Abstract

In a rat model of neuroinflammation, produced by a 6-day intracerebral ventricular infusion of bacterial lipopolysaccharide (LPS), we reported that the brain concentrations of non-esterified brain arachidonic acid (AA, 20:4 n-6) and its eicosanoid products PGE2 and PGD2 were increased, as were AA turnover rates in certain brain phospholipids and the activity of AA-selective cytosolic phospholipase A2 (cPLA2). The activity of Ca2+-independent iPLA2, which is thought to be selective for the release of docosahexaenoic acid (DHA, 22:6 n-3) from membrane phospholipid, was unchanged. In the present study, we measured parameters of brain DHA metabolism in comparable artificial cerebrospinal fluid (control) and LPS-infused rats. In contrast to the reported changes in markers of AA metabolism, the brain non-esterified DHA concentration and DHA turnover rates in individual phospholipids were not significantly altered by LPS infusion. The formation rates of AA-CoA and DHA-CoA in a microsomal brain fraction were also unaltered by the LPS infusion. These observations indicate that LPS-treatment upregulates markers of brain AA but not DHA metabolism. All of which are consistent with other evidence that suggest different sets of enzymes regulate AA and DHA recycling within brain phospholipids and that only selective increases in brain AA metabolism occur following a 6 day LPS infusion.

Keywords: docosahexaenoic acid, brain, lipopolysaccharide, neuroinflammation, metabolism

Introduction

The brain is enriched in polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFA) that fall into two categories based on a double bond at the n-6 or n-3 position. The most abundant brain PUFA are arachidonic (AA, 20:4 n-6) and docosahexaenoic (DHA, 22:6 n-3) acids, which are mainly esterified at the stereospecific numbered (sn)-2 position of the phospholipid moiety (Ansell 1973). Both AA and DHA, including their oxygenated derivatives, can modulate brain function, alter signal transduction, and disrupt other brain processes (Sergeeva et al. 2002, Crawford et al. 2003, Barcelo-Coblijn et al. 2003, Arvindakshan et al. 2003). The eicosanoids (AA derivatives) and docosanoids (DHA derivatives) may have antagonistic effects during inflammation. Eicosanoids, cyclooxygenase and lipoxygenase products, are considered pro-inflammatory (Shimizu & Wolfe 1990, Flower et al. 1972) while docosanoids, lipoxygenase products, are considered anti-inflammatory (Marcheselli et al. 2003, Hong et al. 2003, Serhan et al. 2002). Therefore, it is important to understand the contribution that different PUFA and their products have in the progression of neurodegeneration associated with inflammation.

Neuroinflammation can be produced experimentally in rat brain by infusing bacterial lipopolysaccharide (LPS) into the fourth cerebral ventricle (Hauss-Wegrzyniak et al. 1998a). This causes microglial activation, cytokine accumulation, and death of cholinergic neurons that result eventually in brain atrophy (Willard et al. 1999, Wenk et al. 2000, Rosi et al. 2004). In an earlier study, we reported that 6 days of LPS infusion at a rate of 1 ng/h increased brain activities of the AA-selective Ca2+-dependent cytosolic phospholipase A2 (cPLA2) and secretory PLA2 (sPLA2) by 71% and 47%, respectively, without changing the activity of Ca2+-independent PLA2 (iPLA2) (Rosenberger et al. 2004). The iPLA2 isoform has been suggested to be selective for DHA release from membrane phospholipid (Strokin et al. 2004). A subsequent study from our laboratory using a more selective assay for sPLA2 activity, found that the activity of cPLA2 but not sPLA2 or iPLA2 was increased significantly by the infusion (Basselin et al. 2007). Brain concentrations of non-esterified AA, PGE2, and PGD2, also were elevated, as were turnover rates of AA in ethanolamine and choline glycerophospholipids (Rosenberger et al. 2004), indicating an increase in brain AA metabolism. Consistent with these observations (Rapoport 2001), a 6-day infusion of LPS increased the regional brain incorporation coefficients (k*) of AA from plasma into brain by 31–71%, as imaged by quantitative autoradiography (Lee et al. 2004, Basselin et al. 2007).

In the present study, we examined the effects of a 6 day LPS infusion on brain DHA metabolism. We proposed that the infusion would not change markers of brain DHA metabolism in view of the data showing that the iPLA2 enzyme activity, thought to be selective for DHA, was not altered in the LPS-treated brain and that cytokine formation has been reported to be coupled to cPLA2 and sPLA2 activation (Strokin et al. 2003, Strokin et al. 2004, Dinarello 2002, Luschen et al. 2000). If this is the case, a pathological consequence of neuroinflammation induced by a 6 day LPS infusion may be considered a result of an imbalance between brain AA and DHA metabolism. Therefore, it is not unreasonable that the positive effect of LPS infusion on brain AA, but not DHA metabolism, reflects selective activation of AA-selective cPLA2-mediated signaling.

Materials and Methods

Chemicals

Radiolabeled [1-14C]arachidonic ([1-14C]AA) and docosahexaenoic ([1-14C]DHA) acids (52–60 mCi/mmol) were purchased from Moravek Biochemicals (Brea, CA). The specific radioactivity of the tracers was confirmed by scintillation counting and HPLC analysis. Phospholipid and neutral lipid standards and non-esterified AA and DHA were purchased from Nu-Chek-Prep (Elysian, MN). Bovine serum albumin “fatty acid free”, LPS (E. coli, serotype 055:B5, TCA extraction), reagent grade palmitic acid, potassium phosphate, ATP, and other chemical reagents were from Sigma Chemicals (St. Louis, MO). HPLC grade n-hexane, 2-propanol, and n-heptane were from EM Science (Gibbstown, NJ). Reagent-grade chloroform, methanol, and other chemicals were from Mallinckrodt (Paris, KY). A scintillation cocktail (Ready-Safe, Beckman, Fullerton, CA) containing 1.0 % glacial acetic acid was used to determine radioactivity. Sulfuric acid was from Aldrich Chemicals (Milwaukee, WI).

Rationale, cannula placement, and animal surgery

The rationale for choosing the 6 day infusion period is based on a pilot study performed measuring AA incorporation at 2, 3, 4, 6, 8, and 10 days of LPS infusion (data not shown). In this study we found no increase in total AA incorporation over control values until day 4 (10–15% increase) of infusion. The incorporation of AA reached a maximum at day 6 and remained elevated out to 10 days. Therefore to determine in the metabolism of DHA was altered similar to that found with AA these experiments were repeated using the 6 day infusion period to measure markers of brain DHA as outlined below. Surgery was performed following the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (NIH Publication No. 80-23). Alzet osmotic mini-pumps (Model 2002; 0.5 µl/h, Plastics One, Roanoke VA) were used to continuously deliver either artificial cerebrospinal fluid (aCSF, 140 mM NaCl, 3.0 mM KCl, 2.5 mM CaCl2, 1.0 mM MgCl2, 1.2 mM Na2PO4, pH 7.4) or LPS dissolved in aCSF (1.0 µg/ml) to the fourth ventricle of the rat, as described (Hauss-Wegrzyniak et al. 1998b). After 6 days of infusion, a 12 h fasted rat was anesthetized with 3% halothane (Halocarbon, River Edge, NJ) and polyethylene catheters (PE 50, Becton Dickinson, Sparks, MD) filled with sodium heparin (100 IU) were implanted into the right femoral artery and vein. The skin was closed and 1% Lidocaine was applied to the wound. The hindquarters of the rat were wrapped loosely in a fast-setting plaster body cast then the rat was taped to a wooden block. The rat was allowed to recover from anesthesia for 3–4 h, while body temperature was maintained at 36.5°C using a feedback-heating device (Yellow Springs Laboratories, Yellow Springs, OH) equipped with a rectal thermometer.

Intravenous infusion of [1-14C]DHA

The method, basis of tracer infusion, and a complete description of the kinetic analysis detailing the theory of steady-state analysis have been reported elsewhere (Rapoport 2001, Robinson et al. 1992, Washizaki et al. 1994, Rapoport 2008). With an infusion pump (Harvard Apparatus, South Natick, MA), an awake rat was infused intravenously for 6 min at a rate of 0.4 ml/min, with 2.0 ml isotonic saline containing 175 µCi/kg body wt [1-14C]DHA suspended in 0.06 mg bovine serum albumin. Arterial blood samples (200 µl) were collected at 0, 30, 60, 120, 180 240, and 360 sec during infusion to determine radioactivity and concentrations of non-esterified fatty acids in plasma. Six min after starting infusion, the rat was killed with sodium pentobarbital (i.v., 100 mg/kg body wt) and immediately subjected to head-focused high-energy microwave irradiation to stop brain metabolism (5.5 kW, 3.4 sec; Cober Electronics, Stamford, CT). Animals used for enzyme assays, which were not infused with tracer, were killed with sodium pentobarbital and their brains were removed then frozen on dry ice. All samples were stored at −80° C until analyzed. To avoid artifacts from the cannula implant (Ghirnikar et al. 1996), analyses were performed only on cortical and basal forebrain regions.

Brain and plasma lipid extraction and chromatography

Total lipids from microwaved brains were extracted using n-hexane/2-propanol (3:2, by vol.) in a glass Tenbroeck homogenizer (Radin 1981). Plasma lipids were extracted in chloroform/methanol (2:1, by vol.) and partitioned with 0.9 % KCl. The total plasma lipids in the chloroform extract were washed once with 0.2 volumes of 0.9 % KCl to remove non-lipid contaminates prior to analysis (Folch et al. 1957). Standards and lipid extracts in chloroform were applied to Whatman silica gel 60A LK6 TLC plates and separated using chloroform/methanol/acetic acid/H2O (50:37.5:3:2, by vol.) (Jolly et al. 1997). Bands corresponding to ethanolamine and choline glycerophospholipid, phosphatidylinositol, or phosphatidylserine were scraped from the TLC plates. The plasmenylethanolamine and plasmenylcholine fractions were isolated from the ethanolamine and choline glycerophospholipid fractions as described (Murphy et al. 1993, Rosenberger et al. 2004). Neutral lipids were separated on silica gel 60 plates using the solvent system of heptane/diethyl ether/acetic acid (60:40:4, by vol.) (Breckenridge & Kuksis 1968). Gas chromatography was used to quantify esterified and non-esterified fatty acid levels. Liquid scintillation counting was used to measure radioactivity. Extracts were stored in n-hexane/2-propanol (3:2, by vol.) under N2 at −80° C.

Quantification of labeled and unlabeled brain acyl-CoA

Long-chain acyl-CoA species were isolated from microwaved rat brain using oligonucleotide purification cartridges (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) (Deutsch et al. 1994). Acyl-CoA concentrations and DHA-CoA radioactivity were measured using peak area analysis of chromatograms and liquid scintillation counting.

Methylation of esterified and non-esterified acids

Esterified fatty acids in the different phospholipid classes were methylated with 0.5 M methanolic potassium hydroxide at 37° C for 30 min. The reaction was stopped with methyl formate and the fatty acid methyl esters were extracted with n-hexane. The non-esterified brain fatty acids were methylated using 2 % sulfuric acid in toluene/methanol (1:1, by vol.) at 65° C for 4 h. The reaction was terminated with H2O and the fatty acid methyl esters were extracted with petroleum ether (Akesson et al. 1970).

Gas chromatography

Fatty acid methyl esters were quantified with a gas chromatograph (Trace 2000, ThermoFinnigan, Houston, TX) equipped with a flame ionization detector using a capillary column (SP 2330; 30 m × 0.32 mm i.d., Supelco, Bellefonte, PA). Sample runs were initiated at 90° C with a temperature gradient to 230° C over 20 min. Fatty acid methyl ester standards were used to establish relative retention times and response factors. The internal standard, methyl heptadecanoate, and the individual fatty acids were quantified by peak area analysis (ChromQuest, Ver. 4.0, ThermoFinnigan, Houston, TX). The detector response was linear, with correlation coefficients of 0.998 or greater within the sample concentration range for all standards.

Microsomal long-chain acyl-CoA synthetase preparation

Total and individual brain microsomal long-chain fatty acyl-CoA synthetase activity was measured in non-microwaved rat brains as described (Wilson et al. 1982, Saunders et al. 1996). A frozen whole brain was homogenized in 10 mM HEPES buffer (pH 7.4) containing 0.32 M sucrose, 20 µg/ml phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 1 mM benzamidine, 10 mM 2-mercaptoethanol, and 0.01 % soybean trypsin inhibitor. The homogenate was centrifuged at 1000 × g for 10 min at 4° C to remove cell debris and the microsomal membrane was isolated from the supernatant by centrifugation at 35,000 × g at 4° C for 1 hr. The microsomal pellet was re-suspended in 20 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) containing 1 % IGEPAL CA-630 detergent, 10 mM EDTA, and 10 mM 2-mercaptoethanol by vortexing at 4° C for 2 hr. Debris was removed by a second centrifugation at 35,000 × g at 4° C for 1 hr. A portion of the isolated microsomal fraction was removed to determine total microsomal long chain acyl-CoA synthetase activity. The remainder was partially purified on a 10-ml bed volume of Spectra/Gel HA hydroxyapatite (Spectrum, Los Angeles, CA) equilibrated with 20 mM potassium phosphate buffer, using a step gradient of 20 mM potassium phosphate, 80 mM potassium phosphate, and 300 mM potassium phosphate (Laposata et al. 1985). All chromatography buffers had a pH of 7.4 and contained 1 % IGEPAL CA-630 detergent and 10 mM 2-mercaptoethanol. The column eluate was collected in 1.75 ml fractions and each was assayed for enzyme activity. The protein content in total microsomal and column fractions, corresponding to the non-specific and AA-specific long-chain acyl-CoA synthetases, was measured by the method of Bradford (Bradford 1976).

Assay of microsomal long chain acyl-CoA synthetase activity

Total fatty acyl-CoA synthetase activity was measured in isolated microsomal fractions as described (Wilson et al. 1982, Saunders et al. 1996). A 50 µl aliquot of microsomal preparation or enzyme blank (re-suspension buffer) was added to 100 µl of an assay cocktail having a final concentration of 100 mM Tris/HCl (pH 8.0), 2 mM Triton X-100, 0.55 mM CoA, 6.6 mM ATP, 2.5 mM MgCl2, and 12 µM of [1-14C]AA or [1-14C]DHA. The reactions were allowed to proceed for 10 min at 37° C, then were terminated by the addition of 2.25 ml of 2-propanol/n-heptane/2 M H2SO4 (40:10:1, by vol.). Non-esterified substrate was removed from the reaction mixture by extracting with 1.5 ml n-heptane and 1 ml water. The aqueous layer was re-extracted twice with 2 ml n-heptane containing 4 mg/ml palmitic acid. Radioactivity in a 1-ml portion of the aqueous layer was determined by liquid scintillation counting. Initial rates of reaction normalized to the enzyme blanks were calculated based on the specific radioactivity of the substrate and reported in the units of nmol/(min × g protein).

Calculations

Radioactivity of a brain phospholipid i of interest, (T) nCi/g, was calculated by correcting its net brain radioactivity for its intravascular radioactivity (Grange et al. 1995). Blood samples taken at the time of death, T = 6 min after starting tracer infusion, were extracted and analyzed to make this correction. Unidirectional incorporation coefficients, ml/(g × sec), of [1-14C]DHA from plasma into phospholipids i were calculated as follows,

| (Eq. 1) |

where t is time after beginning of infusion, and (nCi/ml) is the plasma concentration of radiolabeled DHA during infusion. Rates of incorporation of non-esterified DHA from plasma into brain phospholipid i, J in,i, and from the brain docosahexaenoyl-CoA pool into brain phospholipid i, J FA,i, were calculated as follows,

| (Eq. 2) |

| (Eq. 3) |

cpl (nmol/ml) is the concentration of unlabeled non-esterified DHA in plasma. λacyl-CoA represents the steady-state specific activity of docosahexaenoyl-CoA relative to that of plasma during [1-14C]DHA infusion,

| (Eq. 4) |

where the numerator is the specific activity of brain docosahexaenoyl-CoA and the denominator is the specific activity of plasma non-esterified DHA. The fractional turnover rate of DHA within phospholipid i, F FA, i (%/h), is defined as,

| (Eq. 5) |

Data and statistics

Integrals of plasma radioactivity were determined by trapezoidal integration (SigmaPlot, SPSS Science, Chicago, IL). Unpaired t-tests with a two-tail p value (Instat® Ver. 3.05, GraphPad, San Diego, CA) were used to compare means between LPS-infused and control aCSF-infused rats, where statistical significance was taken as p ≤ 0.05. Data are presented as means ± SD.

Results

Plasma and brain lipid concentrations

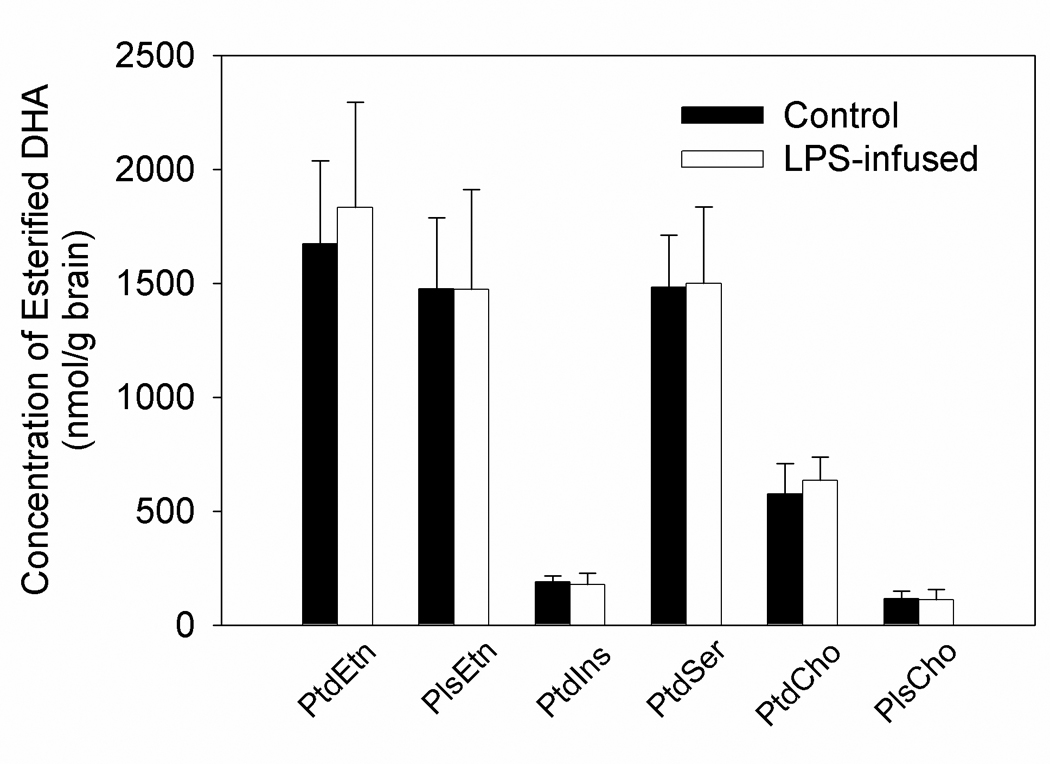

To begin to determine the effect that LPS infusion has on brain DHA metabolism we measured the plasma and brain non-esterified fatty acid, brain acyl-CoA, and esterified brain fatty acid levels in control and LPS treated rats. We found that there were no statistically significant differences in the mean plasma concentration of any non-esterified fatty acid between control LPS-treated rats (Table 1). Additionally, the net mean brain long-chain acyl-CoA concentrations did not differ significantly between groups. As previously reported (Rosenberger et al. 2004), the 6-day LPS infusion significantly increased the concentration of non-esterified brain AA, whereas concentrations of the other non-esterified brain fatty acids, including DHA, were unchanged (Table 1). Further, there was no difference in the concentration of esterified DHA in any phospholipid class between groups (Figure 1). This data suggests that LPS infusion did not change basic parameters of DHA metabolism in that treatment did not result in a net change in brain or plasma DHA. The concentrations of non-esterified and esterified DHA found in these studies are comparable to those previously published (Contreras et al. 2001, Rosenberger et al. 2004).

Table 1.

Concentration of plasma and brain non-esterified fatty acids, and brain acyl-CoA in control and LPS-treated rats

| Plasma Non-esterified Fatty Acid (nmol/ml) |

Brain Non-esterified Fatty Acid (nmol/g) |

Brain Acyl-CoA (nmol/g) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fatty Acid | Control | LPS | Control | LPS | Control | LPS |

| Palmitate (16:0) |

266.1 ± 95.6 | 283.1 ± 53.7 | 25.9 ± 10.3 | 26.8 ± 5.7 | 29.0 ± 6.7 | 34.6 ± 10.0 |

| Stearate (18:0) |

72.2 ± 42.6 | 81.0 ± 21.3 | 77.7 ± 12.3 | 60.9 ± 17.7 | 5.0 ± 3.8 | 8.4 ± 4.7 |

| Oleate (18:1n-9) |

221.4 ± 82.8 | 214.3 ± 51.0 | 62.0 ± 10.1 | 65.2 ± 9.1 | 27.6 ± 8.0 | 30.4 ± 8.7 |

| Linoleate (18:2n-6) |

277.2 ± 62.6 | 296.3 ± 77.3 | 6.2 ± 2.7 | 8.3 ± 3.0 | 10.4 ± 3.0 | 14.3 ± 10.2 |

| Arachidonate (20:4n-6) |

20.9 ± 7.3 | 26.2 ± 7.0 | 4.6 ± 0.5 | *15.8 ± 5.4 | 1.8 ± 0.8 | 1.3 ± 1.0 |

| Docosahexaenoate (22:6n-3) |

9.4 ± 4.6 | 9.1 ± 3.9 | 4.2 ± 0.8 | 5.3 ± 1.2 | 1.5 ± 0.8 | 2.1 ± 0.7 |

Values are means ± SD (n = 7).

p < 0.05, differs from control mean.

Figure 1.

Concentration of esterified DHA in the stable brain phospholipid pools from control and LPS-treated rats following an intravenous infusion of [1-14C]DHA. Values are the means ± SD (n=7). Abbreviations are: DHA, docosahexaenoic acid; PtdEtn, phosphatidylethanolamine; PlsEtn, plasmenylethanolamine; PtdIns, phosphatidylinositol; PtdSer, phosphatidylserine; PtdCho, phosphatidylcholine; PlsCho, plasmenylcholine.

DHA incorporation and turnover rates in individual brain phospholipids

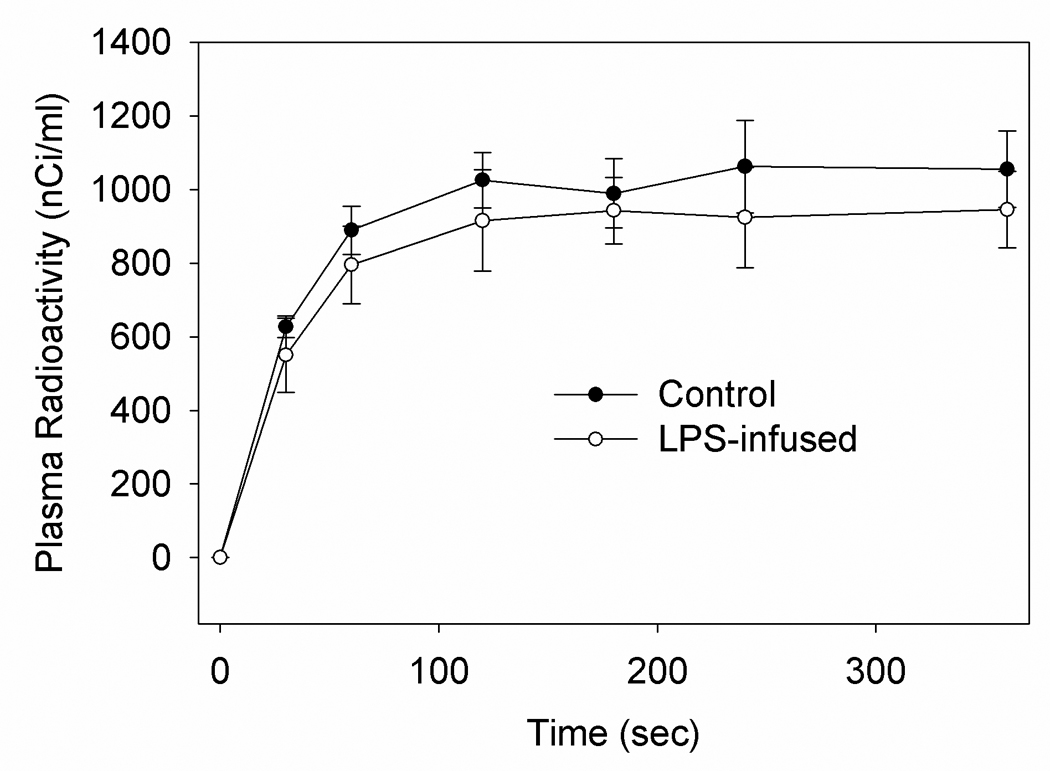

Because a lack of changes in the concentration of DHA do not necessarily reflect changes in brain DHA metabolism we measured the incorporation and turnover rate using steady-state radiotracer kinetic analysis. This is not without precedence because in both the LPS-treated rat and the α-synuclein knockout mouse where brain esterified AA concentrations are not changed there is a profound and significant alteration in the incorporation and turnover rates of AA (Golovko et al. 2006). To begin this analysis we found that the mean arterial plasma radioactivity profiles during intravenous infusion of [1-14C]DHA did not differ between control and LPS-treated rats (Figure 2). Further, a steady-state plasma radioactivity was achieved after 120 s following the start of intravenous [1-14C]DHA infusion in both groups and the mean steady-state plasma integrals equal between the two groups being 338,650 ± 29,570 and 303,682 ± 39,624 (nCi x s)/ml, respectively. Because the dilution factor λacyl-CoA (Eq. 4) for docosahexaenoyl-CoA in the two groups did not differ significantly and equaled 0.027 ± 0.005 and 0.031 ± 0.006, respectively suggests that LPS-treatment did not alter the delivery or activation of DHA into the brain.

Figure 2.

Plasma radioactivity in control and LPS-treated rats during the intravenous infusion of [1-14C]DHA. Values represent the means ± SD (n=7).

To expand on this analysis we calculated the rates of incorporation and turnover of DHA in control and LPS-treated rats by applying incorporation kinetic analysis. Table 2 shows that LPS infusion did not significantly alter the calculated incorporation coefficients (Eq. 1) of DHA from plasma into any brain stable phospholipid i. This is in contrast to our report that the total incorporation coefficient (k*) of AA was increased by 40% following a 6-day LPS infusion (Rosenberger et al. 2004). Because the derived parameters for each phospholipid were calculated by multiplying k* by common constant factors with no significant changes in the cold concentrations of esterified DHA (Eqs. 1-6), the same pattern was found for the rates of incorporation of unlabeled DHA from the precursor DHA-CoA pool into phospholipids, given as JFA,i (Eq. 3), and for the fractional turnover FFA,i of DHA in the phospholipids (Eq. 5). Therefore, despite an increase in the phospholipase activity (Rosenberger et al. 2004; Basselin et al. 2007) and the subsequent increase in the turnover rates of brain AA (Rosenberger et al. 2004) found in this model the kinetic of DHA metabolism remain unaltered.

Table 2.

Incorporation coefficients (), net incorporation rates from brain docosahexaenoyl-CoA (JFA,i), and fractional turnover rates (FFA,i) of DHA in different rain phospholipid pools in control and LPS-treated rats

| Incorporation Coefficient | Incorporation Rate | Fractions Turnover Rate | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (ml/g × s, ×10−5) | JFA,i (nmol/g × s, × 10−3) | FFA, i (%/h) | ||||

| Phospholipid | Control | LPS | Control | LPS | Control | LPS |

| PtdEtn | 4.5 ± 1.3 | 4.9 ± 0.6 | 14.2 ± 4.0 | 14.9 ± 1.8 | 3.5 ± 1.0 | 3.6 ± 0.5 |

| PlsEtn | 1.1 ± 0.4 | 1.4 ± 0.9 | 3.5 ± 1.3 | 4.3 ± 2.7 | 0.9 ± 0.3 | 1.1 ± 0.7 |

| PtdIns | 2.7 ± 0.6 | 2.5 ± 0.7 | 8.6 ± 1.8 | 7.7 ± 2.1 | 16.3 ± 3.5 | 14.7 ± 3.9 |

| PtdSer | 1.5 ± 0.5 | 1.3 ± 0.4 | 4.7 ± 1.6 | 4.0 ± 1.3 | 1.1 ± 0.4 | 1.0 ± 0.3 |

| PtdCho | 4.4 ± 1.2 | 4.5 ± 0.9 | 13.8 ± 3.9 | 13.5 ± 2.6 | 8.6 ± 2.4 | 8.4 ± 1.6 |

| PlsCho | 0.7 ± 0.3 | 0.5 ± 0.2 | 2.0 ± 0.9 | 1.6 ± 0.5 | 6.4 ± 2.9 | 5.2 ± 1.5 |

Values are means ± SD (n = 7).

Abbreviations: PtdEtn, phosphatidylethanolamine; PlsEtn, plasmenylethanolamine; PtdIns, phosphatidylinositol; PtdSer, phosphatidylserine; PtdCho, phosphatidylcholine; PlsCho, plasmenylcholine.

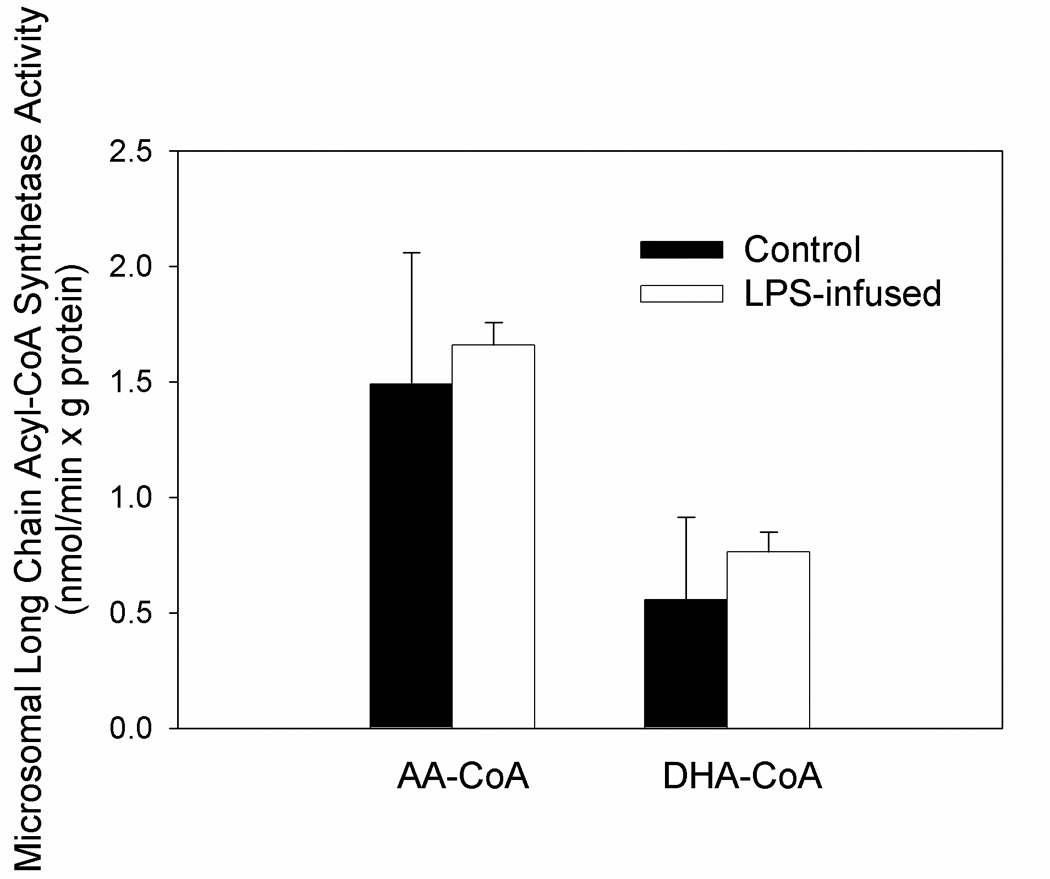

Microsomal long-chain acyl-CoA synthetase activity

To further examine if the increased metabolism of AA and not DHA in this model were due solely to increases in the activities of AA-selective PLA2 we measured the total acyl-CoA synthetase activity using labeled AA and DHA. Total long chain acyl-CoA synthetase activities from isolated brain microsomes were generated by assaying for acyl-CoA synthetase in the presence of 12 µM [1-14C]AA or [1-14C]DHA, as described in the Methods Section. The rates of conversion of AA or DHA to their respective CoA derivatives did not differ significantly between LPS-infused and control samples (Figure 3). The averaged microsomal long chain acyl-CoA synthetase activities toward AA and DHA were 1.5 ± 0.6 and 0.6 ± 0.2 nmol/(min × g protein), respectively, and were similar to previously reported values (Saunders et al. 1996). The acyl-CoA synthetase activity from fractions corresponding to the non-specific and AA-specific microsomal long-chain acyl-CoA synthetases (Wilson et al. 1982, Saunders et al. 1996) also did not differ between control and LPS-treated rat brain (data not shown), suggesting that LPS infusion did not alter the activity or expression of microsomal long-chain acyl-CoA synthetases. These data suggests that the LPS-induced increases in brain AA but not DHA metabolism are due primarily to increases in the activity of AA-selective PLA2, which confirms our previous studies.

Figure 3.

Brain microsomal long-chain acyl-CoA synthetase activity using [14C]AA or [14C]DHA as substrate from control or LPS-treated rats. Values are the means ± SD (n=5). Abbreviations are; AA-CoA, arachidonoyl-CoA and DHA-CoA, docosahexaenoyl-CoA.

Discussion

Despite marked increases in regional incorporation (Lee et al. 2004, Basselin et al. 2007) and fractional turnover rates (Rosenberger et al. 2004) of brain AA after 6 days of LPS infusion, no significant difference was found with regard to the brain metabolism of DHA. Further, the microsomal conversion rates of both AA and DHA to their respective acyl-CoA derivatives also were not changed, suggesting that LPS infusion did not alter the activity or expression patterns of those enzymes involved in the activation of these fatty acids. LPS infusion did increase the concentration of brain non-esterified AA (Table 1), confirming our prior results (Rosenberger et al. 2004). That no change was found in the incorporation and turnover rates of DHA or in the rates of acyl-CoA formation further supports the premise that enzymes regulating brain AA metabolism differ from those regulating brain DHA metabolism.

Selective alterations in the incorporation and turnover rates of brain AA and DHA have been reported in rats treated chronically with lithium (Calabrese & Woyshville 1995, Calabrese et al. 1995), and in rats subject to chronic nutritional n-3 fatty acid deprivation (Greiner et al. 2001). Chronic treatment of rats with lithium chloride, to produce therapeutically relevant concentrations of plasma and brain lithium (Bosetti et al. 2002), reduced the incorporation and turnover rates of brain AA by 80% (Chang et al. 1996) with no effect on brain DHA (Chang et al. 1999). This selective decrease of brain AA metabolism by lithium has been attributed to a reduction in the activity and expression of the AA-selective type IVA cPLA2 (Rintala et al. 1999). Lithium also reduces the activity and expression of COX-2 resulting in reduced brain prostaglandin levels (Bosetti et al. 2002). Similarly lithium treatment does not alter brain iPLA2 or sPLA2 activity or expression (Weerasinghe et al. 2004). In astrocytes DHA release is mediated in large part by the stimulation of type VI iPLA2, and can be reduced by a selective iPLA2 inhibitor, 4-bromoenol lactone (Strokin et al. 2003), with only a minimal effect on AA release (Ackermann et al. 1995). On the other hand, AA release can be selectively and completely blocked with methyl arachidonoyl fluorophosphonate, a general inhibitor of both cPLA2 and iPLA2 (Riendeau et al. 1994). Therefore the selective decrease in AA turnover found with lithium treatment is likely due to a selective decrease in brain cPLA2 activity and expression. Therefore, it is not unreasonable that the positive effect of LPS infusion on brain AA, but not DHA metabolism, reflects selective activation of AA-selective cPLA2-mediated signaling.

Further, chronic nutritional deprivation of n-3 fatty acids, which reduces the incorporation and turnover rates of DHA into brain phospholipids by 30–70% (Contreras et al. 2000) does not affect the incorporation or turnover of AA within brain phospholipids (Contreras et al. 2001). Our results showing that cPLA2 activity and brain AA metabolism (Rosenberger et al. 2004, Basselin et al. 2007) are increased in LPS infused rats, with no significant effect on DHA metabolism, are consistent with this idea and support the premise that an increase in AA metabolism following LPS infusion is due to an increase in AA-selective brain cPLA2. cPLA2 is calcium dependent and hydrolyzes AA in preference to other fatty acids esterified at the sn-2 position of the phospholipid moiety (Dennis 1994, Clark et al. 1995) (Kramer & Sharp 1997). In contrast, the brain activity of calcium-independent iPLA2 was unchanged by LPS infusion (Rosenberger et al. 2004). Collectively, these data support the idea that different brain PLA2 isoforms mediate the release of AA and DHA independently, with Group VI iPLA2 being responsible for DHA release and group IV cPLA2 for AA release (Strokin et al. 2003, Strokin et al. 2004).

In brain, fatty acid incorporation into lipids is initiated by acyl-CoA synthetases that catalyze the formation of acyl-CoA from fatty acid, ATP, and CoA (Watkins 1997, Waku 1992) making transport of fatty acid into the cell unidirectional (Lewin et al. 2001). To date, seven acyl-CoA synthetases having different cDNA have been cloned, each the product of a different gene (Coleman et al. 2002, Uberti et al. 2003, Tang et al. 2001). The different acyl-CoA synthetases, which differ in their tissue distribution and transcriptional regulation, can impart fatty acid selectivity (Marszalek et al. 2005) (Coleman et al. 2002). In this regard, acyl-CoA synthetase-2 and -3 preferentially convert long chain polyunsaturated fatty acids to their CoA derivates when compared to acyl-CoA synthetase-1 (Iijima et al. 1996, Fujino et al. 1996), whereas acyl-CoA synthetase-2 preferentially promotes DHA metabolism (Marszalek et al. 2005). Modulation in the activity of brain long chain acyl-CoA synthetases by α-synuclein have been found to disrupt the incorporation and turnover rates of brain fatty acids in the knockout mouse (Golovko et al. 2006). The lack of a significant change in the rates of AA-CoA or DHA-CoA formation in LPS infused rats found in this study further supports the principle that selective changes in the incorporation and turnover of AA found in this model reflect primarily increased cPLA2.

Microglia and astrocytes respond to inflammatory stimuli by producing pro-inflammatory cytokines that initiate a cascade of biochemical and molecular events that propagate the inflammatory response. These changes stimulate PLA2 (Farooqui et al. 1997) and increase the production of prostaglandins by the coordinated action of PLA2 with COX-1 and COX-2 (Hernandez et al. 1999). Following injury and in response to intracellular Ca2+, type IVA cPLA2 is functionally coupled to COX-2 and co-localized to the nucleus (Scott et al. 1999, Sandhya et al. 1998, Evans et al. 2001). The activation and co-localization of these enzymes can have a propagating influence on other brain PLA2 enzymes, as non-esterified AA and the formation of prostaglandins can result in a feedback loop that stimulates the activation of types IIA and V secretory PLA2, and increases the production of membrane-derived inflammatory mediators (Bazan et al. 2002). Therefore, LPS-mediated activation of cPLA2 and the subsequent conversion of AA to prostaglandins can have both an immediate response as well as a propagating influence on inflammation-induced neurodegeneration. The presence of activated cPLA2 and increased brain concentrations of PGE2 and PGD2 found in the LPS model (Rosenberger et al. 2004) are consistent with the propagating potential of cPLA2 in the neuroinflammatory response.

Since excess PLA2 activation is associated with membrane breakdown, mitochondrial dysfunction, and impaired ATP synthesis (Bonventre 1997), sustained PLA2 activation may lead to failure of excitable membranes and result in loss of membrane stability and cell death. Collectively, these studies suggest that chronic inflammatory events may lead to the selective disruption in the turnover of brain AA resulting in a loss of membrane homeostasis. Thus, the increase in PLA2 activity, increased conversion of AA due to prostaglandins, and disruption in AA recycling under sustained neuroinflammatory conditions may lead to the loss of membrane phospholipid and result in cell death. Therefore, targeting PLA2-mediated signaling in response to a neuroinflammatory insult may be beneficial in attenuating the temporal progression of degenerative events associated with inflammation.

In conclusion, the absence of changes in markers of brain DHA metabolism in rats subjected to a 6-day intracerebral ventricular infusion of LPS is in marked contrast to studies showing upregulated markers of AA metabolism (Rosenberger et al. 2004, Lee et al. 2004, Basselin et al. 2007). The lack of a change of brain iPLA2 with no significant change in the rate of microsomal acyl-CoA synthetase activity or in the rate DHA incorporation or turnover, suggests that these DHA-related pathways are not altered following LPS-treatment. Therefore, targeting the AA cascade, particularly cPLA2-mediated events, during neuroinflammation may provide a useful therapeutic tool to attenuate the degenerative events associated with neuroinflammation.

Acknowledgment

This work was supported by the Intramural Program of the National Institute on Aging, National Institutes of Health.

Abbreviations

- AA

arachidonic acid

- DHA

docosahexaenoic acid

- LPS

lipopolysaccharide

- PLA2

phospholipases A2

- cPLA2

cytosolic phospholipase A2

- sPLA2

secretory phospholipase A2

- iPLA2

calcium-independent PLA2

- PUFA

polyunsaturated fatty acids

- AA-CoA

arachidonoyl-CoA

- DHA-CoA

docosahexaenoyl-CoA

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Literature Cited

- Ackermann EJ, Conde-Frieboes K, Dennis EA. Inhibition of macrophage Ca2+-independent phospholipase A2 by bromoenol lactone and trifluoromethyl ketones. J. Biol. Chem. 1995;270:445–450. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.1.445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akesson B, Elovson J, Arvidson G. Initial incorporation into rat liver glycerolipids of intraportally injected (3H)glycerol. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1970;210:15–27. doi: 10.1016/0005-2760(70)90057-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ansell GB. Phospholipids and the nervous system. In: Ansell GB, Hawthorne JN, Dawson RMC, editors. Form and Function of Phospholipids. Vol. 3. New York: Elsevier; 1973. pp. 377–422. [Google Scholar]

- Arvindakshan M, Sitasawad S, Debsikdar V, Ghate M, Evans D, Horrobin DF, Bennett C, Ranjekar PK, Mahadik SP. Essential polyunsaturated fatty acid and lipid peroxide levels in never-medicated and medicated schizophrenia patients. Biol. Psychiatry. 2003;53:56–64. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(02)01443-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barcelo-Coblijn G, Kitajka K, Puskas LG, Hogyes E, Zvara A, Hackler L, Jr, Farkas T. Gene expression and molecular composition of phospholipids in rat brain in relation to dietary n-6 to n-3 fatty acid ratio. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2003;1632:72–79. doi: 10.1016/s1388-1981(03)00064-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basselin M, Villacreses NE, Lee HJ, Bell JM, Rapoport SI. Chronic lithium administration attenuates up-regulated brain arachidonic acid metabolism in a rat model of neuroinflammation. J. Neurochem. 2007;102:761–772. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.04593.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bazan NG, Colangelo V, Lukiw WJ. Prostaglandins and other lipid mediators in Alzheimer's disease. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat. 2002;68–69:197–210. doi: 10.1016/s0090-6980(02)00031-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonventre JV. Roles of phospholipases A2 in brain cell and tissue injury associated with ischemia and excitotoxicity. J. Lipid Mediat. Cell Signal. 1997;17:71–79. doi: 10.1016/s0929-7855(97)00021-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosetti F, Rintala J, Seemann R, Rosenberger TA, Contreras MA, Rapoport SI, Chang MC. Chronic lithium downregulates cyclooxygenase-2 activity and prostaglandin E2 concentration in rat brain. Mol. Psychiatry. 2002;7:845–850. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradford MM. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 1976;72:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breckenridge WC, Kuksis A. Specific distribution of short-chain fatty acids in molecular distillates of bovine milk fat. J. Lipid Res. 1968;9:388–393. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calabrese JR, Bowden C, Woyshville MJ. Lithium and the anticonvulsants in the treatment of bipolar disorder. In: Bloom E, Kupfer D, editors. Phychopharmacology: The Fourth Generation of Progress. New York: Raven; 1995. pp. 1099–1111. [Google Scholar]

- Calabrese JR, Woyshville MJ. Lithium therapy: limitations and alternatives in the treatment of bipolar disorders. Ann. Clin. Psychiatry. 1995;7:103–112. doi: 10.3109/10401239509149036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang MC, Bell JM, Purdon AD, Chikhale EG, Grange E. Dynamics of docosahexaenoic acid metabolism in the central nervous system: lack of effect of chronic lithium treatment. Neurochem. Res. 1999;24:399–406. doi: 10.1023/a:1020989701330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang MC, Grange E, Rabin O, Bell JM, Allen DD, Rapoport SI. Lithium decreases turnover of arachidonate in several brain phospholipids. Neurosci. Lett. 1996;220:171–174. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(96)13264-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark JD, Schievella AR, Nalefski EA, Lin LL. Cytosolic phospholipase A2. J. Lipid Mediat. Cell Signal. 1995;12:83–117. doi: 10.1016/0929-7855(95)00012-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman RA, Lewin TM, Van Horn CG, Gonzalez-Baro MR. Do long-chain acyl-CoA synthetases regulate fatty acid entry into synthetic versus degradative pathways? J. Nutr. 2002;132:2123–2126. doi: 10.1093/jn/132.8.2123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Contreras MA, Chang MC, Rosenberger TA, Greiner RS, Myers CS, Salem N, Jr, Rapoport SI. Chronic nutritional deprivation of n-3 alpha-linolenic acid does not affect n-6 arachidonic acid recycling within brain phospholipids of awake rats. J. Neurochem. 2001;79:1090–1099. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2001.00658.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Contreras MA, Greiner RS, Chang MC, Myers CS, Salem N, Rapoport SI. Nutritional deprivation of alpha-linolenic acid decreases but does not abolish turnover and availability of unacylated docosahexaenoic acid and docosahexaenoyl-CoA in rat brain. J. Neurochem. 2000;75:2392–2400. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2000.0752392.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crawford MA, Golfetto I, Ghebremeskel K, Min Y, Moodley T, Poston L, Phylactos A, Cunnane S, Schmidt W. The potential role for arachidonic and docosahexaenoic acids in protection against some central nervous system injuries in preterm infants. Lipids. 2003;38:303–315. doi: 10.1007/s11745-003-1065-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennis EA. Diversity of group types, regulation, and function of phospholipase A2. J. Biol. Chem. 1994;269:13057–13060. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deutsch J, Grange E, Rapoport SI, Purdon AD. Isolation and quantitation of long-chain acyl-coenzyme A esters in brain tissue by solid-phase extraction. Anal. Biochem. 1994;220:321–323. doi: 10.1006/abio.1994.1344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinarello CA. The IL-1 family and inflammatory diseases. Clinical and experimental rheumatology. 2002;20:S1–S13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans JH, Spencer DM, Zweifach A, Leslie CC. Intracellular calcium signals regulating cytosolic phospholipase A2 translocation to internal membranes. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:30150–30160. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M100943200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farooqui AA, Yang HC, Rosenberger TA, Horrocks LA. Phospholipase A2 and its role in brain tissue. J. Neurochem. 1997;69:889–901. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1997.69030889.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flower R, Gryglewski R, Herbaczynska-Cedro K, Vane JR. Effects of anti-inflammatory drugs on prostaglandin biosynthesis. Nat. New Biol. 1972;238:104–106. doi: 10.1038/newbio238104a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folch J, Lees M, Sloane Stanley GH. A simple method for the isolation and purification of total lipides from animal tissue. J. Biol. Chem. 1957;226:497–509. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujino T, Kang MJ, Suzuki H, Iijima H, Yamamoto T. Molecular characterization and expression of rat acyl-CoA synthetase 3. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:16748–16752. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.28.16748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghirnikar RS, Lee YL, He TR, Eng LF. Chemokine expression in rat stab wound brain injury. J. Neurosci. Res. 1996;46:727–733. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4547(19961215)46:6<727::AID-JNR9>3.0.CO;2-H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golovko MY, Rosenberger TA, Faergeman NJ, Feddersen S, Cole NB, Pribill I, Berger J, Nussbaum RL, Murphy EJ. Acyl-CoA synthetase activity links wild-type but not mutant alpha-synuclein to brain arachidonate metabolism. Biochemistry. 2006;45:6956–6966. doi: 10.1021/bi0600289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grange E, Deutsch J, Smith QR, Chang M, Rapoport SI, Purdon AD. Specific activity of brain palmitoyl-CoA pool provides rates of incorporation of palmitate in brain phospholipids in awake rats. J. Neurochem. 1995;65:2290–2298. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1995.65052290.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greiner RS, Moriguchi T, Slotnick BM, Hutton A, Salem N. Olfactory discrimination deficits in n-3 fatty acid-deficient rats. Physiol. Behav. 2001;72:379–385. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9384(00)00437-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hauss-Wegrzyniak B, Dobrzanski P, Stoehr JD, Wenk GL. Chronic neuroinflammation in rats reproduces components of the neurobiology of Alzheimer's disease. Brain Res. 1998a;780:294–303. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(97)01215-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hauss-Wegrzyniak B, Lukovic L, Bigaud M, Stoeckel ME. Brain inflammatory response induced by intracerebroventricular infusion of lipopolysaccharide: an immunohistochemical study. Brain Res. 1998b;794:211–224. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(98)00227-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez M, Bayon Y, Sanchez Crespo M, Nieto ML. Signaling mechanisms involved in the activation of arachidonic acid metabolism in human astrocytoma cells by tumor necrosis factor-alpha: phosphorylation of cytosolic phospholipase A2 and transactivation of cyclooxygenase-2. J. Neurochem. 1999;73:1641–1649. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1999.0731641.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong S, Gronert K, Devchand PR, Moussignac RL, Serhan CN. Novel docosatrienes and 17S-resolvins generated from docosahexaenoic acid in murine brain, human blood, and glial cells. Autacoids in anti-inflammation. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:14677–14687. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M300218200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iijima H, Fujino T, Minekura H, Suzuki H, Kang MJ, Yamamoto T. Biochemical studies of two rat acyl-CoA synthetases, ACS1 and ACS2. Eur. J. Biochem. 1996;242:186–190. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1996.0186r.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jolly CA, Hubbell T, Behnke WD, Schroeder F. Fatty acid binding protein: stimulation of microsomal phosphatidic acid formation. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1997;341:112–121. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1997.9957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer RM, Sharp JD. Structure, function and regulation of Ca2+-sensitive cytosolic phospholipase A2 (cPLA2) F.E.B.S. Lett. 1997;410:49–53. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)00322-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laposata M, Reich EL, Majerus PW. Arachidonoyl-CoA synthetase. Separation from nonspecific acyl-CoA synthetase and distribution in various cells and tissues. J. Biol. Chem. 1985;260:11016–11020. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee H, Villacreses NE, Rapoport SI, Rosenberger TA. In vivo imaging detects a transient increase in brain arachidonic acid metabolism: A potential marker of neuroinflammation. J. Neurochem. 2004;91:936–945. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02786.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewin TM, Kim JH, Granger DA, Vance JE, Coleman RA. Acyl-CoA synthetase isoforms 1, 4, and 5 are present in different subcellular membranes in rat liver and can be inhibited independently. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:24674–24679. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M102036200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luschen S, Adam D, Ussat S, Kreder D, Schneider-Brachert W, Kronke M, Adam-Klages S. Activation of ERK1/2 and cPLA2 by the p55 TNF receptor occurs independently of FAN. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2000;274:506–512. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.3173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcheselli VL, Hong S, Lukiw WJ, et al. Novel docosanoids inhibit brain ischemia-reperfusion-mediated leukocyte infiltration and pro-inflammatory gene expression. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:43807–43817. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M305841200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marszalek JR, Kitidis C, Dirusso CC, Lodish HF. Long-chain Acyl CoA synthetase 6 preferentially promotes DHA metabolism. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:10817–10826. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M411750200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy EJ, Stephens R, Jurkowitz-Alexander M, Horrocks LA. Acidic hydrolysis of plasmalogens followed by high-performance liquid chromatography. Lipids. 1993;28:565–568. doi: 10.1007/BF02536090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radin NS. Extraction of tissue lipids with a solvent of low toxicity. Methods Enzymol. 1981;72:5–7. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(81)72003-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rapoport SI. In vivo fatty acid incorporation into brain phospholipids in relation to plasma availability, signal transduction and membrane remodeling. J. Mol. Neurosci. 2001;16:243–261. doi: 10.1385/JMN:16:2-3:243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rapoport SI. Brain arachidonic and docosahexaenoic acid cascades are selectively altered by drugs, diet and disease. Prostaglandins Leukot. Essent. Fatty Acids. 2008;79:153–156. doi: 10.1016/j.plefa.2008.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riendeau D, Guay J, Weech PK, et al. Arachidonyl trifluoromethyl ketone, a potent inhibitor of 85-kDa phospholipase A2, blocks production of arachidonate and 12-hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid by calcium ionophore-challenged platelets. J. Biol. Chem. 1994;269:15619–15624. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rintala J, Seemann R, Chandrasekaran K, Rosenberger TA, Chang L, Contreras MA, Rapoport SI, Chang MC. 85 kDa cytosolic phospholipase A2 is a target for chronic lithium in rat brain. Neuroreport. 1999;10:3887–3890. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199912160-00030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson PJ, Noronha J, DeGeorge JJ, Freed LM, Nariai T, Rapoport SI. A quantitative method for measuring regional in vivo fatty-acid incorporation into and turnover within brain phospholipids: review and critical analysis. Brain Res. Brain Res. Rev. 1992;17:187–214. doi: 10.1016/0165-0173(92)90016-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberger TA, Villacreses NE, Hovda JT, Bosetti F, Weerasinghe G, Wine RN, Harry GJ, Rapoport SI. Rat brain arachidonic acid metabolism is increased by a six-day intracerebral ventricular infusion of bacterial lipopolysaccharide. J. Neurochem. 2004;88:1168–1178. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.02246.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosi S, Ramirez-Amaya V, Hauss-Wegrzyniak B, Wenk GL. Chronic brain inflammation leads to a decline in hippocampal NMDA-R1 receptors. J. Neuroinflammation. 2004;1:12. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-1-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandhya TL, Ong WY, Horrocks LA, Farooqui AA. A light and electron microscopic study of cytoplasmic phospholipase A2 and cyclooxygenase-2 in the hippocampus after kainate lesions. Brain Res. 1998;788:223–231. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(97)01552-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saunders C, Voigt JM, Weis MT. Evidence for a single non-arachidonic acid-specific fatty acyl-CoA synthetase in heart which is regulated by Mg2+ Biochem. J. 1996;313(Pt 3):849–853. doi: 10.1042/bj3130849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott KF, Bryant KJ, Bidgood MJ. Functional coupling and differential regulation of the phospholipase A2-cyclooxygenase pathways in inflammation. J. Leukoc. Biol. 1999;66:535–541. doi: 10.1002/jlb.66.4.535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sergeeva M, Strokin M, Wang H, Ubl JJ, Reiser G. Arachidonic acid and docosahexaenoic acid suppress thrombin-evoked Ca2+ response in rat astrocytes by endogenous arachidonic acid liberation. J. Neurochem. 2002;82:1252–1261. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2002.01052.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serhan CN, Hong S, Gronert K, Colgan SP, Devchand PR, Mirick G, Moussignac RL. Resolvins: a family of bioactive products of omega-3 fatty acid transformation circuits initiated by aspirin treatment that counter proinflammation signals. J. Exp. Med. 2002;196:1025–1037. doi: 10.1084/jem.20020760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimizu T, Wolfe LS. Arachidonic acid cascade and signal transduction. J. Neurochem. 1990;55:1–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1990.tb08813.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strokin M, Sergeeva M, Reiser G. Docosahexaenoic acid and arachidonic acid release in rat brain astrocytes is mediated by two separate isoforms of phospholipase A2 and is differently regulated by cyclic AMP and Ca2+ Br. J. Pharmacol. 2003;139:1014–1022. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strokin M, Sergeeva M, Reiser G. Role of Ca2+-independent phospholipase A2 and n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid docosahexaenoic acid in prostanoid production in brain: perspectives for protection in neuroinflammation. Int. J. Dev. Neurosci. 2004;22:551–557. doi: 10.1016/j.ijdevneu.2004.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang PZ, Tsai-Morris CH, Dufau ML. Cloning and characterization of ahormonally regulated rat long chain acyl-CoA synthetase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2001;98:6581–6586. doi: 10.1073/pnas.121046998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uberti MA, Pierce J, Weis MT. Molecular characterization of a rabbit long-chain fatty acyl CoA synthetase that is highly expressed in the vascular endothelium. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2003;1645:193–204. doi: 10.1016/s1570-9639(02)00540-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waku K. Origins and fates of fatty acyl-CoA esters. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1992;1124:101–111. doi: 10.1016/0005-2760(92)90085-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Washizaki K, Smith QR, Rapoport SI, Purdon AD. Brain arachidonic acid incorporation and precursor pool specific activity during intravenous infusion of unesterified [3H]arachidonate in the anesthetized rat. J. Neurochem. 1994;63:727–736. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1994.63020727.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watkins PA. Fatty acid activation. Prog. Lipid Res. 1997;36:55–83. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7827(97)00004-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weerasinghe GR, Rapoport SI, Bosetti F. The effect of chronic lithium on arachidonic acid release and metabolism in rat brain does not involve secretory phospholipase A2 or lipoxygenase/cytochrome P450 pathways. Brain Res. Bull. 2004;63:485–489. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2004.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wenk G, Hauss-Wegrzyniak B, Willard LB. Pathological and biochemical studies of chronic neuroinflammation may lead to therapies for Alzheimers's disease. In: Patterson PH, Kordon C, Christein Y, editors. Research and perspectives in neurosciences. Berlin: Springer-Verlag; 2000. pp. 73–77. [Google Scholar]

- Willard LB, Hauss-Wegrzyniak B, Wenk GL. Pathological and biochemical consequences of acute and chronic neuroinflammation within the basal forebrain cholinergic system of rats. Neuroscience. 1999;88:193–200. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(98)00216-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson DB, Prescott SM, Majerus PW. Discovery of an arachidonoyl coenzyme A synthetase in human platelets. J. Biol. Chem. 1982;257:3510–3515. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]