Abstract

Abnormal T cell responses to commensal bacteria are involved in the pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). MyD88 is an essential signal transducer for TLRs in response to the microflora. We hypothesized that TLR signaling via MyD88 was important for effector T cell responses in the intestine. TLR expression on murine T cells was examined by flow cytometry. CD4+CD45Rbhigh T cells and/or CD4+CD45RblowCD25+ regulatory T cells (Tregs) were isolated and adoptively transferred to RAG1−/− mice. Colitis was assessed by changes in body weight and histology score. Cytokine production was assessed by ELISA. In vitro proliferation of T cells was assessed by [3H]thymidine assay. In vivo proliferation of T cells was assessed by BrdU and CFSE labeling. CD4+CD45Rbhigh T cells expressed TLR2, TLR4, TLR9, and TLR3 and TLR ligands could act as co-stimulatory molecules. MyD88−/− CD4+ T cells showed decreased proliferation compared with WT CD4+ T cells both in vivo and in vitro. CD4+CD45Rbhigh T cells from MyD88−/− mice did not induce wasting disease when transferred into RAG1−/− recipients. Lamina propria CD4+ T cell expression of IL-2 and IL-17 and colonic expression of IL-6 and IL-23 were significantly lower in mice receiving MyD88−/− cells than mice receiving WT cells. In vitro, MyD88−/− T cells were blunted in their ability to secrete IL-17 but not IFN-γ. Absence of MyD88 in CD4+CD45Rbhigh cells results in defective T cell function, especially Th17 differentiation. These results suggest a role for TLR signaling by T cells in the development of IBD.

Keywords: T Cells, Cell Activation, Cell Differentiation, Inflammation, Signal Transduction

Introduction

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is characterized by chronic intestinal inflammation in the absence of a recognized bacterial pathogen. Advances in human genome research have revealed that several candidate genes in IBD are linked to innate immunity (1–6). On the other hand, abnormal T cell responses to luminal commensal bacteria are crucial to the pathogenesis of IBD (7–9). The link between genetic defects in innate immunity and sustained activation of T cells remains unclear.

Recognition of commensal bacteria largely depends on toll-like receptors (TLRs) in the intestinal mucosa (10). TLRs are pattern recognition receptors expressed by immune and non-immune cells in the intestinal mucosa that signal in response to pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) expressed by microbes (11). The main purpose of TLR signaling is to provide a rapid response against pathogens to protect the host. Eleven TLRs have been identified and individual or pairs of TLRs recognize distinct PAMPs. Most TLRs, with the exception of TLR3, signal via the adapter molecule MyD88 to the IL-1 receptor associated kinase (IRAK) and TRAF6 to transforming growth factor-beta-activated kinase 1 (TAK1), leading to the nuclear translocation of NF-κB and activation of mitogen activated protein (MAP) kinases (12). Previous studies have demonstrated that MyD88 deficient mice develop profound defects in antigen-specific T cell responses, suggesting that TLR signaling plays a role in the development of adaptive immune responses (13, 14), but the effect of MyD88 was thought to be mediated by antigen presenting cells (APCs).

Mucosal immune homeostasis requires a balanced interplay between effector T cells and regulatory T cells (Tregs). Naïve T cells differentiate into effector cells that are divided into three distinctive types, Th1, Th2, Th17 cells, depending on the type of cytokines secreted. The fate of T cell differentiation into Th1, Th2, or Th17 type T cells or Tregs is largely regulated by the interaction between naïve T cells and dendritic cells (DCs) (15). The recognition of PAMPs by TLRs on DCs promotes stimulation of antigen presentation, up-regulation of costimulatory molecules, and secretion of cytokines, which in turn leads to the induction of T cell differentiation, proliferation, and survival of antigen specific CD4+ T cells (11).

Although most TLR functions have been attributed to their role in DC activation, CD4+ T cells also express TLRs and may regulate functional responses of CD4+ T cells in an APC-independent manner (16–21). For example, TLR2 is a potent costimulatory receptor found on CD4+ T cells, which may increase proliferation and IFN-γ secretion following TCR stimulation (22, 23). TLR3 signals have been suggested to prolong CD4+ T cell survival (17). TLR5 and TLR7 have been shown to enhance TCR stimulation in memory CD4+ T cells (16). TLR4 signaling on T cells mediates adherence to fibronectin and expression of suppressor of cytokine signaling 3 (SOCS3) (24). TLR9 mediated CD4+ T cell activation has been shown to be MyD88 dependent (25). Recently, IRAK-4 the most proximal downstream signaling molecule after MyD88, has been shown to be essential in eliciting CD4+ T cell activation (26). Finally, TLRs modulate Treg proliferation and their ability to suppress T cell activation (27–29). These data suggest a significant role for MyD88 in CD4+ T cell activation.

Commensal bacteria are required to initiate chronic intestinal inflammation in most animal models of IBD (30). The CD4+CD45RBhigh cell adoptive transfer model of colitis is one of the animal models of IBD which most closely reflects human IBD with respect to gene expression profiles (31). In this model of colitis, CD4+CD45RBhigh T cells are activated in response to commensal bacteria to initiate chronic inflammation in the absence of T regulatory cells (Tregs) (32). This T cell population has also been suggested to be important in the pathogenesis of human IBD (33). Therefore, we hypothesized that TLR signaling via MyD88 is important for the development of colitis in the murine CD4+CD45Rbhigh T cell adoptive transfer model.

In the current study, we first determined the expression of TLRs on CD4+CD45Rbhigh T cells. The finding that CD4+CD45Rbhigh T cells express significant levels of TLRs, led us to test their role in the development of colitis. We examined the effects of MyD88 deficiency on CD4+ T cell activation in vivo and in vitro using MyD88 knockout (MyD88−/−) mice as donor mice. In the adoptive transfer model of colitis, CD4+CD45Rbhigh T cells from MyD88−/− mice did not induce wasting disease. MyD88−/− T cells also showed defective proliferation in vitro and in vivo. The secretion of IL-2 and IL-17 was significantly reduced in CD4+ T cells from mice receiving MyD88−/− T cells compared to mice receiving WT T cells. In vitro, TLR ligands could act as co-stimulatory molecules in the context of anti-CD3 stimulation. In addition, Tregs from MyD88−/− mice showed a decreased ability to suppress T cell proliferation in vivo and in vitro. These results suggest that MyD88 signaling by CD4+ T cells is required for expansion and differentiation in the intestinal compartment. Our results provide a link between an innate immune defect and the sustained activation of T cells in the pathogenesis of IBD.

Materials and Methods

Mouse transfer colitis

MyD88−/− mice were purchased from Oriental Bio Service, Inc. (Kyoto, Japan) and were backcrossed to C57Bl/6 mice over 10 times. C57Bl/6 mice and RAG1−/− mice (C57Bl/6 background) were obtained from the Jackson Laboratory (Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, Maine). Six to ten week old gender-matched mice were used in this study. Mice were kept in specific-pathogen free (SPF) conditions and fed by free access to a standard diet and water. All experiments were performed according to Mount Sinai School of Medicine animal experimental ethics committee guidelines.

Spleen and MLN were taken from WT (C57Bl/6) mice and MyD88−/− mice. Single cell suspensions from the spleen and MLN were prepared to isolate CD4+ T cells using MACS magnetic separation system (Miltenyi Biotec, Aburn, CA). Enriched CD4+ T cells were labeled with FITC-conjugated anti-CD45Rb (BD Biosciences, Bedford, MA), and allophycocyanin (APC)-conjugated CD25 (Biolegend, San Diego, CA). CD4+CD45Rbhigh and CD4+CD45Rblow CD25+ cell fractions were sorted with a FACS Vantage cell sorter (BD Biosciences, Bedford, MA). The purity of cell separation was over 98% as measured by flow cytometry. Sorted cells were resuspended in sterile PBS; 5 × 105 CD4+CD45Rbhigh cells were injected intraperitoneally into each RAG1−/− mouse. Additional mice were injected with WT CD4+CD45Rbhigh cells (5 × 105) and CD4+CD45Rblow CD25+ cells (5 × 105) isolated from either WT or MyD88−/− mice (34, 35).

Mice were monitored weekly for body weight, stools, and the gross appearance of wasting disease. Mice were euthanized nine weeks after T cell transfer. Cecum, and proximal and distal halves of the colon were removed and fixed in 10% buffered formalin, paraffin-embedded, sectioned and stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Histological assessment was performed by a pathologist blinded to the treatment. Histologic score was a combined score of crypt damage (0–4), acute inflammatory cell infiltrate (0–4), edema (0–4), erosion/ulceration (0–4), chronic inflammatory cell infiltrate (0–2), epithelial regeneration (0–3), and crypt distortion/branching (0–3).

Isolation of lamina propria (LP) cells

Colons were removed, washed in PBS with 5% penicillin/streptomycin, cut into small pieces, and incubated with Ca2+, Mg2+ free Hanks’ balanced salt solution containing 0.002 mol/L EDTA for 12 min with gentle agitation to remove epithelial cells. Tissue pieces were then incubated while shaking in complete medium containing 5% FCS, 0.02 mol/L HEPES, L-glutamine, 5% penicillin and streptomycin with 1mg/ml collagenase, 1.5 mg/ml dispase in RPMI at 37°C for 60 min. The supernatant was centrifuged and the pellet was washed two times with RPMI containing 5% penicillin/streptomycin. LP cells were isolated by lymphocyte separation medium (Mediatech, Inc., Herndon, VA) density gradient centrifugation (800g for 20 min) and collected at the interface. Dendritic cells (DCs) were isolated from LP cells by positive selection using the anti-CD11c MACS beads (Miltenyi Biotec, Aburn, CA). Using the DC isolation flow through, CD4+ cells were further isolated by negative selection with the CD4 MACS system (Miltenyi Biotec, Aburn, CA).

Real Time PCR

Total RNA was isolated from the colonic tissues using RNA Bee (Tel-Test, Inc., Friendwood, TX) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. A total of 1 µg RNA was used as the template for single strand cDNA synthesis utilizing the Transcriptor First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Roche, Indianapolis, IN) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Quantitative real-time PCR was performed for IL-23p19, IL-6 and β-actin. The primers and probes used in this study are as follows: (5’→3’ direction), for mouse IL-23p19: sense primer, C TGT GCC TAG GAG TAG CAG TC, anti-sense primer, A GTC TCT TCA TCC TCT TCT TCT CT, and probe, C TCA GTG CCA GCA GCT CTC TCG GA; mouse IL-6 primers and probe were designed by Applied Biosystems (Mn00446190_m1; Foster City, CA); for mouse β-actin: sense primer, ATG ACC CAG ATC ATG TTT G, anti-sense primer, TAC GAC CAG AGG CAT ACA, and probe, CGT AGC CAT CCA GGC TGT GC. All TaqMan probes and primers were designed using Beacon Designer 3.0 (Premier Biosoft International, Palo Alto, CA). The cDNA was amplified using TaqMan universal PCR Master Mix (Roche, Indianapolis, IN) on the ABI Prism 7900HT sequence detection system (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA), programmed for 95°C for 10 min, then 40 cycles of: 95 °C for 15 sec, 60 °C for 1 min. The amplification results were analyzed using SDS 2.2.1 software (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA), and the genes of interest were normalized to the corresponding β-actin results.

Western Blot Analysis

Whole cell lysates were prepared from lamina propria CD4+ T cells using a lysis buffer containing 50mM Tris HCl, 50mM NaF, 1% Triton ×100, 2mM EDTA, and 100mM NaCl, with a proteinase inhibitor cocktail (Calbiochem, San Diego, CA). Protein concentration was determined by the Bradford method using Bio-Rad Protein Assay Dye and SmartSpec™ 3000 (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA). 25 µg of the lysates were subjected to 10% SDS-PAGE and transferred to Immobilon-P membranes (Millipore Corporation, Bedford, MA). The membrane was blocked in 5% skim milk and was immunoblotted with the primary antibodies for 1hr, followed by HRP-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG, or Streptavidin-HRP (Zymed Laboratories, South San Francisco, CA) corresponding to the primary antibodies used. The membrane was exposed on an x-ray film using an enhanced chemiluminescent substrate SuperSignal West Pico Trial Kit (Pierce Biotechnology, Rockford, IL). Antibodies specific for phoshpo (Ser 727)-STAT3 and phospho (Tyr 705)-STAT3, and STAT3 were purchased from Cell Signaling (Danvers, MA).

Immunohistochemistry

Paraffin-embedded colon tissue samples (n=5 each for mice that received WT T cells or mice that received MyD88−/− T cells) were double stained with CD4 and phospho-STAT3. Antigen retrieval by microwave was performed after deparaffinization. After blocking the nonspecific binding with 5% skim milk, sections were incubated with rabbit anti-phospho (Ser 727)-STAT3 antibody (1:100, Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA) overnight at 4°C. After washing in PBS, sections were incubated with TRITC-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (1:200, Sigma, St. Louis, MO) for 1 hour at room temperature. Sections were then re-incubated with 5% skim milk and stained with FITC-conjugated anti-mouse CD4 antibody (1:100, PharMingen, BD Biosciences San Jose, CA) overnight at 4°C. Sections were mounted with SlowFade Gold antifade reagent with DAPI (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) after rinsing with PBS. Double stained tissue slides were examined using a Leica TCS-SP (UV) confocal microscope.

In vitro T cell differentiation

The method for in vitro T cell differentiation was adapted from previous studies (36, 37). Briefly, CD4+CD45Rbhigh T cells isolated from MyD88−/− or WT mice spleen were cultured in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% FCS, 5% Pen/Strep at 37°C in 5% CO2. Cells were primed for 5 days with plate-bound anti-CD3 (2 µg/mL; PharMingen, San Diego, CA), anti-CD28 (2 µg/mL; BD Pharmingen, San Diego, CA) and anti-IL-4 (4 µg/mL; 11B11 L, Santa Cruz Biotechnology). The following cytokines were added for five daysas indicated. For Th1 differentiation, IL-12 (4 ng/mL; PeproTech, Rocky Hill, NJ) was added. For Th17 differentiation, IL-6 (100 ng/mL; PeproTech, Rocky Hill, NJ) plus TGF-β (5 ng/ml; PeproTech, Rocky Hill, NJ), or IL-23 (10 ng/ml; R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) were added. Cells were then washed and stimulated for 24 hours with plate-bound anti-CD3 (1 ug/mL; BD Biosciences, Mountain View, CA) at a density of 1 × 106 cells/mL. Cell-free supernatants were analyzed simultaneously for IL-17 or IFN-γ production using specific ELISA kits (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN).

Enzyme linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)

To measure cytokine production, DCs and CD4+ T cells were isolated from the lamina propria. CD4+ T cells (1×105) were co-cultured with LP-DCs (5×103) isolated from the same mouse in RPMI supplemented with 10% FCS, 5% penicillin/streptomycin in 96 well anti-CD3 precoated (1µg/ml) flat bottom plates (BD Biosciences, Mountain View, CA) for 48 hours. IFN-γ, IL-2, IL-10, IL-17A concentrations in the supernatant were determined by ELISA (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Flow cytometry

CD4+CD45Rbhigh T cells were isolated from spleens. RAW 264.7 cells were used as a positive control for TLR staining. Spleen cells from knock-out mice (TLR4−/−, TLR2−/−, TLR3−/− and TLR9−/−) or isotype matched antibody (mouse IgG2a κ for TLR5) were used as negative controls. Cells were stained with biotinylated anti-mouse TLRs (TLR2, TLR3, TLR4, TLR9) (eBioscience, San Diego, CA) or anti-mouse TLR5 (IMGENEX, San Diego, CA) for 20 min at 4°C, followed by streptavidin-FITC or FITC-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (Zymed Laboratories, South San Francisco, CA), respectively. Cells were then fixed and permeabilized with the eBioscience Fixation/Permeabilization kit (eBioscience, San Diego, CA), and restained with the same antibodies for 20 min at 4°C to obtain intracellular staining. Cells were washed in PBS and analyzed by FACS Calibur (BD Biosciences, Bedford, MA) and CellQuest software (BD Biosciences, Bedford, MA).

Cell proliferation assays

Mice were injected with 120 mg/kg of bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU, Sigma, St. Louis, MO) i.p., 90 min prior to sacrificing. Paraffin sections of colon and MLN were incubated with 5% skim milk and stained with FITC-conjugated anti-BrdU (BD PharMingen, Mountain View, CA), followed by rabbit anti-mouse CD4 and TRITC-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG. Proliferating CD4+ T cells were determined by fluorescence microscopy.

In vitro cell proliferation was analyzed in freshly isolated CD4+ T cells following three days of stimulation in anti-CD3 precoated 96 well plates (BD Biosciences, Bedford, MA) with 1µg/ml anti-CD28. Single cell suspensions of splenocytes were separated into CD4+CD25- and CD4+CD25+ subsets using negative selection with the anti-CD4 MACS system followed by positive selection with an anti-CD25 MACS column (Miltenyi Biotec, Aburn, CA). In certain experiments, we used TLR ligands, Pam3CSK4 (1µg/ml; Invivogen, San Diego, CA), poly I:C (90µg/ml; Invivogen, San Diego, CA), lipopolysaccharide (LPS) (1µg/ml; Eschericha coli 0111: B4, Invivogen, San Diego, CA), CpG-ODN (1µg/ml; Invivogen, San Diego, CA) as an alternative to anti-CD28. [3H]Thymidine was added during the last 18 hours of culture. To assess Treg suppressor activity, freshly isolated CD4+CD25+ Treg cells were co-cultured with CD4+CD25− T cells at a ratio of 0.125 : 1 (0.125×105 vs. 1×105 per well). [3H]Thymidine incorporation was analyzed with a beta scintillation counter.

For CFSE labeling, CD4+ T cells were incubated in 5µM CFSE (Molecular Probes, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) in PBS at 37°C for 15min. CFSE-labeled cells (5×105) were injected i.p. into RAG1−/− mice. After 7 days, CD4+ T cells were isolated from spleen, MLN, and the colon as described above. Cell division was analyzed by flow cytometry detecting CFSE fluorescence.

Statistical analysis

Results were expressed as mean ± SD. Data were analyzed by Student’s t-test using the statistics package within Microsoft Excel. P values were considered significant when < 0.05.

Results

CD4+CD45Rbhigh T cells express TLRs

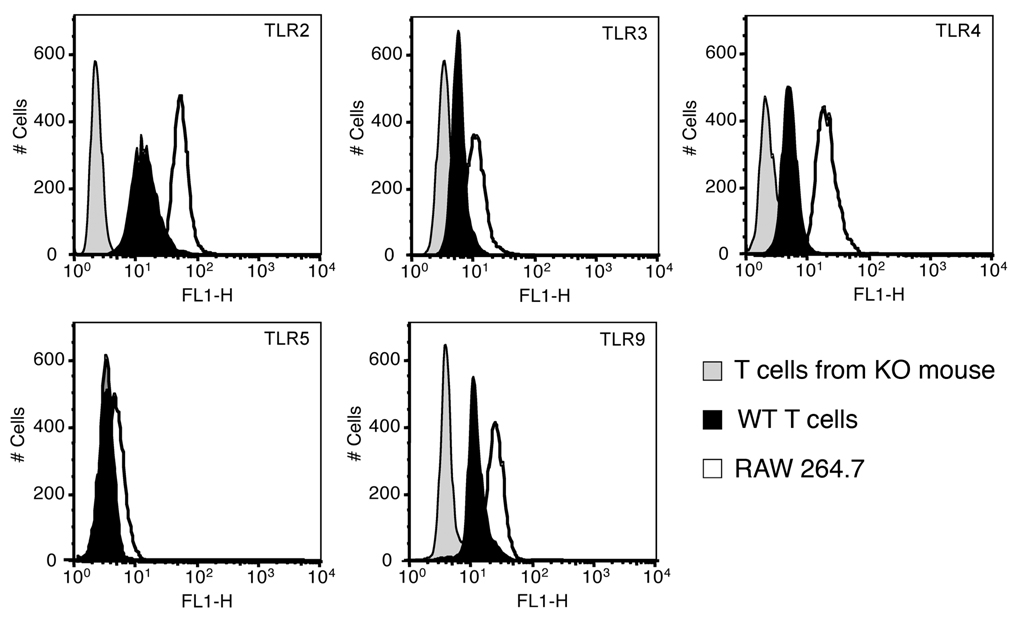

Several studies have previously demonstrated the expression of TLRs on T cells (16–21). However, most of the previous work only examined expression at the mRNA level. We examined the expression of TLR protein in CD4+CD45Rbhigh T cells isolated from spleens of WT mice by flow cytometry (Figure 1). We focused on TLR2, TLR4, TLR5, TLR9 because of their relevance to luminal bacterial antigens. We also examined the expression of TLR3 because of viral pathogens. Although TLR expression was lower than that seen in the mouse macrophage cell line RAW 264.7 cells, CD4+CD45Rbhigh T cells expressed significant levels of TLR2, TLR4, TLR9, and TLR3. TLR5 was barely detectable.

Figure 1. TLR expression on CD4+CD45Rbhigh CD4+ T cells.

Expression of TLRs on CD4+CD45Rbhigh CD4+ T cells. Splenic CD4+CD45Rbhigh CD4+ T cells were examined for TLR2, TLR3, TLR4, TLR5, and TLR9 expression by flow cytometry (black peaks are CD4+CD45Rbhigh CD4+ T cells of WT mice, gray peaks are CD4+CD45Rbhigh CD4+ T cells from individual knock-out mice, and white peaks are RAW 264.7 cells). The isotype control Ab is used for TLR5 staining.

MyD88 signaling modulates T cell proliferation

We next addressed whether TLR signaling contributes to T cell function using MyD88−/− T cells. To examine T cell activation, CD4+CD25− T cells were cultured for three days with anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 and proliferation was measured by [3H]thymidine incorporation. MyD88−/− T cells showed 50% less proliferation than WT T cells (Figure 2A). In addition, we found that exogenous TLR ligands (TLR2, TLR4, TLR9 ligands) could act as a costimulus to anti-CD3 activation in WT CD4+CD25− T cells but not in MyD88−/− CD4+CD25− T cells (Figure 2B). By contrast, The TLR3 ligand caused similar degrees of proliferation between WT T cells versus MyD88−/− T cells, consistent with being an MyD88-independent TLR.

Figure 2. Absence of MyD88 signaling results in defective CD4+ T cell function in vitro.

A. MyD88−/− T cells have decreased proliferation. Proliferation of CD4+CD25− T cells in the presence of anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 mAbs, measured by [3H]thymidine incorporation after three days in culture. Values indicate average counts (±SD) of triplicate wells for three individual experiments (*P<0.05).

B. T cell proliferation by exogenous TLR ligands. CD4+CD25− T cells were stimulated with anti-CD3 in the presence or absence of TLR ligands (without anti-CD28). Cell proliferation was measured by [3H]thymidine incorporation after three days in culture. Values indicate average counts (±SD) of triplicate wells for three individual experiments (*P<0.05).

C. MyD88−/− Tregs have decreased suppressor function. CD4+CD25+ Treg cells were co-cultured with CD4+CD25− T cells at a ratio of 0.125 : 1 (0.125×105 vs. 1×105 per well) for three days with stimulation by anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 mAbs. Values indicate average counts (±SD) in triplicate wells in three individual experiments (*P<0.05).

Given the decrease in proliferation in MyD88−/− T cell with TCR activation, we investigated whether there were differences in total T cell numbers between WT mice and MyD88−/− mice. We isolated CD4+ cells from spleens and lamina propria of WT or MyD88−/− mice and found similar numbers of CD4+ T cells, CD8+ T cells, B cells (CD19), Gr-1 positive cells, or CD4+CD25+ Tregs. Thus in the MyD88−/− mouse other compensatory mechanisms result in normal numbers of cells even in the lamina propria.

To examine the function of MyD88−/− Tregs, WT CD4+CD25− T cells were co-cultured with either WT or MyD88−/− CD4+CD25+ Tregs. MyD88−/− Tregs showed a decreased ability to suppress the proliferation of allogeneic T cells challenged with anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 (Figure 2C). Thus in MyD88−/− mice there are no apparent defects in T cell numbers in the periphery or the intestine under homeostatic conditions but in vitro functional responses are perturbed.

MyD88−/− CD4+CD45Rbhigh T cells are defective in their ability to induce colitis in RAG1−/− mice

To clarify the role of TLR signaling in CD4+CD45Rbhigh T cells in vivo, we adoptively transferred CD4+CD45Rbhigh T cells isolated from MyD88−/− or WT spleen into RAG1−/− mice. After nine weeks, mice transferred with WT T cells demonstrated significant loss of body weight as previously described (34). However, mice receiving MyD88−/− CD4+CD45Rbhigh T cells showed significantly less weight loss (Figure 3A, B). Histological examination of the colon showed that mice receiving MyD88−/− T cells had significantly decreased severity of colitis compared to that of WT T cell transferred mice (colitis score: 11.1±2.9 vs. 3.6±3.7, P<0.001, max score: 20). Importantly, MyD88−/− lymphocytes did home to the intestine and other compartments but did not induce colitis. Indeed, MyD88−/− T cells in peripheral blood expressed the mucosal homing marker α4β7 to a similar extent compared with WT T cells (data not shown).

Figure 3. Defective function of MyD88−/− naïve T cells and Tregs in the T cell transfer colitis model.

A. MyD88−/− CD4+CD45Rbhigh CD4+ T cells do not cause weight loss in RAG1−/− mice after transfer. CD4+CD45Rbhigh T cells isolated from MyD88−/− (n=12) and WT (n=8) mice spleen were injected i.p. into RAG1−/− mice. Mice were weighed weekly. The graph shows percent body weight change. The data represent the average (±SD) of five independent experiments (*P<0.05).

B. Histology of the colon of RAG1−/− mice nine weeks after transfer of naïve T cells. The colons in mice receiving WT T cells (WT hi) show a severe inflammatory cell infiltrate, crypt loss, and distortion. Mice receiving MyD88−/− T cells (MyD88−/− hi) have less inflammation compared to the mice receiving WT T cells.

C. Tregs from MyD88−/− mice do not protect from colitis induced by WT CD4+CD45Rbhigh CD4+ T cell transfer in RAG1−/− mice. CD4+CD45Rbhigh T cells isolated from WT mice were co-transferred with either WT Tregs or MyD88−/− Tregs (n=6 each) into RAG1−/− mice. The graph shows weekly percent body weight change. The data represent the average (±SD) of three independent experiments (*P<0.05).

D. Histology of the colon of RAG1−/− mice nine weeks after co-transfer of Tregs with WT naïve T cells. WT Tregs but not MyD88−/− Tregs protect against naïve T cell induced colitis.

Defective Treg function in TLR2−/− mice has been previously reported (38). We therefore examined MyD88−/− Treg function in the colitis transfer model. WT CD4+CD45Rbhigh T cells were co-transferred with either WT Tregs or MyD88−/− Tregs, and the severity of the colitis was compared after nine weeks. Tregs from MyD88−/− mice did not protect against colitis induced by WT CD4+CD45Rbhigh T cells (Figure 3C, D). Histological severity of the colitis revealed a marginal suppressive effect of the MyD88−/− Tregs, but the severity score was significantly higher than in mice co-transferred with WT Tregs (colitis score: MyD88−/− Tregs 7.7±3.9 vs. WT Tregs 3.6±3.1, P<0.01, max: 20). These results indicate that CD4+CD45Rbhigh T cells from MyD88−/− mice exhibit an impaired ability to induce chronic colitis in the adoptive transfer model. In addition, MyD88-dependent TLR signaling is required for optimal Treg function in vivo.

CD4+CD45Rbhigh T cells from MyD88−/− mice exhibit decreased proliferation in MLNs and the lamina propria when transferred into RAG1−/− mice

Given the in vitro findings that MyD88−/− T cells have a decreased ability to proliferate in response to TCR stimulation yet have normal numbers of T cells in situ, we next addressed whether this decreased ability to proliferate also occurred when T cells were transferred to a TLR sufficient host, namely the RAG1−/− mice. First we compared the total number of CD4+ T cells isolated from lamina propria between MyD88−/− T cell transferred mice and WT T cells transferred mice (Figure 4A). RAG1−/− mice receiving MyD88−/− T cells had significantly fewer lamina propria CD4+ T cells than mice receiving WT T cells.

Figure 4. Decreased proliferation of MyD88−/− T cells after transfer into RAG1−/− mice.

A. The number of CD4+ T cells in the lamina propria of RAG1−/− mice nine weeks after naïve T cell transfer. The data represent the mean (±SD) of three mice each (*P<0.05).

B. BrdU labeling of proliferating cells in the lamina propria and MLN taken from RAG1−/− mice receiving WT or MyD88−/− naïve T cells. Representative pictures show BrdU positive cells (green) and CD4+ cells (red), appearing yellow. RAG1−/− mice receiving WT T cells have more proliferating cells in both the lamina propria and MLN than mice receiving MyD88−/− T cells.

C. Decreased MyD88−/− CD4+ T cell proliferation in MLN of RAG1−/− mice observed seven days after transfer. CD4+ T cells isolated from MyD88−/− and WT mice spleen were labeled with CFSE and injected i.p. into RAG1−/− mice. Division of CFSE labeled cells was analyzed by flow cytometry. White peaks show the initial CFSE fluorescence (before injection). WT CD4+ T cells show more dividing cells than MyD88−/− CD4+ T cells in the MLN, represented by the broader shoulder of dividing cells in the WT MLN panel (upper left panel).

To confirm whether this difference in T cell number was due to defective proliferation of MyD88−/− T cells in vivo, we examined local T cell proliferation by BrdU labeling at nine weeks after T cell transfer (Figure 4B). Double staining of the colon and MLN with anti-CD4 and anti-BrdU showed less proliferation of CD4+ T cells in mice receiving MyD88−/− CD4+CD45Rbhigh T cells than those receiving WT CD4+CD45Rbhigh T cells. We next examined the dynamic proliferative ability of the CD4+ T cells using CFSE labeling. CD4+ T cells from WT mice and MyD88−/− mice were labeled with CFSE and transferred to RAG1−/− mice. Cell division was analyzed by flow cytometry on the seventh day after transfer (Figure 4C). Transferred T cells from MyD88−/− mice showed fewer cell divisions in MLN than T cells from WT mice. These results suggest that MyD88−/− CD4+CD45Rbhigh T cells have defective proliferation in vivo.

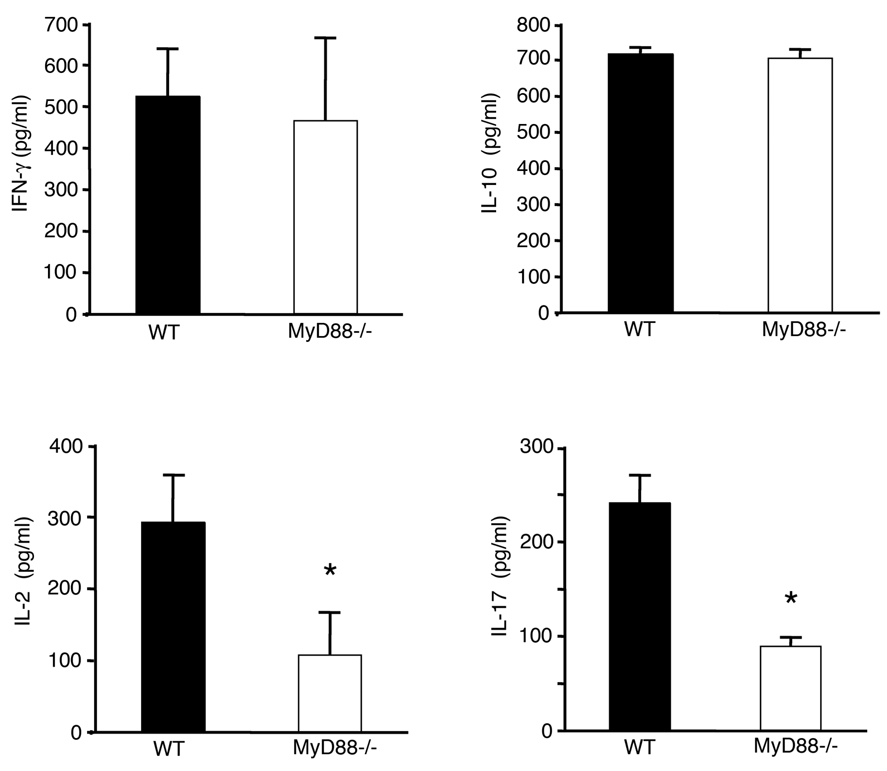

Secretion of IL-2 and IL-17 is significantly lower in colonic CD4+ T cells from RAG1−/− mice receiving MyD88−/− T cells than in mice receiving WT T cells

Given the results suggesting proliferative defects in MyD88−/− CD4+CD45Rbhigh T cells, we next addressed whether cytokine expression and T cell polarization were altered in MyD88−/− T cells in the colitis model. CD4+ T cells isolated from the lamina propria in mice receiving MyD88−/− T cells were co-cultured with lamina propria DCs, isolated from the same mouse, and stimulated with anti-CD3 for 48 hours. Supernatants were analyzed for cytokine production by ELISA. There were no differences in the production of IFN-γ or IL-10 between MyD88−/− CD4+ T cells and WT CD4+ T cells (Figure 5). By contrast, the production of IL-2 and IL-17 was significantly lower in MyD88−/− CD4+ T cells than in WT CD4+ T cells (Figure 5). These results suggest that MyD88−/− T cells are specifically defective in Th17 polarization. In addition, impaired expression of IL-2 may be part of the reason for defective T cell proliferation observed in MyD88−/− CD4+ T cells.

Figure 5. Decreased IL-2 and IL-17 production by MyD88−/− T cells in lamina propria after transfer into RAG1−/− mice.

CD4+ T cells isolated from the lamina propria in mice receiving MyD88−/− T cells and mice receiving WT T cells were co-cultured with lamina propria DCs isolated from the same mouse, and stimulated with anti-CD3 for 48 hours. IFN-γ, IL-10, IL-2, and IL-17 in the supernatant were analyzed by ELISA. Values indicate average concentrations (±SD) of duplicate wells in three individual experiments (*P<0.05).

Mucosal IL-6 and IL-23 expression are decreased in RAG1−/− mice receiving MyD88−/− T cells

T cell polarization is regulated by cytokines present during the initial stage of TCR ligation (39). Th17 polarization is specifically mediated by dendritic cell-derived cytokines IL-23 and IL-6 under the influence of TGF-β (40). To clarify whether defective Th17 differentiation of MyD88−/− T cells is associated with a decrease in these upstream cytokines, we examined the expression of IL-23p19 and IL-6 in the colonic mucosa using real time PCR. Compared to mice receiving WT T cells, mice that received MyD88−/− T cells had significantly decreased mRNA expression of both IL-23 and IL-6 (Figure 6). Expression of IL-1β and IL-18 mRNA in the colonic mucosa was slightly decreased in mice receiving MyD88−/− T cells but did not reach statistical significance (data not shown). These results suggest that MyD88 function in CD4+CD45Rbhigh T cells is required to prime lamina propria APCs to produce these cytokines.

Figure 6. Decreased mucosal expression of IL-6 and IL-23 mRNA in RAG1−/− mice receiving MyD88−/− T cells.

TaqMan real-time PCR demonstrates up regulation of mucosal IL-6 and IL-23 expression in the colon of mice receiving WT T cells but not in mice receiving MyD88−/− T cells nine weeks after transfer (n=7 each). Values indicate average relative values (±SD) (*P<0.05).

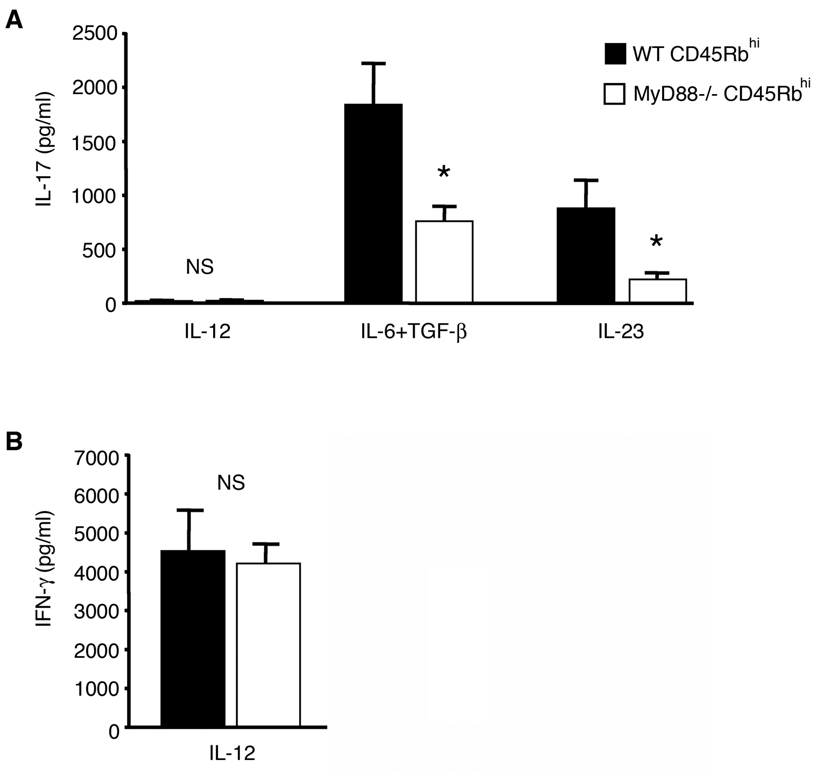

MyD88 is required for the induction of Th17 differentiation in vitro

Thus far, we found that differentiation of MyD88 CD4+CD45Rbhigh T cells into Th17 cells was defective in vivo and that expression of IL-6 and IL-23 were also decreased in vivo. We then wished to examine whether the defect in Th17 differentiation could be overcome with exogenous administration of cytokines in vitro. Polarization of T cells was performed as previously described (36, 37). WT and MyD88−/− CD4+CD45Rbhigh T cells primed with IL-12 and treated with anti-IL-4 expressed equal amounts of the Th1 cytokine IFN-γ (Figure 7B). In contrast, Th17 differentiation was very different between MyD88−/− CD4+CD45Rbhigh T cells and WT T cells. Whereas priming with IL-6 plus TGF-β, or IL-23 induced IL-17 expression in WT CD4+CD45Rbhigh T cells, MyD88−/− CD4+CD45Rbhigh T cells expressed significantly less IL-17 (Figure 7A). These results suggest that MyD88−/− CD4+CD45Rbhigh T cells have an inherent defect in Th17 but not Th1 polarization.

Figure 7. MyD88 is required for induction of Th17 differentiation in vitro.

A. Defective in vitro Th17 differentiation in MyD88−/− CD4+CD45Rbhigh T cells. MyD88−/− CD4+CD45Rbhigh T cells or WT T cells were stimulated as described in Methods in the presence of IL-12, IL-6 plus TGF-β or IL-23 and IL-17 production measured (* P<0.05).

B. MyD88 is not required Th1 differentiation. MyD88−/− CD4+CD45Rbhigh T cells or WT T cells were stimulated as described in Methods in the presence of IL-12 and IFN-γ measured (NS; not significant).

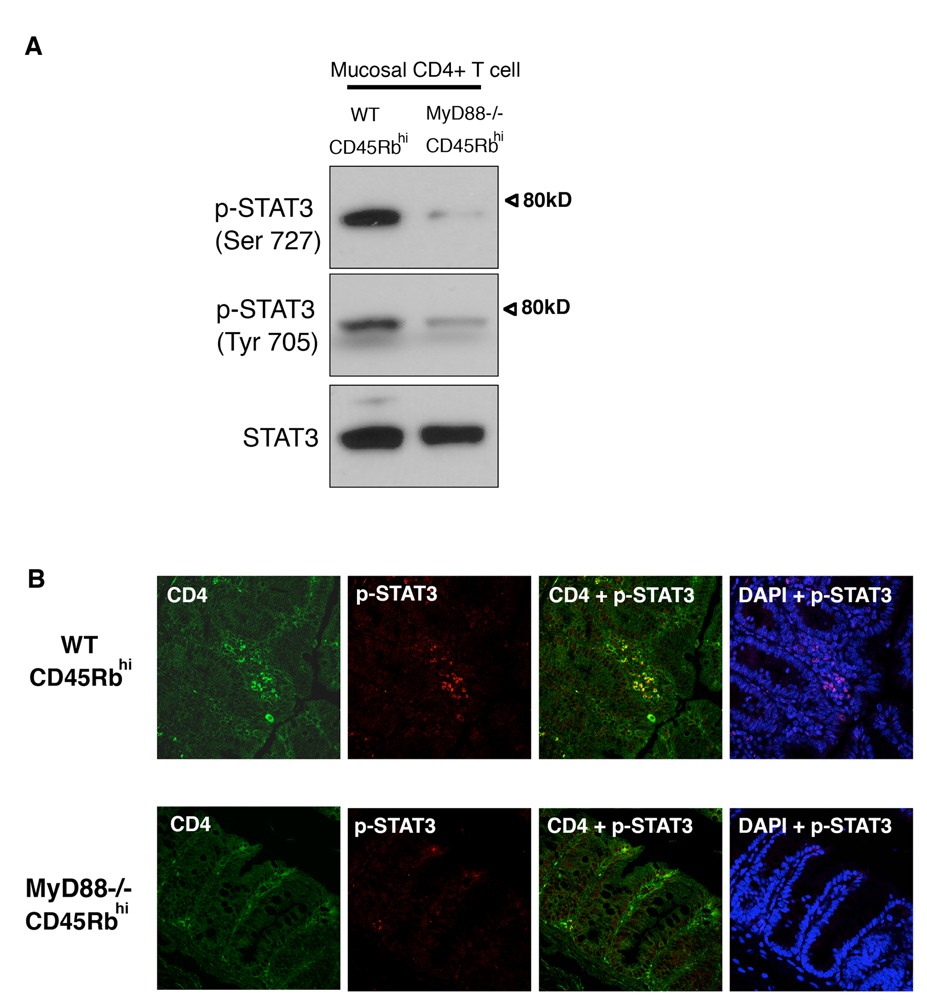

STAT3 phosphorylation in mucosal CD4+ T cells is decreased in MyD88−/− T cell transferred mice

STAT3 is active in the colon in IBD (41, 42), and plays a pivotal role in the pathogenesis of colitis following adoptive T cell transfer (43). In addition, activation of STAT3 in response to IL-6 and IL-23 is required for Th17 development by CD4+ T cells (15, 44, 45). IL-17 further induces the activation of STAT3, leading to a positive feedback loop to sustain inflammation (46). We analyzed the phosphorylation state of STAT3 in lamina propria CD4+ T cells of both WT and MyD88−/− T cell transferred RAG1−/− mice (Figure 8A). Activation of STAT3 is regulated by phosphorylation of Tyr705 and Ser727. Consistent with the altered expression of IL-17, STAT3 phosphorylation was greater in the lamina propria CD4+ T cells from mice receiving WT T cells than the cells from mice receiving MyD88−/− T cells.

Figure 8. STAT3 activation in mucosal CD4+ T cells.

A. Western blot analysis of serine and tyrosine phosphorylation of STAT3 in CD4+ T cells isolated from the lamina propria. RAG1−/− mice receiving MyD88−/− T cells and the mice receiving WT T cells were examined for STAT3 activation nine weeks after transfer. Mice receiving MyD88−/− T cells show less phosphorylation of STAT3 in CD4 T cells.

B. Immunofluorescent staining of CD4+ mucosal cells (green) and phospho-STAT3 (Ser727)(red), DAPI (blue) identifies nuclei. The top panel shows colonic mucosa of RAG1−/− mice receiving WT T cells and the bottom panel shows the mucosa of mice receiving MyD88−/− T cells. Cytoplasmic localization of phospho-STAT3 is represented by yellow and nuclear localization of phospho-STAT3 is represented by pink.

We also examined the localization of phosphorylated STAT3 (Ser727) in colonic tissues of those mice by immunohistochemistry (Figure 8B). Most of the lamina propria CD4+ T cells were positive for phospho-STAT3 in mice receiving WT T cells but very few phospho-STAT3 positive cells were found in the mice receiving MyD88−/− T cells. Cytoplasmic as well as nuclear localization of phospho-STAT3 was observed in CD4+ T cells in mice receiving WT T cells but no nuclear localization was seen in mice receiving MyD88−/− T cells. These results suggest that the observed defects of MyD88−/− T cells in the development of the colitis might be due to decreased STAT3 activation.

Discussion

Many aspects of the interface between innate and adaptive immunity remain unexplored. It is particularly interesting to ponder how adaptive immune responses are regulated in the intestine given its coexistence with the microflora. We show that CD4+CD45Rbhigh T cells from MyD88−/− mice exhibit multiple defects in establishing a pathogenic adaptive response to host signals and the luminal microenvironment during chronic colitis. Among the defects we identified, MyD88−/− T cells are unable to be activated and to differentiate into Th17 effector cells, thereby preventing expansion and sustained inflammation. MyD88−/− CD4+ T cells show decreased production of IL-2 and a reduction in proliferation in response to TCR stimulation. Tregs from MyD88−/− mice were also defective in protecting against colitis induced by WT CD4+CD45Rbhigh T cells. Therefore, signaling via MyD88 on CD4+CD45Rbhigh T cells appears to be required for the proliferation and Th17 differentiation of T cells. MyD88 signaling is also required for Treg-mediated suppression of colitogenic T cells. These results suggest a significant role for TLR signaling by T cells in the development of IBD.

The adoptive transfer model of colitis provides an ideal mechanism by which to test the hypothesis that TLR signaling by T cells is important for their function. Extensive previous work in this model has highlighted the dependence of luminal bacteria in the development of colitis (35, 47). In particular, Powrie et al., has shown that intestinal bacteria are necessary in the recipient mouse in order to develop colitis (34). CD4+CD45Rbhigh T cells from germ-free mice can still induce wasting disease as long as bacteria are present in the recipient mouse. Our study has taken advantage of MyD88−/− mice with the notion that these mice are effectively unable to signal through TLRs. A previous study has found that crossing MyD88−/− mice to IL-10−/− mice protects against the development of colitis (48). But in that study, all the cells of the mouse are null for both IL-10 and MyD88 including APC’s and T cells. By contrast, our study allows us to dissect the role of MyD88-dependent signaling within the T cell compartment. Given what was known about T cell development in MyD88−/− mice, we had initially hypothesized that the transfer of CD4+CD45Rbhigh MyD88−/− T cells into a TLR-positive environment, namely the RAG1−/−, would be sufficient to induce colitis. We were surprised by the degree to which MyD88 −/− CD4+CD45Rbhigh T cells were unable to cause colitis.

We described significant expression of TLR2, TLR3, TLR4, and TLR9 protein on murine CD4+CD45Rbhigh T cells. There are several conflicting reports in terms of TLR expression in murine T cells (17, 49, 50). Marsland et al. demonstrated TLR4, TLR7, TLR9 mRNA expression, whereas Sobek et al. reported TLR1, TLR2, TLR6 mRNA expression. Another study described expression of TLR2, TLR3, TLR4, TLR5, TLR9 mRNA (17), but we could not detect TLR5 protein expression. Although the discrepancy may be due to the differences between mRNA and protein expression, others have shown the absence of TLR5 mRNA in CD4+CD45Rbhigh T cells consistent with our finding of absent TLR5 protein (19). Interestingly, it has been reported that TLR4 and TLR2 mRNA expression become undetectable while TLR3 and TLR9 mRNA are up-regulated in naïve T cells (CD44lowCD25-CD4+) after stimulation with anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 (17). Therefore, TLR expression may vary with T cell activation state and highlights the developmental role of TLRs on T cells.

Our results demonstrate that there is impaired activation of MyD88−/− CD4+CD45Rbhigh T cells after adoptive transfer into RAG1−/− mice. Although this population is meant to represent a population of activation naïve cells, clearly this may be a heterogeneous population (51). Nevertheless, the CD45Rb surface antigen permits us to identify a subpopulation of cells that has been well-characterized in this animal model. Several possible mechanisms may underlie the defect in MyD88−/− T cells. APCs express TLRs normally in the RAG1−/− mice. The primary defects in T cell function seen must therefore lie within the T cell compartment itself. Previous reports have demonstrated that MyD88−/− T cells have decreased OVA-specific proliferation and IL-2 production compared to WT T cells when Tregs were depleted with anti-CD25 antibody (52). Lack of CD4+ T cell memory function in MyD88−/− mice has also been demonstrated (52). These results imply that MyD88−/− effector T cells are defective. In our work, MyD88−/− T cells did not respond properly to TCR stimulation with co-stimulation by anti-CD28 in vitro. Several previous reports have suggested that TLRs function in co-stimulation of T cells but conventional co-stimulation with anti-CD28 can bypass the effect of TLR signaling (17, 25, 53). We could not overcome the TLR defect in MyD88−/− T cells by anti-CD3/CD28 stimulation in vitro. In vivo, APC’s expressing CD28 also could not compensate for the absence of a MyD88 dependent signal in CD4+CD45Rbhigh T cell activation.

The second possibility accounting for defective T cell function is impaired cytokine secretion. MyD88−/− mice have been reported to be deficient in the induction of Th1 immune responses (13, 14, 54). Because MyD88−/− T cells express similar amounts of IFN-γ compared to WT T cells, Th1 differentiation can occur in the absence of MyD88-dependent signaling (55, 56). By contrast, expression of IL-17 was decreased in MyD88−/− T cells, suggesting that IL-17 production is regulated by MyD88-dependent signals. Recent reports have suggested the importance of IL-17 producing cells in the pathogenesis of the adoptive transfer model of colitis (57, 58). Previous studies have also found that Th1 cytokines, in particular IFN-γ, are required for colitis (59–61). Our results would suggest that, in the absence of IL-17, the maximal degree of colitis cannot be achieved. These findings do not, however, diminish the importance of IFN-γ since RAG1−/− receiving MyD88−/− do develop a mild colitis. Consistent with a reduction in Th17 cells, mucosal expression of IL-6 and IL-23 was decreased in mice receiving MyD88−/− T cells compared to mice receiving WT T cells. These results indicate that there is crosstalk between mucosal DCs and CD4+ T cells to establish an appropriate adaptive immune response. Sequential cytokine production is also involved in establishing proper T cell effector function. IL-1β and IL-18 enhance IL-6 production from DCs and potentiate IL-17 production in the presence of IL-23 (62). Given that MyD88−/− cells cannot respond to these cytokines, this may be yet another way in which Th17 differentiation is impaired in vivo. We suggest that MyD88-dependent signaling in CD4+ T cells is required to establish mucosal DC–CD4+ T cell crosstalk, and consequent IL-17 production necessary for colitis.

STAT3 is a transcription factor that requires phosphorylation for activation and plays an important role in Th17 differentiation (63–66). Our results demonstrate that mucosal STAT3 activation is greater in the mice receiving WT T cells than in the mice receiving MyD88−/− T cells. STAT3 is constitutively activated in mucosal CD4+ T cells of patients with IBD and in murine colitis, and plays an important role in the perpetuation of colitis (41–43, 67, 68). On the other hand, tissue-specific gene deletion of STAT3 in myeloid cells induces a chronic enterocolitis (69, 70), suggesting that STAT3 signaling in myeloid cells protects against intestinal inflammation. The mechanism of STAT3-dependent protection involves IL-10 production by macrophages. We reason that decreased STAT3 activation in the mucosa of mice receiving MyD88−/− T cells is due to the decreased activation of T cells in those mice, since myeloid cell function should be preserved in the RAG1−/− recipient mice whether they receive WT T cells or MyD88−/− T cells. STAT3 is involved in IL-17 production, and conversely, IL-17 activates STAT3 (15, 44–46). Therefore, the sequence of events leading to defective STAT3 activation and IL-17 production may underlie the inability of MyD88−/− CD4+CD45Rbhigh T cells to induce chronic colitis in RAG1−/− mice.

In this study, we illustrate an important role of MyD88 in the establishment of pathogenic adaptive immunity. In the absence of MyD88 signaling, CD4+CD45Rbhigh T cells can home to the intestine but do not acquire the phenotype of colitogenic T cells characterized by IL-17 production, STAT3 activation, and aberrant, non-homeostatic levels of T cell proliferation. Therefore, traditional innate immune signaling may have a greater role in adaptive immunity than originally recognized. Our results enhance the understanding of the link between innate immune defects and abnormal T cell activation in response to luminal commensal bacteria in IBD. Inhibition of MyD88 in select T cell compartments may be useful in the treatment of IBD.

Abbreviations

- TLR

toll-like receptor

- MyD88

myeloid differentiation factor 88

- PAMP

pathogen associated molecular pattern

- LPS

lipopolysaccharide

- PBMC

peripheral blood mononuclear cells

- IEC

intestinal epithelial cells

Footnotes

Supported by NIH grants AI052266 (MTA), DK069594 (MTA), Uehara Memorial Foundation Research Fellowship (MF).

References

- 1.Ogura Y, Bonen DK, Inohara N, Nicolae DL, Chen FF, Ramos R, Britton H, Moran T, Karaliuskas R, Duerr RH, Achkar JP, Brant SR, Bayless TM, Kirschner BS, Hanauer SB, Nunez G, Cho JH. A frameshift mutation in NOD2 associated with susceptibility to Crohn's disease. Nature. 2001;411:603–606. doi: 10.1038/35079114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hugot JP, Chamaillard M, Zouali H, Lesage S, Cezard JP, Belaiche J, Almer S, Tysk C, O'Morain CA, Gassull M, Binder V, Finkel Y, Cortot A, Modigliani R, Laurent-Puig P, Gower-Rousseau C, Macry J, Colombel JF, Sahbatou M, Thomas G. Association of NOD2 leucine-rich repeat variants with susceptibility to Crohn's disease. Nature. 2001;411:599–603. doi: 10.1038/35079107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tumer Z, Croucher PJ, Jensen LR, Hampe J, Hansen C, Kalscheuer V, Ropers HH, Tommerup N, Schreiber S. Genomic structure, chromosome mapping and expression analysis of the human AVIL gene, and its exclusion as a candidate for locus for inflammatory bowel disease at 12q13-14 (IBD2) Gene. 2002;288:179–185. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(02)00478-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Duerr RH, Taylor KD, Brant SR, Rioux JD, Silverberg MS, Daly MJ, Steinhart AH, Abraham C, Regueiro M, Griffiths A, Dassopoulos T, Bitton A, Yang H, Targan S, Datta LW, Kistner EO, Schumm LP, Lee AT, Gregersen PK, Barmada MM, Rotter JI, Nicolae DL, Cho JH. A genome-wide association study identifies IL23R as an inflammatory bowel disease gene. Science. 2006;314:1461–1463. doi: 10.1126/science.1135245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Van Limbergen J, Russell RK, Nimmo ER, Ho GT, Arnott ID, Wilson DC, Satsangi J. Genetics of the innate immune response in inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2006 doi: 10.1002/ibd.20096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Young Y, Abreu MT. Advances in the pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel disease. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2006;8:470–477. doi: 10.1007/s11894-006-0037-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kucharzik T, Maaser C, Lugering A, Kagnoff M, Mayer L, Targan S, Domschke W. Recent understanding of IBD pathogenesis: implications for future therapies. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2006;12:1068–1083. doi: 10.1097/01.mib.0000235827.21778.d5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Duchmann R, Kaiser I, Hermann E, Mayet W, Ewe K, Meyer zum Buschenfelde KH. Tolerance exists towards resident intestinal flora but is broken in active inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) Clin Exp Immunol. 1995;102:448–455. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.1995.tb03836.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cohavy O, Bruckner D, Gordon LK, Misra R, Wei B, Eggena ME, Targan SR, Braun J. Colonic bacteria express an ulcerative colitis pANCA-related protein epitope. Infect Immun. 2000;68:1542–1548. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.3.1542-1548.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Abreu MT, Fukata M, Arditi M. TLR signaling in the gut in health and disease. J Immunol. 2005;174:4453–4460. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.8.4453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pasare C, Medzhitov R. Toll-like receptors: linking innate and adaptive immunity. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2005;560:11–18. doi: 10.1007/0-387-24180-9_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sato S, Sanjo H, Takeda K, Ninomiya-Tsuji J, Yamamoto M, Kawai T, Matsumoto K, Takeuchi O, Akira S. Essential function for the kinase TAK1 in innate and adaptive immune responses. Nat Immunol. 2005;6:1087–1095. doi: 10.1038/ni1255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Scanga CA, Aliberti J, Jankovic D, Tilloy F, Bennouna S, Denkers EY, Medzhitov R, Sher A. Cutting edge: MyD88 is required for resistance to Toxoplasma gondii infection and regulates parasite-induced IL-12 production by dendritic cells. J Immunol. 2002;168:5997–6001. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.12.5997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schnare M, Barton GM, Holt AC, Takeda K, Akira S, Medzhitov R. Toll-like receptors control activation of adaptive immune responses. Nat Immunol. 2001;2:947–950. doi: 10.1038/ni712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Harrington LE, Mangan PR, Weaver CT. Expanding the effector CD4 T-cell repertoire: the Th17 lineage. Curr Opin Immunol. 2006;18:349–356. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2006.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Caron G, Duluc D, Fremaux I, Jeannin P, David C, Gascan H, Delneste Y. Direct stimulation of human T cells via TLR5 and TLR7/8: flagellin and R-848 up-regulate proliferation and IFN-gamma production by memory CD4+ T cells. J Immunol. 2005;175:1551–1557. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.3.1551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gelman AE, Zhang J, Choi Y, Turka LA. Toll-like receptor ligands directly promote activated CD4+ T cell survival. J Immunol. 2004;172:6065–6073. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.10.6065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hornung V, Rothenfusser S, Britsch S, Krug A, Jahrsdorfer B, Giese T, Endres S, Hartmann G. Quantitative expression of toll-like receptor 1–10 mRNA in cellular subsets of human peripheral blood mononuclear cells and sensitivity to CpG oligodeoxynucleotides. J Immunol. 2002;168:4531–4537. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.9.4531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Caramalho I, Lopes-Carvalho T, Ostler D, Zelenay S, Haury M, Demengeot J. Regulatory T cells selectively express toll-like receptors and are activated by lipopolysaccharide. J Exp Med. 2003;197:403–411. doi: 10.1084/jem.20021633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zarember KA, Godowski PJ. Tissue expression of human Toll-like receptors and differential regulation of Toll-like receptor mRNAs in leukocytes in response to microbes, their products, and cytokines. J Immunol. 2002;168:554–561. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.2.554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kapsenberg ML. Dendritic-cell control of pathogen-driven T-cell polarization. Nat Rev Immunol. 2003;3:984–993. doi: 10.1038/nri1246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Komai-Koma M, Jones L, Ogg GS, Xu D, Liew FY. TLR2 is expressed on activated T cells as a costimulatory receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:3029–3034. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400171101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Imanishi T, Hara H, Suzuki S, Suzuki N, Akira S, Saito T. Cutting edge: TLR2 directly triggers Th1 effector functions. J Immunol. 2007;178:6715–6719. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.11.6715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zanin-Zhorov A, Tal-Lapidot G, Cahalon L, Cohen-Sfady M, Pevsner-Fischer M, Lider O, Cohen IR. Cutting edge: T cells respond to lipopolysaccharide innately via TLR4 signaling. J Immunol. 2007;179:41–44. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.1.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gelman AE, LaRosa DF, Zhang J, Walsh PT, Choi Y, Sunyer JO, Turka LA. The adaptor molecule MyD88 activates PI-3 kinase signaling in CD4+ T cells and enables CpG oligodeoxynucleotide-mediated costimulation. Immunity. 2006;25:783–793. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.08.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Suzuki N, Suzuki S, Millar DG, Unno M, Hara H, Calzascia T, Yamasaki S, Yokosuka T, Chen NJ, Elford AR, Suzuki J, Takeuchi A, Mirtsos C, Bouchard D, Ohashi PS, Yeh WC, Saito T. A critical role for the innate immune signaling molecule IRAK-4 in T cell activation. Science. 2006;311:1927–1932. doi: 10.1126/science.1124256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sutmuller RP, Morgan ME, Netea MG, Grauer O, Adema GJ. Toll-like receptors on regulatory T cells: expanding immune regulation. Trends Immunol. 2006;27:387–393. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2006.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Crellin NK, Garcia RV, Hadisfar O, Allan SE, Steiner TS, Levings MK. Human CD4+ T cells express TLR5 and its ligand flagellin enhances the suppressive capacity and expression of FOXP3 in CD4+CD25+ T regulatory cells. J Immunol. 2005;175:8051–8059. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.12.8051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Peng G, Guo Z, Kiniwa Y, Voo KS, Peng W, Fu T, Wang DY, Li Y, Wang HY, Wang RF. Toll-like receptor 8-mediated reversal of CD4+ regulatory T cell function. Science. 2005;309:1380–1384. doi: 10.1126/science.1113401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Elson CO, Cong Y, McCracken VJ, Dimmitt RA, Lorenz RG, Weaver CT. Experimental models of inflammatory bowel disease reveal innate, adaptive, and regulatory mechanisms of host dialogue with the microbiota. Immunol Rev. 2005;206:260–276. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2005.00291.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Te Velde AA, de Kort F, Sterrenburg E, Pronk I, Ten Kate FJ, Hommes DW, van Deventer SJ. Comparative analysis of colonic gene expression of three experimental colitis models mimicking inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2006 doi: 10.1002/ibd.20079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Coombes JL, Robinson NJ, Maloy KJ, Uhlig HH, Powrie F. Regulatory T cells and intestinal homeostasis. Immunol Rev. 2005;204:184–194. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2005.00250.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ten Hove T, The Olle F, Berkhout M, Bruggeman JP, Vyth-Dreese FA, Slors JF, Van Deventer SJ, Te Velde AA. Expression of CD45RB functionally distinguishes intestinal T lymphocytes in inflammatory bowel disease. J Leukoc Biol. 2004;75:1010–1015. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0803400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Powrie F, Mauze S, Coffman RL. CD4+ T-cells in the regulation of inflammatory responses in the intestine. Res Immunol. 1997;148:576–581. doi: 10.1016/s0923-2494(98)80152-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Aranda R, Sydora BC, McAllister PL, Binder SW, Yang HY, Targan SR, Kronenberg M. Analysis of intestinal lymphocytes in mouse colitis mediated by transfer of CD4+, CD45RBhigh T cells to SCID recipients. J Immunol. 1997;158:3464–3473. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mathur AN, Chang HC, Zisoulis DG, Stritesky GL, Yu Q, O'Malley JT, Kapur R, Levy DE, Kansas GS, Kaplan MH. Stat3 and Stat4 direct development of IL-17-secreting Th cells. J Immunol. 2007;178:4901–4907. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.8.4901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Park SW, Lee CS, Jang HC, Kim EC, Oh MD, Choe KW. Rapid identification of the coxsackievirus A24 variant by molecular serotyping in an outbreak of acute hemorrhagic conjunctivitis. J Clin Microbiol. 2005;43:1069–1071. doi: 10.1128/JCM.43.3.1069-1071.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sutmuller RP, den Brok MH, Kramer M, Bennink EJ, Toonen LW, Kullberg BJ, Joosten LA, Akira S, Netea MG, Adema GJ. Toll-like receptor 2 controls expansion and function of regulatory T cells. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:485–494. doi: 10.1172/JCI25439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.O'Garra A. Cytokines induce the development of functionally heterogeneous T helper cell subsets. Immunity. 1998;8:275–283. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80533-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Weaver CT, Harrington LE, Mangan PR, Gavrieli M, Murphy KM. Th17: an effector CD4 T cell lineage with regulatory T cell ties. Immunity. 2006;24:677–688. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Atreya R, Mudter J, Finotto S, Mullberg J, Jostock T, Wirtz S, Schutz M, Bartsch B, Holtmann M, Becker C, Strand D, Czaja J, Schlaak JF, Lehr HA, Autschbach F, Schurmann G, Nishimoto N, Yoshizaki K, Ito H, Kishimoto T, Galle PR, Rose-John S, Neurath MF. Blockade of interleukin 6 trans signaling suppresses T-cell resistance against apoptosis in chronic intestinal inflammation: evidence in crohn disease and experimental colitis in vivo. Nat Med. 2000;6:583–588. doi: 10.1038/75068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mudter J, Weigmann B, Bartsch B, Kiesslich R, Strand D, Galle PR, Lehr HA, Schmidt J, Neurath MF. Activation pattern of signal transducers and activators of transcription (STAT) factors in inflammatory bowel diseases. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:64–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.40615.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mudter J, Wirtz S, Galle PR, Neurath MF. A new model of chronic colitis in SCID mice induced by adoptive transfer of CD62L+ CD4+ T cells: insights into the regulatory role of interleukin-6 on apoptosis. Pathobiology. 2002;70:170–176. doi: 10.1159/000068150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yang XO, Panopoulos AD, Nurieva R, Chang SH, Wang D, Watowich SS, Dong C. STAT3 regulates cytokine-mediated generation of inflammatory helper T cells. J Biol Chem. 2007 doi: 10.1074/jbc.C600321200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Parham C, Chirica M, Timans J, Vaisberg E, Travis M, Cheung J, Pflanz S, Zhang R, Singh KP, Vega F, To W, Wagner J, O'Farrell AM, McClanahan T, Zurawski S, Hannum C, Gorman D, Rennick DM, Kastelein RA, de Waal Malefyt R, Moore KW. A receptor for the heterodimeric cytokine IL-23 is composed of IL-12Rbeta1 and a novel cytokine receptor subunit, IL-23R. J Immunol. 2002;168:5699–5708. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.11.5699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Subramaniam SV, Cooper RS, Adunyah SE. Evidence for the involvement of JAK/STAT pathway in the signaling mechanism of interleukin-17. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1999;262:14–19. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1999.1156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.De Winter H, Cheroutre H, Kronenberg M. Mucosal immunity and inflammation. II. The yin and yang of T cells in intestinal inflammation: pathogenic and protective roles in a mouse colitis model. Am J Physiol. 1999;276:G1317–G1321. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1999.276.6.G1317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rakoff-Nahoum S, Hao L, Medzhitov R. Role of toll-like receptors in spontaneous commensal-dependent colitis. Immunity. 2006;25:319–329. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Marsland BJ, Nembrini C, Grun K, Reissmann R, Kurrer M, Leipner C, Kopf M. TLR ligands act directly upon T cells to restore proliferation in the absence of protein kinase C-theta signaling and promote autoimmune myocarditis. J Immunol. 2007;178:3466–3473. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.6.3466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sobek V, Birkner N, Falk I, Wurch A, Kirschning CJ, Wagner H, Wallich R, Lamers MC, Simon MM. Direct Toll-like receptor 2 mediated co-stimulation of T cells in the mouse system as a basis for chronic inflammatory joint disease. Arthritis Res Ther. 2004;6:R433–R446. doi: 10.1186/ar1212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Powrie F, Correa-Oliveira R, Mauze S, Coffman RL. Regulatory interactions between CD45RBhigh and CD45RBlow CD4+ T cells are important for the balance between protective and pathogenic cell-mediated immunity. J Exp Med. 1994;179:589–600. doi: 10.1084/jem.179.2.589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pasare C, Medzhitov R. Toll-dependent control mechanisms of CD4 T cell activation. Immunity. 2004;21:733–741. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2004.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Liew FY, Komai-Koma M, Xu D. A toll for T cell costimulation. Ann Rheum Dis. 2004;63 Suppl 2:ii76–ii78. doi: 10.1136/ard.2004.028308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Jankovic D, Kullberg MC, Hieny S, Caspar P, Collazo CM, Sher A. In the absence of IL-12, CD4(+) T cell responses to intracellular pathogens fail to default to a Th2 pattern and are host protective in an IL-10(−/ −) setting. Immunity. 2002;16:429–439. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(02)00278-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Salgame P. Host innate and Th1 responses and the bacterial factors that control Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. Curr Opin Immunol. 2005;17:374–380. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2005.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rivera A, Ro G, Van Epps HL, Simpson T, Leiner I, Sant'Angelo DB, Pamer EG. Innate immune activation and CD4+ T cell priming during respiratory fungal infection. Immunity. 2006;25:665–675. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Elson CO, Cong Y, Weaver CT, Schoeb TR, McClanahan TK, Fick RB, Kastelein RA. Monoclonal anti-interleukin 23 reverses active colitis in a T cell-mediated model in mice. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:2359–2370. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.03.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hue S, Ahern P, Buonocore S, Kullberg MC, Cua DJ, McKenzie BS, Powrie F, Maloy KJ. Interleukin-23 drives innate and T cell-mediated intestinal inflammation. J Exp Med. 2006;203:2473–2483. doi: 10.1084/jem.20061099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Simpson SJ, Shah S, Comiskey M, de Jong YP, Wang B, Mizoguchi E, Bhan AK, Terhorst C. T cell-mediated pathology in two models of experimental colitis depends predominantly on the interleukin 12/Signal transducer and activator of transcription (Stat)-4 pathway, but is not conditional on interferon gamma expression by T cells. J Exp Med. 1998;187:1225–1234. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.8.1225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ito H, Fathman CG. CD45RBhigh CD4+ T cells from IFN-gamma knockout mice do not induce wasting disease. J Autoimmun. 1997;10:455–459. doi: 10.1016/s0896-8411(97)90152-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bregenholt S, Brimnes J, Nissen MH, Claesson MH. In vitro activated CD4+ T cells from interferon-gamma (IFN-gamma)-deficient mice induce intestinal inflammation in immunodeficient hosts. Clin Exp Immunol. 1999;118:228–234. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1999.01058.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Weaver CT, Hatton RD, Mangan PR, Harrington LE. IL-17 family cytokines and the expanding diversity of effector T cell lineages. Annu Rev Immunol. 2007;25:821–852. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.25.022106.141557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Schindler C, Darnell JE., Jr Transcriptional responses to polypeptide ligands: the JAK-STAT pathway. Annu Rev Biochem. 1995;64:621–651. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.64.070195.003201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hirano T, Ishihara K, Hibi M. Roles of STAT3 in mediating the cell growth, differentiation and survival signals relayed through the IL-6 family of cytokine receptors. Oncogene. 2000;19:2548–2556. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Fu XY. STAT3 in immune responses and inflammatory bowel diseases. Cell Res. 2006;16:214–219. doi: 10.1038/sj.cr.7310029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hodge DR, Hurt EM, Farrar WL. The role of IL-6 and STAT3 in inflammation and cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2005;41:2502–2512. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2005.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Musso A, Dentelli P, Carlino A, Chiusa L, Repici A, Sturm A, Fiocchi C, Rizzetto M, Pegoraro L, Sategna-Guidetti C, Brizzi MF. Signal transducers and activators of transcription 3 signaling pathway: an essential mediator of inflammatory bowel disease and other forms of intestinal inflammation. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2005;11:91–98. doi: 10.1097/00054725-200502000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Suzuki A, Hanada T, Mitsuyama K, Yoshida T, Kamizono S, Hoshino T, Kubo M, Yamashita A, Okabe M, Takeda K, Akira S, Matsumoto S, Toyonaga A, Sata M, Yoshimura A. CIS3/SOCS3/SSI3 plays a negative regulatory role in STAT3 activation and intestinal inflammation. J Exp Med. 2001;193:471–481. doi: 10.1084/jem.193.4.471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Takeda K, Clausen BE, Kaisho T, Tsujimura T, Terada N, Forster I, Akira S. Enhanced Th1 activity and development of chronic enterocolitis in mice devoid of Stat3 in macrophages and neutrophils. Immunity. 1999;10:39–49. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80005-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Welte T, Zhang SS, Wang T, Zhang Z, Hesslein DG, Yin Z, Kano A, Iwamoto Y, Li E, Craft JE, Bothwell AL, Fikrig E, Koni PA, Flavell RA, Fu XY. STAT3 deletion during hematopoiesis causes Crohn's disease-like pathogenesis and lethality: a critical role of STAT3 in innate immunity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:1879–1884. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0237137100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]