Abstract

A 3-year interactive and passive training for HIV prevention education was conducted for 2,600 prisoners; 1,404 (54%) black, 1,092 (42%) white and 204 (4%) Hispanic. Less than 520 (20%) of inmates knew all the routes of HIV transmission. A post-presentation test showed that 96% became aware of HIV/AIDS transmission and can better protect themselves. Skin infections caused by Staphylococcus aereus were reported and manifested clinically as pustules, cellulites, boils, carbuncles or impetigo. Though no systemic infection was involved, staphylococcal infections suggest lowered immunity, an indicator to undiagnosed HIV. This study purposefully provides HIV prevention education model for prison health educators.

INTRODUCTION AND EPIDEMIOLOGY OF HIV IN PRISONS

Risk factors such as rape and injection drug use within prisons place inmates at an exceptionally high risk of HIV/AIDS infection. Imprisoned females with a history of prostitution, injection drug use, and contact with HIV-infected sex partners are at additional risk of infection (Kassira, Bauserman, Tomovasu, Caldeira, Swetz & Solomon, 2001). Prisoners who become HIV positive remain very important sources of infection to the public when they are released. Recent findings have underscored the urgency to provide HIV prevention educational program to prisoners. In some epidemiological reports (Harding, T.W. & Schaller, G.1992; Kantor, 2003), the rate of HIV/AIDS in the world is increasing. Kantor (2003) also reported that, though no comprehensive surveys have been documented in prison populations, countries with particularly high sero-prevalence identified among prisoners included Brazil (15% in 2001 {0.6% in community}), Cote d’Ivore (27.5% in 2001 {10.8% in community}), South Africa (15% in 2001 {19.9% in community}), Zambia (26.7%), Nigeria (9.0%), Honduras (6.8%), Russian Federation (3.1%), Netherlands (3.1%), France (4.1%) and Spain (16.4% in 2000)

Independent surveys and many regional studies in the US and internationally have been done (CDC, 1986, Carvel & Hart, 1990). US prison populations have multiplied in recent years primarily because incarceration has been the central tactic of the war on drugs. Millions of intermittently incarcerated people in America, many of whom are illicit drug users, are among the most difficult people to reach with critical health information. In an editorial report presented to the US Congress, it was reported that 57% of federal prisoners were incarcerated for drug offenses in 2001 (AIDS: “an unanswered question” by an Editor 1993, Alabama Department of Corrections, 2004 & CDC, 1986). According to Kantor, (2003), the HIV/AIDS rate is six times higher in US state and federal prisons than in the general population. Racial statistics are not routinely collected in sero-prevalence studies. However, the comparison of prison and total AIDS cases cited in the recent study, found that African Americans comprise 58% of prison cases versus 39% of total cases. In a report from Maryland, Kassira et al. (2001), noted that AIDS cases identified in the state’s prisons were 91% African Americans versus 75% statewide. There is a paucity of such reports in Alabama prison statistics. The primary purpose of this three-year study is to examine the effectiveness of interactive and passive trainings on HIV/AIDS prevention education programs to pre-released, non-violent offenders. Secondarily, it is to provide an appropriate and effective educational instrument and model that is easy to use in our prison systems.

BACKGROUND AND THE PRISONS SITUATION

Prison A, opened in 1990 is situated in Barbour County, a Black Belt county of Alabama state. The dormitories were designed to hold 650 inmates. It currently has 1,650 beds and holds 1,645 prisoners, a 253% occupancy rate. It was designed to maintain “medium or below custody inmates” (Alabama Department of corrections report, 2004). Its primary mission was to provide eight-week alcohol or drug treatments to growing inmate populations and fifteen-week of treatment for inmates with dual disorders of drugs and alcohol. The therapeutic facility also offers academic, vocational and health education to inmates. All prisoners transferred to this prison must test negative for HIV before they are accepted. Inmates that test positive are transferred to another facility offering HIV/AIDS care. Prison B, located in Bullock County, is an all-female, Black Belt county facility for non-violent offenders designed for similar rehabilitation program in drug and alcohol. It has a capacity for 611 inmates but currently has 1,318 beds and accommodates 1,318 prisoners, an occupancy rate of 207%.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

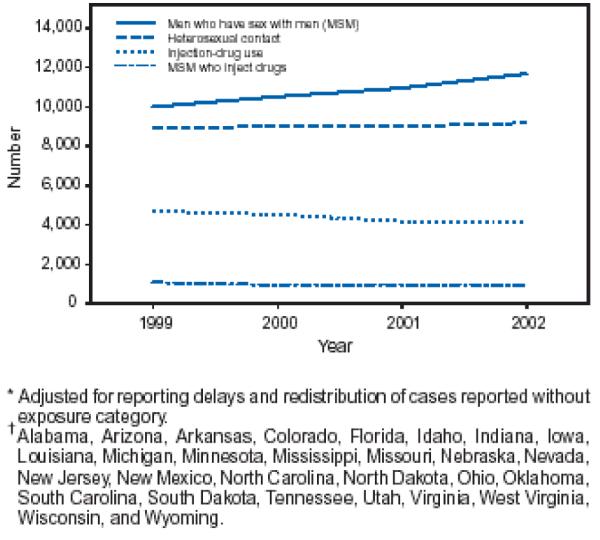

Two HIV/AIDS education programs were used in this project. First was an interactive program that involved an instruction-led session, discussion and a question-answer period. The second was a passive program that involved viewing approved videotape titled “Reasons To Care” made by the Red Cross in 1995. Participants were also shown transparencies of the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) data titled “Increases in HIV Diagnoses for 29 States, 1999-2002” (Fig.1) and work done by Tuskegee University scientists and others on HIV studies in African Americans and the Hispanics (Habtemariam, Tameru, Nganwa, Ayanwale, Ahmad, Oryang et.al. 2001), Habtemariam et al., 2001). For the interactive program, two standardized short survey instruments (SSI) were administered. The first SSI was a pre-instruction, one-page questionnaire that tested the knowledge of inmates about HIV ‘facts’ and how an infection can be prevented. It contained 10 short questions on whether he or she knew: 1) how a newly infected HIV positive person looks and feels in health; 2) that the sources of the virus are body fluids such as blood, semen, vaginal fluid and breast milk; 3) about an HIV positive person’s ability to infect others; 4) that a person who has recently become infected with HIV may test negative; 5) if a cure for AIDS has been discovered; 6) if birth control pills can prevent HIV transmission; 7) if latex condom can reduce a person’s risk for HIV infection; 8) if a first time sex with an infected person without using a condom can be a source of infection; 9) if they can be infected through oral sex or “fingering” with an HIV positive person; and 10) if abstinence is the only 100% sure method of preventing sexually transmitted diseases (STD) including HIV. The second SSI was an evaluation instrument. It contained multiple-choice questions that tested their comprehension of the interactive-program lecture content as presented. We also solicited their suggestions and insights on HIV prevention among inmates.

FIGURE 1.

Estimated number of persons with HIV diagnoses*, by exposure category and year – 29 states†, 1999–2002

Participants in each monthly session were 68-92 inmates of two adjacent dormitories along with their civilian warden and attendants until the entire population at the time was reached. A 15-minutes videotape on the prevention of HIV/AIDS, approved by the Department of Corrections (DC) was shown at each session followed by lecture presentation. Our major instructor had been trained in a DC approved HIV/AIDS prevention education program and the rules and regulations guiding the relationship of civilians with prisoners. It was emphasized that the best choice of prevention of HIV and other sexually transmitted diseases was abstinence. In its absence, the use of latex barriers was recommended. Each session was conducted using (by manual demonstration) devices needed for preventing STDs, such as latex condom for men and women. The best ways to use the latex barriers for effective prevention of transmission were also demonstrated. The chemistry and applications of oil and water based lubricants on such artificial barriers were also explained.

The second educator was a research scientist from Tuskegee University whose team had worked on the epidemiology of HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis and other chronic diseases. He also has undergone a National Institute of Health (NIH) certificate course on “Human Participant Protection Education for Research Teams”. As a result of previous questions by inmates on the epidemiology of HIV/AIDS infection in the US, graphs of HIV/AIDS data produced by the CDC in American population in 1993 and 2003 were discussed. The female instructor conducted similar educational programs to the female prisoners. At the end of each talk, participants were allowed to ask questions relevant to HIV/ AIDS only.

OBSERVATION AND RESULTS

A total of 29 educational sessions were conducted over a 3-year period. The sessions cumulatively involved 2,700 inmates whose response data were analyzed. All prisoners were tested negative by the Department of Corrections before they were admitted to the facility and would be re-tested before release. Each laboratory test was conducted using blood drawn from the prisoner’s forearm. Only if a prisoner falls sick of a suspicious AIDS infection would that individual be tested again. If tested positive, the person would be transferred to another facility where HIV/AIDS inmates receive medical treatment. There was no new case of HIV detected among the inmates during the periods of our visits. Out of the 2,700 inmates that went through the educational programs, 64% were black, 32% white and 4% were Hispanic and other races. Less than 20% of all inmates who responded to the questionnaires knew all the routes of transmission of HIV from one person to another. While over 92% of the respondents had used a condom before, less than 40% liked using it. “It was like sleeping in a bed with your shoes on” responded one inmate. Many believe that ‘shots will cure AIDS’. From the evaluation result, over 92% inmates became more aware of the HIV/AIDS implying on how better they could protect themselves when they are released. The prisoners complained of skin lesions to the prison authority. The infections were not systemic but confined to single pustules, boils, cellulites, carbuncles, furuncles and or impetigo. The prisoners seemed to be very well interested in the explanation and discussion of the CDC data on persons newly diagnosed as having HIV in the US (Table and Figure1).

Table.

Estimated number and percentage of persons with new diagnosis of HIV infection, by sex and selected characteristics–29 states* with HIV reporting, 1999–2002

| Ma1e |

Female |

Total |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | No. | (%) | No. | (%) | No. | (%) |

| Age group (yrs) | ||||||

| <13 | 315 | (0.4) | 398 | (1.3) | 713 | (0.7) |

| 13–24 | 6,337 | (8.8) | 5,074 | (16.8) | 11,411 | (11.1) |

| 25–34 | 20,378 | (28.2) | 9,330 | (30.8) | 29,708 | (29.0) |

| 35–44 | 27,518 | (38.0) | 9,383 | (31.0) | 36,901 | (36.0) |

| 45–54 | 12,776 | (17.7) | 4,365 | (14.4) | 17,142 | (16.7) |

| 55–64 | 3,811 | (5.3) | 1,278 | (4.2) | 5,089 | (5.0) |

| ≥65 | 1,189 | (1.6) | 436 | (1.4) | 1,625 | (1.6) |

| Total† | 72,323 | (100.0) | 30,264 | (100.0) | 102,590 | (100.0) |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||||||

| White, non-Hispanic | 26,602 | (36.8) | 5,474 | (18.1) | 32.077 | (31.3) |

| Black, non-Hispanic | 35,127 | (48.6) | 21,744 | (71.8) | 56,872 | (55.4) |

| Hispanic§ | 9,266 | (12.8) | 2,563 | (8.5) | 11,829 | (11.5) |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 432 | (0.6) | 129 | (0.4) | 562 | (0.5) |

| American Indian/Alaska Native | 435 | (0.6) | 174 | (0.6) | 609 | (0.6) |

| Unknown | 461 | (0.6) | 179 | (0.6) | 641 | (0.6) |

| Exposure category | ||||||

| Men who have sex with men (MSM) | 43,144 | (59.7) | – | – | 43,144 | (42.1) |

| Injection-drug use | 11,419 | (15.8) | 6,133 | (20.3) | 17,553 | (17.1) |

| MSM who inject drugs | 3,917 | (5.4) | – | – | 3,917 | (3.8) |

| Heterosexual contact | 12,879 | (17.8) | 23,205 | (76.7) | 36,084 | (35.2) |

| Other | 963 | (1.3) | 926 | (3.1) | 1,891 | (1.8) |

| Year of diagnosis | ||||||

| 1999 | 17,556 | (24.3) | 7,575 | (25.0) | 25,133 | (24.5) |

| 2000 | 17,872 | (24.7) | 7,588 | (25.1) | 25,461 | (24.8) |

| 2001 | 18,050 | (25.0) | 7,542 | (24.9) | 25,592 | (24.9) |

| 2002 | 18,843 | (26.1) | 7,559 | (25.0) | 26,403 | (25.7) |

Alabama, Arizona, Arkansas, Colorado, Florida, Idaho, Indiana, Iowa, Louisiana, Michigan, Minnesota, Mississippi, Missouri, Nebraska, Nevada, New Jersey, New Mexico, North Carolina, North Dakota, Ohio, Oklahoma, South Carolina, South Dakota, Tennessee, Utah, Virginia, West Virginia, Wisconsin, and Wyoming.

Includes persons for whom data on sex, age, or race/ethnicity are missing. Columns might not add to total because of rounding.

Hispanics might be of any race.

DISCUSSION

The male and female prison facilities have normal combined capacities for 1,261 inmates (650 males +611females), but together they were 2,910 prisoners (1,645+1265). These represent 253.1% and 207.0 % occupancy rates, respectively, for most of this study period. The game halls were converted to provide sleeping rooms for inmates, a situation that underscores the degree of congestion until the federal government gave the order to reduce the over-crowding and bring the inmate populations back to the normal capacity. We learned from the inmates of the secretive use of orally ingested or inhaled psychoactive substances, such as cocaine, solvents and alcohol that could obviously impair or hinder the adoption of learned preventive measures.

Though HIV test results showed no new cases during the period of our study, the high rate of staphylococcal infection among the prisoners was a matter of concern. The infections may be an indicator of undetected HIV infection (Elgert, 1992). Prison yards all over the country are congested (CDC, 1995). This could have also contributed to the reported outbreak of Staphylococcus infections among the inmates. The skin infection problem in the prison populations must be addressed by the authorities. A newly infected incoming prisoner with HIV but who has not developed detectable antibodies to the virus when tested will produce false negative results (Elgert 1992).

The Staphylococcal disease therefore calls for further medical investigation among the infected inmates to eliminate undetected HIV infections. The immune mechanisms that relate to susceptibility and resistance of individuals to Staphylococcus infection are not well understood (Benenson, 1990). Susceptibility to this disease is greatest among drug abusers, debilitated persons and those whose immunities are compromised such as in undiagnosed cases of HIV infection. These false negative prisoners constitute a dangerous focus of spread from within the prison and to the public when released. Staphylococcal disease is caused by Staphylococcus aureus a coagulate-positive bacterial pathogen. It produces a variety of syndromes with clinical signs ranging from a single swelling with pus (a pustule), septicemia and possible death (Benenson, 1990). The disease shows distinct differences in clinical and epidemiologic patterns in general community, in newborns, menstruating women, prisoners, hospitalized patients, hospital staffers and other worksite settings. The control of each outbreak has to be considered in line with the setting. This same organism incriminated in food poisoning cannot be classified as an infection. It is an intoxication that may be confined to the alimentary canal, liver and kidney if the toxins are absorbed.

CONCLUSION

Despite the limitation of this interactive education project in two Alabama prison facilities that did not include juvenile prisons, our findings are representative of most prisons in the US and similar to what others have found elsewhere (CDC 1986, 1995, Hernandez 1996 & Kantor 2003). They are generally applicable to prison systems. The findings also underscored several advantages in the global fight against HIV disease. The inmates that took part in the sessions became better aware of the dangers of HIV and the preventive roles they are expected to play when they are released back into their communities. It should be emphasized to the inmates that though meaningful progress in treating HIV disease has been made, biomedical research has not yet produced definitive treatments for the disease. Prevention is the key to not contracting HIV/AIDS.

Because congested prisons are conducive to forced or consenting homosexual activities among prisoners, this matter needs to be addressed. The use of orally ingested drugs, alcohol, crack cocaine or inhaled psychoactive substances is another problem as they may increase the likelihood of HIV transmission by impairing and hindering the cognitive adoption of preventive measures by prisoners in spite of preventive education offered to them. Infected prisoners are a great potential source of transmission of HIV to the public upon their release. In order to assist reducing the occurrence and spread of HIV in and outside our prison systems, comprehensive and focused programs in HIV preventive education, counseling and periodic testing of inmates are recommended. Faith based organizations should collaborate with correctional facility administrators to reinforce behavior that are prohibited to inmates such as the distribution of condoms and bleaches (Mahon, 1996, Maruschak 2001, Meneyo, Suarrez & Lopez 2002). Practical risk reducing techniques such as safer sex and safer drug injection should be implemented for inmates because many of them have already established patterns of high-risk behavior for HIV infection. Independent research in the field of HIV/AIDS among prison populations should be encouraged. In collaboration with community organizations, programs of support and counseling are needed to help prisoners in initiating and sustaining positive behavior change. Prisons for juvenile offenders should be included in health education and preventive programs such as this simple interactive model because they cost less and will save more lives. Further implication of this technique in public health education, based on the result we obtained of the model, is that, it helps in presenting science-based information to people with low formal educational trainings. The knowledge helps in reducing health disparity among the people who need it most.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

This study was supported by the NIH funded EXPORT PROJECT grant on Health Disparity for Tuskegee University and the University of Alabama, Tuscaloosa. Grant # 5-P20 –ND 000195-03. We thank Mrs. Marie Loretan for reviewing this paper.

REFERENCES

- 1.American Academy of Pediatrics Selecting and using appropriate car safety seats for growing children: Guidelines for counseling parents. Pediatrics. 2002;109:550–553. doi: 10.1542/peds.109.3.550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Task Force on Community Preventive Services Recommendations to reduce injuries to motor vehicle occupants: Increasing child safety use, increasing safety belt use, and reducing alcohol-impaired driving. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2001;21:16–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [Retrieved March 10, 2008];Community-based interventions to reduce motor vehicle-related injuries: Evidence of effectiveness from systematic reviews. 2002 from http://www.cdc.gov/ncipc/duip/mvsafety.htm.

- 4.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [Retrieved March 10, 2008];Child Passenger Safety: Fact Sheet. 2007 from http://www.cdc.gov/print.

- 5.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Center for Injury Prevention and Control [Retrieved March 10, 2008];Web-based injury statistics query and reporting system (WISQARS) 2008 from http://webappa.cdc.gov/cgibin/broker.exe.

- 6.Decina LE, Lococo KH, Block AW. [Retrieved March 10, 2008];Misuse of child restraints: Results of a workshop to review field data results. 2005 from http://www.nhtsa.dot.gov/people/injury/research/TSF_MisuseChildRestraints/images/809851.pdf.

- 7.Durbin DR, Elliott MR, Winston FK. Belt-positioning booster seats and reduction in risk of injury among children in vehicle crashes. JAMA. 2003;28:2835–2840. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.21.2835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.National Highway Transportation Safety Administration [Retrieved March 10, 2008];Traffic safety facts 2005: Children. 2006 from http://www-nrd.nhtsa.dot.gov/pdf/nrd-30/NCSA/TSF2005/ChildrenTSF05.pdf.

- 9.National Highway Transportation Safety Administration [Retrieved September 2, 2008];Strengthening child passenger safety laws. 2008a from http://.nhtsa.gov/staticfiles/DOT/NHTSA/Communication.

- 10.National Highway Transportation Safety Administration [Retrieved September 2, 2008];Traffic safety facts; 2006 Data:Rural urban comparison. 2008b from http://www-nrd.nhtsa.dot.gov/Pubs/810812.PDF.

- 11.Sallant P, Dillman DA. How to conduct your own survey. John Wiley & Sons, Inc; New York, NY: 1994. pp. 53–55. 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Segui-Gomez M, Wittenberg E, Glass R, Levenson S, Hingson R, Graham J. Where children sit in cars: The impact of Rhode Island’s new legislation. American Journal of Public Health. 2001;91:311–313. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.2.311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Valent F, McGwin G, Hardin W, Johnston C, Rue L. Restraint use and injury patterns among children involved in motor vehicle crashes. Journal of Trauma, Injury, Infection and Critical Care. 2002;52:745–751. doi: 10.1097/00005373-200204000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Winston F, Dyrbin D, Kallan M, Moll E. The danger of premature graduation to safety belts for young children. Pediatrics. 2000;105:1179–1183. doi: 10.1542/peds.105.6.1179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zaza S, Sleet DA, Thompson RS, Sosin DM, Bolen JC. Reviews of evidence regarding interventions to increase use of child safety seats. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2001;21:31–43. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(01)00377-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]