Abstract

Study Design

Prospective randomized and observational cohorts.

Objective

To compare outcomes of patients with and without workers' compensation who had surgical and nonoperative treatment for a lumbar intervertebral disc herniation (IDH).

Summary of Background Data

Few studies have examined the association between worker's compensation and outcomes of surgical and nonoperative treatment.

Methods

Patients with at least 6 weeks of sciatica and a lumbar IDH were enrolled in either a randomized trial or observational cohort at 13 US spine centers. Patients were categorized as workers' compensation or nonworkers' compensation based on baseline disability compensation and work status. Treatment was usual nonoperative care or surgical discectomy. Outcomes included pain, functional impairment, satisfaction and work/disability status at 6 weeks, 3, 6, 12, and 24 months.

Results

Combining randomized and observational cohorts, 113 patients with workers' compensation and 811 patients without were followed for 2 years. There were significant improvements in pain, function, and satisfaction with both surgical and nonoperative treatment in both groups. In the nonworkers' compensation group, there was a clinically and statistically significant advantage for surgery at 3 months that remained significant at 2 years. However, in the workers' compensation group, the benefit of surgery diminished with time; at 2 years no significant advantage was seen for surgery in any outcome (treatment difference for SF-36 bodily pain [−5.9; 95% CI: −16.7–4.9] and physical function [5.0; 95% CI: −4.9–15]). Surgical treatment was not associated with better work or disability outcomes in either group.

Conclusion

Patients with a lumbar IDH improved substantially with both surgical and nonoperative treatment. However, there was no added benefit associated with surgical treatment for patients with workers' compensation at 2 years while those in the nonworkers' compensation group had significantly greater improvement with surgical treatment.

Keywords: workers' compensation, disability, lumbar disc herniation, sciatica, outcomes, treatment, predictors, SPORT

Musculoskeletal symptoms are an important cause of work loss and are currently the second most important reason for eligibility in the Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI) program, where low back pain is the most common musculoskeletal diagnosis.1 Outcomes in patients with work-related musculoskeletal disorders, including those with a workers' compensation claim, appear to be significantly worse.2–4 Thus, understanding how workers' compensation affects outcomes among various treatments is important in order to advise patients, physicians, and employers, and to identify opportunities for improvement.

A lumbar intervertebral disc herniation is a common, disabling condition in working adults and coverage by workers' compensation insurance has been reported in over a third of patients treated for a disc herniation.5 Several studies have identified differences in outcome between patients with a disc herniation with and without workers' compensation.2 Problems with prior studies include inconsistent diagnostic criteria and clinical measures, limited subjective outcomes assessment, inadequate follow-up, and no follow-up of nonoperative patients.6–10

Using patients with sciatica due to a herniated disc enrolled in the Spine Patient Outcomes Research Trial (SPORT), our primary goal was to determine whether there were significant differences among various outcomes over time for those with and without workers' compensation.

Materials and Methods

Study Design and Interventions

Details of the design of SPORT and outcomes of patients with a lumbar intervertebral disc herniation at 2 year follow-up have been previously published.11–14 The study was conducted in 11 states at 13 US medical centers with multidisciplinary spine practices. Patients were enrolled between 2000 and 2005 in either a randomized cohort or, for those who declined randomization, a concurrent observational cohort. Patients randomized or choosing surgery underwent a standard open discectomy.14 The non-operative treatment protocol was “usual care” and recommended at least: active physical therapy, education or counseling with home exercise instruction and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. All patients provided written informed consent at the time of study enrollment, and all study activities were approved by institutional review boards.

Patient Population

All patients had symptoms and signs of lumbar radiculopathy for at least 6 weeks, confirmatory imaging, and were considered surgical candidates. Exclusion criteria restricted enrollment to patients without prior spine surgery for whom surgery was deemed elective.11

Disability Compensation Status at Baseline

Eligible, enrolled patients were classified according to self-reported disability compensation status.12 Patients who reported receiving SSDI at enrollment were excluded since this generally indicates permanent disability without expected return to the workforce.15 Patients were classified as having workers' compensation if they reported an approved or pending claim based on a previously validated algorithm.7,16 A comparison group of patients without workers' compensation or other disability compensation included those currently working, not working because of back problems or unemployed (since those unemployed could return to work after finding a new job). Patients who reported they were retired, disabled from another condition, were a homemaker or student, or did not report their employment status were excluded.

Study Measures

Patients completed surveys at enrollment and follow-up at 6 weeks, 3, 6, 12, and 24 months. Primary outcomes included; self-reported measures of bodily pain and physical function (SF-36),17,18 and modified Oswestry Disability Index.19 SF-36 scores range from 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating less severe symptoms. The Oswestry Disability Index ranges from 0 to 100, with lower scores indicating less severe symptoms.

Other outcomes included patient-reported improvement, satisfaction with current symptoms; work and disability compensation status; and bothersomeness of sciatica.5,20 Patients reporting current full or part-time employment were considered working. Disability compensation was considered to be an active issue if the patient reported receiving workers' compensation, SSDI (new since enrollment), or other disability compensation, or had an application pending or under appeal. Nonoperative treatments, surgical procedures, complications and repeat surgeries were reported.

Statistical Analysis

Initial analyses compared the baseline characteristics of surgical and nonoperative patients with and without workers' compensation. Outcome analyses compared surgical and nonoperative treatments among workers' compensation and nonworkers' compensation groups using change from baseline at each follow-up with a longitudinal mixed effects model that included a random individual effect to account for correlation between repeated measurements.

Because of crossover among patients randomized to surgical and nonoperative treatment, all analyses were based on treatments actually received. The treatment indicator was a time-varying covariate, allowing for variable times of surgery. The time reference for treatment effects was from the beginning of treatment (i.e., the time of surgery for the surgical group and the time of enrollment for the nonoperative group). Before surgery, all changes from baseline surgery were included in the estimates of the nonoperative treatment effect. After surgery, changes were assigned to the surgical group, with follow-up measured from the date of surgery. To compare treatment effects between groups, interaction terms were included for treatment, workers' compensation, and survey time. Because patients with a longer duration of symptoms or longer time from enrollment to surgery may have different outcomes, a subgroup analysis was performed limiting patients to those with a short current episode duration (less than 6 months) and, for surgically treated patients, time from enrollment to surgery (less than 3 months).

To adjust for potential confounding effects, baseline variables associated with missing data, treatment received, and baseline workers' compensation status were included as covariates in the longitudinal regression models.21 To adjust for possible confounding of the workers' compensation comparisons, a propensity score that was created from the predicted probability of receiving workers' compensation from a logistic regression model using baseline patient characteristics.22 This score was included as a covariate.

Computations were performed with the use of the PROC MIXED procedure for continuous data and the PROC GENMOD procedure for binary and non-normal secondary outcomes in SAS software, version 9.1 (SAS Institute). Statistical significance was defined as P < 0.05 on the basis of a 2-sided hypothesis test with no adjustments made for multiple comparisons. Data for these analyses were collected through May 8, 2008.

Results

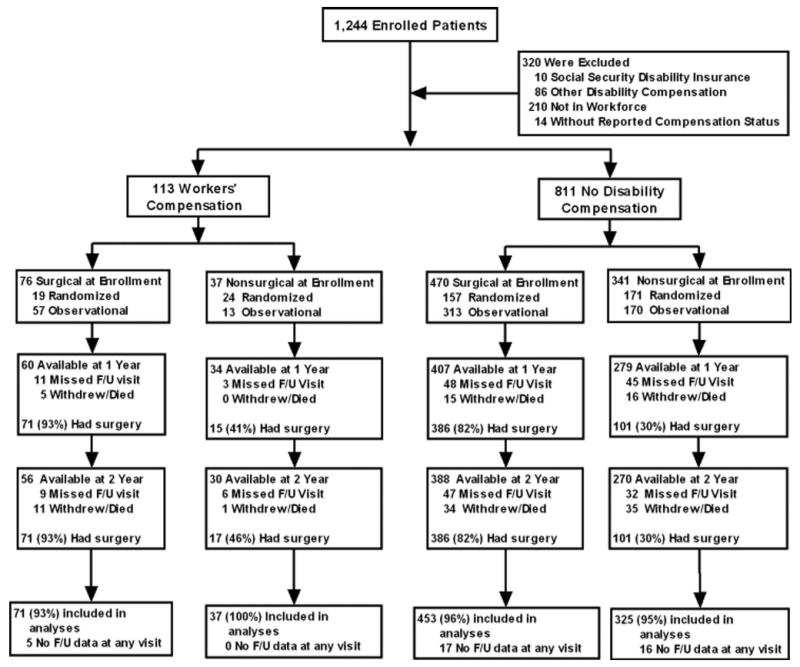

A total of 1244 eligible patients were enrolled: 501 in the randomized cohort and 743 in the observational cohort (Figure 1). Among 113 patients with workers' compensation at baseline enrollment, 76 (67%) were assigned or initially elected surgical treatment and 37 (33%) were assigned or initially elected nonoperative treatment. Among 811 patients without disability compensation, 470 (58%) were assigned or elected surgical treatment and 341 (42%) were assigned or elected nonoperative treatment. Of those assigned or electing surgical treatment at enrollment, more patients in the workers' compensation group had undergone surgery at 6 weeks (84% vs. 70%, respectively, P = 0.01) and at 2 years (93% vs. 82%, respectively, P = 0.01). Similarly, in those assigned or electing nonoperative treatment more patients in the workers' compensation group had undergone surgery at 2 years (46% vs. 31%, respectively, P = 0.06).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of enrollment and follow-up. The numbers of patients who completed follow-up or underwent surgery are cumulative during the 2-year follow-up period.

The proportion of patients who supplied data at each follow-up interval ranged from 74% to 92% with losses due to missed visits, dropouts or death. A total of 886 patients, each with at least one follow-up through 2 years were included in the analysis; 108 patients (96%) with workers' compensation and 778 (96%) without (Figure 1).

Characteristics of the Patients

Overall, among patients in the workers' compensation or nonworkers' compensation groups, those surgically and nonoperatively treated were similar (Table 1). However, surgical patients were younger than nonoperatively treated patients in the compensation group (36.9 vs. 41 years, P = 0.04), and were more likely to have missed work in the noncompensation group (27% vs. 20%, P = 0.04). Surgical patients had more findings on physical examination and imaging, and reported more severe symptoms and functional impairment than nonoperatively treated patients regardless of compensation. However, differences in functional impairment among surgical and nonoperative patients were more pronounced for those without workers' compensation, although this may be the consequence of the greater baseline severity of all patients with workers compensation (SF-36 physical function, workers' compensation 37.5 vs. nonworkers' compensation 51.5, P < 0.006).

Table 1. Patient Baseline Characteristics and Clinical Findings by Baseline Workers' Compensation Status*.

| Workers' Compensation | Nonworkers' Compensation | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable–No. (%) | Surgery (n = 80) |

Nonoperative (n = 28) |

P | Surgery (n = 459) |

Nonoperative (n = 319) |

P | WC vs. Non-WC P |

| Demographics | |||||||

| Age, mean (yr) | 36.9 (8.3) | 41 (10.4) | 0.039 | 40.7 (9.8) | 41 (10.2) | 0.66 | 0.004 |

| Female | 18 (22%) | 5 (18%) | 0.80 | 197 (43%) | 130 (41%) | 0.60 | <0.001 |

| Race or ethnic background† | |||||||

| Non-Hispanic | 72 (90%) | 26 (93%) | 0.94 | 441 (96%) | 308 (97%) | 0.88 | 0.018 |

| White | 62 (78%) | 20 (71%) | 0.70 | 410 (89%) | 279 (87%) | 0.49 | <0.001 |

| Education–at least some college | 41 (51%) | 16 (57%) | 0.75 | 368 (80%) | 262 (82%) | 0.55 | <0.001 |

| Income–under $50,000 | 47 (59%) | 17 (61%) | 0.97 | 212 (46%) | 154 (48%) | 0.62 | 0.023 |

| Marital status–married | 52 (65%) | 21 (75%) | 0.46 | 324 (71%) | 219 (69%) | 0.62 | 0.72 |

| Prior history | |||||||

| Smoker | 32 (40%) | 8 (29%) | 0.40 | 94 (20%) | 68 (21%) | 0.85 | <0.001 |

| Any medical problem | 15 (19%) | 8 (29%) | 0.41 | 157 (34%) | 110 (34%) | 1 | 0.01 |

| Bone or joint problem | 9 (11%) | 5 (18%) | 0.57 | 72 (16%) | 68 (21%) | 0.055 | 0.25 |

| Duration of spine problems: ≤1 yr | 47 (59%) | 16 (57%) | 0.94 | 201 (44%) | 147 (46%) | 0.58 | 0.011 |

| Duration of current episode: <3 mo | 33 (41%) | 15 (54%) | 0.36 | 155 (34%) | 122 (38%) | 0.23 | 0.093 |

| Work status | |||||||

| Usual work hours: ≥40 | 63 (79%) | 19 (68%) | 0.37 | 358 (78%) | 246 (77%) | 0.84 | 0.78 |

| Missed work in past month | 52 (65%) | 23 (82%) | 0.15 | 122 (27%) | 64 (20%) | 0.044 | <0.001 |

| Lifting weight: not important | 7 (9%) | 4 (14%) | 0.64 | 222 (48%) | 159 (50%) | 0.74 | <0.001 |

| Prefer fewer hours with less pay | 6 (8%) | 6 (21%) | 0.095 | 78 (17%) | 40 (13%) | 0.11 | 0.33 |

| Legal action: yes | 19 (24%) | 7 (25%) | 0.90 | 11 (2%) | 10 (3%) | 0.69 | <0.001 |

| Clinical findings | |||||||

| Straight leg raise test: ipsilateral | 51 (64%) | 19 (68%) | 0.87 | 307 (67%) | 188 (59%) | 0.028 | 0.89 |

| Any neurologic deficit | 67 (84%) | 20 (71%) | 0.25 | 358 (78%) | 227 (71%) | 0.037 | 0.27 |

| Reflexes: asymmetrical depressed | 29 (36%) | 6 (21%) | 0.23 | 200 (44%) | 124 (39%) | 0.22 | 0.084 |

| Sensory: asymmetrical decrease | 52 (65%) | 14 (50%) | 0.24 | 256 (56%) | 140 (44%) | 0.001 | 0.059 |

| Motor: asymmetrical weakness | 44 (55%) | 12 (43%) | 0.38 | 201 (44%) | 114 (36%) | 0.03 | 0.032 |

| Herniation type | 0.52 | 0.01 | 0.92 | ||||

| Protruding | 23 (29%) | 8 (29%) | — | 110 (24%) | 101 (32%) | — | |

| Extruded | 53 (66%) | 16 (57%) | — | 324 (71%) | 192 (60%) | — | |

| Sequestered | 4 (5%) | 3 (11%) | — | 25 (5%) | 26 (8%) | — | |

| SF-36 score‡ | |||||||

| Bodily pain (BP) | 19.3 (16) | 23.2 (13.3) | 0.26 | 24.1 (16.3) | 34.5 (19.8) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Physical functioning (PF) | 27.3 (20.1) | 37.5 (22.8) | 0.028 | 34 (23.3) | 51.5 (26) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| General health (GH) | 64.9 (18.2) | 68.5 (18.8) | 0.37 | 73.7 (17.9) | 71.5 (18.1) | 0.10 | <0.001 |

| Mental health (MH) | 54.4 (20) | 54.4 (21) | 0.99 | 64.3 (18.8) | 66.8 (19.6) | 0.074 | <0.001 |

| Vitality (VT) | 34.3 (15.8) | 40.2 (16.7) | 0.099 | 37 (19.7) | 43 (20.8) | <0.001 | 0.076 |

| Oswestry disability index§ | 60.2 (17) | 50.1 (19.4) | 0.011 | 53.1 (19.3) | 36.7 (19.9) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Sciatica bothersomeness index¶ | 17 (4.9) | 14.1 (5.5) | 0.01 | 16.5 (4.9) | 13.9 (5.5) | <0.001 | 0.13 |

| Satisfaction with symptoms: very dissatisfied | 72 (90%) | 22 (79%) | 0.22 | 402 (88%) | 202 (63%) | <0.001 | 0.035 |

| Problem getting better or worse | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.26 | ||||

| Getting better | 2 (2%) | 9 (32%) | — | 41 (9%) | 84 (26%) | — | |

| Staying about the same | 38 (48%) | 14 (50%) | — | 196 (43%) | 158 (50%) | — | |

| Getting worse | 40 (50%) | 5 (18%) | — | 218 (47%) | 75 (24%) | — | |

Patients in workers' compensation or nonworkers' compensation groups were classified according to whether they received surgical or nonoperative treatment during the first 6 mo after enrollment. Numbers of patients include only those who completed at least one follow-up survey within 2 yr after enrollment.

Race or ethnic group was self-reported. Whites and blacks could be either Hispanic or non-Hispanic.

Scores on the Medical Outcomes Study 36-item Short-Form General Health Survey (SF-36) range from 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating less severe symptoms.

The Oswestry Disability Index ranges from 0 to 100, with lower scores indicating less severe symptoms.

The Sciatica Bothersomeness Index ranges from 0 to 24, with lower scores indicating less severe symptoms.

In contrast to similar characteristics among surgical and nonoperative patients within workers' compensation groups, there were significant differences comparing patients across workers' compensation groups (Table 1). Patients in the workers' compensation group were significantly younger, less likely to be non-Hispanic whites and well-educated; more likely to be male, cigarette smokers and report lower income levels. Work status also differed by compensation status. Patients in the workers' compensation group were more likely to have missed work in the past month, require lifting as part of usual activities, and be involved in legal action with an attorney. Though there were few differences in physical examination and imaging findings among patients in workers' compensation or nonworkers' compensation groups, the patients in the workers' compensation group reported greater impairment in symptoms, function, and less satisfaction with current symptoms.

Treatments Received and Surgical Complications

Over 2 years, treatments received and surgical complications were similar among those in the workers' compensation and nonworkers' compensation groups (Table 2). However, patients with compensation were significantly more likely to receive narcotics (59% vs. 37%, P = 0.013) and muscle relaxants (41% vs. 19%, P = 0.005). Operative time was longer among those in the workers' compensation group (84.2 vs. 75.0 minutes, P = 0.023). At 2 years, there was no difference between groups in rates of reoperation (7%).

Table 2. Nonoperative Treatments and Surgical Complications and Events by Baseline Workers' Compensation Status*.

| Nonoperative Treatments | Worker's Compensation (n = 37) |

Nonworker's Compensation (n = 379) |

P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Clinician services | |||

| Education/counseling | 33 (89%) | 350 (92%) | 0.72 |

| Emergency room visits | 10 (27%) | 53 (14%) | 0.061 |

| Surgeon | 16 (43%) | 125 (33%) | 0.28 |

| Chiropractor | 9 (24%) | 50 (13%) | 0.11 |

| Internist/neurologist/etc | 25 (68%) | 227 (60%) | 0.46 |

| Physical therapist | 21 (57%) | 153 (40%) | 0.079 |

| Injections | 18 (49%) | 182 (48%) | 0.92 |

| Medication use | |||

| NSAIDS† | 25 (68%) | 237 (63%) | 0.67 |

| Cox-2 inhibitors† | 14 (38%) | 124 (33%) | 0.65 |

| Narcotics | 22 (59%) | 141 (37%) | 0.013 |

| Muscle relaxants | 15 (41%) | 73 (19%) | 0.005 |

| Devices: none | 9 (69%) | 88 (81%) | 0.50 |

| Surgical Treatment | Worker's Compensation (n = 87) |

Nonworker's Compensation (n = 488) |

|

| Operation time | 84.2 (32.3) | 75 (35.3) | 0.023 |

| Blood loss | 78.7 (75.3) | 60.5 (93.3) | 0.086 |

| Intraoperative blood replacement | 0 (0%) | 6 (1%) | 0.64 |

| Intraoperative complications | |||

| None‡ | 84 (97%) | 473 (97%) | 0.88 |

| Postoperative complications | |||

| None§ | 84 (97%) | 456 (94%) | 0.49 |

| Reoperation within 2 yr¶ | 6 (7%) | 35 (7%) | 0.9 |

Patients who had used clinicians, treatments, medications, and devices within 2 yr following enrollment or until the time of surgery. Patients either had no surgery in the first 2 yr from enrollment or had at least one regularly scheduled follow-up visit prior to surgery at which nonoperative treatment information was assessed.

Cox-2 indicates cyclooxygenase 2; NSAID, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

Any reported intraoperative complication.

Any reported postoperative complications up to 8 wk postoperation.

Any additional spine surgery over 2 yr. Rates of repeated surgery are Kaplan-Meier estimates. P values were calculated with the use of the log-rank test.

Main Treatment Effects by Workers' Compensation Groups

A significant treatment effect favoring surgery was seen at 6 weeks and 3 months regardless of baseline workers' compensation status for the primary outcomes at 3 months: SF-36 bodily pain (workers' compensation, 11.8 vs. no workers' compensation, 17.8, P = 0.18), SF-36 physical function (workers' compensation, 12.4 vs. no workers' compensation, 18.1, P = 0.17), or Oswestry Disability Index (workers' compensation, −9.4 vs. no workers' compensation, −16.1, P = 0.054). From the 6-month follow-up through 2 years, the relative benefit of surgery among patients with workers' compensation diminished, while it persisted among those patients in the noncompensation group. At 2 years, there were no significant treatment differences for patients in the workers' compensation group; SF-36 bodily pain (−5.9; 95% CI: −16.7–4.9), SF-36 physical function (5.0; 95% CI: −4.9–15), or Oswestry Disability Index (−2; 95% CI: −10.3–6.3). This result was in contrast to the nonworkers' compensation group who demonstrated surgical benefit at 2 years; SF-36 bodily pain (11.0 vs. −5.9, P = 0.003), SF-36 physical function (13.4 vs. 5, P = 0.11), and Oswestry Disability Index (−12.5 vs. −2, P = 0.018) (Table 3).

Table 3. Adjusted Analyses According to Treatment Received for the Baseline Workers' Compensation and Nonworkers' Compensation Groups*.

| Treatment Effect (95% CI)† | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome Scale | WC Status | At 6 wk | At 3 mo | At 6 mo | At 1 yr | At 2 yr |

| SF-36 bodily pain‡ | Non-WC | 10.8 (8.0–13.5) | 17.8 (14.7–21) | 15.7 (12.4–19) | 12.2 (8.9–15.5) | 11 (7.7–14.4) |

| WC | 10.8 (3.1–18.5) | 11.8 (3.5–20.1) | 7.3 (−1.7–16.3) | 2.2 (−7.7–12.2) | −5.9 (−16.7–4.9) | |

| P | 0.99 | 0.18 | 0.086 | 0.06 | 0.003 | |

| SF-36 physical function‡ | Non-WC | 13.8 (11.2–16.4) | 18.1 (15.1–21.1) | 19. (16–22.3) | 16.4 (13.3–19.5) | 13.4 (10.3–16.5) |

| WC | 10.9 (3.8–18) | 12.4 (4.7–20.1) | 5.3 (−3–13.6) | 5 (−4.2–14.2) | 5 (−4.9–15) | |

| P | 0.45 | 0.17 | 0.002 | 0.02 | 0.11 | |

| Oswestry disability index§ | Non-WC | −15.5 (−17.6 to −13.3) | −16.1 (−18.5 to −13.6) | − 15.6 (−18.2 to −13) | −14.4 (−17 to −11.8) | −12.5 (− 15.2 to −9.9) |

| WC | −11.3 (−17.3 to −5.4) | −9.4(−15.8 to −2.9) | −4.8 (−11.8–2.2) | −2.2 (−9.9–5.5) | −2(−10.3–6.3) | |

| P | 0.20 | 0.054 | 0.004 | 0.003 | 0.018 | |

| Sciatica bothersomeness index¶ | Non-WC | NA | −4.6(−5.5 to −3.8) | NA | −3 (−3.8 to −2.1) | −2.6 (−3.5 to −1.8) |

| WC | NA | −2.6 (−4.8 to −0.4) | NA | −0.5 (−3–2) | 0.2 (−2.5–3) | |

| P | 0.084 | 0.067 | 0.049 | |||

| Satisfaction with symptoms (very/somewhat satisfied) | Non-WC | 48.3 (42.5–54.2) | 41.6 (34.5–48.7) | 35.8 (28.2–43.4) | 30.2 (22.4–38) | 22.5 (14.6–30.4) |

| WC | 42.6 (25.4–59.7) | 20.1 (−0.6–40.7) | 30.3 (8.7–51.9) | −6.5 (−32–19.1) | −3.6 (−31.7–24.5) | |

| P | 0.89 | 0.13 | 0.75 | 0.01 | 0.13 | |

| Self-rated improvement (major improvement) | Non-WC | 52 (46.2–57.7) | 39.7 (32.7–46.7) | 32.4 (25.1–39.7) | 24.5 (17.1–31.9) | 11 (3.5–18.5) |

| WC | 43.7 (26.9–60.5) | 31.8 (11.5–52) | 15.8 (−7.3–38.9) | 28.4 (3.9–52.9) | 17.4 (−9.9–44.8) | |

| P | 0.24 | 0.17 | 0.041 | 0.85 | 0.82 | |

| Working (full or part-time) | Non-WC | −20.8 (−26.8 to −14.9) | −3.4 (−8.4–1.6) | −0.5 (−4.3–3.3) | 1.9 (−2.2–6) | 0.8 (−3.4–5) |

| WC | −35.1 (−59.6 to −10.7) | −17.4 (−39.1–4.3) | −2.4 (−21.4–16.6) | 13.3 (−9–35.6) | 7.7 (−14.6–30.1) | |

| P | 0.67 | 0.47 | 0.93 | 0.41 | 0.63 | |

| Disability compensation (receiving, pending appeal) | Non-WC | 1.5 (0.4–2.7) | 0.2 (−1–1.3) | 0.2 (−1.1–1.6) | 0 (−1.3–1.4) | |

| WC | NA | 11 (−3.1–25.1) | 15.4 (−0.9–31.7) | −17 (−47.7–13.7) | −14.7 (−43–13.6) | |

| P | 0.44 | 0.19 | 0.25 | 0.29 | ||

Values have been adjusted for WC propensity score, age, gender, ethnicity, marriage status, work status, insurance coverage, compensation status, BMI, smoking status, presence or absence of joint disorders or migraine, any neurologic deficit, herniation results (type, location, level), baseline sciatica bothersomeness score, baseline outcome score, baseline satisfaction score, self-rated health trend, and center. Variables included in the WC propensity score include: cohort (randomized/observational), gender, physical importance of lifting weight, preferred to work fewer hours, occupation, expectations of returning to work with nonoperative treatment, depleted financial resources, duration of spine problems, SF-36 social function subscale score. NA denotes not available and WC denotes workers compensation.

The treatment effect is the difference in the mean change from baseline between the surgical group and the non-operative group.

The SF-36 scores range from 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating less severe symptoms.

The Oswestry Disability Index ranges from 0 to 100, with lower scores indicating less severe symptoms.

The Sciatica Bothersomeness Index ranges from 0 to 24, with lower scores indicating less severe symptoms.

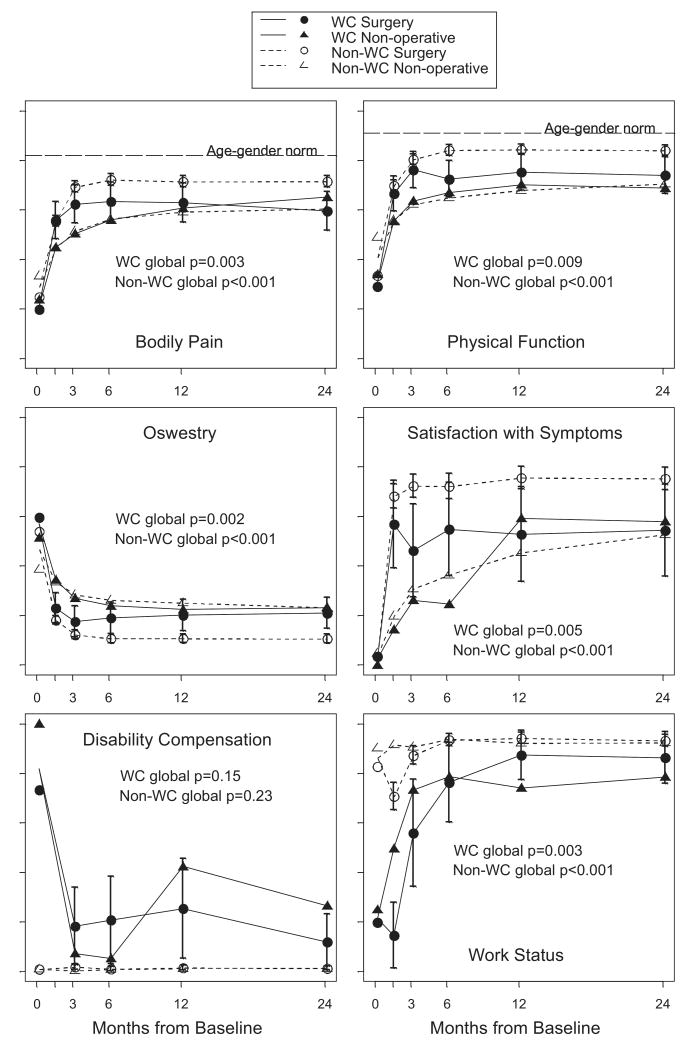

Regardless of baseline workers' compensation status or treatment received patients improved substantially over 2 years (Figure 2). Patients treated nonoperatively reported similar pain, function and satisfaction over time regardless of workers' compensation status. Early treatment effect favoring surgery for patients in the compensation group diminished over time. Similar results were seen for; sciatica bothersomeness, satisfaction with symptoms and self-rated improvement (Table 3 and Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Outcomes of surgical treatment and nonoperative treatment in the workers' compensation and nonworkers' compensation groups during 2 years of follow-up. The graphs show adjusted as-treated analyses. Results for bodily pain and physical function are scores on the Medical Outcomes Study 36-item Short-Form General Health Survey (SF-36), ranging from 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating less severe symptoms. The Oswestry Disability Index ranges from 0 to 100, with lower scores indicating less severe symptoms. The horizontal dashed line in each of the two SF-36 graphs represents normal values adjusted for age and sex. The I bars represent 95% confidence intervals for the surgical groups, and the P values represent a global (area under the curve) comparison of surgical versus nonoperative treatment for workers' compensation and nonworkers' compensation groups. At 0 months, the floating data points represent the observed mean scores or proportions for each study group, whereas the data points on plot lines represent the adjusted mean scores from as-treated analyses.

The short-term treatment benefit for patients in the workers' compensation group and a treatment benefit through 2 years for patients in the nonworkers' compensation group did not translate into higher rates of employment or fewer disability applications among surgically treated patients. At 2 years, no significant treatment differences in work status were seen between the workers' compensation group (7.7; 95% CI: −14.6–30.1) or nonworkers' compensation groups (0.8; 95% CI: −3.4–5.0). Similarly, surgical treatment was not associated with lower rates of disability applications in either group (Table 3 and Figure 2).

Patients with Shorter Symptom Duration

Among patients surgically treated, 58 of 80 patients (72.5%) with workers' compensation and 320 of 459 patients (69.7%) without workers' compensation had symptoms for less than 6 months and underwent surgery within 3 months of enrollment. Similarly, among patients treated nonoperatively over 2 years, 17 of 28 patients (60.7%) with workers' compensation and 227 of 319 (71.2%) without workers' compensation had symptoms for less than 6 months. Though the smaller sample size resulted in few statistically significant differences comparing workers' compensation and nonworkers' compensation groups (Table 4), results were similar to the full study population. In contrast to nonworkers' compensation patients where surgery was associated with improved outcomes over 2 years, patients with workers' compensation had a short-term benefit of surgery compared to nonoperative treatment, but that benefit diminished over time.

Table 4. Adjusted Analyses According to Treatment Received for the Baseline Workers' Compensation and Nonworkers' Compensation Groups among Patients with Shorter Symptom Duration*.

| Treatment Effect (95% CI)† | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome Scale | WC Status | At 6 wk | At 3 mo | At 6 mo | At 1 yr | At 2 yr |

| SF-36 bodily pain‡ | Non-WC | 9.2 (5.7–12.6) | 13.6 (9.5–17.7) | 10.6 (6.5–14.7) | 9.7 (5.7–13.7) | 8.5 (4.5–12.5) |

| WC | 11.3 (1.1–21.4) | 10.2 (−1.4–21.8) | 6.1 (−6–18.2) | 3.5 (−8.9–15.8) | −8.8 (−21.3–3.7) | |

| P | 0.70 | 0.59 | 0.49 | 0.34 | 0.009 | |

| SF-36 physical function‡ | Non-WC | 13.2 (10–16.4) | 13.8 (10–17.6) | 13.7 (9.9–17.5) | 14 (10.3–17.8) | 11 (7.3–14.7) |

| WC | 10.3 (1.1–19.6) | 11.4 (0.7–22) | 5.3 (−5.9–16.4) | 3.1 (−8.2–14.5) | 1.9 (−9.6–13.4) | |

| P | 0.57 | 0.66 | 0.16 | 0.07 | 0.14 | |

| Oswestry disability index§ | Non-WC | −13.6 (− 16.2 to −11) | −12.6 (−15.8 to −9.5) | −10.9 (−14.1 to −7.8) | −11.2 (− 14.3 to −8.2) | −9.6 (−12.7 to −6.5) |

| WC | −11.3 (−23 to −7.8) | − 11.9 (−20.7 to −3.1) | −7 (−16.2 to 2.2) | −3 (−12.4 to 6.3) | −1.7 (−11.2 to 7.8) | |

| P | 0.66 | 0.87 | 0.43 | 0.098 | 0.12 | |

Includes patients with current episode duration of less than 6 mo and, for surgically treated patients, time from enrollment to surgery of less than 3 mo. Values have been adjusted for same variables and WC propensity score variable same as listed in Table 3. WC denotes workers compensation.

The treatment effect is the difference in the mean change from baseline between the surgical group and the nonoperative group.

The SF-36 scores range from 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating less severe symptoms.

The Oswestry Disability Index ranges from 0 to 100, with lower scores indicating less severe symptoms.

Discussion

Patients with a lumbar intervertebral disc herniation reported substantial improvement in pain, physical function, and satisfaction with symptoms over 2 years regardless of workers' compensation status or treatment received. In the nonworkers' compensation group, there was a statistically significant advantage for surgery at 3 months that persisted at 2 years. In contrast, in the workers' compensation group, a short-term benefit of surgery at 3 months diminished over time so that there was no advantage for surgery at 2 years.

Prior studies report that disability compensation is associated with worse outcomes,2,6,23 and among patients with workers' compensation undergoing lumbar discectomy the odds ratio was 4.8 (95% CI: 3.5–6.5) for unsatisfactory outcomes.2 Our results demonstrate that patients with workers' compensation undergoing surgery reported greater improvement with surgical treatment at 6 weeks and 3 months compared with nonoperatively treated patients. However, this treatment difference narrowed over time so that pain, function and satisfaction were similar at 2 years regardless of treatment received. This narrowing of treatment effect over time was due to worsening of outcomes among surgically treated patients in the workers' compensation group.

It is unclear why patients with workers' compensation benefit less from surgical treatment and what accounts for the decrease in surgical benefit over time. A number of clinical and nonclinical factors have been postulated for worse outcomes in patients with workers compensation. Clinical factors include differences in the underlying disease entity and its severity, the presence of other co-morbid conditions, and the treatment received.3,24–26 Nonclinical factors include patient socioeconomic and work-related characteristics, expectations, and preferences3,4,25,27–30 as well as features of the disability system itself.31,32

The study was able to control for many potential clinical and nonclinical factors. We enrolled patients in spine centers across the US with a well-defined, objectively assessed condition, who were prospectively evaluated and treated, systematically assessed for a broad range of outcomes over time, and controlled for variables associated with missing data, treatment received, and baseline workers' compensation status.

Even after controlling for many of these clinical and nonclinical factors, differences in outcomes among workers' compensation groups persisted. We also examined a subgroup of individuals with a short duration of symptoms and found similar findings compared to the full study population. It has been postulated that financial incentives or the adversarial nature of the workers' compensation system may account for worse outcomes.32,33 However, we found no differences by workers' compensation group in 2 year outcomes among nonoperatively treated patients. Nor would one expect to see an early benefit, but not late benefit, of surgery in the workers' compensation group if financial incentives were driving patient-reported outcomes. Another explanation for relative worsening of outcomes over time may be different expectations among workers' compensation patients undergoing surgery.34 A larger percentage of patients with workers' compensation underwent surgery (74% vs. 59% of patients without workers' compensation). Though this may have been due to differences in referral patterns, other factors such as greater work interference, less latitude to wait for natural healing to occur, may lead to higher levels of intervention that are characteristic of the workers' compensation system. The nature of the postoperative treatment may be another potential explanatory factor. Rehabilitation following discectomy has been shown to be beneficial,35 and may be differentially important for those with workers' compensation.9 Additional studies are needed to address the importance of perceptions or expectations among surgically treated patient and the timing and intensity of post-operative rehabilitation among those with workers' compensation.34,35

Though many studies have focused on outcomes of surgical treatment for patients with workers' compensation, few studies have compared surgical and nonoperative treatment outcomes separately for patients with and without workers' compensation. Our results suggest that a more complex view of the association between workers' compensation status and outcomes is necessary. Surgical patients in the workers' compensation group reported worse pain, function and satisfaction at 2 years compared to patients in the nonworkers' compensation group. However, similar outcomes were observed in nonoperative patients in the workers' compensation and nonworkers' compensation groups. Work status at 2 years was also similar among patients regardless of treatment received or baseline workers' compensation status, a result previously noted at 4 and 10 year follow-up in the Maine Lumbar Spine Study.7,36 Though there was no significant difference in applications for or receipt of disability compensation at 2 years among patients in the workers' compensation or nonworkers' compensation groups, longer follow-up in the Maine Lumbar Spine Study demonstrated higher rates of disability compensation among those with a workers' compensation claim at baseline.7,36

The primary limitation of this study was the lack of intention-to-treat analyses based on random treatment assignment for those with workers' compensation or without disability compensation at baseline. Though patients with workers' compensation were equally likely to accept randomization, marked nonadherence to randomized treatment occurred, regardless workers' compensation status. The use of intention-to-treat analysis was also limited because of the relatively small number of patients with workers' compensation who participated in the randomized cohort (n = 43). As expected, patients with more severe symptoms and worsening symptoms were more likely to cross over to surgical treatment. While the as-treated analysis carefully adjusted for baseline covariates associated with both treatment assignment and workers' compensation, it is still more susceptible to selection bias and confounding than intention-to-treat. In addition, the propensity score used to adjust for factors associated workers' compensation status may have been limited by the baseline variables collected in SPORT and may not fully control for differences in factors such as psychosocial and work characteristics.37

Another limitation was that disability compensation status was patient-reported, though prior studies have demonstrated the accuracy of such information.7,16 In our study, patients with workers' compensation included those with pending and approved applications. Most studies from the workers' compensation literature only include those with approved claims, but our definition is more clinically relevant since physicians often evaluate such patients while the claim is pending, and prior analyses show similar results when pending applications are excluded.7,16,36 Finally, the size of the workers' compensation group may lead to failure to report significance of treatment effect when true differences exist.

In conclusion, in as-treated analyses combining randomized and observational cohorts that carefully adjusted for potentially confounding baseline factors, those with workers' compensation showed similar improvement from surgical and nonoperative treatment at 2 years. Those without workers' compensation showed a greater improvement with surgical treatment. Surgical treatment did not improve work or disability outcomes at 2 years compared to nonoperative treatment for patients either with or without compensation. These results do not imply that for 2 patients with similar clinical presentations, examinations and imaging results discectomy should not be offered to a patient with a workers' compensation claim while offered to a patient without such a claim. Rather as recommended in recent guideline recommendations, physicians should discuss the risks and benefits of treatment options including surgery, and that treatment decisions should be based on informed choice using a shared decision-making approach.38–40 For patients considering surgery as a means to facilitate faster return to work, that discussion should include information on relative return to work and disability compensation rates.

Key Points

The study compared outcomes of patients classified by workers' compensation status, using as-treated analyses combining randomized and observational cohorts that adjusted for potentially confounding baseline factors.

Patients with and without workers' compensation improved substantially regardless of treatment received.

In contrast to those in the nonworkers' compensation group who had significantly greater improvement with surgical treatment, those in the workers' compensation group showed similar improvement from surgical and nonoperative treatment at 2 years.

Surgical treatment did not improve work or disability outcomes at 2 years compared to nonoperative treatment for patients either with or without workers' compensation.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Jeffrey M. Ashburner, MPH, for assistance in the preparation of this manuscript.

Federal and institutional funds were received in support of this work. No benefits in any form have been or will be received from a commercial party related directly or indirectly to the subject of this manuscript. The Multidisciplinary Clinical Research Center in Musculoskeletal Diseases is supported by the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskel-etal and Skin Diseases (NIAMS) (P60 AR048094). SPORT (U01-AR45444) was supported by NIAMS, and the Office of Women's Health, the National Institutes of Health, and the National Institute of Occupational Safety and Health, The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

References

- 1.United States Government Accounting Office. Social Security: Disability Programs Lag in Promoting Return to Work. Gaithersburg, MD: US Government Printing Office; 1996. (GAO/HEHS 97–46). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Harris I, Mulford J, Solomon M, et al. Association between compensation status and outcome after surgery: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2005;293:1644–52. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.13.1644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abasolo L, Carmona L, Lajas C, et al. Prognostic factors in short-term disability due to musculoskeletal disorders. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;59:489–96. doi: 10.1002/art.23537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Crook J, Milner R, Schultz IZ, et al. Determinants of occupational disability following a low back injury: a critical review of the literature. J Occup Rehabil. 2002;12:277–95. doi: 10.1023/a:1020278708861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Keller RB, Atlas SJ, Singer DE, et al. The Maine lumbar spine study, Part I. Background and concepts. Spine. 1996;21:1769–76. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199608010-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rohling ML, Binder LM, Langhinrichsen-Rohling J. Money matters: a meta-analytic review of the association between financial compensation and the experience and treatment of chronic pain. Health Psychol. 1995;14:537–47. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.14.6.537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Atlas SJ, Chang Y, Kammann E, et al. Long-term disability and return to work among patients who have a herniated lumbar disc: the effect of disability compensation. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2000;82:4–15. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200001000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.DeBerard MS, LaCaille RA, Spielmans G, et al. Outcomes and presurgery correlates of lumbar discectomy in Utah workers' compensation patients. Spine J. 2009;9:193–203. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2008.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mayer T, McMahon MJ, Gatchel RJ, et al. Socioeconomic outcomes of combined spine surgery and functional restoration in workers' compensation spinal disorders with matched controls. Spine. 1998;23:598–605. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199803010-00013. discussion 606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shvartzman L, Weingarten E, Sherry H, et al. Cost-effectiveness analysis of extended conservative therapy versus surgical intervention in the management of herniated lumbar intervertebral disc. Spine. 1992;17:176–82. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199202000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Birkmeyer NJ, Weinstein JN, Tosteson AN, et al. Design of the Spine Patient Outcomes Research Trial (SPORT) Spine. 2002;27:1361–72. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200206150-00020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cummins J, Lurie JD, Tosteson TD, et al. Descriptive epidemiology and prior healthcare utilization of patients in the Spine Patient Outcomes Research Trial's (SPORT) three observational cohorts: disc herniation, spinal stenosis, and degenerative spondylolisthesis. Spine. 2006;31:806–14. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000207473.09030.0d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Weinstein JN, Lurie JD, Tosteson TD, et al. Surgical vs nonoperative treatment for lumbar disk herniation: the Spine Patient Outcomes Research Trial (SPORT) observational cohort. JAMA. 2006;296:2451–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.20.2451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Weinstein JN, Tosteson TD, Lurie JD, et al. Surgical vs nonoperative treatment for lumbar disk herniation: the Spine Patient Outcomes Research Trial (SPORT): a randomized trial. JAMA. 2006;296:2441–50. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.20.2441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Autor DH, Duggan MG. The growth in the disability insurance roles: a fiscal crisis unfolding. J Econ Perspect. 2006;20:71–96. doi: 10.1257/jep.20.3.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Atlas SJ, Tosteson TD, Hanscom B, et al. What is different about workers' compensation patients? Socioeconomic predictors of baseline disability status among patients with lumbar radiculopathy. Spine. 2007;32:2019–26. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e318133d69b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stewart AL, Greenfield S, Hays RD, et al. Functional status and well-being of patients with chronic conditions. Results from the medical outcomes study. JAMA. 1989;262:907–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ware JE, Jr, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care. 1992;30:473–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fairbank JC, Pynsent PB. The Oswestry disability index. Spine. 2000;25:2940–52. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200011150-00017. discussion 2952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Patrick DL, Deyo RA, Atlas SJ, et al. Assessing health-related quality of life in patients with sciatica. Spine. 1995;20:1899–908. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199509000-00011. discussion 1909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fitzmaurice GM, Laird NM, Ware JH. Applied Longitudinal Analysis. Philadelphia, PA: Wiley-Interscience; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 22.D'Agostino RB., Jr Propensity score methods for bias reduction in the comparison of a treatment to a non-randomized control group. Stat Med. 1998;17:2265–81. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(19981015)17:19<2265::aid-sim918>3.0.co;2-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Binder LM, Rohling ML. Money matters: a meta-analytic review of the effects of financial incentives on recovery after closed-head injury. Am J Psychiatry. 1996;153:7–10. doi: 10.1176/ajp.153.1.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hagen KB, Tambs K, Bjerkedal T. A prospective cohort study of risk factors for disability retirement because of back pain in the general working population. Spine. 2002;27:1790–6. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200208150-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Krause N, Frank JW, Dasinger LK, et al. Determinants of duration of disability and return-to-work after work-related injury and illness: challenges for future research. Am J Ind Med. 2001;40:464–84. doi: 10.1002/ajim.1116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Turner JA, Franklin G, Turk DC. Predictors of chronic disability in injured workers: a systematic literature synthesis. Am J Ind Med. 2000;38:707–22. doi: 10.1002/1097-0274(200012)38:6<707::aid-ajim10>3.0.co;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dionne CE, Bourbonnais R, Fremont P, et al. A clinical return-to-work rule for patients with back pain. CMAJ. 2005;172:1559–67. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.1041159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Latza U, Kohlmann T, Deck R, et al. Influence of occupational factors on the relation between socioeconomic status and self-reported back pain in a population-based sample of German adults with back pain. Spine. 2000;25:1390–7. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200006010-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Puolakka K, Ylinen J, Neva MH, et al. Risk factors for back pain-related loss of working time after surgery for lumbar disc herniation: a 5-year follow-up study. Eur Spine J. 2008;17:386–92. doi: 10.1007/s00586-007-0552-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shaw WS, Pransky G, Patterson W, et al. Early disability risk factors for low back pain assessed at outpatient occupational health clinics. Spine. 2005;30:572–80. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000154628.37515.ef. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hadler NM, Carey TS, Garrett J. The influence of indemnification by workers' compensation insurance on recovery from acute backache. North Carolina back pain project. Spine. 1995;20:2710–5. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199512150-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hadler NM, Tait RC, Chibnall JT. Back pain in the workplace. JAMA. 2007;297:1594–6. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.14.1594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Durbin D. Workplace injuries and the role of insurance: claims costs, outcomes, and incentives. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1997:18–32. doi: 10.1097/00003086-199703000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Graz B, Wietlisbach V, Porchet F, et al. Prognosis or “curabo effect?”: physician prediction and patient outcome of surgery for low back pain and sciatica. Spine. 2005;30:1448–52. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000166508.88846.b3. discussion 1453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ostelo RW, de Vet HC, Waddell G, et al. Rehabilitation following first-time lumbar disc surgery: a systematic review within the framework of the co-chrane collaboration. Spine. 2003;28:209–18. doi: 10.1097/01.BRS.0000042520.62951.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Atlas SJ, Chang Y, Keller RB, et al. The impact of disability compensation on long-term treatment outcomes of patients with sciatica due to a lumbar disc herniation. Spine. 2006;31:3061–9. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000250325.87083.8d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chibnall JT, Tait RC, Andresen EM, et al. Clinical and social predictors of application for social security disability insurance by workers' compensation claimants with low back pain. J Occup Environ Med. 2006;48:733–40. doi: 10.1097/01.jom.0000214357.14677.5a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Phelan EA, Deyo RA, Cherkin DC, et al. Helping patients decide about back surgery: a randomized trial of an interactive video program. Spine. 2001;26:206–12. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200101150-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Weinstein JN, Clay K, Morgan TS. Informed patient choice: patient-centered valuing of surgical risks and benefits. Health Aff. 2007;26:726–30. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.26.3.726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chou R, Loeser JD, Owens DK, et al. American Pain Society Low Back Pain Guideline Panel. Interventional therapies, surgery, and interdisciplinary rehabilitation for low back pain: an evidence-based clinical practice guideline from the American Pain Society. Spine. 2009;34:1066–77. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181a1390d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]