Abstract

Accumulating evidence supports the importance of redox signaling in the pathogenesis and progression of hypertension. Redox signaling is implicated in many different physiological and pathological processes in the vasculature. High blood pressure is in part determined by elevated total peripheral vascular resistance, which is ascribed to dysregulation of vasomotor function and structural remodeling of blood vessels. Aberrant redox signaling, usually induced by excessive production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and/or by decreases in antioxidant activity, can induce alteration of vascular function. ROS increase vascular tone by influencing the regulatory role of endothelium and by direct effects on the contractility of vascular smooth muscle. ROS contribute to vascular remodeling by influencing phenotype modulation of vascular smooth muscle cells, aberrant growth and death of vascular cells, cell migration, and extracellular matrix (ECM) reorganization. Thus, there are diverse roles of the vascular redox system in hypertension, suggesting that the complexity of redox signaling in distinct spatial spectrums should be considered for a better understanding of hypertension. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 10, 1045–1059.

Introduction

Signal transduction by electron transfer, or redox signaling, has been an emerging area of investigation in the cardiovascular field. Oxidation and reduction by loss or gain of an electron induce changes in structural and functional characteristics of molecules, thus modifying signaling processes. The major molecules that participate in redox signaling are reactive oxygen species (ROS) such as superoxide, hydrogen peroxide, hydroxyl radical, nitric oxide, and peroxynitrite. Recent redox signaling studies reveal that all the vascular constituents, including endothelial cells, vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs) and adventitial cells, as well as macrophages, generate ROS (150). ROS play key roles in signal transduction related to contraction and relaxation of blood vessels, growth, death and migration of vascular cells, and extracellular matrix (ECM) modifications.

Hypertension is classically defined as a chronic elevation of blood pressure that is determined by cardiac output and total peripheral vascular resistance. An increase in cardiac output is predominant in the initial stage of certain forms of hypertension. In the established phase of hypertension, however, cardiac output is near normal and peripheral resistance is elevated, even in the case of hypertension with little alteration in sympathetic activity or plasma renin activity. A major cause of enhanced peripheral resistance is alteration of vascular reactivity (i.e., enhanced stiffness and decreased compliance). Dysregulation of vasomotor function and structural remodeling of blood vessels are the main contributors to this impaired vascular function.

This brief review will summarize current concepts concerning vascular redox signaling involved in the pathogenesis and maintenance of hypertension, with particular emphasis on the role and function of ROS in the regulation of vascular tone and remodeling. Although redox signaling in the heart, kidney, and nervous system also contributes importantly to hypertension, they are beyond the scope of this review, and the reader is referred to excellent recent reviews on these topics (194, 222, 247). In general, understanding the mechanisms by which redox signaling regulates vascular function may provide a basis for more specific modulation of ROS as therapy for hypertension.

In Vivo Animal Models and Clinical Studies

A relationship between elevated ROS and hypertension has been clearly established in animal studies including surgically-induced and endocrine- or diet-induced animal models, as well as genetic models (12, 15, 41, 73, 90, 97, 158, 181). Of importance, similar findings were noted in clinical studies showing increased ROS production and decreased activity of antioxidants or ROS-scavenging enzymes in patients with essential, renovascular, or malignant hypertension, as well as preeclampsia (2, 75, 96, 105, 112).

Although an increase in oxidative stress as a consequence of hypertension is widely accepted, a potential causative role of ROS is more controversial. Indeed, oxidative stress may not explain the etiology of all types of hypertension, which is clearly a polygenic disease that develops through diverse mechanisms. Only a few clinical studies demonstrate a preventive effect of antioxidants (24, 54, 193), and not all experimental animal models of hypertension are related to oxidative stress (158). Furthermore, in contrast to the studies cited above, some clinical studies show a negative correlation between oxidative stress markers and blood pressure in patients with mild-to-moderate hypertension (34). While it is difficult to establish a cause–effect relationship between oxidative stress and hypertension in clinical studies, there is some evidence suggesting enhanced oxidative stress is a risk factor for human hypertension (2).

Animal studies, in contrast, generally support a causal link between ROS and hypertension. Antioxidants, ROS-scavenging enzymes, and functional deletion of ROS-generating enzymes have all been shown to reduce blood pressure in rodents. Chronic treatment of spontaneously hypertensive rats (SHR) with the antioxidant N-acetylcysteine (NAC) reduces blood pressure effectively in young (5W) rats, although it is not effective in older rats (12W) with established hypertension (153), suggesting that ROS may play a role in the early stages of hypertension development. This is supported by the observation that chronic treatment with the superoxide scavenger tempol also blocks the age-related development of high blood pressure in SHR (137). Moreover, hypertension induced by angiotensin II (Ang II) is significantly blunted by knockout of the NADPH oxidase components p47phox or Nox1 (40, 128). In addition, excess oxidative stress following GSH depletion by L-buthionine sulfoximine treatment is sufficient to elevate blood pressure in normal Sprague–Dawley rats (12, 210). As a whole, these studies suggest that an increase in ROS or oxidative stress is sufficient to cause high blood pressure, even though it is not necessary for the development of all types of hypertension. Hence, increased oxidative stress seems to be both a cause and a consequence of hypertension.

Oxidative stress can result not only from increased ROS production, but also from decreased ROS scavenging ability. The vascular system possesses diverse antioxidant systems, including the superoxide dismutase (SOD) family, catalase, the glutathione (GSH) system, thioredoxin, peroxiredoxin, and ROS scavengers such as vitamins A, C, and E (191). Hypertension is reported to be associated with decreased antioxidant systems as well as enhanced production of ROS. The activity of SOD, catalase, and GSH peroxidase is significantly lower, and the GSSG/GSH ratio is higher, in whole blood and peripheral mononuclear cells from hypertensive patients compared with those of normotensive subjects (162), and all of these parameters are restored after antihypertensive treatment (169). Similar results have been reported in other studies that show decreased SOD activity in red blood cells or plasma from patients with essential hypertension (180, 240). However, these observations do not answer the question of whether an impaired antioxidant system contributes to the development of hypertension, or is a consequence of excess oxidative stress related with hypertension. Recently, genetic variations in the promoter region of the catalase gene were found to be related with increased susceptibility to essential hypertension (242). Moreover, inhibition of GSH synthesis leads to elevation of blood pressure in normotensive rats (243), and extracellular-SOD (EC-SOD) knockout in mice is enough to elevate baseline blood pressure in the absence of any other treatment (221). These results raise the possibility that a decrease in antioxidant capacity is sufficient to cause hypertension.

A broad range of mediators of hypertension has been investigated, including the renin–angiotensin system and hormones such as vasopressin and glucocorticoids. With regard to ROS, Ang II has been the most widely investigated factor, although recently, endothelin (ET) was proposed to be an important mediator of hypertension (156, 163) that requires ROS. ET is a potent vasoconstrictor and mitogen that has been implicated in hypertension by studies showing that renal or plasma levels of ET-1 are increased in hypertensive animal models, including Ang II-induced hypertensive rats (3, 171), stroke-prone SHR (SHRSP), deoxycorticosterone acetate-salt (DOCA-salt)-induced hypertensive rats, and one kidney-one clip hypertensive rats (1). More importantly, ET-1 treatment is sufficient to induce hypertension (175), and administration of an ETA receptor antagonist improves high blood pressure and endothelial dysfunction in DOCA-salt- and Ang II-induced hypertension (4, 35, 107, 147, 159), although some controversy exists (43, 215). In clinical studies, ET-1 has been suggested to contribute to the development and maintenance of hypertension in a salt-sensitive population (44). Recently, oxidative stress markers such as thiobarbituric acid reactive species (TBARS) and urinary 8-isoprostaglandin F2α were found to be increased in ET-1-induced hypertension (175), and ET-1 was reported to increase superoxide generation in pulmonary arterial smooth muscle cells (SMCs) (219), isolated rat aorta (117), and the vasculature of DOCA-salt-induced hypertensive rats (21, 107). A contribution of ROS to ET-1-induced hypertension is supported by the antihypertensive effect of tempol on ET-1-induced hypertension (175). An ETA receptor antagonist, BMS 182874, also decreases both ROS and blood pressure in DOCA-salt hypertension (21). Activation of NADPH oxidases, eNOS uncoupling, and mitochondrial generation of ROS have been suggested as mechanisms for ET-1-induced ROS production in different experimental systems (20, 43, 107, 117), and ROS are known to be responsible for increased ET-1 production in hypertension (45, 53, 84, 171). Excess ET-1 production is also responsible for telomerase-deficient hypertension, in which endothelin-converting enzyme-1 (ECE-1) overexpression caused by NADPH oxidase-derived ROS is suggested as a potential mechanism (154). A more comprehensive understanding of relationship between ROS and ET-1 is needed for elucidation of mechanisms underlying ET-1-mediated blood pressure control.

Generation of ROS in the Vasculature

Virtually all vascular cells produce ROS, which then have the potential to contribute to the pathogenesis of cardiovascular diseases. Although numerous enzyme systems generate ROS, several of them are known to be predominant in pathologic processes. These include NADPH oxidases, uncoupled endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS), xanthine oxidase (XO), myeloperoxidase, lipoxygenase, cyclooxygenase, cytochrome P450, heme oxygenase, and the mitochondrial respiratory chain. Some of these systems have been proven to be relevant to hypertension.

NADPH oxidases

NADPH oxidases (Nox) are enzymes composed of multi-protein complexes, which produce superoxide by electron transfer from NADPH to molecular oxygen. Nox proteins (gp91phox homologues), combined with p22phox, represent the membrane-bound catalytic complex. Nox1, Nox2 (gp91phox), Nox4, and Nox5 (which does not bind p22phox) are the major NADPH oxidase constituents in vasculature. Their expression and distribution are variable, depending on the segment of vascular bed and cell type, and even in the same cell, distribution is not uniform but is compartmentalized in specific subcellular regions (76). Regulatory mechanisms and signaling pathways for activation are also different, which is in part due to the diversity of cytosolic regulatory subunits, including p47phox, p67phox, Rac, Noxo1, and Noxa1. In addition, protein disulfide isomerase (PDI), a dithiol/disulfide oxidoreductase chaperone of the thioredoxin superfamily, was recently shown to be a new regulator of Nox activity by affecting subunit trafficking/assembly (80). With such diversity in distribution and regulatory mechanisms, it is not surprising that NADPH oxidases with different homologues of Nox have distinct functions.

NADPH oxidases are well known to be important sources of ROS in blood vessels. Increased expression and activity of NADPH oxidase or its subunits have been described in hypertensive animal models, including Ang II-induced hypertensive rats (52), SHR (233), DOCA-salt hypertensive rats, and two-kidney two-clip renovascular hypertensive rats (15, 99, 158). Furthermore, NADPH oxidase inhibition by gp91ds-tat attenuates blood pressure as well as ROS production (164). Deletion of p47phox, the cytosolic regulatory subunit of several of the NADPH oxidases, renders mice resistant to Ang II-induced hypertension (97, 106) and blunts the increase in ROS production. Additionally, Rac1 overexpressing mice develop moderate hypertension that is suppressed by NAC treatment, suggesting that an increase in ROS generation by NADPH oxidases predisposes to hypertension (71). This interpretation is consistent with the finding that p47phox expression is already increased in young (4W), prehypertensive SHR, as well as adult SHR (25). According to recent studies, genetic deletion of Nox1 and conditional overexpression of Nox1 in VSMCs diminishes or augments blood pressure elevation induced by Ang II infusion, respectively, without affecting basal blood pressure (40, 128). Further research will be needed to clarify the contribution of each Nox isoform or regulatory subunit to hypertension.

The involvement of NADPH oxidases in hypertension is also well documented in clinical studies that report an increase in NADPH oxidase and/or NADPH oxidase-derived ROS in tissues derived from hypertensive patients (50, 155, 207). Recently, a genetic polymorphism in CYBA, the gene encoding p22phox, was reported to be associated with hypertension. In particular, the −930A/G polymorphism has been suggested to be a novel marker which determines the genetic susceptibility of hypertensive patients to oxidative stress (234). This supports a possible causative role of NADPH oxidases in the development of hypertension.

Uncoupled endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS)

eNOS produces NO by oxidizing L-arginine to L-citrulline in normal conditions. For complete function, eNOS requires homo-dimerization, the substrate L-arginine, and essential co-factors such as tetrahydrobiopterin (BH4). Under certain circumstances, however, eNOS transfers electrons from NADPH to the oxygen molecule instead of L-arginine, resulting in the formation of superoxide instead of NO, which is called ‘uncoupling’ of eNOS. Uncoupling of eNOS in hypertension has been observed in the endothelium of peroxynitrite-treated rat aorta (103), and in blood vessels of SHR (32), SHRSP (88), and Ang II- (132) and DOCA-salt induced hypertensive rats (98), all of which show eNOS-dependent superoxide production.

Although eNOS uncoupling is attributed to diverse mechanisms in experimental conditions, a decrease in BH4 bioavailability is the most important mechanism in physiological or pathological conditions (49). Indeed, a decrease in BH4 levels is found in vascular tissue from DOCA-salt hypertensive rats (98). BH4 is highly susceptible to oxidation by ROS such as peroxynitrite; hence, oxidative stress is a major mechanism for uncoupling of eNOS (94). Considering the rapid reaction of superoxide and NO to form peroxynitrite, eNOS uncoupling may amplify further uncoupling via a feed-forward mechanism by generation of peroxynitrite. In fact, it has been proposed that initial activation of NAPDH oxidases provides superoxide that reacts with eNOS-derived NO and leads to eNOS uncoupling in hypertension (98). Another mechanism underlying decreased BH4 bioavailability is impaired biosynthesis and/or increased degradation. Decreased vascular BH4 levels and impaired endothelial function in low renin hypertensive rats can be restored by gene transfer of guanosine 5’-triphosphate cyclohydrolase I, one of the rate-limiting enzymes involved in BH4 biosynthesis (239). In addition, it was reported recently that Ang II treatment causes eNOS uncoupling via induction of BH4 deficiency by the downregulation of dihydrofolate reductase, another critical enzyme in synthesis of BH4. This downregulation is caused by NADPH oxidase-derived H2O2 (26), suggesting another mechanism for cross-talk between these enzyme systems. This study also raises the possibility that the contribution of eNOS uncoupling to ROS production might be underestimated in experiments measuring endothelial ROS generation by NADPH oxidase. At any rate, oral administration of BH4 improves endothelial dysfunction and high blood pressure effectively in DOCA-salt hypertensive mice and hypertensive individuals, suggesting that eNOS uncoupling contributes importantly to some forms of hypertension (74, 98).

Xanthine oxidase

Xanthine oxidase (XO) is another potential source for ROS in vasculature (133). XO is a form of xanthine oxidoreductase that occurs in two different forms. The predominant form, xanthine dehydrogenase (XDH), can be converted into XO reversibly by direct oxidation of critical cysteine residues or irreversibly by proteolysis (14, 70, 170). XO is expressed mainly in the endothelium, and its expression and activity are increased by Ang II or oscillatory shear in a NADPH oxidase-dependent manner (100, 129). A role for XO in hypertension has been deduced from the presence of high serum urate levels, a marker for XO activity, in long-term essential hypertension (22). Unlike NADPH oxidases, however, the general importance of XO in hypertension has not been clearly established. Increased XO activity has been suggested to be a risk factor for hypertension (140), and is found in gestational hypertensive patients (139). Oxypurinol, a XO inhibitor, however, fails to improve impaired endothelial function in essential hypertensive patients (23). In animal experiments with SHR, dexamethasone-induced hypertensive rats and Dahl salt-sensitive rats, hypertension is improved effectively by treatment with XO inhibitors such as allopurinol, (-)BOF4272, and tungsten (138, 188, 190, 213). In contrast, another study found that allopurinol treatment does not affect blood pressure of SHR despite elevated XO activity in the SHR kidney (95). The potential role of XO in hypertension thus remains unclear.

Mitochondrial electron transport

Mitochondrial electron transport generates superoxide as a side product of electron transport during oxidative phosphorylation. Most superoxide never escapes the highly reducing state of the mitochondrial matrix. If the superoxide generation is excessive, however, superoxide can escape to the intermembraneous space and cytosol via anion channels (9). Although ROS originated from mitochondria are reported to contribute to endothelial dysfunction, atherosclerosis, hyperglycemia, and aging (11, 142, 161, 174), few data relevant to hypertension are available. Partial deficiency of SOD2, the mitochondrial SOD isoform, induces spontaneous hypertension in aged mice and accelerates the development of high salt-induced hypertension (167). Additionally, the basal blood pressure of transgenic mice that conditionally over-express mitochondrial thioredoxin (Trx), Trx2, in the endothelium is lower than that of control mice (237). These results imply a possible contribution of mitochondria-originated ROS to blood pressure regulation, but additional work is needed.

Role of ROS in Vascular Tone Regulation

Alteration of vascular reactivity characterized by augmented contractility and impaired relaxation is a prominent feature in hypertension. It contributes to an elevation of vascular tone, which, in turn, results in enhancement of peripheral arterial resistance. The effects of ROS on vascular tone are not uniform because of the diversity of signaling molecules involved in tonal regulation. They are also dependent upon the concentration and species of reactive oxygen, vascular beds, species, experimental conditions, and other incompletely defined conditions. Both VSMC contraction and endothelial regulatory functions are directly or indirectly modified by oxidative stress. As a whole, superoxide and H2O2 seem to favor vasoconstriction and attenuate endothelium-dependent dilation (87); however, there is abundant opposing evidence as well. In the mesenteric artery (51, 55, 125), coronary artery (172, 203), and pulmonary artery (19) of various species, H2O2 induces vasodilation, and, even in the same artery, either constriction or relaxation can be induced depending on experimental conditions (118).

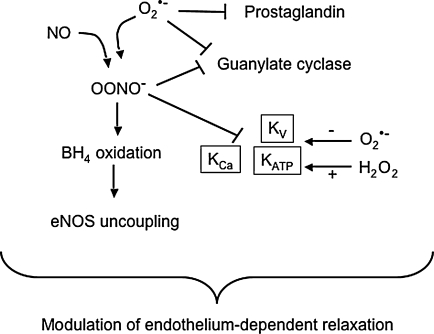

ROS can inhibit the two major endothelium-derived relaxing factors, NO and prostacyclin (Fig. 1). As noted previously, superoxide reduces the bioavailability of NO by reacting with NO to generate peroxynitrite (136, 157), which is a major mechanism for endothelial dysfunction caused by ROS. Reduction of NO bioavailability in hypertension has been demonstrated in various types of experimental animal models as well as clinical studies (48). Peroxynitrite contributes to eNOS uncoupling by oxidizing BH4 (246), inactivates prostacyclin synthase by tyrosine nitration of its active site (244, 245), and further enhances oxidative stress by inhibiting superoxide dismutase (5). In addition, superoxide and peroxynitrite inhibit expression and activity of guanylate cyclase, an effector molecule of NO in VSMCs (136), which is well correlated with the finding that endothelium-independent vasodilation as well as endothelium-dependent dilation are impaired in hypertensive animals (158).

FIG. 1.

Regulation of endothelium-dependent vasodilation by ROS. Superoxide not only inactivates NO, but also inhibits prostacyclin, decreases guanylate cyclase expression, and blocks KATP and Kv channels. In contrast, H2O2 opens these channels. By interacting with NO to form peroxynitrite, superoxide also oxidizes the eNOS cofactor tetrahydrobiopterin and inhibits KCa and Kv channels.

Hyperpolarization of VSMCs is also an important mechanism for vasodilation, which is mainly achieved by the opening of K+ channels (Fig. 1). VSMCs express several different types of K+ channels, including Ca2+-activated K+ channels (KCa), ATP-sensitive K+ channels (KATP), and voltage-dependent K+ channels (Kv) (204). Activation of KCa is known to be a negative feedback mechanism limiting Ca2+-induced vasoconstriction and mediates the response to endothelium-derived hyperpolarization factor (EDHF) (204). KATP limits myogenic depolarization and controls myogenic reactivity (201), and Kv contributes to resting vasomotor tone and cAMP-mediated vasodilation (67). K+ channels have differential sensitivity to oxidative stress, depending on the species of oxidant and types of channels. Superoxide inhibits the opening of KATP and KV, and the activity of KCa and KV are impaired by peroxynitrite, which would tend to lead to depolarization and contraction (67, 114). In contrast, H2O2 mainly acts on KCa to induce either inhibition or activation (13, 16, 78, 182, 195, 203), although the determinant of these opposite effects has not been elucidated clearly. Based on its ability to activate K+ channels, several investigators proposed H2O2 as an EDHF (125–127, 225). Altered VSM depolarization has been reported in different models of hypertension such as essential hypertension, SHR, DOCA-salt- and NOS-inhibition-mediated hypertension, and a change in K+ channel activity has been demonstrated as major contributor to impaired relaxation or exaggerated contraction (6, 17, 33, 59, 120, 121). Decreased K+ channel activity or impaired K+ channel activation may thus contribute to increased vascular contractility, which is well correlated with the enhanced contraction or impaired vasorelaxation to H2O2 in hypertension (56, 168).

ROS also directly regulate smooth muscle contraction by mechanisms other than K+ channel modulation. These include Ca2+ mobilization, MAPK activation, and Ca2+-sensitization of the contractile machinery. Experimentally, the function of most Ca2+ transport systems can be affected by ROS, which has been demonstrated in various types of cells (93). Molecular mechanisms include direct oxidative modification of the sulfhydryl groups in the active site of the transport protein, indirect control of transport activity by modification of regulatory subunits or molecules, and alteration of intracellular ATP levels, influencing energy-dependent transport activity (206). Both superoxide and H2O2 can increase intracellular Ca2+ by mobilizing extracellular Ca2+ via activation of L-type voltage-gated Ca2+ channels (192). L-type voltage-gated Ca2+ channel-mediated promotion of Ca2+ influx by superoxide contributes to spontaneous aortic tone in Ang II-induced hypertensive rats. In addition to an increase in its activity, elevated expression of this channel by H2O2 is also a potential mechanism for enhanced cytosolic Ca2+ levels in VSMCs isolated from SHR (192). Likewise, superoxide or H2O2 can mobilize Ca2+ from the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) through activation of ryanodine receptor (RyR) or the inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate (IP3) receptor (IP3R) (46, 63, 189). In addition, several studies demonstrated an inhibitory effect of ROS on the plasma membrane Ca2+-ATPase (PMCA) (64, 232) and the sarco/endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase (SERCA) (63–65, 85). PMCA and SERCA extrude cytosolic Ca2+ across plasma membrane and mediate Ca2+ mobilizaton back into the sarcoplasmic reticulum, respectively. Hence, inhibition of PMCA or SERCA would result in an increase in cytosolic Ca2+ by superoxide and H2O2. Taken together, these studies show that ROS favor cytosolic Ca2+ accumulation through modulation of Ca2+ transport systems, thereby leading to direct contraction or potentiation of contractility of VSMCs.

Contraction of VSMCs is mainly achieved via phosphorylation of the myosin light chain (MLC), which is mediated by the Ca2+/CaM-dependent MLC kinase (MLCK), followed by activation of the actin-activated myosin Mg2+-ATPase, triggering cross-bridge cycling. In addition to MLCK, MLC phosphorylation is regulated by myosin phosphatase, which in turn is regulated by Rho/Rho-kinase. Activation of Rho/Rho-kinase inactivates myosin phosphatase, resulting in enhanced phosphorylation of MLC and Ca2+-independent contraction, which is known as Ca2+-sensitization of VSMCs. Augmented activity of Rho-kinase is implicated in the increased peripheral vascular resistance in human hypertension (123). Increased expression and activity of Rho-kinase accompanied by myosin phosphatase inactivation is also described in experimental animal models, including SHR, DOCA-salt- and Ang II-induced hypertensive rats, renal hypertensive rats, and SHRSP (81, 134, 176, 220). Functional upregulation of Rho-kinase is related to hyperactivity of hypertensive blood vessels (134). ROS generated by X/XO induce Ca2+-sensitization through activation of Rho/Rho-kinase in rat aorta (82), and the same mechanism is implicated in the contraction of veins by H2O2 (202). Recently, the Rho-kinase inhibitor, Y27632 was shown to suppress the spontaneous tone of endothelium-denuded aortas from Ang II-induced hypertensive rats (81). In addition, treatment with the NADPH oxidase inhibitors DPI and apocynin abolishes such spontaneous tone, suggesting NADPH oxidase-derived ROS are responsible for RhoA/Rho-kinase-mediated development of vascular tone in hypertension (81).

As noted previously, NADPH oxidase-derived H2O2 or exogenous H2O2 sometimes induce vasoconstriction, which is mediated by mitogen-activated protein kinases such as ERK1/2 (145, 146) and p38 (118). Both MLCK activation and myosin phosphatase inactivation can be induced by ERK1/2 and p38, leading to an increase in MLC phosphorylation. In addition, caldesmon, integrin-linked kinase (ILK), and zipper-interacting-like kinase (ZIP kinase) have been suggested to be involved in ROS-induced, MAPK-mediated vasoconstriction (10).

Role of ROS in Vascular Remodeling

Vascular remodeling is defined as modification of structure leading to alteration in wall thickness and lumen diameter. It can be induced through passive adaptation to chronic changes in hemodynamics and/or through neurohumoral factors including Ang II and ROS. The progression of hypertension involves two different types of vascular remodeling: inward eutrophic remodeling and hypertrophic remodeling (173). Eutrophic remodeling is characterized by reduced lumen size, thickening of the media, increased media:lumen ratio and, usually, little change in medial cross-sectional area. In this case, the change in VSMC size is negligible (92), and medial growth toward the lumen is mainly mediated by reorganization of cellular and noncellular material of the existing vascular wall, accompanied by enhanced apoptosis in the periphery of the blood vessel (166). This is common in small resistance arteries of essential hypertensive patients and SHR (92, 135). On the other hand, hypertrophic remodeling characterized by an increase in wall cross-sectional area predominates in conduit arteries of secondary hypertension, such as those of renovascular hypertensive patients or Ang II-infused hypertensive rats. An increase in cell size and enhanced accumulation of ECM proteins such as collagen and fibronectin are specific features of hypertrophic remodeling (42, 165). Hence, VSMC hypertrophy and ECM synthesis are required for hypertrophic remodeling. Both mechanical wall stress and humoral mediators such as Ang II contribute to hypertrophic remodeling (72, 116, 165, 205).

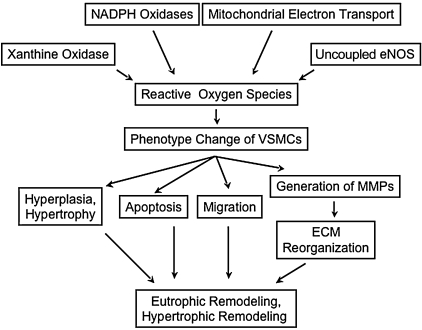

Both forms of remodeling frequently coexist in different vascular beds and at different stages of hypertension, even in the same individual. Although the determinants of each type of remodeling have not been elucidated clearly, the reorganization of media mediated by phenotype modulation of VSMCs, migration, cellular growth, apoptosis, and ECM production and rearrangement is thought to be common to both processes (Fig. 2). These events occur cooperatively and simultaneously; therefore, it is not easy to distinguish contributions of each component in vivo. Vascular remodeling is improved by treatment with tempol, antioxidant vitamins (27), Ang II receptor antagonists, or NADPH oxidase inhibitors in animal experimental models, as well as in clinical trials (101, 241), emphasizing the role of ROS.

FIG. 2.

ROS-mediated contribution of vascular smooth muscle cells to vascular remodeling in hypertension. Phenotypic modulation of vascular smooth muscle is central to the development of remodeling in hypertension. ECM, extracellular matrix; MMPs, matrix metalloproteinases.

Phenotype modulation

VSMCs within mature blood vessels express a unique repertoire of contractile proteins, and possess low proliferative capability and synthetic activity. During development or in pathological conditions such as vascular injury, highly differentiated VSMCs exhibit structural and functional changes, including loss of their contractile machinery and a high rate of cellular growth, migration, and production of ECM components such as collagen and fibronectin, which together describe ‘phenotype modulation’ (148). This phenotypic change of VSMCs predisposes them to hypertrophy, exaggerated proliferation, and increased production of ECM proteins in hypertension. The primary evidence for the involvement of phenotype switching in hypertension is the enhanced proliferation (68, 77) and hypertrophy accompanied by polyploidy (149) of VSMCs derived from SHR. Hyperplasia of aortic SMCs is also seen in renovascular hypertensive rabbits (152). In addition, in an animal study using SHRSP (31) and in a clinical report of primary pulmonary hypertension (131), phenotype changes of VSMCs have been detected using markers for the proliferative phenotype (fibronectin and nonmuscle myosin). Although the driving forces for phenotype switching are not fully understood, physical and chemical changes in the environment have been suggested as causes of phenotypic modulation, including humoral factors such as growth factors (PDGF, TGFβ-1), contractile agonists (Ang II, ET-1), and neuronal signals. In addition, chemically- or physically-induced vascular injury, and changes of mechanical forces inducing alteration of cell–cell interaction and ECM structure, can induce phenotype switching (148).

The role of ROS in phenotypic modulation in hypertension has not been examined in detail. Superoxide is reported to enhance collagen production in VSMCs, which suggests that ROS favor the synthetic property of VSMCs (151). Indeed, hypertrophy, proliferation, and migration, functions characteristic of the synthetic phenotype, are enhanced in VSMCs that have elevated H2O2 production resulting from overexpression of p22phox (187). However, catalase and NAC block the induction of calponin, SM α-actin, and smooth muscle myosin heavy chain in response to serum withdrawal in VSMCs, suggesting that H2O2 also mediates differentiation in these cells (184). A possible explanation for this paradox may lie in the subcellular localization of the ROS signal. A recent study demonstrated that Nox4-derived ROS are critical for the maintenance of the differentiated phenotype of VSMCs, whereas Nox1 expression is inversely correlated with the expression of differentiation markers (29). This implies that localization of ROS signal is a critical determinant of cellular response, which is supported by two previous papers showing differential subcellular localization of Nox1 and Nox4 in VSMCs (76), and a positive role for Nox1 (but not Nox4) in serum-induced proliferation and Ang II-stimulated hypertrophy in VSMCs (102, 185). Further investigation into the spatial diversity of redox signaling is needed.

Extracellular matrix reorganization

Vascular remodeling also entails degradation and reorganization of the ECM in the vasculature. Although several classes of proteases have been suggested to be associated with ECM reorganization, the most important enzymes are matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs). MMPs are a group of zinc-dependent endopeptidases that are capable of degrading most ECM proteins in blood vessels, such as collagen, gelatin, and fibronectin. Existing within the ECM, MMPs play crucial roles in the dynamics of the ECM by degrading, or “loosening” the ECM structure. A decrease in MMPs was postulated to increase vascular fibrosis (104), and high levels of MMPs were proposed to be related with vascular remodeling through active turnover of ECM (183). Several studies have focused on the relationship between hypertension and MMPs, but there seems to be conflicts over clinical data. Plasma levels and activity of MMP-2 and MMP-9 are decreased in patients with essential hypertension (104, 111, 235, 236) and with pulmonary hypertension (58), whereas increased circulating levels have been described in other studies investigating patients with essential hypertension (36, 122, 198, 199) and gestational hypertension (197). Increased levels of MMP-2 and MMP-9 in serum are reported to be well correlated with arterial stiffness in hypertensive patients (228), and in aortic tissue from SHR, there is a significant increase in activity and expression of MMP-2 (183). More work is clearly necessary to resolve this issue.

It is noteworthy that superoxide and H2O2 increase the expression and activation of MMP-2 and MMP-9 in VSMCs (66, 160). X/XO activates MMP-2, and the redox cycler, 2,3-dimethoxy-1,4-naphthoquinone (DMNQ), induces MMP-1 in VSMCs (18, 113). Ang II stimulates secretion of MMP-1, MMP-3, and MMP-9 in human saphenous vein SMCs in a NADPH oxidase- and ROS-dependent manner (18). NADPH oxidase-derived ROS are also responsible for the increase in expression and release of MMP-2 by mechanical stretch, a hallmark of arterial hypertension (62). Taken together, in vitro studies raise the possibility that ROS may contribute to ECM reorganization through enhancing expression and activity of members of the MMP family, although the clinical or in vivo relevancy of these observations to hypertension remains to be clarified.

Migration

Vascular remodeling involves migration of VSMCs along with phenotype change and ECM reorganization. VSMC migration can be induced by a diverse range of chemoattractants, including PDGF, VEGF, thrombin, Ang II, MCP-1, arachidonic acid, and α-adrenoceptor agonists such as phenylephrine. ROS is involved in migration by acting as a second messenger, as demonstrated by the inhibitory effects of catalase, SOD, NAC, pyrrolidine dithiocarbamate, and ebselen (60, 115, 143, 186, 216, 217). Indeed, H2O2 treatment is sufficient to induce SMC migration (89), and internal mammary arterial SMCs, which possess a high antioxidant capacity, resist migration induced by PDGF and Ang II (119). Additionally, in coronary SMCs, physical pressure promotes migration, and HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors prevent migration through potentiation and suppression of oxidative stress, respectively (229, 230). The particular involvement of NADPH oxidases has been demonstrated in recent studies. PDGF-stimulated migration is inhibited by a newly-developed Nox inhibitor, VAS2870 (200), and similar effects are obtained with DPI and apocynin in Ang II-, MCP-1-, or thrombin-induced migration (224, 227). In parallel with these findings, genetic knockout of Nox1 or Nox4 impairs PDGF-induced migration in rodent VSMCs (unpublished data), and p22phox overexpressing cells show an enhanced migratory activity (187), suggesting a pivotal role of NADPH oxidases in VSMC migration.

The mechanisms underlying ROS-mediated VSMC migration are poorly understood. Signaling molecules including non-receptor tyrosine kinases, Src, PKC, PLD, MAPKs such as ERK1/2 and p38, NF-κB, and Akt have been suggested as key mediators of ROS-mediated migration (57, 89, 115, 216, 217, 224). Recently, the Src/PDK1/PAK1 signaling axis was identified as a major signaling route in PDGF-stimulated, ROS-sensitive VSMC migration (218).

Cellular growth and apoptosis

Redox signaling is also associated with cellular growth, senescence, and death (30, 108). Exogenous treatment with ROS results in diverse effects on VSMCs, inducing proliferation, growth arrest, or apoptosis in different studies. It is generally accepted that cellular growth is induced at exposure to low concentrations of ROS, whereas a greater extent of ROS treatment results in death. In other studies, superoxide was found to induce proliferation, but H2O2 treatment resulted in growth arrest or apoptosis in VSMCs (109, 141), suggesting that different oxidant species may have different functions.

ROS function as mediators of VSMC growth contributing to vascular remodeling during hypertension (40, 214, 231, 238). Although both hypertrophy and hyperplasia are associated with the remodeling process, the roles of ROS in hyperplasia and hypertrophy are complicated and are not clearly distinguished. Superoxide generated by the X/XO system is known to stimulate VSMC proliferation (108, 141), but, in a recent study, a much lower level of superoxide than that inducing proliferation was found to lead to hypertrophy instead of proliferation in VSMCs, characterized by enhanced cell size and protein synthesis (124). Apparently, ROS serve as an intracellular signaling messenger to stimulate growth via mechanisms common to natural growth factors (223). For example, H2O2 treatment induces phosphorylation of the PDGFβ receptor, Akt, and MAPK p42/44, which can be blocked by NAC (86), and NADPH oxidase-derived superoxide mediates Ang II-induced hypertrophy of VSMCs (231). Overexpression of Cu/Zn-SOD and/or catalase efficiently inhibits epidermal growth factor (EGF)-induced VSMC proliferation (179). ERK1/2 (186), p38 (208), JNK, and Akt/PKB are known to be the key redox-sensitive signaling molecules related to VSMC growth (61, 179, 209).

Apoptosis contributes to modification of vascular wall structure, and occurs with spatio-temporal diversity within vasculature during the development and progression of hypertension (69, 130). Enhanced apoptosis has been found in the vasculature of SHR (166, 211), DOCA-salt rats (178) and Ang II-infused rats (38). Additionally, it was found that VSMCs isolated from SHRSP are more susceptible to apoptotic stimuli (37). Diverse mechanisms are involved in apoptosis in hypertension: activation of Ang II type 2 receptor (226), ETB receptor, L-type Ca2+ channel (196), and PPAR-α have been suggested to be associated with enhanced apoptosis. ROS are known to regulate such apoptotic pathways (79, 83, 108–110).

Recently, oxidative stress was demonstrated to be involved in rarefaction via promotion of endothelial apoptosis (91). Rarefaction, defined as a reduced spatial density of microvascular networks (8, 47), contributes to elevated peripheral resistance in hypertension. It has been observed in hypertensive animal models like SHR (91) and glucocorticoid hypertensive rats (212), as well as in human essential hypertension (8, 28, 177). Rarefaction has been reported in borderline essential hypertension and young adults with a predisposition to high blood pressure, as well as in established hypertension, suggesting that it may be both a cause and a consequence of hypertension (7, 8, 144). Accumulating evidence suggests that abnormal apoptosis of endothelial cells causes rarefaction (166, 212). In a recent study, chronic treatment with the superoxide scavengers tempol or tiron resulted in reduction of endothelial cell apoptosis and improved the loss of microvessels and oxidative stress in SHR (91).

Perspective

Recent advances in redox signaling provide insight into the role of ROS in the physiological and pathological processes of the vasculature related with hypertension. At the same time, however, they raise even more questions that need to be investigated. There are a few points to be underscored regarding treatment for hypertension. Basically, ROS act as signaling molecules that are associated with various physiological processes indispensable for normal function of blood vessels. Improper regulation of ROS compromise redox signaling, which is assumed to induce pathologic conditions such as hypertension. Hence, unilateral and nonspecific scavenging of ROS may not be efficient or adequate to improve impaired redox signaling. This is further supported by the complexity and diversity of ROS generating systems and antioxidant systems in the vasculature. Blood vessels are composed of different types of tissues interacting with each other–endothelium, SMCs, adventitial cells, and extracellular matrix, all of which have distinct sources of ROS and antioxidants. Moreover, the structure and composition of blood vessels are variable depending on the vascular bed. Additionally, the spatial complexity of redox signaling is complicated by subcellular compartmentalization of ROS generating enzymes and antioxidants. For example, NADPH oxidases are localized within cells depending on their subtypes, and different types of SOD, thioredoxins and peroxiredoxins are localized in distinct regions such as cytosol, mitochondria, endoplasmic reticulum, or extracellular space, suggesting that each redox component has distinct roles determined by their subcellular location, in addition to their specific chemical features. Each ROS has different physicochemical properties (e.g., redox potential, half-life, diffusion capability) and has distinct physiological roles. They are subject to metabolism, so they can convert into other species, which makes their specific role more complicated. In addition to the spatial complexity of redox systems, the temporal aspect of redox signaling is also important in the pathogenesis of hypertension. The contribution of specific ROS and cellular mechanisms may be variable depending upon the stages of hypertension, because it is unlikely that all the redox systems are involved in pathogenesis at the same time throughout the whole period of pathogenesis. The complexity of redox systems makes it clear that proper modulation of redox signaling for treatment of hypertension may not be achieved by administration of antioxidants, which have limited accessibility to target molecules and nonspecific modes of action. This is supported by the disparity between the effectiveness of antioxidant treatment in simple experimental systems in vitro, at the cellular or tissue level, and their relatively low efficiency in clinical trials. Current studies with improved forms of ROS scavenging enzymes, specific inhibitors for different ROS generating enzymes, and redox signaling pathway blocking agents allow subtle modulation of redox signaling and may overcome the redundancy of general antioxidant treatments. Thus, the spatial and temporal aspects of redox signaling in the vasculature are of much importance to understand the etiological role of ROS and to develop better strategies to treat hypertension.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants HL38206, HL58000, HL058863, and HL075209.

Abbreviations

Ang II, angiotensin II; BH4, tetrahydrobiopterin; DMNQ, 2,3-dimethoxy-1,4-naphthoquinone; DOCA-salt, deoxycorticosterone acetate-salt; ECE-1, endothelin-converting enzyme-1; ECM, extracellular matrix; EC-SOD, extracellular SOD; EDHF, endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factor; EGF, epidermal growth factor; eNOS, endothelial nitric oxide synthase; ET, endothelin; GSH, glutathione; ILK, integrin-linked kinase; IP3, inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate; IP3R, inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor; MAPKs, mitogen activated protein kinases; MLC, myosin light chain; MLCK, myosin light chain kinase; MMPs, matrix metalloproteinases; NAC, N-acetylcysteine; Nox, NADPH oxidases; PDI, protein disulfide isomerase; PMCA, plasma membrane Ca2+-ATPase; ROS, reactive oxygen species; SERCA, sarco/endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase; SOD, superoxide dismutase; SHR, spontaneously hypertensive rat; SHRSP, stroke prone spontaneously hypertensive rat; SMCs, smooth muscle cells; TBARS, thiobarbituric acid reactive species; VSMCs, vascular smooth muscle cells; XDH, xanthine dehydrogenase; XO, xanthine oxidase; ZIP kinase, zipper-interacting-like kinase.

References

- 1.Abdel-Sayed S. Nussberger J. Aubert JF. Gohlke P. Brunner HR. Brakch N. Measurement of plasma endothelin-1 in experimental hypertension and in healthy subjects. Am J Hypertens. 2003;16:515–521. doi: 10.1016/s0895-7061(03)00903-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abdilla N. Tormo MC. Fabia MJ. Chaves FJ. Saez G. Redon J. Impact of the components of metabolic syndrome on oxidative stress and enzymatic antioxidant activity in essential hypertension. J Hum Hypertens. 2007;21:68–75. doi: 10.1038/sj.jhh.1002105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alexander BT. Cockrell KL. Rinewalt AN. Herrington JN. Granger JP. Enhanced renal expression of preproendothelin mRNA during chronic angiotensin II hypertension. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2001;280:R1388–1392. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.2001.280.5.R1388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Allcock GH. Venema RC. Pollock DM. ETA receptor blockade attenuates the hypertension but not renal dysfunction in DOCA-salt rats. Am J Physiol. 1998;275:R245–252. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1998.275.1.R245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alvarez B. Demicheli V. Duran R. Trujillo M. Cervenansky C. Freeman BA. Radi R. Inactivation of human Cu,Zn superoxide dismutase by peroxynitrite and formation of histidinyl radical. Free Radic Biol Med. 2004;37:813–822. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2004.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Amberg GC. Bonev AD. Rossow CF. Nelson MT. Santana LF. Modulation of the molecular composition of large conductance, Ca(2+) activated K(+) channels in vascular smooth muscle during hypertension. J Clin Invest. 2003;112:717–724. doi: 10.1172/JCI18684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Antonios TF. Singer DR. Markandu ND. Mortimer PS. MacGregor GA. Rarefaction of skin capillaries in borderline essential hypertension suggests an early structural abnormality. Hypertension. 1999;34:655–658. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.34.4.655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Antonios TF. Singer DR. Markandu ND. Mortimer PS. MacGregor GA. Structural skin capillary rarefaction in essential hypertension. Hypertension. 1999;33:998–1001. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.33.4.998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aon MA. Cortassa S. O'Rourke B. Percolation and criticality in a mitochondrial network. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:4447–4452. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307156101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ardanaz N. Pagano PJ. Hydrogen peroxide as a paracrine vascular mediator: regulation and signaling leading to dysfunction. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2006;231:237–251. doi: 10.1177/153537020623100302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ballinger SW. Patterson C. Knight–Lozano CA. Burow DL. Conklin CA. Hu Z. Reuf J. Horaist C. Lebovitz R. Hunter GC. McIntyre K. Runge MS. Mitochondrial integrity and function in atherogenesis. Circulation. 2002;106:544–549. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000023921.93743.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Banday AA. Muhammad AB. Fazili FR. Lokhandwala M. Mechanisms of oxidative stress-induced increase in salt sensitivity and development of hypertension in Sprague-Dawley rats. Hypertension. 2007;49:664–671. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000255233.56410.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Barlow RS. El–Mowafy AM. White RE. H(2)O(2) opens BK(Ca) channels via the PLA(2)-arachidonic acid signaling cascade in coronary artery smooth muscle. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2000;279:H475–483. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2000.279.2.H475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Berry CE. Hare JM. Xanthine oxidoreductase and cardiovascular disease: molecular mechanisms and pathophysiological implications. J Physiol. 2004;555:589–606. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.055913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Beswick RA. Dorrance AM. Leite R. Webb RC. NADH/NADPH oxidase and enhanced superoxide production in the mineralocorticoid hypertensive rat. Hypertension. 2001;38:1107–1111. doi: 10.1161/hy1101.093423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brakemeier S. Eichler I. Knorr A. Fassheber T. Kohler R. Hoyer J. Modulation of Ca2+-activated K+ channel in renal artery endothelium in situ by nitric oxide and reactive oxygen species. Kidney Int. 2003;64:199–207. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2003.00051.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bratz IN. Falcon R. Partridge LD. Kanagy NL. Vascular smooth muscle cell membrane depolarization after NOS inhibition hypertension. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2002;282:H1648–1655. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00824.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Browatzki M. Larsen D. Pfeiffer CA. Gehrke SG. Schmidt J. Kranzhofer A. Katus HA. Kranzhofer R. Angiotensin II stimulates matrix metalloproteinase secretion in human vascular smooth muscle cells via nuclear factor-kappaB and activator protein 1 in a redox-sensitive manner. J Vasc Res. 2005;42:415–423. doi: 10.1159/000087451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Burke TM. Wolin MS. Hydrogen peroxide elicits pulmonary arterial relaxation and guanylate cyclase activation. Am J Physiol. 1987;252:H721–732. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1987.252.4.H721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Callera GE. Tostes RC. Yogi A. Montezano AC. Touyz RM. Endothelin-1-induced oxidative stress in DOCA-salt hypertension involves NADPH-oxidase-independent mechanisms. Clin Sci (Lond) 2006;110:243–253. doi: 10.1042/CS20050307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Callera GE. Touyz RM. Teixeira SA. Muscara MN. Carvalho MH. Fortes ZB. Nigro D. Schiffrin EL. Tostes RC. ETA receptor blockade decreases vascular superoxide generation in DOCA-salt hypertension. Hypertension. 2003;42:811–817. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000088363.65943.6C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cannon PJ. Stason WB. Demartini FE. Sommers SC. Laragh JH. Hyperuricemia in primary and renal hypertension. N Engl J Med. 1966;275:457–464. doi: 10.1056/NEJM196609012750902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cardillo C. Kilcoyne CM. Cannon RO., 3rd Quyyumi AA. Panza JA. Xanthine oxidase inhibition with oxypurinol improves endothelial vasodilator function in hypercholesterolemic but not in hypertensive patients. Hypertension. 1997;30:57–63. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.30.1.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ceriello A. Giugliano D. Quatraro A. Lefebvre PJ. Antioxidants show an anti-hypertensive effect in diabetic and hypertensive subjects. Clin Sci (Lond) 1991;81:739–742. doi: 10.1042/cs0810739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chabrashvili T. Tojo A. Onozato ML. Kitiyakara C. Quinn MT. Fujita T. Welch WJ. Wilcox CS. Expression and cellular localization of classic NADPH oxidase subunits in the spontaneously hypertensive rat kidney. Hypertension. 2002;39:269–274. doi: 10.1161/hy0202.103264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chalupsky K. Cai H. Endothelial dihydrofolate reductase: critical for nitric oxide bioavailability and role in angiotensin II uncoupling of endothelial nitric oxide synthase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:9056–9061. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409594102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen X. Touyz RM. Park JB. Schiffrin EL. Antioxidant effects of vitamins C and E are associated with altered activation of vascular NADPH oxidase and superoxide dismutase in stroke-prone SHR. Hypertension. 2001;38:606–611. doi: 10.1161/hy09t1.094005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ciuffetti G. Schillaci G. Innocente S. Lombardini R. Pasqualini L. Notaristefano S. Mannarino E. Capillary rarefaction and abnormal cardiovascular reactivity in hypertension. J Hypertens. 2003;21:2297–2303. doi: 10.1097/00004872-200312000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Clempus RE. Sorescu D. Dikalova AE. Pounkova L. Jo P. Sorescu GP. Schmidt HH. Lassegue B. Griendling KK. Nox4 is required for maintenance of the differentiated vascular smooth muscle cell phenotype. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2007;27:42–48. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000251500.94478.18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Colavitti R. Finkel T. Reactive oxygen species as mediators of cellular senescence. IUBMB Life. 2005;57:277–281. doi: 10.1080/15216540500091890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Contard F. Sabri A. Glukhova M. Sartore S. Marotte F. Pomies JP. Schiavi P. Guez D. Samuel JL. Rappaport L. Arterial smooth muscle cell phenotype in stroke-prone spontaneously hypertensive rats. Hypertension. 1993;22:665–676. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.22.5.665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cosentino F. Luscher TF. Tetrahydrobiopterin and endothelial function. Eur Heart J. 1998;19(Suppl G):G3–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cox RH. Lozinskaya I. Matsuda K. Dietz NJ. Ramipril treatment alters Ca(2+) and K(+) channels in small mesenteric arteries from Wistar–Kyoto and spontaneously hypertensive rats. Am J Hypertens. 2002;15:879–890. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cracowski JL. Baguet JP. Ormezzano O. Bessard J. Stanke–Labesque F. Bessard G. Mallion JM. Lipid peroxidation is not increased in patients with untreated mild-to-moderate hypertension. Hypertension. 2003;41:286–288. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.0000050963.16405.e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.d'Uscio LV. Moreau P. Shaw S. Takase H. Barton M. Luscher TF. Effects of chronic ETA-receptor blockade in angiotensin II-induced hypertension. Hypertension. 1997;29:435–441. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.29.1.435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Derosa G. D'Angelo A. Ciccarelli L. Piccinni MN. Pricolo F. Salvadeo S. Montagna L. Gravina A. Ferrari I. Galli S. Paniga S. Tinelli C. Cicero AF. Matrix metalloproteinase-2, −9, and tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase-1 in patients with hypertension. Endothelium. 2006;13:227–231. doi: 10.1080/10623320600780942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Devlin AM. Clark JS. Reid JL. Dominiczak AF. DNA synthesis and apoptosis in smooth muscle cells from a model of genetic hypertension. Hypertension. 2000;36:110–115. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.36.1.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Diep QN. Li JS. Schiffrin EL. In vivo study of AT(1) and AT(2) angiotensin receptors in apoptosis in rat blood vessels. Hypertension. 1999;34:617–624. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.34.4.617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Diep QN. Touyz RM. Schiffrin EL. Docosahexaenoic acid, a peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-alpha ligand, induces apoptosis in vascular smooth muscle cells by stimulation of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase. Hypertension. 2000;36:851–855. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.36.5.851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dikalova A. Clempus R. Lassegue B. Cheng G. McCoy J. Dikalov S. San Martin A. Lyle A. Weber DS. Weiss D. Taylor WR. Schmidt HH. Owens GK. Lambeth JD. Griendling KK. Nox1 overexpression potentiates angiotensin II-induced hypertension and vascular smooth muscle hypertrophy in transgenic mice. Circulation. 2005;112:2668–2676. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.538934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dobrian AD. Schriver SD. Prewitt RL. Role of angiotensin II and free radicals in blood pressure regulation in a rat model of renal hypertension. Hypertension. 2001;38:361–366. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.38.3.361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Duprez DA. Role of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system in vascular remodeling and inflammation: a clinical review. J Hypertens. 2006;24:983–991. doi: 10.1097/01.hjh.0000226182.60321.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Elmarakby AA. Loomis ED. Pollock JS. Pollock DM. NADPH oxidase inhibition attenuates oxidative stress but not hypertension produced by chronic ET-1. Hypertension. 2005;45:283–287. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000153051.56460.6a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ergul A. Hypertension in black patients: an emerging role of the endothelin system in salt-sensitive hypertension. Hypertension. 2000;36:62–67. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.36.1.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Escalante BA. McGiff JC. Oyekan AO. Role of cytochrome P-450 arachidonate metabolites in endothelin signaling in rat proximal tubule. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2002;282:F144–150. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.0064.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Favero TG. Zable AC. Abramson JJ. Hydrogen peroxide stimulates the Ca2+ release channel from skeletal muscle sarcoplasmic reticulum. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:25557–25563. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.43.25557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Feihl F. Liaudet L. Waeber B. Levy BI. Hypertension: a disease of the microcirculation? Hypertension. 2006;48:1012–1017. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000249510.20326.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Feletou M. Vanhoutte PM. Endothelial dysfunction: a multifaceted disorder (The Wiggers Award Lecture) Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2006;291:H985–1002. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00292.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Forstermann U. Munzel T. Endothelial nitric oxide synthase in vascular disease: from marvel to menace. Circulation. 2006;113:1708–1714. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.602532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fortuno A. Olivan S. Beloqui O. San Jose G. Moreno MU. Diez J. Zalba G. Association of increased phagocytic NADPH oxidase-dependent superoxide production with diminished nitric oxide generation in essential hypertension. J Hypertens. 2004;22:2169–2175. doi: 10.1097/00004872-200411000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fujimoto S. Asano T. Sakai M. Sakurai K. Takagi D. Yoshimoto N. Itoh T. Mechanisms of hydrogen peroxide-induced relaxation in rabbit mesenteric small artery. Eur J Pharmacol. 2001;412:291–300. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(00)00940-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fukui T. Ishizaka N. Rajagopalan S. Laursen JB. Capers Qt. Taylor WR. Harrison DG. de Leon H. Wilcox JN. Griendling KK. p22phox mRNA expression and NADPH oxidase activity are increased in aortas from hypertensive rats. Circ Res. 1997;80:45–51. doi: 10.1161/01.res.80.1.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Funder JW. Cardiovascular endocrinology: into the new millennium. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2001;12:283–285. doi: 10.1016/s1043-2760(01)00443-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Galley HF. Thornton J. Howdle PD. Walker BE. Webster NR. Combination oral antioxidant supplementation reduces blood pressure. Clin Sci (Lond) 1997;92:361–365. doi: 10.1042/cs0920361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gao YJ. Hirota S. Zhang DW. Janssen LJ. Lee RM. Mechanisms of hydrogen-peroxide-induced biphasic response in rat mesenteric artery. Br J Pharmacol. 2003;138:1085–1092. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gao YJ. Zhang Y. Hirota S. Janssen LJ. Lee RM. Vascular relaxation response to hydrogen peroxide is impaired in hypertension. Br J Pharmacol. 2004;142:143–149. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gerthoffer WT. Mechanisms of vascular smooth muscle cell migration. Circ Res. 2007;100:607–621. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000258492.96097.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Giannelli G. Iannone F. Marinosci F. Lapadula G. Antonaci S. The effect of bosentan on matrix metalloproteinase-9 levels in patients with systemic sclerosis-induced pulmonary hypertension. Curr Med Res Opin. 2005;21:327–332. doi: 10.1185/030079905X30680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Goto K. Rummery NM. Grayson TH. Hill CE. Attenuation of conducted vasodilatation in rat mesenteric arteries during hypertension: role of inwardly rectifying potassium channels. J Physiol. 2004;561:215–231. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.070458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Greene EL. Lu G. Zhang D. Egan BM. Signaling events mediating the additive effects of oleic acid and angiotensin II on vascular smooth muscle cell migration. Hypertension. 2001;37:308–312. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.37.2.308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Griendling KK. Sorescu D. Lassegue B. Ushio–Fukai M. Modulation of protein kinase activity and gene expression by reactive oxygen species and their role in vascular physiology and pathophysiology. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2000;20:2175–2183. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.20.10.2175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Grote K. Flach I. Luchtefeld M. Akin E. Holland SM. Drexler H. Schieffer B. Mechanical stretch enhances mRNA expression and proenzyme release of matrix metalloproteinase-2 (MMP-2) via NAD(P)H oxidase-derived reactive oxygen species. Circ Res. 2003;92:e80–86. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000077044.60138.7C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Grover AK. Samson SE. Effect of superoxide radical on Ca2+ pumps of coronary artery. Am J Physiol. 1988;255:C297–303. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1988.255.3.C297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Grover AK. Samson SE. Fomin VP. Peroxide inactivates calcium pumps in pig coronary artery. Am J Physiol. 1992;263:H537–543. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1992.263.2.H537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Grover AK. Samson SE. Robinson S. Kwan CY. Effects of peroxynitrite on sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ pump in pig coronary artery smooth muscle. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2003;284:C294–301. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00297.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Gurjar MV. DeLeon J. Sharma RV. Bhalla RC. Mechanism of inhibition of matrix metalloproteinase-9 induction by NO in vascular smooth muscle cells. J Appl Physiol. 2001;91:1380–1386. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2001.91.3.1380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Gutterman DD. Miura H. Liu Y. Redox modulation of vascular tone: focus of potassium channel mechanisms of dilation. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2005;25:671–678. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000158497.09626.3b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hadrava V. Tremblay J. Hamet P. Abnormalities in growth characteristics of aortic smooth muscle cells in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Hypertension. 1989;13:589–597. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.13.6.589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Hamet P. deBlois D. Dam TV. Richard L. Teiger E. Tea BS. Orlov SN. Tremblay J. Apoptosis and vascular wall remodeling in hypertension. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 1996;74:850–861. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Harris CM. Sanders SA. Massey V. Role of the flavin midpoint potential and NAD binding in determining NAD versus oxygen reactivity of xanthine oxidoreductase. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:4561–4569. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.8.4561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Hassanain HH. Gregg D. Marcelo ML. Zweier JL. Souza HP. Selvakumar B. Ma Q. Moustafa–Bayoumi M. Binkley PF. Flavahan NA. Morris M. Dong C. Goldschmidt–Clermont PJ. Hypertension caused by transgenic overexpression of Rac1. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2007;9:91–100. doi: 10.1089/ars.2007.9.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Heerkens EH. Izzard AS. Heagerty AM. Integrins, vascular remodeling, and hypertension. Hypertension. 2007;49:1–4. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000252753.63224.3b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Heitzer T. Wenzel U. Hink U. Krollner D. Skatchkov M. Stahl RA. MacHarzina R. Brasen JH. Meinertz T. Munzel T. Increased NAD(P)H oxidase-mediated superoxide production in renovascular hypertension: evidence for an involvement of protein kinase C. Kidney Int. 1999;55:252–260. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.1999.00229.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Higashi Y. Sasaki S. Nakagawa K. Fukuda Y. Matsuura H. Oshima T. Chayama K. Tetrahydrobiopterin enhances forearm vascular response to acetylcholine in both normotensive and hypertensive individuals. Am J Hypertens. 2002;15:326–332. doi: 10.1016/s0895-7061(01)02317-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Higashi Y. Sasaki S. Nakagawa K. Matsuura H. Oshima T. Chayama K. Endothelial function and oxidative stress in renovascular hypertension. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:1954–1962. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa013591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Hilenski LL. Clempus RE. Quinn MT. Lambeth JD. Griendling KK. Distinct subcellular localizations of Nox1 and Nox4 in vascular smooth muscle cells. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2004;24:677–683. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000112024.13727.2c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Hu WY. Fukuda N. Kanmatsuse K. Growth characteristics, angiotensin II generation, and microarray-determined gene expression in vascular smooth muscle cells from young spontaneously hypertensive rats. J Hypertens. 2002;20:1323–1333. doi: 10.1097/00004872-200207000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Iida Y. Katusic ZS. Mechanisms of cerebral arterial relaxations to hydrogen peroxide. Stroke. 2000;31:2224–2230. doi: 10.1161/01.str.31.9.2224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Irani K. Oxidant signaling in vascular cell growth, death, and survival : a review of the roles of reactive oxygen species in smooth muscle and endothelial cell mitogenic and apoptotic signaling. Circ Res. 2000;87:179–183. doi: 10.1161/01.res.87.3.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Janiszewski M. Lopes LR. Carmo AO. Pedro MA. Brandes RP. Santos CX. Laurindo FR. Regulation of NAD(P)H oxidase by associated protein disulfide isomerase in vascular smooth muscle cells. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:40813–40819. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M509255200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Jin L. Ying Z. Hilgers RH. Yin J. Zhao X. Imig JD. Webb RC. Increased RhoA/Rho-kinase signaling mediates spontaneous tone in aorta from angiotensin II-induced hypertensive rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2006;318:288–295. doi: 10.1124/jpet.105.100735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Jin L. Ying Z. Webb RC. Activation of Rho/Rho kinase signaling pathway by reactive oxygen species in rat aorta. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2004;287:H1495–1500. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01006.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Johnson TM. Yu ZX. Ferrans VJ. Lowenstein RA. Finkel T. Reactive oxygen species are downstream mediators of p53-dependent apoptosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:11848–11852. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.21.11848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Kaehler J. Sill B. Koester R. Mittmann C. Orzechowski HD. Muenzel T. Meinertz T. Endothelin-1 mRNA and protein in vascular wall cells is increased by reactive oxygen species. Clin Sci (Lond) 2002;103(Suppl 48):176S–178S. doi: 10.1042/CS103S176S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Kaplan P. Babusikova E. Lehotsky J. Dobrota D. Free radical-induced protein modification and inhibition of Ca2+-ATPase of cardiac sarcoplasmic reticulum. Mol Cell Biochem. 2003;248:4147. doi: 10.1023/a:1024145212616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Kappert K. Sparwel J. Sandin A. Seiler A. Siebolts U. Leppanen O. Rosenkranz S. Ostman A. Antioxidants relieve phosphatase inhibition and reduce PDGF signaling in cultured VSMCs and in restenosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2006;26:26442651. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000246777.30819.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Katusic ZS. Vanhoutte PM. Superoxide anion is an endothelium-derived contracting factor. Am J Physiol. 1989;257:H3337. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1989.257.1.H33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Kerr S. Brosnan MJ. McIntyre M. Reid JL. Dominiczak AF. Hamilton CA. Superoxide anion production is increased in a model of genetic hypertension: role of the endothelium. Hypertension. 1999;33:1353–1358. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.33.6.1353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Kim J. Min G. Bae YS. Min DS. Phospholipase D is involved in oxidative stress-induced migration of vascular smooth muscle cells via tyrosine phosphorylation and protein kinase C. Exp Mol Med. 2004;36:103–109. doi: 10.1038/emm.2004.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Kitamoto S. Egashira K. Kataoka C. Usui M. Koyanagi M. Takemoto M. Takeshita A. Chronic inhibition of nitric oxide synthesis in rats increases aortic superoxide anion production via the action of angiotensin II. J Hypertens. 2000;18:1795–1800. doi: 10.1097/00004872-200018120-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Kobayashi N. DeLano FA. Schmid–Schonbein GW. Oxidative stress promotes endothelial cell apoptosis and loss of microvessels in the spontaneously hypertensive rats. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2005;25:2114–2121. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000178993.13222.f2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Korsgaard N. Aalkjaer C. Heagerty AM. Izzard AS. Mulvany MJ. Histology of subcutaneous small arteries from patients with essential hypertension. Hypertension. 1993;22:523–526. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.22.4.523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Kourie JI. Interaction of reactive oxygen species with ion transport mechanisms. Am J Physiol. 1998;275:C1–24. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1998.275.1.C1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Kuzkaya N. Weissmann N. Harrison DG. Dikalov S. Interactions of peroxynitrite, tetrahydrobiopterin, ascorbic acid, and thiols: implications for uncoupling endothelial nitric-oxide synthase. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:22546–22554. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M302227200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Laakso J. Mervaala E. Himberg JJ. Teravainen TL. Karppanen H. Vapaatalo H. Lapatto R. Increased kidney xanthine oxidoreductase activity in salt-induced experimental hypertension. Hypertension. 1998;32:902–906. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.32.5.902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Lacy F. O'Connor DT. Schmid-Schonbein GW. Plasma hydrogen peroxide production in hypertensives and normotensive subjects at genetic risk of hypertension. J Hypertens. 1998;16:291–303. doi: 10.1097/00004872-199816030-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Landmesser U. Cai H. Dikalov S. McCann L. Hwang J. Jo H. Holland SM. Harrison DG. Role of p47(phox) in vascular oxidative stress and hypertension caused by angiotensin II. Hypertension. 2002;40:511–515. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.0000032100.23772.98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Landmesser U. Dikalov S. Price SR. McCann L. Fukai T. Holland SM. Mitch WE. Harrison DG. Oxidation of tetrahydrobiopterin leads to uncoupling of endothelial cell nitric oxide synthase in hypertension. J Clin Invest. 2003;111:1201–1209. doi: 10.1172/JCI14172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Landmesser U. Harrison DG. Oxidative stress and vascular damage in hypertension. Coron Artery Dis. 2001;12:455–461. doi: 10.1097/00019501-200109000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Landmesser U. Spiekermann S. Preuss C. Sorrentino S. Fischer D. Manes C. Mueller M. Drexler H. Angiotensin II induces endothelial xanthine oxidase activation: role for endothelial dysfunction in patients with coronary disease. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2007;27:943–948. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000258415.32883.bf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Lassegue B. Clempus RE. Vascular NAD(P)H oxidases: specific features, expression, and regulation. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2003;285:R277–297. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00758.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Lassegue B. Sorescu D. Szocs K. Yin Q. Akers M. Zhang Y. Grant SL. Lambeth JD. Griendling KK. Novel gp91(phox) homologues in vascular smooth muscle cells : nox1 mediates angiotensin II-induced superoxide formation and redox-sensitive signaling pathways. Circ Res. 2001;88:888–894. doi: 10.1161/hh0901.090299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Laursen JB. Somers M. Kurz S. McCann L. Warnholtz A. Freeman BA. Tarpey M. Fukai T. Harrison DG. Endothelial regulation of vasomotion in apoE-deficient mice: implications for interactions between peroxynitrite and tetrahydrobiopterin. Circulation. 2001;103:1282–1288. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.103.9.1282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Laviades C. Varo N. Fernandez J. Mayor G. Gil MJ. Monreal I. Diez J. Abnormalities of the extracellular degradation of collagen type I in essential hypertension. Circulation. 1998;98:535–540. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.98.6.535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Lee VM. Quinn PA. Jennings SC. Ng LL. Neutrophil activation and production of reactive oxygen species in pre-eclampsia. J Hypertens. 2003;21:395–402. doi: 10.1097/00004872-200302000-00032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Li JM. Wheatcroft S. Fan LM. Kearney MT. Shah AM. Opposing roles of p47phox in basal versus angiotensin II-stimulated alterations in vascular O2- production, vascular tone, and mitogen-activated protein kinase activation. Circulation. 2004;109:1307–1313. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000118463.23388.B9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Li L. Fink GD. Watts SW. Northcott CA. Galligan JJ. Pagano PJ. Chen AF. Endothelin-1 increases vascular superoxide via endothelin(A)-NADPH oxidase pathway in low-renin hypertension. Circulation. 2003;107:1053–1058. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000051459.74466.46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Li PF. Dietz R. von Harsdorf R. Differential effect of hydrogen peroxide and superoxide anion on apoptosis and proliferation of vascular smooth muscle cells. Circulation. 1997;96:3602–3609. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.96.10.3602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Li PF. Dietz R. von Harsdorf R. Reactive oxygen species induce apoptosis of vascular smooth muscle cell. FEBS Lett. 1997;404:249–252. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)00093-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Li PF. Maasch C. Haller H. Dietz R. von Harsdorf R. Requirement for protein kinase C in reactive oxygen species-induced apoptosis of vascular smooth muscle cells. Circulation. 1999;100:967–973. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.100.9.967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Li–Saw–Hee FL. Edmunds E. Blann AD. Beevers DG. Lip GY. Matrix metalloproteinase-9 and tissue inhibitor metalloproteinase-1 levels in essential hypertension. Relationship to left ventricular mass and anti-hypertensive therapy. Int J Cardiol. 2000;75:43–47. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5273(00)00274-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Lip GY. Edmunds E. Nuttall SL. Landray MJ. Blann AD. Beevers DG. Oxidative stress in malignant and non-malignant phase hypertension. J Hum Hypertens. 2002;16:333–336. doi: 10.1038/sj.jhh.1001386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Liu W. Rosenberg GA. Shi H. Furuichi T. Timmins GS. Cunningham LA. Liu KJ. Xanthine oxidase activates pro-matrix metalloproteinase-2 in cultured rat vascular smooth muscle cells through non-free radical mechanisms. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2004;426:11–17. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2004.03.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Liu Y. Terata K. Chai Q. Li H. Kleinman LH. Gutterman DD. Peroxynitrite inhibits Ca2+-activated K+ channel activity in smooth muscle of human coronary arterioles. Circ Res. 2002;91:1070–1076. doi: 10.1161/01.res.0000046003.14031.98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Lo IC. Shih JM. Jiang MJ. Reactive oxygen species and ERK 1/2 mediate monocyte chemotactic protein-1-stimulated smooth muscle cell migration. J Biomed Sci. 2005;12:377–388. doi: 10.1007/s11373-005-1703-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Loirand G. Rolli-Derkinderen M. Pacaud P. RhoA and resistance artery remodeling. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2005;288:H1051–1056. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00710.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Loomis ED. Sullivan JC. Osmond DA. Pollock DM. Pollock JS. Endothelin mediates superoxide production and vasoconstriction through activation of NADPH oxidase and uncoupled nitricoxide synthase in the rat aorta. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2005;315:1058–1064. doi: 10.1124/jpet.105.091728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Lucchesi PA. Belmadani S. Matrougui K. Hydrogen peroxide acts as both vasodilator and vasoconstrictor in the control of perfused mouse mesenteric resistance arteries. J Hypertens. 2005;23:571–579. doi: 10.1097/01.hjh.0000160214.40855.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Mahadevan VS. Campbell M. McKeown PP. Bayraktutan U. Internal mammary artery smooth muscle cells resist migration and possess high antioxidant capacity. Cardiovasc Res. 2006;72:60–68. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2006.06.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Martens JR. Gelband CH. Alterations in rat interlobar artery membrane potential and K+ channels in genetic and nongenetic hypertension. Circ Res. 1996;79:295–301. doi: 10.1161/01.res.79.2.295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Martens JR. Gelband CH. Ion channels in vascular smooth muscle: alterations in essential hypertension. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1998;218:192–203. doi: 10.3181/00379727-218-44286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Martinez ML. Lopes LF. Coelho EB. Nobre F. Rocha JB. Gerlach RF. Tanus–Santos JE. Lercanidipine reduces matrix metalloproteinase-9 activity in patients with hypertension. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2006;47:117–122. doi: 10.1097/01.fjc.0000196241.96759.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]