Abstract

A synthesis of insights from functional and evolutionary studies reveals how the phytochrome photoreceptor system has evolved to impart both stability and flexibility. Phytochromes in seed plants diverged into three major forms, phyA, phyB, and phyC, very early in the history of seed plants. Two additional forms, phyE and phyD, are restricted to flowering plants and Brassicaceae, respectively. While phyC, D, and E are absent from at least some taxa, phyA and phyB are present in all sampled seed plants and are the principal mediators of red/far-red–induced responses. Conversely, phyC-E apparently function in concert with phyB and, where present, expand the repertoire of phyB activities. Despite major advances, aspects of the structural-functional models for these photoreceptors remain elusive. Comparative sequence analyses expand the array of locus-specific mutant alleles for analysis by revealing historic mutations that occurred during gene lineage splitting and divergence. With insights from crystallographic data, a subset of these mutants can be chosen for functional studies to test their importance and determine the molecular mechanism by which they might impact light perception and signaling. In the case of gene families, where redundancy hinders isolation of some proportion of the relevant mutants, the approach may be particularly useful.

PHYTOCHROMES HAVE DIVERSE ACTIVITIES IN TRACHEOPHYTES

Variable responses to light indicate that plants use specific light signals to determine their place in time and space, allowing them to synchronize their growth, metabolism, and developmental transitions to the environments in which they occur. In autotrophic plants, light cues provide circadian and seasonal information, used to mediate the induction and inhibition of flowering, the induction and breaking of bud dormancy, the opening and closing of stomata and flowers, and the cycling between sleep and waking movements. Light cues also provide positional information, used to induce and inhibit germination, control the pattern of seedling development, induce directional growth, influence adult architecture, and detect and avoid neighbors.

Phytochrome Response Modes

Phytochrome photoreceptors play direct roles in germination, seedling establishment, flowering, dormancy, nyctinasty, stomatal development, plant architecture, and shade avoidance (reviewed in Franklin and Quail, 2010). Among the most important of light cues used by plants are those that indicate where they are in relation to neighbors that might impinge on their access to PAR. Phytochromes are uniquely suited to the task of neighbor detection due to their capacity to interconvert between forms with absorption maxima in the red (R; ∼ 660 nm) and far red (FR; ∼ 730 nm). Via the covalently attached bilin chromophore, absorption of red light by the Pr form induces conversion to the Pfr form; likewise, absorption of far-red light by Pfr induces conversion to Pr. Thus, at any one time, Pr and Pfr are in a dynamic equilibrium that reflects the relative proportions of R and FR in ambient light (Mancinelli, 1994). Because plant pigments absorb most visible light below 700 nm, this equilibrium reflects the presence or absence of neighboring vegetation by its impact on the ratio of R to FR light, which is ∼ 1.05 to 1.25 above the canopy and ranges to as low as 0.05 below the canopy (Smith, 1982). Small changes in the R:FR ratio may lead to large changes in the ratio of Pfr to Ptotal so that even very small changes are detectable (Smith, 1982), such as those that occur in the light reflected from stems of small neighbors (Ballaré et al., 1990). Three phytochrome physiological response modes are recognized according to the level of Pfr/Ptotal required to saturate the response. When newly synthesized, such as in dark-imbibed seeds or in dark-grown seedlings, phytochrome is in the Pr form; in such cases, Pr predominates and extremely low fluences of light in most regions of the visible spectrum raise the level of Pfr. Responses saturated by millisecond exposure to light that lead to very low levels of Pfr (10−6 to 10−3 Pfr/Ptotal) irrespective of wavelength are called very low fluence responses (VLFRs); they are irreversible and allow very rapid responses to barely detectable levels of light (Casal et al., 1997). Responses saturated by intermediate fluences (1 to 1000 μ mol m−2 s−1) are low fluence responses (LFRs) and are characterized by repeated reversibility, with R inducing the response and FR reversing it. The relationship between Pfr/Ptotal and LFR is logarithmic, and saturation of the responses occurs at higher levels of Pfr/Ptotal (10−2 to 0.87; Smith and Whitelam, 1990); the greater exposure required to induce germination in the LFR mode suggests that the role of phytochromes in these instances is to detect relatively open habitats or canopy gaps large enough for the penetration of direct sunlight for several hours per day (Smith, 1995). This is consistent with the observation that shade light, in addition to continuous FR, can reverse R-induced LFR (Frankland and Taylorson, 1983). In contrast with VLFR and LFR, which require transient exposures of lesser or greater duration, respectively, high-irradiance responses (HIRs) require continuous, long-term irradiation, and they are dependent on wavelength; in the case of the FR-HIR, maximum response occurs at wavelengths that maintain low levels of Pfr for long periods of time (Smith and Whitelam, 1990), such as would occur under a canopy, leaf litter, or in the first few millimeters under the soil surface.

Phytochrome Activities under Canopies May Be Antagonistic

Seedling deetiolation is a critical phase of development that involves the inhibition of extension growth, stimulation of cotyledon expansion, activation of chloroplast development, and the accumulation of chlorophyll and anthocyanins. In open habitats, phytochrome LFRs mediate seedling development. Under the decreasing R/FR ratios associated with canopy shade, LFRs are reduced due to reduction in Pfr/Ptotal, and extension growth is enhanced rather than inhibited, while development of cotyledons, leaves, and the photosynthetic apparatus is reduced (these are aspects of shade avoidance; reviewed in Franklin, 2008). Prior to the origin of tracheophytes (vascular plants), terrestrial vegetation was dominated by the diminutive haploid gametophytes of nonvascular plants, such as liverworts and mosses. LFRs may have been more important than shade avoidance, although components of shade avoidance are known in charophytes and liverworts (Mathews, 2006), which are green algal and early-diverging embryophytes (nonalgal land plants), respectively. Moreover, early tracheophytes might have relied mostly on LFRs for detection of open habitats. Paleobotanical data suggest that the structure of plant communities in the Lower to Middle Devonian, ∼ 375 to 400 million years ago, was controlled largely by the ability of early tracheophytes to locate patches opened for colonization by disturbance (DiMichele et al., 1992). However, as they diversified and gained the capacity to produce substantial canopies, shaded habitats and persistent shade became more prevalent. Plant lineages that persisted or originated after the origin and diversification of forest canopies faced the challenge of evolving a photoreceptor system that would allow them to respond appropriately in a range of light environments, particularly during seedling establishment.

In more derived tracheophytes, such as seed plants and ferns, deetiolation is induced both by R and FR (Mathews, 2006), acting in the LFR and FR-HIR modes, respectively. Light-sensitive germination under canopies is also controlled by phytochromes acting in the FR-HIR (Botto et al., 1996). Moreover, under low R:FR ratios, several of the morphological and biochemical changes associated with reduced LFR may antagonize those associated with FR-HIR (McCormac et al., 1992; Reed et al., 1994; Mazzella et al., 1997; Cerdán et al., 1999; Devlin et al., 2003; Salter et al., 2003). For example, reduction in LFR results in an increase in elongation growth and a decrease in leaf development and chlorophyll production (shade avoidance responses), whereas FR-HIRs result in a decrease in elongation growth and an increase in leaf development and chlorophyll production.

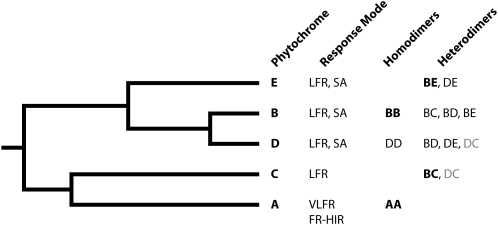

The discovery of two pools of phytochrome protein in plant tissues, one light labile (type I) and the other light stable (type II) (Tokuhisa et al., 1985), followed by the discovery that phytochromes are encoded by five genes, PHYA-E, in Arabidopsis thaliana (Sharrock and Quail, 1989; Clack et al., 1994) and by a small gene family in many other plants (Mathews and Sharrock, 1997), suggest that gene duplication and divergence have allowed the subdivision of antagonistic and complementary functions between multiple photoreceptors. Indeed, in Arabidopsis, phyA and phyB are the principal mediators of red light–mediated development in FR- and R-rich environments, respectively (Figure 1). phyA is the predominant form in etiolated tissue and mediates germination, deetiolation, and daylength perception under continuous FR (Nagatani et al., 1993; Parks and Quail, 1993; Whitelam et al., 1993; van Tuinen et al., 1995; Shinomura et al., 2000; Takano et al., 2001), where it may also condition early neighbor detection (Casal et al., 1997). Due to rapid protein degradation and decreased transcription in the light (Sharrock and Clack, 2002), phyA has a reduced ability to antagonize shade avoidance responses under canopies once seedlings are established, although a persistent FR-HIR has been detected in woodland genotypes of Impatiens capensis (von Wettberg and Schmitt, 2005). In Arabidopsis, phyA may be the sole mediator of VLFR, detecting light conditions that the other phytochromes cannot distinguish from darkness, such as deep canopy shade, and transient exposures that result from tilling or disturbance (reviewed in Casal et al., 1997). Null mutants of phyA do not survive under natural canopies (Yanovsky et al., 1995), suggesting that it is important for seedling development in deeply shaded environments. phyA, though present at low levels in light-grown tissues, also functions as a sensor of high irradiance R, contributing to seedling deetiolation, leaf development, plant architecture, root phototropism, and enhancement of phototropic curvature in blue light (Parks et al., 1996; Kiss et al., 2003; Tepperman et al., 2006; Franklin et al., 2007; Kneissl et al., 2008). With respect to its functions as an FR or dim light sensor, there apparently is little functional redundancy among phyA and the other Arabidopsis phytochromes (Figure 1) save that phyE contributes to germination under continuous FR (Hennig et al., 2002). phyB is the predominant form in light-grown tissue, is stable in light, and mediates LFRs to continuous R and pulsed R (Reed et al., 1993; Robson et al., 1993; Halliday et al., 1994). It functions in R-induced seed germination, deetiolation, and daylength perception. Thus, phyB also is the primary mediator of shade avoidance, with additional light-stable forms in Arabidopsis, phyD and phyE, making lesser (Franklin, 2008) though perhaps important fine-tuning (Ballaré, 2009) contributions. The fourth light-stable form is phyC, a weak R sensor that functions in leaf development and perception of photoperiod (Franklin et al., 2003; Monte et al., 2003). As discussed later in the review, recent studies have revealed roles for phyC-E that were not apparent from the initial characterization of the phyC-E null mutants.

Figure 1.

Relationships, Physiological Response Modes, and Dimerization Properties of Arabidopsis Phytochromes A to E.

SA, shade avoidance. Bold font indicates predominant form of dimer detected, if one exists; gray font indicates a dimer that is not detected unless phyB is absent (Clack et al., 2009).

INSIGHTS FROM EVOLUTIONARY STUDIES

Many of the determinants of functional specificity that distinguish phyA and phyB have been identified from the characterization of monogenic and multiple phytochrome mutants of Arabidopsis, such as those cited above (along with many others), from the dissection of signaling pathways (Castillon et al., 2007; Jiao et al., 2007; Bae and Choi, 2008), and from studies of expression patterns and protein levels (Goosey et al., 1997; Sharrock and Clack, 2002), dimerization (Sharrock and Clack, 2004; Clack et al., 2009), nuclear localization (Kircher et al., 2002), protein–chromophore interactions (Hanzawa et al., 2002), and phyA dark reversion rates (Eichenberg et al., 2000b). Despite these many advances, aspects of the structural-functional models for these photoreceptors remain elusive. Evolutionary studies are the source of unique and complementary advances because they reveal features that potentially are critical to the individual functions of phyA and phyB. Phylogenetic surveys reveal when the split between PHYA and PHYB sequences occurred and provide information about their distribution in other plants. Comparative functional studies test whether sequence homology is a good predictor of functional conservation, and comparative sequence analyses reveal potential determinants of functional specificity that can be tested experimentally.

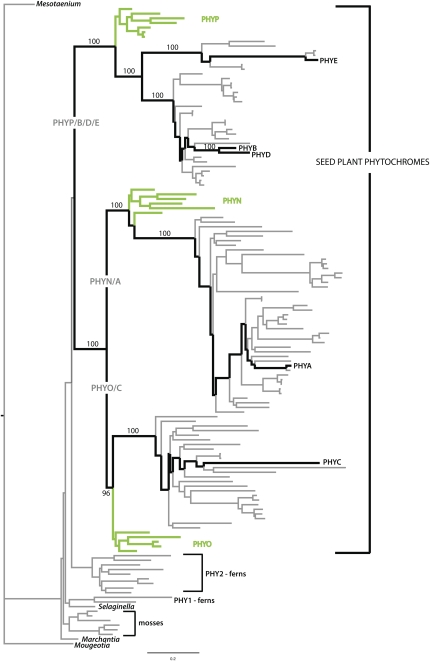

Phylogenetic Surveys

The first phytochrome peptide tree suggested that the duplication giving rise to PHYA and PHYB was older than the split between eudicot and monocot angiosperms (Sharrock and Quail, 1989). Whether the PHYA/B split occurred earlier in the history of seed plants could not be determined because this tree and other early PHY trees (e.g., Heyer and Gatz, 1992; Clack et al., 1994; Mathews et al., 1995; Pratt et al., 1995) included no gymnosperm PHY. The first trees to include gymnosperm PHY (PHYN, PHYO, and PHYP) suggested the split between PHYA and PHYB was even deeper, predating the divergence of angiosperms from other seed plants; the PHYP sequence from Pinus attached to the branch including PHYB and PHYB-related sequences, while the PHYO sequence from Picea attached below the node uniting PHYA with PHYC sequences (Mathews and Sharrock, 1997; Schneider-Poetsch et al., 1998; Clapham et al., 1999). These trees also included sequences from ferns, lycophytes, and mosses and thus revealed that the divergence between PHYA and PHYB, and their gymnosperm homologs, occurred after the free-sporing groups had originated and diverged from other plants, since none of the sequences from free-sporing species attached to branches within the seed plant clade. The analysis of Mathews and Sharrock (1997) provided statistical support for the single origin of seed plant phytochromes (92% bootstrap value). However, in a recently inferred tree, support for the seed plant phytochrome node is low (Figure 2). This tree was inferred from full-length phytochrome amino acid sequences available in GenBank, with the addition of newly sequenced full-length or nearly-full-length sequences to better represent gymnosperms and basal nodes in the angiosperm tree (see Supplemental Data Set 1 online; Mathews et al., 2010). Resolution of this node is sensitive to taxon sampling, and full-length sequences from ferns, especially from lineages that diverge early in their history, as well as from lycopods and Equisetum, are needed to further understand phytochrome phylogeny among tracheophytes. Nonetheless, the tree provides firm evidence that PHYN, PHYO, and PHYP are the gymnosperm orthologs of angiosperm PHYA, PHYC, and PHYP, respectively, resolving the ambiguity that had persisted around the relationships of PHYN, PHYO, PHYA, and PHYC (Mathews, 2006).

Figure 2.

Viridophyte Phytochrome Tree.

Black branches trace the relationships of Arabidopsis PHYA-E; gymnosperm PHYN, O, and P (green branches) are shown to be orthologs of PHYA, C, and B, respectively. The optimal maximum likelihood tree and bootstrap percentages (numbers above branches, except for the PHYO/C node, where it is below the branch) were inferred from analyses of full-length or nearly-full-length amino acid sequences using RAxML 7.0.4 (Stamatakis, 2006), a phytochrome-specific amino acid transition matrix (Mathews et al., 2010); the thorough (designated with the f -i switch) bootstrap option was used. Outgroups for rooting the tree are the PHY sequences from M. caldariorum and M. scalaris. Seed plant species relationships are discussed by Mathews et al. (2010). Amino acid alignment is provided as Supplemental Data Set 1 online.

The phytochrome tree shows that the split between PHYA and PHYB is ancient, at least as old as the most recent common ancestor of angiosperms and living gymnosperms (Figure 2) or ∼ 330 to 365 million years ago (Magallón and Sanderson, 2005). The well-supported monophyly of Arabidopsis PHYA and PHYB and their respective orthologs in other species indicates that these genes have been evolving independently since deep in the history of seed plants, and there is little evidence of the frequent expansion and contraction in copy number that has been noted in many plant gene families (Sterck et al., 2007; Flagel and Wendel, 2009). In living gymnosperms, PHYN (PHYA ortholog) is duplicated in cupressophytes (conifer families other than Pinaceae), and PHYP (PHYB ortholog) is duplicated in Pinaceae (Schmidt and Schneider-Poetsch, 2002; Mathews et al., 2010). In Pinus sylvestris, the PHYO (PHYC ortholog) lineage appears to be greatly expanded to include a large number of apparent pseudogenes (García-Gil, 2008). A functional copy is also retained, and it remains to be determined if pseudogene expansion has implications for phytochrome function. In angiosperms, an early duplication led to the independently evolving PHYE lineage, and both PHYA and PHYB are duplicated in some plant groups (Mathews, 2006), but neither PHYA nor PHYB has been lost from any sampled plant species. Populus trichocarpa has the smallest phytochrome gene family with respect to the number of major lineages sampled to date, with one copy of PHYA and two of PHYB (Howe et al., 1998; Tuskan et al., 2006; Figure 2).

Conservation of phyA and phyB Function

It seems likely that this conservative pattern of gene evolution results from the functional importance and distinctiveness of each photoreceptor, although few data are available to test the conservation of gene function in seed plants other than Arabidopsis. Nonetheless, the available data from Brassica, cucumber (Cucumis sativus), pea (Pisum sativum), tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum), tomato (Solanum lycopersicum), maize (Zea mays), and rice (Oryza sativa) suggest that the functions of phyA and phyB are generally conserved and were established prior to the split of eudicots and monocots (Ballaré et al., 1991; Childs et al., 1991; Devlin et al., 1992; Weller et al., 2004; Sheehan et al., 2007; Takano et al., 2005, 2009), although independently duplicated phyB may subdivide functions differently than is seen in Arabidopsis phyB and phyD (e.g., Hudson et al., 1997; Kerckhoffs et al., 1999; Weller et al., 2000; Sheehan et al., 2007). Functional data from dicots that diverge deeper than the eudicot/monocot split in the angiosperm phylogenetic tree are needed to infer that their functions are conserved in all angiosperms, but this is a reasonable hypothesis. LFR- and FR-HIR–mediated development and shade avoidance occur in gymnosperms (reviewed in Mathews, 2006), but there are no studies that link these responses to a specific phytochrome. Nonetheless, the widespread conservation of PHYA and PHYB homologs, together with the available functional data, suggest that in seed plants these two PHYs form a conserved core that controls most of the essential R- and FR-mediated responses. Thus, studies of structural change that occurred during their divergence are likely to reveal features that are critical for their individual functions.

Insights from Comparative Sequence Analyses

These analyses fall into two general categories, studies of natural variation within a single species and studies that sample more broadly across the phylogeny of plants. Natural populations of most species harbor extensive variation, and particularly where genomic and genetic resources are also available, they offer a useful set of genetic polymorphisms for study (e.g., Alonso-Blanco and Koornneef, 2000; Shindo et al., 2005; Buckler et al., 2009; McMullen et al., 2009). Studies of natural variation have been used to map quantitative trait loci controlling responses to light, dark, and cold in Arabidopsis (Yanovsky et al., 1997; Borevitz et al., 2002; Meng et al., 2008), to identify accessions that vary in responses to R or FR light (Maloof et al., 2001; Botto and Smith, 2002; Filiault et al., 2008) or in phytochrome activities (Eichenberg et al., 2000b), to infer a role for phyB in chromatin compaction (Tessadori et al., 2009), and to investigate the basis of plastic responses to shifts in the R:FR ratio (Brock et al., 2007). Natural variation in phytochrome responses has been detected in other species, including barley (Hordeum vulgare; Biyashev et al., 1997), oat (Avena sativa; Hou and Simpson, 1993), and Plantago lanceolata (Van Hinsberg, 1998), and single nucleotide polymorphisms at PHYB are candidates for causal linkage with clinal variation in bud set in Populus tremula (Ingvarsson et al., 2006). Several recent studies of candidate genes from multiple accessions have linked PHYC or PHYD variation to flowering time and/or morphological variation in Arabidopsis and millet Pennistum glaucum (Balasubramanian et al., 2006; Samis et al., 2008; Ehrenreich et al., 2009; Saïdou et al., 2009) and have identified geographic structuring at PHYA and PHYE in Cardamine nipponica (Ikeda et al., 2008, 2009). The ultimate goal of most of these studies is to link traits to genes, and they provide insight into how light signaling works in natural environments (Maloof et al., 2000). Additionally, they contribute to our understanding of phytochrome structural-functional models (e.g., Maloof et al., 2001; Filiault et al., 2008). For example, a polymorphism discovered in a sequence screen of natural PHYB alleles is associated with variation in response to R (Filiault et al., 2008), and the PHYA sequence in a natural mutant with reduced sensitivity to FR, Lm-2, has a single amino acid polymorphism at position 548 that leads to greater stability of the phyA holoprotein (Maloof et al., 2001). The change in FR sensitivity results from a M548T mis-sense mutation in the tongue region of the PHY domain, a region of Synechocystis Cph1 that seals the chromophore pocket and stabilizes Pfr (Essen et al., 2008). Mutation of the same residue in PHYB reduces sensitivity to low fluence R (Maloof et al., 2001). The Met at this position is deeply conserved across embryophytes and is also shared by Mesotaenium caldariorum and Mougeotia scalaris (zygnematalean green algae) but not by prokaryotes or fungi.

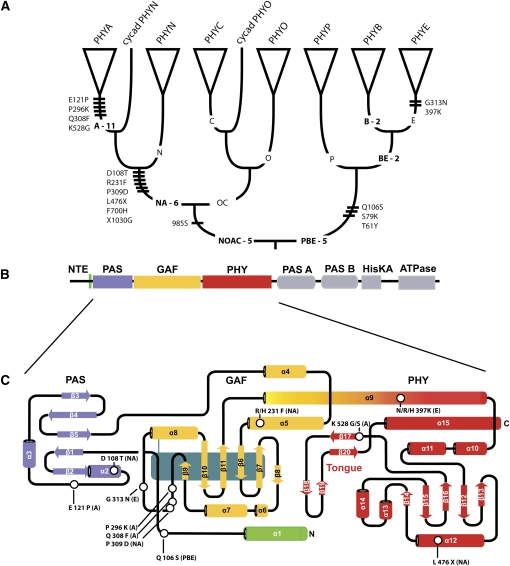

Comparative sequence analyses that sample widely across plants are useful for finding amino acid substitutions that may represent structural changes underlying the distinctive functions of duplicate genes or of genes in different species. In particular, tree-based approaches can bring to light substitutions that were fixed or under positive selection along the branches leading to the PHYA and PHYB clades (Figure 3A), which may represent structural changes underlying their separate functions. Using the branch-site test (Yang and Nielsen, 2002), Mathews et al. (2003) detected an episode of positive selection in the photosensory domain of PHYA early in the history of angiosperms. The test identified several amino acid sites with a high posterior probability of being under positive selection along the branch leading to all PHYA in a phylogeny of PHYA and PHYC sequences from across flowering plants. Site-directed mutagenesis of one of these residues from Val to Thr, the character state found in PHYC, leads to reduced photochromicity, suggesting that in phyA, the Val at this position is important for photoconversion between Pr and Pfr (E. Levesque and S. Mathews, unpublished data).

Figure 3.

Location by Branch and Domain of Positively Selected Amino Acid Sites in Seed Plant Phytochromes.

(A) Summary seed plant phytochrome tree. Hatch marks on a branch represent amino acid sites inferred to have been subject to positive selection along that branch using the branch-site test (Zhang et al., 2005). Numbers by branch labels indicate how many radical amino acid changes map to a particular branch in the tree using a parsimony-based approach (Maddison and Maddison, 2003). Sequence alignments for the branch-site tests are provided in Supplemental Data Sets 2 to 4 online.

(B) Domain structure of Arabidopsis PHYA. The N-terminal PAS, GAF, and PHY domains of plant PHY and Synechocystis Cph1 are homologous. The N-terminal extension (NTE) and the HKRD are unique to plant PHY. It is unclear whether plant PHYs have a helix comparable to α 1 in Cph1.

(C) Topology of the photosensory module of Synechocystis Cph1. Sites inferred to be under positive selection in seed plant phytochromes (open circles) are clustered in the region of the knot that forms the interface between the PAS and GAF domains. A, NA, PBE, and E refer to the branch of the phytochrome phylogeny on which a site was inferred to be under selection; X indicates an amino acid site at which the residue is variable.

Tests using an alignment of full-length sequences that includes representatives of all groups of living gymnosperms provide greater insight into structural changes that occurred during the divergence of PHYA from PHYB. Figure 3A summarizes findings from analyses using an updated version of the branch-site test (Zhang et al., 2005) and from mapping nonconservative amino acid changes on the tree using a parsimony-based approach (Maddison and Maddison, 2003). Each hatch mark on a branch represents an amino acid site that is inferred, based on the inferred ratio of nonsynonymous to synonymous changes, to have been subject to positive selection along that branch. Each number on a branch indicates how many radical amino acid changes map to that branch (see Supplemental Table 1 online, which gives the coordinates of the selected and radical replacement sites). Only those changes leading to character states that are reasonably conserved in the derivative clades are counted; that is, these are changes to character states that distinguish different genes. The pattern of these two types of event on the tree suggests that the preponderance of innovation occurring during the divergence of PHYA and PHYA-related proteins from PHYB and PHYB-related proteins occurred in the PHYN/A/O/C lineage. This is very consistent with the unique function of phyA among the five Arabidopsis phytochromes (Figure 1) and with the fact that phyB mediates responses that apparently were established very early in the history of land plants, such as R-induced, FR-reversible germination (Mathews, 2006). It is also consistent with the low levels of nucleotide diversity that have been observed at PHYB in Arabidopsis and C. nipponica (Filiault et al., 2008; Mathews and McBreen, 2008; Ikeda et al., 2009), at PHYP in P. sylvestris (García-Gil et al., 2003), and with the relatively short branches in the PHYB clade (Figure 2), data which suggest that evolution at PHYB is relatively constrained. Previous tests for selection in phytochrome gene trees relied on subsets of the seed plant phylogeny or the genes (Yang and Nielsen, 2002; Mathews et al., 2003). While Mathews et al. detected selection on the branch leading to angiosperm PHYA, the inclusion of data from other seed plants in these analyses reveals that adaptive evolution began before the radiation of living seed plants and proceeded sequentially across three nodes in the tree (Figure 3A). This provides a molecular parallel to morphological evolution in embryophytes, where the changes leading to important innovations, such as leaves, are distributed across a nested series of nodes (Donoghue, 2005). It is notable that there was considerable sequence evolution at PHYA after angiosperms split from other living seed plants, since this may have led to significant functional divergence between angiosperm PHYA and its PHYN, its ortholog in gymnosperms. It also suggests that divergence after gene duplication may be strongly impacted by speciation (see also Vendetti and Pagel, 2009).

SYNTHESIS OF FUNCTIONAL, EVOLUTIONARY, AND STRUCTURAL DATA

Both the branch-site test and the character mapping exercise identify the sequence coordinates of change, and these can be evaluated in the light of crystal structures that have recently been presented (Wagner et al., 2005, 2007; Yang et al., 2007, 2008; Cornilescu et al., 2008; Essen et al., 2008; Ulijasz et al., 2010) and can be compared with known mutants. Currently, high-resolution structures of the photosensory core of prokaryotic phytochromes are available; this region is homologous with the sensory module of plant phytochromes (Montgomery and Lagarias, 2002; Lamparter, 2004; Karniol et al., 2005) and consists of PAS, GAF, and PHY domains (Figure 3B). It is necessary for photoreversibility (Rockwell et al., 2006) and is sufficient for signaling when fused with dimerization and nuclear localization signals (Matsushita et al., 2003; Oka et al., 2004). The N-terminal extension (Figure 3B) is unique to phytochromes in embryophytes and their algal relatives; it is present in the phytochromes of zygnemetalean green alga, which diverge from the tree before Coleochaetales and Charales (the closest algal relatives of embryophytes; Delwiche et al., 2004) but is not present in prokaryotic phytochromes, and no crystal structure for this region is available. It is a region that in PHYA may harbor sites important for protein stability and spectral integrity and in PHYB that are important for efficient signaling (Quail, 1997; Mateos et al., 2006; Trupkin et al., 2006; Kneissl et al., 2008; Oka et al., 2008). The C-terminal regions of plant PHY and of those prokaryotic PHY that have been sequenced are not homologous (Lamparter, 2004; Mathews, 2006); in green plants, this region comprises two PAS and single His kinase and ATPase domains (Figure 3B), the latter two domains form the core of the His kinase–related domain (HKRD; Rockwell et al., 2006). The PAS repeats and HKRD contain sites necessary for dimerization and nuclear localization (Quail, 1997; Chen et al., 2003) and for modulating phytochrome signaling (Krall and Reed, 2000; Matsushita et al., 2003; Oka et al., 2004; Müller et al., 2009). Sequence conservation among the photosensory cores of plant and Synechocystis 6803 Cph1 phytochromes facilitates their alignment (Essen et al., 2008), and the alignment serves as a preliminary basis for relating positions in plant phytochromes to Cph1 structural elements (Figure 3C). The following paragraphs highlight sites of sequence change that may have had important roles in the divergence of PHYA and PHYB. The discussion is organized according to the branches in the amino acid phylogeny where the episodes of positive selection and/or radical replacement apparently occurred (Figure 3A).

Changes on the PBE and NOAC Branches

The deepest split in the gene tree leads to PHYP/B/E sequences on the one hand and PHYN/O/A/C sequences on the other (Figure 3A). Three of the four sites indicating positive selection after this split occur along the PBE branch. Two of these are in the N-terminal extension; the third occurs in the PAS domain (between α 1 and β 1), and it is likely to be in the trefoil knot region that forms the interface between the PAS and GAF domains (Figure 3C). Recent screens for phyB mis-sense mutations indicate that the knot region harbors residues that are important for phyB signaling (Oka et al., 2008); in particular, sites necessary for binding to the bHLH transcription factor PHYTOCHROME-INTERACTING-FACTOR3 are clustered in this region (Kikis et al., 2009). The fourth site giving a signal of adaptive evolution after this split occurs along the NOAC branch (985S; Figure 3); it lies in the HKRD between the HisKA and HATPase domains. Müller et al. (2009) recently demonstrated that a phyA mutation in the HisKA domain alters phyA-specific light signaling through EID1.

This period of divergence in the history of phytochromes also is notable for the accumulation of radical amino acid replacements, one of which occurs in the N-terminal extension (V35D, on the NOAC branch) and two of which occur in the HKRD in the region that is necessary for dimerization (S1076E on NOAC and D1110W on PBE; see Supplemental Table 1 online). Together, the observations suggest that early in the divergence of PHYA and PHYB, evolution in interactions with signaling partners may have been important. Other radical replacements that occurred during this historical interval are dispersed across the molecule, including a pair in GAF domain β -sheets that form the chromophore pocket (E379G and K394M on PBE).

Changes on the NA and A Branches

The next major event in the gene family is the split of PHYN/A and PHYO/C, which also occurred deep in the history of seed plants, before the origin of the extant groups (cycads, Ginkgo, conifers, and gnetophytes). This split was followed by remarkable sequence change in the PHYN/A lineage (Figure 3A). The preponderance of sites that give a signal of positive selection in the PHYN/A lineage occur in the PAS and GAF domains and are interesting in that they map onto, or very close to, known mutants. The two PAS domain sites, D108T and E121P, occur between α 2 and α 3 (Figure 3C); D108T occurs at the same position as a loss-of-function mutation in oat phyA (Quail et al., 1995) and two residues away from an Arabidopsis mutant with reduced protein stability (Xu et al., 1995). One of the two GAF α 5 sites, R231F, is two residues away from the eid4 mutant, which is hypersensitive to FR and has increased stability in light (Dieterle et al., 2005). Three residues map to the GAF loop, two of which when mutated in pea or oat, lead to a blue shift in the absorption maximum or to reduced rate of chromophore ligation, respectively (Figure 3C; Deforce et al., 1993; Kim et al., 2007). A positively selected site in the PHY domain (K528G on the A branch) is in β 17 of the tongue region that closes the chromophore pocket and stabilizes Pfr (Essen et al., 2008). A phyB mutation in β 17 causes loss of photoreversibility and enhanced light sensitivity (Kretsch et al., 2000). The highest number of radical amino acid replacements map to the A branch, followed by the NA and NOAC branches (Figure 3A), and many of these involve changes in charge that may influence protein–chromophore and/or protein–protein interactions. A study of the chromophore requirements of phyA and phyB suggests that tight binding between PHYA and the bilin D-ring may be required for phyA-specific biological activity (Hanzawa et al., 2002). Together, the data suggest that innovation leading to the distinctive spectral sensitivity of phyA and perhaps its lability in light may have occurred after the split of PHYN/A and PHYO/C.

Changes on the BE, B, and E Branches

Evolution in the PHYP/B/E lineage, by contrast, appears to be more constrained throughout the radiation of seed plants, by measures both of adaptive evolution and the accumulation of radical replacements. After the episodes of selection and radical replacement on PBE, few sites appear to have been targets of selection or radical replacement until after the split of PHYB and PHYE (Figure 3A). The PHYB/E split occurred early in the history of living angiosperms and was followed by an episode of selection at PHYE, acting on one site in the GAF loop and on one site in α 9, the long helix connecting the GAF and PHY domains (Figure 3C). The GAF loop residue lies between two oat phyA mutants, both of which lead to an 8-nm blue shift (Kim et al., 2007); thus, it is possible that the PHYE change at this position contributed to the blue shift in the absorption maximum of PHYE relative to that of PHYB (Eichenberg et al., 2000a). The split between PHYB and PHYE occurred early in the history of living angiosperms, since PHYE is present in Austrobaileyales but has not been detected in water lilies or Amborella; however, this episode of selection cannot be precisely placed since full-length PHYE sequences are available from eudicots only.

Overall, the evolutionary pattern of seed plant phytochromes is consistent with the hypothesis that functions controlled by phyB were established prior to the origin of seed plants and have been conserved throughout their history. R-mediated development in the LFR mode is found across embryophytes and in Charales; elements of shade avoidance also are widespread, occurring as deeply in the tree as Charales (Mathews, 2006). The remarkable innovation in the PHYN/A lineage is more suggestive of adaptive change, possibly in response to the evolution of forests and the value of possessing a mechanism to counteract phyB activities under canopies and leaf litter (McCormac et al., 1992; Reed et al., 1994; Yanovsky et al., 1995; Mazzella et al., 1997; Cerdán et al., 1999; Devlin et al., 2003; Mathews et al., 2003; von Wettberg and Schmitt, 2005).

ADDITIONAL PHYTOCHROMES: AN EXPANDED ROLE FOR THE PHYTOCHROME SYSTEM IN ENVIRONMENTAL SENSING

Branch lengths in gene trees and explicit tests suggest that the evolution of PHYC-E is less constrained than that of PHYA and PHYB (Figure 2; Mathews and Sharrock, 1997; Alba et al., 2000; White et al., 2004; Balasubramanian et al., 2006; García-Gil, 2008; Mathews and McBreen, 2008; Ikeda et al., 2009). Perhaps consistent with this is the fact that null mutants of these loci in Arabidopsis were not easily identified in genetic screens and the phenotypes of the monogenic mutants are not readily apparent (Aukerman et al., 1997; Devlin et al., 1998; Franklin et al., 2003; Monte et al., 2003). However, PHYC, D, and E have been retained much longer than the expected half-life of duplicate genes of ∼ 3 to 7 million years (Lynch and Conery, 2000). PHYO/C originated at least 330 million years ago (Magallón and Sanderson, 2005) and appears to be retained in most seed plants, although it has not been detected in gnetophytes (Schmidt and Schneider-Poetsch, 2002; Mathews, 2006) and legumes (Lavin et al., 1998; Quecini et al., 2008) and is not present in P. trichocarpa (Howe et al., 1998; Tuskan et al., 2006). PHYE also is ancient, older than eudicots, which originated at least 125 million years ago (Magallón and Sanderson, 2005); while there are a number of lineages that lack PHYE (e.g., monocots, Piperales, and Caryophyllales), it is broadly distributed in flowering plants. PHYD, the sister of PHYB, originated on the branch to Brassicaceae, ∼ 45 million years ago and apparently has been retained in most family members (Mathews and McBreen, 2008).

What is the major role of these additional light-stable phytochromes? In light-grown plants, they are present throughout development and throughout the plant, where protein levels are about half those of phyB (Sharrock and Clack, 2002). Several plant species have two copies of PHYB (or P), including P. trichocarpa, maize, and members of Pinaceae, Solanaceae, Fabaceae, and Piperaceae. In Arabidopsis, phyB is the principal mediator of R-mediated development and shade avoidance, whereas phyD appears to play a minor role in shade avoidance; phyD-1 is a naturally occurring mutant, suggesting that phyD is dispensable in some environments (Aukerman et al., 1997). However, a recent study showing that the phyD null but not phyAphyB lost the ability to adjust the chlorophyll a/b ratio in response to canopy shading (Boonman et al., 2009) suggests that in shade avoidance, phyD but not phyB controls this response. phyE also appears to be a minor player in shade avoidance (Devlin et al., 1998) and has a very limited role in FR-induced responses (Hennig et al., 2002). Together, phyD and phyE may be important for fine-tuning the magnitude of responses to the R:FR ratio in complex light environments (Ballaré, 2009). phyC appears to function as a weak R sensor in the control of seedling deetiolation, photoperiod perception, and in the modulation of other photoreceptors (Franklin et al., 2003; Monte et al., 2003).

It is possible that phyC-E have important roles that have been difficult to detect in typical laboratory experiments. Work by Halliday and Whitelam provided evidence that this may be the case, demonstrating that phyD and phyE have a more prominent role than phyB in controlling flowering under cool temperatures (Halliday and Whitelam, 2003; Halliday et al., 2003). Further evidence that the contributions of individual phytochromes are environmentally dependent comes from investigation of the effects of photoperiod and temperature on germination. These studies revealed a role for phyD in breaking cool-induced seed dormancy and in mediating the effects of photoperiod during seed maturation (Donohue et al., 2007). They further revealed that phyD is important in seed germination when seeds were matured (Dechaine et al., 2009) or imbibed (Heschel et al., 2008) under high temperatures, whereas phyE was important when seeds were imbibed in high temperatures followed by low temperatures (Heschel et al., 2008) or when matured under high temperatures (Dechaine et al., 2009). These data suggest that phyD and phyE contribute to the precision of responses to variable environments. Additionally, studies of variation in populations across a large spatial scale have linked clinal variation at PHYC with variation in flowering time (Balasubramanian et al., 2006; Saïdou et al., 2009), suggesting its role in photoperiod perception is relevant in natural environments.

It is interesting to note that phyC and phyE may not, in many cases, be acting alone, at least in Arabidopsis, where under some conditions they occur largely as heterodimers, predominantly with phyB; phyD also heterodimerizes with phyB (Figure 1; Sharrock and Clack, 2004; Clack et al., 2009). Notably, in the absence of phyB, phyC and phyE are largely destabilized or monomeric, respectively. Conversely, phyB may be predominantly homodimeric, and there is no evidence that phyA heterodimerizes (Clack et al., 2009). This suggests that the evolution of dimerization specificity has contributed to functional divergence of phyA and phyB. Moreover, it leaves open the possibility that the increased environmental sensitivity resulting from retention of phyC-E could be achieved largely through their partnerships with phyB. The retention of these additional phytochromes could be advantageous because they confer a greater flexibility on phyB-mediated sensing and signaling than could be controlled by phyB alone, which is evolving under constraints that are among the strongest of any acting on genes in Arabdiopsis (Mathews and McBreen, 2008). Such strategy would be analogous to that of large companies that upon finding it difficult to innovate, meet the challenge by acquiring small start-up companies.

CONCLUSIONS

Responsiveness to environmental signals is useful only if it is not lost when new environments are encountered, or when plant form or life histories change. Phytochromes provide a fascinating example of how a photoreceptor system imparts both stability and flexibility, as revealed in a synthesis of insights from functional and evolutionary studies. The discovery of a GAF domain site in phyA that alters photochromicity using tests for selection, and the identification of amino acid residues that impact light sensitivity in screens of natural variation, highlight the utility of synthesizing functional and evolutionary approaches. Rockwell et al. (2006) noted that the accumulation of mutant alleles and the availability of crystal structures form a powerful combination to assess phytochrome function. Comparative sequence analyses expand the repertoire of mutant alleles by revealing historic mutations that occurred during gene lineage splitting and divergence; these are likely to be locus-specific mutants. With insights from available crystallographic data, a subset of these mutants can be chosen for functional studies to test their importance and determine the molecular mechanism by which they might impact light perception and signaling. Finally, the fitness of these synthetic mutants can be investigated to test their implications for adaptive phenotypic change.

Supplemental Data

The following materials are available in the online version of this article.

Supplemental Table 1. Positively Selected and Radical Replacement Sites.

Supplemental Data Set 1. Amino Acid Alignment for Phylogenetic Tree Shown in Figure 2.

Supplemental Data Set 2. Alignment for Branch-Site Tests, All Branches but A and E.

Supplemental Data Set 3. Alignment for Branch-Site Tests, A Branch Only.

Supplemental Data Set 4. Alignment for Branch-Site Tests, E Branch Only.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

I thank the National Science Foundation (IBN-021449) and the Arnold Arboretum for financial support, Jo Mailliet and Jon Hughes for kindly providing the template for Figure 3C, Ethan Levesque and Uli Genick for technical assistance, Bob Sharrock, Andreas Hiltbrunner, and Christian Fankhauser for helpful discussions, and three anonymous reviewers for comments on this manuscript.

References

- Alba R., Kelmenson P.M., Cordonnier-Pratt M.M., Pratt L.H. (2000). The phytochrome gene family in tomato and the rapid differential evolution of this family in angiosperms. Mol. Biol. Evol. 17: 362–373 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alonso-Blanco C., Koornneef M. (2000). Naturally occurring variation in Arabidopsis: An underexploited resource for plant genetics. Trends Plant Sci. 5: 22–29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aukerman M.J., Hirschfeld M., Wester L., Weaver M., Clack T., Amasino R.M., Sharrock R.A. (1997). A deletion in the PHYD gene of the Arabidopsis Wassilewskija ecotype defines a role for phytochrome D in red/far-red light sensing. Plant Cell 9: 1317–1326 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bae G., Choi G. (2008). Decoding of light signals by plant phytochromes and their interacting proteins. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 59: 281–311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balasubramanian S., Sureshkumar S., Agrawal M., Michael T.P., Wessinger C., Maloof J.N., Clark R., Warthmann N., Chory J., Weigel D. (2006). The PHYTOCHROME C photoreceptor gene mediates natural variation in flowering and growth responses of Arabidopsis thaliana. Nat. Genet. 38: 711–715 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballaré C., Scopel A.L., Sanchez R. (1990). Far-red radiation reflected from adjacent leaves: An early signal of competition in plant canopies. Science 247: 329–332 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballaré C.L. (2009). Illuminated behaviour: Phytochrome as a key regulator of light foraging and plant anti-herbivore defence. Plant Cell Environ. 32: 713–725 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballaré C.L., Casal J.J., Kendrick R.E. (1991). Responses of light-grown wild-type and long-hypocotyl mutant cucumber seedlings to natural and simulated shade light. Photochem. Photobiol. 54: 819–826 [Google Scholar]

- Biyashev R.M., Ragab R.A., Maughan P.J., Saghai Maroof M.A. (1997). Molecular mapping, chromosomal assignment, and genetic diversity analysis of phytochrome loci in barley (Hordeum vulgare). J. Hered. 88: 21–26 [Google Scholar]

- Boonman A., Prinsen E., Voesenek L.A.C.J., Pons T.L. (2009). Redundant roles of photoreceptors and cytokinins in regulating photosynthetic acclimation to canopy density. J. Exp. Bot. 60: 1179–1190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borevitz J.O., Maloof J.N., Lutes J., Dabi T., Redfern J.L., Trainer G.T., Werner J.D., Asami T., Berry C.C., Weigel D., Chory J. (2002). Quantitative trait loci controlling light and hormone response in two accessions of Arabidopsis thaliana. Genetics 160: 683–696 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Botto J.F., Sanchez R.A., Whitelam G.C., Casal J.J. (1996). Phytochrome A mediates the promotion of seed germination by very low fluences of light and canopy shade light in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 110: 439–444 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Botto J.F., Smith H. (2002). Differential genetic variation in adaptive strategies to a common environmental signal in Arabidopsis accessions: Phytochrome-mediated shade avoidance. Plant Cell Environ. 25: 53–63 [Google Scholar]

- Brock M.T., Tiffin P., Weinig C. (2007). Sequence diversity and haplotype associations with phenotypic responses to crowding: GIGANTEA affects fruit set in Arabidopsis thaliana. Mol. Ecol. 16: 3050–3062 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckler E.S., et al. (2009). The genetic architecture of maize flowering time. Science 325: 714–718 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casal J.J., Sanchez R.A., Yanovsky M.J. (1997). The function of phytochrome A. Plant Cell Environ. 20: 813–819 [Google Scholar]

- Castillon A., Shen H., Huq E. (2007). Phytochrome interacting factors: Central players in phytochrome-mediated light signaling networks. Trends Plant Sci. 12: 514–521 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cerdán P.D., Yanovsky M.J., Reymundo F.C., Nagatani A., Staneloni R.J., Whitelam G.C., Casal J.J. (1999). Regulation of phytochrome B signaling by phytochrome A and FHY1 in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 18: 499–507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen M., Schwab R., Chory J. (2003). Characterization of the requirements for localization of phytochrome B to nuclear bodies. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100: 14493–14498 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Childs K.L., Pratt L.H., Morgan P.W. (1991). Genetic regulation of development in Sorghum bicolor: VI. The ma3R allele results in abnormal phytochrome physiology. Plant Physiol. 97: 714–719 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clack T., Mathews S., Sharrock R.A. (1994). The phytochrome apoprotein family in Arabidopsis is encoded by five genes: the sequences and expression of PHYD and PHYE. Plant Mol. Biol. 25: 413–427 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clack T., Shokry A., Moffet M., Liu P., Faul M., Sharrock R.A. (2009). Obligate heterodimerization of Arabidopsis phytochromes C and E and interaction with the PIF3 basic helix-loop-helix transcription factor. Plant Cell 21: 786–799 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clapham D.H., Kolukisaoglu H.U., Larsson C.T., Qamaruddin M., Ekberg I., Wiegmann-Eirund C., Schneider-Poetsch H.A., von Arnold S. (1999). Phytochrome types in Picea and Pinus. Expression patterns of PHYA-related types. Plant Mol. Biol. 40: 669–678 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornilescu G., Ulijasz A.T., Cornilescu C.C., Markley J.L., Vierstra R.D. (2008). Solution structure of a cyanobacterial phytochrome GAF domain in the red-light-absorbing ground state. J. Mol. Biol. 383: 403–413 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dechaine J.M., Gardner G., Weinig C. (2009). Phytochromes differentially regulate seed germination responses to light quality and temperature cues during seed maturation. Plant Cell Environ. 32: 1297–1309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deforce L., Furuya M., Song P.S. (1993). Mutational analysis of the pea phytochrome A chromophore pocket: Chromophore assembly with apophytochrome A and photoreversibility. Biochemistry 32: 14165–14172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delwiche C.F., Andersen R.A., Bhattacharya D., Mishler B.D., McCourt R.C. (2004). Algal evolution and the early radiation of gree plants. Assembling the Tree of Life, Cracraft J., Donoghue M.J., (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; ), pp. 121–137 [Google Scholar]

- Devlin P.F., Patel S.R., Whitelam G.C. (1998). Phytochrome E influences internode elongation and flowering time in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 10: 1479–1487 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devlin P.F., Rood S.B., Somers D.E., Quail P.H., Whitelam G.C. (1992). Photophysiology of the elongated internode (ein) mutant of Brassica rapa: ein mutant lacks a detectable phytochrome B-like polypeptide. Plant Physiol. 100: 1442–1447 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devlin P.F., Yanovsky M.J., Kay S.A. (2003). A genomic analysis of the shade avoidance response in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 133: 1617–1629 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dieterle M., Bauer D., Büche C., Krenz M., Schäfer E., Kretsch T. (2005). A new kind of mutation in phytochrome A causes enhanced light sensitivity and alters degradation and subcellular partitioning of the photoreceptor. Plant J. 41: 146–161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiMichele W.A., Hook R.W., Beerbower R., Boy J.A., Gastaldo R.A., Hotton N., III, Phillips T.L., Scheckler S.E., Shear W.A., Sues H.-D. (1992). Paleozoic terrestrial ecosystems. Terrestrial Ecosystems through Time, Behrensmeyer A.K., Damuth J.D., DiMichele W.A., Potts R., Sues H.-D., Wing S.L., (Chicago: University of Chicago Press; ), pp. 205–325 [Google Scholar]

- Donoghue M.J. (2005). Key innovations, convergence, and success: Macroevolutionary lessons from plant phylogeny. Paleobiology 31: 77–93 [Google Scholar]

- Donohue K., Heschel M.S., Butler C.M., Barua D., Sharrock R.A., Whitelam G.C., Chiang G.C.K. (2007). Diversification of phytochrome contributions to germination as a function of seed-maturation environment. New Phytol. 177: 367–379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrenreich I., Hanzawa Y., Chou L., Roe J., Kover P., Purugganan M. (2009). Candidate gene association mapping of Arabidopsis flowering time. Genetics 183: 325–335 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eichenberg K., Baurle I., Paulo N., Sharrock R.A., Rudiger W., Schafer E. (2000a). Arabidopsis phytochromes C and E have different spectral characteristics from those of phytochromes A and B. FEBS Lett. 470: 107–112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eichenberg K., Hennig L., Martin A., Schäfer E. (2000b). Variation in dynamics of phytochrome A in Arabidopsis ecotypes and mutants. Plant Cell Environ. 23: 311–319 [Google Scholar]

- Essen L.-O., Mailliet J., Hughes J. (2008). The structure of a complete phytochrome sensory module in the Pr ground state. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 105: 14709–14714 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filiault D.L., Wessinger C.A., Dinneny J.R., Lutes J., Borevitz J.O., Weigel D., Chory J., Maloof J.N. (2008). Amino acid polymorphisms in Arabidopsis phytochrome B cause differential responses to light. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 105: 3157–3162 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flagel L.E., Wendel J.F. (2009). Gene duplication and evolutionary novelty in plants. New Phytol. 183: 557–564 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frankland B., Taylorson R. (1983). Light control of seed germination. Photomorphogenesis, Vol. 16A, Shropshire W., Mohr H., (Berlin: Springer-Verlag; ), pp. 428–456 [Google Scholar]

- Franklin K.A. (2008). Shade avoidance. New Phytol. 179: 930–944 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franklin K.A., Allen T., Whitelam G.C. (2007). Phytochrome A is an irradiance-dependent red light sensor. Plant J. 50: 108–117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franklin K.A., Davis S.J., Stoddart W.M., Vierstra R.D., Whitelam G.C. (2003). Mutant analyses define multiple roles for phytochrome C in Arabidopsis photomorphogenesis. Plant Cell 15: 1981–1989 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franklin K.A., Quail P.H. (2010). Phytochrome functions in Arabidopsis development. J. Exp. Bot. 61: 11–24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García-Gil M. (2008). Evolutionary aspects of functional and pseudogene members of the phytochrome gene family in Scots pine. J. Mol. Evol. 67: 222–232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García-Gil M.R., Mikkonen M., Savolainen O. (2003). Nucleotide diversity at two phytochrome loci along a latitudinal cline in Pinus sylvestris. Mol. Ecol. 12: 1195–1206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goosey L., Palecanda L., Sharrock R.A. (1997). Differential patterns of expression of the Arabidopsis PHYB, PHYD, and PHYE phytochrome genes. Plant Physiol. 115: 959–969 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halliday K.J., Koornneef M., Whitelam G.C. (1994). Phytochrome B and at least one other phytochrome mediate the accelerated flowering response of Arabidopsis thaliana L. to low red/far-red ratio. Plant Physiol. 104: 1311–1315 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halliday K.J., Salter M.G., Thingnaes E., Whitelam G.C. (2003). Phytochrome control of flowering is temperature sensitive and correlates with expression of the floral integrator FT. Plant J. 33: 875–885 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halliday K.J., Whitelam G.C. (2003). Changes in photoperiod or temperature alter the functional relationships between phytochromes and reveal roles for phyD and phyE. Plant Physiol. 131: 1913–1920 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanzawa H., Shinomura T., Inomata K., Kakiuchi T., Kinoshita H., Wada K., Furuya M. (2002). Structural requirement of bilin chromophore for the photosensory specificity of phytochromes A and B. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99: 4725–4729 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hennig L., Stoddart W.M., Dieterle M., Whitelam G.C., Schafer E. (2002). Phytochrome E controls light-induced germination of Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 128: 194–200 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heschel M.S., Butler C.M., Barua D., Chiang G.C.K., Wheeler A., Sharrock R.A., Whitelam G.C., Donohue K. (2008). New roles of phytochromes during seed germination. Int. J. Plant Sci. 169: 531–540 [Google Scholar]

- Heyer A., Gatz C. (1992). Isolation and characterization of a cDNA-clone coding for potato type B phytochrome. Plant Mol. Biol. 20: 589–600 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou J., Simpson G. (1993). Germination response to phytochrome depends on specific dormancy states in wild oat (Avena fatua). Can. J. Bot. 71: 1528–1532 [Google Scholar]

- Howe G.T., Bucciaglia P.A., Hackett W.P., Furnier G.R., Cordonnier-Pratt M.M., Gardner G. (1998). Evidence that the phytochrome gene family in black cottonwood has one PHYA locus and two PHYB loci but lacks members of the PHYC/F and PHYE subfamilies. Mol. Biol. Evol. 15: 160–175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudson M., Robson P.R., Kraepiel Y., Caboche M., Smith H. (1997). Nicotiana plumbaginifolia hlg mutants have a mutation in a PHYB-type phytochrome gene: They have elongated hypocotyls in red light, but are not elongated as adult plants. Plant J. 12: 1091–1101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikeda H., Fujii N., Setoguchi H. (2009). Molecular evolution of phytochromes in Cardamine nipponica (Brassicaceae) suggests the involvement of PHYE in local adaptation. Genetics 182: 603–614 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikeda H., Senni K., Fujii N., Setoguchi H. (2008). Consistent geographic structure among multiple nuclear sequences and cpDNA polymorphisms of Cardamine nipponica Franch. et Savat. (Brassicaceae). Mol. Ecol. 17: 3178–3188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingvarsson P.K., Garcia M.V., Hall D., Luquez V., Jansson S. (2006). Clinal variation in phyB2, a candidate gene for day-length-induced growth cessation and bud set, across a latitudinal gradient in European aspen (Populus tremula). Genetics 172: 1845–1853 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiao Y., Lau O.S., Deng X.W. (2007). Light-regulated transcriptional networks in higher plants. Nat. Rev. Genet. 8: 217–230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karniol B., Wagner J.R., Walker J.M., Vierstra R.D. (2005). Phylogenetic analysis of the phytochrome superfamily reveals distinct microbial subfamilies of photoreceptors. Biochem. J. 392: 103–116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerckhoffs L.H.J., Kelmenson P.M., Schreuder M.E.L., Kendrick C.I., Kendrick R.E., Hanhart C.J., Koornneef M., Pratt L.H., Cordonnier-Pratt M.M. (1999). Characterization of the gene encoding the apoprotein of phytochrome B2 in tomato, and identification of molecular lesions in two mutant alleles. Mol. Gen. Genet. 261: 901–907 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kikis E.A., Oka Y., Hudson M.E., Nagatani A., Quail P.H. (2009). Residues clustered in the sight-sensing knot of PHYTOCHROME B are necessary for conformer-specific binding to signaling partner PIF3. PLoS Genet. 5: e1000352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J.-I., Han Y.-J., Song P.-S. (2007). Isolated nucleic acid molecule encoding the modified phytochrome A. U.S. Patent 7285652. Korea Kumho Petrochemical. [Google Scholar]

- Kircher S., Gil P., Kozma-Bognár L., Fejes E., Speth V., Husselstein-Muller T., Bauer D., Ádám E., Schäfer E., Nagy F. (2002). Nucleocytoplasmic partitioning of the plant photoreceptors phytochrome A, B, C, D, and E is regulated differentially by light and exhibits a diurnal rhythm. Plant Cell 14: 1541–1555 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiss J.Z., Mullen J.L., Correll M.J., Hangarter R.P. (2003). Phytochromes A and B mediate red-light-induced positive phototropism in roots. Plant Physiol. 131: 1411–1417 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kneissl J., Shinomura T., Furuya M., Bolle C. (2008). A rice phytochrome A in Arabidopsis: The role of the n-terminus under red and far-red light. Mol. Plant 1: 84–102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krall L., Reed J.W. (2000). The histidine kinase-related domain participates in phytochrome B function but is dispensable. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97: 8169–8174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kretsch T., Poppe C., Schäfer E. (2000). A new type of mutation in the plant photoreceptor phytochrome B causes loss of photoreversibility and an extremely enhanced light sensitivity. Plant J. 22: 177–186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamparter T. (2004). Evolution of cyanobacterial and plant phytochromes. FEBS Lett. 273: 1–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavin M., Eshbaugh E., Hu J., Mathews S., Sharrock R. (1998). Monophyletic subgroups of the tribe Millettieae (Leguminosae) as revealed by phytochrome nucleotide sequence data. Am. J. Bot. 85: 412–433 [Google Scholar]

- Lynch M., Conery J.S. (2000). The evolutionary fate and consequences of duplicate genes. Science 290: 1151–1155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maddison D.R., Maddison W.P. (2003). MacClade 4.06 Analysis of Phylogeny and Character Evolution. (Sunderland, MA: Sinauer Associates; ). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magallón S.A., Sanderson M.J. (2005). Angiosperm divergence times: The effect of genes, codon positions, and time constraints. Evolution 59: 1653–1670 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maloof J.N., Borevitz J.O., Dabi T., Lutes J., Nehring R.B., Redfern J.L., Trainer G.T., Wilson J.M., Asami T., Berry C.C., Weigel D., Chory J. (2001). Natural variation in light sensitivity of Arabidopsis. Nat. Genet. 29: 441–446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maloof J.N., Borevitz J.O., Weigel D., Chory J. (2000). Natural variation in phytochrome signaling. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 11: 523–530 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mancinelli A.L. (1994). The physiology of phytochrome action. Photomorphogenesis in Plants, 2nd ed, Kendrick R.E., Kronenberg G.H.M., (Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers; ), pp. 211–269 [Google Scholar]

- Mateos J.L., Luppi J.P., Ogorodnikova O.B., Sineshchekov V.A., Yanovsky M.J., Braslavsky S.E., Gärtner W., Casal J.J. (2006). Functional and biochemical analysis of the N-terminal domain of phytochrome A. J. Biol. Chem. 281: 34421–34429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathews S. (2006). Phytochrome-mediated development in land plants: Red light sensing evolves to meet the challenges of changing light environments. Mol. Ecol. 15: 3483–3503 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathews S., Burleigh J.G., Donoghue M.J. (2003). Adaptive evolution in the photosensory domain of phytochrome A in early angiosperms. Mol. Biol. Evol. 20: 1087–1097 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathews S., Clements M.D., Beilstein M.A. (2010). A duplicate gene rooting of seed plants and the phylogenetic position of flowering plants. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 365: 383–395 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathews S., Lavin M., Sharrock R.A. (1995). Evolution of the phytochrome gene family and its utility for phylogenetic analyses of angiosperms. Ann. Mo. Bot. Gard. 82: 296–321 [Google Scholar]

- Mathews S., McBreen K. (2008). Phylogenetic relationships of B-related phytochromes in the Brassicaceae: Redundancy and the persistence of phytochrome D. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 49: 411–423 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathews S., Sharrock R.A. (1997). Phytochrome gene diversity. Plant Cell Environ. 20: 666–671 [Google Scholar]

- Matsushita T., Mochizuki N., Nagatani A. (2003). Dimers of the N-terminal domain of phytochrome B are functional in the nucleus. Nature 424: 571–574 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazzella M.A., Alconada Magliano T.M., Casal J.J. (1997). Dual effect of phytochrome A on hypocotyl growth under continuous red light. Plant Cell Environ. 20: 261–267 [Google Scholar]

- McCormac A.C., Whitelam G.C., Boylan M.T., Quail P.H., Smith H. (1992). Contrasting responses of etiolated and light-adapted seedlings to red:far-red ratio: A comparison of wild type, mutant and transgenic plants has revealed differential functions of members of the phytochrome family. J. Plant Physiol. 140: 707–714 [Google Scholar]

- McMullen M.D., et al. (2009). Genetic properties of the maize nested association mapping population. Science 325: 737–740 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng P.-H., Macquet A., Loudet O., Marion-Poll A., North H.M. (2008). Analysis of natural allelic variation controlling Arabidopsis thaliana seed germinability in response to cold and dark: Identification of three major quantitative trait loci. Mol. Plant 1: 145–154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monte E., Alonso J.M., Ecker J.R., Zhang Y., Li X., Young J., Austin-Phillips S., Quail P.H. (2003). Isolation and characterization of phyC mutants in Arabidopsis reveals complex crosstalk between phytochrome signaling pathways. Plant Cell 15: 1962–1980 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery B.L., Lagarias J.C. (2002). Phytochrome ancestry: Sensors of bilins and light. Trends Plant Sci. 7: 357–366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller R., Fernández A.P., Hiltbrunner A., Schäfer E., Kretsch T. (2009). The histidine kinase-related domain of Arabidopsis phytochrome A controls the spectral sensitivity and the subcellular distribution of the photoreceptor. Plant Physiol. 150: 1297–1309 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagatani A., Reed J.W., Chory J. (1993). Isolation and initial characterization of Arabidopsis mutants that are deficient in phytochrome A. Plant Physiol. 102: 269–277 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oka Y., Matsushita T., Mochizuki N., Quail P.H., Nagatani A. (2008). Mutant screen distinguishes between residues necessary for light-signal perception and signal transfer by phytochrome B. PLoS Genet. 4: e1000158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oka Y., Matsushita T., Mochizuki N., Suzuki T., Tokutomi S., Nagatani A. (2004). Functional analysis of a 450-amino acid N-terminal fragment of phytochrome B in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 16: 2104–2116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parks B.M., Quail P.H. (1993). hy8, a new class of Arabidopsis long hypocotyl mutants deficient in functional phytochrome A. Plant Cell 5: 39–48 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parks B.M., Quail P.H., Hangarter R.P. (1996). Phytochrome A regulates red-light induction of phototropic enhancement in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 110: 155–162 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pratt L.H., Cordonnier-Pratt M.M., Hauser B., Caboche M. (1995). Tomato contains two differentially expressed genes encoding B-type phytochromes, neither of which can be considered an ortholog of Arabidopsis phytochrome B. Planta 197: 203–206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quail P.H. (1997). An emerging molecular map of the phytochromes. Plant Cell Environ. 20: 657–665 [Google Scholar]

- Quail P.H., Boylan M.T., Parks B.M., Short T.W., Xu Y., Wagner D. (1995). Phytochromes: Photosensory perception and signal transduction. Science 268: 675–680 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quecini V., Zucchi M., Pinheiro J., Vello N. (2008). In silico analysis of candidate genes involved in light sensing and signal transduction pathways in soybean. Plant Biotechnol. Rep. 2: 59–73 [Google Scholar]

- Reed J.W., Nagatani A., Elich T.D., Fagan M., Chory J. (1994). Phytochrome A and phytochrome B have overlapping but distinct functions in Arabidopsis development. Plant Physiol. 104: 1139–1149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed J.W., Nagpal P., Poole D.S., Furuya M., Chory J. (1993). Mutations in the gene for the red/far-red light receptor phytochrome B alter cell elongation and physiological responses throughout Arabidopsis development. Plant Cell 5: 147–157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robson P., Whitelam G.C., Smith H. (1993). Selected components of the shade-avoidance syndrome are displayed in a normal manner in mutants of Arabidopsis thaliana and Brassica rapa deficient in phytochrome B. Plant Physiol. 102: 1179–1184 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rockwell N.C., Su Y.-S., Lagarias J.C. (2006). Phytochrome structure and signaling mechanisms. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 57: 837–858 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saïdou A.-A., Mariac C., Luong V., Pham J.-L., Bezancon G., Vigouroux Y. (2009). Association studies identify natural variation at PHYC linked to flowering time and morphological variation in pearl millet. Genetics 182: 899–910 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salter M.G., Franklin K.A., Whitelam G.C. (2003). Gating of the rapid shade-avoidance response by the circadian clock in plants. Nature 426: 680–683 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samis K.E., Heath K.D., Stinchcombe J.R. (2008). Discordant longitudinal clines in flowering time and PHYTOCHROME C in Arabidopsis thaliana. Evolution 62: 2971–2983 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider-Poetsch H.A.W., Kolukisaoglu U., Clapham D.H., Hughes J., Lamparter T. (1998). Non angiosperm phytochromes and the evolution of vascular plants. Physiol. Plant. 102: 612–622 [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt M., Schneider-Poetsch H.A.W. (2002). The evolution of gymnosperms redrawn by phytochrome genes: The Gnetae appear at the base of gymnosperms. J. Mol. Evol. 54: 715–724 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharrock R., Clack T. (2004). Heterodimerization of type II phytochromes in Arabidopsis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101: 11500–11505 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharrock R.A., Clack T. (2002). Patterns of expression and normalized levels of the five Arabidopsis phytochromes. Plant Physiol. 130: 442–456 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharrock R.A., Quail P.H. (1989). Novel phytochrome sequences in Arabidopsis thaliana: Structure, evolution, and differential expression of a plant regulatory photoreceptor family. Genes Dev. 3: 1745–1757 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheehan M.J., Kennedy L.M., Costich D.E., Brutnell T.P. (2007). Subfunctionalization of PhyB1 and PhyB2 in the control of seedling and mature plant traits in maize. Plant J. 49: 338–353 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shindo C., Aranzana M.J., Lister C., Baxter C., Nicholls C., Nordborg M., Dean C. (2005). Role of FRIGIDA and FLOWERING LOCUS C in determining variation in flowering time of Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 138: 1163–1173 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shinomura T., Uchida K., Furuya M. (2000). Elementary processes of photoperception by phytochrome A for high-irradiance response of hypocotyl elongation in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 122: 147–156 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith H. (1982). Light quality, photoperception, and plant strategy. Annu. Rev. Plant Physiol. 33: 481–518 [Google Scholar]

- Smith H. (1995). Physiological and ecological function within the phytochrome family. Annu. Rev. Plant Physiol. Plant Mol. Biol. 46: 289–315 [Google Scholar]

- Smith H., Whitelam G.C. (1990). Phytochrome, a family of photoreceptors with multiple physiological roles. Plant Cell Environ. 13: 695–707 [Google Scholar]

- Stamatakis A. (2006). RAxML-VI-HPC: Maximum likelihood-based phylogenetic analyses with thousands of taxa and mixed models. Bioinformatics 22: 2688–2690 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sterck L., Rombauts S., Vandepoele K., Rouz È.P., Van de Peer Y. (2007). How many genes are there in plants (... and why are they there)?. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 10: 199–203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takano M., Inagaki N., Xie X., Kiyota S., Baba-Kasai A., Tanabata T., Shinomura T. (2009). Phytochromes are the sole photoreceptors for perceiving red/far-red light in rice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 106: 14705–14710 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takano M., Inagaki N., Xie X., Yuzurihara N., Hihara F., Ishizuka T., Yano M., Nishimura M., Miyao A., Hirochika H., Shinomura T. (2005). Distinct and cooperative functions of phytochromes A, B, and C in the control of deetiolation and flowering in rice. Plant Cell 17: 3311–3325 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takano M., Kanegae H., Shinomura T., Miyao A., Hirochika H., Furuya M. (2001). Isolation and characterization of rice phytochrome A mutants. Plant Cell 13: 521–534 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tepperman J.M., Hwang Y.-S., Quail P.H. (2006). phyA dominates in transduction of red-light signals to rapidly responding genes at the initiation of Arabidopsis seedling de-etiolation. Plant J. 48: 728–742 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tessadori F., et al. (2009). Phytochrome B and histone deacetylase 6 control light-induced chromatin compaction in Arabidopsis thaliana. PLoS Genet. 5: . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tokuhisa J.G., Daniels S.M., Quail P.H. (1985). Phytochrome in green tissue: Spectral and immunochemical evidence for two distinct molecular species of phytochrome in light-grown Avena sativa L. Planta 164: 321–332 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trupkin S.A., Debrieux D., Hiltbrunner A., Fankhauser C., Casal J.J. (2006). The serine-rich N-terminal region of Arabidopsis phytochrome A is required fro protein stability. Plant Mol. Biol. 63: 669–678 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuskan G.A., et al. (2006). The genome of black cottonwood, Populus trichocarpa (Torr. & Gray). Science 313: 1596–1604 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ulijasz A.T., Cornilescu G., Cornilescu C.C., Zhang J., Rivera M., Markley J.L., Vierstra R.D. (2010). Structural basis for the photoconversion of a phytochrome to the activated Pfr form. Nature 463: 250–254 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Hinsberg A. (1998). Maternal and ambient environmental effects of light on germination in Plantago lanceolata: Correlated responses to selection on leaf length. Funct. Ecol. 12: 825–833 [Google Scholar]

- van Tuinen A., Kerckhoffs L.H., Nagatani A., Kendrick R.E., Koornneef M. (1995). Far-red light-insensitive, phytochrome A-deficient mutants of tomato. Mol. Gen. Genet. 246: 133–141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venditti C., Pagel M. (2009). Speciation as an active force in promoting genetic evolution. Trends Ecol. Evol. 25: 14–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Wettberg E.J., Schmitt J. (2005). Physiological mechanism of population differentiation in shade-avoidance responses between woodland and clearing genotypes of Impatiens capensis. Am. J. Bot. 92: 868–874 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner J.R., Brunzelle J.S., Forest K.T., Vierstra R.D. (2005). A light-sensing knot revealed by the structure of the chromophore-binding domain of teh phytochrome. Nature 438: 325–331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner J.R., Zhang J., Brunzelle J.S., Vierstra R.D., Forest K.T. (2007). High resolution structure of Deinococcus bacteriophytochrome yields new insights into phytochrome architecture and evolution. J. Biol. Chem. 282: 12298–12309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weller J.L., Batge S.L., Smith J.J., Kerckhoffs L.H.J., Sineshchekov V.A., Murfet I.C., Reid J.B. (2004). A dominant mutation in the pea PHYA gene confers enhanced responses to light and impairs the light-dependent degradation of phytochrome A. Plant Physiol. 135: 2186–2195 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weller J.L., Schreuder M.E., Smith H., Koornneef M., Kendrick R.E. (2000). Physiological interactions of phytochromes A, B1 and B2 in the control of development in tomato. Plant J. 24: 345–356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White G.M., Hamblin M.T., Kresovich S. (2004). Molecular evolution of the phytochrome gene family in Sorghum: Changing rates of synonymous and replacement evolution. Mol. Biol. Evol. 21: 716–723 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitelam G.C., Johnson E., Peng J., Carol P., Anderson M.L., Cowl J.S., Harberd N.P. (1993). Phytochrome A null mutants of Arabidopsis display a wild-type phenotype in white light. Plant Cell 5: 757–768 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Y., Parks B.M., Short T.W., Quail P.H. (1995). Missense mutations define a restricted segment in the C-terminal domain of phytochrome A critical to its regulatory activity. Plant Cell 7: 1433–1443 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang X., Kuk J., Moffat K. (2008). Crystal structure of Pseudomonas aeruginosa bacteriophytochrome: Photoconversion and signal transduction. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 105: 14715–14720 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang X., Stojkovic E.A., Kuk J., Moffat K. (2007). Crystal structure of the chromophore binding domain of an unusual bacteriophytochrome, RpBphP3, reveals residues that modulate photoconversion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 104: 12571–12576 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]