Abstract

Background and purpose:

Current single drug treatments for rheumatoid arthritis have problems of limited efficacy and/or high toxicity. This study investigates the benefits of individual and combined treatments with dexamethasone and substance P and glutamate receptor antagonists in a rat model of arthritis.

Experimental approach:

Arthritis was induced in rats by unilateral intra-articular injection of Freund's complete adjuvant. Separate groups of rats were subjected to the following treatments 15 min before induction of arthritis: (i) control with no drug treatment; (ii) single intra-articular injection of a NK1 receptor antagonist RP67580; (iii) single intra-articular injection of a NMDA receptor antagonist AP7 plus a non-NMDA receptor antagonist CNQX; (iv) daily oral dexamethasone; and (v) combined treatment with dexamethasone and all of the above receptor antagonists. Knee joint allodynia, swelling, hyperaemia and histological changes were examined over a period of 7 days.

Key results:

Treatment with dexamethasone suppressed joint swelling, hyperaemia and histological changes that include polymorphonuclear cell infiltration, synovial tissue proliferation and cartilage erosion in the arthritic rat knees. Treatment with RP67580 or AP7 plus CNQX did not attenuate hyperaemia or histological changes, but reduced joint allodynia and swelling. Co-administration of dexamethasone with these receptor antagonists produced greater inhibition on joint allodynia and swelling than their individual effects.

Conclusions and implications:

The data suggest substance P and glutamate contribute to arthritic pain and joint swelling. The efficacy of dexamethasone in reducing arthritic pain and joint swelling can be improved by co-administration of substance P and glutamate receptor antagonists.

Keywords: dexamethasone, substance P, glutamate, RP67580, AP7, CNQX, adjuvant-induced arthritis

Introduction

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a disease typified by pain and inflammation in the affected joint. This disease involves complex interactions of a large number of endogenous mediators that include arachidonic acid metabolites, vasoactive amines and cytokines such as tumour necrosis factor-α (TNFα) and interleukin-1 (IL-1) and IL-6 (Dayer et al., 1986; Lipsky et al., 1989; Feldmann et al., 1996; Arend, 1997). Conventional anti-arthritic therapy employs non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, disease modifying anti-rheumatic drugs, glucocorticoids, or the newly developed anti-cytokine drugs (Majithia and Geraci, 2007). These agents are effective at inhibiting or modulating the actions of only some of these mediators; often, the actions of other mediators are not affected. The least toxic of these agents are also the least efficacious. Anti-TNF therapy is generally associated with an improvement in symptoms of RA, including inhibition of joint destruction (Nagasawa and Takeuchi, 2009), but some patients may experience inadequate response or may not tolerate the agent. Recently, several new biological therapies were introduced for RA and were reported to be effective in arresting joint destruction and shown good tolerance by RA patients. These newly developed agents include the anti-CD20 antibody rituximab, which was the first B-cell-specific therapy approved for the treatment of RA, and abatacept, a modulator of T-cell activation that has been shown to be effective in reducing disease activity, structural joint damage and improving quality of life in patients with RA who had inadequate response to prior methotrexate or anti-TNFα therapy (Laganàet al., 2009; Roll and Tony, 2009).

Peripheral afferent fibres synthesize a diversity of substances that could potentially contribute to hyperalgesia in RA patients. These include glutamate and other excitatory amino acids, neuropeptides such as substance P and calcitonin gene-related peptide, the universal cellular energy source adenosine triphosphate, the diffusible gas nitric oxide, the phospholipid metabolites prostaglandins, and the growth factors neurotrophins (Millan, 1999). Clinical studies have demonstrated increased synovial glutamate levels in patients with active arthritis (McNearney et al., 2000). Glutamate is known to activate two groups of receptors; the metabotropic (mGlu) receptors that are coupled via G-proteins to soluble second messengers, and the ionotropic receptors that are coupled directly to cation-permeable ion channels. At least three major classes and eight subtypes of metabotropic receptors and three ionotropic glutamate receptors have been identified; the latter includes the kainate, AMPA (α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazole propanoic acid), and NMDA (N-methyl-D-aspartate) receptors. There is evidence indicating that NMDA, non-NMDA (AMPA and kainite) and metabotropic glutamate receptor subtypes 1, 4 and 5 (mGlu1, mGlu4 and mGlu5) receptors mediate nociception in the arthritic joint (Sluka et al., 1994; Lawand et al., 1997; Walker et al., 2001; Goudet et al., 2008; Kohara et al., 2007). Inhibition of non-NMDA receptors in the spinal cord suppresses joint swelling in arthritic rat knees (Sluka et al., 1994), but local inhibition of NMDA and non-NMDA receptors did not reduce joint swelling, even though pain-related behaviour was reduced (Lawand et al., 1997).

Our previous work has also indicated neural involvement in the development of inflammatory joint diseases. For example, surgical denervation or chemical denervation of the rat knee joint by high-dose capsaicin (a neurotoxin) was shown to attenuate the development of experimentally induced arthritis (Lam and Ferrell, 1989a; 1991a;). In addition, substance P was found to play a pivotal role in mediating neurogenic inflammation; when administered topically or intra-articularly into rat knees, it produced marked vasodilatation and plasma extravasation (Lam and Ferrell, 1990; Scott et al., 1991; 1992; 1994; Lam et al., 1993). These actions were mimicked by a tachykinin (NK1) receptor agonist [Sar9, Met(O2)11]substance P (Lam and Ferrell, 1991b; Lam and Wong, 1996), which confirmed the involvement of NK1 receptors in these responses. Substance P was found to exacerbate inflammatory responses in rat knees (Lam and Ferrell, 1993; Lam and Wong, 1996), and to accelerate the onset of adjuvant-induced monoarthritis and promote the spread of the disease to contralateral joints (Lam et al., 2004). Furthermore, several substance P antagonists were found to be effective in suppressing inflammatory responses elicited by carrageenan (Lam and Ferrell, 1989b), substance P (Lam et al., 1993) and [Sar9, Met(O2)11]substance P (Lam and Wong, 1996).

Since a large number of mediators are implicated in the development of RA, it is unlikely that the disease can be eradicated by inhibiting the actions of any one group of mediators involved in the disease. It is hypothesized that a better approach for treatment of RA would be to use multiple anti-inflammatory agents simultaneously to accomplish wider and more effective inhibition of the broad spectrum of inflammatory mediators involved. This idea is supported by recent clinical trials, which have shown that treatment with methotrexate plus a fully human TNF soluble receptor etanercept or a new human anti-TNFα monoclonal antibody golimumab produced better disease remission in RA patients compared with those treated with methotrexate alone (Emery et al., 2008; 2009;). In the latter trial, doubling the dose of golimumab in the combined therapy showed no additional benefit, but increased the risk of serious infection and injection-site reactions (Emery et al., 2009). Dexamethasone and other corticosteroids are used in the clinical treatment of RA, but they can only be used short-term because of the toxicities associated with chronic use (Butler et al., 1991; Schacke et al., 2002). Glutamate receptor antagonists are also known to produce sedation and psychotomimetic side effects (Willetts et al., 1990). Combination therapy is expected to reduce the dosages of drugs required to attain anti-arthritic efficacy compared with monotherapy, and hence combination therapy could reduce the occurrence of adverse drug effects. In the present study, we investigated the individual and combined effects of dexamethasone and receptor antagonists of substance P and glutamate in a rat model of arthritis.

Methods

Induction of arthritis

All animal care and experimental protocols were licenced by the Department of Health of Hong Kong and approved by the Animal Experimentation Ethics Committee of the Chinese University of Hong Kong. Sprague-Dawley rats (250–300 g) bred at the Chinese University of Hong Kong were anaesthetised with thiopentone (40 mg·kg−1; i.p.). Arthritis was induced by a single unilateral injection of 125 µL Freund's complete adjuvant (FCA; containing 125 µg Mycobacterium tuberculosis) into synovial cavities of the rat knee; the contralateral knee was injected with 125 µL saline to serve as an internal control. This procedure has been shown to produce joint oedema within 1 day and histological changes from day 3 onwards (Lam et al., 2004). The method has the advantage of avoiding many of the detrimental factors associated with polyarthritic models, that is, severe and extensive disease, systemic illness and profound weight loss, because intra-articularly injected FCA produces a localised monoarthritis in the joint (Lam et al., 2004; 2008;).

General protocol

Monoarthritis was induced in rats as described above. Knee joint allodynia and swelling were measured on day 0 before induction of arthritis (as pre-treatment controls), and on days 1, 2, 3, 4 and 7 after induction of arthritis. Joint hyperaemia and histological changes were assessed only on day 7, as the former is an invasive procedure requiring removal of skin covering the knee joint and the latter involved termination of the animals. The first group of rats acted as control and received FCA injection only; others received drug treatments given at 15 min before induction of arthritis. The following list of drug treatments were given to separate groups of rats: (i) single injection of the NK1 receptor antagonist RP67580 into FCA-treated knees; (ii) single injection of NMDA receptor antagonist (±)-2-amino-7-phosphonoheptanoic acid (AP7) plus non-NMDA receptor antagonist 6-cyano-7- nitroquinoxaline-2,3-dione (CNQX) into FCA-treated knees; (iii) daily oral administration of dexamethasone by gavage; and (iv) daily oral administration of dexamethasone plus single injection of all of the above receptor antagonists in FCA-treated knees. Receptor antagonists were injected into ipsilateral knees in a final volume of 100 µL, and the same volume of vehicle was injected into contralateral knees to act as control. Knee joint allodynia, swelling, hyperaemia, and histological changes were assessed as described below.

Assessment of knee joint allodynia

The method for assessment of mechanical allodynia was modified from that described by Yu et al. (2002). The conscious rat was restrained gently. While the thigh was fixed by holding it with the thumb and the second finger of one hand, the leg was extended by the fingers of the other hand to determine the knee extension angle at which the rat showed struggling behaviour. The extension angle was directly measured using a protractor by holding the thigh at the pivot. Each joint was measured three times at 3 min intervals, and the average of the three was taken as the final value.

Assessment of knee joint swelling

Rat knee joint size was measured as described by Lam et al. (2004). Briefly, the rat was anaesthetized with thiopentone (40 mg·kg−1; i.p.). A digital micrometer (Mitutoyo, Kawasaki, Japan) was placed across the medial aspect of the knee joint holding the skin on either side so that it touches but does not press the skin. The reading on the micrometer was then noted.

Assessment of knee joint hyperaemia

The method of laser Doppler perfusion imaging (LDI) described by Lam and Ferrell (1993) was used to measure blood flow of the rat knee joint. First, the rat was deeply anaesthetized with urethane (2 g·kg−1; i.p.) as judged by an absence of withdrawal reflex when the hind limb was pinched. An ellipse of skin over the knee joint was removed to expose the anteromedial aspect of the joint capsule. Physiological saline (100 µL) was applied onto the exposed joint capsule at 5 min intervals to prevent dehydration prior to commencement of blood flow measurement. Using a laser Doppler perfusion imager (Moor Instruments, Axminster, UK), placed 30 cm above the joint, a helium-neon laser (633 nm) was directed to the tissue to scan the surface of the joint in a rectangular pattern of 3 × 4 cm, which required approximately 30 s. A colour-coded perfusion image was then generated and displayed on a monitor. The actual perfusion (flux) values at each point in the image were stored on disc. These can be retrieved at a later stage for calculation of the mean perfusion within a given area using an image processing software (Moor Instruments). Prior to assessment of knee joint blood flow, systemic blood pressure was monitored for 15 min via a cannula inserted into the carotid artery of the rat.

Assessment of histological changes

The rat was exsanguinated under deep urethane (2 g·kg−1; i.p.) anaesthesia, the knee joints dissected, freed from muscles, and fixed in 10% formalin. The joints were then decalcified in 30 mL 10% formic acid with mild agitation for 8 days. A processing machine (duplex processor, Shandon, Runcorn, UK) was used to dehydrate, clear and infiltrate wax into the joints. With patellae facing upward, the joints were placed in embedding molds filled with molten wax, and then cooled and kept at 4°C overnight. A microtome (RM2125RT, Leica, Nussloch, Germany) was used to cut the joints into 5 µm thick slices at a saggital plan. One in very 20 sections was selected, expanded with 20% ethanol for 10 s, and floated on a water bath at 37°C for 1 min for further expansion. The sections were then mounted on glass slides and kept at 37°C overnight for drying. Next, the glass slides were placed in an oven (Windsor incubator, RA Lamb, Eastbourne, UK) at 70°C for 20 min to dewax, and then hydrated by placing into two changes of 100% alcohol for 5 min each, followed by 95, 85, 70 and 50% alcohol for 3 min each. After being washed with running water for 3 min, the slides were stained with haematoxylin and eosin. Histological analysis was carried out by two (blinded) observers, focusing especially on synovial polymorphonuclear (PMN) cell infiltration, synovial tissue proliferation, and cartilage erosion. Sections of the middle part of the joint were selected, so that two full menisci can be observed on the same slide. Severity of the lesions was classified into four grades: 0 = no change, 1 = mild change, 2 = moderate change, and 3 = marked change.

Statistical analysis

All data are presented as means ± SEM of at least six rats in each group. Knee joint allodynia is expressed as a reduction in knee extension angle that provoked struggling behaviour. Joint swelling is expressed as increase in knee joint size (in mm). Joint hyperaemia is expressed as basal knee joint blood flow (in flux values) taken on the final day of the experiment. Blood pressure data are expressed as changes in mean arterial pressure (mmHg), which were calculated by: mean arterial pressure = diastolic pressure + 1/3 (systolic pressure − diastolic pressure). Histological changes are expressed as an arbitrary scale of severity from 0 to 3. The significance between different treatment groups in time-course figures was analysed by repeated measures two-factor analysis of variance (anova), followed by Bonferroni post hoc test for comparisons of means. Mean values shown in the histograms were compared by paired Wilcoxon test or unpaired Mann–Whitney test, as appropriate. The Statistics Package Prism 5 (Graph Pad Software Inc., San Diego, CA, USA) was used for the analyses. P values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Drug formulation

Thiopentone and urethane were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO, USA) and dissolved in 0.9% saline. RP67580, AP7 and CNQX were purchased from Tocris (Bristol, UK) and dissolved in absolute ethanol, NaOH and 0.9% saline respectively. Subsequent dilutions were made in 0.9% saline. Freund's complete adjuvant was purchased from Abbott (North Chicago, IL, USA) and used directly from the vial without dilution. Evans blue was purchased from BDH (Poole, UK) and dissolved in 0.9% saline. Haematoxylin, eosin and other common chemical reagents were also purchased from BDH. All drug names and receptor nomenclature conform to the British Journal of Pharmacology's Guide to Receptors and Channels (Alexander et al., 2008).

Results

Knee joint allodynia

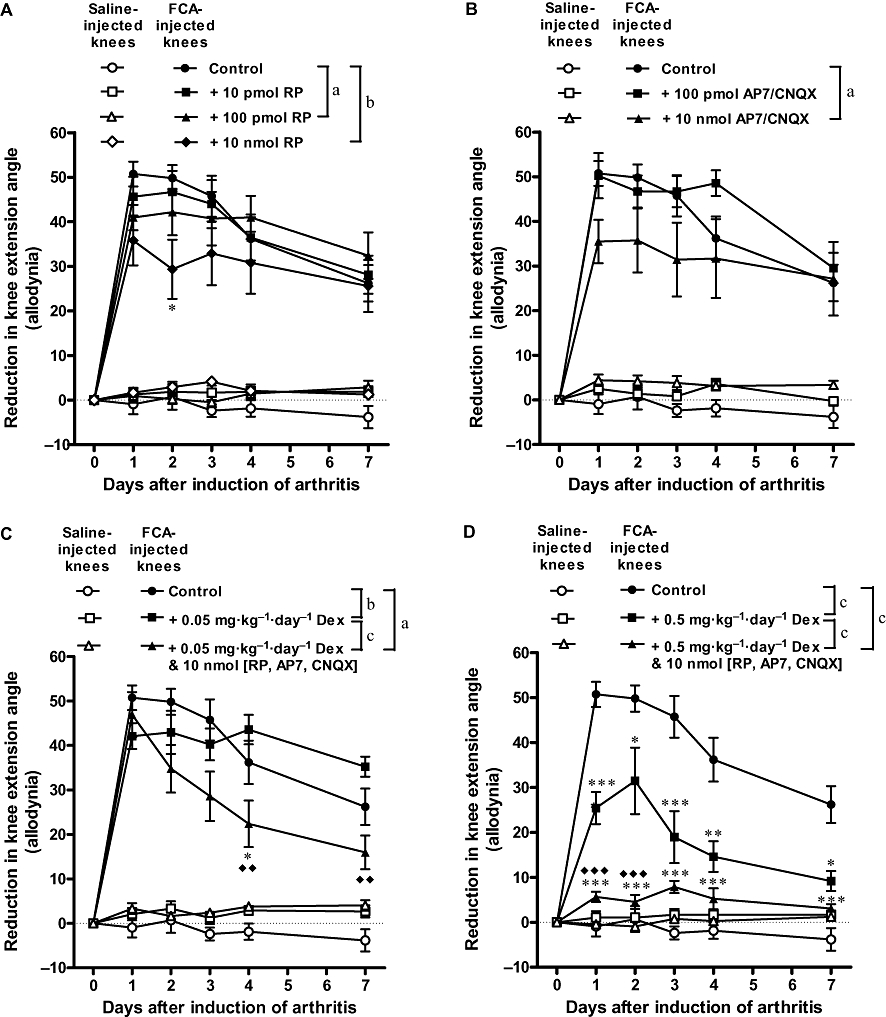

Mechanical allodynia was indicated by a reduction in the extension angle of rat knees that provoked struggling behaviour. As illustrated in Figure 1, rat knees injected with FCA showed a marked reduction in extension angle from day 1 to day 7; peak effect was observed on day 1 with the extension angle being reduced by 51°, indicating development of severe allodynia in the arthritic knees. Single intra-articular administration of the NK1 receptor antagonist RP67580 (10 nmol) produced the most pronounced inhibition of allodynia on day 2; reduction of extension angle was decreased from 50 to 29° (i.e. 42% inhibition). Similarly, single intra-articular administration of the NMDA receptor antagonist AP7 (10 nmol) plus the non-NMDA receptor CNQX (10 nmol) inhibited allodynia maximally on day 2; reduction of extension angle was decreased from 50 to 36° (i.e. 28% inhibition). The effects of these receptor antagonists had subsided by day 7. Daily oral administration of a low dose of dexamethasone (0.05 mg·kg−1) did not reduce allodynia, but when combined with all of the receptor antagonists, the reduction of extension angle was decreased from 50 to 35° (30% inhibition) on day 2 and decreased from 26 to 16° (38% inhibition) on day 7. Daily oral administration of a high dose of dexamethasone (0.5 mg·kg−1) produced the most prominent and sustained inhibition of allodynia; reduction of extension angle was decreased from 51 to 25° (51% inhibition) on day 1 and decreased from 26 to 9° (65% inhibition) on day 7. When the high dose of dexamethasone was combined with all of the receptor antagonists, reduction of extension angle was decreased from 51 to 6° (88% inhibition) on day 1 and decreased from 26 to 3° (88% inhibition) on day 7.

Figure 1.

Individual and combined effects of antagonists of substance P receptors (A), glutamate receptors (B) and dexamethasone (C and D) on knee joint allodynia of Freund's complete adjuvant (FCA)-induced arthritic rats. Combining dexamethasone with the receptor antagonists produced better inhibition of allodynia than dexamethasone alone. Bonferroni post hoc test: *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 (significantly different from FCA alone); ♦♦P < 0.01, ♦♦♦P < 0.001 (significantly different from FCA + Dex). aP < 0.05, bP < 0.01, cP < 0.001 (two-factor anova). n≥ 7. Dex, dexamethasone; RP, RP67580.

Knee joint swelling

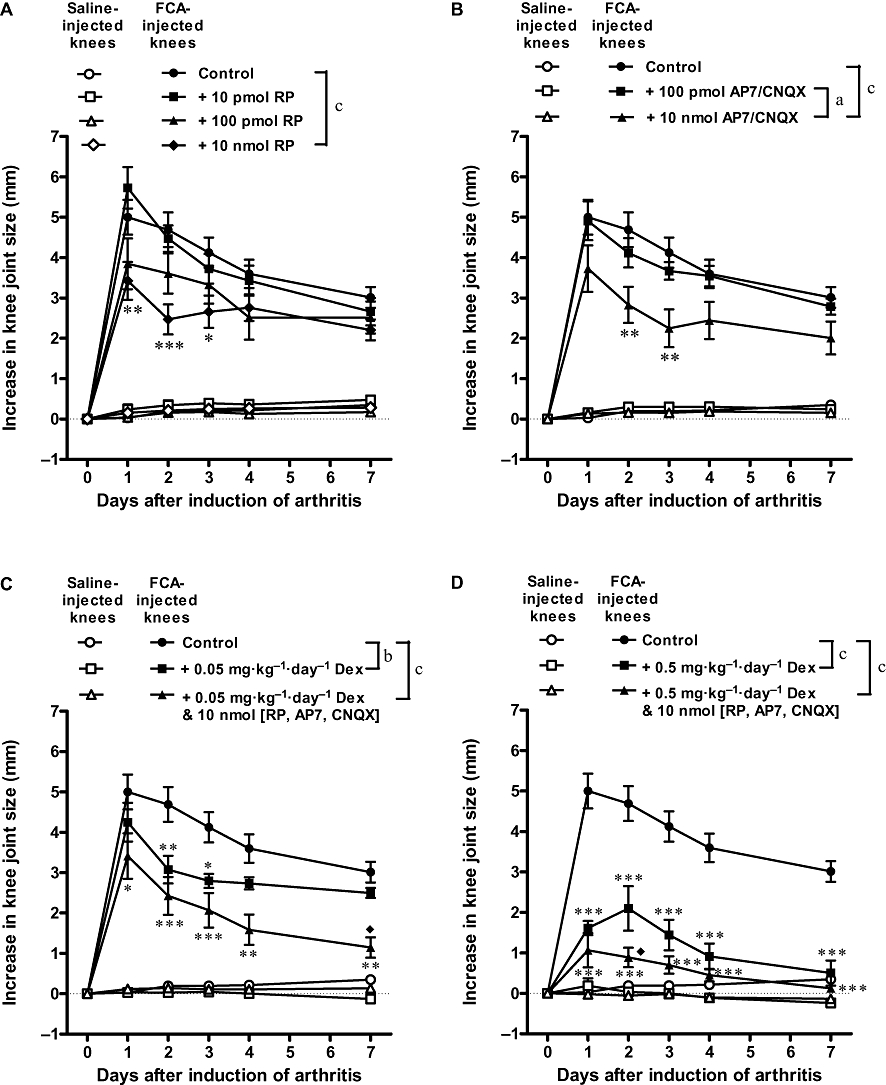

Knee joint swelling was indicated by an increase in knee joint size. As illustrated in Figure 2, rat knees injected with FCA showed a marked increase in joint size from day 1 to day 7; peak effect was observed on day 1 with a 5.0 mm increase, indicating development of severe swelling in the arthritic knees. Single intra-articular administration of the NK1 receptor antagonist RP67580 (10 nmol) produced the most pronounced inhibition of joint swelling on day 2; increase in knee joint size was reduced from 4.7 to 2.5 mm (i.e. 47% inhibition), and reduced from 3.0 to 2.2 mm (27% inhibition) on day 7. Similarly, single intra-articular administration of the NMDA receptor antagonist AP7 (10 nmol) plus the non-NMDA receptor CNQX (10 nmol) inhibited allodynia maximally on day 2; increase in knee joint size was reduced from 4.7 to 2.8 mm (i.e. 40% inhibition) and reduced from 3.0 to 2.0 mm (33% inhibition) on day 7. Daily oral administration of a low dose of dexamethasone (0.05 mg·kg−1) also produced the most pronounced inhibition of joint swelling on day 2; increase in knee joint size was reduced from 4.7 to 3.1 mm (34% inhibition) and reduced from 3.0 to 2.5 mm (17% inhibition) on day 7. When the low-dose dexamethasone was combined with all of the receptor antagonists, the increase in knee joint size was reduced progressively, from 5.0 to 3.4 mm (32% inhibition) on day 1 and from 3.0 to 1.1 mm (63% inhibition) on day 7. Daily oral administration of a high-dose dexamethasone (0.5 mg·kg−1) produced a more prominent and sustained inhibition of joint swelling; increase in knee joint size was reduced from 5.0 to 1.6 mm (68% inhibition) on day 1, and reduced from 3.0 to 0.5 mm (83% inhibition) on day 7. When the high dose of dexamethasone was combined with all of the receptor antagonists, the increase in knee joint size was reduced progressively, from 5.0 to 1.1 mm (77% inhibition) on day 1 and from 3.0 to 0.1 mm (97% inhibition) on day 7.

Figure 2.

Individual and combined effects of antagonists of substance P receptors (A), glutamate receptors (B), and dexamethasone (C and D) on knee joint swelling of Freund's complete adjuvant (FCA)-induced arthritic rats. Combining dexamethasone with the receptor antagonists produced slightly better inhibition of joint swelling than dexamethasone alone. Bonferroni post hoc test: *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 (significantly different from FCA alone); ♦P < 0.05 (significantly different from FCA + Dex). aP < 0.05, bP < 0.01, cP < 0.001 (two-factor anova). n≥ 7. Dex, dexamethasone; RP, RP67580.

Knee joint hyperaemia

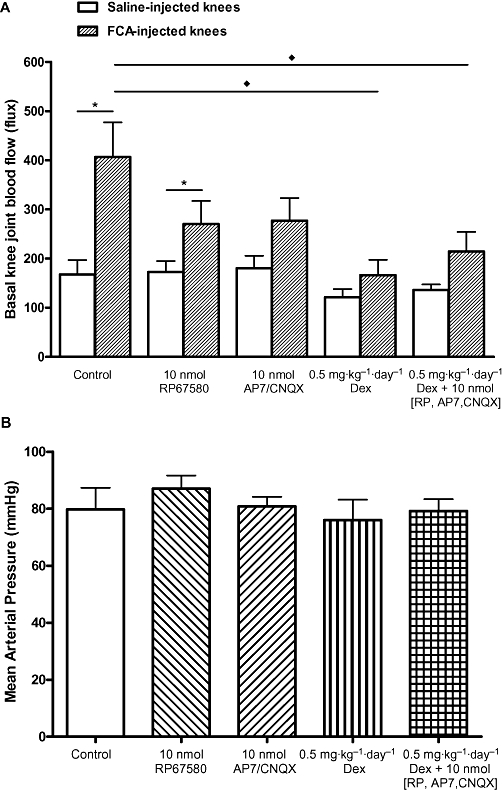

Hyperaemia was indicated by an increase in basal knee joint blood flow measured on day 7 after induction of FCA. As illustrated in Figure 3A, FCA-injected knees showed a marked increase in basal blood flow compared with contralateral saline-injected (control) knees, 406 versus 168 flux (i.e. 142% increase), indicating the presence of marked hyperaemia in the arthritic knees. A single intra-articular injection of RP67580 (10 nmol) reduced blood flow in the FCA-injected knees to 270 flux (i.e. 33% decrease), and AP7 plus CNQX (10 nmol) reduced it to 277 flux (i.e. 32% decrease), but these changes were not significant (P > 0.05). Whereas dexamethasone (0.5 mg·kg−1·day−1) treatment alone, or combined with all of the receptor antagonists, reduced blood flow in the FCA-injected knees to 166 flux (i.e. 59% decrease) and 214 flux (i.e. 47% decrease) respectively (P < 0.05 for both).

Figure 3.

Individual and combined effects of antagonists of substance P receptors, glutamate receptors and dexamethasone on knee joint blood flow (A) and blood pressure (B) of Freund's complete adjuvant (FCA)-induced arthritic rats. Dexamethasone produced the most pronounced inhibition of FCA-induced hyperaemia. All drug treatments had no significant effect on blood pressure. Significance level: *P < 0.05 (paired Wilcoxon test); ♦P < 0.05 (unpaired Mann–Whitney test). n≥ 6. Dex, dexamethasone; RP, RP67580.

All these drug treatments did not significantly affect mean arterial pressure compared with control (Figure 3B; P > 0.05 for all).

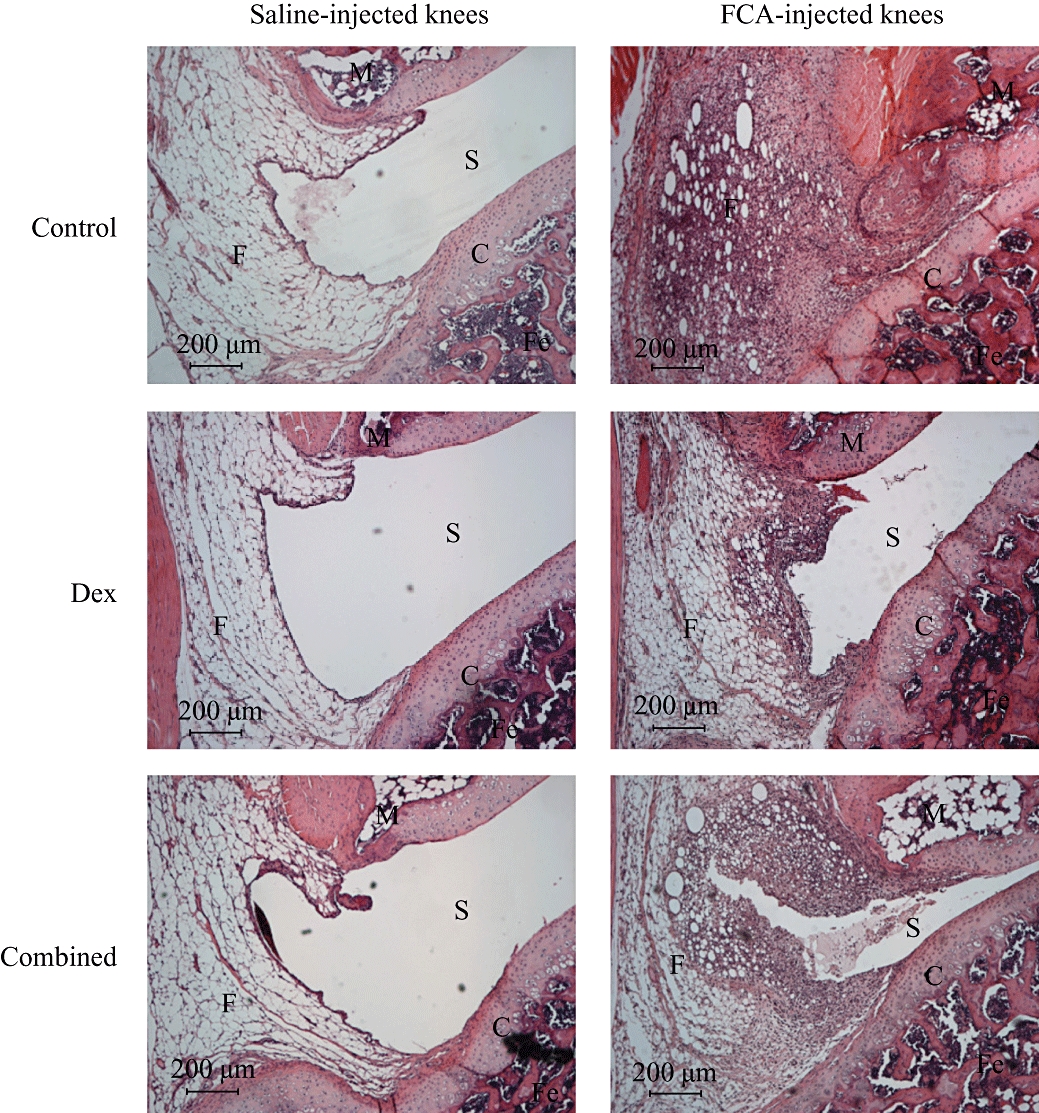

Histological changes

Three parameters of histological changes were assessed, namely, the level of cell infiltration, tissue proliferation and cartilage erosion in rat knee joints on day 7 after induction of arthritis. As illustrated in Figures 4 and 5, FCA-injected knees showed marked increases in cell infiltration, tissue proliferation and cartilage erosion compared with contralateral saline-injected (control) knees (P= 0.002–<0.001), indicating the occurrence of ipsilateral chronic histological damages in this monoarthritis model. Treatment with RP67580 (10 nmol) or AP7 plus CNQX (10 nmol) had no effect on these changes, whereas, treatment with dexamethasone (0.5 mg·kg−1·day−1) significantly reduced cell infiltration, tissue proliferation and cartilage erosion (P < 0.05–P < 0.001). Combining the dexamethasone treatment with an injection of all of the receptor antagonists slightly augmented these inhibitory effects, but these improvements were not significant compared with the effects produced by dexamethasone treatment alone (P > 0.05 for all).

Figure 4.

Micrographs showing typical effects of dexamethasone alone and dexamethasone combined with substance P and glutamate receptor antagonists on histological changes in Freund's complete adjuvant (FCA)-induced arthritic rat knees. FCA-injected knee showed marked cell infiltration, tissue proliferation and cartilage erosion compared with contralateral saline-injected knee. Dexamethasone and the combined treatment produced similar inhibition on these histological changes. C, cartilage; Combined, dexamethasone (0.5 mg·kg−1·day−1) plus 10 nmol of RP67580, AP7 and CNQX; Dex, dexamethasone (0.5 mg·kg−1·day−1); F, fat cells; Fe, femur; M, meniscus; S, synovial space.

Figure 5.

Individual and combined effects of receptor antagonists of substance P, glutamate and dexamethasone on cell infiltrate (A), tissue proliferation (B) and cartilage erosion (C) in Freund's complete adjuvant (FCA)-induced arthritic rat knees. The substance P antagonist had no effect, glutamate receptor antagonists slightly reduced tissue proliferation and dexamethasone reduced all histological changes in the arthritic knees, but its effect was not significantly altered by combined treatment with the receptor antagonists. Data are shown as histological changes in an arbitrary scale of severity: 0 = no change; 1 = mild; 2 = moderate; 3 = marked. Significance level: *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 (paired Wilcoxon test); ♦P < 0.05, ♦♦P < 0.01, ♦♦♦P < 0.001 (unpaired Mann–Whitney test). n≥ 7. Dex, dexamethasone; RP, RP67580.

Discussion and conclusions

Much evidence suggests an important role for the nervous system in the pathogenesis of peripheral inflammatory conditions such as arthritis. Levine et al. (1985) first proposed that there is a neurogenic component in inflammatory arthritis that contributes ipsilaterally to the severity of inflammation and also causes contralateral spread of inflammation. Contralateral phenotype changes are, however, not a consistent finding in unilateral arthritis. Donaldson et al. (1993) observed that contralateral joint involvement in adjuvant-induced arthritis is an inflammation-dependent observation, with more severe inflammation resulting in contralateral joint involvement, and less severe inflammation remaining unilateral. Therefore, the occurrence and severity of contralateral effects will vary depending on the model of inflammation used, and in the sensitivity of experimental species or strains to the inflammatory stimuli. In the present study, rat knee joints were induced with monoarthritis by unilateral intra-articular injection of FCA; arthritis symptoms, including joint allodynia, swelling, hyperaemia, and histological changes, were found to occur solely at the ipsilateral FCA-injected knees. This concurs with our previous findings (Lam et al., 2004; 2008;), and confirms that it is a useful monoarthritis model for studies of local changes in arthritic joints, as it is devoid of contralateral or systemic effects that could complicate the interpretation of data.

FCA-induced arthritis in rats and collagen-induced arthritis in rats and mice were found to be the three most commonly used animal models to evaluate approved, pending RA therapies, and compounds that were discontinued during phase II and phase III clinical trials (Hegen et al., 2008). These animal models have excellent track records for predicting activity and toxicity (at high doses of various agents) in humans, and are recommended for use in rapid generation of preclinical efficacy/toxicity data to facilitate entry into a clinical trial (Bendele, 2001). The mouse model has an additional advantage, in that there are extensive immunological and genetic tools available to manipulate the disease in this species (Phadke et al., 1985). On the other hand, as highlighted above, our current FCA-induced arthritis model has the advantage of producing discrete monoarthritis in rat knees, and it does not cause systemic complications, rendering it a good model for studies of local changes in arthritic joints.

Evidence from animal studies indicates that substance P and glutamate are co-localized in a subset of sensory fibres (Battaglia and Rustioni, 1988), and these two neurotransmitters are involved in pain processing in the spinal cord, as well as nociception by peripheral nerve endings in arthritic joints (Millan, 1999; Hill, 2000; Hong et al., 2002; Zhang et al., 2003). Substance P is a member of the tachykinin family of peptides that are known to interact with three major receptor types designated as NK1, NK2 and NK3 receptors (Burcher et al., 1991). Our previous studies suggest many of the actions of substance P in the rat knee joint are mediated by NK1 receptors (Ferrell and Lam, 1996). NK1 receptors are thought to play a role in the induction, but not maintenance of arthritic pain (Tsao et al., 1997). Accordingly, in the present study, a NK1 receptor antagonist RP67580 was shown to attenuate joint allodynia and swelling during the early days of arthritis development, but it did not affect the histological changes that occurred at a later stage of this disease. Moreover, we have previously demonstrated that injection of substance P into arthritic rat knees exacerbated the early symptoms of arthritis, but had no influence on histological changes (Lam et al., 2004). The pro-inflammatory effects of substance P probably involved release of mediators from mast cells (Mazurek et al., 1981; Lam and Ferrell, 1990), secretion of PGE2 and collagenase from synoviocytes (Lotz et al., 1987), stimulation of secretion of IL-1-like activity from macrophages (Kimball et al., 1988) and activation of the immune system (Neveu and Le Moal, 1990).

There are several possible sources of glutamate in peripheral tissues, including the release from peripheral terminals of primary afferent neurones (Coggeshall and Carlton, 1998; Omote et al., 1998; Lawand et al., 2000). Ionotropic and metabotropic glutamate receptor subunit mRNA was also found to be expressed in the patella, fat pad and meniscus of the rat knee and in human cartilage (Flood et al., 2007). In synoviocytes from RA patients, inhibition of NMDA receptors increased pro-metalloproteinase-2 (proMMP-2) release, and inhibition of the non-NMDA (AMPA and kainite) receptors reduced IL-6 release (Flood et al., 2007). Thus, the elevated glutamate concentration in synovial fluids that occurs in human RA (McNearney et al., 2000) and in animal models of osteoarthritis (Jean et al., 2005) and inflammatory arthritis (McNearney et al., 2004) may influence IL-6 and proMMP-2 release into the synovial joint, and contribute to disease progression. In addition, NMDA, non-NMDA (AMPA and kainite) and metabotropic glutamate receptor subtypes 1, 4 and 5 (mGlu1, mGlu4 and mGlu5) were shown to mediate nociception in the arthritic joint (Sluka et al., 1994; Lawand et al., 1997; Walker et al., 2001; Goudet et al., 2008; Kohara et al., 2007).

We have investigated the combined effects of a NMDA receptor antagonist (AP7) and a non-NMDA receptor antagonist (CNQX) in the present study. In resemblance to those produced by the NK1 receptor antagonist, co-administration of AP7 and CNQX inhibited allodynia and swelling during the early development of arthritis, but they had no influence on histological changes that occurred at a later stage of the disease. Previous studies showed that spinal administration of CNQX in rats 4 h after initiation of arthritis significantly reduced joint inflammation and hyperalgesia (Sluka et al., 1994), and inflammation-induced hyperexcitability of neurones in the deep dorsal horn of rats was reduced by i.v. injections of NMDA and non-NMDA receptor antagonists applied during or up to 103 min after induction of arthritis (Neugebauer et al., 1993). Taken together, these data suggest glutamate, like substance P, plays a part in the early development of arthritis and spinal pain transmission. Nonetheless, it should be noted that antagonists of substance P and glutamate receptors were given by single intra-articular injection prior to induction of arthritis in the present study. Hence, their long-term benefit on arthritis cannot be excluded until it is proved that repeated administration of these antagonists cannot extend their potencies and duration of inhibition on arthritis development.

It is difficult to predict which transmitter might be the most important in a particular disease state, and only if one of the released substances has a dominant role will the specific pharmacological blockade of its effects offer adequate therapeutic efficacy. The broad spectrum of activities of glucocorticoids has made them one of the most potent and widely used anti-inflammatory and immune-modulatory drugs. Accordingly, dexamethasone, a potent glucocorticoid, was shown to suppress oedema and the expression of nuclear factor-κB (NFκB) in the hind paw of adjuvant-induced arthritic rats (Tsao et al., 1997). NFκB is known to play a very important role in the inducible regulation of a variety of genes involved in the inflammatory process; these include TNF-α, IL-1 and IL-6 (Baeuerle and Henkel, 1994). In agreement with these findings, daily oral administration of dexamethasone was found to produce marked inhibition of all arthritis symptoms, and it was proven to be the most effective anti-arthritic agent of all the drugs tested in the present study.

Clinically, long-term use of a high dose of dexamethasone is not desirable because glucocorticoids are prone to produce many side effects, such as metabolic disturbances and iatrogenic Cushing's syndrome (Schacke et al., 2002). Glutamate receptor antagonists are also known to produce sedation and psychotomimetic side effects (Willetts et al., 1990). It is suspected that combination therapy would minimize their side effects by reducing the doses of these drugs necessary to attain adequate anti-arthritic actions. For this purpose, the anti-arthritic efficacy of dexamethasone alone was compared with that of dexamethasone combined with the NK1 and glutamate receptor antagonists. These receptor antagonists had no effect on histological changes on their own, and therefore when combined with dexamethasone, they did not improve the inhibitory actions of dexamethasone on these parameters. On the other hand, the combined treatment showed better analgesia and reduction of joint swelling than those produced by the individual drugs on their own.

Both the substance P and glutamate receptor antagonists were found to have no significant inhibitory effect on FCA-induced hyperaemia, whereas dexamethasone alone or combined with these receptor antagonists produced marked inhibition. The low efficacy of substance P and glutamate receptors is not surprising, since these drugs were given by single intra-articular injection prior to induction of arthritis, and knee joint hyperaemia was determined on day 7 after arthritis induction whereas dexamethasone was given daily as an oral administration. Furthermore, the vasodilator actions of substance P and other tachykinins are known to be transient and tachyphylactic (Lam and Ferrell, 1993; Lam and Wong, 1996). This suggests the contribution of substance P to joint hyperaemia might be more significant during the early stage of the disease. Systemic blood pressure is not a confounding factor in the present measurements of knee joint blood flow, as all the above drug treatments did not produce a significant change in blood pressure.

In conclusion, the present studies confirm that substance P and glutamate contribute to joint pain and swelling during the early development of arthritis. These symptoms can be reduced by substance P and glutamate receptor antagonists. Dexamethasone suppressed all arthritic symptoms, including the chronic histological changes. More importantly, combined treatment with dexamethasone and receptor antagonists of substance P and glutamate improved their efficacies in relieving pain and swelling in arthritic rat knees. These data suggest that improving the efficacy of glucocorticoids by blocking substance P and glutamate receptors constitutes another clinically relevant concept for the management of arthritis.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Li Ka Shing Institute of Health Sciences and by a Direct Grant for Research of the Chinese University of Hong Kong.

Glossary

Abbreviations:

- AMPA

α-amino-3-dihydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazole propanoic acid

- AP7

(±)-2-amino-7-phosphonoheptanoic acid

- CNQX

6-cyano-7- nitroquinoxaline-2,3-dione

- FCA

Freund's complete adjuvant

- IFN-γ

interferon-γ

- IL

interleukin

- LDI

laser Doppler perfusion imaging

- NFκB

nuclear factor-κB

- NK1

neurokinin-1

- NMDA

N-methyl D-aspartate

- PMN

polymorphonuclear

- proMMP-2

pro-metalloproteinase-2

- RA

rheumatoid arthritis

- TNF-α

tumour necrosis factor-α

Conflict of interest

None.

References

- Alexander SPH, Mathie A, Peters JA. Guide to Receptors and Channels (GRAC), 3rd edn. Br J Pharmacol. 2008;153(Suppl 2):S1–S209. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0707746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arend WP. The pathophysiology and treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1997;40:595–597. doi: 10.1002/art.1780400402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baeuerle PA, Henkel T. Function and activation of NF-kappa B in the immune system. Annu Rev Immunol. 1994;12:141–179. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.12.040194.001041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Battaglia G, Rustioni A. Coexistence of glutamate and substance P in dorsal root ganglion neurons of the rat and monkey. J Comp Neurol. 1988;277:302–312. doi: 10.1002/cne.902770210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bendele AM. Animal models of rheumatoid arthritis. J Musculoskelet Neuron Interact. 2001;1:377–385. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burcher E, Mussap CJ, Geraghty DP, McClure-Sharp JM, Watkins DJ. Concepts in characterization of tachykinin receptors. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1991;632:123–136. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1991.tb33101.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler RC, Davie MWJ, Worsfold M, Sharp CA. Bone mineral content in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: relationship to low-dose steroid therapy. Br J Rheumatol. 1991;30:86–90. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/30.2.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coggeshall RE, Carlton SM. Ultrastructural analysis of NMDA, AMPA, and kainate receptors on unmyelinated and myelinated axons in the periphery. J Comp Neurol. 1998;391:78–86. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9861(19980202)391:1<78::aid-cne7>3.3.co;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dayer J-M, de Rochemonteix B, Burrus B, Demczuk S, Dinarello CA. Human recombinant interleukin 1 stimulates collagenase and prostaglandin E2 production by human synovial cells. J Clin Invest. 1986;77:645–648. doi: 10.1172/JCI112350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donaldson LF, Seckl JR, McQueen DS. A discrete adjuvant-induced monoarthritis in the rat: effect of adjuvant dose. J Neurosci Methods. 1993;49:5–10. doi: 10.1016/0165-0270(93)90103-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emery P, Breedveld FC, Hall S, Durez P, Chang DJ, Robertson D, et al. Comparison of methotrexate monotherapy with a combination of methotrexate and etanercept in active, early, moderate to severe rheumatoid arthritis (COMET): a randomised, double-blind, parallel treatment trial. Lancet. 2008;372:375–382. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61000-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emery P, Fleischmann RM, Moreland LW, Hsia EC, Strusberg I, Durez P, et al. Golimumab, a human anti-tumor necrosis factor α monoclonal antibody, injected subcutaneously every four weeks in methotrexate-naïve patients with active rheumatopid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;60:2271–2283. doi: 10.1002/art.24638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldmann M, Brennan FM, Maini RN. Role of cytokines in rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rev Immunol. 1996;14:397–440. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.14.1.397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrell WR, Lam FY. Sensory neuropeptides in arthritis. In: Geppetti P, Holzer P, editors. Neurogenic Inflammation. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; 1996. pp. 211–227. [Google Scholar]

- Flood S, Parri R, Williams A, Duance V, Mason D. Modulation of interleukin-6 and matrix metalloproteinase 2 expression in human fibroblast-like synoviocytes by functional ionotropic glutamate receptors. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56:2523–2534. doi: 10.1002/art.22829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goudet C, Chapuy E, Alloui A, Acher F, Pin JP, Eschalier A. Group III metabotropic glutamate receptors inhibit hyperalgesia in animal models of inflammation and neuropathic pain. Pain. 2008;137:112–114. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2007.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hegen M, Keith JC, Collins M, Nickerson-Nutter CL. Utility of animal models for identitfication of potential therapeutics for rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2008;67:1505–1515. doi: 10.1136/ard.2007.076430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill R. NK1 (substance P) receptor antagonists – why are they not analgesic in humans? Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2000;21:244–246. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(00)01502-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong SK, Han JS, Min SS, Hwang JM, Kim YI, Na HS, et al. Local neurokinin-1 receptor in the knee joint contributes to the induction, but not maintenance, of arthritic pain in the rat. Neurosci Lett. 2002;322:21–24. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(02)00070-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jean YH, Wen ZH, Chang YC, Huang GS, Lee HS, Hsieh SP, et al. Increased concentrations of neuron-excitatory amino acids in rat anteriror cruciate ligament-transected knee joint dialysates: a microdialysis study. J Orthop Res. 2005;23:569–575. doi: 10.1016/j.orthres.2004.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimball ES, Perisco FJ, Vaught JL. Substance P, neurokinin A and neurokinin B induce generation of IL-1-like activity in P338D1 cells. J Immun. 1988;141:3564–3569. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohara A, Nagakura Y, Kiso T, Toya T, Watabiki T, Tamura S, et al. Antinociceptive profile of a selective metabrotropic glutamate receptor 1 antagonist YM-230888 in chronic pain rodent models. Eur J Pharmacol. 2007;571:8–16. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2007.05.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laganà B, Vinciguerra M, D'Amelio R. Modulation of T-cell co-stimulation in rheumatoid arthritis: clinical experience with abatcept. Clin Drug Investig. 2009;29:185–202. doi: 10.2165/00044011-200929030-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam FFY, Wong HHL, Ng ESK. Time course and substance P effects on the vascular and morphological changes in adjuvant-induced monoarthritic rats. Int Immunopharmacol. 2004;4:299–310. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2004.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam FFY, Ko IWM, Ng ESK, Tam LS, Leung PC, Li EKM. Analgesic and anti-arthritic effects of Lingzhi and San Miao San supplementation in a rat model of arthritis induced by Freund's complete adjuvant. J Ethnopharmacol. 2008;120:44–50. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2008.07.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam FY, Ferrell WR. Capsaicin suppresses substance P-induced joint inflammation in the rat. Neurosci Lett. 1989a;105:155–158. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(89)90028-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam FY, Ferrell WR. Inhibition of carrageenan induced inflammation in the rat knee joint by substance P antagonist. Ann Rheum Dis. 1989b;48:928–932. doi: 10.1136/ard.48.11.928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam FY, Ferrell WR. Mediators of substance P-induced inflammation in the rat knee joint. Agents Actions. 1990;31:298–307. doi: 10.1007/BF01997623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam FY, Ferrell WR. Neurogenic component of different models of acute inflammation in the rat knee joint. Ann Rheum Dis. 1991a;50:747–751. doi: 10.1136/ard.50.11.747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam FY, Ferrell WR. Specific neurokinin receptors mediate plasma extravasation in the rat knee joint. Br J Pharmacol. 1991b;103:1263–1267. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1991.tb12334.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam FY, Ferrell WR. Acute inflammation in the rat knee joint attenuates sympathetic vasoconstriction but enhances neuropeptide-mediated vasodilation assessed by laser doppler perfusion imaging. Neuroscience. 1993;52:443–449. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(93)90170-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam FY, Wong MC. Characterization of tachykinin receptors mediating plasma extravasation and vasodilatation in normal and acutely inflamed knee joints of the rat. Br J Pharmacol. 1996;118:2107–2114. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1996.tb15650.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam FY, Ferrell WR, Scott DT. Substance P-induced inflammation in the rat knee joint is mediated by neurokinin 1 (NK1) receptors. Regul Pept. 1993;46:198–201. doi: 10.1016/0167-0115(93)90032-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawand NB, Willis WD, Westlund KN. Excitatory amino acid receptor involvement in peripheral nociceptive transmission in rats. Eur J Pharmacol. 1997;324:169–177. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(97)00072-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawand NB, McNearney YT, Westlund KN. Amino acid release into the knee joint: key role in nociception and inflammation. Pain. 2000;86:69–74. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(99)00311-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine T, Moskowitz MA, Basbaum AI. The contribution of neurogenic inflammation in experimental arthritis. J Immunol. 1985;135:843s–847s. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipsky PE, Davis LS, Cush JJ, Oppenheimer-Marks N. The role of cytokines in the pathogenesis of rheumatoid arthritis. Springer Semin Immunopathol. 1989;11:123–162. doi: 10.1007/BF00197186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lotz M, Carson DA, Vaught JL. Substance P activation of rheumatoid synoviocytes: neural pathway in pathogenesis of arthritis. Science. 1987;235:893–896. doi: 10.1126/science.2433770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNearney YT, Speegle D, Lawand N, Lisse J, Westlund KN. Excitatory amino acid profiles of synovial fluid from patients with arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2000;27:739–745. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNearney YT, Baethge BA, Cao S, Alam R, Lisse JR, Westlund KN. Excitatory amino acids, TNF-α, and chemokine levels in synovial fluids of patients with active arthropathies. Clin Exp Immunol. 2004;137:621–627. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2004.02563.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Majithia V, Geraci SA. Rheumatoid arthritis: diagnosis and management. Am J Med. 2007;120:936–939. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2007.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazurek N, Pecht I, Teichbury VI, Blumbery S. The role of the N-terminal tetrapeptide in the histamine-releasing action of substance P. Neuropharmacol. 1981;20:1025–1027. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(81)90091-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millan MJ. The induction of pain: an integrative review. Prog Neurobiol. 1999;57:1–164. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(98)00048-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagasawa H, Takeuchi T. Effect of the inhibition of joint destruction in RA by TNF-blocking agents. Clin Calcium. 2009;19:416–424. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neugebauer V, Lucke T, Schaible HG. N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) and non-NMDA receptor antagonists block the hyperexcitability of dorsal horn neurons during development of acute arthritis in rat's knee joint. J Neurophysiol. 1993;70:1365–1377. doi: 10.1152/jn.1993.70.4.1365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neveu PJ, Le Moal M. Physiological basis for neuroimmunomodulation. Fundam Clin Pharmacol. 1990;4:281–305. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-8206.1990.tb00496.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Omote K, Kawamata T, Kawamata M, Namiki A. Formalin-induced release of excitatory amino acids in the skin of the rat hindpaw. Brain Res. 1998;787:161–164. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(97)01568-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phadke K, Fouts RL, Parrish JE, Butler LD. Evaulation of the effects of various anti-arthritic drugs on Type II collagen-induced mouse arthritic model. Immunopharmacol. 1985;10:51–60. doi: 10.1016/0162-3109(85)90059-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roll P, Tony HP. Anti-CD20 in rheumatoid arthritis. Z Rheumatol. 2009;68:370–379. doi: 10.1007/s00393-009-0437-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schacke H, Docke WD, Asadullah K. Mechanisms involved in the side effects of glucocorticoids. Pharmacol Ther. 2002;96:23–43. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7258(02)00297-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott DT, Lam FY, Ferrell WR. Time course of substance P-induced protein extravasation in the rat knee joint measured by micro-turbidimetry. Neurosci Lett. 1991;129:74–76. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(91)90723-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott DT, Lam FY, Ferrell WR. Acute inflammation enhances substance P-induced plasma protein extravasation in the rat knee joint. Regul Pept. 1992;39:227–235. doi: 10.1016/0167-0115(92)90543-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott DT, Lam FY, Ferrell WR. Acute joint inflammation – mechanisms and mediators. Gen Pharmacol. 1994;25:1285–1296. doi: 10.1016/0306-3623(94)90151-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sluka KA, Jordan HH, Westlund KN. Reduction in joint swelling and hyperalgesia following post-treatment with a non-NMDA glutamate receptor antagonist. Pain. 1994;59:95–100. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(94)90052-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsao PW, Susuki T, Totsuka R, Murata T, Takagi T, Ohmachi Y, et al. The effect of dexamethasone on the expression of activated NF-kappa B in adjuvant arthritis. Clin Immunol Immunopathol. 1997;83:173–178. doi: 10.1006/clin.1997.4333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker K, Reeve A, Bowes M, Winter J, Wotherspoon G, Davis A, et al. mGlu5 receptors and nociceptive function II. mGlu5 receptors functionally expressed on peripheral sensory neurones mediate inflammatory hyperalgesia. Neuropharmacology. 2001;40:10–19. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(00)00114-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willetts J, Balster RL, Leander JD. The behavioral pharmacology of NMDA receptor antagonists. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 1990;11:423–428. doi: 10.1016/0165-6147(90)90150-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu YC, Koo ST, Kim CH, Lyu Y, Grady JJ, Chung JM. Two variables that can be used as pain indices in experimental animal models of arthritis. J Neurosci Methods. 2002;115:107–113. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0270(02)00011-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang GH, Yoon YW, Lee KS, Min SS, Hong SK, Park JY, et al. The glutamatergic N-methyl-D-aspartate and non-N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors in the joint contribute to the induction, but not maintenance, of arthritic pain in rats. Neurosci Lett. 2003;351:177–180. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2003.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]