Abstract

It is generally believed that the vascular endothelium serves as an inflammatory barrier by providing a nonadherent surface to leukocytes. Here, we report that Fas ligand (FasL) is expressed on vascular endothelial cells (ECs) and that it may function to actively inhibit leukocyte extravasation. TNFα downregulates FasL expression with an accompanying decrease in EC cytotoxicity toward co-cultured Fas-bearing cells. Local administration of TNFα to arteries downregulates endothelial FasL expression and induces mononuclear cell infiltration. Constitutive FasL expression markedly attenuates TNFα-induced cell infiltration and adherent mononuclear cells undergo apoptosis under these conditions. These findings suggest that endothelial FasL expression can negatively regulate leukocyte extravasation.

The monolayer of endothelial cells that coat the luminal surface of the vessel wall have numerous physiological functions including prevention of coagulation, control of vascular permeability, maintenance of vascular tone and regulation of leukocyte extravasation1. The inflammatory cytokine TNFα upregulates surface adhesion molecule expression leading to leukocyte adherence to the endothelium2. Adherent leukocytes then migrate to the subendothelial space. These processes are key features of the inflammatory response to pathogens3. Furthermore, abnormal leukocyte infiltration of the vessel wall is believed to be a critical early event in the development of atherosclerotic lesions1.

The Fas-FasL system has been implicated in the regulation of physiological cell turnover, particularly in the immune system.4 Fas is expressed on various cell types, but FasL is much more restricted in its expression. Although the expression of FasL was originally considered restricted to activated T cells and NK cells, FasL has been identified in other cell types including Sertoli cells and cells of the eye. It has been proposed that expression of functional FasL by some tissues contributes to their immune-privileged status by preventing the infiltration of inflammatory leukocytes5,6. However, the utility of FasL for transplantation applications may be limited due to its ability to either recruit neutrophils or induce apoptosis in the transplanted tissue7–9. Recently, constitutive FasL expression has been detected on some tumor cells indicating that it may function to induce apoptotic cell death in Fas-expressing immune cells when they attempt to enter the tumor10–12.

Here, we analyzed the role of endothelial FasL expression in controlling leukocyte extravasation. We report that appreciable levels of FasL are expressed on vascular ECs in vitro and in vivo and that this expression is markedly downregulated by TNFα. The functional significance of this downregulation is indicated by the finding that TNFα-induced leukocyte extravasation can be blocked when FasL is constitutively expressed on the endothelium.

Regulation of endothelial cell FasL expression

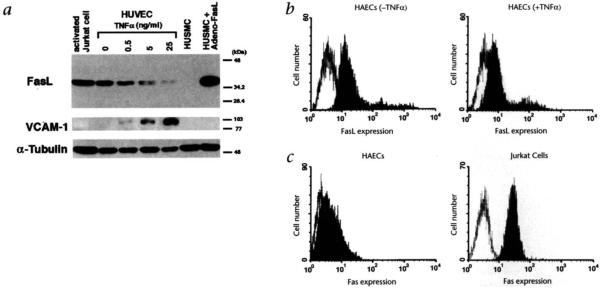

To investigate the regulation of FasL expression on ECs, human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) were subjected to western immunoblotting assays using an anti-FasL monoclonal antibody. These analyses revealed a single band of 37–40 kDa, which had the same mobility as FasL from extracts of activated Jurkat cells13 (Fig. 1a). No FasL was detected in human smooth muscle cell (HUSMC) lysate but a FasL signal was detected in lysates prepared from HUSMCs infected with a replication-defective adenovirus expressing FasL from the cytomegalovirus promoter (Adeno-FasL)14,15. Treatment of HUVECs with TNFα downregulated the FasL expression in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 1a). Immunoblot analyses also revealed that TNFα downregulated FasL expression on human aortic endothelial cells (HAECs) and human microvascular endothelial cells (HMVECs) (data not shown). In agreement with earlier findings2,16,17, TNFα induced a dose-dependent upregulation of the cell adhesion molecule VCAM-1 (Fig. 1a).

Fig. 1.

Regulated expression of FasL on human endothelial cells. a, Immunoblot analysis of FasL and VCAM-1 regulation in HUVECs. HUVECs were incubated for 21 hours with either basal medium or TNFα at 0.5 ng/ml, 5 ng/ml or 25 ng/ml. Cell lysates (15 μg) were loaded onto 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gel and analyzed by western blotting using anti-FasL (upper panel), anti-VCAM-1 (middle) or anti-α-tubulin antibody (lower). Lysate of PMA- and ionomyosin-activated Jurkat cells and HUSMCs infected with Adeno-FasL (multiplicity of infection of 100) served as positive controls for FasL. Lysate of uninfected HUSMCs were probed to demonstrate antibody specificity, b, Flow cytometric analysis of FasL expression on HAECs. HAECs were incubated in either basal medium (left panel) or 25 ng/ml TNFα (right panel) for six hours. Endothelial cells were detached from the culture plate with 0.5% EDTA and incubated with anti-FasL monoclonal antibody (A11, Alexis Corp., San Diego, CA) (filled curve) or with rat IgM (open curve) in PBS with 10% FBS, followed by incubation with FITC-conjugated anti-rat IgM. c, Flow cytometric analysis of Fas expression on HAECs and Jurkat cells. Cells were incubated with an FITC-conjugated anti-Fas monoclonal antibody (filled curve) or with an FITC-conjugated mouse IgG (open curve).

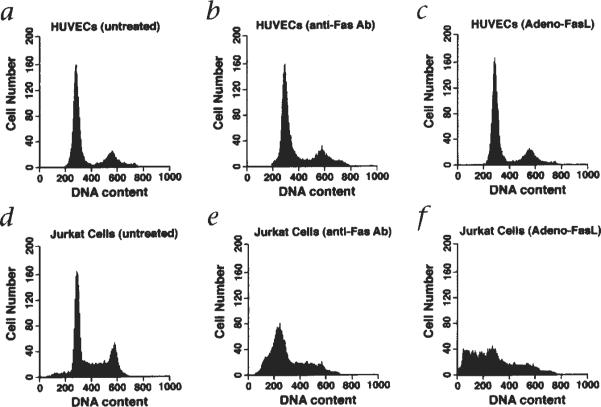

Flow cytometric analyses were performed to examine FasL expression on the cell surface of vascular ECs. Consistent with data from the western blot analyses, incubation with TNFα decreased the expression of FasL on HAECs (Fig. 1b) and HMVECs (not shown). EC expression of the FasL receptor, Fas, was also examined by flow cytometry (Fig. 1c). Fas expression was detectable on HAECs but it was present at lower levels than on Jurkat cells (Fig. 1c). Despite Fas expression on ECs, these cells do not undergo apoptosis when exposed to Adeno-FasL or an anti-Fas antibody that can function as a receptor agonist (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Endothelial cells are resistant to Fas-mediated cell death. HUVECs or Jurkat cells were grown in basal medium, harvested, fixed with 70% ethanol and stained with propidium iodide as described14. DNA content was analyzed by flow cytometry (a and d). HUVECs and Jurkat cells were incubated with an agonistic anti-Fas monoclonal antibody (0.5 μg/ml, clone CH11, MBL, Japan) for 16 hours prior to harvesting and analysis (b and e). HUVECs and Jurkat cells were infected with Adeno-FasL at a multiplicity of infection of 300 for 48 hours prior to harvesting and analysis (c and f).

Cytotoxic activity of endothelial cell FasL

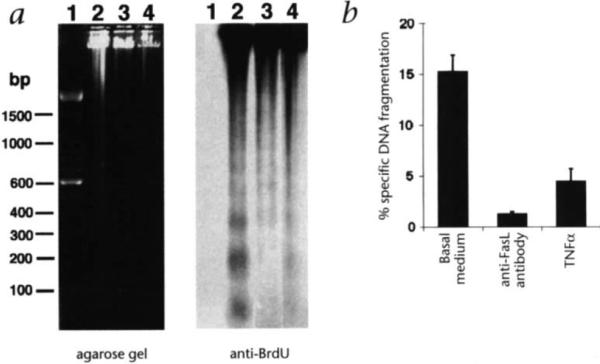

To determine whether FasL expression on ECs is functional, HAECs were co-cultured with P815-huFas target cells that were labeled with BrdU or 3H-thymidine. After 18 hours co-culture, significant target cell DNA fragmentation was observed either by agarose gel electrophoresis and immunoblotting with BrdU-specific antibody (Fig. 3a) or by calculating the specific fragmentation of 3H-thymidine-labeled DNA (Fig. 3b). Prior treatment of the HAECs with TNFα, at a dose that downregulates FasL expression, significantly decreased the cytotoxic activity of HAECs (Fig. 3a and b). HAECs pre-infected with Adeno-FasL, which constitutively express FasL, displayed higher frequencies of target cell DNA fragmentation that was not inhibited by TNFα treatment (not shown). To further demonstrate that the cytotoxic activity of HAECs is mediated by Fas-FasL interaction, HAECs were incubated with a neutralizing anti-FasL antibody for 30 minutes prior to the co-culture assay. Treatment with antibody completely inhibited the cytotoxic activity of HAECs (Fig. 3b), similar to reports that this antibody can inhibit the cytotoxicity of both soluble FasL on W4 cells18 and simian immunodeficiency virus-infected Jurkat cells19.

Fig. 3.

Cytotoxic activity of endothelial cells to P815-huFas cells. a, P815-huFas cells were labeled with BrdU and applied to HAEC cultures pre-treated with either basal medium or TNFα. Genomic DNA from both P815-huFas cells and HAECs was loaded on an 1.5% agarose gel (left panel). DNA was transferred onto a nylon membrane and the DNA fragmentation of P815-huFas cells was detected by a immunoblotting using anti-BrdU antibody (right panel). Lane 1, 100 bp molecular size standard; lane 2, P815-huFas cells co-cultured with HAECs; lane 3, P815-huFas cells co-cultured with HAECs which have been pre-treated with TNFα (10 ng/ml); and lane 4, P815-huFas cells alone, b, P815-huFas cells were labeled with 3H-thymidine and applied to HAECs that were pre-treated with either basal medium or TNFα (10 g/ml). Cells were harvested after 18 hours co-culture and the percentage of specific DNA fragmentation was calculated as described in Methods. A neutralizing anti-human FasL antibody (4H9) was applied to HAECs 30 min. before co-culturing. All values are presented as mean ± S.E.M.

FasL inhibits leukocyte extravasation

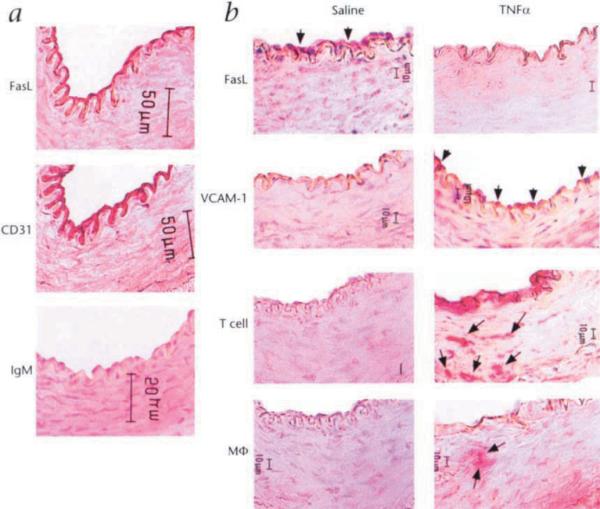

FasL expression was detected in the endothelium of the central artery of the rabbit ear as determined by co-localization with CD31, an established marker for vascular endothelial cells20 (Fig. 4a). Analysis of FasL regulation was performed by applying a tourniquet at the base of the ear, to temporarily interrupt blood flow, and infusing TNFα or PBS. Following a 15 minute incubation, blood flow was restored and FasL expression was assessed by immunohistochemistry at 30 hours post-treatment. In the artery treated with TNFα, FasL expression by the endothelium was markedly downregulated relative to the PBS treated vessels (Fig. 4b). TNFα treatment also upregulated the expression of the adhesion molecule VCAM-1 and robust T lymphocyte and macrophage infiltration was observed under these conditions.

Fig. 4.

Regulated expression of FasL on vascular endothelial cell in vivo. a, A cryosection of the central artery of an untreated rabbit ear was stained for FasL and an adjacent section was stained for CD31, an antigen expressed by endothelial cells. A biotin-conjugated rat IgM was used as an isotype control for the anti-FasL antibody stain, b, Central rabbit ear arteries were temporarily isolated by application of a tourniquet and incubated with either PBS or TNFα (50 ng) for 15 min. Thirty hours after blood flow was restored, the arteries were harvested and snap-frozen in embedding compound and cryosections were stained for FasL, VCAM-1, CD3 (T cells) or RAM 11. Mϕ, macrophages. Bar, 10 μm.

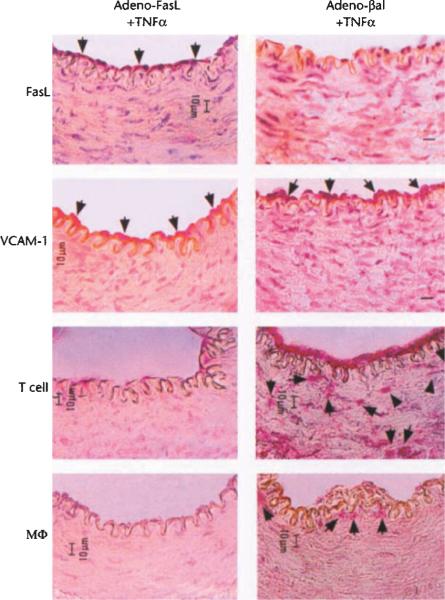

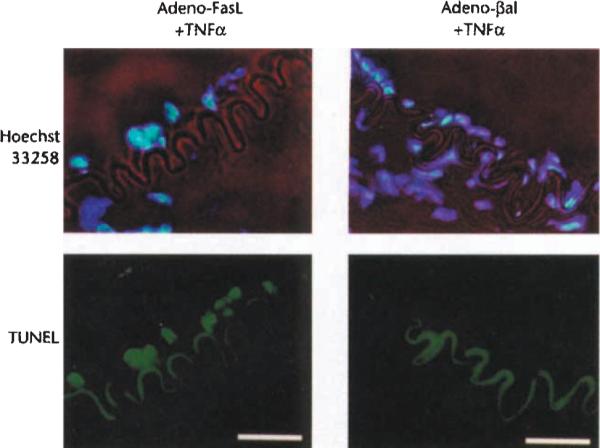

To determine the functional significance of FasL downregulation in vivo, rabbit ear central arteries were temporarily isolated and incubated for 15 minutes with Adeno-FasL 12 hours prior to treatment with TNFα. At 30 hours post-cytokine treatment, FasL expression by the endothelium was readily detectable in the Adeno-FasL pre-treated vessels, but not in vessels pre-treated with the control construct Adeno-βgal, a replication defective adenovirus expressing β-galactosidase (Fig. 5). Though VCAM-1 expression was upregulated following treatment with TNFα, T cell and macrophage infiltration was markedly attenuated in vessels that were transduced with Adeno-FasL but not in the Adeno-βgal-transduced vessels (Fig. 5 and Table 1). In control animals, Adeno-FasL-infected vessels treated with PBS were negative for VCAM-1 expression and for T cell and macrophage infiltration (data not shown). TUNEL staining of the Adeno-FasL-treated vessels at four hours post-cytokine treatment revealed mononuclear cells undergoing apoptosis while attached to the luminal surface of endothelium, while mononuclear cell apoptosis was not detected when arteries were pre-treated with Adeno-βgal (Fig. 6).

Fig. 5.

Constitutive expression of FasL prevents TNFα-induced T cell and macrophage infiltration. Rabbit central ear arteries were isolated and infected with either Adeno-FasL (1 × 107 pfu) or Adeno-βgal (1 × 107 pfu) for 15 min. prior to the restoration of blood flow. After 12 hours, the arteries were again isolated and incubated with TNFα (50 ng) for 15 min. Thirty hours after blood flow was restored, arteries were harvested and cryosections were analyzed by immunohistochemical methods for FasL, VCAM-1, T cells and macrophages as described in Methods. Bar, 10 μm.

Table 1.

Effect of constitutive FasL expression on mononuclear cell infiltration

| Saline | TNFα | Adeno-FasL +TNFα | Adeno-βgal +TNFα | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| T cell | 0.2 ± 0.2 | 31.8 ± 12 | 1.5 ± 0.6 | 65.0 ± 23.4 |

| Macrophage | 0 | 4.0 ± 0.9 | 0.5 ± 0.5 | 7.0 ± 1.9 |

Fig. 6.

Chromatin fragmentation in mononuclear cell adhering to the endothelium following the co-administration of Adeno-FasL and TNFα. Rabbit central ear arteries were infected with Adeno-FasL (1 × 107 pfu) or Adeno-(βgal (1 χ 107 pfu) for 15 min. and, after 12 hours, incubated with TNFα (50 ng) for 15 min. Arteries were harvested four hours after TNFα treatment and stained with Hoechst 33258 (blue) to detect total chromatin and TUNEL (green) to detect fragmented chromatin. The internal elastic lamina containing autofluorescent elastin is visible with a filter specific for fluorescein. Bar, 25 μm.

Discussion

The recruitment of leukocytes at sites of inflammation is a multi-step process that involves tethering, rolling, firm adhesion and the migration of these cells to the subendothelial space2. Though much is known about the chemoattractant and adhesion molecules that regulate leukocyte recruitment in response to bacterial infection21, relatively little is known about mechanisms that may actively control the transendothelial cell migration. Here we demonstrate functional FasL expression on the vascular endothelium and its downregulation upon exposure to the inflammatory cytokine TNFα. Adenovirus-mediated constitutive FasL expression by the endothelium markedly reduces the leukocyte extravasation that is induced by local treatment with TNFα. Under these conditions, VCAM-1 is upregulated resulting in the adherence of mononuclear cells, but these cells undergo apoptosis rather than diapedesis. These data suggest that the down-regualtion of FasL by the endothelium is essential for TNFα-induced luekocyte extravasation.

In marked contrast to ECs, Fas-bearing VSMCs are highly sensitive to FasL-induced apoptosis, and the adenovirus construct expressing FasL is a potent inhibitor of neointimal hyperplasia when applied to arteries that have been denuded of endothelium by balloon-injury14. However, Adeno-FasL does not induce detectable apoptosis in cultured ECs nor in the endothelium of rabbit ear central arteries. Presumably ECs are resistant to Fas-mediated cell death either because they normally express relatively low levels of Fas, or they are unable to transmit an apoptosis-inducing signal following the engagement of Fas by FasL as has been suggested by others22. Thus, it is conceivable that the deregulated expression of FasL, Fas or signaling pathway components of this system may be a feature of EC dysfunction in response to injurious agents leading to inflammatory-fibroproliferative disorders of the vessel wall.

Atherosclerosis is believed to result from a chronic, detrimental immune response at localized regions within the vessel1. Our data suggest that FasL may serve an atheroprotective function on the endothelium through its ability to induce apoptosis in mononuclear cells attempting to invade the vessel wall in the absence of normal inflammatory stimuli. Human atherosclerotic plaques contain significant amounts of T lymphocytes and macrophages1,23–27. TNFα is expressed by macrophages and smooth muscle cells at the sites of vascular injury and this cytokine is thought to have an important role in the progression of atherosclerotic lesions28,29. This process is particularly evident in transplant arteriosclerosis, a robust form of atherosclerosis that is responsible for the majority of deaths in heart transplant recipients surviving for one or more years30. Our data suggest that secretion of TNFα by activated cells within an atheroma25,29,31 may downregulate FasL expression in adjacent normal endothelium, promoting more leukocyte extravasation and lesion growth. Consistent with this notion is the observation that blockade of TNFα reduces coronary artery neointimal formation in a rabbit model of cardiac transplant arteriosclerosis, while having no effect on the degree of myocardial rejection32. Therefore, these findings not only suggest an additional function of the vascular endothelium, but may provide insights about the pathogenesis of the atherosclerosis.

Methods

Cells and reagents

HAECs were obtained from Clonetics (San Diego, CA). HMVECs were provided by Joyce Bischoff (Children's Hospital, Boston, MA). Both HAECs and HMVECs were cultured in EGM medium (Clonetics) and were used for this study at less than 9 passages. HUVECs were isolated as described33 and grown in medium 199 with 20% fetal bovine serum. The human T cell leukemia line, Jurkat clone E6-1, was obtained from American Type Culture Collection (Rockville, MD) and maintained in RPMI medium 1640 with 10% fetal bovine serum. Human vascular smooth muscle cells were isolated from a saphenous vein obtained during coronary bypass surgery and cultured as described previously34. Recombinant human TNFα was purchased from R&D systems (Minneapolis, MN). Replication-defective adenovirus constructs encoding murine FasL (Adeno-FasL) or β-galactosidase (Adeno-βgal) under the control of cytomegalovirus promoter were constructed as described previously14,15. Viral titer was measured by standard plaque assay using 293 cells.

Immunoblot analysis of regulation of FasL expression

HUVECs, at approximately 90% confluence, were incubated with basal medium containing different concentrations of TNFα (0, 0.5, 5, 25 ng/ml) for 21 h at 37 °C. Culture medium was removed by washing twice with PBS and cells lysed with a buffer containing 1% NP40, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS, 5 μg/ml leupeptin, 5 μg/ml aprotinin and 2mM PMSF in PBS. The protein content was measured using a BCA protein assay reagent (Pierce, Rockford, IL). The cell lysates (15 μg for each lane) were analyzed by SDS PAGE using a 10% polyacrylamide gel and were transferred to a PVDF membrane (Millipore, Bedford, MA). After blocking with 5% non-fat dry milk in Tris-buffered saline (TBS), the membrane was incubated with an anti-human FasL mouse monoclonal antibody (1:1000, Transduction Laboratories, Lexington, KY), anti-VCAM-1 goat polyclonal antibody (1:500, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) or anti-human α-tubulin mouse monoclonal antibody (1:2000, Calbiochem, San Diego, CA). Membranes were washed in TBS supplemented with 0.05% Tween20 (T-TBS) and incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated sheep antibody to mouse Ig or goat Ig (1:3000, Amersham, Arlington Heights, IL). After washing in T-TBS, antibody binding was detected using enhanced chemiluminescence (Amersham).

Flow cytometric analysis of FasL and Fas expression on EC surfaces

HAECs, at approximately 90% confluence, were incubated with either basal medium or 25 ng/ml TNFα at 37 °C, 5% CO2 for 7 h. HAECs were detached from culture plates using 0.5% EDTA and incubated with anti-FasL monoclonal antibody (A11, Alexis Corp., San Diego, CA) or with rat IgM. Cells were then washed and stained with FITC-conjugated anti-rat IgM antibody (Kirkegaard & Perry Laboratories, Gaithburg, MD). Immunofluorescence staining was analyzed by flow cytometry (Becton Dickinson, Mountain View, CA). To determine Fas expression, HAECs were incubated with an FITC-conjugated anti-Fas monoclonal antibody (clone UB2, Immunotech, Westbrook, ME).

Cytotoxic assay of HAECs on P815-huFas cells

The ability of FasL on ECs to induce apoptosis in Fas-positive target cells was assessed by co-incubating the mastocytoma cells P815 stably transfected with human Fas (P815-huFas, kindly provided by Douglas Green) with HAECs using a technique described previously35. HAECs were plated in triplicate in 24-multiwell tissue culture plates and allowed to reach 90% confluency as a monolayer. HAECs were incubated with either basal medium or medium containing TNFα (10 ng/ml) at 37 °C for 4 h, after which HAECs were washed twice with PBS. P815-huFas cells were labeled with 10 μCi/ml 3H-thymidine (NEN, Boston, MA) for 24 h, washed twice in PBS and then incubated at 37 °C for 8 hours to minimize spontaneous release. P815-huFas cells were applied to HAECs at a ratio of 1:4 (HAECs:P815-huFas) in the absence or presence of the anti-FasL antibody (10 μg/ml, clone 4H9, MBL, Nagoya, Japan), which is capable of neutralizing the cytotoxic activity of human FasL18. The 24-multiwell culture plates were centrifuged at 200g for 2 min and incubated at 37 °C for 18 h. Cells were harvested by trypsinization. The amounts of the fragmented DNA and the retained DNA were measured by liquid scintillation counting, as described36. The percentage of the specific DNA fragmentation was calculated as 100 × (spontaneous - experimental/spontaneous, when experimental refers to counts per min of the retained DNA in the presence of HAECs and spontaneous refers to counts per min of the retained DNA in the absence of HAECs. All values are presented as mean ± S.E.M.

Cytotoxicity was also tested by analyzing the ability of ECs to induce a DNA ladder in target cells. The P815-huFas cells were incubated with 100 μM 5-bromo-2'-deoxy-uridine (BrdU) for 9 h. After washing in PBS, the P815-huFas cells were applied to HAECs and cultured for 18 h. The total genomic DNA from both P815-huFas cells and HAECs was prepared from a well of a 6-well plate as described36 and loaded on a 1.5% agarose gel in 1× TBE buffer. The electrophoretically separated DNA was transferred onto a nylon membrane (Hybond-N, Amersham) and UV-crosslinked. The BrdU-labeled DNA from the P815-huFas cells was detected using an anti-BrdU monoclonal antibody (clone BMC 9318, Boehringer Mannheim) as described for the immunoblot analysis.

Local administration of cytokines into rabbit ear central arteries

The effect of TNFα on the endothelial expression of FasL in vivo was determined using the rabbit ear central artery which is superficial and therefore easily accessible for isolation and injection37. New Zealand White rabbits (3,500–4,000 g) were sedated by intramuscular injection of xylazine (5 mg/kg) and anesthetized using an intramuscular injection of ketamine (40 mg/kg) and acepromazine (1 mg/kg). The central artery of the rabbit ear was isolated by applying a tourniquet at the base of the ear, temporarily interrupting blood flow. The artery was then cannulated with a 25-gauge needle and one ml of TNFα diluted in PBS (50 ng/ml) or PBS was then infused into the isolated segment and incubated for 15 min. After the restoration of blood flow, rabbits were killed using pentobarbital at either 4 or 30 h after the treatment. The arteries were harvested and snap-frozen in OCT compound (Miles Inc., Elkhart, IN). To study the effect of constitutive FasL expression on mononuclear cell infiltration, the isolated segment of a rabbit ear artery was incubated with 1 × 107 pfu of either Adeno-FasL or Adeno-βgal for 15 min. These replication-defective adenoviral constructs express the murine FasL or E. coli β-galactosidase genes from the cytomegalovirus promoter14. At 12 h post-infection, the artery was treated with PBS or TNFα as described above. The experimental protocol was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and complied with the National Institutes of Health “Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals”.

Immunohistochemistry

Cryosections (5 μm thick) were mounted on microscope slides and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 10 min. Sections were washed twice in PBS and blocked with 5% normal goat serum and 0.01% Triton-X in PBS for 1 h at room temperature. Biotin-conjugated monoclonal antibody to FasL (1:2000, clone A11, Alexis Corp., San Diego, CA) in PBS with 1% goat serum and 0.01% Triton-X was added to the sections for one h at room temperature. Sections were washed three times in PBS followed by the addition of alkaline phosphatase-conjugated streptavidin for 5 min at 37 °C. Sections were washed three times in PBS and antibody location was determined with the addition of Fast Red substrate (BioGenex Laboratories, San Ramon, CA). Color development was stopped by washing in distilled water. Distributions of ECs, T lymphocytes and macrophages were revealed in adjacent sections using an anti-CD31 monoclonal antibody (1:100, clone JC/70A, DAKO, CA), an anti-CD3 monoclonal antibody (1:2000, clone 6B10.2, Santa Cruz Biotech, Santa Cruz, CA) and an anti-macrophages monoclonal antibody (1:1000, clone RAM11, DAKO, Carpinteria, CA), respectively. Expression of VCAM-1 was revealed using a goat polyclonal antibody against VCAM-1 (1:1000, clone C-19, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA). Sections were counter-stained with hematoxylin.

TUNEL staining

TdT-mediated dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL) technique was used to detect apoptotic cells in the rabbit ear artery. Cryosections (5 μm thick) were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 20 min and permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 in 0.1% sodium citrate for 2 min at 4 °C. Terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase enzyme and dUTP conjugated to a fluorescein cocktail were added to the tissue sections according to the manufacturer's specifications (Boehringer Mannheim, Indianapolis, IN). Nuclei were counterstained with Hoechst 33258 (Sigma) and mounted for fluorescence (Kirkegaard & Perry Laboratories, Gaithersburg, MD). Specimens were examined and photographed on a Nikon Diaphot microscope.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH Grants AG15052, HL50692 and AR40197 to K.W. M.S. is a recipient of a research fellowship from the American Heart Association, Massachusetts Affiliate, Inc. We thank Roy C. Smith for his critical reading of this manuscript.

References

- 1.Ross R. The pathogenesis of atherosclerosis: a perspective for the 1990s. Nature. 1993;362:801–809. doi: 10.1038/362801a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Springer TA. Traffic signals on endothelium for lymphocyte recirculation and leukocyte emigration. Ann. Rev. Physiol. 1995;57:827–872. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ph.57.030195.004143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pfieffer K, et al. Mice deficient for the 55kd tumor necrosis factor receptor are resistant to endotoxic shock, yet succumb to L. monocytogenes infection. Cell. 1993;73:457–467. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90134-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nagata S, Golstein P. The Fas death factor. Science. 1995;267:1449–1456. doi: 10.1126/science.7533326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bellgrau D, et al. A role of CD95 ligand in preventing graft rejection. Nature. 1995;377:630–632. doi: 10.1038/377630a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Griffith TS, Brunner T, Fletcher SM, Green DR, Ferguson TA. Fas ligand-induced apoptosis as a mechanism of immune privilege. Science. 1995;270:1189–1192. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5239.1189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kang S-M, et al. Immune response and myoblasts that express Fas ligand. Science. 1997;278:1322–1324. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5341.1322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Seino K, Kayagaki N, Okumura K, Yagita H. Antitumor effect of locally produced CD95 ligand. Nature Med. 1997;3:165–170. doi: 10.1038/nm0297-165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kang S-M, et al. Fas ligand expression in islets of Langerhans does not confer immune privilege and instead targets them for rapid destruction. Nature Med. 1997;3:738–743. doi: 10.1038/nm0797-738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Strand S, et al. Lymphocyte apoptosis induced by CD95 (APO-1/Fas) ligand expressing tumor cells-A mechanism of immune evasion? Nature Med. 1996;2:1361–1366. doi: 10.1038/nm1296-1361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hahne M, et al. Melanoma cell expression of Fas (Apo-1/CD95) ligand: Implications for tumor immune escape. Science. 1996;274:1363–1366. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5291.1363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Niehans GA, et al. Human lung carcinomas express Fas ligand. Cancer Res. 1997;57:1007–1012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Suda T, Nagata S. Purification and characterization of the Fas-ligand that induces apoptosis. J. Exp. Med. 1994;179:873–879. doi: 10.1084/jem.179.3.873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sata M, et al. Fas ligand gene transfer to the vessel wall inhibits neointima formation and overrides the adenovirus-mediated T cell response. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1998;95:1213–1217. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.3.1213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Muruve D, et al. Adenovirus mediated expression of Fas ligand induces hepatic apoptosis after systemic administration and apoptosis of ex vivo infected pancreatic islet allografts and isografts. Human Gene Ther. 1997;8:955–963. doi: 10.1089/hum.1997.8.8-955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Luscinskas FW, Gimbrone MA. Endothelial-dependent mechanism in chronic inflammatory leukocyte recruitment. Ann. Rev. Med. 1996;47:413–421. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.47.1.413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Adams MR, Jessup W, Hailstones D, Celermajer DS. L-Arginine reduces human monocyte adhesion to vascular endothelium and endothelial expression of cell adhesion molecules. Circulation. 1997;95:662–668. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.95.3.662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tanaka M, et al. Fas ligand in human serum. Nature Med. 1996;2:317–322. doi: 10.1038/nm0396-317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xu X-N, et al. Evasion of cytotoxic T lymphocyte (CTL) responses by Nef-dependent induction of Fas ligand (CD95L) expression on simian immunodeficiency virus-infected cells. J. Exp. Med. 1997;186:7–16. doi: 10.1084/jem.186.1.7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Parums D, et al. JC70, a new monoclonal antibody that detects vascular endothelium associated antigen on routinely processed tissue sections. J. Clin. Pathol. 1990;43:752–757. doi: 10.1136/jcp.43.9.752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Picker LJ, Butcher EC. Physiological and molecular mechanisms of lymphocyte homing. Ann. Rev. Immunol. 1993;10:561–591. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.10.040192.003021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Richardson BC, Lalwani ND, Johnson KJ, Marks RM. Fas ligation triggers apoptosis in macrophages but not endothelial cells. Eur. J. Immunol. 1994;24:2640–2645. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830241111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wick G, Schett G, Amberger R, Kleindienst R, Xu Q. Is atherosclerosis an immunologically mediated disease? Immunol. Today. 1995;16:27–33. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(95)80067-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jonasson L, Holm J, Skalli O, Bondjers G, Hansson GK. Regional accumulations of T cells, macrophages, and smooth muscle cells in the human atherosclerotic plaque. Arteriosclerosis. 1986;6:131–138. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.6.2.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Munro JM, van der Walt JD, Munro CS, Chalmers JAC, Cox E. An immunohistochemical analysis of human aortic fatty streaks. Hum. Path. 1987;18:375–380. doi: 10.1016/s0046-8177(87)80168-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Emeson EE, Robertson AL. T lymphocytes in aortic and coronary intimas: their potential role in atherogenesis. Am. J. Pathol. 1988;130:369–376. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.van der Wal AC, Das PK, van de Berg DB, van der Loos CM, Becker AE. Atherosclerotic lesions in human: in situ immunophenotypic analysis suggesting an immune mediated response. Lab. Invest. 1989;61:166–170. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tanaka H, Swanson SJ, Sukhova G, Schoen FJ, Libby P. Smooth muscle cells of the coronary arterial tunica media express tumor necrosis factor-α and proliferate during acute rejection of rabbit cardiac allografts. Am. J. Pathol. 1995;147:617–626. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Libby P, Hansson GK. Involvement of the immune system in human atherogenesis: Current knowledge and unanswered questions. Lab. Invest. 1991;64:5–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Billingham ME. Cardiac transplant atherosclerosis. Transpl. Proc. 1987;19:19–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hansson GK, Holm J, Jonasson L. Detection of activated T lymphocytes in the human atherosclerotic plaque. Am. J. Pathol. 1989;135:169–175. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Clausell N, Milossi S, Sett S, Rabinovitch M. In vivo blockade of tumor necrosis factor-α in cholesterol-fed rabbits after cardiac transplant inhibits acute coronary artery neointimal formation. Circulation. 1994;89:2768–2779. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.89.6.2768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jaffe EA, Nachman RL, Becker CG, Minick RC. Synthesis of antihemophilic factor antigen by cultured human endothelial cells. J. Clin. Invest. 1973;52:2745–2756. doi: 10.1172/JCI107471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pickering JG, et al. Smooth muscle cell outgrowth from human atherosclerotic plaque: implications for the assessment of lesion biology. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 1992;20:1430–1439. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(92)90259-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Matzinger P. The JAM test. A simple assay for DNA fragmentation and cell death. J. Immunol. Methods. 1991;145:185–192. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(91)90325-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McGahon AJ, et al. The end of the cell line: Methods for the study of apoptosis in vitro. In: Schwartz LM, Osborne BA, editors. Cell death. Vol. 46. Academic Press, Inc; San Diego: 1995. pp. 153–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Losordo DW, et al. Use of the rabbit ear artery to serially assess foreign protein secretion after site-specific arterial gene transfer in vivo. Circulation. 1994;89:785–792. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.89.2.785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]