Abstract

Drawing on social dominance theory and the contact hypothesis, we developed and tested a two-mediator model for explaining gender differences in early adolescents’ attitudes toward gay males and lesbians. Data from more than 400 ninth graders were analyzed. As predicted, gender differences in attitudes toward gay males were partially explained by social dominance orientation (SDO) and knowing a gay male. Gender differences in attitudes toward lesbians were partially mediated by SDO, while knowing a lesbian was not a mediating variable. Beyond their mediating roles, both SDO and knowing a member of the target group each significantly added to the prediction of attitudes toward each target group. Implications for policies to reduce victimization of sexual minorities in schools are discussed.

Keywords: gay/lesbian/bisexual, gender/gender differences, victimization, school context, social dominance, contact theory, adolescence

Early adolescence is a critical period of social development and transitions. It is characterized by an increase in opposite-sex friendships, the emergence of romantic relationships, and heightened intimacy and conformity with peers (e.g., Craig, Pepler, Connolly, & Henderson, 2001). The early adolescent years are also important for developing attitudes toward various groups and social norms (e.g., Erikson, 1968; Poteat, Espelage, & Green, 2007; Ward, 1985), including feelings concerning gay males and lesbians (e.g., Horn, 2008; Mallet, Apostolidis, & Paty, 1997) as well as toward male and female roles (e.g., Fishbein, 1996; Horn, 2007; Pleck, Sonenstein, & Ku, 1994). There is also heightened concern about the gender appropriateness of one’s behavior (Pleck et al., 1994). These developmental phenomena have implications for understanding early adolescent peer aggression and victimization based on sexual orientation.

In a 2007 national survey of more than 6,200 lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) middle and high school students, Kosciw, Diaz, and Greytak (2008) found that 86% of LGBT students reported experiencing verbal harassment, 44% said they had been physically harassed, and 22% reported being physically assaulted at school on account of their sexual orientation. Analyses also revealed that male students experienced more sexual orientation-based victimization than female students. LGBT students who reported higher levels of victimization also reported feeling less safe in school, missing school more often, and having lower grade point average. In light of these findings, school-based research on psychological processes that underlie adolescents’ sexual orientation-based victimization is particularly needed because of its potential implications for designing interventions aimed at reducing such prejudice and preventing hostility toward and violence against sexual minority students.

Currently, little is known about the developmental origins of and motives for antigay bias. The research on adults’ attitudes toward gay males and lesbians has consistently documented three patterns of gender difference (e.g., Kite & Whitley, 1996; Herek, 2000). First, attitudes toward gay men are more negative than those toward lesbians. Second, heterosexual men hold more negative attitudes toward gay men than toward lesbians, whereas heterosexual women typically do not differ in their attitudes toward these two target groups. Third, the magnitude of the difference between attitudes toward gay men and lesbians is greater for heterosexual men than for heterosexual women.

A key question concerns whether the gender-related patterns in antigay bias found among adults are also found among adolescents. Furthermore, when these gender differences are found among adolescents, what can explain them? In the present study, we examined early adolescents’ attitudes toward gay males and lesbians, with a focus on documenting and explaining gender differences in such attitudes. Drawing on social dominance theory (SDT; Sidanius & Pratto, 1999) and contact theory (Allport, 1954), we developed and tested a model proposing that beliefs in social hierarchies and knowing a member of the relevant target group explain gender differences in attitudes toward gay males and toward lesbians. In the sections that follow, we provide highlights of the limited literature on sexual prejudice among adolescents. Next, we present the theoretical basis for our model. We then report results from over 400 adolescent respondents. We conclude with a discussion of implications for school-based policies and practices to reduce sexual prejudice and prevent aggression toward sexual minority adolescents.

Research on Gender Differences in Adolescents’ Sexual Prejudice

While research on adults’ sexual prejudice abounds, empirical investigation of the nature of these attitudes among adolescents is severely limited. An exception is the work conducted by Horn and her colleague (Horn, 2006, 2007; Horn & Nucci, 2003). Using social cognitive domain theory, they propose that adolescents’ sexual prejudice is multidimensional in nature. Drawing on social cognitive domain theory, they suggest that adolescents rely on several conceptually distinct frameworks and that each framework contributes differentially to adolescents’ sexual prejudice. These include moral judgments, principles of treatment toward others, and appreciation for personal autonomy, each of which may develop independently of the others. Horn (2006) noted that these developments in cognitive skills are associated with differential perceptions and acceptance of social norms among early, middle, and late adolescents. For example, early adolescence (12–14 years) is characterized by a “negation phase” during which such norms are likely to be questioned because they are perceived as arbitrary. In contrast, middle adolescents (14–16 years) tend to affirm social conventions as aids to structuring social relationships, while adhering rigidly to them due to vulnerability to peer pressure. Late adolescence (16–18 years) is marked by a more secure understanding of one’s own identity, less rigid attitudes toward social norms, and greater tolerance toward those who do not identify as heterosexual.

In a series of studies, Horn and her colleague (e.g., Horn, 2006, 2007; Horn & Nucci, 2003) examined the association among attitudes concerning (a) sexual orientation, (b) gender roles, and (c) gender norm conformity in appearance and other nonsexual behaviors in a sample of 10th and 12th graders in a Midwestern high school. A college sample was also studied. As predicted by social cognitive domain theory, results revealed that 10th graders (mean age = 15.6 years) showed more sexual prejudice than their 12th-grade counterparts (mean age = 17.6 years). Furthermore, boys reported more sexual prejudice than girls, as measured by reports of lower comfort during interactions with same sex homosexual peers as well as lack of tolerance (i.e., exclusion and teasing) toward them. However, Horn and colleagues found no gender differences in acceptance or in moral judgments with respect to same sex homosexual peers. As these researchers did not ask participants of each sex to respond to separate items about gay males as well as items about lesbians, gender differences in attitudes toward each of these two groups could not be assessed.

Research on gender differences in adolescents’ attitudes toward gay males and toward lesbians is limited and the available studies show mixed results. In an illustrative study, Van de Ven (1994) examined attitudes toward homosexuals as a group as well as attitudes toward gay males and toward lesbians in three samples differing in age and gender composition: a high school sample, a group of (mostly male) adolescent offenders, and a college student sample. Analyses revealed gender differences in attitudes toward homosexuals as a group, across the three samples. Specifically, girls and women were generally less negative toward homosexuals than boys and men. Post hoc analyses revealed that undergraduates were less negative toward homosexuals than either the high school students or young offenders. However, across the three samples, no gender differences emerged for attitudes toward gay males and toward lesbians.

By contrast, in a study of 276 seventh-, ninth-, and eleventh-grade high school students, Baker and Fishbein (1998) found that boys reported more negative attitudes toward both gay males and lesbians than girls did. Furthermore, both boys and girls expressed greater negativity toward a same-sex target than toward an other-sex target. There was also a gender by grade-level interaction in attitudes toward gay males and lesbians, suggesting a developmental difference. Specifically, boys at higher grade levels (as compared to those in lower grades) reported more negative attitudes toward both gay males and lesbians while girls in higher grades (as compared to those in lower grades) expressed more positive attitudes toward both target groups.

Overall, studies of gender differences in adolescents’ attitudes toward homosexuals in general, and toward gay males and lesbians in particular, are few in number, and the findings are not often in agreement. The inconsistent findings could be due to a variety of factors, including the specific target groups in question and the assessments used. Such inconsistencies highlight the need for more systematic investigation of adolescents’ attitudes toward gay males and toward lesbians. Furthermore, the available research has been primarily atheoretical. Theoretically grounded research promotes a better understanding of the nature of adolescents’ attitudes toward gay males and lesbians.

We propose that two theoretical perspectives—SDT and the contact hypothesis—help explain gender differences in early adolescents’ attitudes toward gay males and toward lesbians. While each of these two theories has been used to explain gender differences in sexual prejudice among adolescents or adults, we are the first to combine them in one study and test their independent and combined mediating roles in a sample of early adolescents. This integration of a social psychological theory of individual differences in beliefs in social hierarchies with a theory of intergroup relationships based on the positive effects of intergroup contact provides the foundation for the empirical portion of the present article, along with developmental insights concerning the relevance of these theories to adolescence.

SDT

SDT (Sidanius & Pratto, 1999) uses an evolutionary framework to understand intergroup attitudes. According to SDT, individuals differ in their desire for domination by certain social groups over others and in their support for group-based inequality. Assessments of social dominance orientation (SDO) incorporate both of these aspects (Sidanius & Pratto, 1999). Tests of SDT with adults have repeatedly found that members of relatively high-status groups, such as men and Whites, report higher levels of SDO than do their low-status counterparts, such as women and Blacks (e.g., Pratto, Stallworth, & Sidanius, 1997). Findings from lab and field studies with adults have consistently shown that higher SDO is associated with higher prejudice toward outgroups (e.g., Sidanius & Pratto, 1999; Whitley, 1999). Although virtually all tests of SDT have been with adults, the work of Poteat and colleagues with adolescents is a noteworthy exception. In their research, Poteat et al. (2007) examined the role of SDO, gender, and peer group context on homophobic attitudes among a sample of 213 students in seventh through eleventh grades. Overall, the boys showed both higher prejudice toward lesbians and gay men and higher levels of SDO than did the girls. Applying the SDT logic, we expect boys to report higher SDO than girls, a difference that has been shown to be related to greater negativity toward both gay males and toward lesbians (Poteat et al., 2007). Furthermore, the fact that SDO is a psychological predisposition associated with both gender and with attitudes toward sexual minorities makes it a reasonable candidate for being a mediator of gender differences in adolescents’ attitudes toward gay males and toward lesbians.

A few studies have found support for the mediating role of SDO in the relationship between social status and outgroup prejudice among adults. For example, in a series of four studies, Guimond, Dambrun, Michinov, and Duarte (2003) experimentally manipulated SDO levels and found that the social position of the respondent influences SDO, which in turn, has an effect on several types of prejudice. Although Guimond et al. did not specifically use gender as a predictor or prejudice against sexual minorities as an outcome, we believe that their findings provide a basis for SDO’s potential as a mediator between gender of the respondent (a social position) and prejudice against sexual minorities. Whitley and Ægisdóttir’s (2000) research on gender differences in college students’ attitudes toward gay men and toward lesbians provides further support for the mediating role of SDO. In line with much adult research on sexual prejudice, they found that heterosexual men reported more negative attitudes toward gay males versus lesbians. However, heterosexual women’s attitudes toward these target groups did not differ. A significant proportion of the gender difference in attitudes toward gay males was explained by SDO. These findings provide additional justification for testing whether SDO is a mediator of early adolescents’ gender differences in attitudes toward gay males and lesbians. Our underlying premise is that being in a dominant social position based on one social category (e.g., gender) can predict levels of prejudice toward a subordinate group based on a different social category (e.g., sexual orientation) for which that individual is also a dominant group member.

Knowing a Gay Male or Lesbian

Contact is one of the most effective ways of reducing intergroup prejudice (Allport, 1954). According to Allport, when certain facilitating conditions are met, intergroup interactions afford individuals the opportunity to acquire new information about an outgroup and challenge negative beliefs about them, which in turn can reduce intergroup tension and prejudice. Using data from adolescents, Molina and Wittig (2006) showed that one of the most important of these conditions for reducing racial prejudice is acquaintance potential, defined as the opportunity to get to know members of the racial/ethnic outgroup.

Sexual prejudice research on adults has documented a gender difference in knowing a gay person and that knowing a gay person is an important predictor of lower sexual prejudice. For example, Herek and Capitanio (1996) showed that heterosexual women are more likely to know a gay person than heterosexual men, a differential that was related to lower levels of sexual prejudice. Furthermore, Whitley (1990) examined male and female college students’ feelings about interactions with gay men and lesbians using the Index of Homophobia (IHP) and their attitudes toward gay men and lesbians using the Heterosexual Attitudes Toward Homosexuals (HATH) scale (Larsen, Reed, & Hoffman, 1980). Four important findings were reported. First, those students who knew a gay person reported more positive attitudes toward homosexuals on both the IHP and the HATH. Second, heterosexual men were less likely to have contact with a gay male than heterosexual women were with a lesbian. Third, IHP results showed that respondents reported more homophobia toward a same-sex target than toward an other-sex target. This pattern was replicated for male, but not for female, participants’ attitudes, as measured by the HATH. Fourth, analysis revealed that the magnitude of the difference between attitudes toward gay males and lesbians was greater for male respondents than for female respondents. Thus, Whitley’s (1990) results suggest that knowing a gay male or lesbian contributes to gender differences in attitudes toward these two target groups.

A review of literature on the role of contact with respect to adolescents’ sexual prejudice yielded only one published report. In a study of nearly 1,500 boys aged 15 to 19, Marsiglio (1993) examined the association between willingness to have a gay friend and attitudes toward gay men. Participants were asked to indicate the extent to which they agreed with the following two items: “The thought of men having sex with each other is disgusting” and “I could be friends with a gay person.” In line with the contact hypothesis, results showed that boys who were willing to befriend a gay person reported more positive feelings toward gay men than those boys who were not. Based on our review of the literature on contact and sexual prejudice, we expect that (a) adolescents who know a gay male or a lesbian will have more positive attitudes toward each of these groups and (b) that adolescents’ knowing a gay male or lesbian may function as a mediator between gender of respondent and attitudes toward these two sexual minority groups.

The Present Research

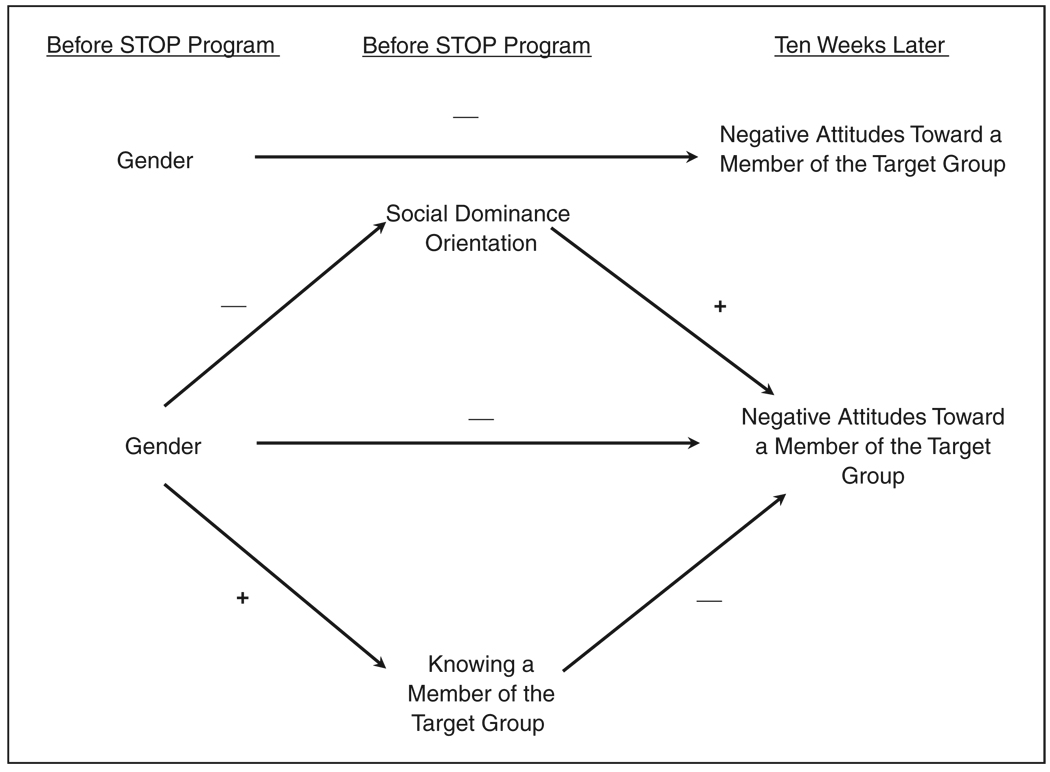

The present research had two main goals. The first goal was to examine in what ways adolescent boys and girls differ in their attitudes toward gay males and toward lesbians. The second goal was to explain the sources of these differences. Drawing on the results of research concerning SDO as well as those on knowing a member of a target group, we developed and tested a two-mediator model of attitudes toward gay males and toward lesbians. The model states that both belief in social hierarchies and knowing either a gay male or lesbian partially account for gender differences in adolescents’ attitudes toward gay males and lesbians, respectively. Inclusion of both mediators allows us to test for both their independent as well as joint contributions to the overall explanation of gender differences in early adolescents’ sexual prejudice. Figure 1 depicts the generalized model. Valences shown in the figure are dependent on the coding and scoring of scales. While it is possible that knowing a member of a target group might lead to increased prejudice, the context in which we test the model is one which is designed to promote more positive attitudes toward outgroup members (e.g., by dispelling stereotypes). Details concerning the scales and context are described in the Method section.

Figure 1.

Hypothesized model of mediation of gender on attitudes toward sexual outgroups

As research on gender differences in early adolescents’ sexual prejudice is limited, the first task is to document such differences. To this end, we tested the following three hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1. There will be a main effect of gender of participant such that boys will report more negative attitudes toward both gay males and lesbians than girls will (Baker & Fishbein, 1998; Van de Ven, 1994).

Hypothesis 2. There will be a main effect of gender of target such that attitudes toward gay males will be more negative than those toward lesbians, irrespective of the gender of the participants (Herek, 2000).

Hypothesis 3. There will be a significant Gender of participant × Gender of target interaction.

Specifically, boys will report more negative attitudes toward gay males than girls do, and boys will report more negative attitudes toward lesbians than girls do. This is in accord with many prior studies showing that males are more homophobic than females. Furthermore, boys will report more negative attitudes toward gay males than toward lesbians (Kite & Whitley, 1996). Girls will report more negative attitudes toward lesbians than toward gay males (Kite & Whitley, 1996). However, following Baker and Fishbein (1998) and Van de Ven (1994), girls may show no differences in attitudes between these two target groups.

We developed the following two hypotheses to test our two-mediator model of the relationship among early adolescents’ gender, SDO, knowing a gay male or lesbian, and attitudes toward each of these target groups:

Hypothesis 4. The difference between boys’ and girls’ attitudes toward gay males will be partially explained by both SDO and knowing a gay male (Guimond et al., 2003; Herek & Capitanio, 1996; Whitley, 1990; Whitley & Ægisdóttir, 2000).

Hypothesis 5. The difference between boys’ and girls’ attitudes toward lesbians will be partially explained by SDO and knowing a lesbian (Guimond et al., 2003; Whitley, 1990; Whitley & Ægisdóttir, 2000).

In addition to demonstrating mediating roles for SDO and acquaintance, we expect to show that these variables also independently add to the prediction of the various hypothesized gender differences.

Method

Participants

A cross-sectional design was used to collect six semesters of data, each consisting of a different cohort of students. Data from 665 students enrolled in a mandatory life skills course in one of two suburban public high schools in a large U.S. public school district were available for analysis. This represents nearly 90% of the six cohorts of students enrolled in the life skills course at the two schools. Students’ participation in the surveys required permission from a parent or guardian as well as assent from the students themselves. Prior to combining the data across semesters a MANOVA was conducted, using semester of data collection as the predictor and the variables to be used in the hypothesis testing as the outcomes. This analysis allowed us to test for mean differences between semesters on the variables of interest. Such differences when found, indicate semesters of data that should be removed from the database (Huberty & Olejnik, 2006, pp. 68–69). The remaining semesters of data were then aggregated. The MANOVA results revealed significant interactions between the variables of interest and two of the semesters of data collection. Therefore, the Spring 2004 data (from one school site) and Fall 2005 data (from the other school site) were eliminated from the data set, reducing the sample size by 210. The remaining semesters (Fall 2003, Fall 2004, Spring 2005, and Spring 2006) comprised data from 455 students. Of these, 19 students who were not in the ninth grade or did not indicate their grade were excluded from the study. Two students were dropped from the sample due to the absence of a response to the item concerning gender. One outlier on the SDO measure was dropped from the sample.

The final sample consists of 433 ninth graders (216 boys and 217 girls), ranging in age from 13 to 16 years (M = 14.2 years, SD = 0.5). Limiting our sample to ninth graders allows us to focus exclusively on students in their 1st year of high school, an important period during which new social norms are being formed and new social networks develop. Researchers (e.g., Schaffer, 1999) regard the onset of adolescence to be based on two milestones: a growth spurt and puberty. These physical changes are likely to be linked to emergent psychological gender differences (e.g., Hill & Lynch, 1983). Using the means and standard deviations of age distributions for attainment of these milestones for each gender cited in Schaffer (1999), a minority of the girls and the majority of the boys in our sample are likely to be in early adolescence. Our sample was ethnically diverse with 11 African Americans, 91 Asian Americans, 111 European Americans, 121 Hispanic Americans, 48 multiracial individuals, 33 who responded “Other,” and 5 who did not respond to this question.

Procedure

All participants were enrolled in a life skills course that met 5 hours per week for about 10 weeks. The study protocol was prior approved by the Institutional Review Board of the university with which the first and third authors are affiliated. College students were trained and served as facilitators for discussions concerning Students Taking Out Prejudice (STOP) during one of the life skills class meetings each week. These discussions were designed to increase students’ awareness about racism, sexism, and heterosexism. The discussion on heterosexism occurred near the middle of the series of discussions. The high school students’ credentialed life skills teacher directly supervised all class meetings. Trained research assistants, who did not lead the STOP discussions, administered surveys prior to and following the series of STOP discussions on class meeting days when the college student facilitators were not present. The self-report questionnaires assessed attitudes toward various groups, perceptions of the classroom interracial climate, strength of ethnic identity, and standard demographic questions such as gender, age, grade, and ethnic background as well as various other scales. For the purposes of this study, we focus only on the subset of measures that pertain to our model. The predictor (gender of respondent) and mediators (SDO and knowing a member of the target group) in our model were assessed via surveys administered prior to the inception of the STOP discussions. The outcomes (attitudes toward gay males and toward lesbians) were assessed at or near the end of the series of discussions via surveys that included additional assessments that are not the focus of the present study.

Measures

Gender of participants

Using a closed-ended question, participants were asked to indicate their gender prior to STOP program. Male respondents’ gender was coded 0 and female respondents’ gender was coded 1.

Sexual orientation of participants

This variable was not directly assessed because permission was not granted to ask respondents’ sexual orientation. We note that Horn and her colleague (Horn, 2006, 2007; Horn & Nucci, 2003) documented that about 6% of their 10th- and 12th-grade sample of high school students in the Midwest reported being gay, lesbian, or bisexual.

SDO

To assess the extent to which participants endorsed belief in social hierarchies, we used their responses to a six-item version of the SDO scale (J. Sidanius, personal communication, September 9, 2004). These items were assessed prior to the STOP program. Three items measured endorsement of social hierarchies including “If certain groups stayed in their place, we would have fewer problems,” “Inferior groups should stay in their place,” and “Sometimes other groups must be kept in their place.” Three items measured endorsement of egalitarian beliefs (reverse coded) including “Group equality should be our ideal,” “We should do what we can to equalize conditions for different groups,” and “Increased social equality.” We eliminated the item “Increased social equality” from the hypothesis testing because some students reported having trouble understanding the statement. Thus, the analyses were conducted on a 5-item version of the SDO scale. Cronbach’s alphas were comparable for the 6- and 5-item scales (6 items: α= .83; 5 items: α= .74). Responses ranged from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). Mean scores were used in the analyses (boys: M = 3.05, SD = 1.09, α= .74; girls: M = 2.68, SD = 1.05, α= .72), with higher numbers indicating higher levels of beliefs in social hierarchies.

Knowing a gay male or lesbian

To assess whether participants knew a gay male or lesbian, two questions were asked: “Do you know a male that is gay?” and “Do you know a female that is a lesbian?” Participants responded by indicating either “no” (coded 0) or “yes” (coded 1). This variable was assessed prior to the STOP program.

Attitudes toward gay males and toward lesbians

To assess attitudes toward gay males and toward lesbians, six items from the 20-item Attitudes Toward Lesbians and Gay Males scale (ATLG: Herek, 1988, 1994) were used. Three items from that scale were used to assess attitudes toward gay males (ATG: boys α= .74; girls α= .70) and three parallel items were used to assess attitudes toward lesbians (ATL: boys α= .68; girls α= .66). These items were “I would not be too upset if I learned my son (daughter) were gay” (reverse-coded), “I think gay males (lesbians) are disgusting,” and “Male (Female) homosexuality is merely a different lifestyle that should not be condemned” (reverse-coded). Responses ranged from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). Items were averaged to create two mean scores, one for attitudes toward gay males (ATG, M = 3.73, SD = 1.62) and one for attitudes toward lesbians (ATL, M = 3.41, SD = 1.40) with higher numbers indicating greater negativity toward the target group. These items were assessed after the STOP program.

Results

The first goal was to examine whether the boys and girls in our study differed in levels of SDO, knowing a member of each of the target groups and in their attitudes toward lesbians and gay males. The second goal was to test our two-mediator model proposing that both belief in social hierarchies and knowing either a lesbian or gay male partially account for gender differences in adolescents’ attitudes toward lesbians and toward gay males. First we report descriptive statistics, followed by results of our main analyses.

Gender Differences in SDO and Knowing a Gay Male or Lesbian

Results of a one-way ANOVA showed that boys reported significantly higher levels of SDO, M = 3.05, SD = 1.09, than girls, M = 2.68, SD = 1.05, F(1, 431) = 12.99, p < .001, η2 = .03, as expected. Another one-way ANOVA showed that boys’ mean response to the item concerning knowing a gay male was lower, M = .40, SD = .49, than that of girls, M = .65, SD = .48, F(1, 431) = 26.85, p < .001, η2 = .06. However, results of the third one-way ANOVA showed that boys (M = .53, SD = .50) and girls (M = .59, SD = .49) did not differ in whether they knew a lesbian, F(1, 431) = 1.41, ns, η2 = .003.

Gender Differences in Sexual Prejudice Toward Gay Males and Lesbians

A repeated-measures ANOVA was run, using gender of participant as the predictor and mean ATG and ATL scores as the outcomes, to examine whether boys and girls differed in their attitudes toward gay males and lesbians. As predicted by Hypothesis 1, results revealed a significant main effect of gender of participant on attitudes toward gay males and lesbians, F(1, 431) = 38.13 p < .001, η2 = .08. Specifically, boys reported significantly higher prejudice toward the target groups (M = 3.98, SD = 1.47) than girls did (M = 3.17, SD = 1.42).

In accord with Hypothesis 2, there was a significant main effect of gender of target, Wilks’s Λ = .909; F(1, 431) = 43.33, p < .001, η2 = .09, such that scores on ATG (M = 3.73, SD = 1.62) were significantly higher than those on ATL (M = 3.41, SD = 1.40). This finding indicates that respondents reported greater prejudice toward gay males than toward lesbians, regardless of gender of respondent.

As predicted by Hypothesis 3, we obtained a Participant gender × Target gender interaction, Wilks’s Λ = .850; F(1, 431) = 76.12, p < .001, η2 = .15, such that the magnitude of the difference between ATG and ATL scores was significantly greater for boys (.73) than for girls (−.10). The descriptive statistics associated with this interaction were as follows: boys’ ATG: M = 4.34, SD = 1.56; girls’ ATG: M = 3.12, SD = 1.44; boys’ ATL: M = 3.61, SD = 1.39; girls’ ATL: M = 3.22, SD = 1.39. As hypothesized, boys reported higher ATG scores than girls did, F(1, 431) = 72.14, p < .001, η2 = .14, and boys reported higher ATL scores than girls did, F(1, 431) = 8.41, p < .01, η2 = .02. Furthermore, as expected, boys reported significantly higher ATG scores than ATL scores, F(1, 431) = 116.89, p < .001, η2 = .21. However, girls showed no significant difference between ATG and ATL scores, F(1, 431) = −2.30, ns, which is consistent with some studies but discrepant with other reports.

Test of Two-Mediator Model

To test our two-mediator model, three main associations need to be established. The first is that the association between gender of respondent and each of the respective dependent variables (ATG and ATL) is significant. The second is that the association between gender and each of the two proposed mediators (SDO and knowing a member of the target group) is significant. The third is that the association between each of the proposed mediators and their respective dependent variables is significant. Once all of these associations are established, the last step is to show that the direct association between gender of participant and each of the respective dependent variables is significantly reduced when the mediators are entered into the model.

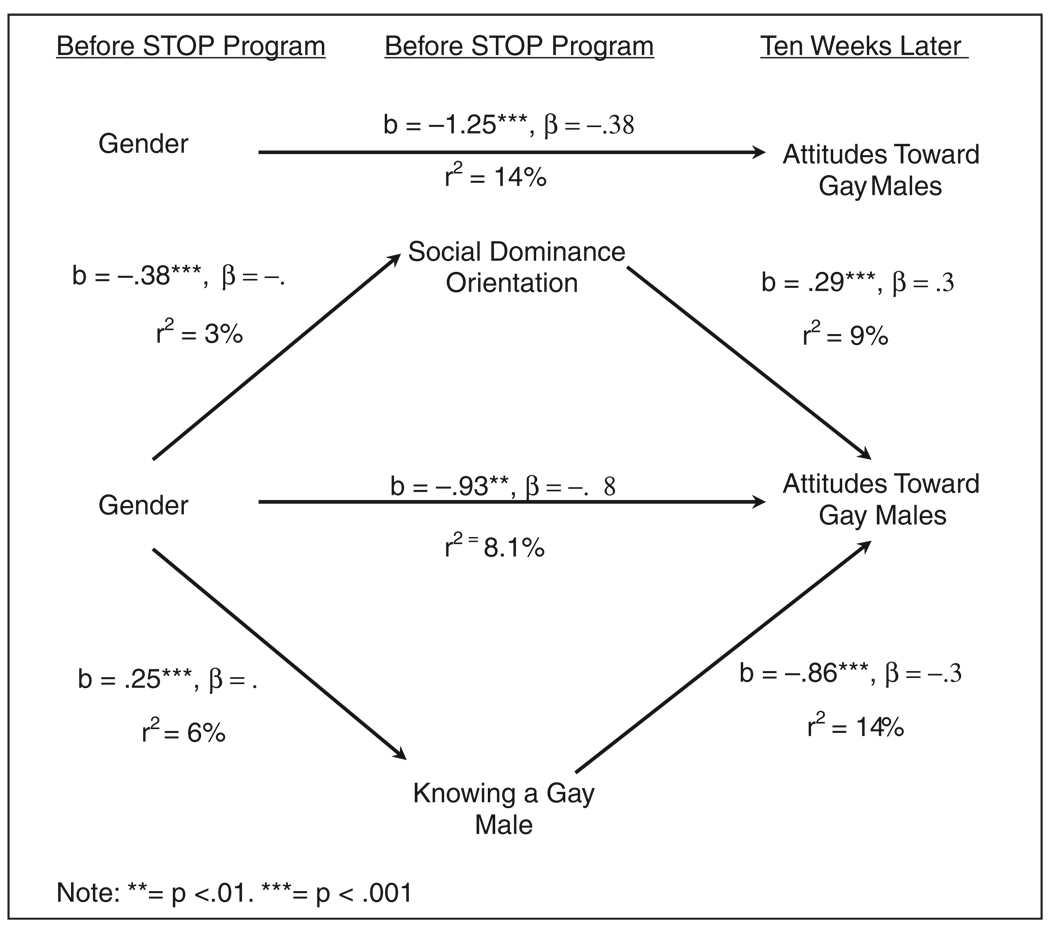

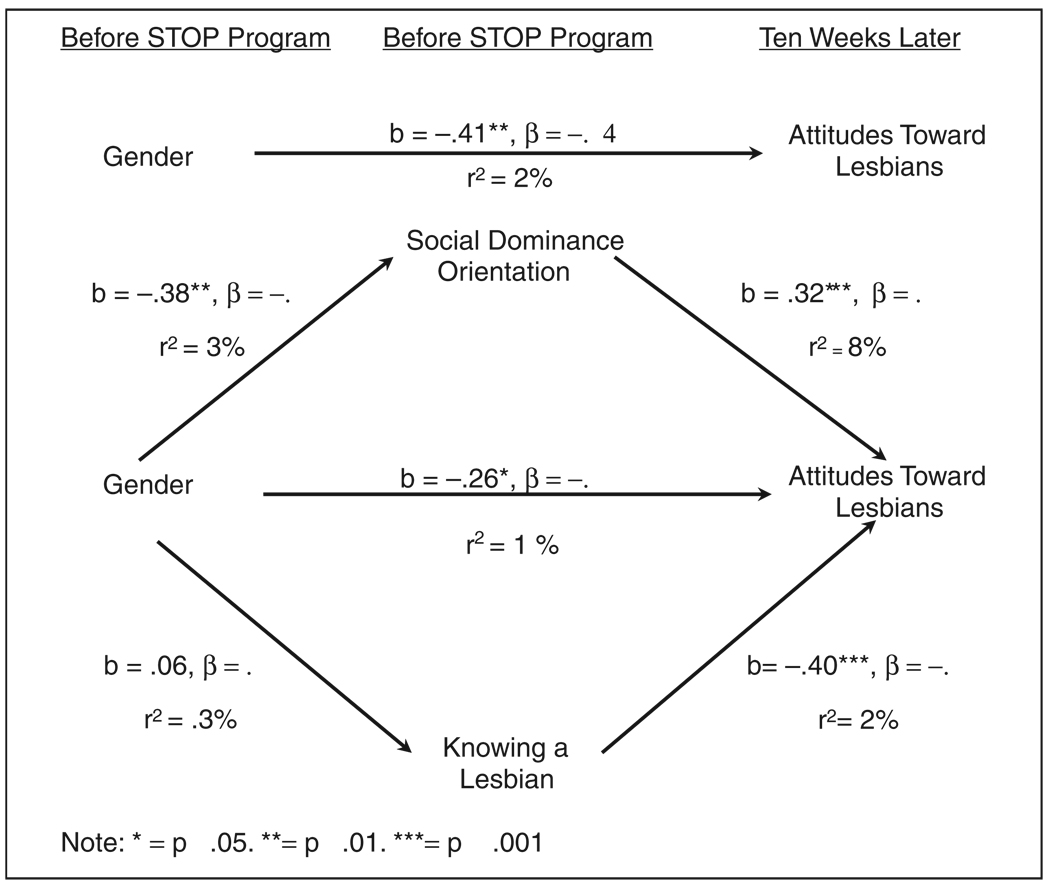

A variety of methods are available that incorporate these steps. We used the method provided by Preacher and Hayes (2008) to test the significance of the two proposed mediators simultaneously and compare the strength of the indirect effects of each of them. This approach uses SPSS with additional macro-syntax found on the Web site at http://www.comm.ohio-state.edu/ahayes/spss%20programs/indirect.htm. According to Preacher and Hayes (2008), the results calculated by using the Web site syntax are equivalent to SEM programs for the kind of two-mediator model we tested. Note that our models incorporate both a binary predictor (gender of participant) and binary mediators (knowing a gay male or lesbian). Previous research (Li, Schneider, & Bennett, 2007) showed that the use of a binary predictor typically underestimates its importance. Furthermore, when binary variables are used as potential mediators, they typically underestimate the magnitude of the mediation, thus providing a more conservative test of our hypotheses. Both unstandardized and standardized regression coefficients associated with these analyses are shown in Figure 2 and Figure 3.

Figure 2.

Mediation of gender on attitudes toward gay males by social dominance orientation and knowing a gay male

Figure 3.

Mediation of gender on attitudes toward lesbians by social dominance orientation and knowing a lesbian

Mediation Analysis for the Gender Difference in Attitudes Toward Gay Males

Figure 2 displays results of the mediation analyses implicating SDO and knowing a gay male as mediators of the relationship between gender of participant and ATG. As predicted, gender significantly predicted ATG (b = −1.25, β = −.38, p < .001, r2 = .14), SDO (b = −.38, β= −.17, p < .001, r2 = .03) and knowing a gay male (b = .25, β= .25, p < .001, r2 = .06). That is, boys, as compared to girls, showed more negative attitudes toward gay males, showed higher SDO, and were less likely to know a gay male. As expected, SDO scores significantly predicted ATG (b = .29, β = .30, p < .001, r2 = .09), such that higher SDO was associated with more negative attitudes toward gay males. Knowing a gay male significantly predicted a more positive attitude toward gay males (b = −.86, β = .37, p < .001, r2 = .14). When the mediators were included in the association between gender and ATG, the coefficient was significantly reduced (z = −4.95, p < .001), but the relationship of gender to ATG remained significant (b = –.93, β = .28, p < .01, r2 = .08). This indicates partial mediation. The relationship of gender to ATG was significantly mediated by SDO (z = −2.80, p < .005) as well as by knowing a gay male (z = −3.92, p < .001). Neither of the confidence intervals included zero (SDO: lower = −.20, upper = −.05; knowing a gay male: lower = −.34, upper = −.12). Together, these findings indicate that SDO as well as knowing a gay male were significant partial mediators of the gender-ATG association.

Overall, the mediation analysis revealed that gender of participant accounts for 14.0% of the variance in ATG, about half of which is explained by the two mediators combined. Furthermore, SDO independently added 4.5% and knowing a gay male independently added an additional 8.0% to the prediction of ATG. Thus, gender, SDO, and knowing a gay male accounted for 26.5% of the variance in ATG.

Mediation Analysis for the Gender Difference in Attitudes Toward Lesbians

Figure 3 displays results of the mediation tests concerning the extent to which SDO and knowing a lesbian help explain the relationship between gender of participant and ATL. As expected, gender significantly predicted ATL (b = −.41, β = −.14, p < .01, r2 = .02) and SDO (b = −.38, β = –.171, p < .001, r2 = .03). That is, boys, as compared to girls, showed more negative attitudes toward lesbians and higher SDO. Contrary to our hypothesis, gender did not significantly predict knowing a lesbian (b = .06, β = .06, ns, r2 = .003). As predicted, SDO significantly predicted ATL (b = .32, β = .27, p < .001, r2 = .08), such that higher SDO was associated with a more negative attitude toward lesbians. Likewise, knowing a lesbian significantly predicted a more positive attitude toward lesbians (b = −.40, β = −.16, p < .001, r2 = .02). When the potential mediators were included in the association between gender and ATL, the coefficient was significantly reduced from −.41 to −.26 (z = −3.12, p < .003), but the association between them remained significant (b = −.26, β = −.05, p < .05, r2 = .01), showing partial mediation. The relationship of gender to ATL relationship was partially mediated by SDO (z = −2.97, p < .002), while knowing a lesbian did not play a role (z = −1.11, ns). This was corroborated by the fact that the confidence interval associated with the importance of SDO did not include zero (SDO: lower = −.22, upper = −.05), while the confidence interval associated with knowing a lesbian included zero (lower = −.08, upper = .01).

Overall, the mediation analysis revealed that gender accounts for only 2.0% of the variance in ATL, about half of which is explained by SDO. Furthermore, SDO independently added 6.0% and knowing a lesbian independently added an additional 2.1% to the prediction of ATL. Thus, gender, SDO, and knowing a lesbian accounted for 10.1% of the variance in ATL.1

Discussion

Our findings will be discussed in terms of their contribution to our understanding of gender differences in early adolescents’ attitudes toward gay males and lesbians and their practical implications as they relate to youth and policy. We also call attention to the limitations and strengths of the study and suggest directions for future research.

First, we will discuss results relating to Hypotheses 1 through 3, documenting gender differences in early adolescents’ attitudes toward gay males and lesbians. Overall, we showed that the gender differences in attitudes toward gay males and lesbians that are typically found among adults appear early in adolescence. In accord with our first hypothesis, the adolescent boys in our study showed greater prejudice against both gay males and lesbians than did the girls. This is in agreement with several prior studies in which males and females expressed attitudes toward gay males and lesbians. Although comparisons across studies are difficult when the assessments differ, a tentative comparison can be made between our results (based on responses to items adapted from the Herek [1988] ATLG scale) and Herek’s (1994) results with adults (who responded to the entire 20-item ATLG scale). The differential between male and female respondents is similar in magnitude across the two studies, while the means (adjusted for scale values) are higher for the adults, which is indicative of greater sexual prejudice.

Hypothesis 2 was also confirmed. In agreement with results found in most such studies with adults (e.g., Herek, 2000; Kite & Whitley, 1996), the adolescents in our study reported more negative attitudes toward gay males than toward lesbians, regardless of the gender of the participants.

The first part of our third hypothesis was also supported: boys reported more negative attitudes toward gay males as compared to lesbians. This is in accord with Kite and Whitley’s (1996) findings with adults. The remaining part of our third hypothesis concerns girls’ attitudes toward gay males versus lesbians. Prior research suggested we might obtain either no difference (e.g., Kite & Whitley’s [1996] research with adults) or that girls would show greater negativity toward a target person of the same gender (in accord with research on adolescents by Baker & Fishbein, 1998 and Van de Ven, 1994). Our results showed no difference.

Future research should be undertaken to attempt to replicate the pattern of results we obtained relating to Hypothesis 3. If the pattern is robust, several explanations for it are plausible. Perhaps early adolescent boys are more negative toward the sexual minority of their own gender so as to reduce the threat of being associatively miscast (Eidelman & Biernat, 2003) as a homosexual, while this threat may not be as salient or strong for early adolescent girls. The pattern of results may also be understood as a correlate of traditional attitudes about males. For example, Pleck et al. (1994) theorized that boys are generally subject to greater punishment for violating the norms of masculine behavior than girls are for violating the norms for femininity. To test whether early adolescent boys and girls perceive differential consequences of gender norm violation, future research on this topic would benefit from including assessments of attitudes toward male and female roles as well as expected consequences of violating gender role norms. Measures of these constructs have been used by Horn (e.g., Horn, 2006), though not yet in a study in which adolescents’ attitudes toward both same- and other-sex targets are assessed.

Next, we discuss results relating to Hypotheses 4 and 5, testing our two-mediator model for explaining gender differences in early adolescents’ attitudes toward sexual minorities. Hypothesis 4 was confirmed: The gender difference in attitudes toward gay males was partially explained by both SDO and knowing a gay male. Each of these two variables also independently predicts such prejudice, over and above their mediating roles. From a theoretical perspective, these findings implicate both social dominance and contact as factors in the development of early adolescents’ prejudice against gay males. Social dominance may arise from a variety of motives. These include the need to feel superior to others, avoid social stigma (including being associatively miscast as a member of the stigmatized group), decrease anxiety, or resist having one’s social status threatened. One possibility is that such motives may influence those heterosexual boys who are high in social dominance to distance themselves from boys they perceive as homosexual, thereby leading to fewer opportunities for contact, which would otherwise help improve their attitudes. Future research with early adolescents is needed to test this two-step pathway to sexual prejudice against gay males.

Hypothesis 5 proposed that both SDO and knowing a lesbian would mediate the gender difference in attitudes toward lesbians. This hypothesis was only partially confirmed. Mediation analyses showed that early adolescent boys’ stronger belief in the legitimacy of social hierarchies, as compared to that of girls, partially explains their greater prejudice against lesbians. However, knowing a lesbian did not explain any of the gender difference in attitudes toward lesbians. Nevertheless, knowing a lesbian independently contributed to the prediction of a more positive attitude toward lesbians.

Several implications may be drawn from the results of our tests of Hypotheses 4 and 5. First, early adolescent boys’ greater prejudice, than early adolescents girls, toward gay males and toward lesbians is partially explained by their stronger belief in the legitimacy of social hierarchies. This confirms that being in a dominant social position on one social category (i.e., gender) is associated with greater prejudice toward individuals in a subordinate group based on a different social category (i.e., sexual orientation) for which that individual is also a dominant group member. Moreover, for both sexes, knowing a gay male or a lesbian is associated with somewhat more positive attitudes toward each of these respective groups.

Strengths and Limitations of the Present Study

The fact that we measured the predictor and mediators in our models prior to our participants’ taking a ninth-grade life skills class while the outcomes were assessed about 10 weeks later has both advantages and disadvantages. While this sequence had the advantage of conforming to a possible causal sequence, the chronological separation of the predictor and mediators on the one hand and the outcomes on the other is likely to have underestimated the strength of relationships between the two sets of variables. However, because our study was conducted in the context of a school intervention, the magnitude of the relationships between variables assessed prior to the intervention and those assessed following it could have been influenced by the intervention itself. Whether our results would have been obtained with a normative sample not enrolled in such a course is unknown. Furthermore, as our analyses did not include repeated measures of the same variables, we could not address changes over time.

Another measurement issue concerns the contact assessment. A more sensitive measure would have asked not only about knowing a member of the target group but also whether participants were friends with a gay male or with a lesbian and if so, how many individuals of each group as well as how comfortable participants were interacting with a gay male or a lesbian. Furthermore, some authors have suggested that the context in which such interactions occur need to be taken into account, since level of comfort varies with the intimacy of the situation (e.g., Horn, 2006, 2008).

A strength of the present research is that separate subscales concerning attitudes toward gay males and toward lesbians were used and participants of both sexes were asked questions about each of these target groups. This allowed us to assess early adolescents’ attitudes toward each target group rather than toward homosexuals in general or only toward same-sex targets. However, the ATLG scale from which we selected items was designed for use with adults and has not been validated for use with adolescents. Poteat et al. (2007) used the full ATLG scale with seventh through eleventh graders to demonstrate the relationship between changes in the social dominance of peer groups and their attitudes toward lesbians and gay males. Nevertheless, future studies of early adolescents would benefit from questions that are tailored to the experiences of early adolescents and validated on the specific age groups used in the studies.

Due to space limitations, we used 3-parallel pairs of items based on Herek’s (1988, 1994) 20-item scale. A future study is needed to test the factor structure of the full Herek scale using an adolescent sample. Results would be helpful to researchers faced with choosing a subset of items for adolescents, when use of the full scale is impractical. In addition, the internal consistency of each of the scales we used to assess attitudes toward lesbians, attitudes toward gay males, and SDO was only adequate. Consequently, measurement error may have led to underestimation of the relationships between the variables.

Unfortunately, we were not given approval to inquire about our early adolescent participants’ sexual orientation. Lack of information about the sexual orientation of the participants is a problem shared by nearly all such studies of children and adolescents. An important exception is the work of Horn (e.g., Horn, 2006). In accord with her statistics on youth in a Midwestern high school as well as on results of a 2004 national poll commissioned by the Gay, Lesbian and Straight Education Network (http://www.glsen.org/cgi-bin/iowa/all/news/record/1970.html), it is likely that about 95% of our respondents of both sexes would have reported being heterosexual. Therefore, although we have good reason to believe that our findings are indicative of early adolescent heterosexuals’ attitudes toward gay males and lesbians, we cannot claim that the results of our analyses would generalize to gay male or lesbian early adolescent participants. And, because our sample was mainly composed of early adolescents, it is likely that some of our participants were in a period of questioning their sexual orientation. Overall, the lack of a direct assessment of sexual orientation of our participants adds error variance to our study.

Future Research

We have several suggestions for future research, in addition to those mentioned in the section on Strengths and Limitations. The first two suggestions relate to the mediators in our model of adolescent gender differences in attitudes toward sexual minorities. With respect to social dominance, Poteat et al. (2007) found that peer group SDO was more predictive of attitudes toward gay males and attitudes toward lesbians than individual SDO scores were. Future studies should include a measure of the SDO of participants’ social networks so as to draw comparisons with their findings.

Our second suggestion relates to the role of contact in educational settings. Molina and Wittig (2006) showed that some classroom contact conditions are more important than others in predicting racial/ethnic prejudice among early adolescents. Future research on gender differences in early adolescents’ prejudice toward sexual minorities would benefit from this type of fine-grained analysis by including assessments of additional components of intergroup contact. Third, Duckitt and colleagues (e.g., Duckitt, 2006; Duckitt & Sibley, 2007) have developed and tested a dual-process model of intergroup prejudice implicating authoritarianism as well as SDO and research by Whitley and Ægisdóttir (2000) suggests that authoritarianism operates jointly with SDO to support a variety of prejudices. For these reasons, future research on gender differences in sexual prejudice among early adolescents would benefit from inclusion of a measure of authoritarianism.

Finally, there is a need for studies that incorporate (a) a more developmental approach such as a longitudinal design (Poteat et al., 2007), (b) systematic examination of different cohorts (e.g., Horn, 2006) and how they may differ on the variables in our model, and (c) diverse situational assessments, including peer social networks (e.g., Horn & Nucci, 2003).

Practical Implications

An immediate value of research such as ours lies in what the results can tell us about focusing our future research efforts, so that subsequent research-based interventions to improve young people’s attitudes toward gay males and lesbians will be more successful. Our findings suggest that sexual prejudice research would benefit from focusing on how SDO develops among adolescents and the conditions under which acquaintance with a member of a sexual minority attenuates such hierarchy-supporting beliefs.

The present research also has implications for designing and implementing interventions. We found that many ninth-grade students report negative attitudes toward gay males and (to a lesser extent) lesbians. This highlights the need for early intervention to prevent victimization of students who are perceived to be homosexual, especially boys who are perceived to be gay. Multilevel strategies for sexual prejudice prevention are needed to combat structural-, situational-, and individual-level bias. Boards of education, school-system administrators, parents, school-site staff, and students themselves have roles to play in establishing an atmosphere that resists antihomosexual prejudice. For example, as research has shown that sexual minorities are being victimized as early as middle school (e.g., Poteat & Espelage, 2007), age-appropriate educational materials need to be designed for use beginning in elementary schools. The schools in our study are part of a large urban school district, which provides a positive example. Teacher training and new teacher orientation includes modules on how to establish a classroom climate of respectful treatment that is consistent with the Board of Education’s written commitment to respectful treatment of all persons, which includes specific mention of sexual orientation. This resolution was passed in 1988 and has been reaffirmed twice. Districtwide educational materials are gay-affirming and include textbooks promoting respect for sexual minorities as early as the elementary grades (J. Chiasson, personal communication, August 27, 2008). A district office for educational equity is responsible for conducting workshops for school staff and interventions with students to prevent victimization based on various dimensions of group membership, including sexual orientation. Nevertheless, focus groups with some of the students in the present study (Whitehead, Hinze, & Futrell, 2004) suggest that the behavioral norms in school sites fall short of the ideal.

Our main findings are that SDO and self-reports of acquaintance with a member of the target group help explain gender differences in early adolescents’ attitudes toward sexual minorities. In addition, we showed that these two constructs independently account for additional variance in levels of sexual prejudice among adolescents of both sexes. Taken together, our results suggest that school-level intervention efforts to prevent victimization of sexual minorities will be more successful if they (a) promote egalitarian beliefs, (b) emphasize working toward equalizing conditions for various minority groups, and (c) provide an opportunity for students to get to know a gay male or lesbian. Fortunately, there are organizations (e.g., Gays and Lesbians Initiating Dialogue for Equality [GLIDE]) in urban areas that encompass all three recommendations by providing gay and lesbian guest speakers who are specially trained to lead dialogues that promote egalitarian beliefs as well as equal and respectful treatment of sexual minorities.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Sun-Mee Kang, Brandy Gadino, and Andrew Ainsworth for statistical advice and Adam Murray for assistance with the literature review. The authors gratefully acknowledge the support and cooperation of the students, parents, faculty, and administrators of the high schools in which the data were collected.

Financial Disclosure/Funding

This research was supported in part by National Institutes of Health MARC funding to the first author and National Institutes of Health GM MBRS SCORE Grant NGAS06 GM 48680 to the third author.

Biographies

Jessieka Mata earned BA and MA degrees in psychology at California State University, Northridge, where she was supported by National Institutes of Health MARC and RISE fellowships. She has coauthored presentations relating to racial/ethnic prejudice, religious identity, and attitudes toward gay males and lesbians.

Negin Ghavami is a doctoral candidate in social psychology at University of California at Los Angeles. Her research focuses on how devalued social identities affect individuals’ experiences, how majority group members perceive and interact with minority group members, and their impact. She aims for a better understanding of attitudes toward and beliefs about stigmatized groups.

Michele A. Wittig is a professor of psychology at California State University, Northridge. She conducts theory-based research on acculturation, identity, and interventions to improve intergroup relationships among adolescents and is a past president of Divisions 9 (social issues) and 35 (psychology of women) of the American Psychological Association.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interests with respect to the authorship and/or publication of this article.

Using the same analytic strategy, we tested whether social dominance orientation, knowing a gay male and knowing a lesbian mediate gender differences in the discrepancy between attitudes toward gay males versus lesbians. The dependent variable consisted of difference scores calculated by subtracting each respondent’s attitudes toward lesbians (ATL) score from his or her attitudes toward gay males (ATG) score. Results showed that gender accounts for 15.0% of the variance in the ATG-ATL difference (about 27.0% of which is explained by knowing a gay male) and that knowing a gay male independently adds 1.6% to the equation. Social dominance orientation and knowing a lesbian did not significantly contribute to the prediction of the ATG-ATL difference.

References

- Allport G. The nature of prejudice. Cambridge, MA: Perseus Books; 1954. [Google Scholar]

- Baker JG, Fishbein HD. The development of prejudice toward gays and lesbians by adolescents. Journal of Homosexuality. 1998;36(1):89–100. doi: 10.1300/J082v36n01_06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craig WM, Pepler D, Connolly J, Henderson K. In: Peer harassment in school: The plight of the vulnerable and victimized. Juvonen J, Graham S, editors. New York: Guilford; 2001. pp. 242–261. [Google Scholar]

- Duckitt J. Differential effects of right wing authoritarianism and social dominance orientation on outgroup attitudes and their mediation by threat from and competitiveness to outgroups. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2006;32:684–696. doi: 10.1177/0146167205284282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duckitt J, Sibley CG. Right wing authoritarianism, social dominance orientation and the dimensions of generalized prejudice. European Journal of Personality. 2007;21(2):113–130. [Google Scholar]

- Eidelman S, Biernat M. Derogating black sheep: Individual or group protection? Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 2003;39:602–609. [Google Scholar]

- Erikson E. Identity: Youth and crisis. New York: W. W. Norton; 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Fishbein HD. Peer prejudice and discrimination: Evolutionary, cultural, and developmental dynamics. Boulder, CO: Westview; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Guimond S, Dambrun M, Michinov N, Duarte S. Does social dominance generate prejudice? Integrating individual and contextual determinants of intergroup cognition. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2003;84:697–721. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.84.4.697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herek GM. Heterosexuals’ attitudes toward lesbians and gay men: Correlates and gender differences. Journal of Sex Research. 1988;25:451–477. [Google Scholar]

- Herek GM. Assessing heterosexuals’ attitudes toward lesbians and gay men: A review of empirical research with the ATLG scale. In: Greene B, Herek GM, editors. Lesbian and gay psychology: Theory, research and clinical applications. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1994. pp. 207–225. [Google Scholar]

- Herek GM. Sexual prejudice and gender: Do heterosexuals attitudes toward lesbians and gay men differ? Journal of Social Issues. 2000;56:251–266. [Google Scholar]

- Herek GM, Capitanio JP. Some of my best friends: Intergroup contact, concealable stigma, and heterosexuals’ attitudes toward gay men and lesbians. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 1996;22:412–424. [Google Scholar]

- Hill JP, Lynch ME. The intensification of gender-related role expectations during early adolescence. In: Brooks-Gunn J, Petersen A, editors. Girls at puberty: Biological and psychosocial perspectives. New York: Plenum; 1983. pp. 201–228. [Google Scholar]

- Horn S. Heterosexual adolescents’ and young adults beliefs and attitudes about homosexuality and gay and lesbian peers. Cognitive Development. 2006;21:420–440. [Google Scholar]

- Horn S. Adolescents’ acceptance of same-sex peers based on sexual orientation and gender expression. Journal Youth and Adolescence. 2007;36:363–371. doi: 10.1007/s10964-006-9111-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horn S. The multifaceted nature of sexual prejudice. In: Levy S, Killen M, editors. Intergroup attitudes and relations in childhood through adulthood. New York: Oxford University Press; 2008. pp. 173–188. [Google Scholar]

- Horn S, Nucci LP. The multidimensionality of adolescents’ beliefs about and attitudes toward gay and lesbian peers in school. Equity and Excellence. 2003;36:1–12. [Special issue on LGBTQ issues in K-12 schools] [Google Scholar]

- Huberty CJ, Olejnik S. Applied MANOVA and Discriminant Analysis. New York: Wiley Interscience; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Kite ME, Whitley BE. Sex differences in attitudes toward homosexuals persons, behaviors and civil right: A meta-analysis. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 1996;22:336–353. [Google Scholar]

- Kosciw JG, Diaz EM, Greytak EA. 2007 National School Climate Survey: The experiences of lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender youth in our nation’s schools. New York: GLSEN; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Larsen KS, Reed M, Hoffman S. Attitudes of heterosexuals toward homosexuality: A Likert-type scale and constructive validity. Journal of Sex Research. 1980;16:245–257. [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Schneider JL, Bennett DA. Estimation of the mediation effect with a binary mediator. Statistics in Medicine. 2007;26:3398–3414. doi: 10.1002/sim.2730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mallet P, Apostolidis T, Paty B. The development of gender schemata about heterosexual and homosexual others during adolescence. Journal of General Psychology. 1997;124(1):91–104. doi: 10.1080/00221309709595509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsiglio W. Attitudes toward homosexual activity and gays as friends: A national survey of heterosexual 15- to 19-year-old males. Journal of Sex Research. 1993;30(1):12–17. [Google Scholar]

- Molina L, Wittig MA. Relative importance of contact conditions in explaining prejudice reduction in a classroom context: Separate and unequal? Journal of Social Issues. 2006;62:489–509. [Google Scholar]

- Pleck JH, Sonenstein FL, Ku LC. Attitudes toward male roles among adolescent males: A discriminant validity analysis. Sex Roles. 1994;30:481–501. [Google Scholar]

- Poteat VP, Espelage DL. Predicting psychosocial consequences of homophobic victimization in middle school students. Journal of Early Adolescence. 2007;27:175–191. [Google Scholar]

- Poteat VP, Espelage DL, Green HD., Jr. The socialization of dominance: Peer group contextual effects on homophobic and dominance attitudes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2007;92:1040–1050. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.92.6.1040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pratto F, Stallworth LM, Sidanius J. The gender gap: Differences in political attitudes and social dominance orientation. British Journal of Social Psychology. 1997;36:49–68. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8309.1997.tb01118.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods. 2008;40:879–891. doi: 10.3758/brm.40.3.879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaffer DR. Developmental psychology: Childhood and adolescence. 5th ed. Pacific Grove, CA: Brooks/Cole; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Sidanius J, Pratto F. Social dominance. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Van de Ven P. Comparisons among homophobic reaction of undergraduates, high school students, and young offenders. Journal of Sex Research. 1994;31(2):117–124. [Google Scholar]

- Ward D. Generations and the expression of symbolic racism. Political Psychology. 1985;6:1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Whitehead KA, Hinze M, Futrell MJ. Heterosexist discourse among U.S. adolescents: A comparison of talk about race and sexuality. Northridge: California State University; 2004. Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Whitley BE. The relationship of heterosexuals’ attributions for causes of homosexuality to attitudes toward lesbians and gay men. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 1990;16:369–377. [Google Scholar]

- Whitley BE. Right-wing authoritarianism, social dominance orientation and prejudice. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1999;77:126–134. [Google Scholar]

- Whitley BE, Ægisdóttir S. The gender belief system, authoritarianism, social dominance orientation, and heterosexuals’ attitudes toward lesbians and gay men. Sex Roles. 2000;42:947–967. [Google Scholar]