Abstract

Study Design

Cross-sectional study.

Objectives

To determine whether the distribution of those with and without dynamic knee stability after anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) rupture differs by age, gender, and contact versus noncontact injury mechanisms.

Background

There is a differential return to preinjury activities after ACL rupture. It is unknown if there are specific patient groups that are more or less likely to experience good dynamic knee stability after ACL rupture.

Methods and Measures

The study sample consisted of 345 consecutive, highly active patients with complete, isolated ACL insufficiency. Based on the results of a screening examination, patients were categorized as having either good (potential coper) or poor (noncoper) dynamic knee stability. Descriptive and chi-square statistics were calculated to describe patient characteristics and identify the proportion of potential copers and noncopers based on age, gender, and injury mechanism.

Results

The groups with the greatest proportion of noncopers were women (P = .002), mid-aged adults (35-44 years) (P<.001), and individuals who sustained a noncontact ACL injury (P = .011).

Conclusions

Women who sustain an ACL rupture and those who sustain an ACL rupture via a noncontact mechanism frequently experience dynamic knee instability. A profile of demographic characteristics of those most likely to experience knee instability after ACL rupture may facilitate improved patient outcomes.

Level Of Evidence

Prognosis, Level 2b.

Keywords: clinical research, joint instability, knee

The anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) is the most frequently injured ligament in the knee and is often injured during athletic activities.3,20 The majority of individuals cannot return to high-level athletic activities after ACL rupture because of continued episodes of knee giving-way (noncopers).5,8 Consequently, early surgical intervention is the preferred treatment for the majority of orthopaedic surgeons in the United States.7,21 There are, however, a small percentage of individuals with a complete ACL tear who are able to successfully compensate for the absence of the ACL. Copers are operationally defined as individuals who have asymptomatically returned to all preinjury activities, including sports, for at least 1 year.5,29 It is a significant clinical challenge to identify individuals who have the potential to compensate well for ACL deficiency early after injury, when patient management decisions are often made.

A screening examination has been developed that discriminates between noncopers and individuals with good potential to cope nonoperatively with ACL deficiency (potential copers).9 The screening examination9 consists of a battery of clinical tests and measures that capture dynamic knee stability (ie, the ability of a joint to remain stable when subjected to rapidly changing loads during activities)30 and may be administered early after injury. Fitzgerald9 validated the screening examination with a series of 93 consecutive patients with acute, isolated ACL rupture. Thirty-nine patients (42%) met the criteria for classification as appropriate rehabilitation candidates (potential copers). Of the 28 potential copers who elected nonoperative management, 79% were able to return to preinjury activity levels for a 6-month period without experiencing further giving-way episodes, reduction in activity status, or extension of the original knee injury.9 These results indicate that the screening examination is an efective clinical tool for identifying highly active patients with different levels of dynamic knee stability early after ACL rupture.

Neuromuscular system responses after ACL rupture dictate in large part which patients are able to maintain dynamic knee stability in the absence of ligamentous support. There is evidence suggesting that some populations may not be able to adequately compensate for ACL deficiency. Individuals who sustain a noncontact ACL rupture may have compromised neuromuscular control. In this scenario, ligament rupture occurs as internal forces exceed ligament tensile properties. A failure of lower extremity muscle control (eg, delayed contractions or altered muscle recruitment order) during provocative activities such as jumping, cutting, and pivoting can increase the demand on the static joint stabilizers and lead to ACL rupture. Or, in the patient with ACL deficiency, inadequate muscle control may result in a giving-way episode. The mechanism underlying contact ACL injuries is quite different. Simply, the knee is exposed to an external load, produced by another person or object, that exceeds the tensile properties of the ligament.

Highly active female athletes and older adults also exhibit neuromuscular characteristics that suggest that these individuals may not be able to successfully compensate for ACL deficiency. In comparison to male athletes, females produce less muscle stiffness,31,32 recruit quadriceps (an ACL antagonist) before hamstring (an ACL agonist) muscles,14,15,33 and have delayed hamstring reactions in response to anterior stress on the ACL.15 Age-related changes in neuromuscular performance have also been documented. Decreases in joint position sense,16,19,27 slower muscle response time,18 and slower time to peak torque18 have been reported in older versus younger populations. Most studies evaluating the influence of age on neuromuscular performance include age groups not associated with ACL injuries. Regression in neuromuscular performance, however, would occur across a continuum and not at a specific age. Therefore, the risk for experiencing knee instability after ACL rupture may increase with age.

Identifying populations at risk for experiencing knee instability after ACL rupture may provide surgeons and rehabilitation clinicians with important information about patient demographics and functional characteristics that help guide patient management, and may provide further insight to the development of dynamic knee stability. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to investigate the influence of age, gender, and mechanism of injury on the restoration of dynamic knee stability after ACL rupture. We hypothesized that (1) more females would be classified as noncopers than potential copers, (2) more individuals who sustained a noncontact ACL injury would be classified as noncopers than potential copers, (3) more individuals who sustained a noncontact injury would be classified as noncopers than males and females who were injured by contact, and (4) there would be a greater proportion of noncopers than potential copers across all age groups, with the greatest difference occurring in individuals categorized as older adults.

Materials and Methods

Subjects

The sample included all patients from the practice of a single orthopaedic surgeon over a 10-year period that met all inclusion criteria, including regular preinjury participation in level I or II activities (Table 1),5,12 ACL insufficiency, and screening completion within 7 months of injury. Three hundred forty-five consecutive patients (mean age, 27 years; range, 13-57 years) who met study eligibility criteria were enrolled an average of 6 weeks (range, 1-28 weeks) after injury. Exclusion criteria included bilateral knee involvement and any lower extremity or low back injuries that prevented the completion of the screening examination. Patients were also ineligible for the study if they had concomitant or symptomatic grade III injury to other knee ligaments, a repairable meniscus tear, or full-thickness articular cartilage defect. The diagnosis of complete rupture of the ACL was based on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) results and a minimum 3-mm side-to-side difference during knee arthrometer testing (KT-2000; MedMetrics, San Diego, CA) using an anterior, manual maximum pull.5 All patients provided informed consent approved by The University of Delaware Institutional Review Board prior to testing and patient privacy was protected in accordance with the Health Insurance and Portability and Accountability Act.

TABLE 1. Activity Level Classification5,12.

| Level | Sports Activity | Occupation Activity |

|---|---|---|

| I | Jumping, cutting, pivoting (basketball, soccer, football) | Activity comparable to level I sports |

| II | Lateral movements: less jumping, pivoting than level I (baseball, racket sports) | Heavy manual labor, working on uneven surface |

| III | Straight-ahead activities: no jumping or pivoting (running, weightlifting) | Light manual work |

| IV | Sedentary | Activities of daily living |

Screening Examination

If the patient had limited knee range of motion, more than trace knee effusion, less than 70% quadriceps strength, or could not hop on the involved limb without pain while wearing a functional knee brace, prescreening rehabilitation was undertaken to address the impairments (Table 2). Quadriceps strength was measured isometrically at 90° of knee flexion using the burst-superimposition technique,28 and calculated as a percentage of force output of the involved limb relative to the contralateral limb. After all impairments were resolved and adequate quadriceps muscle strength obtained, patients completed the University of Delaware Screening Examination9 to determine their classification as either a potential coper or noncoper.

TABLE 2. Prescreening Rehabilitation.

| Impairment | Intervention |

|---|---|

| Effusion | Ice, compression, elevation, isometric muscle pumping, retrograde massage |

| Joint mobility | Supine wall slides (patient places foot on wall and slides foot down the wall to increase knee flexion), flexion and extension active range of motion, patellar mobilizations, stationary cycling (low resistance), low-load prolonged stretching, emphasis of normal knee flexion and extension excursions during gait |

| Muscle performance | Isometric quadriceps and hamstrings contractions, straight-leg raising, electrical stimulation quadriceps strength-training protocol (if indicated by presence of diminished quadriceps contraction, knee extensor lag on straight leg raising, or an inability to perform a straight-leg raise), resisted knee extensions (90°-45°) and knee flexion with elastic bands |

| Weight-bearing | Partial squats (0°-45°), heel raises, lateral step-ups, trampoline jogging and hopping, encourage walking program and stair climbing |

| Pain | Electrical and thermal modalities, McConnell taping for patellofemoral pain, physician referral for medication or injection assistance |

The screening examination consisted of unilateral hop testing,25 2 self-assessment of knee function questionnaires, and recording the number of patient-reported giving-way episodes that had occurred during activities of daily living since the initial injury. The single-leg hop tests were conducted according to the Noyes25 protocol while subjects wore an of-the-shelf functional knee brace. Self-assessment of knee function was evaluated with the Knee Outcome Survey-Activities of Daily Living Scale (KOS-ADLS) and global rating scale after the hop testing protocol had been completed.

After completing the screening examination patients were classified as either a potential coper or noncoper. Variables and cut-off criteria for patient classification were established in earlier work9 that distinguished highly active symptomatic and asymptomatic individuals after ACL injury. To be classified as a potential coper, patients had to meet the following criteria: 80% or greater on the timed hop test, 80% or greater on the KOS-ADLS, 60% or greater on the Global Rating Scale, and no more than 1 giving-way episode since the initial injury. Failure to meet any of these criteria resulted in patient classification as a noncoper.

Descriptive statistics and chi-square tests of independence were calculated to describe patient demographics and identify significant distribution differences. The proportion of potential copers and noncopers was evaluated by gender and mechanism of injury (contact versus noncontact). Categories were developed to evaluate the proportion of potential copers and noncopers by age, including middle-school and high-school age (12-17 years old), college age (18-23 years old), young adult (24-34 years old), mid-aged adult (35-44 years old), and older adult (45 years old and over).

Statistical significance was established at P<.05. All analyses were performed with commercially available software (SPSS Version 14.0; SPSS, Inc, Chicago, IL).

Results

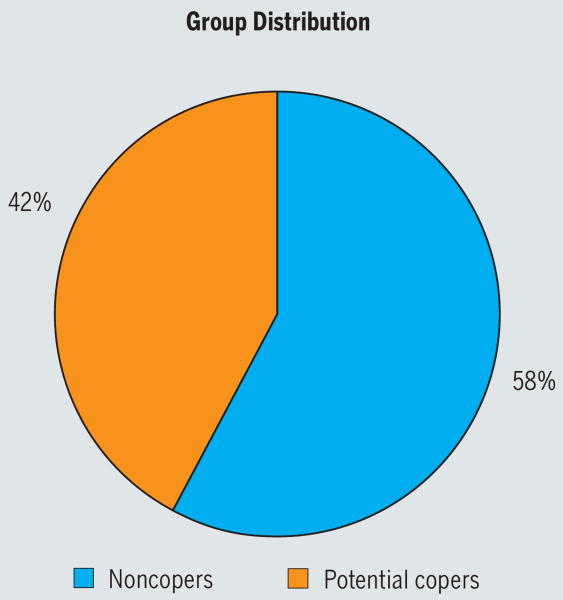

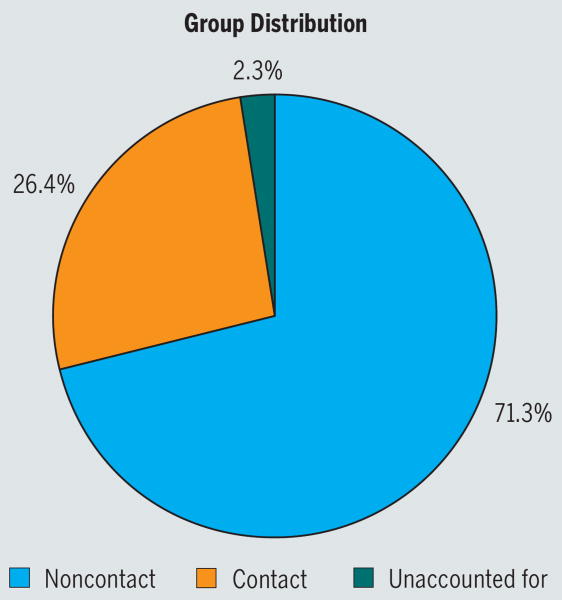

There were more noncopers in the group (n = 199, 58%) than potential copers (n = 146, 42%) (Figure 1), more males (n = 216, 62.6%) than females (n = 129, 37.4%), and more injuries were sustained via noncontact (n = 246, 71.3%) than contact (n = 91, 26.4%) mechanisms (Figure 2). Eight individuals could not recall whether their index injury involved contact. The greatest number of subjects were in the college-aged (n = 91, 26.4%) and young-adult (n = 90, 26.1%) groups, followed by middle-school and high-school (n = 76, 22%), mid-aged (n = 66, 19.1%), and older-adult (n = 22, 6.4%) groups.

FIGURE 1.

Percentage of patients classified as noncopers and potential copers.

FIGURE 2.

Percentage of contact and noncontact injuries sustained by individuals who completed the anterior cruciate ligament screening examination.

Screening Results

The distribution of potential copers and noncopers was different based on gender and the mechanism of injury. Females were more likely to be classified as noncopers (n = 82) than potential copers (n = 47) (χ2 = 9.496, P = .002), while the distribution of potential copers (n = 99) and noncopers (n = 117) was not statistically different for males (χ2 = 1.500, P = .221) (Table 3). Individuals who sustained a noncontact ACL injury were more likely to be classified as noncopers (n = 143) than potential copers (n = 103) (χ2 = 6.504, P = .011), but there was not a significant difference in distribution of potential copers (n = 41) and noncopers (n = 50) for contact ACL injuries (χ2 = 0.890, P = .345) (Table 4). Classification for females was different based on the mechanism of injury: females who sustained noncontact ACL injuries were more frequently classified as noncopers (n = 62) than potential copers (n = 36) (χ2 = 6.898, P = .009), while the distribution of female potential copers (n = 10) and noncopers (n = 16) who sustained a contact ACL injury was not significantly different (χ2 = 1.385, P = .239) (Table 5). The distribution of potential copers and noncopers for males was not significantly different for injuries sustained via either noncontact (potential copers, n = 67; noncopers, n = 81; χ2 = 1.324, P = .250) or contact (potential copers, n = 31; noncopers, n = 34; χ2 = 0.138, P = .710) mechanisms (Table 5).

TABLE 3. Potential Coper (PC)/Noncoper (NC) Distribution Based on Gender.

| Male | Female | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PC | NC | PC | NC | |

| Observed, n (%) | 99 (46%) | 117 (54%) | 47 (36%) | 82 (64%) |

| Expected | 108.0 | 64.5 | ||

| Chi-square | 1.500 | 9.496 | ||

| P value | .221 | .002 | ||

TABLE 4. Potential Coper (PC)/Noncoper (NC) Distribution Based on Mechanism of Injury.

| Noncontact | Contact | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PC | NC | PC | NC | |

| Observed, n (%) | 103 (42%) | 143 (58%) | 41 (45%) | 50 (55%) |

| Expected | 123.0 | 45.5 | ||

| Chi-square | 6.504 | .890 | ||

| P value | .011 | .345 | ||

TABLE 5. Potential Coper (PC)/Noncoper (NC) Distribution Based on Gender and Mechanism of Injury.

| Men | Women | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Contact | Noncontact | Contact | Noncontact | |||||

| PC | NC | PC | NC | PC | NC | PC | NC | |

| Observed, n (%) | 31 (48%) | 34 (52%) | 67 (45%) | 81 (55%) | 10 (38%) | 16 (62%) | 36 (37%) | 62 (63%) |

| Expected | 32.5 | 74.0 | 13.0 | 49.0 | ||||

| Chi-square | .138 | 1.324 | 1.385 | 6.898 | ||||

| Alpha | .710 | .250 | .239 | .009 | ||||

There was a statistically significant difference in the distribution of potential copers and noncopers across age groups (χ2 = 9.542, P = .049). Analysis of distribution within the different age groups indicated there were significantly more noncopers (n = 48) than potential copers (n = 18) in the mid-aged adult group (χ2 = 13.636, P<.001) but no difference in distribution within any other age group (middle-school/high-school age group: potential copers, n = 40; noncopers, n = 36; χ2 = 0.211, P = .646; college-age group: potential copers, n = 39; noncopers, n = 52; χ2 = 1.857, P = .173; young-adult group: potential copers, n = 39; noncopers, n = 51; χ2 = 1.6, P = .206; older-adult group: potential copers, n = 10; noncopers, n = 12; χ2 = 0.182, P = .670).

Discussion

The proportion of individuals who experience dynamic knee instability after ACL rupture is greater among specific patient groups. As we predicted, females and individuals who sustained noncontact ACL injuries were more frequently classified as noncopers than as potential copers. Females that sustained noncontact ACL injuries were more frequently classified as noncopers than potential copers in comparison to individuals of either sex who sustained a contact injury. Our hypothesis that more individuals would be classified as noncopers with increasing age was not supported by the results; nor was our hypothesis that the oldest age group would have the greatest proportion of noncopers. The group with the greatest frequency of patients classified as noncopers based on age was the mid-aged adult group (age 35 to 44).

Within this sample there were gender differences in the return of dynamic knee stability after ACL rupture. Gender diferences in neuromuscular characteristics, including timing24,26 and magnitude33 of muscle activation, are one of the multiple factors contributing to the difference in ACL injury rates between men and women.13 That more females were classified as noncopers after sustaining a noncontact injury suggests that neuromuscular characteristics which predispose highly active female athletes to noncontact ACL rupture may also influence the ability to dynamically stabilize the knee after injury. This hypothesis is further supported by our results of a more equal distribution of female potential copers and noncopers when the mechanism of injury involved contact. The sample of females who had sustained a contact ACL injury was, however, admittedly small (n = 27), reflecting the limited participation of female athletes in contact sports.

Though not statistically significant, there was a progressively greater distribution of noncopers than potential copers with advancing age from the middle-school/high-school through mid-aged groups. The trend did not continue with our oldest age category, as the distribution of noncopers was not significantly different from potential copers in the older-adult group. However, our sample of individuals over the age of 45 was small (n = 22). The influence of age on the return of dynamic knee stability after ACL rupture may not be accurately represented by this limited sample. The small number of older adults who were in the study reflects a general decline in high-level sports participation with age. This finding, however, underscores that ACL injury is not pervasive among older age groups. Our entire cohort was young, with an average age of 27, and 75% of the sample less than 34 years old. Furthermore, for all age groups, the number of noncopers was equal to or greater than the number of potential copers. The average individual who sustains an ACL injury is young and likely to experience knee instability upon a return to demanding sports activities. A return to a highly active lifestyle after ACL injury is predicated on restoring knee stability. For orthopaedic surgeons in the United States, ACL reconstruction is the preferred treatment for accomplishing this goal.7,21

An additional benefit from this study is further insight into a population of highly active patients with acute, isolated ACL deficiency. Our population of patients with ACL deficiency consisted of more males than females. Though much attention has been given to the female ACL “epidemic,” this is because of the high rate (noncontact injury per player hour) of ACL injuries occurring among female athletes.1,4,6,11,17,22 There are, however, still a greater number of males participating in sports compared to females and more males participating in collision sports. The larger percentage of males comprising our total population was, therefore, expected. More individuals sustained noncontact than contact injuries in our cohort. These findings are in agreement with the relative consensus in the literature that approximately 70% of all ACL injuries are noncontact in nature.2,13,23 The disparity between the rate of contact and noncontact injuries stems from the limited number of sports that involve contact (eg, American football, rugby). The relative exposure to situations that might result in contact ACL injuries is therefore drastically less than the number of typical noncontact situations (eg, performance of pivoting, cutting, and jumping maneuvers in all contact and noncontact sports).

Although results from the current study suggest that there are patient populations that are more likely to experience knee instability after ACL rupture, we do not recommend guiding patient management strictly based on demographic characteristics. The screening examination is a means to provide individualized patient management when individuals are deciding between surgical and nonoperative care. Fitzgerald9 reported that 79% of individuals who were identified as potential copers were successful with a nonoperative return (6 months or less) to preinjury activities, with an increased probability of success with nonoperative care after a specialized physical therapy intervention.10 Results from the current study may be used to further improve outcomes by refining the criteria for classification as a potential coper or noncoper, based on gender and injury mechanism.

Conclusion

The results of this study indicate that specific patient groups are more likely to be symptomatic if managed nonoperatively, primarily women who sustain ACL injuries via noncontact mechanisms. Furthermore, the average individual who sustains an ACL injury is young and likely to experience knee instability upon a return to demanding sports activities without surgical reconstruction.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge G. Kelley Fitzgerald, PT, PhD, OCS and Terese Chmielewski, PT, PhD, SCS for their assistance with subject testing and Martha Callahan for her assistance with data organization.

Funding provided by the National Institutes of Health (R01HD037985 and R01AR048212) and the Foundation for Physical Therapy (Mary McMillan, PODS I, and PODS II). The methods described in this manuscript were approved by The Human Subjects Review Board of the University of Delaware.

Footnotes

Key Points: Findings: There was a significant difference in the distribution of individuals who were classified as having poor and good dynamic knee stability after anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) rupture, based on gender and mechanism of injury.

Implication: Specific patient groups, including females and individuals injured via noncontact mechanisms, are more likely to be symptomatic after an ACL rupture when managed nonoperatively.

Caution: The presence of dynamic knee stability was based on results of a validated screening examination; this study did not evaluate patient demographics as a predictor of outcomes after ACL rupture.

References

- 1.Arendt E, Dick R. Knee injury patterns among men and women in collegiate basketball and soccer. NCAA data and review of literature. Am J Sports Med. 1995;23:694–701. doi: 10.1177/036354659502300611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boden BP, Dean GS, Feagin JA, Jr, Garrett WE., Jr Mechanisms of anterior cruciate ligament injury. Orthopedics. 2000;23:573–578. doi: 10.3928/0147-7447-20000601-15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Corry II, Webb J. Injuries of the sporting knee. Br J Sports Med. 2000;34:395. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.34.5.395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cox JS, Lenz HW. Women midshipmen in sports. Am J Sports Med. 1984;12:241–243. doi: 10.1177/036354658401200315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Daniel DM, Stone ML, Dobson BE, Fithian DC, Rossman DJ, Kaufman KR. Fate of the ACL-injured patient. A prospective outcome study. Am J Sports Med. 1994;22:632–644. doi: 10.1177/036354659402200511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.DeHaven KE, Lintner DM. Athletic injuries: comparison by age, sport, and gender. Am J Sports Med. 1986;14:218–224. doi: 10.1177/036354658601400307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Delay BS, Smolinski RJ, Wind WM, Bowman DS. Current practices and opinions in ACL reconstruction and rehabilitation: results of a survey of the American Orthopaedic Society for Sports Medicine. Am J Knee Surg. 2001;14:85–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eastlack ME, Axe MJ, Snyder-Mackler L. Laxity, instability, and functional outcome after ACL injury: copers versus noncopers. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1999;31:210–215. doi: 10.1097/00005768-199902000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fitzgerald GK, Axe MJ, Snyder-Mackler L. A decision-making scheme for returning patients to high-level activity with nonoperative treatment after anterior cruciate ligament rupture. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2000;8:76–82. doi: 10.1007/s001670050190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fitzgerald GK, Axe MJ, Snyder-Mackler L. The efficacy of perturbation training in nonoperative anterior cruciate ligament rehabilitation programs for physical active individuals. Phys Ther. 2000;80:128–140. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Griffin LY, Agel J, Albohm MJ, et al. Noncontact anterior cruciate ligament injuries: risk factors and prevention strategies. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2000;8:141–150. doi: 10.5435/00124635-200005000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hefti F, Muller W, Jakob RP, Staubli HU. Evaluation of knee ligament injuries with the IKDC form. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 1993;1:226–234. doi: 10.1007/BF01560215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hewett TE, Myer GD, Ford KR. Anterior cruciate ligament injuries in female athletes: Part 1, mechanisms and risk factors. Am J Sports Med. 2006;34:299–311. doi: 10.1177/0363546505284183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hurd WJ, Chmielewski TL, Snyder-Mackler L. Perturbation-enhanced neuromuscular training alters muscle activity in female athletes. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2006;14:60–69. doi: 10.1007/s00167-005-0624-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huston LJ, Wojtys EM. Neuromuscular performance characteristics in elite female athletes. Am J Sports Med. 1996;24:427–436. doi: 10.1177/036354659602400405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kaplan FS, Nixon JE, Reitz M, Rindfleish L, Tucker J. Age-related changes in proprioception and sensation of joint position. Acta Orthop Scand. 1985;56:72–74. doi: 10.3109/17453678508992984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lindenfeld TN, Schmitt DJ, Hendy MP, Mangine RE, Noyes FR. Incidence of injury in indoor soccer. Am J Sports Med. 1994;22:364–371. doi: 10.1177/036354659402200312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mackey DC, Robinovitch SN. Mechanisms underlying age-related differences in ability to recover balance with the ankle strategy. Gait Posture. 2006;23:59–68. doi: 10.1016/j.gaitpost.2004.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Madhavan S, Shields RK. Influence of age on dynamic position sense: evidence using a sequential movement task. Exp Brain Res. 2005;164:18–28. doi: 10.1007/s00221-004-2208-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Majewski M, Susanne H, Klaus S. Epidemiology of athletic knee injuries: A 10-year study. Knee. 2006;13:184–188. doi: 10.1016/j.knee.2006.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Marx RG, Jones EC, Angel M, Wickiewicz TL, Warren RF. Beliefs and attitudes of members of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons regarding the treatment of anterior cruciate ligament injury. Arthroscopy. 2003;19:762–770. doi: 10.1016/s0749-8063(03)00398-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McClay Davis I, Ireland ML. ACL research retreat: the gender bias. April 6-7, 2001. Meeting report and abstracts. Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon) 2001;16:937–959. doi: 10.1016/s0268-0033(01)00087-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McNair PJ, Marshall RN, Matheson JA. Important features associated with acute anterior cruciate ligament injury. N Z Med J. 1990;103:537–539. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Myer GD, Ford KR, Hewett TE. The effects of gender on quadriceps muscle activation strategies during a maneuver that mimics a high ACL injury risk position. J Electromyogr Kinesiol. 2005;15:181–189. doi: 10.1016/j.jelekin.2004.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Noyes FR, Barber SD, Mangine RE. Abnormal lower limb symmetry determined by function hop tests after anterior cruciate ligament rupture. Am J Sports Med. 1991;19:513–518. doi: 10.1177/036354659101900518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rozzi SL, Lephart SM, Gear WS, Fu FH. Knee joint laxity and neuromuscular characteristics of male and female soccer and basketball players. Am J Sports Med. 1999;27:312–319. doi: 10.1177/03635465990270030801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Skinner HB, Barrack RL, Cook SD. Age-related decline in proprioception. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1984:208–211. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Snyder-Mackler L, De Luca PF, Williams PR, Eastlack ME, Bartolozzi AR., 3rd Reflex inhibition of the quadriceps femoris muscle after injury or reconstruction of the anterior cruciate ligament. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1994;76:555–560. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199404000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Snyder-Mackler L, Fitzgerald GK, Bartolozzi AR, 3rd, Ciccotti MG. The relationship between passive joint laxity and functional outcome after anterior cruciate ligament injury. Am J Sports Med. 1997;25:191–195. doi: 10.1177/036354659702500209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Williams GN, Chmielewski T, Rudolph K, Buchanan TS, Snyder-Mackler L. Dynamic knee stability: current theory and implications for clinicians and scientists. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2001;31:546–566. doi: 10.2519/jospt.2001.31.10.546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wojtys EM, Ashton-Miller JA, Huston LJ. A gender-related difference in the contribution of the knee musculature to sagittal-plane shear stiffness in subjects with similar knee laxity. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2002;84-A:10–16. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200201000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wojtys EM, Huston LJ, Schock HJ, Boylan JP, Ashton-Miller JA. Gender differences in muscular protection of the knee in torsion in size-matched athletes. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2003;85-A:782–789. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200305000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zazulak BT, Ponce PL, Straub SJ, Medvecky MJ, Avedisian L, Hewett TE. Gender comparison of hip muscle activity during single-leg landing. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2005;35:292–299. doi: 10.2519/jospt.2005.35.5.292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]