Abstract

Numerous biochemical as well as electrophysiological techniques require tissue that must be retrieved very quickly following death in order to preserve the physiological integrity of the neuronal environment. Therefore, the ability to accurately predict the precise locations of brain regions of interest (ROI) and to retrieve those areas as quickly as possible following the brain harvest is critical for subsequent analyses. One way to achieve this objective is the utilization of high resolution MRI scans to guide the subsequent dissections. In the present study, individual MRI scans of the brains of rhesus and cynomolgus macaques that had chronically self-administered ethanol were employed in order to determine which blocks of dissected tissue contained specific ROIs. MRI-guided brain dissection of discrete brain regions was completely accurate in 100% of the cases. In comparison, approximately 60–70% accuracy was achieved in dissections that relied on external landmarks alone without the aid of MRI. These results clearly demonstrate that the accuracy of targeting specific brain areas can be improved with high-resolution MR imaging.

Keywords: primate, brain, dissection, magnetic resonance imaging, region of interest, ethanol

Introduction

Addressing the issue of human disease states is best done in humans but it is often difficult to disentangle a particular pathology from confounding behavioral or environmental variables. For this reason, nonhuman primates are increasingly being used to model various human disease conditions in an attempt to better understand the pathophysiological correlates and sequelae of particular disease processes while limiting the influence of variables that often confound human postmortem and clinical studies (e.g. agonal state of death, post-mortem interval, and disease co-morbidity). Nonhuman primates, in particular Old World monkeys such as macaques, are phylogenetically close to humans and are therefore an excellent model for translational research. Further, they share extensive social, cognitive, biochemical and neuroanatomical similarities with humans that are not afforded by other species. Macaques in particular have been used extensively to model the neurobiological effects of substance abuse [1–5] and as models of neurodegenerative and psychiatric diseases [6]. Animal models of drug self-administration have proven to be valid predictors of human drug abuse [7–10] and provide an alternative to address or overcome limitations inherent in human clinical research. Indeed, our research groups have utilized a self-administration paradigm with cynomolgus and rhesus macaques to study the long term effects of chronic ethanol exposure that closely parallels the patterns and levels of ethanol intake seen in human alcoholics [11, 12]. This model is highly predictive of daily ethanol intake and identifies early alcohol drinking phenotypes that evolve into chronic heavy drinkers [12]. This represents an example of how behavioral, pharmacological, and neurobiological variables that mediate disease processes can be identified in an animal model expeditiously.

Macaques provide excellent experimental resources to model human neuropathologies. However, there can be extensive intersubject variability in brain size and shape, as well as, specific locations of subcortical structures between individual animals or between species [6, 13]. Stereotaxic procedures are typically performed using atlas-based coordinates which can often be limited in accuracy due to inconsistencies in stereotaxic precision between researchers. This is especially true in relation to the auditory meatus from which stereotaxic coordinates typically derive [14]. Currently available atlases of the macaque brain [15, 16] are generally based on a single animal and therefore cannot take into account intersubject or interspecies variability. This variability contributes to one of the limitations that occur using external landmarks alone to guide macaque brain dissections. Given that there can be considerable variation from brain to brain and between species, using external landmarks alone to block a brain can lead to a particular brain region of interest being sectioned into different blocks for different individuals. These obstacles can be overcome by using individual structural MRI images to assist in the identification and location of specific brain regions. Recent improvements in resolution and signal-to-noise due to higher field strengths and improvements in coil design have helped drive the increased use of MRI to guide invasive neurosurgical procedures in the brains of nonhuman primates. Anatomic MRI images have been used to direct a host of neurosurgical procedures ranging from defining stereotaxic coordinates [17], microelectrode implantation [18, 19], cell transplantation [20, 21], neurosurgery [22, 23], and microdialysis procedures [24] and focused ultrasound surgery [25].

This paper describes a case study in which structural MRI scans were implemented to assist in the dissection of discrete brain regions from rhesus (Macaca mulatta) and cynomolgus (Macaca fascicularis) macaques that chronically self-administered ethanol in two separate studies. These studies were terminal in nature and the necropsies of these experimental animals were designed to harvest specific brain areas for subsequent in vitro recording of neuronal activity and neurotransmitter uptake. Prior to the necropsies of these animals, numerous requests were received from different investigators for specific brain regions including the amygdala, caudate nucleus and lateral geniculate nucleus as previously described [26–31]. In addition to those brain regions which are readily visible macroscopically, other less obvious areas such as the Edinger-Westphal nucleus were also requested. Our initial attempts to dissect specific brain regions using external landmarks alone to guide the dissections sometimes resulted in loss of some tissue due to individual variability between animals in the location of the brain region. In order to satisfy the tissue requests with a high degree of confidence, anatomical MRI scans previously acquired on these animals were used to assist in identifying the precise location of the targeted brain regions prior to harvesting the brain.

Description of Methods

This paper summarizes results from two different studies from our groups in which structural MRI images were used to help guide the dissection of the rhesus and cynomolgus macaque brain. It should be noted that the MRIs were acquired as part of separately funded studies and were subsequently made available to help guide the necropsies of the animals. A total of 10 adult, male rhesus macaques and 16 adult female cynomolgus macaques underwent MRI guided brain dissection, either at Wake Forest University School of Medicine (WFUSM) or Oregon Health and Sciences University (OHSU) respectively. All of the animals were subjects in long-term ethanol self-administration studies. Individual T1-weighted (T1) structural images were acquired on each animal under isoflurane anesthesia at a resolution of 0.5 mm isotropic on a 3T GE scanner at WFUSM or on a 3T Siemans scanner at OHSU.

Image Acquisition

Structural images were acquired on the 3T GE scanner at WFUSM at a resolution of 0.5mm isotropic using a quadrature custom built Litz Cage RF coil (Doty Scientific). The animals’ heads were positioned in a foam head holder to minimize motion artifact during the scan session due to scanner vibrations. Fast gradient echo axial, sagittal, and coronal localizer images were acquired for graphically prescribing a T1-weighted (T1) structural scan. Axial high-resolution T1 weighted structural scans were acquired with an inversion prepared 3D spoiled gradient echo (3DSPGR) inversion recovery sequence [32] with the following parameters: inversion time (TI) 300 ms, echo time (TE) 2.9 ms, repetition time (TR) 13.6 ms; flip angle 15 degrees; receiver bandwidth 7.8 kHz; in-plane matrix size, 256 × 256; field of view, 12 cm; in-plane resolution, 0.47 mm; slice thickness, 1.0 mm; number of slices, 128. The 3D SPGR images were acquired four times yielding four sets of images. Acquiring four sets of 3D SPGR images has two advantages over signal averaging during data acquisition. First, the multiple shorter image acquisitions provides the anesthesiologist better access to monitor the health of the animals without interrupting data acquisition. Second, even in an anesthetized animal, small head movements occur over long scan periods due to gradient vibrations and body movements due to respiration, muscle relaxation, etc. The total acquisition time for the T1 weighted images was approximately 40 minutes.

Structural images were also acquired at OHSU on a 3T Siemens trio MRI scanner with an 8 channel extremity phased array coil (InVivo). Fast gradient echo axial, sagittal, and coronal localizer images were acquired for graphically prescribing a T1-weighted structural scan. Axial high-resolution T1 weighted structural scans were acquired with a 3D MP-RAGE inversion recovery sequence with the following parameters: TI 1100 ms, TE 4.38 ms, TR 2500 ms (according to Siemen’s convention, or TR 19.5 ms according to GE convention); flip angle 12 degrees; with isotropic image resolution of 0.5 mm-sided voxels. The MP-RAGE images were acquired 6 times yielding 6 sets of images. These were acquired separately, averaged following rigid body alignment, and AC-PC aligned. The total acquisition time for the T1 weighted images was approximately 48 minutes.

The above pulse sequence parameters were designed to yield structural images for volumetric analyses of various brain regions of interest that are known to be impacted in the brains of chronic alcoholics. The strategies described below to locate specific brain areas however, are also applicable in lower resolution images.

MRI-assisted Identification and Localization of Regions of Interest

Prior to each necropsy, the individual MRI for each animal was viewed offline in the axial, sagittal and coronal planes using standard 3D imaging software such as MRIcro (http://www.sph.sc.edu/comd/rorden/mricro.html) or Medical Image Processing, Analysis and Visualization (MIPAV) (http://mipav.cit.nih.gov/) in order to identify the precise location of specific ROIs. The specific location of these ROIs was identified using either of the following methods with equal success. In each instance, the rostral-most tips of the temporal poles served as an external landmark from which to begin the measuring process.

MRIcro

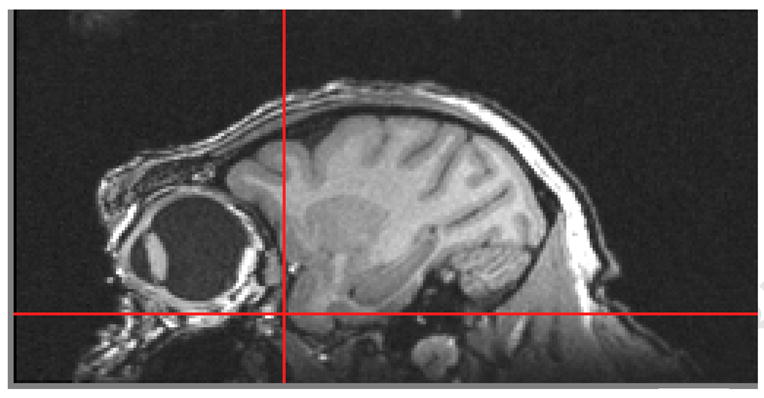

One of the features of MRIcro is the ability to view the brain in the axial, sagittal and coronal plane merely by selecting the plane of view that is desired. Opening the image multiple times allows the brain to be viewed in all three planes at the same time with the advantage that all of the images can be synchronized such that placement of the cursor in a specific location in the sagittal plane will also place that cursor in the exact location in the coronal or axial planes. Figure 1A represents the brain of a cynomolgus monkey in the sagittal plane with the cursor placed at the rostral-most tip of the temporal pole as indicated by the red cross-hairs. The red cross-hairs in Figure 1B and 1C reflect the same location in the coronal and axial planes, respectively. This slice is then identified in MRIcro on the toolbar that is used to scroll through the brain in any orientation. Using the rostral-most extension of the temporal pole as a starting point, any region of interest can be chosen and identified. One need merely place the cursor (and hence cross-hairs) on a specific location and then count the number of slices between that point and the location of the starting point (the rostral temporal pole). Depending on the resolution of the data acquisition, the number of slices is then multiplied by whatever factor is necessary to achieve the distance in mm. We multiplied by a factor of 2 since our resolution was 0.5 mm in plane and through plane.

Figure 1.

1A Sagittal plane of cynomolgus monkey brain demonstrating placement of cursor at the rostral border of the temporal pole.

1B Coronal plane of cynomolgus monkey brain demonstrating placement of cursor at the rostral border of the temporal pole.

1C Axial plane of cynomolgus monkey brain demonstrating placement of cursor at rostral border of temporal pole.

Medical Image Processing, Analysis and Visualization (MIPAV)

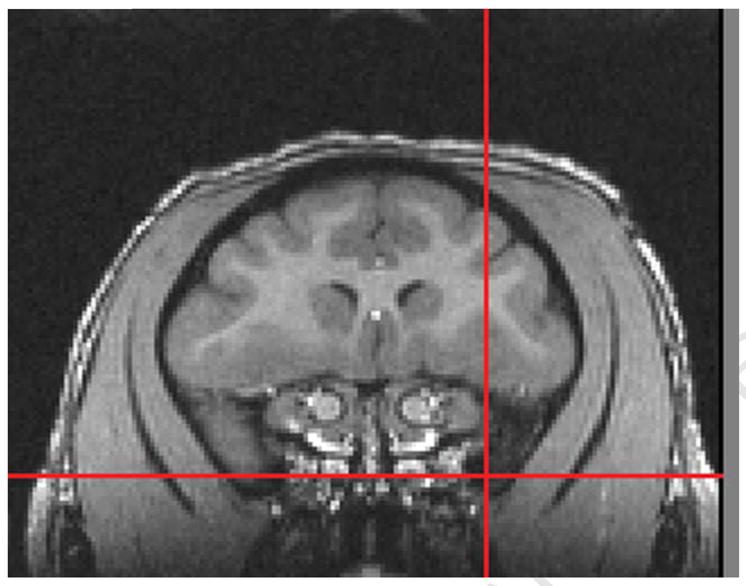

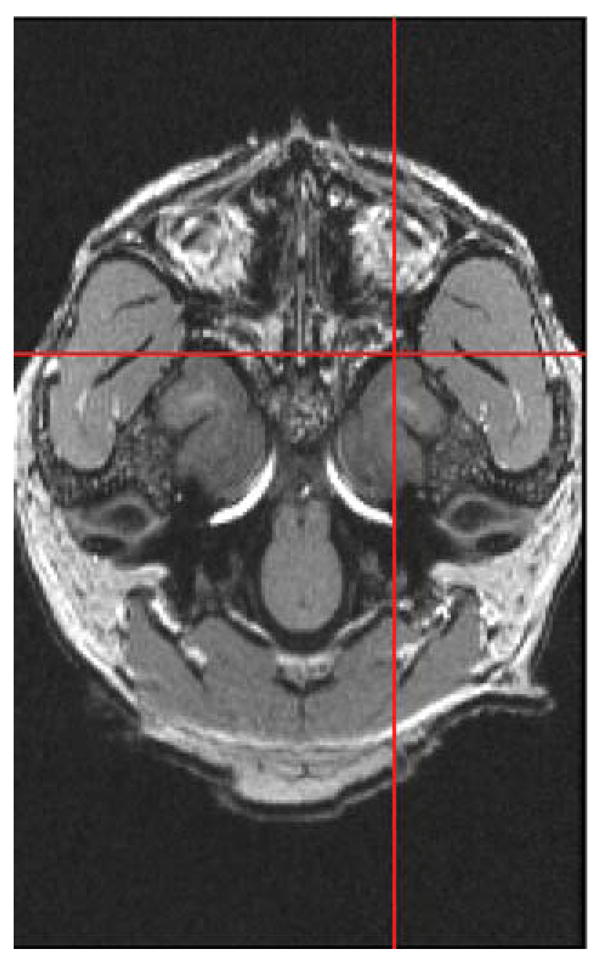

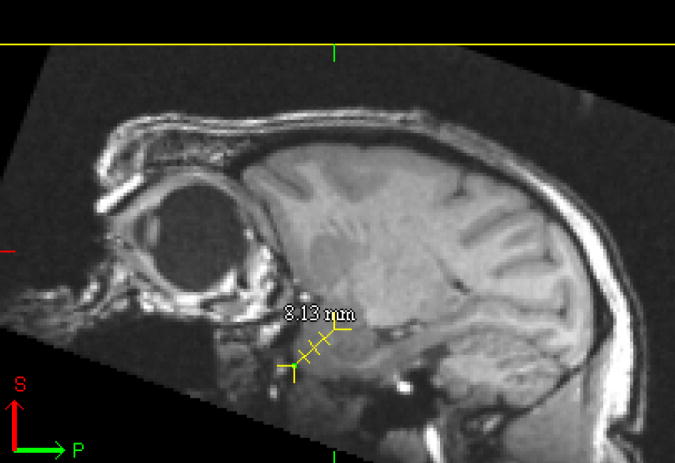

MIPAV allows similar viewing of a single brain in the sagittal, coronal and axial planes. This feature in the freeware image viewer allows triplanar viewing. Additionally, all three planes are synchronized such that simply dragging the cross-hairs in a particular plane will place the intersection of the cross-hairs at that identical location in the other 2 planes. MIPAV has an additional tool on the toolbar that when selected, highlights as the Draw line VOI which is particularly useful for measuring the distance in mm from a particular starting point. Again, using the rostral extent of the temporal poles as a starting point, the cursor was dragged to the region of interest resulting in a straight line with the appropriate measurement in mm distance. Figure 2A illustrates this tool being applied in the sagittal plane in the brain of the same cynomolgus monkey represented in Figure 1. This measuring tool was placed at the rostral tip of the temporal pole and dragged to approximately the middle of the amygdala (Fig 2A). Figure 2B illustrates the level of the amygdala in the coronal plane that results from placing the tool in this position.

Figure 2.

2A MIPAV representation of sagittal plane of same cynomolgus monkey as shown in Figure 1. Yellow dashed arrow represents the cursor placed at the rostral extent of the temporal pole.and pulled to the location of the region of interest; in this case the middle of the amygdala. The distance from the rostral extent of the temporal pole to the ROI in this case was approximately 8mm.

2B Coronal plane at the level of the mid-amydgala (box) approximately 8 mm caudal to the rostral extent of the temporal pole as measured in the sagittal plane shown in Fig 2A.

2C Box shows representative dissection in fresh brain in coronal plane 8 mm caudal to rostral temporal pole.

Brain Dissections

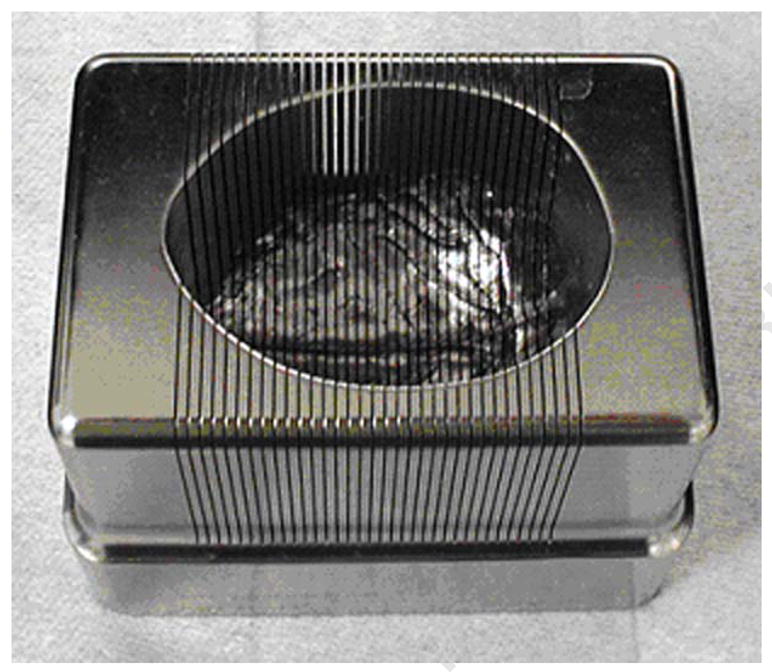

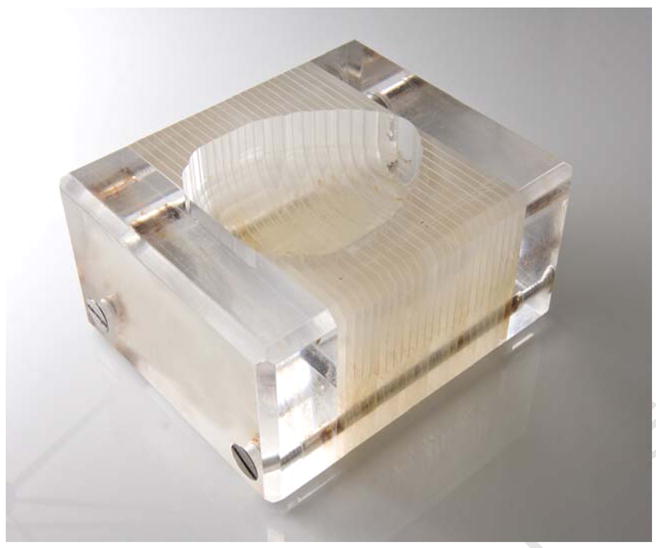

A craniotomy was conducted under conditions of anesthesia that were optimized to remove the brain for purposes of subsequent electrophysiological and voltammetry procedures. After the brain was harvested, it was placed dorsal side down into a brain matrix (shown in figures 3A and 3B). We use 2 matrices which were designed to hold and dissect the nonhuman primate brain in the coronal plane using brain knives that can be positioned a minimum of 2 mm apart. Using the rostral extent of the temporal poles as an external landmark, a brain knife was inserted into the appropriate slot to make the initial cut through the brain, in essence separating the frontal lobes from the rest of the brain. The knife slots in the brain matrix are placed 2mm (Fig 3A – Electron Microscopy Sciences) or 4mm apart (Fig 3B- manufactured locally) depending on the matrix that was used to slice the brain. Our strategy was to make 4 mm cuts throughout the rostral-caudal extent of the brain. Using this strategy, if a particular ROI could not be sectioned within a single 4 mm-thick block (i.e. if a particular ROI was 9 mm caudal to the rostral extent of the temporal pole), then the brain could be shifted in the brain matrix in order to make the next cut at the appropriate location. To guide these adjustments, each animal’s individual MRI was used to appropriately position the brain knives for blocking of the brain.

Figure 3.

3A Stainless steel brain matrix purchased from Electron Micropscopy Sciences with 2 mm distance between slots.

3B Acrylic brain mold (manufactured locally) with 4 mm distance between slots.

Results

The tissue harvest strategy relies on placing the brain in a brain matrix and cutting the brain into multiple 4 mm slices throughout the rostral-caudal extent of the brain. Given that there are often multiple requests for the same tissue regions, it is critical to have the ability to identify not just the location of specific brain regions, but in some instances, specific locations of subregions of the same ROI. In particular, several investigators were interested in obtaining tissue from the basolateral and lateral amygdala for genomic and proteomic assays in the cynomolgus monkeys. In this case, viewing each animal’s individual structural MRI allowed the brain knife to be positioned such that a cut could be made through the middle of the amygdaloid complex to provide access to the target areas. With this approach, it was determined that the area of the amygdala that contained the requested subnuclei was located approximately 8 mm caudal to the tips of the temporal poles (Figure 2A). Figure 2B illustrates the coronal view located approximately 8mm caudal to the temporal poles with the resultant dissection in the fresh brain illustrated in Figure 2C. This strategy resulted in two tissue blocks which contained the same brain regions - subnuclei on the caudal face of one block and on the rostral face of the other block as demonstrated by a dissection through another brain (Fig 4). As shown in Table 1, a large percentage of the brains required a rostral or caudal adjustment in order to expose the middle of the amygdala complex in the coronal plane for subsequent harvesting of the targeted subnuclei. Due to the fact that these subnuclei are approximately 4–6 mm in rostral/caudal length, the use of MRI-guided dissection provided the accuracy necessary to retrieve the amygdala regions that were requested with a much higher degree of precision than using external landmarks alone. Using this strategy, the targeted subregions of the amygdala were successfully recovered in each of the 16 cynomolgus monkeys.

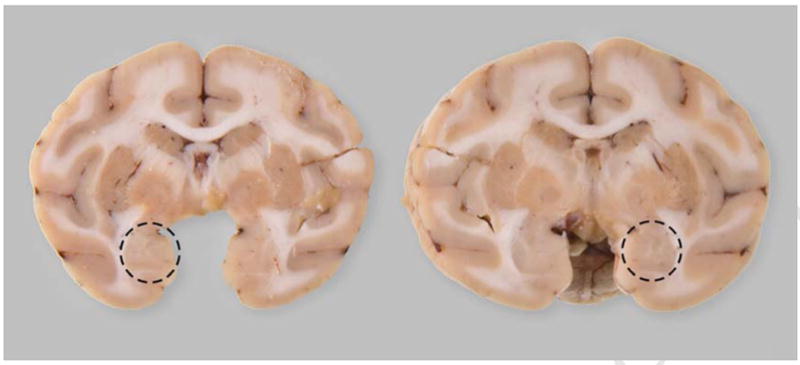

Figure 4.

Dissection at 8 mm caudal to the rostral-most extent of the temporal poles yields two blocks of tissue containing mirror faces (dashed circles) of the same subnuclei of the amygdala.

Table 1.

Example of variation in total distance as measured from the rostral extent of the temporal poles to the mid-amygdala/Edinger Westphal (EW) nucleus (column 2), mm. Column 3 contains the distance (mm) that the brain was shifted in the brain matrix in order to accurately dissect the region of interest. Animal identification number in column 1 indicates individual Cynomolgus (C) macaques

| Animal ID Number | Distance from Temporal Pole to Amygdala/EW nucleus (mm) | Distance Brain Shifted in Matrix Amygdala/EW nucleus (mm) |

|---|---|---|

| C25058 | 10/14 | 2/2 |

| C25050 | 11/18 | 3/2 |

| C25061 | 9/16 | 1/0 |

| C25064 | 10/20 | 2/0 |

| C25065 | 9/18 | 1/2 |

| C25069 | 9/17 | 1/1 |

| C25072 | 11/16 | 3/0 |

| C25073 | 9/19 | 1/3 |

| C25076 | 9/19 | 1/3 |

| C25077 | 10/16 | 2/0 |

| C25080 | 9/16 | 1/0 |

| C25081 | 9/17 | 1/1 |

| C25084 | 8/16 | 0/0 |

| C25085 | 10/17 | 2/1 |

| C25088 | 10/18 | 2/2 |

| C25089 | 11/18 | 3/2 |

The MRI-guided dissection strategy was particularly useful for collecting tissue blocks containing the hippocampus and the amygdala which were subsequently used for the electrophysiology studies previously cited. Based on each animal’s individual MRI, the brain knives were positioned with a high degree of precision at the rostral extent of the temporal poles, the junction of the caudal amygdala and rostral hippocampus (AH junction) and at the caudal end of the hippocampus. Using this approach, separate blocks containing the amygdala complex and hippocampus were retrieved with 100% efficiency. In the majority of subjects, the brain was moved a few mm in either the rostral or caudal direction in order to make the cut at the junction between the two structures (Table 2). In contrast, if the MRI data were unavailable, the accuracy of locating the amygdala/hippocampal junction would be nearly impossible, with errors of 3–6 mm in the majority of the cases based on the rostral-caudal length of these brain regions.

Table 2.

Total distance measured from the rostral extent of the temporal poles to the amygdala-hippocampus (AH) junction (column 2). Column 3 shows the distance that the brain had to be shifted in the brain matrix in order to dissect at the desired location. Animal identification number in column 1 signifies individual Rhesus macaques (Rh)

| Animal ID Number | Distance from Temporal Pole to AH junction(mm) | Distance Brain Shifted in Matrix (mm) |

|---|---|---|

| Rh1474 | 14 | 2 |

| Rh1475 | 12 | 0 |

| Rh1476 | 14 | 2 |

| Rh1477 | 12 | 0 |

| Rh1478 | 13 | 1 |

| Rh1479 | 15 | 3 |

| Rh1480 | 13 | 1 |

| Rh1481 | 14 | 2 |

| Rh1482 | 14 | 2 |

| Rh1483 | 15 | 3 |

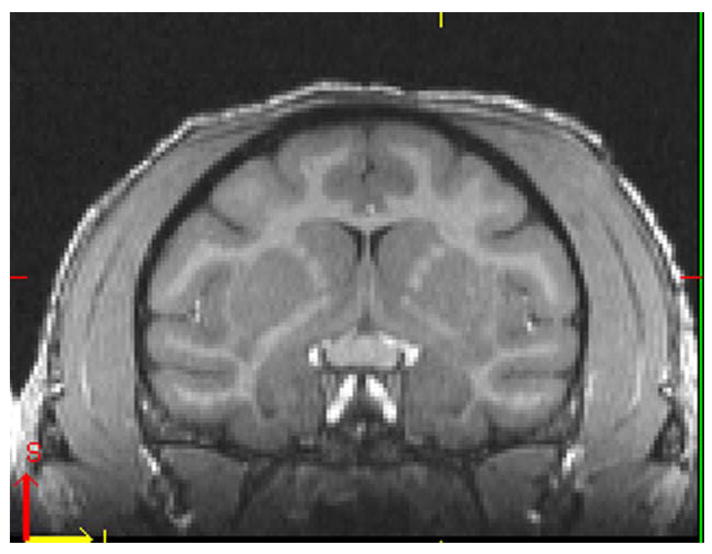

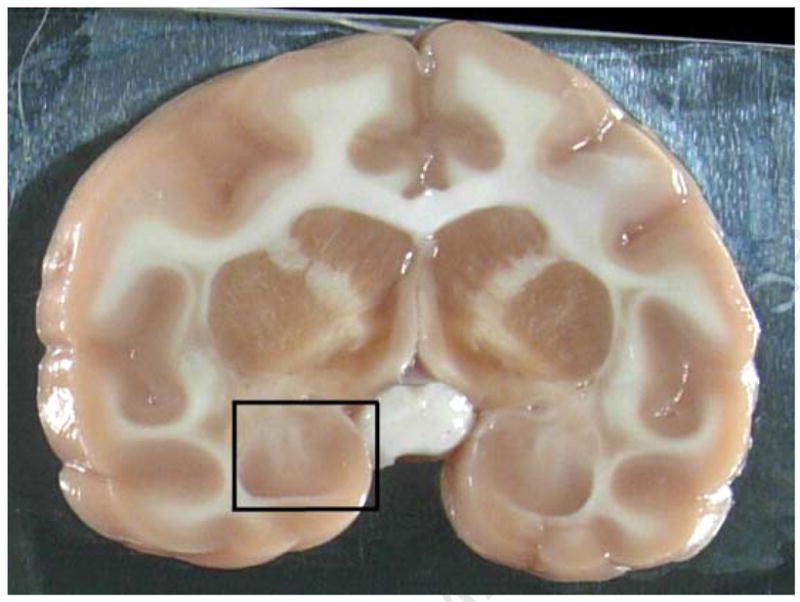

Another brain region of interest that was requested prior to the necropsies was the Edinger-Westphal (EW) nucleus which expresses dense levels of urocortin and is thought to have involvement in the consumption of ethanol [33]. The Edinger-Westphal nucleus is located in the mesencephalon at the level of the substantia nigra. It is part of the third nerve complex located dorsal to the substantia nigra, ventral to the thalamus and medial to the Red Nucleus as demonstrated in the MRI acquired in the coronal plane (Fig 5A) and in the corresponding 4 mm brain slice (Fig 5B). Use of MIPAV allowed us to determine that the distance from the rostral extent of the temporal poles to the level containing the EW nucleus was approximately 16 mm.

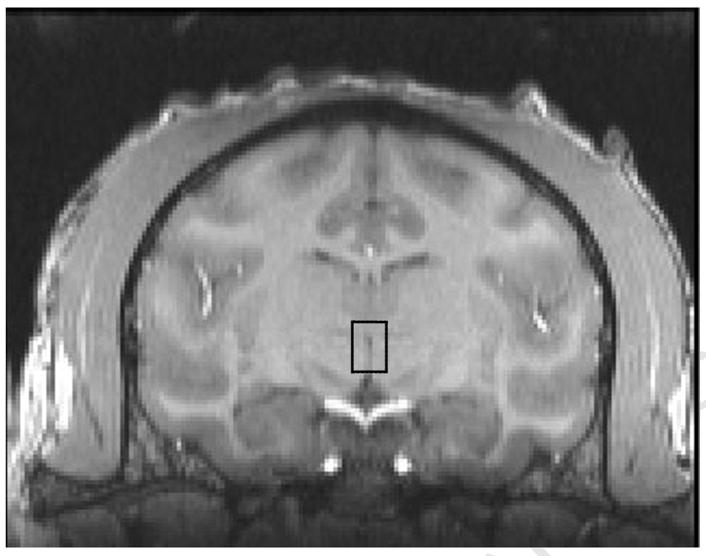

Figure 5.

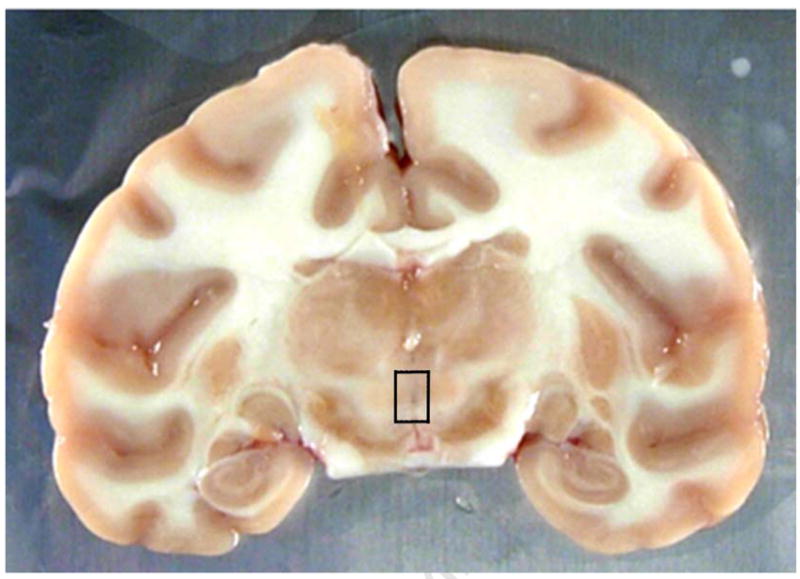

5A Coronal plane demonstrating the level at which the Edinger-Westphal nucleus is located – approximately 16 mm caudal to the rostral extent of the temporal poles. EW nucleus contained within area outlined by box.

5B Coronal plane demonstrating the actual brain slice containing the Edinger-Westphal nucleus as determined by this animal’s structural MRI image. EW nucleus contained within area outlined by box.

Although all 3 planes of view were used for confirmation of ROI location, the coronal and sagittal planes proved to be most useful for purposes of identifying specific ROIs and for making the appropriate cuts to obtain the desired tissues. This MRI-guided dissection strategy was recently utilized to block the brains of 16 female cynomolgus macaques that recently completed a long-term ethanol self-administration paradigm. From those brain blocks, such discrete brain regions as the hippocampus, nucleus accumbens core and shell, entorhinal cortex, lateral geniculate nucleus, central nucleus of the amygdala, and Edinger-Westphal nucleus were successfully retrieved from all 16 subjects.

Discussion

Two readily available freeware medical image viewing software packages, MRIcro and MIPAV, were utilized for purposes of identifying the precise location of particular brain regions for subsequent positioning of brain knives in order to segment the brain and retrieve these brain areas. Using the structural MRI images of each individual animal, we were able to collect specific brain regions during the necropsy procedure with 100% success by implementing the strategy of using MRIcro or MIPAV to identify the precise location of the particular ROI prior to the necropsy. Both software packages were equally efficient at identifying the location of the ROIs and both were fairly equally user friendly.

The results presented here clearly demonstrate that the use of individualized anatomical MRIs to assist dissection of the macaque brain can improve the accuracy of targeting and removing specific brain regions of interest to 100%, and is a clear improvement over the use of external landmarks alone. Our studies were designed primarily to harvest discrete brain regions for subsequent electrophysiology and voltammetry experiments to allow recordings to be made in slices of hippocampal, amygdala, striatal or thalamic tissue, as well as, to rapidly harvest tissue for subsequent freezing and storage for biochemical analysis. Because various biochemical and recording methods require living brain tissue, it was critical for us to be able to accurately identify the precise location of these ROIs and to be able to remove them in a prompt fashion. Our initial attempts to harvest tissue blocks containing hippocampus and amygdala relied on using external landmarks as reference points in concert with viewing the Paxinos atlas [15]. The resultant dissections however often resulted in some loss of either hippocampal or amygdalar tissue. For example, referencing Paxinos [15] or Saleem and Logothetis [16] results in prescribing a cut 13mm caudal to the rostral temporal pole. Referring to Table 1 shows that in 80% of the rhesus brains, this resulted in a cut through this region that was 1–3 mm away from the desired coronal plane. In our experience, prior to performing MRI-guided dissection, this sometimes resulted in a cut being made too rostral or too caudal due to the inherent variability between animals and species. In some cases, the hippocampal block contained some of the caudal amygdala or vice versa, which resulted in less than optimal tissue blocks for the subsequent recording assay in 40–60% of cases. In studies using nonhuman primates where the overall number of animals in each group is often limited, this error can be critical. The need for accurate localization of multiple ROIs is further amplified in cases in which several investigators request the same tissue regions from a single animal. As described here, MRI-guided dissection resulted in tissue blocks containing the overwhelming majority of the desired ROIs in each dissection, thus avoiding the problem of losing part of the desired region. This was recently evidenced by the successful harvest of 7 discrete cortical and subcortical brain regions from 16 cynomolgus macaques.

An illustrative example of the potential advantages gained by MRI-guided dissection if provided by the general rule of thumb that the rostral extent of the temporal poles is a landmark for the head of the caudate nucleus (see Paxinos plate 29 [15]). Due to individual variability between animals, it was our experience prior to incorporation of MRI data for surgical planning that blocking the brain at this location sometimes resulted in a dissection at a level that was more caudal than expected. Indeed, in 1 extreme case of an anomalous brain, blocking the brain at this location resulted in a cut at the level of the nucleus accumbens shell and core region, thus complicating the subsequent mounting and slicing of this brain region for voltammetry studies, and hence a loss of some tissue. This inter-animal variability is overcome by using each animal’s MRI image to guide the dissection. Thus, larger structures such as the caudate nucleus were easily identified and retrieved for voltammetry studies. MRI-guided dissection of the temporal poles also allowed us to retrieve tissue blocks that contained the large majority of the hippocampus or the amygdala depending on where the knife blade was positioned.

The image acquisition protocols described above were designed to obtain images of sufficient resolution to measure potential morphometric changes that occur in discrete brain regions following chronic ethanol self-administration. The chosen image resolution proved to be extremely useful for identifying the precise location of specific brain regions, especially those that were fairly small such as the Edinger-Westphal nucleus. However, it is a somewhat lengthy procedure to obtain 0.5 mm isotropic resolution images with sufficient signal-to-noise ratio to subsequently analyze in a quantitative manner. Depending on the specific goals of a particular experiment, scan time may be further reduced. We have determined that the strategies described above can be applied to locate specific ROIs using lower resolution. In conclusion, the present results clearly demonstrate that the accuracy with which discrete brain regions can be identified and dissected from the nonhuman primate brain is vastly improved using individual MRI images to guide the dissection of the nonhuman primate brain.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to express special appreciation to Dr. Christopher Wyatt for his assistance with the development of the MRI acquisition protocols. We also thank Doug Byrd for his technical assistance with the digital photography. These studies were supported by AA016748 (JBD), AA014106 (DPF), AA013510 and AA013641 (KAG), AA010760 (CDK). Work performed at the Oregon National Primate Research Center also received support from NIH grant RR00163.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Nader MA, Czoty PW. ILAR J. 2008;49:89–102. doi: 10.1093/ilar.49.1.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Porrino LJ, Smith HR, Nader MA, Beveridge TJ. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psych. 2007;31:1593–1600. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2007.08.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grant KA, Bennett AJ. Pharmacol Ther. 2003;100:235–255. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2003.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Weerts EM, Fantegrossi WE, Goodwin AK. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 2007;15:309–327. doi: 10.1037/1064-1297.15.4.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tannu NS, Howell LL, Hemby SE. Mol Psych. 2008 doi: 10.1038/mp.2008.53. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Deoganokar M, Heers M, Mahajan S, Brummer M, Subramanian T. J Neurosci Methods. 2005;149:154–163. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2005.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Johanson CE, Fischman MW. Pharmacol Rev. 1989;41:3–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Griffiths RR, Bigelow GE, Henningfield JE. In: Advances in Substance Abuse. Mello NK, editor. JAI Press; Greenwich, CT: 1980. pp. 1–90. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mello NK, Negus SS. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1996;14:375–424. doi: 10.1016/0893-133X(95)00274-H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Morgan D, Grant KA, Gage HD, Mach RH, Kaplan JR, Prioleau O, Nader SH, Buchheimer N, Ehrenkaufer RL, Nader MA. Nat Neurosci. 2002;5:169–174. doi: 10.1038/nn798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vivian JA, Green HL, Young JE, Majerksy LS, Thomas BW, Shively CA, Tobin JR, Nader MA, Grant KA. Alc Clin Exp Res. 2001;25:1087–1097. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grant KA, Leng X, Green HL, Szelia KT, Rogers LSM, Gonzales SW. Alc Clin Exp Res. 2008;32:1–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2008.00765.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Francois C, Yelnik J, Percheron G. Brain Res Bull. 1996;41:151–158. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(96)00161-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wagman IH, Loeffler JR, McMillan JA. Brain Behav Evol. 1975;12:116–134. doi: 10.1159/000124143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Paxinos G. The Rhesus Monkey Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates. Academic Press; San Diego: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Saleem KS, Logothetis NK. A Combined MRI and Histology Atlas of the Rhesus Monkey Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates. Academic Press; San Diego: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rebert CS, Hurd RE, Matteucci MJ, De LaPaz R, Enzmann DR. J Neurosci Methods. 1991;39:109–113. doi: 10.1016/0165-0270(91)90076-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Miocinovic S, Zhang J, Xu W, Russo GS, Vitek JL, McIntyre CC. J Neurosci Methods. 2007;162:32–41. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2006.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nahm FK, Dale AM, Albright TD, Amaral DG. Exp Brain Res. 1994;98:401–411. doi: 10.1007/BF00233978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Subramanian T, Deogaonkar M, Brummer M, Bakay R. Exp Neurol. 2005;193:172–180. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2004.11.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bankiewicz KS, Bringas J, Pivirotto P, Kutzscher E, Nagy D, Emborg ME. Cell Transplantation. 2000;9:595–607. doi: 10.1177/096368970000900505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Saunders RC, Aigner TG, Frank JA. Exp Brain Res. 1990;81:443–446. doi: 10.1007/BF00228139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hampton RR, Buckmaster CA, Anuszkiewicz-Lundgren D, Murray EA. Hippocampus. 2004;14:9–18. doi: 10.1002/hipo.10150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kolachana BS, Saunders RC, Weinberger DR. J Neurosci Methods. 1994;55:1–6. doi: 10.1016/0165-0270(94)90033-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McDannold N, Moss M, Killiany R, Rosene DL, King RL, Jolesz FA, Hynynen K. Mag Reson Med. 2003;49:1188–1191. doi: 10.1002/mrm.10453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ariwodola OJ, Crowder TL, Grant KA, Daunais JB, Friedman DP, Weiner JL. Alc Clin Exp Res. 2003;27:1632–1640. doi: 10.1097/01.ALC.0000089956.43262.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Budygin EA, John CE, Mateo Y, Daunais JB, Friedman DP, Grant KA, Jones SR. Synapse. 2003;50:266–268. doi: 10.1002/syn.10269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Alexander GM, Carden WB, Mu J, Kurukulasuriya NC, McCool BA, Norskog BK, Friedman DP, Daunais JB, Grant KA, Godwin DW. Neuroscience. 2006;141:453–461. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.03.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Carden WB, Alexander GM, Friedman DP, Daunais JB, Grant KA, Mu J, Godwin DW. Brain Res. 2006;1089:92–100. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.02.135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Floyd DW, Friedman DP, Daunais JB, Pierre PJ, Grant KA, McCool BA. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2004;311:1071–1079. doi: 10.1124/jpet.104.072025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Anderson NJ, Daunais JB, Friedman DP, Grant KA, McCool BA. Alc Clin Exp Res. 2007;31:1061–1070. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00394.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mugler JP, III, Brookemen JR. Magn Reson Med. 1990;15:152–157. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910150117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bachtell RK, Weitemier AZ, Galvan-Rosas A, Tsivkovskaia NO, Risinger FO, Phillips TJ, Grahame NJ, Ryabinin AE. J Neurosci. 2003;23:2477–2487. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-06-02477.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]