Abstract

BACKGROUND

Whether bacterial vaginosis (BV) is sexually transmitted is uncertain. Also it is unknown why BV is approximately twice as prevalent among African-American as among white women. An association of BV with a characteristic of the male sex partner, such as race, might support sexual transmission as well as account for the observed ethnic disparity in BV.

METHODS

3620 non-pregnant women 15–44 years of age were followed quarterly for 1 year. At each visit, extensive questionnaire data and vaginal swabs for Gram’s staining were obtained. The outcome was transition from BV-negative to positive (Nugent’s score ≥7) in an interval of 2 consecutive visits.

RESULTS

BV occurred in 12.8% of 906 sexually active intervals to white women- 24.8% of intervals when the woman reported an African-American partner and 10.7% when all partners were white. Among white women, there was a two-fold increased risk for BV incidence with an African-American, compared with a white partner (risk ratio (RR) 2.3, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.6–3.4; adjusted RR 2.2, 95% CI 1.5–3.4), but differed according to condom use. In the presence of consistent condom use, the adjusted RR was 0.7 (0.3–2.4); it was 2.4 (1.0–6.2) in the presence of inconsistent use; and 2.7 (1.7–4.2) in the absence of condom use. African-American women could not be studied, as there were insufficient numbers who reported only white male sex partners.

CONCLUSION

The association of BV occurrence with partner’s race, and its blunting by condom use, suggests that BV may have a core group component and may be sexually transmitted.

Keywords: bacterial vaginosis, sexual transmission, health disparities

Bacterial vaginosis (BV) is traditionally described as a condition in which the usual Lactobacillus-dominant vaginal bacteria are replaced by overgrowth of Gardnerella vaginalis and mixed, predominantly anaerobic organisms.1 BV is the most common cause of symptomatic vaginal discharge in reproductive-age women, and has been associated with serious health consequences such as preterm birth,2 postoperative gynecologic infection,3 and acquisition of HIV4 and other sexually transmitted organisms.5 The etiology of BV is unknown, and whether it is a sexually transmitted infection is controversial.6 Personal hygiene behaviors, particularly douching, have also been associated with BV.7,8

African-American women consistently have been found to be at doubled or greater risk of having prevalent BV compared to white women,9,10 although the reason is not known. Demographic factors such as less education, and behavioral factors such as douching, although more common among African-American women, do not explain the difference.11 Recently, the race of the male sex partner has been associated with prevalent BV in the first trimester of pregnancy.12 Among white women, when the father of the pregnancy was African-American, the prevalence of BV was 45.7%, compared with 20.9% when the father was white.12 The association of BV with a characteristic of the male might provide support for sexual transmission of BV, and it also suggests that difference in social networks13 between white and African-American women might account for the strong racial differences in this condition. We conducted this analysis to study the association between the race of the male sex partner and incident BV in a longitudinal cohort of non-pregnant women.

METHODS

This report is from the Longitudinal Study of Vaginal Flora, previously described.14 Non-pregnant women aged 15–44 were recruited from August 1999 to February 2002, when they presented for a routine health care visit to 1 of 12 clinics in the Birmingham, Alabama area. Women were ineligible if they had significant medical or gynecological conditions, were planning to move from the area in the next 12 months, or had conditions precluding informed consent. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the University of Alabama at Birmingham, the Jefferson County, Alabama Department of Health, and the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. All participants provided written informed consent.

Women were seen at a research clinic for an initial study visit, and then for quarterly visits, for one year of follow-up. At each visit women underwent a detailed interview in a private office with a female interviewer. The interview was focused on lower genital tract symptoms, personal hygienic and sexual behaviors, and also obtained information on demographic factors, stress, and substance use. Relevant to this analysis, the sexual behaviors assessed at each follow-up visit included frequency of vaginal, oral, and anal intercourse over the past 3 months; the sex and race of each sexual partner (up to 12) during that interval; and the fraction of vaginal sex acts over the past month during which a condom was used.

Each study visit also included a pelvic examination where a cotton swab was obtained for vaginal Gram stain, which was evaluated for BV by the Nugent method.15 Ten percent of samples were independently evaluated in a different laboratory; the kappa coefficient for the classification of BV was 0.81. BV was defined as a Nugent score of 7–10 and women with scores of 0–6 were considered BV-negative. The interviewers were unaware of laboratory results and the laboratory personnel were unaware of interview results.

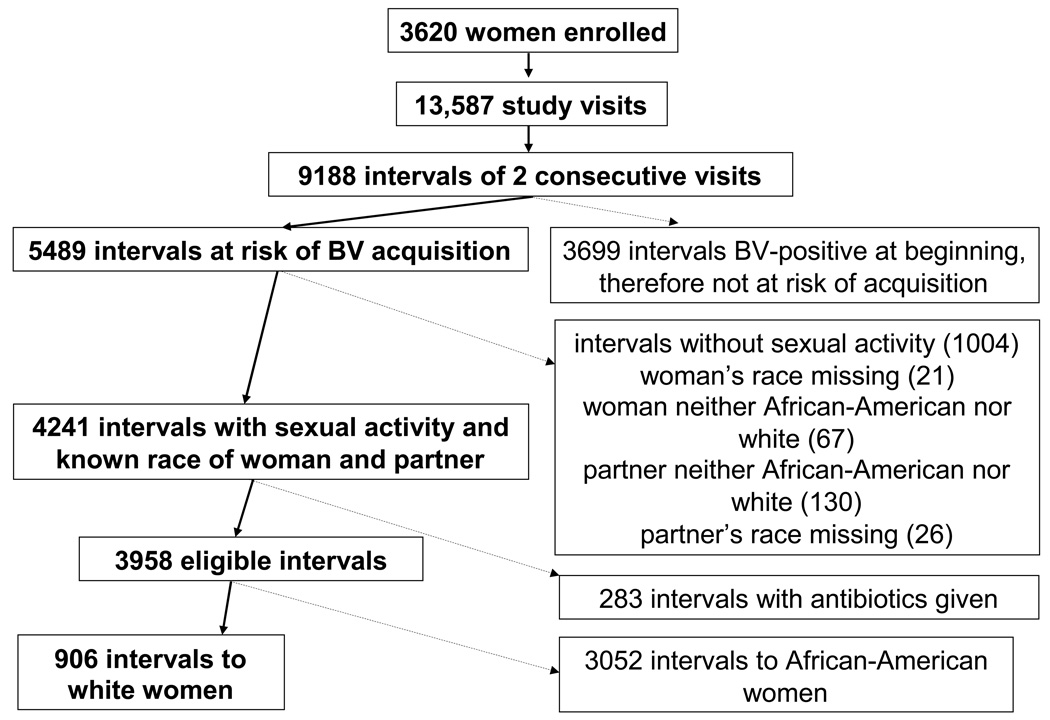

The unit of analysis for this report is the interval of 2 consecutive study visits. The outcome is “incident” BV, defined as a change from BV-negative to BV-positive in an interval. Intervals at risk for incident BV were those where the woman was BV-negative at the first of the two visits. Thus, a woman could have up to 4 at risk intervals (from visits 1 to 2, 2 to 3, 3 to 4, and 4 to 5) and 0, 1 or 2 BV-incident events. Intervals where the woman was already BV-positive at the beginning were not at risk for the development of BV and were therefore excluded. Intervals where a woman reported no male partners for vaginal, oral or anal sex were excluded from analysis, as were all intervals to women whose race was neither African-American nor white, and intervals where the sex partner’s race was missing. We also excluded all intervals to women who reported at any time during the study a sex partner who was neither African-American nor white. Finally we excluded intervals in which a woman received either metronidazole or clindamycin. Details are provided in Figure 1. When a woman reported both African-American and white male sex partners in a given interval, she was classified as having an African-American partner.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of derivation of study population. Bold text and arrows represent remaining intervals, non-bold text and dashed arrows represent exclusions.

Since each woman could both contribute multiple intervals at risk for BV and experience more than 1 incidence of BV, the observations are not independent. Generalized Estimating Equations16 were used to estimate the correct standard errors. Significance of differences in percentages was based on logistic regression, and risk ratios and confidence intervals were derived from the coefficients and standard errors of a modified Poisson regression with robust variance.17 We evaluated the significance of risk factors, and of interactions between partner’s race and other characteristics with the score statistic; interactions with a p-value of ≤0.10 were pursued further by estimating risk ratios separately for women with and without the interacting factor. Analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.1.3.

RESULTS

The prospective, longitudinal Flora study enrolled 3620 women who contributed 13,587 study visits. As detailed in Figure 1, these visits generated 9188 intervals of 2 consecutive visits. BV appeared in 924 (23.4%) of the 3958 eligible intervals—116 (12.8%) of the 906 intervals in white women and 808 (26.5%) of the 3052 intervals in African-American women (p<0.001). African-American women reported having exclusively white male sex partners in 14 (0.5%) of their 3052 sexually active intervals; this small number precluded analysis of the association between occurrence of BV and male partner’s race in these women. Seventy-three of the 380 white women reported having a male African-American sex partner, representing 133 (14.7%) of 906 sexually active intervals. The 906 intervals to 380 white women form the population for detailed analysis (Figure 1).

The associations between sexual behaviors and partner’s race are presented in Table 1. Table 1 and Table 2 also present associations between partner’s race and other factors of a priori interest. Women reported only one male sex partner in 95% of intervals; new sex partners were relatively uncommon (8% of intervals); and condoms were not used in 76% of intervals. In approximately half of the intervals women had vaginal intercourse less than twice per week; women received oral sex in approximately half of intervals, and had anal sex in 5% of intervals. None of the sexual behaviors was statistically significantly associated with partner’s race. Compared to women with only white sex partners, women with African-American sex partners smoked less, and had they had higher body mass index.

Table 1.

Categorical factors associated with having an African-American male sex partner among white women.

| Characteristic | Number (%)* of intervals with the characteristic (906 intervals in total) | % of intervals in which an African-American partner was reported** | p-value† |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of sex partners in past 3 mos | 0.24 | ||

| 1 | 865 (95%) | 14.2% | |

| >1 | 41 (5%) | 24.4% | |

| Vaginal sex acts/wk in past 3 mos | 0.72 | ||

| >0 – <1 | 247 (27%) | 12.2% | |

| 1 – <2 | 183 (20%) | 9.8% | |

| 2 – <3 | 166 (18%) | 16.2% | |

| 3 – <4 | 157 (17%) | 15.3% | |

| 4 – <6 | 88 (10%) | 22.7% | |

| ≥6 | 63 (7%) | 20.6% | |

| Receptive oral sex/wk in past 3 mos | 0.25 | ||

| 0 | 437 (48%) | 16.2% | |

| >0 – <1 | 223 (25%) | 16.1% | |

| 1 – <2 | 92 (10%) | 8.7% | |

| ≥2 | 150 (17%) | 10.0% | |

| Anal sex acts/wk in past 3 mos | 0.99 | ||

| 0 | 855 (95%) | 14.6% | |

| >0 | 47 (5%) | 12.0% | |

| New sex partner in past 3 mos | 0.65 | ||

| No | 837 (92%) | 14.1% | |

| Yes | 68 (8%) | 22.1% | |

| Condom use over past 30 days | 0.46 | ||

| Always | 113 (12%) | 22.1% | |

| Sometimes | 104 (11%) | 8.6% | |

| Never | 689 (76%) | 14.4% | |

| Hormonal contraception | 0.52 | ||

| No | 480 (53%) | 16.0% | |

| Yes | 425 (47%) | 13.8% | |

| Douching | 0.91 | ||

| None | 618 (68%) | 14.2% | |

| Less than weekly | 228 (18%) | 18.0% | |

| Weekly or more often | 59 (7%) | 6.8% | |

| Marital status | 0.14 | ||

| Never married | 315 (35%) | 18.4% | |

| Currently married | 403 (44%) | 11.7% | |

| Other | 188 (21%) | 14.9% | |

| Cigarette smoking in past 3 months | 0.06 | ||

| None | 485 (54%) | 18.1% | |

| Any | 414 (46%) | 10.4% | |

| Alcohol use in past 3 mos | 0.93 | ||

| Never | 409 (45%) | 17.4% | |

| Less than weekly | 301 (33%) | 13.3% | |

| Weekly or more often | 196 (22%) | 11.2% | |

| Completed years of education | 0.32 | ||

| <12 | 326 (36%) | 16.0% | |

| 12 | 268 (30%) | 17.9% | |

| >12 | 305 (34%) | 10.8% |

Percents may not sum to 100 due to rounding

African-American partners were reported in 133 of 906 intervals

p-value from score statistic of a logistic regression, under generalized estimating equations, with any/no African-American male partner as the dependent variable and stated characteristic as the independent variable

Table 2.

Continuous variables associated with having an African-American male sex partner among white women

| African-American Sex Partner |

p-value† | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Yes | No | |

| Mean (SD) age, years | 26.0 (6.2) | 27.0 (7.3) | 0.15 |

| Mean (SD) BMI, kg/m2 | 30.7 (8.3) | 27.7 (8.3) | 0.02 |

| Median (75th % percentile) cigarettes/day†† | 0 (10) | 0 (15) | 0.02 |

p-value from score statistic of a logistic regression, under generalized estimating equations, with any/no African-American male partner as the dependent variable and stated characteristic as the independent variable

Among all women, including non-smokers

Table 3 shows that BV appeared in 24.8% of the intervals in which an African-American male sex partner was reported, versus 10.7% of the intervals in which only white partners were reported (risk ratio 2.3, 95% confidence interval 1.6 – 3.4). BV occurred in 8 of 158 (5.1%) intervals in which no sexual activity was reported (data not shown in Table 3). Adjustment for the factors listed in Table 1 and Table 2 changed the risk ratio for an African-American partner only minimally, to 2.2 (95% CI 1.5 – 3.4). As shown in Table 3 and Table 4, weekly or greater alcohol drinking and number of cigarettes smoked per day were associated with increased BV occurrence; and BV was less likely to appear among currently married women. Women who reported receptive oral sex from 1 to <2 times/week were less likely to have BV occur, although there appeared to be no trend between oral sex frequency and BV. None of the other factors in Table 3 and Table 4 was statistically significantly associated with the occurrence of BV.

Table 3.

Association between characteristics of women and the acquisition of Bacterial Vaginosis over 3-month follow-up intervals

| Characteristic | Probability of Acquiring BV During 3-Month Interval | Risk Ratio (95% CI) | Adjusted* Risk Ratio (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Race of male sex partner | |||

| All partners white | 10.7% | 1 | 1 |

| ≥ 1 African-American partner | 24.8% | 2.3 (1.6 – 3.4) | 2.2 (1.5 – 3.4) |

| Number of sex partners in past 3 mos | |||

| 1 | 12.5% | 1 | 1 |

| >1 | 19.5% | 1.5 (0.8 – 2.7) | 1.8 (0.9 – 3.8) |

| Vaginal sex/wk in past 3 mos | |||

| >0 – <1 | 12.2% | 1 | 1 |

| 1 – <2 | 8.7% | 0.7 (0.4 – 1.2) | 0.6 (0.4 – 1.1) |

| 2 – <3 | 15.7% | 1.4 (0.9 – 2.2) | 1.3 (0.8 – 2.1) |

| 3 – <4 | 12.7% | 1.1 (0.7 – 1.8) | 1.1 (0.6 – 1.8) |

| 4 – <6 | 13.6% | 1.1 (0.6 – 2.0) | 1.0 (0.6 – 1.9) |

| ≥ 6 | 19.0% | 1.6 (0.9 – 2.9) | 1.1 (0.6 – 1.9) |

| Receptive oral sex/wk in past 3 mos | |||

| 0 | 14.0% | 1 | 1 |

| >0 – <1 | 12.1% | 0.9 (0.6 – 1.4) | 0.9 (0.6 – 1.4) |

| 1 – <2 | 8.7% | 0.7 (0.3 – 1.3) | 0.5 (0.2 – 1.0) |

| ≥ 2 | 13.3% | 1.0 (0.6 – 1.5) | 0.8 (0.5 – 1.4) |

| Anal sex acts/wk in past 3 mos | |||

| 0 | 12.5% | 1 | 1 |

| >0 | 19.1% | 1.6 (0.9 – 2.8) | 1.7 (1.0 – 3.1) |

| New sex partner in past 3 mos | |||

| No | 12.9% | 1 | 1 |

| Yes | 11.8% | 0.9 (0.5 – 1.7) | 0.7 (0.3 – 1.5) |

| Condom use over past 30 days | |||

| Always | 9.7% | 1 | 1 |

| Sometimes | 14.4% | 1.5 (0.8 – 2.9) | 2.0 (1.0 – 4.0) |

| Never | 13.1% | 1.4 (0.7 – 2.6) | 1.7 (0.9 – 3.3) |

| Hormonal contraception | |||

| No | 11.9% | 1 | 1 |

| Yes | 13.9% | 1.2 (0.9 – 1.7) | 1.1 (0.8 – 1.6) |

| Douching | |||

| None | 11.8% | 1 | 1 |

| Less than weekly | 14.0% | 1.2 (0.8 – 1.7) | 1.0 (0.7 – 1.5) |

| Weekly or more often | 18.6% | 1.5 (0.8 – 2.7) | 1.5 (0.8 – 2.7) |

| Marital status | |||

| Never married | 18.7% | 1 | 1 |

| Currently married | 8.4% | 0.5 (0.3 – 0.7) | 0.6 (0.4 – 0.8) |

| Other | 12.2% | 0.6 (0.4 – 1.0) | 0.7 (0.4 – 1.2) |

| Cigarettes in past 3 mos | |||

| None | 9.7% | 1 | * |

| Any | 16.7% | 1.7 (1.2 – 2.4) | |

| Alcohol in past 3 mos | |||

| Never | 11.7% | 1 | 1 |

| Less than weekly | 12.0% | 1.0 (0.7 – 1.5) | 1.2 (0.8 – 1.8) |

| Weekly or more often | 16.3% | 1.4 (0.9 – 2.1) | 1.8 (1.2 – 2.8) |

| Completed years of education | |||

| <12 | 18.4% | 1 | 1 |

| 12 | 12.7% | 0.7 (0.5 – 1.0) | 0.9 (0..6 – 1.4) |

| >12 | 6.9% | 0.4 (0.2 – 0.6) | 0.5 (0.3 – 0.9) |

Adjusted for the other factors listed in the Table, plus age, and BMI. Number of cigarettes per day used in lieu of smoking as a binary variable.

Table 4.

Association between continuous characteristics of women and the acquisition of Bacterial Vaginosis over 3-month follow-up intervals

| Acquired BV |

Risk Ratio | Adjusted* Risk Ratio | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Yes | No | (95% CI) | (95% CI) |

| Mean (SD) age, years | 25.1 (7.1) | 27.1 (7.2) | 0.96/year (.93 – .99) | 0.98/year (.94 – 1.01) |

| Mean (SD) cigarettes/day | 9.2 (10.2) | 6.6 (9.0) | 1.02/cig (1.01 – 1.04) | 1.02/cig (1.00 – 1.04) |

| Mean (SD) BMI (kg/m2) | 28.5 (8.0) | 28.1 (8.4) | 1.00/kg/m2 (0.98 – 1.02) | 1.01/kg/m2 (0.99 – 1.03) |

Adjusted for the other factors listed in the Table, plus all factors in Table 3..

Next we evaluated interactions, that is whether the association between the sex partner’s race and appearance of BV differed among women with versus without any of the factors listed in Table 1 and Table 2. To do this, we added to the fully adjusted model, one at a time, an interaction term between partner’s race and each of the factors. When categorical factors were inherently ordered (such as always, sometimes and never use of condoms), we evaluated them both as simple categories and as a single continuous variable coded as 0, 1, 2, etc. The only interactions that had a p-value of <0.1 were partner’s race with frequency of condom use, and partner’s race with the woman’s education (both as continuous variables). The adjusted risk ratios for appearance of BV in association with having an African American sex partner were 0.7 (0.3 – 2.0) in intervals when women always used condoms, 2.4 (1.0 – 6.2) in intervals when they sometimes used condoms, and 2.7 (1.7 – 4.2) in intervals when they never used condoms. The p-value for the trend of increasing risk ratio to acquire BV with decreasing condom use was 0.04. Among women who had not graduated from high school, the risk ratio for the appearance of BV in intervals with an African-American sex partner was 1.5 (0.8 – 2.7); among women who were high school graduates the risk ratio was 2.6 (1.3 – 5.2); and among women who had greater than a high school education the risk ratio was 4.0 (1.8 – 8.7). The p-value the trend of increasing risk ratio to acquire BV with increasing education was 0.08.

We defined absence of BV as a Nugent score of 0 – 6. When we re-defined it as a score of 0 – 3 and excluded all intervals in which the score at the beginning or ending visit was 4 – 6, the unadjusted risk ratio for change in score from 0 – 3 to 7 – 10 in the presence of an African-American male partner was 2.3 (95% confidence interval 1.3 – 4.2, p=0.03) compared to intervals where all male partners were white, not substantially different from the risk ratio when absent BV was defined as 0 – 6. The rarity of African-American women being sexually active only with white men precluded analysis of partner’s race among these women. BV appeared in 0 of the 14 intervals where all sexual activity was with white men, versus 808 of 3038 (26.6%) intervals where there was at least 1 African-American male partner.

DISCUSSION

Among white women, we found that those who had an African-American male sex partner were approximately twice as likely to develop BV as those who reported only white male sex partners. The probability of BV appearing was similar in African-American (26.6%) and white (24.8%) women in the presence of an African-American male sex partner. Consistent condom use appeared to blunt the association between African-American male sex partners and BV acquisition among white women. These results suggest that BV has a sexual network component.

We are aware of only one previous study addressing the association of the both the woman’s and her male partner’s race and BV. In that cross-sectional study of women in the first trimester, Simhan et al.12 found that among white women, BV was approximately twice as prevalent when the father of the pregnancy was African-American than when he was white, but the father’s race was not strongly associated with BV among African-American women. Our longitudinal results are in agreement with Simhan’s regarding white women although we could not study this association in African-American women.

Whether BV is a sexually transmitted infection is controversial. Supporting non-sexual transmission are the observations that a single pathogen has not been identified as causing BV;6 that BV is regularly observed in self-reported virginal women,10,18,19 that personal hygienic behaviors such as douching are associated with an increased risk of BV8 and that co-treatment of male partners did not impact recurrence of BV.20 Supporting sexual transmission is the frequent co-occurrence of BV and infections known to be sexually transmitted;21 the increased prevalence of BV among women with more sex partners;22 increased BV incidence in the presence of a new sex partner;23 increased number of recent sex partners among male partners of women who developed BV;24 the high concordance of BV in lesbian sex partners;25 and results of a randomized trial indicating that male partner circumcision reduces the risk of BV.26 The association between BV and condom use has been variable. In a previous report from the Flora study, condom use was not associated with reduction in BV.27 However, other studies found recurrent BV was less common in women who abstained from sex or consistently used condoms;28 that BV treatment failure was more common when there was unprotected sex;29 that isolation of Gardnerella vaginalis from the urethra was reduced among men who consistently used condoms;30 and that BV occurrence was less during times when a woman consistently used condoms compared to times when that same woman did not use them consistently.31

Our finding that a characteristic of the male partner, his race, is associated with occurrence of BV might support sexual transmission, and the finding that consistency of condom use minimized this association further supports sexual transmission either of an infectious agent or other exposure in semen. Although BV is more prevalent among African-American women than among women of other racial groups,10 race is a social, rather than biological construct.32 Nevertheless, in nationally representative surveys only small minorities of both African-American and white individuals reported sexual relationships with individuals of the other race.33 Modeling of STD transmission in nationally representative data has shown that among individuals with one partner, the chance of the partner being in the “STD transmission core” is greater for African-Americans than for non-African-Americans.34 In combination with the observed degree of “sexual segregation” this results in higher prevalence of bacterial STDs in the African-American community, even after controlling for individual-level behaviors.34 We observed that the increased occurrence of BV associated with an African-American sex partner was greatest among women who had more than a high school education. There may be non-sexual factors (such as poor nutrition,35 douching8 or stress36) associated with acquisition of BV, and these factors are more prevalent among less educated women. Decreased occurrence of these non-sexual risk factors among more educated women would increase the apparent relative risk of sexual risk factors among these women by removing non-sexual causes of BV.

Strengths of the study include the prospective design, which enabled us to ascertain the appearance of BV, and the collection of detailed data on sexual habits. However, there are limitations. While we collected relatively extensive data about study women, and controlling for these potentially confounding factors did not substantially change our results, there may be unmeasured behaviors or characteristics that are adopted by white women who have African-American sex partners, that are otherwise more common among African-American women and that are the true cause of BV. In particular, our measure of socioeconomic status was limited to years of education. White women who have African-American sex partners may differ on other, more subtle socioeconomic characteristics than white women who have only white sex partners. We did not collect detailed data on male sexual partners, including socioeconomic factors like education or occupation, nor did we collect data on partners’ sexual histories. Adjustment for this information, had it been available, might have reduced the risk ratio.

Partners’ race was reported by the woman; while women were unaware of their BV status at the time of interview and reporting error is unlikely to differ by BV status, erroneous reporting is possible. Such non-differential misreporting would on average result in a lower risk ratio than we might otherwise have observed. We asked about condom use over the past 30 days, rather than during the entire 3-month interval. We ascertained BV only at the beginning and end of each 3-month interval. Women who were BV-negative at the beginning and end of the interval might have had BV at some point between those dates; similarly we do not know whether, within any given interval, intercourse preceded the appearance of BV.

An additional limitation arises from the chronic nature of BV. Regardless of its mode of acquisition, once established, BV often recurs in spite of treatment,36 and can have a relapsing and remitting course in untreated women.37 We followed women for one year. Women who were BV-negative at the beginning of the study might have had BV before they enrolled, blurring the distinction between “incidence” and “relapse.” Similarly, the characteristics of a woman’s sex partners over the course of the study might not be the same as those of any partners she may have had before she enrolled. To address this limitation it would be necessary to begin following women before they become sexually active.

In summary, our findings that the race of a woman’s male sex partner is associated with the appearance of BV, and that consistent use of condoms appears to mitigate this association provides indirect evidence for a sexual network and transmissible nature of BV.

Acknowledgments

Supported by contract NO-1-HD-8-3293 and by Intramural funds (Z01 HD002535-10) from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development

REFERENCES

- 1.Hill GB. The microbiology of bacterial vaginosis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1993;169:450–454. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(93)90339-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hillier SL, Nugent RP, Eschenbach DA, et al. Association between bacterial vaginosis and preterm delivery of a low-birth-weight infant. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:1737–1742. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199512283332604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Soper DE, Bump RC, Hurt WG. Bacterial vaginosis and trichomoniasis vaginitis are risk factors for cuff cellulitis after abdominal hysterectomy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1990;163:1016–1021. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(90)91115-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Taha TE, Hoover DR, Dallabetta GA, et al. Bacterial vaginosis and disturbances of vaginal flora: association with increased acquisition of HIV. AIDS. 1998;12:1699–1706. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199813000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kaul R, Nagelkerke NJ, Kimani J, et al. Prevalent herpes simplex virus type 2 infection is associated with altered vaginal flora and an increased susceptibility to multiple sexually transmitted infections. J Infect Dis. 2007;196:1692–1697. doi: 10.1086/522006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Josey WE, Schwebke JR. The polymicrobial hypothesis of bacterial vaginosis causation: a reassessment. Int J STD AIDS. 2008;19:152–154. doi: 10.1258/ijsa.2007.007260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Martino JL, Vermund SH. Vaginal douching: evidence for risk or benefit for women’s health. Epidemiol Rev. 2002;24:109–124. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxf004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brotman RM, Klebanoff MA, Nansel TR, et al. A longitudinal study of vaginal douching and bacterial vaginosis--a marginal structural modeling analysis. Am J Epidemiol. 2008;168:188–196. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwn103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goldenberg RL, Klebanoff MA, Nugent R, et al. Bacterial colonization of the vagina during pregnancy in four ethnic groups. Vaginal Infections and Prematurity Study Group. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1996;174:1618–1621. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(96)70617-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Allsworth JE, Peipert JF. Prevalence of bacterial vaginosis: 2001–2004 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey data. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;109:114–120. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000247627.84791.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ness RB, Hillier S, Richter HE, et al. Can known risk factors explain racial differences in the occurrence of bacterial vaginosis? J Natl Med Assoc. 2003;95:201–212. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Simhan HN, Bodnar LM, Krohn MA. Paternal race and bacterial vaginosis during the first trimester of pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;198:196.e1–196.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2007.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rothenberg R. Maintenance of endemicity in urban environments: a hypothesis linking risk, network structure and geography. Sex Transm Infect. 2007;83:10–15. doi: 10.1136/sti.2006.017269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Klebanoff MA, Schwebke JR, Zhang J, et al. Vulvovaginal symptoms in women with bacterial vaginosis. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;104:267–272. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000134783.98382.b0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nugent RP, Krohn MA, Hillier SL. Reliability of diagnosing bacterial vaginosis is improved by a standardized method of gram stain interpretation. J Clin Microbiol. 1991;29:297–301. doi: 10.1128/jcm.29.2.297-301.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Diggle P, Heagerty P, Liang K-Y, Zeger S. Analysis of Longitudinal Data. 2nd Edition. New York: Oxford University Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zou G. A modified Poisson regression approach to prospective studies with binary data. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;159:702–706. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwh090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bump RC, Buesching WJ., 3rd Bacterial vaginosis in virginal and sexually active adolescent females: evidence against exclusive sexual transmission. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1988;158:935–939. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(88)90097-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yen S, Shafer MA, Moncada J, et al. Bacterial vaginosis in sexually experienced and non-sexually experienced young women entering the military. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;102:927–933. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(03)00858-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vejtorp M, Bollerup AC, Vejtorp L, et al. Bacterial vaginosis: a double-blind randomized trial of the effect of treatment of the sexual partner. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1988;95:920–926. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1988.tb06581.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Joesoef MR, Wiknjosastro G, Norojono W, et al. Coinfection with chlamydia and gonorrhoea among pregnant women and bacterial vaginosis. Int J STD AIDS. 1996;7:61–64. doi: 10.1258/0956462961917096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Smart S, Singal A, Mindel A. Social and sexual risk factors for bacterial vaginosis. Sex Transm Infect. 2004;80:58–62. doi: 10.1136/sti.2003.004978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hawes SE, Hillier SL, Benedetti J, et al. Hydrogen peroxide-producing lactobacilli and acquisition of vaginal infections. J Infec Dis. 1996;174:1058–1063. doi: 10.1093/infdis/174.5.1058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schwebke JR, Desmond RA. Risk factors for bacterial vaginosis in women at high risk for STDs. Sex Transm Dis. 2005;32:654–658. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000175396.10304.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Marrazzo JM, Koutsky LA, Eschenbach DA, et al. Characterization of vaginal flora and bacterial vaginosis in women who have sex with women. J Infec Dis. 2002;185:1307–1313. doi: 10.1086/339884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gray RH, Kigozi G, Serwadda D, et al. The effects of male circumcision on female partners' genital tract symptoms and vaginal infections in a randomized trial in Rakai, Uganda. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009;200(42):e1–e7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2008.07.069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Riggs M, Klebanoff MA, Nansel TR, et al. Longitudinal association between hormonal contraceptives and bacterial vaginosis in women of reproductive age. Sex Transm Dis. 2007;34:954–959. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sanchez S, Garcia PJ, Thomas KK, et al. Intravaginal metronidazole gel versus metronidazole plus nystatin ovules for bacterial vaginosis: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;191:1898–1906. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2004.06.089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schwebke JR, Desmond RA. A randomized trial of metronidazole duration plus or minus azithromycin for treatment of symptomatic bacterial vaginosis. Clin Inf Dis. 2007;44:213–219. doi: 10.1086/509577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schwebke JR, Rivers C, Lee J. Prevalence of Gardnerella vaginalis in male sexual partners of women with and without bacterial vaginosis. Sex Transm Dis. 2009;36:92–94. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3181886727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hutchinson KB, Kip KE, Ness RB. Condom use and its association with bacterial vaginosis and bacterial vaginosis-associated vaginal microflora. Epidemiology. 2007;18:702–708. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e3181567eaa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kaufman JS, Cooper RS. Race in epidemiology: new tools, old problems. Ann Epidemiol. 2008;19:119–123. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2007.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Joyner K, Kao G. Interracial relationships and the transition to adulthood. Am Sociol Rev. 2005;70:563–581. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Laumann EO, Youm Y. Racial/ethnic group differences in the prevalence of sexually transmitted diseases in the United States: a network explanation. Sex Transm Dis. 1999;26:250–261. doi: 10.1097/00007435-199905000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Neggers YH, Nansel TR, Andrews WW, et al. The relationship between bacterial vaginosis and dietary intake. J Nutr. 2007;137:2128–2133. doi: 10.1093/jn/137.9.2128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nansel TR, Riggs M, Yu KF, et al. Psychosocial stress predicts incidence of bacterial vaginosis in a longitudinal cohort. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;194:381–386. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2005.07.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; 36 Bradshaw CS, Morton AN, Hocking J, et al. High recurrence rates of bacterial vaginosis over the course of 12 months after oral metronidazole therapy and factors associated with recurrence. J Infect Dis. 2006;193:1478–1486. doi: 10.1086/503780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hay PE, Ugwumadu A, Chowns J. Sex, thrush and bacterial vaginosis. Int J STD AIDS. 1997;8:603–608. doi: 10.1258/0956462971918850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]