamental cognitive process either, as indicated by the absence of pervasive correlations between bimanual performance measures in older adults and our measures of processing speed (Salthouse, 1996) and inhibitory control (Hasher & Zacks, 1988). Only correlations between the most difficult coordination conditions in each task and a single measure of working memory (BDS) and self-reported executive dysfunction (DEX) proved significant. It is worth mentioning that the BDS was the only neuropsychological measure to approach a significant correlation with the DEX (p = .07, uncorrected) across all participants. Thus, older adults may engage executive processes to support performance of difficult motor tasks (Heuninckx, Wenderoth, Debaere, Peeters & Swinnen, 2005).

Older adults were worse than younger adults on asynchronous discrete tapping conditions. Perhaps older adults are more sensitive to increases in task difficulty, as has been found in other task domains (Bopp & Verhaegen, 2005; Jenkins, Myerson, Joerding & Hale, 2000; Mattay et al., 2006; Mayr & Kliegl, 1993). The automatic versus controlled processing framework (Schneider & Shiffrin, 1977) offers an instructive way to consider our results. While simple coordination is performed relatively automatically, increasing task difficulty causes greater reliance on attentional and executive control. Older adults often show more performance breakdowns relative to younger adults at the same level of task demand (Lee, Wishart & Murdoch, 2002; Wishart et al., 2000) and have a harder time acquiring and maintaining novel or difficult patterns of bimanual coordination (Swinnen et al., 1998; Wishart et al., 2000). They even show breakdowns on well-practiced functions, such as postural control, in the presence of cognitively-demanding secondary tasks (Huxhold, Li, Schmiedek & Lindenberger, 2006). Neuroimaging reveals increased brain activation for both age groups in regions linked to working memory and inhibitory function when cognitive and motor coordination task demands increase (Druzgal & D’Esposito, 2001; Heuninckx et al., 2005; Jonides, Schumacher & Smith, 1997; Reuter-Lorenz, 2002; Reuter-Lorenz & Lustig, 2005). When behavioral performance is equated, older adults show greater activation in prefrontral cortical regions typically involved in executive control compared to younger adults (Heuninckx et al., 2005, Hutchinson, et al., 2002; Mattay et al., 2002; see Reuter-Lorenz, 2002 and Reuter-Lorenz & Cappell, 2008 for relevant reviews).

Why did age differences emerge for asynchronous tapping but not maximum-speed asymmetric circling, another high difficulty condition? Asynchronous coordination demands for tapping may have posed a greater challenge for older adults which could not be met by recruitment of executive strategies. Indeed, group differences in the number of dropped tapping trials but not in the length of the longest trial periods for circling support this view. The interplay between ITI and the required asynchronous phase delay may have played a role. For bimanual measures, slower ITI had no effect on simultaneous tapping (no phase delay) but compromised asynchronous conditions where the ratio of the phase delay to the target ITI decreased as ITI increased (800 ms: ø = .225; 1000 ms: ø = .180; 1200: ø = .150). Tapping is more difficult at phase delays that divide the total response cycle into unequal subintervals, especially when delays are extreme (e.g. ø = 0.1 or 0.9) (Semjen & Ivry, 2001). Symmetric and asymmetric circle-drawing did not require phase delays, which may explain the lack of age differences in these conditions. Sequences of multiple discrete finger opposition movements, associated with anterior CC control, likely increase the difficulty of a symmetric coordination condition and might have lead to age group effects if used in our study (Bonzano et al, 2008; Wahl & Ziemann, 2008).

Future studies should assess difficulty effects in asynchronous continuous tasks as well as discrete tasks involving multi-finger sequences and include fiber tract imaging of the CC to fully evaluate the relationships between aging, CC integrity, and bimanual control. In particular, it is important to establish how CC integrity contributes to age-related declines in asynchronous coordination between the hands. Remarkably, in all conditions that required bimanual synchrony older and younger adults performed equivalently. This hints that motor strategies accessing preserved control mechanisms for synchronous movements could be developed to assist older adults in executing more complex movements. Thus, evidence for compensation in cognitive domains (Cabeza, 2002; Reuter-Lorenz & Cappell, 2008) may be applicable to the development of physical training protocols designed to improve upper limb mobility during senescence.

Acknowledgments

We thank the following undergraduates for their assistance with data collection and analysis: Dhara Naik, Janeane Bolhouse, Stacey Reaume, Devika Suri, and Emily Anderson. This work was supported by NIH AG024106 (RDS), AG18286 (PARL), the UM Claude D. Pepper OAIC Research Career Development, Pilot Grant, and Human Subjects Cores (NIA AG08808) and a National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship (ASB).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

An analysis of the number of invalid trials in this task showed that older adults had significantly more invalid trials than younger adults, especially for asynchronous conditions.

A repeated measures ANOVA on adopted circling rate found no age group differences or interactions with age group on this measure, indicating that older and younger adults circled at similar rates across all conditions and speed instructions. Nevertheless, minor differences in circling rate could add noise to the measure of between hand lag, because slower performance speed on some motor tasks is associated with greater performance variability (cf. Rosenbaum, 2002). Therefore, we calculated corrected lag by dividing each individual’s average absolute lag by their average circling rate. Analyses using uncorrected absolute lag yielded group results which paralleled those found with the corrected measure.

This measure is akin to the standard deviation of relative phase used by Kennerley and colleagues (2002). We report standard deviation instead of CV for two reasons: 1) we found no age effects on tapping rate, therefore normalizing variability by tapping rate was unnecessary and 2) the appropriate calculation of CV would involve dividing the standard deviation of lag by the average lag between hands. However, since the average lag could be negative (in reference to whichever hand should be in the lead position), the denominator of the CV calculation could also take on negative values, which is problematic. In response to a reviewer suggestion, we calculated a version of the CV where mean tapping rate was included in the denominator. When this measure was examined, we still found significant main effects of age group, condition and ITI all p < .01. There was also an age group × condition interaction, p < .001. No other interactions were significant. The presence of the age group and age group × condition interactions confirm that our age-related effects were due to actual differences in between-hand lag consistency, independent of tapping rate.

All power calculations were conducted using G*Power 3.1.0 (Faul, Erdfelder, Lang, & Buchner , 2007) and Cohen’s f values were converted to η2.

As indicated in footnote 3, we also conducted these analyses using a coefficient of variation measure. The results of this analysis did not significantly change the results.

References

- Baltes PB, Lindenberger U. Emergence of a powerful connection between sensory and cognitive functions across the adult life span: a new window to the study of cognitive aging? Psychology of Aging. 1997;12:12–21. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.12.1.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartzokis G, Sultzer D, Lu PH, Nuechterlein KH, Mintz J, Cummings JL. Heterogeneous age-related breakdown of white matter structural integrity: Implications for cortical 'disconnection' in aging and Alzheimer's disease. Neurobiology of Aging. 2004;25(7):843–851. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2003.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonzano L, Tacchino A, Abbruzzese G, Mancardi GL, Bove M. Callosal contributions to simultaneous bimanual finger movements. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2008;28(12):3227–3233. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4076-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bopp KL, Verhaegen P. Aging and verbal memory span: a meta-analysis. Journal of Gerontology: Psychological Sciences. 2005;60B(5):P223–P233. doi: 10.1093/geronb/60.5.p223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabeza R. Hemispheric asymmetry reduction in older adults: the HAROLD model. Psychology and Aging. 2002;17(1):85–100. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.17.1.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daneman M, Carpenter PA. Individual differences in working memory and reading. Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior. 1980;19:450–466. [Google Scholar]

- Drewing K, Aschersleben G. Reduced timing variability during bimanual coupling: a role for sensory information. The Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology. 2003;56A(2):329–350. doi: 10.1080/02724980244000396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Driesen NR, Raz N. The influence of sex, age, and handedness on corpus callosum morphology: A meta-analysis. Psychobiology. 1995;23(3):240–247. [Google Scholar]

- Druzgal TJ, D'Esposito M. Activity in fusiform face area modulated as a function of working memory load. Cognitive Brain Research. 2001;10(3):355–364. doi: 10.1016/s0926-6410(00)00056-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faul F, Erdfelder E, Lang A-G, Buchner A. G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behavior Research Methods. 2007;39:175–191. doi: 10.3758/bf03193146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. Mini-Mental State: A practical method for grading the state of patients for the clinician. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 1975;12:189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerloff C, Andres FG. Bimanual coordination and interhemispheric interaction. Acta Psychologica. 2002;110(2–3):161–186. doi: 10.1016/s0001-6918(02)00032-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greene LS, Williams HG. Aging and coordination from the dynamic pattern perspective. In: Ferrandez A, editor. Changes in sensory motor behavior in aging. New York, NY: Elsevier Science; 1996. pp. 89–131. [Google Scholar]

- Hasher L, Zacks RT. Working memory, comprehension, and aging: A review and a new view. In: Bower GH, editor. The psychology of learning and motivation. Vol. 22. San Diego, CA, US: Academic Press, Inc; 1988. pp. 193–225. [Google Scholar]

- Head D, Buckner RL, Shimony JS, Williams LE, Akbudak E, Conturo TE, et al. Differential Vulnerability of Anterior White Matter in Nondemented Aging with Minimal Acceleration in Dementia of the Alzheimer Type: Evidence from Diffusion Tensor Imaging. Cerebral Cortex. 2004;14(4):410–423. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhh003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helmuth LL, Ivry RB. When two hands are better than one: Reduced timing variability during bimanual movements. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception & Performance. 1996;22(2):278–293. doi: 10.1037//0096-1523.22.2.278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heuninckx S, Wenderoth N, Debaere F, Peeters R, Swinnen SP. Neural Basis of Aging: The Penetration of Cognition into Action Control. Journal of Neuroscience. 2005;25(29):6787–6796. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1263-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutchinson S, Kobayashi M, Horkan CM, Pascual-Leone A, Alexander MP, Schlaug G. Age-Related Differences in Movement Representation. NeuroImage. 2002;17:1720–1728. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2002.1309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huxhold O, Li S, Schmiedek F, Lindenberger U. Dual-tasking postural control: aging and the effects of cognitive demand in conjunction with focus of attention. Brain Research Bulletin. 2006;69:294–305. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2006.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivry RB, Hazeltine E. Subcortical locus of temporal coupling in the bimanual movements of a callosotomy patient. Human Movement Science. 1999;18(2–3):345–375. [Google Scholar]

- Ivry RB, Spencer RM, Zelaznik HN, Diedrichsen J. The cerebellum and event timing. In: Highstein SM, Thach WT, editors. The Cerebellum: Recent Developments in Cerebellar Research. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. Vol. 978. New York: New York Academy of Sciences; 2002. pp. 302–317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins L, Myerson J, Joerding JA, Hale S. Converging evidence that visuospatial cognition is more age-sensitive than verbal cognition. Psychology and Aging. 2000;15(1):157–175. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.15.1.157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonides J, Schumacher EH, Smith EE. Verbal working memory load affect regional brain activation as measured by PET. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 1997;9(4):462–475. doi: 10.1162/jocn.1997.9.4.462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennerley SW, Diedrichsen J, Hazeltine E, Semjen A, Ivry RB. Callosotomy patients exhibit temporal uncoupling during continuous bimanual movements. Nature Neuroscience. 2002;5(4):376–381. doi: 10.1038/nn822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee TD, Wishart LR, Murdoch JE. Aging, attention, and bimanual coordination. Canadian Journal on Aging. 2002;21(4):549–557. [Google Scholar]

- Lindenberger U, Baltes PB. Intellectual functioning in old and very old age: cross-sectional results from the Berlin aging study. Psychology & Aging. 1997;12:410–432. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.12.3.410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattay VS, Fera F, Tessitore A, Hariri AR, Berman KF, Das S, et al. Neurophysiological correlates of age-related changes in working memory capacity. Neuroscience Letters. 2006;392:32–37. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2005.09.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattay VS, Fera F, Tessitore A, Hariri AR, Das S, Callicot JH, et al. Neurophysiological correlates of age-related changes in human motor function. Neurology. 2002;58(4):630–635. doi: 10.1212/wnl.58.4.630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayr U, Kliegl R. Sequential and coordinative complexity: age-based processing limitations in figural transformations. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition. 1993;19(6):1297–1320. doi: 10.1037//0278-7393.19.6.1297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oldfield RC. The assessment and analysis of handedness: The Edinburgh inventory. Neuropsychologia. 1971;9(1):97–113. doi: 10.1016/0028-3932(71)90067-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raz N. Aging of the brain and its impact on cognitive performance: Integration of structural and functional findings. In: Craik FIM, Salthouse TA, editors. The handbook of aging and cognition. 2nd ed. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Publishers; 2000. pp. 1–90. [Google Scholar]

- Reitan RM, Wolfson D. The Halstead-Reitan Neuropsychological Test Battery. Tuscon, AZ: Neuropsychology Press; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Reuter-Lorenz PA. New visions of the aging mind and brain. Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 2002;6(9):394–400. doi: 10.1016/s1364-6613(02)01957-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reuter-Lorenz PA, Cappell K. Neurocognitive aging and the compensation hypothesis. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2008;18(3):177–182. [Google Scholar]

- Reuter-Lorenz PA, Lustig C. Brain aging: reorganizing discoveries about the aging mind. Current Opinion in Neurobiology. 2005;15(2):245–251. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2005.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson SD, Zelaznik HN, Lantero DA, Bojczyk KG, Spencer RM, Doffin JG, Schneidt T. Correlations for timing consistency among tapping and drawing tasks: Evidence against a single timing process for motor control. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance. 1999;25(5):1316–1330. doi: 10.1037//0096-1523.25.5.1316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenbaum DA. Time, space, and short-term memory. Brain and Cognition, 48(1), Special issue: Human movement timing and coordination. 2002:52–65. doi: 10.1006/brcg.2001.1303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salthouse TA. The processing-speed theory of adult age differences in cognition. Psychological Review. 1996;103:403–428. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.103.3.403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider W, Shiffrin RM. Controlled and automatic human information processing: I. Detection, search, and attention. Psychological Review. 1977;84(1):1–66. [Google Scholar]

- Seidler RD, Alberts JL, Stelmach GE. Changes in multi-joint performance with age. Motor Control. 2002;6(1):19–31. doi: 10.1123/mcj.6.1.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Semjen A, Ivry RB. The coupled oscillator model of between-hand coordination in alternate-hand tapping: a reappraisal. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance. 2001;27(2):251–265. doi: 10.1037//0096-1523.27.2.251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serrien DJ, Swinnen SP, Stelmach GE. Age-related deterioration of coordinated interlimb behavior. Journals of Gerontology: Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2000;55B(5):P295–P303. doi: 10.1093/geronb/55.5.p295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serrien DJ, Teasdale N, Bard C, Fleury M. Age-related differences in the integration of sensory information during the execution of a bimanual coordination task. Journal of Motor Behavior. 1996;28(4):337–347. doi: 10.1080/00222895.1996.10544603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stančák A, Cohen ER, Seidler RD, Duong TQ, Kim S. The size of corpus callosum correlates with functional activation of medial motor cortical areas in bimanual and unimanual movements. Cerebral Cortex. 2003;3(5):475–485. doi: 10.1093/cercor/13.5.475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stelmach GE, Amrhein PC, Goggin NL. Age differences in bimanual coordination. Journals of Gerontology. 1988;43(1):P18–P23. doi: 10.1093/geronj/43.1.p18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stroop JR. Studies of interference in serial verbal reactions. Journal of Experimental Psychology. 1935;12:643–662. [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan EV, Pfefferbaum A, Adalsteinsson E, Swan GE, Carmelli D. Differential rates of regional brain change in callosal and ventricular size: A 4-year longitudinal MRI study of elderly men. Cerebral Cortex. 2002;12(4):438–445. doi: 10.1093/cercor/12.4.438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swinnen SP, Verschueren SMP, Bogaerts H, Dounskaia N, Lee TD, Stelmach GA, et al. Age-related deficits in motor learning and differences in feedback processing during the production of a bimanual coordination pattern. Cognitive Neuropsychology. 1998;15(5):439–466. doi: 10.1080/026432998381104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wahl M, Ziemann U. The human motor corpus callosum. Reviews in the Neurosciences. 2008;19:451–466. doi: 10.1515/revneuro.2008.19.6.451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler D. Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale-Revised. San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson BA, Evans JJ, Emslie H. The development of an ecologically valid test for assessing patients with dysexecutive syndrome. Neuropsychological Rehabilitation. 1996;8(3):213–228. [Google Scholar]

- Wishart LR, Lee TD, Murdoch JE, Hodges NJ. Effects of aging on automatic and effortful processes in bimanual coordination. Journal of Gerontology: Psychological Sciences. 2000;55B(2):P85–P94. doi: 10.1093/geronb/55.2.p85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]