Abstract

Problem

Antiretroviral therapy (ART) programmes have been successful in several countries. However, whether they would succeed as part of a national programme in a resource-constrained setting such as India is not clear. The outcomes and specific problems encountered in such a setting have not been adequately studied.

Approach

We assessed the efficacy and functioning of India’s national ART programme in a tertiary care centre in northern India. All ART-naive patients started on ART between May 2005 and October 2006 were included in the study and were followed until 31 April 2008. Periodic clinical and laboratory evaluations were carried out in accordance with national guidelines. Changes in CD4+ lymphocyte count, body weight and body mass index were assessed at follow-up, and the operational problems analysed.

Local setting

The setting was a tertiary care centre in northern India with a mixed population of patients, mostly of low socioeconomic status. The centre is reasonably well resourced but faces constraints in health-care delivery, such as lack of adequate human resources and a high patient load.

Relevant changes

The response to ART in the cohort studied was comparable to that reported from other countries. However, the programme had a high attrition rate, possibly due to patient-related factors and operational constraints.

Lessons learnt

A high rate of attrition can affect the overall efficacy and functioning of an ART programme. Addressing the issues causing attrition might improve patient outcomes in India and in other resource-constrained countries.

Résumé

Problématique

Les programmes de traitement antirétroviral (TARV) ont donné des résultats satisfaisants dans plusieurs pays. Néanmoins, il n'est pas certain qu'un tel programme réussisse dans le cadre du programme national d'un pays aux ressources limitées comme l'Inde. Les résultats et les problèmes spécifiques rencontrés dans ce type de contexte n'ont pas encore été suffisamment étudiés.

Démarche

Nous avons évalué l'efficacité et le fonctionnement du Programme TARV national indien dans le cadre d'un centre de soins tertiaires du Nord de l'Inde. Tous les patients auparavant naïfs de traitement ARV et ayant débuté ce traitement entre mai 2005 et octobre 2006 ont été inclus dans l'étude et ont été suivis jusqu'au 31 avril 2008. Des évaluations cliniques et analytiques périodiques ont été effectuées conformément aux directives nationales. Les évolutions de la numération des lymphocytes CD4+, du poids corporel et de l'indice de masse corporelle ont été évaluées dans le cadre du suivi et les difficultés opérationnelles ont été analysées.

Contexte local

L'étude s'est déroulée dans un centre de soins tertiaires du Nord de l'Inde, sur une population mixte de patients, dont la plupart présentaient un faible statut socioéconomique. Ce centre était raisonnablement bien doté en ressources, mais devait faire face à des contraintes dans la délivrance des soins, telles que le manque de personnel approprié et la forte affluence des patients.

Modifications pertinentes

La réponse au TARV dans la cohorte étudiée était comparable à celles rapportés dans d'autres pays. Néanmoins, le programme présentait un taux d'attrition élevé, pouvant être dû à des facteurs liés aux patients et aux contraintes de fonctionnement du centre.

Enseignements tirés

Un taux élevé d'attrition peut nuire à l'efficacité globale et au fonctionnement du programme TARV. Remédier aux problèmes à l'origine de cette attrition pourrait améliorer les résultats thérapeutiques pour les patients en Inde et dans d'autres pays à ressources limitées.

Resumen

Problema

Los programas de tratamiento antirretroviral (TAR) han cosechado buenos resultados en varios países. Sin embargo, no está claro si se desarrollarían también de forma satisfactoria como componente de un programa nacional en un entorno con recursos limitados como la India. Los resultados y los problemas específicos observados en esas circunstancias no han sido estudiados adecuadamente.

Enfoque

Se evaluó la eficacia y el funcionamiento del programa nacional de TAR de la India en un centro de atención terciaria del norte del país. Se incluyó en el estudio a todos los pacientes sin tratamiento antirretrovírico previo que empezaron a tomar antirretrovirales entre mayo de 2005 y octubre de 2006, los cuales fueron sometidos a seguimiento hasta el 31 de abril de 2008. De forma periódica se llevaron a cabo evaluaciones clínicas y de laboratorio de conformidad con las directrices nacionales. En cada sesión de seguimiento se analizaron la variación del recuento de linfocitos CD4+, el peso corporal y el índice de masa corporal, así como los problemas operacionales surgidos.

Contexto local

Se trabajó en un centro de atención terciaria del norte de la India con una población diversa de pacientes, la mayoría de nivel socioeconómico bajo. El centro cuenta con unos recursos razonables, pero ve tensionada su capacidad asistencial debido a la falta de recursos humanos apropiados y al alto volumen de pacientes.

Cambios destacables

La respuesta a la TAR en la cohorte estudiada fue comparable a la descrita en otros países. Sin embargo, el programa presentó una tasa de deserción elevada, posiblemente debido a factores relacionados con el paciente y a limitaciones operacionales.

Enseñanzas extraídas

Una alta tasa de deserción puede menoscabar la eficacia y el funcionamiento globales de los programas de ART. Encarando los problemas causantes de esas deserciones se podría conseguir que los pacientes evolucionaran mejor en la India y en otros países con recursos limitados.

ملخص

المشكلة

نجحت برامج المعالجة بمضادات الفيروسات القهقرية في عدة بلدان، إلا أن نجاحها كجزء من برنامج وطني في المناطق المحدودة الموارد مثل الهند مازال غير واضح، ولم تُدرس النتائج والمشاكل الخاصة التي يمكن مصادفتها في مثل هذه المناطق دراسة كافية.

الأسلوب

قيم الباحثون نجاعة ووظيفة البرنامج الوطني الهندي للمعالجة بمضادات الفيروسات القهقرية. وقد أدرج في الدراسة جميع المرضى الجدد المعالجين بمضادات الفيروسات القهقرية بدءاً من أيار/مايو 2005 حتى تشرين الأول/أكتوبر 2006، واستمرت متابعتهم حتى 31 نيسان/أبريل 2008. وأجري تقييم سريري ومختبري دوري لهم وفقاً للدلائل الإرشادية الوطنية. وقيست التغيرات في عدد اللمفاويات CD4+، ووزن الجسم، ومنسب كتلة الجسم أثناء المتابعة، وتم تحليل المشاكل الميدانية.

الحالة المحلية

كان الموقع مركزاً للرعاية الثالثية في شمالي الهند حيث يوجد خليط من المرضى، أغلبهم حالتهم الاجتماعية والاقتصادية منخفضة. وكان المركز جيد الموارد، ولكنه كان يواجه قيوداً في إيتاء الرعاية الصحية، مثل قلة الموارد البشرية، والعبء الضخم للمرضى.

التغيرات ذات الصلة

كان استجابة المعالجة بمضادات الفيروسات القهقرية في الأتراب الذين جرت دراستهم متشابهة مع بلاغات البلدان الأخرى. إلا أن البرنامج شهد معدل تناقص عال، وقد يرجع ذلك إلى عوامل لها صلة بالمرضى أو نتيجة للقيود الميدانية.

الدروس المستفادة

المعدل العالي للتناقص يمكن أن يؤثر على مجمل نجاعة ووظيفة برنامج المعالجة بمضادات الفيروسات القهقرية. وسيؤدي إيلاء الاهتمام بالمشاكل المؤدية لهذا التناقص إلى تحسين نتائج المرضى في الهند وفي المواقع المحدودة الموارد في البلدان الأخرى.

Introduction

The number of people infected with the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) worldwide was estimated to be 33.2 million at the end of 2007.1 The introduction of antiretroviral therapy (ART) has significantly reduced morbidity and mortality in HIV-infected patients in various developed and developing countries.2–5 However, the outcome of ART in India’s national ART programme has not been reported.

Background

India is a developing nation with approximately 2.4 million people living with HIV and a national prevalence of HIV infection in adults of 0.36%.1 Until 2004, ART was available only to a select subset of patients through the private sector; most of the HIV-infected population was unable to afford ART. India’s national ART programme was launched on 1 April 2004 under the National AIDS Control Organisation (NACO), as an initiative of the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare of the Government of India. The programme was launched in eight institutions in six states with a high prevalence of HIV infection, and in the National Capital Region of Delhi. By December 2008, 197 ART centres were functioning in 31 states and union territories and more than 193 000 patients were accessing free ART through these centres.6

Setting

To ascertain the functioning and efficacy of the national ART programme, we assessed an ART centre that was opened at the All India Institute of Medical Sciences (AIIMS) Hospital, New Delhi, in May 2005.

The AIIMS Hospital provides tertiary care to the population of Delhi and its neighbouring states, and most of its patients come from the lower socioeconomic strata. Patients with HIV infection tend to present in advanced stages of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) and are usually referred to the hospital’s ART centre, which is staffed by a nodal officer, two physicians, a laboratory technician, a pharmacist, a nurse (who also acts as an AIDS educator), an ART counsellor, a data manager and a community health worker. The centre receives financial and logistic support from NACO through the Delhi State AIDS Control Society.

This paper reports the outcomes of ART delivered from the clinic at the AIIMS Hospital and highlights some of the problems encountered in implementing ART.

Methods

To evaluate the effectiveness of the national ART programme at the AIIMS Hospital, we undertook a prospective observational study involving ART-naive patients who were started on ART between May 2005 and October 2006. ART was offered to these patients in accordance with NACO guidelines.7 The regimen consisted of two nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors and one non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor. The available drugs included efavirenz, lamivudine, nevirapine and zidovudine. The medications were dispensed directly to the patients or their authorized representatives.

Patients were seen 2 weeks after the start of ART and thereafter on a monthly basis. During each visit, patients were evaluated for drug toxicity, clinical improvement and opportunistic infections. Adherence was assessed during each visit by pill count, and, through counselling, patients were motivated to adhere to therapy. Patients who failed to turn up within a week of the scheduled visit were contacted by telephone. The CD4+ lymphocyte (CD4) count (cells/µl) was estimated at baseline and at 6-month intervals during follow-up. Prophylaxis and treatment of opportunistic infections were in accordance with NACO guidelines. Anti-tuberculosis treatment was administered according to the Revised National Tuberculosis Control Programme guidelines.8

Results

Between 1 May 2005 and 31 October 2006, 1325 patients were enrolled in the ART clinic. Of these patients, 631 treatment-naive adolescents and adults were eligible for the study. Baseline characteristics for those enrolled in the study are provided in Table 1. Patients had a mean age of 36 years (standard deviation, SD: 8.69); a mean weight of 54 kg in males (SD: ±10.03) and of 44 kg in females (SD: ±8.68); a mean body mass index of 19.25 kg/m² (SD: ±3.19); a mean haemoglobin of 11 g/dl (SD: ±2.38) and a median CD4 count of 110 (interquartile range: 59–159). All patients were followed until 31 April 2008; the median follow-up period was 21 months (range: 0–36 months). At the end of 36 months, 344 of the 631 patients (55%) were still being followed; 139 (22%) had been lost to follow-up, 77 (12%) had died and 71 (11%) had been transferred to other NACO-sponsored ART centres. Among those lost to follow-up, 60% were lost during the first 3 months and 84% by one year.

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of patients in a study of antiretroviral therapy outcomes in a tertiary care centre in northern India, 2005–2006.

| Characteristic | Value |

Characteristic | Value |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | % | No. | % | |||||||

| Total study population (n = 631) | Occupation | |||||||||

| Malesa | 502 | 80 | Unemployed | 218 | 34 | |||||

| Females | 129 | 20 | Unskilled worker | 131 | 21 | |||||

| Age (years) | Semi-skilled worker | 104 | 17 | |||||||

| 15–20 | 8 | 1 | Skilled worker | 52 | 8 | |||||

| 21–30 | 187 | 30 | Clerk/shop owner/farm owner | 93 | 15 | |||||

| 31–40 | 297 | 47 | Semiprofessional | 14 | 2 | |||||

| 41–50 | 99 | 16 | Professional | 19 | 3 | |||||

| > 50 | 40 | 6 | Mode of transmission | |||||||

| Malnourishedb | 219 | 44 | Blood transfusion | 37 | 6 | |||||

| Education | Heterosexual | 542 | 86 | |||||||

| Illiterate | 113 | 18 | Homosexual | 5 | 1 | |||||

| Primary school | 132 | 21 | Professional needlestick | 1 | 0.2 | |||||

| Middle school | 87 | 14 | Surgical | 2 | 0.3 | |||||

| High school | 120 | 19 | Unknown | 27 | 4 | |||||

| Intermediate schoolc | 78 | 12 | Unsafe injection | 12 | 2 | |||||

| Bachelor’s degree | 78 | 12 | WHO clinical stagee | |||||||

| Professional/post-graduate degree | 23 | 4 | 1 | 84 | 13 | |||||

| Monthly income (Indian rupees)d | 2 | 33 | 5 | |||||||

| < 40 | 4 | 1 | 3 | 320 | 51 | |||||

| 40–119 | 9 | 1 | 4 | 194 | 31 | |||||

| 120–199 | 17 | 3 | Anaemiaf | |||||||

| 200–299 | 52 | 8 | Male | 296 | 77 | |||||

| 300–399 | 97 | 15 | Female | 91 | 82 | |||||

| 400–799 | 224 | 36 | TB at the start of ART | 177 | 28 | |||||

| ≥ 800 | 228 | 36 | Initial ART regimen | |||||||

| Smoker | 63 | 10 | Stavudine + lamivudine + nevirapine | 312 | 49 | |||||

| Alcohol consumer | 22 | 4 | Stavudine + lamivudine + efavirenz | 99 | 16 | |||||

| Zidovudine + lamivudine + nevirapine | 153 | 24 | ||||||||

| Zidovudine + lamivudine + efavirenz | 67 | 11 | ||||||||

ART, antiretroviral therapy; TB, tuberculosis; WHO, World Health Organization. a The national data show a male to female ratio among the HIV-infected population of 61:39.9 b Malnutrition was defined by a body mass index (BMI) (kg/m²) < 18.5. c Intermediate school refers to the two years of education after high school in the 10 + 2 pattern of school education. d One United States dollar was equivalent to about 47 Indian rupees in May 2009. e Stages 3 and 4 are advanced stages of HIV infection. f For males, blood haemoglobin < 13 g/dl; for females, < 12 g/dl.

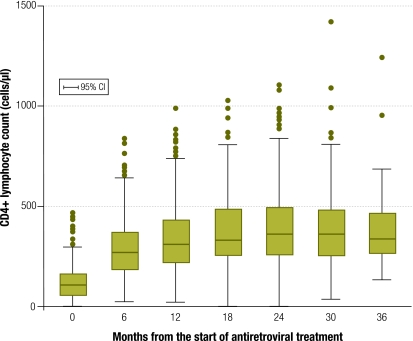

There was a consistent increase in the median CD4 count over the study period (Fig. 1). The CD4 count at 6 months was greater than the baseline value in 421 of 440 patients (96%). In total, 61% of patients gained weight, from a median of 50 kg at baseline to 57.5 kg at 36 months. Similarly, body mass index increased from a median of 19.2 at baseline to 21.6 at 36 months.

Fig. 1.

Changes in median CD4+ lymphocyte count over 36 months in a study of antiretroviral therapy outcomes in a tertiary care centre in northern India, 2005–2006

Survival analysis showed that 90% of the patients were alive at 6 months, 87% at 12 months and 84% at the end of 36 months. The overall mortality rate was 8.5 per 100 patient–years and the post-90-day mortality rate was 5.8 per 100 patient–years. There was no significant difference in survival between patients with and without tuberculosis (TB) (P = 0.623). A total of 192 patients (30%) required a change in their first-line medication. The most common reasons for this were initiation of anti-tuberculosis treatment (127 patients, 66%), adverse drug reactions (57 patients, 30%) and treatment failure (8 patients, 4%).

Discussion

This study confirms that ART delivery through a national programme in a resource-constrained setting can be effective. Most of the patients in the study showed a good clinical response to therapy, as indicated by significant weight gain and improvement in CD4 count. Around 82% of them had reached an advanced stage of illness (World Health Organization stage 3 or 4) at presentation, highlighting the need for early diagnosis and treatment. The overall mortality rate in our study was higher than reported from other developed and developing countries.10,11 Nevertheless, the post-90-day mortality rate was similar to the rate observed in another study.10

In line with previous studies, we found no significant association between TB and mortality.5,12 In a study from Uganda, TB was associated with increased mortality only in HIV patients with a CD4 count > 200 cells/µl.12 It may be that TB facilitates HIV viral replication to a greater extent in the earlier stages of HIV infection than during advanced illness, when viral replication is already at its peak. In our study, patients with TB had a mean baseline CD4 count of 109 cells/µl, indicative of advanced disease; this may explain why TB was not significantly associated with mortality. In addition, treatment for TB was rigorously supervised under the directly observed treatment strategy of the Revised National Tuberculosis Control Programme.

A major limitation of this study is that the causes of mortality were unknown; most deaths occurred at home and their exact causes could not be ascertained by telephone. Another limitation was the high number of patients lost to follow-up. This group requires special attention because it tends to have higher mortality, as shown in a recent review.13 The high loss to follow-up may have been linked to poverty (all patients had a monthly income of < 17 United States dollars), unemployment (34%) and a poor literacy rate (53% patients had not completed high school), coupled with poor awareness of AIDS and social stigma about the disease, as revealed by a similar study from India.14 Other deterrents to patient follow-up may have included initial improvement in health, adverse drug reactions and difficulties with transport (most patients came from distant areas with poor transport facilities). Currently, the only mechanism in the programme for retrieving patients lost to a treatment facility is to telephone them – an approach that is inadequate because of poor patient response or incorrect or outdated telephone numbers. Loss to follow-up during transfer of patients to other health-care facilities was another weak area in patient care.

The setting we studied had reasonable resources and was favourably located in an urban area. Nevertheless, we encountered difficulties such as limited human resources for handling the high patient load; lack of adequate space in the clinic for counselling, examination and investigations; difficulty in maintaining confidentiality due to lack of separate rooms; and lack of availability of second-line ART.

Potential solutions to the issues raised here include better education and motivation of patients, early referral for diagnosis and treatment, decentralization of the ART programme, institution of home visits, an increase in human resources and provision of adequate space in clinics, and greater availability of second-line ART for non-responders. Creating social support groups and a vibrant patient education programme, not only in the hospital but also in the communities near patients’ residences, would help dispel the misconceptions and stigma associated with HIV infection. Decentralizing the programme and providing travel reimbursement would undoubtedly increase attendance, and strengthening communication among local ART centres would enhance continuity in patient care. And while greater involvement on the part of nongovernmental organizations in HIV care and treatment would obviously be beneficial, it requires good audit and accountability systems to prevent the misuse of resources.

We feel that better treatment outcomes would be achieved by strengthening human resources in the centre, improving the infrastructure, diverting stable patients to peripheral ART centres and providing second-line ART for non-responders. Prioritizing sick HIV-infected patients for hospitalization may also lead to improved outcomes.

Box 1 summarizes the lessons learnt in this study.

Box 1. Summary of main lessons learnt.

Treatment outcomes observed in our study are comparable to those reported in previous studies in other settings and show that antiretroviral therapy (ART) delivery through a national programme in a resource-constrained setting can be effective.

A high attrition rate can affect the overall efficacy and functioning of an ART programme.

Addressing the issues causing attrition may improve patient outcomes in India and in countries with similar resource-constrained settings.

Conclusion

The treatment outcomes observed in our study are comparable to those reported in previous studies. Although the results are based on a limited number of patients and arriving at definitive conclusions may be premature, the results draw attention to certain important constraints that an ART centre would face in the Indian subcontinent. Such sociocultural and operational constraints need to be properly addressed, besides provision of free ART, to derive the complete benefit of ART through such a national programme. ■

Acknowledgements

We thank the NACO and the Delhi State AIDS Control Society for their work in establishing the ART centre at the AIIMS Hospital, New Delhi, and for providing financial and logistic support. The authors also thank residents, consultants, and other support and administration staff of the AIIMS Hospital.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.AIDS epidemic update: 2007 Geneva: Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS and World Health Organization; 2007. Available from: http://data.unaids.org/pub/EPISlides/2007/2007_epiupdate_en.pdf [accessed 30 May 2009].

- 2.Palella FJ, Jr, Delaney KM, Moorman AC, Loveless MO, Fuhrer J, Satten GA, et al. Declining morbidity and mortality among patients with advanced human immunodeficiency virus infection. HIV Outpatient Study Investigators. N Engl J Med. 1998;338:853–60. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199803263381301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mocroft A, Vella S, Benðeld TL, Chiesi A, Miller V, Gargalianos P, et al. Changing patterns of mortality across Europe in patients infected with HIV-1. EuroSIDA Study Group. Lancet. 1998;352:1725–30. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)03201-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Severe P, Leger P, Charles M, Noel F, Bonhomme G, Bois G, et al. Antiretroviral therapy in a thousand patients with AIDS in Haiti. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:2325–34. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa051908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stringer JS, Zulu I, Levy J, Stringer EM, Mwango A, Chi BH, et al. Rapid scale-up of antiretroviral therapy at primary care sites in Zambia: feasibility and early outcomes. JAMA. 2006;296:782–93. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.7.782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.National AIDS Control Organisation, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India. Operational guidelines for ART centres New Delhi: National AIDS Control Organisation, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India; 2008. Available from: http://www.nacoonline.org/upload/Care&Treatment/ART operational guidelines 2008.pdf [accessed 30 May 2009].

- 7.Antiretroviral therapy guidelines for HIV-infected adults and adolescents including post-exposure prophylaxis New Delhi: National AIDS Control Organization, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India; 2007. Available from: http://upaidscontrol.up.nic.in/Guidelines/Antiretroviral Therapy Guidelines for HIV infected Adults an.pdf.[accessed 30 May 2009].

- 8.Chauhan LS, Agarwal SP. Revised national tuberculosis control programme: TBC India Directorate General of Health Services, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India. Available from: http://www.tbcindia.org/pdfs/Tuberculosis Control in India.pdf [accessed 21 October 2009].

- 9.National AIDS Control Organisation [Internet site]. Available from: http://www.nacoonline.org/Quick_Links/HIV_Data/ [accessed 20 October 2009].

- 10.Stringer JS, Zulu I, Levy J, Stringer EM, Mwango A, Chi BH, et al. Rapid scale-up of antiretroviral therapy at primary care sites in Zambia: feasibility and early outcomes. JAMA. 2006;296:782–93. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.7.782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.The A. RT-LINC Collaboration and ART-CC Groups. Mortality of HIV-1- infected patients in the first year of antiretroviral therapy: comparison between low-income and high income countries. Lancet. 2006;367:817–24. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68337-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Whalen CC, Nsubuga P, Okwera A, Johnson JL, Hom DL, Michael NL, et al. Impact of pulmonary tuberculosis on survival of HIV-infected adults: a prospective epidemiologic study in Uganda. AIDS. 2000;14:1219–28. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200006160-00020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brinkhof MW, Pujades-Rodriguez M, Egger M. Mortality of patients lost to follow-up in antiretroviral treatment programmes in resource-limited settings: systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2009;4:e5790. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sarna A, Pujari S, Sengar AK, Garg R, Gupta I, Dam J. Adherence to antiretroviral therapy and its determinants amongst HIV patients in India. Indian J Med Res. 2008;127:28–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]