Abstract

This article looks at the current burden of communicable diseases in the South-East Asia Region of the World Health Organization and analyses whether the current levels and trends in funding are adequate to meet the needs of control, prevention and treatment. Our analysis considers the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) for health and indicators of economic progress in each country, as well as the impact of the global financial crisis on progress towards MDGs for communicable diseases in the region. The analysis indicates that the current focus of funding may need to be expanded to include less-discussed but high-burden diseases often related to inadequacies in the health sector and the particular development paths that countries pursue. Scarce funding during times of global economic recession could be used more effectively if informed by a careful analysis of the complex set of factors, including behavioural, environmental and health systems factors, that determine the burden of communicable diseases. Significant gaps in funding as well as varying regional needs warrant a more diverse set of national and international aid measures. Although regional and global collaboration is critical, the effectiveness of future policies to deal with the burden of communicable diseases in the region will only be assured if these policies are based on evidence and developed by policy-makers familiar with each country’s needs and priorities.

Résumé

Le présent article évalue la charge actuelle de maladies transmissibles dans la Région de l’Asie du Sud-est de l’Organisation mondiale de la Santé et examine si les niveaux et les tendances actuel des moyens de financement sont suffisants pour répondre aux besoins en matière de lutte, de prévention et de traitement. Notre analyse examine les Objectifs du Millénaire pour le développement (OMD) et les indicateurs de progrès économique dans chaque pays, ainsi que l’impact de la crise financière mondiale sur les progrès vers les OMD relatifs aux maladies transmissibles dans la région. D’après cette analyse, l’affectation actuelle des fonds peut devoir être élargie pour couvrir des maladies moins souvent évoquées, mais à forte charge de morbidité, associées fréquemment à des inadéquations entre le secteur de la santé et les voies de développement particulières suivies par les pays. En période de récession économique, l’utilisation de fonds limités peut être plus efficace si elle se fonde sur l’analyse soigneuse d’une série complexe de paramètres, incluant des facteurs comportementaux, environnementaux et relatifs au système de santé, qui déterminent la charge de maladies transmissibles. L’existence de lacunes importantes en matière de financement, ainsi que la variabilité des besoins régionaux, justifient une diversification des mesures d’aide nationales et internationales. Si la collaboration au niveau régional et mondial est essentielle, il faut, pour que les politiques futures répondant à la charge de maladies transmissibles dans la région soient efficaces, que ces politiques reposent sur des éléments factuels et soient développées par des décideurs familiarisés avec les besoins et les priorités de chaque pays.

Resumen

En este artículo se examina la carga de enfermedades transmisibles que sufre actualmente la Región de Asia Sudoriental de la Organización Mundial de la Salud y se determina si el nivel y las tendencias actuales de la financiación son adecuados para atender las necesidades de control, prevención y tratamiento. Se consideran los Objetivos de Desarrollo del Milenio (ODM) relacionados con la salud y los indicadores de progreso económico de cada país, así como el impacto de la crisis financiera mundial en los progresos hacia los ODM en lo que atañe a las enfermedades transmisibles en la región. Se desprende del análisis realizado que tal vez deberían ampliarse las actuales prioridades de la financiación para abarcar enfermedades que son objeto de un menor interés pero conllevan una alta carga, a menudo en relación con las insuficiencias del sector de la salud y con las vías particulares de desarrollo seguidas por los países. La escasa financiación conseguida en los periodos de recesión económica mundial podría ser más eficaz si se viera fundamentada por un análisis meticuloso del complejo conjunto de factores -en particular comportamentales, ambientales y de los sistemas salud- que determinan la carga de enfermedades transmisibles. Las importantes déficits de financiación, así como las diferentes necesidades regionales, justifican una mayor diversidad de medidas nacionales e internacionales de ayuda. Aunque la colaboración regional y mundial es fundamental, para que sean efectivas, las futuras políticas contra la carga de enfermedades transmisibles que sufre la región deberán estar basadas en la evidencia y ser desarrolladas por instancias normativas familiarizadas con las necesidades y prioridades de cada país.

ملخص

يستعرض هذا المقال العبء الحالي للأمراض السارية في إقليم جنوب شرق آسيا التابع لمنظمة الصحة العالمية، ويقوم بتحليل ما إذا كانت المستويات والاتجاهات الحالية للتمويل كافية لتلبية الاحتياجات التي تتطلبها مكافحة هذه الأمراض والوقاية منها ومعالجة الحالات المصابة بها. وتأخذ إجراءات التحليل في الاعتبار المرامي الإنمائية للألفية الخاصة بالصحة، والمؤشرات الدالة على إحراز التقدم الاقتصادي في كل بلد، إضافة إلى تحليل تأثير الأزمات المالية العالمية على التقدم نحو بلوغ المرامي الإنمائية للألفية والخاصة بالأمراض السارية في الإقليم. وتوضح التحاليل أن بؤرة تركيز التمويل الحالي قد تحتاج إلى المزيد من التوسع لتشمل الأمراض التي لا تتم مناقشتها كثيرا مع كونها ذات عبء مرضي عال يرتبط غالباً بقصور القطاع الصحي، والمسار التنموي الخاص الذي تسلكه البلدان. ويمكن للموارد المالية الشحيحة أن تكون أكثر فعالية أثناء الكساد الاقتصادي العالمي إذا ما توافرت المعلومات المنبثقة عن التحاليل الدقيقة للمجموعات المعقدة من العوامل السلوكية والبيئية وتلك الخاصة بالنظم الصحية والتي من خلالها يمكن تحديد عبء الأمراض السارية. إن الثغرات الكبيرة في عمليات التمويل والاحتياجات الإقليمية المتنوعة تستدعي المزيد من تدابير المساعدات الوطنية والدولية المتنوعة. ولما كان التعاون الإقليمي والدولي له أهميته، فإن فعالية السياسات المستقبلية الخاصة بالتعامل مع عبء الأمراض السارية في الإقليم لن تكون مضمونة ما لم تكن هذه السياسات مسندة بالبينات وموضوعة من قبل راسمي سياسات على دراية باحتياجات كل بلد وأولوياته.

Introduction

Although disease patterns change constantly, communicable diseases remain the leading cause of mortality and morbidity in least and less developed countries. Despite decades of economic growth and development in countries that belong to the World Health Organization (WHO) South-East Asia Region (http://www.who.int/about/regions/searo), most countries in this region still have a high burden of communicable diseases. This raises some urgent concerns. The first is that despite policies and interventions to prevent and control communicable diseases, most countries have failed to eradicate vaccine-preventable diseases. Second, sustainable financing to scale up interventions is lacking, especially for emerging and re-emerging diseases that can produce epidemics. Finally, in the present global economic and political context, it is important to understand how international aid agencies and donors prioritize their funding allocations for the prevention, control and treatment of communicable diseases. Prioritization is especially critical if one accepts the global public good character of communicable diseases.1,2

This paper analyses the current burden of communicable diseases in the region and explores whether the current levels and trends in funding suffice to meet the needs for their control, prevention and treatment. Our analysis considers the health Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) and individual countries’ economic progress. We attempt to understand whether the current focus of disease prevention is appropriate and to ascertain what changes in direction might enable national and global policy-making to deal more effectively with communicable diseases.

Communicable diseases

Disease burden

Although communicable diseases can be categorized in different ways, WHO uses three guiding principles for prioritization: (i) diseases with a large-scale impact on mortality, morbidity and disability, such as human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection and acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), tuberculosis (TB) and malaria; (ii) diseases that can potentially cause epidemics, such as influenza and cholera; and (iii) diseases that can be effectively controlled with available cost-effective interventions, such as diarrhoeal diseases and TB.3 According to WHO data on the global burden of disease and the distribution of diseases among countries, communicable diseases contribute slightly more to the total disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) lost in the region (42%) than in the world as a whole (40%).4

According to WHO,5 low-income countries currently have a relatively higher share of deaths from: (i) HIV infection, TB and malaria, (ii) other infectious diseases, and (iii) maternal, perinatal and nutritional causes compared with high- and middle-income countries. Although these three causes combined pose a lesser burden than non-communicable diseases, they will remain important causes of mortality in the next 25 years in low-income countries. In 2004, all countries of the region except for Indonesia, Maldives, Sri Lanka and Thailand were classified as low-income by The World Bank.

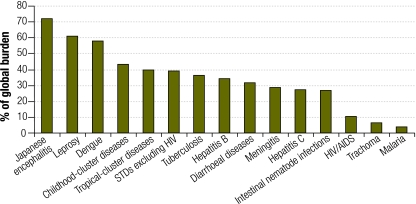

Fig. 1 shows the share of the region’s contributions to world DALYs lost due to infectious and parasitic diseases. The region bears a disproportionate share of diseases such as Japanese encephalitis, leprosy and dengue, which have been eliminated from most of the world. Countries of the region also contribute a higher share of DALYs due to childhood cluster and tropical cluster diseases than the rest of the world. WHO estimates that the region contributes 27% of the global burden of infectious and parasitic diseases, 30% of respiratory infections, 33% of maternal conditions, 37% of perinatal conditions and 35% of nutritional deficiencies. If the first two categories are included under communicable diseases, the region’s contribution to the global communicable disease burden is disproportionately high. Diarrhoeal disease is the leading causes of death in the region and accounts for 26% of all deaths from infectious and parasitic diseases. TB, childhood cluster diseases, HIV infection, AIDS and meningitis are the other four major causes of death in the region. Diseases labelled as a priority by WHO (HIV infection and AIDS, TB and malaria) are common in all 11 countries. For example, the prevalence of HIV infection per 100 000 adult population is 982 in Myanmar, 447 in Nepal and 1144 in Thailand. The prevalence of TB per 100 000 population is 391 in Bangladesh, 253 in India, 244 in Nepal and 789 in Timor-Leste.6

Fig. 1.

Share of world DALYs due to infectious and parasitic diseases corresponding to the South-East Asia Region of the World Health Organization, 2004

DALYs, disease-adjusted life years; STDs, sexually transmitted diseases.

The data were obtained from the World Health Organization.4

Table 1 shows the annual incidence of selected communicable diseases in the world and in the region. Some of the highest annual incidences worldwide of diarrhoeal diseases, lower respiratory infections, malaria, measles and dengue appear in the region. The percentage of the world’s disease burden contributed by countries of the region is 64 for measles, 36 for TB, 33 for upper respiratory infections, 52 for dengue and 28 for diarrhoeal disease.7 Clearly, communicable diseases present a mixture of challenges for the region, with a variety of them falling under all three WHO categories mentioned above: diseases with high mortality and morbidity, those that can potentially cause epidemics and those that can be controlled with available and proven interventions.

Table 1. Annual incidence of selected communicable diseases worldwide and in the South-East Asia Region of the World Health Organization, 2004a.

| Disease | Annual incidence |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Worlda | WHO South-East Asia Regionb | |||

| Tuberculosis | 7 782 | 2 830 | ||

| HIV infection | 2 805 | 246 | ||

| Diarrhoeal diseases | 4 620 419 | 1 276 528 | ||

| Pertussis | 18 387 | 7 509 | ||

| Diphtheria | 34 | 13 | ||

| Measles | 27 118 | 17 397 | ||

| Tetanus | 251 | 112 | ||

| Meningitis | 668 | 170 | ||

| Malaria | 241 340 | 23 263 | ||

| Chagas disease | 109 | 0 | ||

| Leishmaniasis | 1 715 | 362 | ||

| Dengue | 8 951 | 4 638 | ||

| Lower respiratory infections | 446 814 | 146 463 | ||

HIV, human immunodeficiency virus. a World population: 6 436 826 483. b Population of the WHO South-East Asia Region: 1 671 903 660. The data were obtained from the World Health Organization.7

National and regional variations

The share of total DALYs lost due to communicable diseases is higher than the regional average (approximately 30%) in Bangladesh (48%), India and Bhutan (44% each), Myanmar (46%), Nepal (49%) and Timor-Leste (58%). In contrast, this proportion is lower than the regional average in Sri Lanka (15%), and similar to it in the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea, Indonesia, Maldives and Thailand.

Relatively older diseases such as TB, malaria, cholera and meningitis have recently recrudesced worldwide. At the same time, newer or re-emerging diseases such as infection with influenza A (H5N1) virus (avian flu), severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) and chikungunya have reached epidemic proportions in some countries. Many countries are also facing the rapid spread of infection with influenza A (H1N1) virus (i.e. pandemic influenza). In the region, Thailand has reported the most deaths from pandemic influenza, and India and Indonesia have reported a fairly rapid increase in the number of cases. In 2007, India and Indonesia were among the top five countries in the region in terms of the total number of TB cases.8 As for multidrug resistant TB, India contributes the most cases in the region, with Bangladesh ranking fifth.

The five infectious and parasitic diseases that contribute the most DALYs lost are generally the same in all countries of the region although variations in the rank order exist. The top-ranking contributor is lower respiratory infections in 8 out of 11 countries; HIV infection and AIDS in Thailand, TB in Indonesia, and malaria in Timor-Leste. Countries of the region are thus facing huge challenges from diseases generally associated with underdevelopment, poverty and a less-than-effective health system, as well as from emerging infectious diseases.4

Disease priorities

In-country estimates of disease burdens are the best tools for guiding prioritization, but a reliable analysis of how countries set their priorities is not easy because information and data are lacking on internal processes that lead to resource allocation. Unfortunately, ongoing burden of disease calculations are still not a priority in the region, and sustainable technical expertise for these analyses is also lacking. National health accounts, if available, are of some help but may not in themselves make comprehensive accounting of resource allocations for communicable diseases possible. Also, not all countries in the region have national health accounts in a format that allows comparisons of aggregates across countries, and this is true for communicable diseases. If functional allocations are assumed to be indicators of prioritization, then countries appear to be giving different weights to communicable diseases. For example, total health expenditure on the prevention and control of communicable diseases in India (1.4%) is half the amount Sri Lanka allocates.9,10

Another approach to prioritization is to use inputs from international agencies such as the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria. Most countries in the region now have Global Fund resources for the prevention and treatment of these three diseases. Although this funding should be used for additional activities and interventions, there are no data or analyses that clarify whether they have complemented or substituted for the resources regularly allocated to communicable diseases.

Disease prioritization is also implicit in MDGs 4, 5 and 6: to reduce child mortality, improve maternal health and combat HIV infection, AIDS, malaria and other diseases, respectively. Because most discussions of MDGs centre on Goal 6, attention is detracted from other conditions whose reduction would lead to a lower burden of communicable diseases. For example, improving maternal health would have a direct, positive impact on child health and reduce child mortality. Although Goal 6 embraces other diseases, in operational terms it includes only TB in addition to malaria, HIV infection and AIDS.11,12 If all three MDGs were addressed seriously, countries would see a reduction in communicable disease incidence. However, it is not clear whether funds are effectively allocated to the various diseases comprised by the three MDGs. For example, there are large global funding windows for the diseases targeted by Goal 6 but fewer windows for childhood disease interventions that go beyond vaccination and attempt to address other fundamental health and development sector issues. Current funding criteria may thus limit the effectiveness of existing strategies.

Addressing other MDGs, such as the eradication of poverty and hunger, would also go a long way towardsmeeting health-centred MDGs. In the region, HIV infection is concentrated among populations that are marginalized, have adverse human development indicators and are mobile mostly because of economic reasons. Similarly, TB is seen to affect the “marginalized, discriminated against populations, and people living in poverty”.13 Malaria disproportionately affects the poor, especially because its cause is linked to livelihood, migration and living conditions.14,15 However, other communicable diseases are also linked to poverty and underdevelopment. For example, undernutrition is an underlying cause of child deaths associated with diarrhoea, pneumonia, malaria and measles.16

A look at the contributions from the region to world DALYs lost on account of different infectious and parasitic diseases (Fig. 1) shows that diseases prioritized by MDG 6 – HIV infection and AIDS, TB and malaria – are actually among the lowest-ranked. In contrast, Japanese encephalitis, leprosy, dengue and childhood cluster diseases in the region contribute much more to the total DALYs lost globally.

Eradication of vaccine-preventable diseases could reduce disease burdens effectively. An analysis of data from 97 developing countries shows that immunization coverage is a statistically significant predictor of the infant mortality rate.17 The negative association between the latter and immunization coverage was also established in successive National Family Health Surveys in India.18 Although routine vaccination coverage has reached high levels in many south-east Asian countries, others, such as India, Indonesia, Myanmar and Timor-Leste, have not achieved full coverage.

With vector-borne diseases on the rise, there are concerns about the ability of resource-deficient countries to combat large outbreaks. The prevention of outbreaks itself is challenging because of their complex determinants. This situation makes developing countries especially susceptible because the health sector can only play a relatively small role in prevention.19,20 The lack of a good disease surveillance system and the inadequacy of the primary care infrastructure compound the problems and make prevention, control and treatment of vector-borne diseases an urgent challenge.3,21

Although progress towards the MDGs seems to be on track for HIV, TB and malaria in many countries of the region, realistic goals in the light of economic growth patterns, development paradigms and health sector realities should include all other major health conditions that affect these countries. It might be more relevant for countries to individually redefine the objectives established for MDG goals 4, 5 and 6 in accordance with their particular realities and disease burdens.

The global economic crisis

According to a recent study of 25 developing countries,22 a decrease in the growth rate of gross domestic product (GDP) by three percentage points in Asia and the Pacific is likely to translate into 10 million more undernourished people, 56 000 more deaths among children < 5 years old, and 2000 more mothers dying in childbirth. Moreover, this decline was predicted to delay the achievement of MDG targets relating to infant mortality and hunger by one year. This finding is important in the context of the recent global financial crisis. Among the 11 countries of the region, the non-financial or real sectors in countries such as the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea, Indonesia, Timor-Leste and Thailand are much more affected by the global crisis compared to countries in South Asia. The impact of the recession on health spending and health outcomes, and hence on the control of communicable diseases, will be seen in several areas.23 (i) For example, overall budget cuts will result from a shrinking tax base and declining official development assistance. (ii) A possible impact on global health funding for communicable diseases might, in turn, affect national disease control programmes. (iii) Increased poverty and unemployment and declining incomes will lead to unfulfilled or delayed demand for treatment and poorer health outcomes. (iv) Increased subsidies will be needed to combat increased fuel and food prices. (v) Finally, the prices of essential drugs and medical goods will increase.

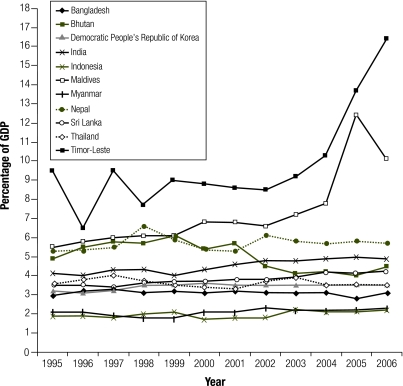

A comparison of the percentage of GDP spent on health in the region (Fig. 2) shows that Timor-Leste and Maldives have been successful in raising resources for health over the years, whereas most other countries have been less successful. India has been able to increase health spending slightly since 2000. Indonesia and Myanmar have a very low ratio of health spending to GDP, whereas the rest of the countries are somewhere in-between. The overall level of health spending, in turn, determines how much spending will potentially be available for communicable diseases. Therefore the data strongly suggest that financing for communicable diseases will remain a source of worry, especially for countries most severely affected by the financial crisis.

Fig. 2.

Total expenditure on health as a percentage of gross domestic product in countries of the South-East Asia Region of the World Health Organization, 1995–2006

The data were obtained from the World Health Organization.6

For countries that depend on external funding, the decrease in aid is a major worry. Aid diminishes during economic crises and sometimes does not recover fully to earlier levels.24 A large part of the funds for communicable diseases come from international donors and private foundations based in developed countries. Therefore the current crisis will also have an impact on this flow, which in turn will have a disproportionate impact on communicable diseases programmes.

Countries such as Maldives and Timor-Leste need to prepare for the effect of decreasing aid on their health sectors. Bhutan is somewhat less dependent on external funding and may therefore be able to escape the impact of declining aid. Although the current crisis has not significantly affected overseas development assistance in Nepal,25 the impact on communicable diseases linked to or aggravated by poverty and poor living conditions is likely to be severe enough to warrant serious attention from aid agencies. Myanmar’s economic growth has not translated into health sector gains, and this country also depends on foreign aid to augment its resources. Similarly, Bangladesh already faces increasing poverty and adverse health indicators, and the current crisis is likely to worsen the situation. Stimulus packages, implemented by some countries, may be needed.26 Maldives, a much smaller country, is in a better position to cope with the impact of the crisis since it has already received stimulus measures from domestic and international organizations. Timor-Leste, which is heavily dependent on aid, will need help to maintain its levels of investment in the health and social sectors.

The impact of shrinking economic growth and aid on vulnerable populations has direct implications for communicable diseases programmes. Global financing to fight communicable diseases is not always aligned with the disease priorities of developing countries, and since donors tend to imitate each other’s funding decisions, the real needs of developing countries may be overlooked.27 Applying the concept of global public good to health funding decisions would help reprioritize financing for communicable diseases and eliminate the distortions caused by disease-specific funding.2 These priority issues are more relevant now that economic growth, especially in many donor countries, has slowed significantly.

Discussion

The global response to the financial crisis has been to maintain the quantity of aid to the extent possible, so as not to jeopardize progress towards the MDGs.28 For example, The World Bank is planning to triple the loans it provides to the health sector.29 However, inefficiencies and inadequate management within the health sector in many countries of the region reduce the effectiveness of aid. The issue of aid effectiveness has now received serious attention from development agencies, and among the concerns are the lack of harmonization and alignment, problems with predictability and the need for common arrangements and procedures.30 A high-level WHO consultation on the impact of the global crisis on health31,32 identified the need to make health spending more effective and efficient and to ensure adequate aid levels.

As has been powerfully stated, “every change in demography, vegetation, land use, technology, economics and social relations is also a potential change in the ecology of pathogens and their reservoirs and vectors and therefore a change in the pattern of infectious disease epidemiology”.33 Preventing and responding to traditional, emerging and re-emerging communicable diseases is therefore a complex endeavour that will not succeed if it is limited to simply increasing the funds available to fight selected diseases. In times of financial crisis it is important for donor countries to find innovative solutions to enhance the effectiveness of their reduced volume of aid.34

Although the 11 countries of the region are on different trajectories of growth and development, their struggle to eliminate underdevelopment and poverty has driven them to a high-growth strategy. However, high-growth policies are increasing the population vulnerable to communicable diseases. Clearly, economic growth alone is not the solution. The 2009 Global monitoring report of the International Monetary Fund and The World Bank calls the current crisis a development emergency because the potential increase in vulnerable populations may delay progress in the fight against communicable diseases.35

Funding needs to be much more carefully matched to disease and health system priorities in each country. Although the MDG health goals are important benchmarks, programme goals should be more relevant, inclusive and realistic. They should be multisectoral and take into account both the realities of the health sector and the development path chosen by the country. Global health and development initiatives need to expand their focus to include diseases and conditions that are less well known or less discussed, while at the same time addressing socioeconomic and health sector constraints in each country. This approach would go a long way towards making aid more effective. Moreover, it would make donors and policy-makers more aware of traditional vaccine-preventable childhood diseases, traditional and emerging vector-borne diseases and respiratory infections, which remain among the most important contributors to high disease burdens in the WHO South-East Asia Region.

Ultimately, countries should set their own priorities for the prevention, control and treatment of communicable diseases. It is up to each country to convince the world of where its priorities lie. The global public good character of some communicable diseases warrants concerted world action. Nevertheless, significant gaps in funding as well as regional variations require a more diverse set of national and international aid measures. Although regional and global collaboration is critical, future policies for reducing the burden of communicable diseases in the region will only be affective if they are based on evidence and country-led. ■

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.Smith RD, Beaglehole R, Woodward D, Drager N, editors. Global public goods for health: a health economic and public health perspective Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smith RD, MacKellar L. Global public goods and the global health agenda: problems, priorities and potential. Global Health. 2007;3:9. doi: 10.1186/1744-8603-3-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Department of communicable diseases: profile and vision New Delhi: World Health Organization, Regional Office for South-East Asia; 2007. Available from: www.searo.who.int/LinkFiles/CDS_profile.pdf [accessed 11July 2009].

- 4.Disease and injury country estimates: burden of disease Geneva: World Health Organization; 2008. Available from: http://www.who.int/healthinfo/global_burden_disease/estimates_country/en/index.html [accessed 6 July 2009].

- 5.Global burden of disease 2004 update: selected figures and tables Geneva: World Health Organization; 2008. Available from: http://www.who.int/healthinfo/global_burden_disease/GBD2004ReportFigures.ppt#2 [accessed 30 November 2009].

- 6.Core health indicators Geneva: World Health Organization; 2008. Available from: http://apps.who.int/whosis/database/core/core_select_process.cfm [accessed 3 December 2009].

- 7.Disease and injury regional estimates for 2004: mortality and morbidity Geneva: World Health Organization; 2008. Available from: http://www.who.int/healthinfo/global_burden_disease/estimates_regional/en/index.html [accessed 6 July 2009].

- 8.Global tuberculosis control 2009: epidemiology, strategy, financing Geneva: World Health Organization; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Institute of Policy Studies. Sri Lanka national health accounts 2000-2002 Colombo: Ministry of Healthcare, Nutrition and Uva-Wellassa Development; 2005. Available from: http://www.who.int/nha/country/SLNHA_report_2000_2002.pdf [accessed 24 November 2009].

- 10.Government of India. National health accounts, India: 2001-2002 New Delhi: National Health Accounts Cell, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Millennium development goals New York: United Nations Development Programme; 2009. Available from: http://www.undp.org/mdg/goal6.shtml [accessed 3 December 2009].

- 12.Millennium development goals Geneva: World Health Organization; 2009. Available from: http://www.who.int/mdg/goals/goal6/en/index.html [accessed 3 December 2009].

- 13.Stop TB Partnership Secretariat. A human rights approach to tuberculosis: Stop TB guidelines for social mobilization Geneva: World Health Organization; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Media Centre. Malaria Geneva: World Health Organization; 2009 (Fact sheet no. 94). Available from: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs094/en/index.html [accessed 14 July 2009].

- 15.Malaria background Geneva: The Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria; 2009. Available from: http://www.theglobalfund.org/en/malaria/background/?lang=en [accessed 14 July 2009].

- 16.Caulfield LE, de Onis M, Blossner M, Black RE. Undernutrition as an underlying cause of child deaths associated with diarrhea, pneumonia, malaria, and measles. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004;80:193–8. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/80.1.193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shimouchi A, Ozasa K, Hayashi K. Immunization coverage and infant mortality rate in developing countries. Asia Pac J Public Health. 1994;7:228–32. doi: 10.1177/101053959400700406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.State Resource Centre. Demographic trends and health policy: IMR and immunization Kolkata: State Resource Centre, Department of Health and Family Welfare, Government of West Bengal; 2007. Available from: http://www.srcwb.org/download/demographic/2007/July_IMR_and_Immunization.pdf [accessed 21 July 2009].

- 19.Parker S. Climate change, and health. Presented at the: Nova Scotia Communicable Disease Control Workshop, Halifax, Nova Scotia, 3–5March2009 Available from: http://www.gov.ns.ca/ohp/cdpc/resources/Climate_Change_and_Health.pdf [accessed 20 July 2009].

- 20.King LJ. The convergence of human and animal health: one world - one health. UMN Workshop, Minneapolis, 14May2008 Available from: http://www.localactionglobalhealth.org/Portals/0/Convergence%20-%20Minnesota%20-%20May%2014%20-%202008%20-%20LONNIE%20KING%20-%20One%20World%20One%20Health%20-%20Presentation.pdf [accessed 20 July 2009].

- 21.Mahjour J. Trend of communicable diseases in the EMR: 1978-2008 World Health Organization, Office of the Eastern Mediterranean Region. Available from: http://gis.emro.who.int/HealthSystemObservatory/Workshops/QatarConference/PPt%20converted%20to%20PDF/Day%203/PHC%20Emerging%20Priorities/Dr%20Jaouad%20Mahjour%20-20Trend%20of%20Communicable%20Diseases.pdf [accessed 14 July 2009].

- 22.United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific, United Nations Development Programme, Asian Development Bank. A future within reach 2008: regional partnerships for the Millennium Development Goals in Asia and the Pacific Bangkok: United Nations; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 23.World economic outlook update: global economic slump challenges policies Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund; 2009. Available from: http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/weo/2009/update/01/pdf/0109.pdf [accessed 6 June 2009].

- 24.Tolentino VBJ. Foreign aid and the global economic crisis The Asia Foundation; 2009. Available from: http://asiafoundation.org/in-asia/2009/04/01/foreign-aid-the-global-economic-crisis/ [accessed 20 May 2009].

- 25.Acharya KP. Global financial crisis and channels of its transmission to Nepal. Kathmandu: The Weekly Telegraph; 1 April 2009. Available from: http://www.telegraphnepal.com/news_det.php?news_id=5131 [accessed 20 May 2009].

- 26.Rahman M, Bhattacharya D, Iqbal MA, Khan TI, Paul TK. Global financial crisis discussion series, paper 1: Bangladesh London: Overseas Development Institute; 2009. Available from: http://www.odi.org.uk/resources/details.asp?id=3305&title=global-financial-crisis-bangladesh [accessed 20 May 2009].

- 27.Shiffman J. Donor funding priorities for communicable disease control in the developing world. Health Policy Plan. 2006;21:411–20. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czl028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Development aid at its highest level ever in 2008 Paris: Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development; 2009. Available from: http://www.oecd.org/document/35/0,3343,en_2649_34487_42458595_1_1_1_1,00.html [accessed 20 May 2009].

- 29.Miller T. Economic crisis may take toll on health services in developing nations. The Online News Hour, Public Broadcasting Service; 2009. Available from: http://www.pbs.org/newshour/updates/health/jan-june09/funding_02-06.html [accessed 20 May 2009].

- 30.Dodd R, Schieber G, Cassels A, Fleisher L, Gottret P. Aid effectiveness and health; making health systems work Geneva: World Health Organization; 2007 (Working paper no. 9).

- 31.The financial crisis and global health: report of a high-level consultation Geneva: World Health Organization; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chan M. Impact of financial crisis on health: a truly global solution is needed Geneva: World Health Organization; 2009. Available from: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/news/statements/2009/financial_crisis_20090401/en/index.html [accessed 20 May 2009].

- 33.Khoon CC. The social ecology of health and disease Presented at the Intensive Workshop on Health Systems in Transition, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 29–30 April 2009. Available from: http://cpds.fep.um.edu.my/events/2009/workshop/29042009/PPT%20&%20full%20paper/session%201/05%20-%20session_1-CCK.pdf [accessed 22 July 2009].

- 34.Kaufmann D. Aid effectiveness and governance: the good, the bad and the ugly Washington, DC: The Brookings Institution; 2009. Available from; http://www.brookings.edu/opinions/2009/0317_aid_governance_kaufmann.aspx [accessed 22 July 2009].

- 35.Global monitoring report. 2009: a development emergency Washington, DC: The World Bank Group; 2009. [Google Scholar]