Abstract

Bacteria of the Thiomonas genus are ubiquitous in extreme environments, such as arsenic-rich acid mine drainage (AMD). The genome of one of these strains, Thiomonas sp. 3As, was sequenced, annotated, and examined, revealing specific adaptations allowing this bacterium to survive and grow in its highly toxic environment. In order to explore genomic diversity as well as genetic evolution in Thiomonas spp., a comparative genomic hybridization (CGH) approach was used on eight different strains of the Thiomonas genus, including five strains of the same species. Our results suggest that the Thiomonas genome has evolved through the gain or loss of genomic islands and that this evolution is influenced by the specific environmental conditions in which the strains live.

Author Summary

Recent advances in the field of arsenic microbial metabolism have revealed that bacteria colonize a large panel of highly contaminated environments. Belonging to the order of Burkholderiales, Thiomonas strains are ubiquitous in arsenic-contaminated environments. The genome of one of them, i.e. Thiomonas sp. 3As, was deciphered and compared to the genome of several other Thiomonas strains. We found that their flexible gene pool evolved to allow both the surviving and growth in their peculiar environment. In particular, the acquisition by strains of the same species of different genomic islands conferred heavy metal resistance and metabolic idiosyncrasies. Our comparative genomic analyses suggest that the natural environment influences the genomic evolution of these bacteria. Importantly, these results highlight the genomic variability that may exist inside a taxonomic group, enlarging the concept of bacterial species.

Introduction

In environments such as those impacted by acid mine drainage (AMD), high toxic element concentrations, low levels of organic matter and low pH make growth conditions extreme. AMD is generally characterized by elevated sulfate, iron and other metal concentrations, in particular, inorganic forms of arsenic such as arsenite (As(III)) and arsenate (As(V)) [1],[2]. While these waters are toxic to the majority of prokaryotic and eukaryotic organisms, a few Bacteria and Archaea are not only resistant to but also able to metabolize some of the toxic compounds present [1]. Members of the Thiomonas genus are frequently found in AMD and AMD-impacted environments, as Thiomonas sp. 3As and “Thiomonas arsenivorans” [2]–[6]. These Betaproteobacteria have been defined as facultative chemolithoautotrophs, which grow optimally in mixotrophic media containing reduced inorganic sulfur compounds (RISCs) and organic supplements. Some strains are capable of autotrophic growth and others are capable of organotrophic growth in the absence of any inorganic energy source [5],[7],[8]. Recently described species and isolates include “Tm. arsenivorans” [9], Tm. delicata [10], Thiomonas sp. 3As [5] and Ynys1 [11]. Thiomonas sp. 3As as well as other recently isolated strains from AMD draining the Carnoulès mine site (southeastern France) containing a high arsenic concentration (up to 350 mg L−1) [3],[12], present interesting physiological and metabolic capacities, in particular an ability to oxidize As(III).

Over the past few years an increasing number of genomes has been sequenced, revealing that bacterial species harbor a core genome containing essential genes and a dispensable genome carrying accessory genes [13]. Some of these accessory genes are found within genomic islands (GEIs) [14] and have been acquired by horizontal gene transfer (HGT). These GEIs are discrete DNA segments (from 10 to 200 kbp) characterized by nucleotide statistics (G+C content or codon usage) that differ from the rest of the genome, and are often inserted in tRNA or tRNA-like genes. Their boundaries are frequently determined by 16–20 bp (up to 130 bp) perfect or almost perfect direct repeats (DRs). These regions often harbor functional or cryptic genes encoding integrases or factors involved in plasmid conjugation or related to phages. GEIs encompass other categories of elements such as integrative and conjugative elements (ICE), conjugative transposons and cryptic or defective prophages. Such GEIs are self-mobile and play an important role in genome plasticity [14]. In almost all cases, GEIs have been detected in silico, by the comparison of closely related strains. Nevertheless, the role of GEIs in genome plasticity has also been experimentally demonstrated in several pathogenic bacteria such as Staphylococcus aureus or Yersinia pseudotuberculosis [15],[16] or in Pseudomonas sp. strain B13 isolated from a sewage treatment plant [17].

Deciphering dispensable genomes has revealed that the loss or gain of genomic islands may be important for bacterial evolution [18]. Indeed, these analyses allow the determination of the genome sequence, called pan-genome or supragenome, not just of individual bacteria, but also of entire species, genera or even bacterial kingdom [19],[20]. These data result in debates on taxonomic methods used to define the bacterial species [21],[22], e.g. pathogens such as Streptococcus agalactiae [21],[23] or environmental bacteria such as Prochlorococcus [24],[25] or Agrobacterium [26]. However, beyond these well-known and cultivable microorganisms, the diversity of bacteria, in particular those found in extreme environments, has hitherto been comparatively poorly studied. Genome analysis of such extremophiles may yet reveal interesting capacities since these bacteria may express unexpected and unusual enzymes [27]. Since the role of GEIs in extremophiles has not been yet well explored, little is known about their evolution.

In the present study, the genome of Thiomonas sp. 3As was sequenced and analyzed. It was next compared to the genome of other Thiomonas strains, either of the same species or of other species of the same genus. This genome exploration revealed that Thiomonas sp. 3As evolved to survive and grow in its particular extreme environment, probably through the acquisition of GEIs.

Results

General Features of the Thiomonas sp. 3As Genome

The genome of Thiomonas sp. 3As comprises a 3.7 Mbp circular chromosome and a 46.8 kbp plasmid (Table 1). The single circular chromosome contains 3,632 coding sequences (CDSs) (Table 1, Figure S1A). The mean G+C content of the Thiomonas sp. 3As genome is 63.8%. However, the distribution along the genome revealed several regions with a G+C content clearly divergent from this mean value (Figure S1). This suggests that several genomic regions are of exogenous origin. Indeed, 196 genes having mobile and extrachromosomal element functions were identified in the genome, among which a total of 91 ISs (Figure S1A, Table S1) representing 2.5% of total CDS. None of these ISs were found as part of composite transposons, while several were identified as neighbors of phage-like site-specific recombinases.

Table 1. General genome and plasmid features.

| Molecule | Category | Feature | Value |

| Plasmid | General characteristics | Size (bp) | 46,756 |

| GC content (%) | 60.49 | ||

| Coding density (%) | 88.19 | ||

| Predicted CDSs | 68 | ||

| Proteins with predicted function | Percent of total CDSs | 48.52 | |

| Secretion (%) | 11.76 | ||

| Partitioning | 2.94 | ||

| Replication, recombination | 8.82 | ||

| Inorganic ion transport and metabolism (Hg) | 2.94 | ||

| Proteins without predicted function | Conserved hypothetical proteins (%) | 13.24 | |

| No homology to any previously reported sequences (%) | 38.24 | ||

| Percent of total CDSs | 51.48 | ||

| Genome | General characteristics | Size (bp) | 3,738,778 |

| GC content (%) | 63.8 | ||

| Coding density (%) | 90.01 | ||

| 16S-23S-5S rRNA operons | 1 | ||

| tRNAs | 43 | ||

| Predicted CDSs | 3,632 | ||

| Proteins with predicted function | Percent of total CDSs | 74.2 | |

| Heavy metal resistance (%) | 1.6 | ||

| Related to arsenic metabolism/transport (%) | 0.6 | ||

| Proteins without predicted function | Conserved hypothetical proteins (%) | 13.54 | |

| Hypothetical proteins (%) | 11.95 | ||

| Percent of total CDSs | 25.8 | ||

| Mobile and extrachromosomal element functions | Percent of total CDSs | 5.4 | |

| Transposases (nb CDSs) | 101 | ||

| Phage related (nb CDSs) | 61 | ||

| Repeated regions (%) | 7.62 |

The plasmid, pTHI, contains 68 predicted CDS. 21 genes were found in synteny with genes carried by the R. eutropha JMP134 plasmid pJP4, and among them, par/trf/pem genes necessary for plasmid partitioning, stability and replication (Figure S1B). These observations suggest that pTHI, as JMP134, belongs to the IncP-1β group [28]. pTHI contains 13 of the 14 genes involved in conjugation (vir and tra genes) and genes that could fulfill the function of the missing components were found on the chromosome. Therefore, Thiomonas sp. 3As may be able to express a complete Type IV secretory system (T4SS) of the Vir/Tra type required for pTHI conjugal transfer. IncP-1β members are known to carry multi-resistance determinants and degradative cassettes [28], and plasmid pTHI indeed carries a Tn3-related transposon. This transposon contains part of a mercury resistance operon found in many other Gram negative bacterial transposon such as Tn21, Tn501 and Tn5053 [29].

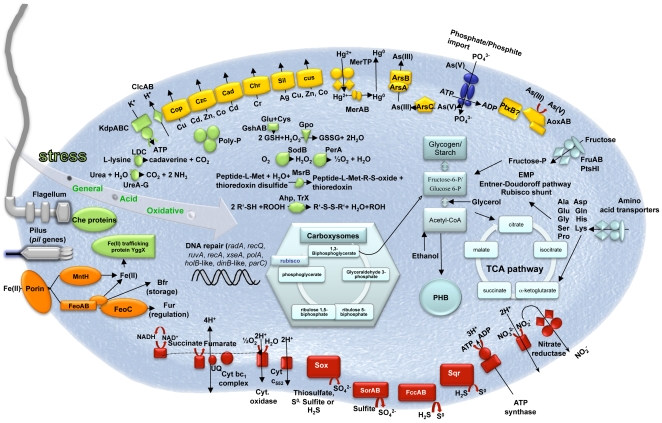

Carbon and Energy Metabolism

Thiomonas sp. 3As is able to use organic compounds as a carbon source or electron donor [5],[8]. However, under certain conditions this bacterium may also be able to grow autotrophically [5]. A complete set of cbb/rbc/cso genes involved in carbon fixation via the Calvin cycle, and genes involved in glycogen, starch and polyhydroxybutyrate (PHB) biosynthesis pathways were identified (Figure 1 and [5]). Fructose, glucose, several amino acid, C4-dicarboxylates, propionate, acetate, lactate, formate, ethanol and glycerol are potential carbon sources or electron donors, since genes involved in their import or degradation via the glycolysis, the Entner-Doudoroff, the TriCarboxylic Acid (TCA) or the “rubisco shunt” pathways are present in the genome. The presence of all genes involved in the oxidative phosphorylation pathway (Figure 1) suggests that Thiomonas sp. 3As has a respiratory metabolism. Moreover, since several genes coding for terminal oxidases (i.e. cbb 3, bd or aa 3) were found, this respiratory metabolism may occur over a wide range of oxygen tensions. Finally, the presence of a nitrate reductase and of several formate dehydrogenases suggests that Thiomonas sp. 3As is able to use nitrate anaerobically as an electron acceptor and formate as electron donor. In the absence of carbohydrates, Thiomonas sp. 3As is a chemolithotroph and may use reduced inorganic sulfur compounds (RISCs) as an electron donor [5]. The presence of soxRCDYZAXB, dsr, sorAB, sqr and fccAB genes revealed that Thiomonas can oxidize thiosulfate, sulfite, S0 or H2S to sulfate (Figure 1) [30],[31].

Figure 1. Schematic representation of the major metabolic pathways in Thiomonas sp. 3As.

These metabolic pathways were ascertained using genome and physiological data ([5], this study). Light blue, carbon metabolism; Red, oxidative phosphorylation; Green, stress response; Yellow, heavy metal resistance; Orange, iron metabolism; Dark blue, phosphate import (pst genes).

Adaptive Capacities of Thiomonas sp. 3As to Its Extreme Environment

Thiomonas sp. is a moderate acidophile. Its optimum pH is 5 but this bacterium can withstand to pH as low as 2.9 (Slyemi, Johnson and Bonnefoy, personal communication). Thiomonas sp. 3As pH homeostasis mechanisms may therefore be strictly controlled as previously described [32],[33]. First, genes encoding a potassium-transporting P type ATPase (kdpABC) are present in the Thiomonas sp. 3As genome. This ATPase could be involved in the generation of a positive internal potential produced by a greater influx of potassium ions than the outward flux of protons. Second, to strengthen the membrane, likely by lowering membrane proton conductance, Thiomonas sp. has cyclopropane fatty acids [5]. Accordingly, two putative cfa genes encoding cyclopropane fatty acid synthase have been detected. Third, cytoplasmic buffering can be mediated either by amino acid decarboxylation and/or by polyphosphate granules. Genes encoding decarboxylases for lysine (4 CDS), phosphatidyl serine and glycine are present on Thiomonas sp. 3As genome. Moreover, urea (formed from arginine by arginase) may be degraded by urease (ure genes) or urea carboxylase and allophanate hydrolase. Urease encoding genes are known to be involved in acid tolerance in Helicobacter pylori [34]. Protons may be captured during polyphosphate synthesis. Polyphosphate granules have indeed been observed in electron micrographs of thin sections of Thiomonas sp. 3As [5]. Genes involved in such mechanisms (ppk, pap, ppx) were found in 3As genome. Fourth, primary and secondary proton efflux transporters were predicted by genome sequence analysis, including four putative Na+/H+ exchangers and voltage gated channels for chloride involved in the extreme acid resistance response in E. coli (clcAB) [35]. Finally, the elimination of organic acids can lead to pH homeostasis. Some organic acid degradation pathways have been detected in Thiomonas sp. such as an acetyl-CoA synthetase-like. Moreover, formate oxidation was observed (Slyemi, Johnson and Bonnefoy, personal communication) and two formate dehydrogenases are encoded by the Thiomonas sp. 3As genome, these enzymes could convert acetate to acetyl-CoA and formate to CO2 and hydrogen, respectively.

The Carnoulès AMD contains a high concentration of heavy metals such as zinc or lead. To resist to heavy metals, bacteria usually develop several resistance mechanism including toxic compounds extrusion pumps [36] or biofilm synthesis [37]. Flagella are important for the first steps of biofilm formation and all genes involved in motility, twitching and chemotaxis, were found in its genome. Thiomonas sp. 3As is motile but, unlike H. arsenicoxydans, this motility was not affected by arsenic concentration (Table S2, [38]). Finally, Thiomonas sp. 3As is able to synthesize exopolysaccharides (Table S2), and one eps operon involved in their synthesis was identified in the genome, as well as two mdoDG clusters involved in glucan synthesis. Several genes conferring resistance to cadmium, zinc, silver, (cad, czc, and sil genes), chromium (chr genes), mercury (2 mer operons encoding both MerA reductase but no organomercury lyase MerB), copper (cop and cus genes) and tellurite (transporters THI_0898-0899) are likely involved in Thiomonas sp. 3As heavy metal resistance (Figure 1). Arsenic resistance in bacteria is partly due to the expression of ars genes, among which, arsC encodes an arsenate reductase, arsA and arsB encode an arsenite efflux pump, arsR encodes a transcriptional regulator [39]. Thiomonas sp. 3As is resistant to up to 50 mM As(V) and up to 6 mM As(III) (Table S2, [8]). The analysis of the Thiomonas sp. 3As genome revealed the presence of two copies of the ars operon, an arsRBC operon (ars1) and an arsRDABC operon (ars2). Thiomonas sp. 3As is able to oxidize As(III) to As(V) [5] and this metabolism involves the arsenite oxidase encoded by aoxAB genes [5] (Figure 1). It has been shown that arsenite is imported via the aquaglyceroporin GlpF in E. coli [40]. However, as in H. arsenicoxydans [38], no homologue of GlpF was identified in the Thiomonas sp. 3As genome, suggesting that As(III) is imported via an unknown component.

As(III) is known to induce DNA damage and oxidative stress [41],[42]. 24 genes involved in such stress responses were identified in the Thiomonas sp. 3As genome (Figure 1). Moreover, this genome carries 54 genes involved in DNA repair. However, this strain lacks some genes present in H. arsenicoxydans, such as alkB, whereas two genes involved in mismatch repair were duplicated. Orthologs of genes that have been shown to be induced in response to arsenic in H. arsenicoxydans [38] were found in Thiomonas sp. 3As, i.e. radA, recQ, ruvA, recA, xseA, polA, holB-like, dinB-like and parC. The expression of polA has been previously shown to be induced in the presence of arsenic [8], suggesting that the Thiomonas sp. 3As response to arsenic include the expression of genes involved in DNA repair.

Comparative Genomic Analyses Allowed the Definition of 19 Genomic Islands (GEIs)

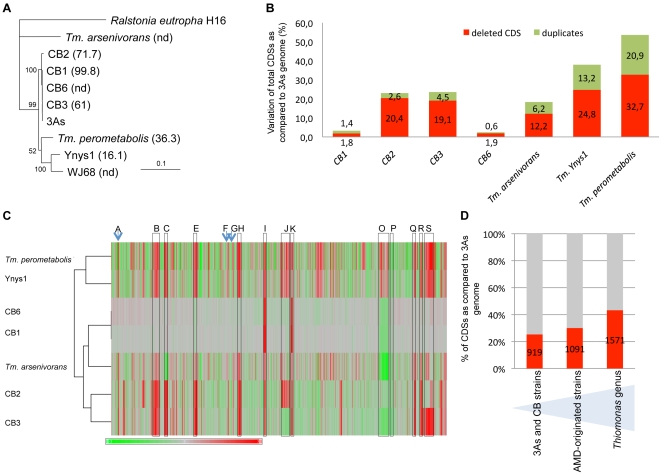

Several Thiomonas strains called CB1, CB2, CB3 and CB6 were isolated from the same environmental site as Thiomonas sp. 3As. The 16S rRNA/rpoA-based phylogeny of these isolates (>97% nucleotide identity), as well as DNA-DNA hybridization experiments (Figure 2A), revealed that they represent different strains of the same species. All these strains are able to oxidize As(III) and are resistant to As(III) (Table S2). Nevertheless, subtle physiological differences were observed (Table S2).

Figure 2. Genomic diversity among Thiomonas strains.

(A) Phylogenetic dendrogram of the SuperGene construct of both the 16S rRNA and rpoA genes of the Thiomonas strains used in this study. Ralstonia eutropha H16 served as the outgroup. The DNA-DNA hybridization percentage is included in brackets. nd: not determined (CB1 and CB6 were almost identical at the genetic content level. For this reason, DNA-DNA hybridization analyses were performed only with CB1). Numbers at the branches indicate percentage bootstrap support from 500 re-samplings for ML analysis. NJ analyses produced the same branch positions (not shown). The scale bar represents changes per nucleotide; (B) number of variable CDS exhibited by each strain determined by CGH, expressed as a percent of the total number of 3As CDS; (C) hierarchical clustering established based on CGH experiments, represented as a composite view of genome diversity in Thiomonas strains compared to 3As. The column represents genes as they are found along 3As genome, starting from the origin of replication (THI0001). Results for each strain are shown in each row. Red color indicates absence or strong divergence leading to reduced hybridization efficiency as compared to the corresponding Thiomonas sp. 3As gene (Log2(A635 nm/A532 nm) ≤−1)); Green color indicates a Log2(A635 nm/A532 nm) ≥1, suggesting duplication of this gene. The regions corresponding to ThGEI-A, B, C, E, F, G, H, I, J, K, O, P, Q, R and S are indicated by a blue arrow or a grey rectangle; (D) percent of CDS found in core (in grey) or in dispensable (in red) genome, in 3As and CB strains (1st column), in AMD-originated strains (3As, CB strains and “Tm. arsenivorans”, 2nd column), or in all Thiomonas strains (3rd column).

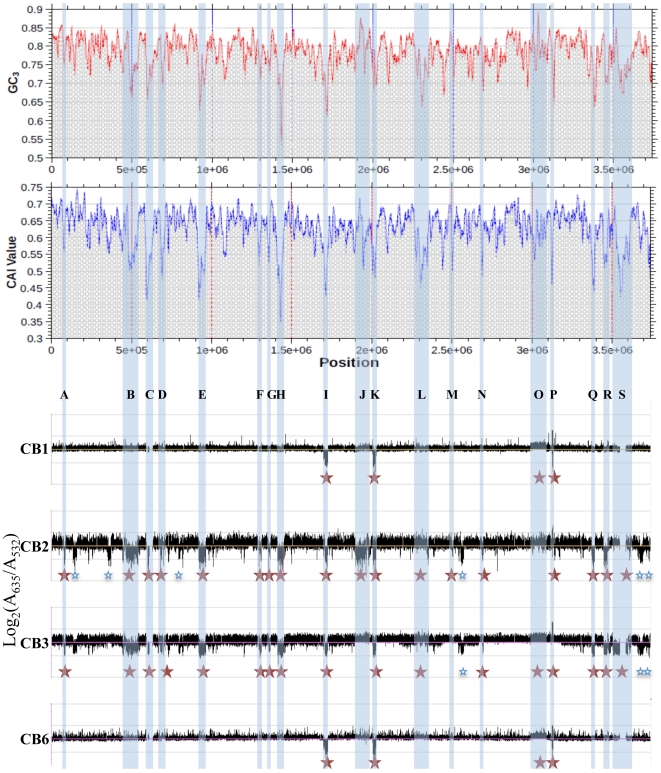

The existence of both phylogenetical relationships and physiological differences between these strains prompted us to perform a comparative genome analysis in order to address the evolution of Thiomonas strains. Therefore, genome variability was searched for by investigating genetic similarities and diversities among these closely related Thiomonas strains, using a Comparative Genomic Hybridization (CGH) approach (Figure 3). These experiments revealed the presence of a flexible CDS (duplicated, absent or highly divergent) pool in CB1, CB6 CB3 and CB2 (Figure 2B, Figure 3, ArrayExpress database, accession number E-MEXP-2260) representing 2.5%, 3.2%, 24.1% and 23.1% of the genome of strain 3As (Figure 2B), respectively. Altogether, these experiments led to the definition of 919 dispensable CDS, i.e. absent or highly divergent in at least one strain, accounting for 25.3% of strain 3As genes (Figure 2D). The remaining conserved CDS (2713 CDS, 74.7% of the genome of strain 3As) represent a common backbone of the “core” genes of this species.

Figure 3. Deleted or duplicated regions in CB strains, obtained by CGH experiments.

The codon adaptation index (CAI) and the GC content at the 3rd nucleotide position of each codon (GC3) of Thiomonas sp. 3As is shown in the upper part. Y-axis displays the log2-ratios (Cy5 (measured at 635 nm)/Cy3 (measured at 532 nm)). Red stars: variable regions found in CB strains and corresponding to GEIs; Blue stars: other variable regions.

In order to enlarge our comparative analysis, genomic similarities were similarly searched for in other Thiomonas species: an arsenite-oxidizing strain, “Tm. arsenivorans”, and two closely related strains that are unable to oxidize arsenite, Tm. perometabolis and Thiomonas sp. Ynys1 (Table S2, Figure 2, ArrayExpress database, accession number E-MEXP-2260). No significant hybridization was observed with oligomers corresponding to the plasmid, suggesting that pTHI is absent in all these strains. 18.4, 37.9 and 53.6% of the 3As CDS were flexible in “Tm. arsenivorans”, Ynys1 and Tm. perometabolis, respectively. Altogether, 1571 CDS accounting for at least 43.3% of the Thiomonas sp. 3As genome were found in the Thiomonas genus dispensable genome (Figure 3D). Finally, these CGH experiments revealed that the Thiomonas core genome contains 2,061 CDS (56.7% of the Thiomonas genome). Interestingly, almost all genes involved in acid resistance described above, were found in this core genome, as for example genes involved in polyphosphate granule synthesis, cfa and kdp genes, genes encoding ion transporter amino acid decarboxylase, formate dehydrogenase and other hydrogenases. One ars operon involved in arsenic resistance, i.e. ars1, and almost all genes involved in DNA repair were also conserved in all strains.

Among the flexible pool, 19 regions (ThGEI-A - ThGEI-S) had similarities with GEIs found in other bacterial genomes, suggesting that they were possibly acquired by horizontal gene transfer: (i) an abnormal deviation of the codon adaptation index (CAI) and the GC content at the 3rd nucleotide position of each codon (GC3) was observed in these regions as compared to the rest of the genome (Figure 3), (ii) many of their genes formed syntenic blocks that differed from the general synteny observed in the rest of the genome (Table S3), (iii) genes with mobile and extrachromosomal element functions such as those coding for integrases were localized within these regions, (iv) these regions were present at the 3′-end of tRNA or miscRNA genes, and/or (v) the borders of five deletions were verified in CB strains, by PCR and direct repeats (10 to 112 bp-long) bordering these GEIs were found (Table S3).

Genetic Content of the 19 Genomic Islands Found in Thiomonas sp. 3As Genome

Genes found in the 19 Thiomonas sp. 3As GEIs and the syntenies they share with genes in other bacteria are shown in Table S3. Interestingly, 70 (76.9%) of the 91 complete and partial ISs identified in the genome were located in genomic islands which represent only 21.5% of the genome (Figure S1A). In addition to the high numbers of ISs found in these GEIs, many hypothetical proteins as well as modification/restriction enzymes were encoded by these regions. In ten GEIs, accessory genes are involved in a particular metabolism such as acetoin, atrazin, benzoate, ethyl tetra-butyl ether (ETBE) hydroxyisobutyrate phenylacetic acid and urea degradation (ThGEI-E, ThGEI-C, ThGEI-S or ThGEI-R), or heavy metal resistance (ThGEI-J, ThGEI-L, ThGEI-O).

Interestingly, several genes found in distinct GEIs shared high amino acid identity (>70%, Figure S2). In addition, 47 genes found in the two regions ThGEI-C and ThGEI-S shared 100% identity. Because of this duplication, a 7 kbp region in ThGEI-S could not be sequenced and this gap may correspond to duplicated genes of ThGEI-C. These observations suggest that genomic rearrangements occurred between several GEIs. Moreover, several islands seem to be composite, since some fragments of such islands are deleted or duplicated in Thiomonas strains. Such composite structure may originate from insertion or excision of DNA elements in these GEIs, which involve integrase or excisionase. This hypothesis is strengthened by the observation that 32 integrases were found in almost all GEIs except for ThGEI-B and ThGEI-R. Some of such integrases are similar to phage integrases. In addition, 2 excisionases are present in ThGEI-H and ThGEI-P and such genes were localized in the vicinity of tRNA, an additional phage-like character.

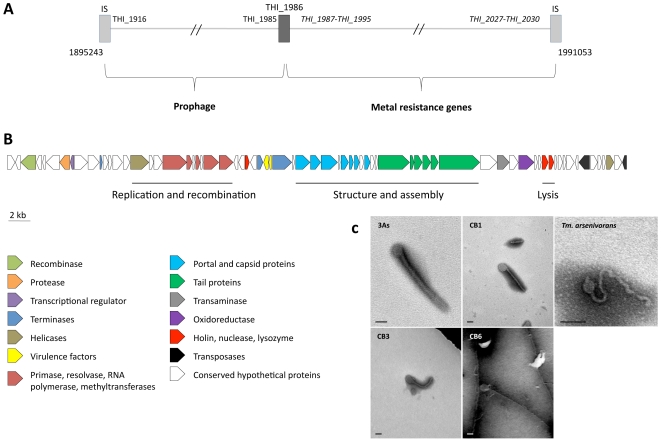

One GEI, ThGEI-J, contains a prophage region (55.6 kbp) and a cluster of 6 heavy metal resistance genes (39.4 kbp, i.e., cad, cus, czc and sil genes involved in resistance to Cd, Cu, Zn, Co and Ag) (Figure 4). The prophage region comprises 27 phage-related genes coding for structural and capsid or tail assembly proteins, replication, lysis and virulence factors. No conserved synteny with any previously described prophage could be observed. However, filamentous phage-like particles with icosahedral symmetry (capsid diameter of approximately 100 nm) and a various length tail (>600 nm), were observed by TEM from Thiomonas sp. 3As liquid cultures exposed to the phage lytic phase inducer mitomycin C. Similar phage-like particles were observed in growth culture supernatants from CB1, CB3, CB6 and “Tm. arsenivorans” (Figure 4) but not from CB2, Ynys1 and Tm. perometabolis (data not shown), in agreement with CGH results showing that the ThGEI-J is absent in these strains (Figure 3, Table S3, ArrayExpress database, accession number E-MEXP-2260). These observations suggest that this prophage-like region may be functional in 3As, CB1, CB3, CB6 and “Tm. arsenivorans” under stress conditions, resulting in the formation of phage-like particles.

Figure 4. Prophage-like region and phage-like particle.

(A) Schematic representation of the prophage-like region (55.6 kbp) and the contiguous metal resistance gene cluster (39.4 kbp). The total region is flanked by two ISs (light grey rectangles), and a partial transposase gene (THI_1986, dark grey rectangle) delimiting the two clusters. Genes in italics are duplicated in the Thiomonas sp. 3As genome; (B) organization of the prophage-like region. The 71 putative CDS, colored according to their category, are shown by arrows representing their direction. This cluster corresponds to the unique prophage-like region of the genome, containing notably structural, lysis and virulence associated phage genes; (C) transmission-electron micrographs of tailed bacteriophage-like particles from Thiomonas species. No bacteriophage-like particle was observed in Thiomonas sp. CB2 culture supernatant. Cultures were amended with mitomycin C (0.5 µg/mL). Bars: 100 nm. The 3As phage-like particle is hypothetically coded by the prophage-like region described above.

ThGEI-L and ThGEI-O Gene Content and Their Probable Acquisition by HGT

GEIs contribute to the adaptation of microorganisms to their ecological niches and participate in genome plasticity and evolution [14]. Therefore, the environmental conditions may influence the loss or conservation of GEIs. Such hypothesis was checked by searching for genome similarities between strains originated from similar environments, i.e. AMD. To this aim, a hierarchical clustering was established based on genomic comparisons (Figure 2C). Interestingly, the clustering obtained was different from that of the 16S rRNA/rpoA-based phylogenetic trees (Figure 2A). Indeed, all strains that originated from AMD heavily loaded with arsenic, i.e. “Tm. arsenivorans” and strains 3As, CB1, CB2, CB3 and CB6, grouped together, whereas Ynys1 and Tm. perometabolis formed a distinct group. Genes possibly dispensable for AMD survival were therefore searched for and we identified 2541 CDS conserved in all strains originated from AMD, and these CDS may constitute the “AMD” core genome of Thiomonas. Interestingly, several genes present in the ThGEI-L and ThGEI-O were conserved in AMD-originated strains but absent in the other strains (Figure 5).

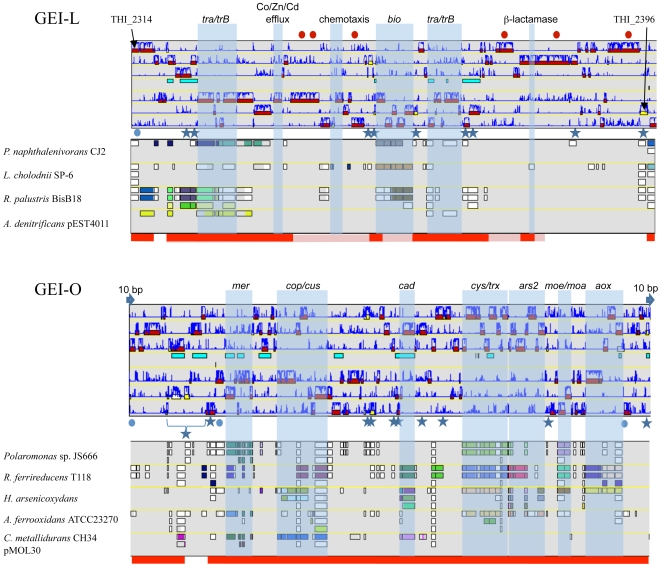

Figure 5. Genomic Island ThGEI-O containing genes involved in arsenic metabolism, and ThGEI-L.

The best synteny results of the genes were obtained with genes of Polaromonas naphthalenivorans CJ2, Leptothrix cholodnii SP-6, Rhodopseudomonas palustris BisB18, Achromobacter denitrificans (ThGEI-L) or Polaromonas sp. JS666, Rhodobacter ferrireducens, H. arsenicoxydans, Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans ATCC23270, and Cupriavidus metallidurans CH34 pMOL30 (ThGEI-O). Blue circles: genes originated from phage; Blue stars: transposases; Blue arrows: direct repeats. The genes conserved in 3As and CB strains or in AMD-originated strains (3As, CB strains and “Tm. arsenivorans”), are indicated by pink and red lines, respectively. Red dots indicate proteins with GGDEF and EAL domains.

The ThGEI-L carries genes involved in panthotenate and biotine synthesis, and may confer auxotrophy to the strains carrying this island. Moreover, genes encoding Co/Zn/Cd efflux pump were present in this GEI. In addition, this island is particularly rich in proteins with GGDEF and EAL domains. The GGDEF or EAL domain proteins are involved in either synthesis or hydrolysis of bis-(3′-5′) cyclic dimeric GMP (c-di-GMP), an ubiquitous second messenger in the bacterial world that regulates cell-surface-associated traits and motility [43],[44]. Because of the presence of such genes in the vicinity of 2 genes involved in chemotaxis, this island may be important for Thiomonas strains to form biofilm, a cellular process involved in resistance to toxic compounds [37]. Indeed, some of these genes are duplicated in CB2 and CB3 and these two strains were shown to develop better biofilm synthesis capacities (Table S2). This island also carries several genes encoding integrases and components of T4SS, such as virB1, virB4, trbBCD, traCEFGI, mob and a pilE-like gene. The presence of such genes suggests that this island originated from an integrative and conjugative element (ICE) that disseminates via conjugation [45]. These observations suggest that this island may be still mobile.

ThGEI-O contains the aox and ars2 genes (Figure 5). In addition, several other genes were found such as mer, cop, cus and cad genes involved in mercury, copper and cadmium resistance, respectively, cys involved in sulfate assimilation, and moe/moa genes involved in molybdenum cofactor biosynthesis as well as genes involved in exopolysaccharide production. The synteny of the genes found in Thiomonas sp. 3As ThGEI-O is not conserved in other arsenic-oxidizing bacteria (Figure 5). Several genes present in this region are duplicated in CB1 and CB6 (i.e. the cop and aox genes), or in CB3 (i. e. mer, cop, cus, dsb, cys, ars, moe/moa, aox, and ptxB genes). Only a single copy of this region is present in CB2 and 3As. PCR amplification and sequencing revealed that this ThGEI-O island is located in a different genomic region in CB2 as compared to 3As. Moreover, the aox and ars genes found in the ThGEI-O are duplicated in “Tm. arsenivorans” but absent in Ynys1 and Tm. perometabolis. Indeed, these two strains were unable to oxidize As(III), their As(III) resistance was lower than that of the other strains, and gene PCR amplification of aox and ars2 failed with DNA extracted from these strains (Table S2). Altogether, the presence of at least one copy of these genes in all six strains isolated from arsenic-rich environments (i.e. 3As, CB strains and “Tm. arsenivorans”) suggests that this GEI is of particular importance for the growth of Thiomonas strains in their toxic natural environment, AMD.

The evolutionary origin of the ThGEI-L and –O was investigated using two different approaches. First, we performed the phylogenetic analysis of the 196 genes contained in these two islands (Table S4, Table S5). The resulting trees revealed that these genes have very different evolutionary histories suggesting that the formation of ThGEI-L and –O islands occurred through the recruitment of genes from various origins by HGT (Table S4, columns 2–5). Interestingly, the closest homologue of 30/75 and 22/121 3As genes, in ThGEI-L and –O respectively, is found in other Thiomonas species (mainly Tm. intermedia), suggesting that the formation of these islands occurred prior to the diversification of the Thiomonas genus and is thus relatively ancient. This hypothesis is supported by the global correspondence analysis (COA) performed on the entire genome. Our results did not reveal any particular codon usage bias, strengthening the hypothesis that these ThGEIs are ancient in Thiomonas genus (Figure S3). This may explained why the major genes of these two islands are present in 3As, CB1, CB2, CB3, CB6 and “Thiomonas arsenivorans”, as for example, the ars2 operon and aox genes of the ThGEI-O. The phylogenetic analysis of aox genes revealed that all Thiomonas sequences grouped together with relationships that are very similar to organism relationships inferred with rpoA (Figure S4A and S4B). This indicates that these genes were already present in the Thiomonas ancestor and vertically transmitted in this genus, but lost in Ynys1 and Tm perometabolis. The phylogenetic analysis of the arsB genes, revealed that all Thiomonas sequences found in the ThGEI-O (i.e. arsB2 from 3As, CB1, CB2, CB3, CB6 and “Tm. arsenivorans”), grouped together but not with arsB1 genes that are part of the core genome of Thiomonas. Moreover, the evolutionary histories of these two proteins are different: ArsB1 proteins belong in a group containing mainly Alpha-Proteobacteria, whereas ArsB2 seems more closely related to Gamma-Proteobacteria (Figure S4C). These observations revealed that the ars1 and ars2 operons were not acquired from the same source or at the same time.

Discussion

The exploration of the Thiomonas sp. 3As genome suggests that this strain has a wide range of metabolic capacities at its disposal. Many of them may make this bacterium particularly well suited to survive in its extreme environment, the acidic and arsenic-rich waters draining the Carnoulès mine tailings, as for example biofilm formation and heavy metal resistance. Moreover, some metabolic capacities are unique as compared to another arsenic-resistant bacterium, whose genome has been recently sequenced and annotated, H. arsenicoxydans, a strict chemoorganotroph, isolated from activated sludge [38]. The first metabolic idiosyncrasy of Thiomonas sp. 3As is its particular carbon and energy metabolic capacities. Indeed, several organic or inorganic electron donors, such as reduced inorganic sulfur compounds [31], could be used. Second, some Thiomonas strains, i.e. CB1, CB3, CB6 and Tm. arsenivorans, carry two copies of the aox operon. As far as could be ascertained, this is the first example of aox gene duplication. Finally, Thiomonas sp. 3As is able to grow at pH 3. Several genes potentially involved in acid resistance were found in Thiomonas genome. In addition, the Carnoulès toxic environment may cause severe DNA damage in Thiomonas sp. 3As, since arsenic is a co-mutagen that inhibits the DNA repair system [41]. DNA repair genes that have been previously shown to be induced in the presence of arsenic in H. arsenicoxydans were all found in Thiomonas sp. 3As genome, and the expression of polA has been shown to be induced in the presence of arsenic [8]. These observations suggest that this bacterium may respond to DNA damage. Nevertheless, we can hypothesize that these stressful conditions may lead to genomic rearrangements in Thiomonas genome. This could explain the important genomic diversity observed among the members of both the 3As species and the Thiomonas genus.

At the intra-species level, the dispensable genome defined by comparison of the CB strains with the 3As genome corresponds to 25.3% of Thiomonas sp. 3As genome. By comparison, this value is higher than that observed, with the same approach, in other bacteria such as S. agalactiae (18%) [46], lower than values calculated in the case of a pathogenic E. coli (32.4%) [47], and similar to the value obtained in Bacillus subtilis (27%) [48]. The value calculated for Thiomonas 3As and CB strains is very high, considering that these strains were isolated from the same site, closely related, and appear to share a recent common ancestor, as illustrated by our phylogenetical analyses. Consequently, we observed that despite strong sequence identities of housekeeping genes such as 16S rRNA or rpoA, the whole genome DNA-DNA hybridization value was relatively low, close to or less than 70%, for strains CB2 and CB3. Conventionally, this should indicate that these bacteria belong to separate evolutionary lineages and must be considered as different species [49]. However, the 16S rRNA-rpoA based analysis and CGH experiments revealed that the low DNA-DNA hybridization value correlates with the duplication or absence of several GEIs in these strains. Consequently, we proposed that despite low DNA-DNA hybridization values, these five strains do indeed belong to the same species. Similarly, the DNA-DNA hybridization values obtained with Thiomonas sp. 3As as compared to strains Ynys1 and Tm. perometabolis were very low, as previously observed [5],[10]. Altogether, the great genetic diversity observed in the present study by CGH experiments revealed that DNA-DNA hybridization method may not be appropriate to evaluate evolutionary lineages in Thiomonas strains. In this respect the CGH approach seems to be a reliable phylogenetic tool for typing these strains, as suggested in previous studies on other bacteria [47],[50].

19 GEIs constitute a large flexible pool of accessory genes that encode adaptive traits. Some of these genes are not required for survival in AMD, since they were not found in all AMD-originated strain genome and correspond therefore to the dispensable gene pool. On the other hand, CGH-based clustering analysis revealed a significant relationship between 3As, CB1-6 and “Tm. arsenivorans”, which originate from geographically distinct but similarly arsenic-rich environments. The Thiomonas sp. 3As strain and “Tm. arsenivorans” form two distinct groups on the basis of phylogenetical, physiological and genetic analyses. Nevertheless, the percent of flexible CDS of Thiomonas sp. 3As with “Tm. arsenivorans”, is relatively low (18.4%), as compared to the value obtained with Ynys1 and Tm. perometabolis (37.9% and 53.6%, respectively). This value obtained with “Tm. arsenivorans” was in the same order of magnitude as the value obtained with CB2 and CB3 (23% and 23.6%, respectively). Altogether, 70% of the Thiomonas sp. 3As genome was conserved among all strains originated from AMD. Interestingly, two GEIs were conserved or duplicated in all these strains originated from AMD, i.e. ThGEI-O that carries the arsenic-specific operons ars2 and aox, and genes involved in heavy metal resistance, and ThGEI-L that carries several genes involved in heavy metal resistance, biofilm formation and/or motility. Therefore, these GEIs shared by these species are presumably part of the AMD-originated Thiomonas core genome. This observation suggests that the acquisition or loss of these GEIs contributes to the evolution of this subgroup of the Thiomonas genus and that the evolution of Thiomonas strains has been influenced by their similar environments.

Several observations suggest that Thiomonas genome evolved by acquiring GEIs through horizontal gene transfer or by genome rearrangement. In the case of two islands, ThGEI-L and –O, an in-deep phylogenetic analysis revealed that these islands have a composite structure probably due to secondary acquisition or losses/rearrangements of some genes. In the case of other GEIs, the existence of HGT is suggested by the fact that genes form syntenic blocks and their GC% were divergent from the rest of the genome. Three mechanisms, i. e. conjugation, transduction and natural transformation, known to be involved in HGT in bacteria [14] may explain GEIs acquisition in Thiomonas. One prophage was found in the Thiomonas genome and may contribute to horizontal gene transfer, as previously shown in pathogenic bacteria such as Vibrio cholera, Yersinia pseudotuberculosis, Bartonella [51]–[54], Cyanobacteria [55],[56] or for the transfer of pathogenic island from S. aureus to Listeria monocytogenes [57]. In addition, genes encoding Type IV secretion systems (T4SS) were carried by the pTHI plasmid and the ThGEI-L. It has been recently proposed that GEI-type T4SS are involved in the propagation of GEIs [45],[58]. Therefore, it could also be possible that Thiomonas acquired such islands by conjugation. Orthologs of Neisseria gonorrhoeae genes involved in natural transformation [59] were also found in Thiomonas sp. 3As genome, i.e. the pil genes encoding a type IV pili components and comALMP. This suggests that Thiomonas strains are able to acquire exogenous DNA. Finally, several observations suggest that Thiomonas genome has undergone genomic rearrangements contributing to its evolution, as illustrated for the two GEIs, ThGEI-L and -O. Such rearrangements may be promoted by repeat sequences or duplications, that are at the origin of recombination [60]. Indeed, repeats sequences represent 7.62% of the Thiomonas sp. 3As genome, and some of the loci found in the GEIs are duplicated with high sequence identities, as ThGEI-C and ThGEI-S that are almost identical. In addition, several IS elements are highly similar, sharing more than 70% nucleotide identity. Interestingly, the majority of the ISs present in the Thiomonas sp. 3As genome are found in GEIs. This observation suggests that ISs duplication has played a significant role in both assembly and evolution of these islands, or participated in GEI reshuffling. Altogether, conjugation, transduction, natural transformation and recombination may be at the origin of the high genomic content divergence observed among Thiomonas strains.

In conclusion, evidences presented here suggest that Thiomonas sp. 3As has acquired some of its particular capacities that contribute to its survival and proliferation in AMD by horizontal gene transfer and genomic rearrangement. Furthermore, these data revealed a high degree of genetic variability within the Thiomonas genus, even at the intra-species level. Indeed, the analysis of duplications and deletions of GEIs in several strains revealed the huge significance of these GEIs in the evolution of the Thiomonas genus, as well as the influence of the natural environment on the genomic evolution of this extremophile. The majority of intra or inter-species comparisons carried out thus far have concerned pathogens. Our analysis shows that GEIs play also an important role in the evolution of environmental isolates exposed to toxic elements.

Materials and Methods

Bacterial Strains

Thiomonas sp. 3As was obtained from the acidic waters draining the Carnoulès mine tailings, southeastern France [5]. Thiomonas strains CB1, CB2, CB3 and CB6 were isolated from the same site: briefly, the isolates were purified by repeated single colony isolation on either R2A medium (Difco; strains CB1, CB2 and CB3) or 100∶10 medium ([61]; strain CB6). Physiological, phylogenetic and genetic analyses of these four strains were performed as described previously (Tables S2, S6, [8]). Strains Thiomonas Ynys1 [62], Tm. perometabolis [63] and “Tm. arsenivorans” [9] were cultivated as previously described [8]. DNA-DNA hybridization was carried out as described by [64] under consideration of the modifications described by [65] using a model Cary 100 Bio UV/VIS-spectrophotometer equipped with a peltier-thermostated 6×6 multicell changer and a temperature controller with in situ temperature probe (Varian).

DNA Preparation, Sequencing, and Annotation

DNA was extracted and purified from liquid cultures of pure isolates as previously described [8]. The complete genome sequence of Thiomonas sp. 3As was determined using the whole-genome shotgun method. Three libraries were constructed, two plasmids and one BAC to order contigs, as previously described [38]. From these libraries, 26,112, 7,680 and 3,840 clones were end-sequenced, and the assembly was performed with the Phred/Phrap/Consed software package (www.phrap.com), as described previously [38]. An addition of 3,292 sequences was needed for the finishing phase. Coding sequences were predicted as previously described [38]. Putative orthology relationships between two genomes were defined by gene pairs satisfying either the Bidirectional Best Hit criterion or an alignment threshold (at least 40% sequence identity over at least 80% of the length of the smallest protein). These relationships were subsequently used to search for conserved gene clusters (synteny groups) among several bacterial genomes using an algorithm based on an exact graph-theoretical approach [66]. This method allowed for multiple correspondences between genes, detection of paralogy relationships, gene fusions, and chromosomal rearrangements (inversion, insertion/deletion). The ‘gap’ parameter, representing the maximum number of consecutive genes that are not involved in a synteny group, was set to five. Manual validation of automatic annotations was performed in a relational database (ArsenoScope, https://www.genoscope.cns.fr/agc/mage/wwwpkgdb/MageHome/index.php?webpage=mage) using the MaGe web interface [67]. The EMBL (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/embl) accession numbers for the genome of Thiomonas sp. 3As are FP475956 (chromosome) and FP475957 (plasmid).

Comparative Genome Hybridization (CGH) Array

A custom 385K array for the Thiomonas sp. 3As chromosome and plasmid was designed and constructed by NimbleGen Systems. This DNA array encompasses 3,645 CDS of the 3As genome. Probe length was 50 nt and current mean probe spacing was 7 nt. Genomic DNAs from all strains were extracted with the Wizard Genomic DNA Purification Kit (Promega). DNA samples were labeled and purified using the BioPrime Array CGH Genomic Labeling System protocol (Invitrogen). Test (Cy3-labeled) and reference (Thiomonas sp. 3As genomic DNA, Cy5-labeled) genomic DNAs were combined (400 pmol fluorescent dye each) and were co-hybridized to the array for 16 h at 42°C in a MAUI Hybridization System (BioMicro System) and slides were washed according to NimbleGen's recommendations. Dye swap experiments were used to compare Thiomonas sp. 3As and Thiomonas sp. CB1 genomic DNAs. Arrays were scanned with an Axon 4000B scanner. Data were acquired and analyzed using NimbleScan 2.0 and SignalMap 1.9 software (Roche, NimbleGen) and analyzed using the Partek Genomics Suite software (Partek Incorporated, St. Louis, Missouri, U.S.A.). Briefly, log2-ratios (Cy5/Cy3) were calculated using the segMNT algorithm and gains and losses of genomic material were identified using Partek Genomics Suite Software, as follows: the files were imported and normalized with the qspline normalization [68] by NimbleScan. These data were then imported into the Partek Genomics Suite Soft. The segmentation was performed using the circular binary segmentation algorithm from Olshen et al. [69]. Permutations are used to provide the reference distribution to check a second time. 1000 permutations are run using the Partek software. If the resulting p-value is below the threshold (p = 0.01), then a breakpoint is added. To verify deletions, PCRs were performed as described in supplementary materials, using primers designed to anneal at the borders of the expected deletions. The CGH data are available in the database ArrayExpress, with the accession number E-MEXP-2260.

Phage Excision and Electron Microscopy

Phage formation was induced by treating exponential cultures with mitomycin C (0.5 µg/mL) for 24 h. The suspension was negatively stained with 16% ammonium molybdate for 10 seconds and dried over Formvar-coated nickel grids. Grids were examined at 40,000-fold magnification using a Hitachi 600 transmission electron microscope at 75 kV and photographed using a Hamamatsu ORCA-HR camera (Hamamatsu City, Shizuoka, Japan) with the AMT software (Advanced Microscopy Techniques Corp., Danvers, MA).

Phylogenetic and Correspondence Analysis

For each CDS, homologues were searched in NCBI databases. The 300 sequences with the best score were aligned using ClustalW [70]. Alignments were checked by hand and positions with more than 5% of gaps were automatically removed. Neighbor-Joining trees were constructed and analyzed to determine the evolutionary origin of each CDS (Table S4). The correspondence analysis (COA) [71] was performed using the library FactoMineR (http://factominer.free.fr) from the statistical package R (http://www.r-project.org). For all annotated genes of Thiomonas sp. 3As, we determined all the relative synonymous codon usage values [72] obtaining a matrix where the rows represent the genes and the 57 columns are the RSCU values for individual codons. As usual, the 3 TER codons were excluded from the analysis. Codons corresponding to Cystein (TGC/TGT) and the duet of Arginine (AGG/AGA) were also removed from the analysis as they induce systematic artefactual biases [73].

Supporting Information

Circular representations of Thiomonas chromosome and pTHI plasmid. Gene organization found in (A) the Thiomonas sp. 3As chromosome. The localisation of the 19 GEIs (A-S) is schematized with grey triangles; (B) the plasmid pTHI. Circles display (from the outside): (1) GC percent deviation (GC window - mean GC) in a 1000-bp window; (2) Predicted CDSs transcribed in the clockwise direction (red); (3) Predicted CDSs transcribed in the counterclockwise direction (blue); (4) GC skew (G+C/G−C) in a 1000-bp window; (5) Transposable elements (pink) and pseudogenes (grey).

(26.67 MB TIF)

Duplication of genes found in the several GEIs. Only those with high amino acid identities are shown.

(0.95 MB TIF)

Factor maps obtained by crossing the first and second axes of the correspondence analysis computed on 3,632 Thiomonas sp. 3As genes. For clarity, genes that are not harbored in the 19 GEIs (defined in Table S3) are not represented.

(0.94 MB TIF)

Phylogenetic trees of arsenic specific genes compared to rpoA. blue: gamma-Proteobacteria; brown: Hydrogenophilales; orange: Methylophilales; light green: Nitrosomonadales; deep green: Rhodocyclales; red: Neisseriales; pink: Burkholderiales. (A) rpoA; (B) aoxB; (C) arsB.

(2.19 MB TIF)

List of ISs present in Thiomonas sp. 3As genome and plasmid.

(0.05 MB XLS)

Summary of physiological and genetic data obtained from the Thiomonas strains used in this study.

(0.04 MB DOC)

Genomic Islands (GEIs) or islets found in the Thiomonas sp. 3As genome.

(0.04 MB XLS)

Phylogenetic analysis of the 75 genes contained in the ThGEI-L island.

(0.04 MB XLS)

Phylogenetic analysis of the 121 genes contained in the ThGEI-0 island.

(0.05 MB XLS)

PCR targets and GenBank Accession IDs of strains used in this study.

(0.03 MB DOC)

Acknowledgments

Tm. perometabolis was obtained from the Pasteur Institute, Paris, France. Ynys1 was kindly donated by Kevin Hallberg and D. B. Johnson (Bangor University, North Wales, UK).

Footnotes

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

This study was supported by the ANR 07-BLAN-0118 project (Agence Nationale de la Recherche). Annotation and database management were supported by a grant from ANR 07-PFTV MicroScope project. CGB was supported by a grant from the University of Strasbourg; MM by a grant from ANR COBIAS project (PRECODD 2007, Agence Nationale de la Recherche); JC, AHS, SW, and DS by a grant from the Ministere de la Recherche et de la Technologie; and AL by a grant from ADEME-BRGM. This work was performed within the framework of the French research network “Arsenic metabolism in microorganisms” (GDR2909-CNRS)(http://gdr2909.u-strasbg.fr). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Johnson DB, Hallberg KB. The microbiology of acidic mine waters. Res Microbiol. 2003;154:466–473. doi: 10.1016/S0923-2508(03)00114-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hallberg KB, Johnson DB. Microbiology of a wetland ecosystem constructed to remediate mine drainage from a heavy metal mine. Sci Total Environ. 2005;338:53–66. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2004.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bruneel O, Personné JC, Casiot C, Leblanc M, Elbaz-Poulichet F, et al. Mediation of arsenic oxidation by Thiomonas sp. in acid-mine drainage (Carnoulès, France). J Appl Microbiol. 2003;95:492–499. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2672.2003.02004.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Battaglia-Brunet F, Dictor MC, Garrido F, Crouzet C, Morin D, et al. An arsenic(III)-oxidizing bacterial population: selection, characterization, and performance in reactors. J Appl Microbiol. 2002;93:656–667. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2672.2002.01726.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Duquesne K, Lieutaud A, Ratouchniak J, Muller D, Lett MC, et al. Arsenite oxidation by a chemoautotrophic moderately acidophilic Thiomonas sp.: from the strain isolation to the gene study. Environ Microbiol. 2008;10:228–237. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2007.01447.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Coupland K, Battaglia-Brunet F, Hallberg KB, Dictor MC, Garrido F, et al. Oxidation of iron, sulfur and arsenic in mine waters and mine wastes: an important role of novel Thiomonas spp. In: Tsezos AHM, Remondaki E, editors. Biohydrometallurgy: a sustainable technology in evolution. Zografou, Greece: National Technical University of Athens; 2004. pp. 639–646. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moreira D, Amils R. Phylogeny of Thiobacillus cuprinus and other mixotrophic thiobacilli: proposal for Thiomonas gen. nov. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1997;47:522–528. doi: 10.1099/00207713-47-2-522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bryan CG, Marchal M, Battaglia-Brunet F, Klugler V, Lemaitre-Guillier C, et al. Carbon and arsenic metabolism in Thiomonas strains: differences revealed diverse adaptation processes. BMC Microbiol. 2009;9:127. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-9-127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Battaglia-Brunet F, Joulian C, Garrido F, Dictor MC, Morin D, et al. Oxidation of arsenite by Thiomonas strains and characterization of Thiomonas arsenivorans sp. nov. Antonie van Leeuwenhoek. 2006;89:99–108. doi: 10.1007/s10482-005-9013-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Katayama Y, Uchino Y, Wood AP, Kelly DP. Confirmation of Thiomonas delicata (formerly Thiobacillus delicatus) as a distinct species of the genus Thiomonas Moreira and Amils 1997 with comments on some species currently assigned to the genus. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2006;56:2553–2557. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.64299-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hallberg KB, Johnson DB. Novel acidophiles isolated from moderately acidic mine drainage waters. Hydrometallurgy. 2003;71:139–148. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Casiot C, Morin G, Juillot F, Bruneel O, Personné JC, et al. Bacterial immobilization and oxidation of arsenic in acid mine drainage (Carnoulès creek, France). Water Res. 2003;37:2929–2936. doi: 10.1016/S0043-1354(03)00080-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bentley S. Sequencing the species pan-genome. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2009;7:258–259. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Juhas M, van der Meer JR, Gaillard M, Harding RM, Hood DW, et al. Genomic islands: tools of bacterial horizontal gene transfer and evolution. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2009;33:376–393. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2008.00136.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maiques E, Ubeda C, Tormo MA, Ferrer MD, Lasa I, et al. Role of staphylococcal phage and SaPI integrase in intra- and interspecies SaPI transfer. J Bacteriol. 2007;189:5608–5616. doi: 10.1128/JB.00619-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lesic B, Carniel E. Horizontal transfer of the high-pathogenicity island of Yersinia pseudotuberculosis. J Bacteriol. 2005;187:3352–3358. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.10.3352-3358.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sentchilo V, Ravatn R, Werlen C, Zehnder AJ, van der Meer JR. Unusual integrase gene expression on the clc genomic island in Pseudomonas sp. strain B13. J Bacteriol. 2003;185:4530–4538. doi: 10.1128/JB.185.15.4530-4538.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hacker J, Kaper JB. Pathogenicity islands and the evolution of microbes. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2000;54:641–679. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.54.1.641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tettelin H, Riley D, Cattuto C, Medini D. Comparative genomics: the bacterial pan-genome. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2008;11:472–477. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2008.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Medini D, Donati C, Tettelin H, Masignani V, Rappuoli R. The microbial pan-genome. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2005;15:589–594. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2005.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Achtman M, Wagner M. Microbial diversity and the genetic nature of microbial species. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2008;6:431–440. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fraser C, Alm EJ, Polz MF, Spratt BG, Hanage WP. The bacterial species challenge: making sense of genetic and ecological diversity. Science. 2009;323:741–746. doi: 10.1126/science.1159388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tettelin H, Masignani V, Cieslewicz MJ, Donati C, Medini D, et al. Genome analysis of multiple pathogenic isolates of Streptococcus agalactiae: implications for the microbial “pan-genome”. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:13950–13955. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506758102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kettler GC, Martiny AC, Huang K, Zucker J, Coleman ML, et al. Patterns and implications of gene gain and loss in the evolution of Prochlorococcus. PLoS Genet. 2007;3:e231. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0030231. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0030231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Coleman ML, Sullivan MB, Martiny AC, Steglich C, Barry K, et al. Genomic islands and the ecology and evolution of Prochlorococcus. Science. 2006;311:1768–1770. doi: 10.1126/science.1122050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Costechareyre D, Bertolla F, Nesme X. Homologous recombination in Agrobacterium: potential implications for the genomic species concept in bacteria. Mol Biol Evol. 2009;26:167–176. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msn236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rothschild LJ, Mancinelli RL. Life in extreme environments. Nature. 2001;409:1092–1101. doi: 10.1038/35059215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schluter A, Szczepanowski R, Puhler A, Top EM. Genomics of IncP-1 antibiotic resistance plasmids isolated from wastewater treatment plants provides evidence for a widely accessible drug resistance gene pool. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2007;31:449–477. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2007.00074.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nascimento AM, Chartone-Souza E. Operon mer: bacterial resistance to mercury and potential for bioremediation of contaminated environments. Genet Mol Res. 2003;2:92–101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Friedrich CG, Bardischewsky F, Rother D, Quentmeier A, Fischer J. Prokaryotic sulfur oxidation. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2005;8:253–259. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2005.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Frigaard NU, Dahl C. Sulfur metabolism in phototrophic sulfur bacteria. Adv Microb Physiol. 2009;54:103–200. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2911(08)00002-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Slonczewski JL, Fujisawa M, Dopson M, Krulwich TA. Cytoplasmic pH measurement and homeostasis in bacteria and archaea. Adv Microb Physiol. 2009;55:1–79, 317. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2911(09)05501-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Baker-Austin C, Dopson M. Life in acid: pH homeostasis in acidophiles. Trends Microbiol. 2007;15:165–171. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2007.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stingl K, Altendorf K, Bakker EP. Acid survival of Helicobacter pylori: how does urease activity trigger cytoplasmic pH homeostasis? Trends Microbiol. 2002;10:70–74. doi: 10.1016/s0966-842x(01)02287-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Iyer R, Iverson TM, Accardi A, Miller C. A biological role for prokaryotic ClC chloride channels. Nature. 2002;419:715–718. doi: 10.1038/nature01000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Silver S, Phung le T. A bacterial view of the periodic table: genes and proteins for toxic inorganic ions. J Ind Microbiol Biotechnol. 2005;32:587–605. doi: 10.1007/s10295-005-0019-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Harrison JJ, Ceri H, Turner RJ. Multimetal resistance and tolerance in microbial biofilms. Nat Rev Micro. 2007;5:928–938. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Muller D, Médigue C, Koechler S, Barbe V, Barakat M, et al. A tale of two oxidation states: bacterial colonization of arsenic-rich environments. PLoS Genet. 2007;3:e53. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0030053. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0030053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Silver S, Phung LT. Genes and enzymes involved in bacterial oxidation and reduction of inorganic arsenic. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2005;71:599–608. doi: 10.1128/AEM.71.2.599-608.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Meng YL, Liu Z, Rosen BP. As(III) and Sb(III) uptake by GlpF and efflux by ArsB in Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:18334–18341. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M400037200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hartwig A, Blessing H, Schwerdtle T, Walter I. Modulation of DNA repair processes by arsenic and selenium compounds. Toxicology. 2003;193:161–169. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2003.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schwerdtle T, Walter I, Mackiw I, Hartwig A. Induction of oxidative DNA damage by arsenite and its trivalent and pentavalent methylated metabolites in cultured human cells and isolated DNA. Carcinogenesis. 2003;24:967–974. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgg018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schirmer T, Jenal U. Structural and mechanistic determinants of c-di-GMP signalling. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2009;7:724–735. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hengge R. Principles of c-di-GMP signalling in bacteria. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2009;7:263–273. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Burrus V, Waldor MK. Shaping bacterial genomes with integrative and conjugative elements. Res Microbiol. 2004;155:376–386. doi: 10.1016/j.resmic.2004.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tettelin H, Masignani V, Cieslewicz MJ, Eisen JA, Peterson S, et al. Complete genome sequence and comparative genomic analysis of an emerging human pathogen, serotype V Streptococcus agalactiae. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:12391–12396. doi: 10.1073/pnas.182380799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fukiya S, Mizoguchi H, Tobe T, Mori H. Extensive genomic diversity in pathogenic Escherichia coli and Shigella strains revealed by comparative genomic hybridization microarray. J Bacteriol. 2004;186:3911–3921. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.12.3911-3921.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Earl AM, Losick R, Kolter R. Bacillus subtilis genome diversity. J Bacteriol. 2007;189:1163–1170. doi: 10.1128/JB.01343-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wayne LG, Brenner DJ, Colwell RR, Grimont PAD, Kandler O, et al. Report of the ad hoc committee on reconciliation of approaches to bacterial systematics. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1987;37:463–464. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Binnewies TT, Motro Y, Hallin PF, Lund O, Dunn D, et al. Ten years of bacterial genome sequencing: comparative-genomics-based discoveries. Funct Integr Genomics. 2006;6:165–185. doi: 10.1007/s10142-006-0027-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Li M, Kotetishvili M, Chen Y, Sozhamannan S. Comparative genomic analyses of the Vibrio pathogenicity island and cholera toxin prophage regions in nonepidemic serogroup strains of Vibrio cholerae. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2003;69:1728–1738. doi: 10.1128/AEM.69.3.1728-1738.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Derbise A, Chenal-Francisque V, Pouillot F, Fayolle C, Prevost MC, et al. A horizontally acquired filamentous phage contributes to the pathogenicity of the plague Bacillus. Mol Microbiol. 2007;63:1145–1157. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05570.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Brussow H, Canchaya C, Hardt WD. Phages and the evolution of bacterial pathogens: from genomic rearrangements to lysogenic conversion. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2004;68:560–602. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.68.3.560-602.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Berglund EC, Frank AC, Calteau A, Vinnere Pettersson O, Granberg F, et al. Run-off replication of host-adaptability genes is associated with gene transfer agents in the genome of mouse-infecting Bartonella grahamii. PLoS Genet. 2009;5:e1000546. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000546. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Dammeyer T, Bagby SC, Sullivan MB, Chisholm SW, Frankenberg-Dinkel N. Efficient phage-mediated pigment biosynthesis in oceanic cyanobacteria. Curr Biol. 2008;18:442–448. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2008.02.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zeidner G, Bielawski JP, Shmoish M, Scanlan DJ, Sabehi G, et al. Potential photosynthesis gene recombination between Prochlorococcus and Synechococcus via viral intermediates. Environ Microbiol. 2005;7:1505–1513. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2005.00833.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chen J, Novick RP. Phage-mediated intergeneric transfer of toxin genes. Science. 2009;323:139–141. doi: 10.1126/science.1164783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Juhas M, Crook DW, Hood DW. Type IV secretion systems: tools of bacterial horizontal gene transfer and virulence. Cell Microbiol. 2008;10:2377–2386. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2008.01187.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hamilton HL, Dillard JP. Natural transformation of Neisseria gonorrhoeae: from DNA donation to homologous recombination. Mol Microbiol. 2006;59:376–385. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04964.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Treangen TJ, Abraham AL, Touchon M, Rocha EP. Genesis, effects and fates of repeats in prokaryotic genomes. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2009;33:539–571. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2009.00169.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Schrader JA, Holmes DS. Phenotypic switching of Thiobacillus ferrooxidans. J Bacteriol. 1988;170:3915–3923. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.9.3915-3923.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hallberg KB, Johnson DB. Novel acidophiles isolated from moderately acidic mine drainage waters. Hydrometallurgy. 2003;71:139–148. [Google Scholar]

- 63.London J, Rittenberg SC. Thiobacillus perometabolis nov. sp., a non-autotrophic thiobacillus. Arch Mikrobiol. 1967;59:218–225. doi: 10.1007/BF00406335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.De Ley J, Cattoir H, Reynaerts A. The quantitative measurement of DNA hybridization from renaturation rates. Eur J Biochem. 1970;12:133–142. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1970.tb00830.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Huss VAR, Festl H, Schleifer KH. Studies on the spectrophotometric determination of DNA hybridization from renaturates rates. Syst Appl Microbiol. 1983;4:184–192. doi: 10.1016/S0723-2020(83)80048-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Boyer F, Morgat A, Labarre L, Pothier J, Viari A. Syntons, metabolons and interactons: an exact graph-theoretical approach for exploring neighbourhood between genomic and functional data. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:4209–4215. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Vallenet D, Labarre L, Rouy Z, Barbe V, Bocs S, et al. MaGe: a microbial genome annotation system supported by synteny results. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:53–65. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkj406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Workman C, Jensen LJ, Jarmer H, Berka R, Gautier L, et al. A new non-linear normalization method for reducing variability in DNA microarray experiments. Genome Biol. 2002;3:research0048.0041–0048.0016. doi: 10.1186/gb-2002-3-9-research0048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Olshen AB, Venkatraman ES, Lucito R, Wigler M. Circular binary segmentation for the analysis of array-based DNA copy number data. Biostatistics. 2004;5:557–572. doi: 10.1093/biostatistics/kxh008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Thompson JD, Plewniak F, Thierry J, Poch O. DbClustal: rapid and reliable global multiple alignments of protein sequences detected by database searches. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:2919–2926. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.15.2919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Benzécri JP. Paris: Dunod; 1984. L'analyse des correspondances. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Sharp PM, Tuohy TM, Mosurski KR. Codon usage in yeast: cluster analysis clearly differentiates highly and lowly expressed genes. Nucleic Acids Res. 1986;14:5125–5143. doi: 10.1093/nar/14.13.5125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Perriere G, Thioulouse J. Use and misuse of correspondence analysis in codon usage studies. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:4548–4555. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkf565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Circular representations of Thiomonas chromosome and pTHI plasmid. Gene organization found in (A) the Thiomonas sp. 3As chromosome. The localisation of the 19 GEIs (A-S) is schematized with grey triangles; (B) the plasmid pTHI. Circles display (from the outside): (1) GC percent deviation (GC window - mean GC) in a 1000-bp window; (2) Predicted CDSs transcribed in the clockwise direction (red); (3) Predicted CDSs transcribed in the counterclockwise direction (blue); (4) GC skew (G+C/G−C) in a 1000-bp window; (5) Transposable elements (pink) and pseudogenes (grey).

(26.67 MB TIF)

Duplication of genes found in the several GEIs. Only those with high amino acid identities are shown.

(0.95 MB TIF)

Factor maps obtained by crossing the first and second axes of the correspondence analysis computed on 3,632 Thiomonas sp. 3As genes. For clarity, genes that are not harbored in the 19 GEIs (defined in Table S3) are not represented.

(0.94 MB TIF)

Phylogenetic trees of arsenic specific genes compared to rpoA. blue: gamma-Proteobacteria; brown: Hydrogenophilales; orange: Methylophilales; light green: Nitrosomonadales; deep green: Rhodocyclales; red: Neisseriales; pink: Burkholderiales. (A) rpoA; (B) aoxB; (C) arsB.

(2.19 MB TIF)

List of ISs present in Thiomonas sp. 3As genome and plasmid.

(0.05 MB XLS)

Summary of physiological and genetic data obtained from the Thiomonas strains used in this study.

(0.04 MB DOC)

Genomic Islands (GEIs) or islets found in the Thiomonas sp. 3As genome.

(0.04 MB XLS)

Phylogenetic analysis of the 75 genes contained in the ThGEI-L island.

(0.04 MB XLS)

Phylogenetic analysis of the 121 genes contained in the ThGEI-0 island.

(0.05 MB XLS)

PCR targets and GenBank Accession IDs of strains used in this study.

(0.03 MB DOC)