Summary

Background

Type I interferons (IFNs) play an important role in the pathogenesis of many autoimmune disorders including psoriasis. In the presence of IFN-α and granulocyte/macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF), monocytes differentiate into dendritic cells (DCs) referred to as IFN-DCs. IFN-DCs potentially mimic DC populations involved in psoriasis and express a wide range of Toll-like receptor (TLR) subtypes.

Objectives

Recently, it was shown that single-stranded RNA (ssRNA) triggers TLR7 and TLR8; therefore we studied ssRNA, as a surrogate for ssRNA viruses and their impact on IFN-DCs.

Methods

We established culture conditions for IFN-DCs, generated from plastic adherent monocytes using GM-CSF plus IFN-α. For DC stimulation ssRNA40, a 20-mer ssRNA oligonucleotide was used. The phenotypic analysis of DC preparations was performed using flow cytometry. The production of various cytokines was analysed by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, and real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction was used to quantify TLR and cytokine gene expression. The ability of IFN-DCs to stimulate allogeneic T-cell proliferation was evaluated in a mixed leucocyte reaction.

Results

We found that IFN-DCs express mRNA for TLR7 and TLR8 and that ssRNA stimulation significantly improves their costimulatory molecule expression, stabilizes their phenotype and enhances their capacity to stimulate naive T-cell proliferation. Unstimulated IFN-DCs did not produce bioactive interleukin (IL)-12 and produced low levels of other proinflammatory cytokines. In contrast, ssRNA stimulation led to a significant production of IL-12p70, IL-1β, IL-6 and tumour necrosis factor α. IFN-DCs contained mRNA for IL-12p35, IL-12p40, IL-23p19, IL-27p28 and IL-27EBI, which was further increased by incubation with ssRNA.

Conclusions

Our study sheds light on a potential role for IFN-α and viral infections in triggering DC populations in psoriasis. These results provide additional data for the better understanding of human autoimmune and antiviral responses and may also have implications for strategies developing cancer immunotherapy.

Keywords: dendritic cell, interferon-α, psoriasis, single-stranded RNA, Toll-like receptor

Psoriasis, the most common inflammatory skin disorder, is characterized by the self-perpetuating activation of autoimmune T cells. It is believed that various environmental factors including viral infections play a role in chronic relapses. Dendritic cells (DCs) are professional antigen-presenting cells (APCs) bridging innate and acquired immunity, recognizing infections, secreting proinflammatory cytokines and stimulating primary T-cell immune responses.1 It has been suggested that DCs, as part of the local network of skin-resident immune cells, are important in the autoimmune pathology of psoriasis and they may provide the link between environmental factors and T-cell proliferation.2 In addition to their contribution to autoimmune pathology, DCs may be promising adjuvants for the immunotherapy of cancer.3–5

Recently, some studies indicated that type I interferons (IFNs) have the capability to promote the differentiation and activation of human DCs.6–12 In the presence of granulocyte/macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) and IFN-α monocytes are capable of differentiating into IFN-DCs. IFN-DCs show the phenotypical and functional properties of partially mature DCs.7 They have the capacity to induce T-helper (Th) 1 responses and to promote efficiently in vitro and in vivo the expansion of CD8+ T lymphocytes. 13

Immature and mature DCs express a variety of innate pattern-recognition receptors including members of the Toll-like receptor (TLR) family.14 Various TLR ligands activate DCs and help their differentiation into professional APCs. Immature IFN-DCs express TLR1, -2, -3, -4, -5, -6, -7 and -8.8 Natural agonists for TLR7 and TLR8 have lately been identified. Synthetic imidazo-quinoline-like molecules, imiquimod (R-837), resiquimod (R-848), S-27609 and guanosine analogues such as loxoribine have been shown to activate nuclear factor (NF)-κB through TLR7. Resiquimod also activates NF-κB through TLR815,16 and recent studies showed that the immunostimulatory potential of single-stranded RNA (ssRNA) is mediated through murine TLR717 and human TLR8.18

IFN-α itself contributes to the pathogenesis of many autoimmune diseases including systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE)19 and psoriasis.20 Furthermore, evidence is accumulating that IFN-DCs themselves have a central role in the autoimmunity of SLE21 and they differentiate from monocytes during viral infections when IFNs are produced; therefore they can model DC populations involved in autoimmunity. In addition, IFN-DCs are thought to be promising candidates for immunotherapeutic studies.

In humans, the TLR8-specific ssRNA stimulus may lead to autoimmunity;22 it mimics ssRNA viruses such as influenza and parechovirus,23,24 and as different TLR stimuli are known to induce DC maturation14 it may be a helpful adjuvant in developing vaccines.

As the effect of ssRNA on the phenotypical and functional properties of IFN-DCs has not been studied yet we have characterized the costimulatory molecule expression, phenotype stability, cytokine production pattern and naive T cell-promoting capacity of ssRNA-stimulated and unstimulated IFN-DCs. We believe that the results obtained from our model system help to reveal further the major role of INF-α and viral triggers in psoriasis and other autoimmune disease development. Furthermore our results may also lead to the development of new anticancer vaccination strategies.

Materials and methods

Reagents

The complete medium (CM) used throughout consisted of RPMI 1640 (Gibco, Basel, Switzerland) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS) purchased from Life Technologies (Eggenstein, Germany), 10 U mL−1 penicillin/streptomycin (Gibco) and 50 µg mL−1 l-glutamine (Seromed, Basel, Switzerland). The IFN-DC medium consisted of CM supplemented with 1000 U mL−1 GM-CSF (CellGenix, Freiburg, Germany) and 1000 U mL−1 IFN-α (Essex Chemie AG, Lucerne, Switzerland). ssRNA40, a 20-mer ssRNA oligonucleotide containing a GU-rich sequence complexed with the cationic lipid LyoVeci™ was purchased from LabForce AG (Nunningen, Switzerland).

In vitro generation of interferon dendritic cells from monocytes

We established culture conditions for IFN-DCs, generated from plastic adherent monocytes using GM-CSF plus IFN-α as previously described in the literature.8 Briefly, peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were isolated from buffy coats obtained from the Swiss Red Cross Blood Transfusion Service using Ficoll–Hypaque gradient centrifugation. PBMCs were plated in 10-ml volumes of RPMI 1640 supplemented with 50 µg mL−1 l-glutamine in 75 cm2 culture flasks (107 PBMCs mL−1). After 2 h of incubation adherent cells were cultured in IFN-DC medium until day 3. On day 3 non-adherent and loosely adherent cells were harvested from the dishes and were resuspended in fresh IFN-DC medium supplemented with or without ssRNA and were cultured until day 5. For the stability assay IFN-DCs were harvested again on day 5 and were resuspended in CM until day 7.

Analysis of costimulatory molecule expression of interferon dendritic cells

The phenotypic analysis of DC preparations was performed using a flow cytometer (FACSCalibur; Becton Dickinson, Basel, Switzerland) with Cell Quest software. The cells were analysed for CD80, CD83, CD86 and HLA-DR expression. All phycoerythrin- or fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) were purchased from BD Pharmingen (Basel, Switzerland).

Cytokine measurement

Supernatants of stimulated and unstimulated IFN-DCs were harvested at different time points (12, 24 and 48 h) and stored at −20 °C. Samples were sent to Pierce Biotechnology (Rockford, IL, U.S.A.) for analysis using SearchLight multiplex cytokine enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) analysis of the following cytokines: interleukin (IL)-12p70, IL-1β, IL-6 and tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-α. Each sample from each donor was analysed in triplicate.

Real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction

Total cellular RNA was extracted from IFN-DCs at various time points using a High Pure RNA Isolation Kit (Roche Diagnostics GmbH, Mannheim, Germany). For real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) analysis, the following primer sequences, annealing temperatures and cycles were used: human TLR7, sense primer 5′-CGA ACC TCA CCC TCA CCA TTA-3′ and antisense primer 5′-GGG ACG GCT GTG ACA TTG TTA-3′; human TLR8, sense primer 5′-CTG CTG CTG AGT CAT AAC AG-3′ and antisense primer 5′-CCA TGT TCT CAT CCA TTA GC-3′; IL-12p35, sense primer 5′- TTC ACC ACT CCC AAA ACC TGC-3′ and antisense primer 5′-GAG GCC AGG CAA CTC CCA TTA G-3′; IL-12p40, sense primer 5′-ATG CCG TTC ACA AGC TCA AGT ATG-3′ and antisense primer 5′-CTG GGC CCG CAC GCT AAT-3′; IL-23p19, sense primer 5′-TTC CCC ATA TCC AGT GTG GAG-3′ and antisense primer 5′-TCA GGG AGC AGA GAA GGC TC-3′; IL-27p28, sense primer 5′-ATC TCA CCT GCC AGG AGT GAA-3′ and antisense primer 5′-TGA AGC GTG GTG GAG ATG AAG-3′; and IL-27EBI3, sense primer 5′-CCG TGT CCT TCA TTG CCA CGT ACA G-3′ and antisense primer 5′-GGT GAC ATT GAG CAC GTA GGG AGC CAT-3′. PCR was performed with the LightCycler FastStart DNA Sybr Green I kit (Roche Diagnostics GmbH) according to the provided protocol. To control for specificity of the products, a melting curve analysis was performed and amplification of the expected single products was confirmed on 1% agarose gels stained with ethidium bromide. Results were quantified with LightCycler Software v.4.0 (Roche Applied Science, Mannheim, Germany).

Allogeneic mixed leucocyte reaction

On day 5 of DC cultures, allogeneic CD4+ CD45RA+ T cells were isolated from PBMCs by negative selection using the human naive CD4+ T-Cell Isolation Kit (Miltenyi Biotech, Gladbach, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s protocol, and purity checked by flow cytometry (FACS) using anti-CD45RA mAb (Immunotech, Marseille, France) staining. These cells were used as responder cells. T cells were resuspended in CM and plated at a concentration of 105 cells per well in a 96-well flat-bottomed plate. IFN-DCs cultured with or without ssRNA stimulus after being irradiated were resuspended in CM and added to responder cells in triplicates at graded DC : T-cell ratios. Cells were cocultured for 5 days, with the addition of 1 µCi [3H]thymidine per well for the last 18 h of culture. DC-induced T-cell proliferation was measured using in a liquid scintillation counter. Results were expressed as mean counts per min of triplicate culture wells.

Statistical analysis

Data were statistically analysed using the Student’s t-test and results were considered significant when P < 0·05.

Results

Interferon dendritic cells upregulate Toll-like receptors 7 and 8 and maturation markers in response to single-stranded RNA

Our real-time qPCR results confirmed that IFN-DCs express TLR7 and TLR8 mRNA and that the addition of 5 µg mL−1 ssRNA upregulates both TLRs on the mRNA level (Fig. 1). To evaluate the effect of ssRNA on their maturation status, IFN-DCs were treated with 5 µg mL−1 or 10 µg mL−1 ssRNA on day 3 and their phenotype was analysed on day 5. IFN-DCs stimulated with 5 µg mL−1 ssRNA showed high HLA-DR (93·6 ± 3·7%) expression and the upregulation of CD80 (94 ± 2%) and CD86 (90·3 ± 0·5%) molecules was observed. On day 5 unstimulated control IFN-DC cultures showed no or only weak CD83 expression (0–16%) indicating an immature phenotype. However, after ssRNA exposure CD83 expression levels increased substantially (69·6 ± 9·2%), showing that ssRNA is a strong maturation stimulus. Similar upregulation of all costimulatory molecules was observed when IFN-DCs were stimulated with 10 µg mL−1 ssRNA. As the lower ssRNA concentration (5 µg mL−1) was sufficient to obtain a mature phenotype, we used this concentration in our further experiments. Figure 2 is a representative experiment of three comparing the expression of different surface markers of ssRNA-treated and control IFN-DCs on day 5.

Fig 1.

Interferon dendritic cells (IFN-DCs) express Toll-like receptor (TLR) 7 and TLR8, and single-stranded RNA (ssRNA) treatment upregulates their expression level. Adherent monocytes were cultured in the presence of IFN-α and granulocyte/macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) until day 3. On day 3 cells were resuspended in fresh IFN-DC medium containing ssRNA or left untreated and were cultured until day 5. Bars represent real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) analyses of TLR7 and TLR8 expression levels in cDNA obtained from IFN-DCs on day 3 and on day 5. Values are expressed in femtograms of the target gene in 100 ng of total cDNA. Mean ± SD values from three independent experiments are shown.

Fig 2.

Interferon dendritic cells (IFN-DCs) mature in response to single-stranded RNA (ssRNA) stimuation with high CD83 expression. Adherent monocytes were cultured in the presence of IFN-α and granulocyte/macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) until day 3. On day 3 cells were resuspended in fresh IFN-DC medium containing ssRNA or left untreated and were cultured until day 5. One representative FACS experiment shows the expression of HLA-DR, CD80, CD83 and CD86 of ssRNA-stimulated IFN-DCs and of unstimulated normal counterparts on day 5. Shaded histograms show the background staining with isotype control monoclonal antibodies, and unshaded histograms represent specific staining of the indicated cell surface markers. Percentage of positive cells and mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) are indicated.

Single-stranded RNA treatment increases the stability of mature interferon dendritic cells

Fully mature and stable DCs should preserve their phenotype when they no longer receive maturation stimuli. Therefore we performed a ‘washout test’ to evaluate the stability of IFN-DCs. On day 5 ssRNA-stimulated and control IFN-DCs were harvested, washed with phosphate-buffered saline and were placed in CM. No cytokines were added. After 48 h of culture immunophenotype analysis was performed. On day 5 ssRNA-treated IFN-DCs had better phenotypic characteristics compared with untreated controls. On day 7 of culture unstimulated IFN-DCs expressed high levels of CD80 (82·3 ± 8·7%) and HLA-DR (95·6 ± 1·2%) molecules. The expression level of CD86 was 71·3 ± 5·18% and CD83 expression was completely lost. In contrast, ssRNA-treated IFN-DCs preserved a better phenotype as the expression levels of all costimulatory molecules such as HLA-DR (95·6 ± 1·2%), CD80 (82 ± 8·5%) and CD86 (85·6 ± 0·4%) remained high and also kept their CD83 (44·3 ± 9·4%) expression showing a more stable phenotype. Figure 3 shows a representative stability assay of three, comparing the expression of different surface markers of ssRNA-treated and control IFN-DCs on day 5 and day 7.

Fig 3.

Stimulation by single-stranded RNA (ssRNA) helps to preserve the mature phenotype of interferon dendritic cells (IFN-DCs). The ‘washout test’ was performed as described in Materials and methods on different IFN-DC cultures. On day 5 IFN-DCs stimulated with ssRNA and control IFN-DCs were washed with phosphate-buffered saline and were placed in complete medium. No cytokines were added. After 48 h of culture immunophenotype analysis was performed. One representative two-colour FACS experiment shows the expression of HLA-DR, CD80, CD83 and CD86 of ssRNA-stimulated IFN-DCs and of unstimulated normal counterparts on day 5 and on day 7. Shaded histograms show the background staining with isotype control monoclonal antibodies, and unshaded histograms represent specific staining of the indicated cell surface markers. Percentage of positive cells and mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) are indicated.

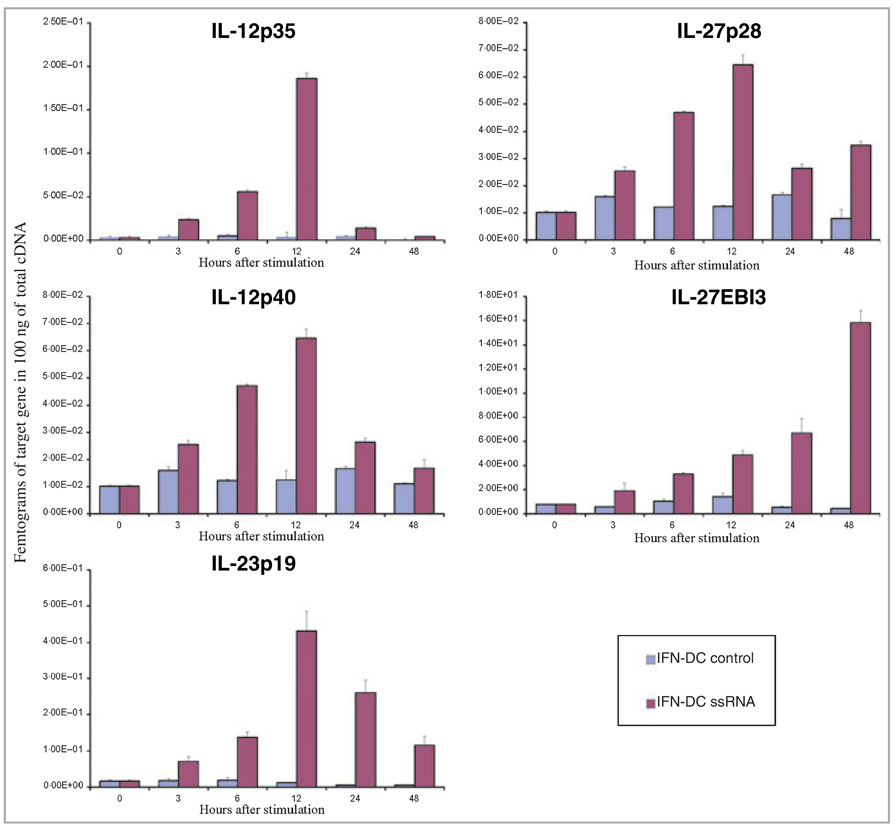

Single-stranded RNA-treated interferon dendritic cells produce high levels of bioactive T-helper 1 cytokines and have increased mRNA levels of all subunits of interleukin-12, -23 and -27

Supernatants of ssRNA-stimulated and control IFN-DCs were analysed for IL-12p70, IL-1β, IL-6 and TNF-α using a standard ELISA method and the mRNA levels of IL-12p35, IL-12p40, IL-23p19, IL-27p28 and IL-27EBI3 were evaluated with real-time qPCR. ssRNA treatment for 12, 24 and 48 h resulted in an increased production of the following proteins: IL-12p70, IL-1β, IL-6 and TNF-α (Fig. 4). Control supernatants of untreated cells were negative for IL-12p70 and only contained low levels of IL-1β, IL-6 and TNF-α. After ssRNA stimulation, the expression of mRNA for IL-12p35, IL-12p40, IL-23p19 and IL-27p28 (Fig. 5) was upregulated within the first 3–6 h after activation, peaking at approximately 12 h and decreasing by 24–48 h. The upregulation of IL-27EBI3 expression seemed to display a delayed time course (Fig. 5).

Fig 4.

Treatment with single-stranded RNA (ssRNA) causes interferon dendritic cells (IFN-DCs) to produce interleukin IL-12p70 (IL-12p70) and increases their IL-1β, IL-6 and tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-α production. Adherent monocytes were cultured in the presence of IFN-α and granulocyte/macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) until day 3. On day 3 cells were resuspended in fresh IFN-DC medium containing different concentrations of ssRNA or left untreated and were cultured until day 5. At different time points supernatants were collected and the levels of IL-12p70, IL-1β, IL-6 and TNF-α were analysed by a standard enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) method. Mean ± SD values of three independent experiments are shown.

Fig 5.

Treatment with single-stranded RNA (ssRNA) increases the mRNA levels of interleukin-12 (IL-12)-related cytokines. Adherent monocytes were cultured in the presence of interferon (IFN)-α and granulocyte/macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) until day 3. On day 3 cells were resuspended in fresh IFN dendritic cells (IFN-DC) medium containing different concentrations of ssRNA or left untreated and were cultured until day 5. Cytokine expression was analysed in cDNA obtained from ssRNA-stimulated and unstimulated IFN-DCs at different time points. Real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) values are expressed in femtograms of the target gene in 100 ng of total cDNA. Mean ± SD values of three independent experiments are shown.

Single-stranded RNA-matured interferon dendritic cells have increased stimulatory potential in mixed leucocyte reactions

We compared the capacity of control and ssRNA-matured DC cultures to stimulate naive T cells in a primary allogeneic mixed leucocyte reaction (MLR). On day 5 ssRNA-treated and control IFN-DCs were irradiated, followed by the co-incubation with naive CD4+ T cells of allogeneic donors. At different DC : T-cell ratios ssRNA stimulation induced a 1·2- to 1·8-fold increase in T-cell proliferative responses compared with untreated controls (Fig. 6).

Fig 6.

Stimulation by single-stranded RNA (ssRNA) increases the stimulatory potential of interferon dendritic cells (IFN-DCs) in mixed leucocyte reaction (MLR). ssRNA-stimulated IFN-DCs (black) and unstimulated controls (pink) generated from monocytes as described in Materials and methods, were cocultured with allogeneic purified naive CD4+ T cells at different DC/T-cell ratios for 5 days. Thymidine incorporation was measured after an 18 h pulse with 1 µCi of [3H]thymidine. Results are shown as mean ± SD of triplicate values. *P < 0·0001; **P < 0·05; cpm, counts per min.

Discussion

DCs are potent APCs amplifying immune responses against chronic infections25,26 and cancer,3–5,27,28 and many findings prove that various DC types have a role in the pathogenesis of autoimmune disorders including psoriasis.2,29,30 Circulating blood-derived monocytes that migrate into the skin may be potential precursors of IFN-DCs, because different cell types in the epidermis and dermis are able to produce cytokines such as GM-CSF31,32 and IFN-α,33 which are required for the differentiation of monocytes to DCs.

Immature and mature IFN-DCs express TLR7 and TLR88 among other TLRs and recently it was shown that the physiological ligand for mouse TLR717 and for human TLR8 is ssRNA;18 therefore we were interested to determine whether or not in our model system, ssRNA, representing a viral trigger, is required to induce a mature IFN-DC phenotype.

We confirmed the TLR7 and TLR8 expression by IFN-DCs with real-time qPCR and showed that ssRNA stimulation enhances their TLR7 and TLR8 mRNA content. We think that the explanation of this phenomenon is connected to the capacity of IFN-DCs to produce IFN-α themselves.8 It was recently shown that adherent monocytes, the ‘source’ of IFN-DCs, produce high levels of IFN-α after small interfering RNA stimulation,34 and upon their differentiation into immature IFN-DCs, they upregulate their TLR7 and TLR8 expression. 8

Without additional stimulation IFN-DCs expressed high levels of HLA-DR, CD80 and CD86 surface molecules, but we observed no or very weak CD83 expression, indicating a partially mature DC phenotype. However, when stimulated with ssRNA IFN-DCs expressed high HLA-DR, CD80 and CD86 levels and we observed a marked increase in their CD83 expression, showing that ssRNA strongly stimulates IFN-DC maturation and after performing the ‘washout test’ it was clear that the ssRNA stimulus also helps to preserve their mature stage.

Next we tested how the ssRNA stimulus affects the expression of various Th1 cytokines. Stimulation with ssRNA resulted in a marked increase in both subunits of IL-12p70 (p35 and p40), IL-23 (p40 and p19) and IL-27 (p28 and EBI) on the mRNA level. In parallel with these findings ssRNA stimulation enhanced the levels of bioactive IL-12p70, IL-1β, IL-6 and TNF-α in the supernatants of cultures. In sharp contrast, in control cultures we could not detect any IL-12p70 and could only detect very low levels of other Th1 cytokines.

Cytokines produced by DCs driving the development of Th1 cells include IL-1235 and the novel IL-12 family members such as IL-23 and IL-27.36,37 IL-12 has an important role in inducing naive CD4+ T-cell differentiation into Th1 effector cells, it stimulates natural killer cells and CD8+ T cells to produce IFN-α35 and it is required for the development of protective innate and adaptive immune responses to intracellular pathogens. IL-12 is directly involved in the pathogenesis of several autoimmune diseases38 and maintains the inflammation in psoriatic lesions. 39

IL-23 has a unique role in the regulation of effector T-cell function as it induces the production of IL-17, but not IFN-α or IL-4.40,41 Importantly, IL-23p19 mRNA is increased in psoriatic skin42 and when delivered intradermally in mice IL-23 leads to a psoriasis-like phenotype.38

IL-27 has a notable effect on naive Th cells and is of crucial importance for the initial and early IFN-α production, either alone or in synergy with IL-12.43 On the other hand in mice it was recently shown that IL-27 may also limit inflammation; 38 therefore it seems that this cytokine may have both proinflammatory and anti-inflammatory activities.

To our knowledge this is the first study indicating that human IFN-DCs are capable of producing IL-23 and IL-27 and that stimulation by ssRNA enhances their expression of IL-12 and other Th1 cytokines.

In addition, we determined the T cell-polarizing capacities of ssRNA-treated and control IFN-DCs and we observed that ssRNA-stimulated IFN-DCs induced a stronger allogeneic naive T-cell proliferation. It is well known that IFN-DCs play an important role in autoimmunity.21 In patients with SLE normally quiescent monocytes act as DCs because of circulating IFN-α, which induces monocytes to differentiate into IFN-DCs capable of efficiently capturing apoptotic cells and nucleosomes in the blood of SLE patients.44,45 Then the presentation of autoantigens to CD4+ T cells may initiate the expansion of autoreactive T cells and autoantibody-producing B cells.

It is already known that in psoriasis plasmacytoid DCs are present in symptomless skin and this DC subset is able to produce IFN-α during viral infections;33 therefore IFN-DCs may also differentiate from monocytes when large amounts of IFNs are generated. An additional viral infection can facilitate the functional maturation of IFN-DCs and may induce their production of IFN-α and TNF-α, which are two important cytokines involved in the proximal events driving psoriatic inflammation. The results obtained in our model system high-light the possible role of IFN-DCs in triggering and also in maintaining psoriasis.

Additionally, our experiments may help to understand previous observations indicating that in humans the TLR8-specific ssRNA stimulus may lead to autoimmunity,22 is present in viral infections,23,24,46 and in mice can act as a potent adjuvant of adaptive immunological responses.47

In conclusion, our study sheds light on a potential role for IFN-α and viral infections in triggering DC populations in psoriasis, provides further data to increase understanding of human antiviral and autoimmune responses and may influence future strategies for developing DC-based cancer immunotherapy.

Acknowledgments

Arpad Farkas is on the leave from the Department of Dermatology and Allergology in Szeged, Hungary and his work was supported by an International Union against Cancer (UICC) fellowship.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

None declared.

References

- 1.Banchereau J, Palucka AK. Dendritic cells as therapeutic vaccines against cancer. Nat Rev Immunol. 2005;5:296–306. doi: 10.1038/nri1592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boyman O, Conrad C, Tonel G, et al. The pathogenic role of tissue-resident immune cells in psoriasis. Trends Immunol. 2007;28:51–57. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2006.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nestle FO, Farkas A, Conrad C. Dendritic-cell-based therapeutic vaccination against cancer. Curr Opin Immunol. 2005;17:163–169. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2005.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Farkas A, Conrad C, Tonel G, et al. Current state and perspectives of dendritic cell vaccination in cancer immunotherapy. Skin Pharmacol Physiol. 2006;19:124–131. doi: 10.1159/000092592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schuler G, Schuler-Thurner B, Steinman RM. The use of dendritic cells in cancer immunotherapy. Curr Opin Immunol. 2003;15:138–147. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(03)00015-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Paquette RL, Hsu NC, Kiertscher SM, et al. Interferon-alpha and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor differentiate peripheral blood monocytes into potent antigen-presenting cells. J Leukoc Biol. 1998;64:358–367. doi: 10.1002/jlb.64.3.358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Parlato S, Santini SM, Lapenta C, et al. Expression of CCR-7, MIP-3beta, and Th-1 chemokines in type I IFN-induced monocyte-derived dendritic cells: importance for the rapid acquisition of potent migratory and functional activities. Blood. 2001;98:3022–3029. doi: 10.1182/blood.v98.10.3022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mohty M, Vialle-Castellano A, Nunes JA, et al. IFN-alpha skews monocyte differentiation into Toll-like receptor 7-expressing dendritic cells with potent functional activities. J Immunol. 2003;171:3385–3393. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.7.3385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Santini SM, Di Pucchio T, Lapenta C, et al. A new type I IFN-mediated pathway for the rapid differentiation of monocytes into highly active dendritic cells. Stem Cells. 2003;21:357–362. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.21-3-357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Santini SM, Lapenta C, Logozzi M, et al. Type I interferon as a powerful adjuvant for monocyte-derived dendritic cell development and activity in vitro and in Hu-PBL-SCID mice. J Exp Med. 2000;191:1777–1788. doi: 10.1084/jem.191.10.1777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Luft T, Luetjens P, Hochrein H, et al. IFN-alpha enhances CD40 ligand-mediated activation of immature monocyte-derived dendritic cells. Int Immunol. 2002;14:367–380. doi: 10.1093/intimm/14.4.367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Luft T, Pang KC, Thomas E, et al. Type I IFNs enhance the terminal differentiation of dendritic cells. J Immunol. 1998;161:1947–1953. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Santodonato L, D’Agostino G, Nisini R, et al. Monocyte-derived dendritic cells generated after a short-term culture with IFN-alpha and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor stimulate a potent Epstein–Barr virus-specific CD8+ T cell response. J Immunol. 2003;170:5195–5202. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.10.5195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Iwasaki A, Medzhitov R. Toll-like receptor control of the adaptive immune responses. Nat Immunol. 2004;5:987–995. doi: 10.1038/ni1112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hemmi H, Kaisho T, Takeuchi O, et al. Small anti-viral compounds activate immune cells via the TLR7 MyD88-dependent signaling pathway. Nat Immunol. 2002;3:196–200. doi: 10.1038/ni758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jurk M, Heil F, Vollmer J, et al. Human TLR7 or TLR8 independently confer responsiveness to the antiviral compound R-848. Nat Immunol. 2002;3:499. doi: 10.1038/ni0602-499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Diebold SS, Kaisho T, Hemmi H, et al. Innate antiviral responses by means of TLR7-mediated recognition of single-stranded RNA. Science. 2004;303:1529–1531. doi: 10.1126/science.1093616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Heil F, Hemmi H, Hochrein H, et al. Species-specific recognition of single-stranded RNA via toll-like receptor 7 and 8. Science. 2004;303:1526–1529. doi: 10.1126/science.1093620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pascual V, Farkas L, Banchereau J. Systemic lupus erythematosus: all roads lead to type I interferons. Curr Opin Immunol. 2006;18:676–682. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2006.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nestle FO, Conrad C, Tun-Kyi A, et al. Plasmacytoid predendritic cells initiate psoriasis through interferon-alpha production. J Exp Med. 2005;202:135–143. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Blanco P, Palucka AK, Gill M, et al. Induction of dendritic cell differentiation by IFN-alpha in systemic lupus erythematosus. Science. 2001;294:1540–1543. doi: 10.1126/science.1064890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Triantafilou K, Orthopoulos G, Vakakis E, et al. Human cardiac inflammatory responses triggered by Coxsackie B viruses are mainly Toll-like receptor (TLR) 8-dependent. Cell Microbiol. 2005;7:1117–1126. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2005.00537.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Triantafilou K, Vakakis E, Orthopoulos G, et al. TLR8 and TLR7 are involved in the host’s immune response to human parechovirus 1. Eur J Immunol. 2005;35:2416–2423. doi: 10.1002/eji.200526149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Osterlund P, Veckman V, Siren J, et al. Gene expression and antiviral activity of alpha/beta interferons and interleukin-29 in virus-infected human myeloid dendritic cells. J Virol. 2005;79:9608–9617. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.15.9608-9617.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moll H, Berberich C. Dendritic cells as vectors for vaccination against infectious diseases. Int J Med Microbiol. 2001;291:323–329. doi: 10.1078/1438-4221-00138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gowans EJ, Jones KL, Bharadwaj M, et al. Prospects for dendritic cell vaccination in persistent infection with hepatitis C virus. J Clin Virol. 2004;30:283–290. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2004.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nestle FO, Alijagic S, Gilliet M, et al. Vaccination of melanoma patients with peptide- or tumor lysate-pulsed dendritic cells. Nat Med. 1998;4:328–332. doi: 10.1038/nm0398-328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Maier T, Tun-Kyi A, Tassis A, et al. Vaccination of patients with cutaneous T-cell lymphoma using intranodal injection of autologous tumor-lysate-pulsed dendritic cells. Blood. 2003;102:2338–2344. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-08-2455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Turley SJ. Dendritic cells: inciting and inhibiting autoimmunity. Curr Opin Immunol. 2002;14:765–770. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(02)00399-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bayry J, Thirion M, Delignat S, et al. Dendritic cells and autoimmunity. Autoimmun Rev. 2004;3:183–187. doi: 10.1016/S1568-9972(03)00104-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sugita K, Kabashima K, Atarashi K, et al. Innate immunity mediated by epidermal keratinocytes promotes acquired immunity involving Langerhans cells and T cells in the skin. Clin Exp Immunol. 2007;147:176–183. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2006.03258.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhao W, Oskeritzian CA, Pozez AL, et al. Cytokine production by skin-derived mast cells: endogenous proteases are responsible for degradation of cytokines. J Immunol. 2005;175:2635–2642. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.4.2635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Colonna M, Trinchieri G, Liu YJ. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells in immunity. Nat Immunol. 2004;5:1219–1226. doi: 10.1038/ni1141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sioud M. Induction of inflammatory cytokines and interferon responses by double-stranded and single-stranded siRNAs is sequence-dependent and requires endosomal localization. J Mol Biol. 2005;348:1079–1090. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Trinchieri G. Interleukin-12 and the regulation of innate resistance and adaptive immunity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2003;3:133–146. doi: 10.1038/nri1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cordoba-Rodriguez R, Frucht DM. IL-23 and IL-27: new members of the growing family of IL-12-related cytokines with important implications for therapeutics. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2003;3:715–723. doi: 10.1517/14712598.3.5.715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hunter CA. New IL-12-family members: IL-23 and IL-27, cytokines with divergent functions. Nat Rev Immunol. 2005;5:521–531. doi: 10.1038/nri1648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kastelein RA, Hunter CA, Cua DJ. Discovery and biology of IL-23 and IL-27: related but functionally distinct regulators of inflammation. Annu Rev Immunol. 2007;25:221–242. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.22.012703.104758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yawalkar N, Karlen S, Hunger R, et al. Expression of interleukin-12 is increased in psoriatic skin. J Invest Dermatol. 1998;111:1053–1057. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.1998.00446.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Aggarwal S, Ghilardi N, Xie MH, et al. Interleukin-23 promotes a distinct CD4 T cell activation state characterized by the production of interleukin-17. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:1910–1914. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M207577200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Langrish CL, Chen Y, Blumenschein WM, et al. IL-23 drives a pathogenic T cell population that induces autoimmune inflammation. J Exp Med. 2005;201:233–240. doi: 10.1084/jem.20041257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lee E, Trepicchio WL, Oestreicher JL, et al. Increased expression of interleukin 23 p19 and p40 in lesional skin of patients with psori-asis vulgaris. J Exp Med. 2004;199:125–130. doi: 10.1084/jem.20030451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pflanz S, Timans JC, Cheung J, et al. IL-27, a heterodimeric cytokine composed of EBI3 and p28 protein, induces proliferation of naive CD4(+) T cells. Immunity. 2002;16:779–790. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(02)00324-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Amoura Z, Piette JC, Chabre H, et al. Circulating plasma levels of nucleosomes in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus: correlation with serum antinucleosome antibody titers and absence of clear association with disease activity. Arthritis Rheum. 1997;40:2217–2225. doi: 10.1002/art.1780401217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Herrmann M, Voll RE, Kalden JR. Etiopathogenesis of systemic lupus erythematosus. Immunol Today. 2000;21:424–426. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5699(00)01675-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schlaepfer E, Audige A, Joller H, et al. TLR7/8 triggering exerts opposing effects in acute versus latent HIV infection. J Immunol. 2006;176:2888–2895. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.5.2888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Westwood A, Elvin SJ, Healey GD, et al. Immunological responses after immunisation of mice with microparticles containing antigen and single stranded RNA (polyuridylic acid) Vaccine. 2006;24:1736–1743. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2005.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]